8 minute read

Essential infrastructure: The role of nature across grey and green

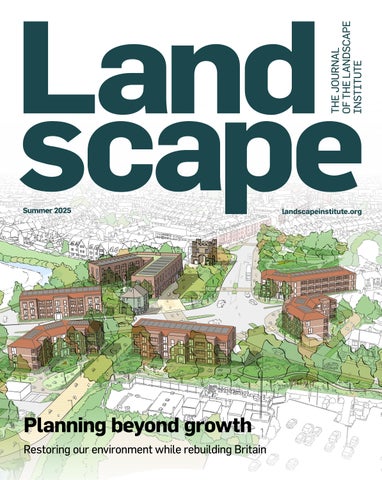

House development construction site in progress, aerial view UK. © iStock

The government’s ‘grey belt’ proposals show that while planning reforms could offer the potential for a strategic approach, whether nature is treated as essential or secondary to growth remains an unresolved issue.

The UK government’s proposals to designate ‘grey belt’ as areas of growth has led to a heated debate over their potential to deliver new homes. There has been a related concern that by allowing development, rather than local council objectives, to lead what happens in grey belts, the continuity of approach between grey and green infrastructure could be jeopardised. These debates have been further complicated by the publication of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill (March 2025). The bill calls for a renewed focus on regional spatial planning, and the creation of Nature Restoration Funds and Environment Development Plans to be led by Natural England, while ensuring that economic growth in the form of meeting housing targets is not compromised.

The promotion of this swathe of policy directives offers hope for the environment sector as it provides scope to plan strategically for nature. By linking the new proposals with Local Nature Recovery Strategies and the National Green Infrastructure Standards Framework, the government is establishing the scaffolding to embed environmental thinking at the centre of planning. Moreover, the positives created via the 2021 Environment Act and its Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) legislation provide a process through which strategic planning for nature can be actioned.

However, concerns remain regarding how these legislative changes map onto the ongoing drive for economic and housing development. It could be argued that meeting the 1.5 million new homes housing target runs counter to effective environmental planning. Furthermore, the proposals for grey belt have generated significant interest within this debate, with various bodies arguing that they offer a meaningful way to identify sites for development on previously developed land (PDL), while others see them as a stealth mechanism to build on green belt land. Both can be simultaneously true, depending on whether you take a development or environmental conservationist perspective.

This focus on growth and speed of decision-making in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill potentially moves the conversation away from detailed assessments of environmental quality and function, and instead towards a process of grey infrastructurefirst development. The landscape profession should therefore ask whether this is a significant shift in emphasis from the approaches to planning witnessed under successive governments between 2010 and 2024. The wording of the guidance associated with the bill suggests not, and that a nuanced approach to nature recovery may not be central to the government’s thinking. Instead, strategic planning for nature is proposed to replace more localised landscape-led thinking:

“To grow the economy and recover nature we need new tools and a new approach. We want to make better use of the millions of pounds that are spent each year on bespoke mitigation and compensation schemes, by using this money to fund strategic interventions that provide greater benefit for nature than the status quo. Through this approach we want to provide the necessary certainty for all parties that we will take consolidated, coordinated action to drive nature recovery whilst allowing vital development to come forward.”

While we might consider the proposed changes to be limited in how they locate nature in these discussions, there are potential areas of optimism. The presentation of grey belt as a mechanism to streamline debate regarding green belt development has merit. If grey belts are used strategically to deliver essential urban fringe and rural infrastructure, e.g. social housing or local amenities

(schools, transport hubs, medical facilities) rather than allowing wider development, then that could be seen as a positive. However, if grey belts morph into locations where ‘anything goes’ because brownfield land is being brought back into use, then protests will occur. Reflecting on what grey belts might mean within the planning reforms does however provide us with scope to consider (a) whether existing legislation is working and (b) how best to align these new proposals with existing planning structures.

First, the proposals for grey belt allow us to reconsider the value of green belt. Their sacrosanct position in UK planning policy has generated a polarised discourse of pro/anti-green belt rhetoric. Focusing on PDL and finding a renewed purpose for these spaces limits where development can be allocated, thus restricting incremental change in green belt and the associated arguments over release or protection. For those looking to protect the environment in its entirety, this offers some certainty in terms of where development can be located. However, it could also mean that planning restrictions, such as adherence to local character, could be undermined if grey belts are seen as development zones that are less constrained.

Second, the discussion of grey belt has, to some extent, reopened a conversation as to whether a nationwide assessment of green belts, their function and fulfilment of their five core characteristics is overdue. Since green belts were first established in the Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act of 1938 and the subsequent 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, there has been a limited attempt to analyse the functionality and quality of green belts across the UK. With the introduction of the grey belt, the time may be right to consider such an evaluation to ensure that high-quality places are protected, to redesignate low-quality places and create new areas of green belt.

Third, if grey belts are to be designated, then a structure needs to be put in place to ensure that they are developed to complement the surrounding area. This would consider grey belt as a social good rather than as a facilitator of widescale development. Thus, grey belts could be designated only for social infrastructure – housing, education, or medical facilities – rather than being market driven. This would provide councils with specific locations to deliver much needed infrastructure but would need to be balanced with the need to allow development in other areas of the green belt. Both options may be unpopular with local people, local planning authorities and developers.

Fourth, whatever happens around the proposals for green belt, a more considered approach to mapping the new legislation and guidance onto existing policy is needed. There is a concern, for example, that the complexity of delivering and monitoring BNG is leading to poor-quality landscape design and maintenance that is not aligned effectively with grey belt. These concerns increase if we start to explore how off-site mitigation may lead to poorer-quality developments when compared to on-site delivery. Moreover, how will the ongoing roll-out of Local Nature Recovery Strategies work with the proposals of the Nature Restoration Fund and what mechanisms are being instigated to ensure existing work is not usurped if the Secretary of State does not find the conservation measures favourable? There are also issues around Natural England to consider. For several years they have seen their budgets decrease, so what confidence is there that these new responsibilities can be delivered without a significant increase in funding and capacity to deliver the ambitious programme of work?

One way to roll up all these issues is by considering the natural environment as essential infrastructure and not simply as the location for development. If nature is given the same prominence as transport, housing and economic development, then the function of grey belts, Nature Restoration Funds and BNG becomes easier to administer, as conversation moves from being an either/or towards a ‘how do we deliver all these forms of infrastructure?’. Framing nature as essential infrastructure provides scope to ensure that the focus of policy strives to maximise environmental quality while also delivering socio-economic infrastructure. However, if we take a ‘development first’ approach that relies on meeting housing targets, then the effectiveness of BNG, the focus of development in grey belts, or the delivery of Environment Development Plans may be fatally compromised.

The UK government’s attempt to align nature with development is admirable but they have potentially fallen into the trap of a ‘growth before all’ rhetoric. To some extent, this neglects the value of the natural environment and locates it as a second-tier form of infrastructure. While the Environment Act, BNG and the Planning and Infrastructure Bill make significant concessions to nature, there remain questions over whether the government is placing nature at the heart of development policy – as essential infrastructure. It therefore remains an opaque area that requires further discussion if we are to ensure that nature-led policy is both promoted and adhered to.