KITCHEN CORNER

SAMUEL ROY-BOIS

KITCHEN CORNER

SAMUEL ROY-BOIS

Vernon Public Art Gallery

January 9 - March 11, 2026

Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Vernon Public Art Gallery

3228 - 31st Avenue, Vernon, British Columbia, V1T 2H3, Canada

January 9 - March 11, 2026

Production: Vernon Public Art Gallery

Editor: Victoria Verge

Layout and graphic design: Vernon Public Art Gallery

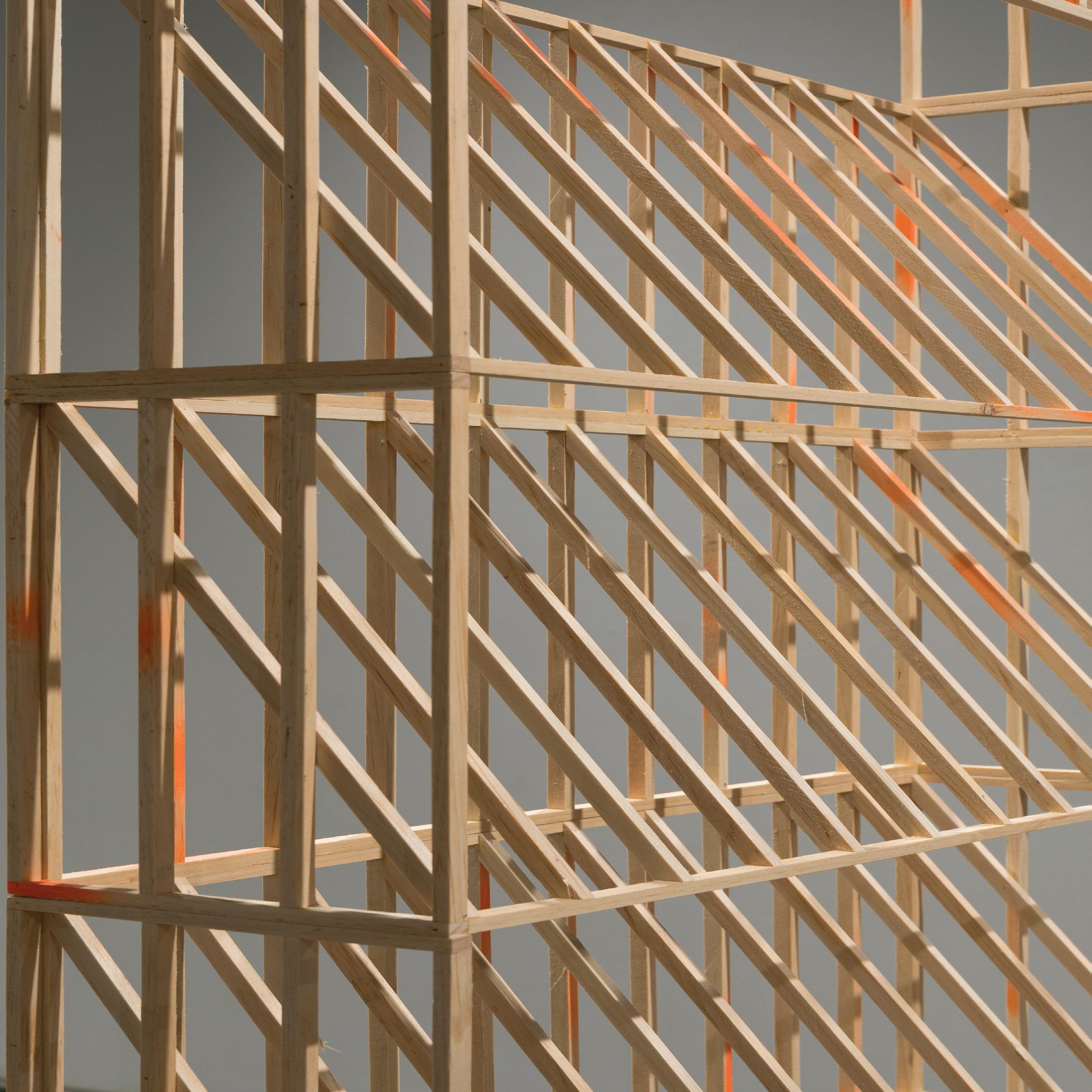

Front cover: Balloon (Vent), 2025, wood, paint, object, 99.25x79.5x15.25 in (detail image)

Photography: Yuri Akuney, Digital Perfections, Kelowna, British Columbia

Printing: Get Colour Copies, Vernon, British Columbia, Canada

ISBN 978-1-927407-95-0

Copyright © 2026 Vernon Public Art Gallery

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the Vernon Public Art Gallery. Requests for permission to use these images should be addressed in writing to the Vernon Public Art Gallery, 3228 31st Avenue, Vernon BC, V1T 2H3, Canada. Telephone: 250.545.3173, website: www. vernonpublicartgallery.com.

