TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 3 2026 | VOL. 45 | ISSUE 17

OPINION

Race-blind justice isn’t justice at all PG. 6

OFF THE BOARD

The road to reckoning FEATURE PGS. 8-9 A love letter to ‘Tribune’ haters

PG. 11

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 3 2026 | VOL. 45 | ISSUE 17

Race-blind justice isn’t justice at all PG. 6

The road to reckoning FEATURE PGS. 8-9 A love letter to ‘Tribune’ haters

PG. 11

Josette Chandler Staff Writer

In December 2024, the Legislative Assembly of Alberta passed the Health Statutes Amendment Act, officially known as Bill 26. This act restricts minors’ access to gender-affirming care (GAC), including prescriptions for puberty blockers and hormone therapy. In response, Egale Canada and Skipping Stone initiated litigation against the Government of Alberta over the constitutionality of Bill 26. In June 2025, the Court of King’s Bench of Alberta granted an injunction, effectively pausing Bill 26’s enactment.

In November 2025, the government introduced Bill 9, which used the notwithstanding clause to override the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The injunction was ultimately removed in December 2025. Since then, Trans Rights YEG has created a petition to be brought into the House of Commons. The Tribune outlines how Bill 26 affects trans youth disproportionately, explaining how the petition may reverse the proposed legislation.

What is Bill 26?

Bill 26 is an Alberta law that amends the Provincial Health Agencies Act as well as the Health Professions Act by introducing regulations for new and existing provincial health organizations.

Celeste Trianon, an activist in Montreal known for her documentation and

tracking of anti-trans legislation, considers this law unconstitutional. In a written response to The Tribune , she stated how Bill 26 signals to trans youth that they are second-class citizens in Alberta, and that they do not have the same rights to care as other Albertans.

“It’s simple, they’re constitutionally protected rights!” Trianon wrote in relation to GAC. “This includes the right to life, liberty, and security of the person, to be exempt from cruel and unusual treatment, and to be treated equally under the law. This also includes, for trans youth themselves, to be treated under the principle of the ‘best interests of the child,’ the governing principle of family law across Canada.”

What does Bill 26 do?

Under this bill, minors in Alberta cannot access GAC, including puberty blockers, Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), and gender-affirming surgeries. Trianon insists the ban does long-lasting damage to the minors affected.

“These bans do not protect [trans youth]. Countless instances of research and the Alberta Court of King’s Bench have held that such bans create irreparable harm—up to and including suicide. And in many cases, these consequences are lifelong, both physical and psychological,” Trianon wrote.

According to a study by the Trevor Project, an organization founded in 1998

to aid 2SLGBTQIA+ youth, antitrans legislation— like that limiting access to GAC— increases suicide rates in trans and non-binary youth by 72 per cent. HRT has been found to decrease suicidality by over 67 per cent, showing this form of GAC to be crucial to supporting trans youth—a demographic where close to 49 per cent experience suicidal ideation.

What will the petition do?

With their petition, Trans Rights YEG is attempting to stop the continued implementation of Bill 26. The petition has already reached its goal of 500 signatures, but is still continuing to accept signatures until it is brought before the House of Commons. If successful, it will ensure trans youth in Alberta have access to GAC once again. Anyone who is a resident in Canada can sign the petition.

Trianon joined Trans Rights YEG in

Amelia H. Clark News Editor

On Jan. 19, the Students’ Society of McGill (SSMU) revoked Post Graduate Students’ Society (PGSS) members’ access to the Free Lunches Program. This decision follows PGSS executives opting out of the meal fee, which previously went towards the now-closed Midnight Kitchen (MK), but since closure has gone towards the program. Postgraduates previously paid $2 CAD per student per term, while undergraduates pay $8 CAD.

In a written exchange with The Tribune , the PGSS executive team declined to comment on the motivation behind their decision to suspend the fee or the state of ongoing negotiations.

SSMU President Dymetri Taylor explained in an interview with The Tribune that discussions between the two student societies led to the suspension of the fee, stating that PGSS felt they should have been consulted in the decision to close MK.

According to Taylor, PGSS cited the change in structure from MK to the new Free Lunches Program as their reason for suspending the fee. PGSS executives informed McGill of this decision. In response, the university responded that PGSS executives could not unilaterally decide to opt-out without their members’ say-so. This led to a compromise wherein PGSS would not collect the fee until May

18, when the results of a referendum moving to permanently suspend the meal fee are announced.

“Because there was a reorganization planned for that service, for the provision of meals to be increased and continue to be provided, the SSMU at the time believed that there was no incentive to reach out to PGSS about it. It’s a change of the service, but it’s not a removal of it,” Taylor said.

“So, [the PGSS] had a meeting with the [SSMU] executives, in which case they had a riveting discussion to say the very least. And there was certainly some interesting perspective shared by PGSS regarding Midnight Kitchen and the reorganization, so that has led to them wanting to remove the fee in general.”

Upon learning of PGSS’s final decision to suspend the fee, Taylor put forward a motion during the Jan. 15 Legislative Council meeting to restrict PGSS members’ access to the program and the SSMU food pantry. He stated that it is in the best interest of undergraduate students to stop subsidizing the cost of free lunches without a contribution from PGSS. The motion was passed unanimously. However, SSMU Vice-President (VP) External Seraphina Crema-Black later proposed an amendment to allow PGSS members to retain access to the food pantry until the referendum results are announced.

Crema-Black explained the motivation behind this amendment at the Jan. 20 Board of Directors meeting, stating that

discussions with PGSS SecretaryGeneral Sheheryar Ahmed and SSMU’s inhouse council led her to believe a compromise was reachable.

“I want to know whether that’s something that they would consider before we pull access, especially because it’s used disproportionately by PGSS members, and food insecurity is a very important issue,” Crema-Black said. “I think I will be doing right by the company in my capacity as VP External, knowing that we’ve been talking to PGSS.”

support of this petition. She insists that the passing of this petition is essential to stopping Bill 26’s drastic negative effects. “Kids will die. Families will be split apart. People will suffer. And the consequences will be unquantifiable,” Trianon said. “Few times do governments decide to actively destroy the lives of a few people, but the consequences will certainly be intergenerational.”

An email motion granted the amendment, allowing PGSS members to continue accessing the food pantry for the remainder of the Winter 2026 semester.

Students are now mandated to provide McGill identification proving that they are undergraduates before accessing the Free Lunches Program. If the motion to annul the fee fails, postgraduate students will again have access to these services but will have to pay an $8 CAD per-semester fee in order to match the contributions made by SSMU members.

Taylor told The Tribune that removing PGSS access to the daily free lunches is the required course of action until the referendum, as the program will have less funding due to the executives’ decision to suspend their fee. Without funding from PGSS, the program cannot serve as many students as it does currently.

“[The PGSS executives] believe that it is better that no fee should exist and that their students should not have access to a meal service that’s recurring every day of the week, [...] especially because the PGSS has no plans to institute any food accessible initiatives of their own at the present time,” Taylor said. “And now it’s up to their members to decide what is better, what is worse.”

Eren Atac News Editor

McGill Faculty of Law’s Centre for Human Rights & Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) hosted a workshop titled “Revitalization of Indigenous Justice in the Americas” over Zoom on Thursday, Jan. 29. The event featured three speakers active in Indigenous rights advocacy, including attorney Elizabeth Olvera Vásquez, McGill BCL/JD candidate Tarek Maussili, and Peruvian grassroots organizer Elsa Merma Ccahua.

The event explored the meaning of justice for Indigenous Peoples in the Americas, with a focus on community responsibility, the relationship between land and life, and collective repair. The speakers examined how these concepts exist in the context of marginalization, capitalism, and land dispossession, with an emphasis on current Indigenous efforts to challenge these systems of power.

Vásquez began the discussion by emphasizing the importance of Indigenous communities being familiar with their family origins and history. She explained that, through an understanding of family history, Indigenous people can more effectively integrate into their communities.

“It is important [for Indigenous people] to know that their children are part of the community itself, because they know [their family] background will imply responsibility in a deter-

mined moment,” Vásquez said. “So it is important to know where to find that.”

Maussili continued the talk by criticizing Canadian society’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples, using his childhood as an example of the country’s historic and continuous erasure of Indigenous cultures and identities.

“Being Indigenous in Canada was never a good thing up until 2015 or 2016. I went through high school and I finished around 2015 and I remember being Indigenous was the most horrible experience,” Maussili said. “You’re treated as subhuman. You’re not treated with respect, and this is still the case today. Justice means reclaim-

ing our identities and reclaiming our strength as a people. We’re losing our position in this country as Indigenous people from our respective nations. This is the goal of Canada, to assimilate our people, to dispossess us of our lands.”

He expressed the need for the younger generation of Indigenous people to get involved in activism, stressing the vitality of broader action against Canada’s attitude towards Indigenous rights.

“Getting the youth active is something that I would like to see for our people,” Maussili said. “When I was in Peru, I saw the youth and all the young activists getting involved in protest-

ing against the government and asserting their rights, and that sort of thing is what we need to see here in Canada [....] You can still clearly see that it’s not in Canada’s best interest to assert or to respect Aboriginal rights and titles. The future doesn’t really look good for us if we continue down this path.”

