Wages for Housework

Wages for Housework

The Story of a Movement, an Idea, a Promise

Emily Callaci

an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Emily Callaci, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 12/14.75pt Dante MT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–50290–7

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

List of Illustrations

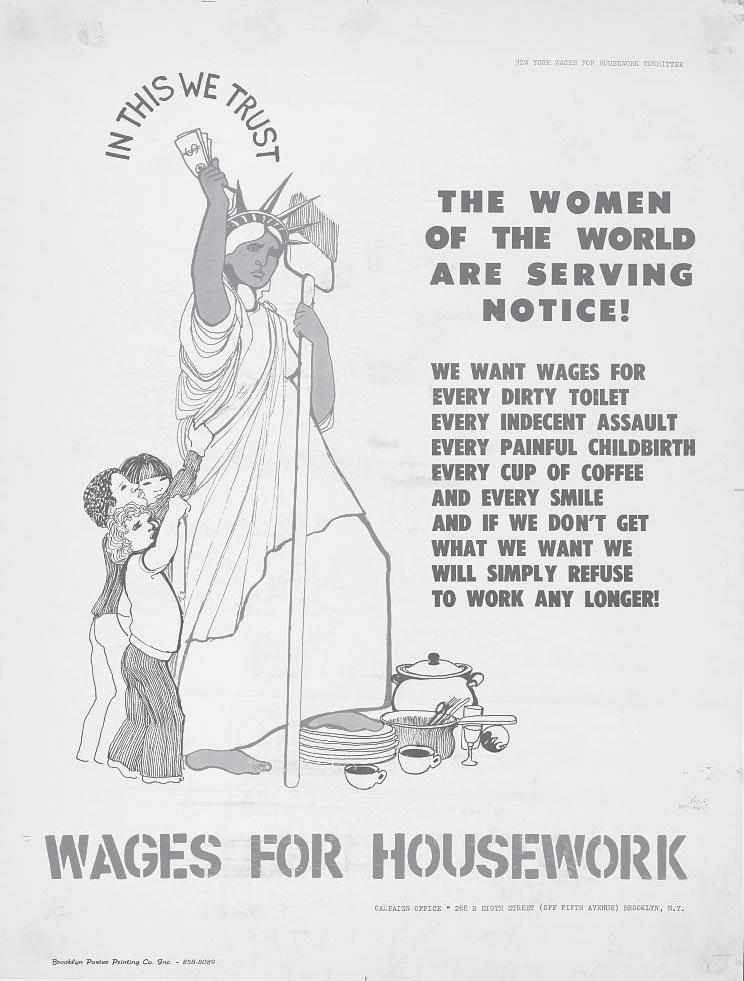

Introduction: New York Wages for Housework Committee Poster (Library of Congress)

Chapter 1: Selma James speaking in 1970 at the National Women’s Liberation Movement Conference at Oxford’s Ruskin College.

© Chandan (Sally) Fraser

Chapter 2: Mariarosa Dalla Costa in Toronto in 1973. © Archivio Mariarosa Dalla Costa

Chapter 3: London Wages for Housework Committee Storefront, circa 1976. © Linda Law

Chapter 4: Musical performance at a Salario al Lavoro Domestico/ Wages for Housework demonstration in Mestre in 1975. © Archivio Mariarosa Dalla Costa

Chapter 5: Silvia Federici at a Wages for Housework meeting in Brooklyn, circa 1976. © Linda Law

Chapter 6: The New York Wages for Housework Committee at the 1977 International Women’s Day March in New York City

© Linda Law

Chapter 7: Wilmette Brown speaking at the 1977 International Women’s Day March in New York City. © Linda Law

Chapter 8: Margaret Prescod (center) shaking hands with Johnnie Tillmon and Beaulah Sanders at the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston. © Diana Mara Henry

Chapter 9: The Wages for Housework table outside the Peace Tent at Forum ’85, the U.N. International Conference on Women, in Nairobi ©Getty Images

Introduction

A poster created by the New York Wages for Housework Committee in 1974, inked in red-and-blue stencil, proclaims: “The women of the world are serving notice! We want wages for every dirty toilet every indecent assault every painful childbirth every cup of coffee and every smile. And if we don’t get what we want, we will simply refuse to work any longer!” In the center of the poster stands the Statue of Liberty, her face weary, a broom in one hand and a fistful of cash in the other. Children grab at her robes, and dirty dishes lay stacked up at her feet.1

