Developments in Vocational Education and Training

Selection of Texts by the National Team of Experts for Vocational Education and Training

Selection of Texts by the National Team of Experts for Vocational Education and Training

Selection of Texts by the National Team of Experts for Vocational Education and Training

Selection of Texts by the National Team of Experts for Vocational Education and Training

Lead editor of the Polish version Barbara Jędraszko

Cooperation

Aleksandra Bałchan-Wiśniewska

Translation Groy Translations

Proofreading

Lidia Przygoda, Artur Cholewiński, Bartosz Brzoza

Graphic design and typesetting Grzegorz Dębowski

Photography Szymon Łaszewski, Marianna Kulesza

Publisher Foundation for the Development of the Education System Polish National Agency for the Erasmus+ Programme and the European Solidarity Corps

Al. Jerozolimskie 142a, 02-305 Warsaw www.frse.org.pl | wydawnictwo@frse.org.pl

© Foundation for the Development of the Education System, Warsaw 2026

ISBN 978-83-67587-71-6

European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views of the authors only, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Free copy

Citation: Developments in Vocational Education and Training. Volume III (2026). Warsaw: FRSE Publishing

FRSE Publishing periodicals and portals

More publications from FRSE Publishing: www.czytelnia.frse.org.pl

of Vocational Qualifications Throughout the Careers of Graduates

Impact of Examination Centre Equipment on Education in Selected Occupations within

In April 2021, the Foundation for the Development of the Education System – the Polish National Agency for the Erasmus+ Programme and the European Solidarity Corps – launched the Team of Experts for Vocational Education and Training (EVET). Since then, its members have been appointed annually by the Ministry of National Education and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. In 2024, the team consisted of seventeen education specialists and six experts associated with higher education. They were educators, examiners, public officials, researchers, and academics working in various fields of vocational education, as well as representatives from the business sector.

T he work of the Team of Experts forms an integral part of the Erasmus+ programme’s Work Plan. The EVET Team focuses on improving the quality of vocational education and strengthening cooperation between sectoral vocational schools, technical secondary schools, and employers. These goals are achieved in close collaboration with institutions involved in implementing the Erasmus+ programme in the Vocational Education and Training and Higher Education fields, as well as through the Europass, Euroguidance, EPALE, and WorldSkills Poland initiatives.

E VET experts provide substantive advice to Erasmus+ programme beneficiaries and to institutions active in the field of vocational education in Poland. They advise on how to effectively use EU tools that support the mobility of vocational trainers, facilitate the recognition of skills and qualifications, and enable the monitoring of graduate outcomes in this sector. In addition, they participate in thematic events organised by the FRSE, including conferences, seminars, workshops, training sessions, lectures, debates, study visits, and analytical work. The results of the EVET experts’ work are presented in the form of publications and informational materials available on the website www.ekspercivet.org.pl. This book presents key articles developed by the members of the EVET Team in 2024.

Read on to learn more!

The Europass, Euroguidance and EVET Team Foundation for the Development of the Education System

Education sector (2024 appointees):

Piotr Bartosiak, Ministry of National Education

Lech Boguta, Ministry of National Education

Magdalena Wantoła-Szumera, Ministry of National Education

Katarzyna Ćwiąkała, Stanisław Konarski School Complex No. 2 in Bochnia

Joanna Górzyńska, Emilia Sukertowa-Biedrawina School Complex in Malinowo

Daniel Kiełpiński, Technical and General School Complex No. 2 in Katowice

Izabela Kierska, Medical Post-secondary School in Ciechanów Monika Ozga, Vocational and General School Complex in Lubań

Lucyna Parecka-Łaszczyk, Stanisław Staszic School Complex No. 1 in Płońsk

Magdalena Rzeszutko, Medical-Social Centre for Vocational and Continuing Education in Rzeszów

Paweł Salamon, Gastronomy School Complex in Gorzów Wielkopolski

Jędrzej Stasiowski, Educational Research Institute

Robert Wanic, Regional Examination Board in Jaworzno

Mieczysław Wilk, Technical School Complex in Mielec

Joanna Wiśniewska, General Władysław Sikorski Construction School Complex in Inowrocław

Dorota Wrzesińska, Stanisław Staszic Mining and Power Engineering School Complex in Konin

Magdalena Wyczańska-Jabłkowska, Wincenty Witos Agricultural Education Centre School Complex in Samostrzel

Higher education sector (2022–2027 appointees):

Maria Bołtruszko, Ministry of Science and Higher Education

dr hab. Jakub Brdulak, Professor of the SGH, SGH Warsaw School of Economics

dr Jacek Lewicki, SGH Warsaw School of Economics

dr hab. Lilla Młodzik, Professor of the UZ, University of Zielona Góra

dr Robert Musiałkiewicz, Professor of the PANS, State University of Applied Sciences in Włocławek

dr Katarzyna Olszewska, University of Applied Sciences in Elbląg

Jędrzej Stasiowski Educational Research Institute (IBE)

EVET expert, sociologist, analyst, member of the European expert network NESET, and an assistant in the Educational Research and Analysis Team at the IBE, where he is co-responsible for the development of the graduate tracking system for upper-secondary schools. His research interests cover labour market and education policies, vocational education, and issues in the field of the sociology of education. He specialises in designing social and evaluation research, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches, and in the analysis of educational and professional pathways.

dr Małgorzata Kłobuszewska Educational Research Institute (IBE) Economist, analyst, and researcher. She has worked on numerous projects carried out by the IBE and is currently co-responsible for the development of the graduate tracking system for upper-secondary schools. She specialises in the economics of education and the labour market. Her research interests also include the early careers of graduates, particularly from vocational schools. Author and co-author of reports and publications concerning investment in education and the educational and professional situation of graduates and young adults.

The demands of the labour market are constantly changing, which is why holding verified vocational qualifications has become essential for young people graduating from technical secondary schools and sectoral vocational schools. Following the post-communist transformation, one of the most significant milestones for vocational education was the 1999 educational reform. It introduced external examinations for vocational schools – initially in 2004 for students of basic vocational schools and from 2006 for students of technical secondary schools. Since 2012, individuals outside the school system have also been eligible to take these examinations. That same year, a new system was introduced that divided each occupation into specific qualifications. Students took examinations confirming their qualifications within an occupation, and those who collected certificates for all qualifications assigned to a given profession, and achieved the required level of education, were awarded a diploma confirming vocational qualifications. The 2017 reform brought further changes to the core curriculum, which were reflected in the examination itself.

For years, students of technical secondary schools and basic vocational schools – later replaced by stage I sectoral vocational schools (SVS I) – could complete their education without taking vocational examinations. Consequently, many graduates lacked formal confirmation of their skills, limiting their opportunities in the labour market. To address this issue, new regulations were introduced in 2019, along with an update to the core curricula, making it mandatory to sit the vocational examination as a condition for obtaining a school-leaving certificate. This change was intended not only to verify the quality of teaching but also to improve graduates’ employability. Students who pass the vocational examination in each of the qualifications distinguished within their occupation receive qualification certificates from the Regional Examination Boards (OKE). As in previous systems, obtaining all qualification certificates and the appropriate level of education entitles the graduate to receive a vocational diploma along with a Europass supplement. A diploma is an easily interpretable confirmation of graduates’ vocational skills for employers.

A diploma is an easily interpretable confirmation of graduates’ vocational skills for employers.