Ccahua spoke next, underlining the central role of land and territory in holding Indigenous communities together in the face of corporate advancement.

“We have been fighting with a mining company for many years,” Ccahua said. “I belong to an impacted and affected community, and we have a very long history. For our people, justice is defending [our] territory, water, and life. We live in a productive community that lives off the [land], and [our people] see those products as capital for their daily living and for supporting their families.”

She concluded the workshop by stressing the role of Indigenous activism as a tool for autonomy against governmental agendas of cultural assimilation.

“In spite of all of the negative [experiences] our communities have gone through, I strongly believe that something that continues to be very present is resistance and the ways of resistance in which communities have found their own political [and] judicial strategies,” Ccahua said. “Why speak about Indigenous justice? It enhances the self-determination and autonomy of Indigenous Peoples.”

Expert panellists warn that Bill 94 affects religious minorities disproportionately

Devdas Hind Contributor

On Jan. 27, Muslim Awareness Week (MAW) hosted a roundtable on the dangers to civil liberties that Bill 94—passed in October 2025—would bring.

Quebec lawmakers allege that Bill 94 is intended to reinforce secularism in the Quebec education system and bring several legislative reforms. The bill requires any worker providing services to students, as well as students themselves, to keep their faces uncovered within public or private institutions, and to refrain from wearing any visible religious symbols. This restriction does not apply to coverings worn for medical reasons or by people with disabilities.

The author of the bill, former education minister for the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) Bernard Drainville, argues that these measures are meant to promote Quebecois and democratic values such as gender equality and a secular state.

The roundtable convened at the Centre communautaire de loisir de la Côte-des-neiges and was composed of three panellists: Ligue des droits et libertés Coordinator Laurence Guénette, Professor of Law at the Université de Québec à Montréal (UQÀM) Ndeye Dieynaba Ndiaye, and UQÀM Political Science Master’s student Nour Amjahdi. The panel was overseen by MAW President and Co-Founder Samira Laouni.

Laouni began by acknowledging the

ninth anniversary of the Jan. 29 mass shooting at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City, emphasizing the importance of fighting Islamophobia. She then introduced the main concern with Bill 94, noting that it excludes Muslim women from working in the public sector, given that many of them choose to wear hijabs for religious and cultural reasons.

“While pushing the fundamental value of gender equality, [the government] is violating the right to work of certain women,” Laouni said. “How can gender equality be achieved without the financial independence of women?”

Laouni then passed the microphone to Guénette, who began with an assessment of the Quebec government’s actions since the Act respecting the laicity of the State (Bill 21) was passed in 2019. She noted that Bill 94 expands the restrictions of Bill 21, and adds to the existing violations of certain marginalized groups’ rights.

“The religious neutrality of the state [is] meant to allow everyone to practice their religion freely without fear of compromising their convictions and with respect to the right to equality,” Guénette stated.

She continued by explaining that the CAQ adopted Bills 21 and 94 despite opposition from several feminist and human rights organizations. She also noted that the restrictions on face coverings in Bill 94 represented flagrant violations of both the Canadian and Quebec Charters of Rights

and Freedoms. Guénette ended by warning that the CAQ’s use of the notwithstanding clause to override constitutional protections should worry everyone in society.

Next, Amjahdi discussed how she was directly impacted by the ban on face coverings.

After Bill 21 was passed, she could no longer teach music as she had intended. More recently, she lost her job leading a children’s choir because of Bill 94.

“It was very violent,” Amjahdi said. “I was quite lost and my life turned upside down. I felt that my identity was shaken. This law put an end to my musical identity.”

Amjahdi explained that, despite being a product of the Quebec francophone school system, she now questions her identity as a Quebecoise. She concluded by calling for allies of the Muslim community to join them in protesting these bills.

Dieynaba Ndiaye, the fourth panellist, discussed the importance of speaking out against constitutional injustices.

“In certain societies [like Quebec], filing grievances has an important moral value. We must do it when rights are violated in Quebec,” Dieynaba Ndiaye affirmed. “We have the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse.”

According to Dieynaba Ndiaye, Bill 94, along with several other pieces of legislation, represents a rupture of this social contract.

“It’s very important [to understand] that people come here with competencies, with experience,” Dieynaba Ndiaye said. “People choose Quebec just as Quebec chooses people.”

*All quotes were translated from French.

Eimaan Ahmed Contributor

In July 2025, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) agreed to a project proposal that permits cohabitation in social housing, allowing unhoused individuals to live with a roommate. However, as of January 2026, this proposal has not yet been implemented.

In response, Québec Solidaire called out the CAQ on Jan. 18 for its inaction on the issue. They cited the CAQ’s inefficiency in fulfilling its commitments to provide housing solutions to counter the shelter crisis.

The city’s homeless shelters are increasingly overoccupied, with many unhoused individuals turning to emergency rooms for shelter. In a written statement to The Tribune, Jayne Malenfant, an assistant professor in the

Department of Integrated Studies in Education, explained how the government could implement homelessness prevention to offset the number of people in need of housing.

“The proposed project would have been a start but it would have just treated the symptoms of the housing crisis rather than the root causes,” Malenfant said. “The provincial and municipal governments have to start considering and implementing rights-based policies that see a home as a right, and not something that people can be pushed out of for the profit of landlords or rental companies.”

The homelessness crisis has worsened with rising costs of living, increasing rent prices, and insufficient funding for community groups. In the first quarter of 2025 alone, the average rent for two-bedroom apartments in the metropolitan area increased by 7.7 per cent, making it harder for residents to find af-

fordable housing.

Eza-Marie Lambert, U1 Arts, reflected on rising housing costs in a statement to The Tribune.

On Jan. 1, the Quebec government introduced a new method for calculating rent. (Anna Seger / The Tribune)

“The only reason my parents and I are able to live on the first floor of a beautiful triplex in the Plateau is because we rent it at a discounted price from my extended family, who purchased the whole building for under $70,000 [CAD] back in the late sixties,” Lambert said. “To put that number in perspective, purchasing that same building in 2026 would run you well over $2,000,000 [CAD].”

Gregor McCall Student Life Editor

On Jan. 29, the Students’ Society of McGill University’s (SSMU) Legislative Council (LC) convened to discuss a new motion proposed by SSMU President Dymetri Taylor. The motion seeks several amendments to the SSMU Constitution—the Society’s fundamental governing document, which outlines SSMU’s roles as the governing body of McGill undergraduates and serves as its legal by-law regarding its status as a non-profit corporation under the Quebec government.

The meeting began with Executive and Councillor reports. During Vice-President (VP) University Affairs Susan Aloudat’s report, Science Councillor Benjamin Yu inquired into McGill’s proposed Identification Policy for Access to Properties Owned, Occupied, or Used by the University, which was presented to the McGill Senate on Jan. 14.

Though Aloudat assured the LC that the Senate had serious concerns with the proposed policy—which would empower unspecified, authorized personnel to request anyone on university grounds to provide McGill or government-issued identification and remove facial coverings—she expressed her belief that the proposed policy would nonetheless pass the Senate and move to the Board of Directors (BoD). Still, she intimated that the policy would undergo reforms before its ultimate implementation.

“I do think that [the Senate is] going to reimagine [the policy], especially for considerations like certain groups who will be experiencing [on-demand identification] disproportionately, who are on campus for perfectly legitimate and academic affairs,” Aloudat said. “[McGill should put] […] guardrails around when this policy will be used, so that it’s only applied and enacted in situations where security is a genuine threat or risk, and not a ‘perceived’ risk or arbitrarily interpreted

risk.”

Also during Aloudat’s report, Arts Councillor Delaney Cahill inquired into SSMU’s policy that grants undergraduates access to Grammarly, a writing-assistant software powered by Artificial Intelligence (AI). Cahill stated that members of the Faculty of Arts professoriate are concerned that SSMU is providing undergraduates with access to AI tools that could be used to undermine academic integrity.

“Some of the [Faculty of Arts] teachers weren’t thrilled about [undergraduate access to Grammarly] and […] the SSMU prompting the students to use Grammarly and AI in general,” Cahill noted. “What is the SSMU doing to combat […] unethical AI use right now?”

While Aloudat stated that it was not her duty to police undergraduates’ use of AI, Taylor later clarified that the generative AI features in Grammarly are unavailable to undergraduates.

Taylor then presented the newly proposed motion, which seeks to amend the SSMU Constitution to, among other initiatives, further empower the LC, change specific terminology, combat the politicization of the BoD, and specify the roles and powers of Board and Executive Council members.

One of the amendments would change the constitution’s nomenclature, replacing the current designation “Board of Directors” with the name “College of Directors.” Taylor explained that part of the rationale for this amendment is that “College of Directors” has a more positive connotation than its current name.

“[The current designation] gives the impression that the Society is more of a corporation than a student society,” Taylor said. “That is the current way in which we are structured [….] We are both [a non-profit] company and a student society, […] but principally the change […] [from] ‘Board’ to ‘College,’ […] more or less presents an opportunity for the Board to be considered into a better light than

how the Board has been viewed in previous times.”