The Vernon Public Art Gallery is a registered not-for-profit society. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Greater Vernon Advisory Committee/RDNO, the Province of BC’s Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch, British Columbia Arts Council, the Government of Canada, corporate donors, sponsors, general donations and memberships. Charitable Organization # 108113358RR.

This exhibition is sponsored in part by:

1 Executive Director’s Foreword · Dauna Kennedy

2 Curatorial Introduction · Victoria Verge

6 The School of Baudelaire: On the Balloon Sculptures of Samuel Roy-Bois · Aaron Peck

9 Artist Statement · Samuel Roy-Bois

11 Images of Artwork in the Exhibition

37 Curriculum Vitae · Samuel Roy-Bois

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD

On behalf of the Board of Directors and the Vernon Public Art Gallery (VPAG), I am pleased to present this publication documenting the work of artist Samuel Roy-Bois, Associate Professor in Sculpture at UBC Okanagan and an award-winning artist. Kitchen Corner, the title of this body of work builds on ideas presented in a photograph by Walker Evans of the same name, but through the lens of architectural references. This publication will both document and guide the reader through the quizzical references of each piece and the united body of work as a whole.

Curator for the VPAG, Victoria Verge, provides a critical introduction to the work and provides visual references of the exhibition through the photographs contained within this publication.

Also contributing to this publication is guest writer, critic and author Aaron Peck. Growing up in the Okanagan, Peck’s work has spanned the continent, and he most recently is a contributor to the Times Literary Supplement and Aperture magazine.

I would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Province of British Columbia, the Regional District of the North Okanagan, and the BC Arts Council, whose funding enables us to produce exhibitions such as this for the residents and visitors of the North Okanagan region and interested parties across Canada.

We hope you enjoy this exhibition and accompanying publication.

Regards,

Dauna Kennedy Executive Director Vernon Public Art Gallery

CURATORIAL INTRODUCTION

At first encounter, the works assembled in Kitchen Corner appear provisional; structures caught in midthought. Roy-Bois moves between registers of construction: some works read as light, open framing, while others are built from thick, weight-bearing beams that introduce a bodily sense of mass. Across the exhibition, structure is never merely technical. Frames lean, brace, and hold; surfaces are marked with vivid colour; textiles and everyday objects enter as props or supports. These works speak fluently in the language of building, yet they resist the logic of completion that architecture typically demands.