Around half a million vocational examinations take place in Poland each year, posing a considerable organisational and financial challenge. Graduates of technical secondary schools and SVS I who were not juvenile workers take examinations organised by the Regional Examination Boards, whereas juvenile workers who trained with craft employers take

journeyman examinations administered by chambers of crafts. The former obtain vocational diplomas, while the latter receive journeyperson certificates1

Passing the vocational examination requires considerable effort from students. In occupations comprising more than one qualification, a separate examination is held for each. The vocational examination consists of a written part and a practical part. To pass, a candidate must score at least 50% in the written section and 75% in the practical section. Only then may they receive a vocational diploma, issued by the Central Examination Board (CKE).

Before the examinations became mandatory, some students did not even attempt to take them. A 2012 study found that approximately 2% of basic vocational school students did not plan to sit the examinations because they felt they did not need them (Goźlińska & Kruszewski, 2013). A 2017 study yielded similar findings: around 2% of students from basic vocational schools and technical secondary schools indicated they would not take the examinations (Bulkowski et al., 2019). The most common reasons were a lack of intention to work in their trained occupation and the belief that they would fail the examination. In practice, the percentage of students who ultimately did not take the vocational examinations was even higher.

The mandatory requirement to take vocational examinations has likely contributed to a rise in the number of graduates obtaining a vocational diploma. Data from the tracking of upper-secondary school graduates’ careers – specifically SVS I graduates from 2022 – support this assumption. That year, the first graduates subject to the mandatory examination requirement left school. Among SVS I graduates (who were not juvenile workers), 66% obtained a vocational diploma, approximately 7% earned only a qualification certificate, and about 26% did not pass the vocational examination. In contrast, in 2021, as many as 37% of SVS I graduates completed their education without any formal confirmation of their qualifications or skills. This issue affected men (38%) more often than women (34%). The situation was better among graduates of technical secondary schools, yet 11% of them still did not obtain any qualifications. Here too, men (13%) fared worse than women (8%).

1 In the remainder of this text, we focus on graduates of stage I sectoral vocational schools (SVS I) who were not juvenile workers. In the case of juvenile workers, the statistics on the attainment of journeyman certificates are unfortunately understated. Despite a statutory obligation, only some chambers of crafts submit data on these certificates to the Educational Information System.

It is worth noting that by March 2023, around 20% of the 2021 technical secondary schools graduates had not yet obtained all the qualifications required for their occupation, holding only partial confirmation in the form of a qualification certificate. Graduate tracking data reveal clear differences across occupations in the share of graduates who successfully obtain vocational diplomas. Among SVS I graduates who were not juvenile workers, the percentage ranged from just 12% for motor vehicle mechanics to as high as 83% for confectioners. For technical secondary school graduates, the range was narrower – from 51% for IT technicians to 85% for hospitality technicians. Such disparities may stem from many factors: individual students’ abilities, different opportunities for practical training with employers, varying levels of motivation to work in the trained occupation, and the differing importance of diplomas across industries. Labour market demand for specific occupations within a given region, as well as broader economic conditions, may also influence these results.

From a theoretical standpoint, the significance of a vocational diploma in career development can be explained through two economic theories: human capital theory and signalling theory. Human capital theory posits that investing in education increases future employment prospects and earnings. According to this theory, employers make hiring decisions based on the full knowledge of a candidate’s skills, such as their level of education. Signalling theory, proposed by Michael Spence in 1973, assumes the opposite – that employers lack complete knowledge of a candidate’s skills and thus take risks when hiring. Candidates can increase their chances by “signalling” their productivity through credentials such as diplomas and certificates.

Given the certification function of vocational examinations, it can be assumed that SVS I and technical secondary school graduates who hold a vocational diploma have better prospects on the labour market than those without such confirmation. To verify this assumption, we can examine graduate tracking data. Since none of the SVS I and technical secondary school graduates completing education in 2021 were yet subject to the mandatory examination requirement, the presence of the vocational diploma in this group can be considered a reliable indicator of qualities valued by the labour market. This pertains not only to the level of practical vocational skills and theoretical knowledge but also to other valuable traits such as motivation, perseverance, learning ability, and intellectual aptitude.

The tracking data allow for an assessment of the professional and educational situation of 2021 graduates at two key points: in December 2021 (six months after graduation) and in December 2022 (18 months after graduation). We can distinguish four possible educational and professional statuses:

1) education only, i.e., continuing education without concurrent employment; 2) education and work, where employment is registered with the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS), signifying employment under contract or self-employment; 3) work only, where graduates are in any form of employment registered with ZUS and are not continuing their education; and 4) neither education nor work, which is either confirmed by ZUS data or indicated by a lack of any information about their professional activity. In addition, it is possible to analyse the duration of unemployment and periods of inactivity (neither working nor studying).

Graduates of stage I sectoral vocational schools

According to human capacity theory, employers make hiring decisions based on the full knowledge of a candidate’s skills, such as their level of education.

Among SVS I graduates who do not continue their education, having a vocational diploma clearly increases their chances of employment. Six months after graduation, 48% of graduates with a diploma were employed, compared to 43% in the group without a diploma or any certificates. After 18 months, the gap between them widened: 61% of diploma holders were employed, compared to 53% of those without one – an 8 percentage point advantage for those with a diploma. However, the situation for women was less favourable than for men. Six months after graduation, 40% of women with a diploma were employed, while in the group without a diploma, the figure was 35%. A year later, this difference widened: 47% of women with a diploma were employed, compared to 37% without one, increasing thegap from 5 to 10 percentage points. By comparison, among men with a diploma, the employment rate was 50% after six months, and 45% for those without one. After 18 months, 61% of men with a diploma and 53% of those without were employed. This means that the employment rate for men without a diploma was still higher than for women with one.

Graduates with a diploma and certificate were more likely to combine work and study, thereby broadening their career prospects. Among those without a diploma or certificate, combining work and study was less common, resulting in a lower employment rate (including those both working and studying) – by 3 percentage points in December 2021 and 6 percentage points in December 2022.

Graduates without a vocational diploma were also more likely to be not in employment, education, or training (NEET). Six months after graduation, as many as 43% of them were neither studying nor working; a year later, this figure fell by only 2 percentage points. In contrast, the percentage among diploma holders was significantly lower – 36% in December 2021, dropping more sharply by 5 percentage points over the following year. A particularly concerning finding is that for women without a diploma, the percentage of those not in work or education rose after a year (from 45% to 47%), while for men in the same group it fell (from 43% to 39%).

Analyses show that holding a vocational diploma reduces the length of NEET status, especially among SVS I graduates. Those without a vocational diploma spent an average of 9.8 months outside education or employment. For those who obtained a certificate but not a diploma, this period averaged 8.3 months, and for graduates with a diploma, it was even shorter – 8.1 months. Women were in a worse position than men: those without formal confirmation of their qualifications remained NEET for an average of 10.8 months, more than a month longer than men.

An analysis of wages among SVS I graduates shows a clear advantage for diploma holders. On average, they earned 10% more than those without one. This difference was particularly evident for men, where the wage premium for a diploma reached 12%, compared to 5% among women.

An analysis of wages among SVS I graduates shows a clear advantage for diploma holders. On average, they earned 10% more than those without one.

The final indicator worth considering is registered unemployment. After graduation, 15–17% of SVS I graduates registered as unemployed with the labour office; this percentage declined over time. Among them, the average duration of unemployment did not differ significantly between those who confirmed their qualifications and those who did not – it was approximately 2.6 months for both groups.

