21 minute read

Precedents: North America & Canada

NORTH AMERICA & CANADA

LA’s regeneration program

Advertisement

The reason this program was founded was because the government began to understand the different methods to reduce costs in the way of socioeconomic and environmental standing, while realizing the potential of regeneration and how that could in fact bring in revenue from those same standings.

Abandoned commercial buildings became the structure of choice to adaptively reuse, as the changing times of architecture, urban fabric and developments, lead to this typology being outdated, and eventually in disuse. Therefore, it was the reuse of strip malls from earlier decades, and similar buildings, that became a target strategy to implement for urban regeneration. These structures are capable of holding a plethora of functions simultaneously - the numerous booths and shops in the plan of these buildings are able to be re-partitioned into restaurants, galleries, libraries, and the like.

For the LA program, buildings were reused into residential units. This residential regeneration of downtown LA has been a large-scale governmental project, constantly in the works since the 1960s. With the way this venture has dealt with building policy and selective criteria for choosing which buildings to adaptively reused, this program has taken exemplary, foundational steps in how to adaptively reuse across the globe.

The type of building reused was, as previously mentioned, mostly commercial, and changed into residential units, due to the lack of residential units in areas of interest within the program. Love’s paper also studied how effective the program’s outcomes were, in terms of sustainability, urban regeneration and commercial viability.

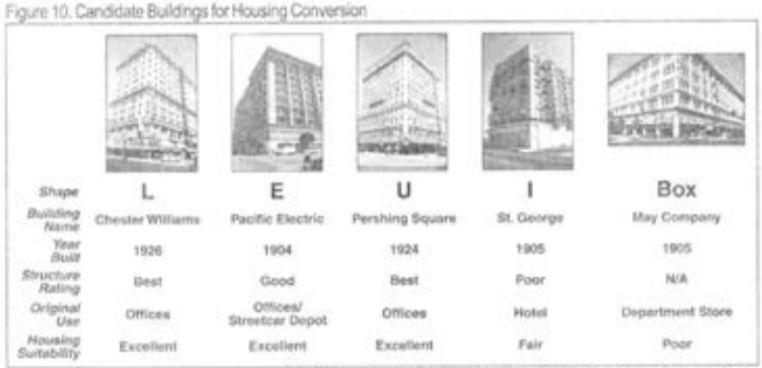

Fig 1.1 The figure above shows some of the candidate buildings for housing conversion that were put forward.[15]

One of the important steps towards beginning this process is to standardize criteria for selecting which buildings are both eligible and capable for reuse. The criteria included:

● the version of building code upon which the structure was built, ● the time before which the building was built, ● whether or not the building is economically viable within its current usage, ● whether or not the building had historical importance.

Another reality that needed to be faced was that the housing provided was initially mostly aimed at middle to higher income members. ‘Hotel-dwellers’ , or people without a stable income or lifestyle who could not afford a middle-income residential unit and therefore circulated between hotels to survive, did not have a place in the program at first. However, due to different efforts of different developers, as well as campaigns run by members of the community, the hotels did eventually get sold to property dealers. These dealers then worked on plans and strategizing to be able to house lower income residents with either affordable units, or simply better, revitalized hotel living.

[16]

