BAZM O BAZAR

Architecture as a medium to restore identity, a catalyst for social interaction, and a platform for the local economy

Nigora Atta

Amsterdam University of the Arts

Mentor: Hans van der Heijden

Committee: Yonca Erkan & Milad Pallesh

December 2025

07 A personal story

09 Introduction

15 Prologue – A visit that changed everything

Chapter One

19 01 Before you read

21 02 Typologies

45 03 Timeline

57 04 Traditions

Chapter Two

83 05 Saryazdfort in its landscape

91 06 Analysis

Chapter Three

119 07 Design directions

131 08 Concept

Chapter Four

147 09 Bazm O Bazar

chapter Five

213 Acknowledgment

chapter Six

215 Bibliography

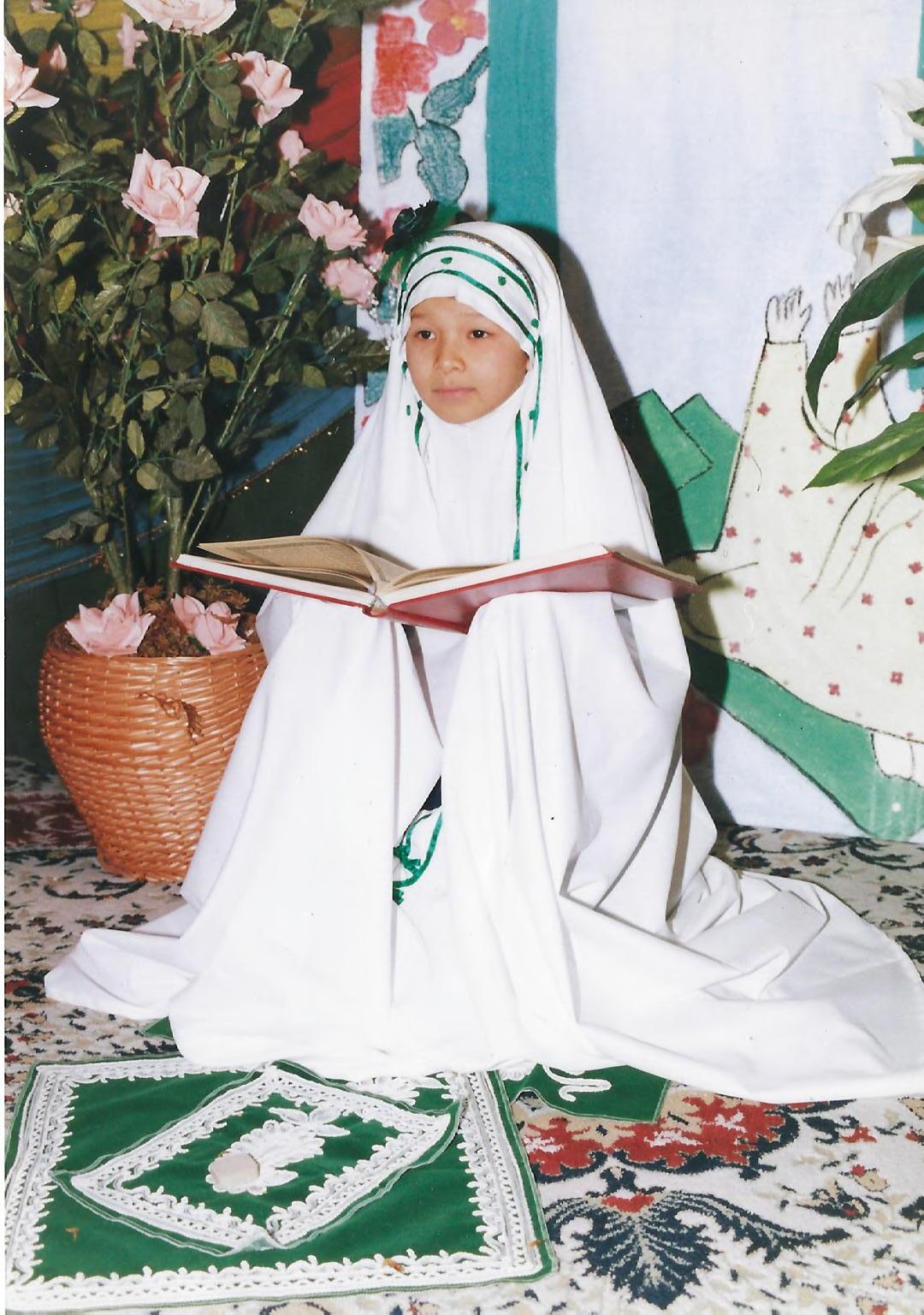

Picture on left: First day of elementary school

Picture on right: The age of taklif (religious responsibility) In Islamic culture, a girl’s ninth year is often marked as the beginning of taklif , the moment she is declared responsible, asked to cover her hair, and obligated to pray.

I grew up in a household deeply rooted in religion. From as far back as I can remember, the teachings of Islam permeated every aspect of our lives. I was just seven years old when I was first required to wear a head covering to school, a symbol of religiousness and modesty. Yet, as soon as the school day ended, I would eagerly shed this garment, feeling a sense of liberation as I stepped outside into the open air.