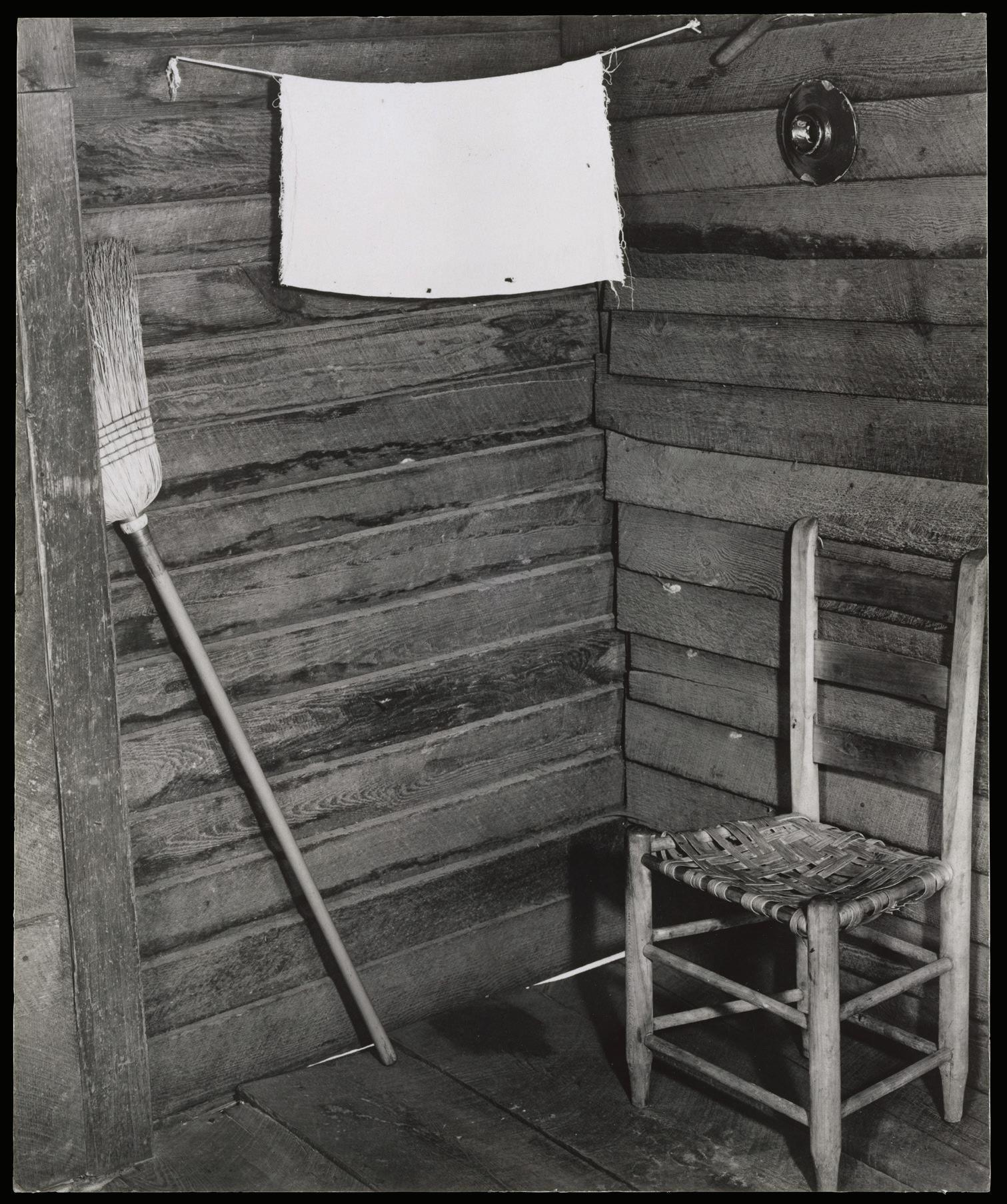

The exhibition takes its title from Kitchen Corner, a Depression-era photograph by Walker Evans. The image depicts a modest interior through the arrangement of everyday objects – a broom, a rag, a chair – while conspicuously omitting the fixtures that would normally define a kitchen. In this dissonance between title and image, Evans foregrounds the expressive capacity of objects beyond their functional roles. They become characters in a scene, momentarily paused between use. While Evans’s photograph is not a direct source for the works on view, its sensibility resonates with Roy-Bois’s approach: an attentiveness to how meaning gathers around things when they are removed from utility and allowed to simply exist.

Produced over the past eighteen months, the works in Kitchen Corner were not initially conceived as a unified installation. Their convergence, however, reveals a shared investigation into structure, agency, and the ways built environments shape (and are shaped by) human experience. Across varied scales and configurations, Roy-Bois’s sculptures operate in a space of indeterminacy: between recognition and abstraction, stability and collapse, support and constraint. Rather than presenting architecture as a finished product, he exposes it as a process, one that mirrors the ongoing formation of identity itself.

Central to this inquiry is the Balloon series: Balloon (Vent), Balloon (Midrise), Balloon (Parkade), Balloon (Aviary), and Balloon (Schematic). These works draw from balloon framing, a nineteenth-century construction method that enabled rapid building through standardized materials and industrial nail production. Widely adopted across North America, balloon framing played a significant role in shaping modern urban and suburban landscapes, including those of the Okanagan Valley. Roy-Bois isolates this method’s skeletal logic, translating it into a sculptural language of openness and exposure.

Constructed from light, lattice-like framing, the Balloon works emphasize outline rather than mass. Installed upright or horizontally and delicately balanced, they resist the stability typically associated with architecture. Balloon (Vent) rises vertically with a sense of aspiration tempered by fragility, while Balloon (Midrise) compresses that ambition into a narrow, precarious column. Balloon (Parkade) spreads outward, recalling utilitarian civic infrastructure, and Balloon (Aviary) suggests permeability and lightness, as though

Walker Evans (American, St. Louis, Missouri 1903--1975 New Haven, Connecticut), Kitchen Comer, Tenant Farmhouse, Hale County, Alabama, 1936, Gelatin silver print, Image: 7 11/16 x 6 5/16 in.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

designed for habitation by something other than humans. Balloon (Schematic), with its angled planes and diagrammatic clarity, reads almost as a drawing translated into space; an instruction set rather than a structure.

