MARK THIBEAULT POPULATED

POPULATED MARK THIBEAULT

Vernon Public Art Gallery

October 2 - December 22, 2015

Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Vernon Public Art Gallery 3228 - 31st Avenue, Vernon, British Columbia, V1T 2H3, Canada

October 2 - December 22, 2025

Production: Vernon Public Art Gallery

Editor: Lubos Culen

Layout and graphic design: Vernon Public Art Gallery

Front cover: Thistle, 2023, acrylic and ink on canvas, 40 x 34 in Printing: Get Colour Copies, Vernon, British Columbia, Canada

ISBN 978-1-927407-93-6

Copyright © 2025 Vernon Public Art Gallery

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the Vernon Public Art Gallery. Requests for permission to use these images should be addressed in writing to the Vernon Public Art Gallery, 3228 31st Avenue, Vernon BC, V1T 2H3, Canada. Telephone: 250.545.3173, website: www. vernonpublicartgallery.com.

The Vernon Public Art Gallery is a registered not-for-profit society. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Greater Vernon Advisory Committee/RDNO, the Province of BC’s Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch, British Columbia Arts Council, the Government of Canada, corporate donors, sponsors, general donations and memberships. Charitable Organization # 108113358RR.

This exhibition is sponsored in part by:

1 Executive Director’s Foreword · Dauna Kennedy

2 Introduction · Victoria Verge

6 Of the Moment · Corey Hardeman

9 Artist Statement 11 Images of Artwork in the Exhibition

41 Curriculum Vitae · Mark Thibeault

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD

The Vernon Public Art Gallery is proud to present the work by Telkwa, BC artist and educator Mark Thibeault. This multi-talented musician and artist began work on the exhibition Populated during the COVID pandemic. Known for his large-scale abstract paintings, Thibeault likes to explore moments of intersection between nature and people. This publication captures a selection of his latest work which will also be on display at the VPAG.

I’d like to thank our guest writer, Corey Hardeman for her insights into Populated and the artist herself. Hardeman is an artist and educator teaching out of the College of New Caledonia where she contemplates on issues surrounding climate change and Anthropocene.

A big thank you to our out-going Curator, Lubos Culen for all his contributions to the curatorial program at the Vernon Public Art Gallery, including this exhibition with Mark Thibeault. Victoria Verge has joined Lubos in curating this exhibition and we welcome her in this role.

I would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Province of British Columbia, the Regional District of the North Okanagan, and the BC Arts Council, whose funding enables us to produce exhibitions such as this for the residents and visitors of the North Okanagan region and interested parties across Canada.

We hope you enjoy this exhibition and accompanying publication.

Regards,

Dauna Kennedy Executive Director Vernon Public Art Gallery

MARK THIEBAULT: POPULATED - INTRODUCTION

Abstract painting occupies an uneasy position in art history. Once hailed as the summit of modernist achievement, particularly through the dominance of Abstract Expressionism in the mid-twentieth century, it has since been critiqued for its insularity, its gendered narratives of genius, and its uneasy relationship to politics and place. To paint large-scale abstractions today is to knowingly enter into this contested legacy, at once participating in a tradition and pushing back against it. Mark Thibeault’s work embodies this tension. His practice acknowledges the vitality of gestural abstraction while simultaneously recasting it through a lens of musicality, improvisation, and ecological awareness.

The story of Abstract Expressionism in North America is one of ambition and contradiction. Artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Barnett Newman sought to wrest painting away from representation and toward pure experience. Their canvases were read as records of psychic intensity, as if the very act of painting could capture the drama of existence. Yet, the narrative of abstraction’s triumph (especially as exported from New York) also tended to eclipse other voices: women artists like Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell, regional painters outside of the metropolitan core, and Indigenous or non-western practices that did not fit the model of the heroic modernist breakthrough.

