Malkit Shoshan

Malkit Shoshan

Colophon

Course Instructor

Malkit Shoshan

Teaching Assistant

Spurty Kamath

Students

Xavier Ayub, Jules Bernstein, Kaitlyn Bell, Yana Buchatska, Mauricio Cohen Kalb, Luis Arturo Gomez, Spurty Kamath, Richard Kowel, Zebeeb Nuguse, Izzy Tice, Savalee Tikle, Tyler Vandenberg, Haozhuo Yang

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is extended to the external contributors who participated in lectures, workshops, and reviews, and generously shared data with us: UNPBF: Diane Myriam

A Sheinberg UN Habitat: Mathias Spaliviero; UNHCR: Rakesh Gupta Nuchanametla Ramasubbaiah, Abdulaye Sy, Vasiliki Tsioutsiou; and IOM: Luísa Freitas

We also acknowledge the support of the 2025 Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative (HMUI) Urban Research Grant, which made this work possible.

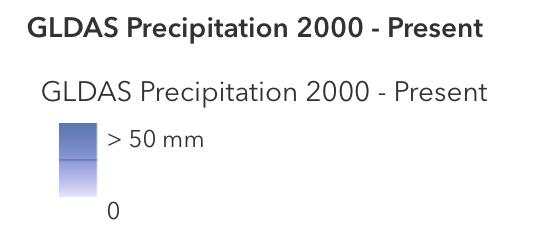

StoryMap

This course review is supported by a Story Map with three sections: 1) Water, Landscape, and Agriculture in Arid Climates; 2) Infrastructure Recommendations for Mauritania; 3) Architectural Case Studies in Arid Climates, featuring student-collected case studies, design references, and additional reccomendations. Link: https://arcg.is/04C49q1

Course Summary / Malkit Shoshan

This project-based seminar examined migration induced by climate and conflict, which often intersected, in one of the most volatile hotspots in the world, the Sahel. The Sahel region had been grappling with the root causes and the multidimensional consequences of climate change for a long time; colonization, extensive resource extraction, conflict, and militarization. In the region, new trends in migration were observed, and local, national, and international policies and protocols for humanitarian contingency planning were developed in response.

In the Sahel, traditional lifestyles such as nomadic pastoralism and transhumance thrived for millennia in extreme weather conditions, offering valuable lessons in adaptability and perseverance in times of crisis and resource scarcity. Given this context, the seminar explored the following questions:

• What can we learn about the future of climate migration from these migration trends and rich local cultures, and how can they intersect with international interventions?

• How can we use multi-temporal and multi-scalar spatial analysis and climate vulnerability projections to understand a future planet in a constant state of flux–one in which the constraints of national territories are perhaps transcended–while embracing a deeper cultural preservation of lifestyles, construction techniques, materiality, habitat typologies?

• How can we forge relationships with broader ecological and environmental conditions defined by commons and collective resource management?

• What can these insights teach us about architecture and urban planning, and how can we use them to challenge our own discipline, pedagogy, and relationship with spatial production?

During the seminar, the class engaged with diverse stakeholders and viewpoints from theory and practice, including conversations with representatives of United Nations agencies such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which possess real-time data and field experience. Drawing on their datasets and engaging in dialogue with local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community representatives, we developed a case study focused on climate migration in the Sahel, with particular attention to the situation in Mauritania, where local and international organizations work together to support the country’s open-door policy and its efforts to host refugees from the region and prevent them from reaching Europe.

Sessions included meetings with diverse stakeholders, interactions with UN agencies, NGOs, and local community representatives, as well as in-class workshops for project development that incorporated spatial analyses of migration trends and scenario exercises.

Zebeeb Nuguse and Haozhuo Yang

Livestocks and Health Facilities in Sahel Richard Kowel

Essential Resources: Water, Food and Soil

Haozhuo Yang

Food Insecurity, Malnutrition and Lack of Access to Healthcare Richard Kowel

Zebeeb Nuguse

Zebeeb Nuguse and Richard Kowel

Hydrogeological Dynamics in Hodh Ech Chargui Region

Zebeeb Nuguse

Yana Buchatska

Savalee

111 IV. Design and Planning Recommendations

113 Violence and Instability in the Sahel

Tyler Vandenberg

115 Climate Action and Resilience

Tyler Vandenberg

117 Spatial and Environmental Vulnerabilities

Savalee Tikle

119 Camp Materials

Yana Buchatska

121 Stengthening Primary Health Facilities in Sahel

Richard Kowel

123 Sustainable Refugee Support and Economic Growth

Spurty Kamath

125 Dry Toilets and Soil Stabilization for Roads and Paths

Mauricio Cohan Kalb

127 MICP and Composting Loop

Mauricio Cohan Kalb

129 Camp Access and Integration

Kaitlyn Bell

133 Cooling and Shading

Yana Buchatska

135 Bibliography

Climate change presents an urgent global challenge with far-reaching implications for human societies and all other species inhabiting the planet. Over the next few decades, extreme climate zones and uninhabitable areas are projected to expand, driven by factors such as water stress, food insecurity, extreme heat, sea level rise, and weather-related disasters such as storms and wildfires. These challenges are already driving instability and increasing displacement, forcing individuals and communities to leave behind the spaces and cultures they have inhabited for generations.

As of 2024, an estimated 120 million people are displaced (UNHCR), with projections suggesting this number may rise significantly, disproportionately impacting individuals and communities historically the least responsible for the climate crisis.

The Sahel region has been grappling with the root causes and the multidimensional consequences of climate change for a long time; colonization, extensive resource extraction, conflict, and militarization. Traditional lifestyles such as nomadic pastoralism and transhumance have thrived for millennia in extreme weather conditions, offering valuable lessons in adaptability and perseverance in times of crisis and resource scarcity. In the region, new trends in migration are observed, and local, national, and international policies and protocols for humanitarian contingency planning are currently being developed in response.

In this atlas, the class analyzed environmental and conflict threats across scales and time. The analysis focuses on climate migration in the Sahel, with particular attention to the situation in Mauritania, where local and international organizations are working together to support the country’s open-door policy and its efforts to host refugees from the region. With all of this in context, there is a specific focus on M’bera Camp to assess the viability of the space and how to imagine a way forward noting specific spatial, geopolitical, and financial limitations.

Africa features a diverse range of climate regions, including hot deserts, semi-arid zones, tropical wet and dry areas, equatorial rainforests, Mediterranean climates along the northern and southern fringes, humid subtropical marine regions, warm temperate uplands, and mountainous zones, with most of the continent characterized by warm to hot temperatures and rainfall patterns that vary widely by region.

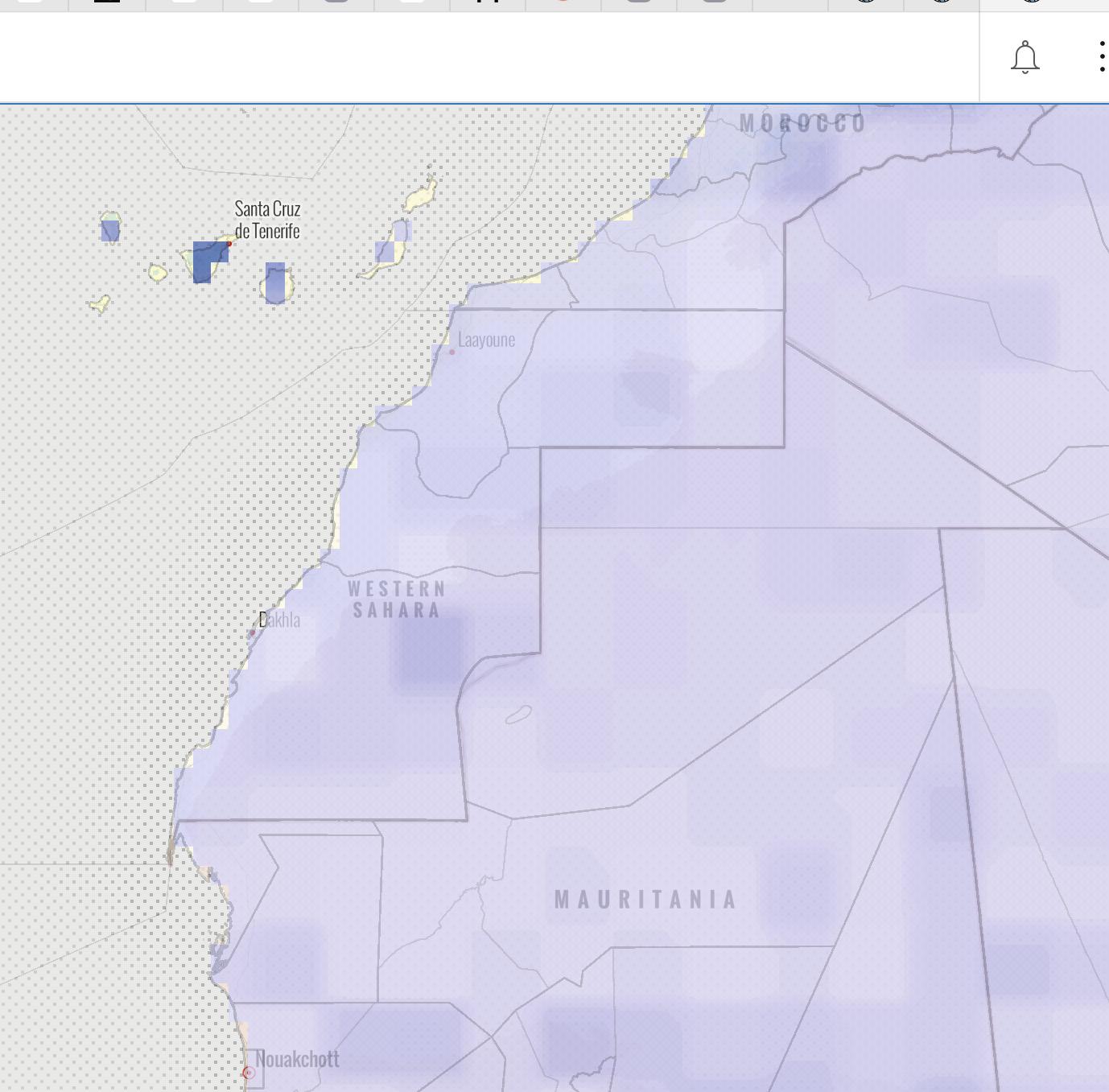

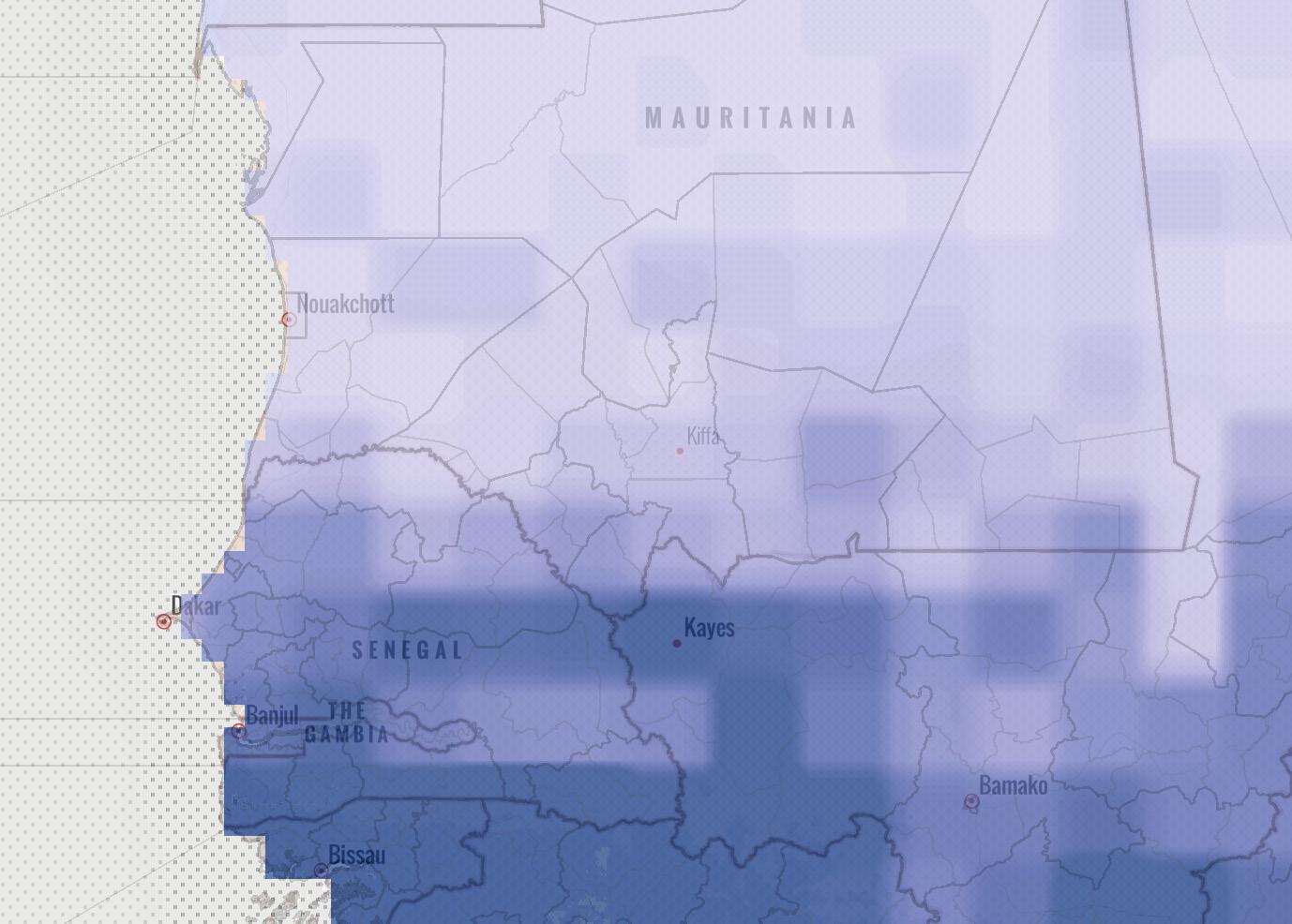

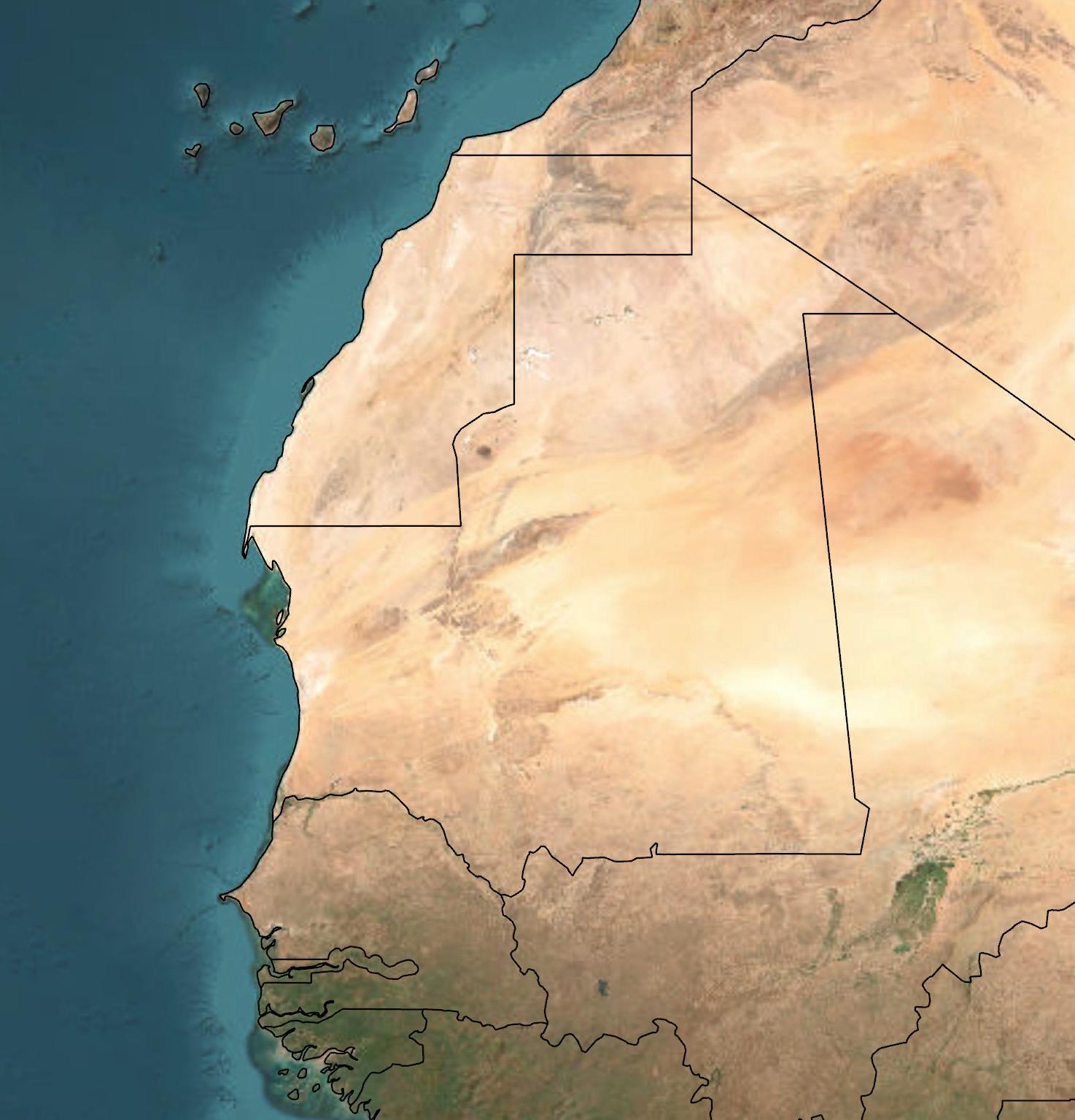

Mauritania features several climate regions: the Saharan zone in the north with extremely hot, dry conditions; a central Sahelian zone with semi-arid climate and some seasonal rainfall; a southern Sudanese zone with higher rainfall and more vegetation; and a coastal maritime zone with cooler, humid conditions.

As of 2025, Mauritania’s population is about 5.3 million, primarily composed of Bidhan (white Moors), Haratin (black Moors), and West African ethnic groups, while the country also hosts approximately 257,000 refugees and asylum-seekers, mainly from neighboring countries.

