Timothy Love

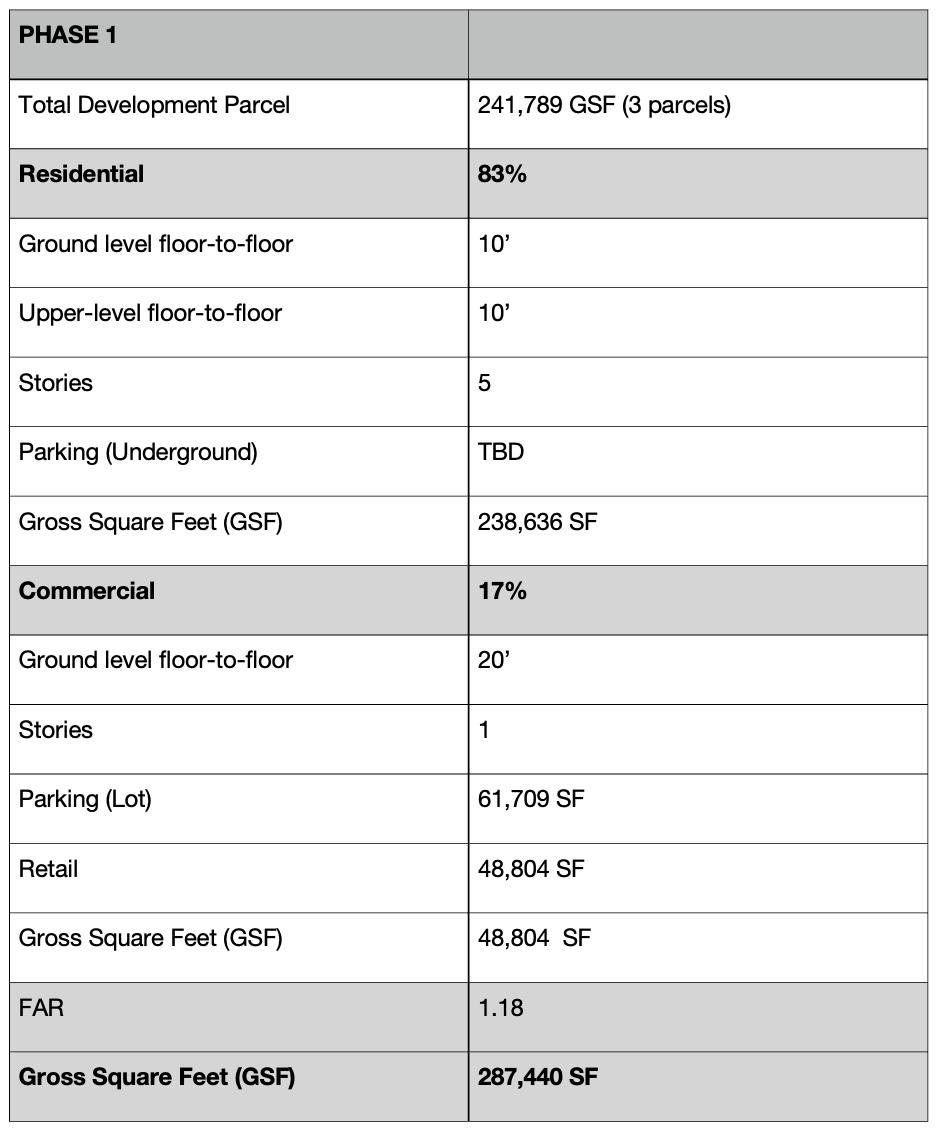

Design For Real Estate

Contemporary Topics

Timothy Love

Design For Real Estate

Contemporary Topics

Foreword

This course provides a comprehensive understanding of the role of design and design professionals in real estate, from project conception to project delivery to postoccupancy evaluation. The goal is to provide developers and owners with the knowledge and methodological tools arising from design to conceive and execute distinctive, financially successful, socially responsible, and environmentally sustainable projects. The course explores the programmatic and spatial interdependency of the components that make up real estate, along with a variety of methods for integrating financial analysis and design considerations.

For the final project of the course, 2-3 students collaborated on a project of the student group’s choosing. The projects fell into two overarching categories - a Development Proposal or a Research Report. These projects focused on an issue at the intersection of real estate development finance and design.

Students with different disciplinary backgrounds, including finance, planning, and design, were encouraged to work together, cumulating in unique and diverse perspectives relating to their chosen topics. The compendium of essays that resulted provides a fascinating snapshot of the preoccupations of students who are, in many cases for the first time, learning about the many ways that financing strategies, regulations, and design considerations intersect to shape individual projects and the contemporary city.

Course Instructor

Timothy Love

Teaching Associate

Justin Joel Tan

Student Contributors

Muram Bacare, Kofi Bempong, Salman Bin Ayyaf, Jason Boyle, Yuki Cao, Catherine Chun, Pauline Colas, Crystal Cui, Porsche Dames, Ava Dimond, Alexander Dragten, Adam Drummond, Nelson Duque, Costa Enriquez Teran, Lily Friedland, Xinyu Gao, Yupeng Gao, Karen Garcia Ibarra, Noah Garcia, Brandon German, Matias Griffiths, Peihao Jin, Yanjia Jin, Noah Johnson, Kwangmin Ki, Luna Kim, Phil Kim, Adrian Kombe, Jae Young Lee, Shawn Lee, Mook Lim, Zamen Lin, Zack Lively, Josh Mccarthy, Lydia Melnikov, Ilias Metaxas, Maria Jose Moreno, Daniela Morin Vazquez Mellado, Francis Motycka, Benjamin Orf, Yuli Ouyang, Jeewoo Park, Jackson Peacock, Benjamin Perla, Cole Peterson, Advait Reddy, Lucas Ryder, Tejas S, Eesha Sanghrajka, Paul Schulman, Megha Sharma, Phil Smith, Pranav Subramanian, Stacey Tsai, Joe Tu, Marko Velazquez, Peggy Wu, Alex Yang, Jerry Zhang, Leo Tianju Zhang, Wenbo Zhang, Caroline Zou

If readers are interested in a particular project, they can reach out to the instructor for more information.

Preface

Foreword

Development Case Studies

I. Adaptive Reuse / Conversions

The Feasibility Gap: Chinatown’s Office-to-Resi Dilemma

Alexander Dragten, Jackson Peacock, Joe Tu

95 Berkeley: Office to Residential Conversion: Exploring the development’s opportunities, incentives & limitations

Philip Smith, Costantino Enriquez, Jerry Yonghao Zhang

133–169 N Washington Street: Redevelopment Proposal

Jaeyoung Lee, Brandon German, Yupeng Gao

Kingston St.: Office to Residential Conversion

Yuki Cao, Lucas Ryder, Caroline Zou

The Overbuilt Life Science Sector in Boston: Redevelopment Report

Crystal Cui, Peihao Jin, Zamen Lin

II. Ground Up Development

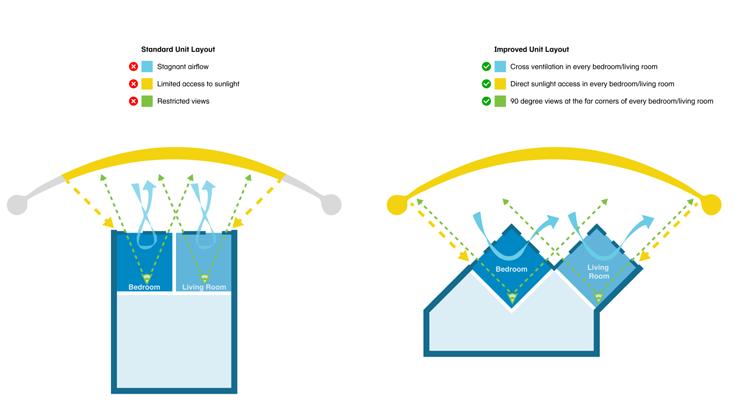

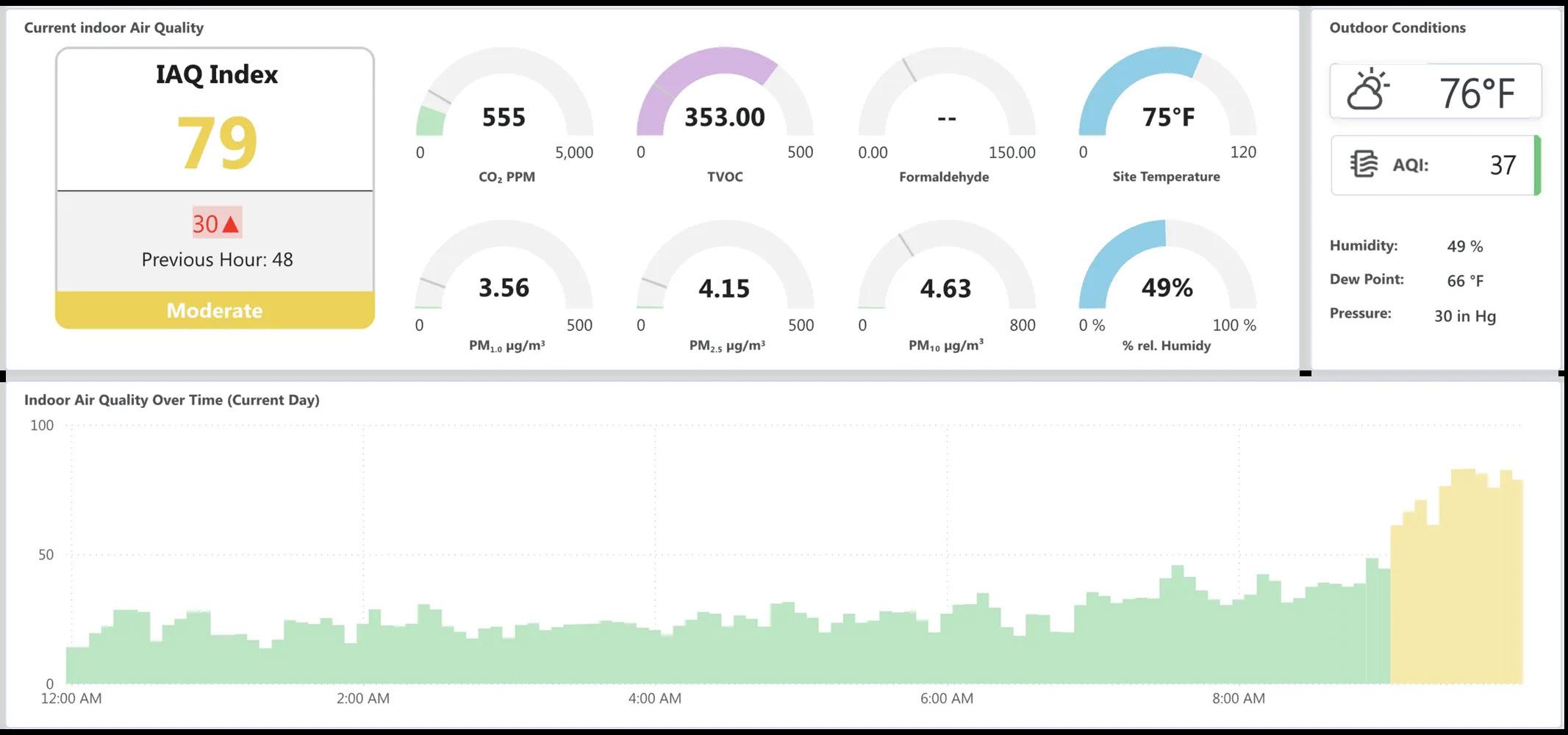

A New Class of Housing: The World’s Healthiest Home

Ava Dimond, Francis Motycka, Pranav Subramnian

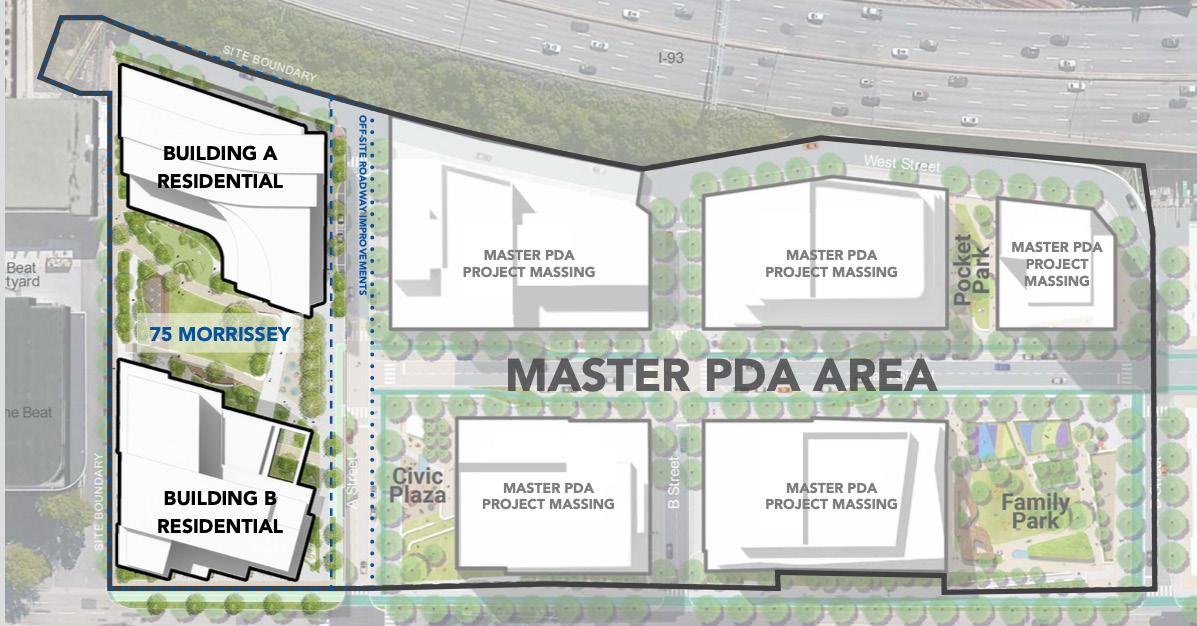

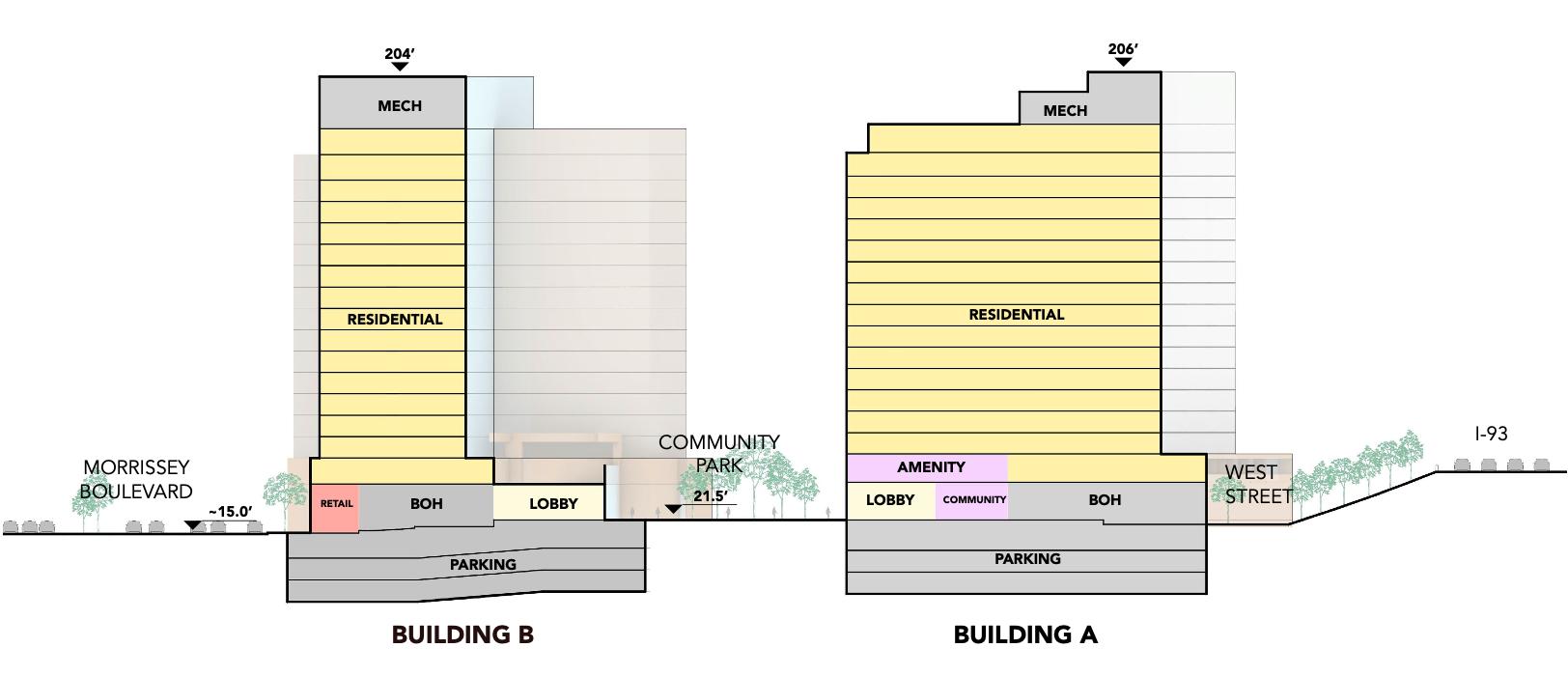

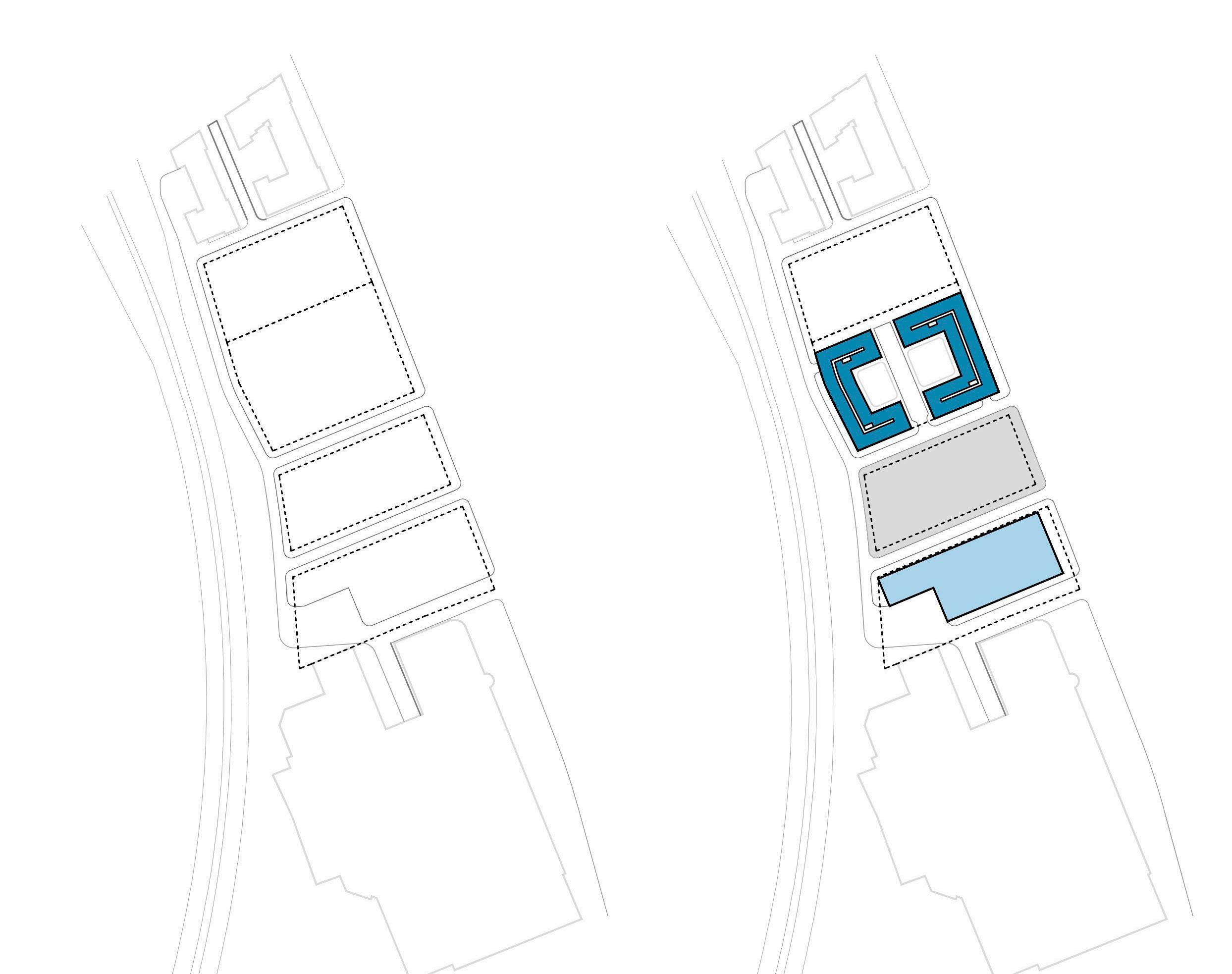

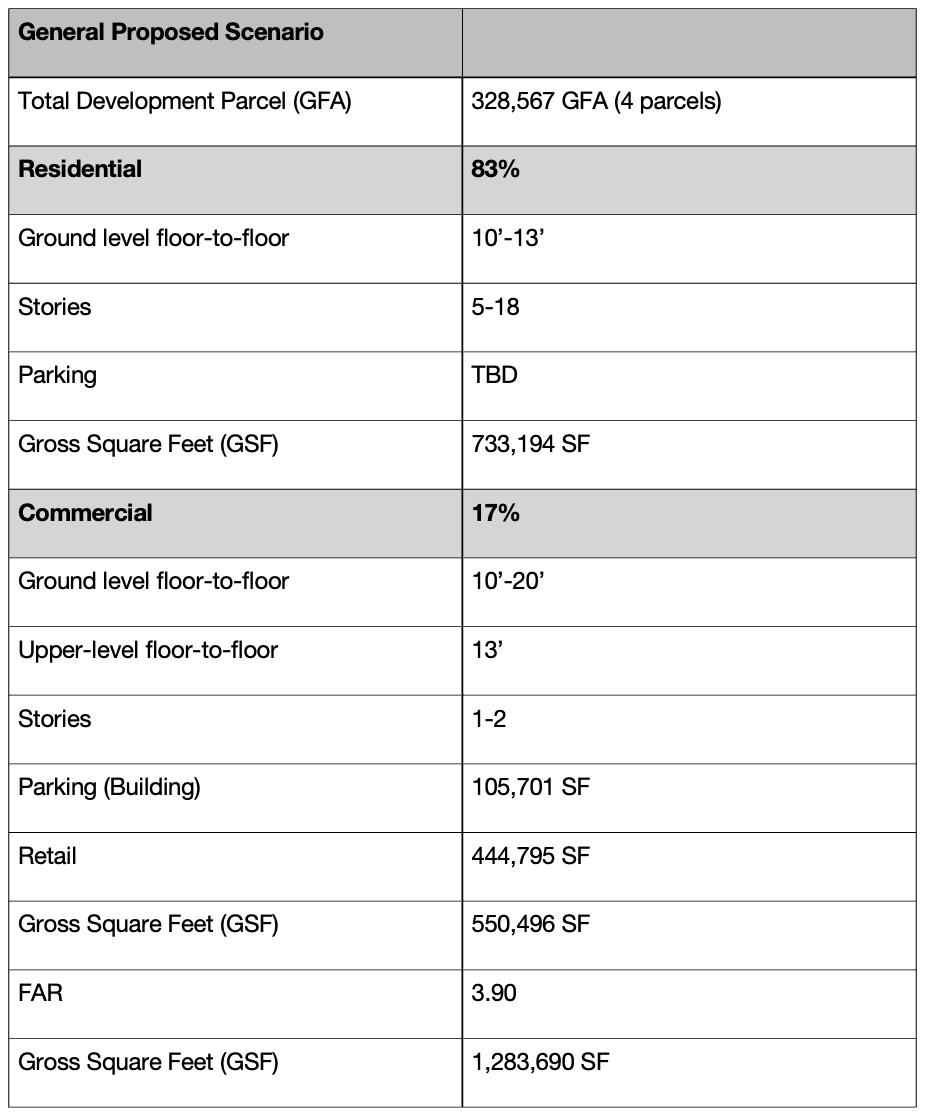

35-75 Morrisey Boulevard: Ugly Duck Studios Redevelopment

Matías Griffiths, Josh McCarthy, Cole

Peterson

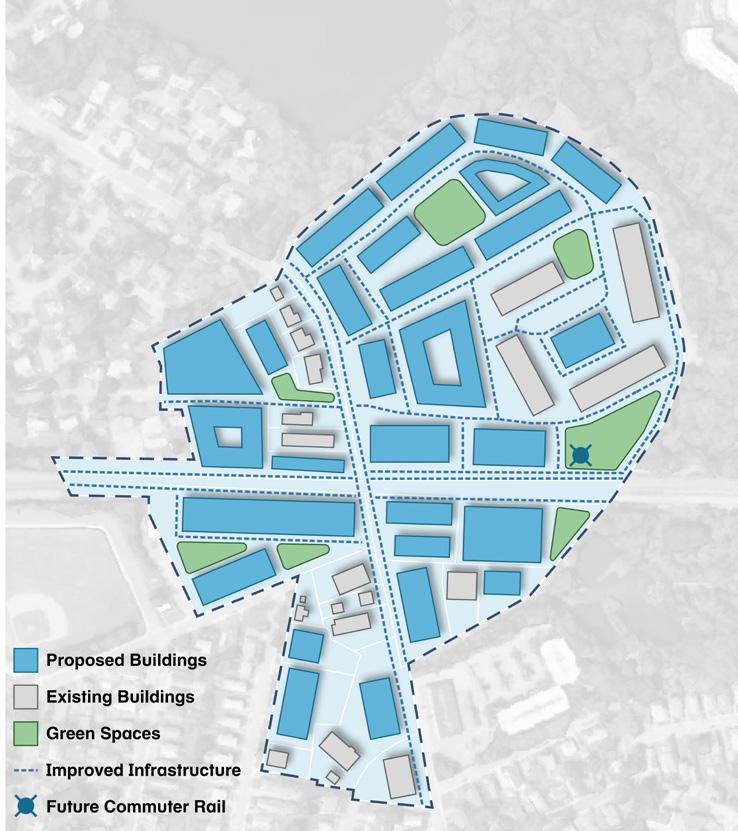

The Bgend: From Transit Hub to Community Hub

Marko Velazquez, Kwangmin Ki, Jeewoo Park

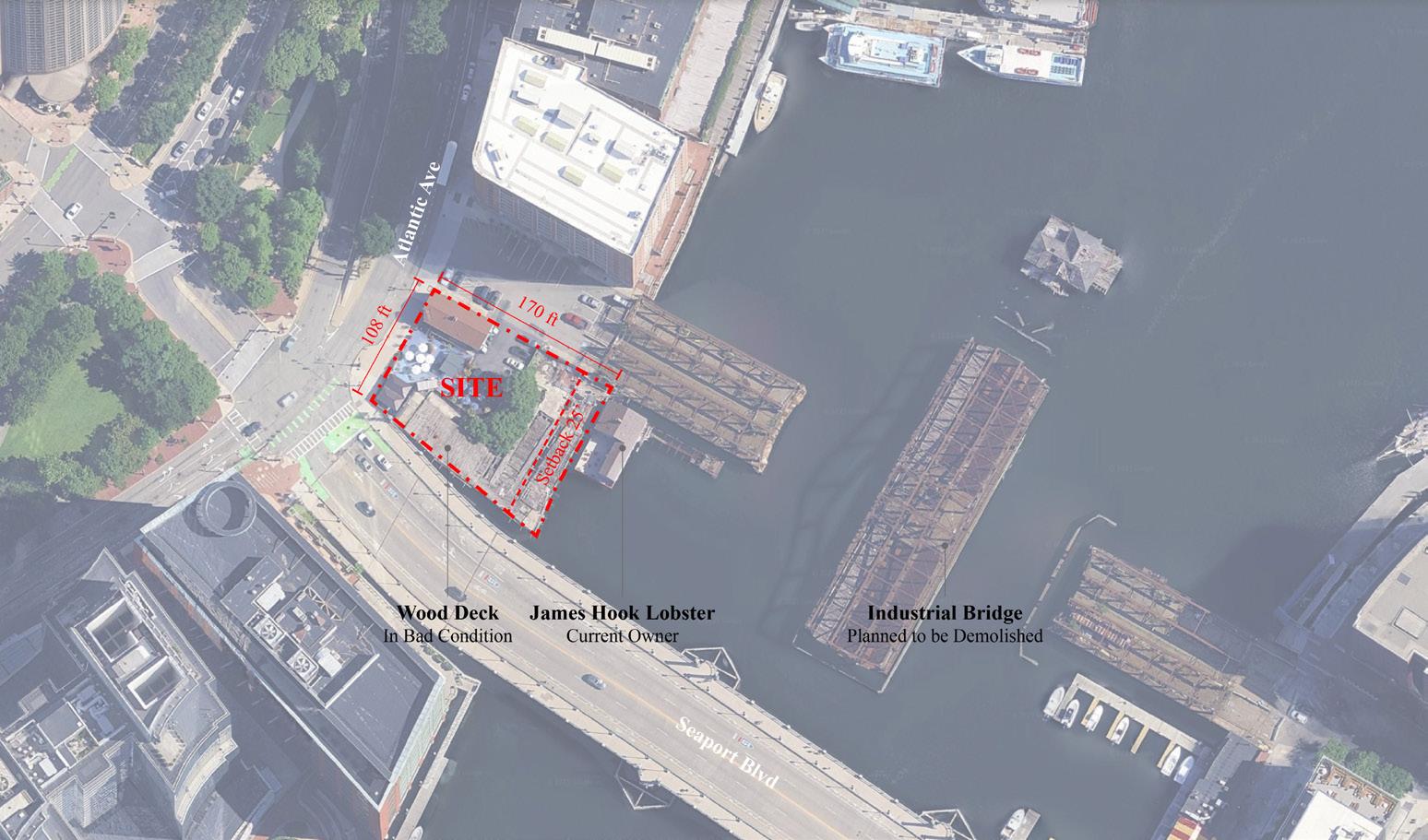

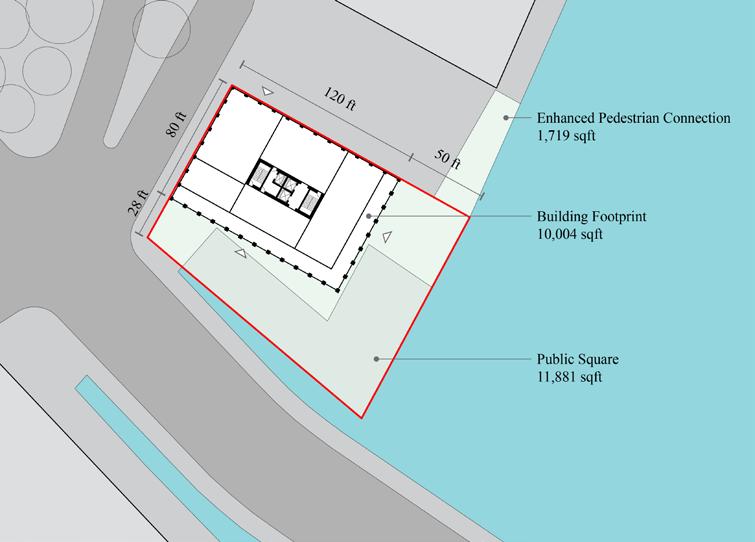

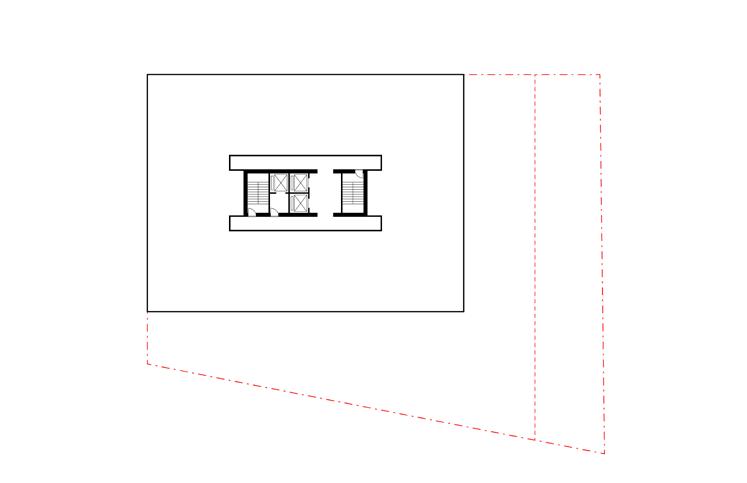

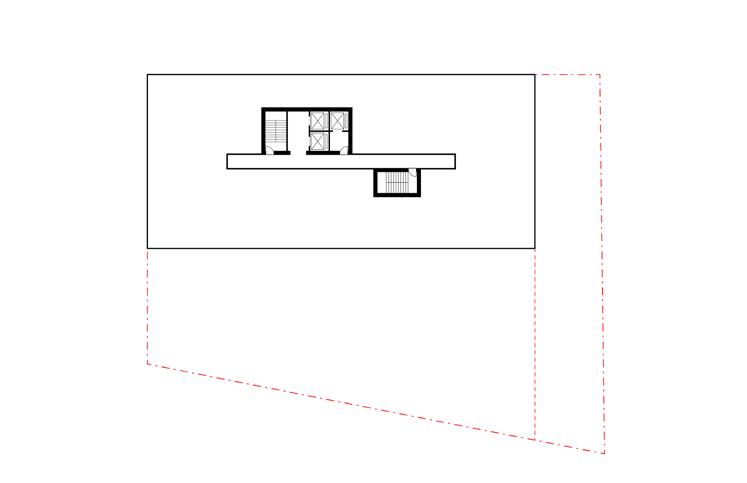

Hark, hark! The Wharf at 440 Atlantic: A Development Proposal for the James H Hook Lobster Site at 440 Atlantic Ave, Boston

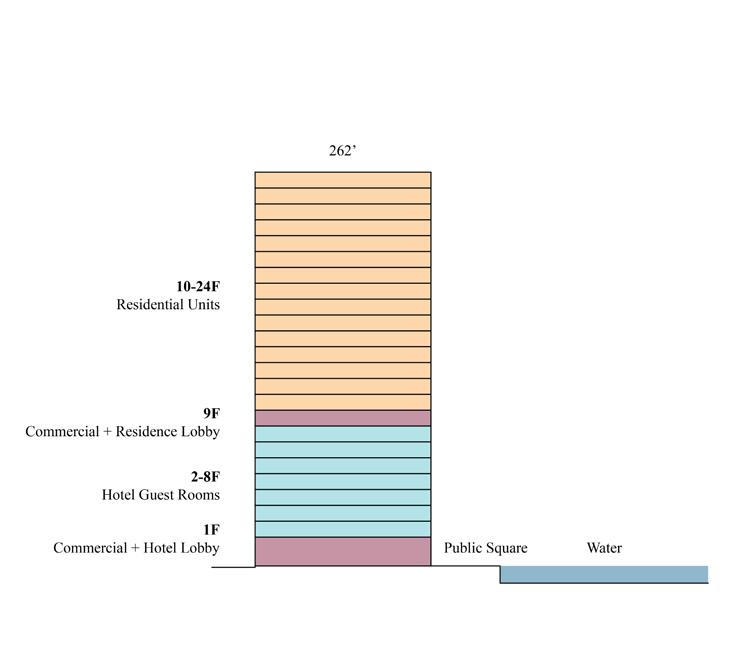

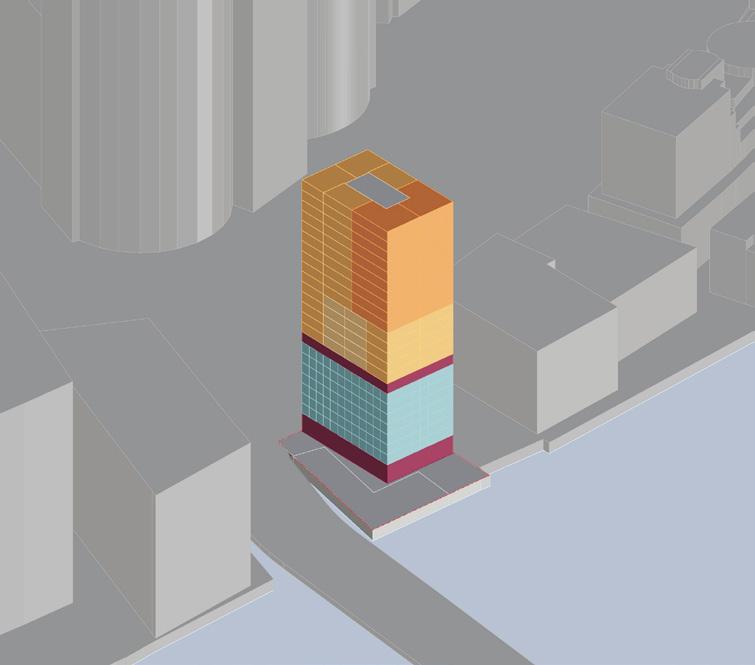

Yuli Ouyang, Tejas Sampath, Wenbo Zhang

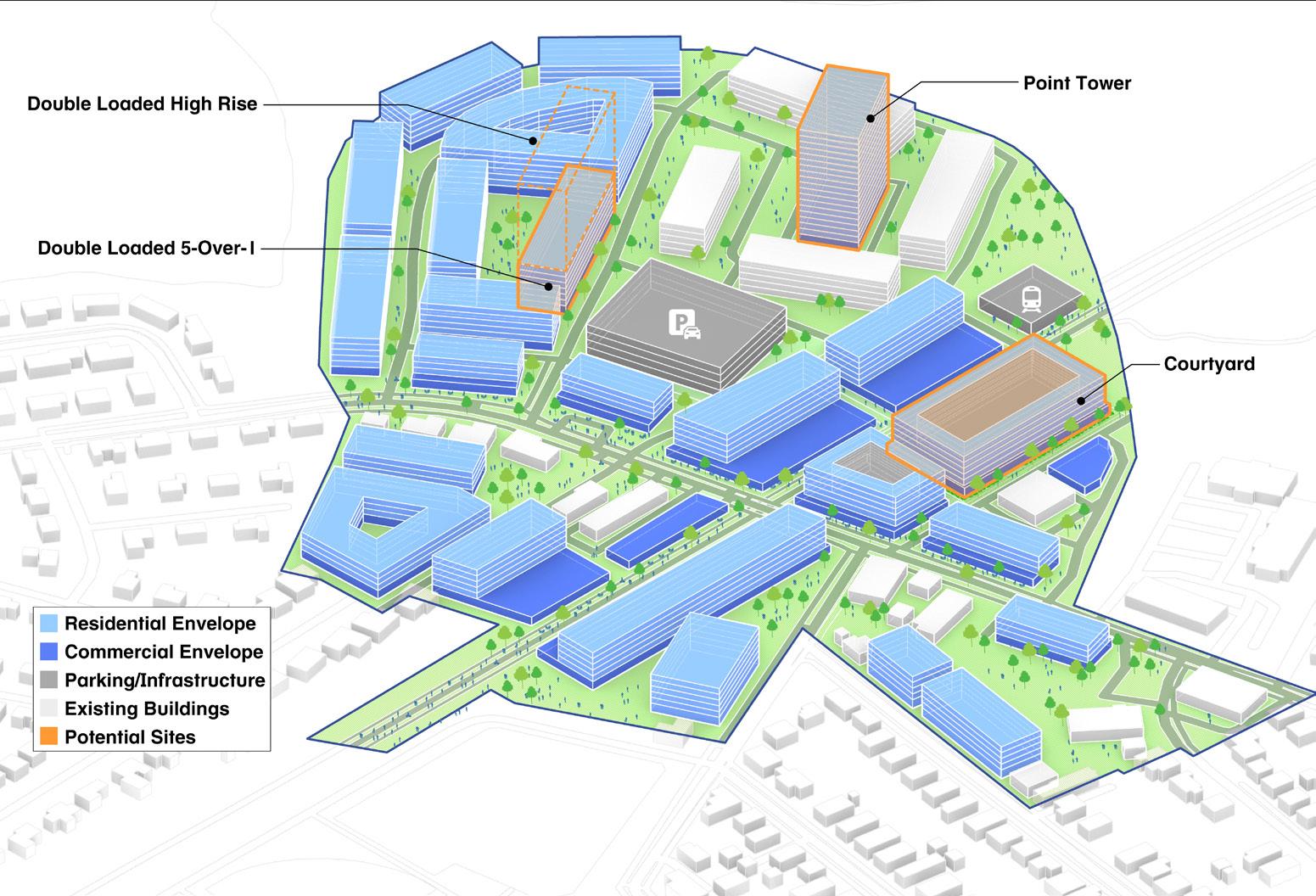

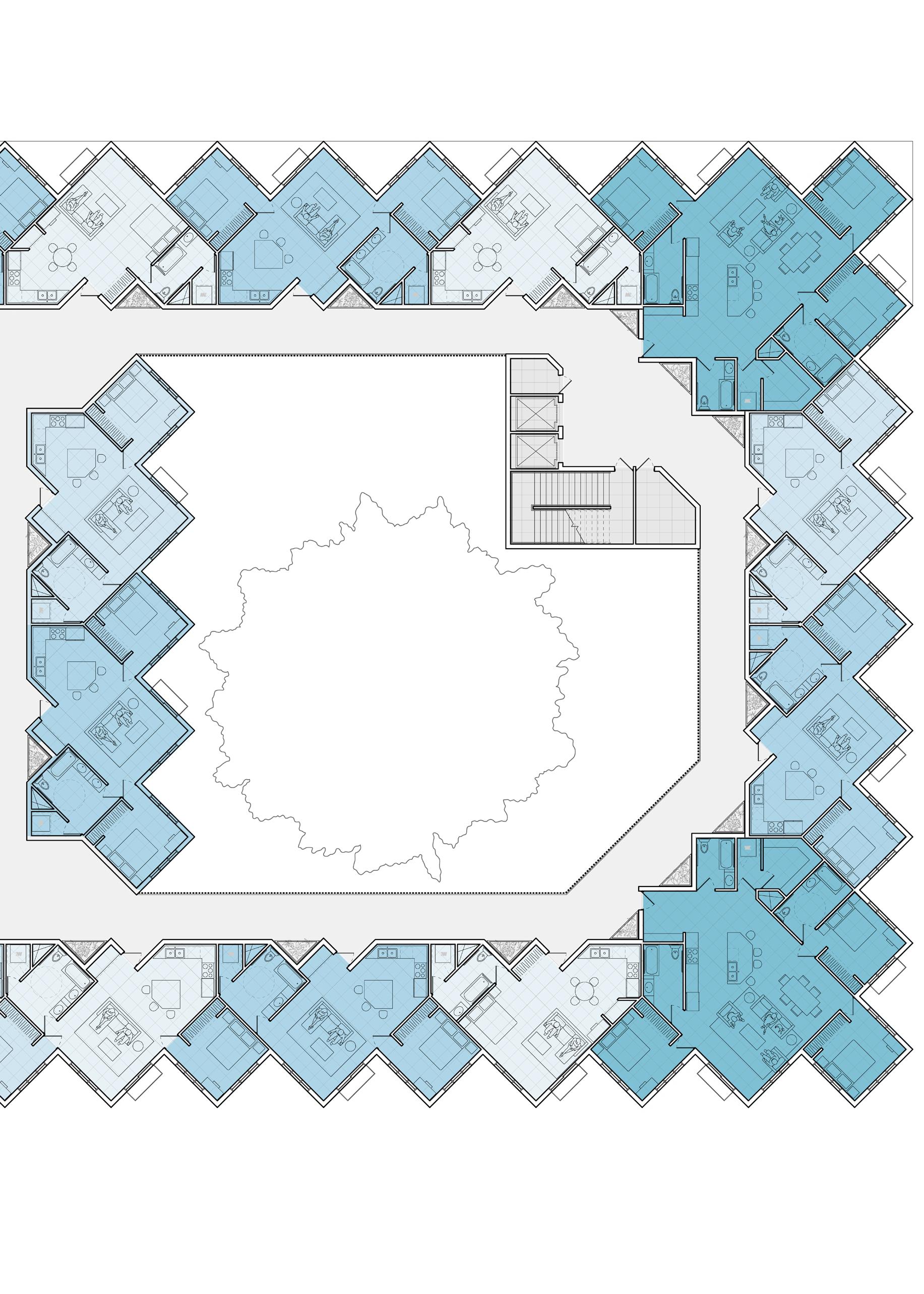

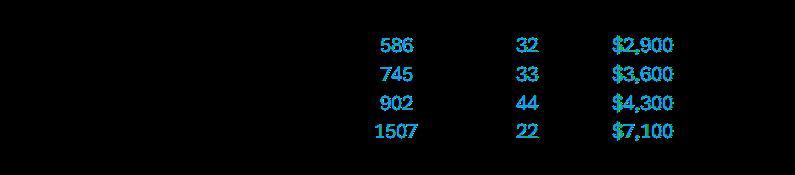

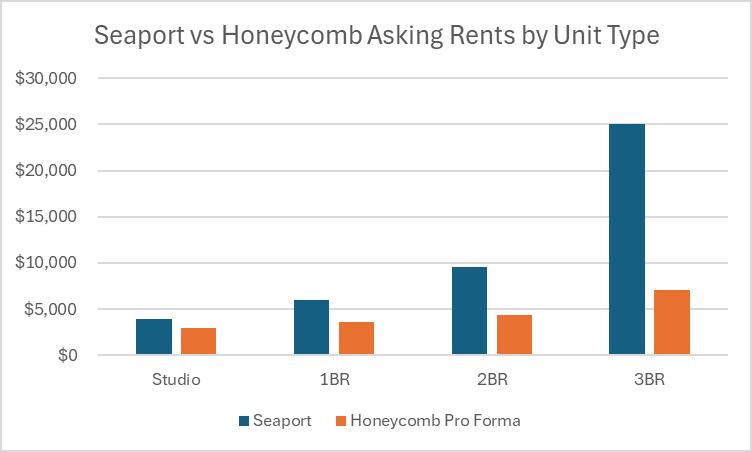

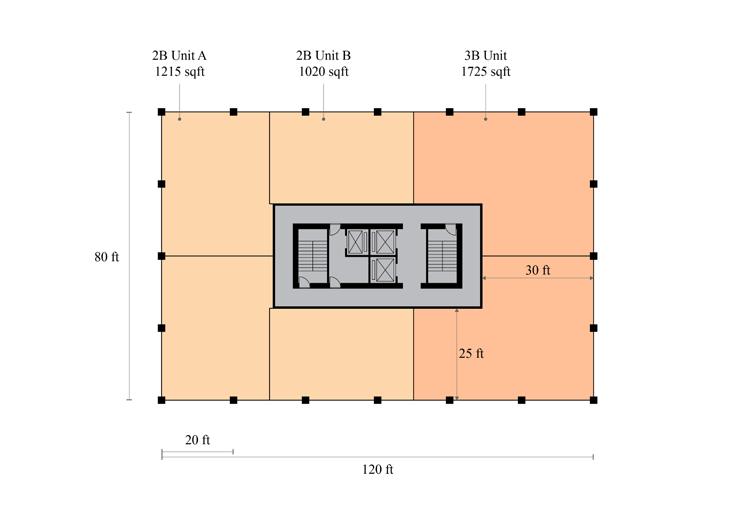

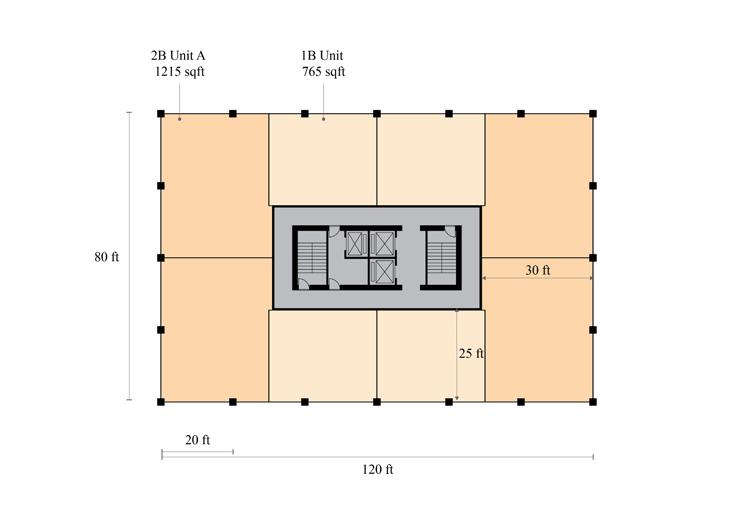

A Future Proof Typology: Development Test Fit at 56 Fulton Street

Kofi Bempong, Porsche Dames, Alex Yang

Research Projects

The Strategic Art of Anchoring: High-End Art Institutions as Urban Catalysts

Adrian Kombe, Benjamin Perla, Catherine Chun

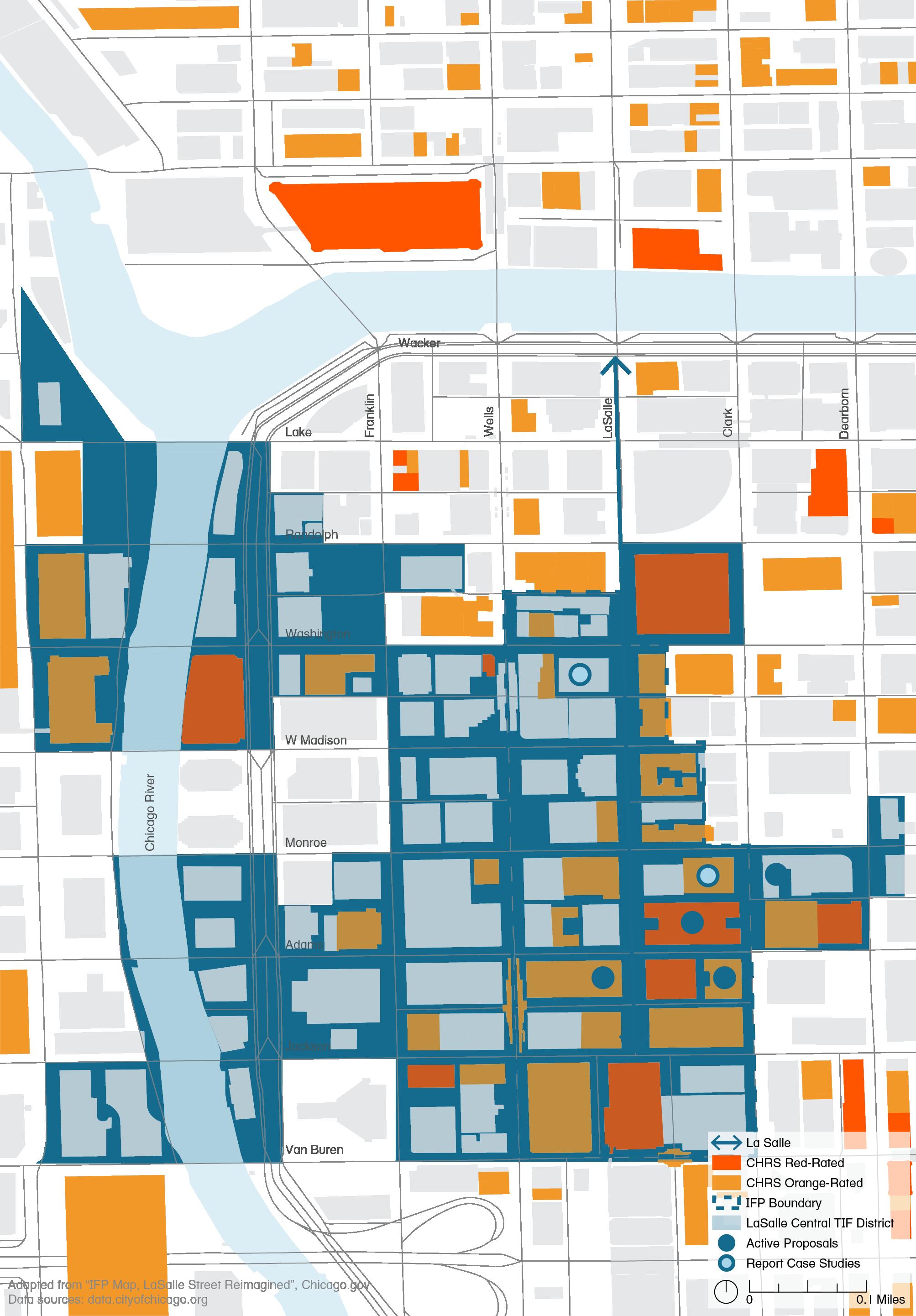

A New Vision for LaSalle: Comparing Adaptive Reuse Across Different Office Building Typologies

