11 minute read

HC1.1

from W19P325

by PDF Uploads

HC1.1: Create affordable and high density housing

Context

This policy responds to the GLA’s agenda around increase housebuilding and density. It also responds to local community groups such as GIbbs Green tenants association who called for high levels of affordable housing. This demand has been balanced with financial viabilty, proposing 40% affordable housing, which is still higher than the GLA’s policy of 35%.

Desired Outcome

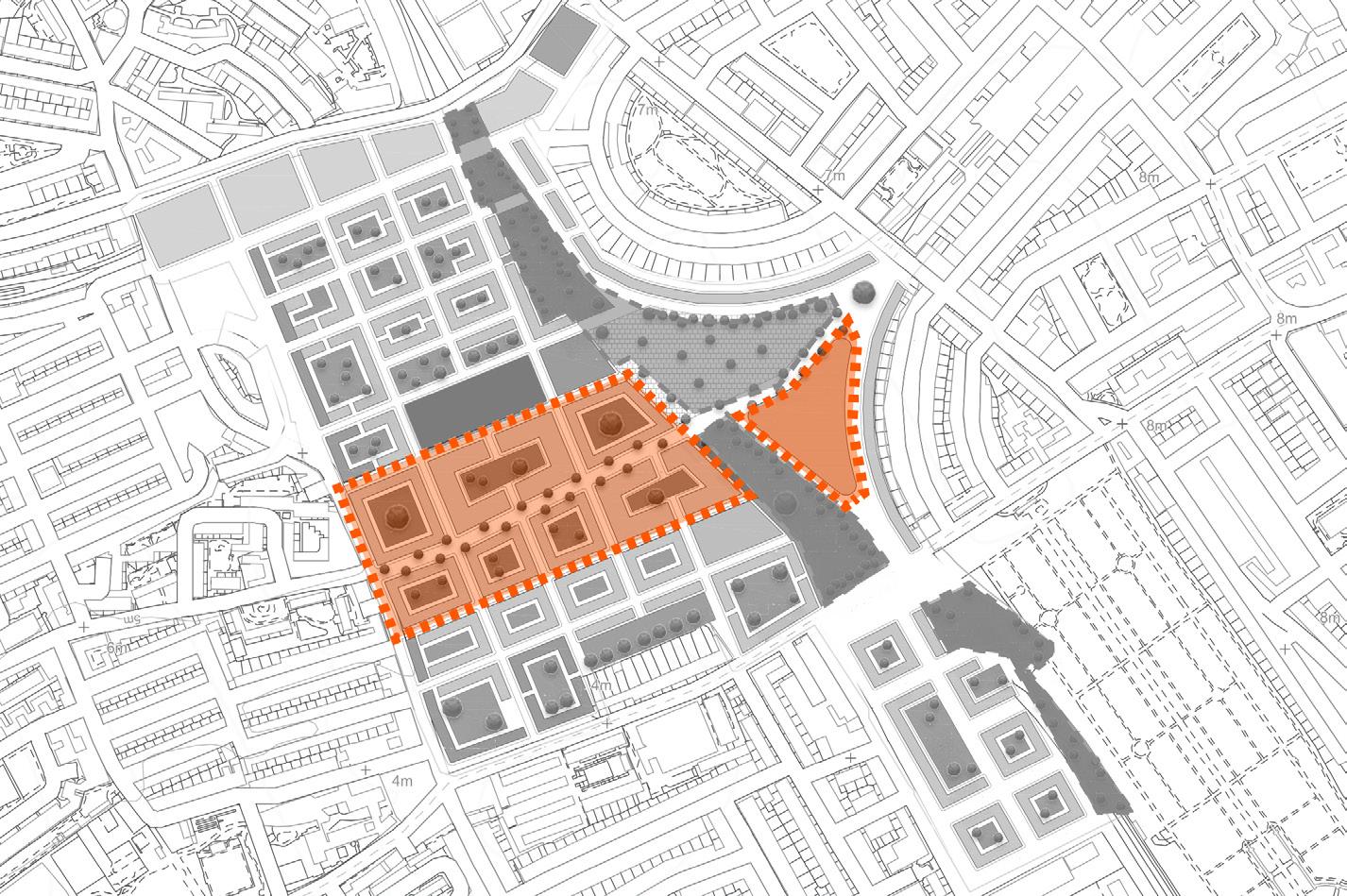

To create affordable and high density residential housing, providing a range of tenures, including 30% privately owned market-value units, 30% shared ownership, 80% of market-value, 35% social rent (managed by a housing association; rent valued at 33% of individual’s income.), 5% assisted housing. There will be a range of units available, from studio flats up to 3 bedroom family apartments. These will be complemented by assited housing units for elderly and vulnerable residents. Housing will be designed and developed through meaningful consultation and social units will be allocated through a means assessment in partnership between the local authority and the housing association. Housing will have a density of 300 dwellings per hectare in line with the GLA’s (2019) policy 3.4 on optimising housing potential in the draft new London Plan.

