Programme Notes

Yuja Wang plays Ligeti

Thu 30 October 2025 • 20.15 Fri 31 October 2025 • 14.15

Thu 30 October 2025 • 20.15 Fri 31 October 2025 • 14.15

conductor Robin Ticciati

piano Yuja Wang

Joseph Haydn (732-1809)

The Representation of Chaos. Prelude to The Creation (1796–98)

György Ligeti (1923-2006)

Piano Concerto (1980–88)

• Vivace molto ritmico e preciso

• Lento e deserto

• Vivace cantabile

• Allegro risoluto

• Presto luminoso

intermission

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5 (1901–02)

I. Abteilung

• Trauermarsch. Im gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt.

• Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz

II. Abteilung

• Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell

III. Abteilung

• Adagietto. Sehr langsam

• Rondo-Finale. Allegro – Allegro giocoso. Frisch

concert ends at around 22.45

Most recent performances by our orchestra:

Haydn Chaos: Dec 2022, conductor Jan Willem de Vriend

Ligeti Piano Concerto: first performance by our orchestra

Mahler Symphony No. 5: Feb 2020, conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin

One hour before the start of the concert, Alexander Klapwijk will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Cover: Photo Stepan Kulyk (Unsplash)

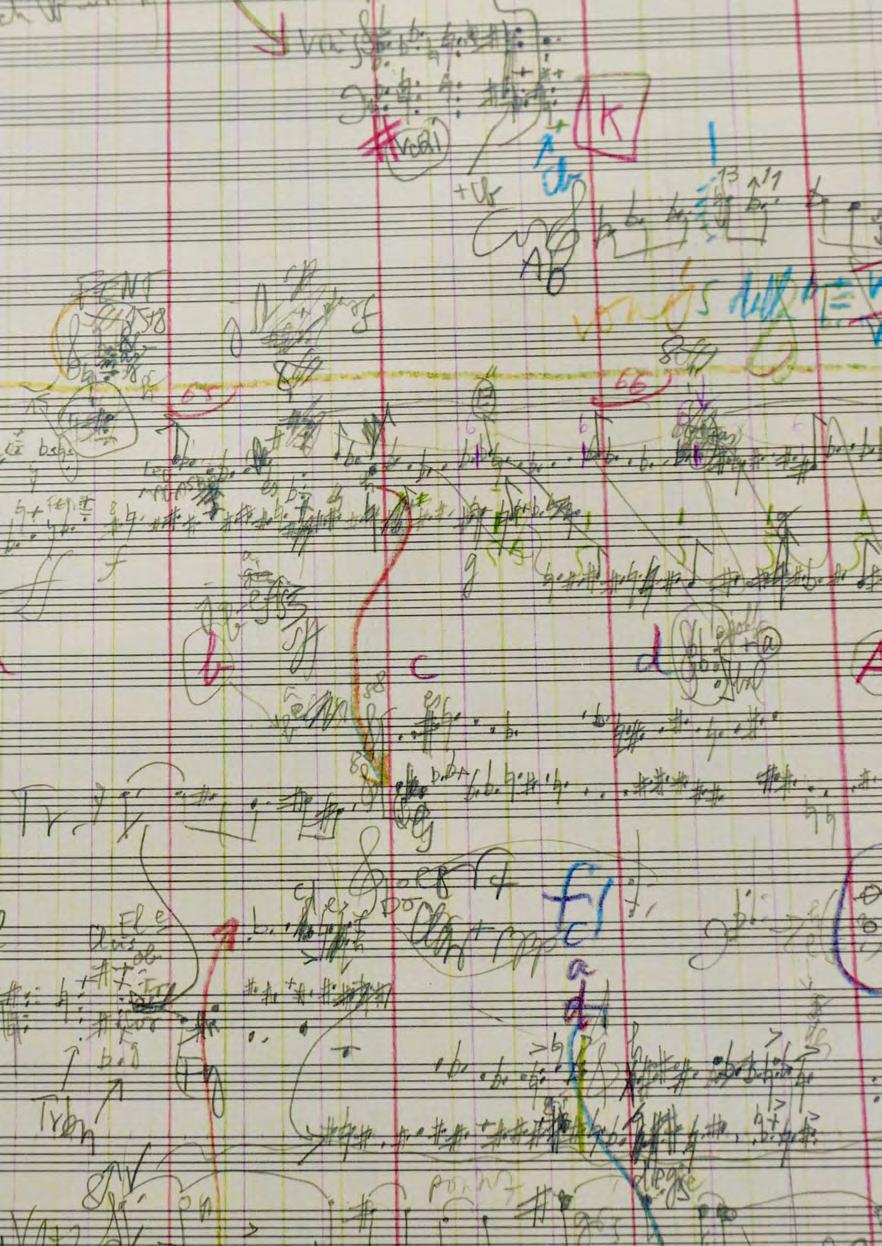

Movement III – Vivace cantabile (bar 64 through 66): fragment from Ligeti’s manuscript of the Piano Concerto.

Lithographical facsimile edition by B. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz 1991

A composer who has fully mastered the language of music can cause chaos. Haydn did so by breaking the rules. Ligeti created the illusion of chaos by combining rhythms of various tempi. Mahler was such a master of music that he was able to declare his love for Alma without words.

Following the death of his employer, Prins Nicolaus Esterházy, the 58-year-old Haydn was finally free to spend a year in London, where he was welcomed as a celebrity. Before long he was moving within royal circles. But the greatest impression made on him was a memorial to Handel in Westminster Abbey, at which a thousand-strong choir and orchestra performed Handel’s Messiah. Haydn was so moved that he decided to compose an oratorio of his own. Having returned to Vienna, he received mail from London. It contained a libretto reputed to have been written for Handel himself: The Creation. It was an ideal subject for a great oratorio. A little over a year and a half after having committed his first ideas to paper, Haydn premiered the work in Vienna. Up to the date of the premiere, the composer had held back one particular page of his score. The astonishing major chord that accompanied the text ‘And there was light’ had the desired effect: the audience was so dumbstruck that it took several minutes before the musicians could resume playing. In the preceding five minutes, Haydn had intentionally created chaos. One hundred and forty years before a Belgian physicist had formulated the ‘big bang’ theory, the composer had depicted the creation of his