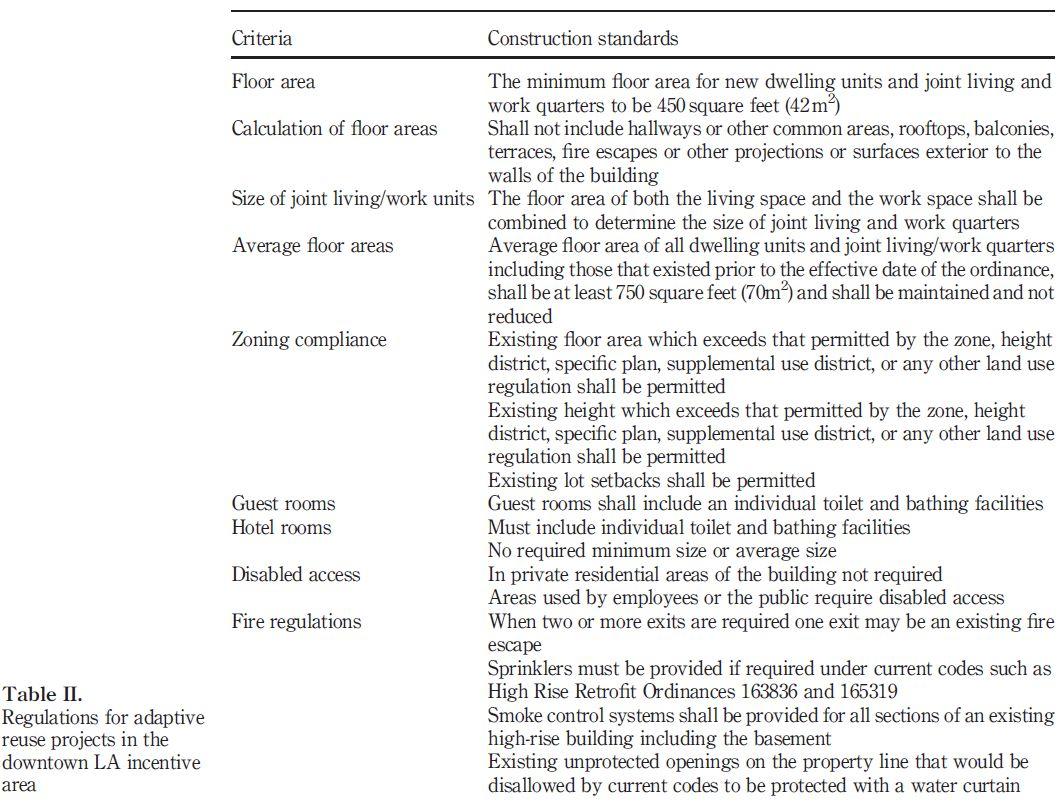

Once the buildings were undergoing the process of restructuring and repartitioning, a new occurrence arose - the adaptation of building codes for this new typology of building (reused, from one function to a residential one) and, thereby an introduction of flexibility into the standard building code. The following is a table showing how some of these differences between original and residential functions were dealt with:

Table 1.1 Regulations for adaptive reuse projects in the down LA incentive area. Peter Love.[17]

The success of this program allowed for progression to the rest of Los Angeles spanning districts such as Hollywood, Chinatown, among others. Part of this success can be attributed to the incentives the government took on, to encourage proprietors and other stakeholders in the construction industry.

Some of the incentives included:

● A range of percentage tax credit that went into the rehabilitations when dealing with different building typologies - from historic buildings to non-historical and non-residential; ● Facade easement resulting in tax deduction if a conservation easement was secured by the property owner; ● An act, Mills Act, which was passed in order to provide tax relief for historic properties for continued preservation; ● Tax credit for developers who were dealing with residential properties.

Details available for the reuse that occurred on one of the office buildings to be adapted into residential units included: an extension towards the west facade, causing different levels in the interior. This adds dynamism to the interior, and allows for additions for toilets to every floor. The north facade, on the other hand, introduces new toilets, which are not aligned with the facade of the building openings, allowing for appropriate privacy. The vertical structure was also extended, and the staircases were relocated to allow access to the extra levels created by the extension of the facades mentioned above.

As opposed to the issues that LA was facing in all the “economically distressed”[18] districts of the buildings that were adaptively reused, the results seemed not only positive as expected to the degree expected, but some areas were even more successful than planned.

The main goal - revitalization of the downtown area - was of course realized. The introduction of residential units such as apartments, live/work units and other facilities that serve visitors ensured that density of the community increased. With this increase in residential units, also came an increasingly balanced proportion of space dedicated to housing and space dedicated to jobs/work per area. A new live/work community was introduced to many neighborhoods, and by reducing the distance between employees’ housing and their jobs, vehicle dependency was reduced, leading to cleaner air in these districts. Architectural preservation was also accomplished.