Each morning, before the commencement of classes, we would gather in the schoolyard to read verses from the Quran as a collective ritual. It was a daily reminder of the importance of religion in our lives, with our entire educational curriculum seemingly revolving around its teachings. Even subjects like history were not immune, often presented through the lens of religious narrative, while other aspects of our cultural heritage remained overshadowed and overlooked.

This narrow-minded upbringing felt like the only reality I knew, until the crucial moment my family made the decision to emigrate to a Western country. Suddenly, we found ourselves driven into a society where freedom of thought and expression reigned supreme. It was a big change from our strict past, where obeying was more important than being curious, and questioning authority was often discouraged.

In this new place, we met many different people, many of whom lived freely without following religious rules. It was eye-opening to see people freely express their beliefs without fear of punishment.

These things made me think a lot and made me curious about things I hadn’t thought about before. At first, this new curiosity faced resistance from both myself and others around me. The transition was filled with uncertainty, challenging the very foundations of my identity, and forcing me to confront uncomfortable truths about my upbringing. Who was I, really, and what did my past reveal about me? Did I truly belong in a society where unquestioning loyalty to religious principles was the norm, and critical thinking and questioning were discouraged?

As I grasped these existential questions, I couldn’t help but wonder: if our beliefs were so steadfast, why were we afraid to delve deeper? What truths lay hidden beneath the surface, waiting to be uncovered? It was a scary prospect, but one that I couldn’t ignore. Now, as I approach my graduation and prepare to launch my career as an architect, I’m filled with a greedy curiosity and a passionate desire to delve deeper into our past. I am excited to discover valuable aspects of our architecture and culture that have been hidden or overlooked due to the passage of time and longstanding traditions.

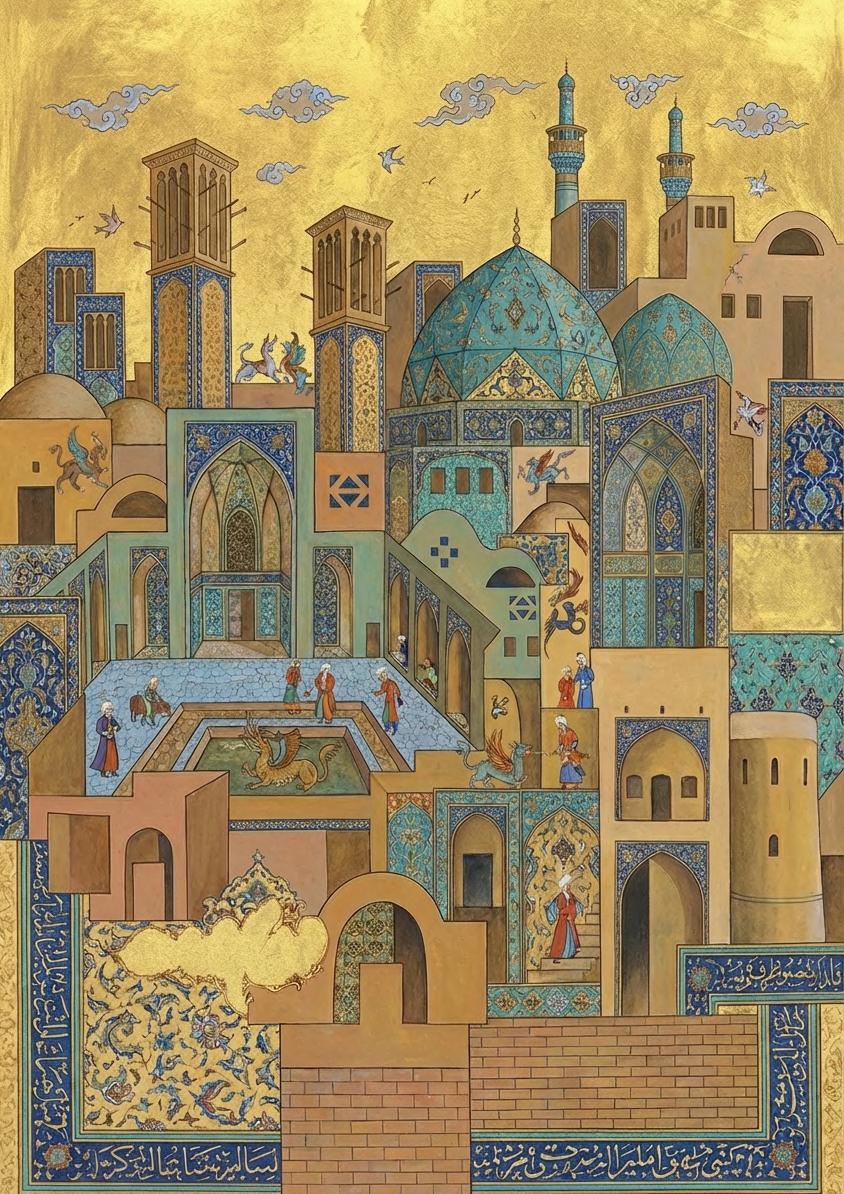

Introduction

Since the 1979 revolution, many things in Iran have changed including the way we learn, create, and live. The government began shaping education, art, and culture based on Islamic rules. Prayer became part of school life. Arabic and religious studies took more space in classrooms. Persian art, once full of human figures and sculptures, turned toward calligraphy and geometric patterns. Many ancient temples became mosques. These changes slowly covered up parts of Iran’s deeper, older heritage.