Policy Tools

This policy combines formal guidance, incentive and control tools as well as informal tools such as design guides to influence development. A development brief will be expected from local authority which sets out the desired outcome of this policy prior to submission of planning application. An urban design framework tool will also be proposed to ensure housing meets the required density standards and suitable layout. This will be complemented by guidance policy from the GLA’s new London Plan around affordable housing provision and density.

Formal tools Guidance

• GLA Policy H7 Affordable housing tenure • GLA policy 3.4 Optimising Housing Potential • Earl’s Court Urban Design framework

Incentive – LA support to developer in establishing partnership with housing association. GLA partfunding for affordable tenure provision. Control – Development brief, planning consent Informal tools

Negotiation between local authority and developer in achieving desirable outcomes

CABE Design report – Better Neighbourhoods: Making higher densities work Case study: Woodberry Down scheme

Case Study - Woodbery Down Regeneration

The Woodbery Down Regeneration-Desired objectives London Woodberry Down is a 30 year RICS award-winning regeneration project in North London. The existing 42 residential blocks had fallen into disrepair and required redevelopment. So far 1,479 new homes (of which 736 are affordable) and 6.61 acres of public green space have been delivered. The site includes two schools, retail space and a community centre. The “tenure split” for a revised masterplan approved in 2014 was for 43 per cent of the project’s homes over forthcoming phases to be “affordable”, with 47 per cent of those to be let at social rent levels and 53 per cent for intermediate shared ownership. The Woodbery Down Regeneration-Tools used

It required a development brief tool with the expectation of a partnership between the council, commercial developer Berkeley Homes, the Notting Hill Genesis housing association, the Manor House Development Trust and the resident-led Woodberry Down Community Organisation. The local authority also developed an urban design framework which ensured the appropriate levels of density, tenure mix and layout was achieved. The two tools together were effective in meeting the desired outcomes due to strong partnership working with shared goals and good consultation methods, guided by clear guidance. (see Berkeley Homes Case Study, 2018)

HC1.1: Create affordable and high density housing

Transferability

The scale of the Woodberry Down development is similar to Earl’s Court (5,000 homes) making this caser study very relevant. The Woodberry Down scheme also involved rehousing residents on site without any displacement and was able to secure a high level of affordable housing. The use of a development brief and urban design framework was effective and is highly applicable to Earl’s Court. One challenge in Earl’s Court will be whether a partnership of this strength can be achieved, considering a previous breakdown in communication between the join local authorities.

Limitation

The developer may argue that providing high levels of shared ownership and social rent is not financially viable, however the Woodberry Down case study proves this is possible. The Woodberry Down case study provides a good example of a sustainable neighbourhood in accounting for all pillars of sustainability. The extent to which an urban design framework and criteria for social housing is adhered to is subject to developer negotiations which historically have been problematic for the influence of the original SPD.

