IN-DEPTH BRIEFING AUGUST 25

AUTHOR Philip Reid Visiting Fellow, CHACR

The Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research is the British Army’s think tank and tasked with enhancing the conceptual component of its fighting power. The views expressed in this In Depth Briefing are those of the author, and not of the CHACR, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, Ministry of Defence or British Army. The aim of the briefing is to provide a neutral platform for external researchers and experts to offer their views on critical issues. This document cannot be reproduced or used in part or whole without the permission of the CHACR. www.chacr.org.uk

PART 1

A MARCH WEST: THE WESTERN THEATRE COMMAND AND CHINA’S POWER PROJECTION

OF the five regional theatre commands established under Xi Jinping’s sweeping reforms of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the Western Theatre Command (WTC) is the least known to defence writers. Aloof from the partially-globalised world of the Chinese seaboard, it typically draws international attention only during confrontations along the Line of Actual Control between China and India. The theatre, however, also has a near-4,000 kilometre border with Pakistan, Afghanistan, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, as well as a 50-kilometre salient to the Russian Federation across the Altai mountains. The WTC abuts the Collective Security Treaty Organization – including Russian forces stationed in Central Asia, the

Commonwealth of Independent States Joint Air Defence System, and the US Central Command. Once the locus of nuclear brinkmanship, China’s formerfrontier with the Soviet Union has been demilitarised since a 1997 quinquepartite agreement. This depth has been the bedrock of all Chinese military strategy in the 21st Century, which is now focused on a ‘local war’ inside the First Island Chain.

Three observable trends suggest that the status quo cannot be assumed in future decades. The first is a putative ‘pivot to Russia’ – alleged to be taking place under the second Trump administration and inspiring analogies with the 1972 Nixon-Kissinger mission that brought China de facto into the American system of Soviet containment. The economic and political strain on the Russian state is also inviting comparisons

with the two fateful episodes of imperial disintegration in 1919 and 1989. The ‘Monograd’ rustbelt straddling the Trans-Siberian Railroad along China’s northern periphery has seen episodes of instability during the present conflict, these include protests against unemployment and conscription, as well as sabotage of the railroad.

A third narrative centres on the assumption that China’s recent economic ascendancy in Central Asia will bring greater coercive pressure from Beijing. Popular ‘Sinophobia’ in the five republics has often been dismissed as a legacy of Soviet propaganda but, nevertheless, still resonated in the 2010s, with a new generation protesting the Chinese acquisition of land, resources and ecological abuse. China has traditionally framed its defence diplomacy in post-Soviet

Central Asia in the context of Uighur separatism, but advances in PLA ballistics and aviation, and the development of Xinjiang’s transport infrastructure, mean that for the first time since the Mongol period, China’s Far West may be conceived of as a platform for meaningful power projection. Central Asia is no longer a quiet frontier populated by nomadic tribes and oasis towns, and the region’s rapidly growing population is four times that of Xinjiang. Any loss of Russian control over its Central Military District would likely impact regime stability in Central Asia and it is the WTC that would be charged with intervention.

This three-part In-Depth Briefing will examine the force posture and power projection capabilities of the WTC through the lens of long-range strike, cross-border air assault and ground intervention. The baseline scenario is not a peer conflict with the Russian Federation but the collapse of a Central Asian government or an attempted defection or secession in the Russian Central Military District. Focus is also given to WTC’s northern and western borders

The five theatre commands of the People’s Liberation Army. Graphic:

Joowwww/Li Chao/Bxxiaolin/Public Domain

rather than its Himalayan frontier, which has been written about extensively, or Mongolia, whose demography, economy, transport infrastructure and defence posture is skewed towards the Northern Theatre Command.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION

The PLA’s Western Theatre is vast, twice the size of India and comprises roughly 40 per

cent of China’s total territory. It encompasses Gansu and Qinghai Provinces, Tibet, the Xinjiang and Ningxia autonomous regions, as well as the Chongqing Municipality. While its reflagging represented the union of the former-Chengdu and Lanzhou Military Regions, the WTC remains bifurcated in terms of indigenous culture, lines of communication and force structure. The southern half of the WTC is dominated by the Tibetan Plateau, the northern by the westwards extension of the Gobi Desert. A single Group Army is deployed westwards along each axis from Chengdu and Xining, West of Lanzhou –both headquarters situated on the edge of the Central Chinese plain, several thousand feet lower in altitude than their brigade-level sub-commands. While the road and rail infrastructure connecting Chengdu to what was once an isolated and independent Tibetan kingdom is relatively new, the main thoroughfare between Lanzhou and Urumqi contours what has been colloquialised since the 1950s as the ancient ‘Silk Road’ and is a constituent economic corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Silk Road revivalism has played an important role in contemporary Chinese foreign

policy but Xinjiang and Tibet can claim little cultural relevance for Han civilisation or party folklore. Xinjiang was only a genuine imperial concern during the Tang and Qing dynastic periods, but remained ‘semi-barbarian’ – only fully incorporated into the Qing in 1884. Under communist rule, the sparsely-populated West has continued to be administered on a colonial basis with resource extraction and border integrity buttressed by state-sponsored Han immigration from China’s demographic core. During the Chinese Civil War, the Soviet state police were invited to invade and pacify Xinjiang, and the doubling of Soviet forces along the border after 1966 drew no commensurate response from Mao. The PLA’s 1980 strategic guideline continued to advocate that ‘untenable’ Xinjiang would be abandoned in the event of invasion.1

It is difficult to argue, therefore, that the WTC has a cohesive ‘strategic direction’ – a PLA doctrinal term traditionally used to focus the dominant threat picture but understood, postreforms, to imply the general orientation of each theatre command. Total force strength is estimated to be a quarter of a million, roughly half of what it was in the 1960s and the WTC’s 76th and 77th Group Armies command a total of 12 combined arms brigades – now

the PLA’s primary manoeuvre unit.2 This is slightly less than the Northern, Eastern and Central Theatre Commands, but like the Southern, the West has additional infantry brigades. The Southern also has only two Group Armies but has two naval bases and fields more fighter and close air support brigades. The WTC hosts three corps-deputy-grade -PLA Air Force (PLAAF) ‘bases’, more than the two stationed in other theatres, as well as an air transport division.3 Due to the fluid situation along the Line of Actual Control and the region’s role as a ‘testing ground’, the WTC does receive a greater share of advanced military hardware than all other theatres bar the Eastern but, fielding the greatest number of heavy-armoured brigades, the Northern is the only theatre command configured for a hypothetical ground war with the Russian Federation.4