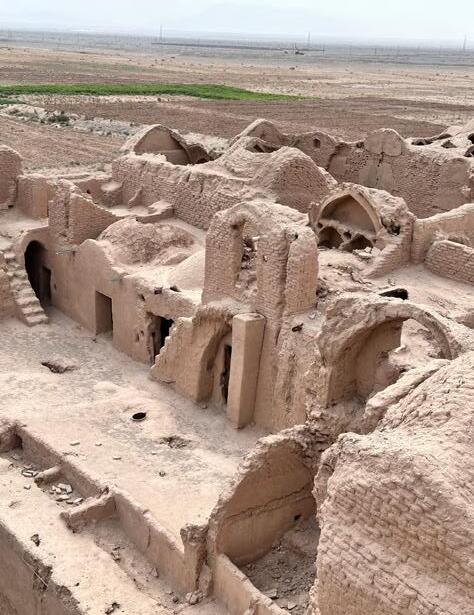

Today, political and religious priorities still influence which parts of our history are saved. Mosques and religious buildings receive funding and care. But many non-religious sites even important ones are left without support. Beautiful examples of Persian architecture often sit in silence, forgotten.

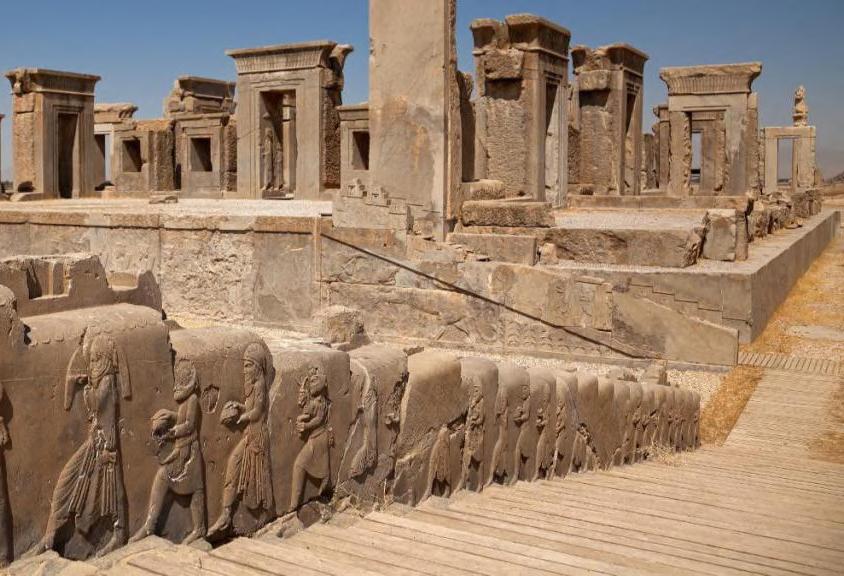

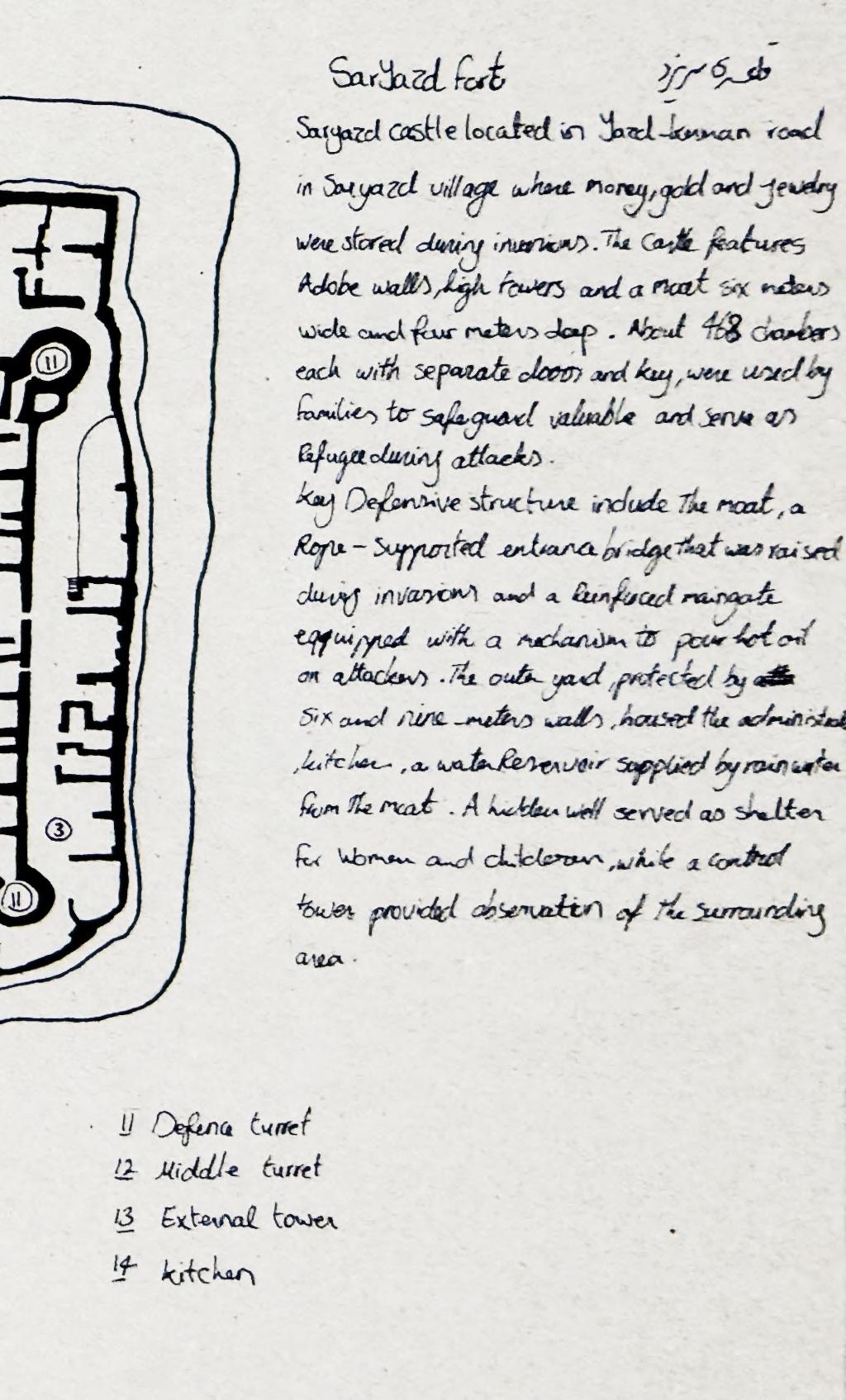

