CATALOG

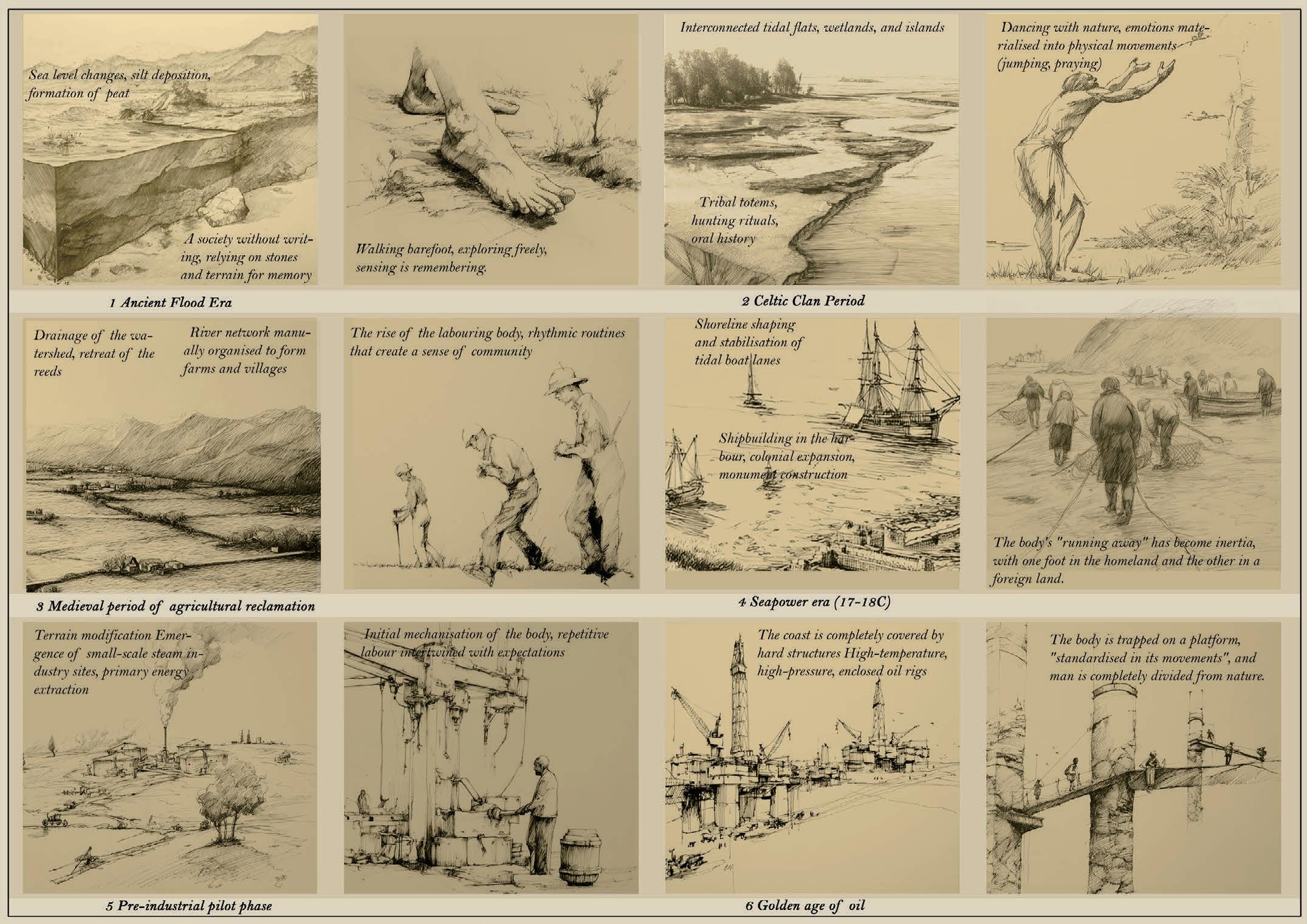

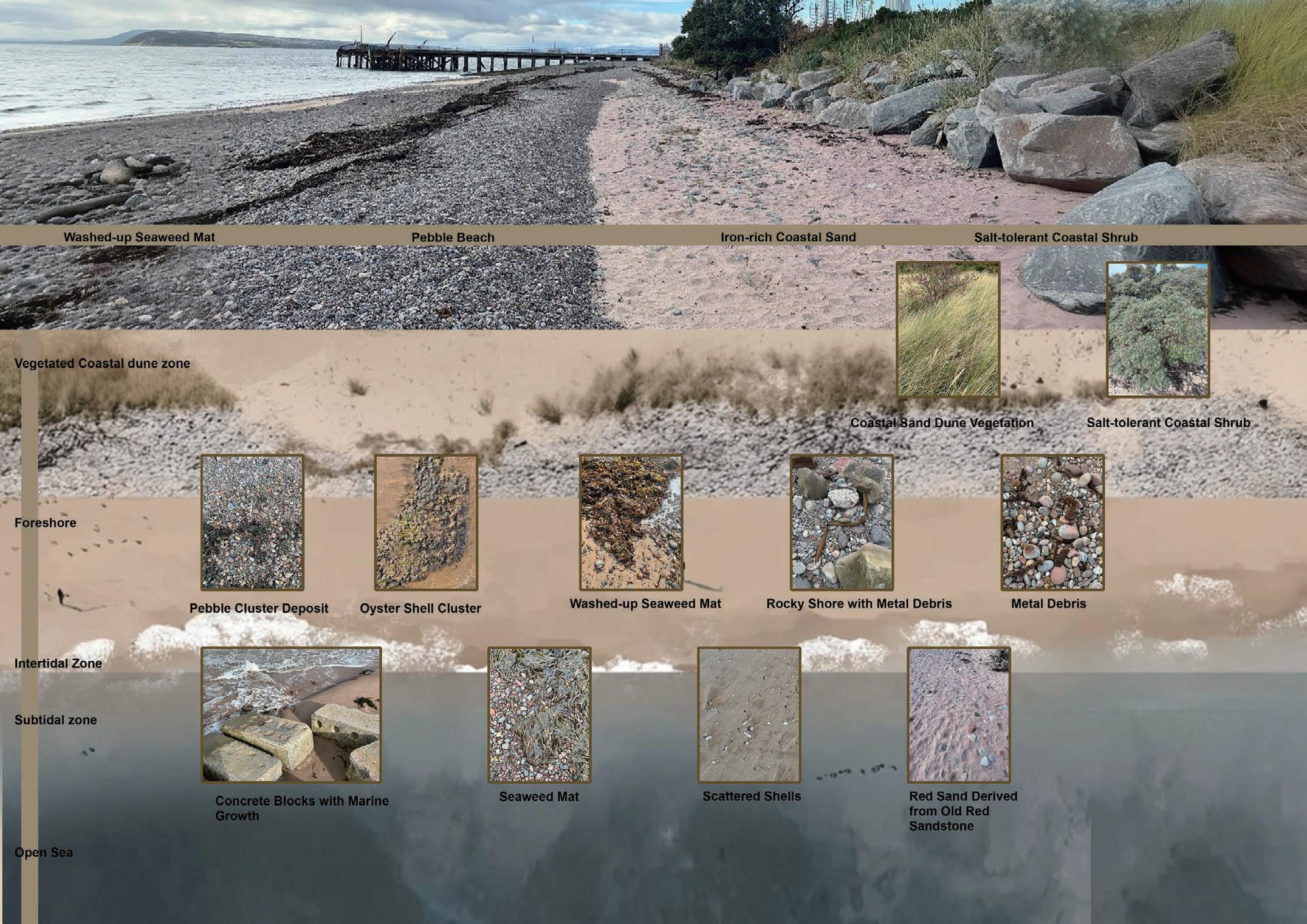

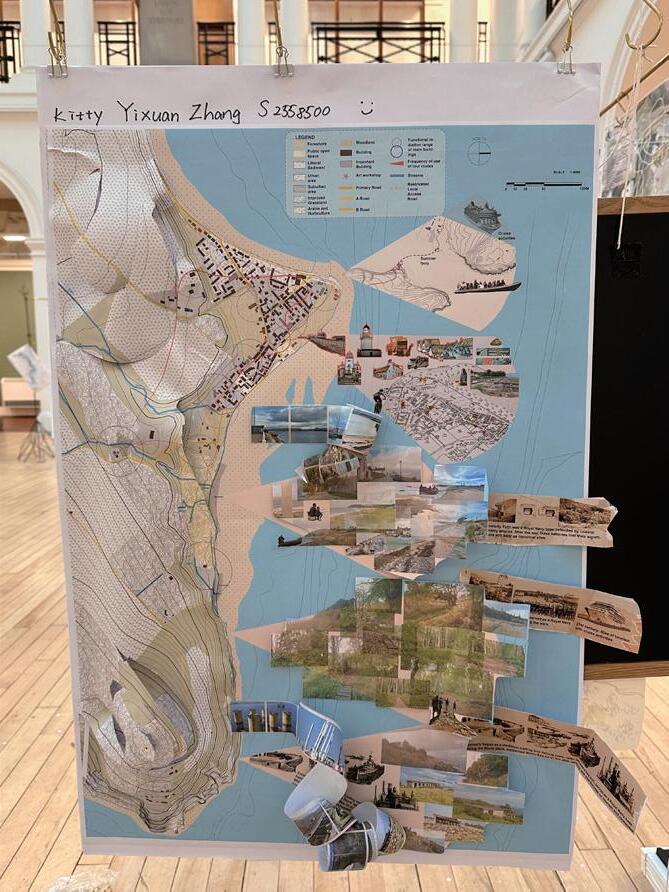

CHAPTER 01. An archaeologist's journal

A sensory excavation through landscape history, tracing memory with each step.