The goals of the program were to “ ...improve quality of life, revive neighbourhoods, enhance economic growth, empower community action and involvement, maintain heritage assets, reduce resource consumption, avoid negative environmental impacts,

avoid urban sprawl, maintain cultural heritage and accommodate human needs and aspirations...

”[19]

When faced with the results of the program, it was seen that economic growth of the revitalized neighborhoods actually superseded the calculated expectations, with property values going up due to high demand, and reductions in vacancy rates. One-bedroom residential units saw a 135% increase in land rates, while the entirety of Downtown Centre property increased by 43.55% over the 7 years of redevelopment.

The program succeeded in meeting other, less directly tangible objectives - community involvement was increased in the revitalisation of the neighborhoods, and residents confirmed an improved quality of life, while it was observed that negative environmental impact was reduced. Revitalisation also introduced new types of developments - mixed income housing opportunities, as well as different types of venues - food and beverage, cultural, retail, and entertainment - that brightened community life, introducing people to more engaging ‘third places’ .

Table 1.2 The criteria and goals established by the program in order to achieve a certain level of sustainability in the revitalization of downtown LA.

[20]

Oregon’s Jean Vollum Natural Capital Center

Located in Portland, Oregon, the Jean Vollum Natural Capital Center was reused from a warehouse of historic importance, built in 1895, into a mixed-use structure, hosting functions of offices and retail.

The project has been noted to be “reflective of the renewed emphasis in the U.S. toward energy and resource conservation, ” and cost $12.5 million for the redevelopment. The district in which this building is located is in a part of the Pearl District. Although the district is booming now, it once stood as a “deteriorating district of rail yards and warehouses.

”[21]

The reason the two-storey warehouse property, was eventually chosen by the redeveloper, Ecotrust, was due to its strategic location in the district - it had close access to bike trails, public transit, and a large expanse of space, upwards of 50,000 square feet in a historic building. Redeveloping it would preserve the outward facade of historic importance, while also introducing activities that would bring the community together in new ways, generate revenue, all at an easily bikeable distance, and reachable by cheap, environmentally friendly public transit.

The architects hired to design the adaptive reuse of the warehouse were Holst Architecture, in consultancy with Green Building Services, to achieve LEED, and development was completed by 2001. By 2002, the now-Vollum Center became one of the first buildings in Western USA to obtain a Gold LEED rating. Sustainable implementations in the building consisted of conservation of water and energy, as well as cutting down on waste by recycling. The reuse of an existing structure, of course, is not to be overlooked, either.

The failings of the warehouse at its time of initiation into reuse were, namely, settling, dry rot, and a lack of seismic reinforcement. [22] Since the design by Holst required an exposed interior, the challenges of slight structural change and of considerable seismic reinforcement amounted to being the most costly portion of the project, rounding up to almost 1/6th of the entire budget. The exposed interior of Holst was part of a four-headed design approach towards sustainability, consisting of:

1. increasing social equity in the district, 2. Conserving water, 3. Letting in light, and 4. Refined air.

In order to accomplish these goals, one of the main design features was to introduce an atrium. This, among other large spaces in the warehouse, allowed for gathering spaces that were open to the public. The design team also used photocell sensors, which helped control interior lighting, by adjusting the artificial lighting in response to what the sensors received from the daylit atrium and skylights. The west facade was also altered to include new glazing, allowing more daylight to enter through and reduce electrical energy use in the structure.

The goal of conservation of water was achieved by designing the ecoroof in the building, and bioswales on site. These act as drainage for stormwater runoff, which can then be treated elsewhere on site before it is used for washing within the building. This results in 95% reclamation of the runoff.

Additionally, the construction team - despite its additional construction (which was still built with thoughtful choice of either dematerialization, or sustainable material) managed to recycle 98% of debris, easily clinching the LEED requirement.