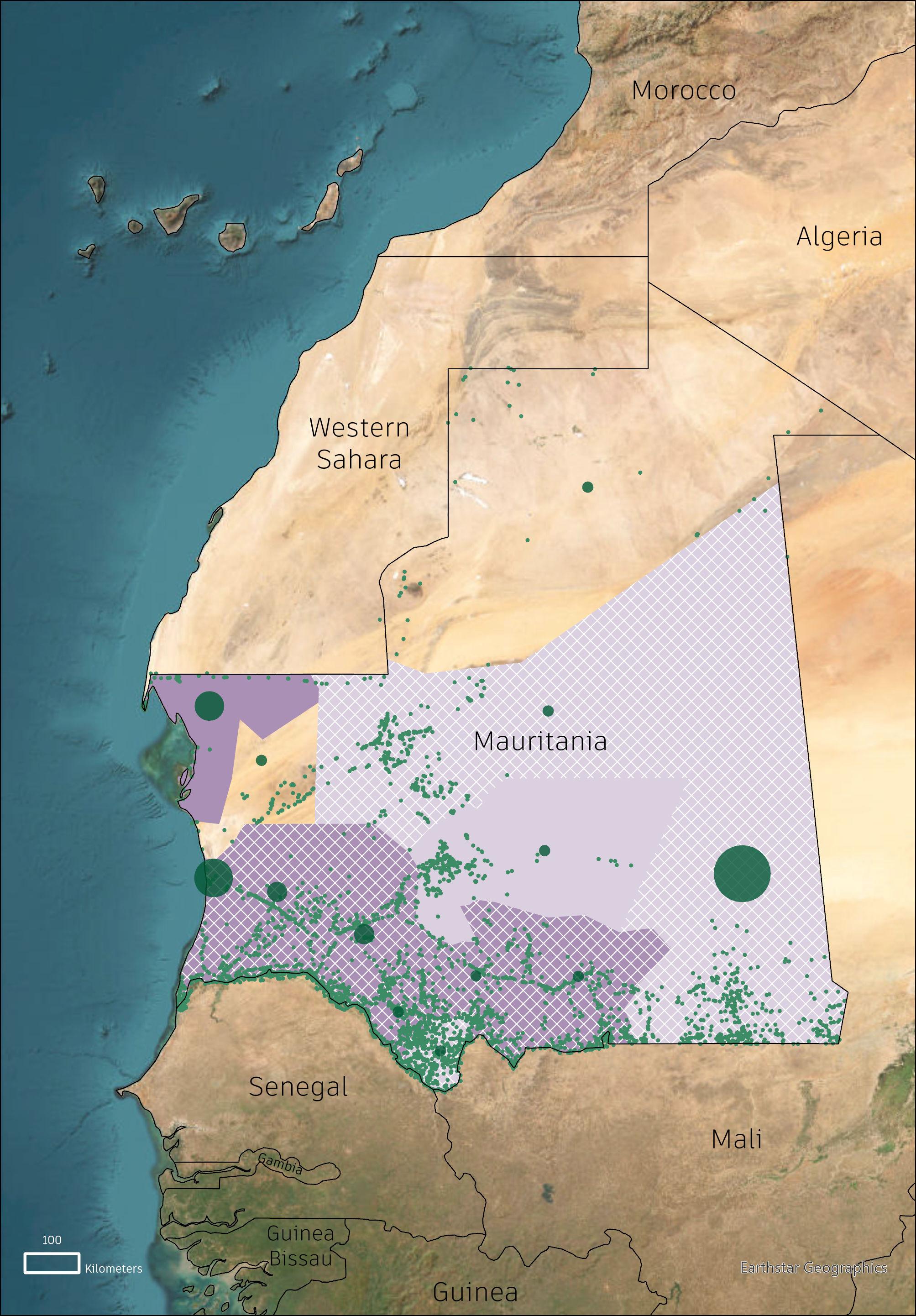

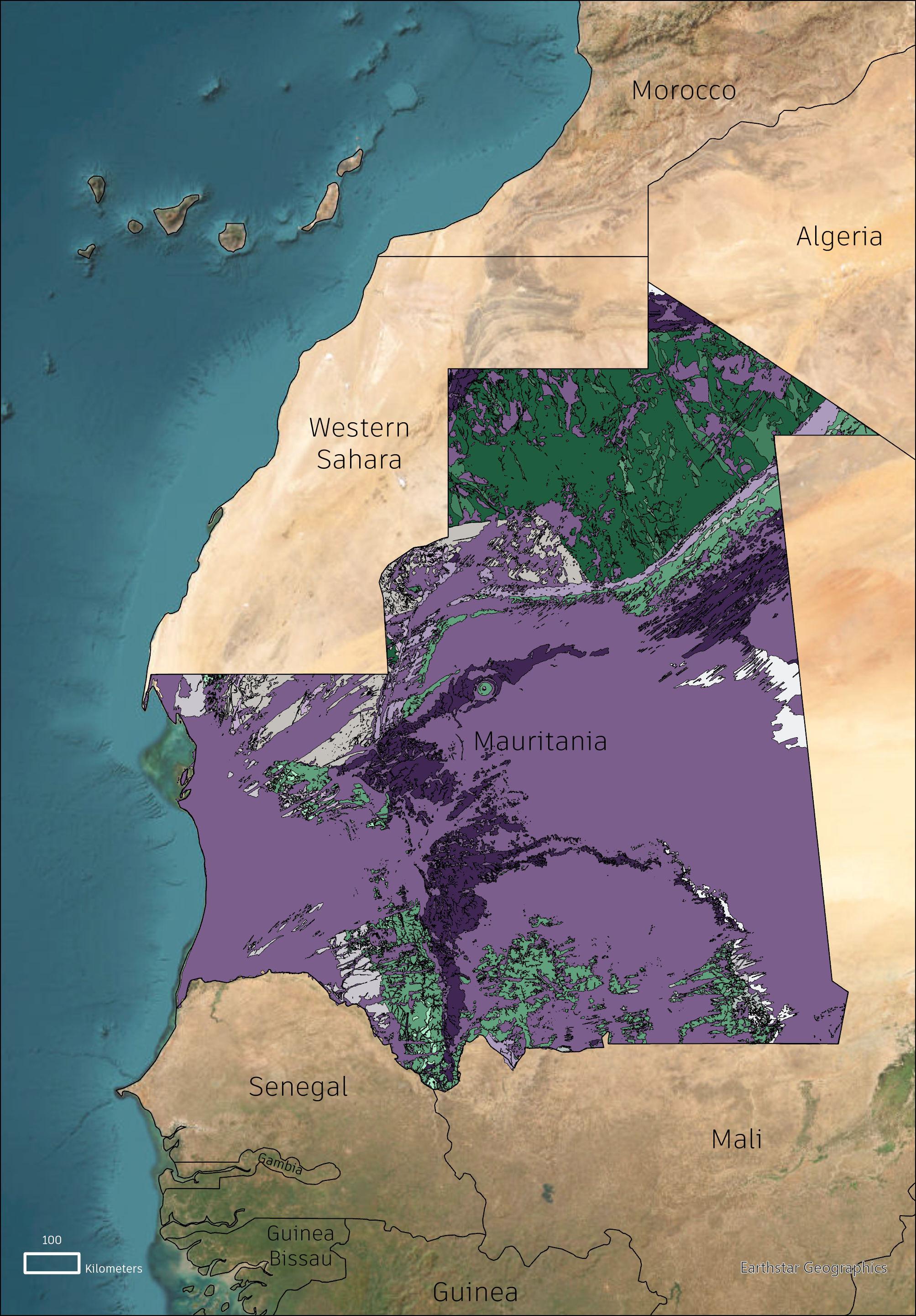

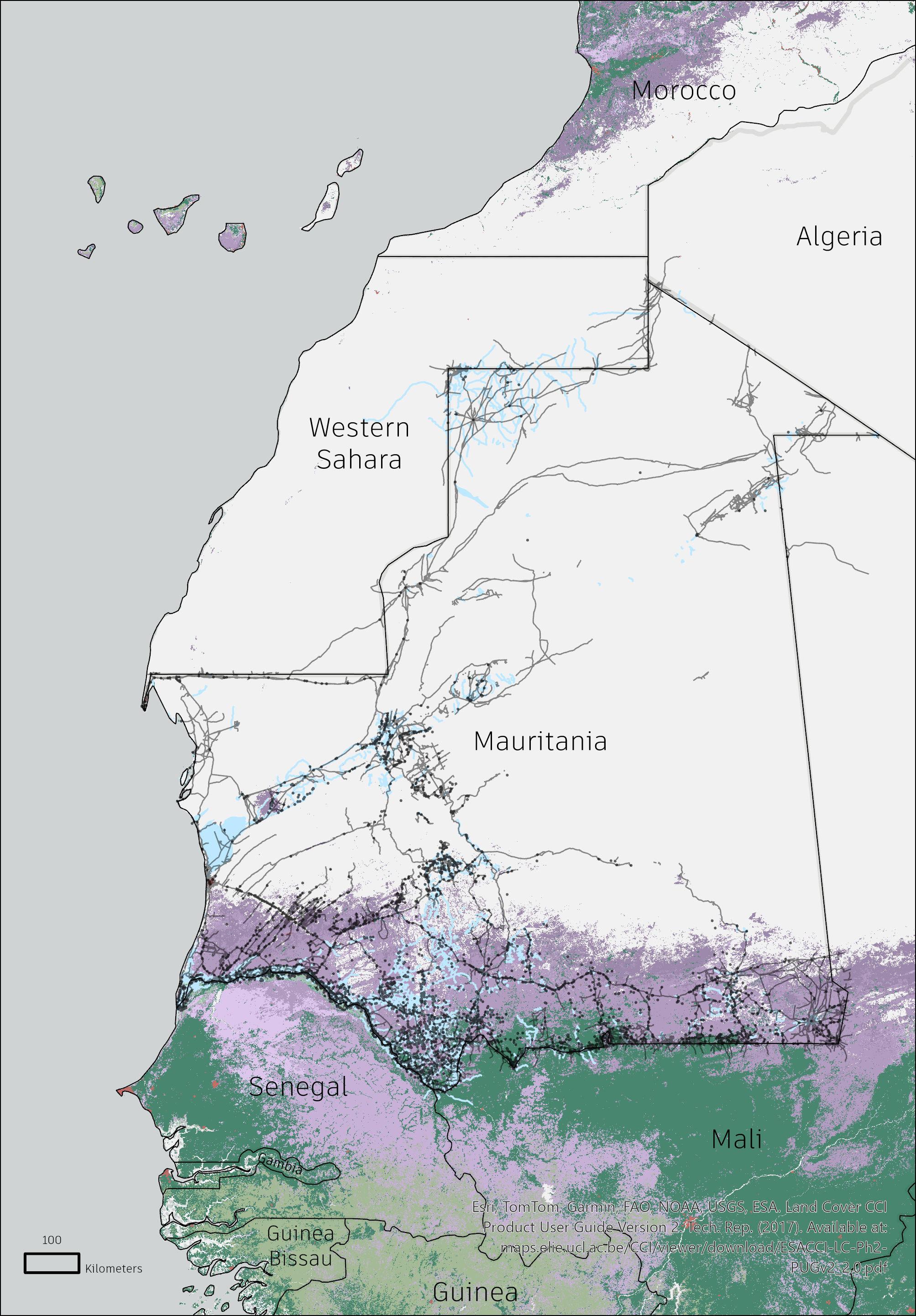

The demographic trends in Mauritania directly correlate with significant land cover transformations observed through satellite data. As the population grew from 2 million in 1990 to approximately 5 million by 2024, land use patterns underwent dramatic changes, particularly in the fertile southwest region along the Senegal River.

The most striking correlation is between urbanization and land cover change. Urban areas expanded by 200-300% over 30 years in coastal cities, directly reflecting the rural-to-urban migration driven by desertification and drought mentioned earlier. Nouakchott’s explosive growth from 5,250 people in 1960 to 1.26 million by 2019 corresponds with a 14.65% increase in built-up areas between 1984-2022.

Agricultural expansion shows the strongest correlation with population pressure. Despite Mauritania being 90% desert, agricultural land increased by 221% from 1984-2022, concentrated in the Senegal River Valley where most of the population resides on just one-fifth of the country’s land. This agricultural intensification reflects the need to feed a rapidly growing, young population.

The 68.58% decrease in barren land and 118.46% increase in water bodies correlate with infrastructure development, including the Diama Dam construction, which supported both urban growth and agricultural expansion. However, with 61.3% of the population now urban and continuing demographic pressure, land cover changes are accelerating, creating competition for habitable and arable land in this predominantly desert nation.

Landcover and Population

Rainfed Cropland

Tree or Shrub Cropland

Irrigated or Post-Flooding Shrubland

Mostly Natural Vegetation in a Mosaic with Cropland

Shrubland

Sparse Vegetation

Flooded Shrub / Herbaceous Covers

Bare Areas

Populated Places

Xavier Ayub

Spurty Kamath

Tyler Vandenberg

Savalee Tikle

Kaitlyn Bell

Izzy Tice

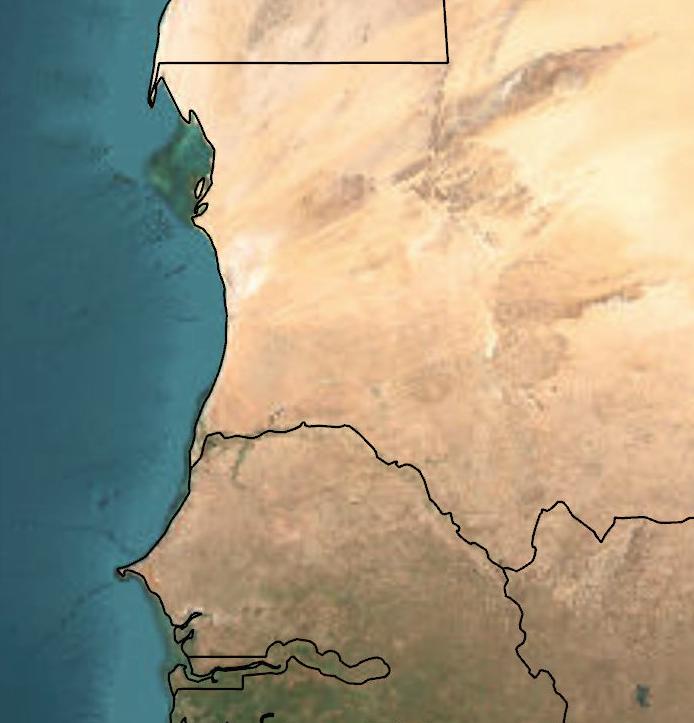

Mauritania in the present day finds itself at the nexus of several globe-spanning trends, where their impacts overlap and gradually change the fabric of the region. The Sahel, one of the great global thoroughfares of trade and travel for centuries, increasingly finds those networks under strain imposed by the conditions of climate change. In Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, those environmental stressors now overlap with the political and cultural legacies of the colonial period, the Cold War, and the post-1991 global economic order. Migration flows driven first by populations seeking work and then augmented by social unrest and violence after 2011 have spread in all directions, some making the long trek to Europe, some seeking instead to move across the most proximate border for safety. Stresses on resources – governmental, social, and economic – have resulted, even as outside interest in the region’s rich resources has steadily grown.

Adding to this tapestry of population movement is the traditional institution of transhumance herding, in which livestock are driven across borders and regions to reach seasonal patches of lush grazing territories. Clashes between these semi-nomadic herding groups and the increasingly settled national populations are an endemic example of social friction in the Sahel. These herders and many others make frequent movements across territories controlled by non-state actors. These latter groups often engaged in conflict with the recognized national governments of the Sahel states. The spiraling feedback cycle of scarcity, disruption, and violence burdens the governments and non-governmental organizations of the region, providing some of the most potent examples of climate change-driven instability in the world today.

The coast of Mauritania’s northern port city of Nouadhibou, seen from the air, June 22, 2022. From Mauritania, West and Central African migrants seeking to reach Spain’s Canary Islands often depart in small boats from in or near Nouadhibou or the capital, Nouakchott. © 2022 Lauren Seibert/Human Rights Watch

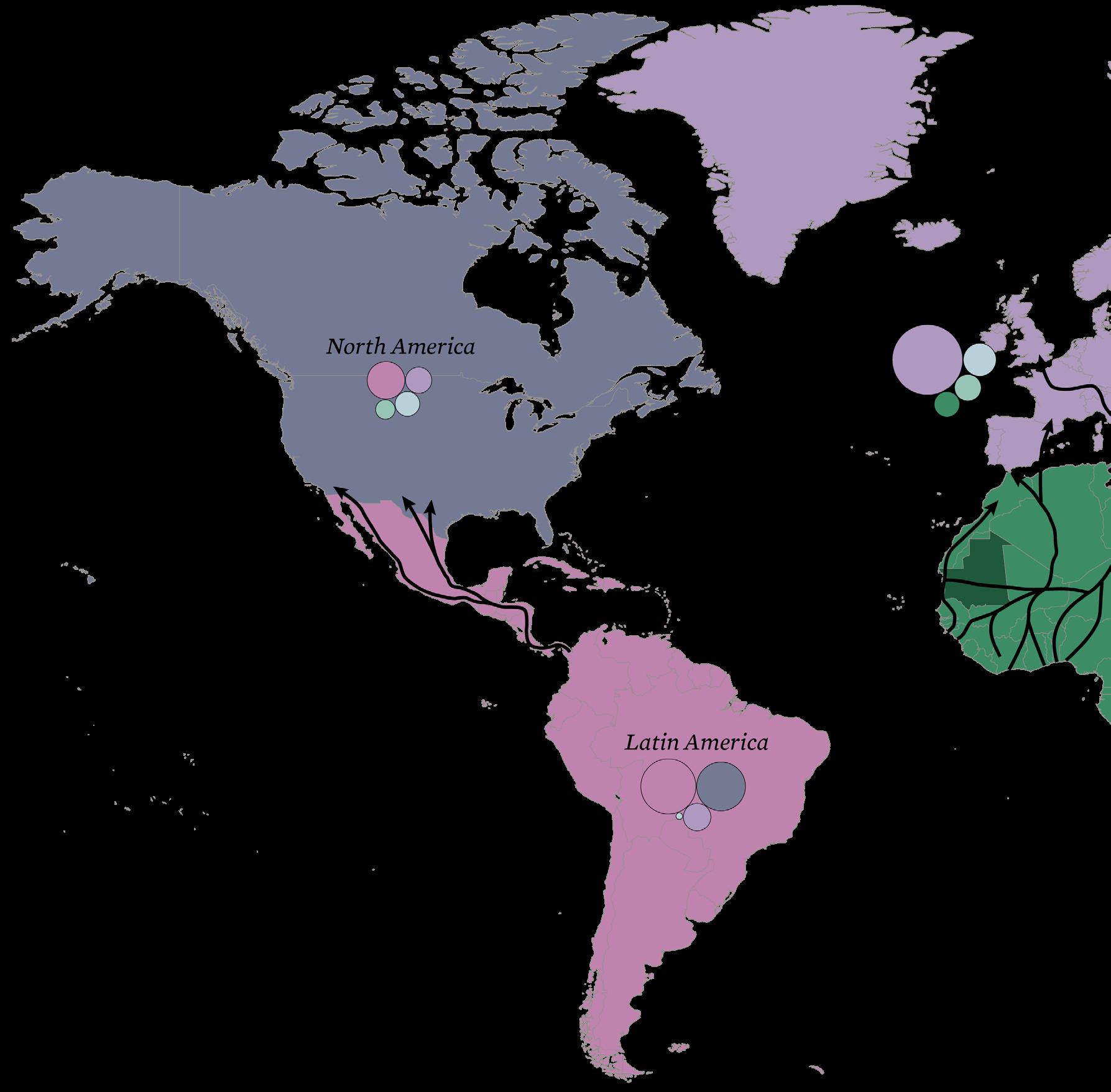

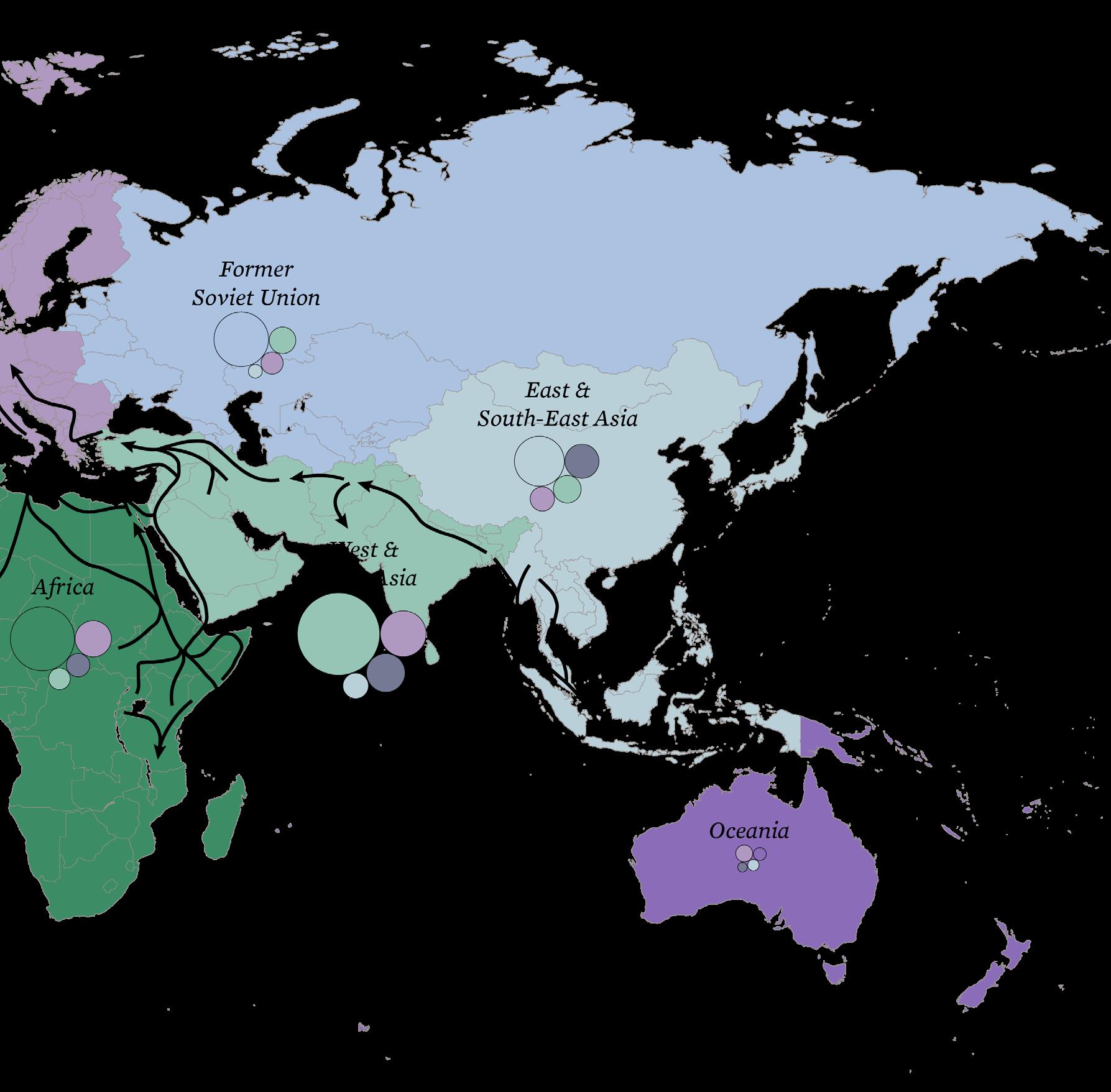

Over the past two decades, Western governments have increasingly adopted border externalization as a central migration management strategy. This approach, most prominently pursued by the European Union, seeks to shift border controls and migration responsibilities to countries that lie along major migration routes.