Some years back, I ordered a print from the Library of Congress,

New York Wages for Housework Committee Poster (Library of Congress)

Introduction

framed it, and hung it in my living room. I acquired it as a kind of curiosity; an attractive vintage artifact of 1970s feminism, and a provocative conversation piece. It is directly in my line of vision from my place at the kitchen counter where I mix smashed banana into oatmeal for my sons’ breakfast, or portion extracted breastmilk into 4oz bottles to be sent with the baby to daycare. It hovers in my peripheral vision as I, toddler plopped in my lap, read I Am a Bunny aloud for the tenth time in a row, and when I am bleary-eyed at the kitchen table with my laptop late at night after my kids are in bed, preparing a lesson plan for class the next day. I’ve thought about the concept often: Wages for Housework. In the duller moments of my life, it awakens something in my imagination, connecting my daily efforts to lives and labors beyond the four walls of my house.

For most of my life, I did not think very much about housework. A middle-class teenager in the “Girl Power” 1990s, I learned that my liberation would come through education, creative expression, and professional success. Thanks to the efforts of feminists who came before me, I never felt I had to rebel all that hard against the expectation of feminized domesticity. I intended to spend my time on earth on more meaningful things: love, politics, music, beauty. What did housework have to do with me? It seemed like a quaint preoccupation – the relic of an older generation’s outdated and irrational beliefs about gender. That women were associated with housework seemed a category mistake: correct that mistake, and you fix the problem.

But then, when I became a mother, housework became inescapable. I experienced the housework of motherhood differently than my mother, who quit her job as a social worker to raise me and my brothers until my youngest brother was old enough for school. I remember her at the dinner table in the evenings with the three of us while my father was out, doing what I imagined as very romantic work as a union organizer. In stories about my father’s childhood, I picture his mother, my brilliant grandmother, who left a job as a journalist when her first child was born, tending lovingly and

Introduction

skillfully to five children, often while my grandfather wrote poetry in his attic study. (She returned to journalism when she was in her sixties, after her children were grown.) When their children were school-aged, both my mother and grandmother became publicschool teachers, choosing careers that adapted to the rhythms of their children’s lives. These images of my mother and grandmother invoke in me feelings of warmth, safety, and love. Still, I never expected to play a role similar to them. It seemed unproblematic to me to identify with the men and their work: I’d emulate the union organizer, the poet.

I have not had to fight all that hard against an expectation that, as a woman, I should do a disproportionate amount of housework, yet housework is nevertheless a struggle that I share with my partner. In at least one way, our household is typical for our generation of Americans: both adults in our house work full-time outside the home for money, and the work of maintaining our family gets squeezed into the time that is left after we’ve satisfied the demands of our employers.2 We live in a country that, over the past few decades, has collectively experienced declining real wages, shrinking social services, and rising costs of education and healthcare. We negotiate housework between us (as I write these words, he is at home with our two boys while I sit alone in my friend’s empty house to write free from distraction), but we also distribute it beyond us. To be able to work, we rely on paid childcare; to pay for childcare, we need to work; and this entire cycle relies on the fact that the extremely skilled women who care for our children are paid less money for their work than we are for ours. There is no way around it: I am a beneficiary of an exploitative social arrangement. By participating, I also feel that I am undermining myself: I consent to a world in which the work of caring for children – the work that, for the past few years, I have spent most of my time on – is valued less than the work of being a professor.

Housework weighed most heavily on me when I returned to my full-time job as a history professor, four months after my first son was born. If housework is work– and it certainly was work in the

Introduction

physical meaning of the word – then together with my paid job, I was working eighteen-hour days. These were clearly poor working conditions. I know from growing up in a union family that one of the most effective ways to contest poor working conditions is by going on strike. But the feminism I grew up with had put me in a bind: if feminism was the right to pursue success and equality in the workplace, then to refuse my salaried job was to refuse the very thing that I had learned was the source of my liberation, autonomy, and sense of accomplishment. To refuse the work of caring for my child would be to harm the most vulnerable of beings, and the person I loved most in the world. Parenting young children during the pandemic only deepened my growing sense of a loss of power: that motherhood, the work that I knew I could never refuse, made me vulnerable to exploitation.