The center now has multiple stakeholders - retail functions, official spaces, as well as nonprofit tenants, all of who are focused on increasing equity in the district, as well as improving the environment.

Georgia’s Stacks Cotton Mill

Located in Atlanta, this complex of cotton mills was constructed in the 1880s and initially focused on only cotton production. As years went on and technologies and markets shifted - especially during the World Wars - the mills shifted some of their production to that of paper bags, canvas goods, and other items, instead. It was finally closed down in the 1970s, and bought in 1996 to be initiated into redevelopment.

Part of the complex of mills was transformed into the ‘Fulton Cotton Mill Lofts’ , with redevelopment initiated in 1997, while another portion of the complex was transformed into ‘The Stacks’ in the early 2000s, as for-sale condominiums. The architects of the redevelopment were Jova Daniels Busby Inc., and the redevelopment cost a total of $50 million. [23] Part of the budget was funded by low income tax credits, due to the percentage of residential units that are allotted to lower income workers.

Some of the major issues faced by the designer and construction teams were the weather exposure that the structures had gone through; the structural timber had rotted, as water had entered the buildings, not to mention the copious amounts of damage due to fires and vandalism.

Since the complex was on the National Historic Register (due to it being one of the only standing buildings of Atlanta’s initial industrial typology of architectural design), the teams had to put in extra work with the redevelopment - the original materials, including fenestration, finishings and skylights, had to be either repaired, reused or replaced with extremely similar options, so as to preserve the heritage and identity of the complex.

[24] As such, progress on the project was done very strategically and carefully, the teams working on redevelopment a portion at a time on the building, removing old materials safely where needed and bringing in new materials and applying with precision. Walls were braced with cranes while removal and replacement of structural elements occurred - ranging from beams to columns, and even entire parts of floor slabs.

Residents of the Lofts and the Stacks both express satisfaction with their housing and location, as well as with the community that has formed over the years in the now-residential complexes, praising its diversity.

In general, it can be seen that industrial buildings are a prime choice for cross-use adaptive reuse, as they provide a wide array of design possibilities. This is due in part to the vast and strong structure of this typology - the span of the columns, and large windows, namely, can give interiors that are large, expansive and naturally lit. There is also the fact that factories, mills and the like are all built to be durable, with load stresses of many times the amount of load that other buildings experience, making it convenient to check and surpass building code requirements. With an ongoing trend of exposed systems/ceilings and so forth, the already-exposed structures

of industrial buildings save further on cost, apart from the usual savings for any adaptive reuse project due to lack of construction of foundations and so forth.

Iowa’s Redeveloping Elementary & Middle Schools

Council Bluffs, IA, home to the Kirn school, is making strategic plans to initiate redevelopment of the building.

By retaining the structure, while taking down non-load bearing walls and creating new partitions, as well as upgrading different building systems, Council Bluffs intends to improve:

● Security and safety, ● Accessibility, ● Energy efficiency, and ● The learning environment of the school itself.

[25]