Pauline Colas, Lydia Melnikov, Advait Reddy

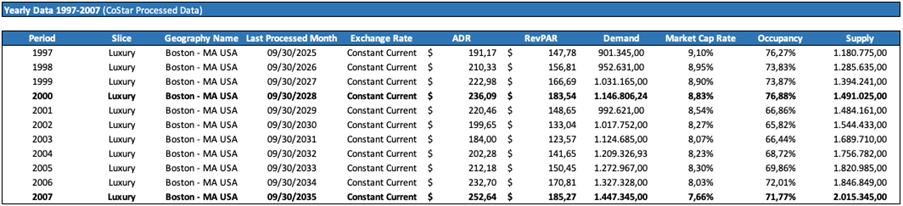

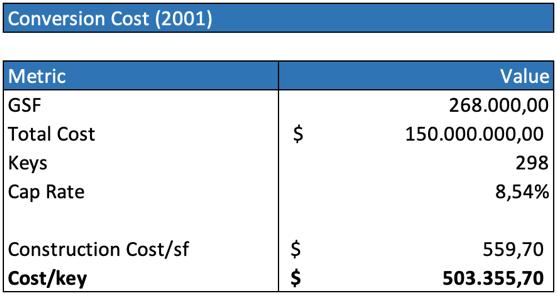

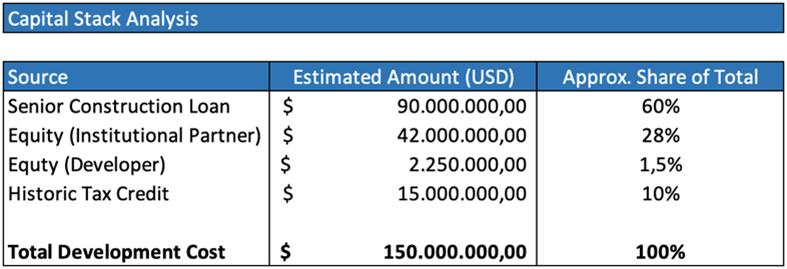

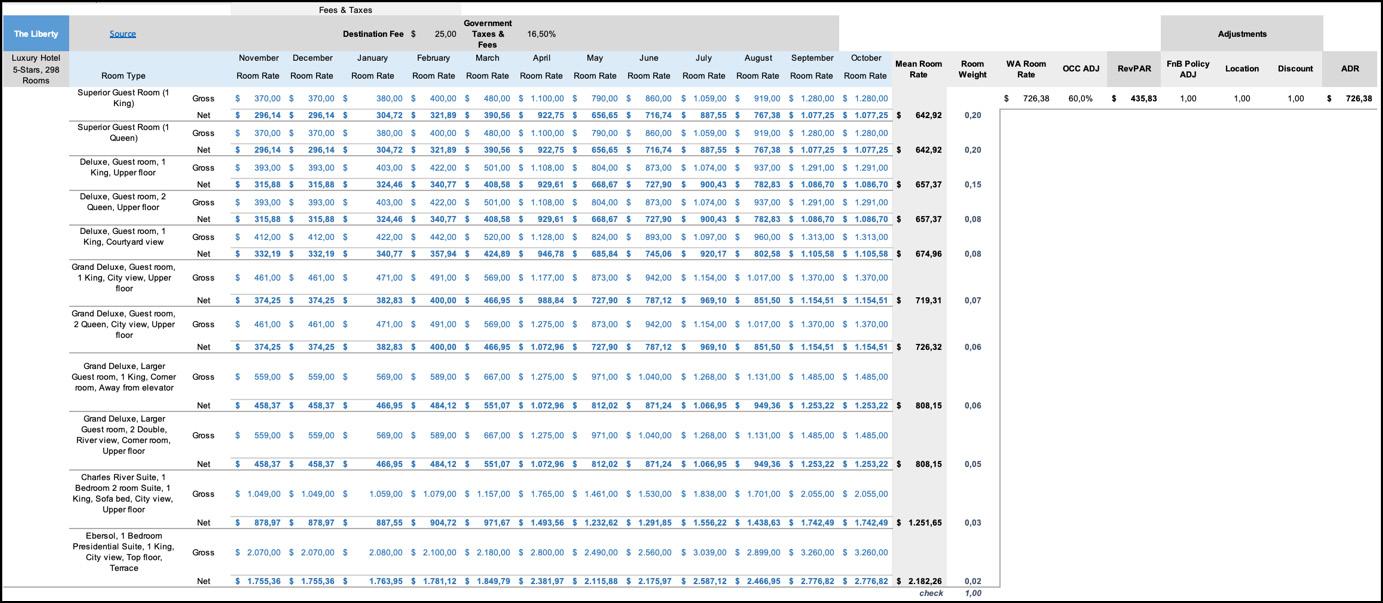

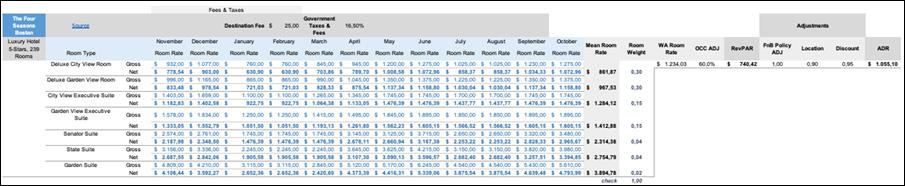

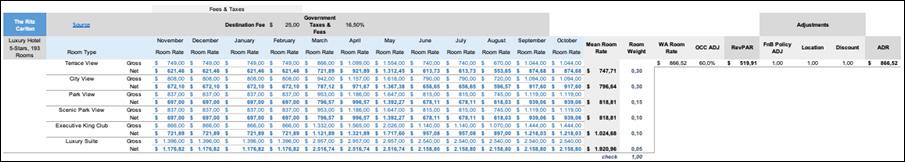

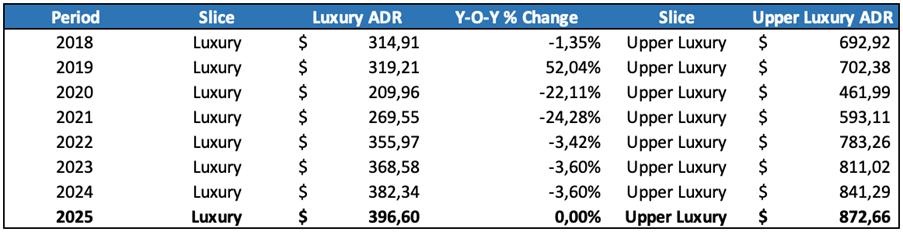

Conversion of Real Estate Assets to Hospitality: The Liberty Hotel Case Study

Salman Bin Ayyaf, Mook Lim, Ilias Metaxas

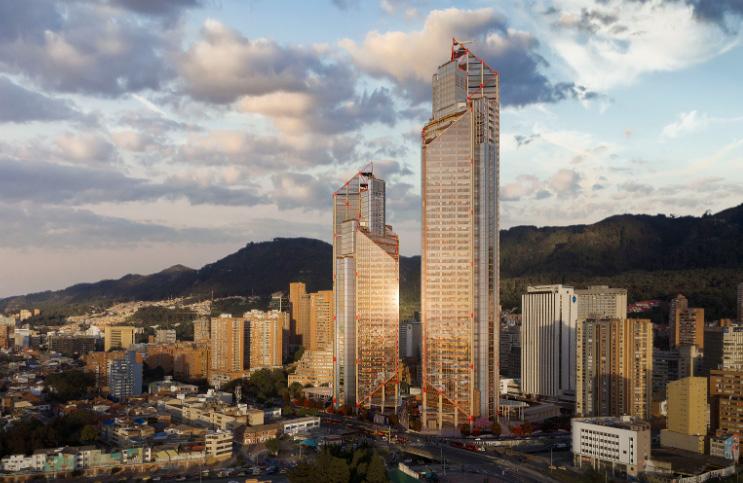

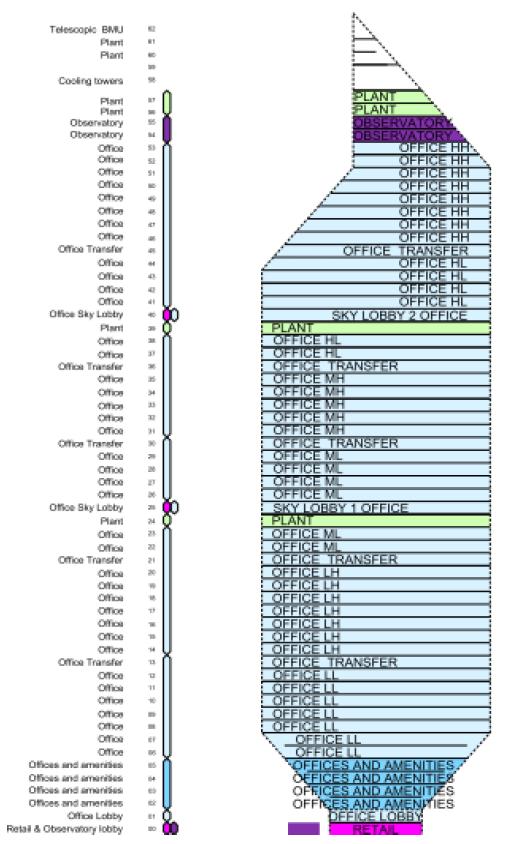

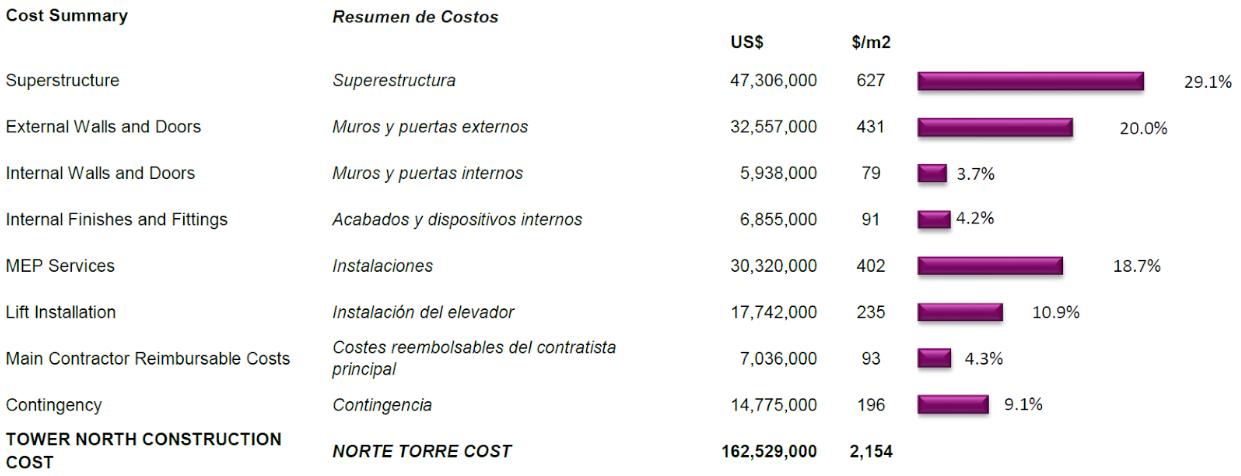

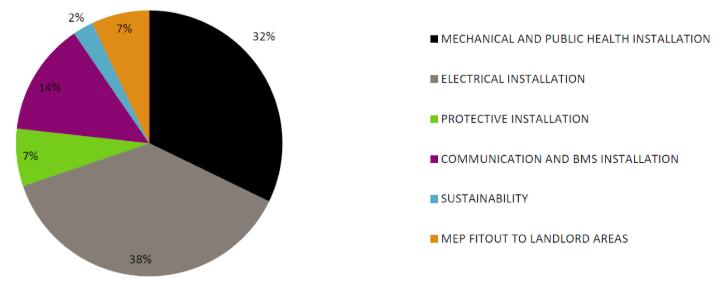

Super-Tall Skyscrapers: New York, Middle East and Asia vs. LATAM

Karen Garcia, Luna Kim, Maria Jose Moreno

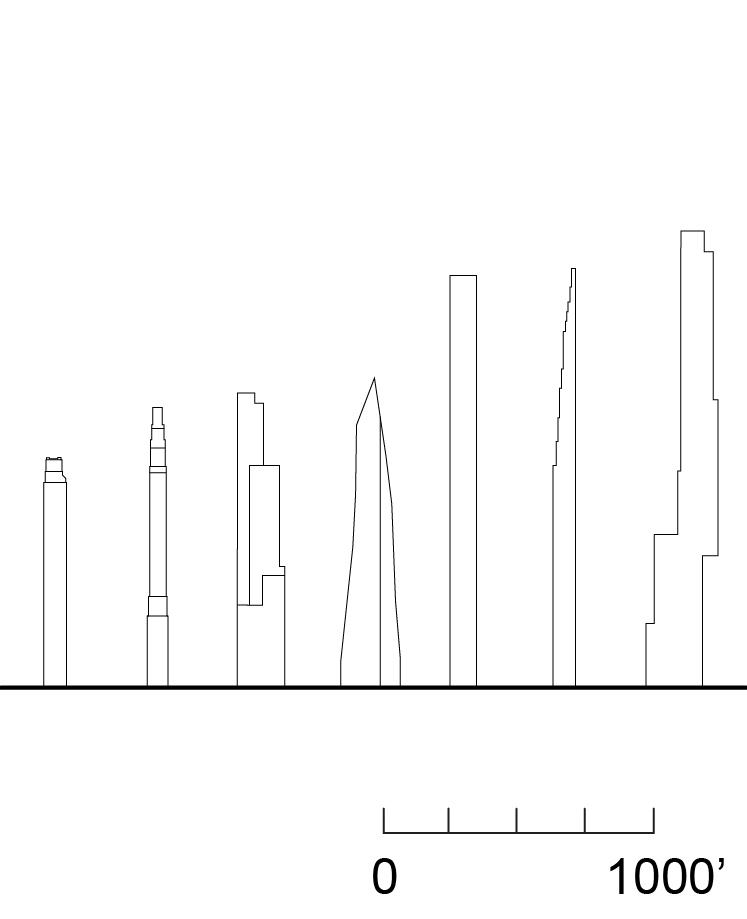

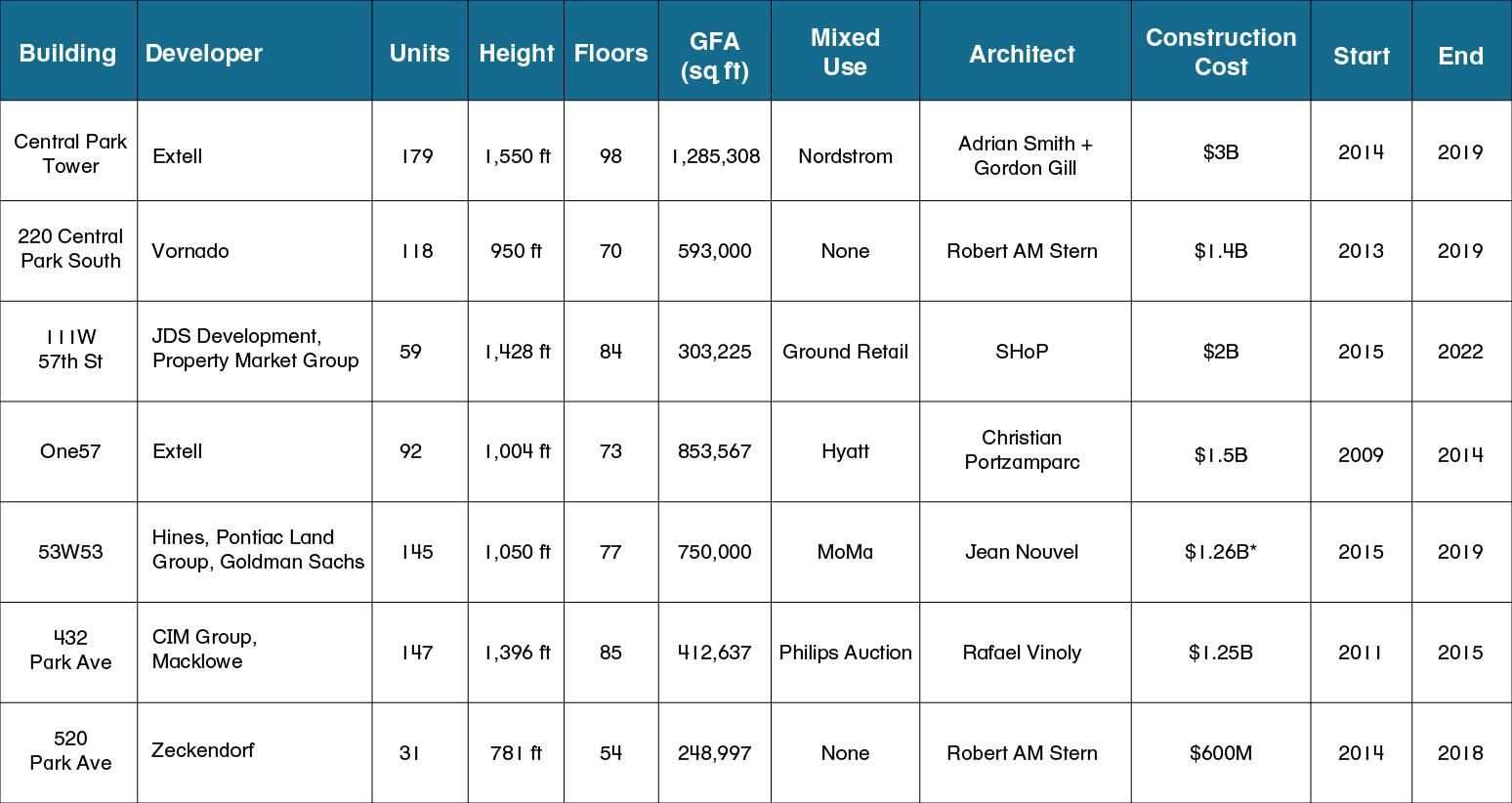

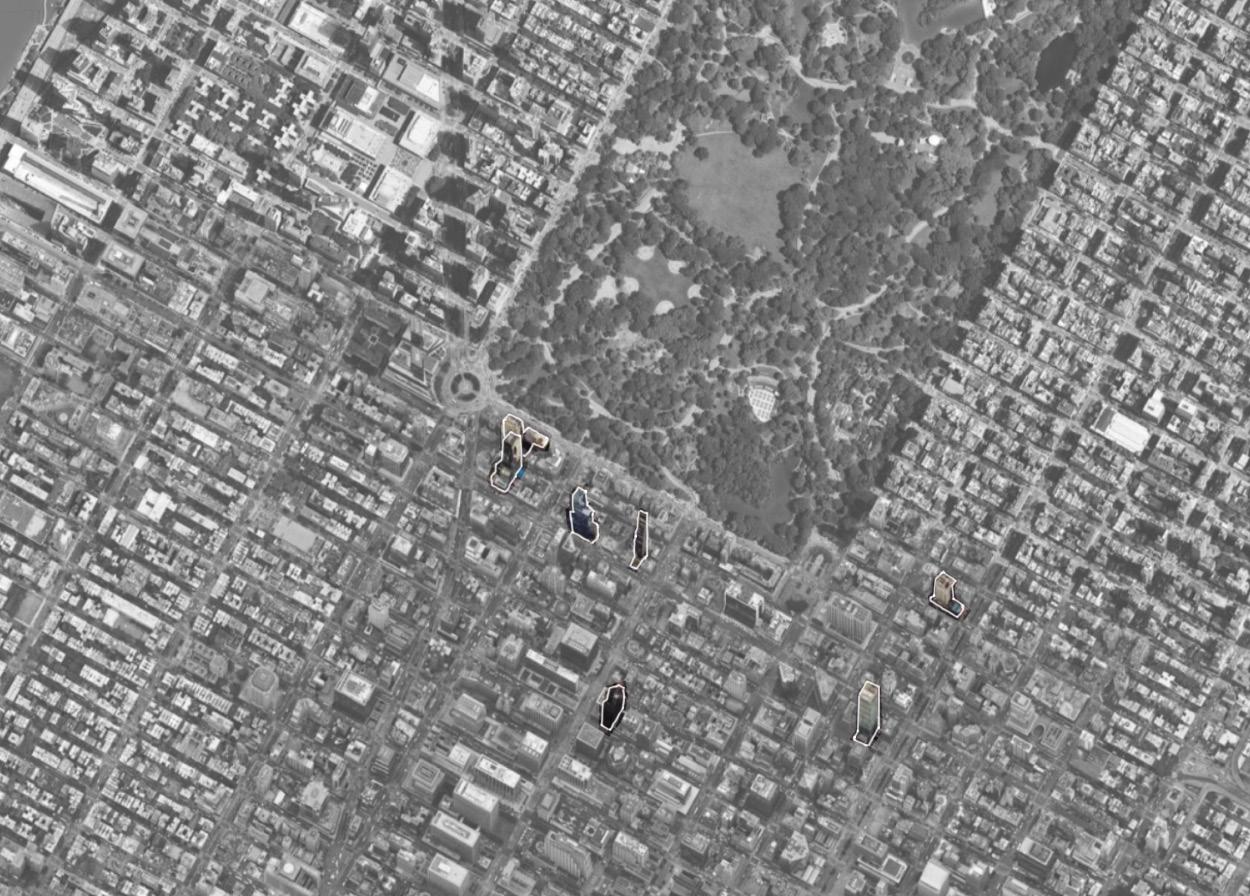

Billionaire’s Row Architecture and Valuation Analysis of NYC Super Tall Typology

Daniela Morin, Megha Sharma, Paul Schulman

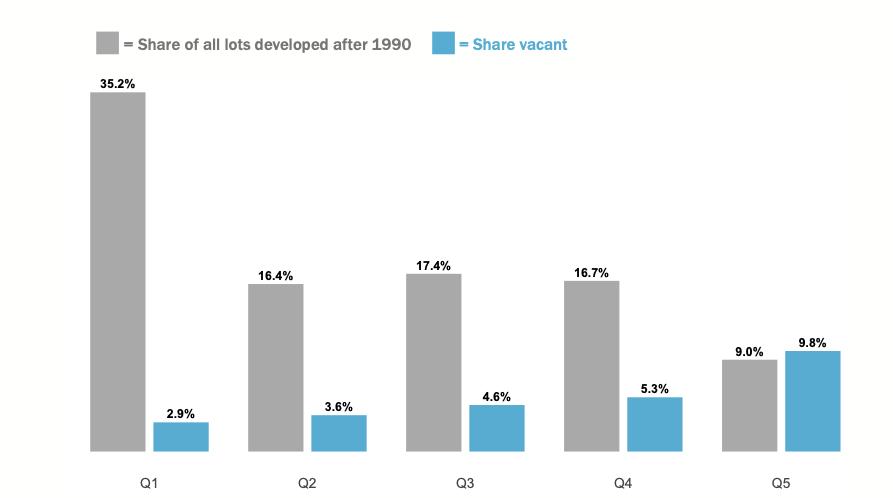

Odd Lots: Lessons for Infill Housing Development

Jason Boyle, Noah Johnson, Zack Lively

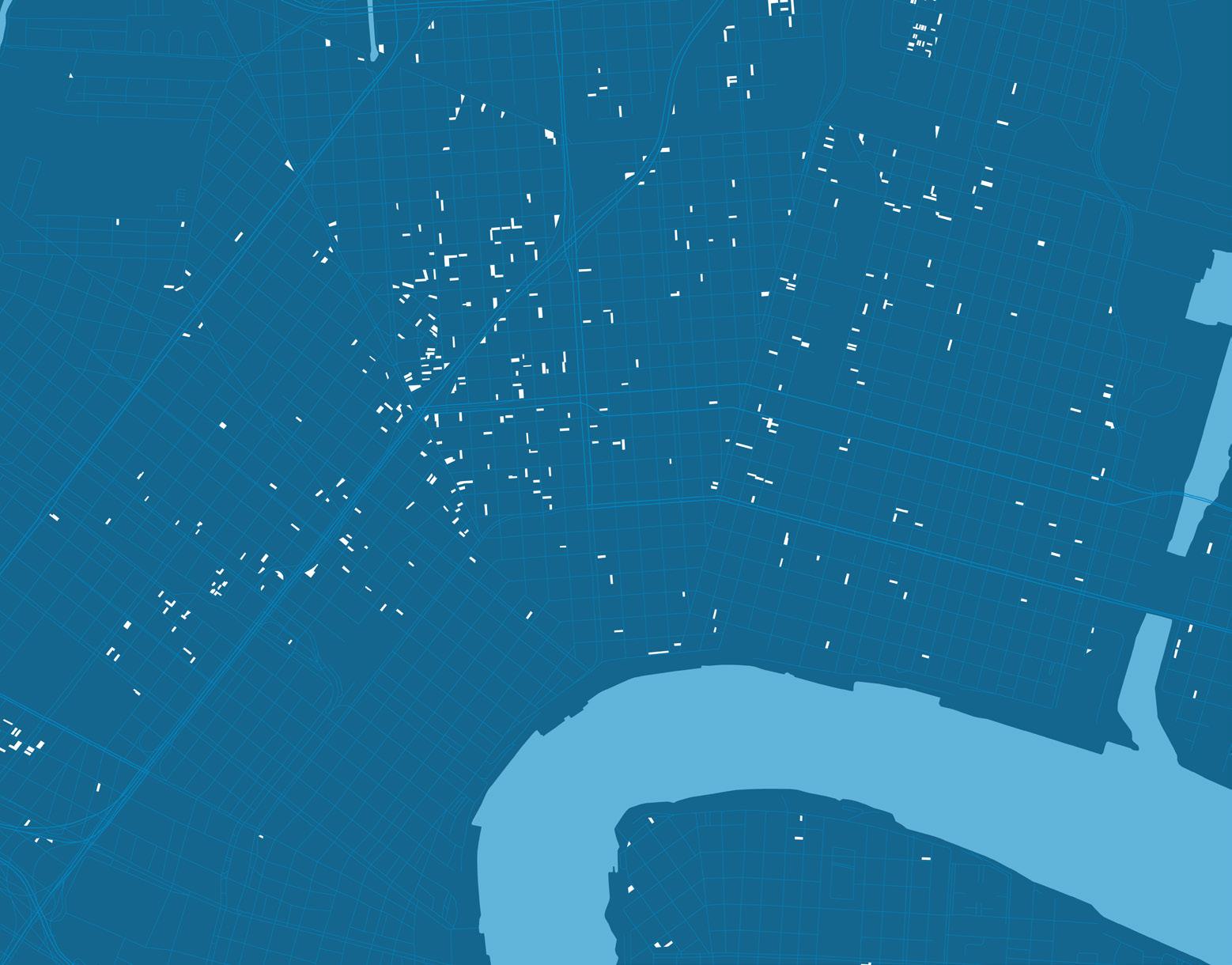

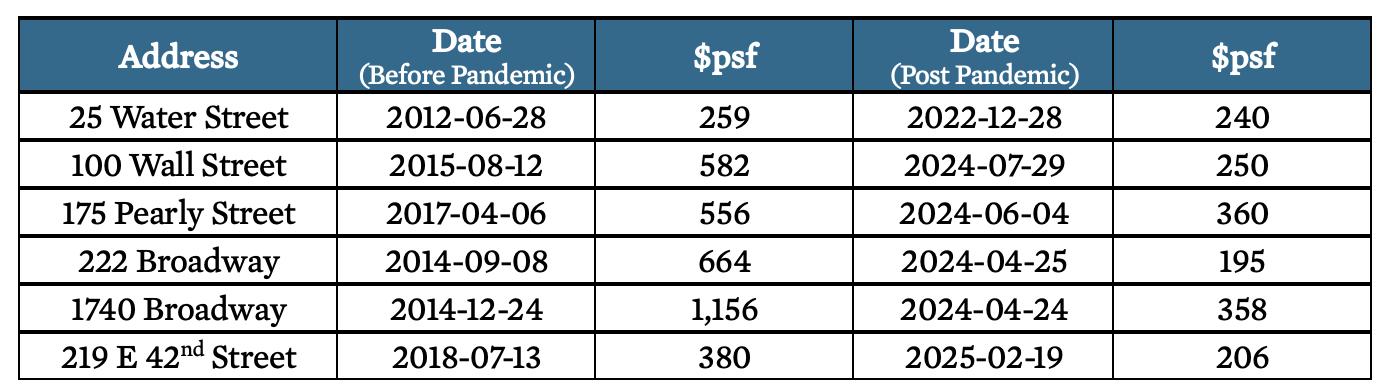

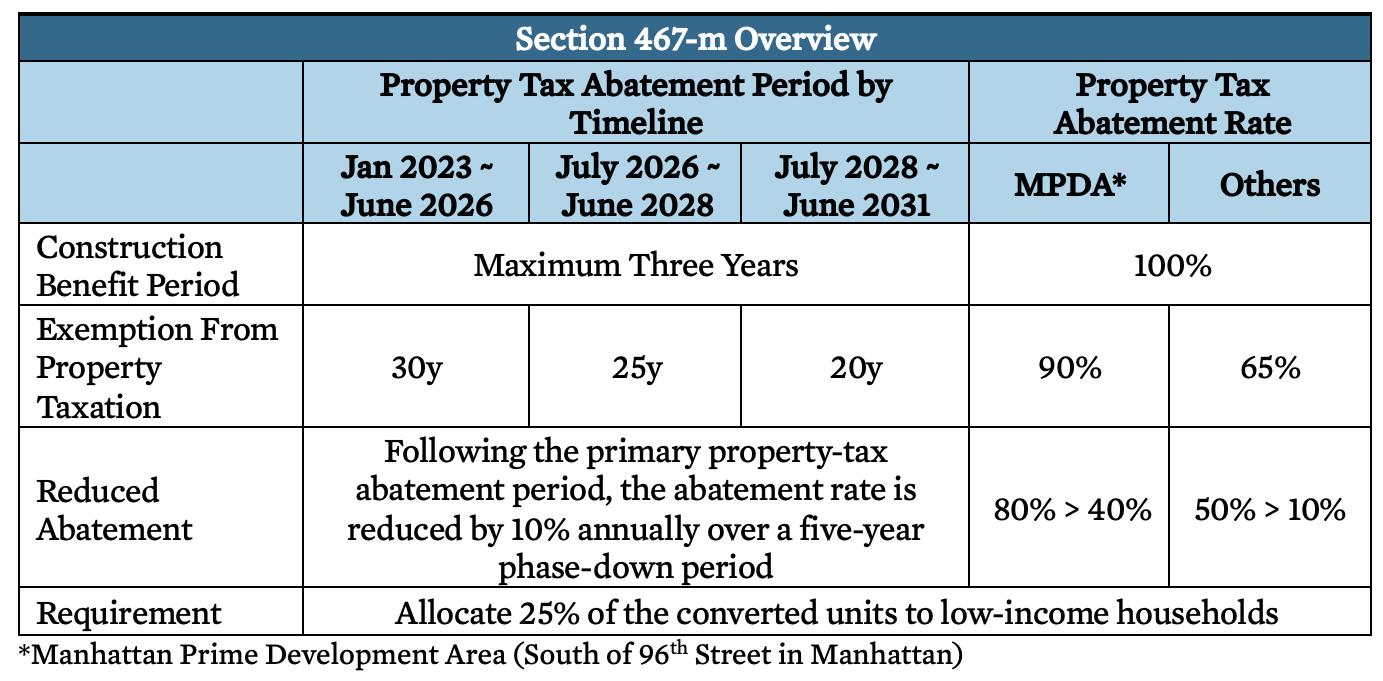

The Great Repositioning: How Policy and Economics are Reshaping New York City through Office-to Residential Converisons

Phil Kim, Shawn Lee, Benjamin Orf

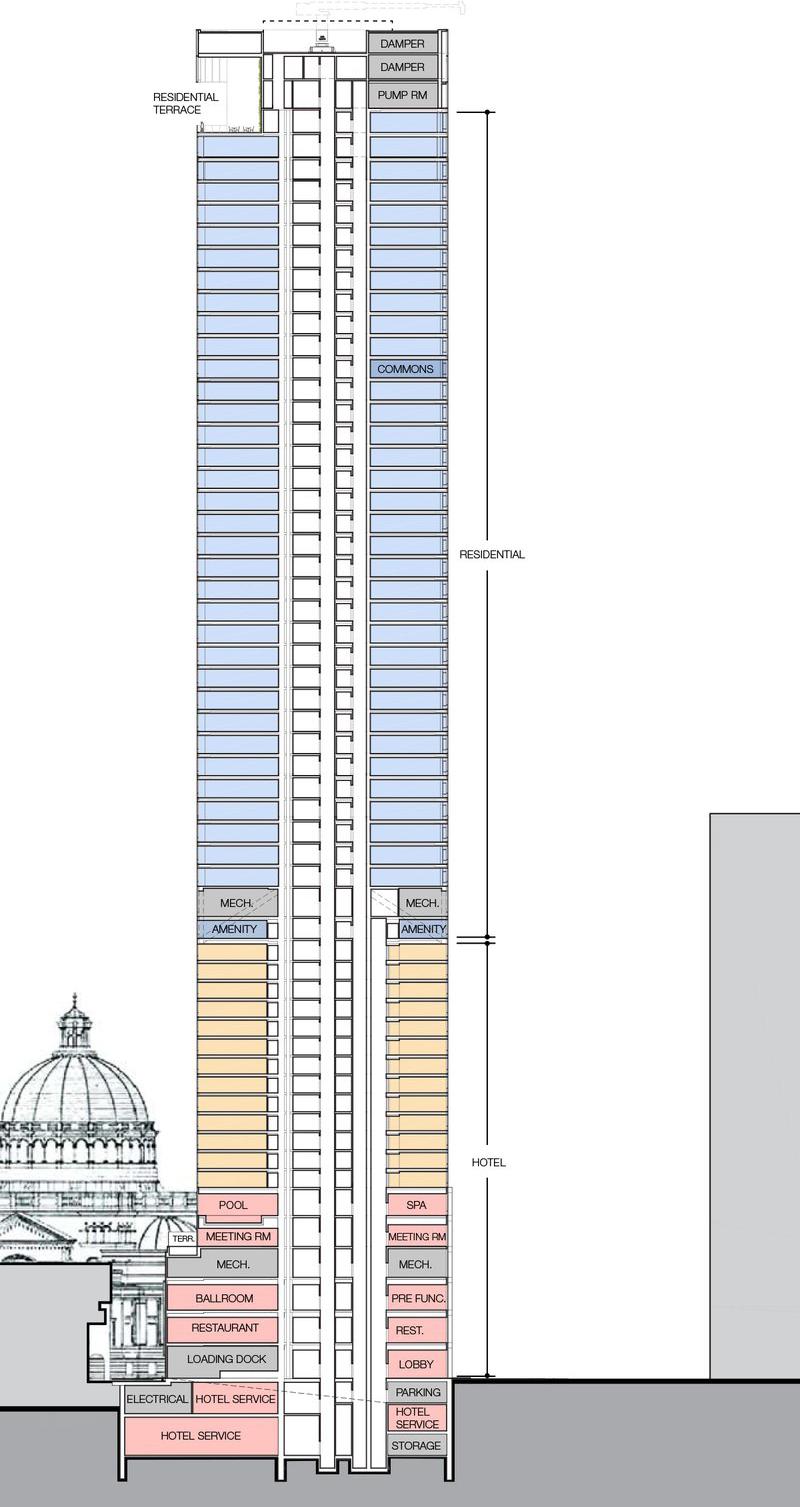

High-rise Mixed-use Hotels: Four Seasons Hotels in the U.S., China and Middle East

Peggy Wu, Muram Bacare, Yanjia Jin

What Is Green Worth?

Performance, Policy, and the Price of Sustainability in Three Office Markets

Noah Garcia, Stacey Tsai, Nelson Duque

Wellness Design: What We Can Measure, What We Can’t, & Why It Matters

Lily Friedland, Adam Drummond, Eesha Sanghrajka

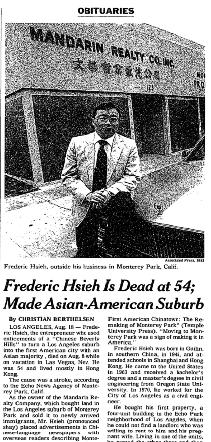

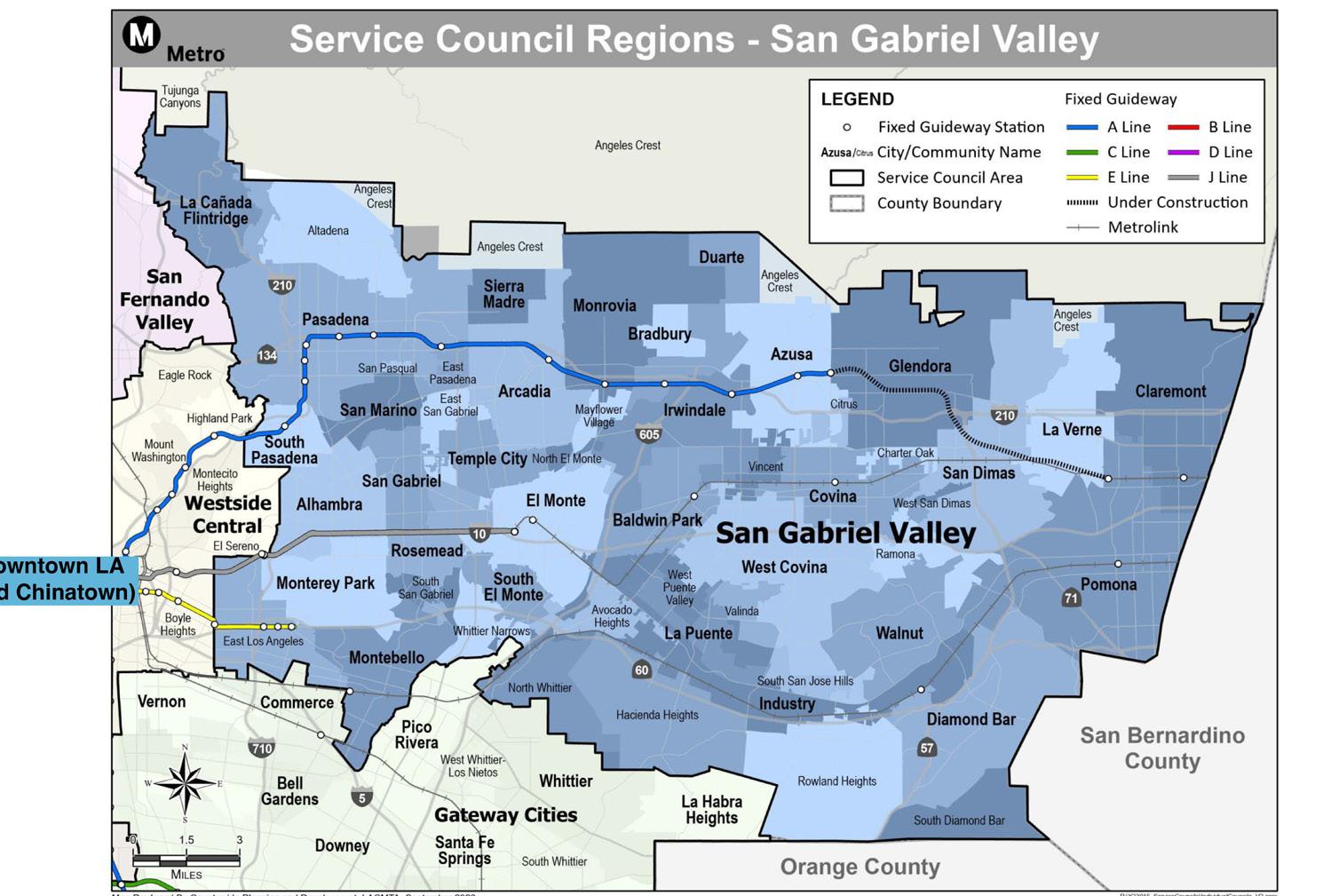

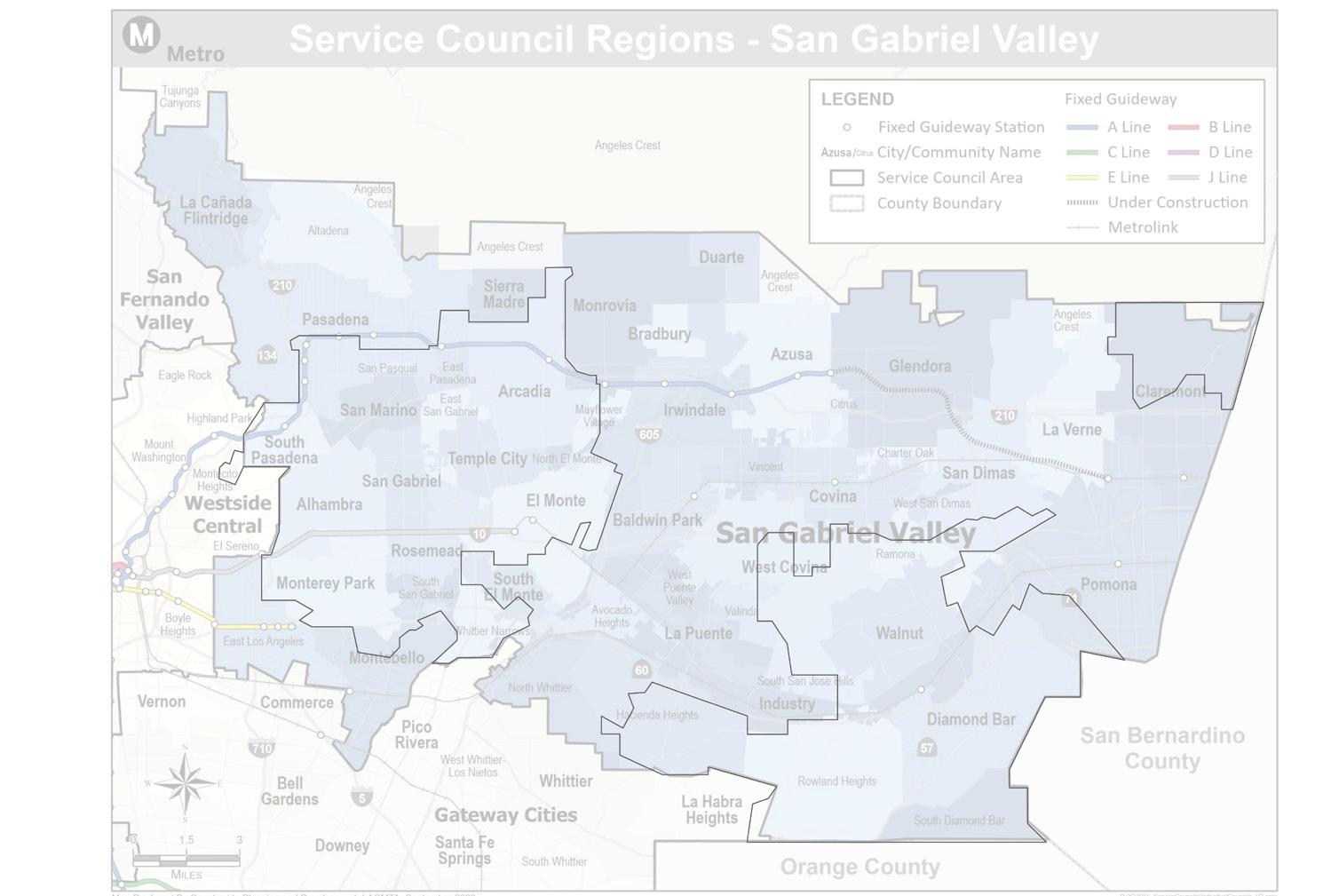

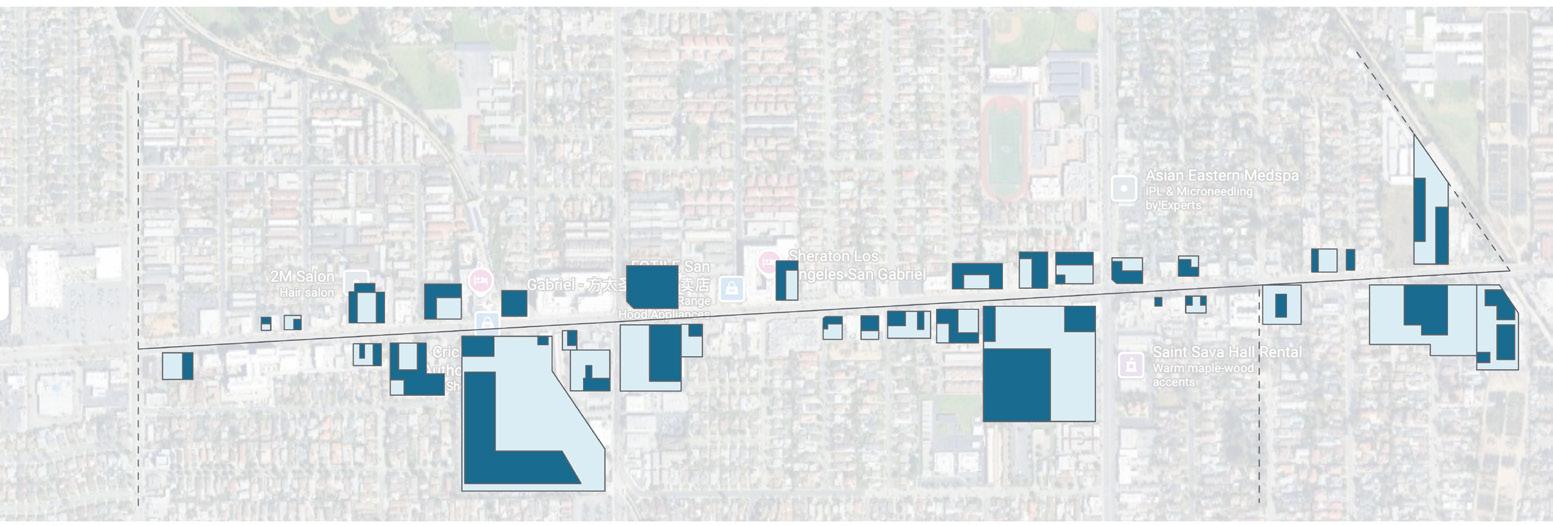

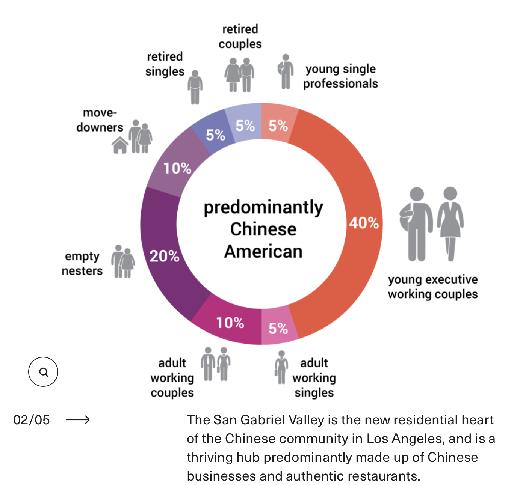

San Gabriel Valley, the First Ethnoburb, the Ability to Invest Leo Tianju Zhang

Adaptive Reuse / Conversions Development Case Studies

The Feasibility Gap

Chinatown’s Office-to-Resi Dilemma

The Feasibility Gap: Chinatown’s Office-to-Resi Dilemma

Introduction

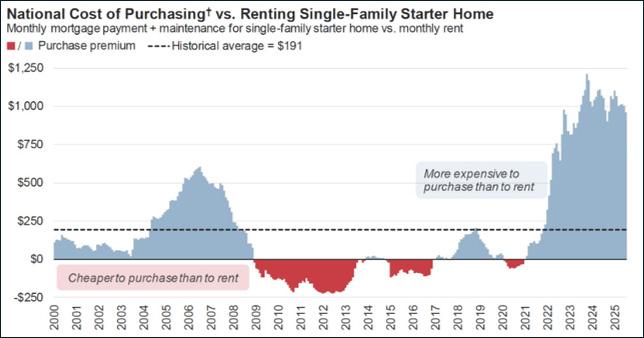

Cities across the United States are stuck with a basic mismatch: there is far more office space than today’s economy needs, and nowhere near enough housing for the people who want to live in these urban cores. Office demand has weakened as hybrid and remote work have taken hold, leaving large chunks of the existing office stock underutilized or obsolete. At the same time renters face a severe shortage of reasonably priced apartments. This imbalance is especially visible in dense neighborhoods like downtown Boston and Chinatown, where aging office buildings sit half empty while renters compete fiercely for limited units. At the same time, the financial gap between owning and renting has rarely been wider, which tilts households toward renting and increases the urgency of new multifamily supply. Nationally, the typical monthly payment needed to purchase a starter single-family home now exceeds the cost of renting by roughly $962. As long as high prices and limited for-sale inventory keep homeownership out of reach for many households, more people will remain renters for longer, and the pressure on the rental housing market will intensify.

Source: John Burns Research and Consulting, LLC

Solution

The core of the solution is fairly straightforward: take underused office buildings and turn them into housing, with help from smart public

policy. At 73 Essex Street, that means reusing the existing structure, converting it to apartments, and leaning on Boston’s office-to -residential incentives to make the project closer to being financially viable.

Adaptive reuse does a few important things at once. Keeping the building’s shell in place avoids demolition, cuts construction time, and meaningfully reduces hard costs compared with starting from scratch. It also significantly cuts embodied carbon compared to demolition + new construction, which is a policy goal of the city of Boston.

Policy support is the other piece that draws this project closer to being financially viable. Boston’s Office to Residential Conversion Program offers a 75% tax abatement for 29 years. It also offers expedited project approvals that allow building permits to be issued within 12 months and a step down in tax rate from office to residential. Together, these tools improve cash flow and reduce entitlement risk enough to attract private capital into a nichey, execution-heavy asset class. Directing this framework toward multifamily housing also ties the project back to the city’s broader housing and affordability goals. The program at 73 Essex adds 79 new units, including 14 affordable units, in the country’s 10th most unaffordable city1.

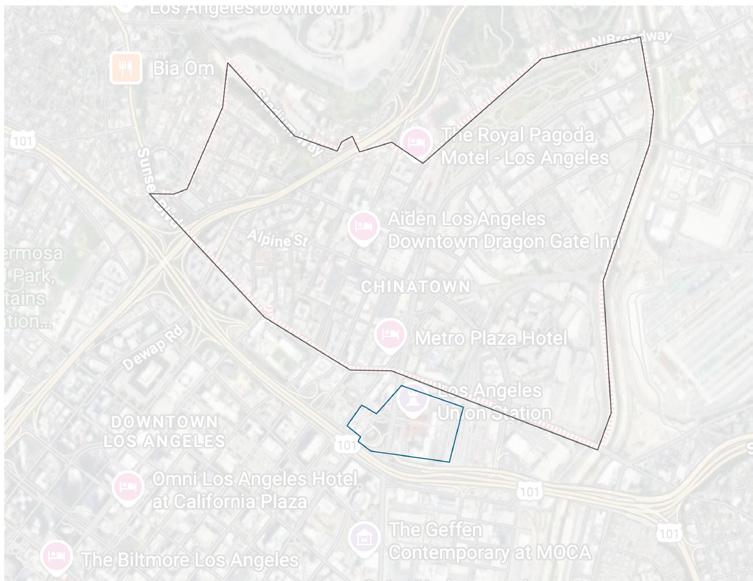

History of Chinatown

Chinese immigrants began settling in the South Cove area in the late nineteenth century, building housing, businesses, and institutions that anchored the neighborhood’s cultural life. During the 1950s and 1960s urban renewal projects and the construction of the Central Artery and Turnpike displaced hundreds of residents and carved highways through the district, disrupting the community.

In the decades that followed, residents and community organizations fought to hold onto the neighborhood’s remaining housing and commercial base. At the same time, rising land values and waves of investment incited gentrification, mak-

ing the area steadily less affordable to long-time households. Against that backdrop, repurposing underused office buildings like 73 Essex into housing offers a way to add badly needed units while keeping the existing urban fabric.