I was drawn to Wages for Housework because I wanted to understand what had changed in my life, and to make sense of my mixed feelings about it. Put another way, I wanted to understand how motherhood had changed my relationship to capitalism. And I wanted alternatives. I turned to feminist writings from the 1970s, wondering how the diverse, ambitious, imaginative, revolutionary ideas of that generation had gotten narrowed into the version of feminism that had been offered to me as a young woman. One of the places I looked for insight was in Silvia Federici’s 1975 manifesto “Wages Against Housework,” a rousing and elegant call to confront housework head-on as a site of women’s systemic oppression, rather than imagining that, as individuals, we can find a way out of it.

Around that time, I learned that Silvia Federici was assembling her archive at Brown University, located in the town where I grew up and where my parents still live. So, on a long visit during my maternity leave, I left my son and several bottles of extracted breastmilk with my mother while I went (breastmilk pump in tow) to explore Federici’s collection of writings, manifestos, and gorgeous black-and-white photographs of women marching in the streets of New York and London and Rome. One flyer from the New York

Introduction

Committee seemed to address me directly. In it, they demanded support for the work of mothering in the form of collectivized daycare, subsidized by the government, not in order to free mothers up to work harder at our jobs, but to free us up for . . . whatever the hell we want. A nap. Art. A swim in the ocean. Slow, luxurious sex. Time to nurture our friendships. Time to participate meaningfully in politics. Having grown up with a feminism that equated liberation with the right to pursue success at work, this was a revelation: a feminism that was unabashedly anti-work.

Silvia Federici’s archives led me to other feminist thinkers in the Wages for Housework campaign: Mariarosa Dalla Costa, the student militant who started the Italian Salario al Lavoro Domestico campaign in the wake of Italy’s wave of wildcat strikes and student uprisings; Selma James, wife and comrade of the Trinidadian Marxist C. L. R. James, who launched a Wages for Housework campaign out of their apartment in London; Wilmette Brown, a poet and former Black Panther who, together with the Barbadian community organizer Margaret Prescod, launched Black Women for Wages for Housework in Brooklyn and Queens.

I started from questions about my own life, but Wages for Housework took me far beyond it. Housework is everywhere, once you start looking for it.

Feminists launched the Wages for Housework campaign in 1972. But the word “campaign” doesn’t quite capture it. Wages for Housework is perhaps best understood as a political perspective, which starts from the premise that capitalism extracts wealth not only from workers, but also from the unpaid work of creating and sustaining workers. An employer who hires an employee gets more than what they pay for: they get the labor of the person who shows up to work, and they get the labor of a second person who is at home sustaining him (for in the early writings of the campaign, the waged worker was presumed to be a “him”). That second person feeds the worker, makes his home livable, does his laundry, does the shopping, nurtures his body and soul, raises his children. It is all this

hidden labor that makes it possible for him to come to work all day producing profit for his boss. Housework is, therefore, not unproductive or external to the economy. It is the most essential part of the capitalist system because it produces and maintains the most important source of value: the worker. Yet those who perform this work are not entitled to a share of the wealth they create. To the contrary, they are often among the most impoverished and dependent members of society.

The systemic exploitation of women’s unpaid work is hidden by a powerful myth: that women are naturally suited to housework. For a woman, keeping house and caring for family fulfills her natural desires, and should be reward enough. Compensation would sully the virtuous nature of this work, for the home is imagined as a refuge from the impure, punishing world of work and market relations. Capitalism relies on this myth to keep women in these roles, allowing others to profit from their work. Wages for Housework was so jarring to people because it demanded compensation for something that was supposed to be free from market forces, and which women were supposed to provide out of love. Campaign members saw this as a form of emotional blackmail. As one of my favorite Wages for Housework slogans sums it up: They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.

By demanding payment for work that women had historically done for free, members of the Wages for Housework campaign made visible their role in capitalism. They aimed to destroy what they saw as a false distinction between work done in the marketplace for wages and unpaid housework done in the home and community. In so doing, they aimed to call into being a truer, more expansive, inclusive working class to dismantle capitalism and all its forms of oppression.

