8 minute read

Landscape solutions

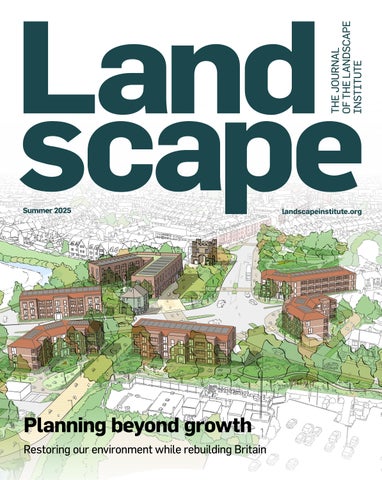

The Southgates masterplan creates a vibrant gateway around the Grade I-listed Southgates in King’s Lynn. © BDP

Built development doesn’t need to come at the cost of the environment and local places. By taking a landscape-led approach, the government can successfully meet its growth agenda while supporting nature recovery and high-quality, sustainable design.

A fresh wave of planning reform is unfolding in the UK under a new government, driven by an acute housing crisis, persistent economic stagnation, the Labour Party’s electoral mandate to build more homes and create more jobs and the political imperative for the new government to make swift progress on key domestic priorities.

Labour’s pathway to government was forged on a mission to “kickstart economic growth… rebuild Britain, support good jobs, unlock investment, and improve living standards across the country”. After a landslide victory in summer 2024, ministers soon began to implement a ‘Plan for Change’ that included a commitment to deliver 1.5 million homes in England during the Parliament and to approve at least 150 major economic infrastructure projects. Such a plan has significant implications for landscape, with reforms now set to reshape how development is planned, delivered and integrated into the wider built and natural environments.

Running in parallel to the government’s growth agenda are the interrelated challenges the UK faces in addressing climate change, biodiversity loss, and public health. Under the Paris Agreement and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, the UK is committed to cutting greenhouse gas emissions and halting nature’s decline. These commitments are set against the sobering reality that the UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, and its National Health Service is under increasing strain from the health consequences of poor-quality living conditions, characterised by air and water pollution, inadequate resilience to climate change and limited access to nature and green space.

This convergence of pressures presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is to align housing and economic objectives with those on climate, biodiversity and public health, to deliver long-term, sustainable value for people, place and nature. In a context where speed and delivery are being prioritised, it is a legitimate concern that both established and current environmental considerations may well be undermined.

This should not be permitted –especially when there is a way forward that enables development and nature to thrive together. The fundamental purpose of the planning system has always been to balance the broader interests of the public against the narrower focus of the developer. The system has long recognised the importance of landscape planning, design and management in addressing and reconciling these competing priorities and applying this approach directly to development. By recognising the role of landscape treatment as a multifunctional resource, and not merely as an aesthetic feature, such an approach ensures that land use change can deliver concurrent social, economic and environmental value. It’s about bringing the issues that currently run in parallel together to provide integrated solutions.

The Landscape Institute (LI) sees nature-based solutions as fundamental to this vision, and to the long-term health, sustainability and value of built development. A landscape-led, nature-based approach creates sustainable, liveable, climate-resilient and attractive places. It makes good use of natural capital, integrates biodiversity and water management, improves health outcomes and supports economic growth. This was the vision we set out in 2024 in our ‘Recommendations for the next UK government; a landscape policy agenda for people, place and nature’.

Within three weeks of entering government, Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, Angela Rayner, had launched an overhaul of the planning system in England, beginning with an updated National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). Further reforms included the introduction of new Spatial Development Strategies and new methodology for setting mandatory housing targets, with stronger emphasis on delivering social and affordable homes. Also included was a commitment to reviewing the green belt and the introduction of a new concept of ‘grey belt’ land alongside brownfield land, with local authorities expected to release appropriate land to meet housing and commercial needs. Additional measures were given to the development of ‘growth-supporting infrastructure’, including transport, energy and data networks. Further reforms, including a national housing strategy, a series of new towns, changes to Environmental Impact Assessments and the flagship Planning and Infrastructure Bill, with its novel proposals for Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs), are also set to play a key role.

From a planning policy perspective, these reforms have far-reaching implications for how landscape is incorporated into the development process. The updated NPPF, for example, seeks to integrate some environmental priorities at the national level, but much depends on how policy is implemented at regional and local levels. The Planning and Infrastructure Bill introduces significant changes, underpinned by new policy instruments such as Environmental Outcomes Reports (EORs), while the Development and Nature Recovery working paper further proposes the establishment of a Nature Development Fund (NDF) that aims to finance nature restoration in tandem with new development. EDPs, managed by Natural England, are proposed to provide a framework to ensure nature-based objectives are addressed through strategic investment and planning. Local Nature Recovery Strategies are also promoted as essential tools to integrate biodiversity planning across administrative boundaries. However, the potential strategic benefits of these proposals to offset nature recovery through the payment of a financial levy may result in a lack of any significant onsite environmental provision. There is little clarity on how this separation between development impact and its mitigation will evolve and it creates a real risk that areas of poorly designed and unsustainable development may potentially be mitigated by remote and distant nature reserves. It is clearly a matter of public interest that all development, including infrastructure, is context sensitive and incorporates good landscape treatment. Failing to address this may result in new areas of environmental and social degradation and the creation of places that are unfit for living.

In addition, devolved and crossboundary decision-making is being advanced in England, supported by proposals for a national land use framework. These measures collectively indicate a shift towards more strategic, system-wide thinking about how development interacts with the natural environment. However, the mechanisms for delivery remain in flux, and the government has yet to fully answer how these new tools will safeguard nature in practice. The resource, skill and funding implications for both local planning authorities and government bodies are also legitimate concerns: does the UK have the right skills in the right places to build the green growth the government has set out? Early results from the LI’s investigation into workforce issues in the landscape sector suggest not. Proposals in the recent immigration white paper aim to wean organisations off the employment of non-UK workers and to meet skills needs domestically. This may work in the mid to long term, but it threatens to increase skills shortages and growth in professional areas (such as landscape) where training to high standards takes years.

When Prime Minister Keir Starmer articulated a ‘Plan for Change’ at the start of the year, he spoke of “taking the brakes off Britain by reforming the planning system so it is pro-growth and pro-infrastructure”. With so much of the government’s proposed reforms still lacking clarity over the environmental implications, Chancellor Rachel Reeves has also said, “we are reducing the environmental requirements placed on developers … so they can focus on getting things built, and stop worrying about bats and newts”. However, the government’s own impact assessment has been able to cite very little evidence that environmental requirements delay development.

In response to the prevailing growth vs nature rhetoric, the LI has responded to numerous consultations, engaged with parliamentarians and joined with organisations across the built and natural environment to raise concerns. We are writing to relevant ministers and meeting government and civil service officials to address planning policy issues and taking a collaborative approach to improvement.

As this edition goes to print, the government has acknowledged that questions have been raised over whether the bill could jeopardise nature protection. In response, Defra continues to point to the NDF and EDPs as a means to adopt a strategic approach, reduce delays for developers and ensure environmental outcomes are delivered more effectively.

Nevertheless, the LI remains concerned about unresolved aspects of the reform agenda, particularly the risk that biodiversity could be displaced off-site, rather than embedded within the places where people live and work, and close to the communities that need access to green space the most.

We believe that landscape-led planning and the appropriate use of nature-based solutions are key to resolving this tension, and we look forward to working with the government, civil service and stakeholders across the industry to drive this approach. By designing with nature, not against it, planning reform can help to deliver the government’s growth agenda and shape a lasting legacy of healthy, sustainable and inclusive places that are fit for living.