6 minute read

Precedents: Asia

ASIA

Yemen’s Tower House Reuse

Advertisement

Once Sana’a became a UNESCO heritage site, adaptive reuse and conservation have become more popular, among both government and private bodies. However, government bodies are not sufficiently funded, and can only take on a handful of projects at a time with no guarantee of fast, efficient completion. In contrast, private ownership sees more successful, speedy activity.

Private ownership adaptive reuse has a variety of outcomes, given that each project’s reuse function, aesthetic and reparation methods rely solely on the owner themselves and therefore differ from case to case. The government’s jurisdiction in private adaptive reuse only extends towards approval of reuse and control over the conservation portion of reuse.

The government has issued an official manual of guidance on conservation methods and strategies to apply; it is not widely spread, however, so private owners do not use or refer to it (except for some very basic rulings), and there is no enforced penalty for not following the manual to push private owners towards using it more.

As such, private owners have their own to reuse their tower houses, either by:

● Completely reusing all floors, or ● Only reusing the ground floor.

Popular choices for the reuse function are:

● Art galleries, hotels, and/or cultural houses (in case the whole tower house is being rehabilitated), or ● Grocery stores, or other service/facility-providing spaces (in case only the ground floor is being reused).

One of the basic rulings previously mentioned that private owners make attempts to follow is the conservation of the house’s exterior facade. However, it is not always followed; more and more private owners are going about reparation and material replacement according to their own tastes. This has resulted in a merging of the new and eccentric, with the old architectural traditions. The trend is not looked at kindly by many, but it is possible to view this change as the emergence of a new culture, brought on by new context and circumstances, and an eclectic aesthetic.

The precedent looked at in Yemen is a tower house turned hotel, named Dawood Hotel. It faces a plantation garden and is six storeys high.

Fig 1.14 Street view of the Dawood Hotel now that it’s successfully adaptively reused.[55]

Before any design or other work of consideration could take place, an analysis of both the building and the site must be carried out. The reason for this careful observation is to better understand to what extent the building is able to be reused, and what function would fit the reuse best. Previous successful precedents are also presented by CATS (Center for Architectural Training and Research Studies).

As such, the analyses are shown as below:

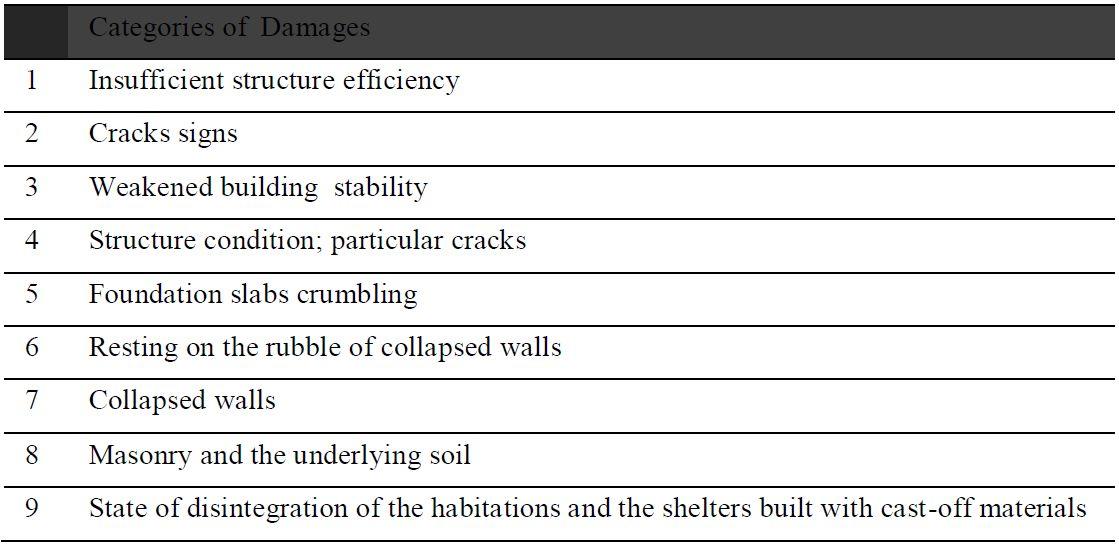

Table 1.5 Categories of damages of the tower houses in the old city of Sana’a (1984).[56]