Wages for Housework is a critique not only of women’s oppression, but of global capitalism in its entirety. It argues that, because women do housework for free, work that resembles housework is undervalued: the more similar a job is to housework, the lower its status and the less it is paid. Moreover, when governments cut social

services, such as childcare, education, healthcare, elder care, and disability services, they exploit the fact that women will step in and provide these services without pay. The analysis can be applied at a global scale. The scholar-activist Andaiye, who launched a Wages for Housework campaign in her home country of Guyana in the early 2000s, applied the perspective to structural adjustment policies: the austerity measures imposed by the IMF and World Bank on countries in the global south as a condition for foreign aid and bank loans. With stunning clarity, she writes: “Structural adjustment . . . assumes correctly that what women will do in the face of the deterioration that it brings is to increase the unpaid work that we do without even thinking about it in an attempt to ensure that our families survive.”3 Wages for Housework puts austerity politics in a new light: what politicians call fiscal conservatism or “belt-tightening,” Wages for Housework reframes as freeloading on the unpaid work of women.

Wages for housework is a strategy not just for unwaged workers, but for all workers, for we are all affected by housework’s unwaged status. In the 1970s, the Wages for Housework campaign argued that men were made vulnerable in the workplace by their wives’ financial dependence on them. If a worker wants to demand better working conditions, or go on strike, having a wife with no income makes it harder for him to assert himself: to do so would put his entire family at risk. Moreover, a woman working outside the home has more power in her workplace if she is already paid for the work she does at home: she has negotiating power to decide the terms on which she will take on additional work, and she can refuse shitty, demeaning jobs without the threat of complete destitution that is so often used as a stick to discipline poor and working-class mothers. Wages for Housework is not wages for housewives: it is bargaining power to the working class as a whole. It begins by redefining “working class” with unpaid women’s work at the center.

Wages for Housework was controversial when it was proposed in the 1970s. Few feminists disagreed with the insight that housework

Introduction was essential, and hidden, and that it would be politically powerful to recognize it. But many were uncomfortable about the money part. Some argued that it would invite capitalism into their homes, bringing even more areas of life into the wage relation and commodification. Others chafed at the suggestion that, having struggled so hard to escape housework as their destiny, women should then identify with housework by demanding payment for it. The most common critique was that wages for housework would institutionalize women as housewives, doubling down on the link between women and housework, rather than destroying it. Many struggled to understand: how does getting paid for housework allow you to refuse that work? If you are demanding to get paid, aren’t you then agreeing to do that work?

In the history of the campaign, I have encountered ambiguity on this point. Some have stated that the money was never the goal, but rather a provocation that aimed to change consciousness and catalyze social transformation. By contrast, others in the campaign have insisted that the money is the most important thing: Wages for Housework is not an intellectual exercise, they insist, but a fight to get money into women’s hands. What members of the campaign all agree on is that the wage was never the end goal but rather the first step in a much larger struggle for power. This is why the word “wage” was so important. When Margaret Prescod, founder of Black Women for Wages for Housework, used her platform at the historic 1977 US National Women’s Conference to insist that welfare be called a wage rather than a benefit, more than semantics was at stake. To recognize that welfare is payment for the work of mothering, rather than poverty alleviation, changes the entire political relationship. Wages for Housework reframes women’s poverty as systemic impoverishment: women are not unfortunate victims in need of charity, rather, they are exploited workers in need of justice.

By my count, there were Wages for Housework branches in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, France, Switzerland, Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana, and their influence

xvi

reaches far beyond. As the idea spreads, it inspires new forms of action. Recently, a women’s collective in Andhra Pradesh with connections to the campaign demanded support for their work replenishing the land, protecting it from extractive industries that pollute the environment and contribute to global warming. Some advocates for a Green New Deal, in both Europe and the United States, cite Wages for Housework in their vision of an economic model that centers care for human beings and the environment, as an alternative to the relentless planet-destroying production of commodities. In a project called Wages for Facebook, artist Laurel Ptak provokes users of social media to demand a share of the wealth created through the mining of their personal data. Some prison abolitionists, whose demands include divesting from prisons and policing and reinvesting in community carework, name Wages for Housework as an influence. At the 2011 International Labor Organization Conference that successfully passed Convention 189, known as Decent Work for Domestic Workers, recognizing the rights of domestic workers as workers and the home as a workplace, one of the advocates who took the stage was Ida LeBlanc, daughter of Clotil Walcott, founder of Wages for Housework in Trinidad and Tobago. In my own neighborhood, activists are organizing for a more just and healthy food system in my son’s public school, starting with revaluing the labor and skill of cafeteria workers, most of whom are economically marginalized women. I am delighted, and unsurprised, to learn that Wages for Housework is one of their guiding lights.

