5 minute read

All voices must be heard

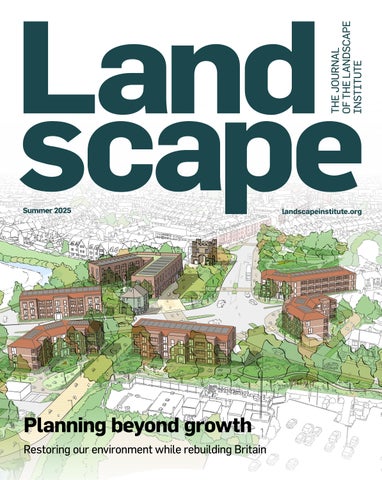

Engagement at Phoenix Road, Camden. © LDA Design

As planning teeters on the edge of potentially seismic reform, what role will communities play in shaping new development, and what impact will this have on nature, landscape and place?

Twenty-five years ago, the Blair government resolved to build on brownfield sites to revitalise ailing urban areas and strengthen deprived communities. Planning was a tool for structuring growth, transforming market conditions and delivering economic resilience, forging community cohesion and social wellbeing and enhancing the environment. The approach was bold and optimistic.

Local communities were closely involved: through design charrettes, school workshops, street parties and development ‘role play’ exercises. The aim was to achieve positive change for localities through an ‘urban renaissance’.

The 2008 financial crisis and coalition government brought everything to a halt. The subsequent over-reliance on the private sector and the lack of planning for strategic growth has resulted in more piecemeal development. There has also been less meaningful engagement, with communities increasingly seen as a problem rather than enablers of positive change.

Months into a new government and there’s renewed ambition for growth, brought about by planning reform that is focused on higher-tier plan-making, strategic environmental mitigation and fast-tracked delivery. So, what does this mean for community involvement? So far, there have been early alarm bells, with ministers warning that neither democracy nor nature should get in the way of growth. The stated intention to remove the statutory requirement to consult as part of the pre-application stage for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects will speed up a process that currently takes far too long. Will it also cut local people out of the early stages or allow for engagement to be managed in a less restrictive way?

It is true that most design and planning professionals share the government’s frustration with the way that minor issues can be misunderstood or misrepresented and used to stall development that could otherwise benefit a locality. But that does not mean community engagement should be restricted or dismissed. Indeed, the time has come to not only recognise its value again, but resource its expansion as well.

What is needed now is an increased focus on the widest positive impacts that can be achieved through well-planned and designed growth that works with, and for, nature, landscape, community and the economy. Involving communities is as important as ever to getting good things done.

A large part of the planner’s role is knowledge sharing, to foster well-informed opinions. This includes helping people to understand planning processes, so they start to ask the right questions about any proposal on the table. Is it upholding the development principles? Does it meet the design code? How can investment in growth protect and enhance local assets? Then people can see which aspects of a proposal are not negotiable and where the opportunities lie. All this moves everyone far beyond simply discussing the principle of development and basic mitigation. And none of this need delay growth.

The proposed planning reforms provide an opportunity to be bold and optimistic again, re-establishing the roles of planning and design in delivering not just development, but also development that brings about the changes we need to see for communities, our economy and the environment. This includes a more strategic approach to environmental delivery, and the emerging prospect of a coordinated National Spatial Plan, which would incorporate an understanding of land assets to organise growth and inform Spatial Development Strategies (SDSs).

The SDSs will set the agenda for growth and strategic environmental delivery, and the redevelopment of brownfield sites may be simplified to enable faster delivery. Both represent opportunities to spark cross-community conversations about the type of place, infrastructure and natural environment needed in the future. Run well, with adequate funding, SDSs and brownfield strategies should provide impetus and scope for local people to positively influence the agenda, acquire an improved understanding and reduce adverse reactions to subsequent local plan and planning applications.

The proposed planning reforms provide an opportunity to be bold and optimistic again

One thing is clear. We must keep lobbying hard for all voices to be heard. Large-scale development and urban regeneration often take decades to come to fruition. We therefore need to understand and factor in the needs and aspirations of local children and teenagers, young professionals, and young families in particular.

This should go hand-in-hand with encouraging community asset stewardship, which at its best is socially responsible, environmentally aware and highly entrepreneurial. When community organisations take on this role, they are often far more entrepreneurial than traditional management companies, accessing new sources of funding and reinvesting profits. The Chichester Community Development Trust is a great example and a community asset in its own right.

Clearly, community engagement and taking people on the development journey is critical to good-quality placemaking and better environmental management. Far from being the blockers to development, local people hold the secrets of a place, what makes it special and what will help to deliver its best future life. We need to trust them and hear their views.