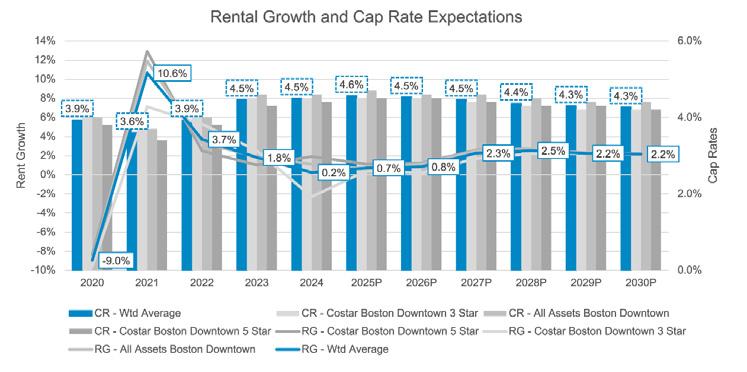

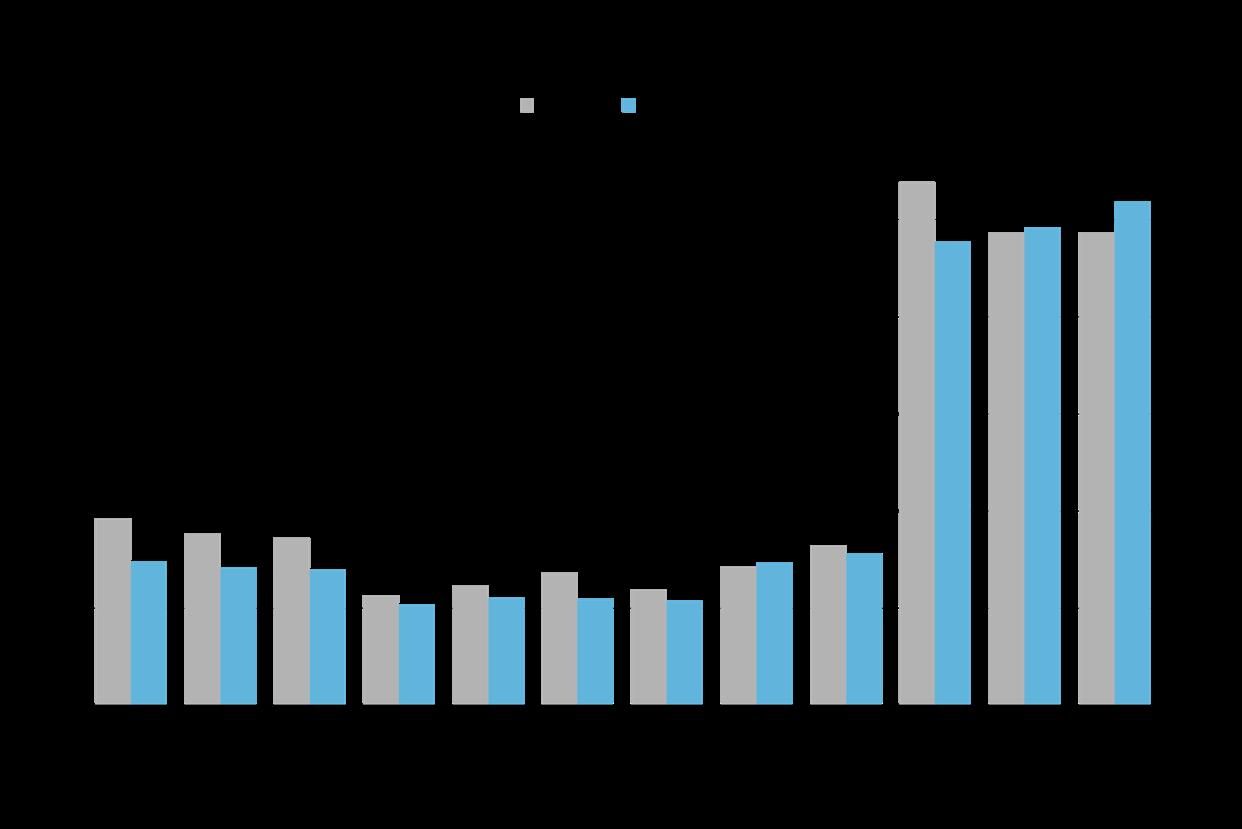

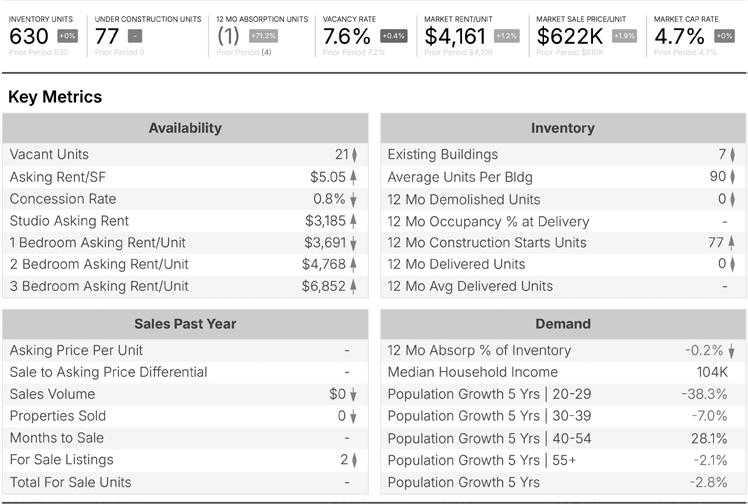

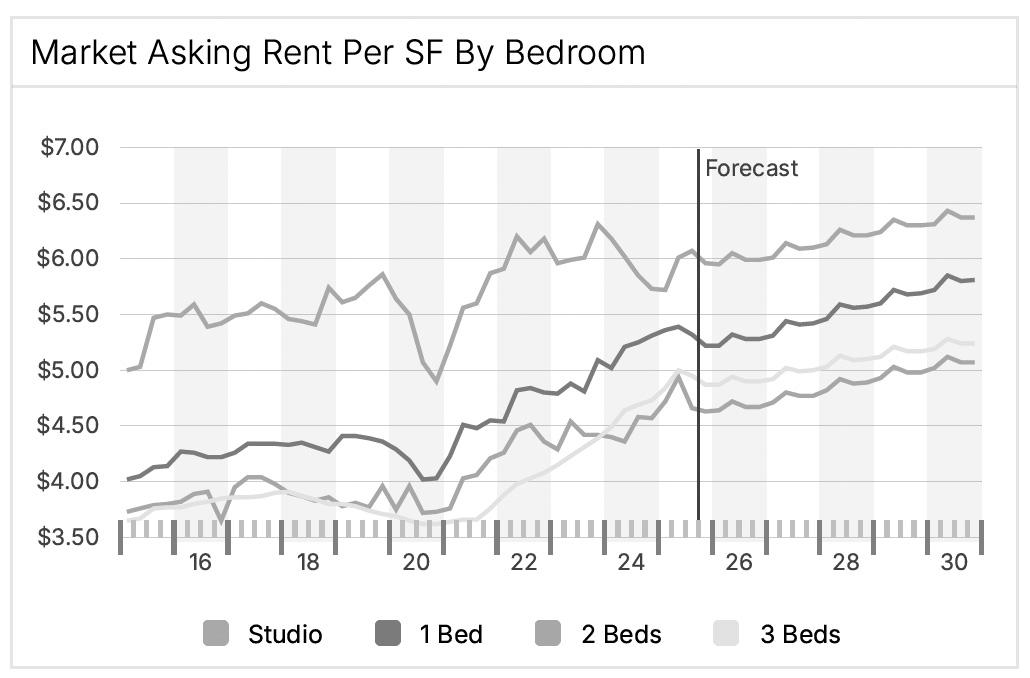

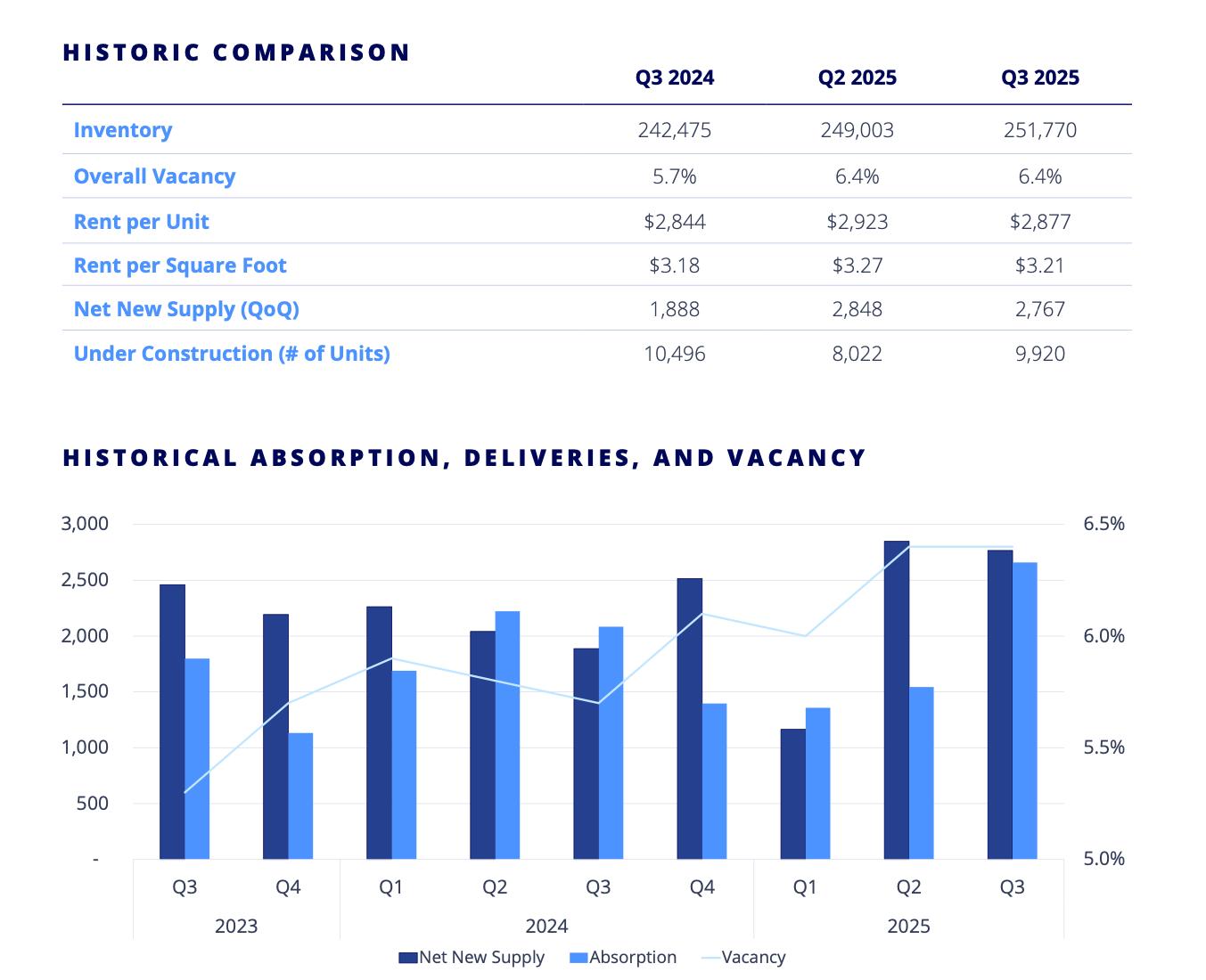

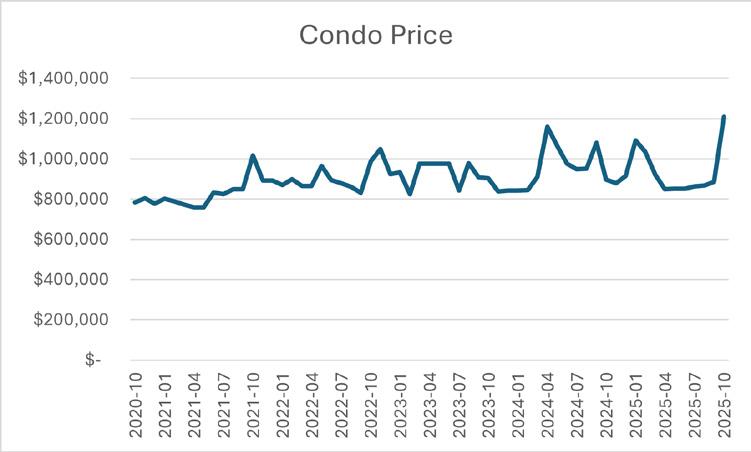

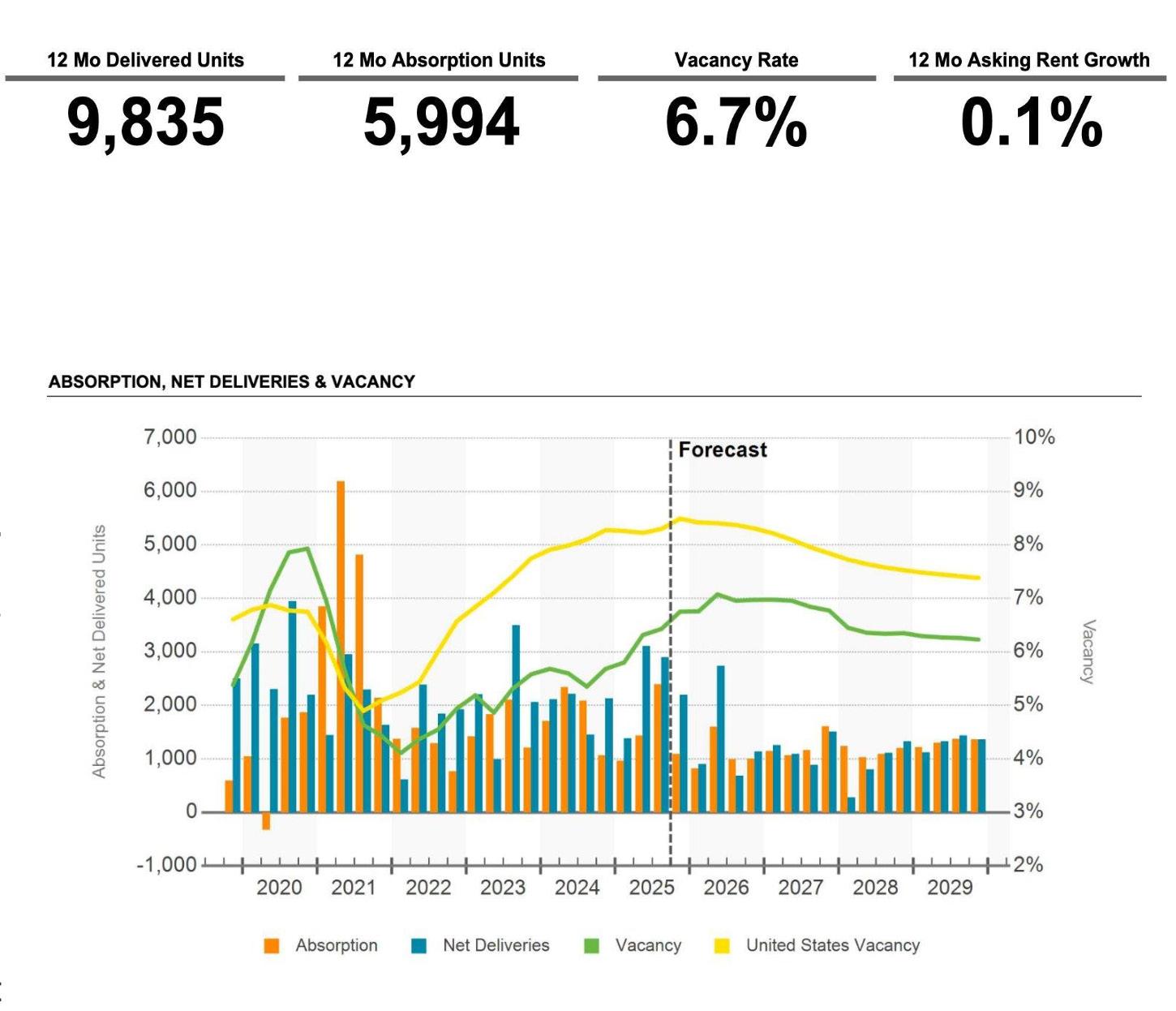

Boston Market Outlook

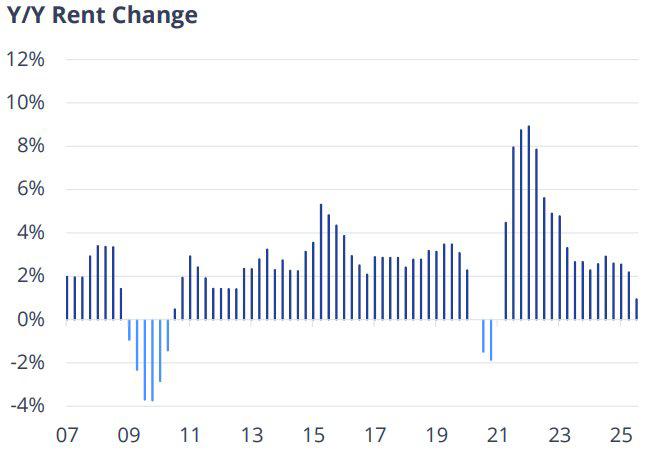

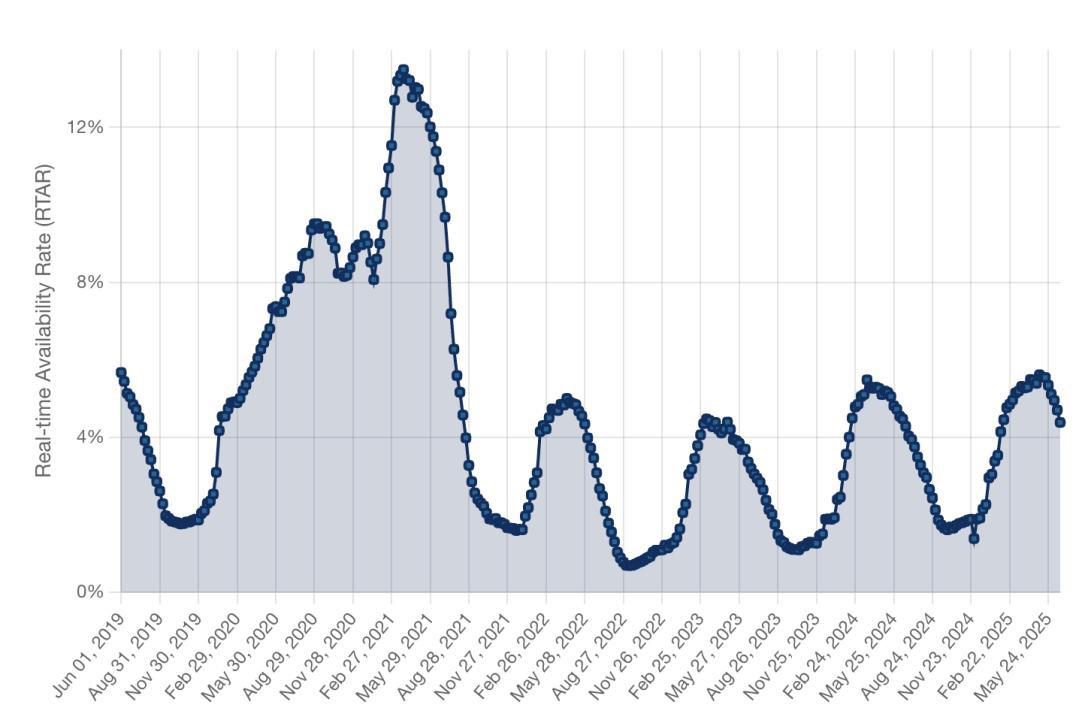

Boston’s multifamily market remains tight and relatively resilient, which underscores the need for additional rental housing. Downtown Boston has posted healthy rent growth over the past five years, with cumulative gains of roughly twenty percent2.

Vacancy in the downtown multifamily submarket has hovered in the low- to mid-single digits, averaging about five percent with a current level just over four percent, indicating that new supply is being absorbed and renters continue to favor well-located urban product2. Job growth in the metro has been modest, tracking below the national pace, but capital markets still price downtown Boston apartments aggressively, with cap rates clustered around the mid-4 to low-5 percent range and expected to remain com-

positioned to lease into a fundamentally undersupplied market.

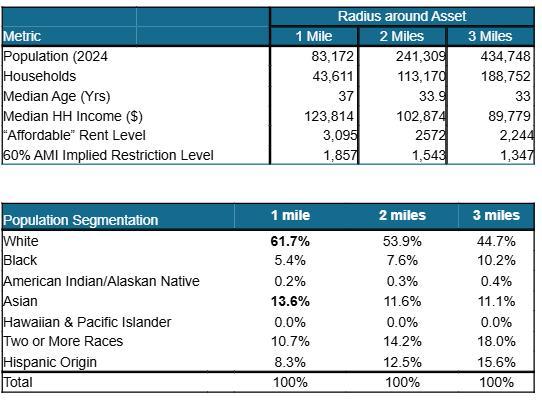

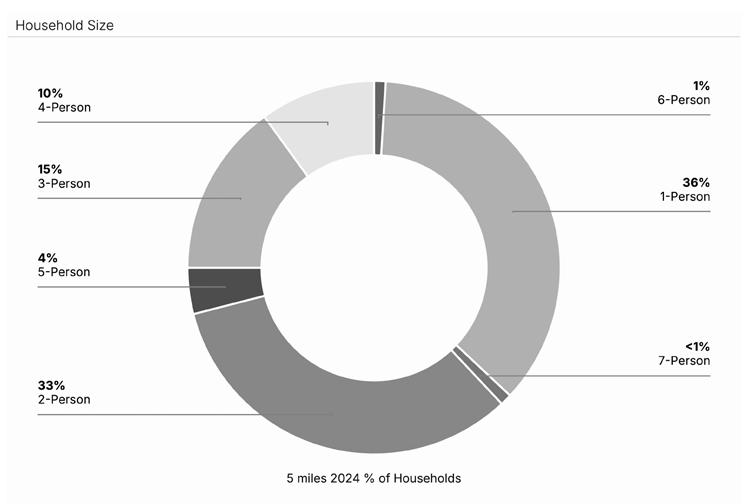

Market Stats & Target Tenants

The surrounding neighborhoods at 73 Essex are dense, relatively young, and high income, with median household incomes into the six figures within a one-mile radius to the site and strong renter affordability at levels consistent with upper-middle-income urban households. The existing housing stock in this radius skews toward smaller formats, with a large share of one-bedroom units, and the population is predominantly White and Asian, reflecting the combined influence of downtown employment, nearby universities, and Chinatown’s long-standing cultural base. In this context, the project is likely to target renters-by-choice who value proximity to the CBD and transit (young professionals, graduate students, and dual-income couples without children) along with some moderate-income households qualifying for units restricted around 60 percent of area median income.

Current Zoning & Incentives

pressed relative to many other markets. In this context, new, well-designed units created through office-to-residential conversions are

The site sits in a Community Commercial zoning district, with allowable heights in the roughly 80- to 100-foot range and floor area ratios on the order of six to seven. On top of the base zoning, Boston’s Office to Residential Conversion Program layers on a set of powerful incentives: a long-term property tax abatement

of 75 percent for 29 years, an expedited permittin track that targets building permit issuance within roughly twelve months, and a step-down in the tax rate when an asset shifts from office to residential use. Together, the underlying entitlements and these programmatic benefits reduce entitlement risk, improve after-tax cash flow, and make an adaptive reuse of 73 Essex more feasible.

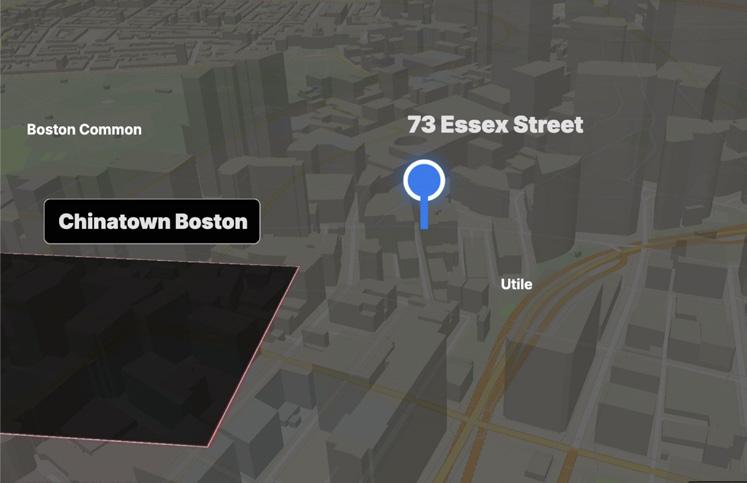

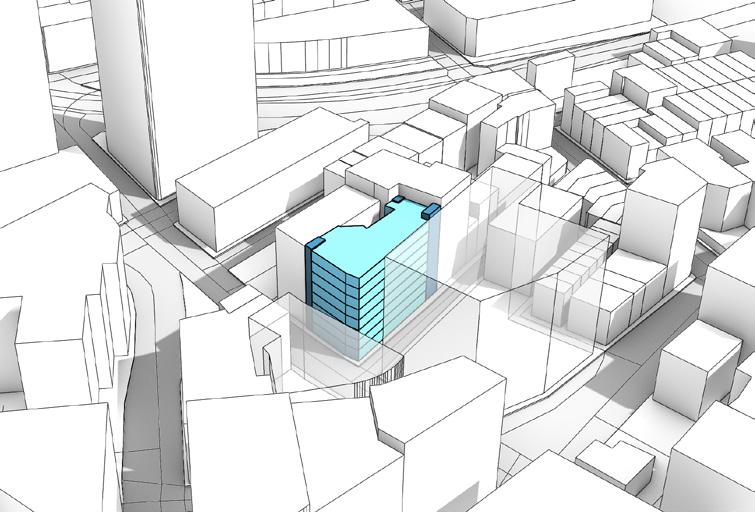

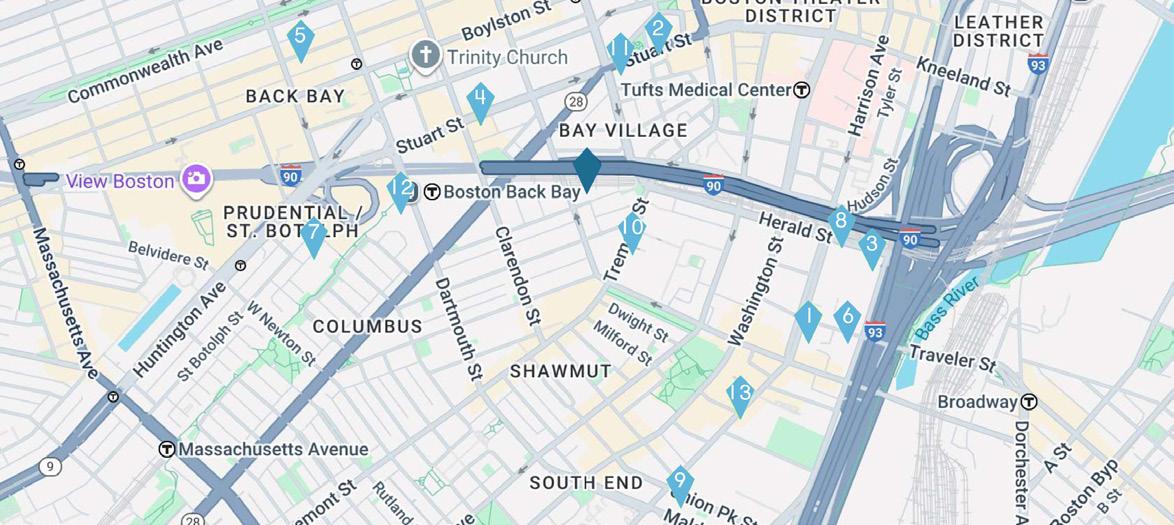

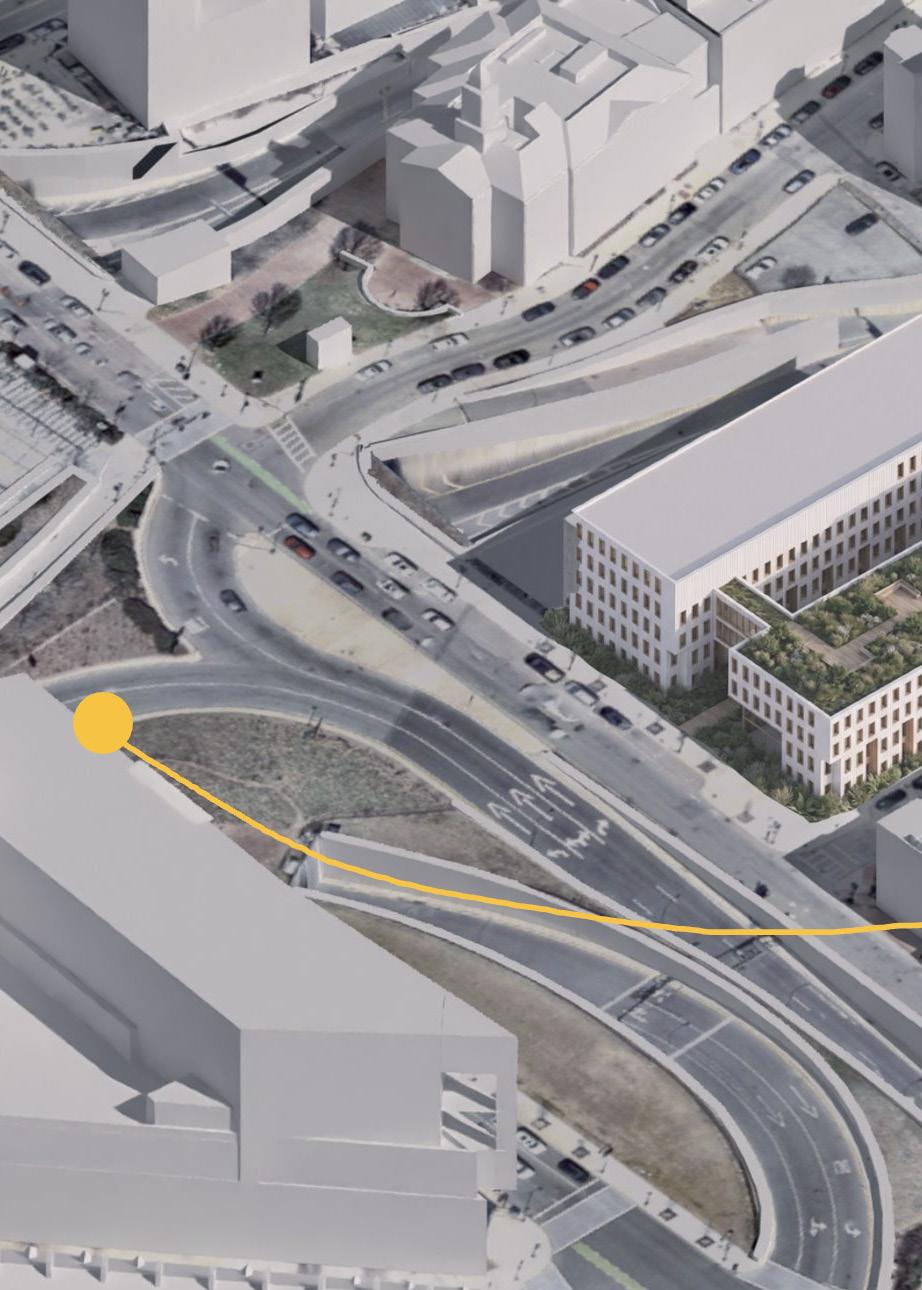

Site

Zooming into our site, located at 73 Essex Street in Boston’s Chinatown, the parcel sits at a pivotal edge condition — a few blocks aways from Boston Common. Its position places it just outside the densest core of Chinatown, yet within clear reach of its commercial and cultural energy.

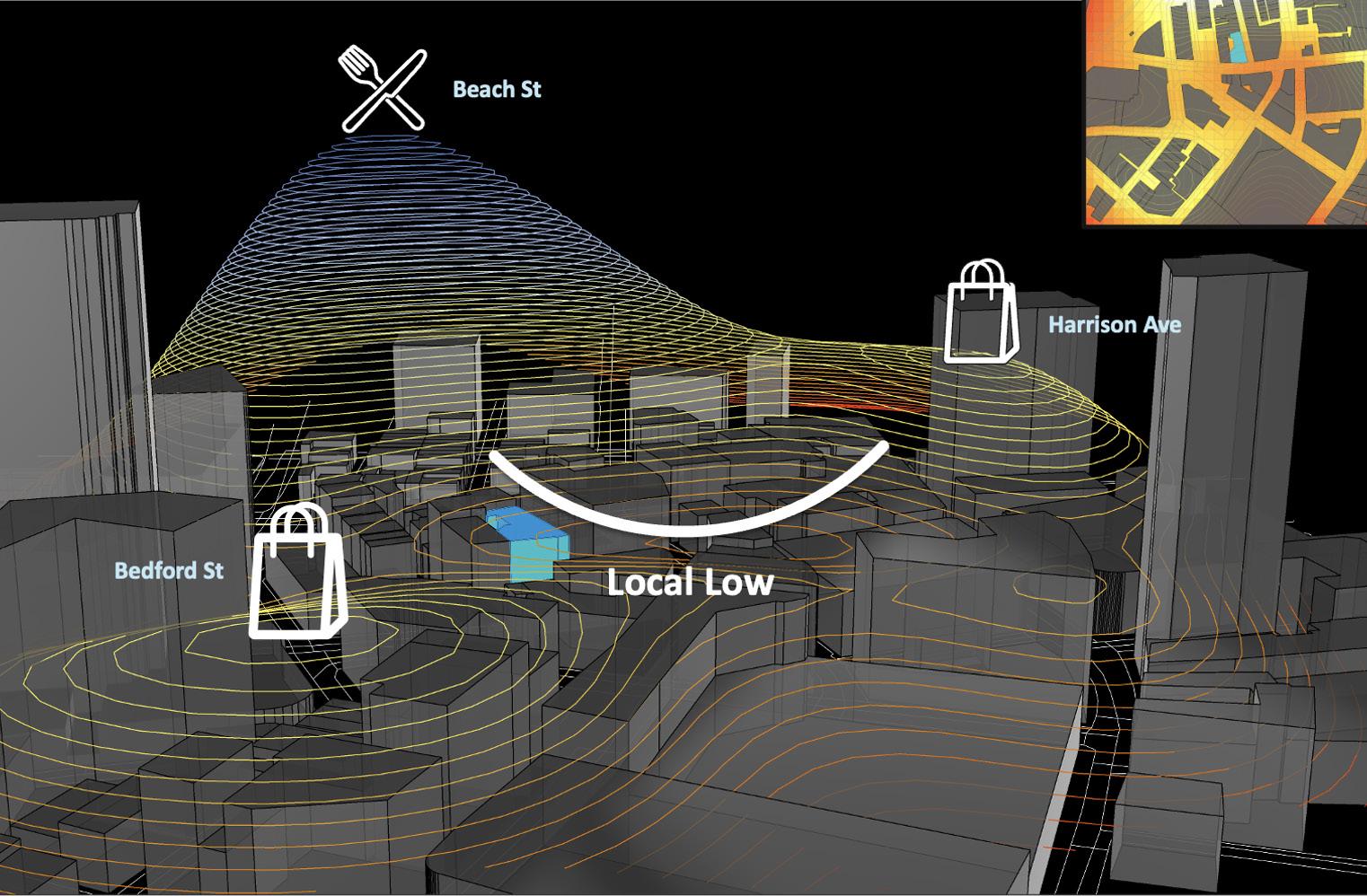

The existing building presents a Chicago School–influenced Beaux-Arts façade, occupying roughly one-third of the block. Its architectural expression recalls a period of classical commercial urbanism, yet the ground floor currently remains vacant, signaling an underutilized urban

frontage with potential for reconsideration. To contextualize its surroundings, we examine a 3D heat map of ground-floor activation in the neighborhood. Areas such as Beach Street, Harrison Avenue, and Bedford Street register high levels of street-level engagement. By contrast, our site falls within a local low zone of activity — a quieter stretch with limited

pedestrian draw and minimal ground-floor programming.

Our takeaway is clear: ground-floor activation is not merely a compliance measure required for tax abatement. Rather, it represents a strategic opportunity — a means to reinvigorate the street edge, enhance neighborhood vitality, and ultimately generate value for both the development and the community.