Over half of the graduates of technical secondary schools who did not continue their education were employed within six months of graduation. Among these, 60% of graduates with a vocational diploma were employed, compared to 53% of those who did not pass the vocational examinations. After 18 months (in December 2022), employment rates increased in both groups: to 68% among diploma holders and 61% among those with no qualifications. This means a 7-percentage-point advantage for those with a diploma.

As with SVS I graduates, those with a vocational diploma were more likely to continue their education. Six months after graduation, as many as 53% of them were still studying (with 12% combining education with work). A year later, in December 2022, this share rose to 58%.

By contrast, graduates of technical secondary schools without a diploma – whether lacking certificates altogether or holding only partial confirmation of qualification – were less inclined to pursue further education. In December 2021, 32% of graduates with no certificates and 34% of graduates with at least one certificate had entered further education; by December 2022, these figures rose to 35% and 38%, respectively. Graduates with a diploma were also more likely to have passed the matura exam (the national secondary school leaving examination). These are typically individuals with stronger educational outcomes and greater motivation for further study. Among women who passed the matura exam, as many as 86% also held a vocational diploma. In contrast, among women without the matura exam, 56% obtained the diploma, which constitutes a 30-percentage-point difference. A similar pattern was observed among men.

The greatest disparities appear among those neither in education nor employment. In December 2021, this group accounted for 19% of diploma holders, compared to 33% among graduates without a diploma – a 14-percentage-point gap. A year later, this percentage fell to 13% for diploma holders but remained high among those without one. It stood at 25% for graduates without any vocational examination and 22% for those with at least one qualification certificate.

Graduates of technical secondary schools without a vocational diploma remained inactive for an average of 7.4 months, while those who obtained certificates but not a full diploma spent 6.7 months in this situation. The shortest inactivity period was observed among diploma holders – an average of 5.0 months for men and 5.1 months for women. Wage analysis also confirms a clear, albeit smaller, advantage for diploma holders. On average, they earned 7% more than those without a diploma. Among men, the premium was 11%, only 2 percentage points higher than among women.

For technical secondary school graduates, around 13% registered with labour offices after graduation – a figure that, as with SVS I graduates, decreases over time. Diploma holders were unemployed for an average of 1.7 months, while those uncertificated remained unemployed for slightly longer, an average of 2.1 months.

When analysing the results of the graduate tracking, we employed more advanced statistical methods. This allowed us to determine which graduate characteristics increased the chances of finding employment and obtaining good wages. By controlling factors such as gender, age at graduation, and work experience gained during schooling, we can be surer of the positive relationship between obtaining a vocational diploma and young people’s situation on the labour market.

The evidence so far suggests that holding a vocational diploma is associated with better outcomes in both employment and wages. SVS I graduates who obtained a vocational diploma

had an approximately 7-percentage-point greater chance of finding a job six months after graduation. After 18 months, the chances for those with a diploma rose to 12 percentage points. In the case of graduates from technical secondary schools, we obtained a more optimistic result. It seems that having a vocational diploma not only increases the chance of finding employment (by approx. 8 percentage points compared to graduates without a diploma) but is also associated with higher wages.

Graduates of technical secondary schools who held a vocational diploma earned, on average, 7% more six months after graduation and about 10% more after 18 months than their peers who did not obtain any qualification certificate. Although work experience gained during schooling is initially very important for a graduate’s situation, its influence diminishes over time (within two years of graduation), while the positive effect of having a vocational diploma grows. Immediately after graduating from a technical secondary school, work experience in the form of an employment contract during schooling was associated with a 32 percentage point higher chance of employment and wages that were, on average, 35% higher than those of graduates without such experience. After a year, the advantage for these graduates was smaller (a 17 percentage point greater probability of employment and 18% higher earnings, respectively). A concerning finding here is, once again, the significantly worse situation for women, both SVS I and technical secondary school graduates. On average, they have a lower chance of finding employment (by 8 pp. for SVS I graduates and approx. 2 pp. for technical secondary school graduates in the first months after graduation) and also receive lower average wages (by as much as 18% and 15% in the first six months after completing education, for SVS I and technical secondary schools, respectively). However, by obtaining a vocational diploma they can improve their situation.

Graduates of both SVS I and technical secondary schools who obtain a vocational diploma are in a stronger position on the labour market than their peers without such documents. Those with a diploma are more likely to be employed and, in the case of technical secondary school graduates, more likely to continue their education. Diploma holders also spend less time registered as unemployed and experience shorter periods outside education or employment (NEET status). Moreover, their average wages – particularly among technical secondary school graduates – are higher than those of graduates who did not obtain this document. Although advanced statistical methods do not confirm a significant wage premium for SVS I graduates, they do indicate that holding a diploma significantly increases the likelihood of employment. To better determine the true wage premium associated with a diploma, more precise data will be needed. Further extensions of the graduate tracking system should allow for a more accurate estimation of this effect while accounting for other graduate characteristics that may determine their situation on the labour

market. Nevertheless, the preliminary findings presented here strongly suggest that it is worth encouraging students of both technical secondary schools and SVS I to prepare thoroughly for their vocational examinations. The diplomas they earn can significantly help them in building their future professional careers.

Bulkowski, K., Grygiel, P., Humenny, G., Kłobuszewska, M., Sitek, M., Stasiowski, J., Żółtak, T. (2019). Absolwenci szkół zawodowych z roku szkolnego 2016/2017. Raport z pierwszej rundy monitoringu losów edukacyjno-zawodowych absolwentów szkół zawodowych. [Vocational school graduates from the 2016/2017 school year. Report from the first round of monitoring the educational and professional careers of vocational school graduates]. Instytut Badań Edukacyjnych.

Goźlińska, E., Kruszewski, A. (2013). Stan Szkolnictwa Zawodowego w Polsce [The State of Vocational Education in Poland ] KOWEZiU.

Spence, M. (1973). Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87 (3), 355–374. Retrieved 27 November 2024, from: doi.org/10.2307/1882010

Katarzyna Ćwiąkała Stanisław Konarski School

Complex No. 2 in Bochnia

An EVET expert, a chartered teacher of vocational subjects for the occupations of surveying technician and renewable energy systems and equipment technician. A methodological advisor in the field of vocational education at the County Education Centre in Brzesko for teachers of sectoral vocational schools and technical secondary schools from the Bochnia, Brzesko, Dąbrowa, and Tarnów counties. She gained professional experience in photogrammetric companies and in surveying sales and service companies. She collaborates with the Central Examination Board (CKE) and the Regional Examination Board (OKE) in Kraków as an author and reviewer of examination materials. An examiner for the Regional Examination Board in Kraków in the occupation of surveying technician. A trainer supporting schools in developing learning skills shaped through experimentation, experience, and other student-activating methods. She received the title of Professional of the Year 2022 in the field of surveying. Her interests include issues related to lifelong learning.

Formulating educational requirements is a complex process that demands a precise approach. To develop an effective learning ‘roadmap’ for students, a teacher must clearly define the learning objectives and determine what skills and knowledge students are expected to acquire. A key element of this process is an analysis of the core curriculum, which allows the creation of requirements closely aligned with the intended learning outcomes. Clearly defined requirements not only support students in their development but also help teachers to monitor and assess their progress effectively.

