Authors:

Kendall Claus, Lead Author

Jesce Walz, Co-Author and Editor

Design:

Jacob Williams, Graphic Design

Project Leadership:

Leigh Christy, Project Director

Kimberly Seigel, Project Advisor

External Reviewers:

Chris Magwood, RMI

Jacob Deva Racusin, New Frameworks

James Kitchen, MASS Group / Bio-Based Materials Collective (BBMC) Leila Behjat, Parsons Healthy Materials Lab / The New School

Internal Reviewers:

Asif Din, Danielle Baez, Glenn Veigas, Helena Christensen, Juan Rovalo, Lona Rerick, Mady Gulon, Yash Akhouri

About Perkins&Will

Innovation starts with inquiry. In our never-ending quest for knowledge, we push limits, take risks, investigate, and discover. Perkins&Will, an interdisciplinary, research-based architecture and design firm, was founded in 1935 on the belief that design has the power to transform lives. Our research is inspired by our practice, and our practice is informed by our research.

We believe that research holds the key to greater project performance. Our researchers and designers work in partnership from project start to completion. We constantly ask ourselves, “What if?” “What’s next?” This makes our ideas clearer, our designs smarter, our teams happier, and allows us to innovate to achieve our clients' goals and further best practices in design.

www.perkinswill.com

This document relates to the following publications, which can be found at:

Bio-Based & Natural Materials: Context, Applications, and State of the Industry - Executive Summary

Bio-Based & Natural Materials: Context and Applications in Architecture

These and related documents can be found on our website

This report provides an overview of the current state of the bio-based and natural materials industry, drawing on literature review and market research to assess how these materials and products are evolving. It identifies key opportunities that signal growing momentum, such as growing policy support, demand for low-carbon and healthier alternatives, demonstration projects, and expanding supply chains. It also explores systemic barriers, including fragmented standards, limited testing and certification pathways, and the need for expanded infrastructure and investment. While available products and market interest are increasing, the standardization and specification of bio-based materials in practice are not yet keeping pace, creating both tension and opportunity. By mapping product maturity through a Technology Readiness Level framework and assessing opportunities and barriers across the value chain, this report provides directional insights to help practitioners, manufacturers, and partners understand emerging trends and strategically support the transition toward more regenerative material economies.

Across the U.S. and internationally, demonstration projects are proving that bio-based materials can meet performance demands, reduce carbon, and improve occupant health. While precise market data for bio-based building materials remain fragmented, evidence suggests a rising trajectory. Bio-based products such as timber, cork, hemp, and clay are increasingly present in fit-outs, residential construction, and pilot commercial projects. Growth is supported by policy incentives, environmental disclosure requirements, and consumer preference for low-carbon, healthier materials.

While bio-based materials have gained traction, they remain outliers, representing a small fraction of overall material inputs. Research suggests that realized projects have not resulted in a significant increase in bio-based development, even when they’re delivered on time, within budget, and with strong environmental outcomes (Logan 2024). A combination of cultural inertia, systemic barriers, and fragmented supply chains continues to slow widespread adoption, even as climate urgency accelerates (International Living Future Institute (ILFI) and Grable 2023, 15,19)

This State-of-the-Industry-Survey includes the following content:

Research, Innovation & Technology

Localized Manufacturing

Circular Bio-Economies

Climate Policy, Certification, & Incentives

Product Transparency

Market Growth

Digital Libraries & Platforms

Consumer Demand

Aging Building Stock

Cross-sector Collaboration

Performance Benefits

Demonstration Projects

Perception, Knowledge and Design Culture Codes, Policy & Regulatory Misalignment

Fragmented Supply Chains

Financial Structures

Industry Conservatism

Data Gaps

Momentum vs. Inertia

Carbon, Sourcing, and Biodiversity

Operationalize the Industry

Together, these patterns signal an industry in transition.

This state of the industry review emerged from a research sprint to better understand the landscape of bio-based materials, including their availability, benefits, barriers, and regenerative potential. We spoke with designers, researchers, manufacturers, and ecologists. We reviewed case studies, industry collaborations, academic reports, and product literature to inform our analysis. What follows is a synthesis of the insights that surfaced across this work, providing directional signals for where the industry is heading and where the design industry can engage.

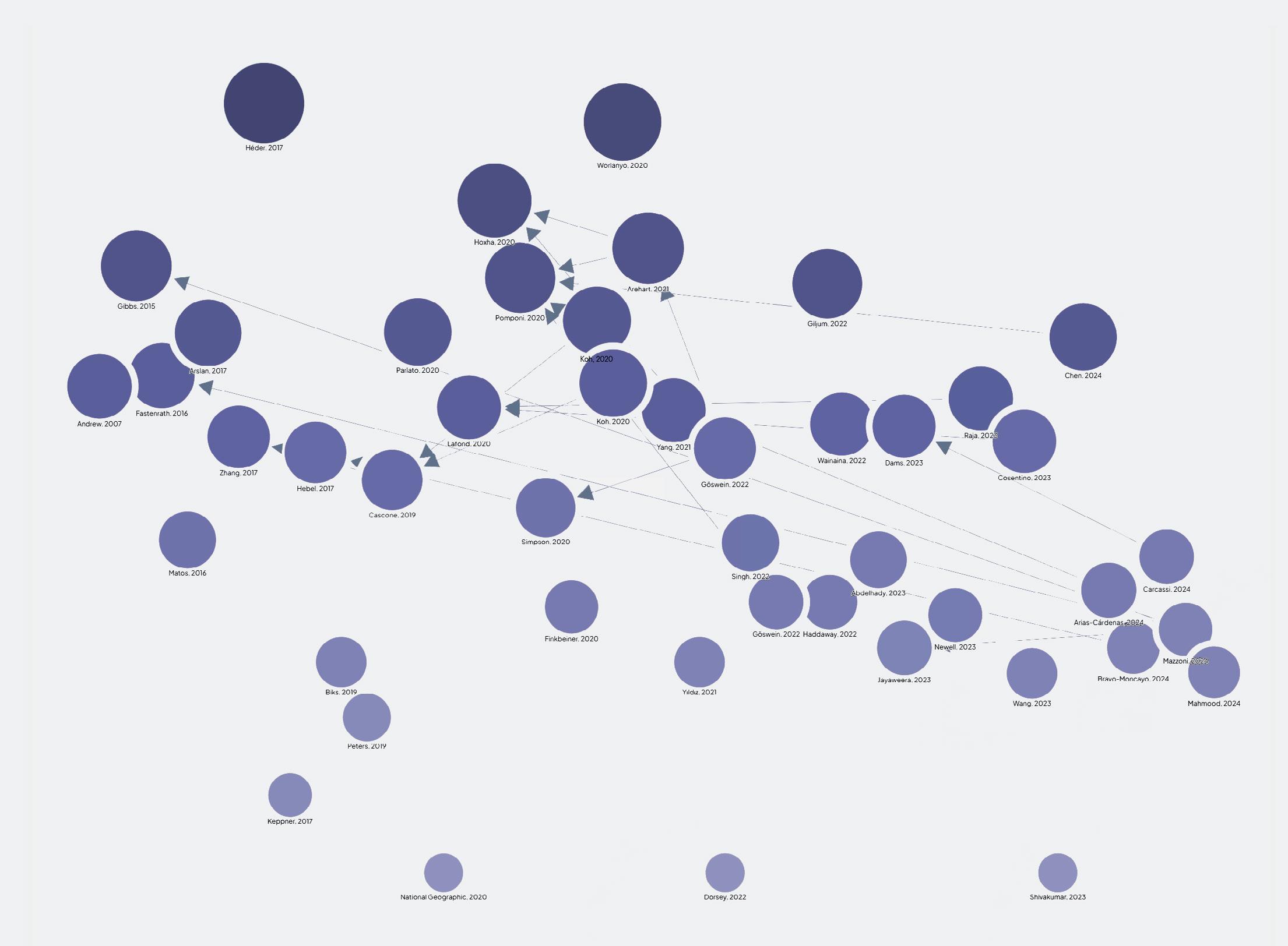

The literature referenced in this synthesis draws from over 100 references published between 2014 and 2025. These include academic, trade, and grey literature. While this review is extensive, it is not intended to represent a comprehensive literature review. Figure 1 depicts connections between the literature referenced in this report and additional references. The sources in green are referenced in this report. The sources in blue represent potential for future exploration.

Our Bio-Based & Natural Materials: Context and Applications in Architecture report outlines a taxonomy of nine types of bio-based and natural materials, exploring the breadth and characteristics of each material category (Claus, Walz. 2026). These include:

- Animal

- Bacteria

- Fungi

- Marine

- Plant

- Mineral

- Earth

- Biocomposite

- Living materials

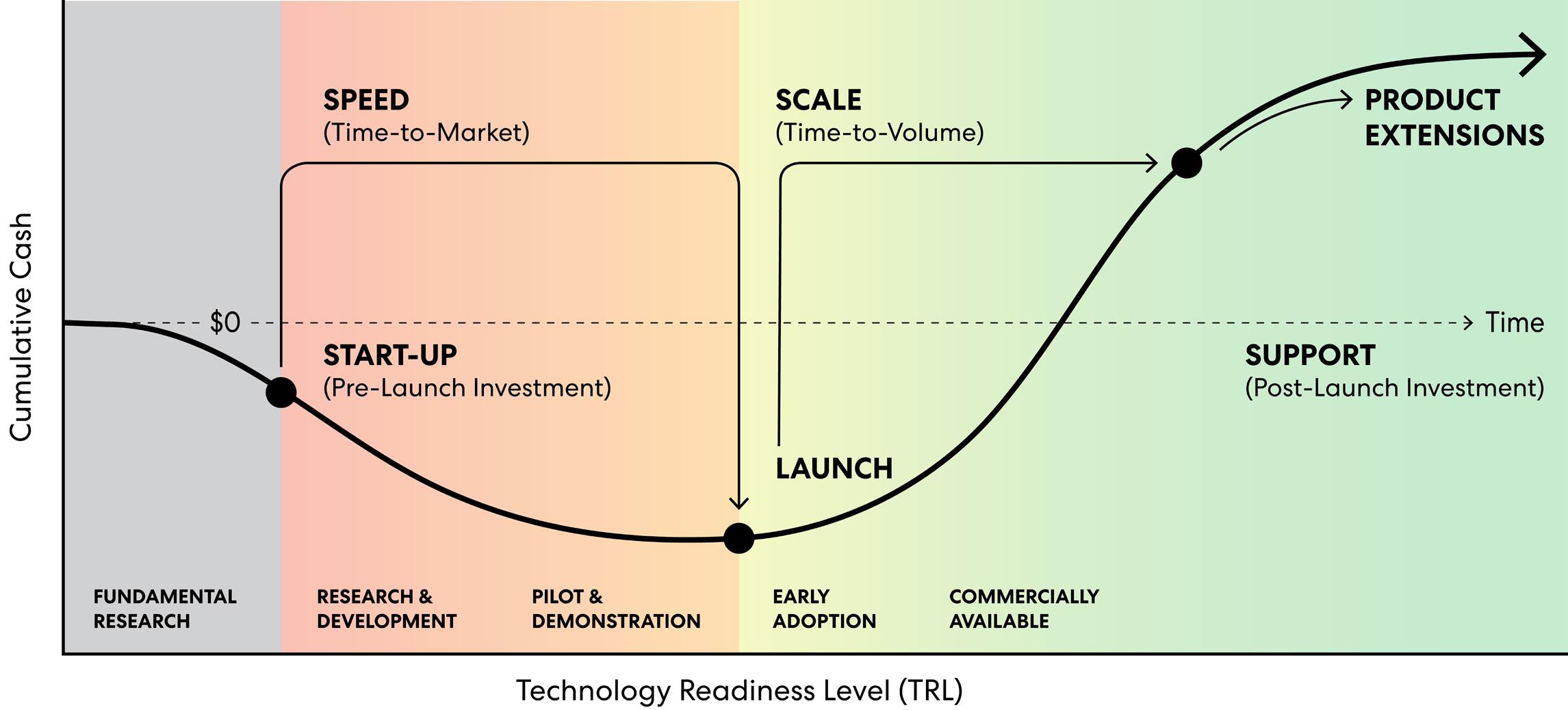

Following an overview of each category, the report applies a consistent methodology to evaluate the maturity, availability, and near-term applicability of bio-based and natural products using a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) framework, which is included in the following pages of this report as a reference.