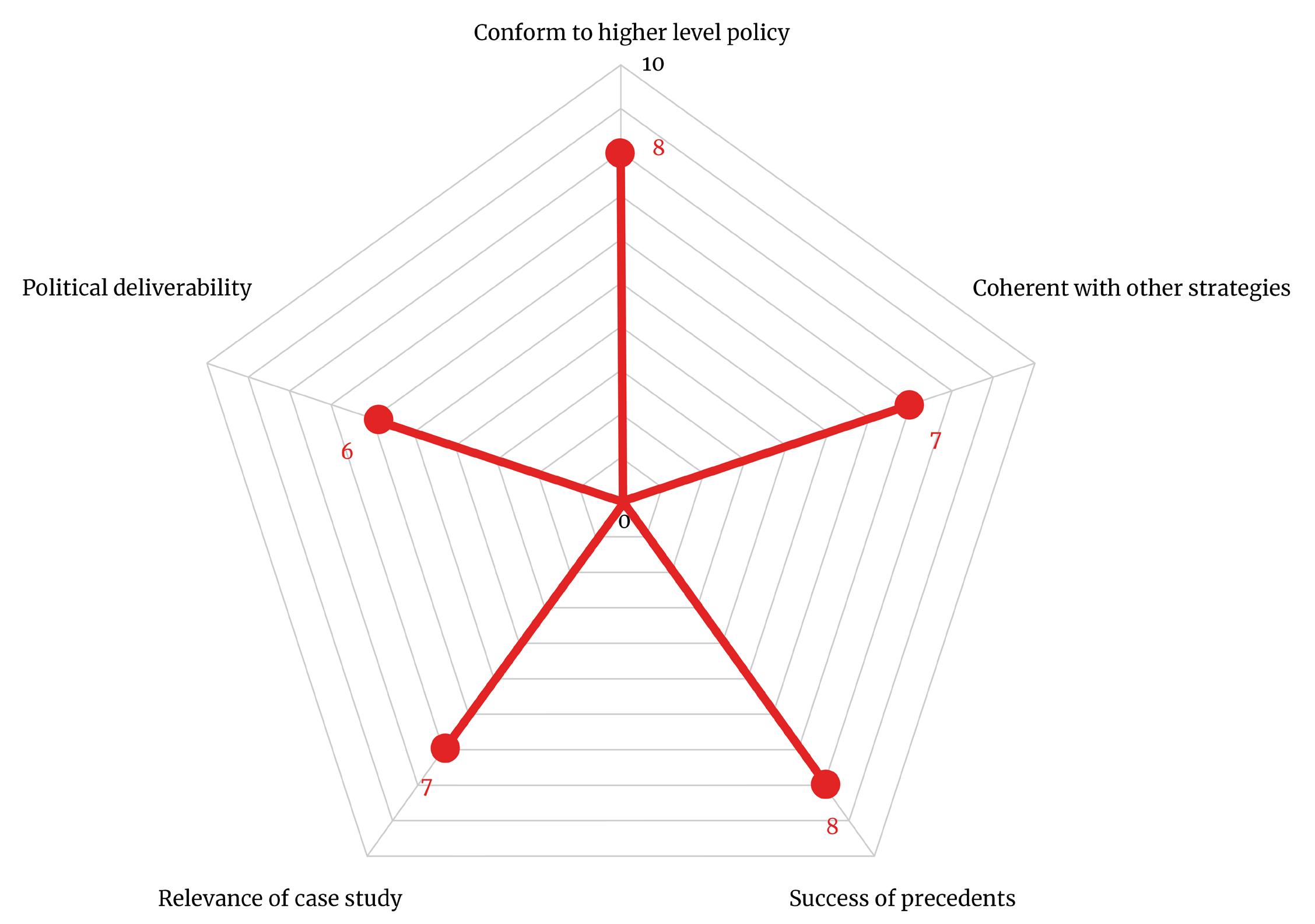

Overall chance of success: 76%

This policy can be successfully implemented only through the delivery of a development brief, urban design framework and a meaningful consultation process which ensures that the voice of the residents is heard. and the planning authorities take these into consideration when setting out a masterplan. Assurance from the council, developer and housing association that a just tenure mix will be delivered is key to the success of this policy. Strong partnership working a shared vision will help.

Context

This was a clear policy in the original SPD (ENE1) as well as an important request from local community groups. It has been deemed essential to bring this policy forward into this report as it unpins the objective of designing an environmentally sustainable neighbourhood.

Desired Outcome

Construction materials will be sourced locally where possible and residential units will be well insulated combined with storage heaters and low energy light fittings in line with BREEM standards. The development will have a decentralised district heating system powered by waste from the housing development. This improves energy efficiency by reducing need Formal tools to grid power and reducing the distance be- Informal tools Guidance tween energy source and use. Negotiation between local authority and • GLA Policy H7 Affordable housing tenure An on-site grey water treatment system developer in achieving desirable outcomes • GLA policy 3.4 Optimising Housing Potentialwill manage and recycle used water effi • Earl’s Court Urban Design frameworkciently. Incentive – LA support to developer in establishing CABE Design report – Better Neighbourhoods: partnership with housing association. GLA part Policy Tools - Making higher densities work funding for affordable tenure provision. Control – Development brief, planning consent Case study: Woodberry Down scheme Detailed supplementary guidance around best practice energy-efficiency standards will be expected to be provided by developers in an energy assessment.

Formal tools Guidance

• GLA Policy 5.2 Energy Planning

Incentive – GLA advice and part-funding for district heating-system, forming case study for London Control – provision of energy assessment by developer to receive planning consent Informal tools

CABE report: What makes an eco-town?