1,000,000

100,000 Migrants

Most movement originates in North and West Africa, crossing the Mediterranean toward Europe, or in Central America, moving toward the United States. In Asia, instability in countries such as Afghanistan, Syria, and Myanmar continues to drive large-scale displacement to neighboring states. Within Africa, however, most migration remains regional, driven by proximity and shared pressures.

Mauritania faces significant migration issues, primarily driven by economic hardship, desertification, and political instability, which compel many to seek better opportunities elsewhere. The country is both a source and a transit point for migrants, often risking dangerous journeys across the Sahara Desert. In response to these challenges, Mauritania has adopted an open door policy aimed at attracting international assistance and fostering regional cooperation to manage migration flows. This policy emphasizes humanitarian support, legal migration pathways, and efforts to combat human trafficking and smuggling. However, managing migration sustainably remains complex, requiring coordinated efforts to address root causes and ensure the protection of migrants’ rights.

Rainfed Cropland

Tree or Shrub Cropland

Populated Places Landcover and Population

Irrigated or Post-Flooding Shrubland

Mostly Natural Vegetation in a Mosaic with Cropland

Shrubland

Sparse Vegetation

Flooded Shrub / Herbaceous Covers

Bare Areas

4,514 - 1,2687

The roots of conflict in Mauritania since the pre-colonial period reflect the shifting relationships between land, power, and climate. Early French exploration of the region attempted to understand the land and the people through a Western lens. Attempts to label tribes and land could not capture the fluid, mobile, and negotiated nature of social and spatial organization in the Sahara. Instead, colonial cartography and legal codes imposed rigid borders and property regimes that undermined communal systems of land use and stewardship. These interventions laid the groundwork for ethnic hierarchies, environmental disruption, and enduring contestation over space. Today’s risks and conflicts cannot be separated from these roots, nor from accelerating pressures on them from rising global temperatures.

Colonization Conflict Sites (1890s-1912) Senegal Mauritania Conflict Sites (1989 - 1991) Violent Land and Resources Disputes (1960s-1990) Franco-Trarzan Conflicts (1825)

The Franco-Trarzan Conflicts marked early struggles over resource extraction and French involvement in the region, laying the groundwork for the later colonial conquest. During the colonial period, land was restructured through expropriation and administrative fragmentation, severing traditional orders of land sharing and communal ties. The French land policies favored privileged elites and marginalized pastoralists and farmers, deepening divisions that would contribute to land disputes. These tensions culminated in the Mauritania–Senegal Border War, where present day borders and grazing rights lead to widespread violence.

The legacy of colonial-era land policies and deep-rooted ethnic tensions culminated in the eruption of violence between Mauritania and Senegal between 1989 and 1992. The immediate trigger of the conflict was a dispute over land use and grazing rights along the Senegal River, exacerbated by severe environmental stress and resource scarcity. The conflict quickly escalated into broader ethnic violence, with Moorish groups in Mauritania and black African populations in Senegal both engaging in expulsions, killings, and destruction of communities. The governments responded by transferring out populations “at risk”, resulting in the exiling of tens of thousands of black Mauritanians.

Political action locally and transnationally should consider these historical grievances, the legacy and ongoing issue of slavery, and consider the traumas these events have had on the populations at hand.

Mauritania has become a key transit point along the West African migration route to Europe, particularly for those trying to reach the Canary Islands. Since 2006, migration through this corridor has increased, often via dangerous Atlantic crossings in small boats. While some Mauritanians migrate, most are from other West and Central African countries.

Regional instability—especially insurgency in Mali that spread to Burkina Faso and Niger—has driven these flows, exacerbated by frequent droughts. Though Mauritania has largely avoided direct violence, cross-border displacement is common. European military and aid missions have failed to curb the crisis, most ending after 2023 due to waning EU interest.

In 2024, Mauritania and the European Union signed a €210 million agreement aimed at curbing irregular migration through West Africa, particularly along the route to Spain’s Canary Islands. The deal represents a strategic partnership in which Mauritania acts as a buffer state, helping to police Europe’s external borders far from the continent itself.

The funding is structured into multiple packages, including support for border enforcement, institutional capacity building, and development assistance. This includes surveillance equipment, maritime patrols, and support for detention centers—some of which have been criticized by human rights organizations for poor conditions and lack of due process for detainees.

While the agreement has boosted resources for Mauritania and NGOs operating to stabilize migration flows by reducing boat departures and increasing migrant apprehensions—longterm success remains doubtful. Most migrants passing through Mauritania are not Mauritanian, but are from countries like Mali, Guinea, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire, driven by conflict, climate stress, and economic precarity. Without broader legal pathways for migration and expanded refugee resettlement opportunities in Europe, these flows are likely to continue.

Critics warn that such deals risk outsourcing migration control to countries with limited capacity and inconsistent human rights protections, mirroring controversial EU agreements with Libya and Tunisia. Moreover, the focus on enforcement may overshadow much-needed investment in regional stability and livelihoods—key to addressing the root causes of displacement.

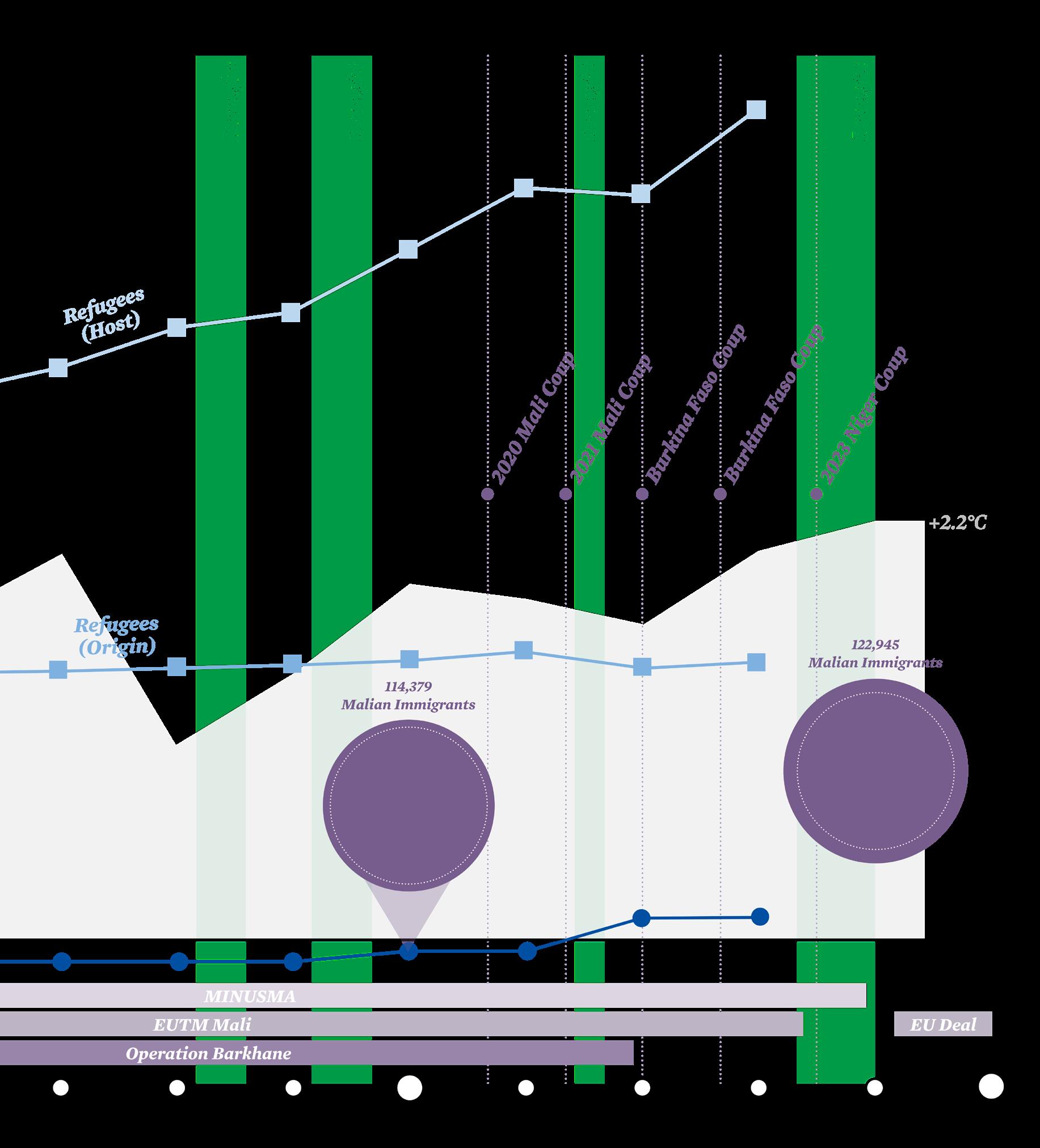

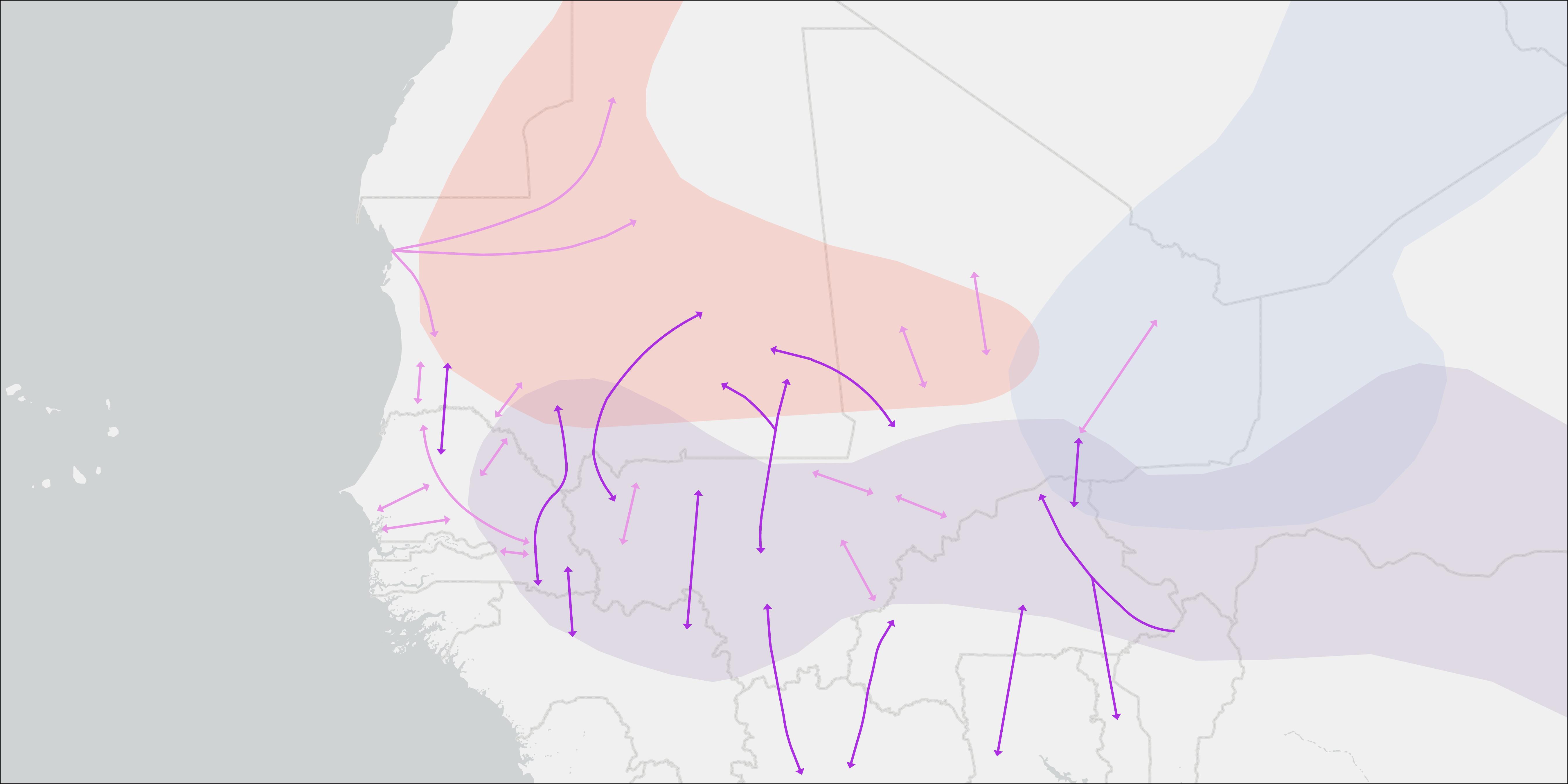

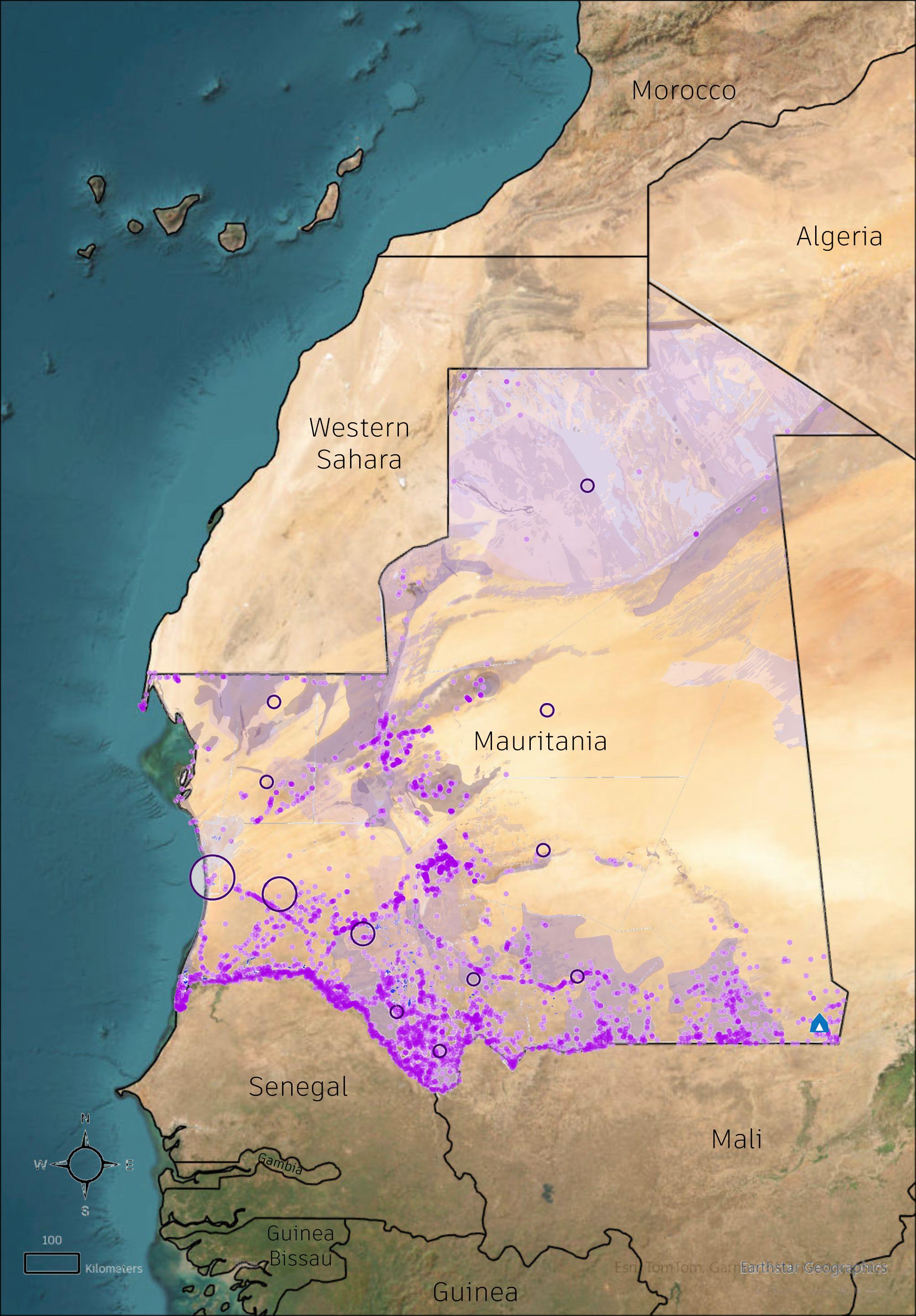

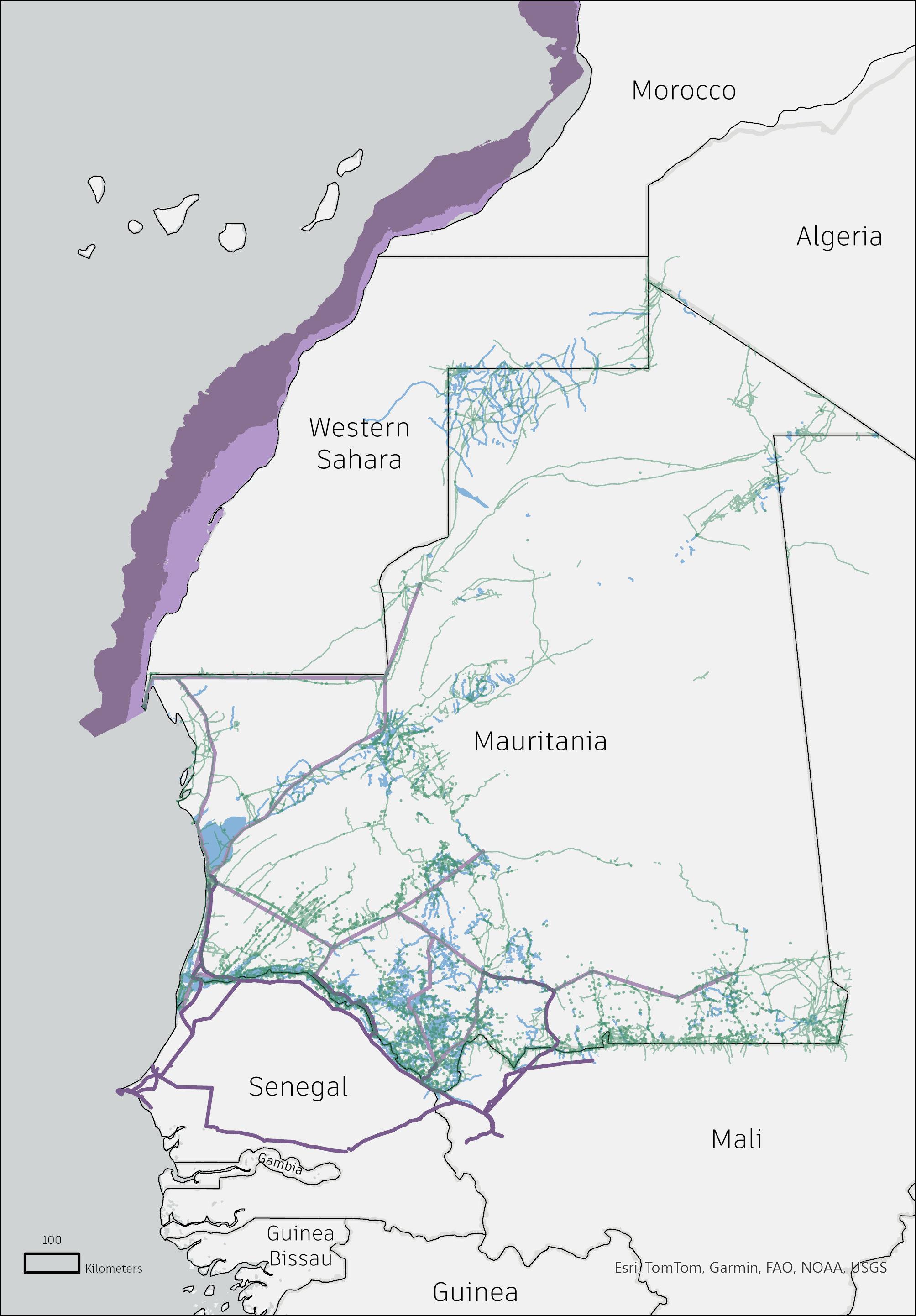

Migration in the Sahel is as old as human habitation, but accelerating climate change raises new questions about its scale and drivers. Traditional transhumance herding faces growing challenges from colonially drawn borders, sedentarised pastoralists, and resource scarcity. Cyclical droughts have intensified social strife, destabilized nations, and fueled insurgencies and military coups.