By pairing material characteristics with real-world readiness, we translate a diverse and rapidly evolving field into practical guidance for designers. The insights that follow highlight where momentum already exists (materials that are ready to be incorporated into commercial work) as well as emerging early-adoption products that warrant pilot testing. Together, these observations provide a bridge from understanding material possibilities to identifying actionable opportunities for responsible specification.

Industry readiness to adopt bio-based materials and products spans a broad spectrum. Some are ready to integrate now; many are emerging. The following tables translate the broad material landscape into two practical pathways for designers: commercially available materials and early adoption materials.

Commercially available materials represent products with higher TRLs (those already in commercial use, supported by established supply chains, testing data, and predictable performance in U.S. project contexts). These are the “specifiable today” options that can be deployed with minimal risk or additional approval processes.

Early Adoption materials, by contrast, occupy an important middle ground in the innovation curve. These products demonstrate clear potential and are increasingly available, but may require piloting, additional coordination with manufacturers, or careful review of performance. They are promising options for teams seeking to expand their materials palette while supporting market maturation.

Together, these two categories illustrate where designers can take confident action now and where thoughtful experimentation can accelerate the transition toward a more ecological and resilient materials economy. They also provide a common language for discussing readiness, risk, and opportunity across project teams, clients, and partners.

As interest in bio-based materials grows, so does the need for reliable, accessible tools to support product discovery and evaluation. To identify bio-based and natural materials that are most relevant for near-term application, we adopt a simplified Technology Readiness Level (TRL) framework from Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) Canada (Table 3) (ISED Canada 2021).

DEVELOPMENT

Commercially Available -- Technology development is complete

Early Adoption 9

9

Actual technology proven through successful deployment in an operational environment

nj Products available from multiple suppliers

nj Supply chains established to at least a regional scale

nj Has been applied in built projects and demonstrated performance capacity

nj Some products explicitly accepted by codes and standards, with established testing data

nj Performance standards/certifications exist may be in development

nj Codes and insurance acceptance limited or dependent on equivalency pathways

nj Scaling potential demonstrated, but supply reliability is inconsistent

nj May be commercially available in select regions, in many cases outside of North America Pilot & Demonstration (6-8)

8

Research & Development (3-5)

Fundamental Research (1-2)

Actual technology completed and qualified through tests and demonstrations

7 Prototype system ready (form, fit and function) demonstrated in an appropriate operational environment

6 System and/or process prototype demonstrated in a simulated environment

5 Validation of semi-integrated component(s) in a simulated environment

4

Validation of component(s) in a laboratory environment

3 Experimental proof of concept

2 Technology and/or application concept formulated

1 Basic principles observed and reported

nj Tested in prototypes or demonstration projects

nj Some small-scale suppliers exist at the start-up level

nj Lacks certifications (fire, durability, toxicity) that would be required to expand use

nj Supply chains are fragmented, seasonal, or hyper-local

nj Limited or no suppliers for architectural applications

nj Tested in labs or conceptual applications

nj No consistent performance data or building code pathways

nj Requires controlled conditions (e.g., bioreactors, lab growth)

nj No formal suppliers for architectural applications

nj Academic explorations in literature

nj Basic research conducted; principles are defined

The readiness of bio-based materials varies across a wide spectrum, from commercially proven systems to early-stage innovations.

Commercially available products, including wool insulation, timber, bamboo, cork, clay, and hemplime (hempcrete), are commercially available and code-compliant in many settings. These materials perform competitively with conventional options, supported by growing supply chains and case studies across commercial, institutional, and residential projects.

Early adoption applications such as mycelium panels, seaweed insulation, and algae bricks are being piloted but have yet to achieve widespread adoption. Their potential is clear, but scalability and regulatory alignment remain barriers. Production occurs mainly at small or regional scales. Limited testing protocols and certification pathways continue to slow entry into mainstream construction (Wattanavichean et al. 2025).

Pilot / research-stage innovations, including microbial bio-cements, programmable coatings, and hybrid living materials, remain primarily within labs or controlled testing environments. These systems are often deployed in non-structural assemblies with lower regulatory risk. Current research, such as MIT’s lab-grown timber (Zewe 2022) and Keel Labs’ development of seaweedbased fibers (SynBioBeta 2024), illustrates the next frontier of material development: diversifying feedstocks, scaling biofabrication, and tailoring performance properties to specific architectural needs.

There is no single standard for TRLs. The concept was initially developed by NASA and has evolved to be used in different ways by different sectors. Critics note that customization reduces the integrity of the TRL scale (Héder 2017) and call for alignment within industry groups around standard definitions. Our decision to align with ISED Canada is a first step towards this, yet this represents a suggestion by select authors rather. An industry effort is needed to align around shared standard TRL definitions for bio-based and natural materials.

Bio-based and natural materials exist in a variety of formats, ranging from traditional purpose-built methods to mass-produced products. In this paper, we have retained the term commercially available, in order to retain alignment with the existing ISED Canada TRL framework. We use this term to describe materials and products whose technological development stage makes them ready and available for use in commercial building projects.

In this research, commercially available material types and products may be represented by just a few manufacturers in North America or may be more relevant in some regions and applications than others. However, each option marked commercially available in this report is available for implementation given the right project, context, and commitment from a team to source the material or product. Additionally, some products are readily available in Europe but not North America; these products are classified as early adoption in the context of this report.

Pilot one new material. Start with low-risk assemblies, like acoustic panels, wall finishes, or insulation, to gain real-world familiarity and share performance data.

Bio-based and natural materials include processes as well as products. Some bio-based and natural materials represent traditional or regional methods that are purpose built and may not involve new technology. For example, traditional methods such as thatch roofing, rammed earth, and natural stone masonry are less likely to manifest as a commercial product and instead require manual labor and knowledge of craft to ensure success. These materials and methods are classified as commercially available when they are readily accessible due to proven outcomes and capable builders. However, their availability may vary regionally due to climate, seismic suitability, or building codes. These materials are flagged with an asterisk (*) where they are included in our TRL tables.

These platforms and resources can serve as starting points for identifying and incorporating bio-based products into building projects.

• AIA Materials Pledge – a collective commitment by architects to prioritize building products that advance human health, climate and ecosystem health, social equity, and a circular economy.

• Aireal Materials – a physical and online library of materials that capture CO₂ during production.

• ACAN Natural Materials Detail Library – a collection of natural construction details and list of natural materials manufacturers, suppliers and installers.

• Biobased Materials Library – a library of all biobased materials used in the projects of Company New Heroes and Biobased Creations.

• Builders for Climate Action (BfCA) Bio-Based and Circular Materials Database – a curated database of bio-based and regenerative materials.

• Future Materials - showcases design-led, low carbon, bio and circular products.

• Materials Assemble Materials Library – a library of the finishes and techniques (including bio-based) from working craftsmen, artisans and makers.

• Materials District – a database and match-making platform that includes natural materials & connects manufacturers and distributors w/ A&D professionals.

• Material Order – a resource for designer materials collections led by academic and cultural institutions (filter results by “Lifecycle component > renewable”).

• Parson’s Healthy Materials Lab (HML) Healthy and Regenerative Materials Collection – a large material collection focused on materials and products that originate from ecological sources.

• USDA BioPreferred Catalog – a catalog of certified bio-based products (see “Construction” tab).

• UTSOA Materials Lab – a student researchdriven online database of existing, new and upcoming materials.

• Bio-Based & Natural Materials: Context, Applications, and State of the Industry - Executive Summary – distills information from this document as well as our “Context and Applications in Architecture” report.

• Bio-Based & Natural Materials: Context and Applications in Architecture – foundational guidance for integrating bio-based and natural materials into architectural practice.

• Circular Design Primer for Interiors – distills best practices in circular design from projects across our global practice; the strategies in this primer may be applied to architecture and interiors projects.

• Getting to Craft in Mass Timber – a guide to support ecological sourcing, design, and technical considerations for mass timber projects.

• Our Carbon Health Series – a series of reports developed in collaboration with Habitable that address both embodied carbon and health concerns that are associated with common building materials..

Several developments are accelerating the growth of bio-based materials and signaling a broader transformation across the building industry.

Research in bio-based building materials has grown by roughly 25% per year since 2014, reflecting the field’s accelerating relevance (Arias-Cárdenas et al. 2024). Universities and startups are developing scalable production systems, including vertical mycelium farming, bioreactor cultivation, precision agriculture, and AI-controlled growth chambers that optimize yields (Wattanavichean et al. 2025; Wainaina and Taherzadeh 2022). Microbial fabrication is opening new possibilities such as self-healing, carbonsequestering products (Singh et al. 2022; MSU Innovation Center 2023). These innovations are enabling prefabricated biocomposites with custom properties and free-form geometries, broadening architects’ design possibilities (Abdelhady et al. 2023).

“Today, 70% of all product innovations are attributed to new findings in materials science and a new generation of projects is emerging [through] new functionality made possible by materials research.”

― Peters and Drewes, 2019

Build local making capacity. Support smallscale fabrication hubs or partnerships with local universities to pilot material processing near sourcing regions.

Map your bioregional waste/residue streams. Collaborate with local farmers, recyclers, and manufacturers to identify organic by-products that can be diverted into building components.

Beyond the lab, parallel advances in digital fabrication, such as CNC milling and 3D printing, are enabling customized biocomposites with reliable performance. This contributes to a shift in how and where production happens. Emerging “maker districts” show how technology and localization can increase production of cultivated materials through distributed small-scale infrastructure. Community-based material production also supports resilience by reducing reliance on unpredictable supply chains (Hebel and Heisel 2017). Consumer demand for craftsmanship and sustainable products signals support for manufacturing and design that reconnects materiality to place-based regional economies (Novy 2022). Together, these developments point toward a material economy that is both technologically advanced and locally grounded.

Check it Out: Our Circular Design Primer details opportunities to maximize the value of materials throughout their life cycles.

Agricultural, industrial, and municipal waste streams can be transformed into valuable products that strengthen regional economies (Dataintelo 2025). RMI estimates that each year the U.S. produces 1.1 billion tons of underutilized biomass (crop and forest residues, grain, straw, and agricultural fiber), much of which decomposes or is burned. Instead, this biomass could be redirected into insulation, wall panels, and concrete additives. This would reduce methane, air, and water pollutants and provide economic opportunities for foresters and farmers (Magwood et al. 2025). Cities generate a further 1.3 billion tons of waste annually, nearly half of which is organic, representing additional potential to create value through nutrient recovery (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2017).