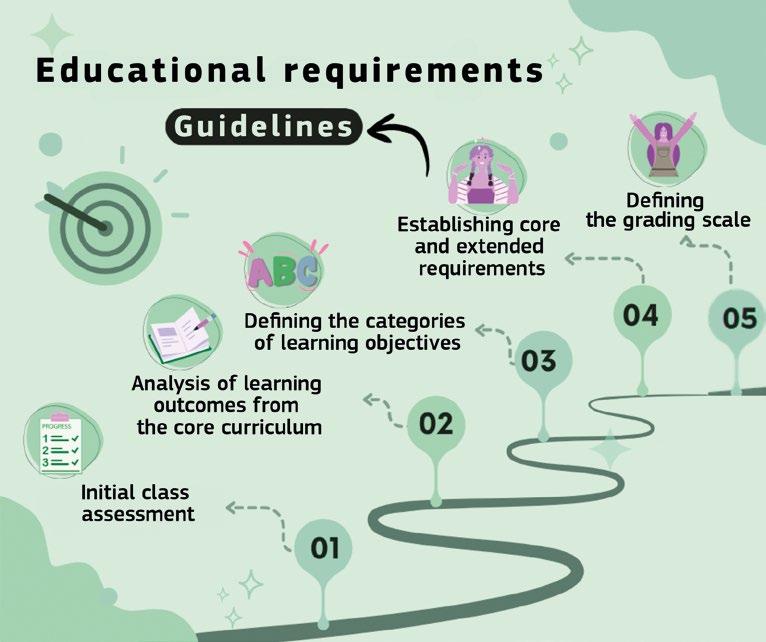

Figure 1. The process of formulating educational requirements

Source: author’s own elaboration.

The first step in formulating educational requirements is to conduct an initial diagnosis of the class unit’s needs. Before setting the requirements, the teacher should thoroughly assess the students’ current level, identifying both their strengths and the difficulties they may face. The results of this diagnosis can significantly influence the development or adjustment of the educational requirements and make it possible to tailor them to students’ needs.

The next step involves a detailed analysis of the learning outcomes specified in the core curriculum. At this stage, the teacher determines which skills and knowledge are essential for students when studying a particular subject within a given occupation. These learning outcomes are therefore the foundation upon which the entire teaching process is built, defining what students are expected to learn.

At this stage, it is useful to establish a taxonomy for the requirements set out in the core curriculum. Classification tools such as Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy (levels A–F) or Bolesław Niemierko’s taxonomy (levels A–D) can be used for this purpose. Teachers have the freedom to choose, as stipulated in Article 12(2) of the Teacher’s Charter, which states: “In implementing the curriculum, a teacher has the right to freely apply such teaching and educational methods as they deem most appropriate from among those recognised by contemporary pedagogical sciences, and to choose from among the textbooks and other teaching aids approved for school use”. A taxonomy helps assign appropriate levels of difficulty to particular educational activities. In Poland, Niemierko’s taxonomy is commonly used (see Table 1), dividing requirements into two main categories: knowledge and skills.

Both the structure of the taxonomy and its practical application are crucial for the correct formulation of educational requirements. Particular attention should be paid to the action verbs used in the taxonomy – e.g., 'name' (category A), 'explain' (category B), 'compare' (category C), 'evaluate, show differences' (category D) – as these help to define the level of difficulty of requirement.

Table 1. Bolesław Niemierko’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives with Action Verbs Useful in Defining Learning Objectives

Level I KNOWLEDGE

Category A Remembering knowledge

defining, describing, identifying, labelling, listing, associating, naming, tracing, reproducing, selecting, stating, naming, itemising, enumerating

Category B Understanding knowledge transforming, defending, distinguishing, estimating, explaining, generalising, giving examples, inferring, paraphrasing, predicting, summarising, rewriting in a new form, summarising, translating

Category C Applying knowledge in typical situations

changing, calculating, demonstrating, discovering, manipulating, modifying, operating, predicting, preparing, producing, relating, showing, solving, using, comparing, characterising, selecting a method, plotting, finding, applying

Level II SKILLS

Category D Applying knowledge in problem situations

Source: author’s own elaboration.

breaking down, diagramming, differentiating, distinguishing, identifying, recognising, illustrating, inferring, deducing, highlighting, determining relationships, selecting, excluding, dividing into smaller parts, predicting, detecting, evaluating, proposing, planning, proving, analysing, showing differences, categorising, compiling, composing, creating, devising, isolating, explaining, producing, modifying, organising, planning, processing, reconstructing, establishing relationships, reorganising, reviewing, rewriting in a new form, summarising, speaking, writing, appraising, comparing, concluding, describing, discriminating, explaining, judging, interpreting, relating, summarising, supporting

The table I have developed may assist in formulating educational requirements. It contains requirements from the core curriculum for the surveying technician occupation, which I teach, together with taxonomic categories (TC) that specify the level of complexity of the learning objectives. The table also includes the criteria for distinguishing levels of requirements, which are described below.

performs surveying calculations according to the Bradis-Krylov rules

lists and applies units of measurement in surveying

evaluates the accuracy and cartometric properties of cartographic and photogrammetric products

describes ways to prevent hazards present in the work environment

analyses data obtained from the land and building register

lists the sectors of the economy in which data from the register are used

calculates the scale of a map

plans a professional development path

analyses data obtained from the land and building register

explains what constitutes ethical conduct in the profession

names the surveying and legal documents related to the real property cadastre

distinguishes between types of maps

TC – taxonomic categories, ISV – intra-subject value, CSV – cross-subject value, U – usefulness.

Source: author’s own elaboration.

The process of formulating educational requirements should be well thought out, tailored to students’ abilities, and clearly linked to the learning outcomes of the core curriculum. It is important to distinguish between knowledge and skills and to use suitable taxonomic tools that facilitate the assessment and monitoring of student progress.

The next step is to define core and extended requirements. It is worth clarifying some common misconceptions regarding these terms, as it is often assumed that core requirements are those specified in the core curriculum, while extended requirements refer to additional content included in the teaching programme. This is not entirely accurate. Core requirements are those essential for practising a given occupation. They are mandatory for all students and cover the fundamental knowledge and skills that every student must master. Extended requirements, on the other hand, apply to students capable of meeting more advanced expectations – though, in the case of vocational subjects, there are relatively few.

intra-subject necessity – referring to the knowledge and skills that form the basis for learning a given subject (intra-subject value – ISV);

cross-subject necessity – resulting from the links between a given activity and the teaching content of other subjects (cross-subject value – CSV);

usefulness – expressed in present and future extracurricular activities, including the spontaneous application of elements in professional work (usefulness – U).

Example from the subject of surveying drawing

I have selected three educational requirements and defined their intra-subject value, cross-subject value, and usefulness in the workplace for each.

The student distinguishes between types of field sketches depending on purpose and on the method of planimetric or altimetric surveying

• intra-subject (ISV): +

• cross-subject (CSV): +

• usefulness (U): +

Interpretation: three ‘+’ signs indicate a core requirement.

The student prepares field sketches in accordance with legal regulations

• intra-subject (ISV): +

• cross-subject (CSV): +

• usefulness (U): +

Interpretation: three ‘+’ signs indicate a core requirement.

The student converts geocentric coordinates to plane rectangular coordinates and plane rectangular coordinates to geocentric coordinates

• intra-subject (ISV): +

• cross-subject (CSV): -

• usefulness (U): –

Interpretation: if there is at least one ‘–’ sign among the criteria (this usually applies to cross-subject value or usefulness), the requirement is classified as extended.