Ersi, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Map Source: Esri, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Content Source: UN FAO; EU IOM, Michele Nori Major Migration Corridors (Road and Sea Routes) Cross-Border Transhumance

Transhumance

Traditional herding groups along the Sahel make common use of the transhumance corridors, often covering routes which transcend national borders frequently and even ethnic boundaries on occasion. Maintenance of these critical routes is a vital community good; stability along major routes is essential to the economic and social viability of the migratory communities which use them.

Ersi, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Map Source: Esri, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Content Source: UN FAO; EU IOM, GIS Reports, Michele Nori

Transhumance

Domestic Transhumance

Cross-Border Transhumance

Migration Areas

Moorish Ethnic Group Migration Range

Fulani Ethnic Group Migration Range

Tuareg Ethnic Group Migration Range

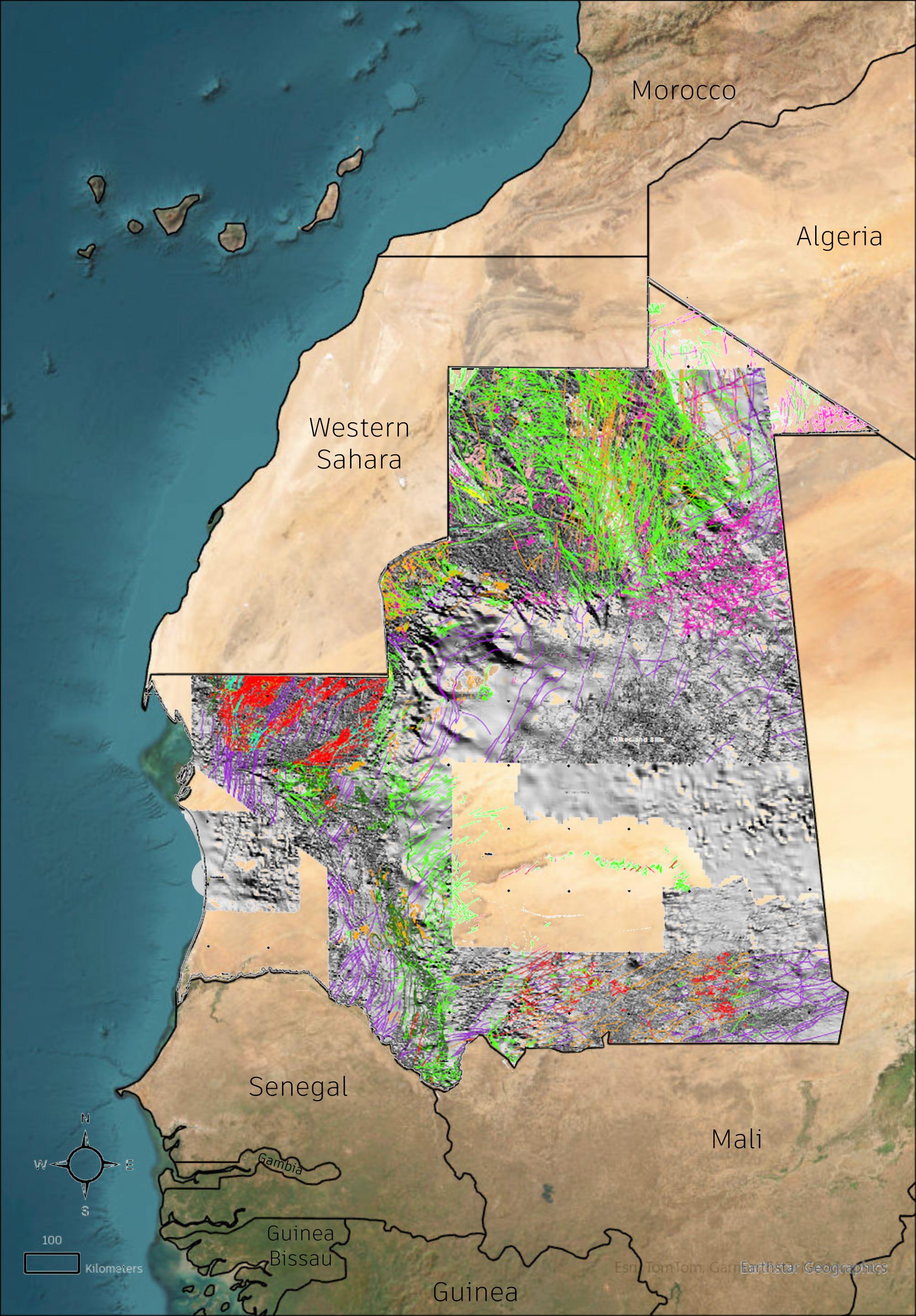

Instability in Mali and Burkina Faso has severely threatened freedom of movement—both for commercial traffic and traditional transhumance routes. The danger along these corridors burdens economic systems, deepens poverty, and fuels further instability. Ongoing disruption to daily life undermines long-term viability of political and social structures and must be addressed to break the conflict cycle.

Ersi, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Map Source: Esri, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Content Source: UN FAO; EU IOM, GIS Reports, Michele Nori.

Transhumance & Migration

Domestic Transhumance

Cross-Border Transhumance

Major Migration Corridors (Road and Sea Routes)

Conflict & Instability

Assessed Attacks by JNIM

Assessed Attacks by ISSP

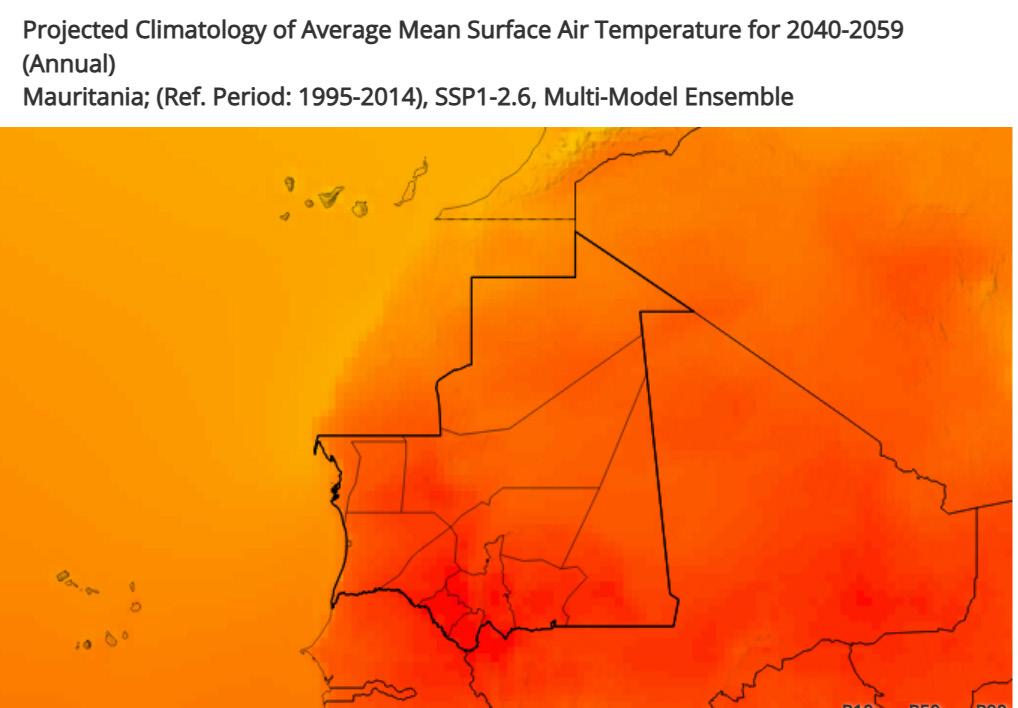

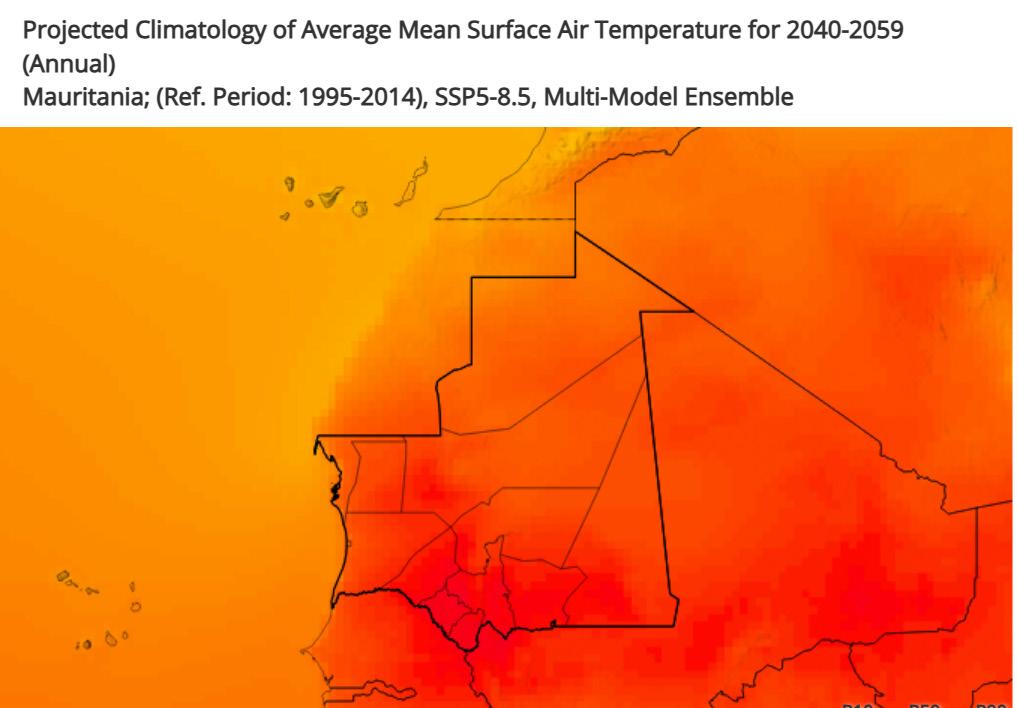

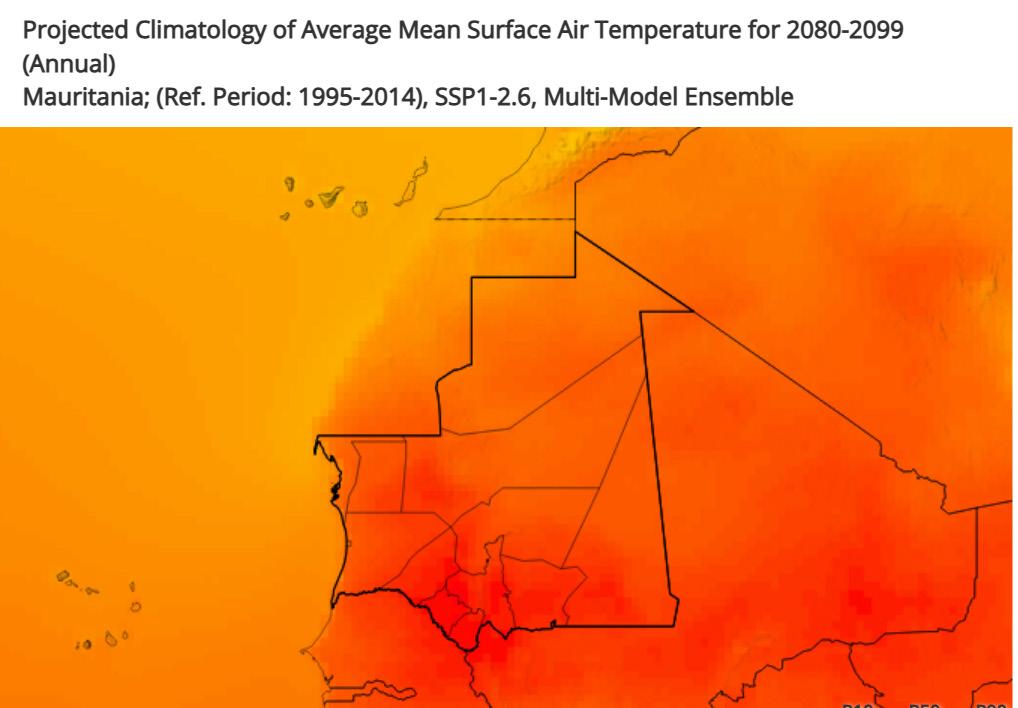

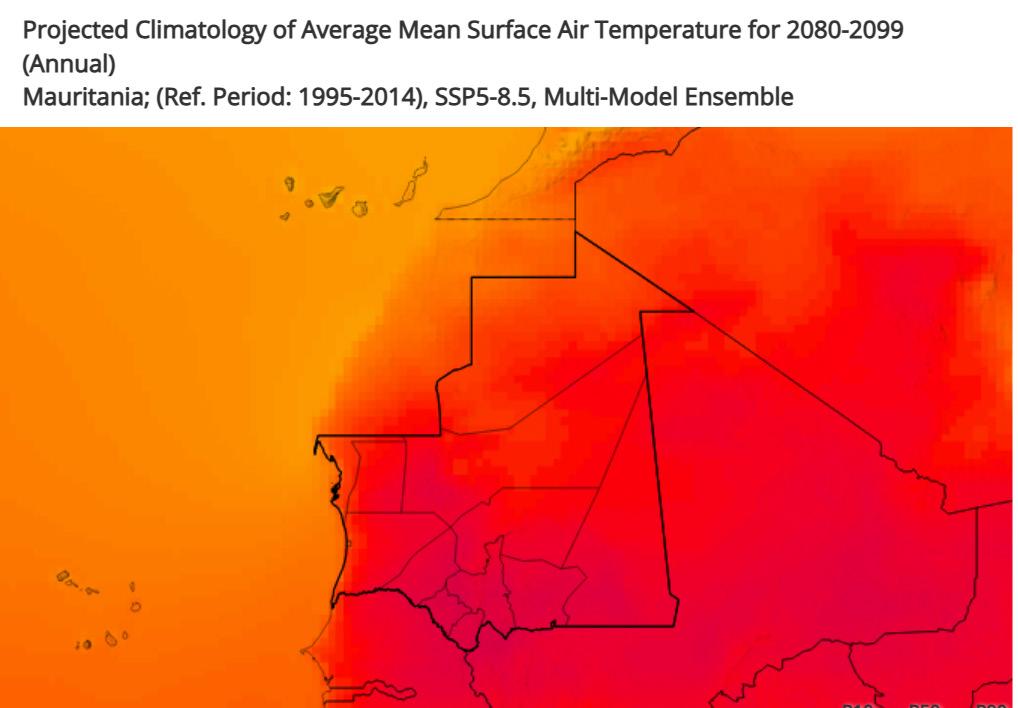

Mauritania faces severe temperature increases under IPCC projections, exceeding global averages due to its location in the Sahara/North Africa region. Under SSP1-2.6 (lower emissions), mid-century (2040–2059) warming reaches 1.5–2.3°C, rising to 2.0°C by 2080–2099. In contrast, SSP5-8.5 (high emissions) projects mid-century increases of 1.8–4.4°C, escalating to 4.4–5.6°C by 2100. These extremes-up to triple the global average under SSP5-8.5-highlight accelerated aridification risks, with northern Mauritania particularly vulnerable to 5.6°C rises by 2100. The projections underscore the critical need for emissions mitigation to avoid catastrophic warming trajectories.

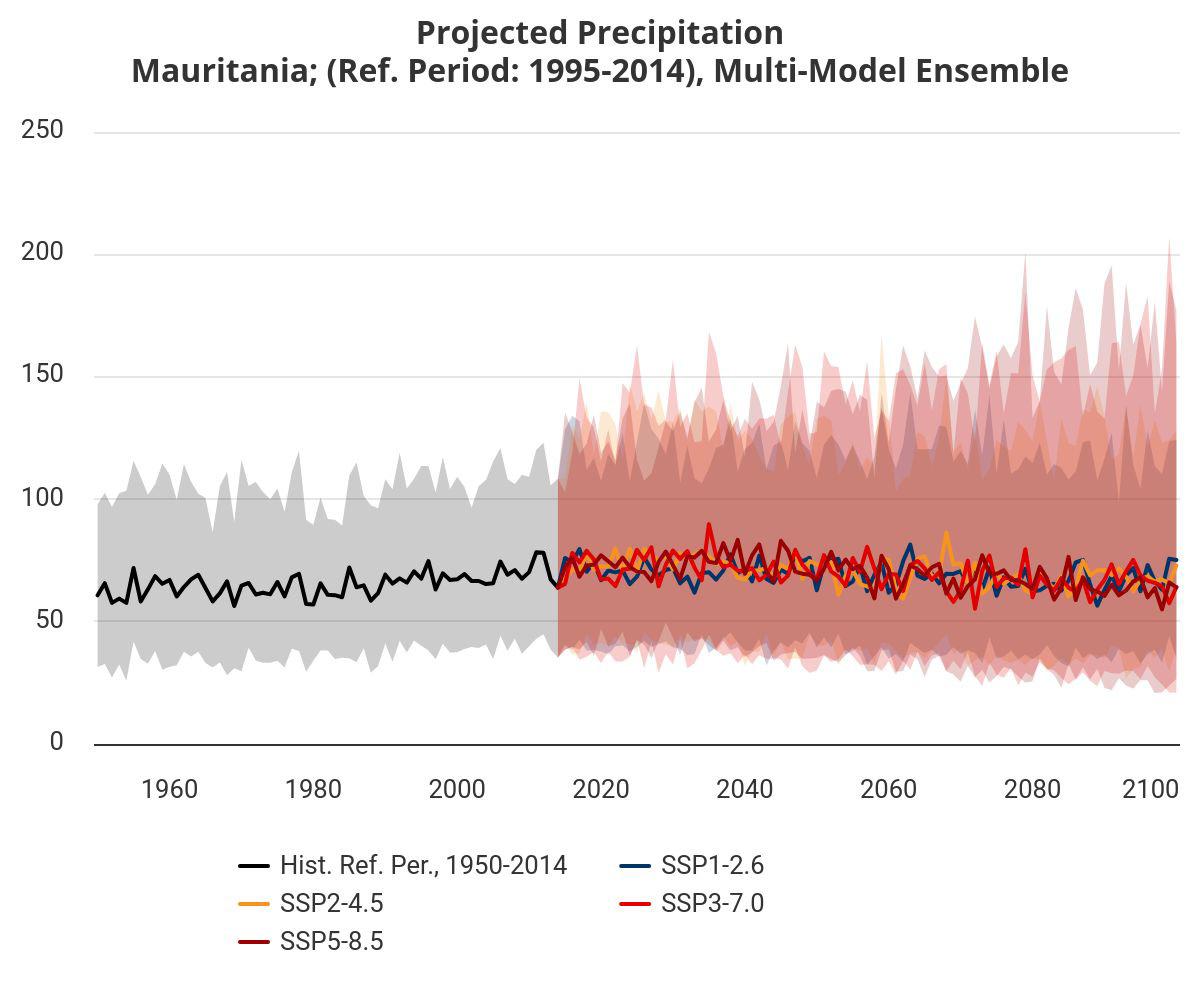

Projected Climatology of Precipitation for 2080-2099 (Annual) for Mauritania (Reference Period: 1995-2014), Multi-Model Ensemble Source: Climate Change Knowledge Portal, World Bank Group

Mauritania’s precipitation outlook varies by emissions scenario: under SSP1-2.6, rainfall may increase slightly or remain stable, while SSP5-8.5 projects an annual decrease of 11 mm by 2080. Combined with rising temperatures, high emissions will intensify droughts and aridification, while also increasing the risk of extreme, erratic storms.

