Other documents randomly have different content

The girl said, “They’re dancing over in the pavilion. Why can’t we go over there? It’s so poky sitting here. I want to have a dance. I know all the boys over there.”

“Do you mean to tell me you’d dance right after eating waffles?” the kid said. “Gee, that shows you don’t know what’s good for you. A scout isn’t supposed to hike right away after eating—gee whiz, you ask anybody.”

“I don’t want to ask anybody,” the girl said.

“Mr. Sorronto is selling things over at the pavilion and he won’t come back till the dancing is all over. He’s got a whole big pile of things on his tray. He won’t come back till the intermission. I’m just longingto have a dance,” she said. “I don’t see why you don’t come back later and tell Mr. Sorronto. He’ll be only too glad to give you back your twenty-five cents.”

“There might be a lot of reasons,” Pee-wee said. “Maybe the place might be closed when I come back. Now I see I had—maybe I didn’t have any right to do that. Do you mean to say I ought to sneak off?”

All the while the waiter kept his eye on them, and the girl was kind of sulky. She wasn’t mad, but just a little sulky. She wanted to go away, I could see that. She just pouted and said, “It’s poky sitting here after we’re all finished.”

Pee-wee said, “You’ll feel more like dancing if you have a good rest.”

“They’re playing a fox-trot,” the girl said.

“I know all about foxes,” Pee-wee said. “Do you want me to tell you about them?”

Oh, boy, I nearly died laughing. Brent had to put his hand over my mouth and Warde had to put his hand over Hervey’s mouth. There sat the kid with a terrible, heroic scowl on his face, and his feet kind of locked in the legs of the chair, and only nine cents in his pocket, and the girl looking at him and waiting, and the Italian keeping his eye on him, and the dancing going on over at the pavilion, and Mr. Sorronto lost in the shuffle. I don’t know where he was, he just forgot to come back, I guess. Poor kid, but just the same I couldn’t help laughing. It wouldn’t have bothered a sharpy

much. He’d have made her pay the quarter, heshould worry. I know sharpies, all right.

All of a sudden, Hervey Willetts broke loose. He went sailing into the room with that funny hop, skip and jump he has, and went winding in and out among the tables, and just as he was passing Pee-wee he grabbed him by the hand and began shaking it and saying, “H’lo, Scout Harris, I haven’t seen you in quite a while.” All the while he kept on going and went winding in and out among the tables and out through the door again. But I noticed Pee-wee had something in his hand under the table and I knew it was money.

“All right, if you don’t want to wait, I’ll pay him now,” Pee-wee said. “Gee whiz, it doesn’t make any difference to me.” Then I could see from the change he got that Hervey must have passed him a five dollar bill. That was the day he got his allowance from home; he got it every two weeks. I know he must have got it that very day or he wouldn’t have had it all still in his pocket. That was Hervey all over, reckless and careless.

Gee, I thought about that a lot later, especially after what happened pretty soon. Because while the four of us were standing outside laughing, he was the one to break loose and go to Pee-wee’s rescue. And he did it in a way so the girl would never know. I heard her say to Pee-wee, “That boy’s just a silly.”

But, jiminies, I can see him now the way he went in and out among those tables. He can’t do things like other people, he just can’t. Afterwards he told us that was called the Tangled Trail. Gee whiz, little we thought that pretty soon he’d be on a real tangled trail. Little we thought when we were all the time saying, “the plot grows thicker,” how pretty soon it would really grow thicker—for Hervey anyway....

CHAPTER XXVII

THE BLACK SHEEP

We all went over and watched the dancing a little while and then we started home. Pee-wee’s vamp (that’s what we called her) disappeared forever in the wild and woolly dancing pavilion. Pee-wee never saw her more—that’s what Brent said.

“I wonder how the sharpy happened to miss the carnival,” Warde said. “He’ll die of shock when he hears there was dancing there.”

“Come on,” Brent said, “we’ve got to hustle.”

“It’s early yet,” Hervey said.

“Yes, it’ll be early in the morning pretty soon,” Brent said.

Hervey just started singing:

“Early to bed and early to rise, And you’ll never meet any regular guys.”

He should worry.

We followed the Greenvale road to where Fox Trail branches out from it to the left. But anyway I guess the left-handed hike was off for that night. We dropped it, and if you pick it up you can have it— we don’t want it.