BREEM energy standards

Case study: Bioregnional design standards for BedZED

Formal tools Guidance

• Social infrastructure design code in urban design

framework Incentive – LA support to developer in establishing partnership with Better Health who will offer 20% funding Control – Consultation strategy provided by developer Planning consent subject to alignment with policy and Informal tools

Glasshouse engagement resource

Case Study - BedZED

BedZED -Desired objectives BedZED is the UK’s first eco-community, in South London. Environmental measures included reducing energy demand, storage heaters, cavity wall insulation, south facing unit design, energy efficient light fittings, solar power systems on site, waste water recycling system on site and a biomass boiler system. Construction materials were from recycled or sustainable sources. Evaluation by Jan-Carlos (2010) found that although water and energy consumption by residents was lower than national average, the scheme experienced challenges with its biomass boiler and has been powered by a back-up gas boiler since 2005. BedZED -Tools used The local authority used the incentive of selling land to the developer at below market rate to encourage the developer to design and build innovative energy efficient homes. The local authority’s informal tool of advocacy and support for a close partnership between Peabody, environmental consultants Bioregional and architects Zedfactory ensured that the design had environmental integrity. This reduced the scope for design drift when delivered by the developer.

Transferability

The environmental design principles of this case study are transferable to Earl’s Court, however the scale of both developments are very different, making a direct comparison more difficult. The incentive tool used (selling land at a subsidised rate) is problematic for the Earl’s Court opportunity area as the majority of the land is owned by Delancey and APG.

Limitation

The scale of the Earl’s Court development requires a large scale heating system which requires strategic planning. Strong guidance, incentive and control tools are required to ensure developers meet the expecatation considering set-up costs may be higher than conventional alternatives. A business case for sustainable energy provision should be explored by the LPA. Sourcing enough recycled construction material may be difficult for a scheme of this size.

Overall chance of success: 70%

Overall this policy has a reasonable chance of success as long the developer’s energy assessment is satisfactory and they can be trusted to realise the outcomes expected. Close informal support and guidance from the local authority could come in the form of a funded environmental advisor such as Bioregional, thus incentivising the developer to make sound decisions.