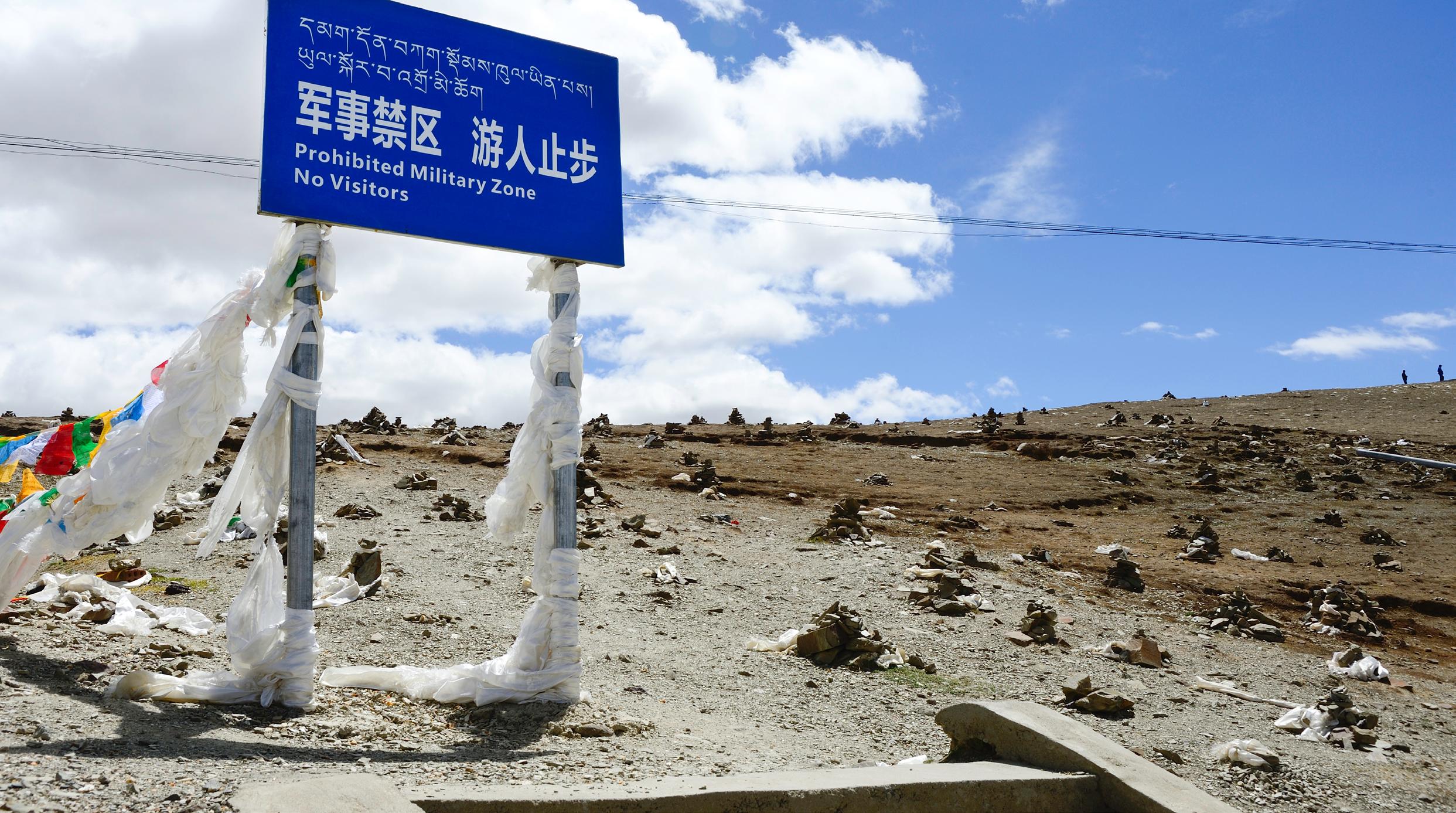

The role of the WTC in the People’s Republic of China’s integrated air defence system will not be examined here in detail. There are, however, dozens of sites across the theatre operated by the radar and ground air defence branches of the PLAAF and some level of digital integration with Group Army surface-to-air missile battalions is also assumed by analysts.5 The PLAAF has been replacing its

road-mobile variants: the HQ-9 (pictured below), China’s S-300 derivative, which is now the backbone of the force. Most of the WTC’s 20 or so HQ-9 batteries are deployed in depth from the Line of Actual Control.6 S-400s purchased in limited numbers from Russia in the 2010s have also been sighted at Hotan and Nyingchi.7 Satellite imagery showed that the WTC received a relatively large proportion of the HQ-22 batteries rolled out nationally since 2019, however, force concentrations in Urumqi and Chengdu are still defended by older point-defence systems such as the HQ-16 and HQ-6.8

TRAINING AND SPECIALIST FACILITIES

The contiguous tract of sparsely inhabited desert and highland between Lanzhou and the Tarim Basin is an aeronautical and ballistics hub that contains some of the PLA’s most sensitive sites. Located outside Yinchuan, the capital of Ningxia Province, is a PLA Rocket Force test and training district, established under the 69th Base in 2017 and closely associated with an adjacent training area at the Jilantai Salt Lake in Inner Mongolia. A variety of impact sites are utilised across Xinjiang and Gansu, with targetry ranging from simulated fuel depots and electrical substations to

mock-up aircraft carriers and runways.9 Yinchuan is also home to the Qingtongixa Combined Arms Tactical Training Base, a sophisticated facility equipped for urban warfare and joint training with the PLAAF, which contains a 900 by 700-metre model of the contested Aksai Chin region in the Line of Actual Control’s Western Sector.