In Canada, the Group of Seven had already established landscape as a national idiom, and abstraction was often framed as either a rejection of, or evolution beyond, that tradition. Painters such as Jack Bush and the Painters Eleven worked in dialogue with American modernism but also sought to situate abstraction in relation to Canadian light, land, and sensibility. Still, the discourse around abstraction often reproduced the same rhetoric of universality and transcendence that critics have since challenged. What, after all, does it mean to claim universality when painting emerges from specific geographies, histories, and identities? It is against this backdrop that Thibeault’s practice takes on significance. His work is not naïve to abstraction’s heavy inheritance; rather, it lives in the afterlife of abstraction, acknowledging both its power and its limitations.

Thibeault’s artistic life extends beyond painting, he is also a musician and luthier, and this musical sensibility permeates his canvases. Where Abstract Expressionism often valorized the singular, agonistic gesture, Thibeault treats gesture as improvisation, akin to a musician following a riff or phrase. His marks accumulate rhythmically, looping and swerving like a melodic line. The result is less about asserting dominance over the canvas and more about following where the medium leads, allowing accidents, hesitations, and detours to shape the composition. This approach situates Thibeault within, but also apart from, the Abstract Expressionist lineage. If Pollock’s drip paintings were celebrated as a triumph of control through chaos, Thibeault’s canvases lean into the instability of mark-making. He courts dissonance as much as harmony. His

paintings do not arrive at a singular resolution but remain in flux, echoing his own statement that adaptation and improvisation are central to his process. In this sense, he reclaims abstraction not as the site of heroic assertion but as a space of open-ended dialogue.

A common critique of abstract painting is its claim to transcend the particularities of subject matter, history, or identity. Abstract canvases, critics argued, could be “pure” art, free of narrative or cultural baggage. Yet, this supposed universality often masked the biases of its time: the dominance of male artists, Euro-American institutions, and the Cold War geopolitics that promoted abstraction as a symbol of freedom. Thibeault’s paintings complicate this idea of universality. While his works are not representational in a traditional sense, they are deeply informed by his surroundings in northern British Columbia. His palette and compositional energy are shaped by the biodiversity and shifting ecologies of the region. Rather than claiming to speak for all humanity, his abstractions are rooted in a dialogue with place: the fragility of ecosystems, the precarious balance between human and natural worlds, the traces of memory embedded in land. In this way, his work underscores that abstraction is never neutral — it is always entangled with context.

One of the most striking aspects of Thibeault’s recent work is its ecological resonance. The Populated series reflects his awareness of shifting land use policies, resource pressures, and the fragility of ecosystems. Abstract painting has often been criticized for its detachment from urgent social and environmental concerns. Yet, Thibeault folds these realities into his abstractions, not through direct representation but through sensibility. His work becomes a meditation on connection and disconnection, on the interplay of resilience and vulnerability in both human and natural systems. This ecological orientation aligns Thibeault with a broader contemporary movement in Canadian art, where abstraction is being rethought in relation to land and environment. Artists today increasingly refuse the old divide between “pure” abstraction and environmental consciousness, instead exploring how non-representational forms can evoke ecological fragility, resilience, and interdependence. Thibeault’s paintings contribute to this conversation, suggesting that abstraction remains vital when it acknowledges its embeddedness in the world.

Corey Hardeman has aptly described Thibeault as a sensualist. His canvases brim with a corporeal energy that recalls the physicality of painting itself: brushstrokes that are athletic, gestural, sometimes delicate, sometimes forceful. Unlike the aloof coolness that characterized later forms of abstraction (such as Colour Field painting), Thibeault’s works insist on embodiment. They invite the viewer to see, but also to feel, to register the painting as a form of physical knowledge. This emphasis on embodiment is another way in which Thibeault revises the legacy of Abstract Expressionism. While critics often framed the canvases of Pollock or de Kooning as heroic struggles of the male body, Thibeault’s engagement with the body is less

about dominance than about vulnerability. His paintings expose their own fragility: marks wander, stutter, or dissolve; colours brush against one another without fusing into harmony. The result is less an assertion of mastery than a recognition of instability, echoing his pandemic-era shift toward smaller, more intuitive gestures.

