ARTIFICIALLY INTELLIGENT PSYCHOLOGY

Language as Robots in Machines, Organisations, and Humans

Jan Ketil Arnulf

ARTIFICIALLY INTELLIGENT PSYCHOLOGY

ARTIFICIALLY INTELLIGENT

PSYCHOLOGY

Language as Robots in Machines,

Organisations, and Humans

Jan Ketil Arnulf

Copyright © 2025 by Vigmostad & Bjørke AS All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2025 / Printing 1 2025

ISBN: 978-82-450-6036-2

This book was translated with the support of AI-assisted tools under the supervision of Jack F. Sharp. The author reviewed and ensured the substantive accuracy and overall quality of the translation.

Graphic production: John Grieg, Bergen

Cover design: Thalia Soline Arnulf based on a photograph by Jan Ketil Arnulf

Enquiries about this text can be directed to: Fagbokforlaget Kanalveien 51 5068 Bergen

Tlf.: 55 38 88 00 e-post: fagbokforlaget@fagbokforlaget.no www.fagbokforlaget.no

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Vigmostad & Bjørke AS is Eco-Lighthouse certified, and the books are produced in environmentally certified printing houses.

Foreword

Start by Upgrading Your Own Brain

If you are able to read this, you are already “artificially intelligent”. You have uploaded cultural software that lets you turn letters into language and make sense of what’s written here. Your brain does not do this all by itself. That miraculous organ between your ears is merely a complex host organism that allows you to take part in the cultural evolution of reading and writing the English language. If you find that idea interesting, provocative, or even a little strange, then this book may be right for you.

Conversely, if you are worried about being controlled by artificial intelligence, I hope you will find plenty to chew on in the pages ahead. After all, while humans often try to control one another in various ways, it is only machines that are truly predictable – and thus controllable. This book is intended to guide you on a journey through the borderland between controllable machines and unpredictable organisms. On this journey, you may discover that intelligence is not quite what you thought it to be.

The book is also an invitation to explore how language, brain, and culture connect with artificial intelligence. It is written for anyone curious about how digitised language models are intertwined with the psychology of work and organisations. At its core, the book is about what large language models and socalled “generative artificial intelligence” mean for psychology in general, and organisational psychology in particular. The

goal is to offer the reader a set of systematic insights that allow the human brain to join the journey AI is inviting us on. I hope to spark interest – and give readers a concrete understanding – of what language is for humans, machines, and organisations alike.

For many readers, this will challenge familiar worldviews. The intersection of artificial intelligence and the human brain raises tricky questions about how we understand ourselves and the work we do. Therefore, the chapters are filled with specific examples and arranged in such a way as to rattle some habitual ideas about psychology. I have deliberately nudged some of the foundations of our thinking, because the rise of language models forces us to reconsider what we thought we knew about being human. This shift has triggered long and sometimes heated debates about intelligence, understanding, consciousness, and – perhaps most importantly – what we really “know” in psychological science. The questions raised by language models can’t be solved with more of the same research. We need new perspectives – ones that view humans and machines as part of a shared system.

Just as Alice1 was led down the rabbit hole into Wonderland–a strange and curious world–I have taken the liberty of creating a kind of rabbit hole in this book. Each turn down that hole offers the reader a fresh angle on familiar questions, drawn from both everyday psychology and formal scientific thinking.

New tools, apps, and language models are emerging faster than any book can keep up with. The use of language technology is exploding all around us. For that very reason, this book is not a quickstart guide to the latest trendy gadgets. If that is what you need, skip the book and go straight to the language bots themselves – each one is its own seductively simple and uptodate instruction manual of itself.

What I offer here is instead an invitation to expand our thinking beyond what language models themselves typically deliver. My somewhat uncomfortable, but wellintentioned advice is this: it may be worth your while to develop a deeper understanding. You need to do something with your own mind if you want to thrive alongside these technologies. That way, you will be harder to replace. If you let artificial intelligence explain how it works

without thinking about it for yourself, you have already allowed technology to replace part of your own soul.

The journey and the structure of the book start with a look at organisational psychology in practice: Why and how do managers and organisations try to predict and shape people’s behaviour? What actually happens when we recruit people, train them, and aim to boost their performance? Try to do it by pantomime alone, and you will see how human affairs depend on how we use language. What is language, really? Why can machines “speak”? Can they think? And how does automatic language technology affect organisations? The book aims to walk you through some of these fundamental explanations – starting with Information Theory. All representations in the brain are maps, which are codes, which can then be translated into machinereadable form. Following this chain of logic, eventually we will arrive at Reality – with a capital R – that quirky domain where even the smartest artificial intelligence begins to falter.

This book is grounded in research, teaching, and seminars I have had the privilege of conducting over several years. The way the topics are presented owes much to the questions and conversations I’ve had with engaged participants in those courses and lectures.