Design Strategy

Introduction

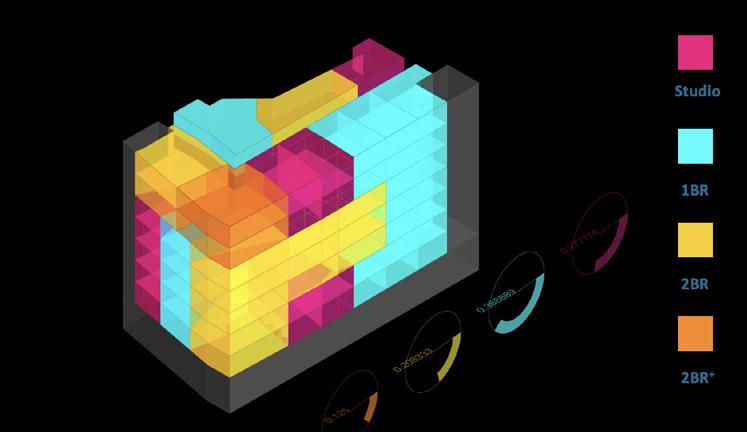

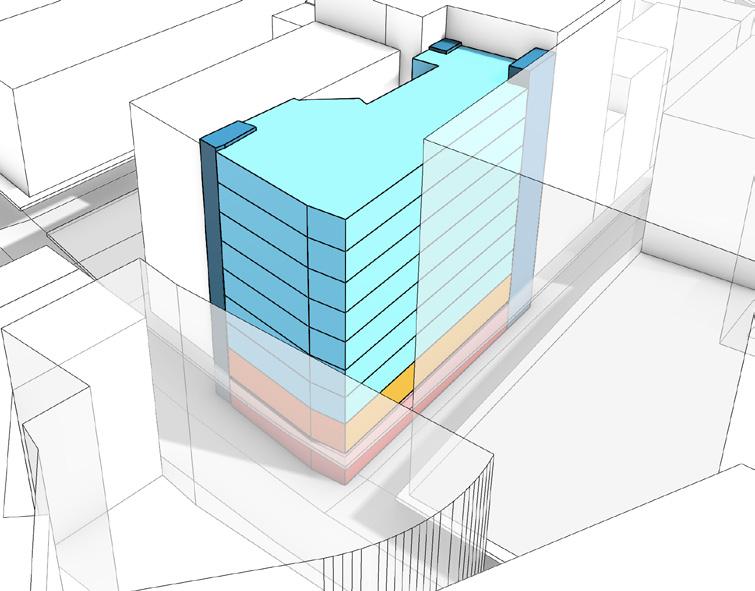

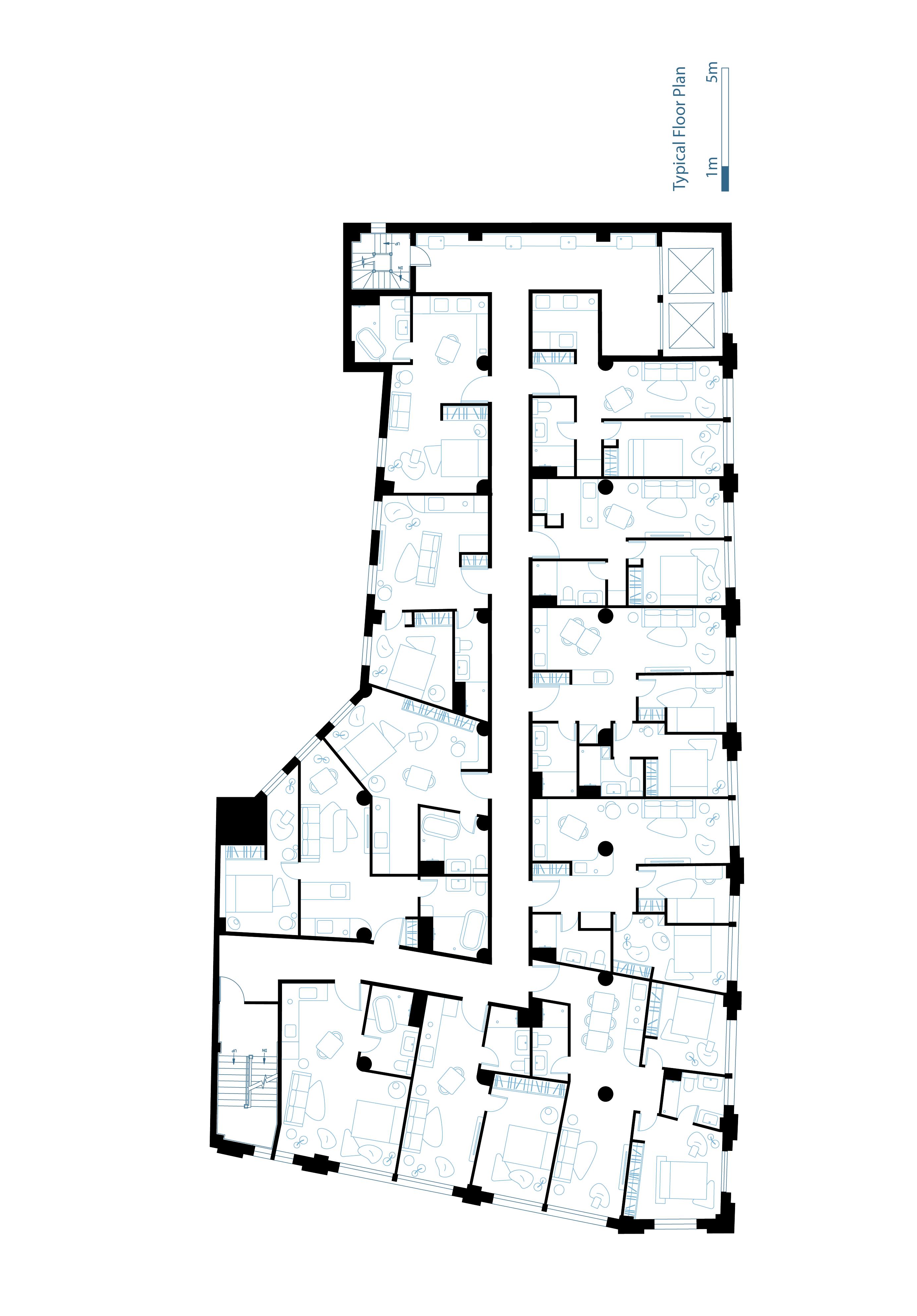

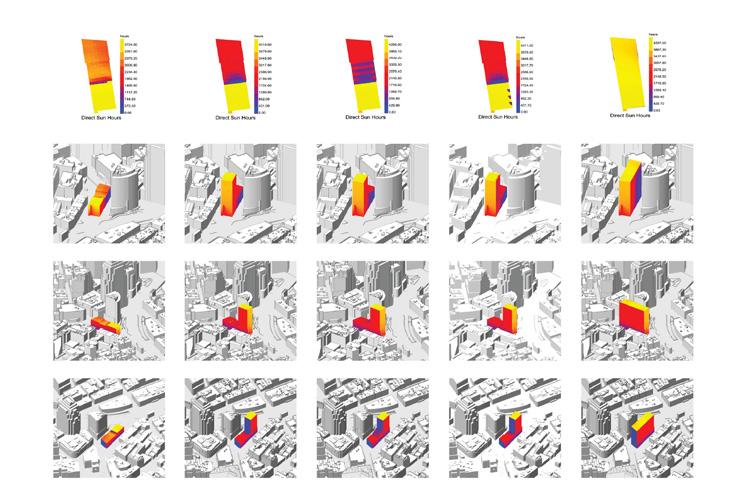

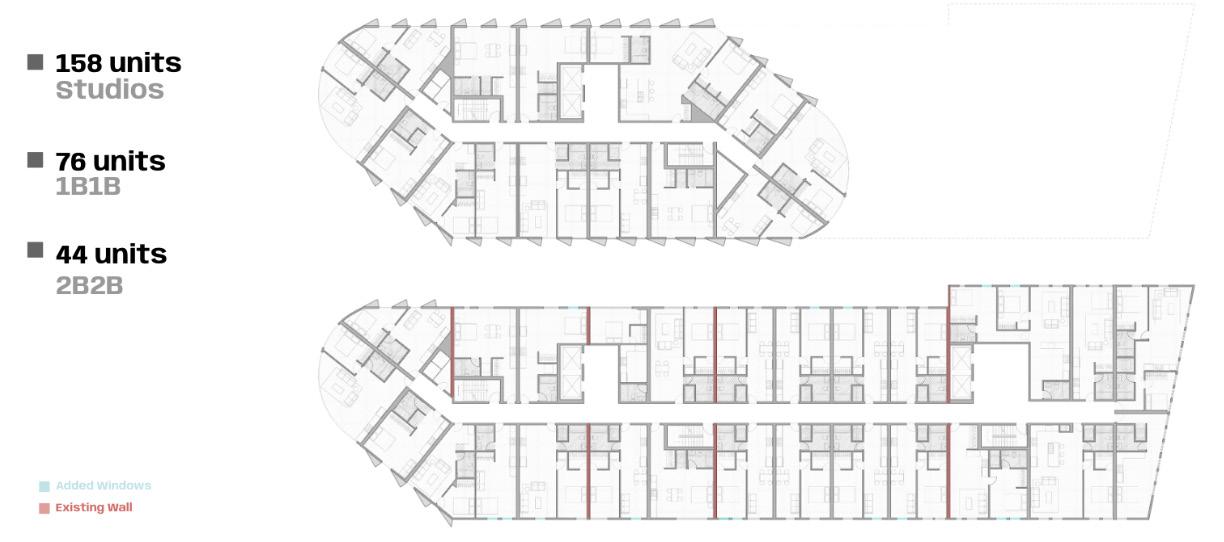

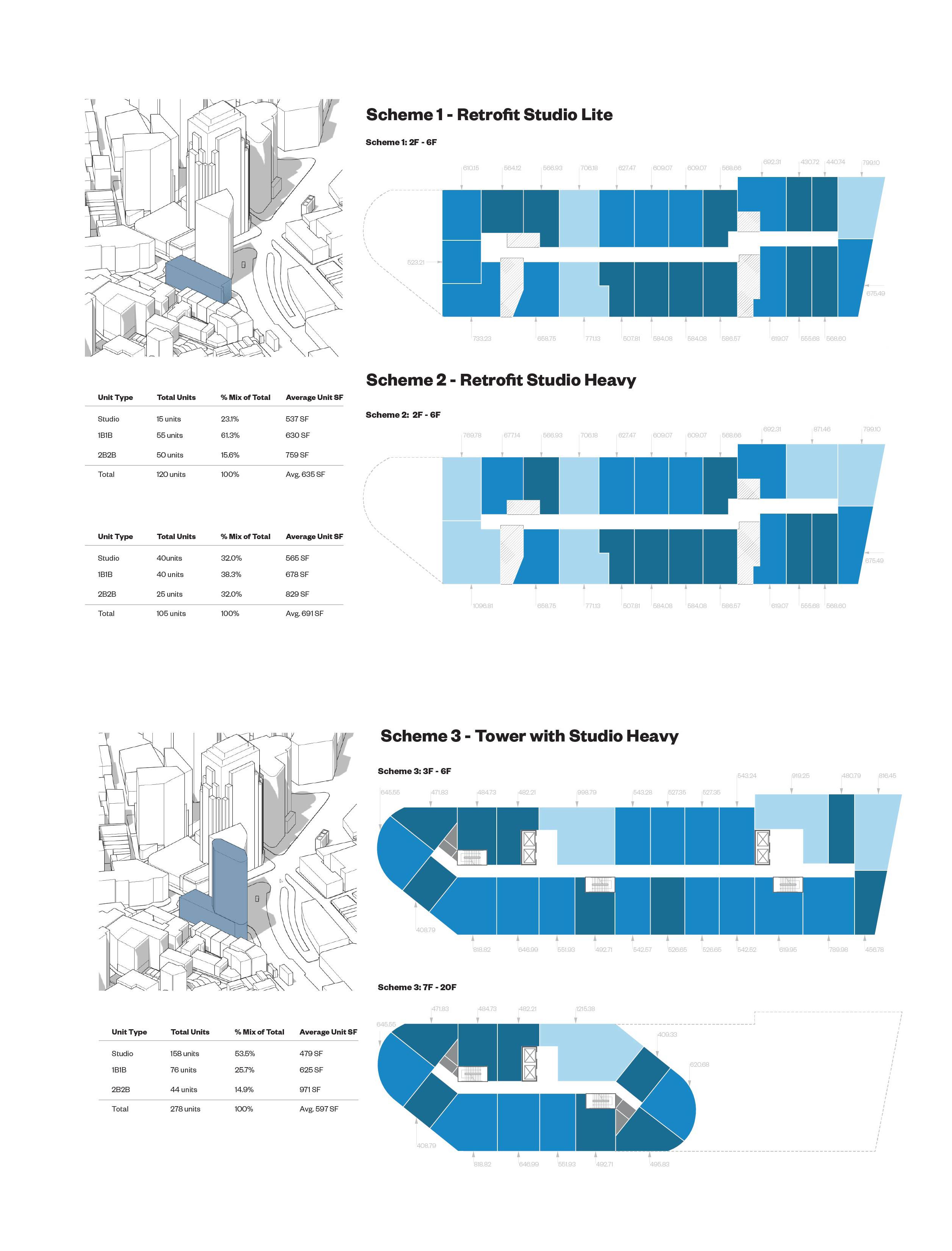

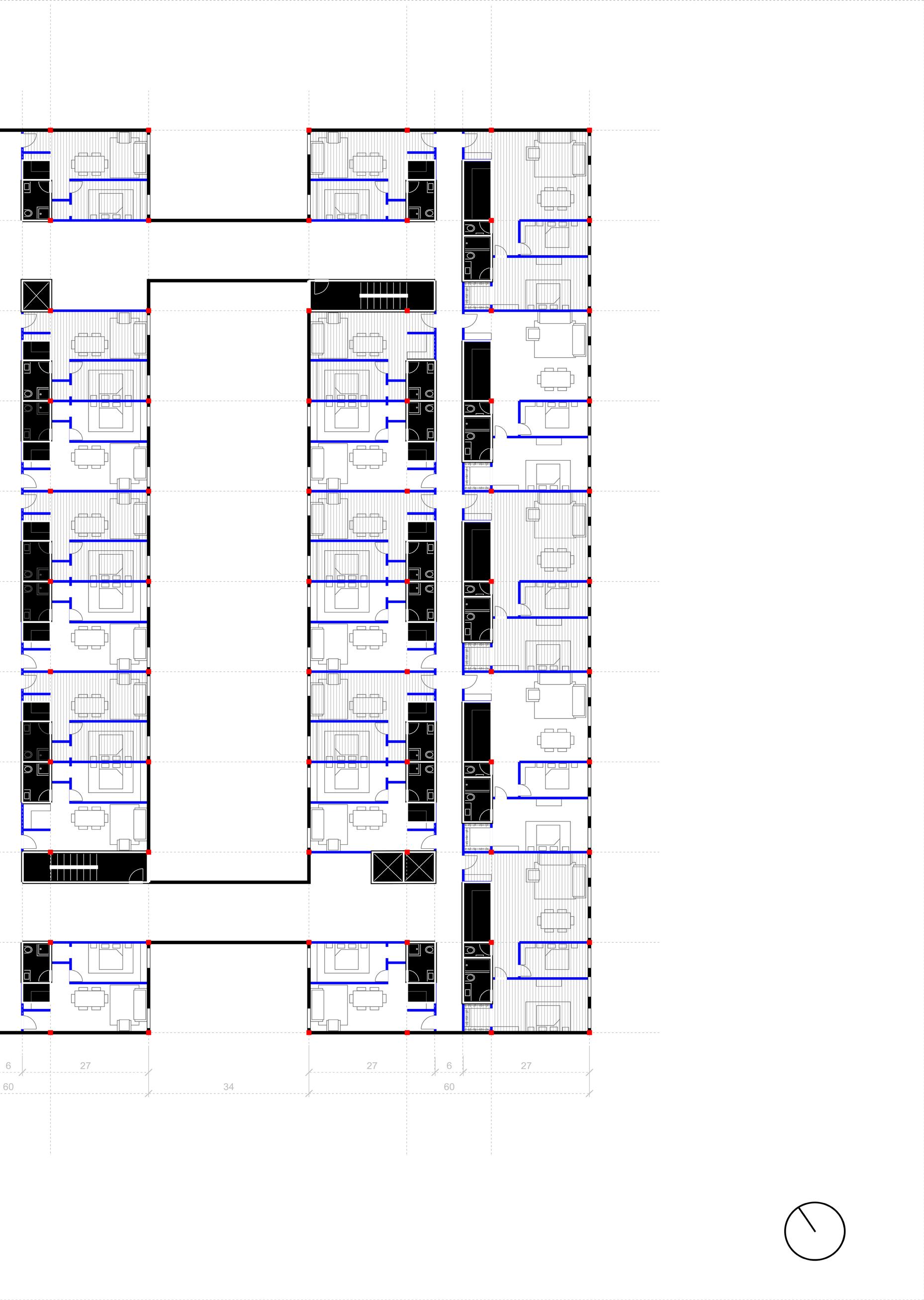

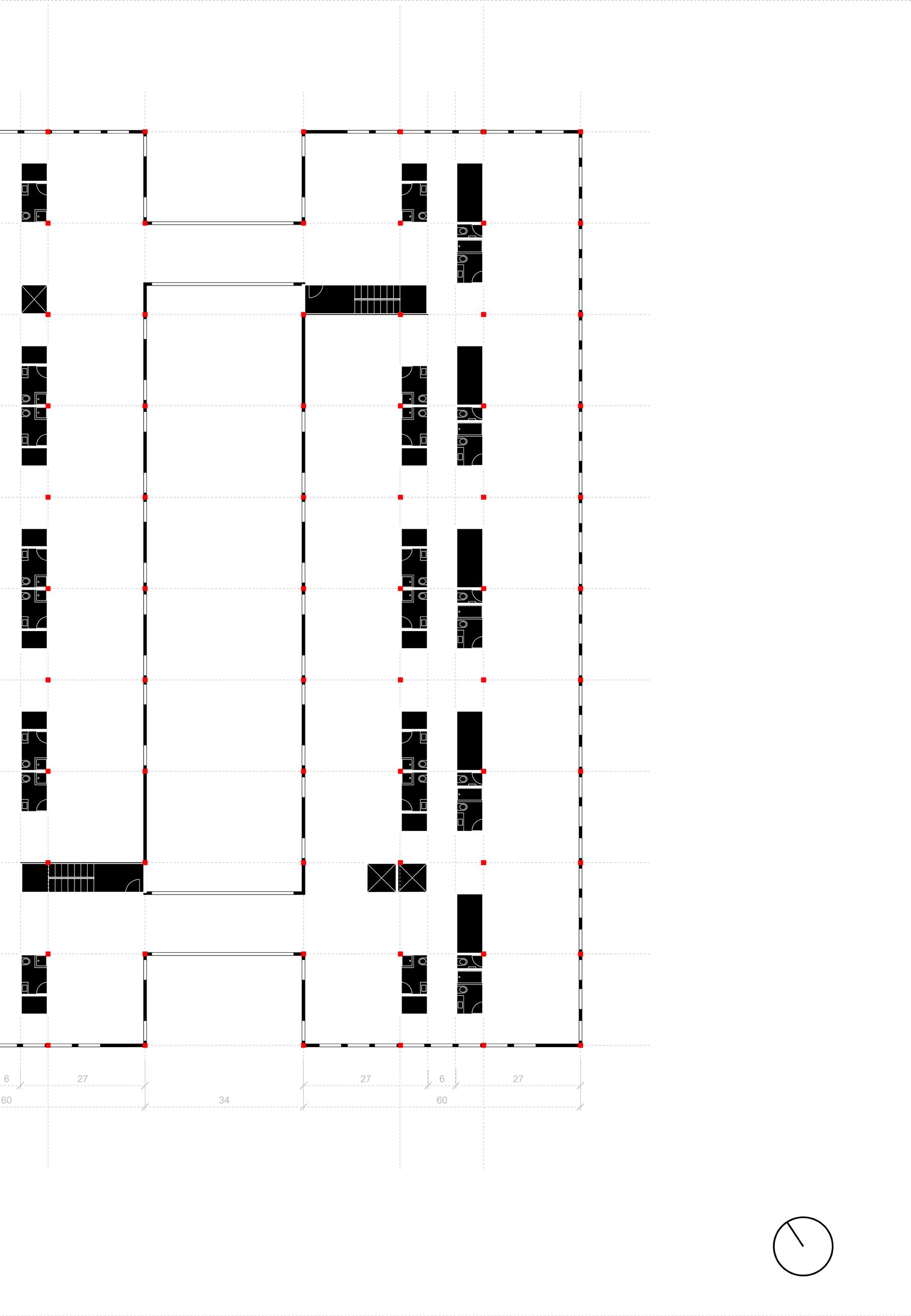

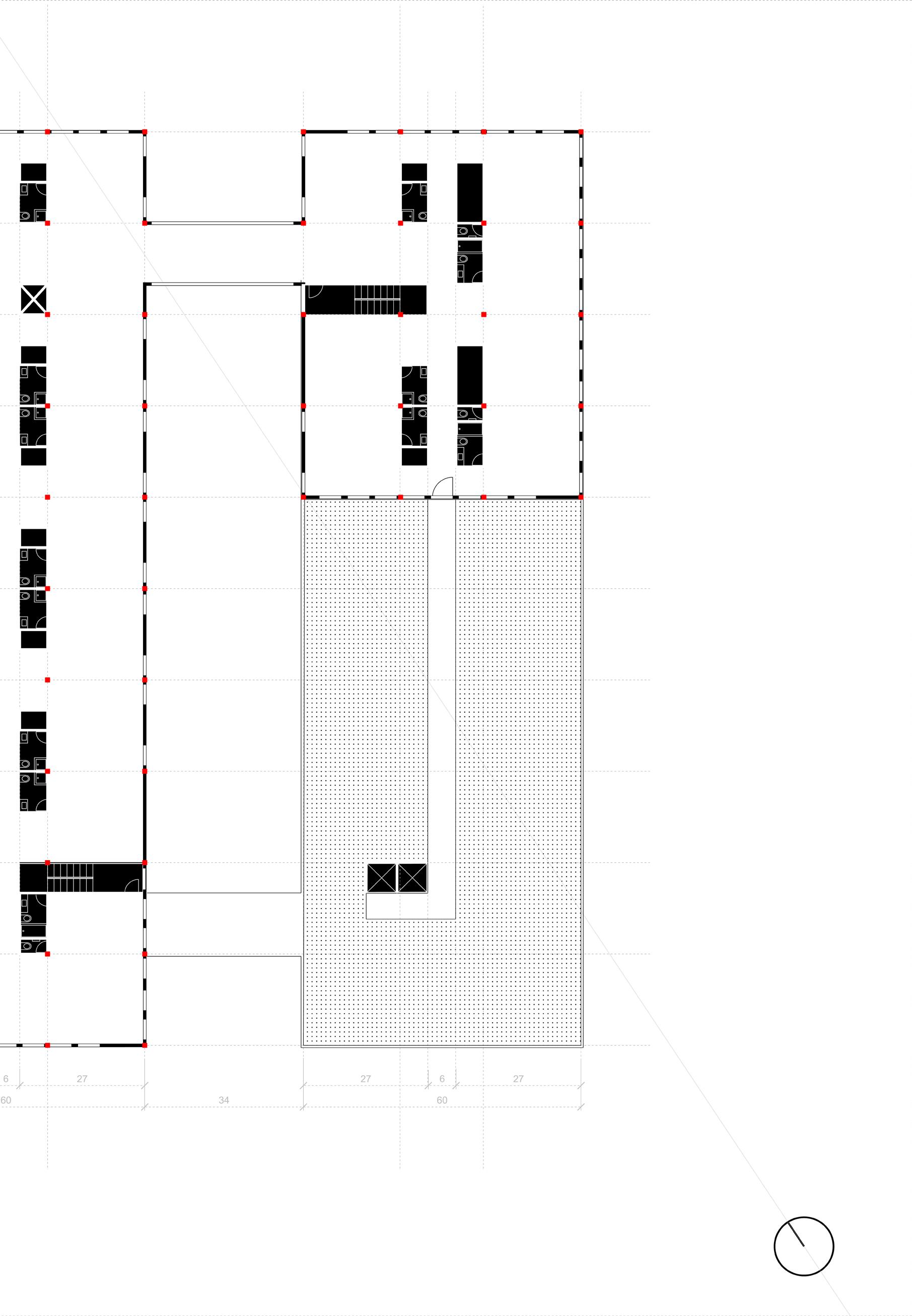

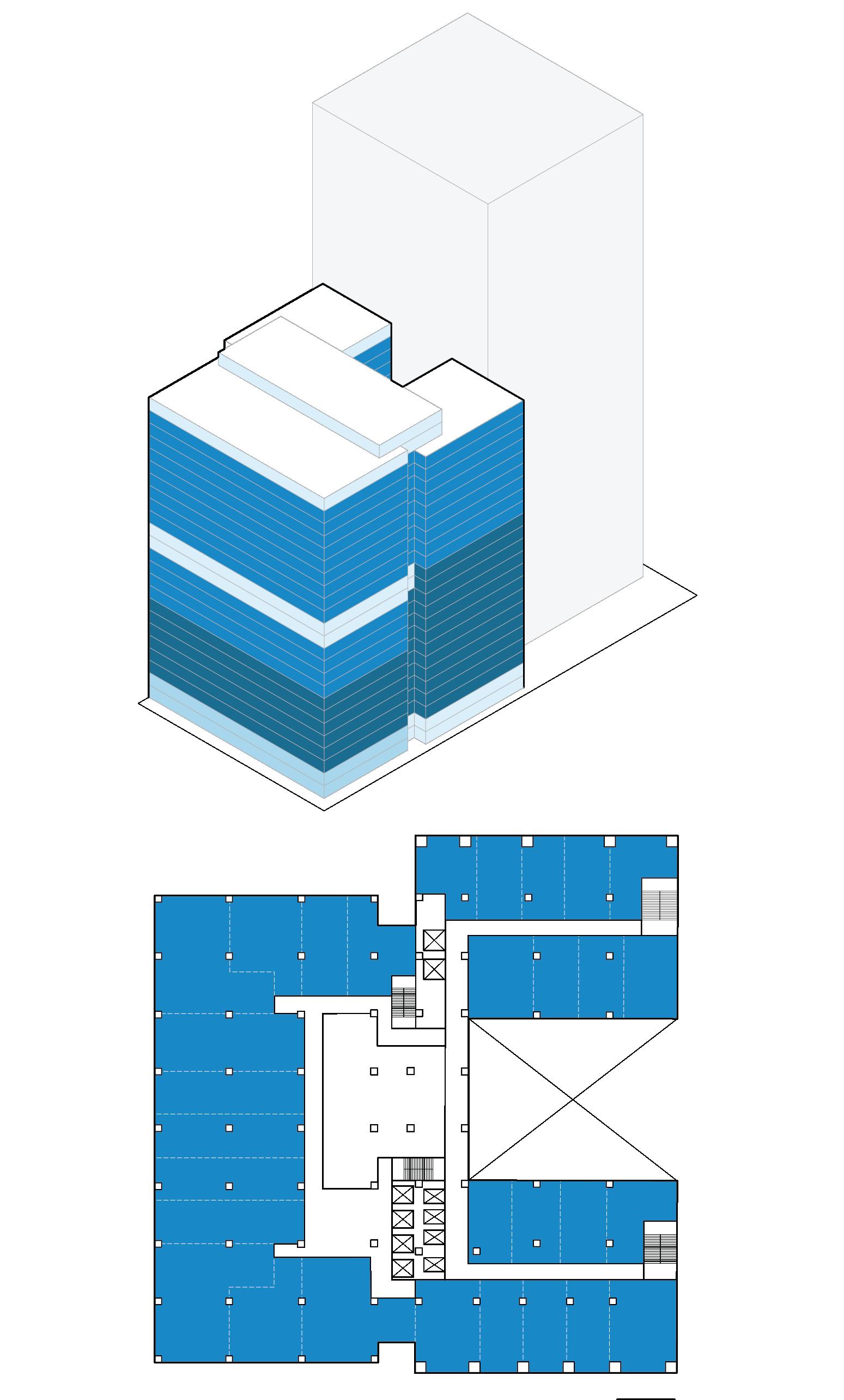

Jumping into the design chapter, we frame the process through three essential questions: What is the massing? What is the layout? And what is the style? For each question, we developed a computational model designed to help us rigorously evaluate options and arrive at defensible decisions.

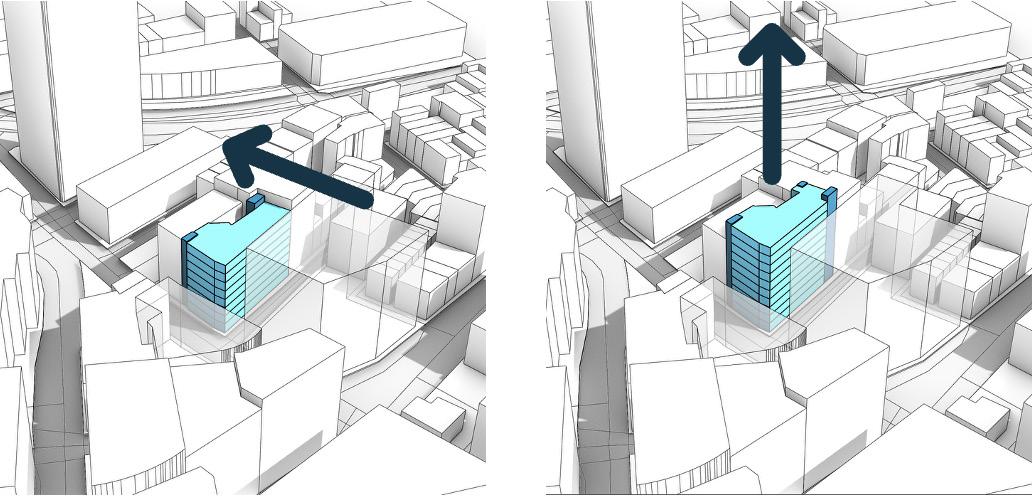

Massing

When first exploring massing strategies, we tested multiple scenarios — relocating the core to the least active edge of the site, or adding two additional floors to reach the zoning height cap. These moves were focused on increasing unit yield and driving more favorable returns. However, none of the expanded envelopes proved financially viable.

We therefore maintain the original building envelope, which reduces our spatial freedom and demands a highly strategic approach to floor area allocation and sensitivity to market.

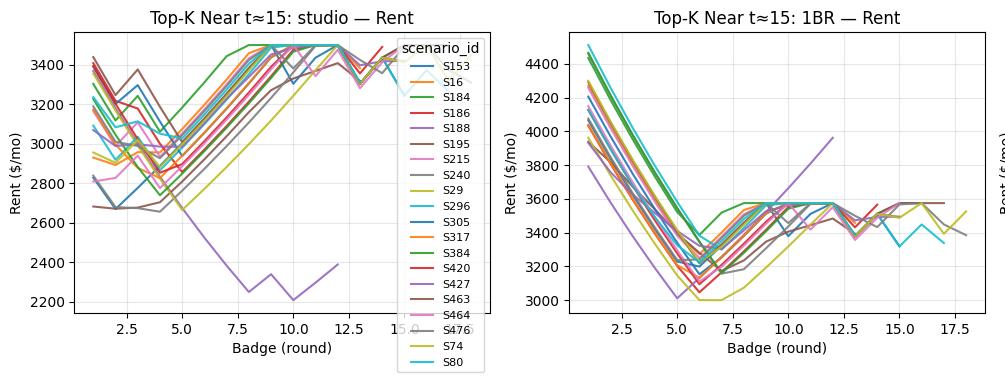

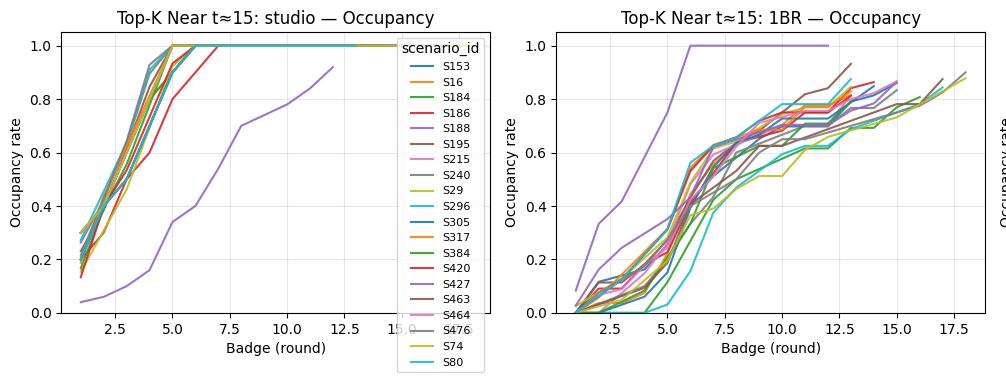

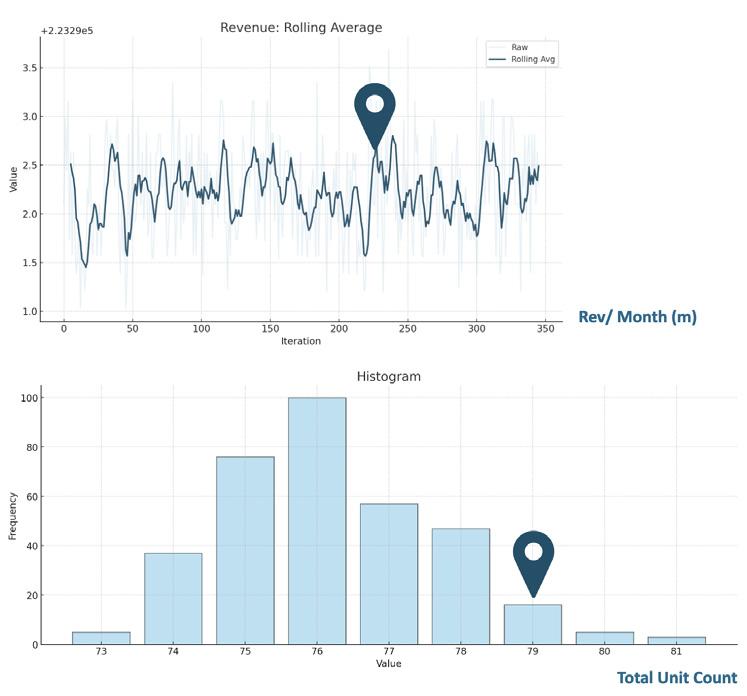

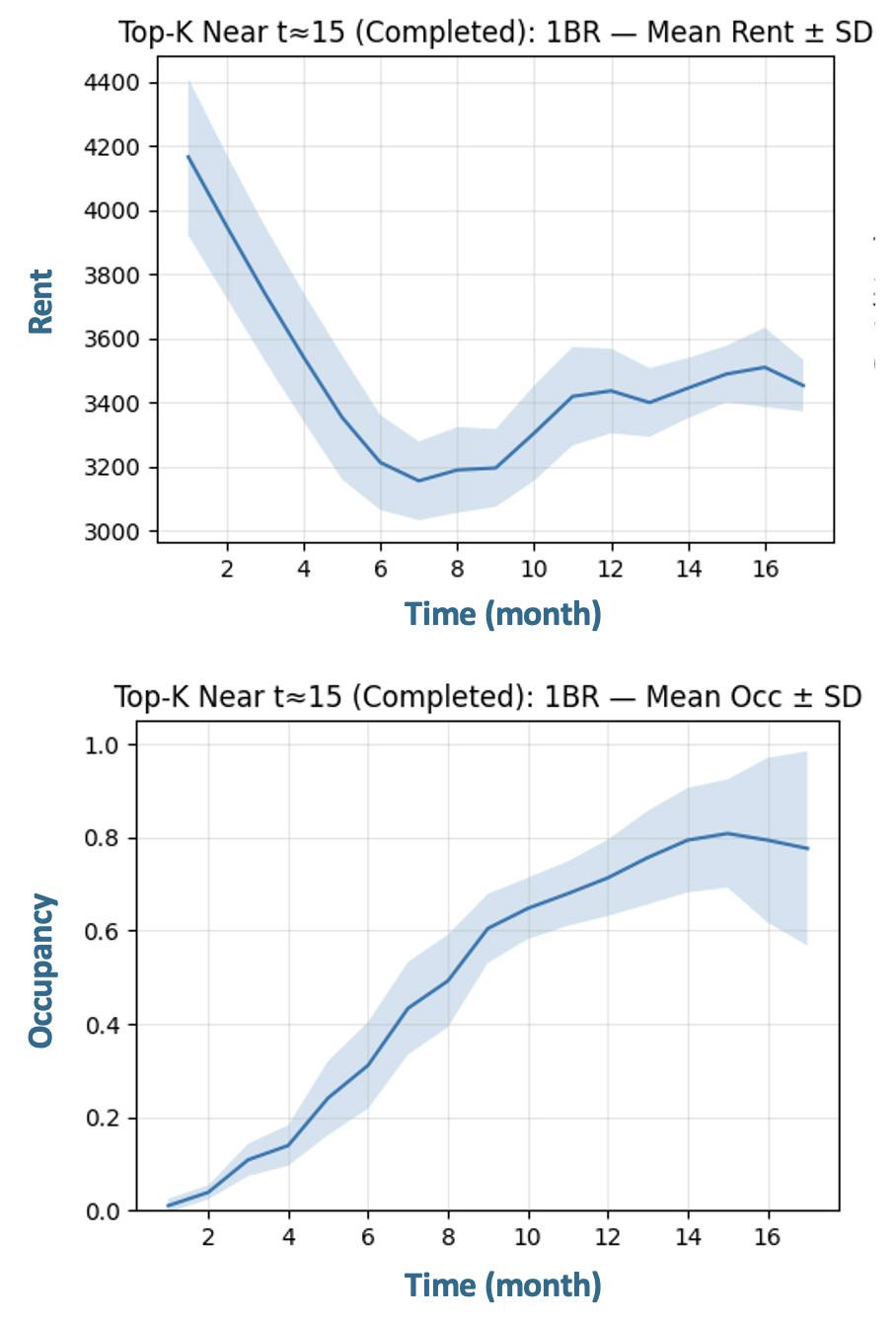

To navigate this challenge, we built a machine-learning–based agent model that simulates market response to our design proposals, providing insights on stabilized rent and occupancy with the timeline. This model establishes a baseline economic feedback loop that remains active throughout the design process.

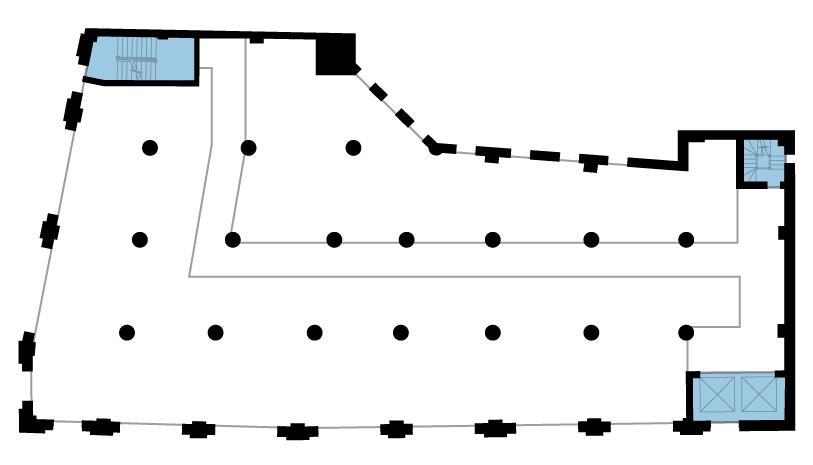

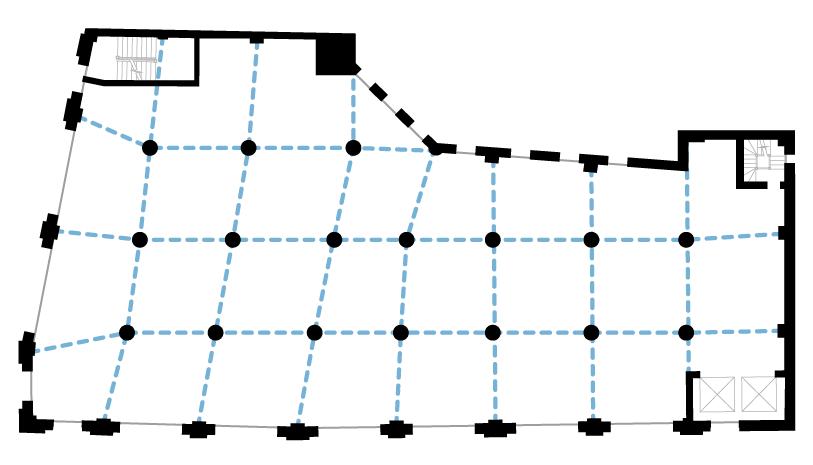

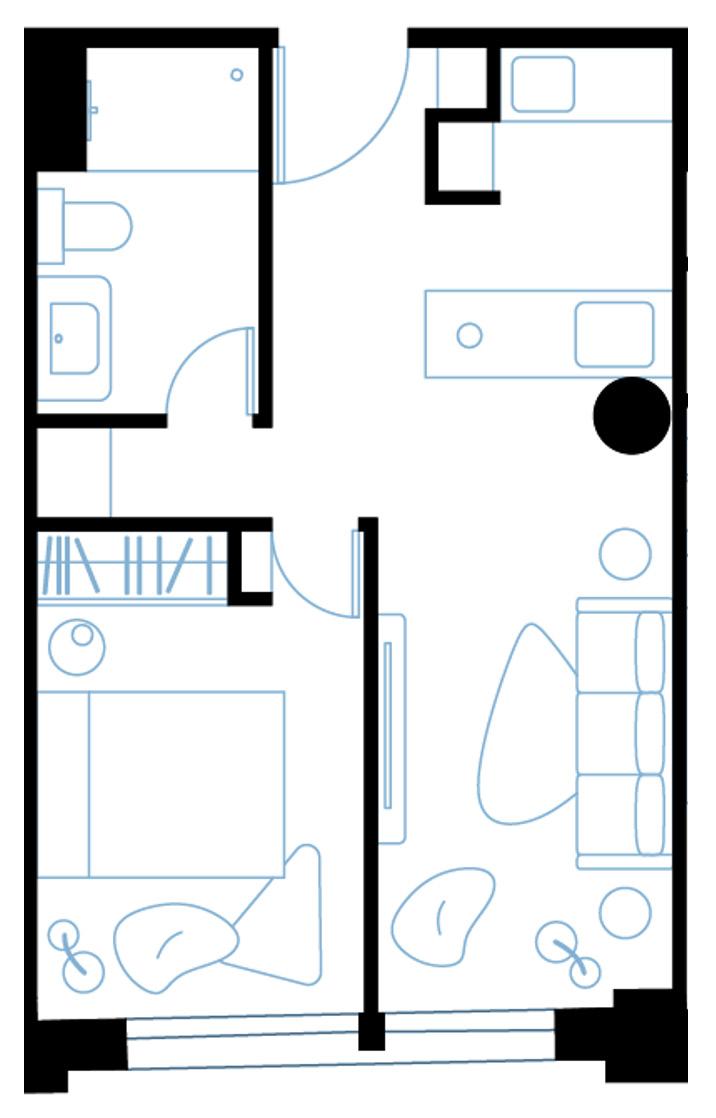

Layouts

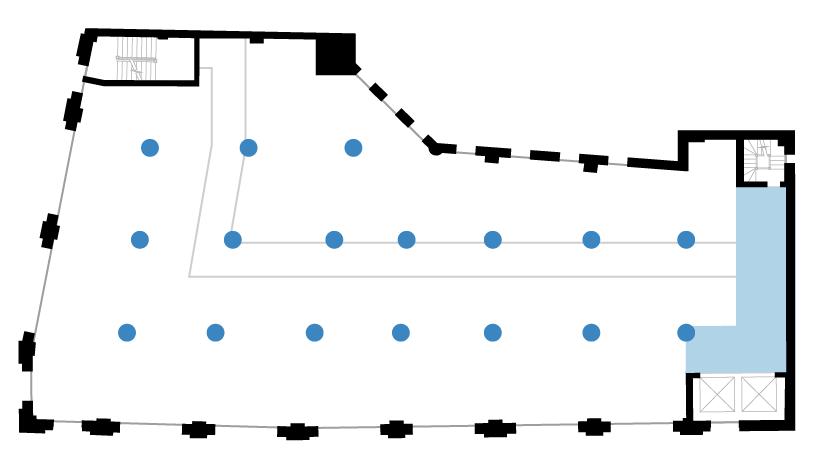

Turning to layout, we inherit a floor plan with three separated cores pushed into different corners of the structure and a non-orthogonal column grid — conditions that compromise both efficiency and usability. Our approach was to generate a series of plan variations, testing how each manages circulation, structure, and unit performance.

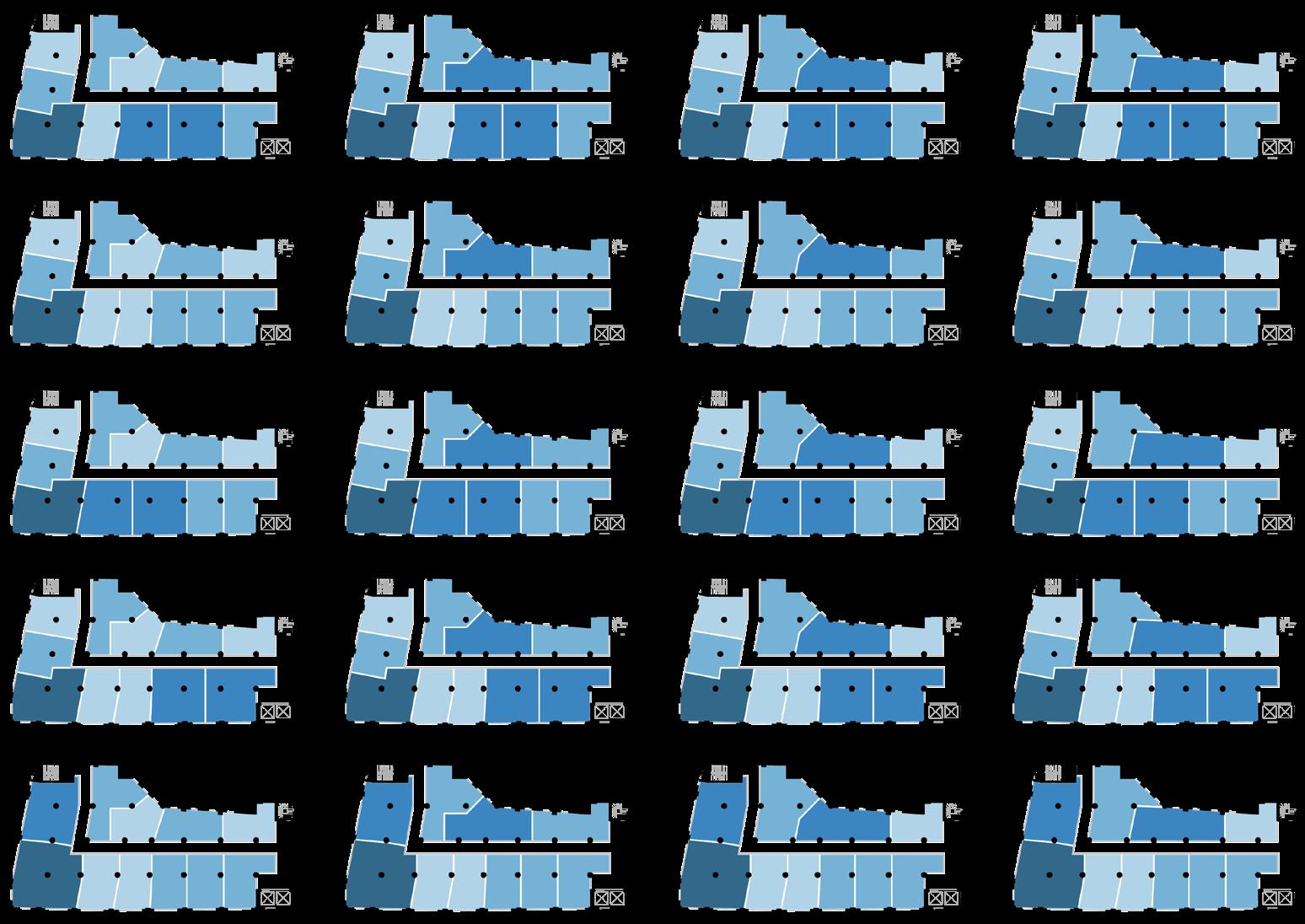

We selected 20 top-performing candidates and fed them into a custom genetic algorithm optimizer. The optimizer iteratively recombines and evaluates these solutions, seeking the scheme that maximizes revenue potential and unit count while balancing risk exposure in the marketplace. This process led us to a scheme defined by a strong one-bedroom mix, complemented by two premium two-bedroom units on the upper floors and a carefully balanced distribution of studios and standard two-bedrooms. It consistently outperformed other candidates in both projected

Genetic Algorithm Optimizer: Coded and deployed for the project to select most competitive floor plan layouts and combinations.

revenue and feasible unit count, while maintaining a measured risk profile — a “sweet spot” in the probability universe.

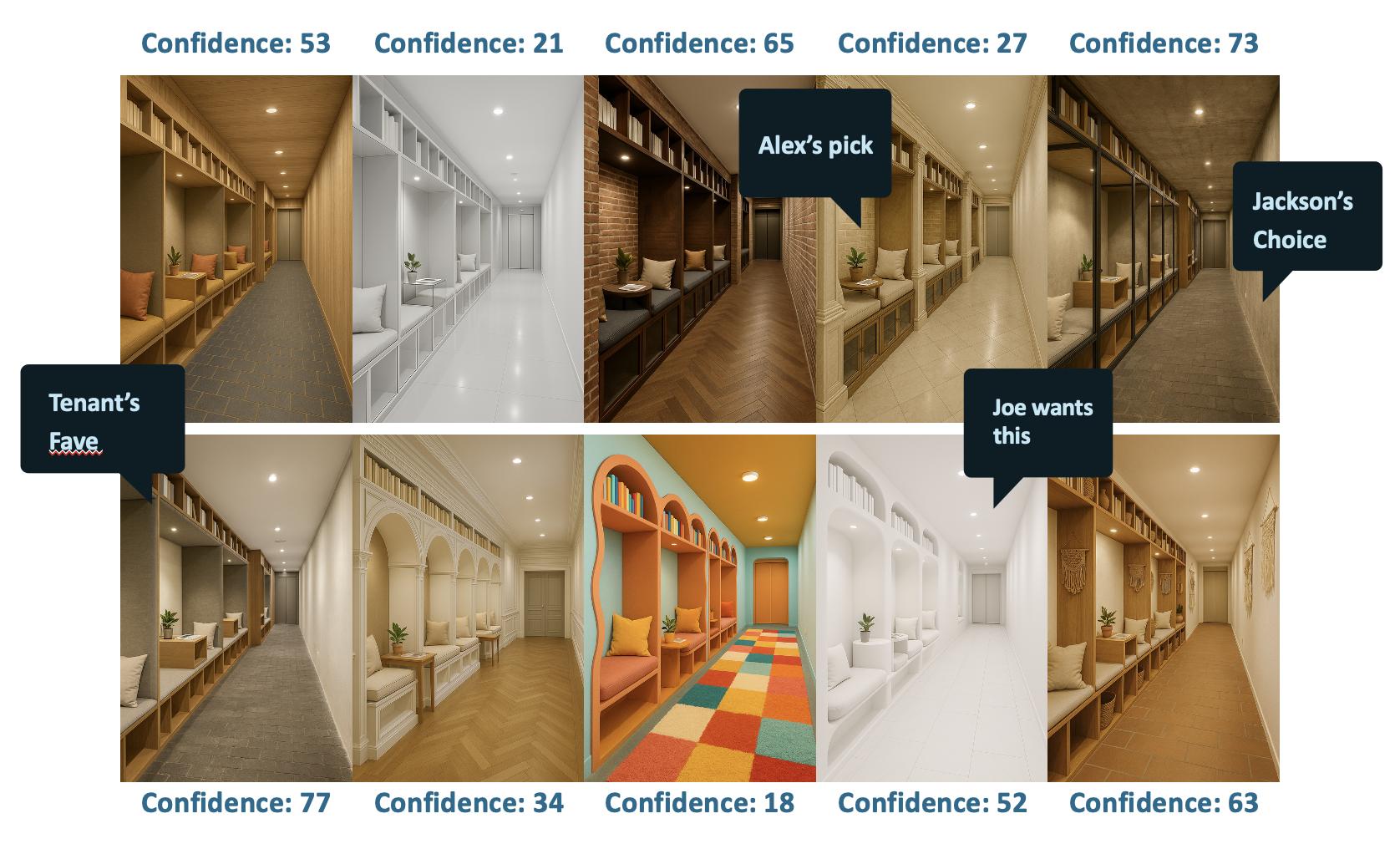

Style

Finally, we ask: What is the style, and how will people feel inside these spaces? The building’s large, rounded structural columns resist concealment, and the wide existing corridors present challenges — yet also opportunities. We embraced the generous hallway as a shared amenity zone for remote work and casual social interaction, reflecting contemporary lifestyle needs.

From the very earliest stages, we integrated real-time rendering into the plan development process, allowing interior qualities to directly inform spatial decisions. These qualitative assessments loop back into our agent-based sentiment model, which functions as a predictive tool for tenant preference and environmental appeal.

For the amenity hallways, we developed ten distinct interior design style packages, each evaluated through automated sentiment analysis to estimate market receptivity. Importantly, sentiment scoring is not a prescriptive driver — but a decision-support indicator, guiding design and development teams toward choices that are both spatially compelling and market-aligned.

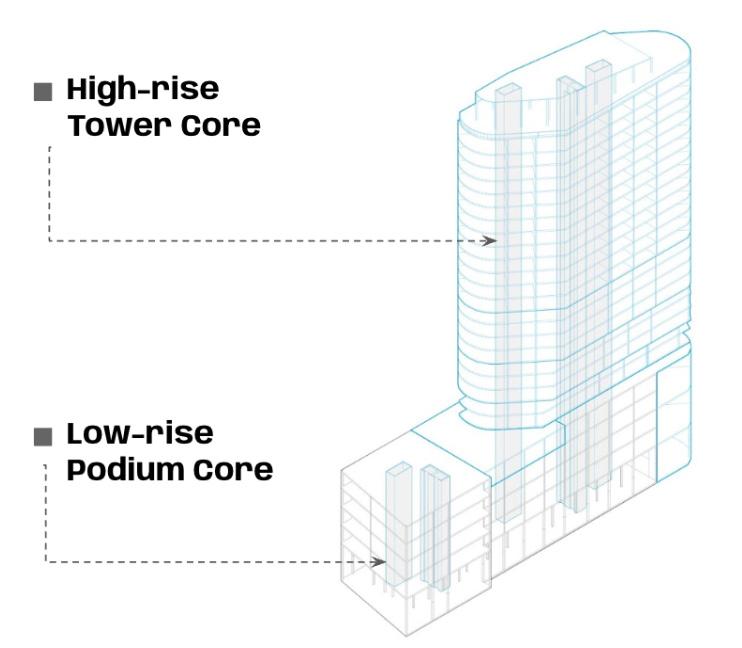

Building Programming

In the final proposal, floors two through eight are dedicated to residential use. The basement level is allocated as tenant-focused amenity space, including rentable storage units that

support everyday convenience and contribute to overall building value.

Ground Floor Strategy

At street level, the design introduces a flexible retail environment. During daytime hours, the ground floor operates as an open-plan café and co-working space, encouraging casual activation and contributing to the public realm. After 6:00 PM, as office workers leave the district and residents return home, the space transitions to a tenant-exclusive amenity. It becomes a secure, community-serving zone — a place for gatherings, children’s birthday parties, and everyday social life.

Additionally, the venue can be rented for special events, local workshops, or community programming, ensuring that the ground floor supports both economic productivity and neighborhood vitality.

1BR unit plan with market simulation in stabilized rent and occupancy rate

Structure and Façade

Our floor plans strictly follow existing structural column grids and preserve the rhythm of the historic façades. This approach minimizes

costly structural intervention while maintaining architectural integrity. At the same time, we ensure that unit layouts remain proportionate and livable, carefully navigating spatial constraints to optimize the residential experience.

Unit Economics

Zooming into the one-bedroom typology, the units are modest in size, reflecting the constraints of the existing building. However, based on outputs from our market-simulation model, rents for this unit type stabilize at mid-market pricing, driving higher projected occupancy rates compared with larger one-bedroom alternatives. In other words, these units strike a performance balance — financially efficient, market-attuned, and highly leasable.

Design Conclusions

Across this study, our intent has been to show that design and finance are not opposing forces, but interdependent systems that must be evaluated together. The computational tools we built — from agent-based market simulations to genetic optimizers and sentiment-informed style assessments — do not reduce design to numbers; rather, they clarify the implications of our choices and ensure that every move is grounded in both economic reality and human experience.

By applying equal rigor to massing, layout, and style, we establish a workflow where qualitative ambition and quantitative discipline continually shape one another. Market response guides spatial allocation, interior character informs plan geometry, and emotional resonance loops back into feasibility. This calibrated feedback loop transforms design into a way of testing futures rather than simply drawing them.

Above all, our process reflects a belief that datadriven design is only meaningful when it elevates lived experience. We use computation to protect spatial quality within tight constraints — making modest units livable, corridors social, and amenities responsive to both Chinatown’s rhythms and residents’ needs. In a context defined by tight envelopes and unforgiving pro formas, the challenge is not just making the numbers work, but ensuring that what works on paper works for people.

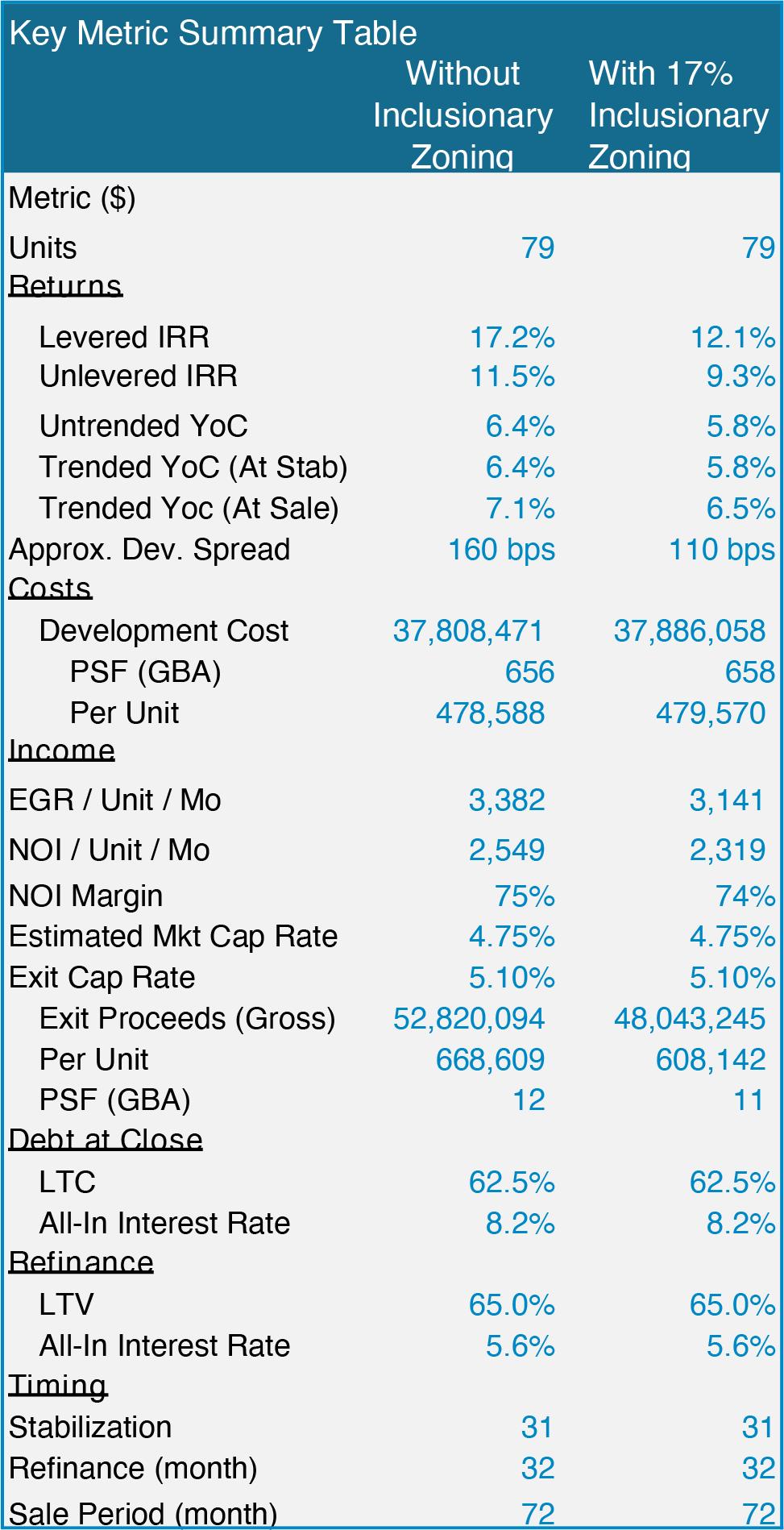

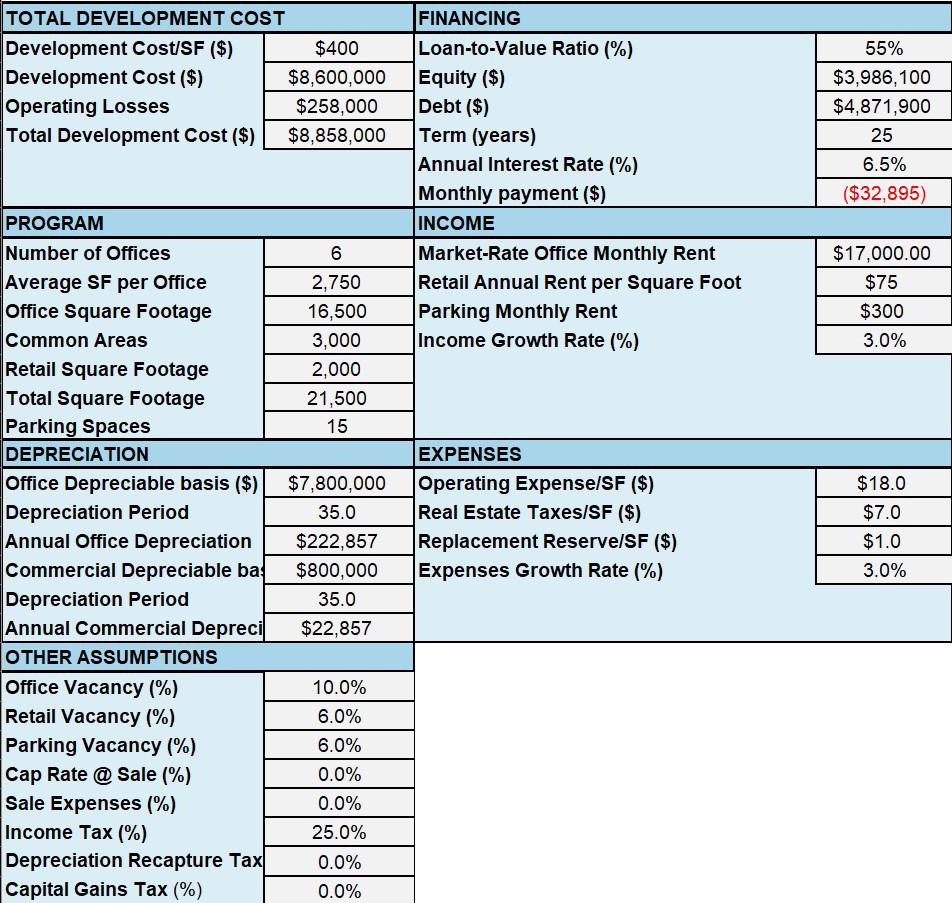

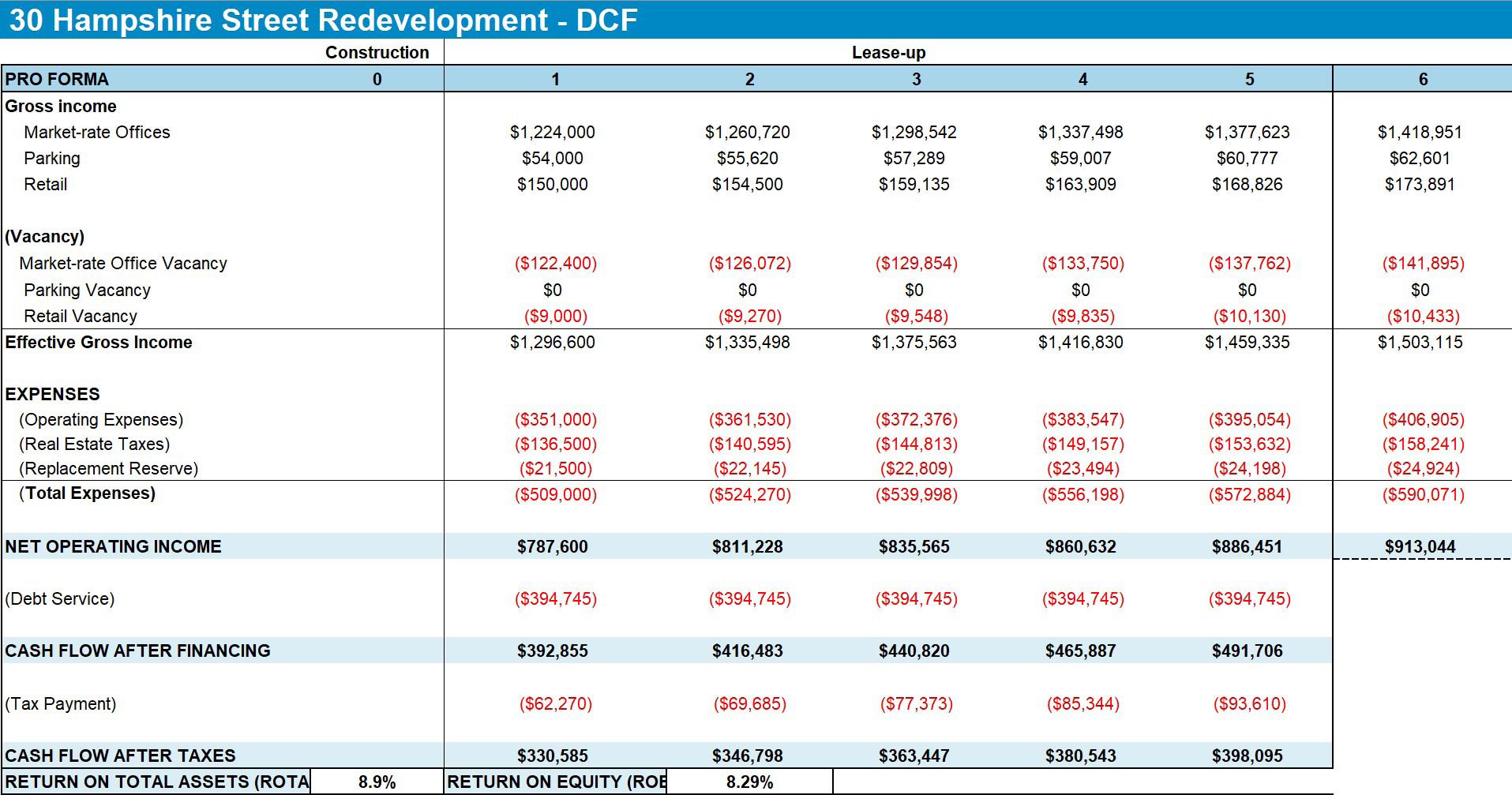

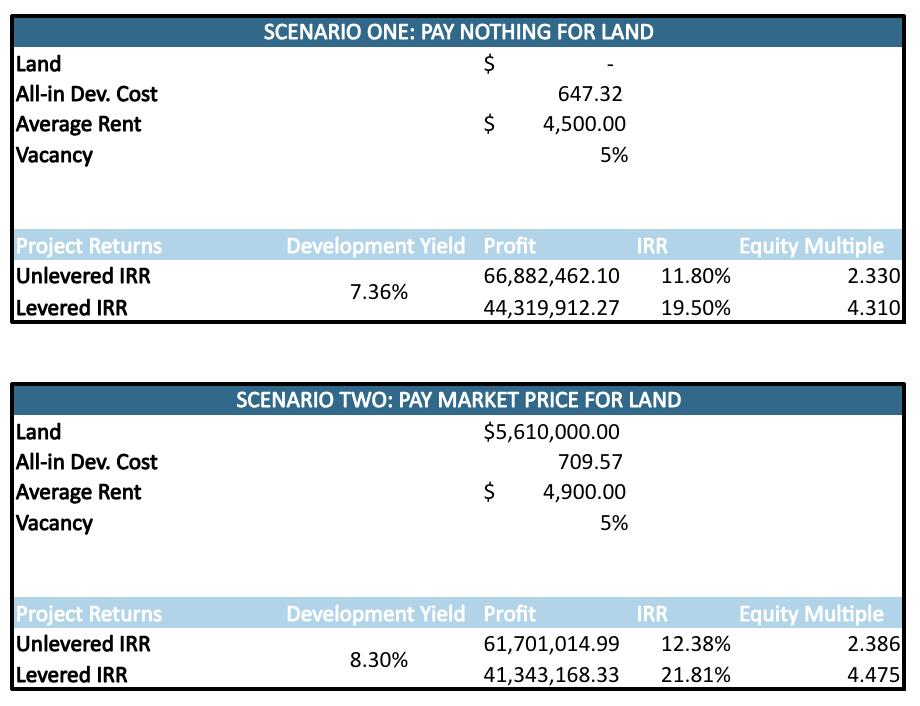

The Financials

The 73 Essex Street conversion illustrates both the opportunity and fragility of office-to-residential redevelopment in Boston. The proposed 79-unit program capitalizes on sustained multifamily demand, a favorable downtown location, and an unusually strong NOI margin enabled by the conversion program’s 29-year tax abatement.