Two hundred kilometres to the west, the PLAAF operates a chain of surface-to-air and air-superiority training bases extending north and eastwards from Jiuquan around the perimeter of the Badain Jaran Desert. The PLAAF ‘Test Flight and Tactics Base’ at DingxinHedongli is used for live fire and complex electromagnetic environment training.10 North of Dingxin lies the Dongfeng Aerospace City encompassing the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre – a corps grade subordinate of the PLA Aerospace Force. The

1M. Taylor Fravel, Active Defence: China’s Military Strategy Since 1949, Princeton University Press (2019), 143, 173.

2Thomas W. Robinson, The Sino-Soviet Dispute: Background, Development and the March 1969 Clashes, RAND Corporation (1970), 24.

3United States Department of Defence, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, Office of the Secretary of Defence Annual Report to Congress (2024).

4Benjamin Lai, The Dragon’s Teeth, Philadelphia and Oxford (2016), 108.

5Eric Hundman, China’s Air Defence Radar Industrial Base, China Aerospace Studies Institute (2025).

6“China: Military”, Janes (2025).

7Shishir Gupta, “Chinese S-400 systems across LAC, forces India to rethink air defence”, Hindustan Times, June 23 2021.

8“Chinese HQ-22 deployment”, Activity Analysis, Janes (2018).

9Peter Wodd and Alex Stone, China’s Ballistic Missile Industry, China Aerospace Studies Institute, May 2021.

10Derek Solen, Modernization of Fighter Pilot Training in the PLA Air Force Proceeds Apace, China Aerospace Studies Institute, November 2024.

Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre (pictured) features the most extensive infrastructure of the PRC’s four launch sites and has played a formative role in China’s Long March programme, its Shenzhou-manned and spaceplane missions, as well as the development of the Dongfeng ballistic missile series. The WTC hosts three ground stations subordinated to the Xi’an Satellite Control Centre. The facility at Kashgar is one of China’s oldest and in 2020 inaugurated the PRC’s first deep space antenna array system.11

Six-hundred kilometres to the west, along the road to Urumqi, lies another cluster of testing and training facilities at Lop Nur and Korla. Once hosting a CIA-operated listening station in the 1980s, the Korla missile test complex is believed to have been constructed in 2009 and has since tested ground-based interceptors and anti-satellite missiles. The development of directed-energy weapons at Korla ‘East’ has been known to analysts since the late 2000s.12 The East range also houses testing facilities for electromagnetic pulse effects, and has been involved in the development of China’s lighterthan-air programme. Korla was approximated as the origin of the infamous ‘weather balloon’ tracked across US airspace in 2023.13 The site also hosts one of China’s four ground-based large phased array early-warning radars – likely now under the command of the recently-established PLA Aerospace Force.14

Korla is situated on the western edge of the expansive Lop Nur nuclear testing area – founded in 1959 with Soviet assistance. While China officially ceased nuclear testing in 1996, satellite imagery has, since 2005, revealed construction and rehabilitation of Lop Nur’s infrastructure. In 2020, the US Department of State alleged that China was conducting nuclear tests:

potentially low-yield warheads within explosive containment chambers.15 A year later, US media revealed the construction of 110 new ballistic missile silos at Hami on the north-eastern edge of the Lop Nur testing area; a further 120 silos at Yumen along the main thoroughfare back to Jiuquan, as well as a third site in Inner Mongolia. Both the Hami and Yumen fields extend roughly 1,000 square kilometres, and Yumen is connected via additional tunnels to an adjacent rock face, suggesting the presence of an underground facility for the storage of warheads or nuclear waste.16

EXERCISES AND DEFENCE ENGAGEMENT

Annual high-profile exercises since the mid-2000s have brought combined arms brigades, including the Marine Corps, from all regions of China to the Northern WTC. Exercise brands using WTC facilities include: Stride, Joint Action and Firepower. The PLAAF’s Golden Helmet air-to-air, Golden Dart air-to-ground and Red Sword and Blue Shield air defence competitions are also held at WTC airbases. Formations