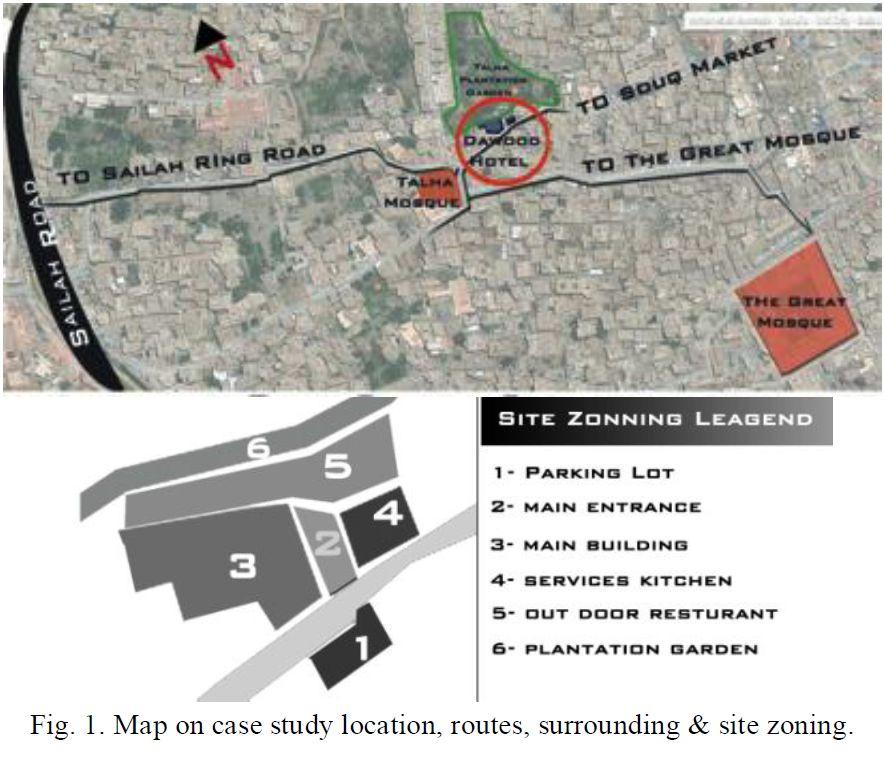

Fig 1.15 Map on the case study location, routes, surroundings, and site zoning.[57]

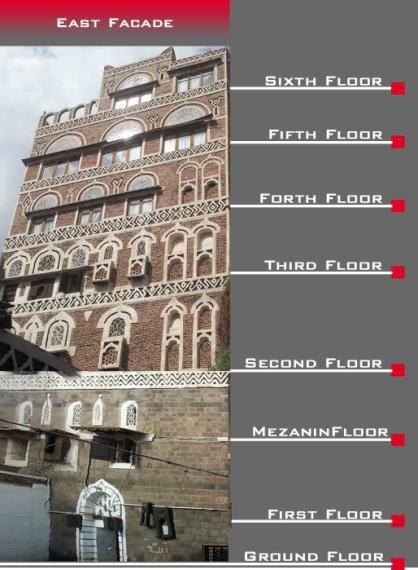

The analysis of the building showed that the building had been undergoing continual upgrades through different decades, with its origin dating back to 250 years. The first 2 floors seem to be the original building, with the rest of the floors being added within the past 30 years.

Fig 1.16 Pointing out the different levels that make up the building.[58]

The reused Dawood hotel has many additions today - more than before, with additional toilets constructed on every floor. The intereios have gone through 2 changes:

1. Original space have remained untouched, and were only given new functions, or

2. Spaces have been redistributed to new functions, with new partition walls.

Today, Dawood Hotel sees tourist and commercial success.

Overall, despite the lack of government supervision and identity conservation, these reuses are first and foremost enabling hard-put families a source of income, as well as generating jobs and creating a new kind of architectural culture, which can all be recognized as positive results.

Jordan, Electricity to Art

Amman’s Electricity Hangar of the 1930s was adaptively reused in 2010, in a move to allow for more inclusive public spaces in the city, with less negative environmental impact.

Figure 1.17 The Hangar before renovation. Photographed by Rami Daher.

The designers, a local firm called Turath, focused on clearing the space as mucha s possible with little to no additional overt interventions. With the structural systems clear in view and walls painted over in white, the focus of the new usage of this space is maximum flexibility for a range of public, art-related events.

The facade of the building, on the other hand, has been remade of glass, ensuring total transparency and allowing both outsiders and users inside the building to visually connect. The transparency also allows for the Hangar to glow at night like a ‘temple of electricity’ .

[59]

Fig 1.18 The renovated Hangar in the day and at night. Photographed by Rami Daher.