Importantly, bio-based products can continue to cycle into nutrients after end-oflife, so long as biological components are separable from technical components. Once separated, biological materials can be reused or used for feedstock, anaerobic digestion, energy, or compost (Figure 2) (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2021b).

Policy reform can be a catalyst for bio-based, low-carbon materials (Dams et al. 2023; Business View Magazine 2025).

In the U.S., the 2014 launch of a USDA-supported hemp pilot program, and subsequent 2018 Farm Bill, enabled hemp cultivation research and legal production and as of 2024 nine states now have “Buy Clean” procurement policies requiring low-carbon materials on public projects. In Canada, Vancouver and Toronto have implemented embodied carbon reduction requirements. These initiatives send strong market signals for climate-friendly products (Haramati and Hyne 2025). Building codes are also evolving. The 2021 IBC allows for mass timber towers up to 18 stories (Smith 2020; Showalter 2020), which dozens of jurisdictions across North America (as of 2021-2025) have embraced, reflecting broader acceptance of bio-based systems. The International Code Council (ICC) has also made incremental progress with appendices for straw bale and cob (Logan 2024), and new ISO standards for bamboo provide a precedent for other agricultural residues (Göswein et al. 2022).

Europe is further ahead than North America, having embedded bio-based construction into the European Green Deal, Circular Economy Action Plan, and building policies such as France’s RE2020 and Denmark’s BR18, which explicitly encourage low-carbon, bio-based materials (Magwood et al. 2023). The E.U.’s Bioeconomy Strategy aims to scale up bio-based products (European Commission 2018). These frameworks show that policy can make low-carbon alternatives preferred for climate reasons.

Emerging certifications are complementing these policy shifts by providing clear frameworks to verify carbon storage and regenerative value in construction materials. The Construction Stored Carbon (CSC) certification is one such initiative, recognizing projects and products that verifiably remove and store atmospheric carbon through biogenic materials. By linking carbon storage directly to building materials, CSC helps align design practice with climate accounting frameworks and provides a pathway for crediting stored carbon in both private and public projects. Together with reforms that tie financing and procurement to carbon accountability, along with expanding incentives and testing protocols, such frameworks reduce adoption risk and encourage mainstream climate-positive, biobased construction. (Singh 2025; International Living Future Institute (ILFI) and Grable 2023, 154)

Rising demand for carbon and health data poises bio-based materials to become leaders in disclosure (International Living Future Institute (ILFI) and Grable 2023). Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) are now prerequisites for both Buy Clean policies and many green building standards (e.g., LEED, LBC) (Shivkumar 2025; Pathways 2024).

While EPDs for bio-based products sometimes report stored carbon in different ways (Ellingboe et al. 2025), efforts to harmonize carbon accounting methods for bio-based materials have recently been established. For example, the ECHO project now encourages biogenic carbon to be counted separately from fossil carbon (Lewis et al. 2024; Picken et al. 2024) and strongly recommends that designers include supply chain traceability requirements for raw materials to ensure they can be traced to legal sources. In addition to reducing confusion, this approach results in the evaluation of stored carbon on its own merit, reducing controversial “carbon negative” claims (Figure 3). Simultaneously, organizations are working through coalitions like the Climate Smart Wood Group to improve forest management and sourcing transparency (Climate Smart Wood Group 2025). These steps are critical to recognize sequestration benefits and build confidence in performance analysis.

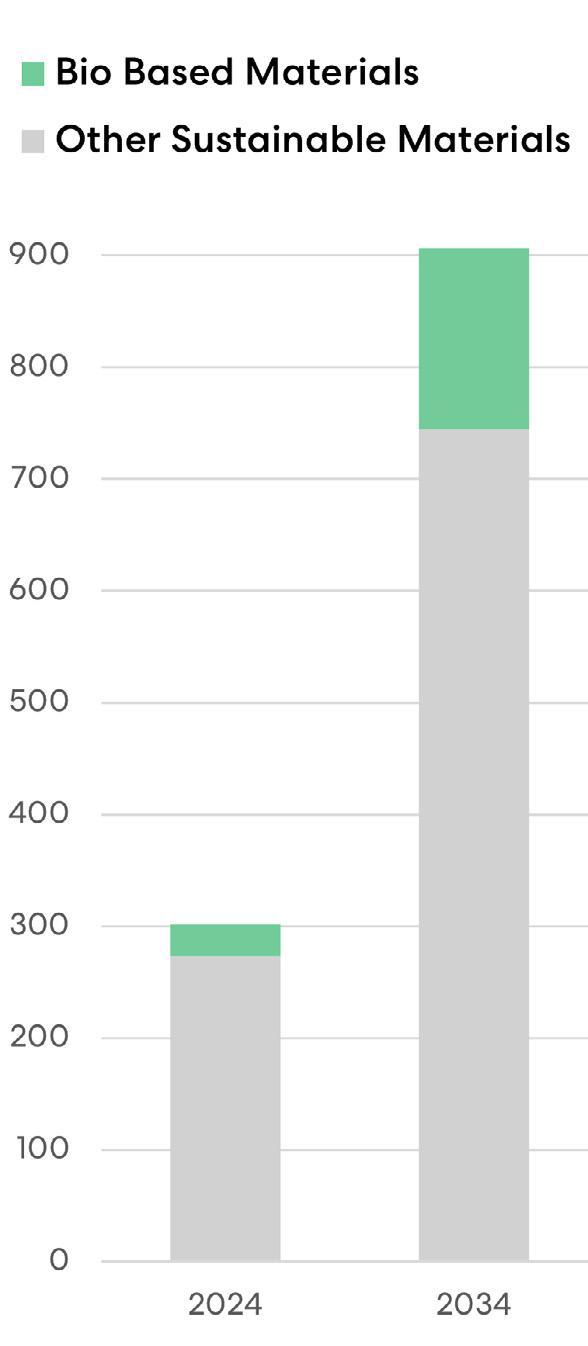

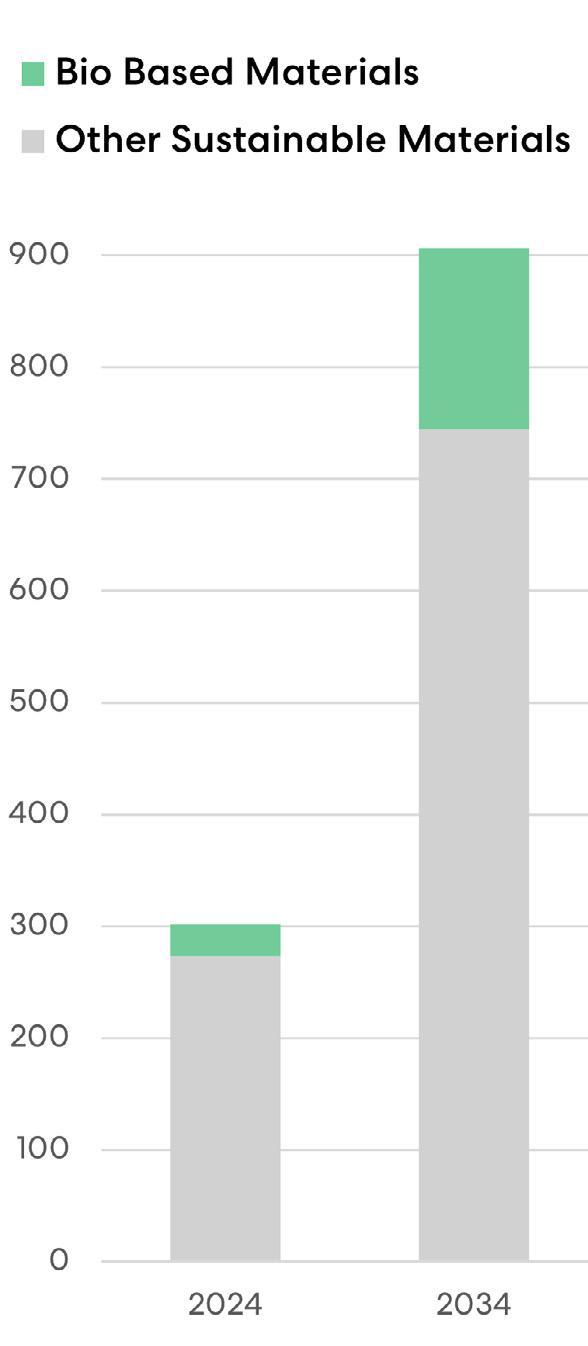

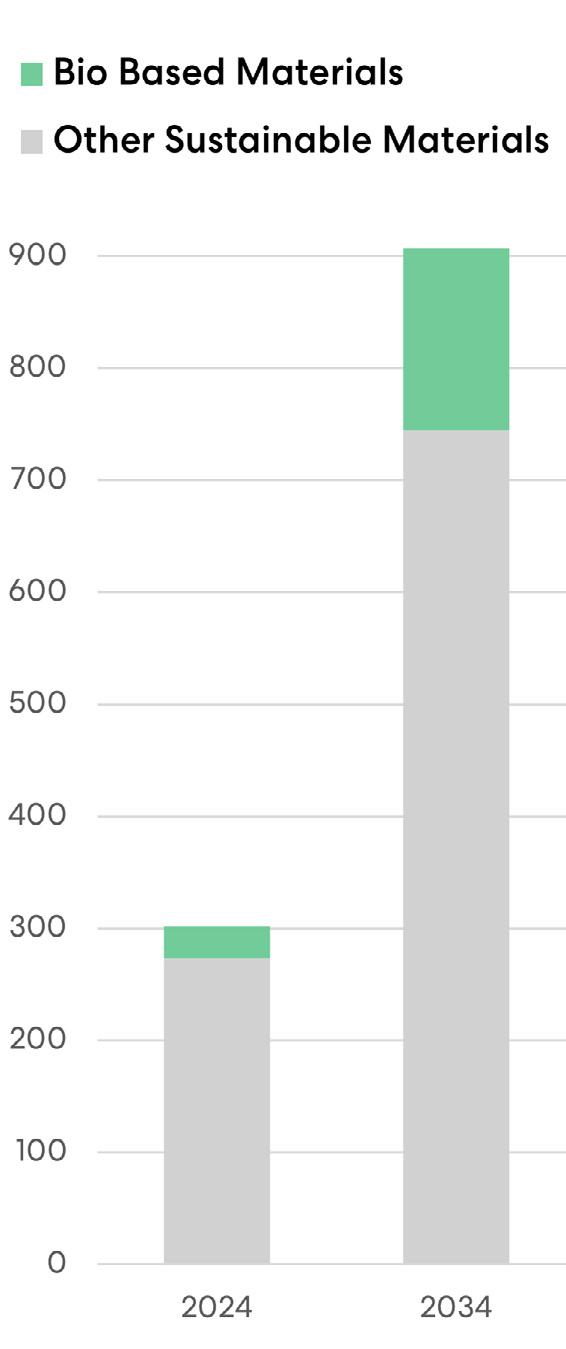

nj The global sustainable construction materials market is projected to triple in value , growing from US$301.6 billion in 2024 to US$907.1 billion by 2034. This indicates a robust shift toward sustainable products (Business View Magazine 2025).