Ministry of Defence-organised International Army Games were hosted by PLA Ground Forces at Korla, and Qingtongixa has been used for joint exercises between the People’s Armed Police and their Russian and Pakistani counterparts.

typically manoeuvre by road and rail to an exercise area under an ‘electromagnetic fog’ designed to impede targeting systems, and practise ‘striking upon deployment’.17 The WTC is being used to pioneer artificial intelligence-driven aeronautical training and the 76th Group Army has been a major contributor to the development of the PLA’s new integrated digital training system.18 Exercises are generally scored and a theatrelevel party committee meets twice a year to reflect on shortcomings associated with the ‘incapabilities’ and ‘gaps’ alluded to in Xi Jinping’s speeches.19

WTC defence engagement ranges from the cross-border staff interactions with the Central Asian Republics (mandated by the 1997 agreement) to joint exercises and diplomatic events in Beijing. Korla and Jiuquan have been used for legs of the annual Shaheen-X air superiority exercise between China and Pakistan since 2011, and in 2023 and 2024 Hotan hosted the Falcon Shield joint-air exercise with the UAE. Between 2017 and 2022, various constituent exercises of the annual Russian

When the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s counter-terrorism exercise (Peace Mission) has been held in China it has typically been in the North East but the WTC has organised planning conferences and contributed troops to Russian or Central Asian-hosted iterations. The WTC also contributes troops for the Russian keynote Zapad, Tsentr and Kavkaz exercises. The conduct of part of Zapad 2021 at Qingtongxia marked the first time that Russian Federation troops had participated in a

11Deng Xiaoci and Fan Anqi Source, “China operates first deep-space antenna array system in Xinjiang region”, Global Times, November 17 2020.

12Kristin Burke, “Where are the PLA’s other laser dazzling facilities?“, China Aerospace Studies Institute, June 2023.

13“Lighter-than-air reconnaissance in China spotlighted after surveillance balloon shootdown”, Activity Analysis, Janes (2023), September 09 2019.

14Hans M. Kristensen, “China’s Strategic Systems and Programs”, in China’s Strategic Arsenal: Worldview, Doctrine and Systems, ed. James M. Smith and Paul J. Bolt, Georgetown University Press (2021), 116

15Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance, Adherence to and Compliance with Arms Control, Non-proliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments, US Department of State (2020), 49.

16“Examining construction work near Yumen and Hami”, Event Analysis, Janes (2021).

17Anushka Saxena, “Assessing Operations and jointness in the PLA Western Theatre Command”, Takshashila Discussion Document No. 2024-07, May 2024, The Takshashila Institution.

18“Chinese army begins using artificial intelligence for training pilots”, Global Times Website, June 14 2021 ; “China’s PLA ramps up digital training”, Janes, Feb 26 2025

19M. S. Prathibha , PLA’s Western Theatre Command in Transition, IDSA Issue Brief, Nov 09 2021.

strategic exercise hosted by the PLA.20 Like many joint-SinoRussian military exercises, it was timed to coincide with US naval drills, in this instance the Large Scale exercise conducted simultaneously in the South China and Black Seas.

COMMAND AND CONTROL

Under the reforms, the PLA’s provincial-grade military districts were mostly relegated to a resource planning role and command of reserves and militia under the National Defence Mobilization Committee. The Xinjiang and Tibet Military Districts, however, have been retained as deputy-theatre-grade organisations. They fall under the day-to-day management of Army national headquarters rather than the National Defence Mobilization Committee and their operational units report to the WTC’s Joint Operations Command Centre in Chengdu, which also commands WTC ground and air forces. There has existed a degree of uncertainty as to whether PLA Rocket Force missile bases and brigades deployed in the WTC are directly commanded by the theatre Joint Operations Command Centre, but the reforms saw all four services establish a presence at command posts from the military districtlevel upwards. The WTC Joint Operations Command Centre is reportedly being developed as a centre of wargaming expertise, with most of its personnel aged

35 and under, and in receipt of various scientific awards.21 All theatre commands report to the Central Military Commission’s Joint Operations Command Centre situated in a fortified underground facility West of Beijing.