Let us return to the previously mentioned table, which contains the educational requirements from the core curriculum for my subject. Its second column specifies the categories of learning objectives (the taxonomic categories already referenced). Adjacent to this, we define the intra-subject value, cross-subject value, and usefulness to indicate whether the requirement belongs to the core (C) or extended (E) level. We therefore fill in four columns, leaving the last one blank.

performs surveying calculations according to the Bradis-Krylov rules

lists and applies units of measurement in surveying

evaluates the accuracy and cartometric properties of cartographic and photogrammetric products

describes ways to prevent hazards present in the work environment

analyses data obtained from the land and building register

lists the sectors of the economy in which data from the register are used

calculates the scale of a map

plans a professional development path

analyses data obtained from the land and building register

explains what constitutes ethical conduct in the profession

names the surveying and legal documents related to the real property cadastre

distinguishes between types of maps

TC – taxonomic categories, ISV – intra-subject value, CSV – cross-subject value, U – usefulness.

Source: author’s own elaboration.

Step 5. Defining the grading scale

At this point, the following information will be needed:

core requirements – for these requirements, the grading scale is: pass, satisfactory, and good. extended requirements – for these requirements, the grading scale is: good, very good, and excellent.

For both core and extended requirements, we select the lowest grade, which will be our starting point.

Now it is time for the taxonomic categories. In this case, we select the highest grade, which I have highlighted below.

As a reminder, we have already filled in the following in the table: column 1: the educational requirements; column 2: the categories of learning objectives (taxonomic categories – TC); columns 3–6: the intra-subject value (ISV), cross-subject value (CSV), and usefulness (U), which determine whether the requirement is at the core (C) or extended (E) level.

Now, in the column concerning the grading scale, you must: determine the requirement level (core – C or extended – E): based on the previously established level (core or extended), select the lowest possible grade; check the taxonomic category (TC): record the grade assigned to the taxonomic category, which is the highest possible grade in a given case, in the table.

Example

For a criterion that has been classified as a core requirement, the grading scale could be as follows:

Requirement: “The student distinguishes between types of field sketche”, Level: C (core) – we select ‘pass’ as the lowest grade, Taxonomic category: B – I select ‘good’ as the highest grade.

Once the final ‘Grade’ column is completed, the table will be ready to use in the subsequent stages of formulating educational requirements (see adjacent page).

On the following page, I present a fragment of the complete document setting out the educational requirements necessary for students to obtain specific mid-term and annual classification grades in the subject of surveying drawing for the first year of the surveying technician occupation.

To conclude, well-formulated educational requirements provide a solid foundation that supports both teaching and assessment. They enable teachers to align didactic methods more closely with students’ needs while giving students clear guidance on the objectives they are expected to achieve. Let us remember that effective education involves not only the transmission of knowledge but also the ability to assess it. Through a well-designed process for developing educational requirements, we support students’ development and enhance the overall quality of vocational education.

performs surveying calculations according to the Bradis-Krylov rules

lists and applies units of measurement in surveying

evaluates the accuracy and cartometric properties of cartographic and photogrammetric products

describes ways to prevent hazards present in the work environment

analyses data obtained from the land and building register

lists the sectors of the economy in which data from the register are used

calculates the scale of a map

analyses data obtained from the land and building register

names the surveying and legal documents

Thematic block 1: Drafting work in surveying. The student:

BUD.18.2. 8) Uses measuring instruments and drafting tools names drafting tools used in cartographic work distinguishes between measuring instruments used in surveying and cartographic work selects drafting tools to complete a task determines the functions and suitability of drafting tools for mapping on various map bases independently prepares surveying and cartographic documentation using drafting tools distinguishes between measuring instruments used in surveying and cartographic work lists drafting media for preparing cartographic works selects measuring instruments to perform a measurement on a map performs cartometric measurements on a map applies the principles of qualitative and quantitative generalisation of map content

1

Thematic block 2: Technical lettering. The student:

BUD.18.2. 6) Uses technical lettering when preparing field sketches defines the principles for describing surveying and cartographic documentation uses technical lettering when preparing graphic products

2

Thematic block 3: Cartographic symbols. The student:

BUD.18.2. 3) Recognises cartographic symbols –recognises standard cartographic symbols –reads cartographic symbols on the base map –draws basic cartographic symbols –draws cartographic symbols –distinguishes the colour scheme of cartographic symbols –discusses the rules for annotating features on the base map –independently draws cartographic symbols as specified in the regulation –applies descriptions and the colour scheme of symbols interprets the descriptions of cartographic symbols independently prepares surveying and cartographic documentation using cartographic symbols and object descriptions with the help of computer software for map creation

3

Source: author’s own elaboration.

Harmin, M. (2018). Jak motywować uczniów do nauki? Centre for Citizen Education. Lucas, B. (2022). Nowe spojrzenie na ocenianie w edukacji. Czas na zmiany. Centre for Citizen Education.

Niemierko, B. (2018). Jak pomagać (a nie szkodzić) uczniom ocenianiem szkolnym. Smak Słowa.

Olszowska, G. (2023). O!Cena w szkole. Nieodrobione lekcje (Od przepisów do sztuki oceniania)

Czerwona Kreska Foundation.

Olszowska, G. (2021). Oceniam, jak to łatwo powiedzieć. Meritum. Mazowiecki Kwartalnik Edukacyjny 2021, 1(60). Retrieved 12 November 2024, from: archiwum.meritum.edu.pl/artykuly/ index?page=32&sort=tytul

Pociecha, J. (2023). Wykłady dotyczące oceniania i konstruowania wymagań edukacyjnych.

Materiały dydaktyczne County Education Centre.

Regulation of the Minister of National Education of 22 February 2019 on the assessment, classification and promotion of students and course participants in public schools, Dz.U. [Journal of Laws] of 2019, item 347. Retrieved 8 November 2024, from: isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/ DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20190000373

Act of 7 September 1991 on the Education System, Dz.U. [Journal of Laws] of 1991, No. 95, item 425 as amended. Retrieved 8 November 2024, from: isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails. xsp?id=wdu19910950425

Act of 14 December 2016 – Education Law, Dz.U. [Journal of Laws] of 2017, item 59. Retrieved 8 November 2024, from: isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20170000059

Robert Wanic

Regional Examination Board in Jaworzno

An EVET expert, a graduate of the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at the Cracow University of Technology, specialising in heavy construction machinery. Since 1997, he has been a teacher at the Mechanical and Electrical School Complex in Sosnowiec. He has been working at the Regional Examination Board in Jaworzno since 2003, and has served as its director since 2016. He has served as an examiner for the occupations of mechanical technician, sheet metal worker, locksmith, and motor vehicle mechanic, and has reviewed textbooks for vocational education. He was an expert in the ESF project “Improving core curricula as the key to modernising vocational education”. Co-author of the publications Automotive Painter and Motor Vehicle Engines. In 2011, he was awarded the Medal of the Commission of National Education.

Vocational/sectoral education plays a key role in preparing students to enter the labour market. The centres where vocational examinations are held form an integral part of this process.

The vocational examination in Poland has evolved since 2004 and currently consists of two components: a written part and a practical one. The latter one is particularly important, as it assesses the skills essential for practising a given occupation. The model used for the practical examination has a significant impact on both the educational process and students’ practical skills, since it determines the equipment required at examination stations.