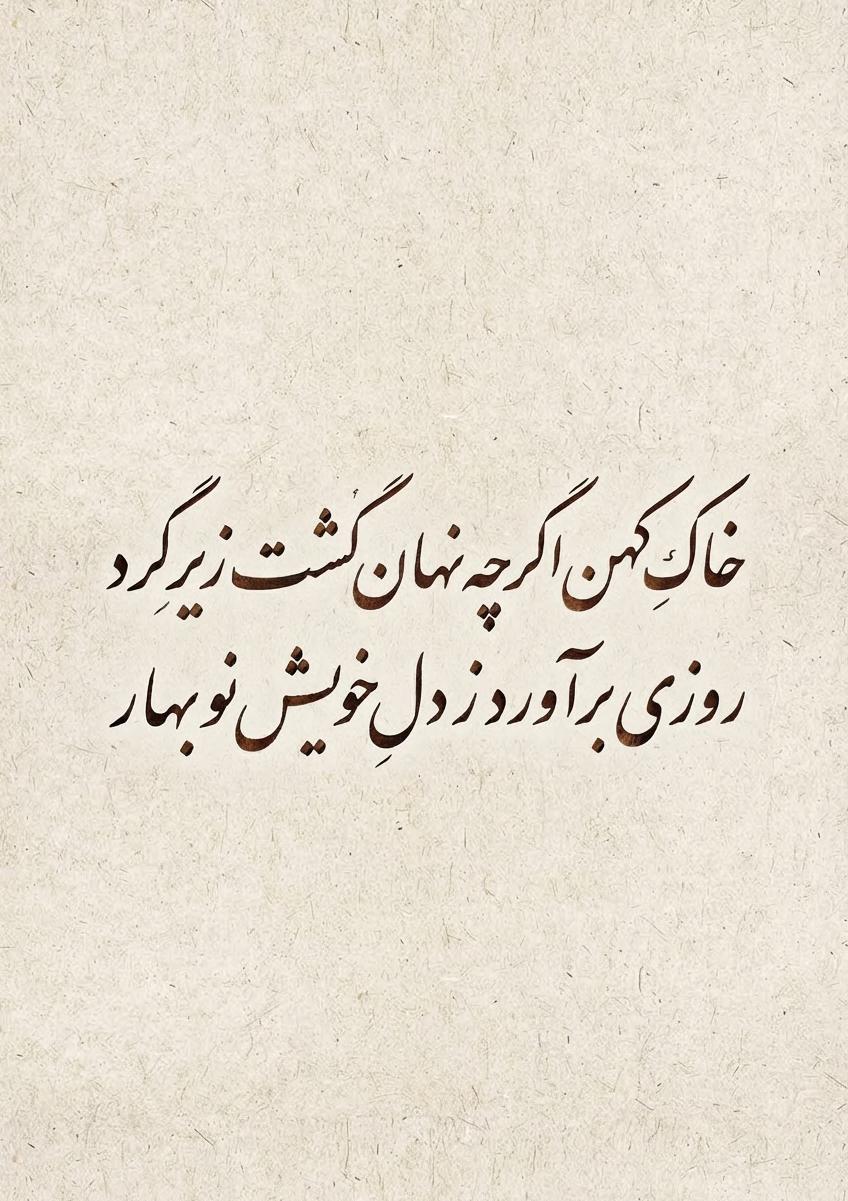

One of these places is Sar Yazd Fort, a historic structure located in the village of Saryazd, near Yazd. Long ago, it was a stop along the Silk Road a meeting point for travelers, cultures, and trade. The fort is part of our identity. But like many old places, it now struggles to stay alive. Without enough attention and care, it risks disappearing.