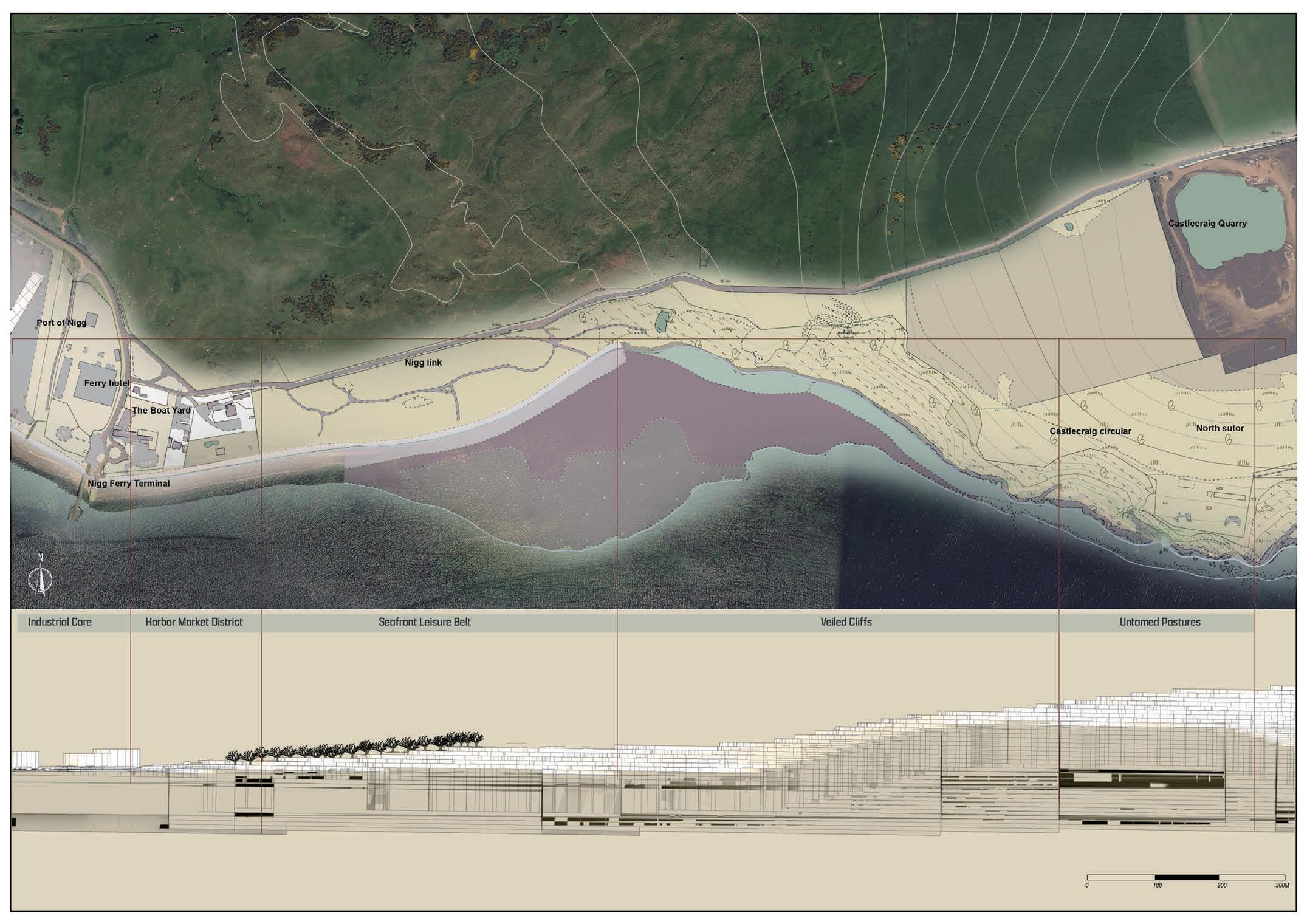

CHAPTER 02.

Weaving Memory and Matter: Site Strategies

Strategies woven through walking, sensing, and rebuilding—reactivating the post-industrial site through embodied design.

CHAPTER 03.

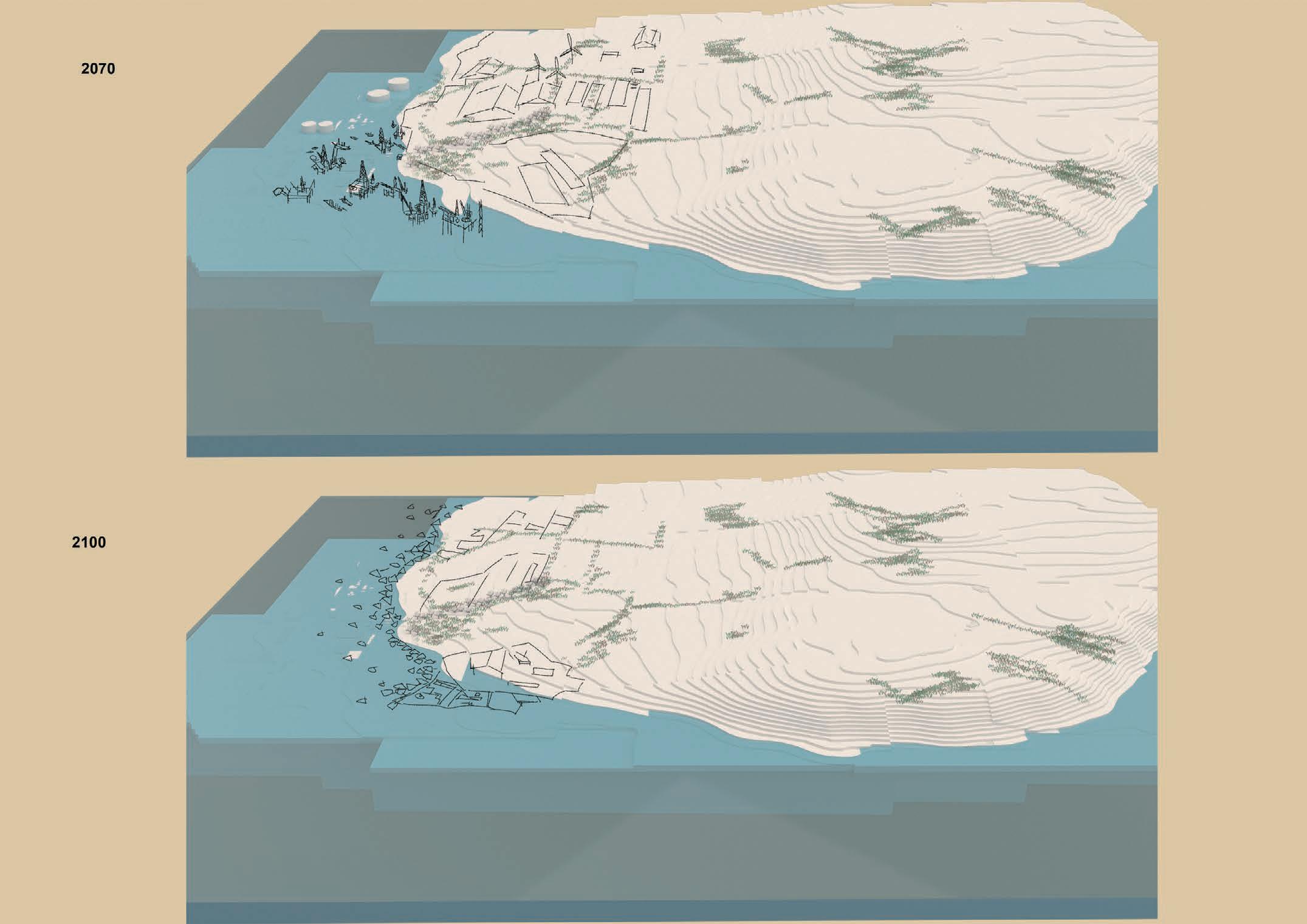

Projected Grounds: Design Outcomes Across Time and Emotion

Designs unfolding through masterplans, material systems, and sensory experiences—mapping emotion across time.