universe from a ‘big bang’. Haydn combined the ingredients of his primordial soup: musical phrases of unequal length mixed with the abrasive harmonies and disjointed melodies from the woodwind section, like strands of vermicelli.

Haydn’s chaotic darkness is the prelude to Ligeti’s swirling Piano Concerto. The apparently chaotic rhythms of rapid notes contrasted with the impassive lines of the woodwind section reveals – when you dive beneath the surface – a carefully constructed whole of shifting accents and the nudging of different rhythms against each other. Although in the first movement all musicians play four beats to the bar, for some of them the beat is subdivided into three, for others two. The listener hears two parallel rhythmic lines, each with its own tempo. It’s almost impossible, however, to follow the individual rhythmic patterns of these two lines for long, and most ears will focus on the bigger picture. And this is precisely the trademark of the music of this Hungarian composer: small details bound up within a greater whole, in the way that the birds in works by graphic artist Escher together form a pattern.

If the first movement sounds overcrowded, the second movement – marked ‘slow and desolate’ – emphasises emptiness. Ligeti sows confusion by scoring the piccolo in a low register, whilst having the bassoon reach for the highest notes on the instrument, as if each were encroaching into each other’s path. We hear several unusual instruments: the lotus flute, an ocarina, a siren, and a police whistle. In the third movement the rhythmic character is accentuated by Cuban bongo drums. In the fourth movement the piano returns to its traditional role as the orchestra’s interlocutor; phrases played by the piano are responded to by various orchestral instruments. Ligeti compares these elements to the beads in a kaleidoscope, which create a continually changing pattern when rotated. Finally, in the last movement, all these rhythmic fragments tumble over each other once more. As Ligeti explains: ‘At first it sounds chaotic, but by listening to it a few times it becomes easy to understand: many independent, but similar, figures continually intersect’. However, understanding is unnecessary; this spectacular whirlwind of a piece is simply to be experienced.

When, during the summer of 1901, Mahler began work on his Fifth Symphony in the hut in the woods he used for composing, he finally sensed that he no longer needed words to communicate his ideas. By referencing, for example, a military fanfare or the sound of cowbells, his music spoke for itself.