The practical part of the examination is conducted according to one of the following models:

‘d’ – where the sole outcome of the examination task is documentation;

‘dk’ – where the sole outcome of the examination task is documentation prepared using a computer;

‘w’ – where the outcome of the examination task is a product or service;

‘wk’ – where the outcome of the examination task is a product or service produced using a computer.

In the ‘d’ model, the candidate’s task is to prepare documentation related to a specific professional task. This may include a technical description, diagrams, plans, calculations, or other elements. The examination focuses on the ability to prepare precise and comprehensible documentation that could be used in real professional settings. An example of an examination based on the ‘d’ model is the qualification EKA.01 Customer service in administrative units in the occupation of administration technician 334306.

The latter part of the vocational examination is particularly important, as it assesses the practical skills that are essential for practising a given occupation.

The ‘dk model is a variant of the ‘d’ model, in which the documentation is prepared using a computer. It applies to occupations where the creation of documents such as technical drawings in CAD programs, the preparation of cost estimates using specialised software, etc., is of key importance. An example of an examination in the ‘dk’ model is the qualification MEC.09 Organisation and supervision of the production processes of machinery and equipment in the occupation of mechanical technician 311504.

Developments in Vocational Education and Training

The equipment required for this qualification exam consists of a computer connected to a printer, together with CAD software enabling the creation of a technical drawing and dimensioning in 2D space. The CAD software should allow drawing to be saved in DWG format, version 2010, for example, AutoCAD, BricsCAD, MegaCAD, LogoCAD, Solid Edge, SolidWorks, or ZWCAD.

In the ‘w’ model, the candidate performs a specific practical task at a prepared examination station, either an actual station or one replicating real working conditions. This model assesses the complete process of carrying out a task characteristic of the relevant qualification or occupation, requiring the candidate to work with the machines, tools, materials, and devices necessary for that trade. An example of an examination using the ‘w’ model is the qualification MEC.05 Operation of machine tools within the occupations of mechanical technician 311504 and machine tool operator 722307.

The equipment for this qualification includes, among other things:

a conventional machine tool (a lathe or milling machine), a numerically controlled machine tool (a CNC lathe or CNC milling machine), a workpiece storage unit, an inspection and measurement station.

Each of the models used in the practical part of the examination makes it possible to assess different aspects of professional competence, from manual and technical skills to precision in documenting processes and knowledge of tools.

The ‘wk’ model is similar to the ‘w’ model, but part of the examination task is performed on a computer, while the remainder takes place at an examination station equipped with machines, devices, and tools. This model applies to occupations where key skills involve software operation, design, and programming. An example of an examination based on the ‘wk’ model is the qualification MED.07 Assembly and operation of electronic devices and medical IT systems within the occupation of electronics and medical IT technician 311411.

The examination station for this qualification includes, among other things: a computer set with software; medical and IT apparatus, as well as control and measurement instruments such as a two-channel oscilloscope and a digital multimeter.

Each of the aforementioned models used in the practical part of the examination enables the assessment of different aspects of professional competence, from manual and technical skills to the precision in documenting work processes and proficiency in computer tools.

The first vocational examinations for graduates of basic vocational schools were held in 2004, and the first examinations for graduates of technical secondary schools took place in 2006. By design, examinations for graduates of basic vocational schools (now called BS I schools) were, and still are, conducted according to the ‘w’ model, at real or simulated examination stations that replicate actual working conditions. Graduates are required to demonstrate practical skills by ‘producing’ a product or providing a service. These examinations have always been conducted at examination centres authorised by the regional examination boards. Such facilities usually contain between three and six examination stations for a given occupation. The technical parameters of these stations must be consistent across the country, ensuring that the examination task can be performed at each of them. These tasks are uniform for all candidates pursuing the same occupation or qualification.

The equipment of examination stations, together with the examination model, particularly in the practical part, has had, and continues to have, a strong influence on the educational process. It also affects further training and self-education of teachers, practical vocational training instructors, and employers. Since 2004, the practical stage of the examinations has assessed skills in four areas of requirements: planning the activities required to perform the task, organising the workstation, performing the examination task in compliance with health and safety, fire protection, and environmental protection regulations, presenting the result of the completed task.

For occupations for which two topics were provided, the candidate would draw one of them before beginning the examination. They would then either draw again or be assigned to a specific examination station.

Below, I present examples of selected occupations where examination centre equipment significantly influenced the educational process.

In the occupation of salesperson 522[01] , two examination topics were specified: serving a specified type of customer at a stand in a given industry, using a designated form of sale; serving a specified type of customer in a wholesale warehouse in a given industry and with a specific degree of work organisation.

For the first topic, completing the practical stage of the task required, among other skills, the ability to operate a fiscal cash register. This came as a surprise to candidates and teachers in schools, and also posed a challenge to examiners. The first examinations revealed that a number of candidates struggled to perform the practical task, and the most common problems arose precisely when operating the fiscal cash register, resulting in low performance. Consequently, local governments equipped salesperson training workshops with fiscal cash registers, and training sessions were provided for both teachers and candidates.

For the occupation of automotive painter 714[03] , the examination standards required the presence of a certified spray booth of a size suitable for the dimensions of the painted elements or sub-assemblies. However, during the first examinations, it became apparent that very few schools or training centres in Poland possessed such equipment. In practice, this meant that, for example, students from the entire Silesian Voivodeship had to take the examination at the only appropriately equipped examination centre in the region, located in Mysłowice. Students, often accompanied by their teachers, travelled from afar to take the examination on equipment they were operating for the first time. This example illustrates how a lack of equipment in home schools can discourage candidates from sitting the examination, particularly when the only available centre is located far from their place of residence.

Similarly, for the occupation of chemical industry equipment operator 815[01] , the examination standards required a tank-type reactor used in organic industry processes (such as sulfonation, nitration, esterification), along with control and measurement instrumentation. For many years, students training in this field took the examination at the sole fully-equipped examination centre in Poland, located in Gliwice. Candidates travelled to this centre from as far as the area of the Regional Examination Board in Gdańsk.

A compelling example of how examination equipment influences the educational process is provided by the occupation of machine tool operator 722[02] In the first information guide published by the Central Examination Board (CKE) in Warsaw, the practical stage of the examination included two practical tasks/topics: performing specific technological operations on conventional machine tools in accordance with documentation; performing a specific technological operation on a numerically controlled machine tool in accordance with documentation.

However, a significant number of schools providing training in this occupation lacked numerically controlled machine tools or possessed only one type of CNC machine (either a lathe or a milling machine). Others relied solely on machine tool simulators. This shortage of modern equipment hindered students’ learning. During the first examinations, candidates who drew the second topic – requiring CNC operation – often withdrew from the practical part altogether. In 2012, the structure of vocational education changed. A division into qualifications distinguished within individual occupations was introduced, allowing students to acquire specific skills more flexibly. Students could obtain them by completing courses and passing examinations confirming their professional competence The core curriculum for the occupation of machine tool operator was revised accordingly, leading to changes in the examination process. The examination for the M.19 qualification, distinguished within the occupation of machine tool operator, required candidates to use both numerically controlled and conventional machine tools. Every candidate had to perform part of the task on two different machines (a so-called ‘transition’ between machines).

Further reforms followed with the introduction of the 2017 and subsequently the 2019 formula. The 2019 formula for vocational examinations in Poland, implemented under the Act of 22 November 2018, came into force on 1 September 2019, hence the name ’2019 formula’.