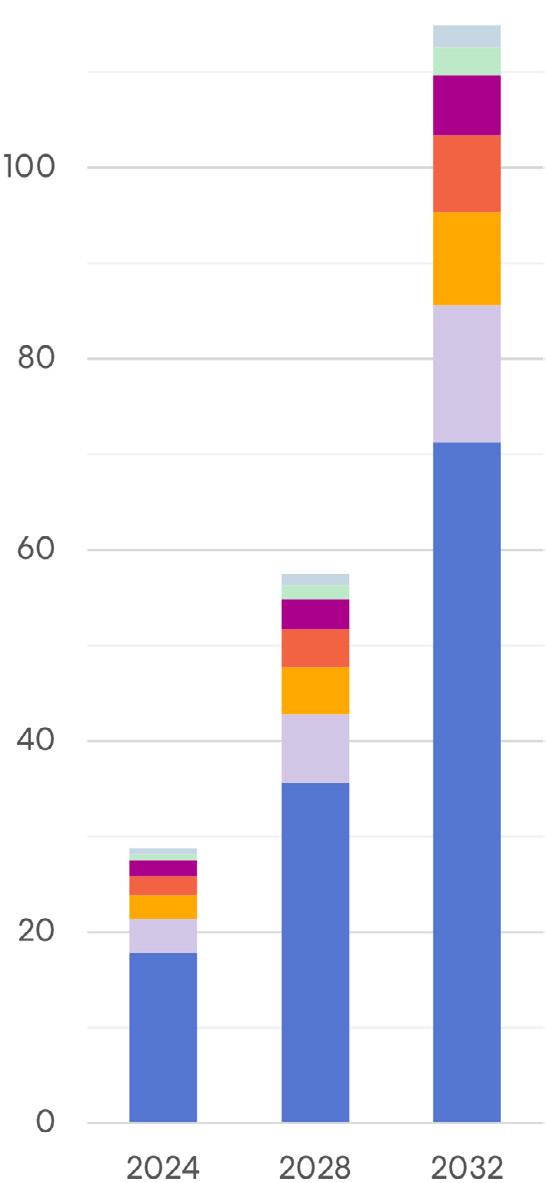

nj The U.S. bioeconomy currently accounts for ~5% of GDP and could grow to ~33% of global output, potentially $30 trillion annually globally (Manufacturing USA 2022). The global market for bio-based building materials is forecast to grow at an average of 18.9% annually between 2023 and 2032 (Global Market Insights 2024).

nj Bamboo construction is expected to grow from US$68.5 billion in 2024 to US$214 billion by 2034, reflecting demand for rapidgrowth, lowcarbon alternatives (Singh 2025).

nj Global CLT market projections show a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.4 %, with Europe currently dominating global market share. In North America, growth is being driven by hybrid timber-conventional constructions for innovative office designs (Fortune Business Insights 2025).

nj The hempcrete market was estimated at US$25.83 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach US$34.61 billion by 2030. This growth is accelerating and marked by moderate to high innovation, including techniques like pre-casting panels and developing hybrid composites (Grand View Research 2024).

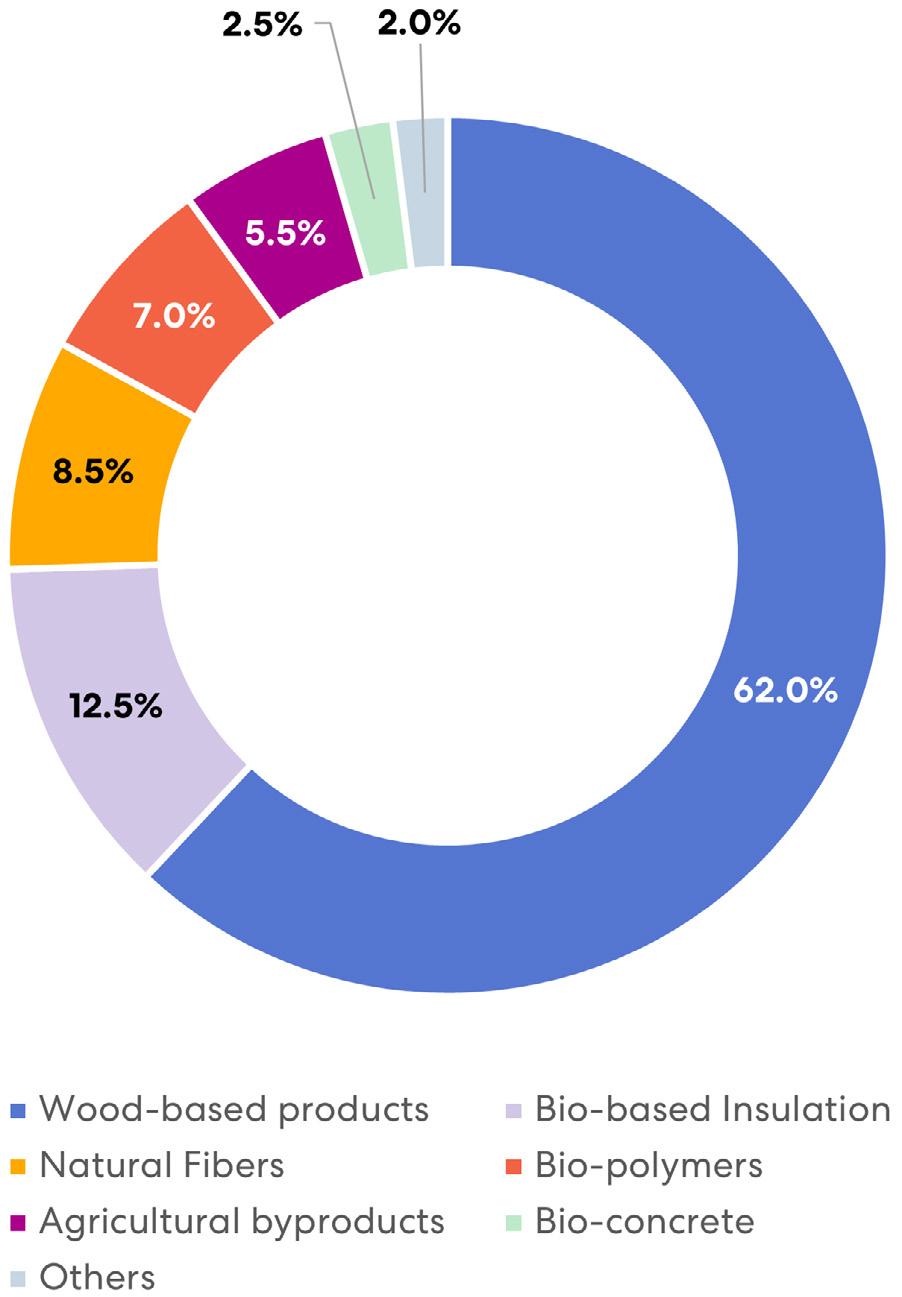

% of market value by material type (left); projected growth by material type (center); projected growth among sustainable materials (right)

Forecast average of 18.9% annual growth through 2032

Digital material libraries are evolving into catalysts for innovation in building design. When traditional repositories are integrated into digital workflows, they lower barriers to adoption and embed material data directly into design processes, which is especially valuable for bio-based products still navigating varying levels of technology readiness. Breaking into the construction market is difficult for new products given the costs of testing, certification, and scaling. Digital platforms help address this by offering visibility, credibility, early validation that supports discovery, and eventual market adoption. For practitioners, they also provide references, precedents, and real-world use cases that reduce risk and encourage experimentation. University labs such as Parsons Healthy Materials Lab and the University of Texas’ (School of Architecture Materials Lab) are curating physical and digital repositories of biobased samples, expanding access and connecting designers directly with manufacturers.

Looking ahead, the industry is moving toward a paradigm where “form follows material,” driven by resource scarcity, economic volatility, and the need for local, renewable feedstocks. Advances in digitalization and AI are expected to further transform material sourcing, enabling geobased selection and strengthening regional supply chains (Gattupalli 2024). See the Tools & Resources section for a full list of digital libraries/platforms.

Consumer demand is rapidly driving the uptake of sustainable and bio-based materials, with more than half of U.S. consumers now seeking environmentally and socially responsible products (Rogers et al. 2023). This “conscious consumerism” trend is mirrored in the building industry, where contractors and developers increasingly favor low-carbon, non-toxic, and responsibly sourced options (Business View Magazine 2025). This growing appetite, alongside the industry’s massive raw material use, is pushing suppliers to expand offerings and prompting a shift from cost-focused decisions toward evaluating longterm value, signaling stronger alignment between conscious consumerism and an industry-wide reassessment of material economics and lifecycle benefits (Gattupalli 2024).

The need to retrofit existing buildings represents a huge opportunity to incorporate and even normalize bio-based materials while reducing operational emissions. Up to 80% of all buildings that will be standing in 2030 will require some form of retrofit to improve efficiency, according to Project Regeneration. These renovation projects are prime candidates to swap bio-based products in place of conventional ones, as retrofits often involve replacing insulation, cladding, and finishes.

“Ultimately, it’s about knowledge sharing and fostering collaboration–by pushing each other, we can accelerate the adoption of a wider range of sustainable materials in our built environment.”

Kika Brockstedt, Revalu (Gattupalli 2024)17

By dramatically scaling up building retrofits, we have a chance to eliminate about 28% of global GHG emissions (Project Regeneration 2014). Each deep-energy renovation (better insulation, efficient windows, etc.) can cut operational and embodied carbon by using bio-based or recycled materials. Retrofitting also poses lower risks for experimenting with new materials; architects might be more willing to try hempcrete insulation or a mycelium acoustic panel in an existing building retrofit (where it’s an add-on) than in new construction. As a result, retrofit projects can become living laboratories for bio-based materials

Curate your own material library. Start a shared folder or shelf with verified bio-based samples and data sheets for your studio.

Bridging the gaps between agriculture, research, manufacturing, and design is key to scaling bio-based materials, and new collaborations are forming to do exactly that. The Bio-based Materials Collective (BBMC), for example, is a North American network of over 750 professionals including farmers, processors, architects, builders, and academics, all working together to grow regional bio-based material supply chains. By uniting stakeholders from field to construction site, such coalitions can address challenges holistically, from improving crop yields, to developing processing facilities, to updating building codes and training builders. Similarly, the Seed Collaborative is a growing decentralized network of biobased manufacturers. This program serves as an incubator to grow place-based straw panel manufacturing in regions across the U.S.

High-profile partnerships are also demonstrating what interdisciplinary teamwork can achieve. A notable case is the collaboration between Prometheus Materials (a biotech startup) and SOM to develop an algae-based concrete that absorbs CO₂. Another example is Arup’s partnership with GXN in the EU-funded BioBuild project (Stott 2015). They jointly created the world’s first self-supporting bio-composite façade panels made of flax fibers and bio-resin, which meet fire and structural codes in multiple countries. Partnerships like this support testing material performance across diverse climates and typologies, accelerated innovation pipelines, and building shared knowledge for broader industry transformation (Logan 2024).