Despite its influence, the Wages for Housework campaign itself was small, with never more than a few dozen members. They were multi-racial and international. Many of them were lesbians. Some were disabled. They included sex workers, welfare mothers, and nurses. Few of them were “housewives” in the conventional sense. They were seen by many as quirky, even cultish. They appear often in oral histories of second-wave feminism as a kind of curiosity. A commonly told story recounts how someone would stand up at a public meeting and identify themselves as part of the Wages for

Introduction

Housework campaign, eliciting a collective groan from audience members, who knew they were in for another long lecture about capitalism and housework. A 1975 article in the Guardian compared them to Jehovah’s Witnesses.4 People often didn’t know what to make of them.

If in the 1970s their ideas seemed outlandish, today they seem less strange. I assign Silvia Federici’s essay “Wages Against Housework” to my undergraduate students, and though they are nineteen and twenty years old, mostly unburdened by housework in the traditional sense, they immediately find themselves in Federici’s analysis of capitalism. My students question the constant demand for productivity. More than my generation, they grew up aware of the looming threat of climate catastrophe and are primed to see what relentless economic growth and “productivity” has done to the planet and to human thriving. Most are starting out their adult lives saddled with debt and wonder why they are cast in the role of debtors to our society, rather than as contributors to our collective wealth. If my generation believed that the upward escalator toward education and a career would set us free, I find that many of my students are decidedly more skeptical.

My fascination with Wages for Housework arose out of a desire to understand my own life, but it has led me to much bigger, more ambitious questions. What would it be like to live in a society that rewarded the care of people and their environments as much as the production and consumption of commodities? What kind of relationship to the natural world could we have if, rather than emphasizing productivity and growth, we uplifted maintenance and repair of environments – in other words, housework? What new experiences of love, kinship, desire, and pleasure would be possible if we were not pressed into isolated nuclear family units, each responsible for its own housework? What if our cities and towns were designed to nurture vibrant intergenerational communities, rather than centering on the mobility of the able-bodied “productive” worker? How would geopolitics and the global distribution

xviii

Introduction

of wealth be transformed if governments had to recognize their indebtedness to the unpaid work of women with the same gravity with which they recognize their debts to financial institutions? Perhaps most basic: what would the women of the world do with their lives if they had more time?

This book explores the ideas and work of five women: Selma James, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Silvia Federici, Wilmette Brown, and Margaret Prescod. Admittedly, by choosing this format, I contradict a feminist principle held dear by many members of this movement: that political ideas are the products not of individual “geniuses,” but of collective action and struggle. It’s true that none of these women worked in isolation, and I hope that this book offers a glimpse of what is possible when women work together across various boundaries, devoting their effort and imagination to a common purpose. At the same time, Wages for Housework is not monolithic. I chose to write about these five women because each of them contributed something intellectually distinct and formative to Wages for Housework as a feminist political tradition.

Selma James was in her 40s and had been involved in revolutionary politics for decades by the time the feminist movement of the 1970s arrived. As a child in 1930s radical Jewish Brooklyn, she was politicized by men like her father, who organized labor unions, but also by the neighborhood women like her mother, who staged rent strikes, protested rising food prices, and struggled with the painful experience of having to foster out their children in times of financial strain. As the wife and comrade of C. L. R. James, she spent her 20s and 30s witnessing and participating in working-class and anticolonial struggles in the US, UK, and Caribbean, all with her young son Sam in tow. A working-class housewife and mother, a selftaught Marxist, and a charismatic, provocative orator, James insisted that housewives were the key to working-class struggle. While the left fixated on the white male factory worker, in the kitchens of the world were millions of unwaged workers, waiting to be organized.