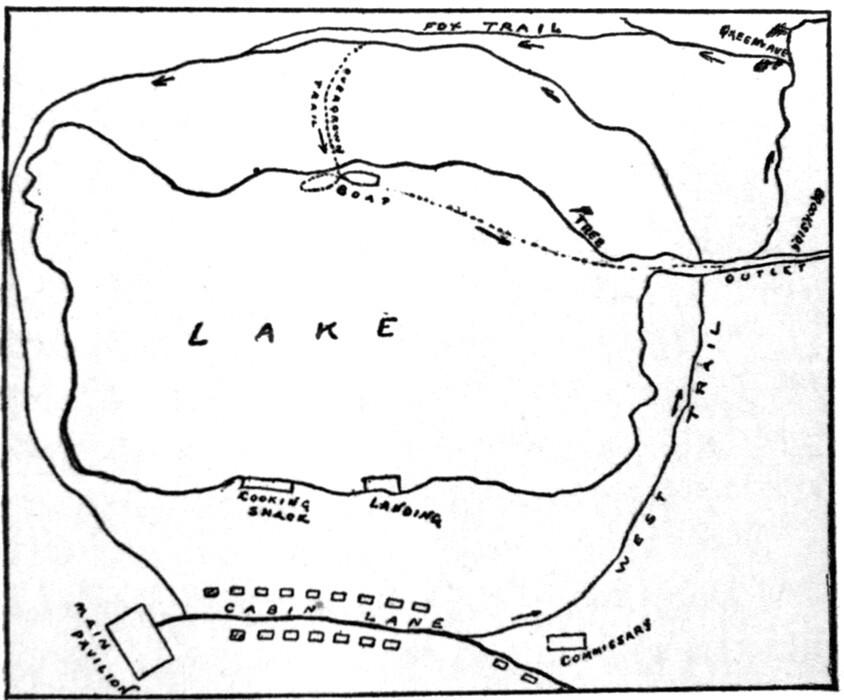

It was pretty dark and spooky along Fox Trail; it runs through the woods. It isn’t a regular road at all. That took us into the trail around the lake again; you’ll see where if you look at the map. And that trail took us into Cabin Lane right near the Main Pavilion. And there we were back at camp again. If it hadn’t been for Sandwich we might have been hiking around the lake yet and we might have starved just going round in a circle and that’s why I have so much respect for sandwiches, because they remind me of the little dog that saved our lives, especially tongue sandwiches.

There was only one light in camp and that was in Administration Shack. I thought it was funny because mostly there isn’t any light at all late at night. The lake looked awful black and the reflection of the light in Administration Shack showed away off on the water. It seemed like two lights. We went hiking up the porch of Administration Shack as bold as could be, with Hervey singing that crazy song:

“When you go on a hike just you mind what I say, The right way to go is the opposite way.

If you come to a cross-road don’t make a mistake, Choose a road, and the other’sthe one you should take.

Don’t bother with sign boards but follow this song, If you start on the right road you’re sure to go wrong.

You can go on your feet, you can go on a bike, But the right way is wrong when you start on a hike.”

Around he marched to the door singing a lot of other crazy stuff he knew that goes like this:

For up to twelve o’clock it’s late, Yes, up to twelve o’clock it’s late; It’s very late, It’s very late; Observed his father, surly.

So I’ll stay out till after one, Oh, I’ll stay out till after one, Replied his very wise young son; For after one it’s early.

In we went, pell-mell, and there was Mr. Arnoldson (he’s a resident trustee) sitting at the table reading a magazine. He just laid it down and looked at us and said very sober, “Well, what’s the big idea?”

I could see something was wrong; I knew he had been sitting up waiting for us.

“We’ve been to the carnival in Greenvale,” Brent said. “Some crazy day we’ve had.”

Mr. Arnoldson just said, “Hmph. Your idea, Willetts?”

“Why pick on me,” Hervey said.

“I guess we were all equally crazy,” Brent laughed.

Mr. Arnoldson said, “Well, I suppose you’re all equally reprehensible then. You scouts know the rules of this camp, don’t you? You know you’re supposed to be here at supper and afterward unless you have special permission to be away. Who gave you permission?”

Brent just said, kind of surprised, “Why, I thought it would be all right if we ’phoned. You said so yourself once.”

“You needn’t tell me what I said,” Mr. Arnoldson shot back at him. “Do you want me to understand that you ’phoned to camp?”

Brent was sort of a little mad. He said, “I don’t care what you understand, Mr. Arnoldson, and I think it’s all right to remind you that you said if scouts were going to stay out they must ’phone. We did ’phone. And we thought that would be all right.”

“At what time did you ’phone?” he asked us.

“At about half-past six,” Brent said.

“From where?”

“From the railroad station at Greenvale.”

That seemed to be a poser to him; he just drummed on the table and looked at all of us.

“Which one of you ’phoned?” he asked.

“Hervey ’phoned,” Brent said.

“Eh huh, I thought so,” Mr. Arnoldson said, with a kind of a funny smile. “Who did you talk to, Willetts?”

“A scout named Wilkins,” Hervey said.

“Ask him his name?”

“How do you suppose I found out?” Hervey said. “I didn’t want to ’phone, I’ll tell you that much. I didn’t care so much.”