The WTC has had three political commissars and four commanders since its establishment in 2016: Zhao Zongqi, Zhang Xudong (December 2020-June 2021), Xu Qiling (June-August 2021) and the incumbent Wang Haijiang. In the absence of an official explanation, the rapid succession of leaderships in 2021 invited speculation that Zhao had been dismissed following clashes with Indian forces in the Galwan Valley.22 With his extensive experience in Tibet, Zhao was portrayed by Indian media as a ruthless and ambitious general, who risked Galwan in order to avenge a similar confrontation at Doklam, in the Line of Actual Control’s Eastern Sector, in 2017.23 It later transpired, however, that both Zhang and Xu had stepped aside due to health concerns and comparative studies have highlighted that Xi Jinping has consistently rotated leaders in all theatres.

Wang Haijiang, however, is another product of the Xinjiang and Tibet Military Districts, having commanded both –the latter during the Galwan conflict. That he also served in the decorated 61st division of the 21st (now 76th) Group Army leaves open the possibility that the appointment of Xudong and Xi Qiling, whose backgrounds lie in other parts of China, was something of an interregnum. Other prominent WTC and Chengdu military region generals with corps-level experience in Western China have included

Tian Xiusi, Rong Guiqing and the present WTC and Xinjiang Military District political commissars Li Fengbiao and Yang Cheng.

Studies have refuted the idea that certain theatre commands, namely the former-Nanjing Military Region (now ETC), where Xi Jinping spent much of his early career, are a pathway to Central Military Commission membership.24 Former-vice chairman He Weidong, reportedly removed in April 2025, is the most high-profile Central Military Commission member to have had experience in the WTC, where he commanded ground forces between 2016 and 2019, albeit before taking command of the ETC. Additionally, Li Zuocheng, Chief of Staff of the Central Military Commission Joint Staff Department between 2017 and 2022, had been the commander of the Chengdu Military Region. Other high-profile careers encompassing experience in the WTC, Chengdu or Lanzhou Military Regions, mainly include political commissars: Miao Hua, current director of the Political Works Department, but also Tian Xisui, Xu Deqing, He Ping and Li Wei. The WTC has been a particularly prestigious appointment for officers in the People’s Armed Police. Wang Jianping, the now-disgraced former head of the police, had served in Tibet and Pan Changjie, and was a former People’s Armed Police Deputy Chief of Staff in Xinjiang.

In early 2025, citing an increased number of delegates at the 20th Party congress, and recent presidential visits to Lhasa, Indian media alleged that the WTC was receiving greater political attention

“ZHAO WAS PORTRAYED BY INDIAN MEDIA AS A RUTHLESS AND AMBITIOUS GENERAL, WHO RISKED GALWAN IN ORDER TO AVENGE A SIMILAR CONFRONTATION AT DOKLAM.”

from Beijing.25 This needs to be qualified. In September 2024, Xi Jinping met with senior cadres in Lanzhou, accompanied by He Weidong – the latter’s first visit to the WTC as Central Military Commission vice-chairman. While He’s predecessor Xu Qiliang made at least seven official visits to Western China, particularly during local instability in the early-2010s, Zhang Youxia has paid the WTC less attention, making an inspection in Qinghai in 2021 and visiting both Lhasa and the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre with Xi Jinping in 2021. Xi Jinping’s visit to the Urumqi PLAAF Base in August 2023 was only his second visit to Xinjiang since coming to power, having visited the Chengdu PLAAF Base one month prior. His first visit to Xinjiang in July 2022 was also preceded by an inspection of Chengdu. He makes routine party inspections of Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai, which are less politically sensitive than Xinjiang and Tibet.

XINJIANG AND TIBET MILITARY DISTRICTS

The Xinjiang Military District is geographically larger than its Tibetan counterpart, encompassing both the Aksai Chin and the Ngari Military

20Lyu Desheng and Yang Xiaobo, “Russian troops leave China after participation in Zapad/Interaction-2021”, China military Online, August 19 2021.