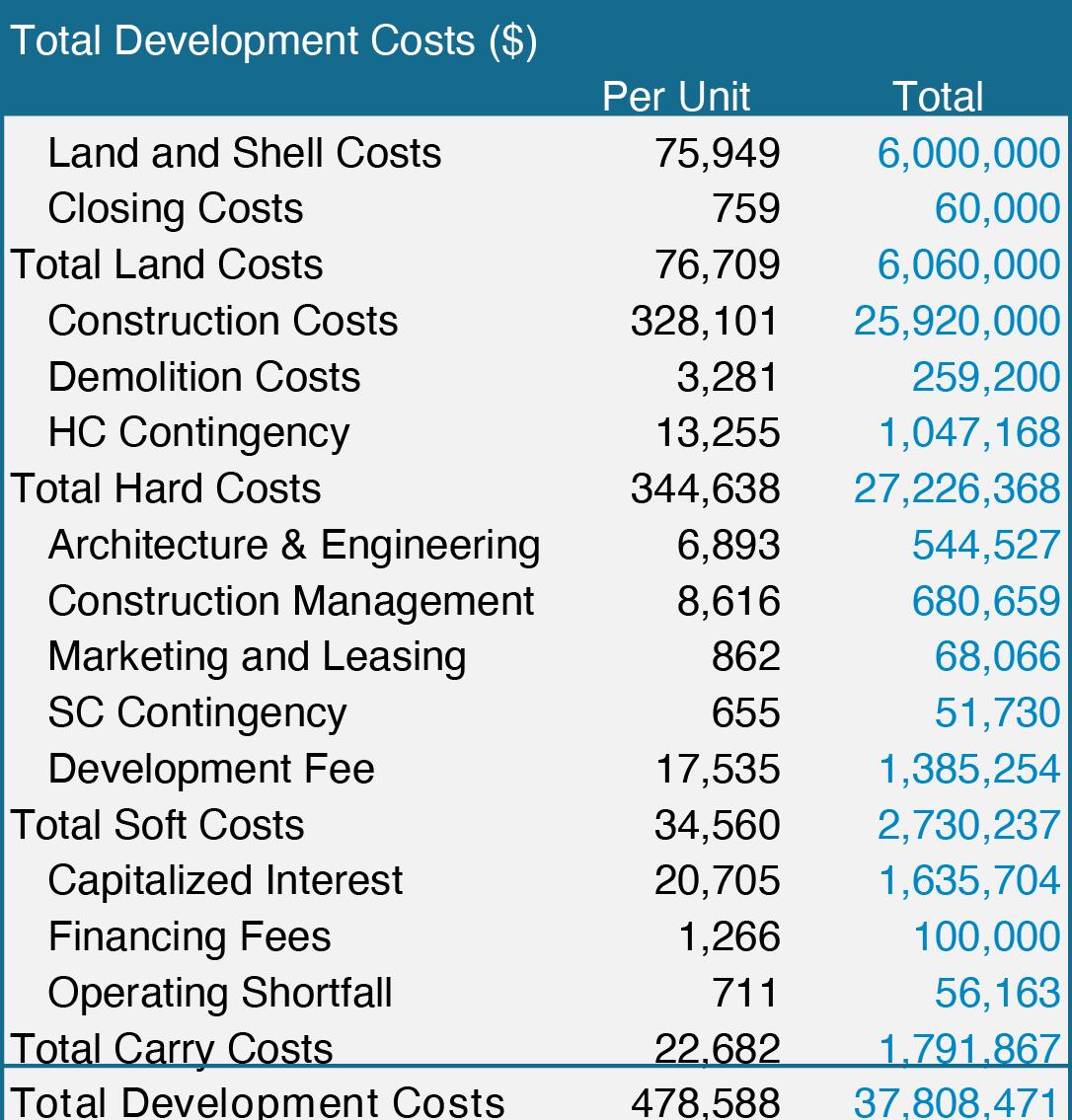

The Costs

The total conversion is expected to cost approximately 37.8 million dollars of which 72% is driven by hard costs. Including a 4% contingency budget for both soft and hard costs, a reserve for unanticipated demolition or trash removal (due to vacancy), market rate development fees and standard financing fees drive the economics.

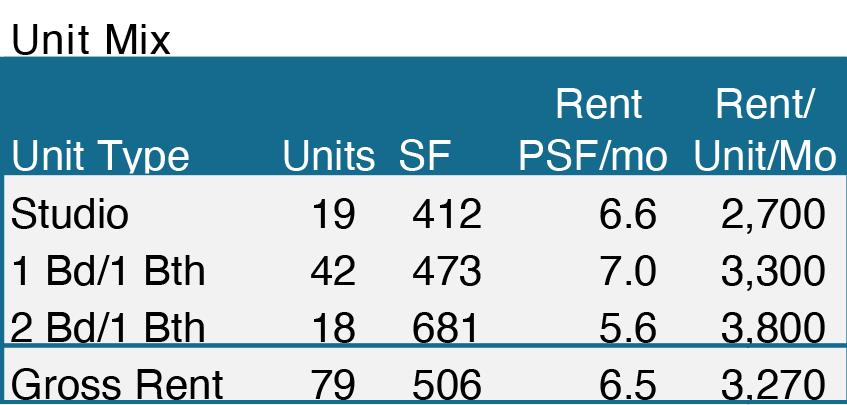

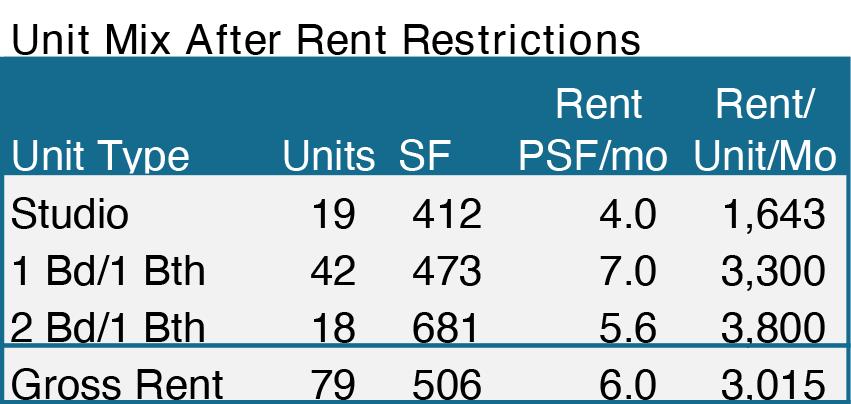

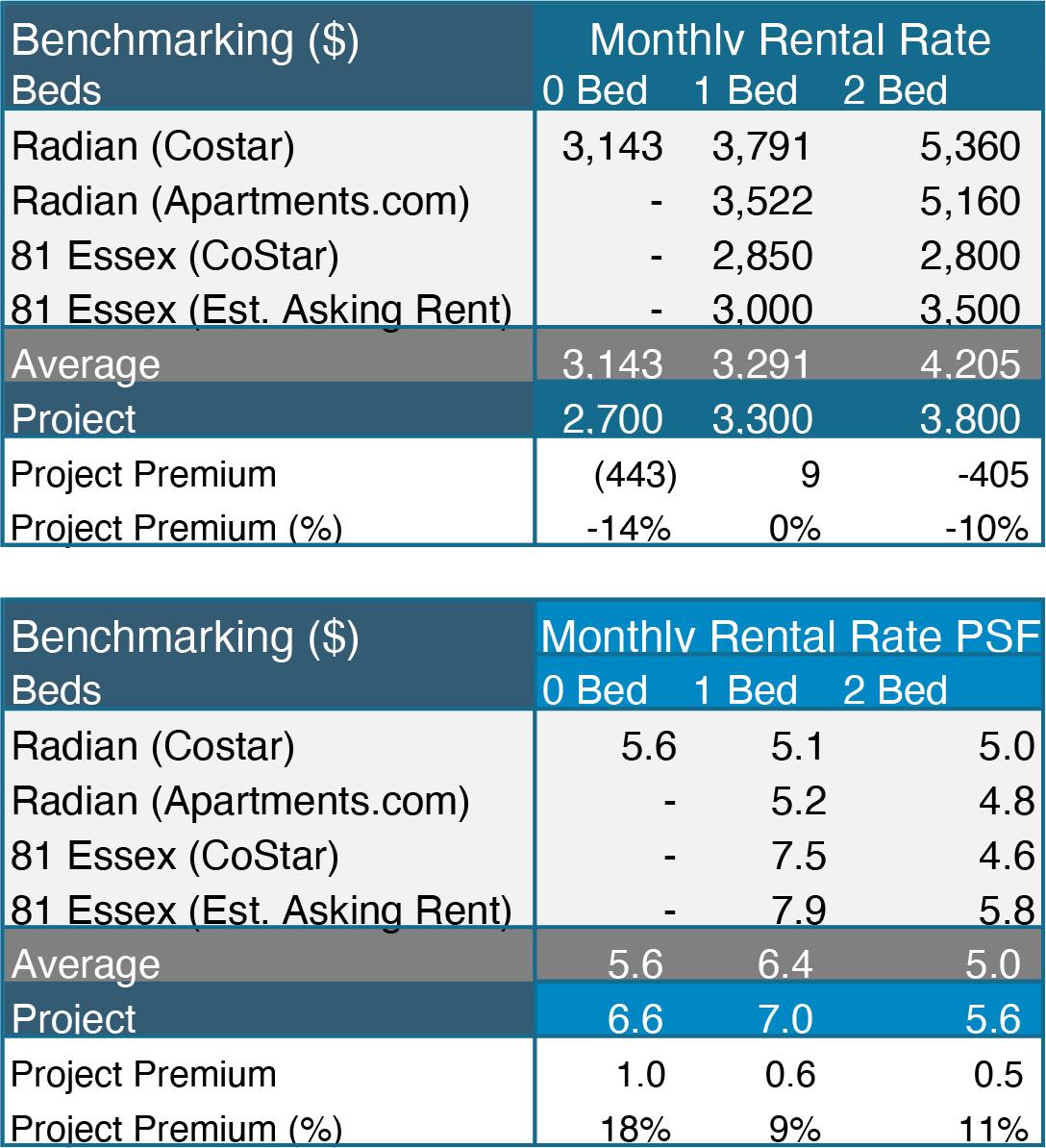

The Income

The unit mix was ultimately determined by the design optimization working in conjunction with the probabilistic rental rate. The project is expected to achieve average gross rental rates of 3,270 dollars per month per unit. After adjusting the income for inclusionary zoning, the average rental income falls to approximately 3,000 dollars per unit per month.

73 Essex is located proximally to two other multifamily assets, representing the spectrum in which the converted project would sit. Two projects, The Radian, and 81 Essex were utilized to benchmark the appropriate and likely rental rate for the asset in question. The underwritten rental rates are lower than the superiorly located and amenitized Radian and are at a premium to

The Expenses

The asset is expected to achieve a 75% stabilized NOI margin due to the reduced tax burden. This margin outperforms conventional multifamily assets by c. 10-20%.

The Challenge

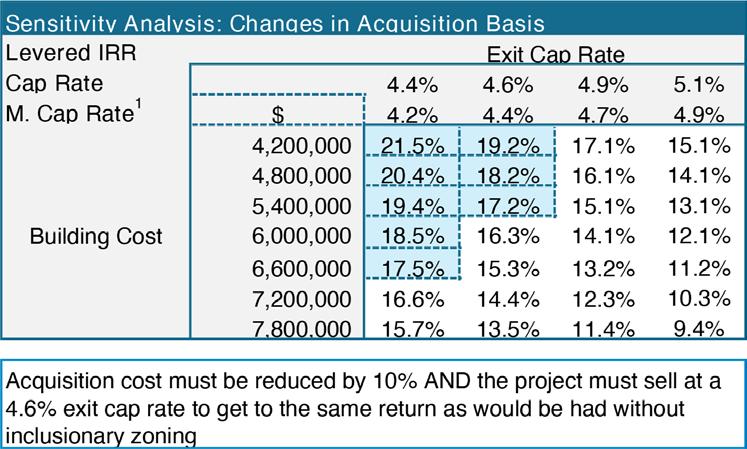

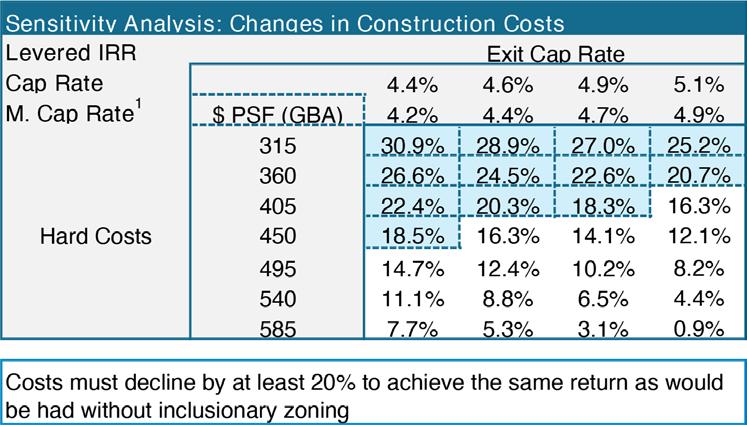

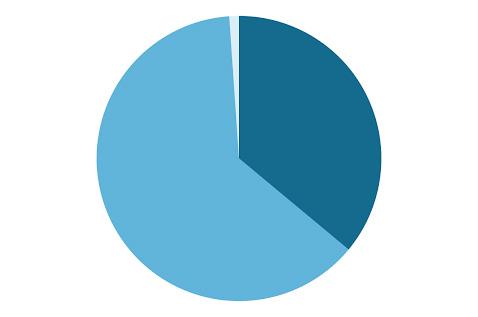

Financial feasibility is highly sensitive to policy. When inclusionary zoning (“IZ”) requirements require 17% of units at 60% AMI, NOI declines meaningfully, exit valuations compress, and return targets diminish. Without inclusionary zoning, the project is estimated to underwrite to a 17% IRR, and a 6.4% YoC, whereas with the inclusionary zoning restriction the project achieves a 12% gIRR and a 5.8% YoC. While the project still operates efficiently, IZ

redistribution erodes the development spread from approximately 160 bps to 110 bps which may now be insufficient to compensate for conversion risk, construction complexity, and exit uncertainty.

The Drivers

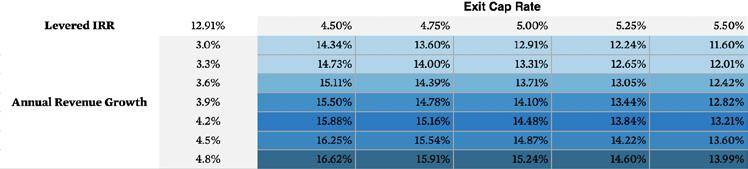

Determining the “right” exit cap rate is paramount. While tax abatements enhance near-term cash flow, it creates a valuation distortion for buyers. Underwriting must reflect the eventual normalized tax burden, appropriately adjusted for the remaining economic benefit associated with the abatement, leading to an upward adjustment in the exit cap rate of roughly 20 basis points after the hold period. Limited transaction history for conversions in Boston, investor caution regarding floor plate sizing, floor plan layout, and liquidity concerns may push cap rates for this product type beyond the estimated 20-bps adjustment outlined above. Sensitivity testing shows that restoring feasibility (achieving the same return outcome without inclusionary zoning) under IZ may require adjustments largely outside the developer’s control—significant cap rate compression, double-digit cost reductions, or sustained above-inflation rent growth. These conditions may materialize, but reliance on them constitutes heavily speculative underwriting and weakens competitive positioning.

Strategically, the underwriting demonstrates that office-to-residential conversion can be nearly viable under market-rate conditions but becomes economically strained when affordability mandates apply without additional subsidy. Given the inclusionary zoning requirement, base year rental rates would need to elevate by 9% to achieve the same return profile as the project achieves without inclusionary zoning. The gap is structural: IZ removes revenue without reducing costs or risk. Other subsidy programs such as 4% LIHTC and HUD financing can improve feasibility, but extend delivery timelines, increase carrying costs, impose compliance burdens, and have term limitations and funding caps that must be managed. These elements of additional subsidies fundamentally change the project profile.

Risks & Mitigants

The 73 Essex conversion carries a distinct set of risks, but many of them can be addressed through creative design and conservative underwriting. The first concern is physical: not every office building converts cleanly to housing, and deep floor plates and limited

natural light can create long, inefficient units that are hard to lease. In this case, test fits demonstrate that the existing structure can be divided into a functional mix of studios and one- and two-bedroom units with adequate light and circulation. Execution risk is another concern, since office-to-multifamily conversions are complex and can be prone to cost overruns and delays, particularly as this strategy is still new. The strategy here is to lean on lessons from comparable Boston conversions at 281 Franklin, 263 Summer, and 129 Portland, using their cost, schedule, and design outcomes as benchmarks to tighten contingencies and reduce the chance of unpleasant surprises.

There are also clear income-side risks. Groundfloor retail may prove difficult to lease in the current environment, which could leave the frontage inactive and put downward pressure on residential rents if the streetscape feels inactivated. To mitigate that, the underwriting treats retail economics conservatively, effectively targeting break-even on the commercial space and viewing it primarily as a tool to activate the block and support the residential program. Exit and capital-markets risk is another concern. The buyer pool for converted assets is still relatively shallow, and the eventual expiration of the tax abatement may push investors to demand wider cap rates. The pro forma responds by baking in a higher residual cap rate, including an explicit premium for the transient nature of the tax benefit. Finally, there is the basic question of rent risk: whether the projected rents are achievable in this corner of the downtown market. Here, comps at nearby assets such as the Radian and 81 Essex support the underwriting, and sensitivity analysis shows how returns behave under lower rent-growth assumptions.

Development Conclusion

Adaptive reuse offers an opportunity to transform underutilized office space into critically needed housing. Yet the underwriting makes clear that project feasibility depends on achieving alignment among revenue, cost, financing, and policy conditions. Even with critically efficient design, unit mix optimization, and cost mitigation, market-rate execution nearly achieves these requirements while inclusionary zoning does not (absent additional subsidy or arguably “aggressive” underwriting assumptions). As Boston explores office-to-residential conversion as a housing strategy, aligning affordability policies with financial reality will be essential to enabling more projects of this type. Is inclusionary zoning impeding the develop -

ment of these sites? It is possible to manipulate the pro-forma, the question remains, how far will developers be willing to push it?

Bibliography

1 Colliers. Greater Boston Multifamily Report, Q3 2025. Colliers, November 2025. Accessed December 7, 2025. https://www.colliers. com/download-article?itemId=4eef66ae3198-4de1-96e9-4794e97b05e1.

2 CoStar Group. (2025). Downtown Boston Multi-Family Submarket . CoStar Markets & Submarkets. https://product.costar.com/ market/search/detail/submarket/USA/ type/1/property/11/geography/6763/slice

3 OpenStreetMap contributors. (2025). Planet OSM Extracts / Map Tiles. Retrieved from https://download.geofabrik.de/

4 Radford, A., et al. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision (CLIP). OpenAI. https://openai.com/research/clip

5 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). TIGER/Line Shapefiles. Retrieved from https://www. census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/ time-series/geo/tiger-line-file.html

6 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table DP04: Selected Housing Characteristics. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov

7 Visual Capitalist. “Mapped: America’s Most (and Least) Affordable Cities in 2025.” Published November 23, 2025. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ americas-most-and-least-affordable-cit-

ies-in-2025/

8 Wolf, T., et al. (2020). Transformers: Stateof-the-Art Natural Language Processing. Proceedings of EMNLP. HuggingFace. https://huggingface.co/transformers

95 Berkeley: Office to Residential Conversion

Exploring the Development’s Opportunities, Incentives & Limitations

95 Berkeley: Office to Residential Conversion

Introduction

95 Berkeley is a historic 1920 masonry building located in Boston’s South End, recently renovated in 2020 with restored brickwork and newly installed windows. The structure offers efficient 16,000 SF floor plates, 34 parking spaces, and a strong urban presence within the protected South End Landmark District. Our vision is to transform 95 Berkeley into a vibrant multifamily community that brings new residents, creativity, and public life to the South End. Through adaptive reuse and contextual design, the project will deliver modern homes for young professionals and families, activate the ground floor with retail and cultural uses, and introduce publicly accessible creative spaces where artists can live, work, and engage with the neighborhood. The property is eligible for Federal and Massachusetts Historic Tax Credits, the BPDA’s Residential Conversion Pilot Program, and new state-funded initiatives supporting office-tohousing conversions, all of which strengthen its suitability for redevelopment. This analysis evaluates two potential pathways—(1) converting the existing structure and (2) adding density through vertical expansion—while examining how incentives, zoning, and regulatory frameworks shape project feasibility and financial performance.

The South End & 95 Berkeley

The South End was laid out in the mid1800s with uniform Victorian brick rowhouses and park squares for Boston’s elites. As railroads and industry began to infiltrate the neighbourhood in the late 1800s, wealthy residents gradually moved to the newly developed Back Bay, with the 1872 great fire and the 1873 financial panic serving as catalysts. Jewish, Italian and AfricanAmerican immigrant households, working in local factories or along the docks and railroads, took their place and oftentimes subdivided the homes into tenements or lodging houses (Trust for Architectural Easements, 2025) (Global Boston, 2015). After World War I, Syrian, Greek and Armenian immigrants moved into the area. After World War II, the South End was impacted by suburbanization and began to decline, suffering from population declines, underinvestment and structural deterioration. In the 1960s and 1970s, the South End was identified as an urban renewal area and the city presided over significant demolition and re-development activity

that displaced many families. Despite activist movements, development and gentrification has continued and driven out many low-income and immigrant families.

95 Berkeley was built in 1920, during a time of significant industrialization in the South End, and boasted a cast-in-place and poured concrete structure, high ceiling heights and large windows. It was used as office space for a long time and was renovated in 1988 (Nerej, 2016). In 2016, CIM Group purchased the building from the Community Builders for $48M (Costar, 2016) and renovated the building in 2020 (Costar, 2025), attempting to reposition it as premium “brick-and-beam” office space. However, the post-COVID collapse in office demand (WBUR, 2024) hampered CIM’s leasing efforts and the building’s occupancy languished at 12% (Costar, 2025). In 2025, CIM sold the site to Aden Capital for $24M and the new owner plans to convert the building into a 92-unit residential development with 1,700 SF of 1st floor office space. Aden’s strategy embodies Boston’s broader pivot: transforming stranded office assets into new housing in one of the city’s most historic neighborhoods.

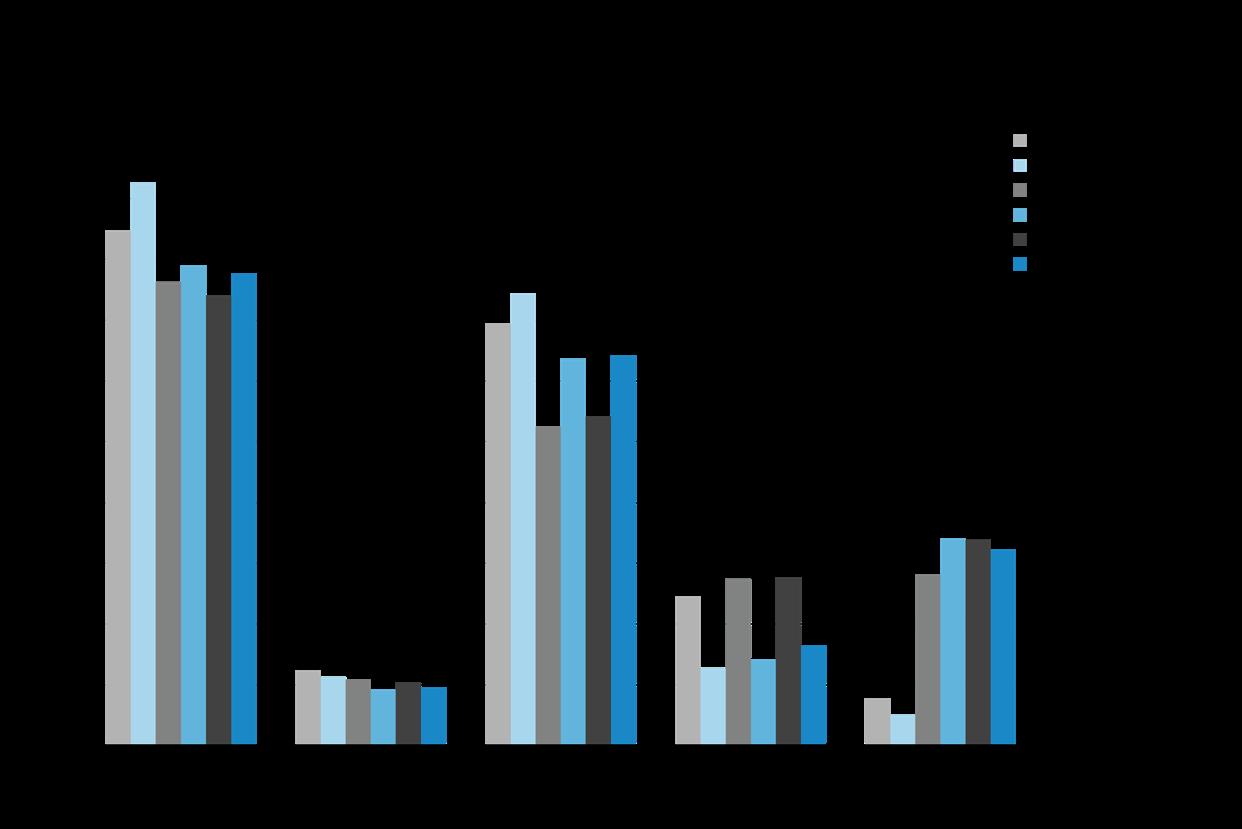

The Demographics

The South End’s current demographics reinforce why 95 Berkeley is a strong candidate for an officetoresidential conversion. The neighborhood houses a wealthier, higher educated and more white-collar demographic than Boston overall, with a renterheavy housing stock and

a large share of adults in prime working ages. Together, these patterns point to deep demand for welllocated, transitaccessible apartments of the type the building and site can deliver.

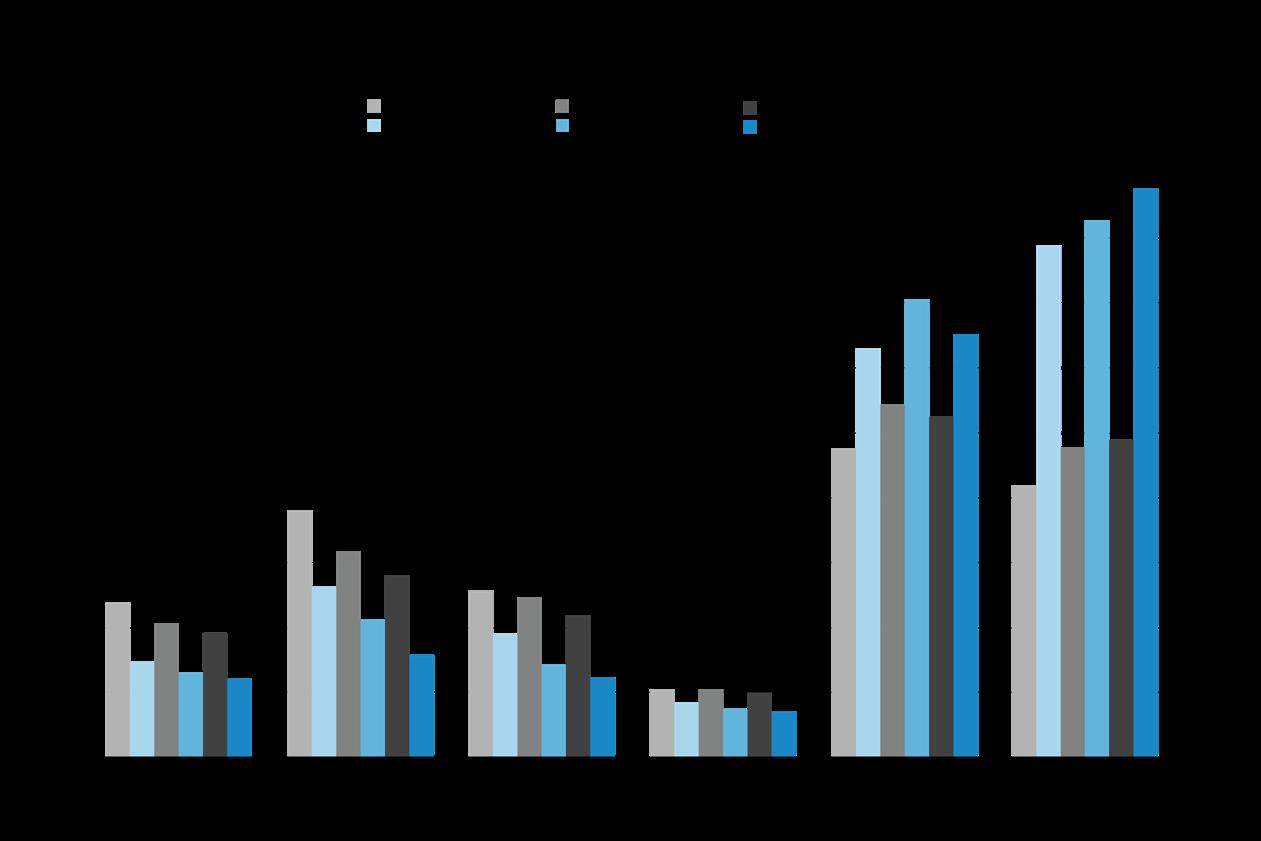

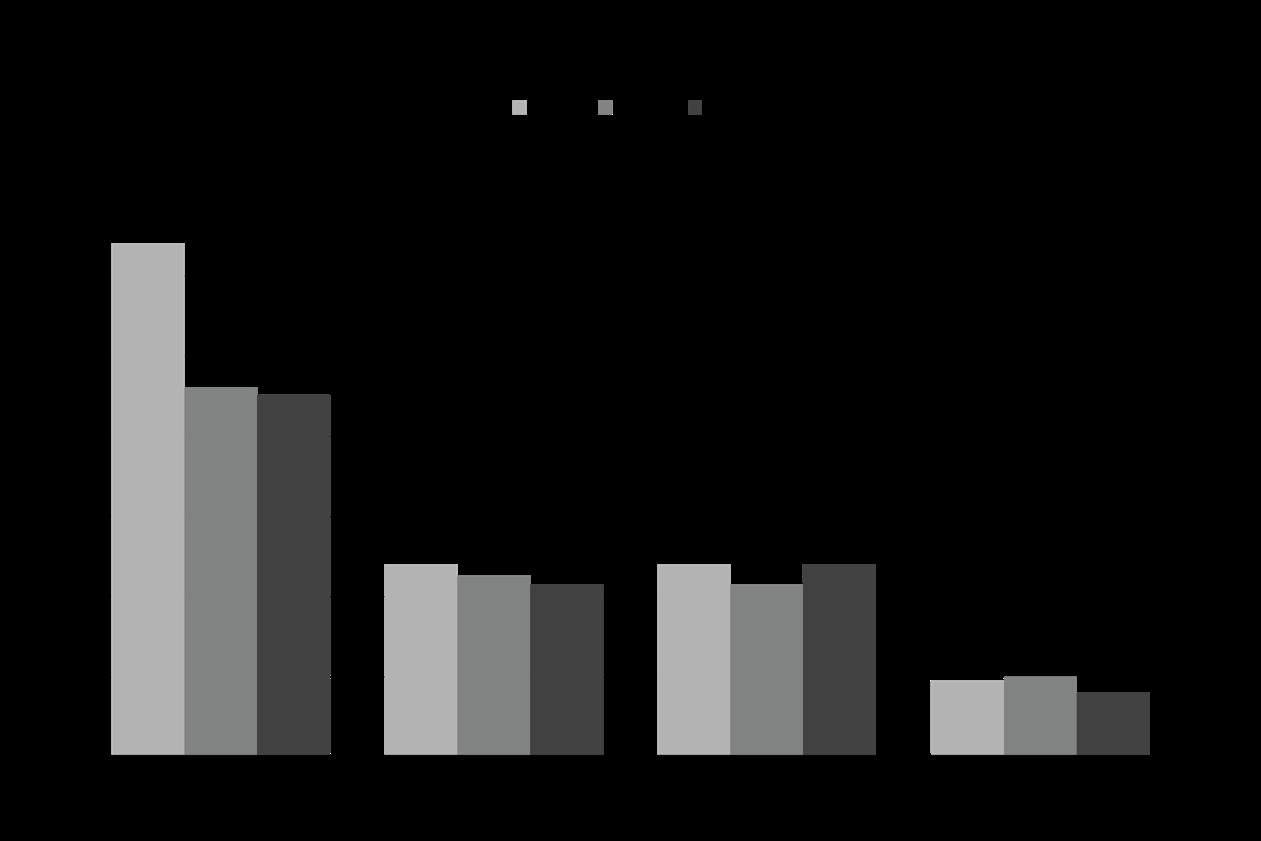

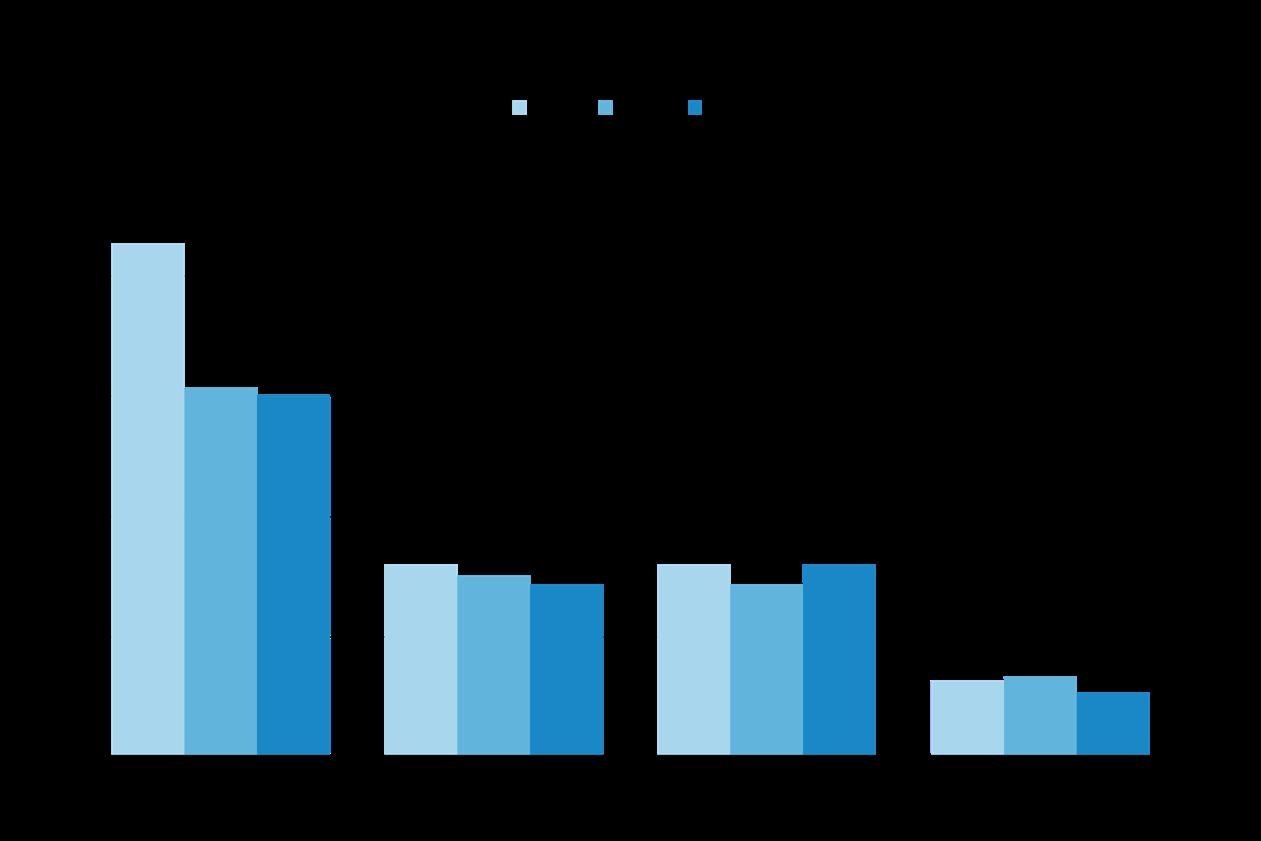

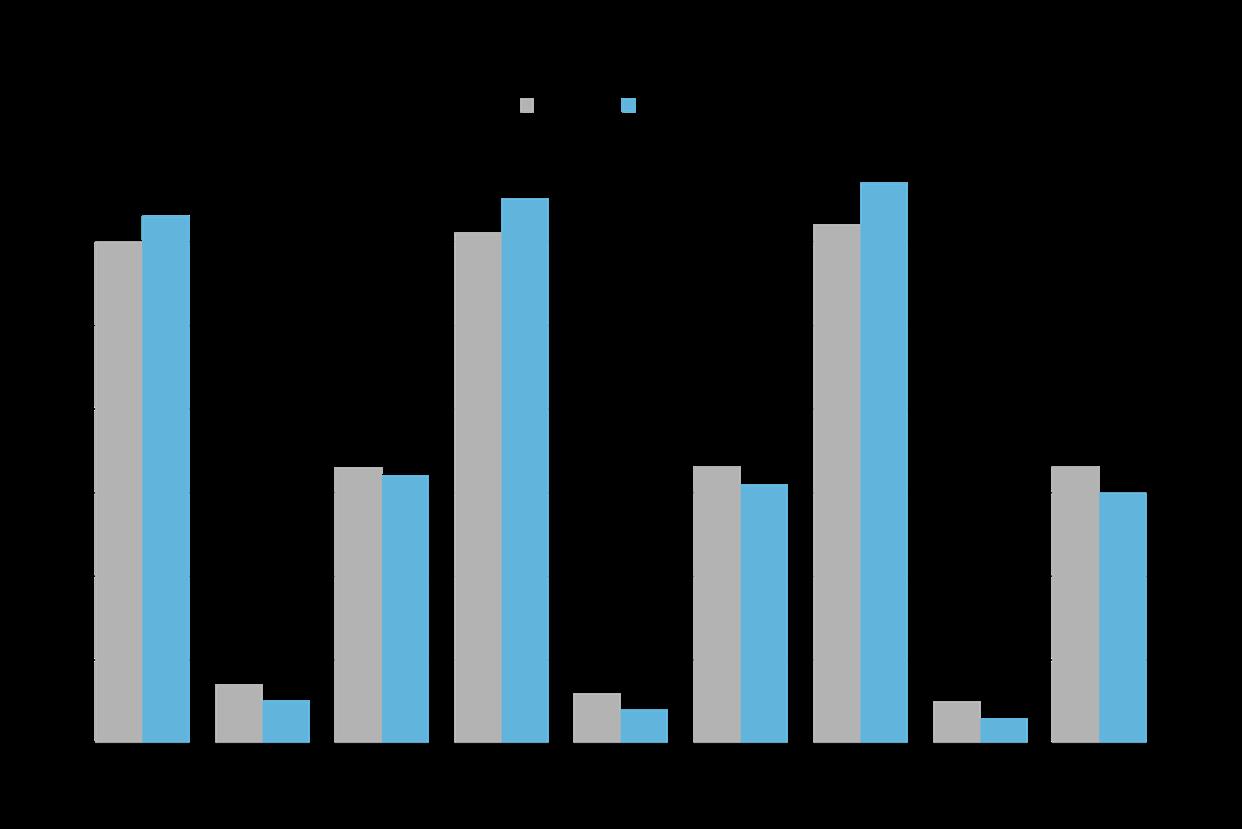

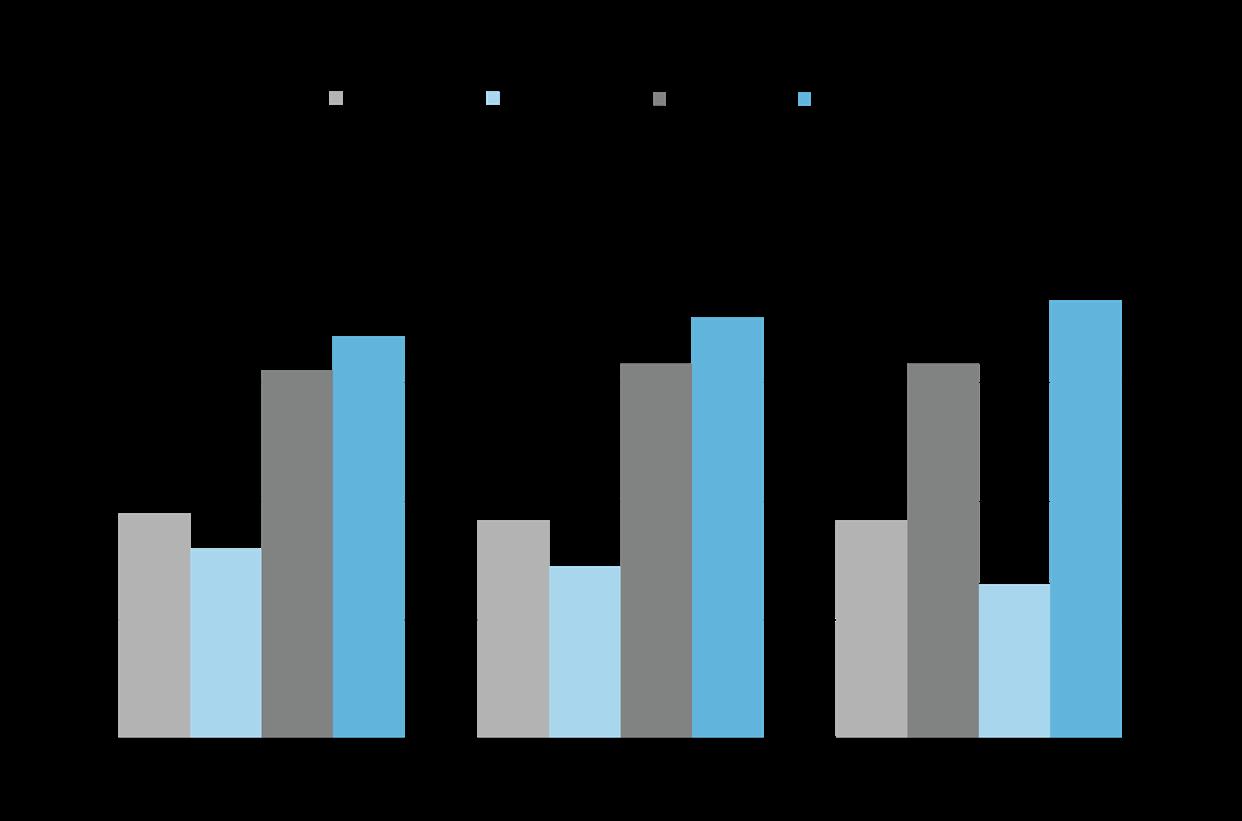

Exhibit 10 (median household income) and Exhibit 12 (housing occupancy) show that the South End has a higher renter share and sub-

stantially higher median household income than the city. This gap has grown between 2010, 2020, and 2023 as neighborhood median household income pushes toward $200K. Resultantly, it can be expected that rents in the South End are higher than Boston as a whole.

Exhibit 3 (education levels) and Exhibit 9 (occupation) reinforce the median income story: the South End has a larger share of residents with bachelor’s and graduate degrees and a higher proportion in whitecollar jobs, with bluecollar and service work shrinking over time.

Exhibit 2 (age distribution), Exhibit 6 (marital status), and Exhibit 8 (employment status) all point toward smaller, highearning renter

households who value flexibility and proximity over space. The South End has a concentrated age bracket of 25–44, with more single residents, higher employment and higher “workfromhome” rates than Boston overall, especially after 2020. This supports demand for flexible 1-bed, 1-bed+den, 2-bed and 2-bed+den typologies.

Finally, Exhibit 5 (migration patterns) suggests there is a continuous and manageable inflow of newcomers, indicating long-term tenancy and a neighborhood that values community.

Enrique, Jerry Zhang

Philip Smith, Costantino

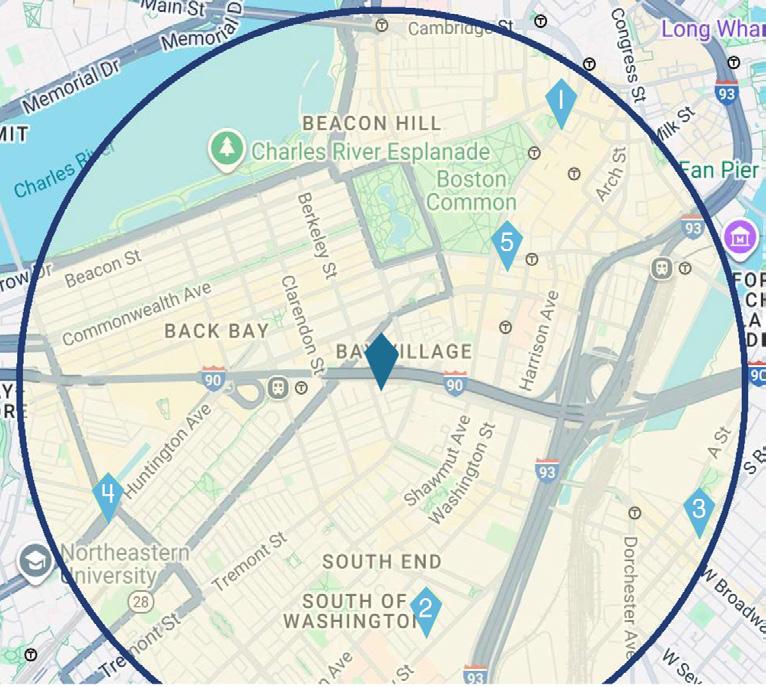

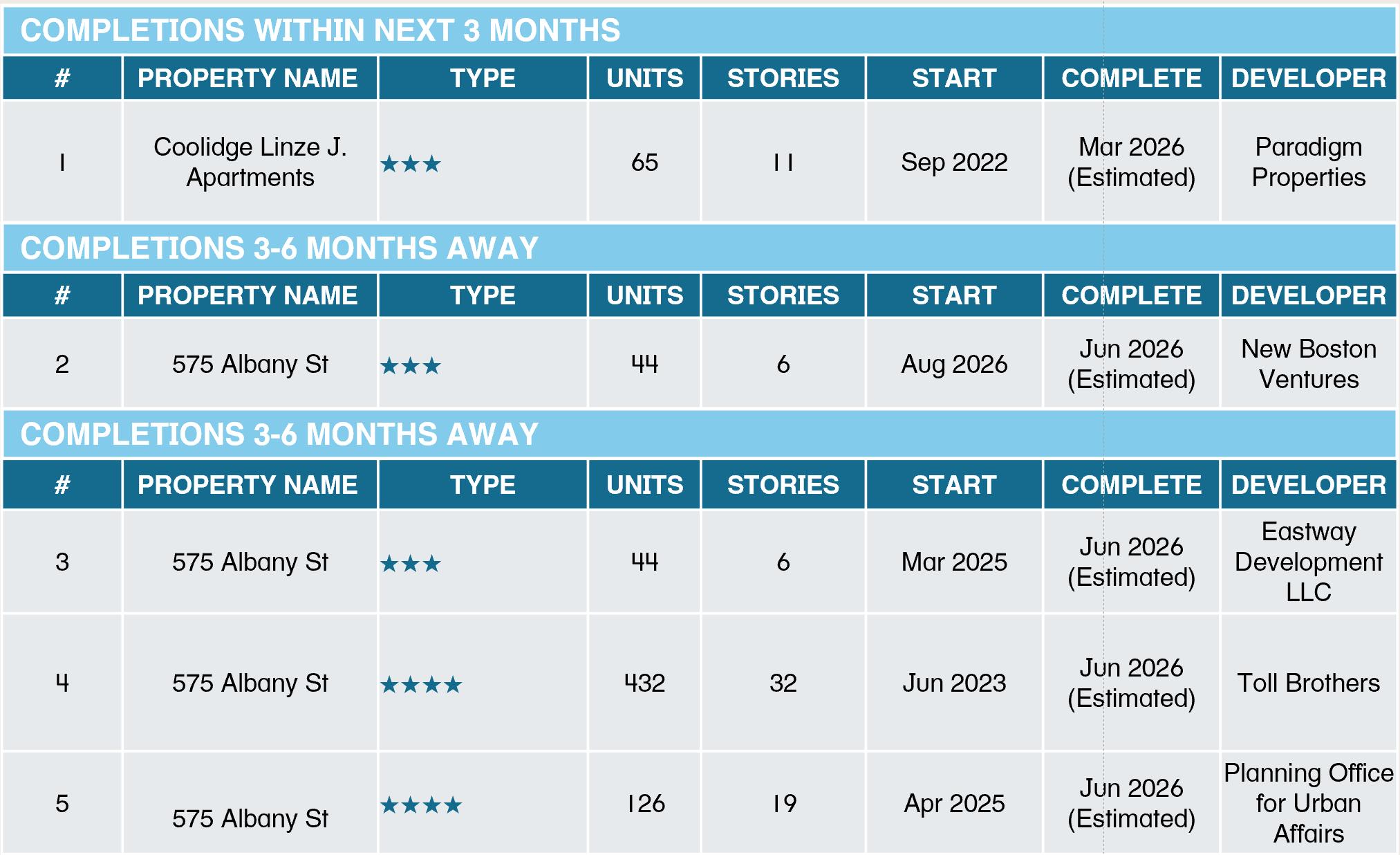

Market Analysis

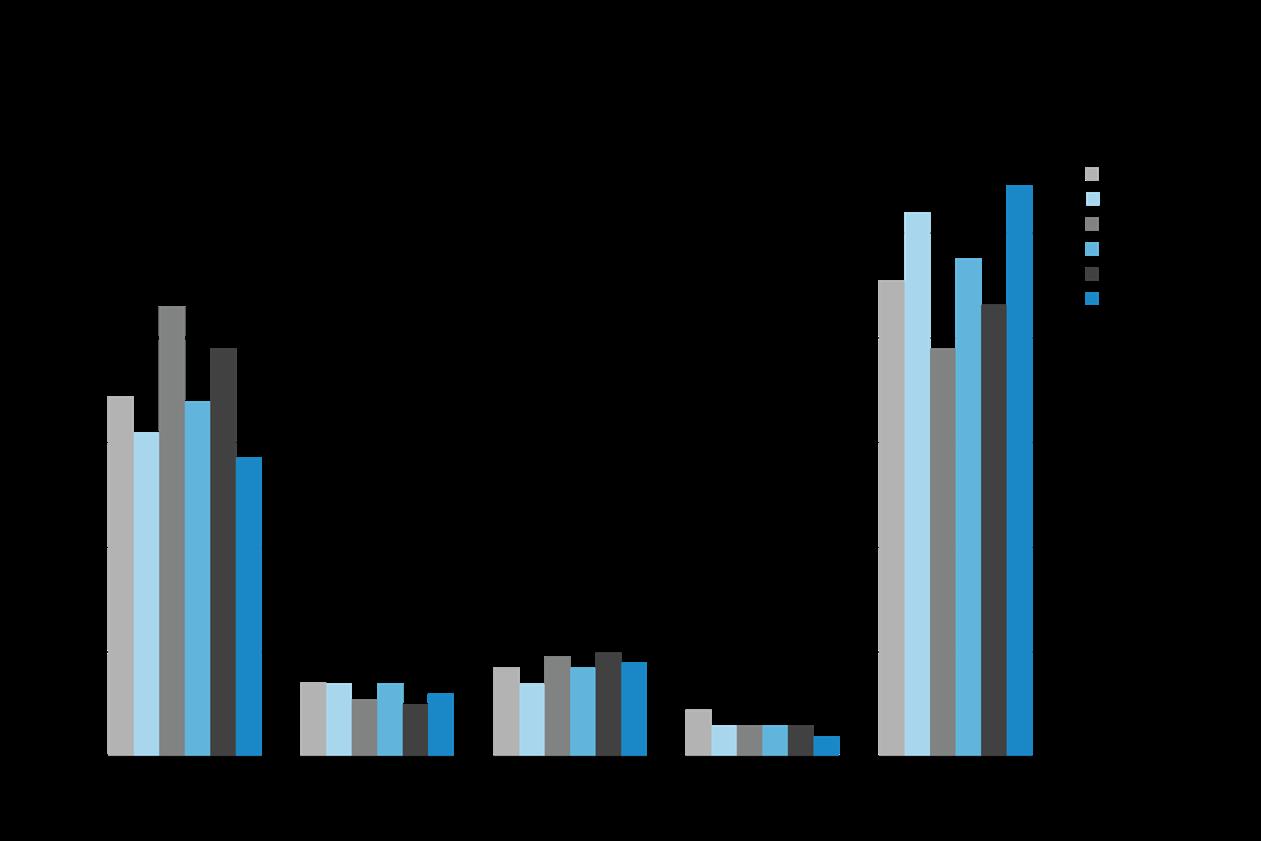

The pricing of recent sales in the surrounding area and a limited new-construction pipeline, as can be seen in Exhibits 13 and 15, reinforce that South End is one of Boston’s strongest multifamily submarkets. Institutional assets in Back Bay, Bay Village, and the South End are trading at high per-unit values and achieving top-ofmarket rents, driven by consistent demand for well-located buildings close to transit, jobs, retail, and daily-life convenience. Any new supply will likely be absorbed without softening market rents or having a material impact on the demand profile of the area.