The symphony begins with a sombre funeral march, one of Mahler’s favourite musical forms. The march is interrupted by emotional, almost hysterical outbursts of sound. In the second movement, the emotional rage continues - punctuated here

and there with small reminders of the funeral march – until, around ten minutes into the movement, a majestic melody is developed in the brass section. This breakthrough, however, is short-lived; a restless torment returns. Paradise appears unattainable for now. For that, the listener must wait for the final movement, completed by Mahler the following summer. Why another year? What had happened during the intervening winter?

Paradise

appears unattainable for now; for that, the listener must wait for the final movement

In November 1901 Mahler met the musically gifted Alma Schindler and fell madly in love with her. To his great good luck, the love proved to be mutual, and the pair were soon married. And there was no better way for the composer to declare his love for Alma than through music. The Adagietto, the fourth movement of the symphony, is the very love letter that Mahler and his wife would affirm to conductor Willem Mengelberg. To make clear the intent to his beloved without words, Mahler included a reference to music by Wagner – the motif by which Tristan and Isolde gaze lovingly at each other. Alma, who assisted her husband by transcribing the symphony’s score into a clean copy, must have recognised the motif. In the last movement of the symphony, the happiness of the newlyweds spills over from the notes. The optimism dashed in the second movement revives and is unstoppable in the final movement.

Carine Alders

Born: London, England

Current position: Music Director

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Honorary Member Chamber Orchestra of Europe

Education: violin, piano and percussion lessons, conducting studies from age 15, mentored by Sir Colin Davis and Sir Simon Rattle

Awards: Arthur Belgin Medal 2002, BorlettiBuitoni Scholarship 2005

Breakthrough: 2005, substituting for Riccardo Muti in the Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Subsequently: guest appearances with Wiener Philharmoniker, Berliner Philharmoniker, London Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; principal conductor Scottish Chamber Orchestra (2009–18), Music Director Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (2017–24) Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2008

Born: Beijing, China

Education: Conservatory of Beijing; Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia with Gary Graffman

Awards: Musical America’s Artist of the Year 2017

Breakthrough: 2007 with Tchaikovsky’s Piano

Concerto No. 1, substituting for Martha Argerich with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Charles Dutoit

Solo-appearances with: the major orchestras of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Washington, New York, Staatskapelle Dresden, Berliner Philharmoniker, Münchner Philharmoniker, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Artist in Residence: Carnegie Hall New York, Wiener Konzerthaus, Philharmonie Luxemburg; Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra in the 2021/22 season

Chamber music: with Gautier Capuçon (cello) and Andreas Ottensamer (clarinet)

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2018

Harry Potter in Concert, part 1

Wed 12 November 2025 • 19.30

Thu 13 November 2025 • 19.30

Fri 14 November 2025 • 19.30

Sat 15 November 2025 • 19.30

Sun 16 November 2025 • 13.30

conductor Justin Freer

Williams Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Fri 21 November 2025 • 20.15

Sun 23 November 2025 • 14.15

conductor Bas Wiegers

piano Kirill Gerstein

Ivičević Black Moon Lilith

Adès Piano Concerto Stravinsky Petrushka

Thu 27 November 2025 • 20.15

conductor Lahav Shani

piano Martha Argerich

Wagenaar Ouverture Cyrano de Bergerac

Schumann Piano Concerto

Brahms Symphony No. 2

Fri 28 November 2025 • 20.15

conductor Lahav Shani

violin Patricia Kopatchinskaja

Sjostakovitsj Violin Concerto No. 1

Brahms Symphony No. 3 ‘Eroica’

Proms: Nutcracker & Company

Sat 13 December 2025 • 20.30

conductor Aziz Shokhakimov

violin Maria Milstein

Glinka Overture Ruslan and Ludmilla

Tchaikovsky The Nutcracker: Suite Tchaikovsky Serenade mélancolique

Khachaturian Masquerade: Suite

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest

Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, Concert Master

Vlad Stanculeasa,

Concert Master

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Gustaw Bafeltowski

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Paul Stavridis

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/

Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Martijn van Rijswijk

Timpani/ Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp

Albane Baron