These works do not offer shelter. Instead, they foreground exposure. Their openness collapses distinctions between interior and exterior, allowing viewers to see through them entirely. In doing so, Roy-Bois directs attention to the ways structures—architectural, social, and ideological—shape how we move, behave, and understand our place within them. The sculptures act as metaphors for systems that quietly guide daily life, revealing themselves most clearly at moments of tension or limit.

If the Balloon works articulate structure through light framing and architectural outline, the Unit series brings that inquiry closer to the body and into the realm of domestic space, doing so with greater material weight. Built from thick wooden beams and joined with an assertive, load-bearing presence, the Unit works feel less like sketches of buildings and more like figures—upright, grounded, and physically insistent. Works titled Unit (Find a Better Dream to Dream), Unit (Effortlessly Difficult), Unit (Arts and Gun Club), and Unit (Title Zero) incorporate fabric elements that hang from steel curtain rods integrated directly into the beams. Made of loosely woven linen in pale pinks, yellows, and blues, these textiles read unmistakably as curtains: soft, permeable thresholds that signal interior life rather than structural necessity.

During a summer visit to Roy-Bois’s studio in Lake Country, BC, the artist described how he often thinks of these works as characters on a stage. Seen this way, the Unit pieces read less as structures and more as figures. Each possesses a distinct stance or posture, its proportions bodily rather than architectural. The linen elements extend this theatrical register, operating simultaneously as curtains and as clothing. They recall stage drapery that frames an implied performance, while also reading as garments: something worn, provisional, and close to the body. At the same time, their resemblance to domestic window coverings introduces the suggestion of interior life. In this layering of references, the Unit works occupy a space between stage and home, costume and furnishing, figure and structure.

The weight of the beams matters. Unlike the airy Balloon structures, the Unit works appear capable of holding their ground. Their mass gives them a sense of resolve, even as their forms remain open. The fabric does not counter this weight so much as coexist with it. Suspended within the rigid frame, the linen introduces vulnerability, intimacy, and care, qualities often absent from architectural discourse yet central to lived experience. The relationship between beam and cloth is reciprocal: the structure supports the fabric, while the fabric redefines the structure’s meaning. What emerges is not shelter, but the suggestion of interior life. This domestic inflection is further extended by the fact that the linen elements were sewn by the artist’s wife, embedding an unspoken layer of relational labour into the work.

The titles add another register to this reading. Find a Better Dream to Dream suggests aspiration caught in repetition, while Effortlessly Difficult captures the paradoxes of contemporary labour and self-optimization.

Arts and Gun Club juxtaposes cultural refinement with violence or exclusion, and Title Zero gestures towards refusal, reset, or erasure. These phrases read like fragments of internal monologue, holding contradiction without resolution. They do not describe the works so much as hover around them, reinforcing the sense that these figures are not fixed identities but sites of ongoing negotiation.

Seen through this lens, the gallery becomes less a stage than a shared interior, and the Unit works its inhabitants. They appear paused mid-gesture, neither fully private nor fully public, framed but permeable. The curtains do not close; they hang open, allowing light, air, and projection to pass through. The sense of incompletion that runs throughout Kitchen Corner is not a lack, but a condition that makes room for domestic presence—messy, provisional, and quietly insistent.

Across the exhibition, small details become expressive: the grain of wood, the sag of fabric, the visible joins that hold beams together. Meaning arises through careful arrangement rather than spectacle. Grounded in local histories of construction while engaging broader questions of infrastructure, labour, and subjectivity, Kitchen Corner offers no conclusions. Instead, it presents frameworks through which viewers are invited to consider the structures they inhabit and internalize. Like the photograph by Walker Evans, the works suggest that meaning often resides not in what is fully present, but in what is withheld—objects paused between use, structures waiting without resolution.

Victoria Verge Curator Vernon Public Art Gallery

THE SCHOOL OF BAUDELAIRE: ON THE BALLOON SCULPTURES OF SAMUEL ROY-BOIS

by Aaron Peck

1.

In the Greater Vernon Museum and Archives, there are photographs of city construction. Mount View Ranch, BX, house construction and framing, 1914, for example, documents a typical building style known as balloon framing, which has had a significant influence on urban development in North America since the early nineteenth century. Used throughout the continent, particularly from the 1830s until the 1920s, the building method was the result of industrial production of nails, allowing builders to put up structures much more quickly with less woodworking specialization. In 1891, when the Canadian Pacific Railroad extended into the Okanagan, Vernon – the valley’s first large municipality – boomed, and that construction technique contributed to its development. It was, in some ways, the first step toward contemporary prefab housing, the kind which so much of the Okanagan Valley is made of,1 and it is the skeletal form of much of the valley’s modern built environment, as Mountain View Ranch reveals.