It is also the result of many engaged conversations with individuals who have been generous enough to inspire, engage with and correct my thinking. This Englishlanguage version of the book owes its existence to Jack F. Sharp, who has not only been in charge of the translation process, but has also been a continuous source of reflections, comments, illustrious ideas and warning words. I am much indebted to Jack for this cooperation. Moreover, the insights on which this book is built would not have come to me were it not for years of collaboration with Kai Rune Larsen, the unrelenting pioneer in the application of text algorithms on behavioural research. Although many of our coauthors might not agree with all ideas in this book, I am grateful for discussions over the years with Kim Nimon, Rajeev Sharma, Magno Queiroz, JeanCharles Pillet, Abe Handler, David Dobolyi. The views on psychology and its history stem from discussions with Geir and Jan Smedslund as well as Jana Uher and Auke Hunneman.

Ørjan Flygt Landfald and Elisabeth Holien have been essential for the practical experiments in classrooms.

Finally I want to thank Thalia Soline Arnulf for the art work, Gosia Adamczewska for being in charge of production and Sven Barlinn for editing it all.

Ås, 28.09.2025

Jan Ketil Arnulf

& Travel Guide

Human minds have always evolved through interaction with technology. Tools are extensions of our intentions “by other means”, and one such tool is what we now call “artificial intelligence”. To coevolve with our new talking tools, we must learn to understand both the tools and ourselves more clearly.

We use technology to shape the future in our image. In that regard, our concept of “intelligence” carries a strange builtin flaw: we tend to assume that the world is predictable and thus knowable. Undeniably, predictability benefits the hunter who wants an efficient weapon. Just as certainly, to be unpredictable is essential for the prey, as they must learn to stay hidden.

Organisations are advanced hunting tools. Operating them presents humans with three very different challenges: Problems, Secrets and Mysteries. Crucially, AI can only assist with two.

A map is a code for a message. The systematic study of codes, messages and media is called “Information Theory”. Essentially, the news is the same on both FM and DAB radio.

When a map becomes a mathematical code, you can therefore calculate new maps. That is how you get “language that speaks itself”.

guess the next word – they

We struggle more with language than we would like to admit. Your brain is packed with intentions of all kinds, at all levels. In short, you have agency. You are a selfdetermined agent.

Universities can now let a language model design their academic programmes. This poses the question – what do we really need from education?

Publishing the multiplication table adds little if people can already compute it. There is a lot we “know without knowing that we know”, much of which can be figured out if we just pause to think. Paradoxically, we often believe we need this knowledge, even if we do not. This is a hard blow to much research in organisational psychology.

Many scientific “constructs” have a tenuous relationship with reality yet remain useful. They are colloquially known as “social constructs”, and much of human behaviour depends on us taking them seriously, as there are scientific conventions for defining them. Language models can handle such “constructs” just fine, no matter how “madeup” they are.

To language models, all ideas appear equally “real”. They can’t tell a map from its terrain. This means that there is a real danger that they might eat the menu instead of the meal. In science, this is called a category error.

Fortunately, language is a flexible tool. We can create new linguistic tools and concepts to grasp new phenomena as they arise.

Psychology is especially vulnerable to our tendency to mistake the map for the territory. What do we really have inside our heads – and how does that affect our ability to predict human behaviour?

It’s time to

behind constructs, statistics, and philosophical mazes. What is the

involves many different codes, which are represented in many different ways in the brain. Here are some of them:

We do not need to understand every piece of technology in this world to use it. But users of a particular technology must understand it well enough for their own purposes. That raises the question: what should knowledge actually look like?

How much help are language models actually to organisational psychology? What is control, how does that relate to problems, secrets and mysteries, and how do we move from words to action?

to the Role of Text Robots in Organisational Psychology

and Technology as Organisational Innovation I: The Unpredictable

and Technology as Organisational Innovation II: The Predictable

Technology as Organisational Innovation III:

Most of real life happens outside the predictable rhythms of formulas and algorithms. We must understand the limits of prediction – and the value of inventing our own worlds. We do that by telling stories.

It was not such a big deal when we learned to read and write. Subsequently, it might not be such a big deal that machines now help us to read and write in a new way. What does matter is that we learn to use our extended cognitive abilities to figure out together what we are really looking at, once we have become used to the view.