Similarly, Taylor indicated that amendments to increase the LC’s oversight over the BoD and its subgroup, the Executive Council, were necessary in light of past political polarization within the Board.

“[In the past] executives might tap [individuals] because they want to get people that are like-minded to them onto the Board,” Taylor said. “[It served as] a way for the executives […] to then be able to have their vision [of the BoD] be the one that goes forward without necessarily getting the broad perspective that you otherwise get in as a council.”

Taylor mentioned how, rather than focusing on legal, financial, and operational duties, the BoD has gradually and strategically begun to shape what SSMU achieves.

“With the board now and with the way it’s currently structured, for instance, for our job contracts, I’m overseeing the executives, which doesn’t make any sense at all,” Taylor said. “There can be interpersonal issues that

arise [….] That’s what this [amendment] is trying to navigate, as well as to also ensure executive accountability.”

Ultimately, the motion was tabled. If passed by the LC and a student referendum, it would be implemented on May 4.

Moment of the meeting:

Arts Senator Keith Baybayon and VP University Affairs Susan Aloudat discussed potential accommodations to address McGill’s 2026 Spring Convocation dates and the conflicts it imposes on Muslim graduates celebrating Eid alAdha.

Soundbite:

“The Faculty of Music throws the best bars out of every single faculty! You can quote me on that, Tribune!” — VP External Seraphina Crema-Black, regarding the Music Councillor’s report on the success of the Music Undergraduate Students’ Association holiday party.

Editor-in-Chief Yusur Al-Sharqi editor@thetribune.ca

Creative Director Mia Helfrich creativedirector@thetribune.ca

Managing Editors Kaitlyn Schramm kschramm@thetribune.ca

Malika Logossou mlogossou@thetribune.ca Nell Pollak npollak@thetribune.ca

News Editors Eren Atec

Amelia H. Clark Asher Kui news@thetribune.ca

Opinion Editors Moyọ Alabi Defne Feyzioglu Ellen Lurie opinion@thetribune.ca

Science & Technology Editors

Leanne Cherry

Sarah McDonald scitech@thetribune.ca

Student Life Editors

Gregor McCall Tamiyana Roemer studentlife@thetribune.ca

Features Editor Jenna Durante features@thetribune.ca

Arts & Entertainment Editors Alexandra Lasser Bianca Sugunasiri arts@thetribune.ca

Sports Editors Ethan Kahn Clara Smyrski sports@thetribune.ca

Design Editors Zoe Lee Eliot Loose design@thetribune.ca

Photo Editors Armen Erzingatzian Anna Seger photo@thetribune.ca

Multimedia Editors Seo Hyun Lee multimedia@thetribune.ca

Web Developers Rupneet Shahriar Johanna Gaba Kpayedo webdev@thetribune.ca

Copy Editor Sarah-Maria Khoueiry copy@thetribune.ca

Social Media Editor Mariam Lakoande socialmedia@thetribune.ca

Business Manager Laura Pantaleon business@thetribune.ca

Rachel Blackstone, José Moro Gutiérrez, Dylan Hing, Lia James, Ethan Khan, Antoine Larocque, Sophia Lay, Lialah Mavani, Talia Moskowitz, Julie Raout, Parisa Rasul, Alex Hawes Silva, Michelle Yankovsky, Ivanna Zhang Lilly Guilbeault, Emiko Kamiya, Alexa Roemer

CONTRIBUTORS

Eimaan Ahmed, Lulu Calame, Nello Giuliani, Devdas Hind,Will Kennedy, Camila Sierra Ordóñez, Gretta Iraheta Palacios, Sophia Angela Zhang Gwen Heffernan, Abbey Locker. Sophie Schuyler

IIn 2020, the Black Class Action Secretariat (BCAS), a nonprofit organization dedicated to addressing systemic discrimination against workers across Canada’s public institutions, filed Thompson et al. vs Canada, a federal class action representing 45,000 Black Canadians. The lawsuit seeks to address systemic anti-Black racism in the Public Service of Canada, namely discrimination in the hiring and promotion of Black employees.

After five years of litigation, the Federal Court denied certification of the class action in March 2025 . Despite publicly acknowledging the pervasive nature of anti-Black discrimination in the Public Service and settling class actions with other groups in the same sector, the Canadian federal government has refused to recognize the legitimacy of the lawsuit’s claims and has spent over $15 million CAD targeting the BCAS aggressive legal injunctions. By financing the obstruction of Black public servants from legal channels instead of taking concrete, institutional action against systemic racism, the Government of Canada has once again revealed that its commitment to fighting anti-Black discrimination is superficial and

Nello Giuliani Contributor

Black History Month in Canada is a celebration of Black people and their cultures, the diversity of Black communities, and the contributions and legacies of Black Canadians throughout the country’s history.

However, Black History Month is often viewed purely as commemorative, intended to spotlight Black historical figures for the sake of mere acknowledgment and recognition. Yet, the month’s purpose lies far beyond that. Black History Month involves the conscious reevaluation of how histories are written, constructed, and shared, by emphasizing the lesser-known aspects of Black history, noting how information and histories are shaped by power relations, and actively decolonizing collective memory and the process of history creation. This approach, known as historiography, serves to analyze how Black history has been and must continue to be revisited, re-celebrated, and reunderstood.

In Canada, February was first

perfunctory. The Canadian federal government’s continued prioritization of public statements over effective policy only leads to further entrenchment of structural racism in the public sector—a pattern mirrored by institutions across the country, including McGill.

Black employees are chronically underrepresented in the Public Service, making up less than two per cent of managerial positions and often being hired in lowerlevel administrative categories. In the criminal justice system, where Black people are disproportionately targeted through over-policing and incarceration, representation is crucial. A lack of diversity and Black leadership within the Department of Justice and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) shapes outcomes for Black Canadians and further ingrains bias into already discriminatory systems.

To address these gaps, the BCAS lawsuit has demanded several tangible action items: Equitable representation, an external reporting mechanism for harassment and misconduct, financial compensation, and a Black Equity Commission to coordinate recommendations. Injuries amount to $2.5 billion CAD, with the BCAS also requesting that funds be allocated for punitive damages to deter future discrimination.

The Federal Court justified

rejecting the lawsuit’s certification by asserting that its claims could risk over-expenditure, despite the government comfortably investing $15,024,452 CAD in legal dues to fight the BCAS. This funding could have been transformative if directed toward the action items identified by the BCAS, or if employed to tackle anti-Black racism in other institutions across Canada, such as the healthcare, education, housing, and child welfare systems. The federal government’s message is clear: Canada would rather invest in silencing legal claims than taking genuine steps to confront antiBlack racism.

Crucially, the lawsuit also demands amending the Employment Equity Act to create a separate category for Black employees distinct from the ‘visible minority’ designation, a term used to identify groups eligible for equity measures. This strategy of demarcation erases complex differences in experiences between racialized groups in Canada, instead choosing to define ‘visible minorities’ in the negative, as “persons other than Indigenous people who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour”—a framing that positions whiteness as the default against which everyone else is defined. By homogenizing all racialized groups into a single umbrella category, this approach neglects how systemic racism targets Black Canadians

through distinct mechanisms that lead to disparate inequities.

This pattern of neglect for comprehensive reckoning is not confined to the federal government. Bound by the Employment Equity Act, McGill’s own policies are too shaped by the presence of the ‘visible minority’ designation and its accompanying negligence, with McGill’s commitment to reconciling its history of racism and slavery remaining superficial. Reporting and faculty testimonies continue to document severe underrepresentation of Black professors, hostile workplace environments, systemic discrimination against Black faculty, exclusion from senior leadership, and an over-reliance on Black labour to drive anti-racism efforts.

The BCAS has since appealed the Federal Court’s refusal to certify their class action. The Canadian government, its courts, and institutions like McGill are now confronted with a choice: Continue to rely on empty gestures, or take meaningful action toward fighting anti-Black racism. Institutions must disaggregate ‘visible minority’ data, institute binding hiring and promotion commitments for Black workers and faculty, and create independent mechanisms for reporting anti-Black discrimination. Not statements, not mere recognition, not diversion and distraction— radical, systemic change.

designated as Black History Month in 1978 by Daniel Hill and Wilson Brooks, the founders of the Ontario Black History Society (OBHS). In 1995, Canadian Member of Parliament Jean Augustine presented a motion to formally recognize February as Black History Month, which was unanimously approved by the House of Commons. Augustine, having worked in education, understood the importance of institutionalizing this celebration within Canadian education and collective memory.

However, the motion to recognize Black History Month was only fully passed by Parliament in 2008, when Senator Donald Oliver pursued its recognition in the Senate. Oliver emphasized the importance of Black History Month in challenging our common perceptions of history and tackling racial prejudices. He also tied the month’s value to Canadian pedagogy, stating schools must teach the country’s history of slavery and segregation—the latter of which lasted well into the 1960s—in order to understand the present-day fight against anti-Black racism. Therefore, one of the active goals of Black History Month is to analyze biases

and how they have systematically hidden stories from conventional Canadian history.