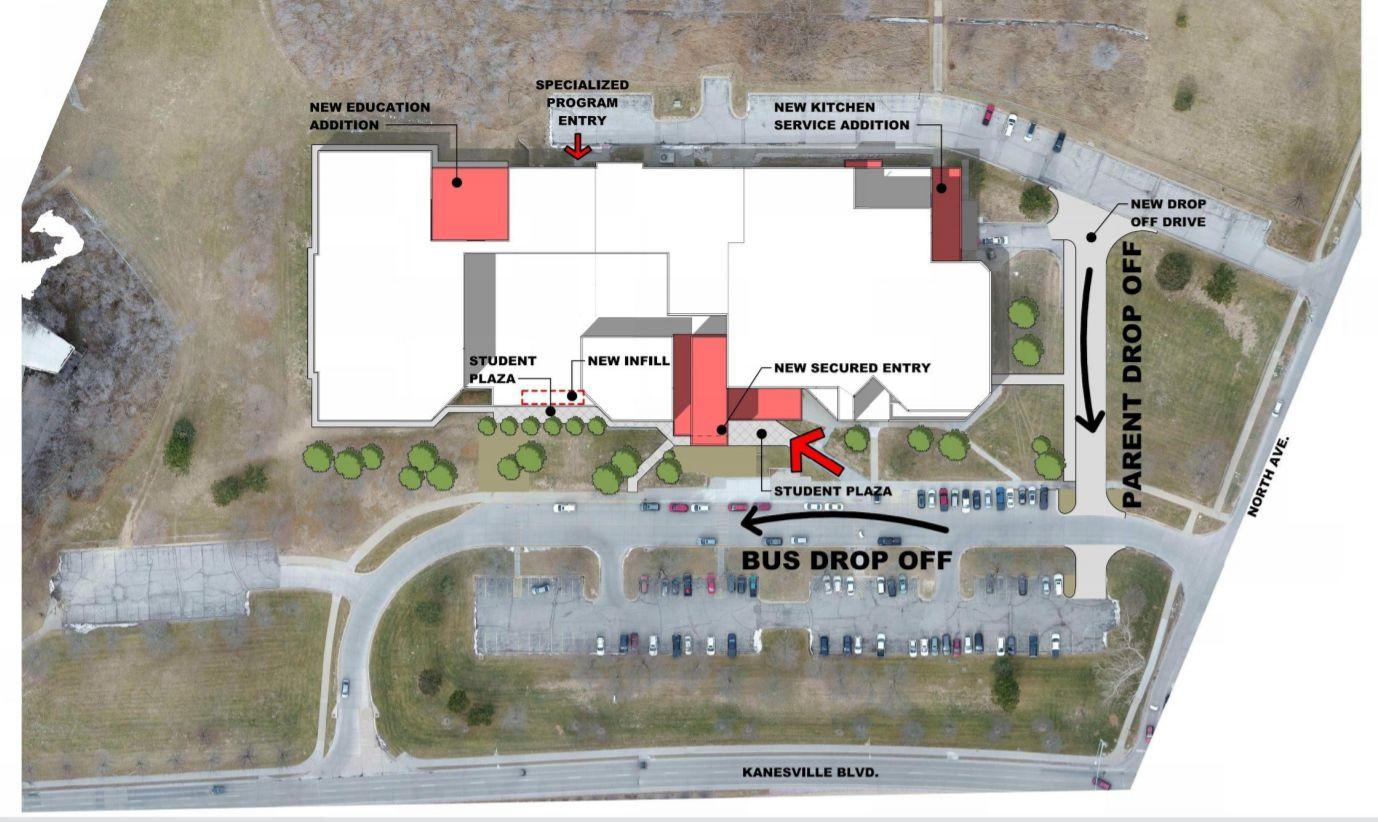

Fig 1.2 The Kirn Middle School first floor plan with additions, system updates, as well an infill development, are highlighted.[26]

The school will reorient its interior in order to direct vision clearly from the main entry points onwards, adding tiers of security as the users progress through the space, with new vestibules introduced between zones. Signage will also be improved, to ease accessibility for all users, regardless of whether they are orienting themselves towards the teacher’s offices, classrooms, or restrooms.

Kirn school had a common complaint by users about a set of steps in front of the school’s facade that served as a barrier instead of an access point to the main entry. Therefore, relocation of the main entry is planned, as well as an improvement of drop off zones, to allow for accessibility and traffic towards the entry and exits.

Fig. 1.3 The reconfigured drop-off zones, as well as an additional zone, is shown on this site plan.[27]

Mechanical, plumbing and electrical systems will be upgraded, improved and replaced where needed. The lighting system will also be completely revamped, consisting mainly of LED fixtures. Windows and doors will also be replaced.

Moving onto improvement plans for the learning and teaching experience for students and teachers alike, natural daylight will be added wherever possible, possibly by adding windows. Enlarging classrooms and other reconfiguration of spaces may allow for greater surface area to introduce windows on. The auditorium and lecture halls will have new partitions/changes that allow for flexible, creative and interesting learning spaces.