Stripped of their finishings, though, the frames look like sculptures. And that is how Samuel Roy-Bois reimagines them. The form and arrangement of his balloon sculptures are playful, with dashed-off splashes of colour, orange, green, or pink. Some are placed on top of other objects, such as glass jars or plastic pails; it’s almost like they were the leftovers of a construction site. An accompanying sculpture, with a larger wooden frame, has fabric hanging from it. His installation could also appear to be props for a stage play, as if these things were talking to each other, and that sense of communication is key, because these works have an unexpected literary quality. Together, the pieces resemble sentences that combine to form paragraphs. Each sculpture could be recombined, or their installation rearranged, just like how writers edit text. RoyBois’s works are, in this way, like drafts of unfinished manuscripts, a similarity that connects them to a very different aesthetic tradition, one that starts in nineteenth-century France.

2.

In the final years of his life, the French poet Charles Baudelaire kept all of his papers in a large trunk, which he guarded feverishly. The case contained his life’s work: his correspondence, his unfished projects, his notes. He dragged it with him to Brussels, where he lived from April 1864 to July 1866, moving there in the hopes of completing and then selling two manuscripts: a gathering of essays he called “Contemporaries” and a collection of prose poems titled “Paris Spleen.” He finished neither. While in the Belgian capital, he also produced a series of notes and sketches for a book proposal about Belgium, as well as jotting aphorisms for a series of abandoned autobiographical works.2 In April 1886, a stroke left him aphasic and paralyzed; he died a year later in Paris. The contents of his trunk remained in the state he left them.

Baudelaire lived most of his life as an underappreciated writer. In his last years – in debt, gravely ill, and depressed – his attempts to land a publishing contract were met with disappointment. And yet, during that same time, a number of younger writers began to read him with more and more attention. In a letter only months before he lost the ability to speak or write, Baudelaire boasted to his mother that a “School of Baudelaire” was growing. All the while, he continued scribbling away on notes for books he would never complete. Like unfinished homes, the material in Baudelaire’s trunk leaves much for the imagination: the sketches for works that could have been realized.

Excerpts from those notes were finally published in 1887 in a collection titled Posthumous Works. Friedrich Nietzsche purchased a copy while on holiday in Nice in 1888, and their incomplete and aphoristic style can be seen to influence the German philosopher’s, particularly in his book Ecce Homo. Baudelaire’s writings also inspired the poet Stephane Mallarmé, who had been part of the “school” Baudelaire mentioned to his mother, and who wrote cryptic poems with meanings that are hard to pin down in French, let alone in translation. During Mallarmé’s short life (he died in a choking fit, at fifty-eight), he collected a series of notes, mathematical formulas, jotted fragments of phrases. He called this Le Livre (in English: The Book), an impossible project wherein the entirety of literature and reality would be contained. He completed less than two-hundred pages of fragmentary notes, which were finally published in 1957. And since then, generations of poets have produced work that appears to be in an unfinished state.

3.

Mallarmé’s notes even found their way into contemporary art through artists who have made works responding to the poet – from Marcel Brodthaers to Rodney Graham and Ian Wallace (the latter having made a series specifically about Le Livre). And now, slightly more obliquely, also Samuel Roy-Bois.

Roy-Bois’s balloon sculptures play with the idea of an unfinished work and thus explore the possibility of form. With a light touch, they ask us to consider what can be possible in art. While they are, of course, complete artworks themselves, they have nonetheless inherited the modern aesthetics of the fragmentary, particularly for how they reference a framing method, not a finished building. And they also are tied, perhaps unexpectedly, to modern literature. Consider, for example, the titles: all have Balloon followed by a more poetic subtitle that distinguishes them. It gives each piece an added sense of individuality (tiny algorithm, full spectrum, not a chance, dead center). The phrases are cryptic and enticing. What, for example, is a tiny algorithm? Full spectrum: of colour, or CBD? Dead centre of what? And what doesn’t have a chance? They read like tantalizing fragments scrawled in a found notebook.

And yet, other than the titles, there are no words: these are not conceptual artworks consisting of text. And so, here I want to return to the photograph of the Vernon construction site from 1914, because I find it fascinating that some of Roy-Bois’s research is photographic. Archival prints of construction sites in the Greater Vernon area, in this case, become a source. Instead of using language to interpret the pictures –how the writers from the literary tradition cited above would – Roy-Bois works with materials, exploring

the content of the pictures by expanding on their meanings through objects. These sculptures interpret, in purely formal and material ways, images and ideas. They don’t demand we understand their sources, but they provide enough clues to make the connections, if we’re curious, asking us to consider the frames that hold up our world. They “speak” of unfinished structures, the forms that outline things, the hidden methods of the modern world. They also link local histories in the Okanagan, such as a style of building framing, with larger histories and themes elsewhere.