CHAPTER 04. Nomadic Workbook & References

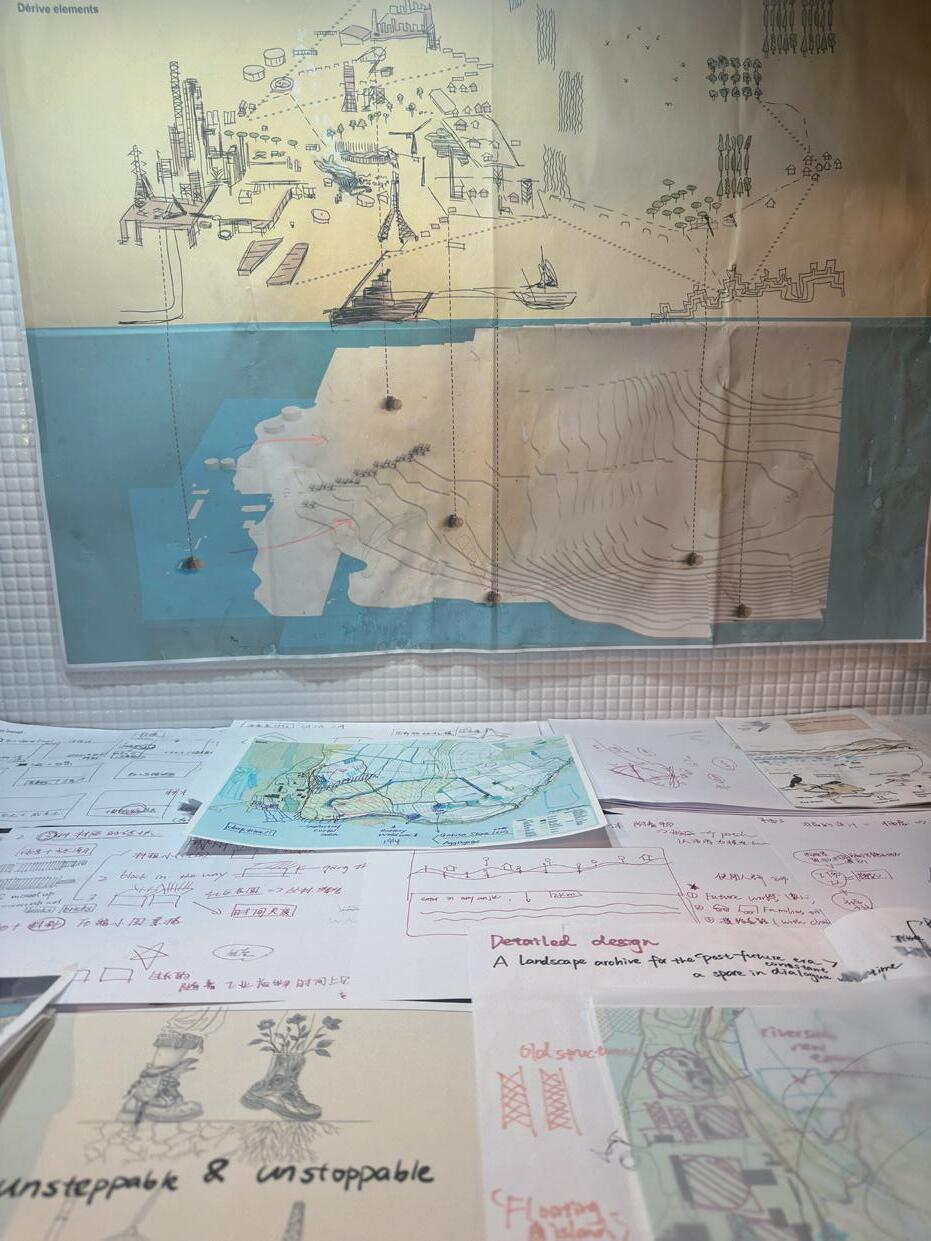

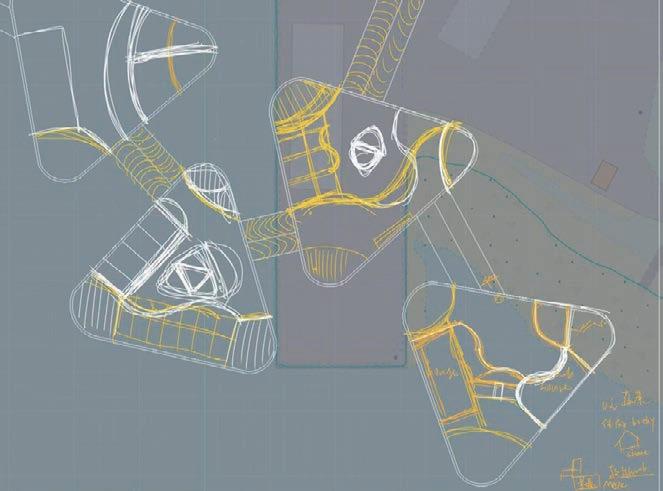

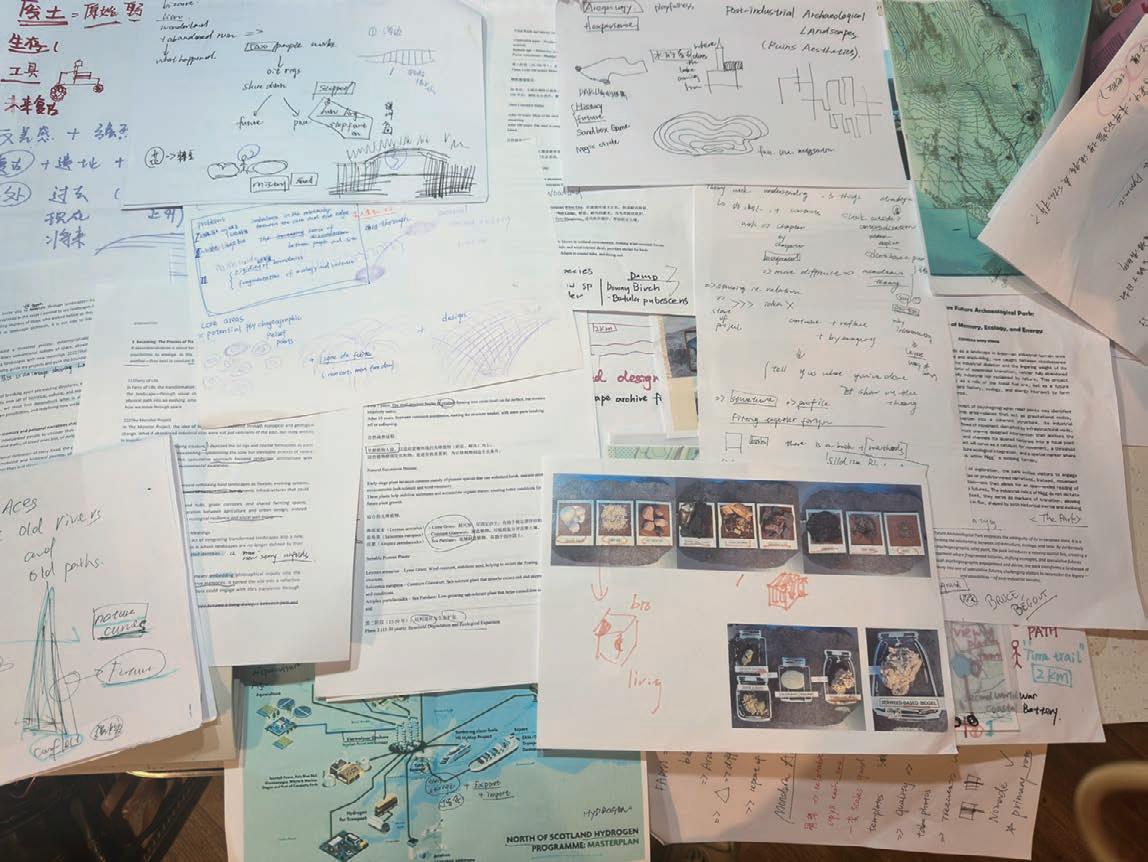

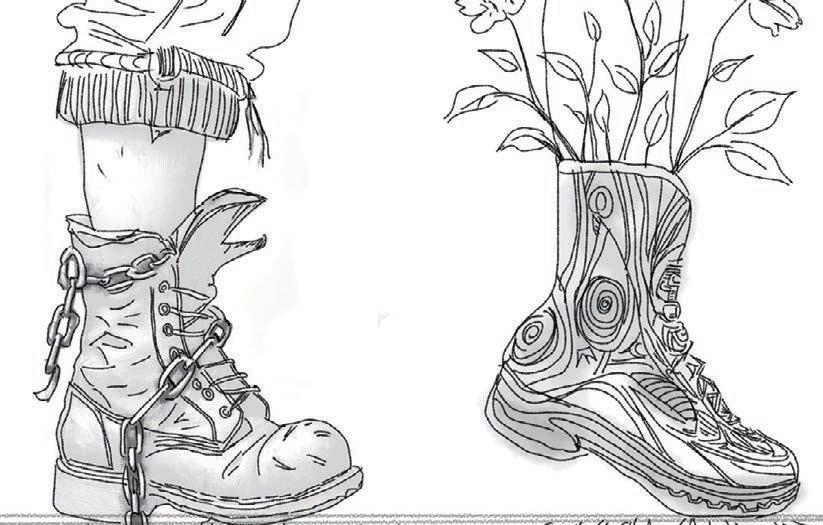

Sketches, material tests, process mapping, and theoretical references—tracing the making of a nomadic landscape.

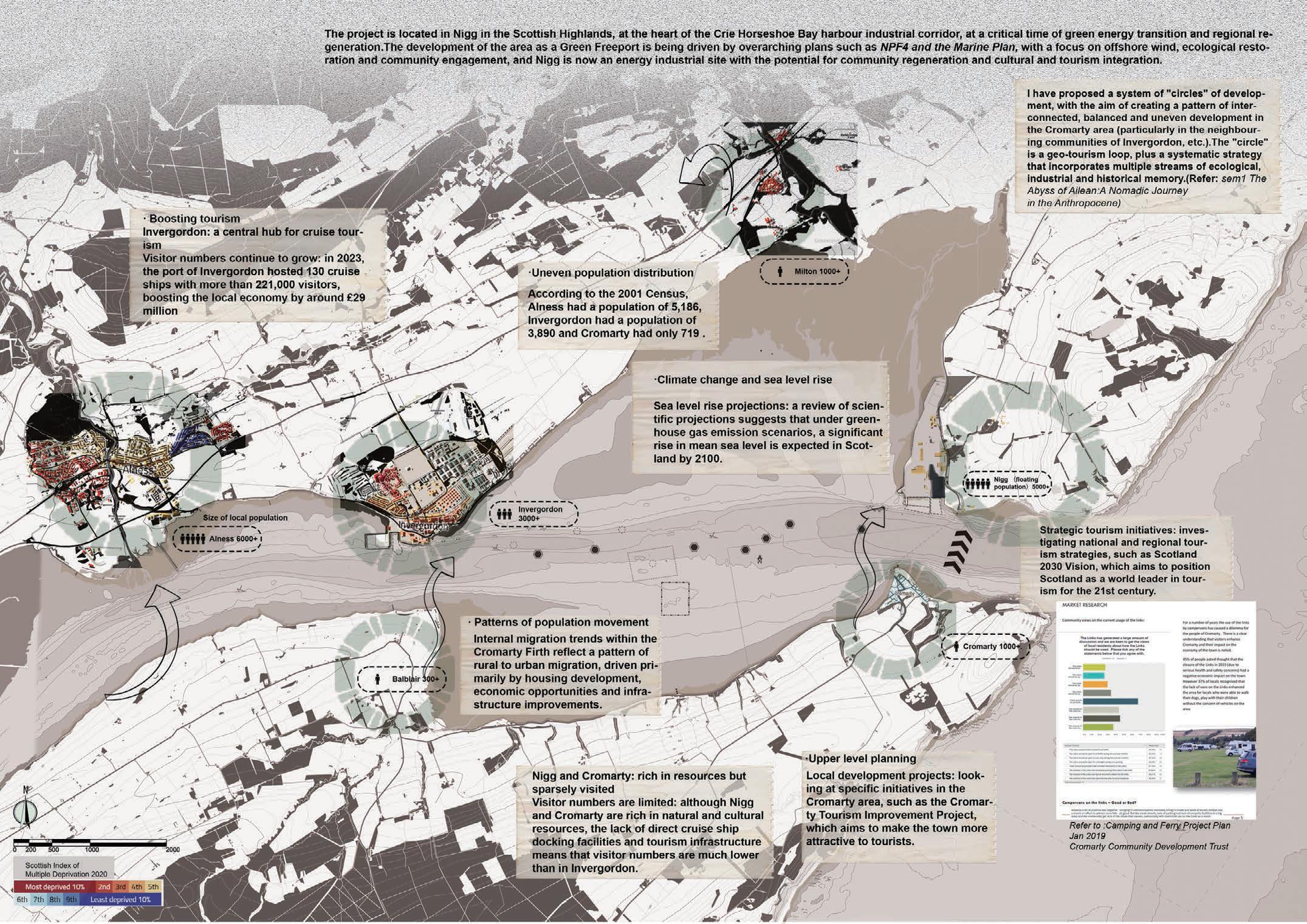

CHAPTER 1

One Future Nomadic Archaeologist’s Diary, Year 2075

What Is Nomadism in Landscape Design?