The city council is taking in feedback and community participation from teachers, students and parents alike, making sure that all parties will be satisfied and benefit from the outcome. There is social media outreach for the program on Twitter and Facebook with updates, ensuring transparency and encouraging questions and suggestions.

Rhode Island’s Providence Arcade

The Providence Arcade, built in 1828, was the United States’ first indoor shopping mall. Inspired by the microapartment trend that began in Europe and Asia and eventually made its way to the American cities of San Francisco, Chicago and Boston, Providence Arcade was bought by Evan Granoff, a developer looking to popularise this lifestyle to downtown Providence, Rhode Island.

The designers assigned to the project were Northeast Collaborative Architects, and renovation began in 2008, to finish in 2013.

One of the challenges faced by both designer and construction teams, was the fact that the construction methods and structural systems were extremely outdated. (“They just laid down some flat rocks and started building on top of those—that was the foundation. ”[28]) Being originally built two centuries prior, it took time and carefully thought strategy to maneuver through the difficulties that the building presented them with.

Firstly, the building had settled greatly, so walls had to be supported and reinforced, which then resulted in uneven contours. This led to the manufacture of bespoke doors and windows to fit the contours.

For the interior spaces, however, the floor finishings and balustrades were left in place, and the retail zones on the ground floor were retained. This allows for retail businesses to run on the ground floor, while 38 apartment spaces take up the upper storeys. The smaller apartments include bedrooms, kitchen, bathroom and storage amenities. There are also a number of larger apartments, a communal game room and a communal laundry area.[29] The pictures below show the state of the Providence Arcade originally as well as today.

Fig. 1.4 The original Providence Arcade.[30] Fig. 1.5 The Providence Arcade today.[31]

In order to keep the privacy and quiet of the apartments, the ground floor dedicated to the retail area is acoustically partitioned off from the upper floors by bay windows, stopping sound from drifting upwards.

At a total of $7M for redevelopment, the project is regarded a success as the historic structure is preserved, with the apartment clientele being mainly recent university students or graduates looking for an affordable, independent space.

Ontario’s Tower Automotive Building

The Tower Automotive building, over 100 years old, and one of the landmarks of the Toronto skyline, shut down in 2006. [32] Originally designed by Woodman and Turner, and completing construction in 1920, the Tower Automotive was one of the first structure in Toronto which implemented flat slabs with mushroom columns - the latter of which lent design and structural integrity to the building.

After closing down in 2006, the building status began to wear away, with vandalism occurring with more frequency across its site and surfaces. Still, it became a popular spot with photographers, and the artist community put up temporary installations. Its significance as a typology and one of the unique characteristics of the neighborhood’s identity remained despite its abandonment.

Fig 1.6 The figure above shows the Tower Automotive Building after shutdown, before its redevelopment.[33]

The building got advocacy from the government, since it is an important building of significant heritage; the minister of Canadian heritage, Mélanie Joly, encouraged interest in the building. Once the Museum of Canadian Arts mentioned their plan to relocate to Tower Automotive in 2015, Joly mentioned that investing in such a move, in the development of the abandoned building into the MCA, would help increase employment, while spreading influence and opportunity for local artists in the community. The government then went on to fund the redevelopment, providing more than $5 million for the project.

The architects for the redevelopment were architectsAlliance. Their design strategy was to reveal the original structure of the building, with subtle interventions that would reinvent the use of the space, but not the space itself. “Our goal, ” the firm said, “Was to

preserve the rawness of the space as we first encountered it: the honesty of a functional, industrial space, with its patina of history and use both cherished and enshrined.