“Let us remember,” wrote Mariarosa Dalla Costa, “that capital

xix

Introduction first made Fiat and THEN the canteen.” A meticulous scholar and committed militant, Mariarosa Dalla Costa was politicized in the crucible of radical student politics that swept Italy in the late 1960s. Growing up in rapidly industrializing postwar Italy, she saw a world in which human needs seemed to be subordinated to the demands of industry; a twisted logic in which the point of human life was to serve the interests of capitalism, rather than the other way around. As a young woman in a Catholic country, she encountered a patriarchal culture that pressed women of childbearing age into producing children, and then all but discarded them in old age, when their bodies no longer served that purpose. In the 1970s, as she and her feminist sisters, on the cusp of adulthood, confronted the incongruity between societal expectations and their own desires for free and meaningful lives, Dalla Costa saw clearly that women and their labors were at the very heart of capitalism. Their bodies gestated future workers. Their homes, where they worked in isolation cleaning and caring for workers and future workers, were not a refuge from the world of work, but extensions of the factory system. “And that,” she wrote, “is where our struggle begins.”5

To Silvia Federici, a philosophy PhD student living in Brooklyn, the myth that housework and caring were natural to women amounted to a violent distortion of the body and soul. Having grown up in Italy in the aftermath of fascism and its patriarchal cultural directives, she described the nuclear family as a prison, where people disciplined each other into rigid gender roles. In speeches and writings, she is relentlessly, methodically critical of the capitalist social order, yet she is also deeply idealistic, suggesting glimmers of other possible worlds. She provokes us to ask: what kinds of sensual pleasure and love, and community, would be possible were bodies and souls to be untethered from the nuclear family and the capitalist workweek? A lover of art and music and literature, she pondered a world in which creativity was a mass condition, and not just a privilege reserved for those who could buy themselves out of housework.

When asked by a journalist in 1987 to identify herself, Wilmette

Introduction

Brown told him: “I am a Black lesbian woman cancer survivor struggling for Wages for Housework for all women from all governments.”6 In Wages for Housework, Wilmette Brown saw more than a feminist demand: she saw a continuation of the Black freedom struggle. She radically expanded the concept of housework. In place of the housewife laboring in the heterosexual nuclear family home, in her writings and speeches we encounter Black women fighting off cockroaches in dilapidated public housing; women caring for those made sick by toxic waterways and polluted air; mothers struggling to protect their children from racism and police violence. To the insight that housework is the work that creates profit for capitalism, Wilmette Brown added: housework is the work thrust on us BY capitalism in the form of repair work for its harms. It is the work of survival.

“How dare they tell us that we’re scroungers or we’re beggars and that our life is worth nothing,” Margaret Prescod said to a group of Black women in Bristol in 1986. “We have helped to create practically everything that exists on this planet!”7 Prescod, who emigrated to Brooklyn from Barbados as a teenager, saw connections between the struggles of welfare mothers and her own experience as a West Indian immigrant, in a country that portrayed both as undeserving beneficiaries of American largesse. Prescod saw in Wages for Housework an intimate standpoint from which to comprehend the violent sweep of global history. The vast stores of wealth that made European and North American countries prosperous had been created through the unpaid work of women of color. When she and other immigrants came to New York and London and Paris and Amsterdam, they weren’t begging for charity: they were reclaiming what was rightfully theirs.

At the same time as my fascination with Wages for Housework grew, several founding members of the campaign were also thinking about their history and putting their papers and ephemera into archives. At first, my task seemed simple: I would visit these archives and, like an archaeologist assembling the scattered shards

Introduction

of an ancient vase, I would reconstitute the story of Wages for Housework. But I soon learned that telling the story of this movement would be more complicated than I had anticipated. There is pain and internal struggle in this history. Frequently, while speaking to former members of the campaign, I would blindly stumble into arguments I did not know existed. I would mention a name and be met with a facial expression making it clear to me that a former comrade was now a sworn enemy. I would sometimes be grilled about my loyalties even as I was trying to figure out what the grievances were about. At times, it seemed as though the archives themselves were assembled, curated, and organized for the sole purpose of settling scores.

The recollections of different members of the campaign are shaped, in part, by where they stand in relation to it now. For Silvia Federici and Mariarosa Dalla Costa, though they carry on the work of Wages for Housework in their activism and writing, the campaign itself is nevertheless in their past, and they have some critical distance from it. For Selma James and Margaret Prescod, the campaign never ended. The archive (and, they hope, this book) is an instrument of their ongoing movement, now updated into a demand for Care Income Now!