This project is not just about giving Saryazd fort a new function. It’s about making it relevant again reintroducing it into the everyday life of the village and its visitors.

This lead to the core question behind my design:

How can Saryazd Fort become part of everyday life again?

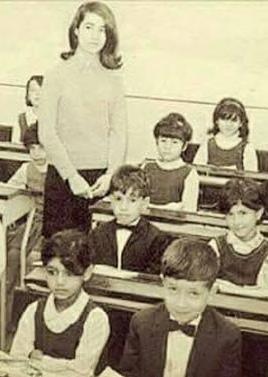

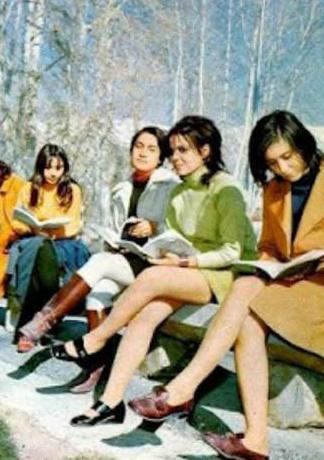

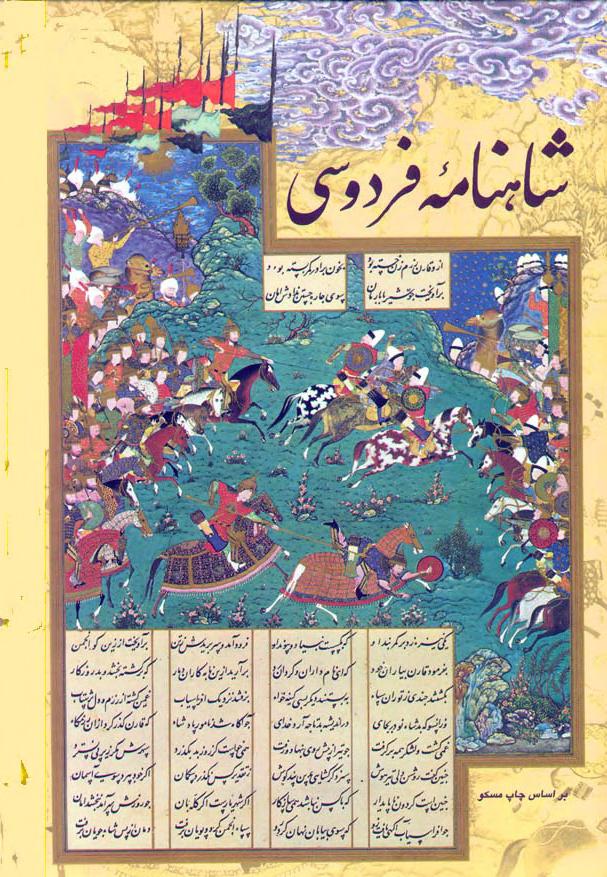

All images on the left show Iran before the Islamic Revolution; those on the right reflect changes after 1979.

First row: Classroom before and after Islam Before: Boys and girls studied together in the same classrooms.

After: Gender segregation became mandatory; schools were divided by gender.

Second row: Before: choice, after: control Before: People chose their clothing freely, based on culture and personal style. After: Hijab became compulsory for women

Last row: Losing our own, learning what’s not ours

Before: Persian culture was shaped by works like Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, even if it wasn’t part of school education.

After: Learning the Quran became mandatory in all schools, replacing attention to Iran’s own heritage.

Political priorities shaped by Iran’s Islamic identity heavily influence which historical sites are preserved. While religious monuments receive significant attention and funding, many non-religious landmarks are neglected. Traditional Persian architecture, once a national source of pride now struggles for recognition amid internal conflict and ideological control. Across the country, we are witnessing the slow erosion of our architecture, art, and culture rooted in the pre-Islamic era.

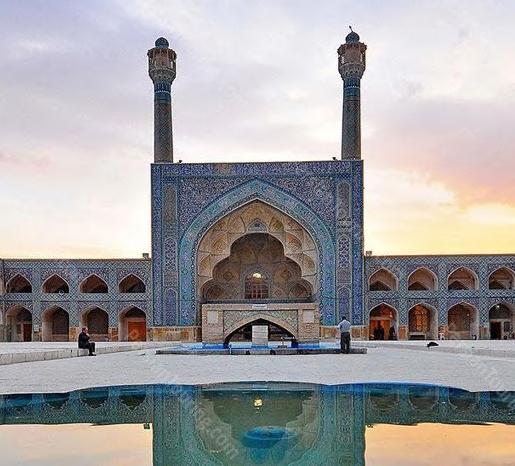

All images on the left show non-religious heritage with well-funded Islamic monuments on the right.