The practical part of the examination for candidates in the occupation of machine tool operator 722307 did not change significantly in terms of procedure, though the equipment requirements for examination centres were updated, specified in more detail, and expanded.

On 6 June 2024, the Regulation of the Minister of Education amending the regulation on the core curricula for sectoral school occupations and additional vocational skills in selected sectoral school occupations (Journal of Laws of 2024, item 993) was signed. As a result, the core curriculum for the occupation of machine tool operator – specifically the qualification MEC.05. Operation

of machine tools – was revised. This qualification is distinguished both within the occupation of machine tool operator and within that of mechanical technician.

The new regulation (Journal of Laws of 2024, item 993, Article 1(1a) contains the following provision: A graduate of a school providing training in the occupation of machine tool operator should be prepared to perform professional tasks within the scope of the MEC.05. Operation of machine tools qualification: preparing numerically controlled and conventional machine tools for planned machining; performing machining on numerically controlled machine tools in accordance with technological documentation.

This provision means that the practical part of the vocational examination will no longer include tasks involving conventional machine tools.

The equipment of an examination centre and the chosen examination model have a significant impact on the educational process in schools and practical training centres. The equipment required for each occupation/qualification is specified and published by the Central Examination Board in Warsaw, which issues detailed descriptions in a three-year cycle. Before each school year, the Board may introduce minor modifications to the existing specifications, highlighted in red. These changes are implemented only when necessary – for instance, to align with software updates or changes in trade names of equipment components. Descriptions of equipment for some qualifications may also include information on planned changes anticipated in the following three years.

The equipment requirements specified by the Central Examination Board affect several key areas:

a) the functioning of schools, practical training centres, and employers providing training in a given occupation or qualification

The publication of equipment lists is of crucial importance for sectoral schools, as it enables them to apply formally to local government units (LGUs) for financial resources to purchase the necessary equipment. Thus, these lists serve not only as guidance but also as the formal basis for funding applications.

Schools lacking appropriate equipment often find it difficult to collaborate with local employers, who may be reluctant to hire graduates without sufficient practical preparation. Conversely, schools that maintain modern, well-equipped training and examination facilities tend to gain prestige, attract more capable candidates, and achieve better educational outcomes.

Properly equipped schools and workshops provide teachers with access to modern machinery, tools, and technologies, enabling a more practical and interactive approach to teaching. This enhances student engagement and allows teachers to conduct mock examinations or simulations using the same equipment as that used in official assessments. This allows students to familiarise themselves with examination procedures. The introduction of new machines and equipment often necessitates training for teachers and instructors, allowing them to update their professional knowledge and adapt to evolving technologies and teaching methods.

c) students, vocational qualification courses (VQCs) participants, and individuals taking external examinations

Access to modern, industry-standard equipment allows students and VQC participants to learn using the same tools and technologies applied in the labour market. Candidates who train on identical or similar equipment to that used during the examination (and subsequently in their future work) experience less stress and are better prepared to pass it. Consequently, graduates who have had the opportunity to train and work on modern equipment are more attractive to employers, as they can contribute effectively from the outset of their careers. This significantly increases their chances of finding a job quickly after graduation.

The equipment of an examination centre and the chosen examination model have a significant impact on the educational process in schools and practical training centres.

d) vocational examinations results

A lack of appropriate equipment in schools can have serious negative effects on examination results, especially in fields where practical skills are decisive. Students unfamiliar with the examination equipment may feel insecure and stressed during the assessment, which can lead to errors stemming from inexperience rather than lack of knowledge. This increases the risk of failure, which may, in turn, affect their future careers.

The introduction of a new occupation into the classification of sectoral school occupations should be carefully planned, especially regarding the specification of required equipment and the examination model. The correct and prudent specification of equipment for education and examinations, following a thorough analysis of the labour market and consultations with employers and representatives of higher education institutions, will have a very significant impact on student recruitment for training in new occupations.

Regulation of the Minister of National Education of 28 August 2019 on the detailed conditions and method for conducting the vocational examination and the examination confirming qualifications in an occupation, Dz.U. [Journal of Laws] of 2019, item 1707, as amended. Retrieved 8 November 2024, from: isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20190001707

Regulation of the Minister of Education of 6 June 2024 amending the Regulation on the core curricula for education in sectoral school occupations and additional vocational skills in selected sectoral school occupations, Dz.U. [Journal of Laws] of 2024, item 993 Retrieved 8 November 2024, from: isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails. xsp?id=WDU20240000993

Act of 7 September 1991 on the Education System, Dz.U. [Journal of Laws] of 2022, item 2230, as amended. Retrieved 8 November 2024, from: isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails. xsp?id=WDU20220002230

Developments in Vocational Education and Training

Lucyna Parecka-Łaszczyk

Stanisław Staszic School Complex No. 1 in Płońsk

An EVET expert, Professional of the Year 2022 in the hairdressing category, awarded the Medal of the Commission of National Education. A teacher of vocational hairdressing subjects using the ICT method. Author of many award-winning pedagogical innovations and publications in hairdressing trade journals. Co-organiser of initiatives promoting vocational education and cooperation with employers. A speaker, trainer, and consultant at events related to vocational education, promoting WorldSkills trade competitions, and presenting modern methods of working with students, as well as career paths. She actively supports beneficiaries of the Erasmus+ programme.

Joanna Górzyńska

Emilia Sukertowa-Biedrawina School Complex in Malinowo

An EVET expert, a vocational education teacher (glass industry, environmental protection), and a county coordinator for career guidance. An examiner for the vocational examination in the occupations of glass industry equipment operator and glass technology technician. A reviewer of vocational education textbooks. An expert in teacher examination and qualification boards. A trainer and instructor in the field of vocational education and career guidance. An expert in numerous projects concerning vocational education and career guidance. She combines the work of a teacher and a guidance counsellor, promoting the idea of education-market partnerships.

Daniel Kiełpiński

Technical and General School Complex No. 2 in Katowice

An EVET expert, a vocational subjects teacher, and an examiner in the occupations of electrical technician, power engineering technician, automation technician, and mechatronics technician. An energy auditor. A member of the Management Board of PTP Muzeum Energetyki in Łaziska Górne and a guide. An expert and mentor in Climathon 2021 in the “How to effectively save energy in the city?” edition. Awarded the title of Professional of the Year 2022 in the field of power engineering. Recognised for his activities for environmental protection by the WFOŚiGW in Katowice on the occasion of Earth Day in the Green Cheques competition, in the “Ecological Personality of the Year” category for developing original workshop and educational programmes aimed at changing habits and promoting energy conservation for the sake of the environment.

Today, vocational education is becoming a path to success for young people with passion. It plays a vital role in preparing them for employment and in meeting the economic needs of both the regions and the country. The task of schools, and in particular their teachers, is to recognise and awaken the passions and interests of their students. Education is a collaborative process in which the role of teachers is crucial, yet students’ success ultimately depends on themselves. By observing and speaking with them, we can often identify their strengths and weaknesses, as well as their desire to grow and uncover hidden talents. Getting to know our students allows us to propose various forms of personal development. One such form of support is encouraging them to take part in skills competitions.