Traditionally, nomadism emerged as a human adaptation to the arid grasslands, where communities developed a mobile lifestyle characterized by horseback herding and seasonal migration in pursuit of water and pasture.

Over time, the concept of nomadism transcended its original socio-economic context, evolving into a philosophical framework for understanding space, identity, and movement. French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, alongside Félix Guattari, introduced the notion of "nomadic thought," emphasizing decentralization, fluidity, and deterritorialization. They contrasted "smooth space": open, continuous, and dynamic, with "striated space," which is structured, hierarchical, and fixed.

In contemporary landscape architecture, the principles of nomadism have been reinterpreted as a design strategy that prioritizes temporal experiences, decentralized engagement, and embodied perception.

Moving away from rigid zoning and static functions, nomadic landscapes invite users to traverse, sense, and adapt to their surroundings.

Such designs embrace unfinishedness, cyclical rhythms, and the evolving relationship between people and land, reflecting a shift towards flexibility and sustainability in addressing the challenges of modern society.

Rather than imposing fixed functions or rigid zoning, a nomadic landscape invites people to walk, sense, and adapt. It values unfinishedness, cyclical rhythms, and the fluid ways we relate to land over time.

Nomadism in My Landscape Practice

As a landscape designer, I understand nomadism not merely as movement across space, but as a way of thinking—an approach rooted in decentralization, slowness, and bodily presence. Nomadism, to me, means designing with fluidity over fixation, experience over form, and temporal rhythms over static boundaries.

Rather than organizing space through rigid zones, I see nomadism as a method of unfolding meaning through walking, sensing, and encountering—where the land is not mastered, but slowly read.

In this project, I translate this idea into three spatial strategies:

1 using walking to stitch memory across fragmented ground,

2 enabling sensory immersion as a design tool,

3 and reactivating post-industrial ruins through adaptive reuse and participation.

Here, nomadism becomes more than theory—it becomes a way to rebalance spatial inequality, reframe lost ecologies, and invite renewed belonging on a land once dominated by extraction.