21Peng Xiaoming, Li Jiahao and Yang Xiaobo, “A support brigade of the Joint Command Centre of the Western Theatre Command: Study wars and become the ‘most powerful brain’ think tank”, PLA Daily, December 2022.

22Joel Wuthnow, Gray Dragons: Assessing China’s Senior Military Leadership, Centre for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies, China Strategic Perspectives, No. 16, National Defence University Press, Washington DC , September 2022, 32.

23“Ambitious General Threatens to Derail Regional Balance in Asia”, Bharat Shakti, June 21 2020.

24Joel Wuthnow, 30.

25Jayadeva Ranade, “Xi strengthens Western Theatre Command”, The Tribune India, January 16 2025.

Sub-District in Western Tibet. The Xinjiang Military District utilises combined arms divisions – a relic of the previous military region system but roughly twice the size of a brigade and able to independently conduct longrange strikes. The Tibet Military District on the other hand commands only three combined arms brigades – all stationed near Lhasa. The two military districts take the lead with disaster response and senior officers serve as members of the provincial party committees.

Approximately 15 PLA Army border-defence regiments are stationed throughout Xinjiang and Tibet under the command of prefecture-level military sub districts. Border-defence companies stationed close to the Line of Actual Control typically hold only light infantry weapons, while armoured personnel carriers and mortars may be assigned to battalions positioned in depth. Forward companies occupy modest brick barracks with defensive fighting trenches typically constructed in the adjacent hills. Due to the terrain, units can be positioned on much wider or narrower frontages than directed by PLA doctrine and horse riding remains mandatory for most border regiments. Operations in the Aksai Chin are supported by WTC intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance brigades as well as communications and motor transport units.26

In the spring of 2020, the Hotan Military Sub-District increased patrolling in the Aksai Chin, establishing outposts in the Galwan Valley and near Lake Pangong – within the limit of China’s claim but nevertheless provocative. Patrols were unarmed in line with a decadesold moratorium but a hand-tohand clash in the Galwan Valley in June resulted in the loss of 20 Indian and four Chinese soldiers. Chinese losses were

only acknowledged in February 2021 when deputy theatre command-level talks resulted in a limited disengagement. By this time, however, the Xinjiang Military District had moved the 6th Combined Arms Division to reinforce the two borderdefence regiments permanently stationed in the region. The 6th was relieved six months later by the Urumqi-based 11th, before returning in 2022 with rocket artillery, vehiclemounted howitzers and Type15 light tanks.27 In November 2022, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies reported that a ‘new divisionlevel headquarters’ had been constructed on the Sirijap Plain, inland from the north shore of Pangong Lake.28 While much of the combined arms elements have been withdrawn to the nearby garrison at Rutog, the permanent infrastructure remains in situ and can now be rapidly reinforced by a newly-constructed bridge across the lake.

A separate clash in the Doklam Valley three years earlier, initiated after Indian forces crossed the Line of Actual Control to arrest Chinese construction of a road in disputed Bhutanese territory,

drew a lighter but nevertheless prompt response. Satellite imagery revealed that a Tibet Military District light combined arms brigade established positions to reinforce borderdefence units stationed along the border with Bhutan and three 77-Group Army combined arms brigades were also surged to Tibet from Sichuan and Chongqing.29 A subsequent melee in Arunachal Pradesh, in the Line of Actual Control’s easternmost sector, in December 2022, has again been understood by outside observers in the context of aggressive Chinese border patrolling.

Since 2013, the PLA has carried out what it calls the ‘506 Special Mission’ involving rotational deployments of forces to the Line of Actual Control, both augmenting the Xinjiang Military District’s combined arms divisions and giving other PLA units an opportunity to conduct austere-environment training.30 WTC training also intensified post-Galwan, with high-altitude exercises and deployments increasingly allyear round affairs.31 Xinjiang Military District exercises have incorporated drone evasion, snowfield training, long-distance

marching using oxygen and high-altitude fire missions.32

The PLA has also attempted to enhance border security through military-civil fusion programmes – Xinjiang’s ‘Six in One’ Joint Defence and Control,

26-27Dennis Blasko, “A Baseline Assessment of the PLA Army’s Border Reinforcement Operations in the Aksai Chin in 2020 and 2021”, China Land Power Studies Centre, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College.