To write critically about abstract painting is to ask why artists still pursue it. After decades of critique, what remains to be said through abstraction? Thibeault’s practice offers one possible answer. His paintings neither reject abstraction outright nor rehearse its mid-century tropes. Instead, they inhabit its afterlife — accepting its legacies while refusing its grandiose claims. They demonstrate that abstraction can still matter when it foregrounds improvisation over mastery, vulnerability over heroism, and ecological entanglement over universality. In this sense, Thibeault’s work exemplifies a different ethos of abstraction: one that listens rather than declares, one that adapts rather than asserts. His canvases remind us that abstraction need not be an escape from the world; it can be a way of grappling with its fragility, complexity, and constant flux.

Victoria Verge Curator

Vernon Public Art Gallery

MARK THIBEAULT - OF THE MOMENT

by Corey Hardeman

Mark Thibeault is a sensualist. His paintings are abstract and figurative, expressionist and classical, and the thread that winds and loops between them all is that questioning exploration, that physicality, the song and the dance of the sensual. His palette ranges from the bright, cheerful hues of children’s stories to the greys and ochres of deep history.

Thibeault is a polymath; a musician and a luthier as well as a painter, each of his professions feeding all of them. This synthesis is apparent in the rhythmic quality of his pictures, in the musicality of his mark making. There is a cartographic aspect to these pieces: a sense of being located in the surface, that the painter follows each mark like a dog on a trail, not knowing what waits at the end, that each mark is a placeholder, a searchlight, a landmark. He is Theseus entering the labyrinth, the paint his ball of thread. He lets paint lead him through vistas of delight and confusion, of sex and birth and longing and death, of time itself.