“Don’t, Hervey,” Brent said in a low tone.

“I should bother,” Hervey said.

“Bother about whether you tell the truth or not? That what you mean?” Mr. Arnoldson asked him. Then he said, “Any of you fellows see him ’phone?”

“No, we waited outside,” Brent said.

“Ah, yes,” Mr. Arnoldson said with a kind of a smile. “Well now,” he said, and he clapped his hand down on the table, “there was no ’phone message received at this camp from any of you boys this evening.”

“You sure of that?” Brent asked.

“Absolutely,” Mr. Arnoldson said. “And there is no scout or anybody else at this camp by the name of Wilkins. I’m sorry for you four boys, Harris and Blakeley and Hollister and Gaylong, you were duped. It’s all right, go to bed and forget it. Willetts, you’re a liar and we don’t want any liars at this camp. You not only try to fool the management and disobey rules, but you fool your comrades. You thought we’d call you in if you ’phoned. And you knew these boys wouldn’t stay out without ’phoning. So you put one over on them; you lied to them. I was going to give you all a good calling down and then turn in because I’m sleepy. A good calling down wouldn’t have killed you.”

“Gee whiz, it wouldn’t kill me,” Pee-wee said.

“Now you four turn in and forget it,” Mr. Arnoldson said. “And you, Willetts, had better go up where your troop bunks, if you know where that is, and pack up your stuff and get out of here in the morning. And don’t ever show your face in Temple Camp again. Don’t talk back, and cut out the bravado; there’s the door, get out of my sight.”

Hervey just stood there gulping. I was glad he wasn’t able to speak because he would only have started swearing. He doesn’t care much what he says, sometimes. Anyway before he got a chance I kind of got hold of him and led him out through the door onto the porch. The others came out, too, but none of them spoke to him except Pee-wee. He said, “Good night, Hervey, and anyway I like

you.” Hervey didn’t say anything, didn’t even answer him. Brent and Warde started down Cabin Lane, but neither of them spoke to him. Brent made out not to see him at all.

Gee, I hated to leave him that way. I waited and said, “Hervey, don’t you care, maybe a camp like this isn’t the best place for you. I know most of the things you do you don’t stop to think. You wanted us to keep going and I’m not holding it against you. I know you’re reckless and you don’t think. Don’t you care because you’d never get along here anyway. I know the good side of you.”

“Do you think I’m a liar?” he asked me.

“No, I don’t,” I said. “Just that once——”

“Do you think I lied just that once?” he said. “Why should I lie? I’m not afraid of Arnoldson and that bunch. I’ve stayed away a dozen times, haven’t I? I never lied about it.”

I had to smile a little because it seemed as if he was even proud of it. I said, “No, I know you don’t care about the management. If you did—sort of fool Brent it was for our sakes—so we could keep on having fun.”

“Well, I either lied or I didn’t,” Hervey said.

“I know that,” I said, “but I’m thinking of a lot of things the others don’t think of——”

“SoamI,” said Hervey.

“Never you mind,” I said.

Just then the light inside went out and I started away, because I guess I didn’t want Mr. Arnoldson to come out and see me talking with Hervey. I’m ashamed to admit it, but that’s the way I felt.

As I walked along Cabin Lane to where our troops bunk I noticed that the reflection out on the water was still there even after the light in Administration Shack was out. But I was too sleepy and I was feeling too bad to think about that.

I made this map and it isn’t much good and it doesn’t show all the buildings and things at Temple Camp. But anyway it shows how Cabin Lane is and how West Trail turns out of it to the left and goes around the lake and comes into it again near Main Pavilion. So you can see how it is we kept going round and round the lake all the time till something happened. Follow the arrows if you don’t want to get anywhere. Only if you keep following them you’ll never get through the story.

Lucky for you Sandwich was with us, because if it wasn’t for him there wouldn’t be any story, so that shows how a mutt can be a good author.

ROY BLAKELEY

CHAPTER XXVIII

THROUGH THE MIST

In my patrol cabin all the fellows were asleep—they’re a sleepy bunch except when they’re awake. Even Warde seemed to be asleep, but that’s nothing because I’ve known scouts in my patrol to fall asleep on their way to our cabin and to undress in their sleep. They go to sleep beforehand so they won’t have to bother doing it when they get to bed. That way they save time. Pee-wee is a Raven, and so he didn’t sleep in our cabin.

I started getting ready to turn in, but I didn’t get very far. I don’t know, I felt sort of like you do just before exams in school. Kind of, I don’t know, shaky. Just because Hervey didn’t say anything to Mr. Arnoldson, that made me think that maybe he would do something crazy. If he had answered back more I guess I would have felt different.