South End’s demographics show why the area is such a strong submarket: the neighborhood is wealthier, more educated, and more white- collar than Boston overall, with a large, renter-heavy population in prime working ages and a growing work-from-home population that values high- quality space and building amenities. Together, these market and demographic conditions position 95 Berkeley to capture a deep pool of high- earning renter households and support high rents, as can be seen in Exhibit 14. Rents at comparable properties built after 2014 average $4,193 per month ($5.84 PSF).

Recent pricing of stabilized assets is $675,000 per unit on average. However, all-in development pricing in the Boston market is $750,000 per unit

for wood product up to 70 feet and $0.9-1.1M for high-rise product (Oxford Properties, 2025). When market pricing is below replacement cost, investors typically prefer to buy, not build. Aden Capital’s purchase indicates significant confidence in the project’s prospects.

Exhibit 17: Comparables (CoStar Group, 2025)

18: Recent Sales (CoStar Group, 2025)

Berkeley Comparables

Regulations & Incentives

Zoning Regulations

95 Berkeley is in the South End Neighborhood Zoning District’s Community Commercial Zoning District. governed by Article 64 of the Boston Zoning Code. A variety of different uses are allowed, including multi-family dwellings (95 Berkeley OTR, LLC et al., 2025). There are no minimum lot size requirement or lot area minimum for additional dwelling units. The allowable floor area ratio is 4.0 and the maximum height is 70 feet. In addition, while there are no front or side yard requirements, there is a rear yard requirement of 20 feet and an open space requirement of 200 square feet per residential unit. The conversion of the existing conforms to all of the above regulations with the exception of the open space requirement, for which a variance would need to be sought.

Four zoning overlays are applicable to the site: (1) Groundwater Conservation Overlay District (GCOD); (2) Restricted Parking District; (3) Restricted Roof District: South End; and (4) Coastal Flood Resilience Overlay District (CFROD). GCOD is intended to preserve water levels in Boston, and a conditional permit will need to be obtained from the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA). Provisions under the Restricted Parking District are not triggered in relation to the conversion. The Restricted Roof District restricts the alteration of any roofs and also requires a conditional permit from the ZBA if triggered. The CFROD seeks to protect structures from rising sea levels and encourages certain design solutions in this regard that need to be pursued (95 Berkeley OTR, LLC et al., 2025).

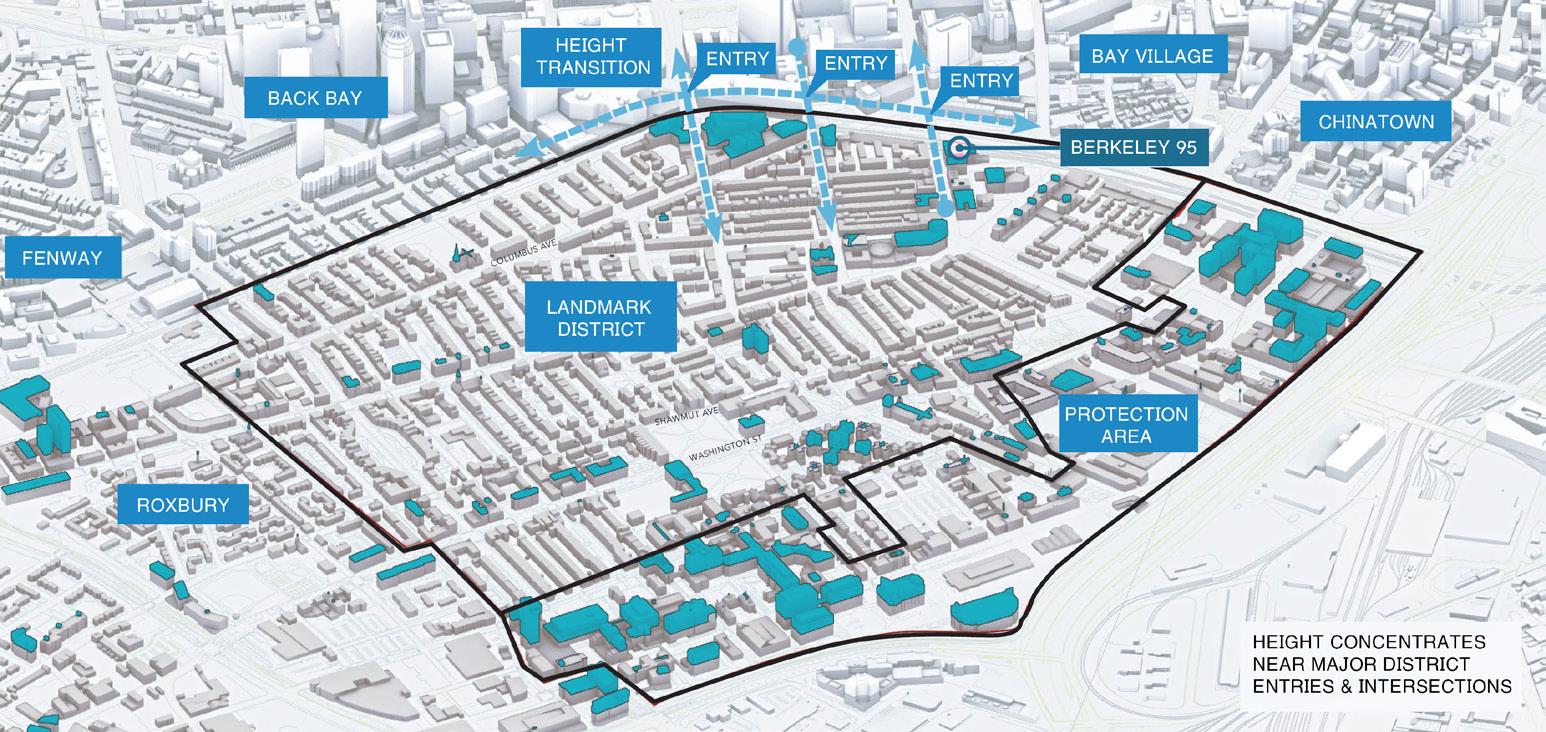

Most importantly, the site is located within the South End Landmark District and the South End District as listed in the state and national registers. All proposed exterior work is subject to the review and approval of the South End Landmark District Commission (SELDC). Any height addition would be subject to lengthy review processes and potential outright rejection. See Exhibit 16 for a contextual map, showing 95 Berkeley, height additions in the landmark district, and the height transition between the South End and Back Bay, Bay Village, and Chinatown areas to the north.

Finally, given that the site is in the City of Boston, any multifamily development is subject to the Inclusionary Development Policy (IDP), which requires 20% of units to be affordable for up to 50 years.

Government Incentives

The project is eligible for multiple incentives from the local, state and federal governments in support of an office-to-residential conversion.

Firstly, the Boston Planning & Development Authority (BPDA) recently announced an extension to its Downtown Residential Conversion Incentive Pilot Program. The program offers as-of-right conversions, a property tax abatement of up to 75% for 29 years, and a streamlined approval process for Article 80 review. In support, the state of Massachusetts will provide up to $215K per affordable unit with a cap of $4M per project (Boston Planning & Development Agency, 2025).

As part of the Affordable Homes Act (AHA), the state has a separate Commercial Conversion Tax Credit Initiative (CCTCI) and will award up to 10% of a qualified project’s development costs (practically $2.5-3.0M per project) (Boston Planning & Development Agency, 2025).

95 Berkeley, as a contributing historic building to the South End Landmark District, is a highly likely candidate for the Massachusetts Historical Rehabilitation Tax Credit and the Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentive program, each of which provide up to 20% of the cost of certified rehabilitation expenditures. The building has to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places and while 95 Berkeley itself is not listed, the project would likely be approved by the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

Lastly, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) guarantees FHA 221(d)(4) loans for multifamily rehabilitation projects. These loans come with high leverage (up to 90% loan-to-cost), low and fixed rates, lengthy amortization periods (up to 40 years) and are non-recourse, with a 3-year interest-only period during construction. They are also assumable, helping with valuation and liquidity at disposition. That said, they have lengthy funding timelines and are costly to originate.

Project Proposal

The Site

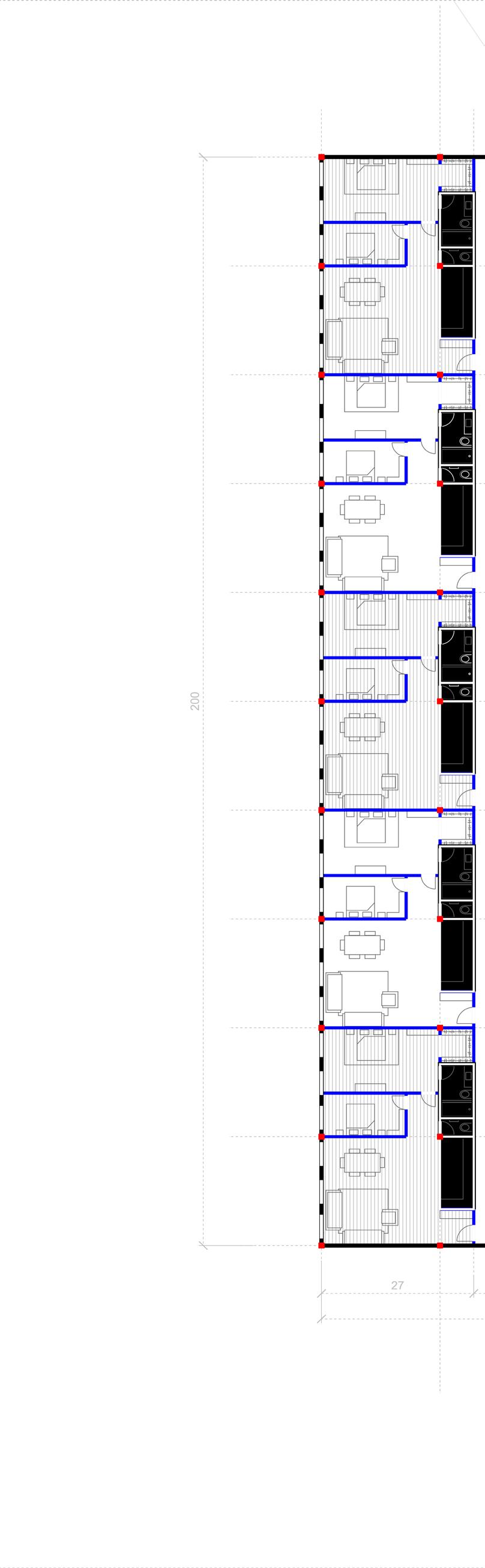

On the existing site, the first floor consists of a mix of office and retail. Mass Design Group, an architecture firm in Boston, occupies the east corner of the building. There are 5 floors of offices above and an underground car park. The existing building has a concrete structure with a column grid in the interior and a structural masonry facade. There are two elevator cores in the center of the building and two fire stairs on either side of the building.

To convert the office building into apartments, the hallway connects between the elevator cores and fire stairs in a double loaded corridor set

addition of a bike room. There are 36 parking spots.

In shaping the ground-floor strategy for 95 Berkeley, the design team drew direct inspiration from The Ray Philly, a residential project celebrated for integrating artist studios, maker spaces, and publicly accessible creative programming into a residential. The Ray apartments, where living, making, and exhibiting coexist, offered a compelling precedent for how culture-driven ground floors can support both residents and the surrounding neighborhood. Our team thought this would be the best use of the first floor. It reinforces the South End’s identity as a neighborhood where creativity and everyday life intersect, echoing both its historic mixed-use character and its contemporary arts ecosystem.

Precedent Reaserch

As part of our research into adaptive reuse and residential conversions, our team spoke with Ellen Anselone, Principal and Vice President at Finegold Alexander Architects. Ellen has led some of Boston’s most significant and complex adaptive reuse projects, several of which directly informed the direction of our proposal for 95 Berkeley. Her experience offered valuable guidance on both the architectural and regulatory challenges associated with converting historic structures into contemporary multifamily housing. She was also the project and development lead on some of the projects we took inspiration from, which includes Resident at Penny Saving Bank, The Lucas at 135 Shawmut St, and 226 Causeway Street.

Residences at Penny Savings Bank: A transformative redevelopment of a historic bank building that combines restored masonry with carefully integrated new construction. The project demonstrated how bold architectural interventions can coexist with preservation requirements, particularly when adding new windows, creating a rooftop addition, or repositioning internal cores.

The Lucas at 135 Shawmut Avenue: A benchmark adaptive reuse project in the South End involved inserting a completely new residential structure within the preserved shell of a historic church. The Lucas taught us about the technical and community challenges of adapting heritage buildings, and how contemporary design can complement, not imitate, the historic fabric.

226 Causeway Street: A mixed-use redevelopment that balances commercial, residential, and public-facing functions while navigating complex zoning overlays. We were particularly interested in 226 Causeway Street because it is most similar to our project. The project used to be a biscuit manufacturing plant, and then it was converted into a mixed office, retail, and residential. Also similiarly, the structure in 226 Cuseway was also in very good condition, additional floors of residential could be added directly on top using a steel structure.

Ellen emphasized that successful adaptive reuse projects require a disciplined balance between preservation constraints and architectural innovation. Given the building’s location within the South End Landmark District, Ellen stressed the importance of early and thorough dialogue with the South End Landmark District Commission (SELDC). Her experience illuminated the key principles SELDC prioritizes: façade preservation, window rhythm, material specificity, and sensitivity to massing. Her advice helped shape our strategy for designing an addition that is contemporary yet deferential. Her perspective, grounded in decades of adaptive reuse experience across Boston, helped validate our assumptions and sharpen our design direction.

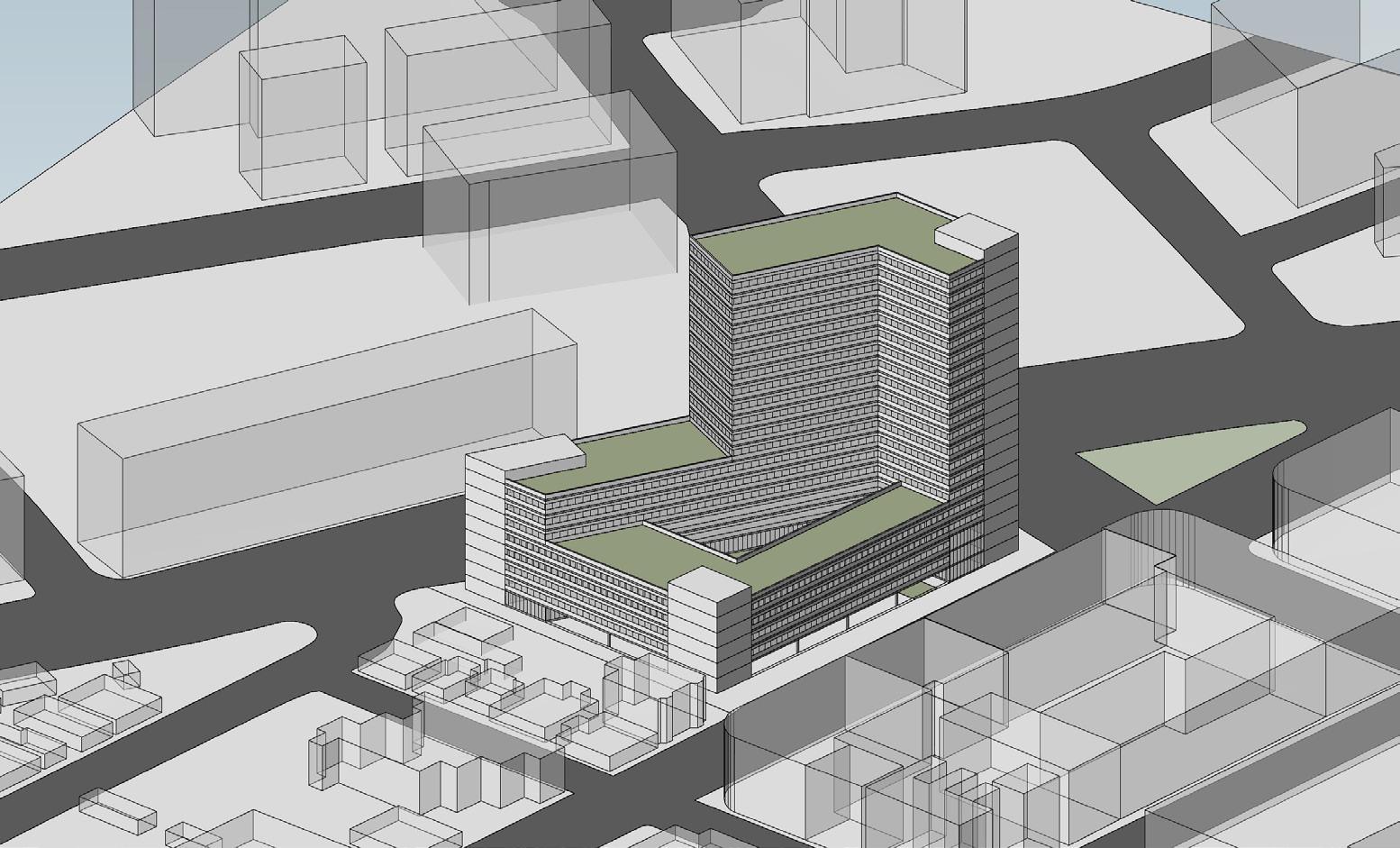

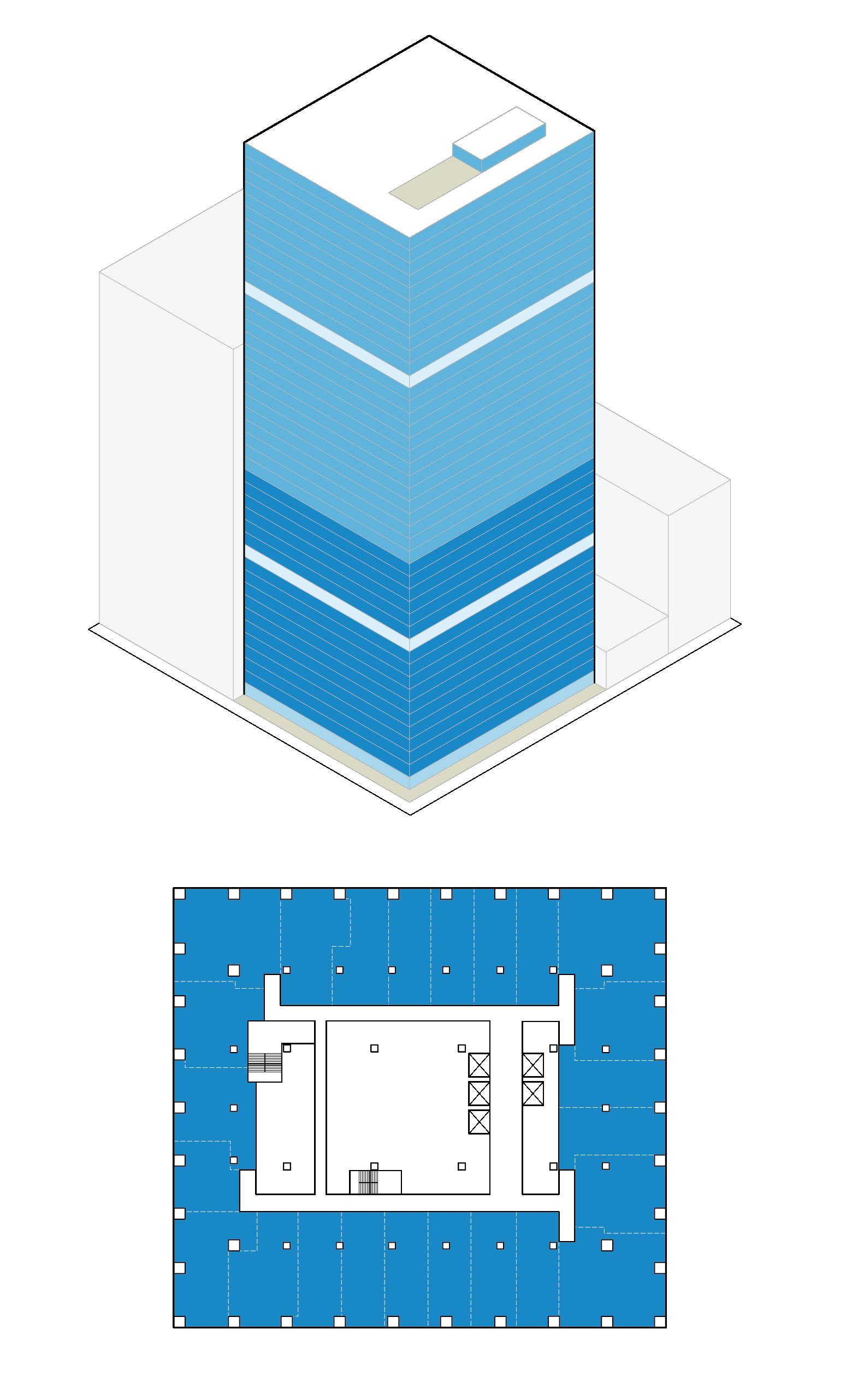

Our Design

Our team also experimented with implementing a steel 5 story addition on the top of the building. Most historic buildings, including 95 Berkeley, were constructed with robust masonry and concrete systems capable of carrying additional loads. Adding new floors allows the team to leverage this structural inheritance rather than replicating it in new construction. Our early demographic research helped inform our unit mix of most 1 bed, 1 bed + den, and 2 bed units.

Our proposal for 95 Berkeley introduces five new residential floors atop the existing historic structure. The design strategy is rooted in three core principles: structural compatibility, architectural continuity, and respectful differentiation. By using a lightweight steel structural system, aligning our structural grid with the existing building, and developing a façade that responds to the original masonry rhythms, the addition becomes a natural extension of the building while maintaining a clear old-and-new dialogue. The top addition is subtly set back from the original parapet, reducing visual impact from the street and reinforcing the reading of the historic building as the primary object.

As part of the five-story vertical addition, our team introduced a sky lounge and outdoor balcony terrace—a new amenity layer that elevates the building’s residential experience while strengthening its relationship to the South End’s urban landscape. The sky lounge functions as a communal living room for the entire building. Positioned on the lowermost level of the addition, it offers panoramic views toward Back Bay, the South End brownstone district, and the broader Boston skyline.

Financial Analysis

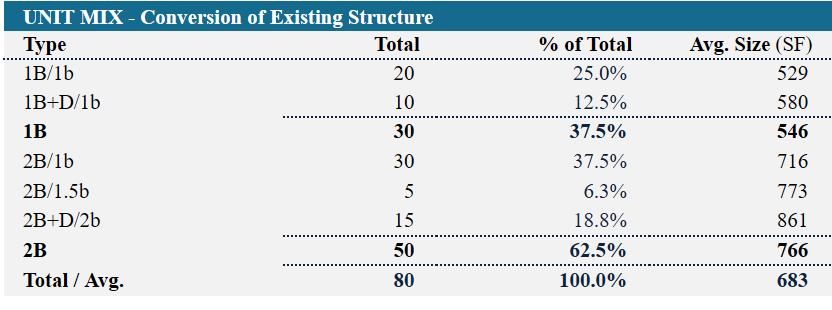

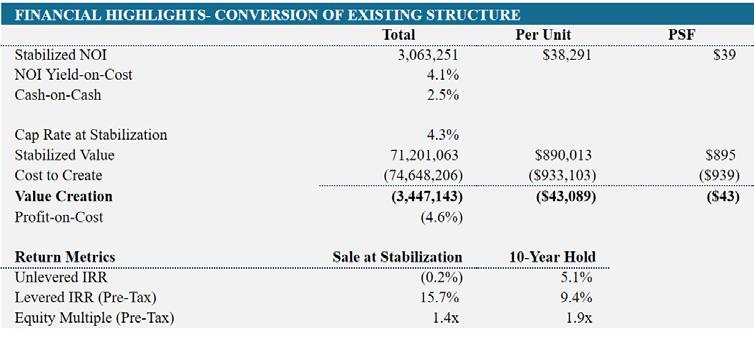

Conversion of Existing Structure

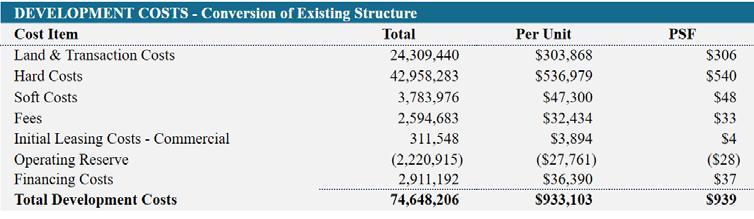

To determine the financial feasibility of converting the existing structure, assumptions were made in regard to timing total development cost, rent, operating model, valuation, and financing.

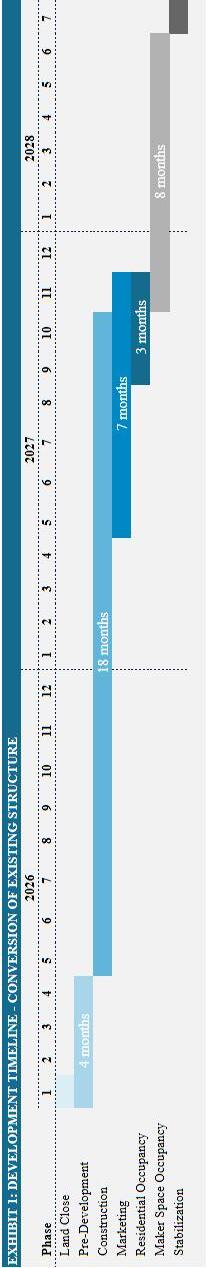

The duration of the conversion is as good as it gets in Boston, as the site has received BPDA approval in November 2025 and is expected to clear approvals in January 2026. Overall, the project will take 2.5 years from land closing, January 2026, and stabilization, anticipated for July 2028. A 4-month pre-development period is assumed prior to construction start in May 2026. The conversion works are expected to take 18 months. Lease-up of the residential units is anticipated to begin in Sept. 2027, 2 months before certificate of occupancy, and take 3 months. Maker spaces are anticipated to lease-up upon certification of substantial completion, Nov. 2027, and is anticipated to take 8 months. (See Appendix A For Timeline)

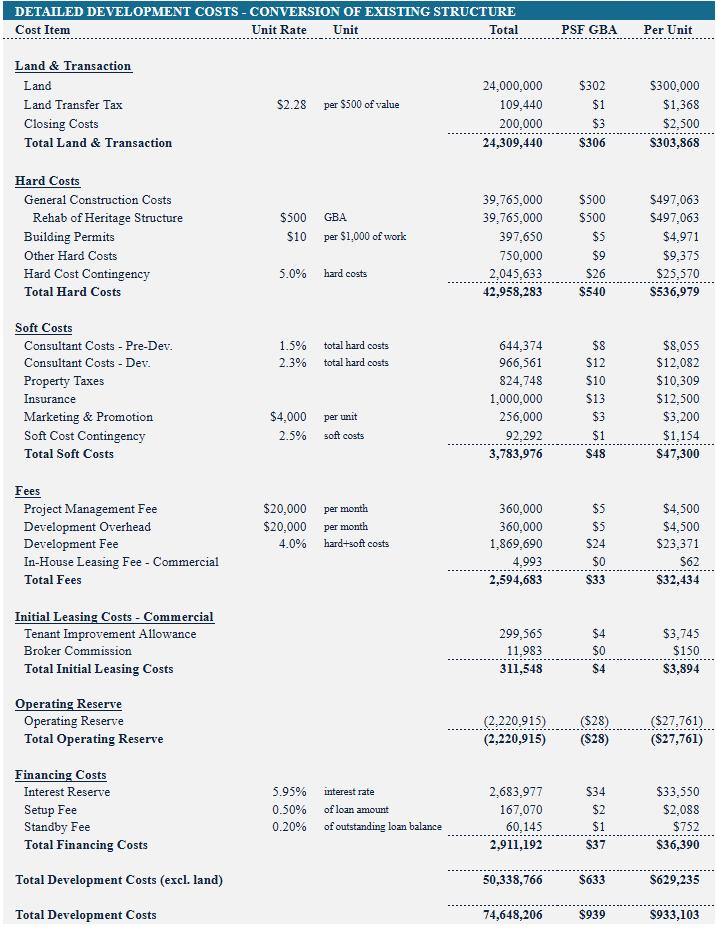

Regarding total development cost (TDC), the team used the $24M acquisition price that Continuum Developments, a local developer, paid for the building in October 2025. Another local developer, Oxford Properties, provided high-level feedback that total development costs, inclusive of land, range from $750K per unit for wood-frame construction and between $0.9-1.1M per unit for high-rise construction (70’ and higher). Given that the existing building was rehabilitated in 2020 by the prior owner CIM Group, a construction cost of $500 PSF. Inclusive of building permit fees and a 5% contingency, total hard costs are $540K per unit. Consultant fees were assumed to be 3.8% of hard costs. Insurance was assumed to be $1,000,000 and property taxes were calculated using the building’s current assessed value and tax rates. Developer and project manager overhead total $40K per month of construction and a developer fee of 4% of hard and soft costs was assumed. Deal costs for the maker spaces were assumed to be $50 PSF. Inclusive of financing costs and an operating reserve, TDC is $74.7M ($934K per

unit). A line-by-line breakdown can be seen in Appendix A.

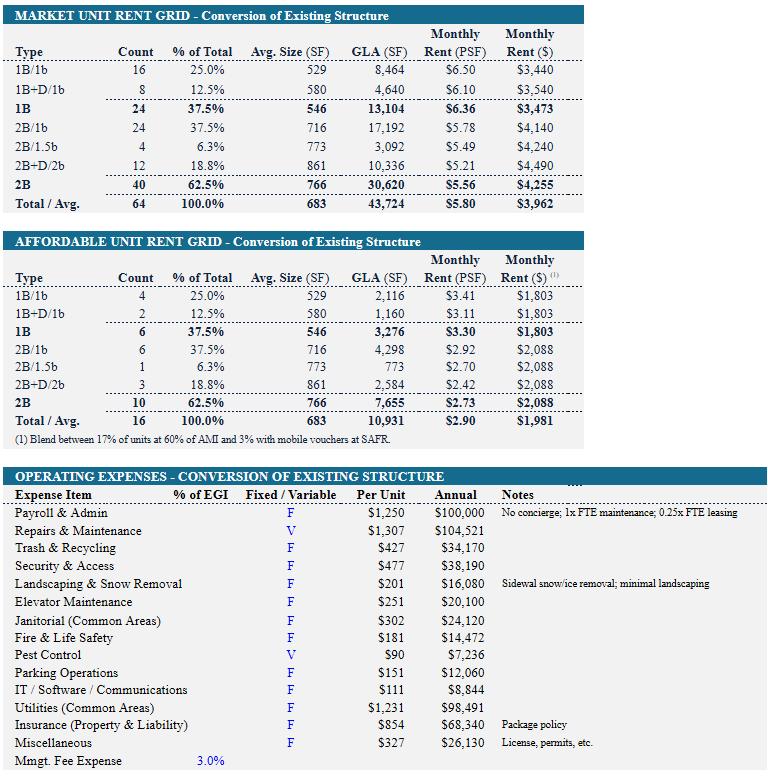

To triangulate market rents, the team reviewed asking rates at two recently completed projects in South End: Troy Boston, a 378-unit institutional multifamily product, and Ink Block, a 315-unit upscale loft style product. Troy Boston is averaging $3,510 per unit and Ink Block $4,000 per unit. The rents were skewed towards Ink Block, with a slight discount on monthly rents due to a smaller unit size. All-in, untrended (i.e. today) monthly rents average at $3,962 per unit ($5.80 PSF). Unit-by-unit rents can be seen in Appendix A. Year-over-year rent growth of 3% was assumed.

Rents for the affordable units were pulled from public sources. 17% of the units must be made available to the public at an average of 60% of Area Median Income (AMI) and 3% for households that qualify for mobile housing vouchers at no higher than the Small Area Fair Market Rent (SAFMR) for 95 Berkeley’s zip code. The AMI data is published by the City of Boston Mayors’ Office of Housing (MOH) and SAFR by HUD. On average, affordable rents in the building are $1,981 per unit ($2.90 PSF) – exactly 50% of market rents. Unit-by-unit rents can be seen in Appendix A. AMI and SAFR were also assumed to increase by 3% year-over-year.

Maker spaces were assumed to be triple-net leases (i.e. common area maintenance, property taxes and utilities are paid by them), with 5 year lease terms at a $30 PSF starting rent. Annual rent escalation was assumed to be 3%, with rate increases happening at the start of year 3 and year 5. 3 months of free rent was provided to provide financial flexibility during their ramp-up.

The operations of the building will be overseen by a third-party property management company for a fee of 3% of rent receipts. The operating model will be lean, with no concierge and no on-site leasing manager after full occupancy. Residents will have access to an access control application that will allow for secure entry into the building and parcel lockers as well as amenity reservations. Operating contracts total $175K per year ($2,200 per unit) and include access control, common area janitorial services, parking operations, trash and recycling, landscaping and snow removal, elevator maintenance, fire and life safety, pest control, IT, software, and communications. Salaries totaling $100K annually were assumed for a full-time maintenance manager

and a fractional leasing manager. Repairs and maintenance for unit turnover and common areas was assumed to be ~$1,300 per unit ($104K annually). Property and liability insurance was assumed to be $68K per year, common area utilities $98K per year and miscellaneous expenses at $26K per year. Property taxes are based on an assumed assessed value of $37.3M, with the residential component totaling $416K per year. However, with the 75% tax abatement offered by the City, residential property taxes are reduced to $104K per year. The blended growth rate for all operating expenses is assumed to match rent growth at 3% per year. All-in, at stabilization, the operating expense ratio is 22.5% of rent receipts, 8.8% lower than a scenario without the property tax abatement. See Appendix A for line-by-line operating expense assumptions.

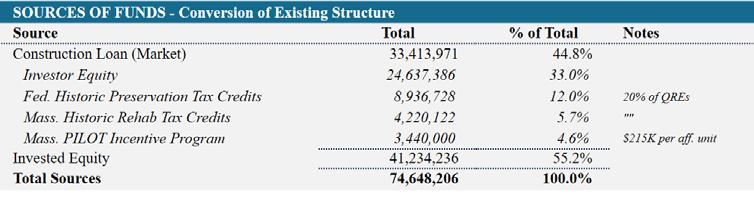

In terms of asset valuation, market cap rates in the South End are averaging 4.6%. Continued supply shortages in Boston and declines in the 10-year Treasury rate are anticipated to put downward pressure on market cap rates. While CoStar predicts a 4.4% cap rate for the South End / Back Bay sub-market in 2028, the assumption used for 95 Berkeley is 4.3% due to its location and quality. At stabilization, the gross asset value is expected to be $71.7M ($896K per unit).

Financing is based on typical market lending terms. The construction loan is anticipated to be $33.4M (45% of TDC), sized by the property’s stabilized NOI and a typical debt service coverage ratio floor of 1.25. This leaves a $41.2M financing gap (55% of TDC). The state and federal historical tax credit programs are anticipated to cover a combined $13.2M and the Pilot Program incentive funding $3.4M. Net of these incentives, investors can expect a total check size of $24.6M (33% of TDC). The construction loan interest rate, which floats at a spread over the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR), is anticipated to average 6.0%. The takeout loan is assumed to have a 30-year amortization period and a 6.2% fixed interest rate (175 bps over the 5-year Treasury rate).

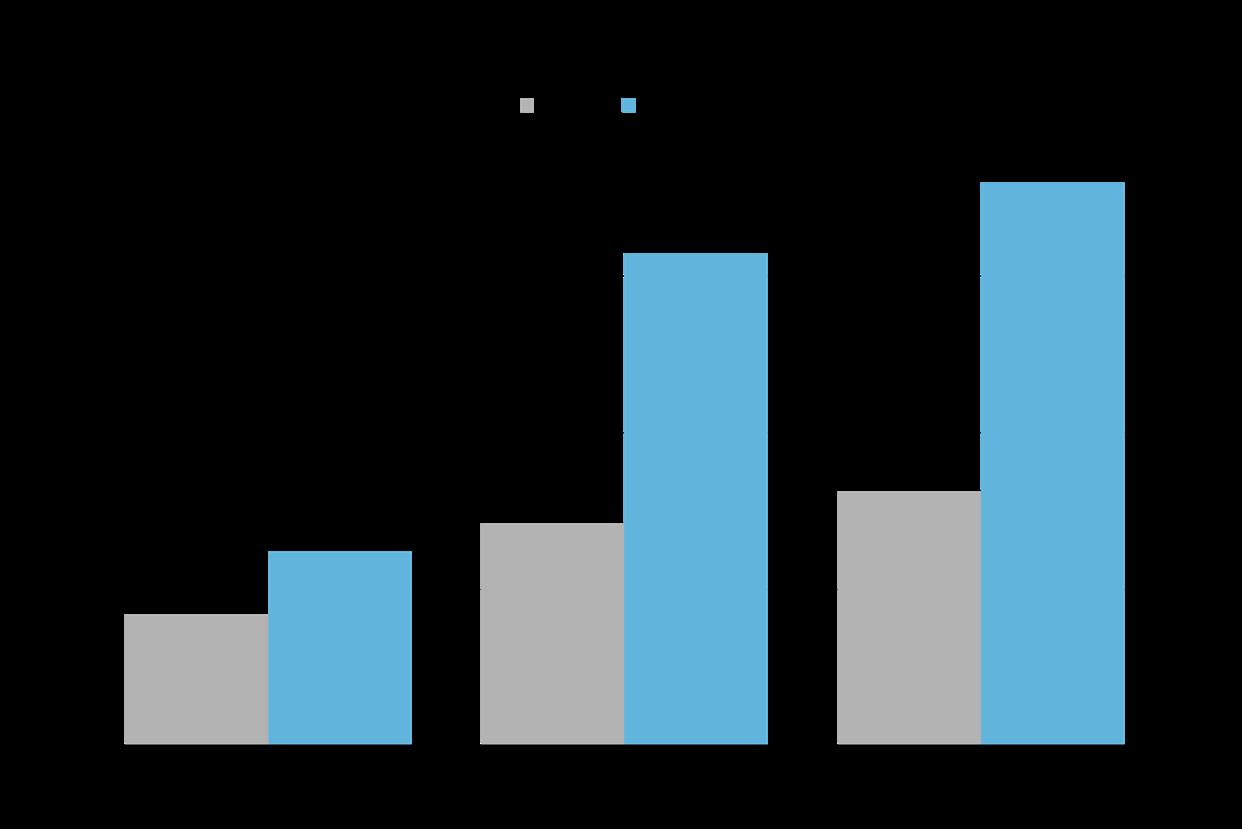

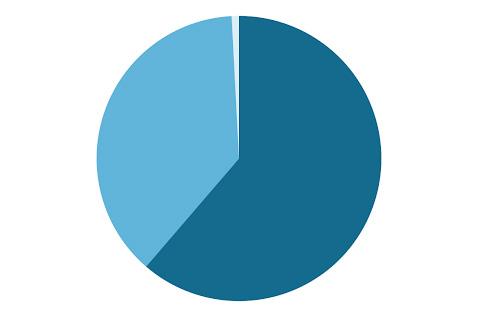

Overall, the returns are not compelling. If the project were to be sold at stabilization, the net sales proceeds would be less than TDC, resulting

in negative development profit of $3.5M. The yield-on-cost and cash-on-cash returns are 4.1% and 2.5%, respectively. The unlevered IRR for a sale at stabilization (i.e. development-period IRR), the likely route for a merchant developer, is -0.2%. Adding in tax incentives and leverage, the IRR increases to 15.7% (gross of fees and/ or promote). Finally, the development-period equity multiple is 1.4x (gross of fees and/or promote). A typical return profile for this type of development would be a 20-25% profit-on-cost and 20%+ levered development-period IRR, well above the returns generated by 95 Berkeley.

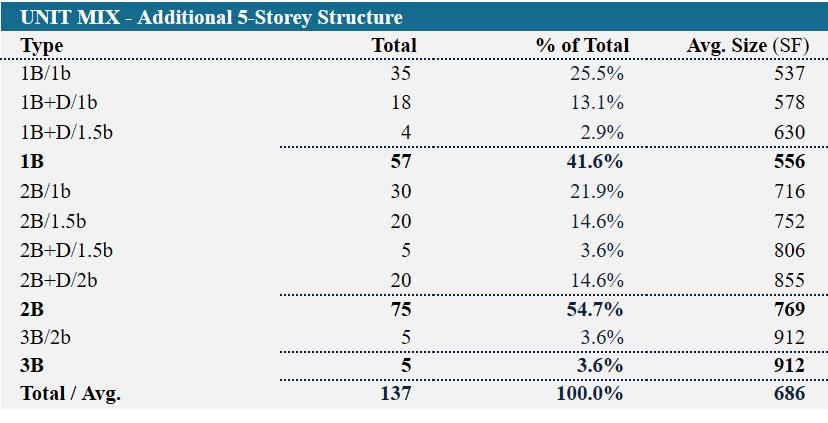

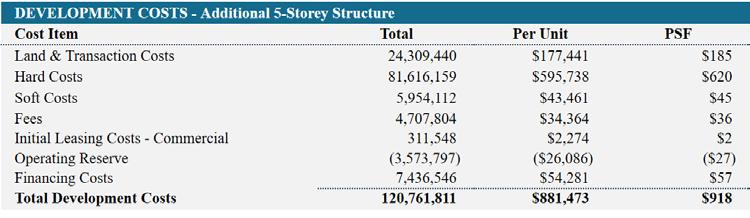

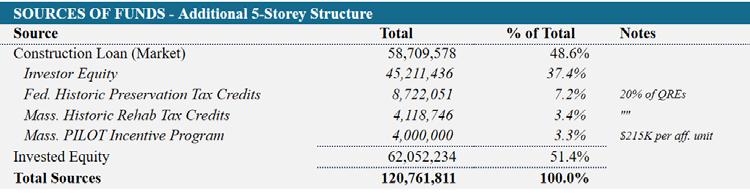

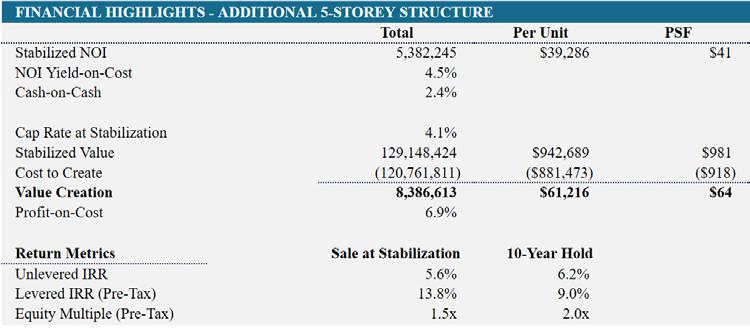

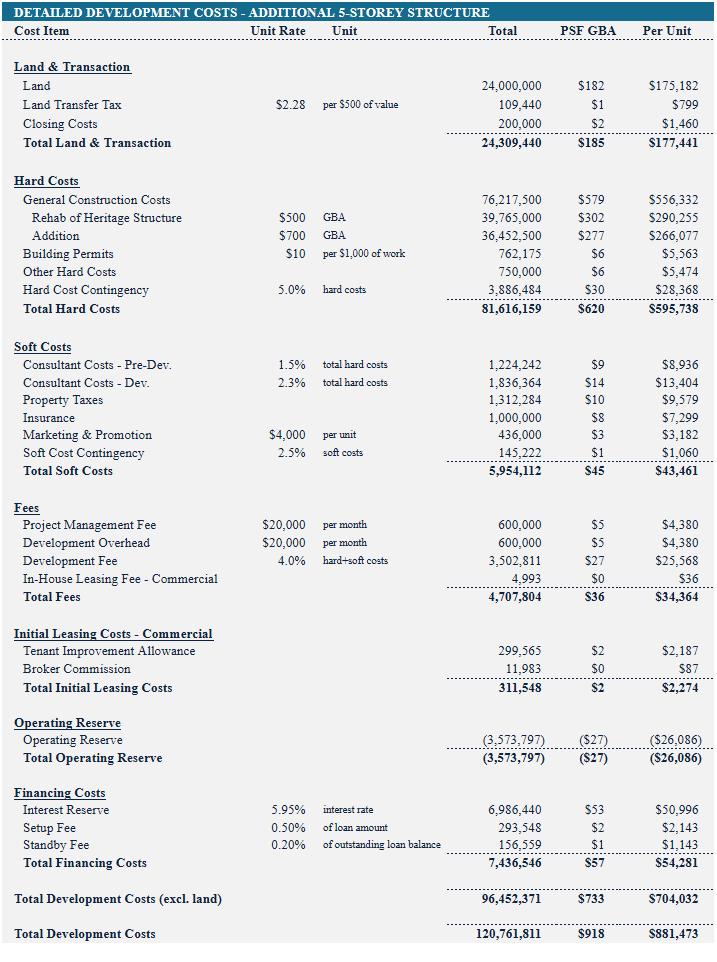

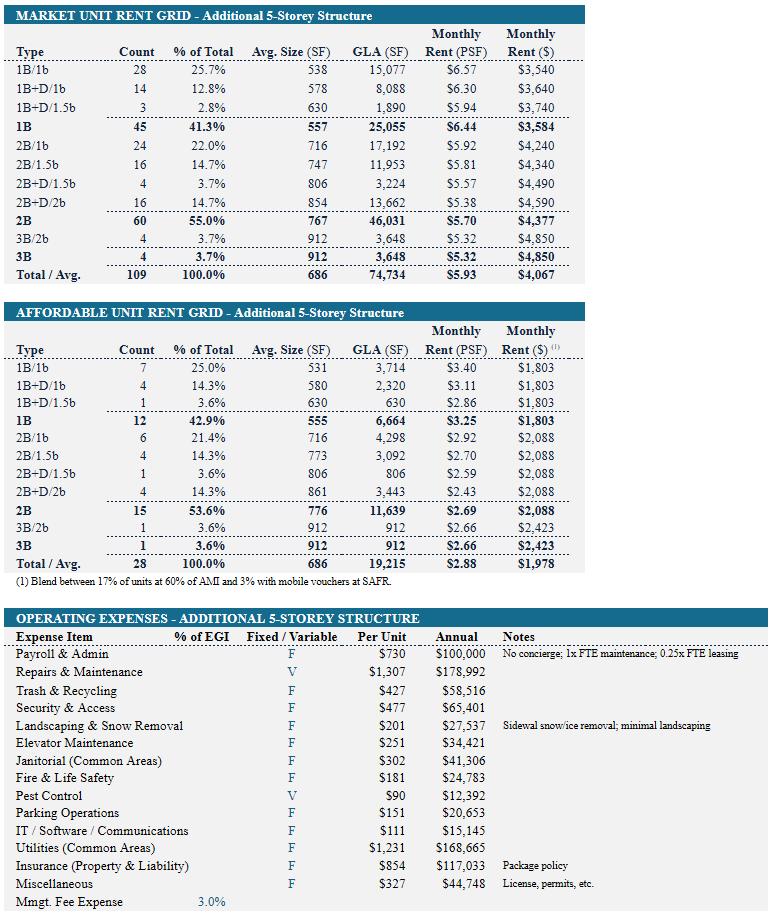

Additional 5-Storey Structure

With the additional 5-storey structure and 57 units, a few modifications needed to be made to the assumptions.

The construction duration is extended by 12 months, increasing the overall project duration from 2.5 years to 3.5 years. (See Appendix A For Timeline)

TDC increases from $74.7M to $120.8M, driven by an additional $700 PSF of construction costs for the added structure. The $200 PSF premium is driven by the fact that the entire structure is deemed as high-rise, which triggers mandatory safety upgrades such as pressurized stairwells, emergency generators, and automatic sprinklers. Hard cost contingency, consultant costs, development fes, developer and project manager overhead, and financing costs all scale due to increased scope and project duration. Land cost, however, stays fixed at $24M. As such, TDC per unit decreases from $934K to $881K per unit – density truly does decrease proportionate costs! A line-by-line breakdown can be seen in Appendix B.

To account for height premiums in the added structure and the added sky lounge amenity area, the average untrended market rents were increased to by $105 per unit ($0.13 PSF) to $4,067 per unit ($5.93 PSF). Average rents for affordable units change immaterially due to the modification in the overall unit mix. Unit-by-unit rents can be seen in Appendix B.

While salaries stay the same, operating contracts, insurance, utilities and miscellaneous property taxes are scaled proportionate to the number of units. The result is an operating expense ratio of 21.1%. See Appendix H for line-by-line operating expense assumptions.

Given that the building will now stabilize one year later, the cap rate is expected to compress another 10 bps to 4.1%, resulting in a gross asset value at stabilization of $948K per unit ($130.0M total).

The construction loan increases to $58.7M (49% of TDC), with a financing gap of $62.0M (51% of TDC). State and federal historic tax credits cover a combined $12.8M and the Pilot Program incentive funding $4.0M (it reaches the cap). Net of these incentives, investors can expect a total check size of $45.2M (37% of TDC).

Overall, the returns improve with the additional structure but are still below investor expectations. The project now generates a positive development profit of $8.3M. The yield-on-cost increases 40 bps to 4.5%. The levered development-period IRR decreases from 15.7% to 13.8% due to added construction loan interest carry resulting from 12 added months of construction. The development-period equity multiple increases to 1.5x.

Policy Changes to Make Conversions

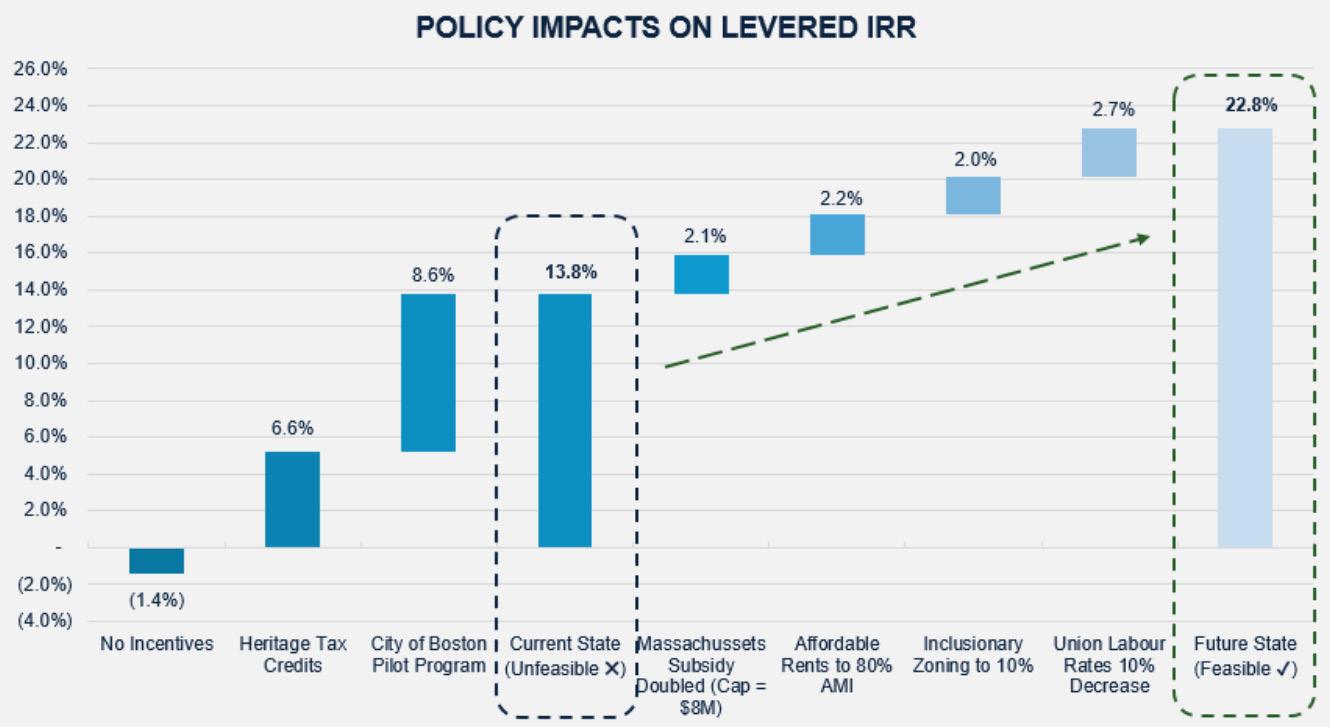

95 Berkeley is a best case scenario for office-to-residential conversion projects. It can almost certainly take advantage of federal and state tax credit programs due to its location in the South End Landmark District. The recent renovation by the previous owner reduces hard cost requirements. The floor plate depth is relatively shallow and the column grid is regular and wide, allowing for good unit layouts. The columns indicate structural bearing capacity, perfect for a 5-storey addition. Conversion of the existing building has already been approved by the BPDA, meaning development permitting risk is mitigated.