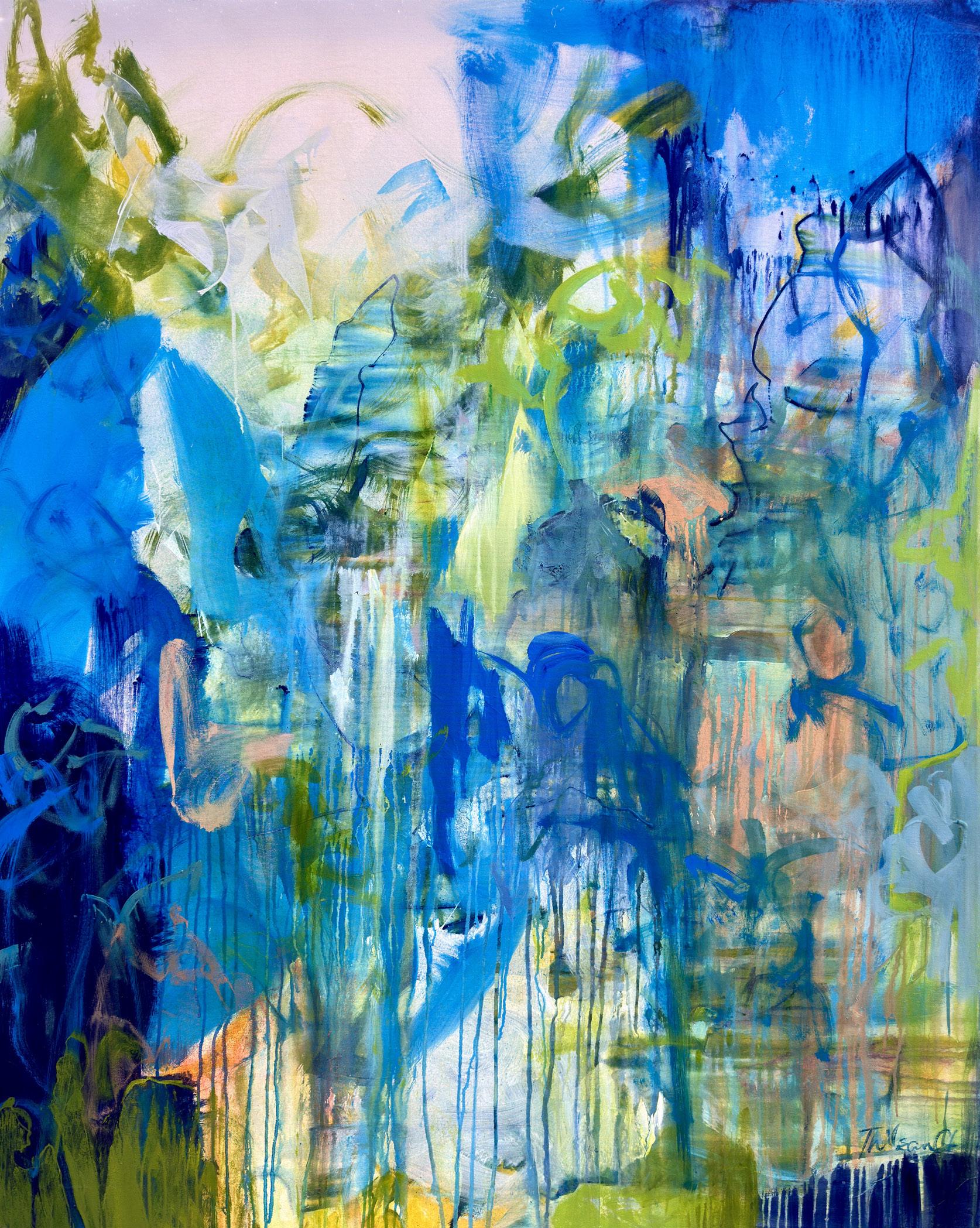

In many of these pieces, hectic marks organize themselves into nearly familiar forms. They brush up against the edge of the representational, then slide away again, neither embracing nor rejecting, simply acknowledging and moving on. In Thistle, the impression of the skull swims in a scrim of blue and green, algal and teeming, ringing with echoes of Francis Bacon’s pope paintings, reaching back through time to Velazques and forward again to our own teetering mortality, here on the brink of apocalypse. This motif is further elucidated in When the Smoke Clears, a painting that immediately calls to mind images of catacombs, of memento mori: an earthy painting which is disrupted and ultimately contained and defined by a swirling, heaving ribbon of celestial blue. Between that heavenly blue and the forms of decay, the viewer is caught and held for the moment.