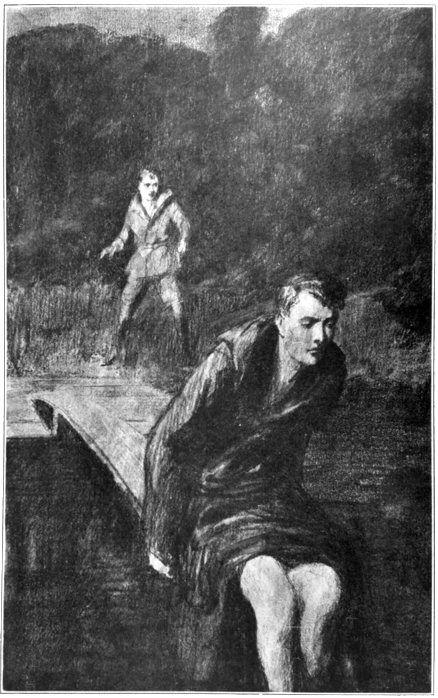

I SAW SOMEONE SITTING AT THE END OF THE SPRINGBOARD.

As long as I knew I couldn’t sleep I put my jacket on again because I hate to be lying down when I can’t sleep, just the same as I don’t like to be walking around when I’m sleepy. I was wondering what the scouts in my patrol had been thinking about Warde and

me. Because now that I knew no ’phone message had been received they must have thought it was funny for us to stay away. I’m patrol leader and I’m supposed to be a shining example. I guess I’m not so very shiny, but Warde is a good example; he’s a whole arithmetic.

So I put my jacket on again and went outside. It was pretty dark. Most always I’m dead to the world at that time of night, and it seemed spooky to be out when the whole camp was sleeping. Christopher, but it was still. There was a kind of a mist and it seemed to change everything; it got me all mixed up. I couldn’t tell where the shore of the lake was; it made the land and the lake sort of the same.

Until then I never knew that there were a lot of things in camp that make a noise, I mean the boats knocking against the landing and the weather-vane creaking, and things like that. Because you don’t hear them in the daytime, or any time when there are other sounds. But believe me, they gave me the creeps that night. Where I stood I could hardly see the cabins, the mist was getting so thick. I couldn’t see the tents at all. I just about knew where the lake began.

All of a sudden I saw something terrible. I saw a thing walking. It was the same color as the mist, I could only just see it. I couldn’t see that it had any legs, it just kind of moved, it was the same all the way down to the ground. I couldn’t stir I was so frightened.

I just stood where I was and, gee, I admit that my heart was thumping. I heard the chains on the boats clanking and that made me shiver. Lots of times I’d heard them before, but they sounded spooky that night.

The thing kept going and got to the lake and kept right on walking over the lake—walked right out over the lake. A little way out it kind of faded away in the mist. Then I didn’t see it any more. I just stood there, I couldn’t move....

CHAPTER XXIX

EYES TO SEE AND EARS TO HEAR

Then all of a sudden I made up my mind I wouldn’t be scared. I walked right toward where I had seen the thing, because I wanted to prove to myself that I hadn’t seen anything at all.

Then, in a minute, I had to laugh to myself. I came to the end of the narrow board-walk that is built out to deep water where the diving board is. Out at the end of the springboard I could hear a voice, very low. I walked right out along the boards, making a lot of noise so as to prove that there wasn’t anything spooky at all.

Away out at the end of the springboard I saw some one sitting with his feet dangling over. When I got away out to the end I saw it was Hervey. Sitting right close beside him was Sandwich. Hervey had his bathrobe on but it was thrown off from his shoulders and I could see he only had his trousers on. He was kind of shivering.

I said, “You gave me a good scare, Herve. I saw you come out here, but I couldn’t see the platform under you, the mist is so thick. I thought you were a ghost or something. What are you doing out here anyway?”

“Oh, just sitting here,” he said. “You’d better go to bed; you know the rule.”

I said, “How about you?”

“I’m not a part of this outfit any more,” he said. “I’m through— almost through.”

I said, “You’re just as much of a scout as I am to-night. It’s a wonder you couldn’t keep one rule before you go away. What are you going to do? Go in swimming? And besides when you tell me I’d better go to bed that’s as much as saying I’m not as good as a dog. Do you say that—that I’m not as good as a dog?”

“Sandwich didn’t call me a liar,” he said.

“Did I call you a liar?” I shot back at him.

“You’re a scout,” he said, “and they’re all the same. They’re as much the same as a lot of clothes-pins.”

I said, “I know you’re different, Hervey. But I didn’t call you a liar and none of us fellows did. I admit they think you lied and——”

“You think so too, don’t you?” he said.

“I don’t know what I think,” I said. “But I know I like you, and I’m going to stay right here as long as you do. A scout has to—no matter what, a scout has to——”

He just laughed kind of sneering like. He said, “You call yourself a scout. G-o-o-d night! You’re a peachy bunch, you fellows. You ought to all be slapped on the wrists—Arnoldson and the whole crowd.”