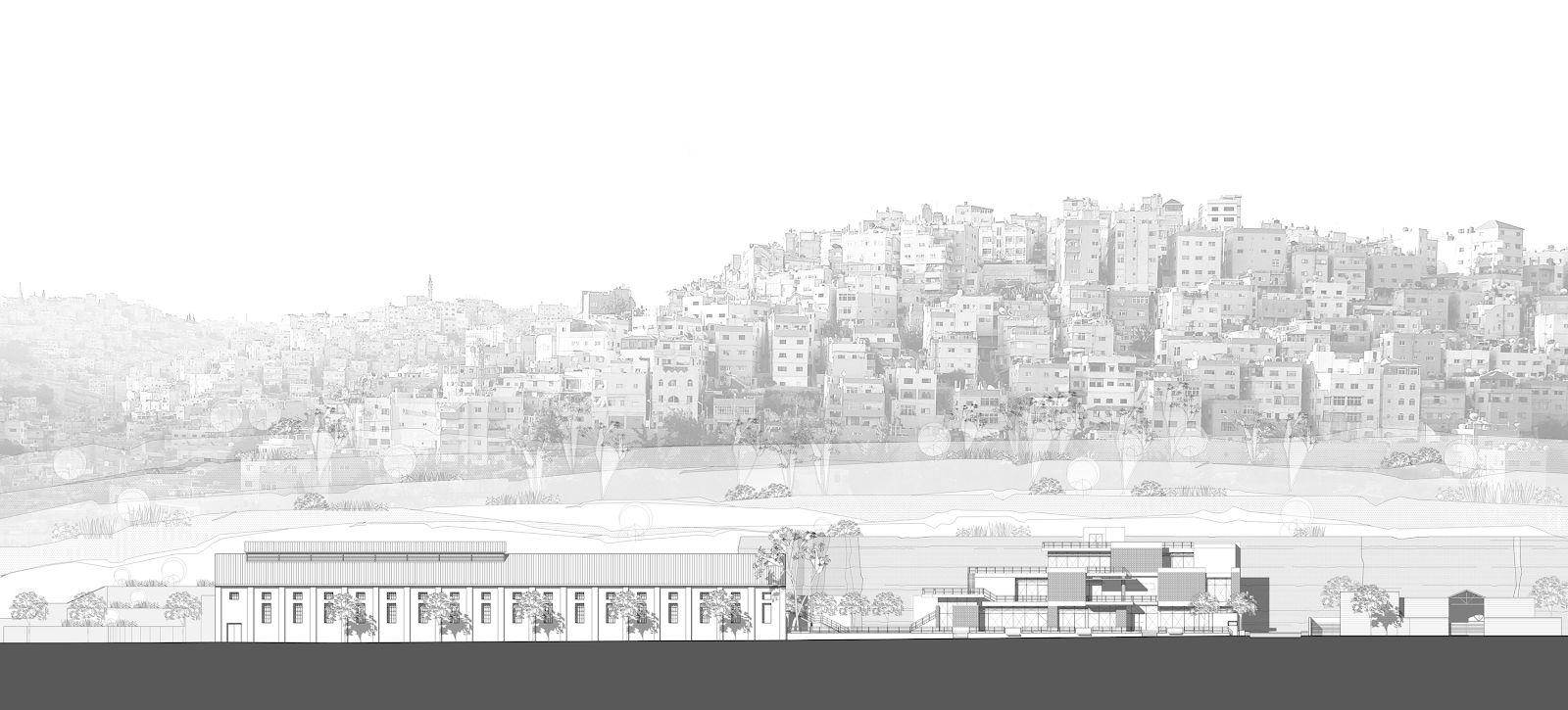

There is also an additional building built upon an infill development, as a complementary structure to the Hangar: where the Hangar has events only, the new building, Ras al Ein Gallery, hosts workshops and lectures on art.

Fig 1.19 Elevation drawing of both buildings with context.[60]

Fig 1.20 Street view photograph showing both buildings. Photographed by Rami Daher.

The project has had a positive outcome so far, with popular talks and events that have been covered by national media in appreciative light. It has given an engaging and inclusive ‘third place’ to an otherwise densely packed residential area. It has also reduced the harmful environmental effects of the building that used to be in the plot before Ras al Ein, by treating the land and building over it.

Palestine, Khan al Wakalah Restoration and Reuse

The Khan of Nablus, built in the 17th century, was essentially an urban warehouse at the edge of the city souq. It included stables, its own bazaar, and, on the upper floors, housing spaces for travelers and merchants - usually they were on their way from Damascus, going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Madinah, or Makkah.

Fig 1.21 A picture of the Khaan before it deteriorated. Here is the courtyard with merchants’ rides roaming.[61]

The Khan has since deteriorated with age, with only the main facade still standing. The facade - before renovation - hosted several small shops that had no structural connection to the Khaan itself.

Once the EU, UNESCO and the Municipality of Nablus agreed to restore the Khan in 2000, a local university was chosen to coordinate the rehabilitation with the parties involved. Apart from restoration, the goals were to add new functions to the original uses: a restaurant, civic hall, museum, a hotel, and shops and offices for commercial use.

Fig 1.22 The photograph shows the main facade before renovation, as the only facade still standing.[62]

The design of a new courtyard and the interior detailed design of doors, windows, and flooring was assigned to Davide Pagliarini, an Italian architect, who introduced a touch of contemporary by replacing the dilapidated gates with sleek new dark iron gates, which contrasted with the cool-toned cream shades of Nablus stone. The shops have also been renovated.

[63]

Totaling to a budget of €2.5 million[64] , this restoration and reuse has most definitely achieved positive outcomes. A ‘yard school’ had been established during the period of renovation, training youth in the art of Nablus stonework and other handicrafts (Nablus’ famous olive oil soap, traditional embroidery) used to help restore the Khaan and set it up for business.

Popularity, tourism and cultural service provision have led to the project’s success, encouraging the neighborhood’s economic and social growth for the community.

Fig 1.23 A view of the renovated Khaan Al Wakalah, from the restaurant’s vantage point.[65]