”[34]

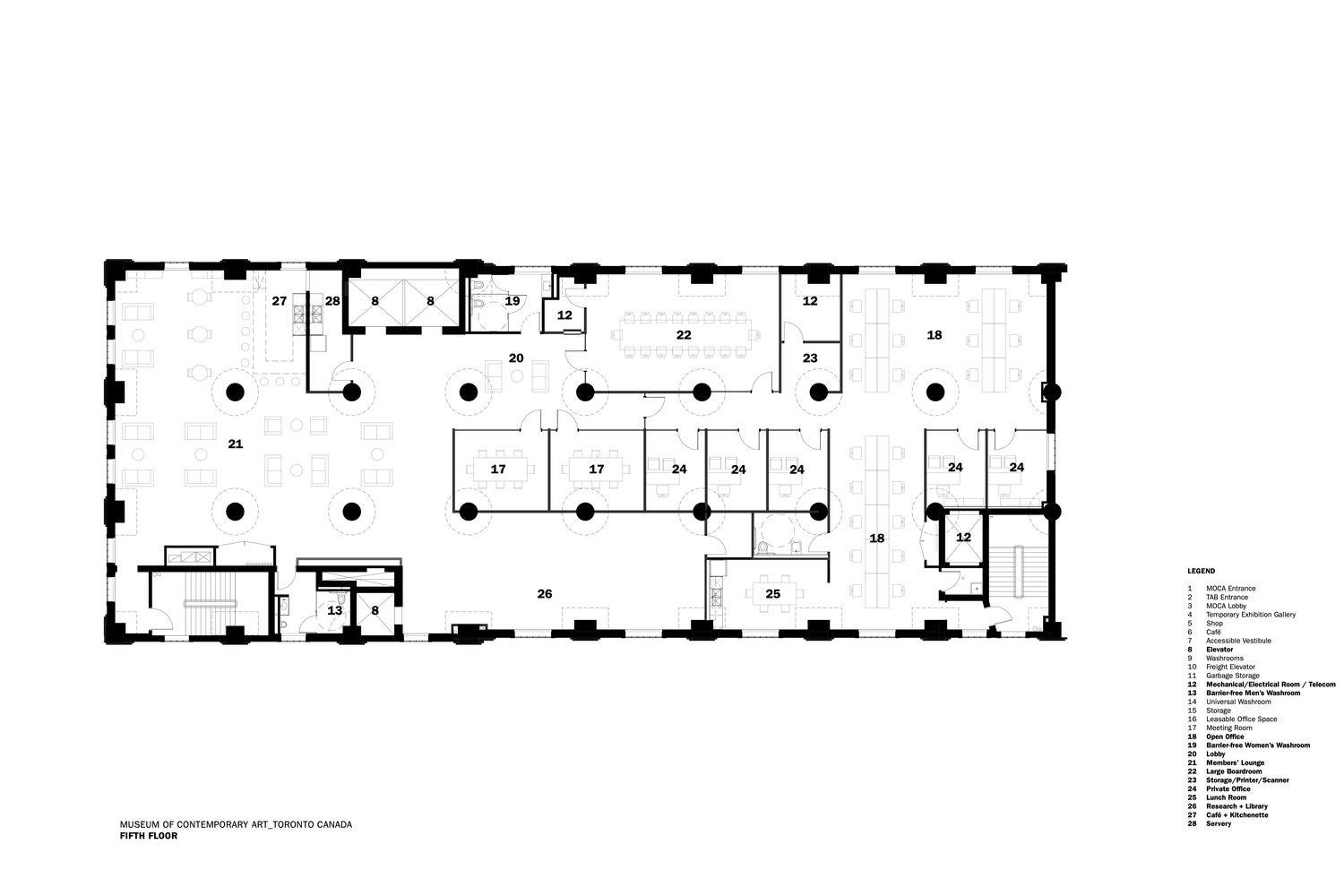

Fig 1.6 The plan of the fifth floor of MOCA, showing the respect paid towards the columns, and the partitions that direct circulation throughout the space.[35]

The MCA now hosts a public meeting hall, temporary spaces, as well as longer-period exhibition halls, workshops, offices and libraries across the first five floors of the building. The other five storeys are home to computer based design and assorted creative pursuits.