Systemic biases still persist today, including through notions like Canadian exceptionalism, under which anti-Black racism is often depicted as external and U.S.specific. Overlooked far too often are patterns of prejudiced policing and disproportionate incarceration rates in Canada. In 2015, Black people were twice as likely to be accused in Canadian criminal courts, and in 2020, Black people accounted for nine per cent of federal correction populations, despite making up only four per cent of adults in Canada. Also neglected is the underrepresentation of Black people in academia, as only 2.3 per cent of high-ranking positions at Canadian universities were held by Black professionals as of 2024. These statistics demonstrate that Anti-Black racism is not a strictly American phenomenon, and reveal the critical significance of Black History Month as a mechanism through which to revisit such biases.

An important part of this process is interrogating how history has selectively omitted Black narratives. This goal does not have to be solely

pursued through historical research and education reform, but can also be achieved through cultural events, such as music, visual art, and performance art. In this way, cultural events become part of the historiographical process themselves—sites where Black artists and communities reframe dominant narratives and participate in the ongoing reconstruction of collective memory.

Black History Month’s historiographic power lies in its recurrence, its nature annually underscoring the voices of Black Canadians while also finding new ways to challenge Canadian history. One of the best ways to continue this tradition is through education. At McGill, this means going beyond initiatives and events during February to offering courses on Black history and critical Canadian history, designating a program specifically for Black Studies, and reconciling its own histories of slavery, discrimination, and exclusion.

Black History Month anchors a celebration of Black excellence and cultures, but this cannot exist without an ongoing commitment to reexamining the stories Canada tells about itself.

Camila Sierra Ordóñez Contributor

n November 2025, the McGill School of Social Work published a study examining racial disparities in child welfare interventions across Canada, finding that Black children were investigated for maltreatment at 2.27 times the rate of white children. When researchers matched cases with similar clinical and socioeconomic profiles, out-of-home placement rates were twice as high for Black children as for their white counterparts.

Existing data has posited that the overrepresentation of Black families in child welfare interventions reflects structural inequalities. Researchers note that poverty and its associated factors are the primary drivers of out-of-home placement, and with Black Canadians experiencing disproportionately high rates of poverty, they argue that racial disparities in interventions merely reflect the impact of systemic racism on socioeconomic status. However, these disparities cannot be explained by poverty alone.

Child welfare practices have systematically targeted Black families through biased decision-making, overpolicing, and heightened surveillance of Black families. Existing risk assessment tools have failed to account for differences in parenting styles between families, revealing a profound racial bias embedded within national child protection systems. Yet,

these findings do not include Quebec, as the province does not collect or publicly release comparable race-based data on child welfare practices.

Quebec’s failure to make race-based data publicly available limits the province’s ability to identify and respond to potential disparities in its youth protection system. Without race-based data, the youth protection system is shielded from accountability, dangerously obscuring the racial inequities faced by Black children and their families.

In the context of a system that holds the power to separate families and inflict lasting trauma, race-based data is crucial to understanding the over-policing of Black families within our province’s youth protection systems. Quebec’s failure to collect accessible, race-based child welfare data has slowed down that initiative, forcing professionals and scholars to rely solely on data collected at the national level, namely, the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS). This negligence creates a significant and alarming information gap. The absence of disaggregated data on racialized communities makes it impossible to accurately assess how racial bias impacts the overrepresentation of Black youth in the Canadian child welfare system.

This is not the first time Quebec has demonstrated inconsistency in addressing race-based issues and youth protection. In 2021, the Quebec government conducted an evaluation of child welfare systems across the

province, with its final report revealing that Black children account for approximately 30 per cent of children in the youth protection system, despite only representing 15 per cent of the population. The report emphasized that this statistical phenomenon could be attributed to social workers’ biases, calling upon the government to address racism within the system. However, years after the report was issued, most of its recommendations remained incomplete or inconsistently applied. Of the report’s 65 recommendations, the Commission spéciale sur les droits des enfants et la protection de la jeunesse found that only one has been fully implemented.

An estimated 61,104 Canadian children were in out-of-home care in March 2022. The national average rate of out-of-home care was 8.24 children per 1,000.(Anna Seger / The Tribune)

Addressing how over-policing shapes youth protection interventions involving Black families requires more than collecting and releasing disaggregated child welfare data. It also requires the acknowledgment of systemic racism in youth protection and responses through concrete reforms. These measures may include meaningful partnerships and collaborations with community organizations to better understand

Ellen Lurie Opinion Editor

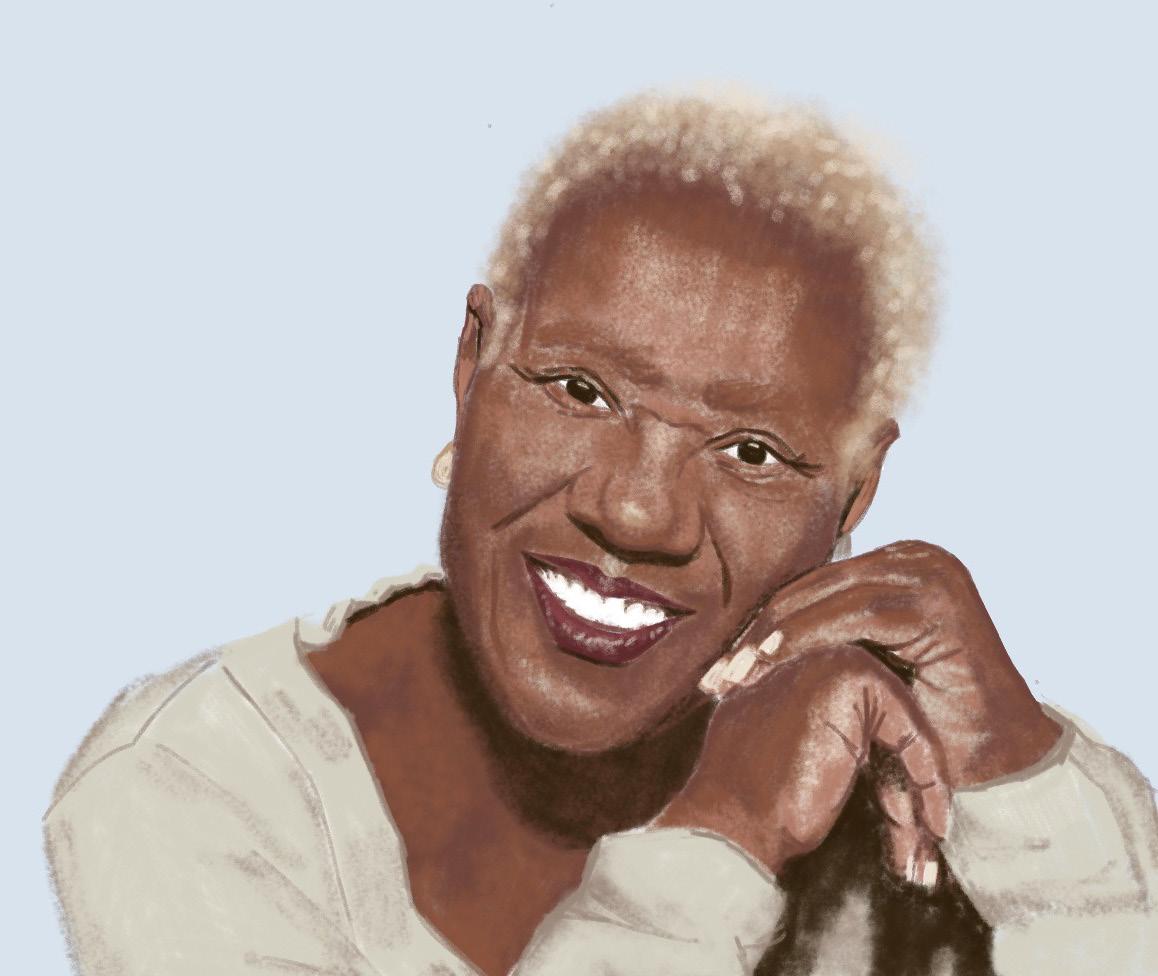

In July 2025, Frank Paris, a 52-yearold Black man raised in Montreal, was sentenced to three years in prison after pleading guilty to trafficking cannabis and hash. However, with the help of his lawyer, who submitted a report outlining Paris’s experiences with systemic racism, the judge reduced his sentence from 35 to 24 months.

This style of report is known as an Impact of Race and Culture Assessment (IRCA).

IRCAs offer a tactic for criminal justice professionals to inform judges of the effect of systemic discrimination on the offender, their life experiences, and, therefore, their experiences with the justice system. IRCAs are employed at the sentencing stage of trials and are often used to advocate for reduced sentences or alternatives to incarceration.

IRCAs represent a critical, anti-racist method to address the overrepresentation of Black individuals in the carceral system. By providing an opportunity for judges to reevaluate overly punitive sentences, courts are able to achieve justice outcomes that avoid further entrenching systemic racism in courts and prisons.