The Championships of Young Professionals, as the WorldSkills and EuroSkills competitions are known, are held alternately every two years. This initiative brings together young people, industry, and teachers, giving participants the chance to compete, gain experience, and learn how to excel in their chosen professions. It also allows them to showcase their skills in a range of technical and craft-based fields. The aim of the competition is to promote and develop vocational skills among young people, raise the standards of vocational education, enhance the prestige of technical and craft-based occupations, and create a platform for effective cooperation between business and vocational training providers. It is aimed primarily at students of vocational and technical secondary schools, as well as young professionals who wish to stand out in their industries. Participation in this programme offers an opportunity not only to test one’s skills at a national level but also to gain international recognition.

The competitions consist of several stages:

SkillsPoland regional qualifiers: This is the first and key qualification stage. They are organised in different parts of Poland to select the best participants in each vocational category. Eligible competitors include both students and professionals aged 18–25. The regional competitions include both theoretical and practical tasks that reflect real challenges participants may encounter in their work. Each competitor must therefore demonstrate both technical knowledge and manual skills.

SkillsPoland national finals: Winners of the regional competitions advance to the national finals, where they compete against the best participants from across Poland. These finals are held at a higher level of difficulty and require full commitment and mastery of the relevant techniques. The national finals are not only a competition but also a valuable learning experience that can benefit participants’ future careers.

EuroSkills and WorldSkills: The best participants from the national finals are selected to represent Poland internationally at EuroSkills (European) and WorldSkills (global). These

are the most prestigious contests for young professionals worldwide, held in different cities around the globe and often compared to the Olympic Games.

Vocational skills competitions help raise the standards of vocational education while providing participants with numerous benefits, including faster career development, industry networking, and knowledge exchange. WorldSkills winners are often recruited by renowned companies and organisations, and their titles can open doors to prestigious positions within their sectors. Through collaboration with top specialists from Poland and abroad, participants can develop their skills, while teachers and educational institutions can adapt their curricula to international standards.

The first person to notice a student’s potential is often a teacher or internship supervisor. They are best placed to assess how far students can develop their talents, prepare for a profession, or acquire other industry-specific competences. Bearing this in mind, teachers select the most suitable teaching aids and tools to prepare learners, course participants, or university students for professional work. Formally, those engaged in vocational education aim to obtain a diploma, a certificate confirming their qualifications, or documentation proving completion of a course in a given field. However, teachers can also draw students’ attention to additional training opportunities. Vocational competitions for specific industries – such as WorldSkills – can be a valuable complement to formal education, although their importance will vary for each participant. Supporting talented students as they overcome initial hesitation, discussing competition rules, and assisting with registration will certainly help students overcome initial difficulties.

The participation of students or graduates in global vocational skills competition also offers a range of benefits for teachers. Here are the top ten:

1. increased professional prestige and authority,

2. development of teaching competences,

3. access to modern technologies and materials,

4. motivation for further work,

5. improved prospects for professional career development,

6. development of a professional network,

7. becoming a source of inspiration and a role model for other students,

8. the opportunity to participate in international events,

9. enhanced school reputation,

10. better teaching outcomes.

Participation in olympiads and competitions is also a mark of distinction for educational institutions and companies. Those that can boast competition achievements often gain excellent opportunities to promote their work within specific industries.

In turn, young people who win medals at WorldSkills become ambassadors for their occupations. Their success shows that careers in technical and craft-based industries can be not only profitable but also fulfilling and prestigious.

For a vocational teacher, the assessment system used in these competitions is of particular interest.

Competition tasks, compared with those in vocational qualification or a journeyman examination, are significantly more extensive and take place over a longer period. This raises an important question: what skills are assessed during SkillsPoland, EuroSkills, and WorldSkills?

The jury pays particular attention to precision. Tasks are designed to require flawless execution, both technically and aesthetically. Participants are also assessed on their speed of work while maintaining high-quality results. In addition, competitors must demonstrate the ability to solve problems they might encounter at work, applying both their experience and analytical thinking. Due to the wide range of competition areas, some events also require knowledge of modern technologies, including mechatronics, robotics, or IT. To become a WorldSkills champion, and a leader in their field, participants undergo rigorous training to raise their skills to a world-class level. These intensive preparations are supported by top experts and mentors from the given industry, who help them solve complex tasks. Achieving success at WorldSkills requires not only commitment but, above all, passion for one’s occupation.

The participation of young people in regional SkillsPoland competitions is supported by various public entities, among which industry employers play a crucial role. In the modern world, the rapid growth of knowledge, digitalisation, automation, and technological development should encourage enterprises to cooperate with schools and to undertake joint initiatives that help create a positive image of vocational education aligned with labour market needs. Responsible employers should cooperate with schools, teachers, and students by supporting training preparation, providing competition equipment, and contributing to the creation of industry clusters. The integration

of these activities can raise the quality of education, attract and retain top talent, and offer young people a gateway to successful careers.

Vocational education and the WorldSkills competition are closely linked, as they both aim to promote and develop practical skills while supporting young people in acquiring competences that are essential in the labour market. WorldSkills serves as an international platform that not only recognises outstanding young professionals but also highlights the importance of vocational education in global economic development. As a result, vocational training becomes a key factor in shaping the future of industry, technology, and innovation.

In many countries, these competitions are an integral part of the vocational education system, motivating students to refine their skills. Institutions that prepare students for WorldSkills must align their curricula with current industry standards. This ensures that students receive world-class education, enhancing their competitiveness in the labour market. Cooperation between schools and entrepreneurs is also important, as it leads to the creation of curricula that are better tailored to industry needs. Consequently, graduates of vocational and technical secondary schools are better prepared to work in modern sectors of the economy.

Another significant element linking vocational education with WorldSkills is student motivation. High-level competition and the possibility of gaining international recognition encourage students to improve their skills continuously. It can also open many doors to employment, internships, and even global careers. The competitions reflect the latest market trends and demands, including automation, sustainable development, and digitalisation. Therefore, WorldSkills may be regarded as a barometer of technological and economic change. Vocational education must adapt to these transformations to prepare students for future challenges.

In many countries, WorldSkills competitions are viewed as a tool for supporting reforms in vocational education. By raising standards, providing inspiration, and building awareness of the importance of technical professions, the WorldSkills initiative exerts a real influence on vocational schooling. Through cooperation between industry, government, and teachers, it creates a global skills platform available to all

The most important goal of vocational education is to equip graduates with the right skills and competences. Hard skills (technical and specialised) include: knowledge of technologies and work tools: a graduate should understand the tools and technologies used in their industry, such as programming, specialised software, analytical tools, or machinery; knowledge of foreign languages: in the age of globalisation, knowledge of at least one

foreign language, most often English, is crucial. Other languages are also increasingly valued, depending on the region and sector; ability to work with data: skills in analysis, interpretation, and appliance of data in decision-making are increasingly sought after; certificates and specialised training: confirmation of one’s competences by completing training and obtaining industry certificates (e.g., programming certificates in IT, accounting certificates in finance).

As for the soft skills (interpersonal and social), they include: communication: a graduate should be capable of effective communication, both written and oral. It is important to convey information in a clear and precise manner; teamwork: the ability to cooperate in a group, understand different perspectives, and effectively carry out team tasks is crucial in many occupations; adaptability: the labour market is changing rapidly, so the ability to adapt to new conditions, technologies, and tasks is of significant importance; creativity and innovation: companies value individuals who can propose new, innovative solutions and are open to new challenges; problem-solving skills: a graduate should possess analytical skills and think critically. This enables them to solve problems in the workplace effectively.