I said, “Yes, and how aren’t we scouts?”

“You’re all the time shouting about deduction, and observation and all that bunk,” he said. “I don’t claimto be a scout. But if I did I wouldn’t wear a pair of blinders. I wouldn’t hear a friend called a liar, I wouldn’t. Hey, Sandwich?”

“What did we do?” I asked him.

“Well, one thing,” he said, “did you notice the ’phone in Administration Shack to-night? Did you notice the receiver was hung upside down? Did you notice how somebody must have been rattled and hung it up in a hurry? Did you notice the map portfolio lying open? Did you stop to think that it was while everybody was at supper that I ’phoned? And one thing more I’ll tell you too; the voice that answered me lisped. Now you better run to bed. Hey, Sandwich?”

“What do you mean—lisped?” I asked him. “What of it?”

“Don’t make me laugh,” he said. “You don’t even remember that the sharpy we met on the other side of the lake to-day, lisped. You don’t remember how he was asking about the trail here? He was the fellow that gave me the name of Wilkins, because he was all rattled when the ’phone rang. Stick around a little if you’d like to see him dance. He’s going to do a dance to-night that he never did before. And it isn’t going to cost him a cent. Is it Sandwich?”

CHAPTER XXX

THE THREE OF US

I said, “I don’t understand. What do you mean? What are you going to do? I didn’t call you a liar, Herve. You admit I didn’t, and I’m blamed glad I didn’t. You did ’phone then—did you? Just say you did—just say it so I can say I believe you. Tell me more—I I believe every blamed word that you say. I admit I’m a punk scout—now are you satisfied?”

He said, sort of more pleasant, “You’re not so bad, it’s Arnoldson and that crowd—the keepers.”

I said, “Go on and tell me.”

“Didn’t you notice a light away across the lake when you came out of Administration Shack?” he asked me.

I said, “I thought it was the reflection of the light.”

“Somebody is out there,” he said. “You can’t see the light now on account of the mist. But somebody is out there. I can see a little glimmer now and then.”

“I can’t see anything now,” I said.

“That’s because nobody called you a liar,” he told me. “It means more to me than it does to you.”

I just gulped, I could hardly speak. I put my hand on his bare arm, it was all tattooed by some old sailor that he met once, and I said, “You’re—you’re not going to get away with that, Hervey—not with me. It means just as much to me—it does—as—as it does to you. It’s just like as if he called me a liar. That’s the way I feel now. I can’t see any light out there, but whatever you’re going to do I’m with you. If that crazy fool came to camp and sneaked into Administration Shack hunting for the chart he had heard about, he’s a bigger fool than I thought he was. Do you suppose his name is Wilkins?” I asked Hervey.

“No, he just gave that name,” Hervey said. “If he’d had any sense he’d have stood the receiver off when the ’phone rang. I suppose he got rattled. It’s just a crazy fool enterprise all through. He’s out there now, fishing around, I suppose.”

“I’m glad you admit it’s a fool enterprise,” I said. “Brent was afraid you’d want to go fishing for it yourself.”

“All I’m interested in is fixing Arnoldson,” Hervey said. “I’ll make him look like two cents before I go. Come on, Sandwich, if you’re going.”

I said, “What are you going to do, Herve?”

“I’m going to swim over there,” he said. “If it’s that dancing monkey out there, he’s coming back here to admit he answered the ’phone. I don’t care anything about his sneaking into Administration Shack or anything else, that’s his business. But he’s coming back here to say he answered that ’phone call. Or else he’s going to the bottom of the lake. That’s me.”

He started sliding off the board, but I held him back. I said, “Hervey, you’re crazy, you’re not going to swim over there.”

“The boats are locked,” he said.

“Well,” I said, “I’ve got the key for them.” Gee, I never felt more sorry for Hervey than I did then. Because all the scouts at camp had keys for the boats. They were only kept locked at night on account of strange fellows coming there and using them for eel bobbing. It seemed that Hervey was the only fellow that didn’t have a key.

I said, “Hervey, I can’t swim that far, even if you and Sandwich can. But I’m going with you, so you’ll have to use a boat; remember you’ve got a punk scout with you, Herve. You have to make allowance for me. Will you wait just a minute?”

I groped my way back to my patrol cabin and got a padlock key out of my duffel bag. Hervey was still waiting, swinging his legs from the board. Sandwich was right close beside him.

“Come on,” I said, “we’ll row over. If he’s there we’ll find him and if he’s the one why then he’ll sit out the next dance and have a free ride back to camp; that ought to appeal to him.”

“You’re breaking the rule to use a boat after nine o’clock,” Hervey said.

“You’re doing well,” I laughed. “Where did youever learn the rule? I always thought that you wouldn’t even know a foot rule unless you were introduced to it.”