Paris’s case was the first time in Quebec that a judge had used an IRCA when determining a sentence for a Black offender. Paris’s IRCA outlined his experiences with systemic and interpersonal racism in Nova Scotia, where he spent most of his summers as a child. Nova Scotia is often referred to as

‘the deep south of Canada,’ home to the highest rate of hate crimes across the country and site of the destruction of Africville. The report also outlined several incidents in which Paris had faced overt racial discrimination, including a time when he was detained in a holding cell for immigrants despite being a Canadian citizen. Without an IRCA, the judge’s verdict would have neglected how these experiences shaped Paris’s relationship with the justice system.

Since 2021, the Government of Canada has offered substantial funding to support the implementation of IRCAs across the country, with these funds earmarked for training legal professionals who prepare IRCAs, professional development courses, and provincial costs associated with IRCAs.

However, in 2025, Quebec turned down federal funding for IRCAs, as Christopher Skeete, Quebec Minister Responsible for the Fight Against Racism, argued that IRCAs contradict a key aim of anti-racism: Equality under the law. According to Skeete, using race as a criterion by which to evaluate and determine justice outcomes is, in itself, an act of racism.

Yet Skeete’s analysis flattens the true purpose of policies like IRCAs: Not equality, not equity, but justice—collectively challenging the underlying social structures, power dynamics, and institutional practices that perpetuate injustice.

Affirmative action measures are instrumental in correcting systemic biases against marginalized groups. IRCAs do not represent the undue targeting of a racial

minority. Instead, they facilitate the necessary and legitimate uplifting of Black Canadians, a group that colonial forces and the Government of Canada have systemically disadvantaged through over 200 years of slavery, decades of immigration restrictions, formal segregation in education, and still today, racism in the workplace, housing discrimination, overrepresentation in the criminal justice system, and police profiling.

Offering resources or making policy determinations based on ‘equality’ in a system that is inherently unequal merely maintains the systemically discriminatory status quo. Only through anti-racist, justice-based protocols can true equality within institutions like the criminal justice system be realized.

Yet denialist myths surrounding systemic racism in Quebec are disturbingly common.

Quebec Premier François Legault has repeatedly asserted that systemic racism does not exist.

The myth of Canadian exceptionalism still persists, under which it is asserted that Canada is a utopian, ‘raceless’ society that has escaped the rise of populism and white nationalism by virtue of its unique, multicultural

the lived experiences of the targeted families, instituting anti-bias training for social workers, and implementing the recommendations from expert committees such as Quebec’s Commission spéciale. Until Quebec fully confronts systemic racism as a central driver of Black children’s overrepresentation in the youth protection system and starts collecting and disaggregating data at the provincial level, it cannot credibly claim a commitment to addressing structural racial inequities. Meaningful action must be informed by transparent data and guided by the experiences of the communities most affected.

nature. The Canadian census continues to manipulate and erase the concept of race from its surveys, leading not to a more equal society but to a shortage of the data necessary to inform its reconfiguration.

The use of an IRCA in Paris’s case has been subject to widespread backlash, including an incredibly hateful piece by La Presse columnist Patrick Lagacé, who called it “de la bullshit pour jus.” Yet these critics are not defending fairness; they are defending a status quo where systemic racism persists unchallenged. A justice system that refuses to see race is not neutral—it’s just more efficient at reproducing injustice.

‘Aunties’ Work: The Power of Care’ spotlights

Bunyan’s exhibit reflects a collaborative process with Montreal’s Black community

Gretta Iraheta Palacios Contributor

In many Black communities, ‘auntie’ is not just a family title, but a mark of respect given to women who serve as pillars of their community, regardless of blood ties. They serve as nurturers and mentors to the youth, creating protected spaces where members of their community can dare to dream. Though their labour often goes unacknowledged, its impact is deeply felt by their loved ones. Aunties’ Work: The Power of Care at the McCord Stewart Museum, created by fashion designer and researcher Nadia Bunyan, hon -

ours the resilient care networks forged by these matriarchs in Montreal’s Black communities.

As the founder of Growing A.R.C., a nonprofit that builds community through interaction with material culture and sustainability practices, Bunyan designed the exhibit to embody the core values that guide her work. She made community collaboration central to her creative process, working closely with Montreal’s Black community. Through 21 audio interviews, Bunyan invited members to share their own experiences with their aunties and reflect on the impact of their care. This process gave her a clear understanding of how these figures keep their community united through acts of love and care.

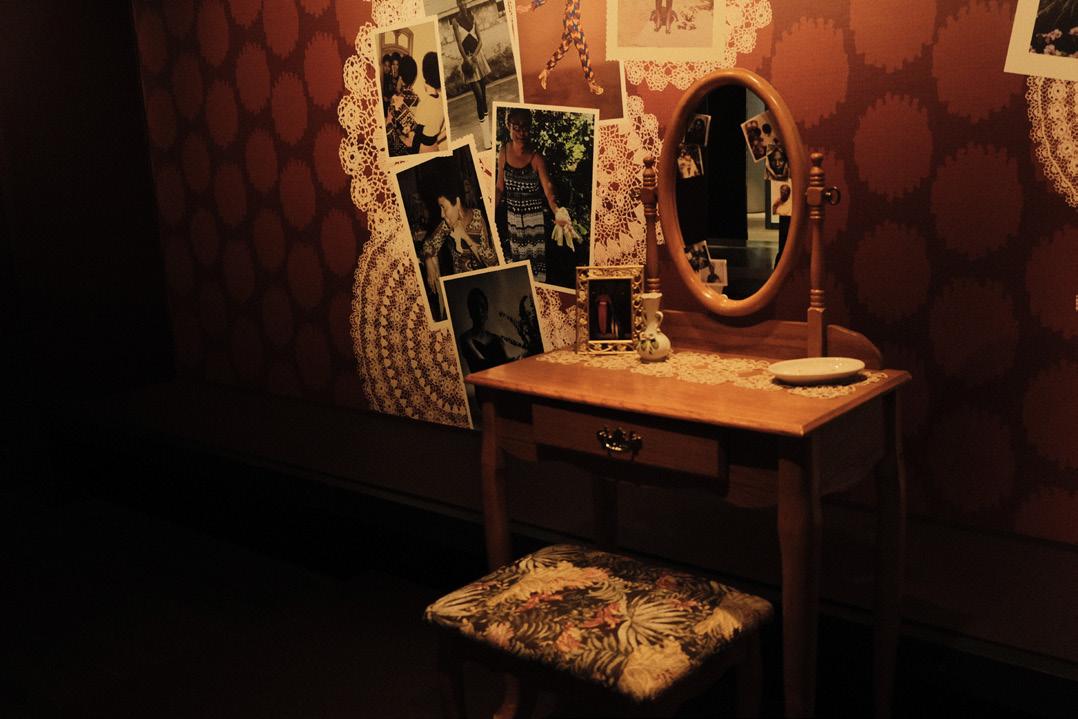

The exhibit’s first section, “Bodies of Care,” features three spotlighted mannequins, each representing a different decade: the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. Bunyan explained in a conversation with Alexis Walker, hosted by the museum, that the mannequins and their placement recreate

the comfort and safety of entering a room and being greeted by one’s aunties. A lace doily motif decorates the wall behind the mannequins, a detail Bunyan’s interviewees consistently recalled seeing in their aunties’ homes. As a result, the doily motif appears in every section of the exhibit. The mannequin embodying the ‘80s wears a yellow blouse and pants ensemble that once belonged to Bunyan’s mother, adding a personal touch to the installation.

The “Materialities of Care” section displays borrowed belongings, including garments, books, and CDs, revealing how Black matriarchs influence different facets of life for their loved ones. A touchscreen also allows visitors to gain further insight about the pieces—their source, the stories they tell, and their cultural significance.

A vintage vanity anchors the “Reflections and Continuity of Care” section. The piece sits within a halo of pictures of various aunties, dating from the ‘70s to the present day, creating a sense of being watched over by these nurturing figures.

The vanity’s mirror reminds visitors that they, too, are a reflection of the work of aunties and invites them to consider how they can continue the cycle of care for the generations to come.

Lastly, the “Discussions of Care” section features a video projection of a roundtable discussion between some of Bunyan’s

interviewees. As one walks through the exhibition, the voices of community aunties and of the people who have directly felt the impact of their care can be heard. In the interview clips, they share their fondest memories with these matriarchal figures.

Bunyan’s overall work also touches on a social, cultural and political facet of Black communities. While the selected pieces represent symbols associated with aunties, they equally reflect the respectability politics present within the Black community, under which the social scrutiny Black people face manifests in a concern with self-presentation. However, through the love and care that the aunties impart, this deep attention to their appearance shifts into a sense of pride surrounding their identity.

At the end of the exhibition, a private nook offers notebooks and pens for visitors to write down their own reflections on how aunties have shaped their personal lives. Bunyan explained that this section positions itself as a contrast to the ephemerality of art expositions. Through the words on the pages, the experience of the exhibit is immortalized.

Aunties’ Work: The Power of Care runs until April 12, 2026, at the McCord Stewart Museum, located on rue Sherbrooke.