Fig 1.7 Section through the Tower, showing the different uses throughout the floors [36]

However, apart from the interior, the building’s exterior had to be restored as well. For this, ERA led restoration, and worked together with architectsAlliance to make sure all interior and exterior design decisions were not only in sync with each other, but also with the building’s original identity itself. As a result, the columns were not only retained but also highlighted. ERA added new thermal windows, refurbished the ground floor doors, and repaired the masonry to a large extent.

[37]

Fig 1.7 Showing the exterior of the MCA.[38] Fig 1.8 Showing the MCA interior.[39]

Washington’s Railroad Station-turned-Courthouse

Fig 1.9 The Tacoma Courthouse, housed in the old Union Station building. Photographed by Loco Steve.

The advantage of adaptive reuse with respect to new courthouses is that the government does not necessarily need to fund the construction of a new building. Any disused building that fits requirements for a courthouse can be redeveloped into its new use. The cuts down on possibly hundreds of millions of dollars. The public can also benefit from the reuse - depending on locality of the original building, it could enable close, pedestrian access for the public

In addition, reusing an abandoned building - perhaps in the slower parts of downtown would mean the revitalization of the area downtown; a courthouse would not only attract foot traffic, but also potential business opportunities. Lawyers, judges, the public who stay at courthouses for long hours during the day would require food, beverage and basic amenities in case of emergency at such a large institution. The creation or revival of such businesses would propagate a positive ripple effect for the rest of the neighborhood.

An example of such adaptive reuse is the Union Station railway terminal in Tacoma, Washington. The Union Passenger station opened in 1911 but became gradually abandoned and finally fell into total disuse by 1984. Meanwhile, in the later half of the 1980s, Tacoma’s court needed to expand beyond its facilities at the time. The court eventually leased the station in the 1990s.

There were not many structural issues faced in the redevelopment, as the building had less than a decade to deteriorate before it was reused. The rotunda was renovated into

courtrooms, chambers and offices. A 3-storey extension on the station was built, but great care was taken to design it in such a way that the aesthetic was complementary to the original station. The extension hosts additional courtrooms, chambers, offices, as well as detention facilities

The results of the reuse were overwhelmingly positive: the court managed to save from its budget due to lack of need for construction of a completely new building. The community has also benefited from its revitalization, as it revived the downtown area of Tacoma. Not only is the courthouse Tacoma’s 12th most popular tourist site,

[40] but museums have also cropped up around it because of the increased traffic to the area, and because of the fulfillment of the need for more institutionally cultural sites downtown.

Texas, home to the largest single-storey public library in the USA

The trend of discount stores expanding and relocating to larger buildings leaves their original, smaller building empty and disused. This usually does not only visually interrupt the scene with gradual decay and vandalism, but it also socially interrupts the fabric of the community, with such spaces often beginning to attract criminal activity.

An issue with such large properties, despite being sold at reduced rates, is that they are still too expensive for buyers; boxy lots used for grocery stores and old supermarkets usually end up being bought (if they are bought) by hospitals, for in or outpatient centers.

[41]

Fig 1.10 The McAllen Public Library, previously a Walmart, in McAllen, Texas.[42]

However, in McAllen, Texas, an abandoned Walmart was instead retrofitted into a library. Due to the considerable volume of the structure, and its large, open spaces, the McAllen Main Library has become the biggest single-storey public library in the USA.

No specific challenges seem to have arisen - the vast “big box” seemed, instead, to only provide the architects, MSR, with opportunities.

The changes the library went through were mostly related to its interior design: removing the finishes of the walls and ceiling; painting over the structures; adding glazes to ensure daylit spaces; and brightly-colored details to add dynamism into the space.

The spaces are designed with the different user groups in mind - for example, teens have a lounge of their own, which has walls that are acoustically treated.

[43]

The library now houses computer labs for different users - adults, teenagers and children - as well as an auditorium for seminar and public events, an art gallery, a bookstore selling secondhand books, as well as the quintessential cafe.