Wilmette Brown is a different story. She left the campaign in 1995. Her essays are long out of print and, unlike the others from the early days of the campaign, she no longer publicly identifies herself with Wages for Housework. At the time that I am writing this book, she has not republished her work nor documented her years of activism in an archive. To me, it is clear that she is a singular intellect, creator of some of the foundational ideas of this feminist tradition. She has acknowledged, but neither endorsed nor objected to, my writing about her work, nor has she tried to shape or influence what I write.

The main disagreement about the history of Wages for Housework is this: Prescod and James (and, to an extent, Brown) have publicly stated that, in the late 1970s, there was a split in the movement based on race. Dalla Costa (and others, who don’t wish to

be named) deny this, and say that the split was over questions of leadership and control – that James had a top-down vision about how the movement would operate, and that this drove people away. This book might provide context for these competing accounts, but cannot resolve them.

The internal struggles could have taken over and become the subject of this book, if I let them. I decided not to. In these pages, I try to sit with the messiness, exploring the disagreements that have political stakes, providing clarification when evidence allows, and, at times, letting contradictory accounts exist side by side.

“To be a member of our movement, there is only one requirement: you have to want Wages for Housework for yourself,” Selma James told me one day in early 2022 over Zoom. She was ninety-two years old at the time. Her white hair was pulled tight into a twist behind her head, and she looked small, birdlike in her chair. She leaned forward and pointed her finger at me: “Do you?”

I was caught off guard.

Until that moment, I had embraced Wages for Housework mostly as a thought experiment. Immersed in the archives, I thrilled to the promise of an unseen future catalyzed by the demand. But now, James’ question put me in mind of what I might have to give up. Like many of my generation, and those before me, I have tried to definitively sever the link between my gender and my suitability for housework. How would identifying with housework change my sense of self, and how would it change my status in the world? To some extent, has my own sense of accomplishment relied on my ability to escape this kind of labor when I’ve wanted to? And what about my children: do I want to understand the time I spend with them as “work,” and must I accept the premise that what I am raising them for is capitalism? (And can I deny it, without playing into the very ideology that exploits my unpaid labor?) Perhaps the part that makes me most uneasy is the centrality of productivity in their vision. Wages for Housework reveals how women’s work creates economic value in a capitalist system, and, in that sense, they

Introduction

make a brilliant case for wealth redistribution on capitalism’s own terms. But should we accept those terms? Do we have to be deemed “productive” to claim a share of the collective wealth?

I still don’t have an answer to James’ question. Thinking it through forces me to confront my personal investments in the very systems that I call unjust. Against my tendency to dwell in the abstract and idealistic, she calls on me to stay grounded in the materiality of housework and money as a place from which to envision a radically new world. This book is an invitation for you to do the same, wherever you are, whatever your relationship to housework.

Selma James

Selma James speaking in 1970 at the National Women’s Liberation Movement Conference at Oxford’s Ruskin College.

In 1969, Selma James appeared in a documentary called Women Talking. The film was an attempt to capture the zeitgeist of the emerging Women’s Liberation Movement, and the format was simple: a number of well-known American feminists, including Kate Millett and Betty Friedan, were filmed sitting casually and speaking about their feminist visions. The film was shot in black and white, and the camera panned over the women’s faces as they talked and smoked at a leisurely pace, musing on their experiences of womanhood. The topics ranged from girlhood experiences of Catholic schooling, to sexual assault, to gay rights, to the Miss Alaska pageant, to repressed sexual desire.

Wages for Housework

For the final ten minutes of the film, the floor is given to Selma James, who sits at the front of a room of well-coiffed audience members. She speaks quickly, as though her words cannot keep up with the speed of her thoughts. “We have to expand the conception of what a revolution is,” she says. “We have to expand the conception of what socialism is. And we have to make ourselves into human beings who can totally participate in society. We are not going to be forced into the roles that the family lays out for us.” As she speaks, her whole upper body is animated. Her dark hair is cut very short, accentuating dramatic facial expressions: she raises her eyebrows and tilts her chin as she poses a rhetorical question, and narrows her eyes when describing something unjust. She is colloquial, throwing in a “goddamn!” or “eh?!” for emphasis. Her pace quickens as she zeroes in on a point, and then slows for dramatic effect. She is making a joke one minute, and the next minute matter-of-factly promising the complete destruction of the capitalist social order.