28Matthew P. Funaiole et al., “China Is Deepening Its Military Foothold along the Indian Border at Pangong Tso”, China Power, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, November 28 2022.

29Dennis Blasko.

30Roderick Lee and Marcus Clay, “Don’t Call It a Gray Zone: China’s Use-of-Force Spectrum”, War on the Rocks, May 09 2022.

31Lt Gen V K Saxena, The Power Behind Arrogance, Vivekananda International Foundation, June 23 2020 ; M. S. Prathibha.

32Anushka Saxena, “Assessing Operations and Jointness in the PLA Western Theatre Command” ; Anushka Saxena, “Integration in the PLA Western Theatre Command: Practices and Patterns, Article”, LifeofSoldiers.com, October 21 2024 ; M. S. Prathibha.

33Tenzin Younten, “China Boosts Security Near Indian Border By Forming CivilianMilitary Units: But It Could Backfire In Tib & Xinjiang”, The Eurasian Times, September 15 2023.

for example, and the ‘Five in One’ Border Management System in Tibet – but the schemes have been dismissed by some analysts as a largely uncoordinated, propaganda exercise.33

OTHER FORMATIONS

In contrast to the plateau region, North-West China’s first line of border defence is the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps – one of a number of such paramilitary frontier organisations established in the 1950s. The use of self-sufficient military colonies dates to the Tang period but the Qinq also used Han colonisation to secure the Western frontier. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps’ mandate has been to settle strategically-important areas, with ethnically-Han farmers who are trained as militia outside the agricultural season. Officially treated as a province-level organisation, the Corps has its own judicial system, television and radio networks, and is not subordinate to the WTC or the Central Military Commission

but to the State Council and a working group under the Politburo Standing Committee.

Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps militia were mobilised for domestic security during the 1962 Sino-Indian War but the organisation was dissolved during the Cultural Revolution. Increasing Uighur nationalism in the 1990s revived party interest in the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, which would participate in security operations during the 2009 Urumqi riots. In 2018, the Corps employed around 400,000 regimental farmers organised into 14 divisions – largely aloof from the Uighur population. The Xinjiang provincial government authorises the Corps to run several divisionlevel cities in addition to Shihezi – its headquarters – and it employs roughly 100,000 in secondary industries, including construction.34 The Corps is responsible for a significant share of Xinjiang’s cotton production,

China’s total, and was one of several Xinjiang-based entities subject to export sanctions under the Biden administration.35

It is not known how many People’s Armed Police troops are permanently based in Xinjiang, but a 2017 analysis put the number at 200,000 and the province has more regiment-sized police mobile detachments than any other.36

The People’s Armed Police is independent of the theatre command structure, reporting directly to the Central Military Commission, and the reforms removed several traditional roles such as disaster relief and border security, in order to streamline its counter-terrorism role.

to run ‘re-education camps’.

China’s West therefore plays a unique peacetime role within the order of battle of the PLA and the ongoing reforms are continuing to refine joint multi-domain operations under the WTC. The latter’s strategic direction and ability to conduct operations beyond China’s borders remain untested. The WTC’s ballistic, air and ground formations will be discussed in Parts 2 and 3, along with an assessment of their ability to project combat power into the aforementioned territories of the former Soviet Union.

34Yajun Bao (2018), The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps: An Insider’s Perspective, BSG Working Paper Series Providing access to the latest policyrelevant research, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford (2018).

35Emma Cosgrove, “Uighur labour will be tough to avoid with about 20% of cotton connected to Xinjiang: Global Data”, SupplyChainDive.com, October 1 2020.

High-ranking People’s Armed Police commanders have sat on the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps’ counterterrorism leading group and the Xinjiang government has deployed every arm of the civilian bureaucracy for security purposes, including county-level bureaus of education and forestry

36Uighur Human Rights Project, Policing East Turkistan: Mapping Police and Security Forces in the Uyghur Region, UHRP.org, December 13 2023.