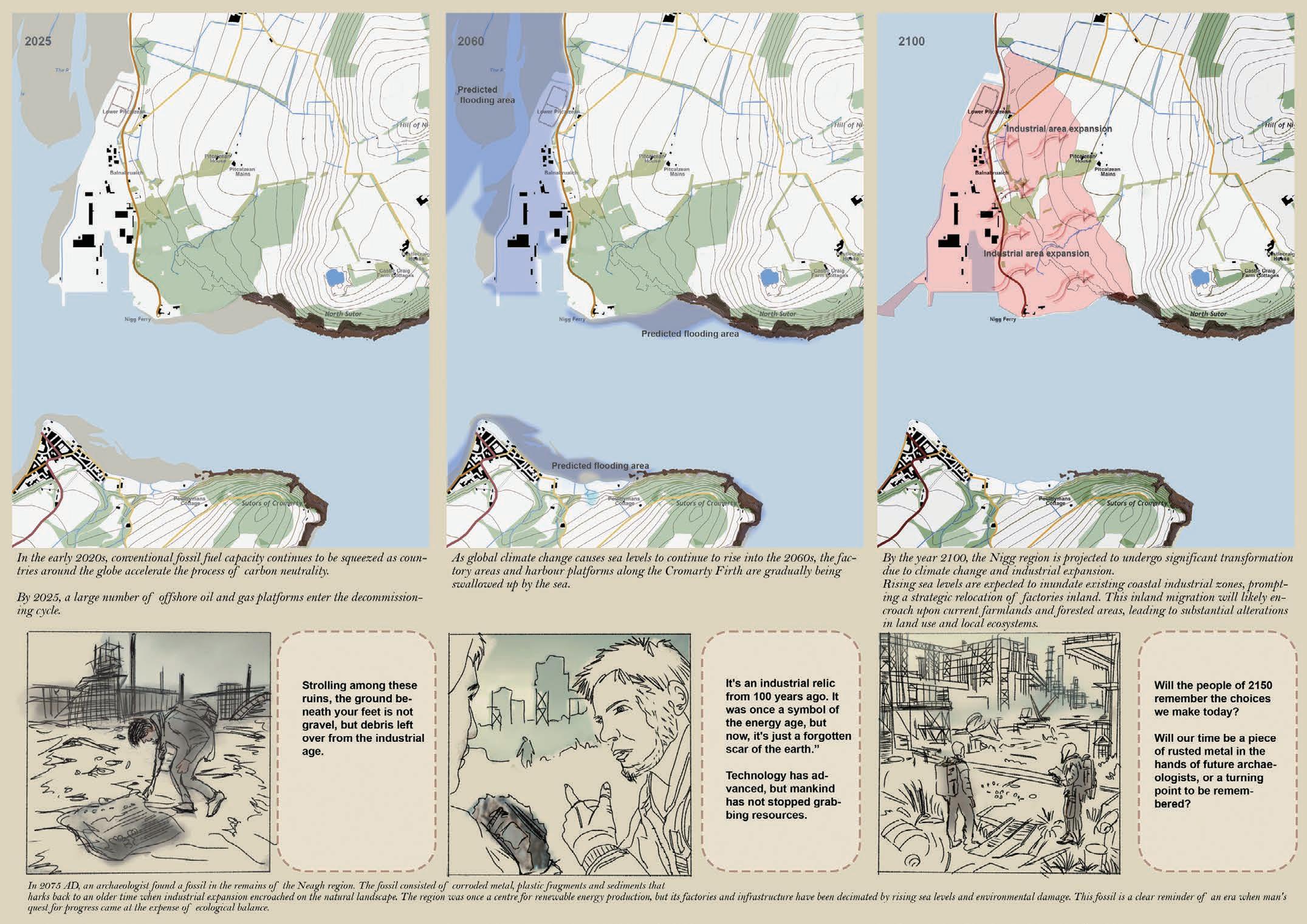

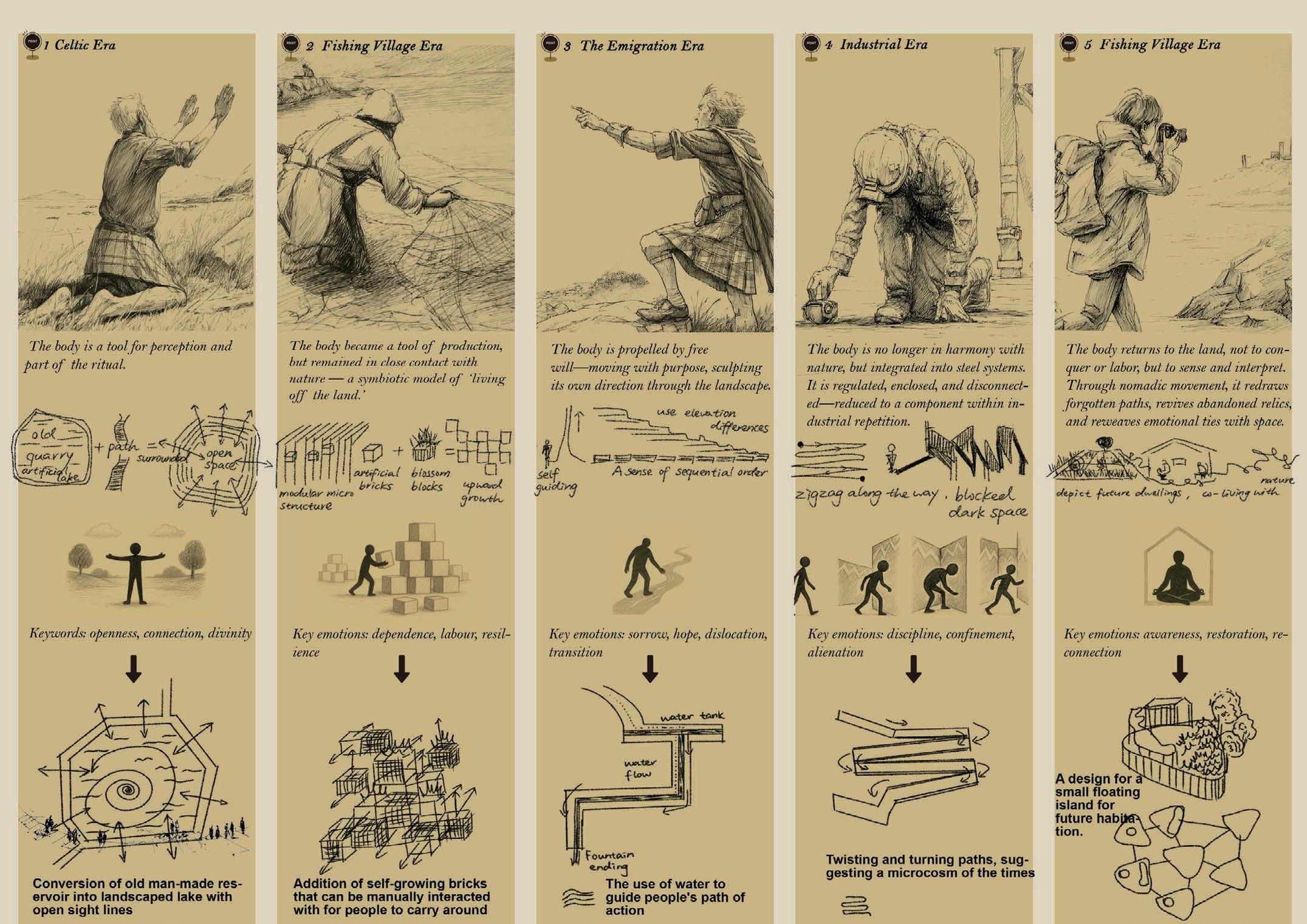

CHAPTER 3

Projected Grounds: Design Outcomes Across Time and Emotion

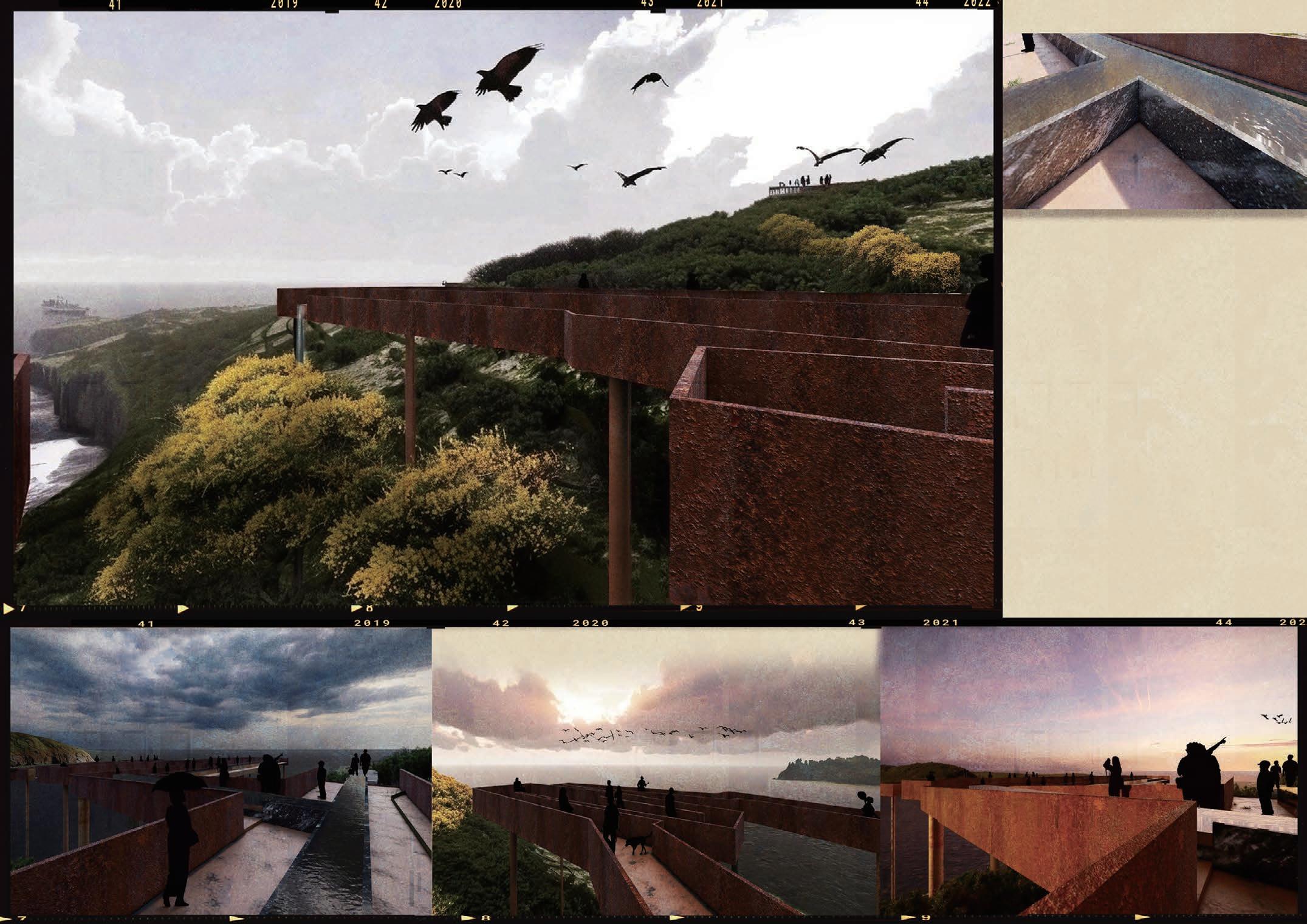

World War II Battery Ruins memorial bridge

Detailed design site 1

The World War II Battery memorial bridge is designed as an emotional journey—one that invites visitors to physically and psychologically experience the weight of the post-industrial labor era.

Inspired by the constrained, repetitive conditions of wartime industry and offshore oil labor the bridge takes on a compressed, folded form, echoing both pressure and perseverance.

Its structure is constructed from repurposed components of a decommissioned oil rig, embedding the memory of the region’s industrial past into the bridge’s very body. Spanning between two commemorative points, the bridge offers both a panoramic view of the Cromarty Firth and a contemplative passage that connects collective memory with lived landscape.

My design uses flowing water to guide visitors both visually and emotionally.

A gently sloping bridge leads to a still pool, symbolizing memory and reflection.

As the path continues, water becomes a narrative thread, drawing people deeper into a space where history and ecology meet.

At the end, a powerful waterfall marks the climax—serving as both a moment of remembrance and a striking reminder.

The imprint of scrap steel

The hillsides burst with vibrant gorse in bloom.