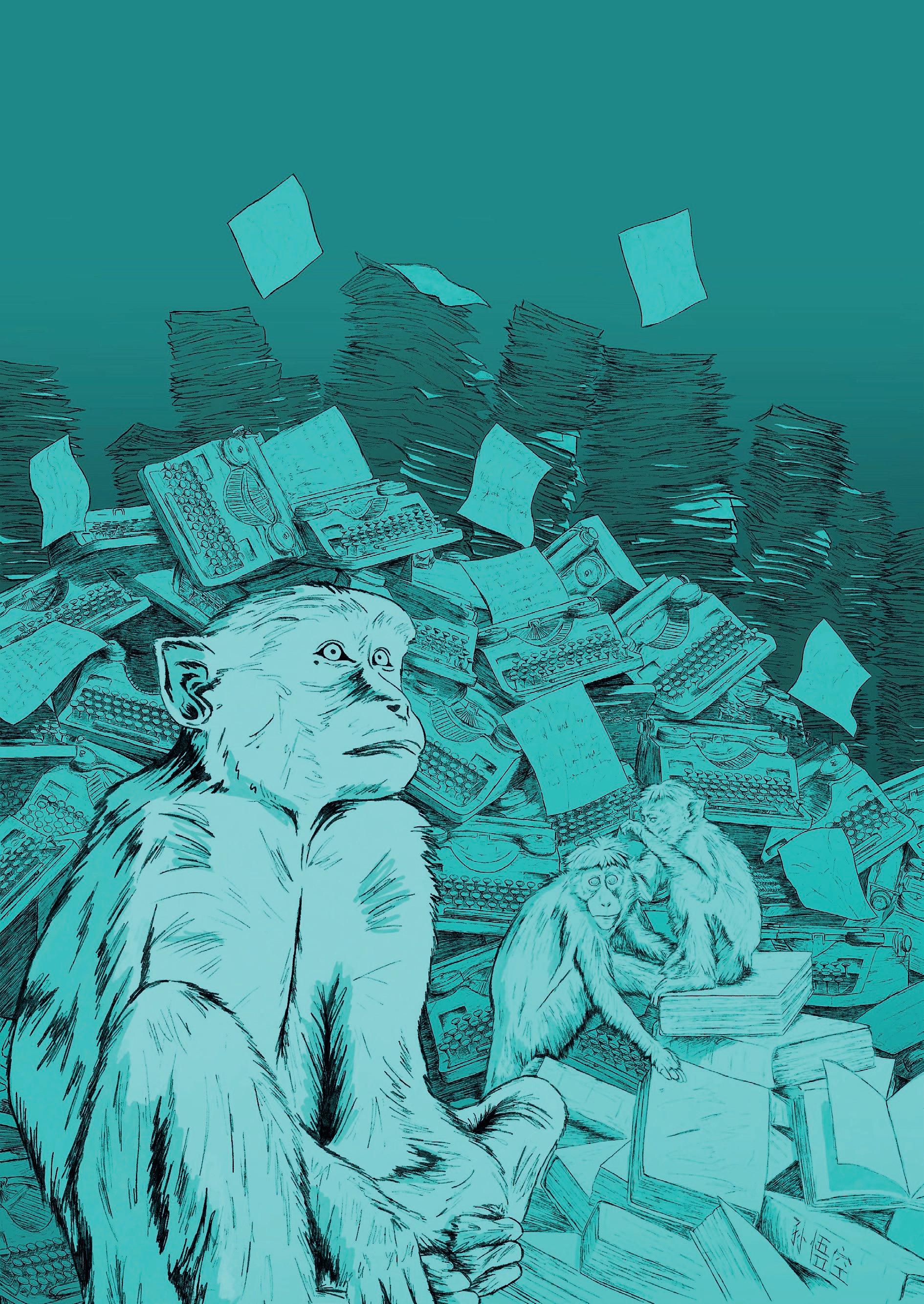

Language technologies and artificial intelligence are rapidly transforming the workplace. New services emerge almost every day, but what are the principles behind machines (and brains) that can talk? This book takes you behind the headlines and into the core of the technology. It explains how machines learn to speak, how this relates to language in humans, and what the implications are for organisations and management.

With humour and insight, the author opens the doors to a new frontier between humans and machines. You will gain an understanding of what happens in our minds, in the algorithms, and in organisations. The book provides you with a framework for understanding and navigating a reality where language has become digital – and where machines respond as extensions of your own mind.

Are you in control – or are you being controlled? What happens to leadership, trust and meaning in a world where technology both speaks and makes decisions? Could a language robot be your boss, your therapist – or even your romantic partner? With examples from neurobiology, leadership coaching, algorithms and even ticks, the book invites a thorough – and at times uncomfortable – reflection: How can machines contribute to your intelligence? Or will machines become smart at our expense because we stop asking questions?

This is a book for anyone who wants to understand more before technology starts to think for them.

Jan Ketil Arnulf is a professor of organisational psychology at BI Norwegian Business School and a part-time professor at the Norwegian Defence University College. He has researched, practised and suffered from the relationship between language, digitisation and leadership for several decades.

ISBN 978-82-450-6036-2