Figure 5: Stakeholders in bio-based materials development. Adapted from the Bio-Based Materials Collaborative. Source: https://biobasedcollective.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/biobased-materials-collective-2025-summit-proceedings.pdf

Bio-based and natural materials offer multidimensional performance advantages, making them viable, highperforming alternatives to conventional products. They are renewable and biodegradable, with substantially lower carbon footprints than concrete and steel (Magwood et al. 2025a), and they can perform competitively across thermal, acoustic, fire, structural, and health criteria (Ye et al. 2025; Jones and Brischke 2017; Raja et al. 2023).

nj Thermal insulation: Straw bale, hempcrete, cellulose, cork, wool, mycelium, and other fibers provide strong insulation, with case studies showing reduced heating and cooling demand (Ba et al. 2025; Biks et al. 2019; Wang and Wang 2023; Parlato and Porto 2020; Circular Material Library, n.d.; Yildiz et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2017; Cosentino et al. 2023).

nj Moisture buffering: Hempcrete, clay plasters, wool, and wood fiber products can regulate humidity and contribute to indoor comfort (Mahmood et al. 2024; Coates 2025).

nj Acoustics: Wool, cork, straw bale, mycelium panels, and other natural fibers provide strong sound absorption compared to petrochemical-based products (Quirion and Plamondon 2025; Bravo-Moncayo et al. 2024; Profi-Guide 2023; Mogu, n.d.; Cascone et al. 2019).

nj Fire performance: Materials such as mass timber, hempcrete, and lime-plastered straw bale assemblies can meet fire requirements when properly designed (AriasCárdenas et al. 2024; Think Wood 2018; Yang et al. 2022; Kim 2018).

nj Structural performance: Many bio-based materials show sufficient strength and stability for a range of applications, including solid wood and engineered timber, bamboo, and stabilized rammed earth in load-bearing roles, and hempcrete and straw bale in wall assemblies. Stabilized rammed earth has demonstrated sufficient load-bearing capacity, with durability comparable to masonry when properly detailed (Barbhuiya et al. 2025; Koh and Kraniotis 2020; Arslan et al. 2017; Baibordy et al. 2025; Ma et al. 2025).

nj Indoor air quality: Many natural products are free of harmful additives, and some (e.g., cellulose, wool, hemp and wood fiber, hempcrete, rigid wood fiber, and clay plasters) absorb pollutants like formaldehyde, actively improving IAQ (Raja et al. 2023; Legge 2024).

Additionally, demonstration projects are critical to scaling bio-based materials, as they validate performance under real-world conditions, address skepticism about durability and scalability, and provide lessons for design and construction teams (Fischer and Losacker 2025; Bio-based Materials Collective 2025). Scholars emphasize that these built experiments help normalize material innovation, with public-facing outcomes that raise awareness among both practitioners and communities (Ghazvinian and Gürsoy 2022). By making performance visible and accessible, demonstration projects de-risk innovation, accelerate knowledge transfer, and encourage replication.

Several high-profile case studies highlight how experimental architecture is shaping professional and public perception of bio-based materials. Installations such as The Growing Pavilion (mycelium and agricultural residues), Hy-Fi Pavilion (mycelium bricks), Hidika Ohmu Pavilion (seaweed bioplastic), the Picoplanktonics Pavilion (cyanobacteria), and other international showcases demonstrate structural and aesthetic viability at architectural scale.

These projects illustrate that bio-based materials can be successfully applied across a spectrum of contexts and project scopes, when paired with careful design, early engagement with suppliers and fabricators, and a willingness to prototype.

NOTE

All building materials (conventional or bio-based) must comply with various performance aspects of the building code. The intent of this section is to highlight comparative performance characteristics pointed out in reviewed research, not to suggest that only certain bio-based materials can meet these standards. These examples illustrate a non-exhaustive range of products that can deliver these outcomes when appropriately detailed. See Tables 3, 4 and 5 in the Context and Applications in Architecture breakout of this report for more information regarding application possibilities.

The Hy-Fi installation demonstrated the aesthetic and functional possibilities of mycelium composites in a dramatic way (and after the summer installation, the bricks were simply composted, underlining the circular ethos). Picoplanktonics, an installation in the Canada Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Biennale, represents four years of interdisciplinary research (Figure 6). It includes a series of large format robotically printed structures that contain live picoplankton. These cyanobacteria strengthen the structures over time by consuming and storing CO₂ and creating minerals and oxygen (https://picoplanktonics.com).

Recent work also notes that community-level projects, such as Cork Collective + Corkeen playgrounds and bio-based urban furniture prototypes, are broadening exposure beyond academic or art contexts, embedding bio-based materials in everyday environments (Fischer and Losacker 2025). Other public-facing demos include “living labs” where people can touch and feel materials. For example, the recent “bio-based petting zoo” exhibit at the Living Future 25 Conference in Portland, Oregon allowed visitors to experience dozens of natural material samples in-person. Another example, Third Space Commons at the University of British Columbia, is a high-performance “living lab” and collaboration space exemplifying the use of timber, reclaimed materials, and hemp-lime insulation that is exposed to double as an interior wall surface. Collectively, these projects illustrate that demonstration and pilot-scale applications serve as both technical testing opportunities and communication tools that expand familiarity, build industry confidence, and create momentum for broader market uptake of bio-based solutions.

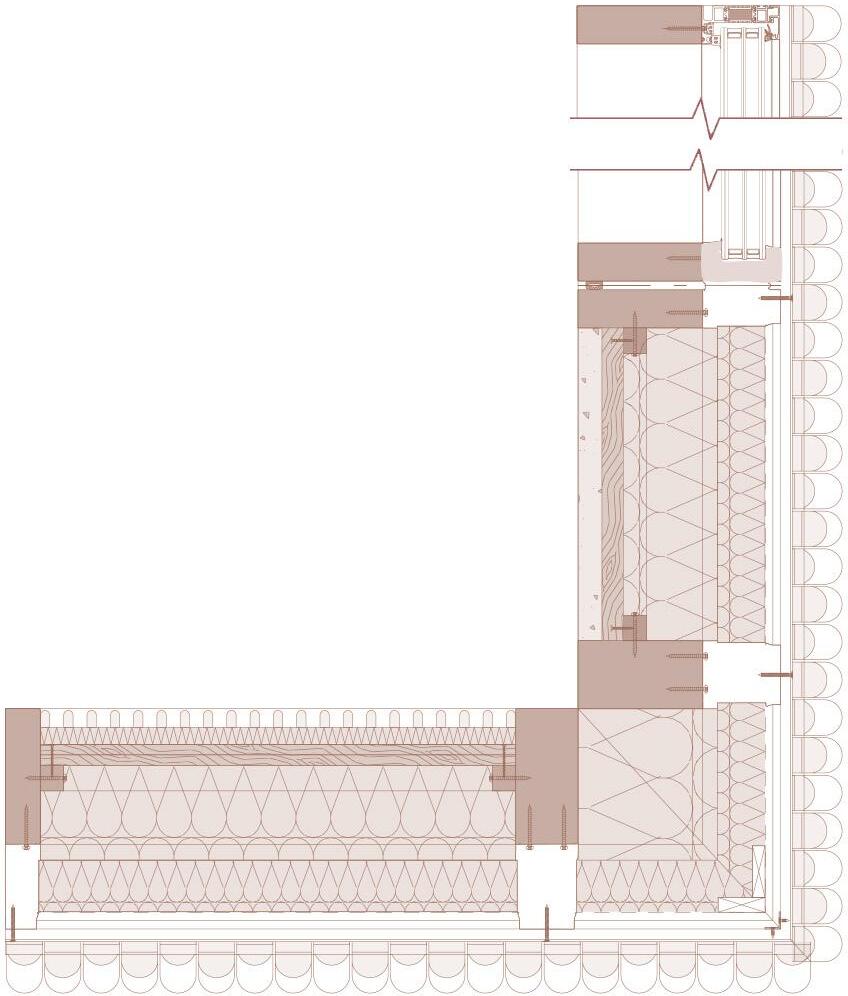

The Pilefaçade Project (Copenhagen, 2025) illustrates how emergent bio-based materials can advance from isolated experimentation to viable architectural systems. Coordinated by a multi-disciplinary team including Schmidt Hammer Lassen, MOOW (Made out of Willow), STATICUS, and PileByg, the initiative addresses a persistent barrier to bio-based materials: their marginalization as niche, smallscale, or non-integrated systems. The team demonstrates how architects, cultivators, engineers, and manufacturers can collaborate to elevate riparian willow, an underutilized regional resource, into a scalable, low-carbon façade product. By redirecting a material typically burned as biomass into a longer-lived architectural application, the project helps establish new value chains and supports regional circular economies.

Willow (Salix), sometimes referred to as “Nordic bamboo,” is fast-growing, regenerates from its stump, and reaches harvestable size within 4–8 years, eliminating the need for replanting. Its cultivation enhances biodiversity, supports soil health, and sequesters 10–15 tonnes of CO₂ per hectare annually. Selectively bred varieties such as Salix viminalis and Salix dasyclados offer straight, consistent growth suited to industrial uses. Because willow is cultivable across much of the Northern Hemisphere, it presents a scalable, lowimpact alternative to imported timber species.

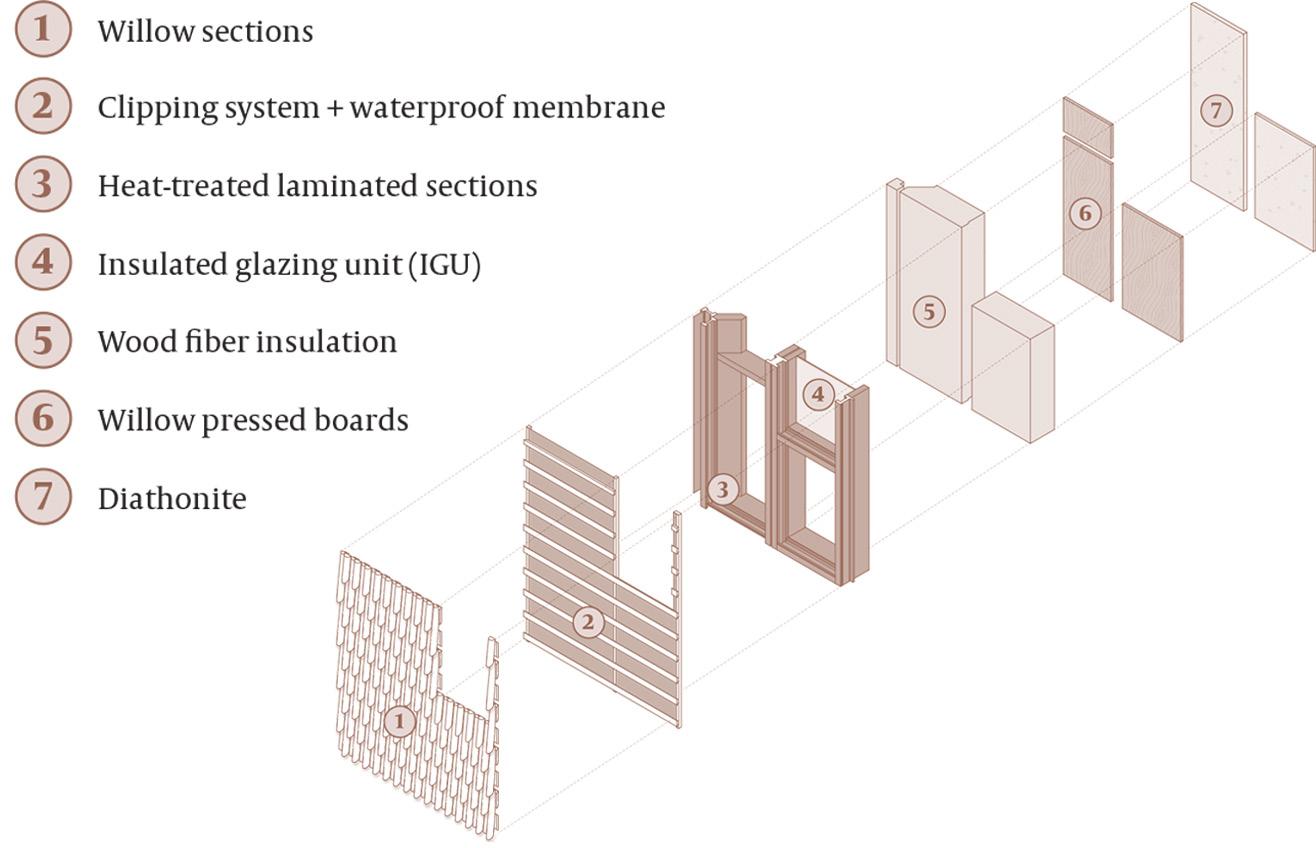

The team developed a digitally fabricated, unitized façade system that utilizes the entire plant, aligning with circulareconomy principles. For this project, willow was processed into three key façade components:

• Pressed boards from bark and trimmings (residue stream)

• Laminated profiles from thicker branches

• Rainscreen cladding made from slender rods

This full-utilization model significantly reduces waste, and early assessments suggest that substituting standard opaque façade elements with willow can reduce embodied carbon by more than 50%. Laminated willow profiles replaced conventional aluminum members in a hybrid curtain wall assembly, paired with recycled aluminum caps for weather-tightness and fire performance. The result balances functional requirements with substantial carbon reductions while demonstrating compatibility with established construction systems.