Tolstoy transformed: McGill’s Arts Undergraduate Theatre Society’s immersive ‘Great Comet’ shines Students adapt a complicated Russian novel into a genre-bending, high-energy spectacle

Sophia Angela Zhang Contributor

From Jan. 24 to Jan. 31, the McGill Arts Undergraduate Theatre Society (AUTS) staged Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812 , a musical originally created by Dave Malloy, as their annual performance. The show reinterprets a 70-page excerpt of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace , set in 19th-century Moscow, as the characters experience love, jealousy, heartbreak, familial obligation, and societal expectations. AUTS director Milan Miville-Dechene explains that even though the story spans 200 years, the musical explores themes that remain deeply relevant.

The show follows the countess Natasha (Claire Latella, U1 Music) and her cousin Sonya (Miranda De Luca, U3 Education) as they arrive in Moscow, awaiting the return of Prince Andrey Bolkonsky (Chris Boensel, U2 Arts), Natasha’s fiancé, who has been sent off to war. One night at the opera, the rogue Anatole (Frank Willer, U1 Science) sweeps Natasha off her feet. Convinced they are in love, Natasha breaks off her engagement and makes plans to elope with the charming Anatole, whom she has known for just a few days. When others discover their plans, Pierre (Sam Synders, U4 Arts), Andrey’s best friend, steps in to prevent the disaster.

Théâtre Plaza was the perfect venue for this show, with its moody, atmospheric

lighting and spacious interior. The actors used the balcony and floor as part of the set, physically and metaphorically engrossing the audience in the story. The lighting reflected the musical’s numbers distinctively—when the characters were partying at the club, the lights switched to green and purple, reminiscent of hazy modern clubbing.

Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812 embodies the most extravagant and outlandish aspects of musical theatre, perhaps most notably by constantly breaking the fourth wall, made easier thanks to the confines of the intimate venue.

From the first musical number, “Prologue,” the cast interacts directly with the audience by making eye contact and chanting the lyrics “Gonna have to study up a little bit / If you wanna keep with the plot / ‘Cause it’s a complicated Russian novel / Everyone’s got nine different names / So look it up in your program.” Complete with designated interactive seating, a few audience members were brought up to the stage and spun by various characters.

Some cast members elaborated on how they connected with audience members and handled the show’s fourth-wall breaks.

“It’s definitely intimidating because [...] I love to connect with a scene partner, so having to connect with an audience member who is like ‘I’m not in this right now’ is definitely different, but so much

fun,” De Luca said in the interview with The Tribune

Later, maracas were handed to attendees, inviting them to join the live orchestra. The setting and the story are removed from modernity, a fact the musical itself embraces, blending story and reality and enticing the audience to join the colourful world of Moscow.

The cast’s performances were also remarkable for their ages. Latella dazzled with her singing, especially in her solo “No One Else.” Complemented by her dynamic acting, she brought the wide-eyed, romantic young girl to life. Though Mary, Andrey’s sister, is a relatively minor character, Ariel Goldberg (U0, Arts) conveys Mary with her abusive father’s impossible whims through vocal performance, imbued with a slow, mournful quality. Mary and Natasha’s dissonant harmony in “Natasha & Bolkonskys” perfectly conveys their apprehension and clash of personalities. Willer, on the other hand, exudes Anatole’s effortless charm and suavity from his first moment on stage, making the audience feel Natasha’s immediate infatuation.

Ryan Jacoby’s (U1, Science) performance as Dolokhov embodies what made this musical so special. The delicate balance between the fun, theatrical humour and the grounded dramatic emotions epitomizes the quick-witted humour of the show.

The company numbers were among the most impressive, featuring elaborate choreography, precise synchronization, and stellar vocal harmonies from the entire cast. The ensemble was integrated into the musical, with their presence—or absence—noticeable in the musical numbers. With the entire company on stage, it was easy to feel the chemistry among the cast, which translated into a natural camaraderie among their characters.

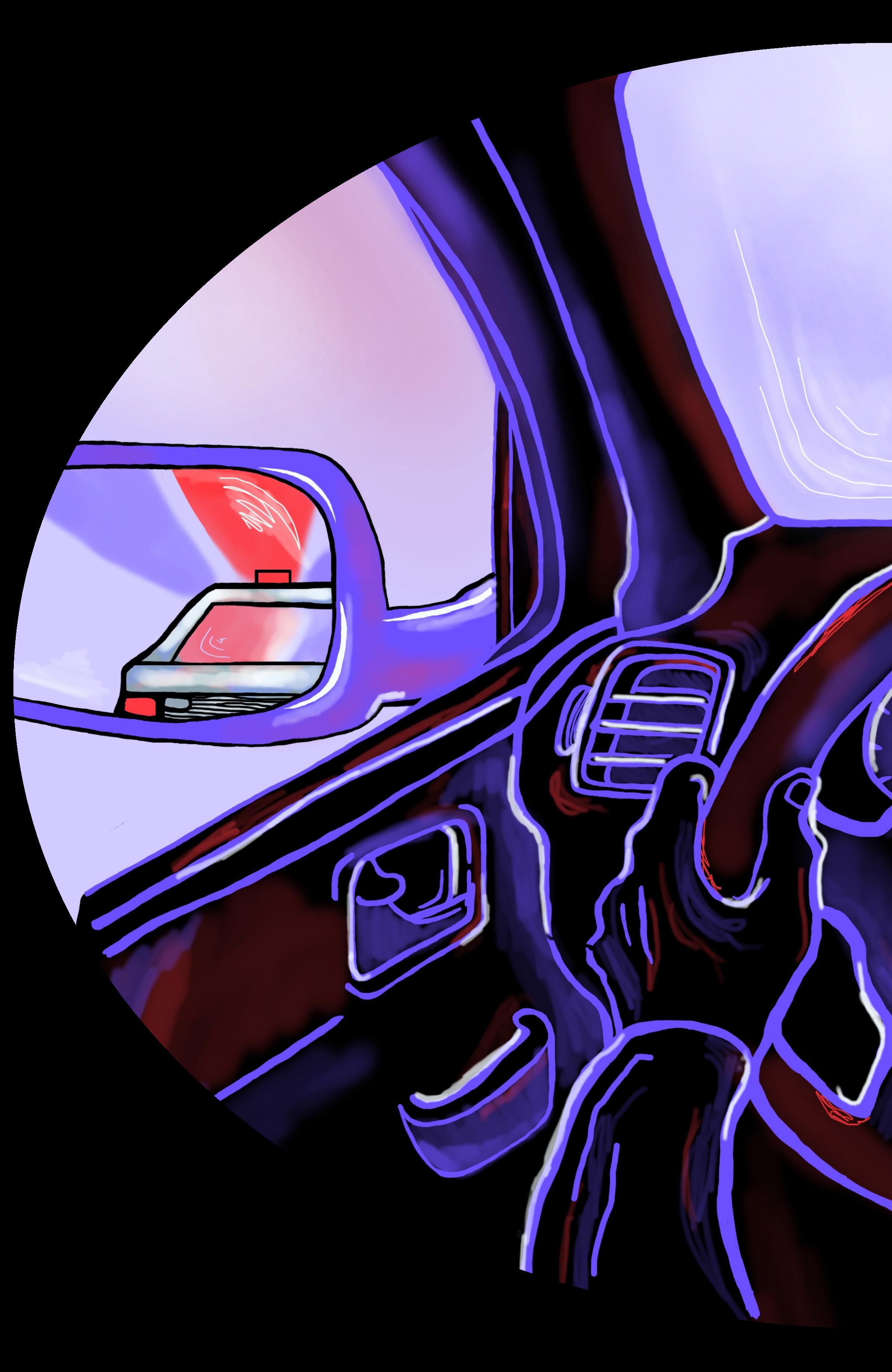

On the afternoon of April 2019, Joseph-Christopher Luamba was driving to Collège Montmorency for a study session when a police cruiser coming from the opposite direction turned around to pull him over. After running checks, the officer let him go without issuing a ticket. In the 18 months following his driver’s licence issuance, Luamba was stopped more than ten times. Each time, he was let go without so much as a fine. Luamba’s experience is not an anomaly, but a view into a broader pattern of how ‘random’ traffic stops operate for Black motorists in Quebec when a law allows police to stop drivers without cause, without criteria, and without accountability.

On Jan. 19 and Jan. 20 of this year, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) heard arguments for Luamba v. Quebec . Should the Supreme Court rule against Quebec, it could set a precedent with broader consequences for other provinces that employ similar traffic stop regulations. Currently, random or arbitrary stops are permissible in all other provinces, which continue to operate under the 1990 Supreme Court precedent set in R. v. Ladouceur

Two lower courts have already ruled these stops unconstitutional. Quebec Superior Court

Justice Michel Yergeau ruled in October 2022 that Article 636 of Quebec’s Highway Safety Code—the provision authorizing random traffic stops—violates sections seven, nine, and 15 of The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantee liberty, security, protection against arbitrary detention, and equality rights. The Quebec Court of Appeal unanimously upheld that decision in Attorney General of Quebec v. Luamba in October 2024. Given the Court of Appeals decision that the negative impacts of random stops on the Black community outweigh the benefits to the public of letting them continue, random traffic stops have been suspended in Quebec since April 2025.