Despite all of these positive attributes, heritage tax credits and new office-to-residential conversion incentives from the city of Boston and state of Massachusetts still do not result in a feasible project.

Mayor Wu has a few options available to make conversions more feasible.

Go back to Governor Maura Healey and Lt. Governor Kim Driscoll to ask for double the existing state funding ($215K per unit, with a cap of $4M). If the state agrees, this could add 210 bps to the levered development-period IRR

Adjust the IDP by increasing the percentage of AMI to 80%. The rationale for this policy change could easily be explained and is less politically fragile than adjusting the overall requirement. If

the percentage of AMI is increased by 20%, 220 bps could to the levered development-period IRR

Further adjust the IDP by reducing the requirement from 20% to 10%. While this is a much more significant policy change than simply adjusting percentage of AMI, it is much better than eliminating the requirement entirely. Making this change would add 200 bps to the levered development-period IRR

Work with the unions to reduce their labour rates by 10% on office-to-residential conversions, while making union labour a requirement for all projects benefitting from the city’s incentive program. Mayor Wu has created a positive relationship with the Greater Boston Building Trades Unions and the North Atlantic States Regional Council of Carpenters and could use this as leverage, while providing the trades with a pipeline of projects. Reducing labour rates by 10% would add 270 bps to the levered development-period IRR

Conclusion

The redevelopment of 95 Berkeley represents both a rare opportunity and a broader model for how Boston can reposition its aging office stock to meet urgent housing needs while honoring the architectural character of its historic neighborhoods. While financial feasibility remains challenged even with substantial incentive programs, the study makes clear that targeted policy adjustments could unlock a scalable pathway for future conversions.

Bibliography

1 CoStar Group. (n.d.). Property summary 19759347. https://product.costar. com/detail/all-properties/19759347/summary

2 CoStar Group. (2025). 95 Berkeley St: Rent comparables and construction survey [PDF]. Prepared for Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

3 Boston Planning & Development Agency. (n.d.). 95 Berkeley Street. https://www. bostonplans.org/projects/development-projects/95-berkeley-street

4 CBT Architects & CIM Group. (2024, August 6). 95 Berkeley: SELDC presentation [PDF].

5 WBUR. (2024, July 8). Converting Boston’s offices to housing is tricky, but it’s starting to happen. WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/ news/2024/07/08/office-housing-conversions-residential-boston-real-estate

6 Global Boston. (n.d.). The South End. https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/ home/immigrant-places/the-south-end/

7 CBT Architects, Continuum Partners, & Fortium Partners. (2025, October 15). 95 Berkeley Street: Office-to-residential conversion public meeting presentation [PDF].

8 Trust for Architectural Easements. (n.d.). South End Historic District. https:// architecturaltrust.org/easements/aboutthe-trust/trust-protected-communities/ historic-districts-in-massachusetts/ south-end-historic-district/

9 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table B25070: Gross Rent as a Percentage of Household Income) [Data sets]. https://www.census. gov/programs-surveys/acs

10 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S0101: Age and Sex) [Data sets]. https://www.census. gov/programs-surveys/acs

11 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S0701: Geographic Mobility) [Data sets]. https:// www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

12 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S0802: Means of Transportation to Work) [Data sets]. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

13 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S1201:

Marital Status) [Data sets]. https://www. census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

14 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S1501: Educational Attainment) [Data sets]. https:// www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

15 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S1901: Income in the Past 12 Months) [Data sets]. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ acs

16 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S2301: Employment Status) [Data sets]. https:// www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

17 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S2402: Occupation by Sex) [Data sets]. https:// www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

18 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010–2023). American Community Survey data (Table S2501: Occupancy Characteristics) [Data sets]. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ acs

19 FAA Inc. (n.d.). Residences at Penny Savings Bank project. https://www.faainc.com/project/residences-at-penny-savings-bank

20 FAA Inc. (n.d.). 226 Causeway Street project. https://www.faainc.com/project/226-causeway-street

21 FAA Inc. (n.d.). The Lucas – 136 Shawmut Ave project. https://www.faainc.com/project/the-lucas-136-shawmut-ave

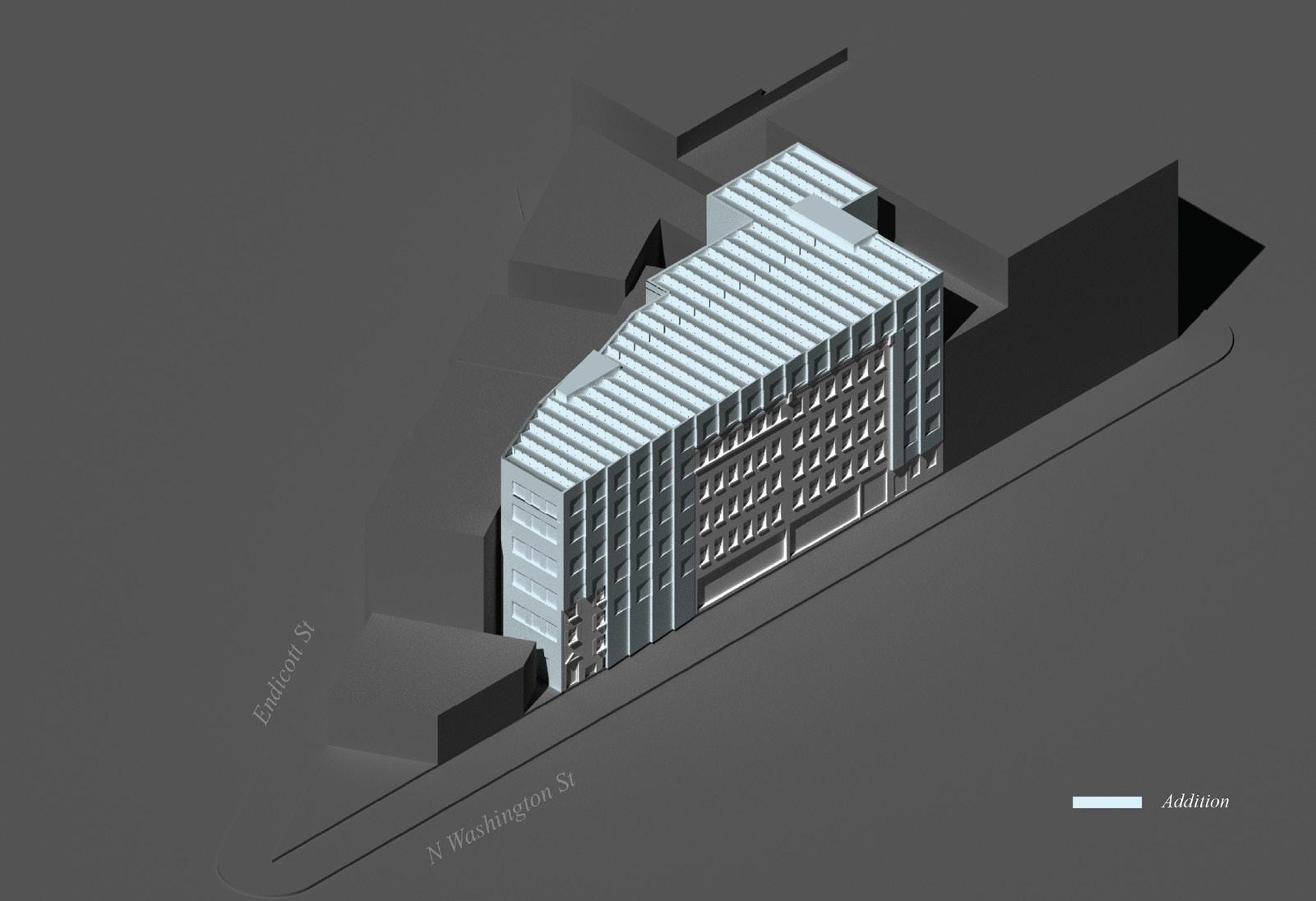

133–169 N Washington Street

Redevelopment Proposal

133–169 N Washington Street: Redevelopment Proposal

Executive Summary: The Conversion Challenge

This report evaluates the feasibility of converting a portfolio of vacant and distressed office buildings in Boston’s North End into multifamily residential housing. As Boston confronts rising office vacancies and a critical housing shortage, adaptive reuse has emerged as a vital strategy. However, the financial viability of such conversions remains constrained.

Recent studies, including the City of Boston’s Demystifying Development Costs, highlight that construction costs have surged, with per-unit development costs frequently exceeding $500,000 due to material price escalation, labor shortages, and high interest rates . Furthermore, the Office-to-Residential Conversion Program study notes that persistent feasibility gaps— driven by costly code upgrades, inefficient floorplates, and regulatory requirements—often render projects unprofitable without substantial

subsidies.

For this specific project, acquisition pricing serves as a compounding barrier. Despite the distressed nature of the assets, the current asking price does not reflect the economic realities of residential conversion. Consequently, the project faces a “dual burden” of high acquisition costs and elevated construction expenses. This report analyzes whether tax incentives and strategic design can bridge this feasibility gap.

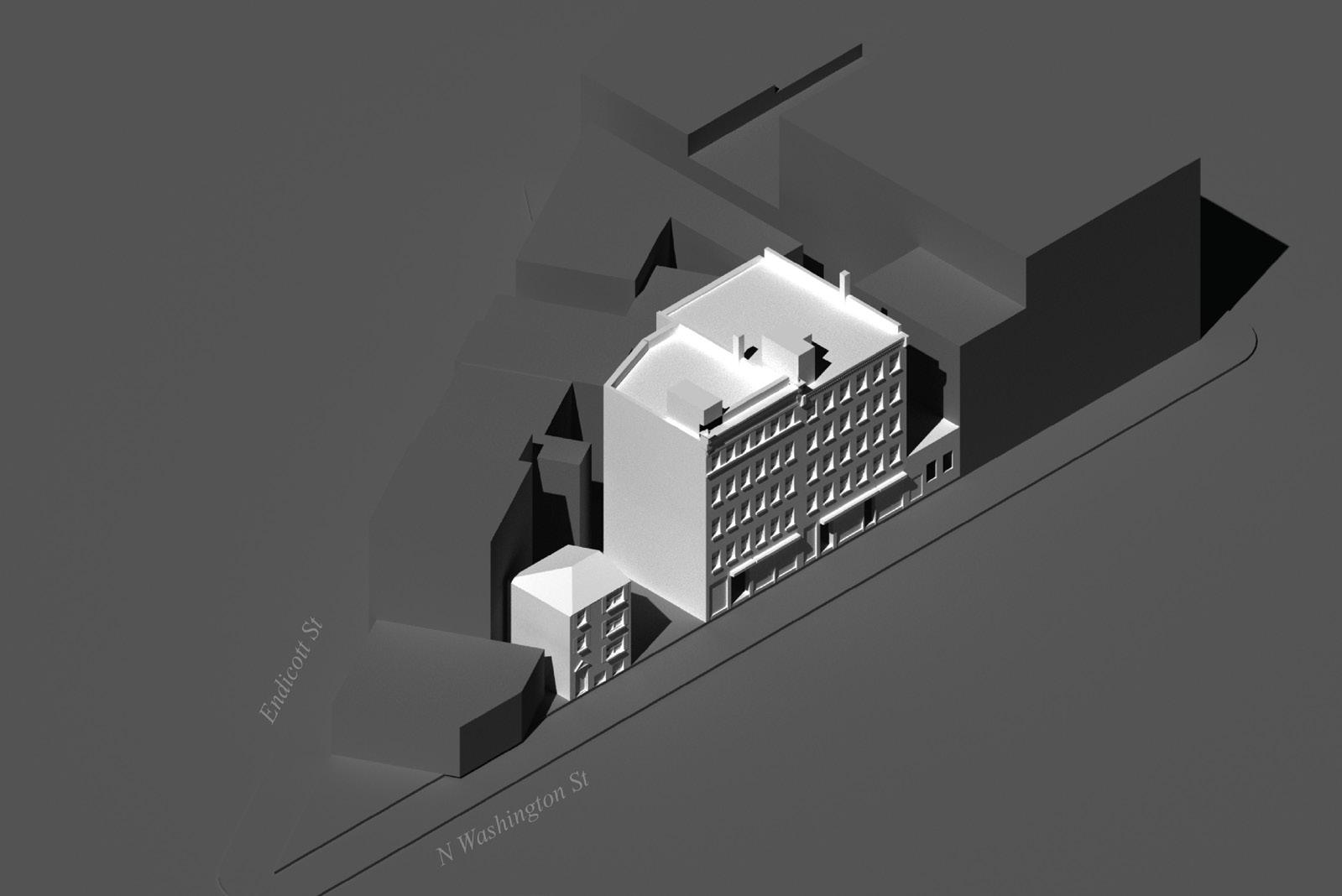

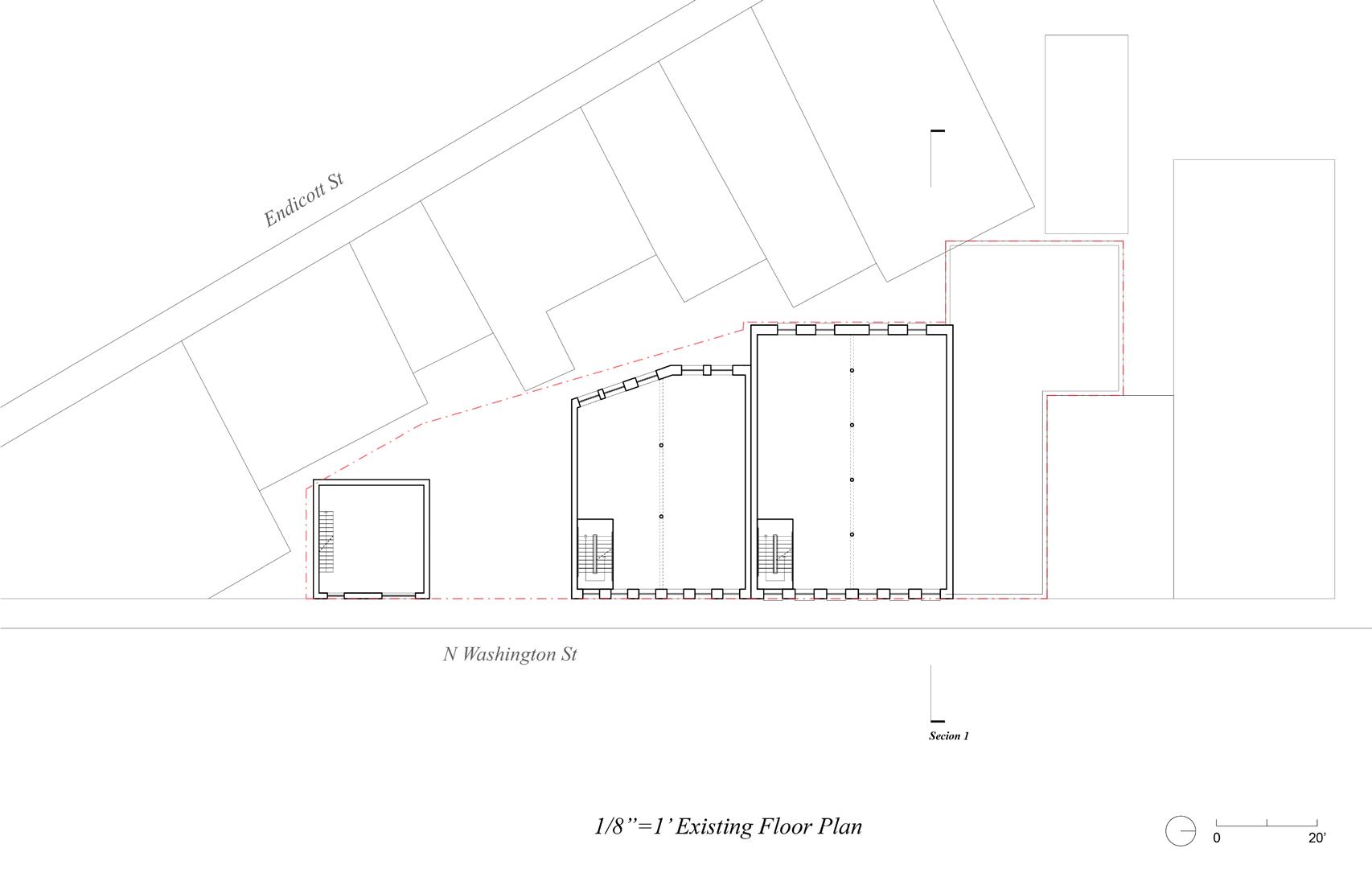

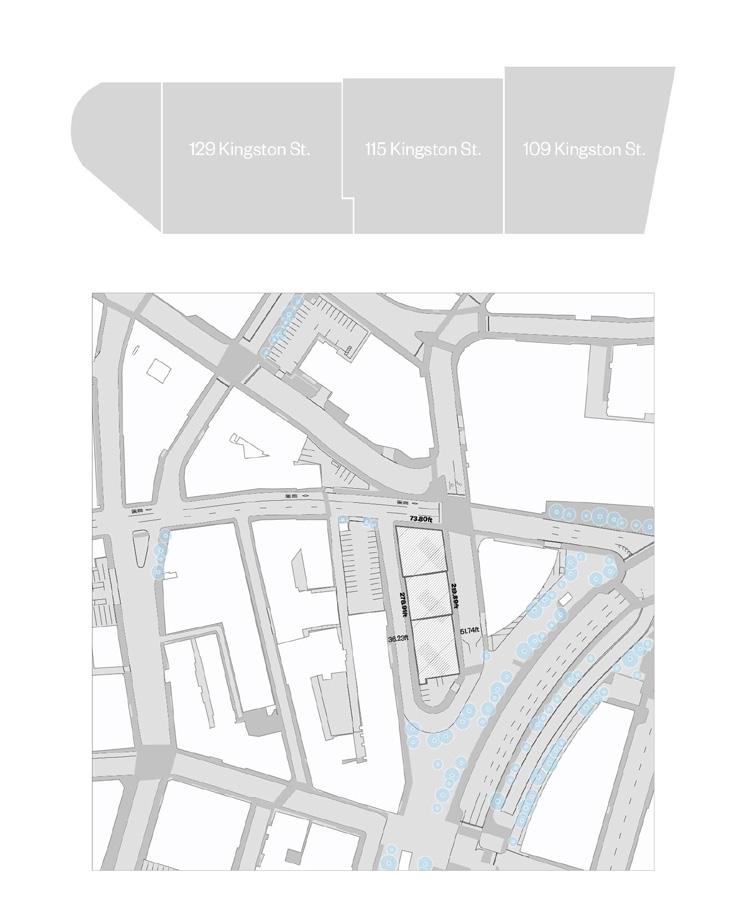

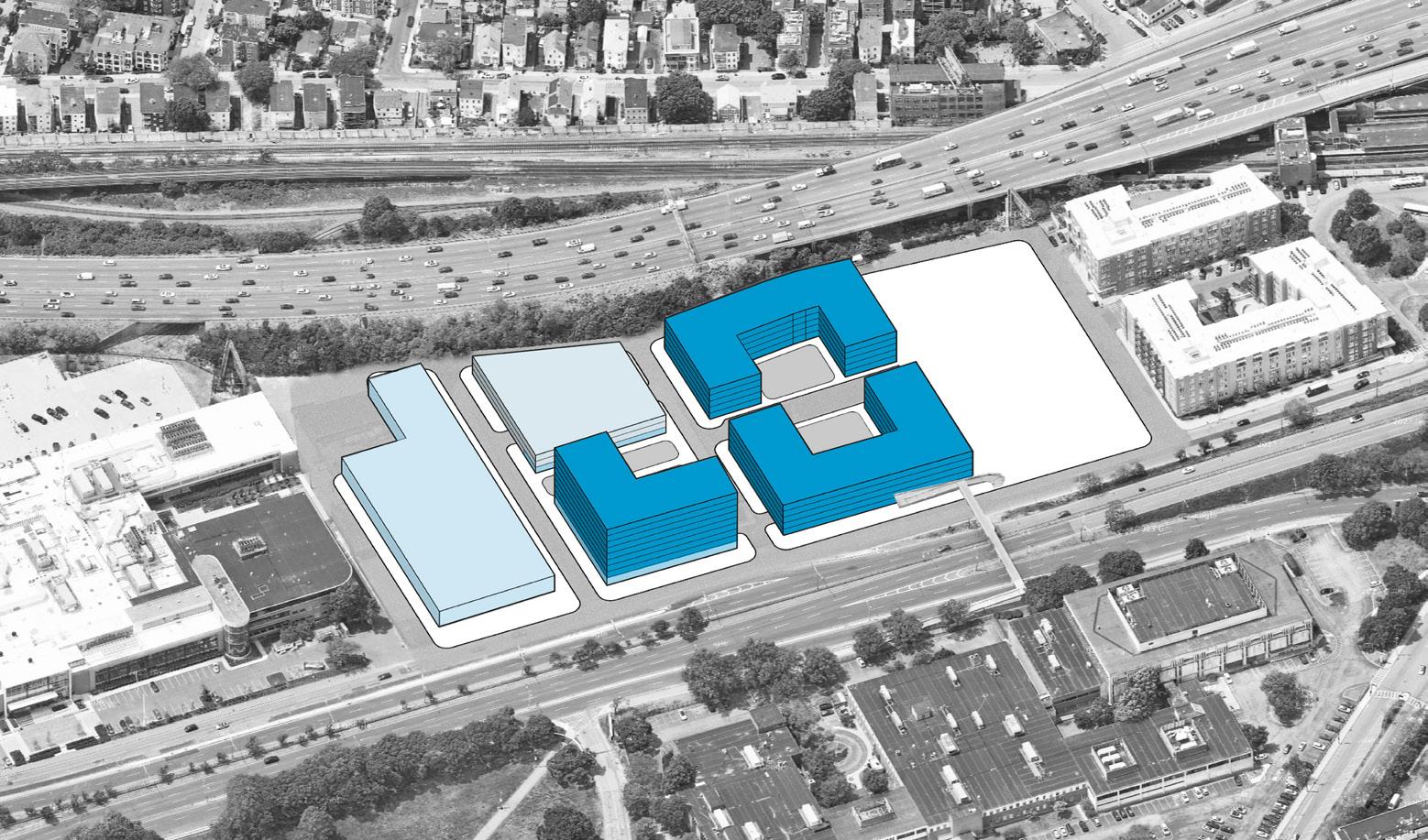

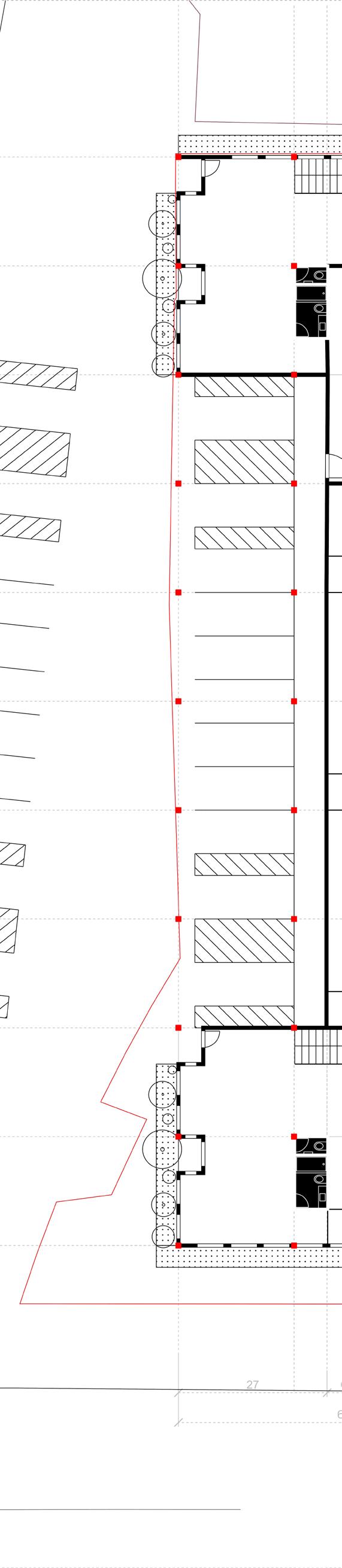

Project Introduction

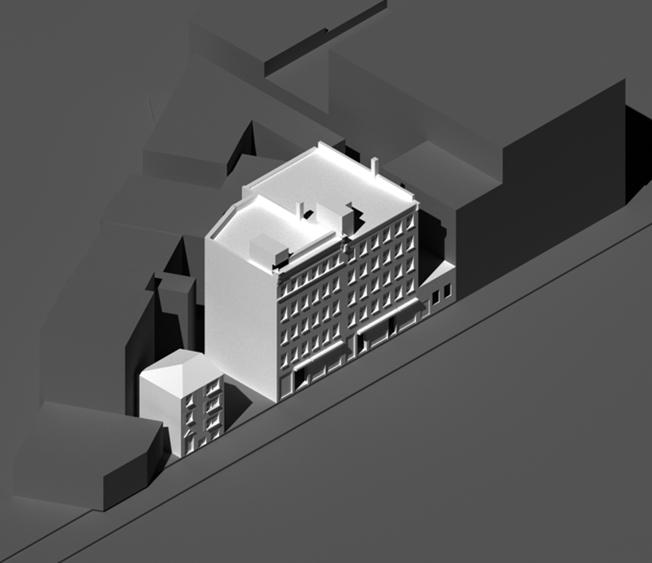

The proposed redevelopment site comprises 133–169 North Washington Street (Boston, MA 02114), a collection of six adjacent parcels in the historic North End. The site currently consists of four distinct structures:

• Two vacant commercial office buildings.

• One residential single-family home currently in bankruptcy.

• One single-story commercial office building

listed separately.

The combined asking price for these aggregated parcels is $11.3 million. Given the City of Boston’s strong policy support for adaptive reuse, this proposal explores transforming these underutilized assets into a cohesive multifamily development. The analysis is grounded in urban design principles, zoning review, market research, and architectural feasibility.

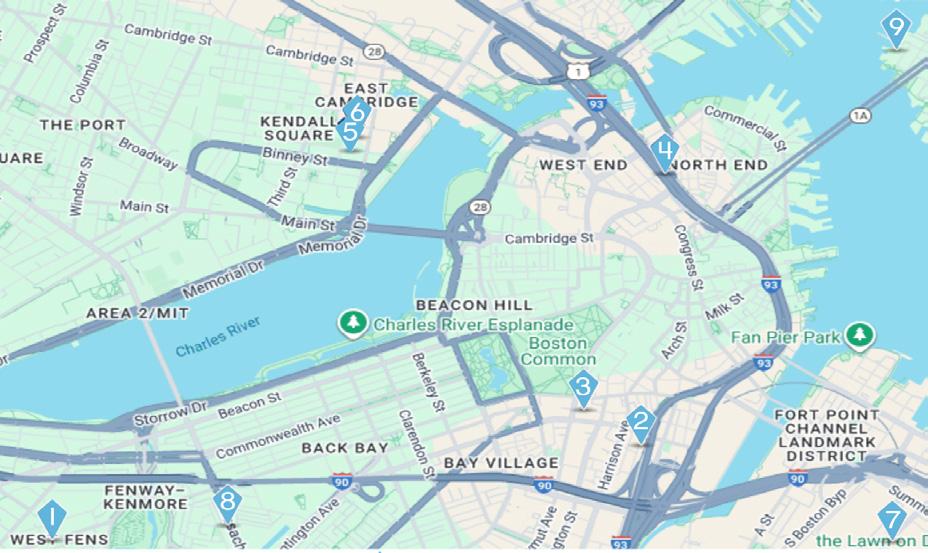

Site Description & Neighborhood Context

Site Characteristics Prominently located along North Washington Street, the site serves as a key connector between the North End, West End, Downtown, and the Greenway. While the existing commercial structures are aging, they benefit from robust masonry construction and intact roof assemblies. Crucially, the lot configuration allows for parcel aggregation, creating a contiguous development site that enables shared circulation, unified massing, and optimized residential layouts.

Neighborhood Fundamentals The North End is one of Boston’s most desirable and historic neighborhoods, characterized by high walkability, cultural vibrancy, and dense European-style streetscapes.

• Transit Access: The site offers immediate access to Haymarket and North Station (Green/ Orange Lines and Commuter Rail), providing direct connectivity to the Financial District.

• Amenities: Residents benefit from proximity to

TD Garden, waterfront parks, the Harborwalk, and a diverse mix of dining and retail options.

• Demographics: The area supports a strong housing market with a predominant base of renter households, ensuring long-term demand.

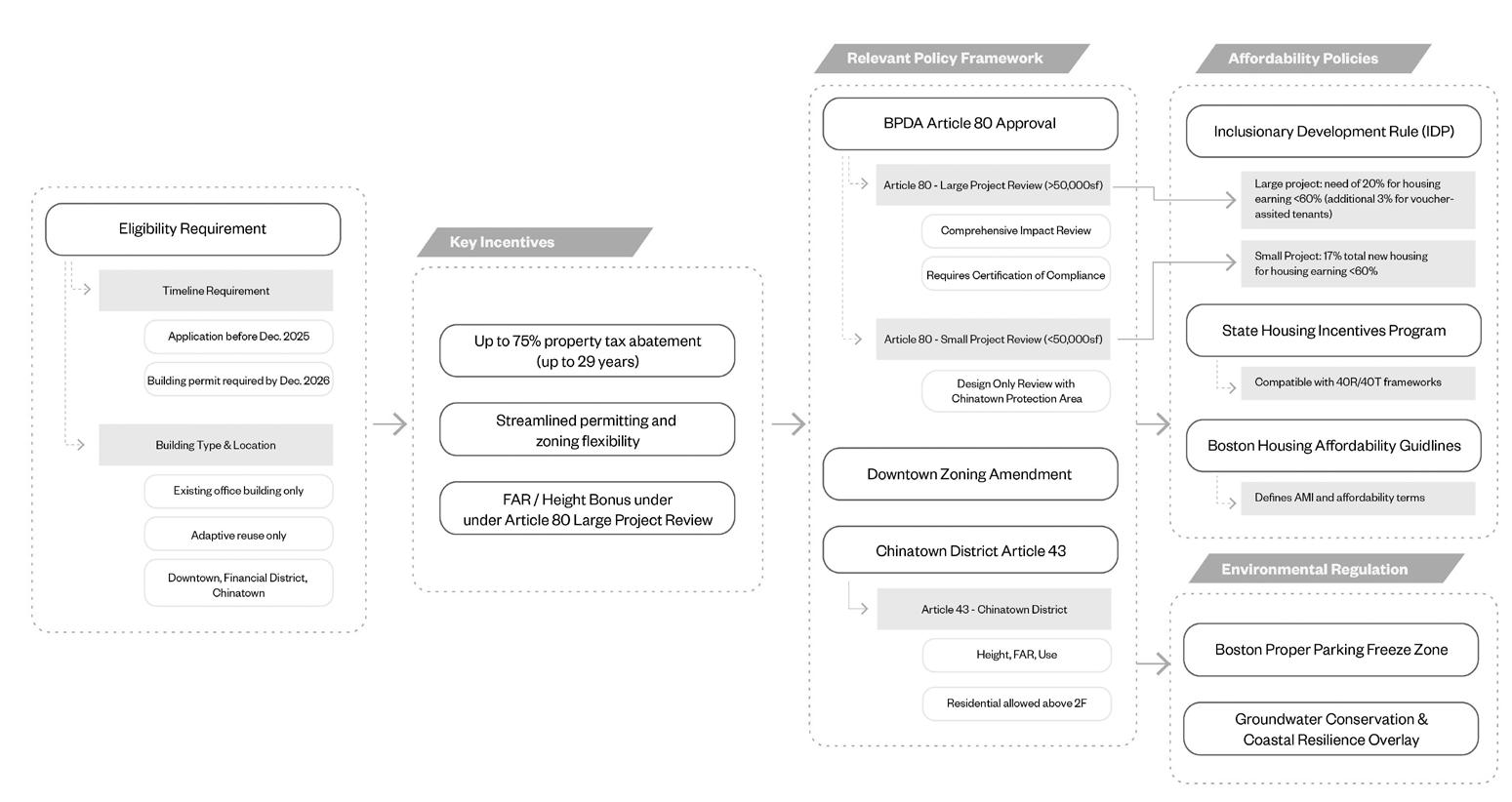

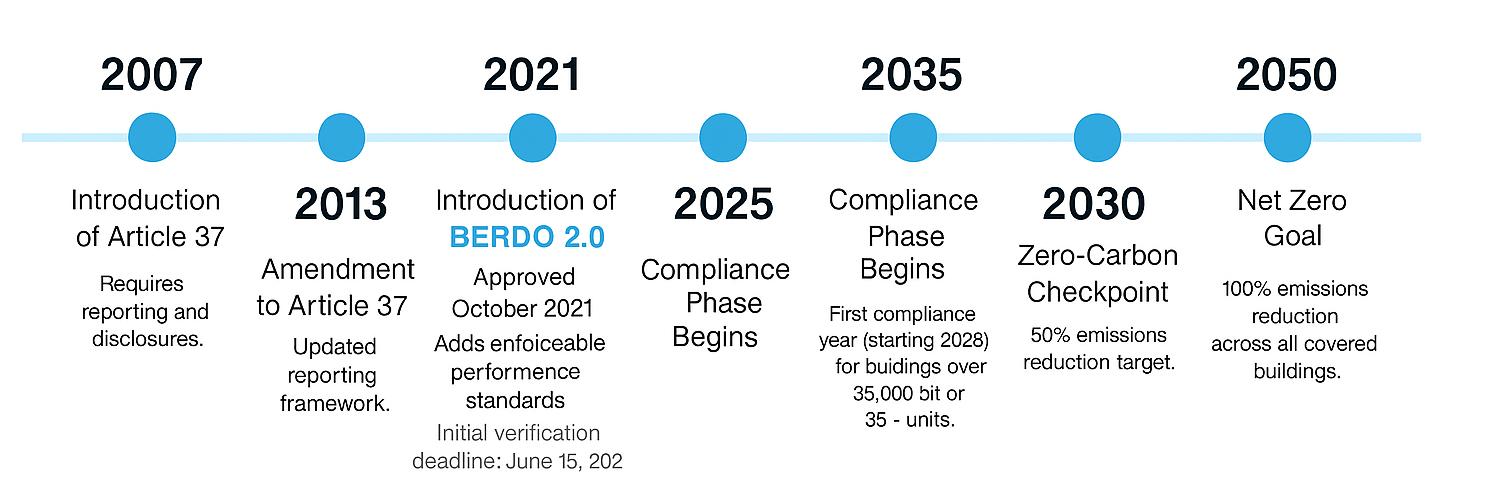

Development Incentives

Redeveloping this site aligns with several city and state initiatives, particularly Boston’s Office-to-Residential Conversion Program. This program was launched to address high downtown office vacancies and the city’s persistent housing shortage.

a. Key Incentive Programs

• City of Boston Office-to-Residential Conversion Program

• Up to 75% property tax abatement for 29 years

• Eligibility for as-of-right conversions

• Expedited permitting and review

• Historic Preservation Incentives

b. The site lies within the North End Historic District, making the project eligible for:

• 20% Federal Historic Tax Credits

• 20% Massachusetts Historic Tax Credits

• Affordable Housing Credits (LIHTC)

c. Depending on the final program mix, the project may utilize:

• 4% Federal and State LIHTC

• 9% Federal and State LIHTC

These incentives significantly improve feasibility and support adaptive reuse of existing structures, aligning private development goals with public policy priorities.

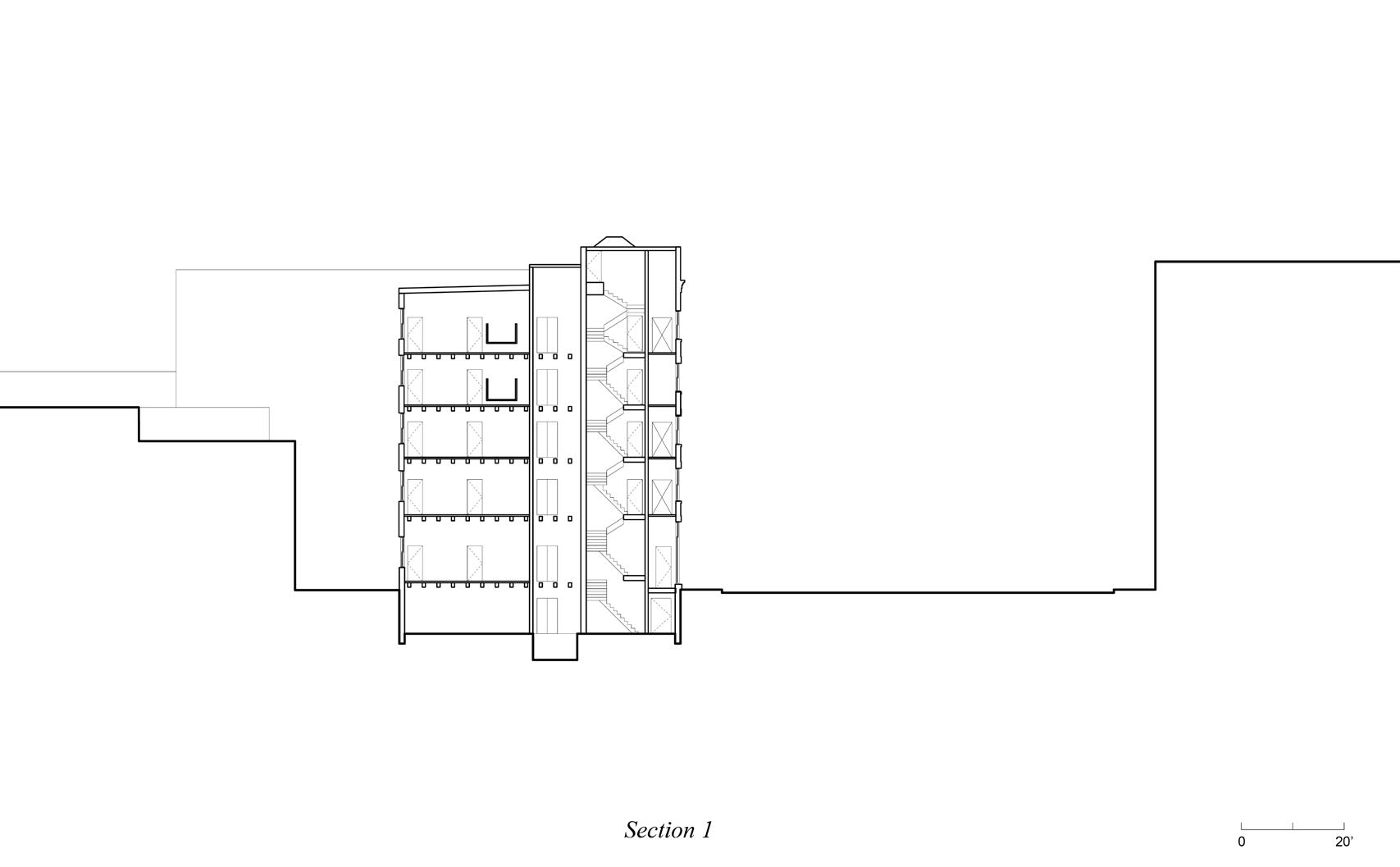

Existing Conditions and Site Challenges

A detailed site walkthrough revealed that the existing buildings, though outdated, possess structural qualities conducive to conversion rather than full demolition. The masonry facades are in strong condition, and the roof assemblies show no signs of critical failure. However, several challenges must be addressed:

a. Structural and Architectural Issues

• Uneven floor plates across buildings

• Inconsistent floor-to-ceiling heights, complicating uniform residential layouts

• A party wall separating structures and limiting corridor continuity

• Narrow and outdated stairwells requiring demolition and replacement

• Absence of an elevator, which must be added for residential use

b. Flood Resilience and Environmental Constraints

The site is within the Coastal Flood Resilience Overlay District. Therefore:

• The basement requires substantial waterproofing and floodproofing upgrades

• Mechanical equipment must be relocated or elevated

• Openings must meet flood-resilient design guidelines

These constraints introduce complexity but do not prohibit redevelopment. Instead, they require targeted upgrades that are typical for adaptive reuse projects in historic districts.

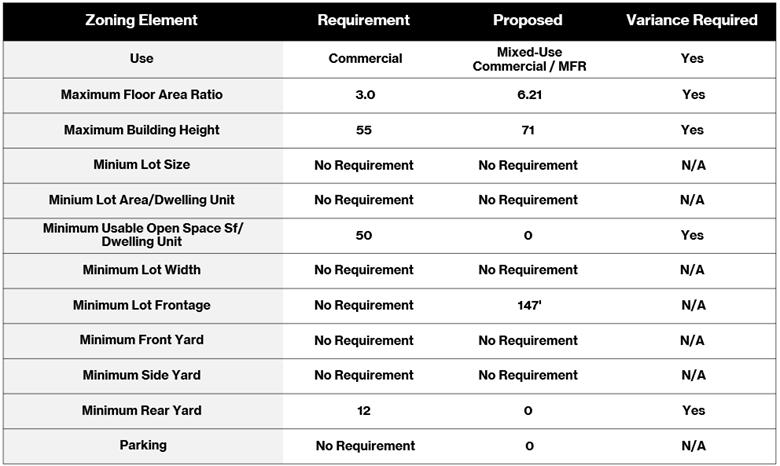

Zoning Analysis

Before exploring any design alternatives, we first examined the regulatory conditions governing the site within the North End Neighborhood District’s Community Commercial Subdistrict. This zoning review quickly clarified which directions were viable and which would require special approvals.

Although the existing building has long operated as an office property, the district’s current regulations restrict the site to commercial use only. Introducing residential units—whether fully multifamily or a mixed commercial-residential program—would therefore fall outside the permitted uses and necessitate a variance. The massing of the structure also exceeds what is allowed by right: the zoning caps FAR at 3.0 and a height of 55 feet. The project proposes a FAR of 6.21, and height of 71 feet.

The North End subdistrict imposes no minimum lot area, no minimum width or frontage requirements, and no mandated setbacks except for a modest rear yard condition. Notably, there is also no parking requirement, an important advantage given the property’s direct

proximity to North Station and high-frequency transit.

Taken together, the zoning review showed a mixed regulatory landscape: while use, FAR, and height variances are unavoidable, the absence of parking and dimensional restrictions provides considerable flexibility for a conversion. These conditions guided our test-fits and helped evaluate which redevelopment scenarios could realistically move forward.

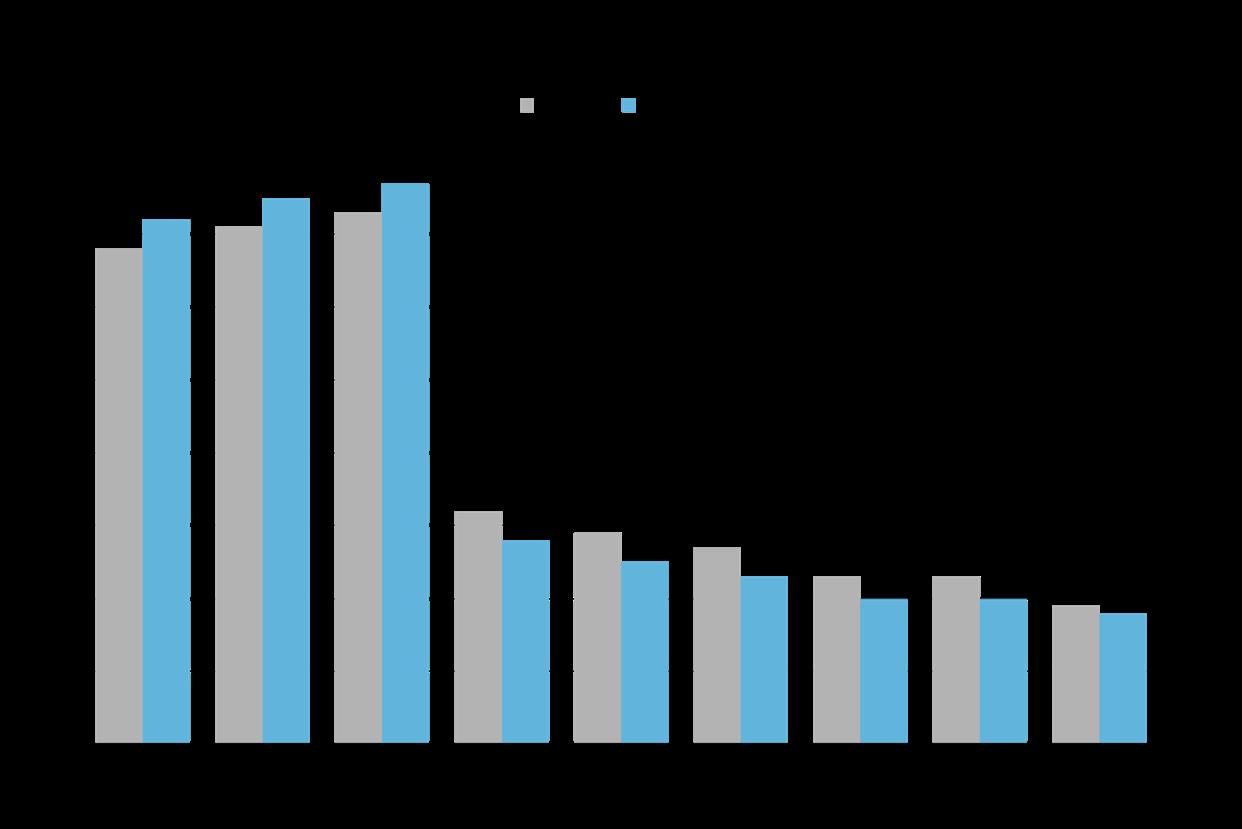

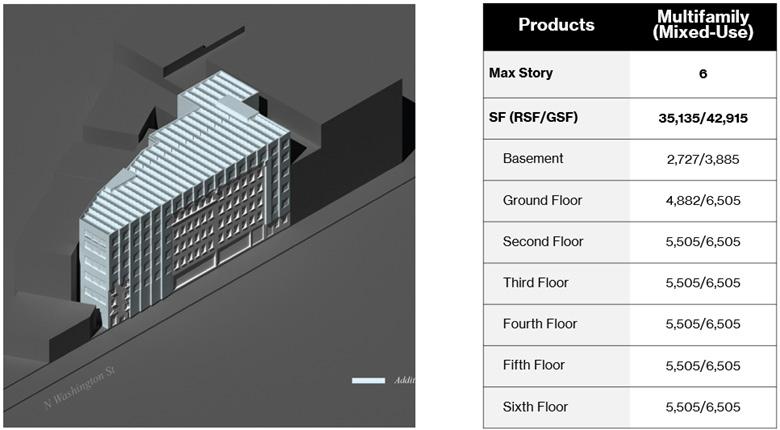

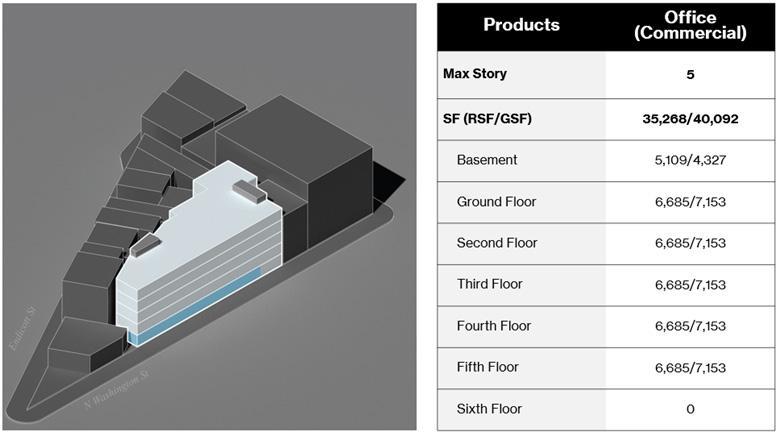

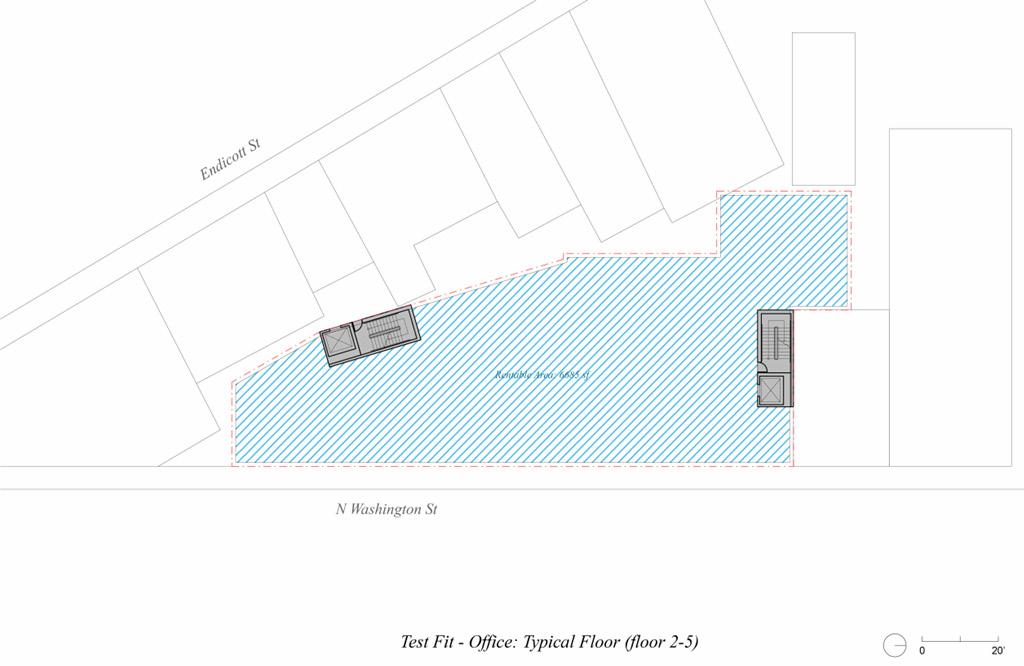

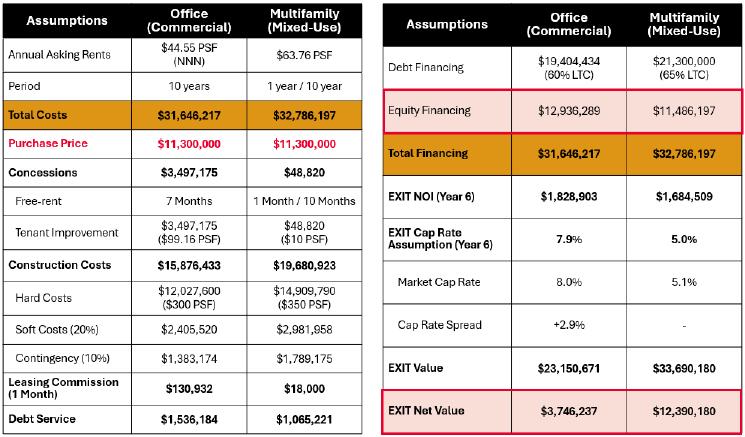

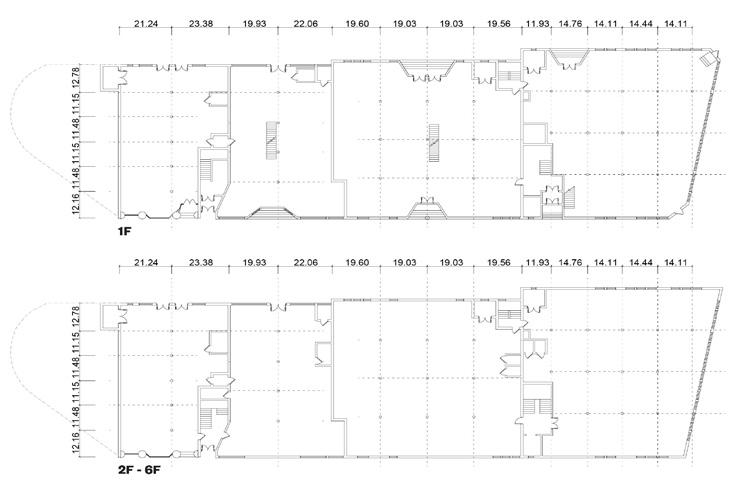

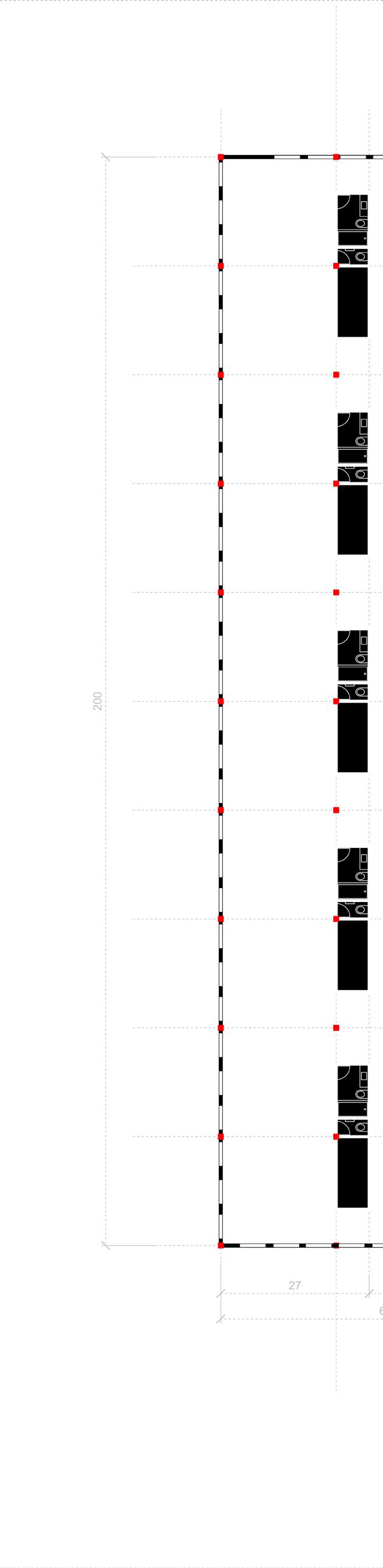

Test-Fits

To evaluate which program could realistically support a repositioning strategy, we compared two parallel paths: a five-story office configuration and a six-story multifamily conversion. Although the office test-fit was limited to one fewer floor, its deeper floorplates and lack of corridor or unit demising requirements produced 35,268 RSF, slightly exceeding the 35,135 RSF achieved under the multifamily layout. In other words, the inherent efficiency of office floorplates allowed a lower building to match— and even marginally exceed—the rentable area of a taller residential scheme.