Initial findings indicate savings of up to 150 kg CO₂e/m² façade area compared to standard aluminum unitized façades and roughly 75% lower emissions per linear meter of frame, with additional biogenic benefits not yet reflected in LCA models.

Scaling the system required resolving technical challenges. Cracking during accelerated heat treatment prompted new drying protocols, including pre-drying components before lamination. Screw-fastening tests showed no splitting, but broader structural evaluation is needed. Fire safety and code compliance continue to be hurdles, especially for use above two stories. Advancing from TRL 5 to TRL 8 will require streamlined supply-chain coordination and full-scale pilots to validate moisture, thermal, wind, and fire performance.

By treating willow as a complete design system, from cultivation to curtain wall, the Pilefaçade Project provides a compelling model for integrating bio-based materials into mainstream practice, pointing toward façades that store carbon, support ecosystems, and strengthen local economies.

Despite promising developments, several barriers continue to limit widespread adoption:

Bio-based materials are frequently dismissed as fragile, costly, or niche, due to limited exposure, data, standards, and precedents (Logan 2024; Mazzoni and Losacker 2024). Despite evidence of strong performance and regulatory acceptance, misconceptions persist (Global Market Insights 2024). Aesthetically, many bio-based materials are dismissed due to their association with vernacular aesthetics, but traditional methodologies can enhance modern architecture, debunking the idea that bio-based construction cannot meet contemporary standards (Dorsey 2022). These perceptions affect broader cultural patterns of consumption in the Global North, where convenience and uniformity are normalized despite ecological costs. (Peters and Drewes 2019). “Such bias stems from modernist values that privilege thin, lightweight, single-use products over multifunctional systems like strawbale, which can serve simultaneously as structure and insulation” (Sykes 2024).

While many bio-based technologies are already available, overcoming dismissive biases requires training across the entire value chain. This may include vocational programs, professional education, and industry associations to normalize their use (Göswein et al. 2022). Furthermore, bio-based materials must be reframed so they may be understood as enablers of architectural and conceptual innovation that can broaden language design. By highlighting successful projects that demonstrate performance, versatility, and aesthetic potential, the industry can shift bio-based materials from the margins to the mainstream.

Policy and regulatory frameworks remain a central barrier to scaling bio-based construction, particularly in North America, where standards and procurement systems are still heavily aligned with petrochemical incumbents and conventional mineral products (Peltier et al. 2023). While procurement policies are beginning to send demand signals for low-carbon alternatives, they remain fragmented and inconsistently applied across states (Peltier et al. 2023). Without harmonized codes or consistent certification pathways, bio-based products remain disadvantaged (Chen et al. 2024).

The slow pace of reform, illustrated by the years of advocacy required for mass timber’s high-rise construction approval, highlights the lengthy process that most developing materials will face in gaining recognition and market entry. Aligning U.S. procurement, certification, and code processes with carbon reduction goals, alongside cross-sectoral policies that link agriculture, energy, and construction, would secure demand, enable local producers to scale, and build workforce capacity (Dams et al. 2023). Top-down measures, such as procurement requirements or minimum bio-based content in codes, could further de-risk adoption and create stable conditions for market growth (Göswein et al. 2022).

Build material confidence. Host or attend a “biobased show-and-tell” with samples and suppliers. Familiarity dismantles risk aversion.

Abundant resources such as straw, hemp, and bamboo are underutilized because structured value chains to reliably process and deliver them are lacking (Dams et al. 2023a). Unlike conventional materials with established distribution channels, bio-based products often face limited suppliers and contractor unfamiliarity, hindering procurement at scale. Middle actors (contractors, subcontractors, site managers) in construction will need training to build confidence with these systems, and without stronger distribution networks, limited availability and inexperience reinforce one another (Dams et al. 2023a; Simpson et al. 2020).

Supply chains can involve new products as well as reclaimed materials. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation notes that scaling bio-based materials for a circular economy relies on the infrastructure to collect and separate clean organic streams after they fall out of use. (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2021a). Hybrid assemblies and composites, which can include glue, resin, concrete, or other materials that cannot be separated from bio-based components, are still common. Design for separability is required to enable the cycling of biomass into future supply chains as reclaimed raw materials or as nutrients. Otherwise, bio-based materials will be lost to landfill or incineration at their endof-use (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2021b).

Because bio-based building materials are still emerging, the upfront costs associated with developing, testing, and certifying them can be high, reinforcing market resistance. Manufacturers and innovators face significant expenses to scale up production and demonstrate compliance with safety codes, while traditional materials have long since amortized these costs (Dams et al. 2023a; Bio-based Materials Collective 2023). At the same time, financial comparisons typically prioritize upfront costs while ignoring long-term operational savings, carbon benefits, or ecosystem contributions (Global Market Insights 2024).

Due to a lack of standardized testing for many of these materials, each new application may require one-off engineering assessments, adding time and expense. This can deter manufacturers, especially smaller companies with limited budgets, from pursuing approvals altogether (Shivakumar et al. 2023). The ultimate result is a higher initial price point, which can discourage cost-sensitive clients and developers. Without financial incentives or supportive policies, these barriers reinforce market resistance. However, as production scale and availability increase, costs should decline, making bio-based options more competitive in mainstream construction (Peltier et al. 2023).

The risk-averse, conservative construction sector slows the uptake of bio-based materials (Dams et al. 2023a). Building projects operate within a highly regulated and liabilityconscious environment, where safety, durability, and code compliance are paramount. As a result, practitioners often default to conventional materials such as concrete, steel, and plastics, which have long-established performance records, standardized certifications, and widespread market familiarity (Mazzoni and Losacker 2024; Gibbs and O’Neill 2015). Many bio-based materials are newer to the market; they may have little performance data or have limited thirdparty verification. This perception of uncertainty discourages specification, even when pilot projects demonstrate positive results (Jayaweera et al. 2023; Shivakumar et al. 2023). The reluctance to experiment reinforces a cycle in which limited demand keeps costs high and delays the scaling of production, further entrenching the perception of risk (Göswein et al. 2022; Fastenrath and Braun 2018). As a result, bio-based products are often excluded not because of a lack of technical potential, but because of industry actors’ preference for the familiar and their resistance to deviating from established norms.

In parallel, the industry’s entrenched industrialized culture makes systemic change difficult. Construction processes, procurement pathways, and labor skills have evolved around mass-produced, fossil-fuel-based materials supplied through centralized global chains. Bio-based materials often require different sourcing models, more localized supply, or altered construction methods that do not align with existing workflows (Finkbeiner et al. 2020). This structural inertia can marginalize bio-based products. Suppliers of bio-based products confirm this perception, noting they are “not taken seriously” unless they themselves invest in demonstrating compliance and training contractors (Koschatzky and Stahlecker 2023). Combined with risk aversion, this industrial path dependency slows innovation and impedes the development of a robust bio-materials economy (Dams et al. 2023a). Overcoming these cultural and structural barriers will require technical validation accompanied by shifts in procurement practices, supply chains, and professional mindsets.

Limited standardized testing protocols and data is a recurring barrier to wider adoption of bio-based building materials. This stems from material variability, limited long-term performance data, and immature certification frameworks, creating inconsistency across testing and validation procedures (Mahmood et al. 2024). This absence of harmonized methods means that material durability, fire safety, or mechanical strength must frequently be assessed on a case-by-case basis, which increases costs and uncertainty. (Hedley-Smith and Stainton 2024; Dams et al. 2023a).

Data transparency and methodological consistency in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) are also limiting factors (International Living Future Institute (ILFI) and Grable 2023, 155). For example, “Carbon: Misaligned Calculation Methodologies and Incentives” was named as one of six overarching challenges to adoption of mass timber in a recent Mass Timber Tipping Point study (Southwood et al. 2025). Diverging approaches to biogenic carbon accounting and LCA continue among practitioners, certification bodies, and policy standards, create confusion and limit credibility (Hoxha et al. 2020). As a result, the benefits of carbon sequestration are not consistently captured or understood, constraining the ability of these materials to compete in procurement systems increasingly tied to LCA metrics.

The Carbon Leadership Forum (CLF) and Bio-Based Materials Collective (BBMC) both emphasize the need for harmonized LCA and Product Category Rules (PCRs) methodologies to fully recognize the value of bio-based materials (Ellingboe et al. 2025; Hoxha et al. 2020; Biobased Materials Collective 2025). While updates to standards progress, such as through the ECHO project’s alignment efforts (Lewis et al. 2024), near-term transparency data is still needed. As of October 2025, the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (the EC3 tool), a primary database of EPDs in North America, includes over 80,000 concrete EPDs and over 16,000 EPDs for other products (Building Transparency 2025). Only 70 of these EPDs are for wood-based, and there are no search filters to enable identification of other bio based products. Similarly, CLF’s 2025 Materials Baselines Report includes just 26 bio-based categories (7% of 367 total), signaling progress but persistent underrepresentation (Waldman, et al. 2025).

Policies, pilot projects, and growing consumer demand are creating clear momentum toward bio-based construction, supported by expanding research and regional production networks. Yet persistent inertia remains in the form of fragmented standards, limited supply chains, and cautious market behavior. These forces define a sector in transition, where proof of concept is abundant, but normalization is still evolving.

Taken together, these factors explain why bio-based materials are visible but not yet routine in North American commercial work: technical feasibility is increasingly clear, while market mechanisms, approvals, and supply coordination lag. The Interpretation section on the following page summarizes where momentum is strongest, where inertia persists, and how near-term choices, reflected in the commercially available and early adoption matrices in the accompanying Context and Applications in Architecture breakout of this report, can translate evidence into practice.

Action for Designers:

Advocate for policy change. Engage in public consultation on codes and procurement to include bio-based content requirements.

Multiple forces are now pushing bio-based materials from niche experimentation toward viable application in North American projects.

On the technology side, universities and startups are scaling cultivation and fabrication. Circular and regional production models are gaining traction as reports highlight the United States’ large, underutilized biomass streams that can be upcycled into building components, creating rural jobs while displacing higher-carbon products. Policy shifts are beginning to register: “Buy Clean” procurement is spreading across states, ICC code appendices now recognize straw-bale and cob, and tall mass-timber provisions have expanded, signaling growing regulatory comfort with bio-based systems. Meanwhile, market drivers, including demand for product transparency, growth in digital libraries, and public demonstration projects, are reducing perceived risk through vetted data, precedents, and handson exposure. The aging building stock further amplifies these tailwinds: Retrofits create near-term opportunities to substitute bio-based products in envelopes and interiors with comparatively low programmatic risk.