First row: Tomb of Cyrus and Jame Mosque of Isfahan.

Second row: Sasanian Royal City and Nasir alMulk Mosque.

Last row: Sar Yazd Fort vs. Jame Mosque of Yazd

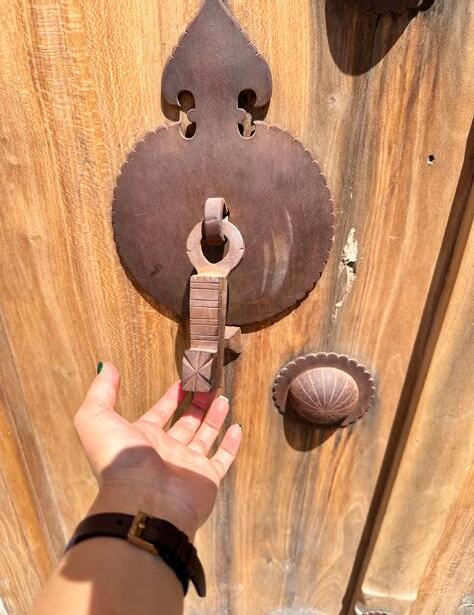

During my visit to Saryazd, the first thing that struck me was its distance not just from the city of Yazd, but from everything else. We left our hotel early in the morning to avoid the midday heat, which in this dry, harsh climate can be unbearable. By the time we arrived, we were already tired and hungry, and to our frustration, everything was closed. The keyholder of the fort was two hours late. The heat, the silence, the waiting, it all added to a sense of isolation.

As we walked through the village toward the fort, we passed pomegranate trees leaning over villa walls, farmlands stretching quietly, and streets empty of people. I couldn’t tell what mattered to the community or how they survived. The place felt paused in time.

But on our way back, something shifted. A small supermarket had opened. We stopped for tea, coffee, and cake, and ended up having a warm and eye-opening conversation. That moment changed everything. I learned that Saryazd isn’t always this empty. It becomes alive three times a year: during Nowruz, Muharram, and the Pomegranate Festival. People come to celebrate the new year, to mourn, and to honor their harvest. During these times, the village fills with life.

Suddenly, I understood: The problem isn’t the distance. People will come even from far away when they feel that something valuable is happening. The real problem is that this value remains hidden most of the time. Meaning, heritage, and life are present but invisible.

Just like the fort itself full of stories, yet slowly disappearing.

That’s why I’m doing this project.

Not just to preserve a historic site, but to help bring it back into everyday relevance.

To make the fort a place where life happens again. Where people gather not only for festivals, but for daily rhythms like walking, resting, shopping, talking.

To offer Saryazd not just protection for its past, but a visible presence in the present.

To understand a place, we must first understand its people, its culture, and the spaces they shape.

This chapter is divided into four parts.

01. Before you read

It begins with a list of terms and concepts that may be unfamiliar to the reader, offering definitions for words and region-specific elements of Persian architecture and culture.

02. Typologies

It then turns to the architectural typologies found in Yazd, highlighting a range of elements from courtyards and badgirs to materials and spatial logic all shaped by climate, geography, and culture.

03 Timeline

This section zooms out to trace the architectural eras of Iran, offering a timeline from the Sasanian period onward to show how shifts in power, religion, and identity have influenced the built environment.

04 Traditions

The last part explores the traditions that define daily life and seasonal celebrations in the region.

01. Before you read

Achaemenid: Ancient Iranian empire (550–330 BCE), creators of early Persian gardens and monumental architecture.

Ali Qapu: A Safavid palace in Isfahan known for its tall porch and music hall.

Amesha Spentas: Seven divine beings in Zoroastrianism, each representing a force of nature or virtue.

Ayvan / Eyvan: A vaulted hall open on one side, facing a courtyard.

Badgir: A traditional windcatcher tower used for natural ventilation and cooling.

Bāzār: A traditional marketplace consisting of shops, lanes, and covered passages.

Bazm: A festive gathering with music, poetry, and celebration.

Chahar Bagh: A Persian garden plan divided into four parts by water channels.

Chahar Tagh (Čahārṭāq): A square, domed structure with four arches; a core Sasanian architectural form.

Chehel Sotun: A Safavid pavilion in Isfahan, famous for its reflecting pool and mirrorwork.

Courtyard: An open-air central space in a building, providing light, airflow, and social space.

Dome on Squinches: A method for placing a round dome on a square room using architectural corner supports.

Firuzabad: A Sasanian city known for early palatial architecture and chahar-taq structures.