1 By way of endnote, I wanted to add that I grew up in the 1980s in a spec home in Kelowna’s Mission district, no doubt built in this long tradition of balloon framing.

2Also that: When I was a teenager, in the 1990s, I found a copy of those autobiographical fragments, posthumously titled The Intimate Journals, in a tiny pocket-sized format, at Penticton’s legendary used bookstore, the Book Shoppe.

Aaron Peck is an author and critic. His books include Jeff Wall: North & West, Letters to the Pacific, and The Bewilderments of Bernard Willis. His criticism has appeared in Artforum, The Believer, and the New York Review of Books. He currently contributes to the Times Literary Supplement and Aperture magazine. He grew up in the Okanagan and gave one of his very first public readings for Greenboathouse Books at the VPAG many, many years ago.

ARTIST STATEMENT

Kitchen Corner is the title of a Depression-era photograph by Walker Evans. While not a direct source for the works assembled here, its rediscovery during the preparation of this exhibition proved resonant. Evans’s image operates as a portrait of a context articulated through objects. Documentary in nature, it renders a modest interior where things—a frayed rag, a slanted broom, a patinated chair—assume the status of characters seemingly asking to be observed, “objects in a moment of pause between use.”1 What is striking, however, is that Kitchen Corner withholds the very signifiers conventionally associated with a kitchen (no sink, no stove). In this disjunction between title and referent, the photograph underscores the complexity of representation and the capacity of objects to exceed their functional identity.

The works in this exhibition similarly dwell in thresholds of recognition. They position objects, sculptures, and bodies in states of indeterminacy: what reads as structure functions as support; what appears fragmentary gestures toward wholeness; what suggests immediacy proves resistant, even opaque. Produced over the course of eighteen months, these works were not initially conceived as a unified installation. Their subsequent convergence, however, revealed affinities of form and sensibility, generating conditions for thought and affect that exceed the sum of individual pieces.

The works composing this exhibition invite tension into the domain of the built environment. Each references architecture obliquely: through the evocation of house foundations, the abstracted language of the maquette, or vestiges of timber-frame construction. Despite their varied scales and spatial logics, they converge around a shared problematic: the negotiation between the self and the possible. In their oscillation between recognition and estrangement, they foreground the contingencies of agency and the fragility of ideals. Failure, unfulfillment, and speculation emerge not as deficiencies but as constitutive modes of experience, opening onto a broader meditation on how subjectivity is continually shaped, unsettled, and redefined through material encounter.

1Richon, Olivier. Walker Evans: Kitchen Corner. MIT Press, 2019.

Samuel Roy-Bois

ARTWORK IN THE EXHIBITION

BALLOON SERIES

Balloon (Schematic), 2025. Wood, object.

69x20.75x51.25 in.

Balloon (Aviary), 2025. Wood, object.

37.25x20x17 in.

Balloon (Vent), 2025. Wood, paint, object. 99.25x79.5x15.25 in.

Balloon (Midrise), 2025. Wood, paint, object. 88.5x26x11 in.

Balloon (Parkade), 2025. Wood, object.

55.5x45.5x19.25 in.

UNIT SERIES

Unit (Arts and Gun Club), 2025. Wood, linen, paint, steel, epoxy paint. 88.75x33x29 in.

Unit (Effortlessly Difficult), 2025. Wood, linen, paint, steel, epoxy paint. 86x24x29 in.

Unit (Title Zero), 2025. Wood, linen, paint, steel, epoxy paint. 87.5x34x43 in.

Unit (Find a Better Dream to Dream), 2025.

Wood, linen, paint, steel, epoxy paint.

73.5x23x34 in.

SAMUEL ROY-BOIS CURRICULUM VITAE

Samuel Roy-Bois (Quebec City, 1973) is an award-winning artist and Associate Professor in Sculpture at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan campus. He earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Laval University in 1996 and a Master of Fine Arts from Concordia University in 2001. Roy-Bois’ practice encompasses installation, sculpture, and photography, focusing on the built environment, vernacular practices, and art as an emergent phenomenon. His work has garnered national and international recognition, featured in exhibitions at esteemed institutions including the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM), the Audain Art Museum in Whistler, and the Esker Foundation in Calgary. His work is included in numerous Canadian collections, such as the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Simon Fraser Art Gallery, and the MACM. In recognition of his contributions, Roy-Bois was honoured with the Vancouver Mayor’s Award in 2012 and the Shadbolt Foundation VIVA Award in 2021.