At the same time, entrenched frictions still slow uptake.

Visibility and perception gaps persist, with many stakeholders defaulting to familiar materials and aesthetics despite growing evidence of performance. Code, policy, and certification pathways remain inconsistent, and where codes offer few direct routes, one-off approvals and bespoke engineering inflate time and cost, particularly for smaller manufacturers. Fragmented supply chains and limited contractor familiarity hinder reliable, large-scale procurement, while data and testing gaps complicate benchmarking. Prevailing cost comparisons often emphasize first cost over long-term benefits. These structural and cultural factors reinforce a conservative, liability-averse stance that keeps demand thin and prices high. The outlook is nevertheless encouraging: As more jurisdictions adopt low-carbon procurement policies, as standardized pathways (and selective ISO/ICC recognitions) expand, and as demonstration projects, collaborations, and retrofit programs accumulate proof at scale, the balance is likely to tip toward broader specification.

Momentum is building across technology, policy, and market practice. With sustained alignment between codes, climate action and a renewed interest in bioregional economies and place-based design, today’s pockets of bio-based innovation could evolve into mainstream delivery. Here, the building industry holds a pivotal opportunity to influence that trajectory.

* Wood products are not a primary focus of this paper; however, our Getting to Craft in Mass Timber guide provides more information on climate responsibility and ecological wood sourcing.

Demand for low-carbon products is one of the strongest drivers behind bio-based materials (Dams et al. 2023b; Haramati and Hyne 2025). Many of these materials, including wood and engineered timber, bamboo, hemp, algae, mycelium, and others, act as natural carbon sinks, storing biogenic carbon over the life of the product (Breschi 2023; Hebel and Heisel 2017b). However, our review indicates that carbon benefits are not inherent; they depend on forest or crop dynamics, land management, product lifespans, accounting practices, and end-of-use pathways (Hoxha et al. 2020b; Southwood et al. 2025).

In North America, current evidence suggests a relatively favorable context for many wood products. U.S. forest carbon stocks have increased by roughly 12% since 1990, and Canadian managed forests likewise continue to store and sequester carbon, meaning that in many jurisdictions harvested wood is unlikely to deplete forest carbon stocks when regrowth and management are taken into account (Hoover and Riddle 2023; Kurz et al. 2016). At the same time, all biological materials, including timber, fastgrowing crops, and agricultural residues, can be associated with land-use practices that drive monoculture, habitat loss, pesticide use, or land use change if they are not carefully stewarded.*

From a practice standpoint, this points toward diversification and place-sensitivity rather than a single “solution” material. Bio-based and natural products are most robust when treated as a portfolio: combining responsibly sourced forest biomass with fast-growing crops and agricultural byproducts to spread risk, support multiple landscapes, and avoid over-harvesting any single feedstock (Pomponi et al. 2020; Magwood et al. 2025b). For design teams, the task is less about finding a universally “regenerative” material and more about asking context-specific questions: How is this feedstock grown and harvested? Does it displace higher-impact products without driving land use change? Is it linked to restorative or extractive forms of agriculture and forestry? Seen in this light, carbon performance, sourcing, and diversification can be understood as interpretive lenses versus fixed attributes. As disclosure improves and supply chains mature, project teams will be better able to distinguish genuinely regenerative options from those that simply repackage industrial practices, and to align material choices with the regional ecologies and communities that sustain them.

The following actions can help translate bio-based and natural materials into widespread practice:

• Identify pilot and demonstration opportunities. Test bio-based assemblies in focused applications like energy retrofits, interiors, and smaller project features. Transform pilot initiatives into collective learning assets by publishing results, supporting open data, and encouraging replication across regions.

• Diversify your material palette. Combine slow and fast-cycling crops (e.g., wood, straw, and bamboo) to balance renewability, biodiversity, and supply chain stability. Prioritize residues (e.g., straw, husks, bark, bagasse) when feasible to avoid additional land-use pressure.

• Invest in regional supplychain development. Engage with emerging producers, cooperatives, and agricultural partners to help build the reliable, distributed infrastructure needed for scaling bio-based materials.

• Support standardization, data quality, and transparency. Request EPDs that track biogenic and fossil carbon separately. Participate in efforts to harmonize biogenic carbon accounting, improve PCRs, and expand thirdparty verification so bio-based products can compete in procurement systems that are increasingly tied to disclosure.

• Contribute to expanding testing and certification pathways. Collaborate with manufacturers, researchers, fire officials, engineers, and AHJs to help develop repeatable pathways for fire, durability, and structural testing, reducing reliance on one-off approvals.

• Collaborate across sectors to align demand, policy, and production. Strengthen connections between design practice, forestry, agriculture, manufacturing, academia, and policy networks to address land stewardship, certification barriers, and production gaps at a systems level.

The material-specific terms noted below are often used interchangeably, but they’re not the same. Understanding their differences is essential for making informed material choices.

Abiotic Derived from non-living geological processes. In this report, we’ve used the more familiar term “natural” to describe abiotic materials that are abundant and regionally available, with low embodied carbon and capacity to be reused or broken down and reintroduced into natural cycles at their end-of-use.

Biological Materials derived from living organisms (plants, animals, fungi, microbes) that can participate in biological processes like growth, regeneration, decomposition, or nutrient cycling.

Bio-based materials

Bio-based synthetics and polymers

Biogenic carbon

Biophilic

Bioregional

Ecological

Fossil-based

Natural materials

Materials that are wholly or partly derived from living or recently living biological resources. This term refers to the origin of the material, not its end-of-use behavior as a product. Materials developed with bio-based feedstocks are not always biodegradable or compostable.

Materials that are partially derived from biological inputs (e.g., corn, castor oil, sugarcane, algae) and processed into synthetic forms, such as bioplastics or bio-based resins with plant-based feedstocks. These may offer meaningful health and environmental benefits over their conventional, fossil- and chemicalbased counterparts. However, they are hybrids in nature (not pure biological materials) and may not be biodegradable or recyclable.

The carbon stored in or emitted from bio-based materials. Living organisms are partially composed of organic carbon that is captured through natural biological processes. When used responsibly, bio-based products can contribute to their own “carbon pools” over time, storing carbon alongside natural pools like soil and belowground biomass (U.S. EPA 2020).*

Fostering a connection to nature and support human well-being by engaging in our senses or referencing natural patterns, textures, or cycles. Biophilic design and materials do not necessarily include biological elements.

Sourced, processed, and applied within a local ecological context, using what’s available in and appropriate to the surrounding bioregion.

Materials developed or used in ways that minimize harm to ecosystems and ideally support biodiversity, resource regeneration, and climate resilience.

Derived from organic matter that comes from a geological reserve of ancient carbon. Fossil-based materials have been removed from rapidly renewable biological cycles for millions of years and are finite.

Materials that occur in nature and can be used with minimal processing or chemical alteration but are not bio-based. These materials have their own cycles. For example, earthen materials can be broken down and reintegrated into mineral soil or reused as raw material. Lime gains strength over time and can self-heal minor cracks due to the carbonation stage of the “lime cycle,” reabsorbing CO₂ that was produced during calcination. However, not all natural materials are automatically low-impact or regenerative, as some require extensive excavation, heat, chemicals, or other intensive manufacturing inputs.

Regenerative

Table 2: Key Terms and Definitions

Materials or systems that have net-positive benefits for environmental and human well-being across their entire life cycle. Where sustainability aims to reduce harm, regeneration seeks to restore and revitalize living systems. This is a shift from efficiency to reciprocity; from doing less bad to doing better.

* NOTE: Per the US EPA, “Timber Products in Use” account for ~3% of total carbon stored across forest carbon pools; this “product based” pool continues to grow as wood products enter and remain in use (U.S. EPA 2020). More information is also available in Tsay Jacobs et al. 2023, pages 20–21.

We gratefully acknowledge:

nj The Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we work and learn, whose deep relationships with the natural world have long guided regenerative practices, and who continue to teach us what it means to care for land, living systems and community.

nj Highly respected external experts from New Frameworks, Parsons Healthy Materials Lab, Rocky Mountain Institute, MASS Design Group, and the Bio-Based Materials Collective who generously shared their knowledge, case studies, and vision for regenerative design.

nj The designers, researchers, and sustainability leaders across Perkins&Will who provided insights, critical feedback, and creative ideas throughout the process.

nj Authors, thought leaders, and industry guides, whose work is shaping our understanding of bio-based and natural materials.

nj The growing global community of builders, makers, and advocates who demonstrate what’s possible when design reconnects to living systems.

We also acknowledge the use of AIassisted writing tools (OpenAI’s ChatGPT) to support editing and synthesis; all interpretations and conclusions reflect the judgement of the authors.

We extend thanks to everyone who challenged assumptions, asked critical questions, and helped shape this resource into a tool for meaningful change.

1. Abdelhady, Omar, Evgenia Spyridonos, and Hanaa Dahy. 2023. “Bio Modules: Mycelium-Based Composites Forming a Modular Interlocking System through a Computational Design towards Sustainable Architecture.” Designs 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.3390/designs7010020.

2. Andrew, James P., Harold L. Sirkin, and John Butman. 2006. Payback: Reaping the Rewards of Innovation. Harvard Business School Press.

3. Arias-Cárdenas, Brenda, Ana Maria Lacasta, and Laia Haurie. 2024. “Bibliometric Analysis of Research on Thermal, Acoustic, and/ or Fire Behaviour Characteristics in Bio-Based Building Materials.” Construction and Building Materials 432: 136569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. conbuildmat.2024.136569.

4. Arslan, Mehmet Emin, Mehmet Emiroğlu, and Ahmet Yalama. 2017. “Structural Behavior of Rammed Earth Walls under Lateral Cyclic Loading: A Comparative Experimental Study.” Construction and Building Materials 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.093.

5. Ba, Labouda, Abdelkrim Trabelsi, Tien Tung Ngo, Prosper Pliya, Ikram El Abbassi, and Cheikh Sidi Ethmane Kane. 2025. “Thermal Performance of Bio-Based Materials for Sustainable Building Insulation: A Numerical Study.” Fibers 13 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/fib13050052.

6. Baibordy, Aryan, Mohammad Yekrangnia, and Saeed Ghaffarpour Jahromi. 2025. “A Comprehensive Study on the Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Reinforced Stabilized Rammed Earth Using Experimental and Data-Driven Fuzzy Logic-Based Analysis.” Cleaner Materials 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. clema.2025.100300.

7. Barbhuiya, Salim, Bibhuti Bhusan Das, Kanish Kapoor, Avik Das, and Vasudha Katare. 2025. “Mechanical Performance of Bio-Based Materials in Structural Applications: A Comprehensive Review.” Structures 75. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.istruc.2025.108726.

8. Biks, Yuriy, Georgiy Ratushnyak, and Olga Ratushnyak. 2019. “Energy Performance Assessment of Envelopes from Organic Materials.” Architecture, Civil Engineering, Environment 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.21307/acee-2019-036.

9. Bio-based Materials Collective. 2023. Northeast Bio-Based Materials Collective 2023 Summit Proceedings. Bio-based Materials Collective. https:// biobasedcollective.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/bio-based-materialscollective-2023-summit-proceedings.pdf.