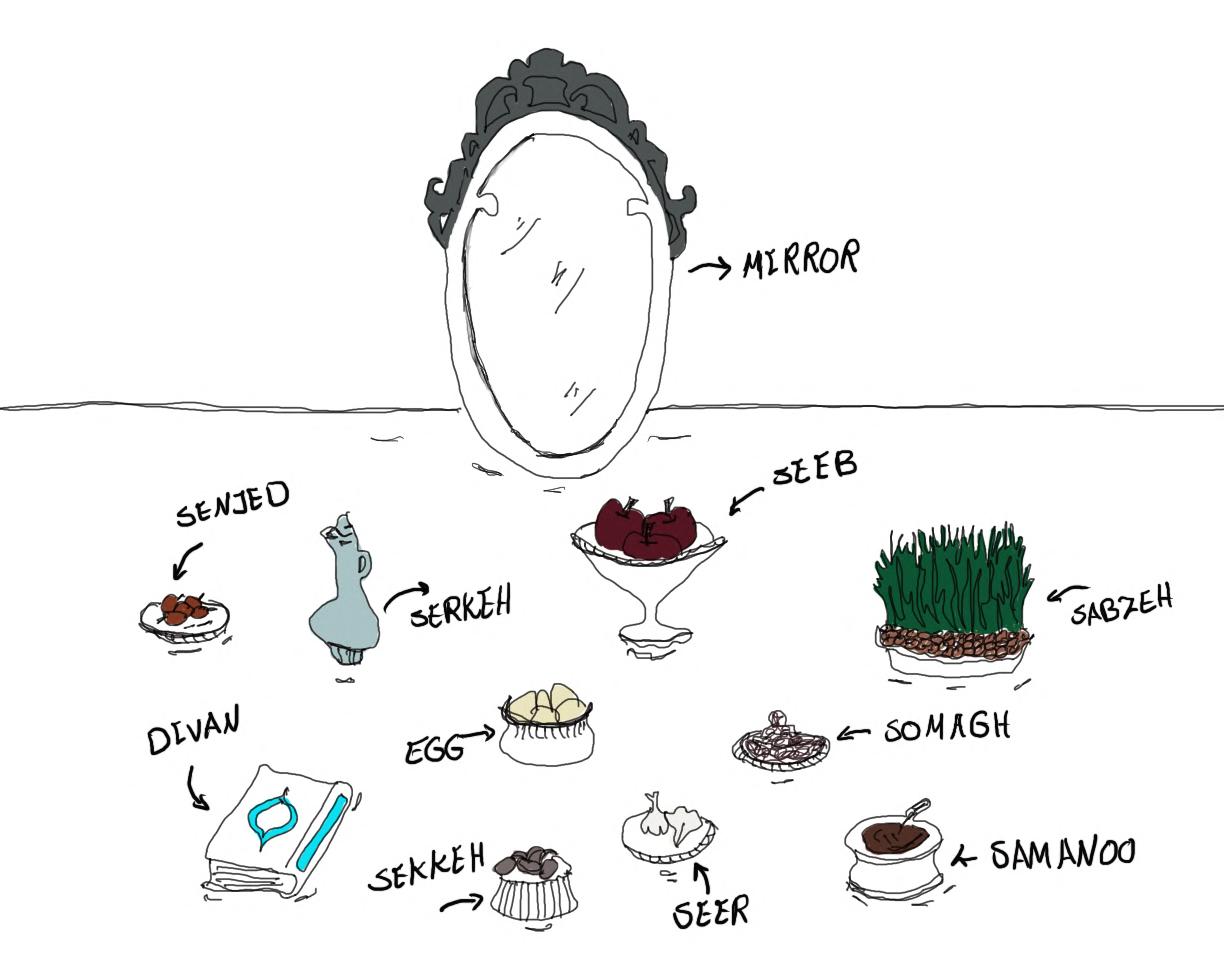

Haft-Sin: The Nowruz table containing seven symbolic items beginning with the Persian letter “S.”

Iranica: Encyclopaedia Iranica, an academic reference work on Iranian history and culture.

Iwan / Eyvan: (duplicate kept intentionally— many readers confuse the two)

A monumental vaulted hall open to a courtyard.

Khesht / Mudbrick: Traditional sun-dried bricks used in Iranian architecture.

Mahram / Muharram: The first month of the Islamic calendar, marked by mourning rituals for Imam Husayn.

Masjed: Mosque in Persian.

Mazhar: The outlet where qanat water emerges above ground.

Nowruz: Persian New Year, marking the first day of spring.

Palm-Nakhl (Nakhl): A large wooden structure carried in Muharram processions representing Imam Husayn’s symbolic coffin.

Payab: A deep underground chamber giving access to qanat water for cooling, washing, and rest.

Qajar: Iranian dynasty (1789–1925) known for revival architecture, mirrorwork, and palace ornamentation.

Qanat: An underground tunnel system transporting groundwater using gravity.

Qanat Water: Cool, flowing groundwater moving through a qanat.

Sasanian: Iranian empire (224–651 CE) known for domes, vaults, and chahar-taq architecture.

Seljuq: Medieval Iranian dynasty (11th–13th centuries) that developed the four-iwan mosque plan.

Shahnameh: The Persian epic poem by Ferdowsi, containing myths like the story of Siavash.

Shavadan / Shavadoon: Local term for Payablike underground rooms in Dezful.