Sea Cave Adventure Cliff rock climbing

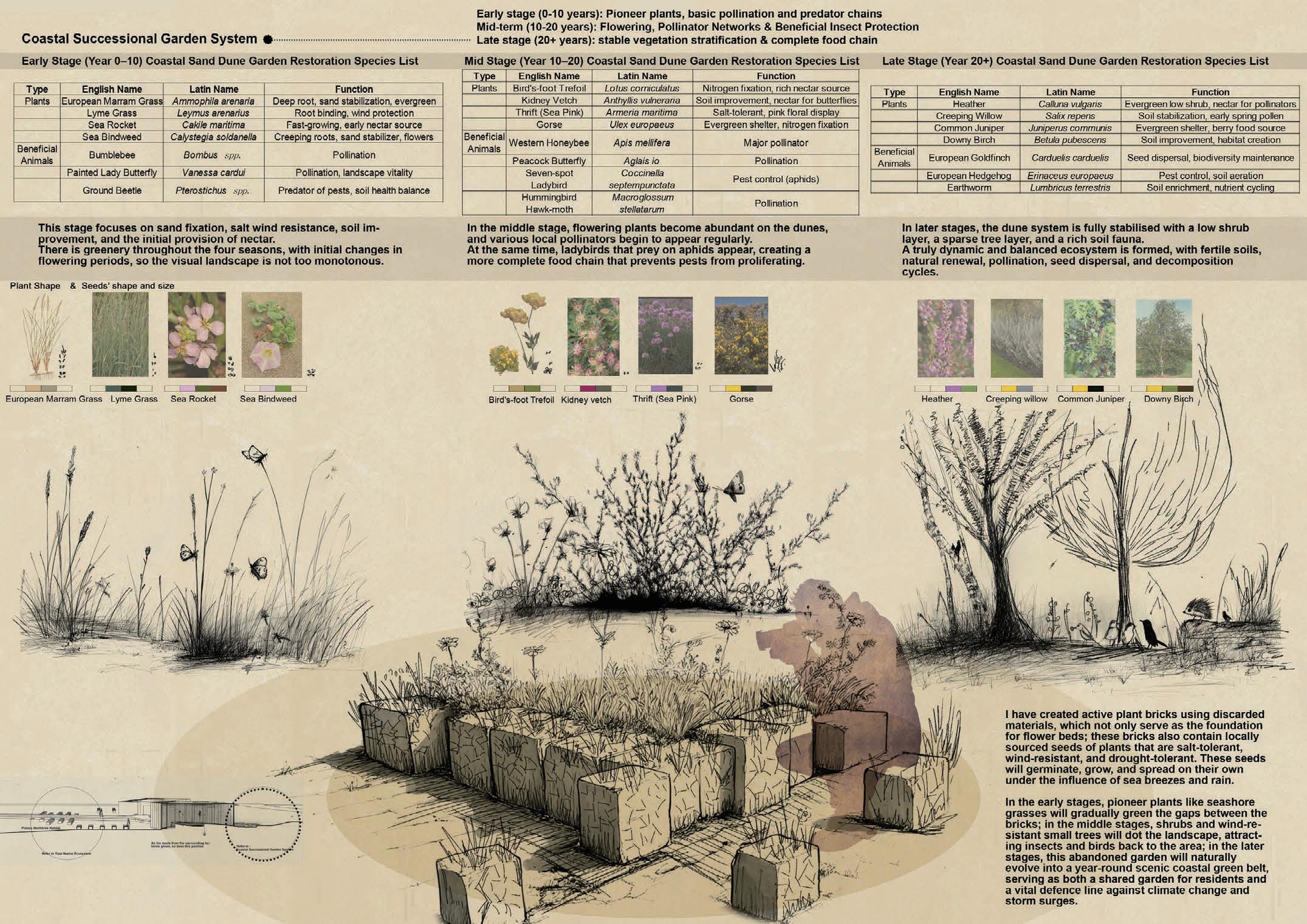

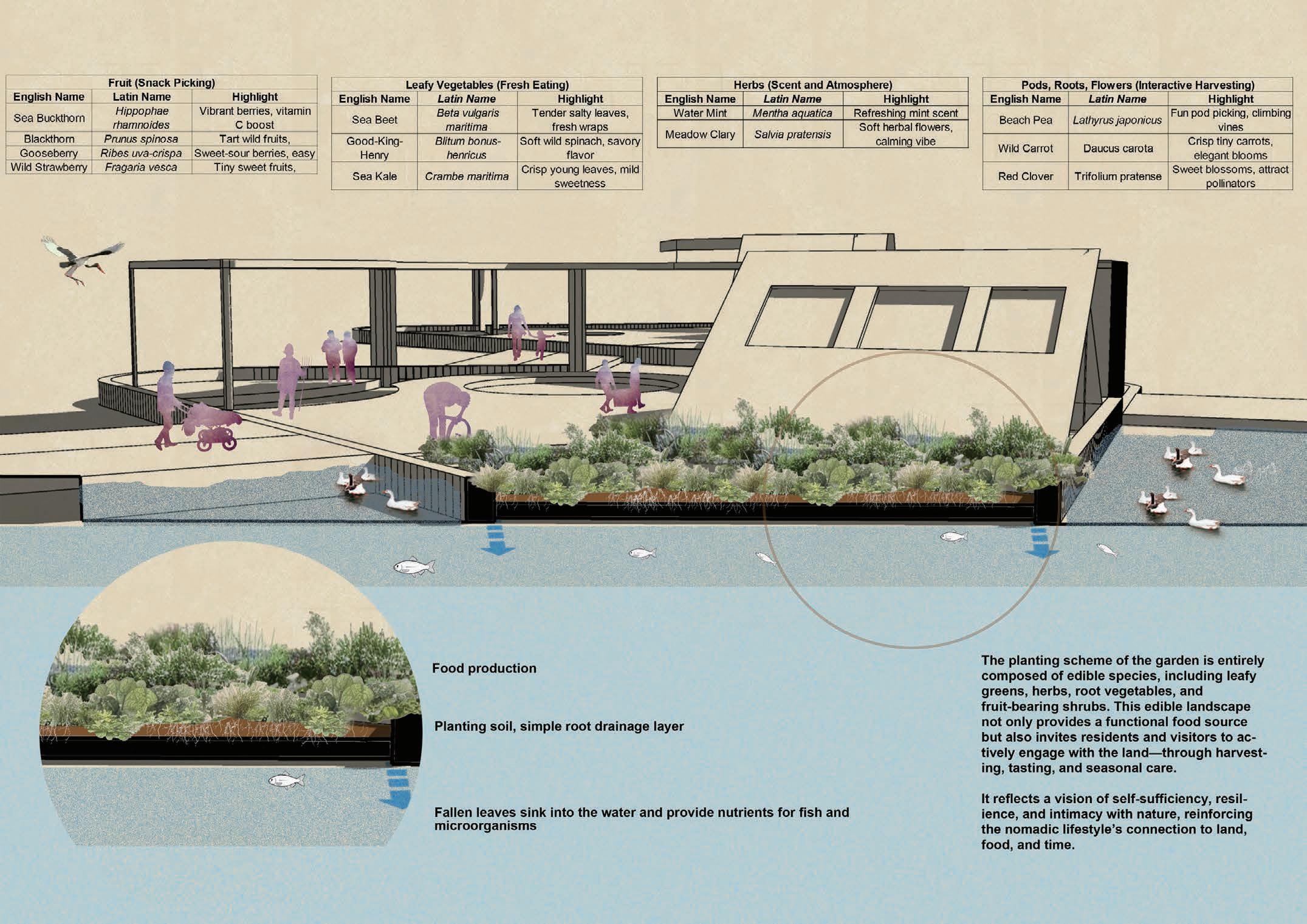

Site 2 regenerative lab strip

Detailed design

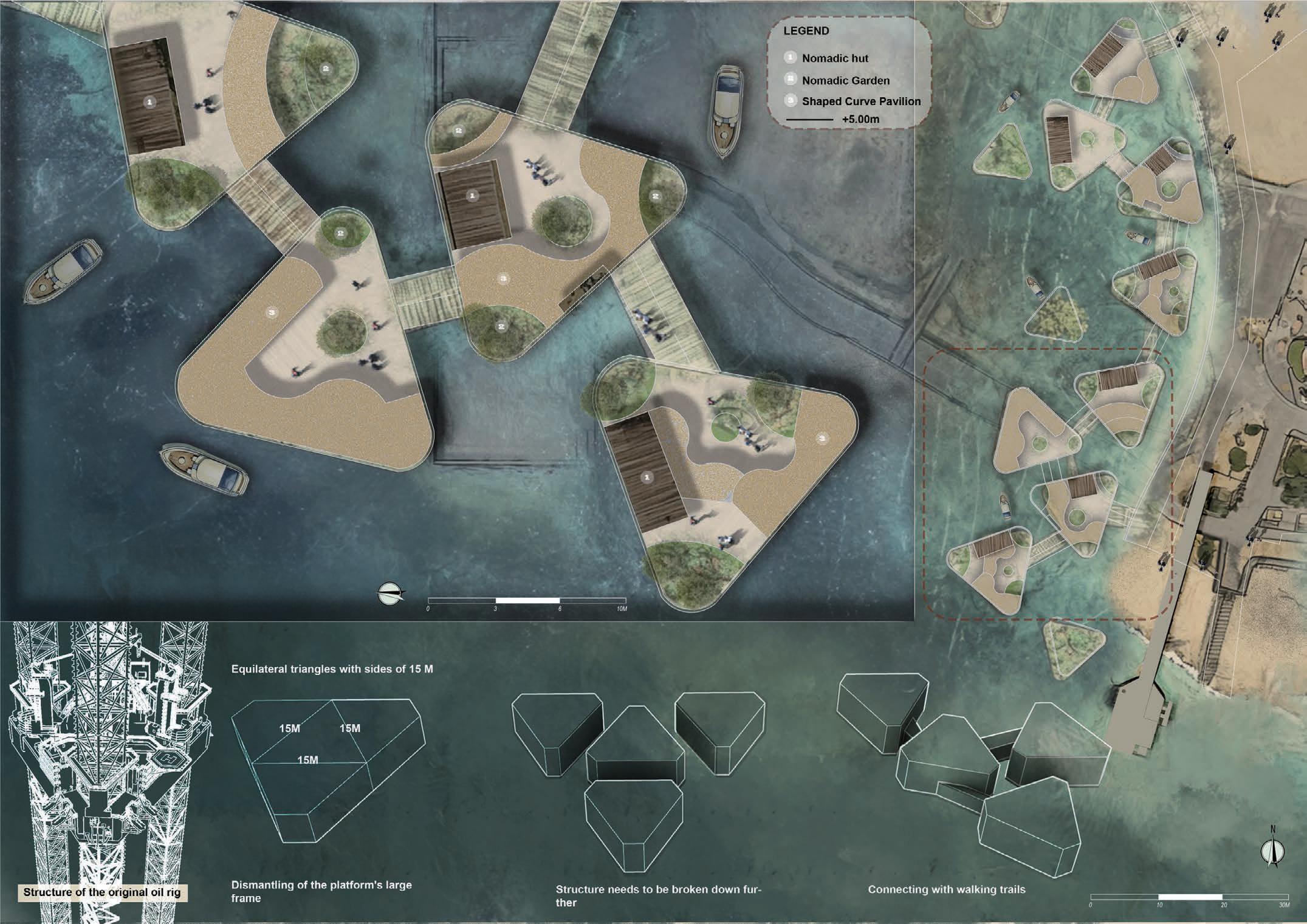

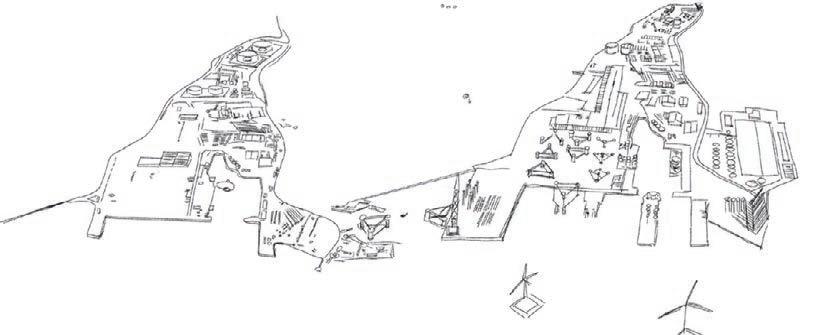

Floating Island Design Renderings

Floating Island Design Renderings In

CHAPTER 4

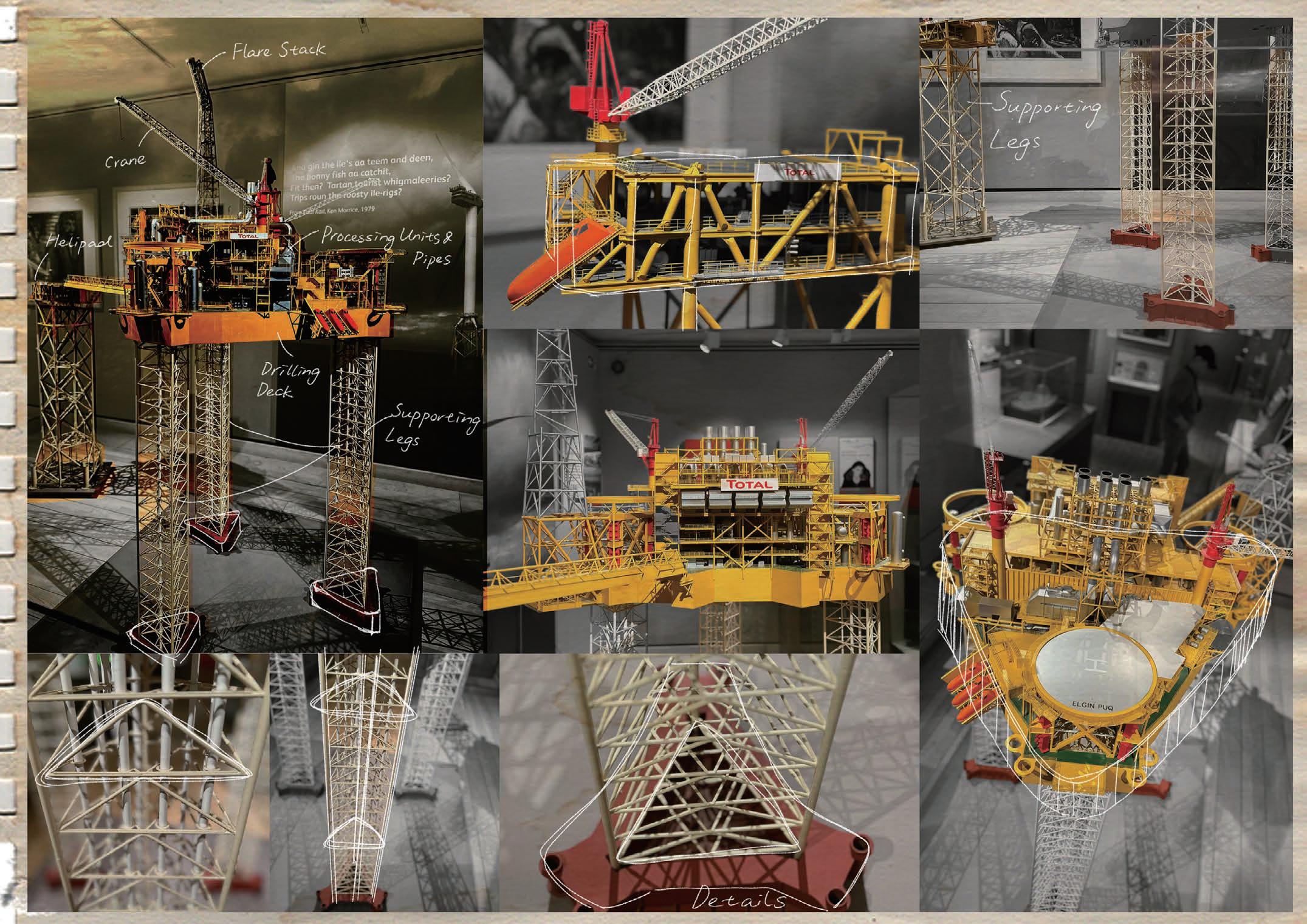

Nomadic Workbook & References

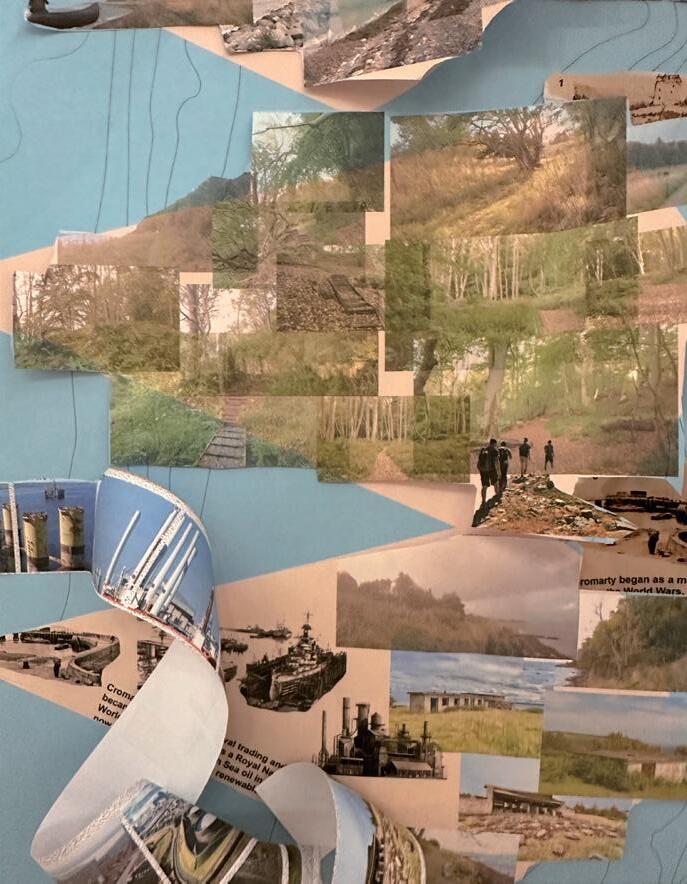

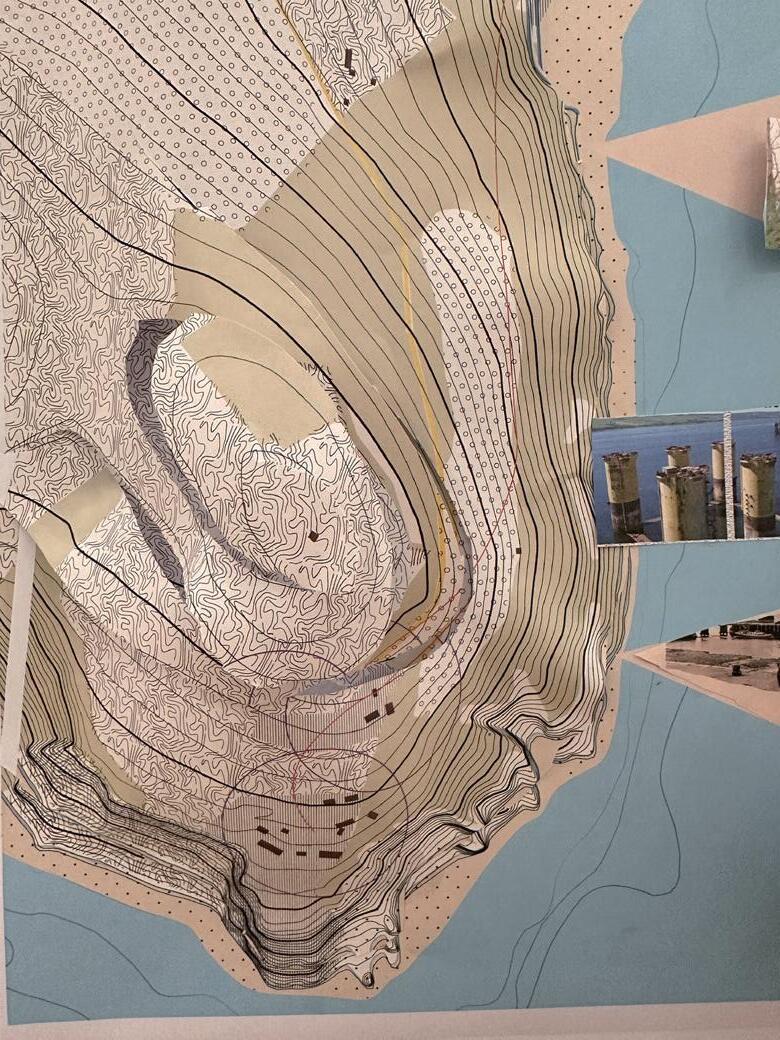

For this exercise, used the effect of a film reel to observe the narrative sensations of the site.