10. Bio-based Materials Collective. 2025. 2025 Summit Proceedings. Biobased Materials Collective. https://biobasedcollective.org/wp-content/ uploads/2025/07/bio-based-materials-collective-2025-summitproceedings.pdf.

11. Bravo-Moncayo, Luis, Marcelo Argotti-Gómez, Oscar Jara, Virginia PuyanaRomero, Giuseppe Ciaburro, and Víctor H. Guerrero. 2024. “Thermo-Acoustic Properties of Four Natural Fibers, Musa Textilis, Furcraea Andina, Cocos Nucifera, and Schoenoplectus Californicus, for Building Applications.” Buildings 14 (8): 2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14082265.

12. Breschi, Tomaso. 2023. “The Green Revolution in the Built Environment: Bio-Based Materials.” Revalu. https://www.revalu.io/journal/ the-green-revolution-in-the-built-environment-bio-based-materials.

13. Building Transparency. 2025. “Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (EC3).” https:// buildingtransparency.org/ec3.

14. Business View Magazine. 2025. “Green Building Materials in Commercial Construction.” https:// businessviewmagazine.com/greenbuilding-materials-in-commercialconstruction.

15. Cascone, Stefano, Gianpiero Evola, Antonio Gagliano, Gaetano Sciuto, and Chiara Baroetto Parisi. 2019. “Laboratory and In-Situ Measurements for Thermal and Acoustic Performance of Straw Bales.” Sustainability, ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su11205592.

16. Chen, Lin, Yubing Zhang, Zhonghao Chen, et al. 2024. “Biomaterials Technology and Policies in the Building Sector: A Review.” Environmental Chemistry Letters 22: 715–50. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01689-w.

17. Circular Material Library. n.d. “Mycelium Insulation Panel | Insulation Panels Made from Mycelium.” https:// circularmateriallibrary.org/material/ mycelium-insulation-panel/.

18. Climate Smart Wood Group. 2025. “Climate Smart Wood Group.” https:// www.climatesmartwood.net/.

19. Coates, Aron. 2025. “What Is Hempcrete? Everything You Need to Know.” Designs in Detail. https://www. designsindetail.com/articles/what-ishempcrete-everything-you-need-toknow.

20. Cosentino, Livia, Jorge Fernandes, and Ricardo Mateus. 2023. A Review of Natural Bio-Based Insulation Materials. 16 (12). https://doi. org/10.3390/en16124676.

21. Dams, Barrie, Dan Maskell, Andrew Shea, Stephen Allen, Valeria Cascione, and Pete Walker. 2023a. “Upscaling Bio-Based Construction: Challenges and Opportunities.” Building Research & Information 51 (7): 764–82. https://

doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2023.2204 414.

22. Dams, Barrie, Dan Maskell, Andrew Shea, Stephen Allen, Valeria Cascione, and Pete Walker. 2023b. “Upscaling Bio-Based Construction: Challenges and Opportunities.” Building Research & Information 51 (7): 764–82. https:// doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2023.2204 414.

23. Dataintelo. 2025. Bio-Based Building Materials Market Report. Dataintelo. https://dataintelo.com/report/ bio-based-building-materials-market.

24. Dorsey, Bryan. 2022. “Building a Foundation of Pragmatic Architectural Theory to Support More Sustainable or Regenerative Straw Bale Building and Code Adoption.” Journal of Sustainability Research 4 (2): e220003. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20220003.

25. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2017. Urban Biocycles. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. https://www. ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ cities-urban-biocycles.

26. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2021a. “Effective Organic Collection Systems.” https:// www.ellenmacarthurfoundation. org/circular-examples/ effective-organic-collection-systems.

27. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2021b. “The Butterfly Diagram: Visualizing the Circular Economy.” https://www. ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ circular-economy-diagram.

28. Ellingboe, Ethan, Karisha Shahnaz Hariadi, and Stephanie Carlisle. 2025. Biogenic Carbon Accounting in Environmental Product Declarations: A Comparison of Methodologies in European and North American Wood Product EPDs. Carbon Leadership Forum. https://hdl.handle. net/1773/53048.

29. European Commission. 2018. “Bioeconomy Strategy.” https:// environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/ bioeconomy-strategy_en.

30. Fastenrath, Sebastian, and Boris Braun. 2018. “Sustainability Transition Pathways in the Building Sector: Energy-Efficient Building in Freiburg (Germany).” Applied Geography 90: 339–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. apgeog.2016.09.004.

31. Finkbeiner, Marco, Maik Pannok, Henrik Fasel, Julia Riese, and Stefan Lier. 2020. “Modular Production with Bio-Based Resources in a Decentral Production Network.” Chemie Ingenieur Technik 92 (12): 2041–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cite.202000072.

32. Fischer, Lennart, and Sebastian Losacker. 2025. “How to Build (in) the Future? Legitimacy of SocioTechnical Visions in a Bio-Based Construction Sector.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, no. 100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. eist.2025.100996.

33. Fortune Business Insights. 2025. Cross Laminated Timber Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis, By Bonding Technology (Adhesive Bonded and Mechanically Fastened), By Application (Residential Buildings, Non-Residential Buildings, and Others), and Regional Forecast, 2024-2032. Fortune Business Insights. https://www.fortunebusinessinsights. com/cross-laminated-timber-cltmarket-102884.

34. Gattupalli, Ankitha. 2024. “Building Better with Data: The Role of Material Libraries in Sustainable Architecture.” ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/1019364/building-better-withdata-the-role-of-material-libraries-insustainable-architecture.

35. Ghazvinian, Ali, and Benay Gürsoy. 2022. “Challenges and Advantages of Building with Mycelium-Based Composites: A Review of Growth Factors That Affect the Material Properties.” In Fungal Biopolymers

and Biocomposites, edited by Sunil K. Deshmukh, Mukund V. Deshpande, and Kandikere R. Sridhar. Springer. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1000-5_8.

36. Gibbs, David, and Kirstie O’Neill. 2015. “Building a Green Economy? Sustainability Transitions in the UK Building Sector.” Geoforum 59: 133–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. geoforum.2014.12.004.

37. Global Market Insights. 2024. “Bio-Based Building Materials Market: Global Forecast (20242032).” https://www.gminsights. com/industry-analysis/ bio-based-building-materials-market.

38. Göswein, Verena, Jay Arehart, Catherine Phan-huy, Francesco Pomponi, and Guillaume Habert. 2022. “Barriers and Opportunities of Fast-Growing Biobased Material Use in Buildings.” Buildings and Cities 1 (745–755). https://doi.org/10.5334/ bc.254.

39. Grand View Research. 2024. Hempcrete Market (2025 - 2030). Grand View Research. https:// www.grandviewresearch. com/industry-analysis/ hempcrete-market-report.

40. Haramati, Mikhail, and Rick Hyne. 2025. “The Key to Lowering a Building’s Carbon Footprint? Embodied Carbon.” Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). https://www.nrdc. org/bio/mikhail-haramati/keylowering-buildings-carbon-footprintembodied-carbon.

41. Hebel, Dirk E., and Felix Heisel. 2017a. Cultivated Building Materials: Industrialized Natural Resources for Architecture and Construction. Birkhauser. https://birkhauser.com/en/ book/9783035608922.

42. Hebel, Dirk E., and Felix Heisel. 2017b. Cultivated Building Materials: Industrialized Natural Resources for Architecture and Construction. Birkhauser. https://birkhauser.com/en/ book/9783035608922.

43. Hedley-Smith, Joana, and Oliver Stainton. 2024. “Are Bio-Based Materials Suitable for Mainstream Construction?” Buro Happold. https:// www.burohappold.com/news/arebio-based-materials-suitable-formainstream-construction/.

44. Hoover, Katie, and Anne A. Riddle. 2023. U.S. Forest Carbon Data: In Brief. Congress.gov. https://www.congress. gov/crs-product/R46313.

45. Hoxha, Endrit, Alexander Passer, Marcella Ruschi Mendes Saade, et al. 2020a. “Biogenic Carbon in Buildings: A Critical Overview of LCA Methods.” Buildings and Cities 1 (1): 504–24. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.46.

46. Hoxha, Endrit, Alexander Passer, Marcella Ruschi Mendes Saade, et al. 2020b. “Biogenic Carbon in Buildings: A Critical Overview of LCA Methods.” Buildings and Cities 1 (1): 504–24. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.46.

47. International Living Future Institute (ILFI), and Juliet Grable. 2023. The Regenerative Materials Movement: Dispatches from Practitioners, Researchers, and Advocates. Ecotone, International Living Future Institute (ILFI). https://store.living-future. org/products/the-regenerativematerials-movement-dispatchesfrom-practitioners-researchers-andadvocates.

48. ISED Canada. 2021. “Technology Readiness Level (TRL) Assessment Tool.” Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) Canada. https:// ised-isde.canada.ca/site/cleangrowth-hub/en/technology-readinesslevel-trl-assessment-tool.

49. Jayaweera, Ravi, Harald Rohracher, Annalena Becker, and Michael Waibel. 2023. “Houses of Cards and Concrete: (In)Stability Configurations and Seeds of Destabilisation of Phnom Penh’s Building Regime.” Geoforum 141: 103744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. geoforum.2023.103744.

50. Jones, Dennis, and Christian Brischke, eds. 2017. Performance of Bio-Based Building Materials. Elsevier. https://doi. org/10.1016/c2015-0-04364-7.

51. Kim, Dakota. 2018. “This Building Material May Hold the Key to Surviving Environmental Disasters.” Architectural Digest. https://www. architecturaldigest.com/story/ strawbale-construction.

52. Koh, Chuen Hon (Alex), and Dimitrios Kraniotis. 2020. “A Review of Material Properties and Performance of Straw Bale as Building Material.” Construction and Building Materials 259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. conbuildmat.2020.120385.

53. Koschatzky, Knut, and Thomas Stahlecker, eds. 2023. Sustainable Transformation and Resilient Structural Change in Regions. Fraunhofer Verlag. https://doi.org/10.24406/publica-860.

54. Kurz, W.A., R.A. Birdsey, V.S. Mascorro, et al. 2016. Integrated Modeling and Assessment of North American Forest Carbon Dynamics Technical Report : Tools for Monitoring, Reporting and Projecting Forest Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. Commission for Environmental Cooperation. / https://www.cec.org/files/documents/ publications/11655-integratedmodeling-and-assessment-northamerican-forest-carbon-dynamics-en. pdf.

55. Legge, Andrew. 2024. “Indoor Air Quality: Wool and Formaldehyde.” Havelock Wool. https://havelockwool. com/blogs/blog/indoor-air-qualitywool-and-formaldehyde.

56. Lewis, Meghan C., Lyndsay Watkins, Colleen Loader, and Michelle L. Lambert. 2024. Project Life Cycle Assessment Requirements: ECHO Recommendations for Alignment. ECHO Project. https://www.echoproject.info/publications.

57. Logan, Katharine. 2024. “Continuing

Education: Bio-Based Materials.” https://www.architecturalrecord.com/ articles/16974-continuing-educationbio-based-materials.

58. Ma, Jiaming, Hongru Zhang, Vahid Shobeiri, et al. 2025. “CFRP-Confined Rammed Earth towards HighPerformance Earth Construction.” Composite Structures 371. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2025.119512.

59. Magwood, Chris, Aurimas Bukauskas, Tracy Huynh, and Victor Olgyay. 2025a. Building with Biomass: A New American Harvest. Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI). https://rmi.org/insight/ building-with-biomass-a-newamerican-harvest/.