“I don’t want to get you in Dutch,” he said.

I said, “I’m not thinking about rules at all. I’m thinking about you. Come ahead.”

CHAPTER XXXI

THE VOICE IN THE NIGHT

Maybe I wouldn’t have thought the same as Hervey did about it, only for his telling me that the person who answered the ’phone lisped. I hadn’t noticed anything in Administration Shack at all, I have to admit that. But if some one answered the ’phone some one must have been there. And if there were signs that some one had been there, we ought to have noticed them.

When I thought about it as we rowed out on the lake, gee whiz, I could see plain enough that that young freak we had met would be just likely to hike around to camp and walk into Administration Shack if no one was there. Anyway all the camp was at supper when we were waiting for Hervey to ’phone, I knew that much.

Probably he didn’t find anything in the map-case to help him, but that wouldn’t stop him from grappling around in the lake late at night. Mr. Ellsworth says that people who hunt for treasure are always fools. A lot of fools had hunted for that tin box before the sharpy, I know that. And a lot of fellows had talked about it all around the neighborhood. Look at Harry Donnelle; he was starting to hunt for it.

Anyway, one thing, I knew that the only way Hervey could square himself was for him to get hold of the fellow who answered his call. You needn’t think I was going out on a treasure hunt, because I wasn’t. But Hervey only had that one chance, and I was going to help him.

We rowed around the edge of the lake close enough in so that we could make out the shore, because that night we couldn’t have seen where we were going if we hadn’t. Sandwich sat on the little threecornered seat in the bow; he looked funny sitting there. The mist

was so thick the handles of the oars were wet and it was all beady with little bits of drops of water all over inside the boat.

I said, “What are you going to do, Herve? Suppose it’s him, what are you going to do?”

“I’m going to make him admit what he did, I’m going to make him admit it to Arnoldson,” Hervey said. “That’s all I care about.”

“And then you’ll stay at camp?”

“What?Me?” he said. “Not so you’d notice it. I’m through with this crowd—a lot of medal chasers.”

I was rowing and he was sitting sideways up on the stern seat with his knees drawn up and his hands clasped around them. The little hat without any brim that he always wore looked funny. It always looked funny but, I don’t know, that night it looked especially funny. It was all cut full of holes. Somehow it kind of seemed to me that nobody understood him. Maybe Sandwich did. Anyway I hoped that things would work out like he thought they would.

I said, “Herve, if the fellow that answered you lisped, why didn’t you say so right then? Didn’t it make you suspicious?”

He said, “I never thought about it till we got back, and I saw how things looked in the office—and Arnoldson called me a liar. Then I remembered. I remembered that the fellow we met lisped and that the voice over the ’phone lisped. I’ll nail him all right,” he said. “You leave it to me. He’s got more resourcefulness, or whatever you call it, than most of you chaps have, I’ll say that much for him.”

“Thanks for the compliment,” I said. It seemed funny to me that he wasn’t mad at the fellow for what he did, only at Mr. Arnoldson. He seemed to think the fellow had done a pretty good stunt. If anybody can understand Hervey—g-o-o-dnight!

He just sat there, perched up on the stern seat, very calm and quiet. I couldn’t make out if he really wanted to square himself or just have an adventure. I rowed around past the outlet and then he beckoned for me to stop. I rested on my oars, and we both listened. It was very still. Once a fish jumped, and that startled me. I could hear an owl way far off.

We drifted out from shore a little till we couldn’t see the shore at all. It seemed as if we were in the middle of the ocean; we couldn’t see anything only just a little water around us. It was so strange it had me nervous. There wasn’t any light anywhere that we could see.

“Listen,” Hervey whispered.

“I don’t hear anything,” I said under my breath.

“Shh,” he said.

“Do you mean that little clanking sound?” I asked him.

For just a minute or so he looked down into the water. I couldn’t see anything there except that the water was rippling a little. I didn’t think that was anything worth noticing.

“What’s the matter?” I whispered.

He didn’t say anything, just reached and took one of the oars from me.

“What’s the matter?” I whispered.

Still he didn’t say anything but felt around a little in the water with the oar.

I whispered, “I don’t think it’s worth while fooling around after the money if that’s what you’re after. That’s not going to square you at camp.”

“Got a fish-line?” he whispered.

I just couldn’t help saying, “Yes, I have; scouts carry fish-lines, that’s one good thing about them.”

There was a hook on my line. He tied an oarlock to the cord for a sinker and let it down into the water. Pretty soon he began pulling it up again and all of a sudden, there right outside the boat was a long, thick, gray thing. Right away I saw it was a fishing seine that he had lifted up. He reached over and grabbed it and then, somewhere near us I heard a terrible scream, and then a splash. I couldn’t see anything, only the thick mist all around....

CHAPTER XXXII

HERVEY ALL OVER

I was so excited that I let one of the oars go sliding into the water.