Rising temperatures in Mauritania amplify precipitation extremes through thermodynamic mechanisms: each 1°C increase enables the atmosphere to hold 7% more moisture (ClausiusClapeyron relationship), intensifying downpour severity during rare rain events despite projected annual rainfall declines. This creates a dangerous paradox where chronic drought conditions coexist with flash flooding risks, as heated soils lose infiltration capacity while convective storms deliver concentrated rainfall bursts.

Mauritania is experiencing rapid climate change, with temperatures projected to rise by 2.0°C to 4.5°C by 20801.5 times faster than the global average. Recent decades have already seen temperature anomalies 2–3°C above preindustrial levels, and by 2080, the country could face 49 more days per year above 35°C. This intense warming is driving a surge in natural disasters, severely impacting agriculture, health, and water resources.

Droughts are becoming more frequent and severe as higher temperatures increase evaporation and reduce soil moisture, shortening growing seasons and depleting groundwater. Over half the population has been affected by droughts since the 1990s, with significant crop and livestock losses.

Wildfires are also on the rise. Extreme heat dries vegetation, making it more flammable. In regions like Hodh el Chargui, wildfire incidents have more than doubled in recent years, often sparked by land-clearing practices that become dangerous under hotter, drier conditions.

Floods, paradoxically, are increasing as well. While overall rainfall may decline, intense storms are becoming more common, overwhelming infrastructure and causing urban flooding, especially in Nouakchott.

These interconnected disasters are intensified by climate change: heatwaves dry out land, fueling droughts and wildfires, while also destabilizing weather patterns and leading to flash floods. The result is a cycle of vulnerability that threatens Mauritania’s food security, economy, and public health, demanding urgent adaptation and resilience measures.

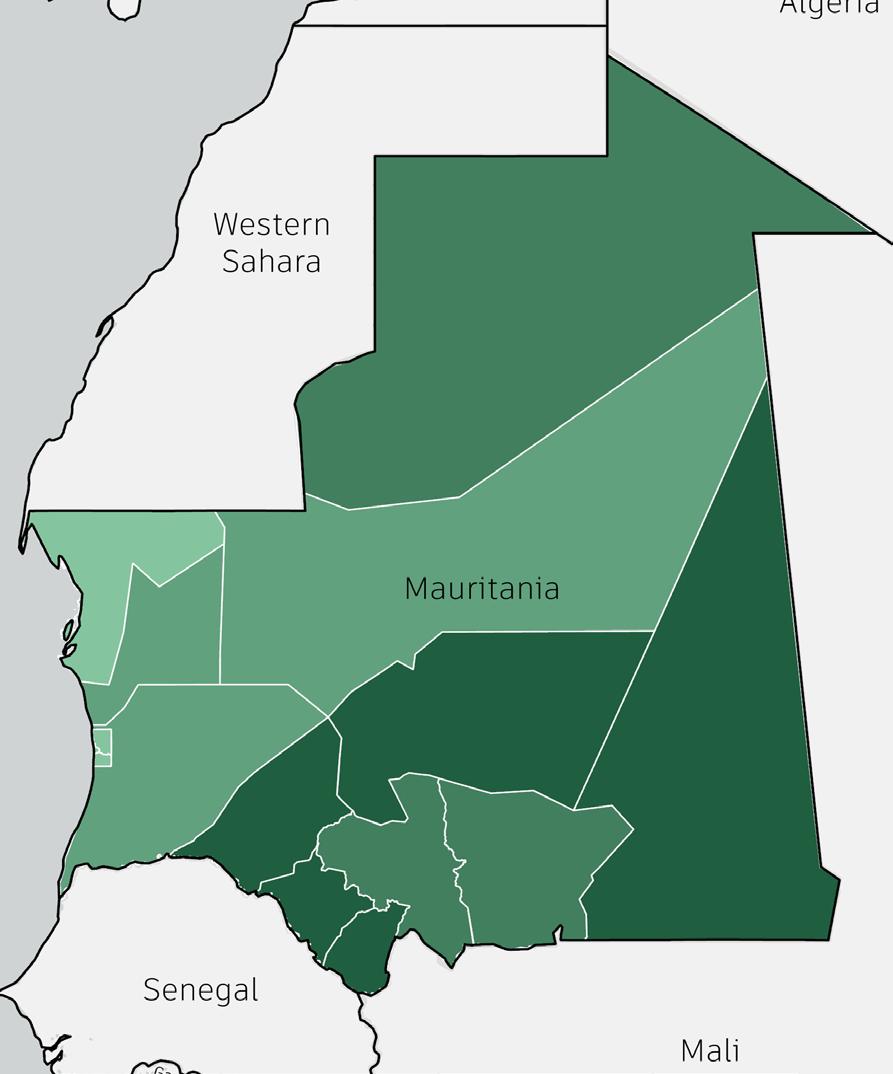

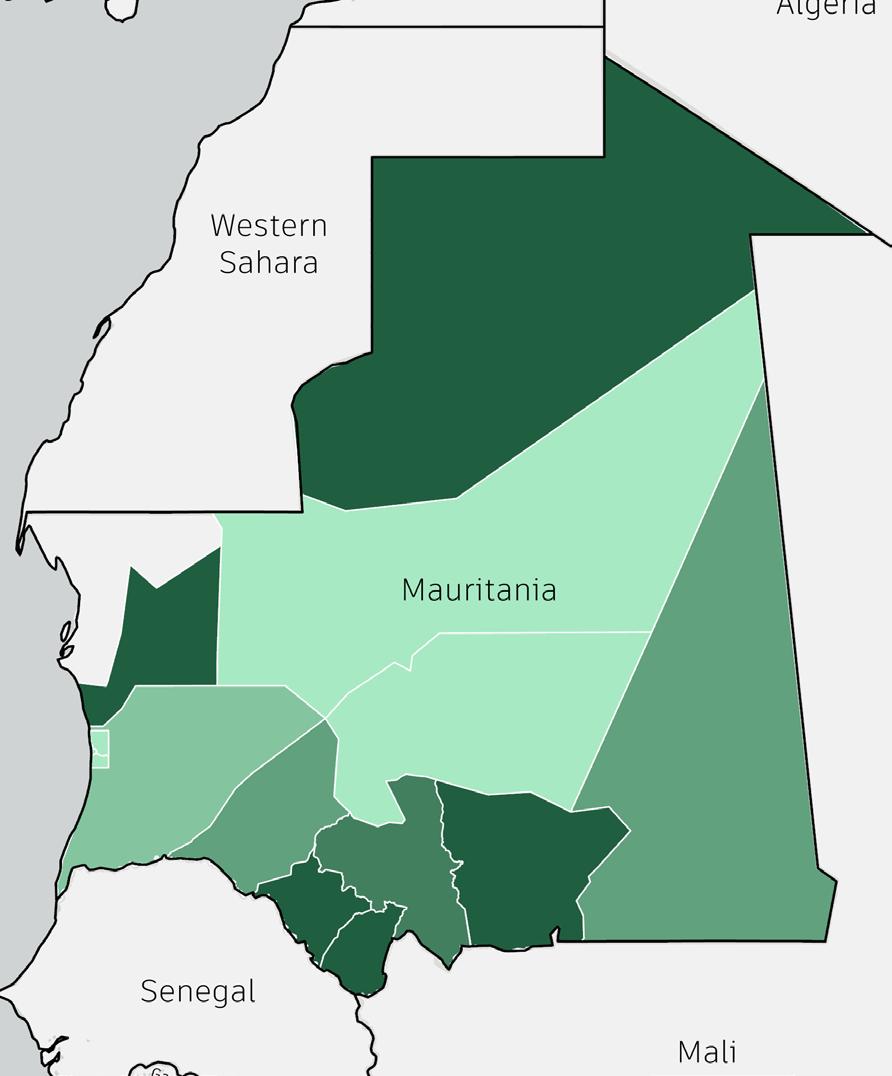

The southern regions of Mauritania-particularly Hodh Ech Chargui, Assaba, and Brakna-face unparalleled climate vulnerability due to their exposure to compounding extremes: recurrent droughts, accelerating desertification, and erratic rainfall patterns. This zone, which transitions from the Sahelian belt to the Sahara, is projected to warm 1.8–4.4°C by 2050 under high-emission scenarios (SSP5-8.5), amplifying water scarcity and heat stress. Over 85% of southern livelihoods depend on climate-sensitive rainfed agriculture and pastoralism, yet droughts now occur twice as frequently as in the 1980s, slashing crop yields by 30–50% and triggering livestock mortality rates exceeding 40% in severe years. Meanwhile, erratic rainfall-concentrated in intense, destructive storms-has increased flood frequency by 60% since 2000, eroding soils and degrading 12% of arable land in Guidimaka alone.

Compounding these risks, 60.9% of Mauritania’s population, including 139,000 Malian refugees in Hodh Ech Chargui’s Mbera camp, is concentrated in the south. Refugee inflows, driven by regional instability, strain already scarce water and grazing resources, intensifying competition between communities. In Assaba, groundwater levels have dropped 3 meters since 2015, forcing pastoralists to migrate 50% farther annually and sparking a 22% rise in resource conflicts. Urban centers like Kiffa face dual pressures: drought-driven rural migration has swelled the city’s population by 8% annually, while erratic floods inundate 35% of informal settlements each rainy season. This demographic-climate nexus creates a feedback loop: resource scarcity heightens social tensions, while extreme weather undermines adaptive capacity, locking vulnerable communities into cycles of displacement and food insecurity. Without targeted intervention, southern Mauritania risks becoming an epicenter of climate-driven humanitarian crises.

18 - 166

Adaptation Priorities

Heat Adaptation Priority

Flood Adaptation Priority

Drought Adaptation Priority

4,514 - 1,2687

167 - 4,513 12,688 -104,658

Data: Think Hazard, GFDRR, World Bank Humanitarian Dataset

Current and future projections of heat risk (measured as days per year with temperatures exceeding 40°C) show most of Mauritania’s population lives in the regions with the highest risk. The current (2021–2040) heat risk is generally high, with most areas experiencing around 50 days per year above 40°C, but future projections (2061–2080) show much of the country facing over 100 such days annually. Particularly in areas already strained for resources like water and cooling infrastructure.

This underscores the need for either expanded infrastructure or redistribution of the population. The latter would likely require a major rework of road networks, which may not be economically or temporally feasible, and would again displace refugees. Additionally, Mbera Camp is in one such vulnerable location, and with issues of shelter materiality (i.e., metal housing in a desert), refugee camp design must be reexamined.

2061-2080

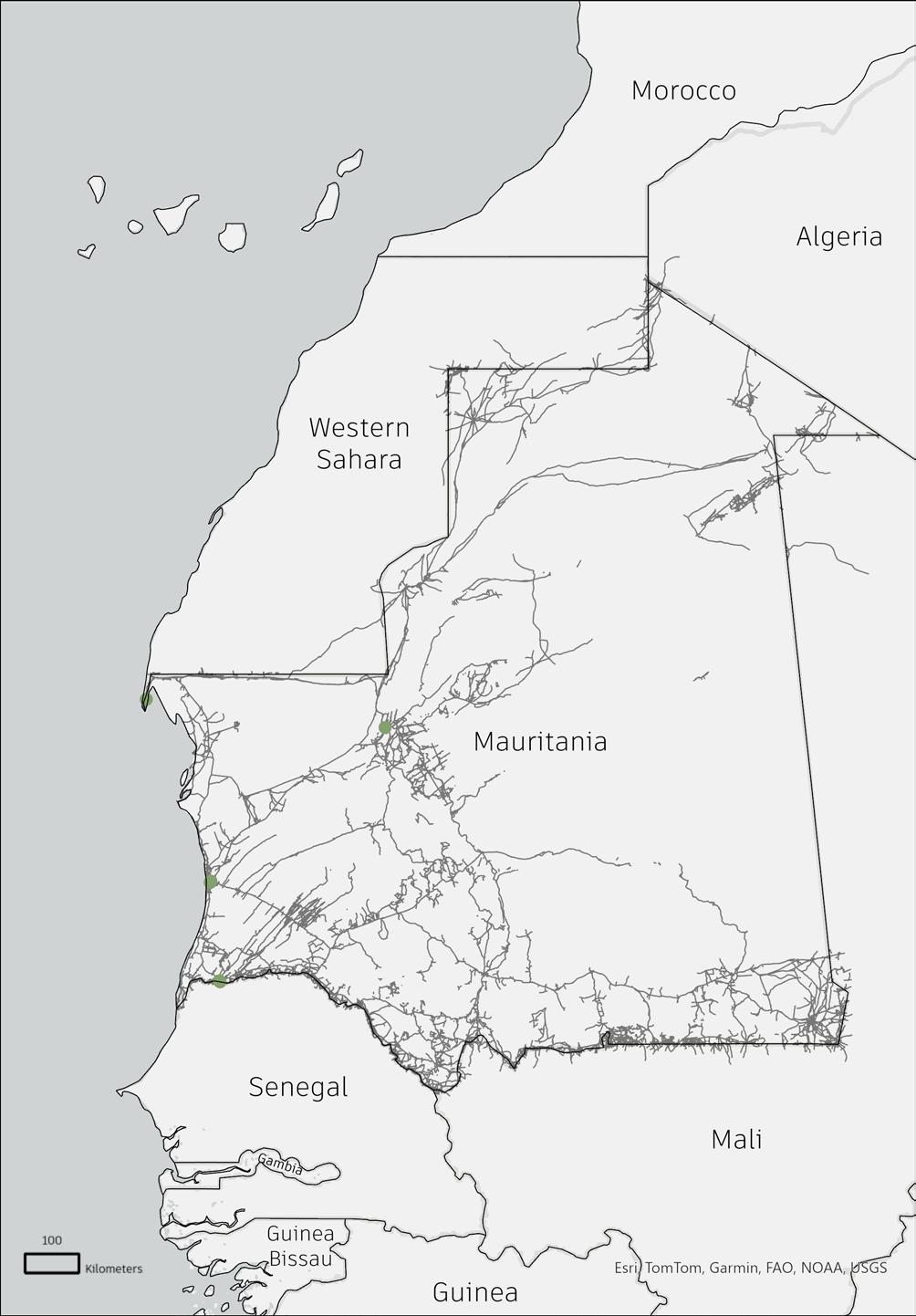

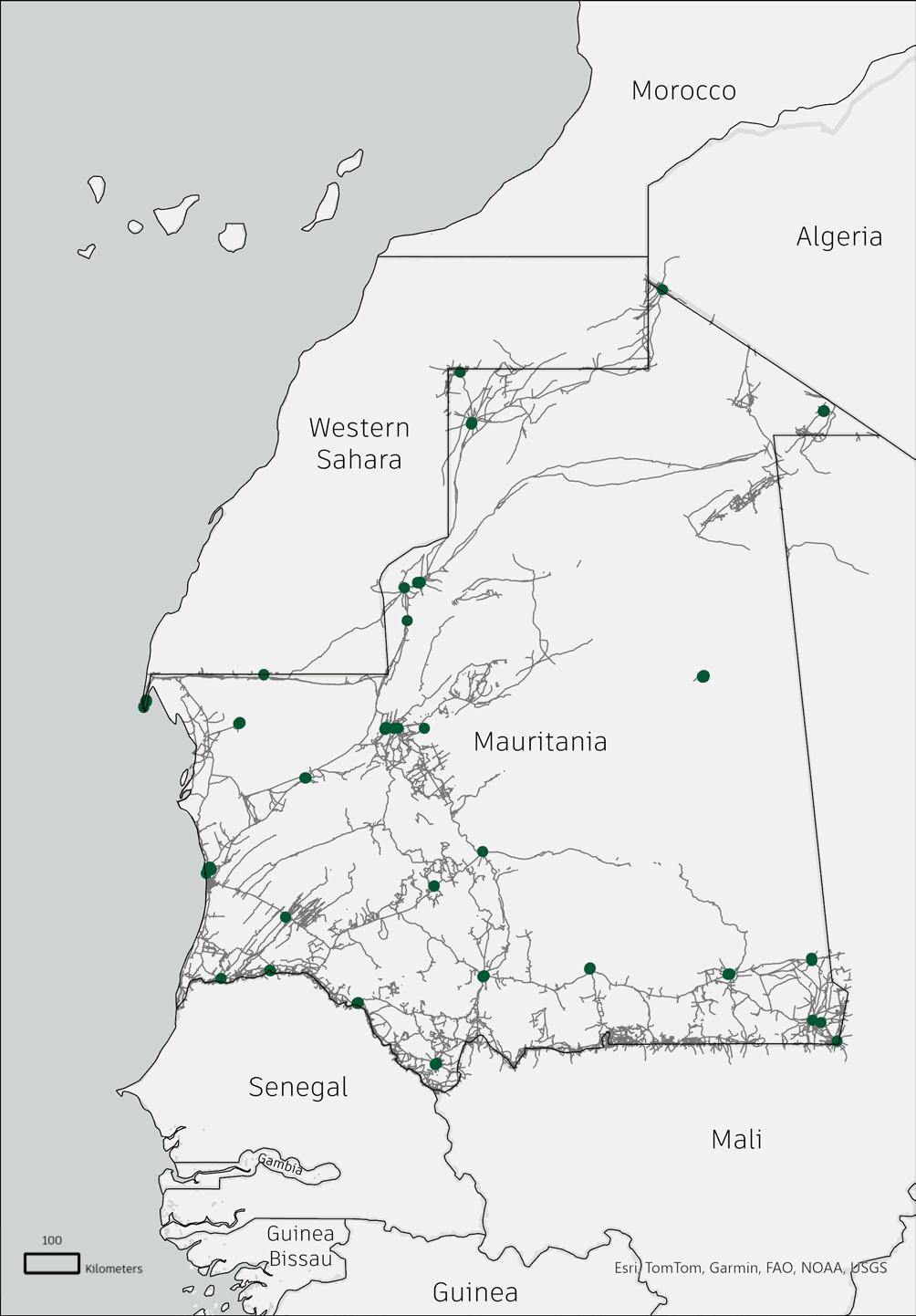

Current habitation data of Mauritania shows a high concentration of residents along the southern and southeastern borders, as well as around Nouakchott. Additionally, many settlements located further from the country’s borders are along highways or other main transport routes.

However, the primary settlement location of displaced migrants in the country is at the Mbera refugee camp in the southeast. This raises concerns about potential lack of infrastructure and resources for refugees located outside of Mbera, especially in more dense locations like Nouakchott, which has the highest concentration of refugees per area of any Mauritanian administrative region.

Further, this map overlays population distribution with the estimated levels of food insecure peoples per administrative region: this shows the southeastern region to have the highest number of this population, likely due to the high count of refugees and irregular access to food. Combined with previous maps of heat risk, the southern regions not only have high vulnerability to extreme heat, but are already facing food insecurity. With future projects of heat only becoming more extreme, the combination of factors presents a significant concern.

This data suggests a need for expanded and more evenly distributed refugee-specific infrastructure in the country, especially in the west and north. Combined with the climate vulnerabilities faced within Mauritania, many refugees live in high-risk areas, specifically in regard to drought and food insecurity. Thus, a more connected network is needed to reduce potential strain on resources and infrastructure throughout the entire country.