The main objective is to make people feel the presence and the topography of the site, as well as the contrasts and differences between the categories of landscape elements.

From

Gorse Flowers all over the mountains in north sutor.This flower is very fragrant and visually spectacular.

time to time, show how feel about a venue through the lens of immersive cinema to touch, to listen, to feel

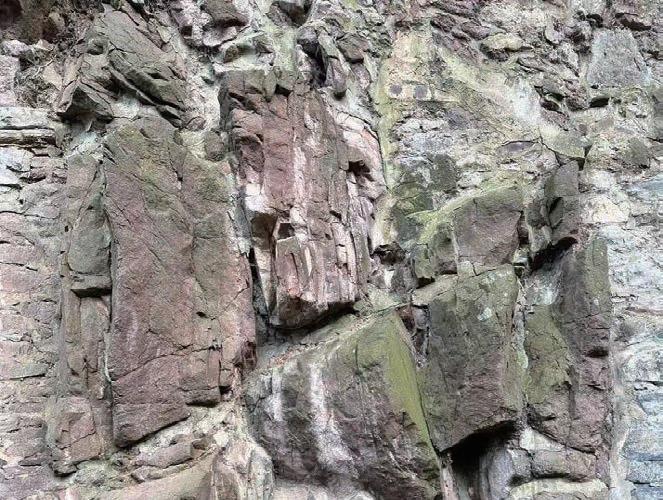

Different rock formations, a place with a lot of red sandstone. In the portfolio observed these giant boulders,they had a great fun outdoor adventure!