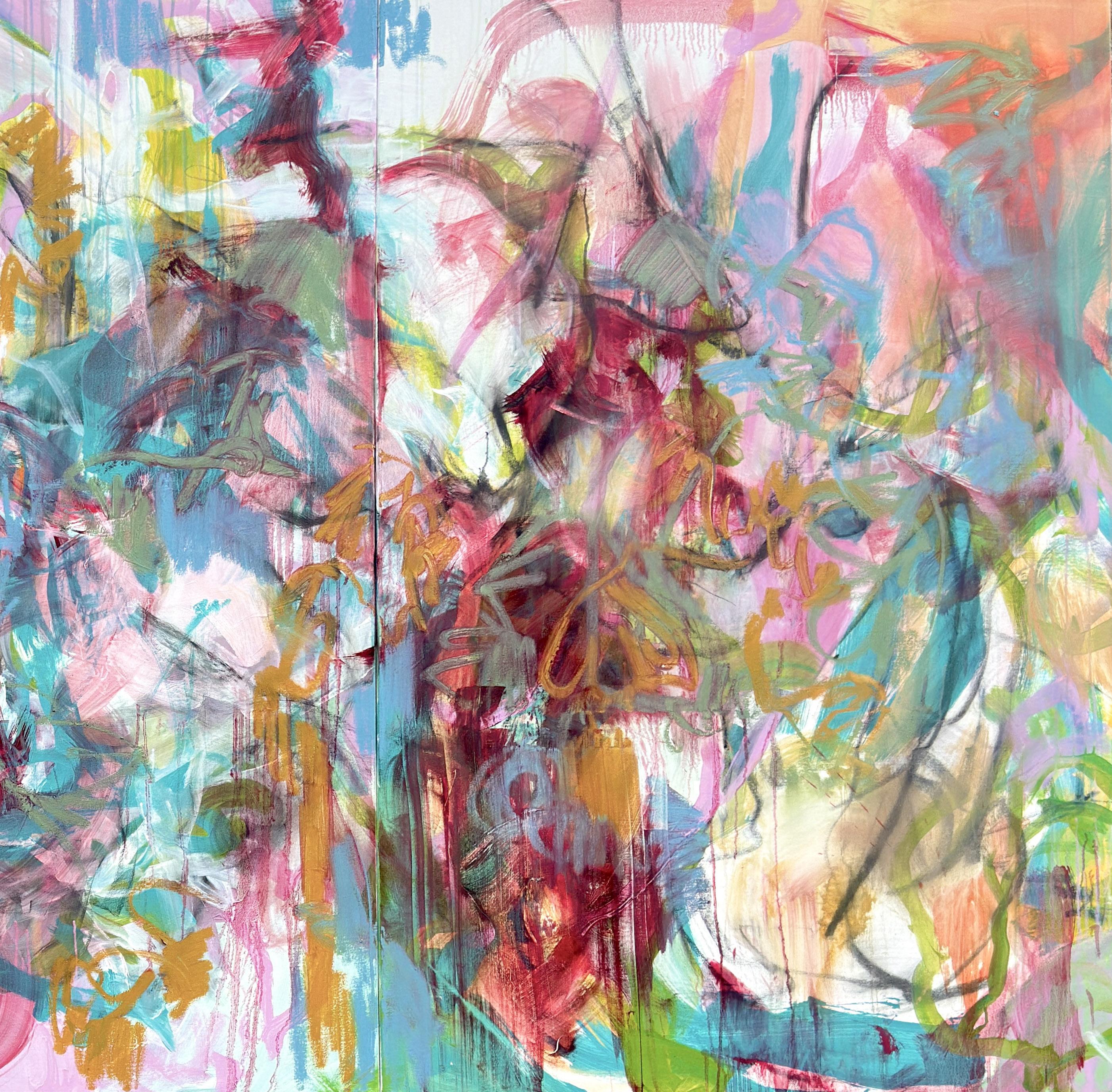

The Quickening, a massive triptych in candy colours, evokes both a feeling of a mad dash, a frenzy of scribbles and brush strokes, and of a far more literal relationship to its title. In pregnancy, quickening is the moment when a fetus’ movements become sensate to its mother. The word denotes a fluttering, an unpredictable, alien sensation, both intimate and strange. The scale of the painting is a stage for its maker. It is a gymnastic work, and cannot be perceived without an acute awareness of the physical effort of its creation, and in this way it again connects to its title, to the physicality of paint, to the embodied nature of art making.

Thibeault’s influences are various and eclectic. The abstract expressionists mingle with the romantics and the impressionists; Fragonard and Matisse walk into a bar and de Kooning pours the drinks. Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec nod from the back corner at the turn of a line that suggests a wrist, an ankle, a breast, a mark that resolves itself in dance. The mark is a call and the colour is the response, and while the paintings sing the litany of their muses, they are confidently themselves. Grounded in the present, they know where they came from. History breathes through this work.

In Cave Painting, this call to history is instantly apparent. Thibeault uses colour alone to invoke the paleolithic paintings of Altamira and Lasceaux. Ochres and greys anchor abstract shapes- smudges and scribbles that function as a mnemonic, immediately calling to mind the familiar shapes of the prehistoric horses, the mammoths and woolly rhinoceros that populate the ancient walls. It is a wordless explication of the deep human urge to document the world we know with paint. It is, moreover, a reminder that all art is alive, that every painter communes with the painters of the past and with painters yet unborn, that to paint is to speak through time and to listen for its answering echoes.