Now, Quebec’s Attorney General and Minister of Justice, Simon Jolin-Barrette, is asking the Supreme Court to overturn those rulings, arguing that police need this power to ensure road safety. Interveners, including the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) and Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), have joined in support, arguing that random mobile stops are more effective at catching impaired drivers than stationary checkpoints. But this framing pits road safety against civil rights, as though protecting one requires sacrificing the other, creating a false binary that obscures what is actually at stake: Whether a discretionary police power that has been proven to enable racial profiling can be justified under the Charter.

Quebec officials and supporters of their case in Luamba describe these as ‘random’ traffic stops— but the data tells a different story. When police are free to stop any driver for any reason—or no reason at all—the pattern remains consistent: Black and Indigenous drivers are stopped at rates vastly disproportionate to their share of the population. What Quebec calls discretion, the evidence establishes as discrimination.

Since 2022, Quebec police forces have begun collecting race - based data on who they stop, but many have been reluctant to publish the results—a reticence that speaks volumes about what those numbers are likely to show. Data from Laval, Quebec’s third-largest city, showed that Black people were subjected to 19.7 per cent of police stops despite comprising only 8.9 per cent of the population. In Montreal, a 2019 report spanning data from 2014-2017 found Black people were approximately 4.2 times more likely to be stopped by the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal than white people, and Indigenous people 4.6 times more likely.

Harini Sivalingam, director of the equality program at the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, stressed that there is nothing neutral about how

this power operates.

“I want to be clear, there’s nothing random about these stops,” Sivalingam said in an interview with The Tribune . “We’re not talking about a structured program to check sobriety. What we’re talking about is a police power that just enables anyone, at any time, anywhere to be subjected to what we feel is an unconstitutional stop by police.”

The harm, she stressed, runs far deeper than momentary inconvenience. At trial, Black individuals described the psychological toll of being stopped over and over again—persistent sleep loss, reluctance to leave home, anxiety, and a deep erosion of trust in a police force that targets, rather than protects, their communities. Luamba himself testified that whenever he sees a police cruiser, he instinctively prepares to pull over.

“The harm doesn’t stop at the roadside,” Sivalingam explained. “It doesn’t stop before or after. The harm is

profiling that it has accumulated since. MADD has warned that striking down Article 636 could lead to increased injuries and death related to alcohol and drug-impaired driving. The CACP justifies random stops as an essential tool for promoting compliance with traffic regulations.

This framing, however, diverts attention from what the evidentiary record actually shows. In 2024, Quebec’s Superior Court, upheld by the Court of Appeal,

ongoing—the anticipation, the fear and the anxiety of being pulled over is very real.”

Sivalingam also pointed to how young Black children are taught from early ages how to interact with police to protect themselves. These conversations, as a routine part of the Black experience in Canada, are themselves an indictment of the practice of ‘random’ stops—and a reminder that what’s at issue in Luamba is not just how police interact with drivers, but how the law structures everyday life for entire communities. Instead of building confidence in public safety, these traffic stops under Article 636 continuously undermine it.

Quebec’s defence centres on grounds similar to those the Supreme Court accepted in 1990: Police need discretionary powers to keep roads safe, ignoring three decades of evidence on racial

found that the Attorney General failed to adduce evidence that random, suspicionless traffic stops improve highway safety, inadequately demonstrating a rational connection between this power and the government’s stated safety objectives.

According to Solomon McKenzie, counsel to the Canadian Association of Black Lawyers in Luamba , the expert record in the case is unequivocal.

“There’s been extensive expert evidence led in the case of Luamba,” McKenzie said in an interview with The Tribune . “All of whom have shown that this kind of unfocused, unstructured, and randomized stop of individuals is not effective policing. It does not result in reducing traffic infractions.”

Conspicuously, the rulings do not affect structured, program - based roadside checkpoints, such as sobriety roadblocks, whose legality is expressly preserved in Luamba and

Opolice discretion and arbitrary power. Lorne Foster, professor and director of York University’s Institute for Social Research, has studied this intersection for over a decade.

“I do accept that discretion is necessary for officers to handle complex situations,” Foster explained in an interview with The Tribune . “But when you use discretion, it can also be influenced by implicit biases, and that can lead to racialized stereotypes.”

The difference lies in accountability, he says.

publish comprehensive race-based data, they’re just disabusing the public with their ignorance,” Foster said. “You have to somehow monitor that. You have to have an empirical, evidence-based tool to ensure that that is the case.”

His point is simple: A government that does not collect adequate race-based data cannot credibly insist that race plays no role in how a power is used.

“An example of arbitrary use of police power is when there’s no evidence-based monitoring, no standards, no transparency, and no civilian oversight.”

Article 636 provides none of these safeguards. It grants police unconstrained authority to stop any driver without cause, without criteria, and without review—precisely the conditions under which bias flourishes. This is not

“By permitting unfettered discretion, the law makes it impossible to distinguish between its permissible operation and its unconstitutional abuse, so that racial profiling remains both pervasive and legally invisible,” Sabrina Shillingford, who represented the Black Legal Action Centre before the Supreme Court, said in an interview with The Tribune

This is precisely why the ‘bad apples’ defence fails. As McKenzie put it in an interview with The Tribune : “The full phrase is a bad apple spoils the bunch. The literal phrase in English is that if you let bad actors fester inside a system, they ultimately corrupt the entire system.”

Quebec is asking the Supreme Court to accept that the speculative benefits of random stops outweigh their documented injustices.

“The evidence that we do have shows that Black people are being disproportionately stopped and are suffering actual harms. At a certain point, it starts to prioritize the hypothetical safety of some versus the very real safety of Black individuals who are being targeted,” Shillingford said in an interview with The Tribune

The implications extend beyond traffic stops. The justice system functions as a race-making institution—one that actively constructs and reinforces racial categories through its operations. When Black drivers are stopped at rates far exceeding their share of the population, they are disproportionately exposed to criminalization. This produces statistics showing higher rates of criminal involvement—statistics that then get cited to justify the very policing practices that produced them.

ndom’ stopshasbecomeatest

protect a

The SCC striking down Article 636 would not, on its own, dismantle this cycle. But upholding it would constitutionally entrench one of its key mechanisms—signalling that police powers enabling racial profiling can survive Charter scrutiny so long as governments invoke road safety. It would effectively ratify the false safety - versus - rights binary Quebec has cultivated, treating the mental - health harms, the erosion of trust, and the everyday fear described by Black drivers as an acceptable price of doing public safety.

“This isn’t a hard case,” Sivalingam said. “It’s very clear-cut. The law disproportionately harms racialized people, undermines equality, and doesn’t enhance public safety. It can’t be justified.”

discretion exercised within limits; it is arbitrary power without accountability.

THE ‘BAD

ial profling.

which police can still use under designated road - safety programs.

“I think what’s important is to recognize that you can have programs that reduce impaired driving that don’t result in this arbitrary power that enables racial profiling,” Sivalingam said.

The safety argument also obscures a crucial legal distinction: The difference between legitimate

Quebec’s attorney general has argued that the problem lies not with the law itself but with individual officers who conduct “illegal interceptions” based on prejudice. The logic follows that the power to randomly stop is neutral—racial profiling results from its sporadic—not systemic— misuse.

But this distinction collapses under scrutiny. Racial profiling often operates implicitly. Without objective criteria governing who gets stopped, without data collection, and without oversight, there is no way to identify when a stop is discriminatory and when it is not. The law provides no mechanism to detect its own abuse.

“When Quebec claims stops are exercised without regard to race while refusing to collect or

For Black drivers like Luamba, this case is not about an abstract balance between rights and safety. It is about whether the law will continue to sanction a power that has taught them to brace every time a cruiser appears in the rear- view mirror, to teach their children how to manage encounters with law enforcement that are treated as inevitable, and to live with the ongoing anxiety that those encounters can happen at any moment, without cause. The SCC cannot undo the years in which ‘random’ stops have normalized that reflex for Black communities. But it can start by refusing to continue constitutionally underwriting it.

NELL POLLAK MANAGING EDITOR

Opera McGill and McGill Symphony Orchestra present Britten’s harrowing tale

‘The Rape of Lucretia’ haunts audiences with soaring melodies

Alexandra Lasser Arts & Entertainment Editor

Trigger warning: This piece contains mentions of sexual violence.

The famed red curtain rises on a scene of violence and destruction.

Soldiers surround the shattered remains of a colossal statue as the opera’s narrators introduce the chaos of the present moment. On Jan. 30, Opera McGill and the McGill Symphony Orchestra premiered Benjamin Britten’s The Rape of Lucretia , directed by Patrick Hansen, to thunderous applause in the historic Monument-National.

Set in ancient Rome, the story centres on the fiercely devoted love between Collatinus (Tristan Pritham, U3 Music), a Roman soldier sent away to fight, and Lucretia (MacKenzie Sechi, PG Artist Diploma in Performance), his loving wife who longs for his return. Her faithfulness inspires jealousy among the other soldiers, eventually spurring Tarquinius, the prince of Rome, to test her chastity and, in a horrifying act of sin, sexually assault her.

The tale is narrated and commented on by the two figures of the Male Chorus (Fletcher Bryce-Davis, MMus 1), and the Female Chorus (AJ Gauger, MMus 2). Drawing on a tradition stemming from ancient Greek theatre, they are removed from the plot and embody the voice of morality sorely lacking from the tragedy.