Populated Places

Administrative Region Boundary

With its highly arid territory and relatively small share of cultivable land, Mauritania’s economy heavily relies on resource extraction and attendant industries. Iron ore forms the preponderance of this sector, with 14,000,000 tonnes mined in 2023, making Mauritania a top-20 global producer. Copper, gold, though smaller, also play a significant role –gold production alone soared to 620,000 ounces in 2023. In recent years, oil and gas has shown emergent potential for Mauritania’s economy, with promises of additional revenues and potential for diversified foreign investment. On the whole, the mining sector contributes a sizable share of Mauritania’s total exports, GDP, and contributes a large fraction of total government revenue.

Mauritania is rich in mineral resources, with iron ore as its leading export—ranking second in Africa in 2019. SNIM operates key mines like Guelb El Rhein.

The country also has significant deposits of gold, copper, gypsum (near Nouakchott), and phosphate rock (near Bofal).

Other extracted or explored resources include uranium, tantalum, crude oil, natural gas, salt, cement, granite, marble, and quartz. These extractive industries are central to the economy but pose challenges for environmental and social sustainability.

Types of Minerals Available

Types of Minerals Available

Data: USGS Data for Mineral Deposits in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania Open-File Report 2013-1280-S

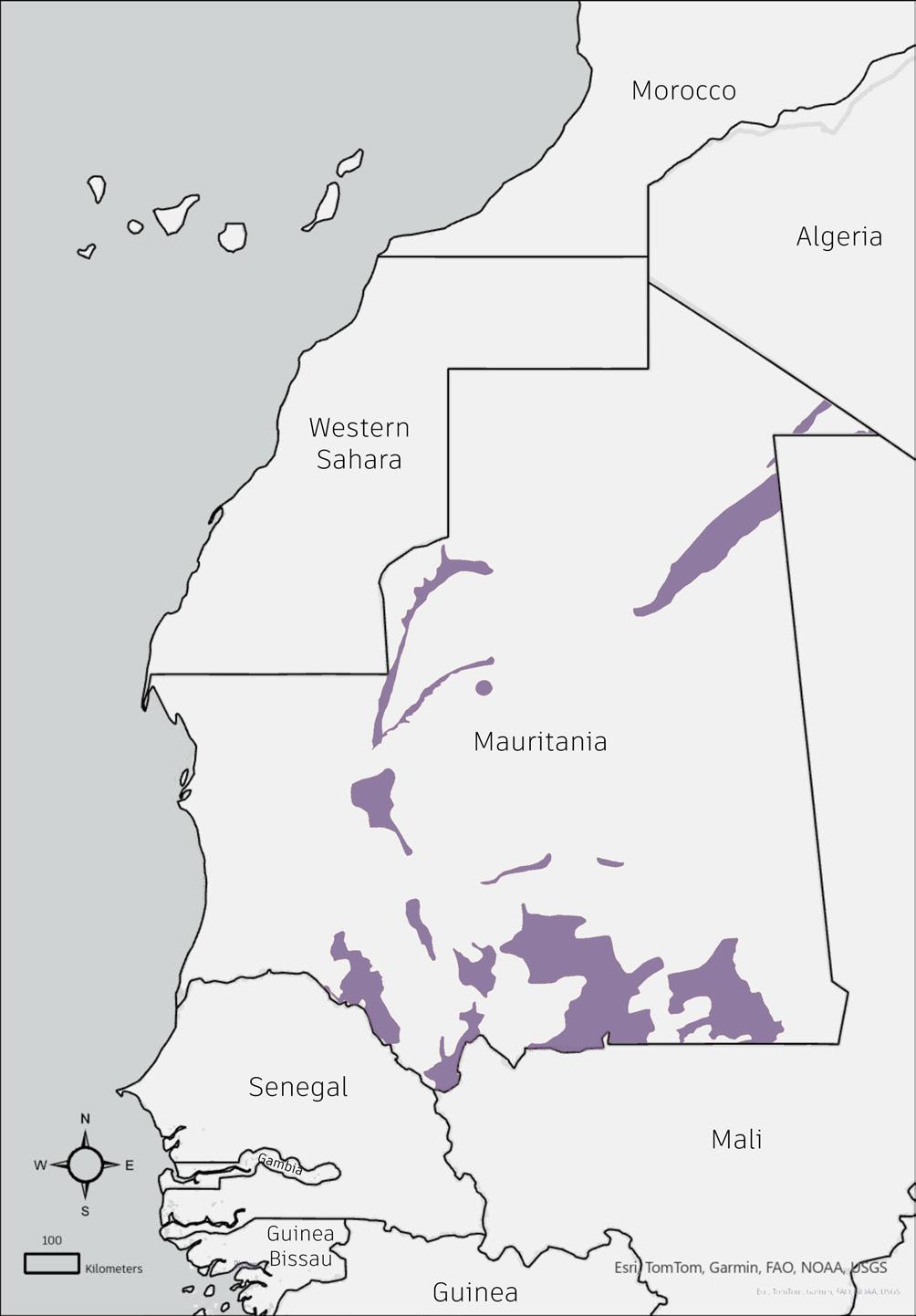

Analyzing the geological structure map overlayed with all the mining maps we get to see a few inferences:

1) All the mining areas have undeferential faults not just within the mining region but surrounding it resulting in making the land around the region susceptible to major vulnerabilities

2) The mining regions have more than one geospatial fault or anomaly, such as thrust or lineation, thus suggesting that the mining epicenters are creating a ripple/a domino of soil issues.

Susceptible to major vulnerabilities

Economic Dependence: Mauritania’s economy is highly dependent on the extractive sector, with mining contributing significantly to GDP and exports.

Social Conflicts: Social conflicts have centered on mining workers’ rights, community relations, and environmental impacts of extractive activities.

Environmental Concerns: Mining activities can lead to environmental issues such as dust pollution, water contamination, and habitat destruction.

Types of Minerals

Titis Zemmour Solar catchment zone

Direct Normal Irradiation map suggesting the region of Tiris Zemmour being highly susceptible to solar radiation making the livelihood opportunities concerning coupled with mining activities

Relationship to Risk Hotspots:

Increased Flood Risk: Mining disrupts drainage, reduces soil absorption, and creates pits/tailings dams that overflow during floods.

Water Contamination: Floods spread toxic mining byproducts (e.g., heavy metals, cyanide), polluting rivers and groundwater.

Tailings Dam Failures: Floodwaters compromise dam integrity, risking collapse and downstream damage.

Sedimentation & Erosion: Mining accelerates river sedimentation, reducing flow capacity and worsening floods.

Loss of Natural Buffers: Mining degrades wetlands and floodplains, removing natural flood defenses.

Water overflows (Flooding zones) with Mining Activities

Relationship to Risk Hotspots in case of Settlements, Flood Zones and Mining Activites as Concentration:

High Exposure: Migrants often live in informal, flood-prone settlements near mines, increasing their vulnerability.

Toxic Flooding: Floods spread hazardous mining waste into dense migrant zones, causing health crises.

Fragile Infrastructure: Poor housing and drainage in migrant areas heighten flood and collapse risks.

Limited Aid Access: Migrants may miss early warnings and relief due to legal or language barriers.

Economic Trap: Dependence on mining jobs keeps migrants in unsafe, high-risk areas.

Water overflows (Flooding zones) with population concentrationswith Mining Activities

Population concentration

USGS

Zebeeb Nuguse

Richard Kowel

Haozhuo Yang

Mauricio Cohen Kalb

Food, electricity, access to healthcare, mobility, and most importantly, water are essential resources for life in the Sahel.

The region relies heavily on transboundary aquifers, which provide a critical water source for both urban populations and remote communities such as those in and around M’Bera camp. These shared groundwater reserves require coordinated management between Mauritania and neighboring states. Access to health care remains limited, especially for mobile populations who rely on pastoralism and transhumance. Many health facilities are concentrated in urban centers, leaving large rural areas underserved.

Efforts to expand renewable energy are reshaping Mauritania’s energy landscape, although electricity access remains low in rural areas. Infrastructure development, including transport networks and cross-border electricity projects, plays a growing role in supporting both mobility and resource distribution.

Across each theme, the maps illustrate the spatial dimensions of access, scarcity, and interdependence.

The Water Crisis in Mauritania. Source: Starfish Journal. https://thestarfish.ca/journal/2023/12/the-water-crisis-in-mauritania-an-alarm-of-climate-change

Mauritania Economic Memorandum. Source: World Bank - https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/africacan/mauritanias-future-economic-diversification-and-struc

Mauritania Culture Health Promotion. Source: EU Commission - https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/stories/mauritania-culture-vec-

Mauritania. World Food Program. USA. Source: https://www.wfpusa.org/countries/mauritania/

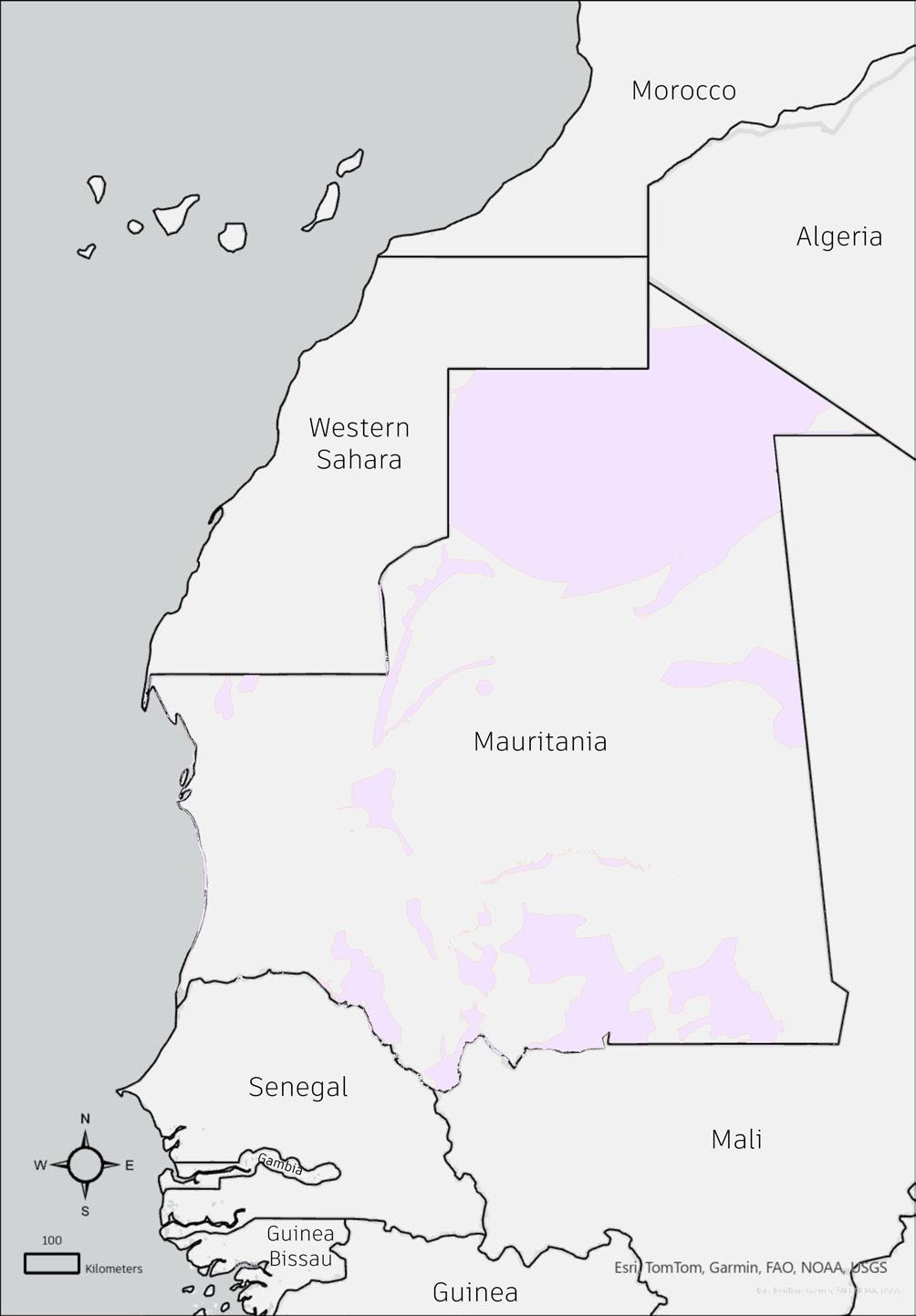

Aquifers are bodies of permeable rock which contain or transmit water. The Taoudeni and Irhazer-Iullemeden Aquifer System are in continuity with each other and form Africa’s second largest aquifer system.

Mbera camp, located in the Dhar de Nema sector, is fortunate to be in a high-water potential area with very little vulnerability to climate change-induced precocity. High flow rates in Dhar de Nema are enabled by thickness and high permeability of the aquifer formations.

However, the climatic conditions of the Taoudeni basin, varying from a hot and humid in the south to an arid climate in the center and north, do not allow for complete replenishment of water resources. This is further exacerbated by growing demand, with population rates growing at roughly 3%/year in the central and southern areas.

The Taoudeni basin’s water resources are by nature inter-dependent and require transnational collaboration and stewardship between Mauritania, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Groundwater resources are increasingly threatened by growing water demand and multiple sources of pollution and exploitation, resulting in degraded and highly mineralized waters.

TINDOUF BASIN

Western

Western

SENEGALOMAURETANIAN BASIN

SENEGALOMAURETANIAN BASIN

Senegal

Guinea

Guinea

Liberia

Liberia

TAOUDENI BASIN

TAOUDENI BASIN

Transboundary Aquifer

Vulnerable

Transboundary Aquifer

Moderately

Moderately Vulnerable

Mauritania is in the midst of a major energy transition, increasingly relying on renewable sources to meet its domestic and regional energy needs. More than 40 percent of the country’s electricity is now generated through wind and solar power. Major projects include new solar plants, wind farms (like Boulenouar), and the Mauritania-Mali electricity interconnection to boost regional energy trade.

Despite progress, only approximately 56 percent of the population has access to electricity in urban areas, while rural access is limited to only about 5 percent. This has prompted investments in mini-grids and rural electrification projects.

Mauritania is positioning itself as a future leader in green hydrogen production and the export of renewable electricity to neighboring countries. As the country continues to build out its energy infrastructure, cross-border cooperation will play a central role in shaping both regional energy security and long-term climate resilience

Transmission Lines (SOMELEC)

Transmission Lines (OMVS) Populated Areas Data

Livestock is vital to livelihoods, food security, and economies in the Sahel, with herd sizes varying by geography and climate. Chad leads the region with the largest numbers of cattle, sheep, goats, and camels, highlighting its central role in pastoralism. Nigeria also holds significant livestock, especially goats and sheep, supporting both pastoral and agro-pastoral systems. Mauritania, despite smaller overall numbers, has a notably high camel population adapted to its desert environment, while Niger and Senegal maintain diverse herds that reflect strong

Data Source - https://nextgis.com/

pastoral and mixed farming traditions.

These figures emphasize the shared dependence on livestock across Sahelian countries and highlight the transboundary nature of pastoralism. Seasonal migration for grazing and water links these countries ecologically and economically, making regional cooperation essential for managing resources, addressing climate stress, and supporting pastoralist resilience in this environmentally fragile region.

The Sahel region is inhabited by numerous nomadic communities who rely on pastoralism and transhumance for their livelihoods. Providing them with adequate access to healthcare services is essential for supporting their well-being and upholding their fundamental human rights. In this map, hospitals, health centers, medical clinics, and health posts are defined as health facilities.

The distribution of healthcare facilities in the region is limited, with most concentrated in larger urban areas. The distance between populations and healthcare facilities also significantly impacts patient outcomes, as every 10-kilometer increase in straight-line distance from a facility raises the mortality rate by 1%. The people of Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, and Chad are particularly affected by this scarcity, including the nomadic population who are passing through these countries during transhumance and pastoralism practices.

Source: World Health Organization – https://www.afro.who.int/news/who-releases-more-us-8-million-sahels-humanitarian-response

Data Source - https://nextgis.com/

Health Facility

Spatial Access for 5% Mortality Rate

Transhumance & Pastoralism Region

Spatial Access for 10% Mortality Rate

Data Source - https://nextgis.com/

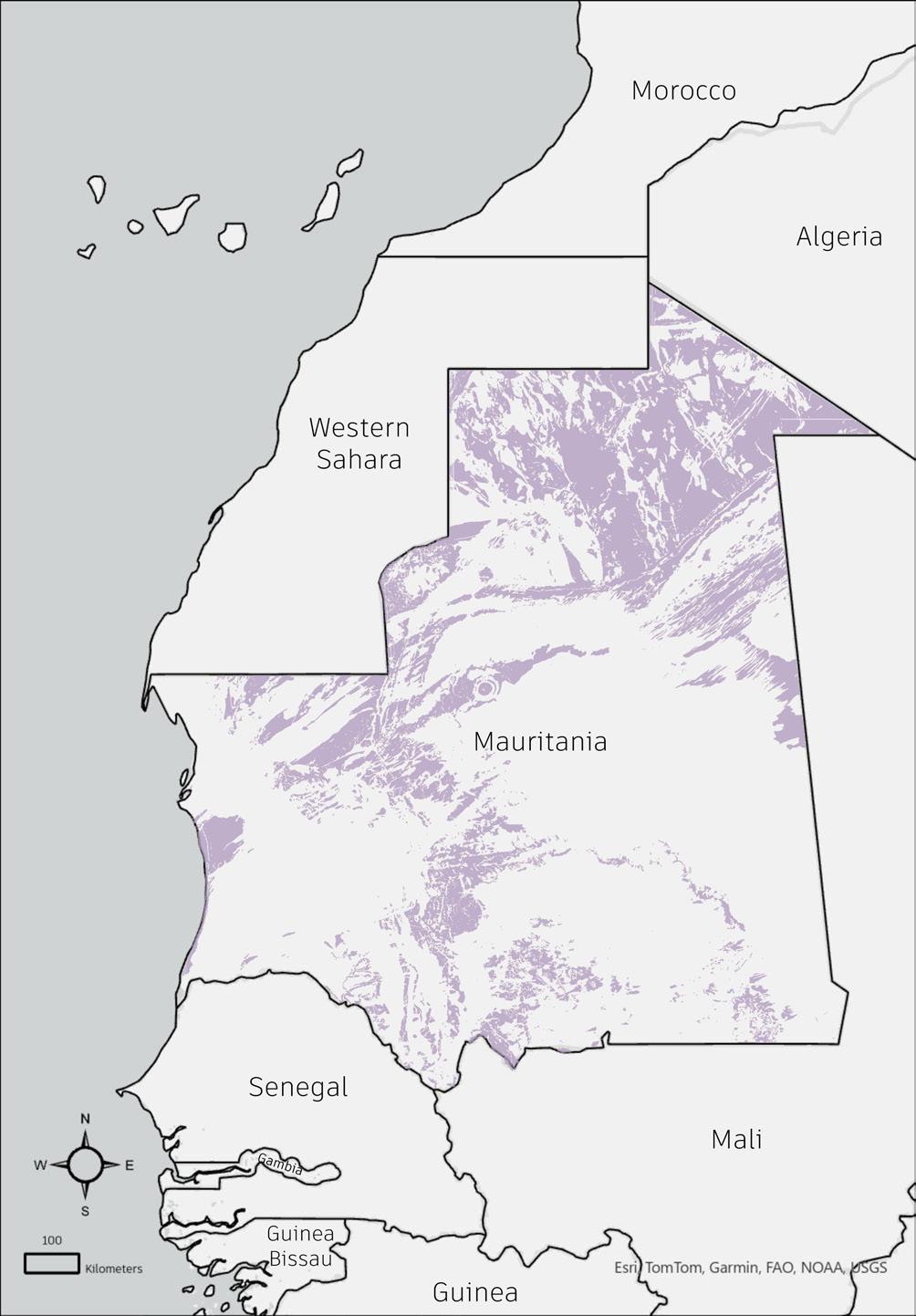

Mauritania’s surface water resources are defined by extreme seasonal variability, with ephemeral wadis (sand riverbeds) acting as the primary hydrological arteries. These wadis remain dry for 9–10 months annually (October–June), appearing as barren channels, but transform during the brief July–September rainy season into torrents fueled by intense, localized storms. Climate change has amplified this volatility: since 2000, rainfall intensity has increased by 20%, causing flash floods that erode banks and deposit 30% more sediment into alluvial aquifers, reducing groundwater recharge capacity. Meanwhile, the rainy season has shortened by 15 days, leaving temporary lakes (mares) in topographic depressions-critical for pastoralists and wildlife-to evaporate 40% faster, with 90% drying completely by mid-November.