Formal tools Informal tools

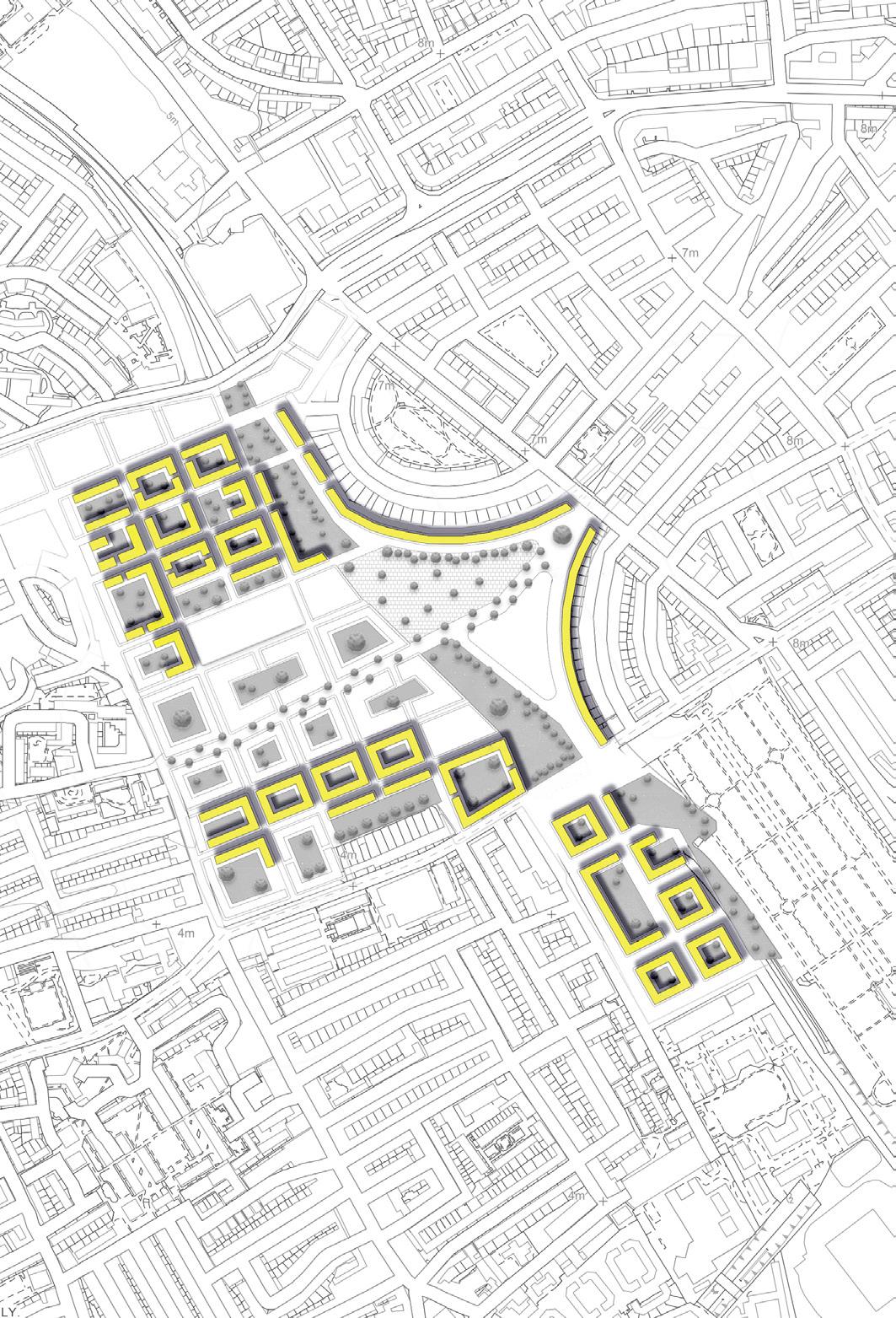

Context Guidance • GLA Policy 5.2 Energy Planning CABE report: What makes an eco-town?Policy Tools The key control tool will be the expectation that developer provide a consultation strategy The consultation informing the original SPD was conducted poor and led to a breakdown of trust between the local authorities and the community about the displacement of people and the amount of new social housing proposed. This policy aims to mitIncentive – GLA advice and part-funding for district heating-system, forming case study for London BREEM energy standards Control – provision of energy assessment by developer to receive planning consent Case study: Bioregnional design standards for BedZED as part of their planning applications. Design code guidance in an urban design framework will be given to ensure the appropriate scale of social infrastructure development. Developers will be incentivised to build health facilities as the local authority will establish a partnership with Better Health who will manage the facility and part-fund the development. igate against the risk of further consulta- Formal tools Informal tools tion being conducted poorly. Guidance Glasshouse engagement resource Developers and housing association partners will meaningfully involve existing residents of Gibbs Green estate and the wide community in a process of consultation which ensure residents are listening and decisions are made which balance the various stakeholder interests. Social infrastructure will be built at the earliest possible period of phasing (whilst remaining viable in terms of meeting appropriate demand). Social infrastructure will be inclusive and affordable, providing a range of services to meet the health and leisure needs of new residents as well as the wider community. Taking the SPD forward, a 16,500 sqm educational facility and 21,750 sqm health facility will be allocated bearing all necessary space standards and ensure they are accessible to people of all backgrounds and ages. An area of 6,740 sqm has been dedicated for community facilities, these are provided to meet the needs of both the boroughs, engage the local population and enhance local culture and spirit. Creation of a high street that connects the two boroughs at the node of the cultural centre will help integrate the two boroughs and provide social value through local retailers. • Social infrastructure design code in urban design

Desired Outcome

framework

Incentive – LA support to developer in establishing partnership with Better Health who will offer 20% funding Control – Consultation strategy provided by developer Planning consent subject to alignment with policy and guidance

Case study: Woodberry Down

Case study: Packington Estate

Case Study - Packington Estate

Considered to be a good example of meaningful engagement in estate regeneration. Chair of the Packington Square resident board states: ‘Consultation from the early stages of the regeneration process, not just with residents but with community members from the surrounding area, was vital in establishing a productive working relationship between the housing provider and the local community.’ Hyde Housing Group – Packington Estate cases study

Packington Estate -Desired objectives Establishment of a resident steering group which has clear accountability and responsibility. Involve and engage residents early in the process ‘Going-to’ the community and engaging harder to reach groups, rather than expecting residents to come to evening meetings. Packington Estate -Tools used

Informal engagement tool of creating a steering group was critical in building buy-in improving communication with residents, complementing any wider formal consultation processes

Transferability

This engagement tool is highly transferable to Earl’s and should be considered in the first instance.

Limitation

Local authorities and developers are often afraid of public consultation as they do not know how to manage conflicting interest.

Overall chance of success: 75%

In order to be successful in building support for the scheme, the developer should instruct an engagement consultant to draft an engagement strategy and deliver the strategy. Well facilitated workshops should be able to resolve conflict and build trust in local residents that new housing will be provided to them. The case studies above should be used when communicating with residents.