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2026 Kitchen Corner, Vernon Public Art Gallery, Vernon

2025 Commercial St., Nanaimo Art Gallery, Nanaimo

2022 Life is a Tool like any Other, Musée d’art de Joliette

2021 It’s Not Me, It’s My Central Nervous System, WAAP, Vancouver

2020 Presences, Esker Foundation, Calgary

2019 Presences, Kamloops Art Gallery, Kamloops

2016 Steam Donkey, Campbell River Art Gallery, Campbell River

2015 La pyramide, Galerie L’oeil de poisson, Quebec

Not a new world, just an old trick, Oakville Galleries, Oakville

2014 Not a new world, just an old trick, Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa

2013 Not a new world, just an old trick, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby

J’ai moonwalké, sans cesse, jusqu’à l’épuisement, Parisian Laundry, Montreal

Nothing blank forever, Fina Gallery, UBC Okanagan, Kelowna

2012 I had a great trip despite a brutal feeling of cognitive dissonance, Artspeak, Vancouver

Nothing Blank Forever, Langara College Center for Art in Public Spaces, Vancouver

2011 Polarizer, Rodman Hall, Brock University, St. Catharines

2010 Candid, Republic Gallery, Vancouver

2009 Polarizer, Southern Alberta Art Gallery, Lethbridge

Polarizer, Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa

2008 Let us, then be up and doing, with a heart for any fate, still achieving, still pursuing, learn to labor and to wait, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver

Almost, Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

2007 Divertissements, Point éphémère, Paris

“It’s a big machine!”, Republic Gallery, Vancouver

2006 Improbable and ridiculous, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montreal

2005 Faire l’indépendance, Quartier éphémère, Montreal

The Monologue (Contempt and seduction), Eyelevel Gallery, Halifax

2004 Fractures mortelles, Galerie de l’École des arts visuels, Université Laval, Quebec

2003 Le monologue, Galerie Articule, Montreal

J’ai entendu un bruit, je me suis sauvé, Or Gallery, Vancouver

1999 L’espace qu’il y a, Galerie L’oeil de poisson, Quebec

GROUP EXHIBITIONS (SELECTION)

2026 Biennale de Sculpture de Trois-Rivières, Centre d’art Jacques et Michel Auger, Victoriaville

The Structure of Smoke, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver

2025 Wood, Nelson Museum and Archives

Golden Hour, Burnaby Art Gallery

10 and 10: Story of Stories, Surrey Art Gallery, Surrey

2024 Significant Forms, Kelowna Art Gallery, Kelowna

Contra-band, Trapp Gallery, Vancouver

Rise/Fall: Works from the Permanent Collection, Kelowna Art Gallery, Kelowna

2023 La nuit, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Québec

2022 Out of Control: The Concrete Art of Skateboarding, Audain Museum, Whistler

2021 SFU Art Galleries, Vancouver

2019 3 Sculptors, Trapp Projects, Vancouver

Art in the Open, Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Charlottetown