Each of these paintings is an “all over painting”. They are sprawling pieces, big and meandering, a generous expanse over which the artist travels, reconsiders, changes direction. It is possible to see the speed with which each mark is made, from the frenetic staccato to the languorous and thoughtful line. They wander across their substrates, asking and answering, wondering and remembering. They are not authoritative, they have no agenda; rather, they are organic, probing, pushing their way up through line and wash like dandelions through the cracks in a sidewalk. They are ungovernable, messy, inevitable, and they are lovely. Their beauty is the chaotic beauty of a second growth forest, new shoots competing with one another, fungi and fireweed giving way to willows and roses.

We Were Not Alone in the Garden is just such a fertile jumble. Warm pinks are juxtaposed with swirling greens, and palette and gesture both suggest a fervent, groping abundance. These are the colours of midsummer, juicy and humid. A bend here and a turn there might be a hip, the back of a knee, a throat- the painting is gaspingly erotic without ever resorting to illustration. Like Cave Painting, it employs the loosest suggestion to plant the image, and the viewer is made a voyeur, the painting is sown in the canvas but blooms in the mind.

Bacchus tugs at the strings of Garden’s apron and flesh and form tumble out. In this painting the bodies are undeniable. They writhe together, they roll across one another, elbows and ribs and a twirling line that can only be a nipple; this is the kind of painting that makes a person wonder whether they are the only one with a filthy mind. It is an orgy, surely, even someone who has never really thought about orgies can see that. But can they? Pink and yellow and pale blue are not intrinsically carnal colours, but that whorl at the upper left still says nipple, that long twisting line still says ecstasy.

This is the power of Mark Thibeault’s painting. It is thoughtful, yes, it knows its history, absolutely. It nods to its influences but is not bound by them, it acknowledges the material conditions in which it was made but is not beholden to them. But the spark that travels between these pieces is not merely intellectual, it is sensual, it is sensational. These paintings are evocative in the true sense of the word. The viewer is complicit

in their fulfillment. Looping lines suggest written language, suggest bodies, suggest plants and sunrises and animals, but none of these is explicit in the work itself. The work whispers and the imagination cries out in response “I know this!” and the knowing is private, sometimes voyeuristic, sometimes poignant. It takes courage to ask a question without having the answer in advance, it takes honesty and humility, and these paintings are full of questions. Of course, the question of now is why bother at all? Why make art at the end of the world? And this question is one that Thibeault answers resoundingly: because we are art making animals. Because art is the song we sing to life, the oldest song we have, the song that holds out hope for the unknowable future.

Corey Hardeman is an artist and educator living in the north central interior of British Columbia, a geography that informs all her art making. She teaches painting and drawing at the College of New Caledonia in Prince George. In addition to her studio practice, she gives talks and leads workshops about the role of art in the era of climate change. She is a published author of many essays on subjects pertaining to artmaking in the Anthropocene era.

Hardeman’s paintings are focused on the landscape she inhabits. While she is concerned with moral and aesthetic questions imposed upon the landscape by industry and changing climate, she approaches the landscape as an intimate, ongoing, living entity. In her artmaking, she immerses herself in the discovery of changes and focusing her subject matter to reveal the chaos and beauty of the expansive natural world that surrounds us.

ARTIST STATEMENT

The Populated series is inspired by themes of connection, disconnection and transformation.

I am interested in the changing connection and separation of the human experience from the natural environment and how each reacts to the others changing influence and needs.

The notion of constant change, adaptation and improvisation is part of my creative process.

This ongoing series began in 2020. During the pandemic, my practice shifted moving toward smaller, more intuitive gestures. It was an unintentional but vital response to uncertainty, and it reminded me of the power of art to ground, connect, and carry us forward.

The expressive paintings in this series are inspired by the rich biodiversity of northwest British Columbia and the idea of self and how we relate to each other and our immediate surroundings.

References to landscape in these paintings sit within the broader tradition of Canadian landscape painting, but reflect a shift from celebrating nature’s grandeur to acknowledging its fragility. With contemporary land use policies constantly evolving, and increasing international interest in our natural resources, I have become more aware of our collective impact on the land. These works are not about a fixed place, but about the ways we interact with and change the landscapes we live within. I am reminded constantly of the fragility of ecosystems and of our responsibility to them.