This unpredictability creates cascading challenges:

Infrastructure strain: Concrete dams in Hodh El Gharbi and Tagant regions lose 25–40% of storage capacity annually to sedimentation from flood-borne sands.

Agricultural disruption: Farmers relying on spate irrigation face a 50% risk of crop failure when delayed rains or early dry spells interrupt planting cycles.

Ecological stress: Endemic species like the Lappet-faced Vulture lose 70% of breeding sites as mares vanish, while invasive Prosopis juliflora shrubs colonize 12% of wadi beds annually, blocking water flow.

The concentration of 85% of rainfall into just 5–10 extreme storm events annually-often exceeding 100 mm/day-overwhelms traditional water-harvesting systems.

The area of the rectangle of southeastern Mauritania encompasses three distinct physical environments. In the northernmost zone there are arid desert conditions with minimal vegetation and extremely low rainfall.

To the south, near the Malian border, a narrow strip of Sudano-Sahelian environment introduces slightly more humid conditions and seasonal vegetation. The remainder of the region falls within the broader Sahelian zone, defined by sparse rainfall, semi-arid grasslands, and transitional ecological features. The geology of Mbera Camp is shaped by Quaternary deposits composed of coarse sediments. These materials exhibit high primary permeability, making them suitable for aquifer formation.

However, geologically, the groundwater depth and distribution is unpredictable. Groundwater availability in the region is largely dependent on recharge dynamics. In the Mbera camp area, recharge occurs primarily through slow underground flow from the southern sectors, roughly aligned within Amourj district. Local recharge from direct rainfall is minimal, due to the arid climate and high rates of evapotranspiration. Thus, aquifer sustainability is highly sensitive to long-term climate variability and land use practices.

Quartermary Sediments & Rocks

Mesoproterozoic Supracrustal Rocks

Melange Unit

Paleozoic Supracrustal Rocks

Archean Supracrustal Rocks

Paleoproterozoic Intrusive Rocks

Cenzioc Supracrustal Rocks

Paleoproterozoic Supracrustal Rocks

Mesozoic Supracrustal Rocks

Archean Intrusive Rocks

Neoproterozoic Supracrustal Rocks

Mesozoic Intrusive Rocks

Neoproterozoic Intrusive Rocks

Source - https://www.academia.edu/85230492/Groundwater_features_in_Hoedh_el_Chargui_Mauritania?uc-sb-sw=24114700

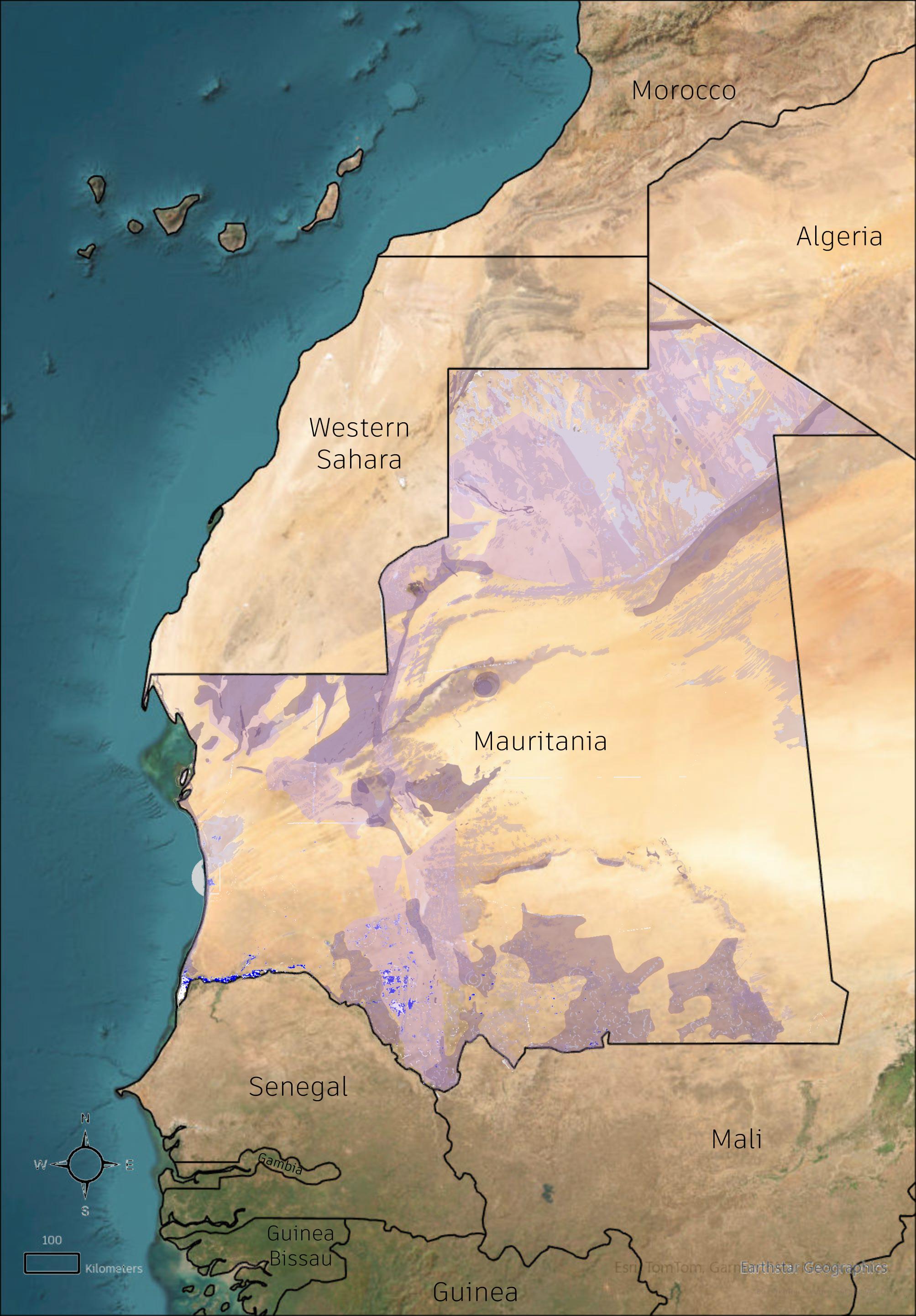

This USGS-derived hydrological map reveals critical insights into Mauritania’s groundwater dynamics and exploitation pressures. Blue flowlines trace subsurface water movement, which follows gradients in the water table (slopes) and permeability variations in geological strata-notably faster flows in sandstone aquifers (e.g., Taoudeni Basin) versus sluggish movement in Precambrian basement rocks. Equipotential lines (light blue) highlight the water table’s elevation, showing groundwater generally flows southeast-to-northwest, converging toward the Senegal River Valley.

The light green-to-dark gradient exposes stark regional disparities:

Shallow static levels (green) along the Senegal River border (0–15 m depth) reflect recharge from seasonal flooding and alluvial deposits.

Deep green zones in the southwest (Guidimaka, 80–120 m depth) and southeast (Hodh Ech Chargui, 100+ m) signal severe overexploitation, driven by irrigated agriculture (southwest) and refugee camp demands (Mbera, southeast).

Infrastructure gaps compound these issues-70% of southeastern wells exceed sustainable yields, lowering water tables 1–3 m/year. The map underscores the urgent need for managed aquifer recharge in red zones and transboundary cooperation along flowlines to mitigate scarcity.

Hydrology Equipotential Lines

Hydrology Flowlines

0

This map reveals Mauritania’s fragile agricultural lifeline, with 95% of the nation’s food production concentrated in the southern “Food Corridor”-a 150 km-wide belt along the Senegal River Valley spanning Guidimaka, Gorgol, and Assaba regions. Key insights:

Cropland distribution: 85% of rainfed agriculture (sorghum, millet) clusters within 50 km of the Senegal River, leveraging alluvial soils with 1.2–1.8% soil organic carbon (SOC)-triple northern desert soils (<0.5% SOC).

Soil-carbon nexus: High SOC zones (dark green) near Boghé and Kaédi support 70% of irrigated rice farms, while low-carbon sandy soils (yellow) in Hodh regions face 30% yield declines from erosion.

Infrastructure gaps: Only 12% of roads linking farms to markets are paved, causing 25–40% post-harvest losses. Seasonal mares (waterbodies) sustain 90% of pastoralists but dry 3 weeks earlier than in the 1990s.

Demographic pressure: 70% of rural settlements lie within the Corridor, including 139,000 Malian refugees in Hodh Ech Chargui, straining land and water.

The Corridor’s dominance is precarious: its fertile Vertisol soils (<5% of national territory) face salinization (12% of irrigated land) and encroachment by Sahara sands (1–3 km/year southward). Sustaining this zone requires rehabilitating SOC through agroforestry and expanding climate-resilient infrastructure to buffer against rainfall volatility.

Mauritania’s arid landscape, worsened by climate change-driven droughts and floods, has put nearly 365,000 people at risk. During the lean season, about 880,000 faced severe food insecurity, with over 80,000 children suffering from acute malnutrition.

Malnutrition is particularly severe among children and pregnant women, with high rates of stunting and wasting. The arrival of Malian refugees has further strained already limited food and health systems.

Mauritania continues to face interconnected challenges of food insecurity, malnutrition, and limited access to healthcare, especially in rural and vulnerable areas. Access to healthcare is weak, especially outside urban centers, due to poor infrastructure, limited resources, and staff shortages. Maternal and child mortality rates remain high. Addressing these complex issues requires coordinated humanitarian and government responses that strengthen food systems, expand nutrition services, and improve healthcare delivery for long-term resilience and equity.

Mauritania’s paved highways mainly connect Nouakchott to major economic hubs, but infrastructure gaps in the interior force reliance on informal transport and livestock-based mobility, leaving some regions vulnerable to isolation during extreme weather events.

Informal and semi-formal transport routes, with Nouakchott as the main hub, connect urban and peri-urban areas, but rural coverage is sparse, limiting accessibility for remote communities, especially those with seasonal migration patterns. Public transport is most available in cities and along trade corridors, but drops sharply in rural regions, deepening the mobility gap and restricting rural access to markets, healthcare, and education.

Mauritania’s railway, dominated by the Zouérat-Nouadhibou iron ore corridor, is crucial for economic mobility but offers limited passenger services, leaving most people reliant on roads and informal transport.

Mauritania’s airport network is concentrated around Nouakchott and key regional centers, reflecting the country’s reliance on air travel for long-distance mobility due to vast desert expanses. Limited connectivity outside major hubs highlights the need for regional air links to support economic and humanitarian efforts.

Data Source - https://nextgis.com/

Seasonal rivers (wadis) and the Senegal River define water accessibility, with critical implications for settlement patterns and mobility. As climate change alters rainfall patterns, water scarcity increases pressure on urban migration and conflicts over resources in semi-arid regions.

Mauritania’s transport infrastructure is sparse and primarily focused on extractive industries. The rail network is dominated by a single 704 km freight line transporting iron ore from Zouérat to the coastal port of Nouadhibou, with minimal provision for passenger services. The road network spans approximately 3,000 km of paved roads, but the majority of routes—especially in the interior—remain unsurfaced or poorly maintained, hindering reliable overland mobility.

Key international road corridors, including the Cairo-Dakar Highway and the Trans–West African Coastal Highway, connect Mauritania to regional trade and migration flows across North and West Africa. Air travel serves as a vital alternative, especially for accessing remote areas, with Nouakchott as the central hub. However, public transit remains limited and informal, concentrated around urban centers and often inaccessible to rural populations, reinforcing inequalities in mobility and access to essential services.

Zebeeb Nuguse Yana Buchatska

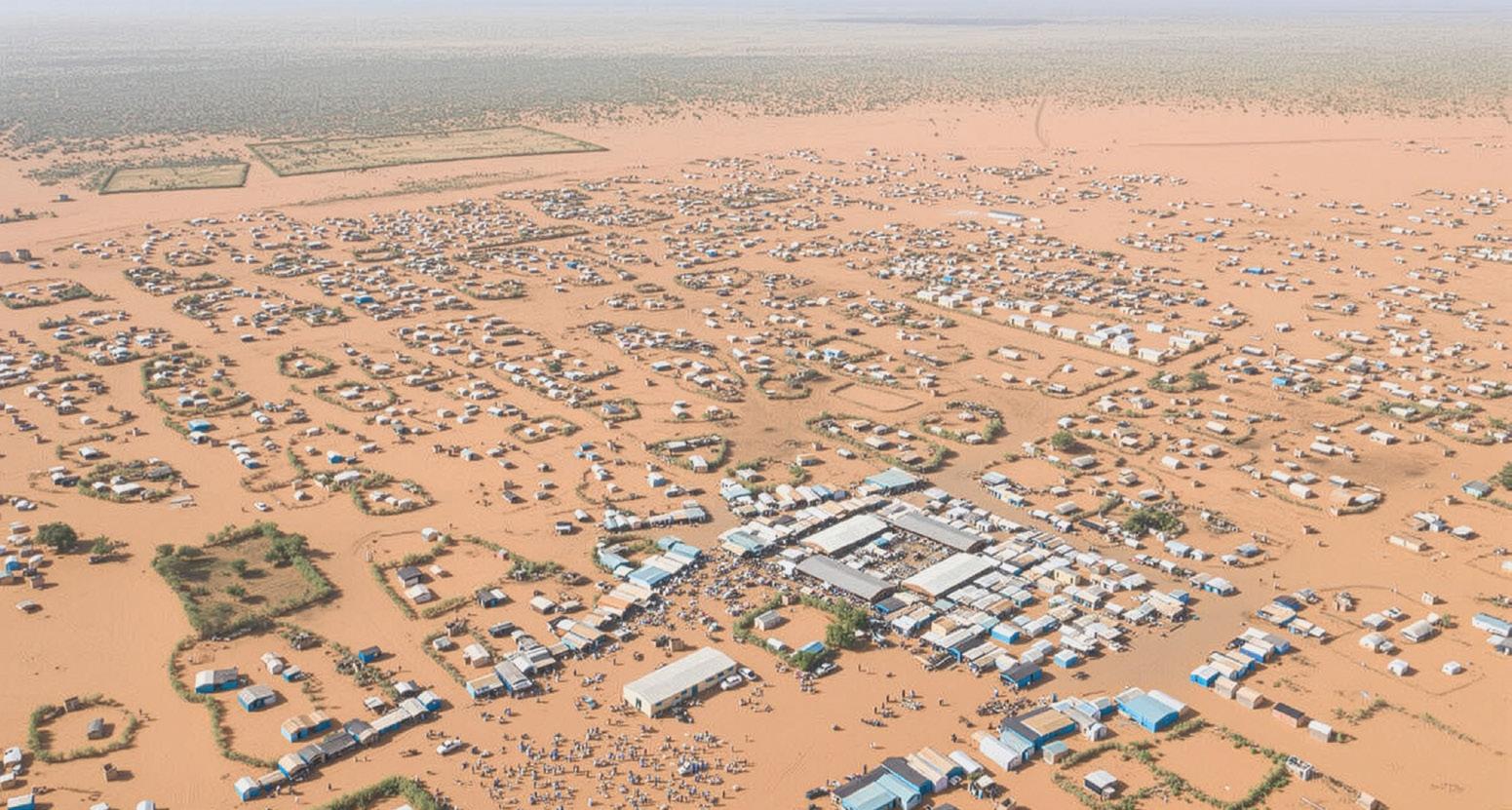

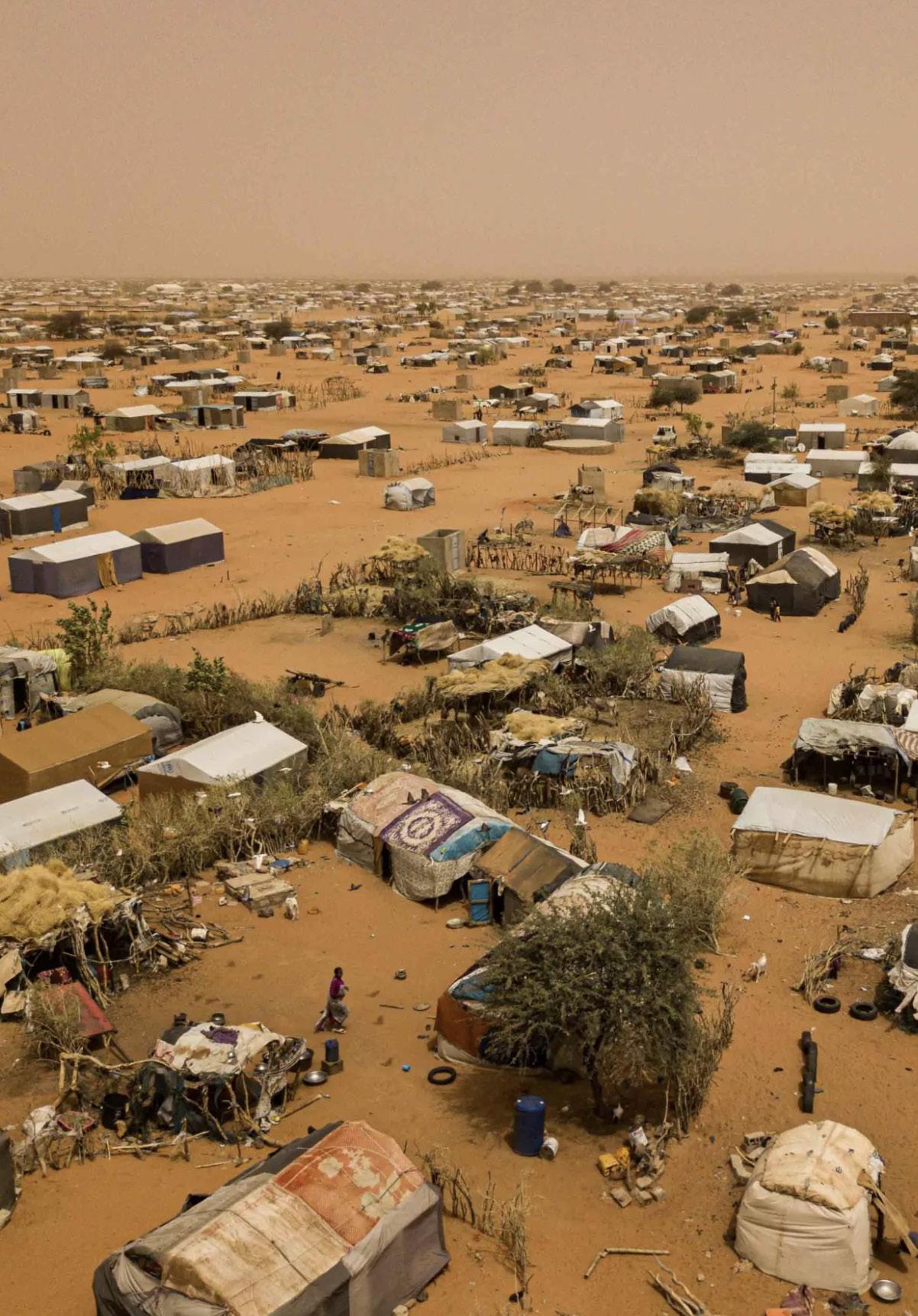

Mbera Refugee Camp, located in southeastern Mauritania near the Malian border, is one of the largest refugee settlements in the Sahel region. Established in 2012 to accommodate those fleeing conflict in northern Mali, the camp is situated in the Hodh El Chargui region, a semi-arid area characterized by limited infrastructure and scarce resources.

Over the years, it has evolved into one of the largest refugee camps in the Sahel region, housing tens of thousands of people displaced by violence and instability. The camp is situated in a remote, semi-arid region with limited natural resources and infrastructure, making humanitarian assistance essential to sustaining its population.

Initially set up as an emergency response to a sudden influx of refugees, the camp has transitioned into a more stable settlement. Efforts have been made to improve living conditions and promote long-term resilience among residents. These include the introduction of vocational training programs, incomegenerating activities, and access to education and healthcare services. Such initiatives have enabled many residents to develop skills, form cooperatives, and engage in small-scale economic ventures, gradually moving toward greater selfreliance.

Mbera has shifted from a temporary refuge to a protracted settlement, reflecting the complex, long-term nature of displacement in the region and the need for integrated, durable solutions that address both immediate needs and future opportunities.