2017 A perte de vue / Endless Landscape, Axe Neo 7, Gatineau

Goods, Living Things Festival, Kelowna

2016 What it means to be the problem? Alternator Gallery, Kelowna

2014 It Should Always be this Way, CAFKA, Kitchener

Here, to there, Access Gallery, Vancouver

2013 Vendu/Sold, Esse auction, Montreal Fine Arts Museum, Montreal

2012 Another look: 20 years of art auction, Southern Alberta Art Gallery, Montreal

2010 Manif Internationale d’Art de Québec / Architecsonic, Québec

2009 Flyvefisken, Sølyst, Denmark

How Soon is Now, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver

Blue like an orange, Ottawa Art Gallery, Ottawa

2008 C’est arrivé près de chez vous, Musée national des beaux arts du Québec, Quebec

Burrow, Musée d’art de Joliette

2007

Stop, Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery, Montreal

Burrow, Saint-Mary’s University Art Gallery, Halifax

Artefact-Montréal 2007, Montréal

Collector, Point Ephemère (FIAC), Paris

Burrow, Oakville Galleries, Oakville

2006 Nuit Blanche, Toronto

2004 I’ve done this for you, Charles H. Scott Gallery, Vancouver

2003 Bonheur et simulacre, Manifestation Intenationale d’Art de Québec, Quebec.

RESIDENCIES

2026 Odette Artist Residency, York University, Toronto

Atelier Sylex, Trois-Rivières

2024 Artists for Kids, Gordon Smith Gallery, Cheakamus

2016 Kunstlerhaüs Worpswede, Worpswede, Germany

2015 L’oeil de poisson, Quebec City

2012 Langara College Centre for Art in Public Spaces, Vancouver

2010 Avatar, Architecsonic, Québec

2009 SAIR, Sølyst, Denmark

2007 Point éphémère, Paris

LECTURES AND PANELS

2023 Situating Art in Public Space, round table, Kelowna Art Gallery

2022 Musée d’art de Joliette, Joliette

2020 Esker Foundation, Calgary

Emily Carr University, Vancouver

2018 Emily Carr University, Vancouver

Kamloops Art Gallery, Kamloops

Thompson River University, Kamloops

2017 Axeneosept, Gatineau

Emily Carr University, Vancouver

2016 Campbell River Art Gallery, Campbell River

Kunstlerhaüs Worpswede, Worpswede, Germany

2015 Oakville Galleries, Oakville

2014 Emily Carr University, Vancouver

Carleton University, Ottawa

2013 Not a new world, just an old trick: Narrative, Architecture and Art, SFU, Vancouver

2012 Conversations in contemporary art, Concordia University

Artspeak, Vancouver

2011 Other Sights / Langara College Centre for Art in Public Spaces, Vancouver

2009 Ottawa Art Gallery, Ottawa

Lethbridge University, Lethbridge

Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver

2008 Visiting artist program, Concordia University, Montreal

Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver

SFU, School for the Contemporary Arts, Vancouver

2006 Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montreal

2005 Centre d’art Skoll, Montreal

École des arts visuels, Université Laval, Quebec City

2003 Articule, Montreal Manif d’art 2, Quebec City

RECORDINGS

2010 Égarement, Quebec City Biennial

2003 Motocross: L’amour est un sentiment, C.D., Mégawatt

2001 Fonderie Darling: Cinema, Espaces Emergents, Montreal, Radio-Canada

Nager-Noyer, music at St-Michel’s Pool, Radio-Canada

1996 Kung-fu / Motocross: Main d’oeuvre, C.D., Independant

AWARDS

2021 VIVA award, The Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation for the Visual Arts, Vancouver

2015 Ontario Association of Art Galleries, Innovation in collection-based exhibition

2012 Vancouver Mayor’s Award for Public Art

Ontario Association of Art Galleries, exhibition design and installation award

GRANTS

2024 Critical Research Equipment & Tools (CRET), research grant

2021 Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

2016 Canada Council for the Arts, travel grant

2014 John R Evans Leaders Fund, Canadian Funding for Innovation (CFI)

British Columbia Knowledge Fund (BCKDF)

2013 British Columbia Arts Council

Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

2011 British Columbia Arts Council

Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

2009 British Columbia Arts Council

Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

Danish Art Council

2007 Conseil des arts et lettres du Québec, travel grant

2006 Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

2005 Conseil des arts et lettres du Québec, research grant

Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

Canada Council for the Arts, travel grant

2004 Chashama, artist-in-residence, subsidized space grant, New York

Conseil des arts et lettres du Québec, research grant

Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

2003 Canada Council for the Arts, research grant

Conseil des arts et lettres du Québec, research grant

PUBLICATIONS

Détournement, Avid Eye Productions, video, 118 min.

Samuel Roy-Bois: Presences, Kamloops Art Gallery & The Esker Foundation

Samuel Roy-Bois: Not a new world, just an old trick, Simon Fraser University Gallery, Carleton University Art Gallery, Oakville Galleries, 106 p, 2015.

Samuel Roy-Bois: Polarizer, Doherty, Ryan, Roy-Bois, Samuel, Southern Alberta Art Gallery, Lethbridge, 80 p, 2009

How soon is now, Ritter, Kathleen, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2009. Burrow, Anderson, Shannon. Oakville Galleries, 2007.

Samuel Roy-Bois: Improbable and ridiculous, Godmer Gilles, exhibition catalogue, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montreal, 24p, 2006.

INSTITUTIONAL COLLECTIONS

Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal

SFU Art Galleries, Burnaby

Surrey Art Gallery

Westbank Corporation, Vancouver

City of North Vancouver

Kamloops Art Gallery

Collection d’oeuvres d’art de l’Université Laval, Quebec City

City of Burnaby Permanent Collection

Royal Interior Hospital, Kamloops

Musée National des beaux arts du Québec

Vancouver Art Gallery