The notion of constant change, adaptation, and improvisation runs throughout this work. Populated reflects both personal and collective narratives, shaped by shifting internal and external landscapes. While the work holds space for uncertainty and fragmentation, it also points toward empathy, resilience, and a sense of shared responsibility.

Mark Thiebeault August 2025

ARTWORK IN THE EXHIBITION

Bacchus 2025, acrylic and ink on canvas, 72 x 96 in

Blue Squid 2024, acrylic and ink on canvas, 48 x 36 in

Cave Painting

2025, acrylic, ink and charcoal on canvas, 60 x 84 in

Forte 2024, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 in

Libretto 2024, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 in

Milonga 2024, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48 in

Pianissimo 2024, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 in

Salvajes 2025, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 60 x 48 in

The Quickening, 2025, acrylic and oil on canvas, 60 x 120 in

Thistle

2023, acrylic and ink on canvas, 40 x 34 in

Watcher

2024, acrylic, ink and oil on canvas, 48 x 36 in

We Were Not Alone In the Garden 2025, acrylic and oil on canvas, 72 x 96 in

When The Smoke Clears

2025, acrylic, ink and oil on canvas, 60 x 40 in

Wolf Wears Silk 2025, acrylic and ink on canvas, 60 x 48 in

MARK THIBEAULT CURRICULUM VITAE

Mark Thibeault’s practice extends across painting, music and lutherie. Working from his Telkwa studio in northern British Columbia Canada, he is inspired by the natural environment, and how it and human experience both continually adapt to the other’s changing influence and needs.

The notion of constant change, adaptation and improvisation is part of his creative process. His expressive paintings are a collection of experiences finding their way to be witnessed as a mark - an intuitive unveiling or revealing of the inherent linear compositions woven through our perception of the world and our interactions within it.

Thibeault studied for a BFA Honours in visual arts at the University of Windsor, Ontario (1992).

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2025 Populated, Vernon Public art Gallery. Vernon, BC

History of Postcards, Crowsnest Pass Public Art Gallery. Frank, AB

Populated, Bugera Lamb Fine Art. Edmonton, AB

2024 Postcards From The Pacific, Terrace Art Gallery, Terrace, BC

Postcards From The Pacific, Museum of Northern BC. Prince Rupert, BC

2022 Archetypes and Allegory, NoonPowell Fine Art, London, UK

Populated, Aesthete Fine Art, Prince George, BC

Populated, Smithers Art Gallery, Terrace, BC

2021 Populated, Terrace Art Gallery, Terrace, BC

Coastal Influence, Terrace Art Gallery, Terrace, BC

2021 Succession, Two Rivers Art Gallery, Prince George, BC

2020 Cycles, Museum of Northern BC, Prince Rupert, BC

2019 A Line Collected, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

2013 Home, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2025 Summer Exhibition, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

Affordable Art Fair, Battersea, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

Affordable Art Fair, Hampstead Heath, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

2024 Affordable Art Fair, Battersea Autumn, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

2023 Skeena Salmon Art Show, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

Skeena Salmon Art Show, Kitimat Museum, Kitimat, BC

Skeena Salmon Art Show, Terrace Art Gallery, Terrace, BC

Affordable Art Fair, Hampstead Heath, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

2022 Affordable Art Fair, Battersea, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

2020 Christmas Show, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

One of a Kind, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

Visual Variations, Noon Powell Fine Art, London, UK

Summer Show, Noon Powell Fine Art, London UK

Members Show, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

2019 One of a Kind, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

2019 Bulkley Valley Artisans Tour, Home Studio, Telkwa, BC

Art Works, Vancouver, BC

2019 Wintergrass, Bellevue, Washington

2018 Bulkley Valley Artisans Tour, Home Studio, Telkwa, BC

2017 6X6 Auction, Smithers Art Gallery, Smithers, BC

Studio 16, Smithers, BC