“Where are you?” Hervey called. “Can’t you hang onto the boat?”

“It’s sinking,” a voice called.

“It won’t sink,” Hervey shouted. “It’ll swamp. Hang onto the stern of it. Where are you anyway?”

While he was calling he was feeling for the oars and I had to tell him that one slid into the water. I wouldn’t tell you what he said, but anyway he was excited. We could hear screaming and splashing and cries of “Help,help!”

“Hang onto the boat,” Hervey cried. Then he said to me, “Keep calling so I’ll know where you are. Don’t try to move, you don’t know which way you’re going. Just let her stand as long as we can’t row. She won’t go far, only keep calling. All right, I’m with you,” he shouted. Then, before I could say anything he had jumped into the water and was swimming off. The mist just swallowed him up and in a few seconds I couldn’t see him at all, only hear the sound as he swam and that voice somewhere.

“Here I am,” I kept calling. And sometimes I gave the Silver Fox call (that’s the call of my patrol) so he would know where I was. But somewhere another voice kept giving the same calls and I knew it was an echo and maybe he wouldn’t know what way to go when he started back. Every time I called the echo called too, from somewhere far off.

Pretty soon I could hear voices and I heard Hervey say, “Let go your arm, leave it to me.”

“I’m here,” I called. “Here—here—here—here I am. That other voice is an echo—here I am—right here—right here——”

Pretty soon I could see him coming out of the mist. It seemed just as if it broke open to let him through. He was holding some one up and I could see a head sort of hanging back and looking up at the sky.

“All right?” I asked.

“Sure thing,” Hervey said. “Get hold of him, will you?”

“At the stern,” I said. I was glad to show him I knew that much anyway, never to lift a person over the side of a small boat.

It was some job getting the rescued fellow aboard, and then I saw it was our friend, the sharpy. His coat with the slanting pockets looked awful funny all wet and clinging to him. He was all right, that was one good thing, but his sharpy suit—goodnight! The worst that had happened to him was a good scare.

“He was doing a new dance when I grabbed him,” Hervey said.

The fellow just lay in the bottom of the boat breathing hard, but I could see he was all right. He reached up with his left hand and fixed his funny little necktie, and then I knew he was all right. I guess he would do that in his sleep.

“He’s going to sit out the next dance,” Hervey said.

“What happened?” I asked him.

Then he told me just how it was. The fellow was dragging the lake with a seine. He had fastened one end of it on shore and was rowing with the other end. When Hervey lifted the seine and grabbed it the fellow happened to be standing in his boat and it pulled him over into the water. He grabbed the boat along the side and, of course, that swamped it.

I’ll say one thing, if the old tin box is ever found that will be the way to find it—dragging with a seine. And that cake-eater would have stood a pretty good chance of finding it too if he had been free to work in the daytime. But he was trying to do it all alone in the night, that was the trouble. Anyway it gave him a good scare and took all the nerve out of him.

Hervey said to him, “Well, you had a wild night. If you had only told me what you were going to do when we were talking over the ’phone I’d have joined in with you. And we’d have found it. It serves

you right for staying away from dances. You have to come back with us to tell one of the keepers that I’m not a liar and then I’ll hike as far as Catskill with you if you’re going that way.”

“I’m staying at Brookside,” the sharpy said.

“Well, come over to Temple Camp anyway and see the fun,” Hervey said. “It’ll do you good.”

I saw that Hervey was just in one of those happy-go-lucky, reckless moods, and that now after all he didn’t care so much about anything—unless there was an adventure in it.

So I said, “Mr. Wilkins, or whatever your name is, only I guess that isn’t your name, when you had your first scare to-night, that was when you heard the ’phone ring over at camp, you got this fellow in Dutch. You got him called a liar because he said he ’phoned to camp and they never heard of any message. We know all about what you did to-night and nobody’s going to make any trouble for you, because anyway, one thing, you’ve had trouble enough. There’s a man, he’s trustee——”

“All you have to do is tell him he’s a liar,” Hervey said. “Then I’ll hike as far as Brookside with you.”

“You don’t have to tell him any such thing,” I said “You stick to me and you’ll be O. K.,” Hervey told him. “Didn’t I just save your life?”

The poor sharpy didn’t know what to make of it all. He was grateful to Hervey, that’s sure. I guess he saw it wasn’t any use denying anything. I guess he wasn’t scared any more, because Hervey seemed to be making friends with him, sort of. I had to laugh because after all Hervey’s fine plan to bring this fellow back like a prisoner, there he was sort of pals with him. Christopher, but he’s a sketch.

The fellow said, “They’ll make a lot of trouble for me over there.”

“They make it for me too,” Hervey said; “don’t you care.”

“The place was open; I just walked in,” the sharpy said. “There was a sign that said Visitors Welcome. You fellows invited me to drop over.”