As a chamber opera, the work allows for intimacy between the group of 11 characters and the chamber orchestra conducted by Stephen Hargreaves. The small ensem -

ble conveys all of the dramaticism while highlighting the psychological aspects of the plot through focused attention on individual melodies. Strings and harp accompanied scenes of care and friendship in Lucretia’s home, while highly percussive instrumentation heightened the soldiers’ brutal bickering. The lighting design reinforces this contrast, illuminating domestic scenes in soft blue tones and casting the military ranks in stark red. When Tarquinius entered Lucretia’s home, Britten and the lighting broke down this contrast with percussive and nonmelodious writing framing a harshly lit home, elevating tension and marking the destructive nature of the act.

Portraying such a horrific tale on stage is a difficult task for anyone, but especially for a young cast of university students. Cast members Sechi and Pritham explained how they approached and portrayed the opera’s heavy content.

“We definitely had several meetings about intimacy and about [...] subject matter,” Pritham said in an interview with The Tribune . “Most of the rehearsals were actually closed, which is kind of rare for us.”

While music students may watch other productions’ rehearsals, closed rehearsals for this opera allowed the cast to grow comfortable with one another and work through the scenes without added pressure. Sechi emphasized the importance of forming a sense of camaraderie before navigating the assault scene.

“We started with a really light-hearted approach so that we would be able to just laugh, [...] because obviously it’s a really difficult scene to navigate,” Sechi said. “It

was very lighthearted and fun so that we could find intimacy and connection in that way before moving into something so horrible.”

The fight between Lucretia and Tarquinius was violent and dramatic, culminating in the act of rape. The audience was blinded by a bright light placed centre stage behind the characters as Tarquinius undid his attire. This choice forced the audience to look away from the brutality, communicating the act without relying on gratuitous portrayals of violence.

The aftermath of the crime focused largely on Lucretia’s psychological state rather than on plot-driven action. Revenge was not carried out, nor was anger expressed through battle. Instead, Sechi’s deep, lamenting voice shifted the typical emphasis on plot to her emotions. Britten’s choice to write Lucretia as an alto not only made her voice stand out against her soprano and mezzo entourage but also conveyed the depth of her grief.

The opera ends without offering a reason or justification for the chaos it depicts. The question, “Is this it all?”

haunts the final scene through its endless repetition. The Romans and Choruses sing together in a beautifully stirring display of solidarity, yet none can find meaning in the painful injustice, forcing audience members to confront the horrors head-on. The delicate yet impactful presentation of this harrowing tale revealed the maturity and talent of the young performers, entrancing the audience through beauty and terror.

Fashion Business Uncovered’s conference merges business and style Behind the scenes of the business world of fashion

Malika Logossou Managing Editor

Fashion is everywhere. It’s in the brands we wear, the trends we follow, the models we admire, and the meticulously staged illusions that flood our feeds. Yet behind every viral look, ‘It girl’, or coveted brand, lies a business quietly shaping visibility, marketability, and how trends are created, sold, and sustained.

On Jan. 24, Fashion Business Uncovered’s (FBU) annual conference put fashion, skincare, and clothing under the spotlight as both art and industry. The room itself felt like a runway of its own: Heels clicked across the room, statement accessories sparkled, and a striking variety of aesthetics—from minimalist chic to bold and creative—displayed that fashion was not merely being discussed but fully lived.

FBU carefully brought together panellists from both global and local brands, including ALDO, L’Oréal Paris, Indeed Labs, Groupe Dynamite, Jack the Publicist Group, and Atelier Détails. The speakers traced their journeys into the fashion world, illuminating the breadth of careers it offers, and exploring how creativity and craftsmanship intertwine with business strategy, technology, and marketing.

A recurring theme throughout the conference was the importance of exposing oneself to opportunities. Speakers encouraged students to pursue internships, network and attend events, and join companies they aspire to work for. They emphasized that a specific degree or linear path is not required to succeed in the fashion and beauty industry.

In an interview with The Tribune, panellist Dimitra Davidson, CEO and co-founder of Indeed Labs, stressed the educational value of such events for students navigating a world where trends and reality evolve faster than academic curricula.

“I did not have [...] at all a foundation of marketing,” Davidson said. “You just figure it out as you go along. If you actually go by a playbook, then sometimes you’re not going to have a point of difference. You’re just going to be exactly like everybody else.”

Social media also took centre stage, with panellists acknowledging its influence in shaping trends and directing brand strategies to fragmented digital audiences.

Nathaniel Woo, Marketing Manager for Men & Skincare at L’Oréal Paris Canada, spoke about the importance of immersing oneself in these online spaces to cater to target audiences.

“One of the best pieces of advice [one of my managers] gave me was to scroll. Literally

set aside 15 to 20 minutes to scroll on TikTok, scroll on Instagram. I even have an account on my work phone that is more tailored to the male algorithm,” Woo said. “I know nothing about hockey. But in that algorithm, it’s literally hockey, soccer, F1, and [...] I don’t usually find that on my personal phone.”

Beyond industry insight, education remains at the heart of the club’s mission. In an interview with The Tribune, Michelle Govorkova, co-executive director of FBU, explained that exposing students to the full spectrum of fashion careers was one of their primary objectives.

“Our main goal and priority here is education and to teach people that there are so many professions and jobs within the fashion industry that are not stereotypical,” Govorkova said. “Obviously, you have your designers, you have your models, you know, [...] the mainstream roles, [...] but what we aim to do here, as for the name ‘Fashion Business Uncovered,’ is to really touch on the business side of fashion because [...] even a fashion company is still a business, right?”

Co-executive director Julie Baillet echoed similar sentiments, emphasizing the importance of revealing the industry’s full scope

through its selection of panellists.

“We just wanted to have [...] this very diversified panel to really show all the facets of fashion and uncover the ‘behind-the-scenes’ that happen within the fashion industry,” Baillet said. “[We wanted to] have [...] many different perspectives from production, marketing, like entrepreneurship, operations, really anything that happens within fashion.”

By the end of the conference, one thing felt clear for attendees: The fashion industry is broad and intersects with businesses more than we imagine. Given that there is no traditional fashion program at McGill, this conference proved to be an inspiring learning experience for many students.

Asher Kui News Editor

Content warning: Mention of The Tribune and its absolutely horrible takes

Icannot count on one hand the number of times I’ve mentioned that I’m an editor at The Tribune , only to receive an eyeroll. In fact, there is a Reddit discussion post that affectionately calls our paper the “least terrible of the bunch.” I get it: If you think The Tribune isn’t perfect, I can assure you that you’re not alone. Whether you fall asleep at night dreaming of our next issue, or you walk past our newspaper stands on campus muttering something PG-13, I must thank you—at least you’re paying attention.

A campus paper that only affirms what you already believe or want to believe is not a newspaper, but a propaganda machine. The Tribune exists to challenge and question the status quo. Even if you don’t agree with us, your criticism sharpens our perspective, and your hostility does not derail us from continuing to write and uncover unspoken injustices.

Nonetheless, this doesn’t stop some from criticizing us for being ‘selectively aware,’ that we care loudly about some issues while staying silent on others. But I implore you to consider: We have, usually, 27 pieces to publish in print every week. Every issue is a matter of editorial judgement. To select one story over another is the nature of journalism, not ignorance toward other injustices.

We must choose carefully what we cover if we want to maximize our leverage in the community. While geographical distance does not make global injustices matter any less, The Tribune ’s inherent job is to cover stories of interest and impact to the McGill community. When we write about McGill’s complicity in Israel’s genocide in Palestine, it’s because we know the student empire has the power to influence institutional behaviour. When we write about McGill’s

inadequate efforts in reconciliation, it’s because we recognize our paper has the power to inform students about McGill’s lacklustre initiatives.

And when we receive your criticism, it urges us to reconsider our journalistic angle. Not only does your attention direct us to what the community cares about, it informs us of where our coverage succeeds and where it falls short. This way, we can sharpen our lens and take responsibility for our choices.

And then comes the accusation that we are a biased paper. There’s no disagreement there—bias is a prerequisite to journalism. Stories carry perspective, perspective carries judgement, and judgement contains bias. The Tribune is inherently biased, and so are other media outlets—even if they claim honest reporting

There is no unbiased reporting. We are biased, and we are proud of it. As a matter of fact, our Anti-Oppressive Mandate clearly states that “we centre anti-oppression in our coverage, our editorials, our hiring, and our workplace practices.” But this is more than a badge we wear; it is a commitment to holding ourselves accountable to readers. Our mandate demands ongoing reflection, compassion, and a willingness to

Parisa Rasul Staff Writer

While struggle must be recognized, it should not—and does not—define a community.

As Andalus Disparte, U3 Arts and VicePresident (VP) Political & Advocacy for McGill’s Black Students’ Network (BSN), said in an interview with The Tribune , “We want to strike a balance between […] educational events that focus on Black history […] but also highlighting Black joy. There’s a tendency during Black History Month for programming to focus a bit too much on Black struggle, but we are so much more than that.”