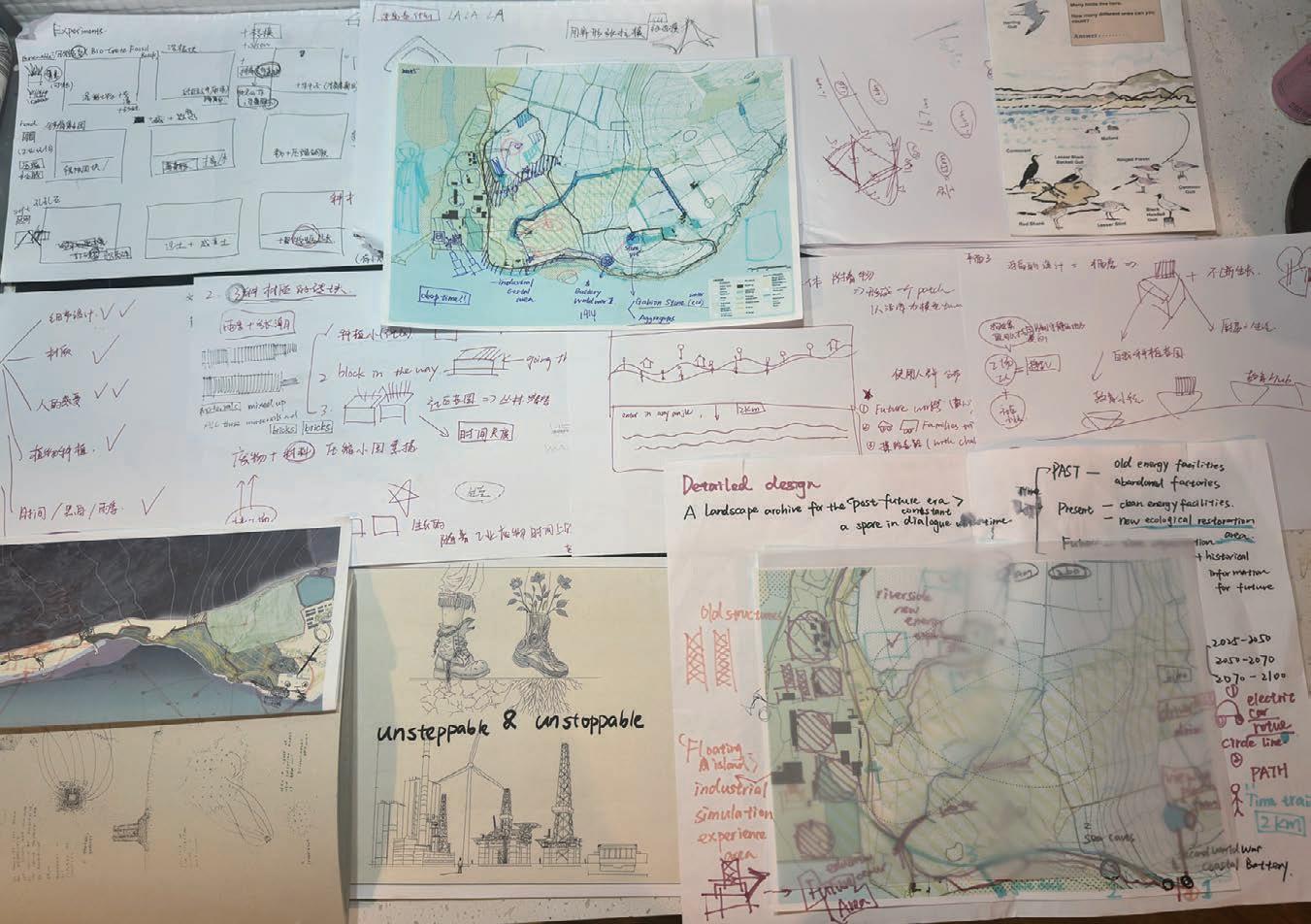

For each design, prefer to take a blank piece of paper and draw what I'm thinking about

Similarly to inspiration, I used to make some line drawings; these are rough line drawings as opposed to the sketches in the portfolio which are carefully drawn

Ashworth, G.J., 2008. Heritage, memory, and the politics of identity: A review. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(3), pp. 257-271.

Basso, K.H., 1996. Wisdom sits in places: Landscape and language among the Western Apache. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Bataille, G., 1985. The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy. Zone Books, New York.

Baudrillard, J., 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Borden, I., 2002. The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy. In: I. Borden, J. Kerr, and J. Pivaro, eds. The Politics of Public Space. Routledge, London, pp. 124-135.

Braverman, I., 2012. Soil, or a Critical Examination of the Politics of Ecosystems. Environmental Politics, 21(1), pp. 39-61.

Chipperfield, D., 2017. The Landscape of Post-Industrialization: A Design Manifesto. Architectural Journal, 34(7), pp. 45-59.

Coles, A., 2005. Ecology, Landscape and the Nomadic City. Journal of Urban Ecology, 2(3), pp. 9-15.

De Landa, M., 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. Continuum, London.

Gandy, M., 2006. Landscapes of Disaster: The Production of Nature and the Limits of the Urban. Urban Studies, 43(2), pp. 311-325.

Graham, B., 2002. In a Land of Decay: The Rise of Post-Industrial Landscapes. In: G. Ashworth, B. Graham, and J. Tunbridge, eds. Placing Memory: A History of the Cultural Landscape. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 157-183.

Harvey, D., 1989. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Blackwell, Oxford.

Hélénon, M., 2014. Nomadic Architecture: A Philosophical Approach. Journal of Architectural Theory, 13(1), pp. 22-34.

Ingold, T., 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description. Routledge, London.

Kwon, M., 2002. One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Leach, E., 2012. Architecture of Memory: Reconsidering the Past Through Nomadic Design. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 21(5), pp. 50-64.

Lefebvre, H., 1991. The Production of Space. Blackwell, Oxford.

Lippard, L.R., 1997. The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society. New Press, New York.

MacDonald, K., 2009. Ecological Restoration and Post-Industrial Landscapes: Methodologies for Cultural Repair. Environmental History, 14(1), pp. 75-94.

Massey, D., 1995. The Spatial Construction of Culture and Identity: Territorialization and Identity Politics in Postmodernity. In: D. Massey and J. Jess, eds. The Geographies of Difference. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, pp. 109-124.

Miller, D., 2010. Materiality. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

Mumford, L., 1961. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. Harcourt, New York.

Pallasmaa, J., 2012. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Wiley, Chichester.

Rancière, J., 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. Continuum, London.

Schama, S., 1995. Landscape and Memory. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Schuster, J., 2017. Ecologies of Abandonment: Memory, Art, and the Transformation of Post-Industrial Landscapes. Ecological Futures Journal, 29(2), pp. 210-225.

Tuan, Y.F., 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Williams, R., 1985. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Zukin, S., 1995. The Cultures of Cities. Blackwell, Oxford.

Zölitz, M., 2013. Spectral Landscapes and Industrial Remains: The Aesthetics of Decay. Art and Culture Review, 21(6), pp. 89-101.

Energy Voice, 2021. The History of the Nigg Yard. Available at: https://www.energyvoice.com/renewables-energy-transition/19530/the-history-of-the-nigg-yard/

The Nigg Stone - Highland Pictish Trail, 2021. Available at: https://www.energyvoice.com/renewables-energy-transition/19530/the-history-of-the-nigg-yard/

RSPB, n.d. Nigg Bay: an award-winning refuge for birds. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/days-out/reserves/nigg-bay

Cromarty Firth, n.d. Coastal Regeneration of Cromarty Firth. Available at: https://marine.

Cromarty Firth, 2021. What does the future hold for subsea pipeline tie-ins?. Available at: https://www.energyvoice.com/renewables-energy-transition/19530/thehistory-of-the-nigg-yard/

BBC News, 2021. Oil rigs detained in Cromarty Firth will now be dismantled legally. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-62688442

Cromarty Firth, 2021. Nigg Bay Coastal Re-alignment. Available at: https://www.nfm.scot/case-studies/nigg-bay-coastal-re-alignment

Cromarty Firth, n.d. Tide Times, High & Low Tide Table. Available at: https://www.tideschart.com/United-Kingdom/Scotland/Highland/Cromarty-Firth/

The Perimeter, 2021. Day 333: Alnessferry to Gallow Hill – The Oil Rig Graveyard. Available at: https://www.perimeter.org/articles

WorldPop, 2021. Cromarty Firth Ecological Data. Available at: https://www.worldpop.org/

National History Museum, n.d. What is the Anthropocene?. Available at: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-the-anthropocene.html

Domestika, 2021. Proximity Island: A Nomadic Future. Available at: https://www.domestika.org/en/projects/1391443-proximity-island-a-nomadic-future

Rewilding Europe, 2021. Rewilding the Highlands: A Vision for the Future. Available at: https://rewildingeurope.com/rewilding-the-highlands/

The Guardian, 2020. The Decline of Industrial Spaces: Can They Be Saved?. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2020/aug/12/the-decline-of-industrialspaces-can-they-be-saved

Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter, 2021. Chemin des Carrières, France. Available at: https://www.archdaily.cl/cl/930987/chemin-des-carrieres-reiulf-ramstad-arkitekter/5def0e 273312fdecff000079-chemin-des-carrieres-park-walk-reiulf-ramstad-arkitekter-photo

Scenario Journal, 2021. The Performative Ground: Ecological Restoration and Public Spaces. Available at: https://scenariojournal.com/article/the-performativeground/

Energy Voice, 2020. Post-Industrial Regeneration of Scotland’s Coastal Zones. Available at: https://www.energyvoice.com/renewables-energy-transition/16283/postindustrial-regeneration-scotland/

British Ecological Society, 2021. Restoration of Industrial Sites: Lessons Learned. Available at: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/restoration-industrial-sites/

World Landscape Architecture, 2021. Post-Industrial Landscape Projects: Case Studies and Insights. Available at: https://worldlandscapearchitect.com/ CityLab, 2021. How to Design the Post-Industrial City. Available at: https://www.citylab.com/design/2021/06/how-to-design-the-post-industrial-city/

The New York Times, 2020. Reimagining Post-Industrial America. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/10/us/post-industrial-america-reimagining.html

The Ecologist, 2021. Restoring Nature in Post-Industrial Landscapes. Available at: https://www.theecologist.org/

Designboom, 2021. Nomadic Urbanism: Sustainable Cities and Temporary Living Spaces. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2021/04/12/nomadic-urbanismsustainable-cities/

Building Green, 2021. Post-Industrial Green Spaces and Sustainability. Available at: https://www.buildinggreen.com/

Green Building Council, 2021. Re-Imagining Industrial Landscapes for Sustainable Futures. Available at: https://www.gbca.org.au/

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 2021. Post-Industrial Imaginaries: Artistic Interventions in Abandoned Spaces. Available at: https://www.moma.org/

Landscape Institute, 2021. Designing for a Changing Climate: Landscape and Ecological Repair. Available at: https://www.landscapeinstitute.org/

Urban Sustainability Journal, 2021. Sustainable Urbanism and the Future of Post-Industrial Spaces. Available at: https://www.urban-sustainability.org/

Rewilding Britain, 2021. Reviving Post-Industrial Landscapes through Ecological Restoration. Available at: https://rewildingbritain.org.uk/

WorldPop, 2021. Cromarty Firth Ecological Data. Available at: https://www.worldpop.org/