“You sure dropped over,” I began laughing. “The water is unusually wet to-night. You didn’t take anything over there. They’ll give you a good calling down, that’s all.”

“I get one of those every day,” Hervey said.

“You mean every minute,” I told him.

Then I said, “All you have to do is come over with us, and anyway you can’t help it, because I’m sculling the boat around now, and then all you have to do is admit just what you did so as to prove this friend of mine didn’t lie. You can do that much, can’t you? He saved your life. You can put him right with the crowd over there, can’t you? That’s all you have to do. It’s just a question of whether you’ve got a yellow streak or not.”

“And we’ll have a lot of fun doing it too,” said Hervey.

CHAPTER XXXIII

HERVEY’S SERENADE

Honest, I’d rather run the whole Silver Fox Patrol than try to run Hervey Willetts. But as we sculled around I could see that even that other fellow was kind of getting to like him.

Hervey sat perched up on the little three-cornered seat in the bow with his legs dangling out into the water on either side and Sandwich lying on the bottom near him. He looked, I don’t know,—I just had to laugh when I looked at him.

I said, “Herve, after all this you’re not going to spoil everything, are you? We had a good time to-day and we’re going to have a whole lot more. You’ve got a medal coming to you for what you did to-night. You were called a liar and now a couple of hours after that you can have the whole camp eating out of your hand, Mr. Arnoldson and all. This fellow, you’ve captured him too, and he’ll go the limit to help you. Won’t you?” I said.

“Nobody can say I have a streak of yellow and get away with it,” the fellow said.

“For goodness’ sake don’t mix things up now when everything’s coming your way,” I said to Hervey. “They’ll wrap Temple Camp up for you and send it home prepaid. Will you let me see Mr. Arnoldson and tell him?”

He said, “Blakeley, I’m through with this outfit for good. I beat it to-night.”

“While everybody’s shouting for you?” I asked him.

“Precisely, exactly,” he said. “I might have joined a circus this summer——”

“Goodnight!” I laughed.

“Instead of hanging around here and being insulted,” he said.

“You should worry about being insulted,” I told him. “If you care as little about being insulted as you care about most things, especially risking your life, it won’t take you long to forget it. Besides when you threw an old tomato at the bulletin board so you wouldn’t be able to read one of the rules on it, wasn’t that insulting the camp? If you’d only forget insults as easy as you forget rules, gee, I’d be satisfied,” I told him.

He just said, “Insults I can never forget, Blakeley.” All the while he was trying to balance the boat hook on his nose.

“You make me tired,” I told him.

When we got to the landing he said, “Come on if you want to see the grand finale; come on, Wilkins.”

The sharpy kind of hung back. He said, “My name is Tripler.”

“I knew it would be something about tripping,” Hervey said. “Believe me, you’re the one that’s going to trip,” I told him.

He just said, “Come on, finalehopper, if you want to see the grand finale. Absolutely nothing can happen to you. Come ahead, Blakeley, if you want to see me wind up in a blaze of glory.”

I knew he was going to do some crazy fool thing, how could I stop him? I could see that Tripler, or whatever his name was, was kind of nervous, but Hervey had him following like a little dog. That’s Hervey. He went sauntering up through Cabin Lane, swinging his stick and shouting:

“Early to bed and early to rise, And you’ll never meet any regular guys.”

I could hear sounds of scouts moving in the cabins, but a lot he cared. By the time he got to Official Bungalow there were about a dozen sleepy looking scouts with us, with their clothes all endways and their hair all rumpled—they were a wide-awake looking lot, I think not.

“What’s he up to now?” one of them gaped.

Geewilliger, Hervey looked like a what-do-you-call-it, one of those knights of old standing in front of a castle.

“Search me,” I said to one of the fellows. “He reminds me of Sir Building Lot, or whatever they call him, in the tales of King Arthur.”

“Mr . Arnoldson!” Hervey shouted. “Oh, you Mr. Arnoldson, come out here and apologize to me before I start home! Wake up, you old boob!”

“Cut it out,” I said to Hervey; “you mind what I tell you now.”

He just kept shouting, “Come on out if you’re not ashamed to face me! Come on out till I put it all over you! Oh, you Arnoldson; come on out and take back what you called me! Come on out if you want me to accept your apology! Come on out if you want me to apologize your acceptance! Don’t be afraid of the dark! Come ahead out! Oh, you-u-u-u, Mr. Arnoldson, come on out; it’s nice and foggy!”

I said, “Will you keep still, Hervey.”

All of a sudden somebody wearing a bath robe came out on the porch. Then a couple of heads appeared at windows.

“All the fish in Official Bungalow wake up,” Hervey shouted. “Is that you, Mr. Arnoldson?”

“Careful what you say now,” I whispered to Hervey.