However, when we translated these massing differences into financial terms, the distinction between the two options became much clearer. The redevelopment cost for the office scenario totaled $31.65 million, only slightly below the $32.79 million required for the multifamily conversion. The reason: although office requires less structural and interior work, the concessions needed to secure tenants in Boston’s current office market are extraordinarily high. We assumed seven months of free rent and a tenant improvement package of $99.16 PSF, resulting in more than $3.49 million in concession-related outlays for the office scenario. In contrast, the multifamily option required just $48,820 in concessions, reflecting significantly lower turnover costs and a more stable demand base.

Construction costs followed a similar logic. Office reuse required fewer interventions, resulting in hard costs of $12.03 million (approximately $300 PSF). The multifamily buildout, by contrast, required new residential systems, shafts, egress, and unit partitions—producing hard costs of $14.91 million (around $350 PSF). Even with this higher expense, the total project costs between the two scenarios remained closely aligned once concessions were factored in.

The most consequential difference emerged at exit. Using market-consistent assumptions, the stabilized office building generated an estimated Year-6 NOI of $1.83 million. However, applying a market cap rate of 7.9%, the resulting exit value was only $23.15 million, producing a very modest $3.75 million net value after accounting for project costs. By contrast, the multifamily conversion, despite a slightly lower NOI of $1.68 million, benefited from a much healthier valuation environment. Applying a 5.0% cap rate yielded an exit value of $33.69 million, resulting in a substantially stronger $12.39 million net value—more than three times that of the office scenario.

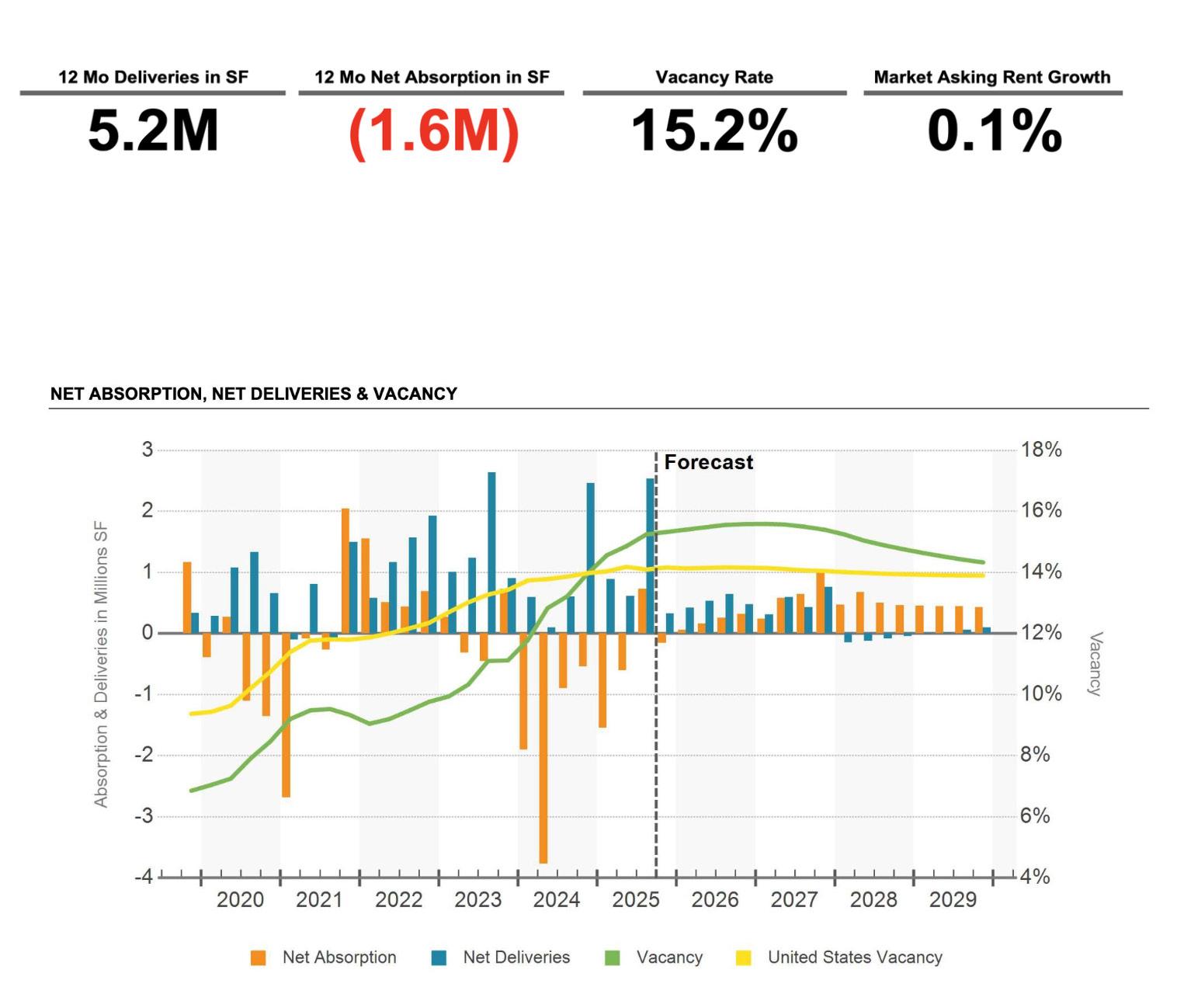

Taken together, the quantitative comparison made the direction unmistakably clear. Office reuse faces three structural disadvantages in today’s Boston market:

• Cap rates nearly 300 bps higher (8.0% vs. 5.1% for multifamily, Source: Costar)

• Vacancy levels four times greater (24.3% vs. 6.3%, Source: Colliers)

• Turnover costs that reset with every lease cycle (7 months free rent + $99 PSF TI, Source: Avison Young)

Multifamily, in contrast, offers lower concessions, lower vacancy risk, and a valua-

tion environment that rewards stability. Even though it requires more construction investment upfront, the long-term financial performance overwhelmingly favors a residential conversion.

Market Analysis

The North End is one of Boston’s most historic and walkable neighborhoods, known for its dense urban fabric, rich Italian-American heritage, and proximity to major employment centers such as Downtown, the Financial District, and the West End. With exceptional mobility scores (Walk Score 99, Transit Score 100, Bike Score 90), the area offers residents unmatched access to transportation and daily amenities.

According to City of Boston Planning Department Research Division 2025 Estimates, Demographically, the North End is an affluent and professionally oriented submarket. The median household income is $114,115, significantly higher than the citywide average, and more than 33% of households earn above $150,000. Approximately 70% of the employed population works in management, business, science, or arts occupations, indicating a stable, high-income tenant base that favors rental housing in this neighborhood.

The neighborhood is also heavily renter-driven, meaning more than 74% of households are renters . Commuting patterns further reinforce the suitability for multifamily housing; a city of Boston survey indicated that 3,421 residents walk to work, 1,306 use public transit, and over 2,114 work from home, all of which point to strong demand for transit-oriented, amenitized multifamily apartments.

Given its demographic strength, renter dominance, walkability, and proximity to North Station, the North End presents favorable conditions for office-to-residential conversion / multifamily redevelopment. The proposed unit mix, primarily 1B1B and studio units, aligns well with the neighborhood’s tenant profile and supports long-term absorption and rent stability.

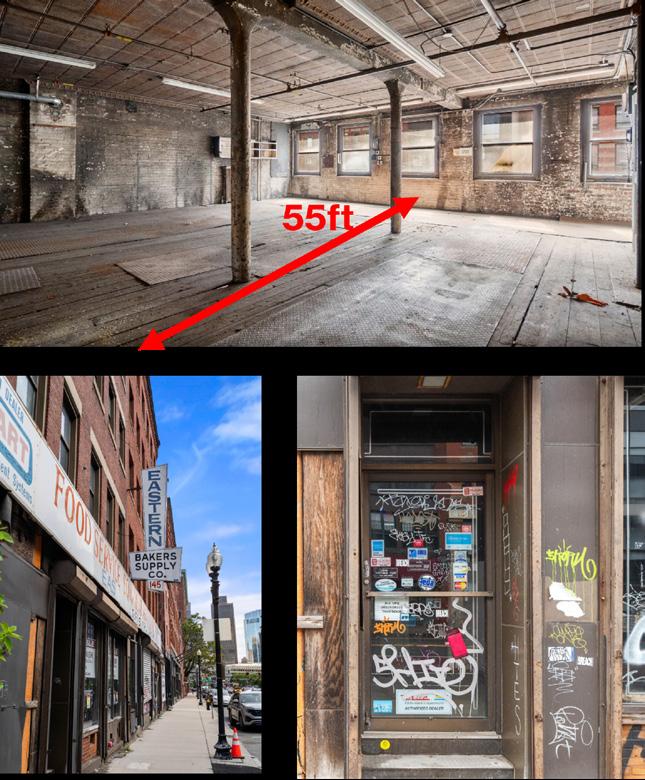

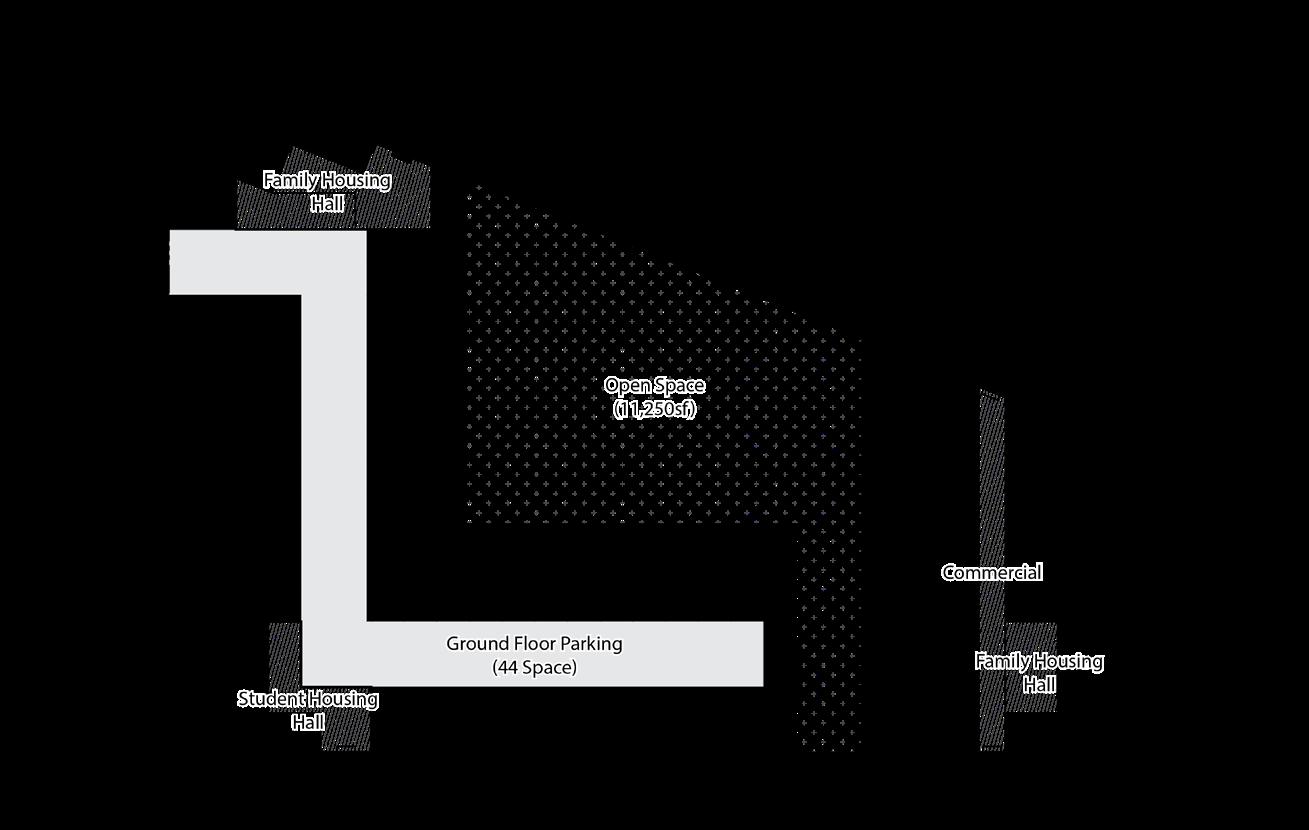

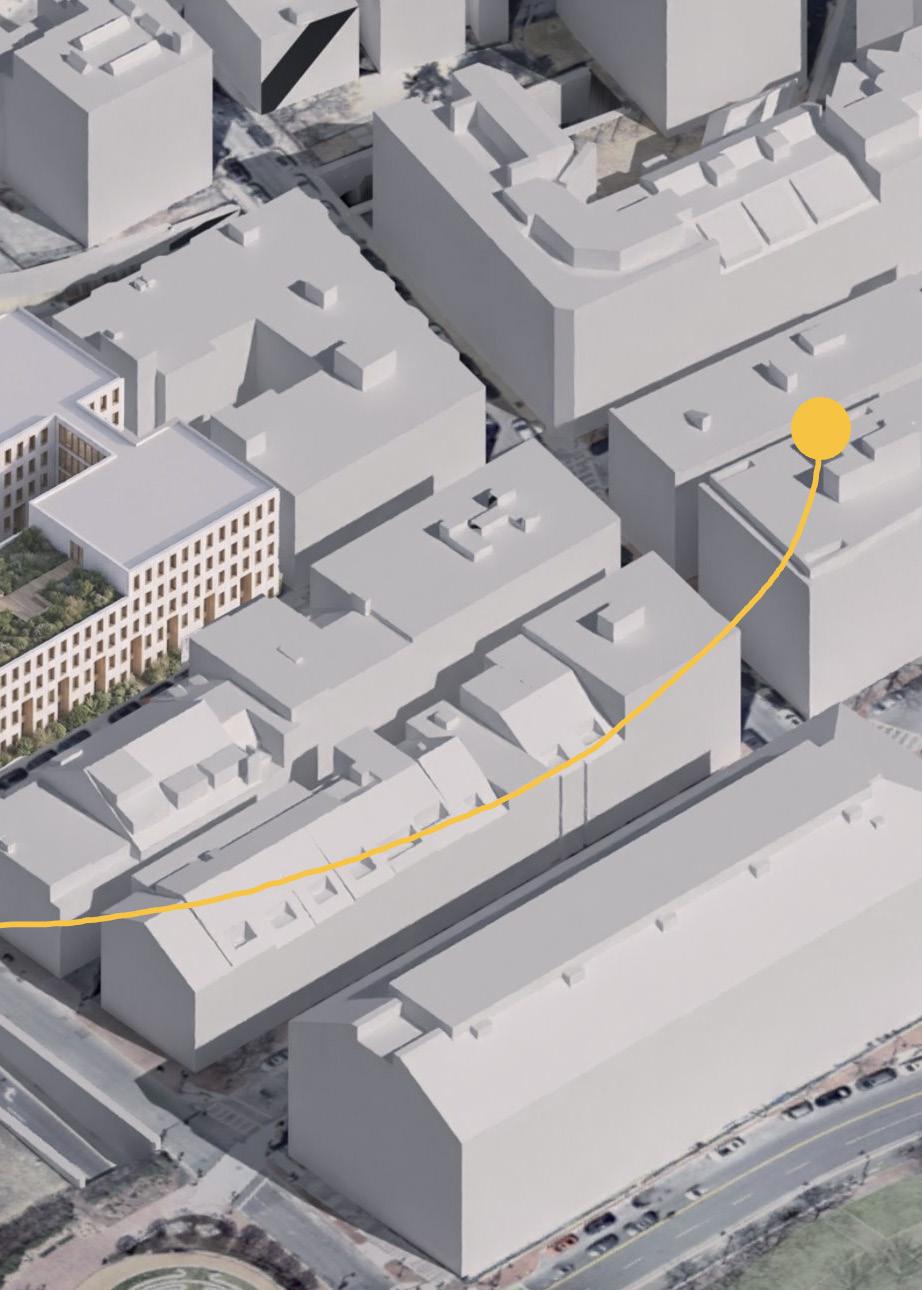

Proposed Development Plan

To establish a development strategy grounded in realistic site conditions, we

reviewed comparable listings along North Washington Street and combined this with our own field measurements. Nearby properties at 169 N Washington St and 153–155 N Washington St are currently listed for $9.5 million, while 145–147 N Washington St is offered at $1.8 million. Because the broker was unable to provide floor plans or detailed building documentation for our subject property, we conducted an on-site survey and produced our own area estimates. Based on this assessment, we estimate the existing building to contain approximately 28,335 GSF.

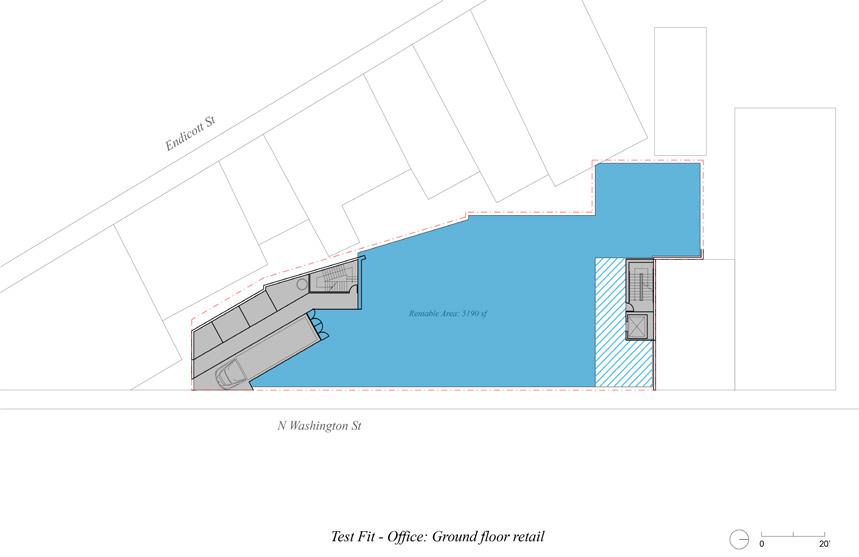

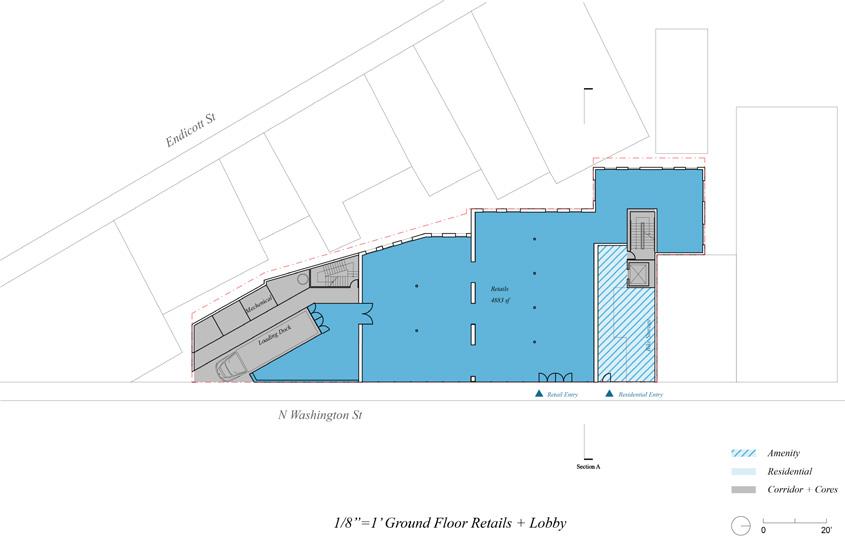

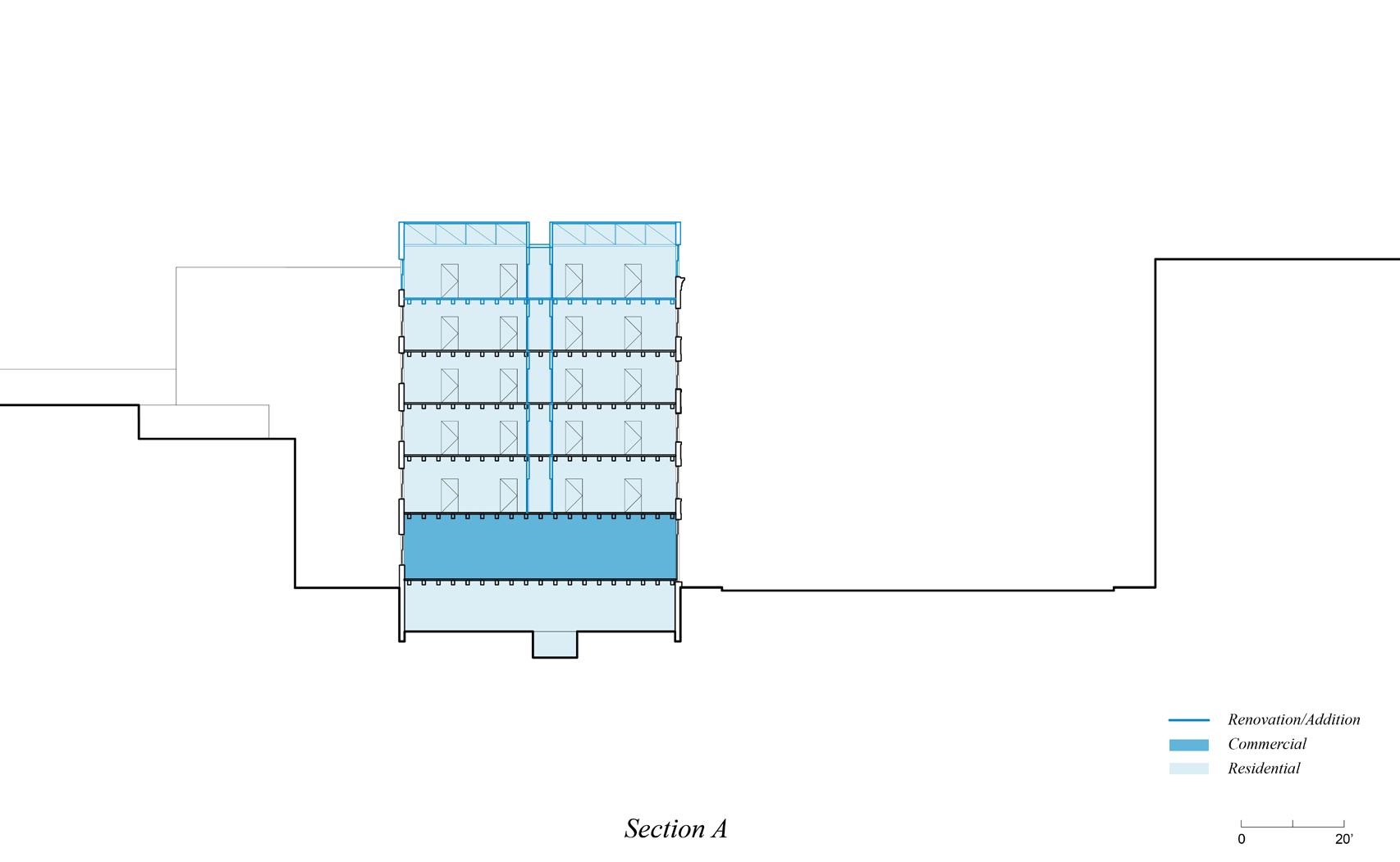

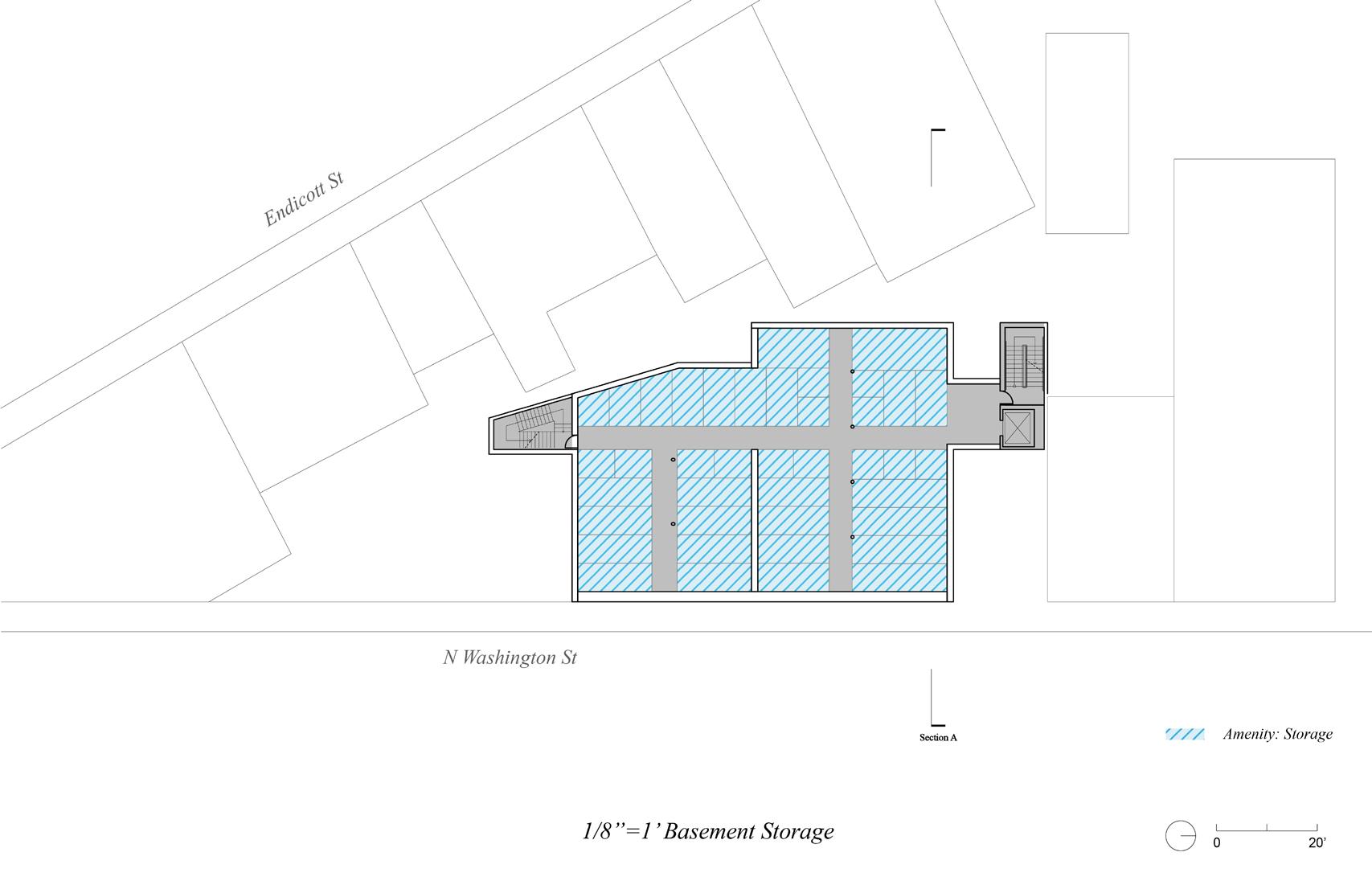

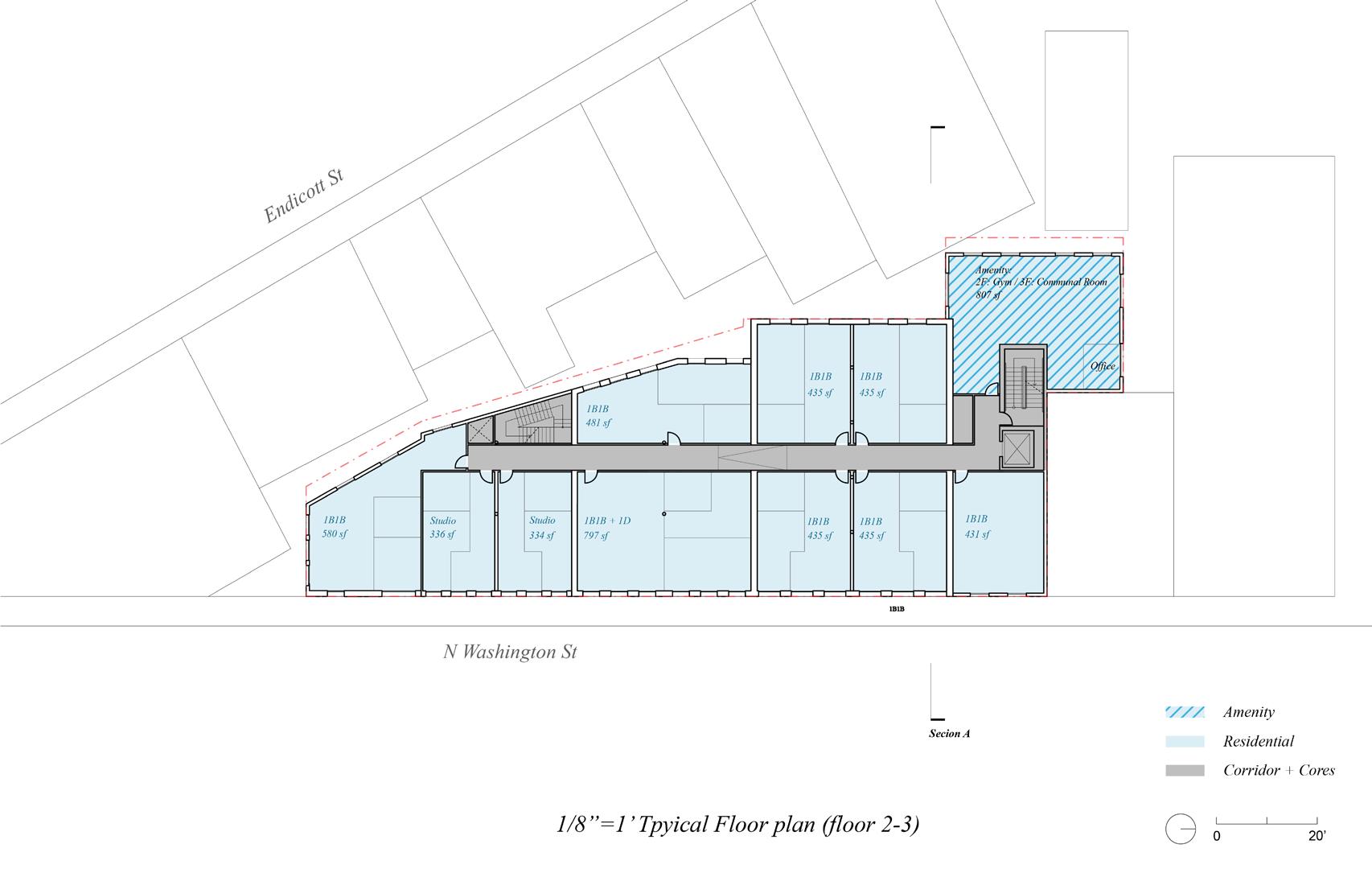

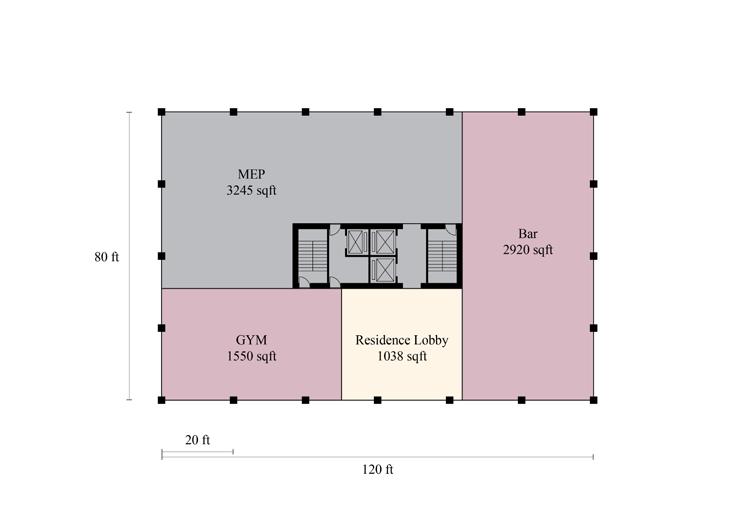

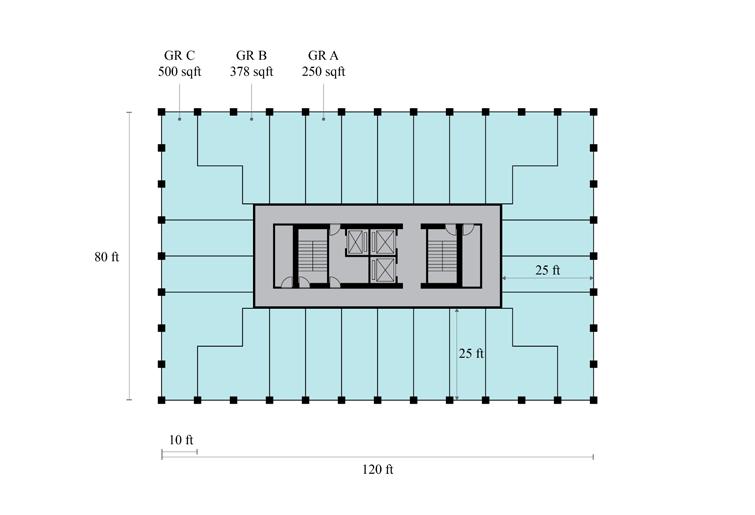

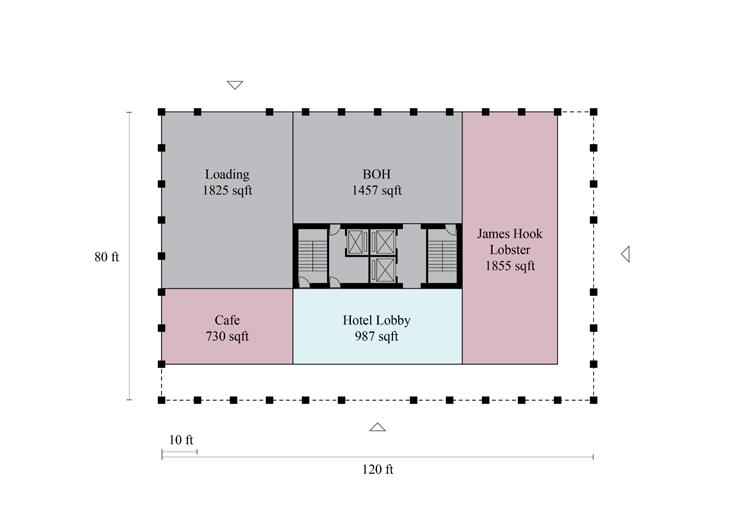

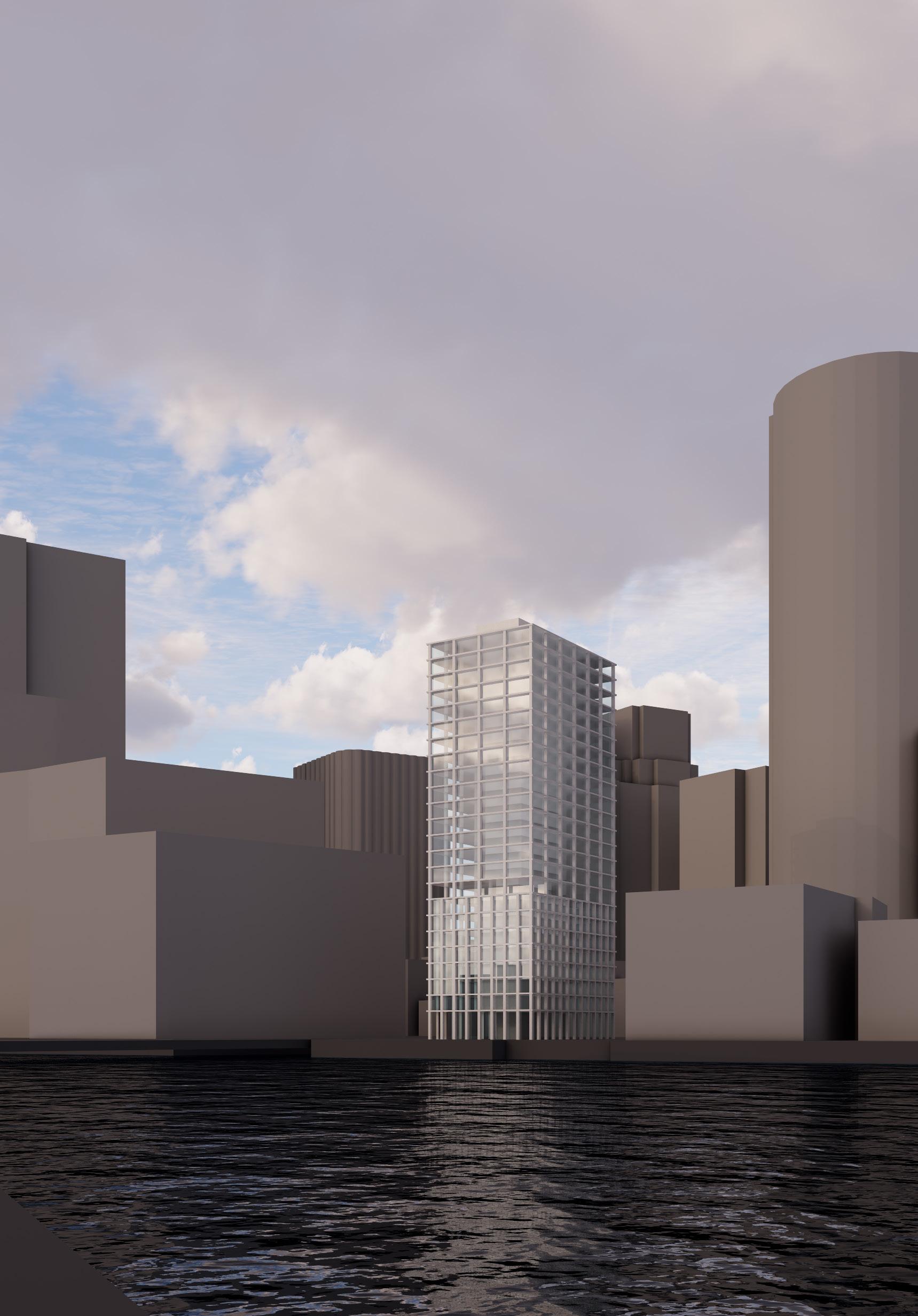

For the purposes of this proposal, we assume the demolition of the two adjacent structures at 169 N Washington St and 145–147 N Washington St, allowing the three parcels to be consolidated into a single redevelopment footprint. Under this scenario, we propose a new six-story mixed-use building that maintains ground-floor retail while introducing 53 residential units on floors two through six. The basement level would accommodate 53 dedicated storage units, providing residents with added utility while generating ancillary income for the project.

Following the consolidation of the parcels and the new massing configuration, the total building area increases meaningfully. The redevelopment would yield 42,915 GSF, representing an estimated 51.5% increase from

Programming

The proposed program results in a total of 54 units, combining 53 residential, 1 retail, and storage spaces that align with both market demand and the physical constraints of the site. The unit mix prioritizes smaller, efficiently planned one-bedroom units, which are wellsuited to North Station’s renter demographic and the narrow footprint of the building.

The residential component consists primarily of 1-bedroom units, including eight 1B+Den apartments averaging 801 SF, and thirty-four standard 1-bedroom units averaging 462 SF. Together, these units comprise the majority of the rentable residential area and are projected to generate approximately $136,000 in annual rent. To satisfy the City of Boston’s affordability requirements while protecting the project’s long-term financial performance, we designated the smallest unit types—ten studio units averaging 335 SF and one 431 SF

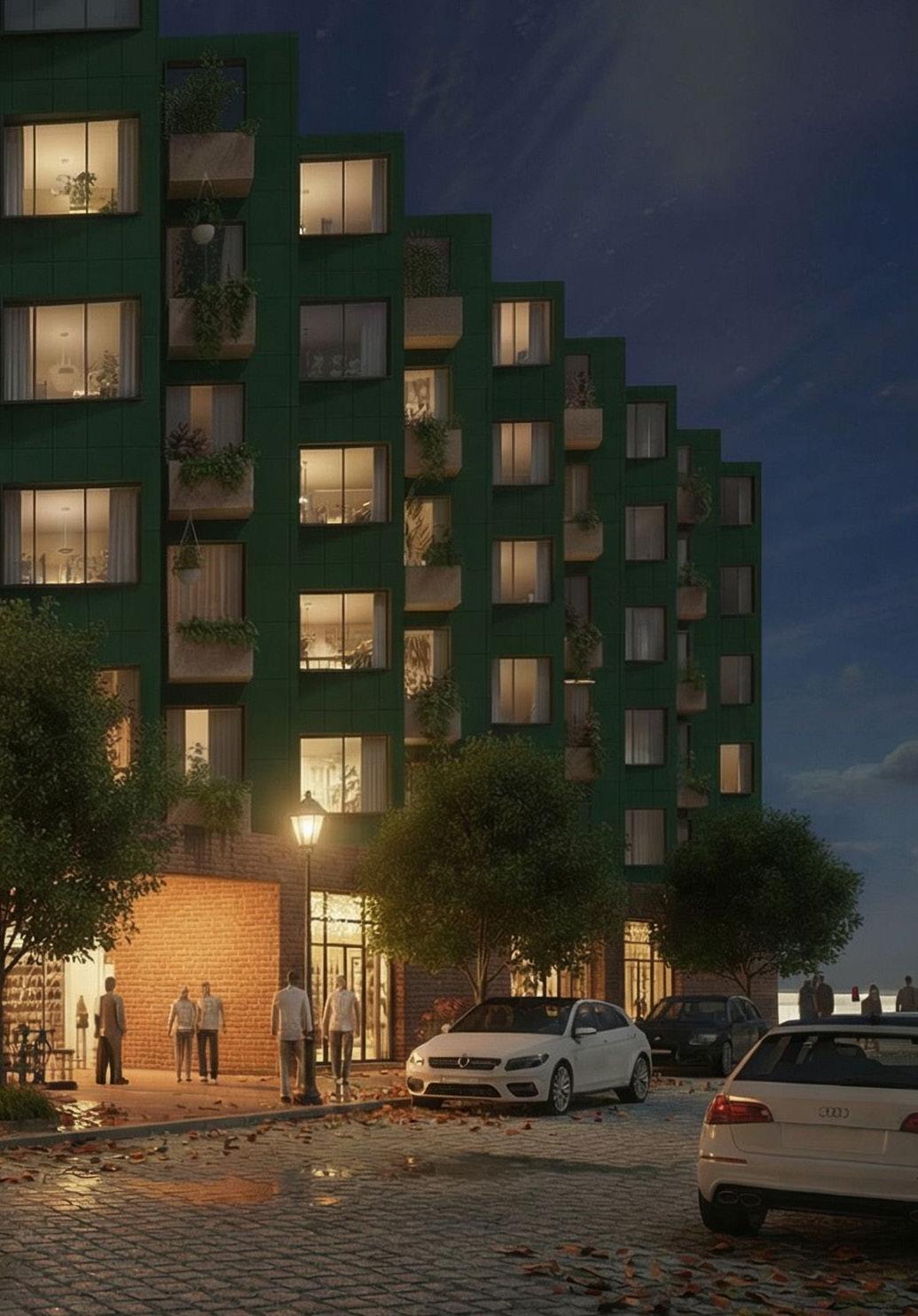

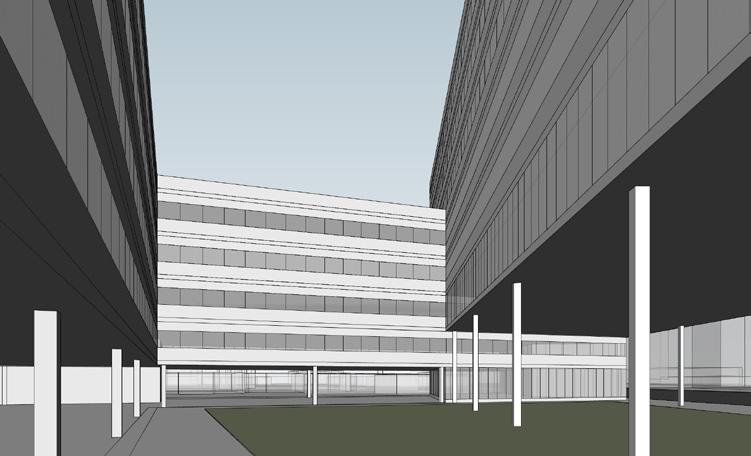

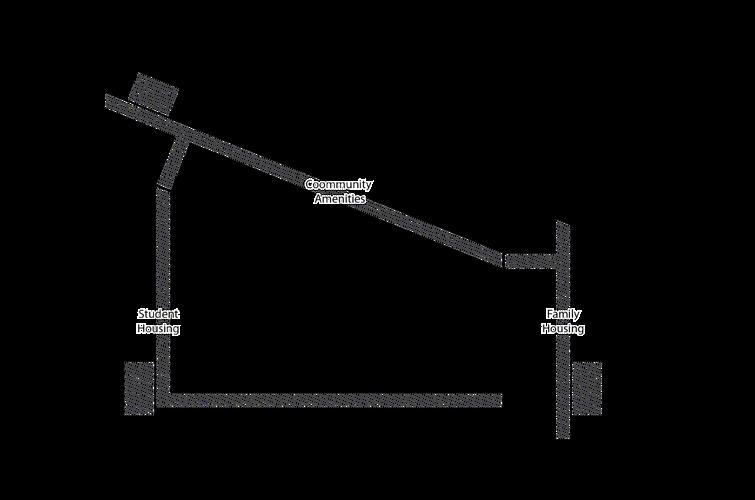

Renderings

1-bedroom—as the affordable set-aside. By allocating affordability to the lowest-SF unit categories, the project minimizes rental income loss while still meeting the 20% inclusionary requirement. These 11 affordable units collectively contribute approximately $19,000 in annual revenue and help strengthen the entitlement pathway for the conversion.

Ground-floor retail is preserved in the program, maintaining 4,882 SF of commercial space that contributes an estimated $18,000 in annual rent. This retail presence not only activates the street edge but also supports the mixed-use character encouraged in the immediate neighborhood context. In the basement, residents are provided with 53 dedicated storage units, totaling 2,703 SF. Although modest in size, these storage units contribute meaningful ancillary revenue, producing roughly $47,700 annually, and enhance the competitiveness of the residential offering by addressing a common storage shortage in dense urban multifamily buildings. In total, the program delivers 33,521 SF of residential and income-generating areas, with an average residential unit size of approximately 696 SF and total projected annual revenue of $178,119 across all components. This balanced mix of unit types, affordability, and ancillary spaces supports both financial

feasibility and alignment with Boston’s broader housing objectives. In addition to the residential and retail components, the program incorporates amenity spaces on the second and third floors, which were intentionally reserved for non-residential use. These levels receive limited natural light and are positioned directly against an adjacent building at the rear, conditions that would make them less desirable for residential units from both a leasing and livability standpoint. Instead, we programmed these floors with a community room and a fitness center, amenities that add value for residents without relying heavily on direct sunlight or exterior exposure. This approach optimizes the building’s spatial efficiency by placing residential units on the higher, better-lit floors, while ensuring that the portions of the structure with constrained daylight still contribute meaningfully to the overall tenant experience.

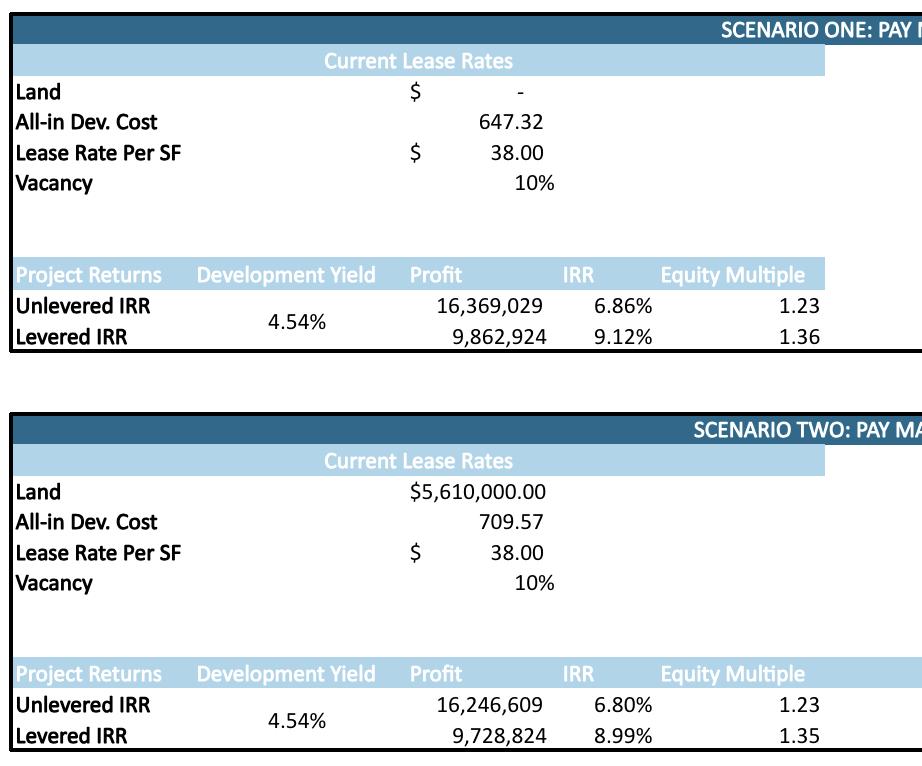

Profitability Analysis