Watching the film, you get a glimpse of her method. With her eyes and body and words, she surveys the room as though attempting to pull everyone in, trying to understand how each person might relate to the question of women’s liberation. You get the impression of someone who is ardently interested in people. She speaks sympathetically about the hypothetical woman who might be on the fence about feminism: say, a young wife who adores her man and who might balk at any movement that seems to belittle or mock that relationship. James stays grounded in the practical challenges that must be overcome in building a movement: how do you go to a political meeting in the evening, if you are the one who is expected to make dinner and look after the children? And what happens after the argument you and your husband have about it? What little everyday rebellions are required on the way to a revolution? At one point, she asserts: a sensible man would not feel threatened by women’s liberation. To emphasize her point, she does an impression of a “sensible man” responding to the Women’s Liberation Movement: “You mean that I have been involved in the oppression?!?!” She widens her eyes in mock disbelief, puts her hand to

Selma James her temple, pinching her brow, as though wincing in pain at the discovery. “Good Lord! I have to really begin to rethink everything . . . If they want to have a meeting by themselves, I am the first to defend them because I have been involved in keeping their mouths shut!” That, she explains to the audience, is how a sensible man acts.

Shortly after making the film, James described the experience in a letter to her old comrade, Marty Glaberman. “I met Kate Millett when she was here,” she wrote. “She told me that American workingclass women were ‘very reactionary.’ So we didn’t have much to say to each other. She didn’t know she was speaking about me.”1 James and Glaberman had been friends since the early 1950s, when they had both been members of a small splinter group within the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. While, in the film, James seems barely able to contain her excitement about the growing feminist movement, her letter to Glaberman reveals another layer: Selma James did not see feminism as separate from the struggle of working-class people against capitalism, but as a radical expansion of it.

The film ends with James speaking these words: “We are going to start with the actual lives that people live. And anything that doesn’t deal with that is outside the scope of the politics that we are trying to build.” The room breaks into applause, and her face relaxes into a warm, wide grin.2

Selma James was raised on the class struggle. She was born as Selma Deitch in 1930 in Ocean Hill–Brownsville, a working-class immigrant Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn. Her father was a Jewish immigrant from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the region now known as Ukraine. Her mother was “five foot nothing”3 and tough, had worked in a paper-box factory as a teenager, but had left waged work to raise three daughters, Edith, Celia, and Selma. They lived in a small house divided into four small apartments, with two families on each floor. James’ mother was active in the neighborhood: James remembers her helping her neighbors defy their eviction notices by breaking the locks on the doors and dragging furniture back into the apartments. She organized housewives in the neighborhood to

Wages for Housework

demand their “home relief”: small government payments of goods and money distributed to families during the Great Depression. Her father, who drove trucks for a living, organized a branch of the Teamsters Union. As a child, James witnessed him beaten up, arrested, and carted off for a short stint in jail in the course of battling both the bosses and the mafiosi who tried to control the union.4 Class struggle was not an abstract concept to Selma James.

For the people whom Selma James grew up with, there was no question of whether or not you were a socialist: the question was what kind of socialist. Both her parents were Communist Party sympathizers. “My father didn’t know how to write,” James recalled, “but he taught himself to read the Daily Worker,” the newspaper published by the American Communist Party.5 On Pitkin Avenue, the main drag through the center of Ocean Hill–Brownsville, the flyers of various organizations called passersby to action for various political causes – tenants organizing to protest evictions by landlords, mothers getting together to demand “home relief,” or the Socialist Workers Party Youth Wing recruiting new members to their meetings. Stalinists and Trotskyists congregated on stoops and street corners to debate what was happening in Moscow. Among her neighbors were men and women whose fierce idealism led them to drop everything and go to Spain to fight alongside the Popular Front in the Spanish Civil War. “I remember being on my father’s shoulders when the parade went by of nurses for Spain, and we all threw money into this big red banner that they held on the four corners.”6 As a child, James scoured the neighborhood with other children to collect tin foil from the insides of cigarette packets to make what she and the other children were told were bullets to fight Franco. Selma James grew up in a world where planning your life around the cause of revolution was not an unusual thing to do. Though they lacked formal education, the adults in Selma James’ world studied and debated politics and history with passion and urgency. Communist newspapers like the Daily Worker and the Yiddish language Morgen Freiheit gave working-class people direct access to world events. When they read about the struggles of