2 minute read

Landscape as civic infrastructure

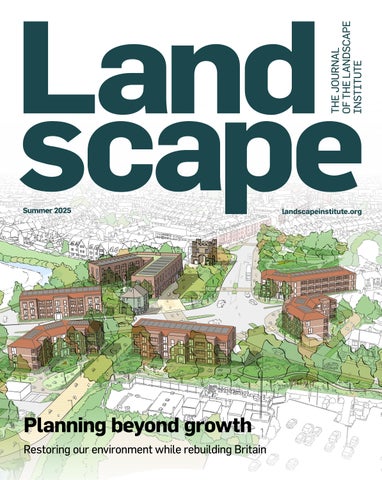

Courtyards for communal gardening & growing. © Liv Brock

A University of Sheffield landscape architecture student uses a design project to reframe the housing crisis in landscape terms

As the UK grapples with a deepening housing crisis, national policy continues to emphasise quantity over quality, prioritising numeric targets over liveability, environmental integrity, and long-term public health. A landscape-led approach offers a powerful alternative: one that integrates housing delivery with climate mitigation, nature recovery, and socially inclusive urban regeneration.

The Sluice Quarters is a third-year hypothetical design project I completed in 2025 at the University of Sheffield, responding to this very challenge. Set on a 4-hectare brownfield site fronting the River Don, the proposal reimagines a former industrial area as a vibrant, affordable and enduring residential neighbourhood. The design delivers 381 modular homes supported by a network of streetscapes, shared courtyards, and green infrastructure that prioritise movement, encounter and wellbeing.

The project proposes a shift away from high-rise, profit-led housing models and instead explores more socially and environmentally responsive forms of development. The structure of streets and courtyards is not just circulation space: it is the social and ecological heart of the scheme. These ‘outdoor rooms’ support everyday physical activity, neighbourly exchange, biodiversity, and long-term adaptability, while helping buffer environmental and urban challenges such as flooding and traffic.

Construction methods and environmental design are equally considered. The use of off-site manufactured timber systems enables faster, lower-carbon construction, while green roofs, rainwater strategies, and biodiverse planting contribute to climate resilience and biodiversity net gain. Crucially, each element is conceived as part of an integrated landscape system rather than decorative surplus.

The Sluice Quarters challenges the assumption that high quality and high delivery are incompatible. By placing landscape at the core of the design process, it reframes housing not as a static commodity, but as adaptable civic infrastructure, capable of fostering equity, improving health, and restoring ecosystems. In a time when the debate around housing is dominated by crisis rhetoric, this landscape-led approach offers a hopeful, grounded alternative: a blueprint for building places where people can truly thrive.