Mbera Refugee Camp was established in 2012 in southeastern Mauritania, approximately 50 kilometers from the Malian border, to provide shelter for individuals fleeing the outbreak of conflict in Mali. As the security and humanitarian crisis in Mali continued, the region of Hodh Chargui accepted more Malians in the coming years, particularly in the Mbera refugee camp.

By 2022, the camp hosted nearly 80,000 people, making it one of the largest refugee settlements in West Africa. The following year saw a sharp increase in new arrivals, as the security situation in Mali deteriorated further. In 2023, Mauritania received over 55,000 displaced persons, with approximately 14,000 settling in Mbera camp. This brought the camp’s population close to 100,000, far beyond its original design capacity. By September, the camp’s population was estimated at around 110,000. This strain has led the majority of new arrivals to settle in neighboring villages.

Infrastructure and services in Mbera camp are under strain. The camp was initially built to support around 70,000 people, and overcrowding has led to shortages in essential services such as schooling, water access, and sanitation. Despite efforts by NGOs and multilateral systems, the scale of need continues to exceed available resources.

Kernel Density Analysis

0.001 - 18,603,224

Shelters Mbera Camp Blocks Zones Extension Zones

Source: UNHCR Site Mapping Data

According to UNHCR data, there are currently12,907 shelters in the camp.

The most densely built areas are in the oldest parts of the camp to the east. The densest administrative blocks include Zone 1 Blocks 1-2; Zone 2 Block 2, and Zone 3 Blocks 3 & 9.

Areas of lower density predominately include blocks in the west and north of the camp.

Shelters

Mbera Camp Blocks Zones Extension Zones

Source: UNHCR Site Mapping Data

Mbera camp is composed of 4 zones and 44 blocks.

While the data shows demarcated extension zones to accommodate incoming population, according to satellite imagery and report data, these areas are filled with shelters and the camp is nearly at capacity. Many refugees are settling in adjacent villages.

For incoming refugees who elect to stay at the camp, the best areas to absorb refugees via infill development would be the western zones of the camp with lower densities.

Status: Inactive

Storage

Waste Management

In 2023, Mbera camp had 11 water storage facilities and 7 boreholes (one out of service), providing reliable groundwater access with regular maintenance. Eight agricultural plots supported 375 farmers on 3.5 hectares (UNHCR/SOS Desert) and 60 farmers on 1.5 hectares using solar-powered irrigation (CIRC). Waste management included one facility outside the camp, rehabilitation of 65 drainage systems, and training for 44 water management teams.

To improve sustainability, UNHCR should expand solarpowered irrigation and integrate treated wastewater and organic waste from the nearby facility into agriculture, reducing aquifer dependence and enhancing food security.

Healthcare services in Mbera refugee camp face significant challenges due to limited resources and high population density. The camp’s healthcare infrastructure consists mainly of health posts and nutrition centers, strategically placed so that most residents are within a one-hour walk of care. While this layout ensures basic accessibility, the system is frequently strained by overcrowding, especially as the camp population grows or during seasonal surges in medical needs.

These pressures make it increasingly difficult to provide adequate care for vulnerable groups, such as pregnant women and young children, and highlight the urgent need for expanded capacity and resources to meet rising healthcare demands.

Depths of wells in the region of Hodh El Chargui are generally deep in comparison to the rest of the country (ranging from ~50 - 120 meters). This is because groundwater table depth is high - deeper than 40 metres - causing less favorable conditions for groundwater extraction. High groundwater table depth requires high cost investments to drill deep wells with pumps that need constant maintenance.

Source - https://www.academia.edu/85230492/Groundwater_features_in_Hoedh_el_Chargui_Mauritania?uc-sb-sw=24114700

However, significant variations are observed within the region with the depth of well equipment being especially high in the eastern sector of the Dhar Plateau. This includes the city of Bassikounou, Mbera refugee camp, and along the hydrology flow line leading to Mbera refugee camp. In these hotspots, wells between 90 and 120 meters are observed.

Mbera camp contains 2,748 total latrines, including 114 standalone latrines, 2,594 latrine-showers, and 40 wash stands. Latrine and washstand structures are more common along main streets on the older, eastern side of the camp.

According to UNHCR guidelines, the maximum distance between a household and a toilet should not exceed 50 meters in non-emergency contexts. 594 of the 12,907 shelters, or approximately 4.6%, fall outside this standard, indicating gaps in sanitation coverage in certain areas of the camp.

UN-WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) recommends 50 people per latrin in emergency circumstances and up to 5 households per latrine in basic circumstances. In 2023, the average ratio was 30 people per latrine, violating UN-WASH standards. Understandbly, Mbera camp officials struggle to lower and maintain this ratio. In 2023 alone, in response to new arrivals, 150 latrines were rehabilitated, an additional 17 emergency latrines were constructed, and 127 latrines were emptied to increase functionality.

Innovative, low-cost, and quick latrine solutions must be deployed across Mbera to ensure low latrine ratios, particularly in the western parts of the camp.

Distribution of 594 shelters outside of 50-meter buffer (4.6% of total)

Distribution of 594 shelters outside of 50-meter buffer (4.6% of total)

Distribution of 114 standalone latrines and 40 wash stands

50-meter buffer around sanitation centers

Distribution of 114 standalone latrines and 40 wash stands

Washstand only

Latrine Only Sanitation Centers

Shelters outside 50m

50-meter buffer

50-meter buffer around sanitation centers

Source: UNHCR Site Mapping Data

According to UNHCR guidelines, in non-emergency situations, the maximum acceptable distance between a household and a potable water source is 200 meters. Only 177 of 12,907 shelters (1.37%) are further than 200 meters from a water distribution source and violate UN-WASH standards. Almost all of these shelters are located at the outskirts of the camp. Therefore, new investments in water distribution sites should go towards ensuring that the needs of those at the western edge of the camp are addressed first.

In contrast, 6,607 of 12,907 shelters (51.19%) fall within a 50 meter radius of a water distribution point, allowing for excellent water access. Many of these are found in the older, more established eastern areas of the camp. 1,301 of 12,907 shelters (10.08%), households must walk more then 100 meters for access to potable water, signifying less-ideal water access.

As of 2023, on average, refugees in Mbera camp have access 15 liters of clean water per person per day. This is less than UN-WASH’s recommended standard of about 20 liters per day. However, this is mainly due to the influex of new refugees from Mali who keep arriving.

One crucial indicator this ratio misses is livestock, which could potentially mean that people are able to access less than 15 liters per person per day. Water distribution points should incorporate livestock to account for the region’s practice of transhumance pastoralism.

Shelters more than 200 meters away from a distribution point

Shelters more than 200 meters away from a distribution point

Shelters more than 100 meters away from a distribution point

Shelters more than 100 meters away from a distribution point

Shelters more than 100 meters away from a distribution point

50-100-150-200 meter buffers from all distribution points

50-100-150-200-meter buffers from all distribution points

Shelters more than 200 meters away from a distribution point 100 meters 50 meters 200 meters

50-100-150-200-meter buffers from all distribution points

Source: UNHCR Site Mapping Data

Canvas

poly-cotton canvas materials treated to be rot-proof, waterproof, and optionally fire-retardant

Plastic and metal sheeting

high-density woven polyethylene (HDPE) cores, coated on both sides with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) Fabric

presented as a coollage of stiched together various localy sourced textile pieces

Tent

poly-cotton cavas providedby UNHCR combined and extended by the refugees using locally available or salvaged materials

Prefabricated consist of the wall clading with sand bags, curved metal trusses covered with PVC truck tarpaulins Local materials made of various woven carpets from local dryed fibers, wooden sticks, diverse cloth and carpets

Shelter kits

ready-made shelter canvas tents provided by UNHCR

3. Systemic Integration

You now have a living system where:

• People and cattle feed the soil and bacteria

• Waste becomes a construction and regeneration material

• Trees and paths follow patterns of movement, gathering, and climate comfort

Social divisions and distance can cause further issues in the health and well-being of new arrivals, so connecting new refugees on the periphery is essential for optimal access to camp services. UNHCR or other NGOs can facilitate trainings and create a group of older refugees from various origins to walk new families through rules, resources, and local networks. Due to the size of the camp, neighborhood units can be devised and these teams can do weekly checks of the periphery to find new arrivals. The teams should be tasked with explaining food distribution, health services, school registration, and water access. Welcoming tents could be created for these teams on the outskirts as well to act as a base for these teams.

Inspired by Festival au Désert and the Ain Ferba Festival, a heritage festival could offer a meaningful space and time to bring together diverse forms of cultural learning and preservation.

The first phase could involve forming a steering committee made up of elders, women’s groups, UNHCR representatives, and youth. Women-led and youth-led subcommittees could focus on key areas such as workshops, festival programming, and documentation. Local artisans and musicians should be identified to perform and lead workshops.Partnership proposals could be developed for international collaborators—such as the Festival au Désert network, AFAC, UNESCO, the Prince Claus Fund, and private artists—to support financially and to connect to a larger audience.

In the second phase, workshops would serve as a means to preserve and transmit traditional knowledge and prepare for the festival. These might include women’s weaving workshops using traditional materials for tents, instrument making, and oral storytelling sessions conducted in native languages. The steering committee could determine a location for the festival that is accessible to residents of the camp. Professionals and specialists in these areas could be brought in from outside the camp to help train workshop leaders where needed.

The third phase would focus on the festival itself. Evening performances could feature music, storytelling, and dance from Fulani, Soninke, and Tuareg traditions. Locally made instruments and stage design could be showcased, along with artisan goods linked to weekly markets at Mbera and the MADE51 initiative. A youth media team could be trained to document the event through film and interviews, creating an archive to be shared digitally. Dedicated spaces such as a “Women’s Tent” and “Youth Corner” would support intergenerational dialogue, craft demonstrations, and storytelling. Trauma-informed arts and healing sessions, facilitated by trusted local women, could further connect cultural revitalization to psychosocial wellbeing.

Following the analysis of the Mauritania region—and Mbera Camp in particular—it is evident that the camp faces significant challenges due to extreme temperature fluctuations and a severely arid environment. These conditions create an urgent need for climate-adaptive infrastructure that can improve comfort and resilience for the camp’s residents.

One promising intervention is the introduction of multi functional sun-shading islands. These structures are designed not only to provide shade but also to serve as hubs for water harvesting, social interaction, and small-scale soil cultivation. In an environment where drought is inevitable, such solutions are essential to both immediate comfort and long-term sustainability.

The shading concept envisions modular frame structures covered with stretched fabric strips. These fabrics can be organically sourced and locally produced, making them both sustainable and culturally appropriate. As an alternative, woven panels made from local vegetation, such as dried leaves, roots, or plant fibers—can also be used to create the canopy. The supporting framework may consist of wide wooden beams reinforced with natural fiber ropes for added tension, or alternatively, long hollow bamboo poles that are lightweight yet strong.

Water harvesting is an integral part of this design. More advanced techniques might include the use of hygroscopic gels or salts, inspired by research conducted at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, which can extract moisture from the air. Simpler, low-tech solutions like the “water cone” system use solar heat to condense and purify water inside a dome-like structure. When scaled and integrated into the shading design, these systems can provide shaded communal areas that also function as cooling zones and drinking water collection points.

Bernd Riegert. (2024, April 11). EU approves new migration pact. Dw.Com. https://www.dw.com/en/eu-approves-newmigration-pact/a-68798172

Djibril Ndoye, Theresa Beltramo, Arthur Muhlen-Schulte, & Rakesh Gupta Nichanametla Ramasubbaiah. (2024, October 30). Understanding the new Malian refugees in Mauritania: A path forward amid growing challenges. UNHCR. https://www. unhcr.org/blogs/understanding-the-new-malian-refugees-inmauritania-a-path-forward-amid-growing-challenges/

Domenico De Luca. (2020). Groundwater features in Hoedh el Chargui, Mauritania. Acque Sotterranee - Italian Journal of Groundwater. https://doi.org/10.7343/AS-2020-481

Dr. Hassan Ould Moctar. (2024, October). ECRE Working Paper 21 – The EU-Mauritania Partnership: Whose Priorities? | European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). https:// ecre.org/working-paper-the-eu-mauritania-partnership/

Eve Conant (Author) & Matthew W. Chwastyk (Maps). (2015, September 19). The World’s Congested Human Migration Routes in 5 Maps. National Geographic. https://www. nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/150919-data-pointsrefugees-migrants-maps-human-migrations-syria-world

Federica Saini Fasanotti. (2024, October 16). The EU is alarmed by migrants from Mauritania GIS Reports. https://www. gisreportsonline.com/r/mauritania-migrant-eu-atlantic-route/

Finn, C. A., & Horton, J. D. (2015). Crystalline basement map of Mauritania derived from filtered aeromagnetic data (deliverable 54_1), Aeromagnetic and geological structure map of Mauritania (phase V, deliverable 54_2), Maximum depth to basement map of Mauritania derived from Euler analysis of Aeromagnetic data (phase V, deliverable 54_3), and color composite image of radioelement data (added value). In OpenFile Report (Nos. 2013-1280-B1). U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20131280B1

Frederik Steinhauser. (2024, August 5). EU-Mauritania Pact: Strategic Partnership to Tackle Illegal Migration and Geopolitical Challenges. European Studies Review. https:// europeanstudiesreview.com/2024/08/05/eu-mauritaniapact-strategic-partnership-to-tackle-illegal-migration-andgeopolitical-challenges/

Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (GMDAC), International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2024). Total number of international migrants at mid-year 2024 [International Data]. Migration Data Portal. https://www.migrationdataportal.org/ international-data

Hassan Ould Moctar. (2024, March 26). The EU-Mauritania migration deal is destined to fail. Al Jazeera. https://www. aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/3/26/the-eu-mauritaniamigration-deal-is-destined-to

Interaktive Anwendung „The Global Flow of People 2.0“ 1990-2020. (n.d.). Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.bib.bund.de/DE/ Fakten/Tools/Migration/Globalflows.html

International Monetary Fund. (n.d.). IMF Country Data— Mauritania. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://climatedata. imf.org/pages/country-data

Jason T. Dejong, Kenichi Soga, E. Kavazanjian, & S. E. Burns. (2025). Biogeochemical processes and geotechnical applications: Progress, opportunities and challenges. Geotechnique, 63(No. 4), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1680/ geot.SIP13.P.017

Jun Young Song, Youngjong Sim, Jaewon Jang, & Won-Taek Hong. (n.d.). Near-surface soil stabilization by enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation for fugitive dust suppression. Acta Geotechnica, 15(7). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-01900881-z

Kanta Kumari Rigaud, Alex de Sherbinin, Bryan Jones, Susana Adamo, David Maleki, Nathalie E. Abu-Ata, Anna Taeko Casals Fernandez, Anmol Arora, Tricia Chai-Onn, and Briar Mills. (2021). Groundswell Africa: Internal Climate Migration in West African Countries (p. 296). International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank. org/curated/en/453241634531082194/pdf/Groundswell-AfricaInternal-Climate-Migration-in-West-African-Countries.pdf

Liam Karr. (n.d.). Institute for the Study of War. Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www. understandingwar.org/backgrounder/africa-file-november2024-salafi-jihadi-areas-operation-sahel

Mann, G. (2021a). French Colonialism and The Making of the Modern Sahel. In L. A. Villalón (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the African Sahel (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198816959.013.9

Mann, G. (2021b). French Colonialism and The Making of the Modern Sahel. In L. A. Villalón (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the African Sahel (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198816959.013.9

Mauritania. (n.d.). UNHCR. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.unhcr.org/countries/mauritania

Mauritania | World Food Programme. (2025, March 27). https:// www.wfp.org/countries/mauritania

Mauritania Appeal | UNICEF. (n.d.). Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.unicef.org/appeals/mauritania

Mauritania Populated Places | Humanitarian Dataset | HDX. (n.d.). Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://data.humdata.org/ dataset/hotosm_mrt_populated_places

Migrants turn to Mauritania as new EU transit route. (2024, October 6). Dw.Com. https://www.dw.com/en/migrants-turn-tomauritania-as-new-eu-transit-route/a-69311885

N’Diaye, B. (2021). Mauritania: Exceptionalism and Vulnerability. In L. A. Villalón (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the African Sahel (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198816959.013.3

Observatoire du Sahara et du Sahel. (2017). Joint and Integrated Water Resources Management of the lullemeden—Taoudeni/ Tanezrouft Aquifer Systems and the Niger River (p. 26).

‘Panicked by the far right’, Brussels spends billions on migration control in West Africa. (2025, April 18). Africa Confidential. https://www.africa-confidential.com/article/ id/15434/%E2%80%98panicked-by-the-far-right’,-brusselsspends-billions-on-migration-control-in-west-africa

Teresa Nogueira Pinto. (2025, February 17). Farmer-herder tensions ignite across Africa. GIS Reports. https://www. gisreportsonline.com/r/farmer-herder-tensions-ignite-africa/

The Central Sahel: How conflict and climate change drive crisis | International Rescue Committee (IRC). (2023, August 17). https://www.rescue.org/article/central-sahel-how-conflict-andclimate-change-drive-crisis

Trabelsi, R., Zouari, K., Araguás Araguás, L. J., Moulla, A. S., Sidibe, A. M., & Bacar, T. (2024). Assessment of geochemical processes in the shared groundwater resources of the Taoudeni aquifer system (Sahel region, Africa). Hydrogeology Journal, 32(1), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-023-02688-5

UNHCR. (n.d.). Site Map—Mbera Camp. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://im.unhcr.org/apps/sitemapping/#/site/ MRTs004241/mapping

UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency. (2025). Sahel+ Global Apeal 2025 situation overview (Global Focus, p. 3). United Nations. https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/ Sahel%20Situation%20Overview.pdf

United Nations International Groundwater Resources Assessment Center. (n.d.). Transboundary Aquifers of the World. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://ggis.un-igrac.org/ view/tba/

United Nations Population Division. (2024). International Migrant Stock 2024. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/ content/international-migrant-stock

Walther, O. J., & Retaillé, D. (2021). Mapping the Sahelian Space. In L. A. Villalón (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the African Sahel (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198816959.013.8

World Bank Group. (n.d.). Climate Change Knowledge Portal—Mauritania. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https:// climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/

World Bank Group. (2023, June 27). Investing in Youth, Transforming Africa. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/ feature/2023/06/27/investing-in-youth-transforming-afe-africa World Food Program. (n.d.). Mauritania: Integrated Context Analysis (ICA), 2017 | Humanitarian Dataset | HDX.Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/wfp_ica_ mrt_2017

Spatial Design Strategies for Climate–and Conflict– Induced Migration

Course Instructor

Malkit Shoshan

Teaching Assistant

Spurty Kamath

Students

Xavier Ayub, Jules Bernstein, Kaitlyn Bell, Yana Buchatska, Mauricio Cohen Kalb, Luis Arturo Gomez, Spurty Kamath, Richard Kowel, Zebeeb Nuguse, Izzy Tice, Savalee Tikle, Tyler Vandenberg, Haozhuo Yang

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting

Chair

Ann Forsyth, Rachel Weber

Copyright © 2025 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2025 by their authors.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

This course review is supported by a Story Map with three sections: 1) Water, Landscape, and Agriculture in Arid Climates; 2) Infrastructure Recommendations for Mauritania; 3) Architectural Case Studies in Arid Climates, featuring student-collected case studies, design references, and additional reccomendations.

[Link: https://arcg.is/04C49q1]

Gratitude is extended to the external contributors who participated in lectures, workshops, and reviews, and generously shared data with us: UNPBF: Diane Myriam A Sheinberg UN Habitat: Mathias Spaliviero; UNHCR: Rakesh Gupta Nuchanametla Ramasubbaiah, Abdulaye Sy, Vasiliki Tsioutsiou; and IOM: Luísa Freitas

We also acknowledge the support of the 2025 Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative (HMUI) Urban Research Grant, which made this work possible.

Additionally, we thank Spurty Kamath, Savalee Tikle, and Yana Buchatska for their dedicated efforts in the final editing of this report.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design 48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Seminar Report

Spring 2025

Harvard GSD Department of Urban Planning and Design

Xavier Ayub, Jules Bernstein, Kaitlyn Bell, Yana Buchatska, Mauricio Cohen Kalb, Luis Arturo Gomez, Spurty Kamath, Richard Kowel, Zebeeb Nuguse, Izzy Tice, Savalee Tikle, Tyler Vandenberg, Haozhuo Yang