This section introduces architectural elements and systems that are commonly found in the city of Yazd. These features have been shaped both by environmental factors such as climate and geography and by cultural values and traditions. It begins with broader, more public elements and systems such as the qanat and windcatcher, and gradually zooms into the more intimate components of residential architecture.

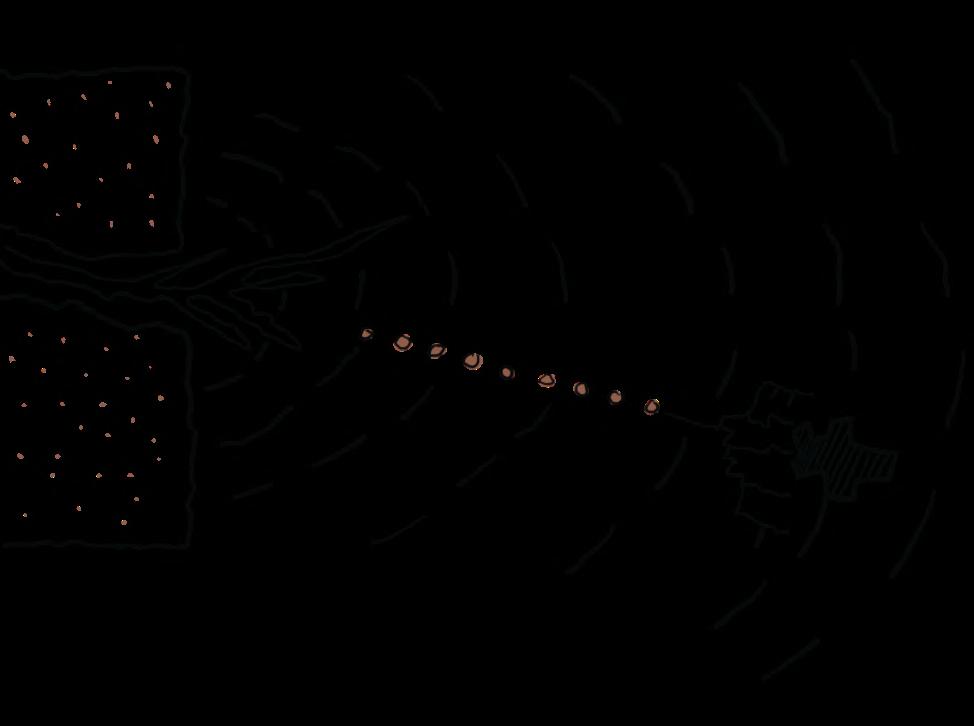

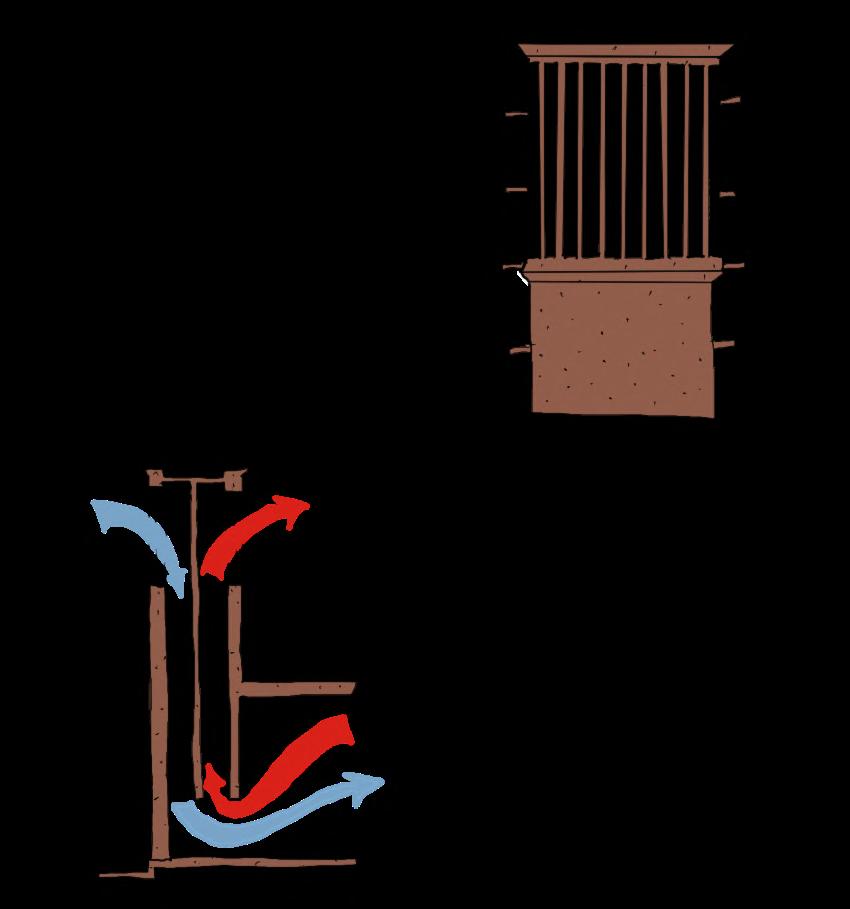

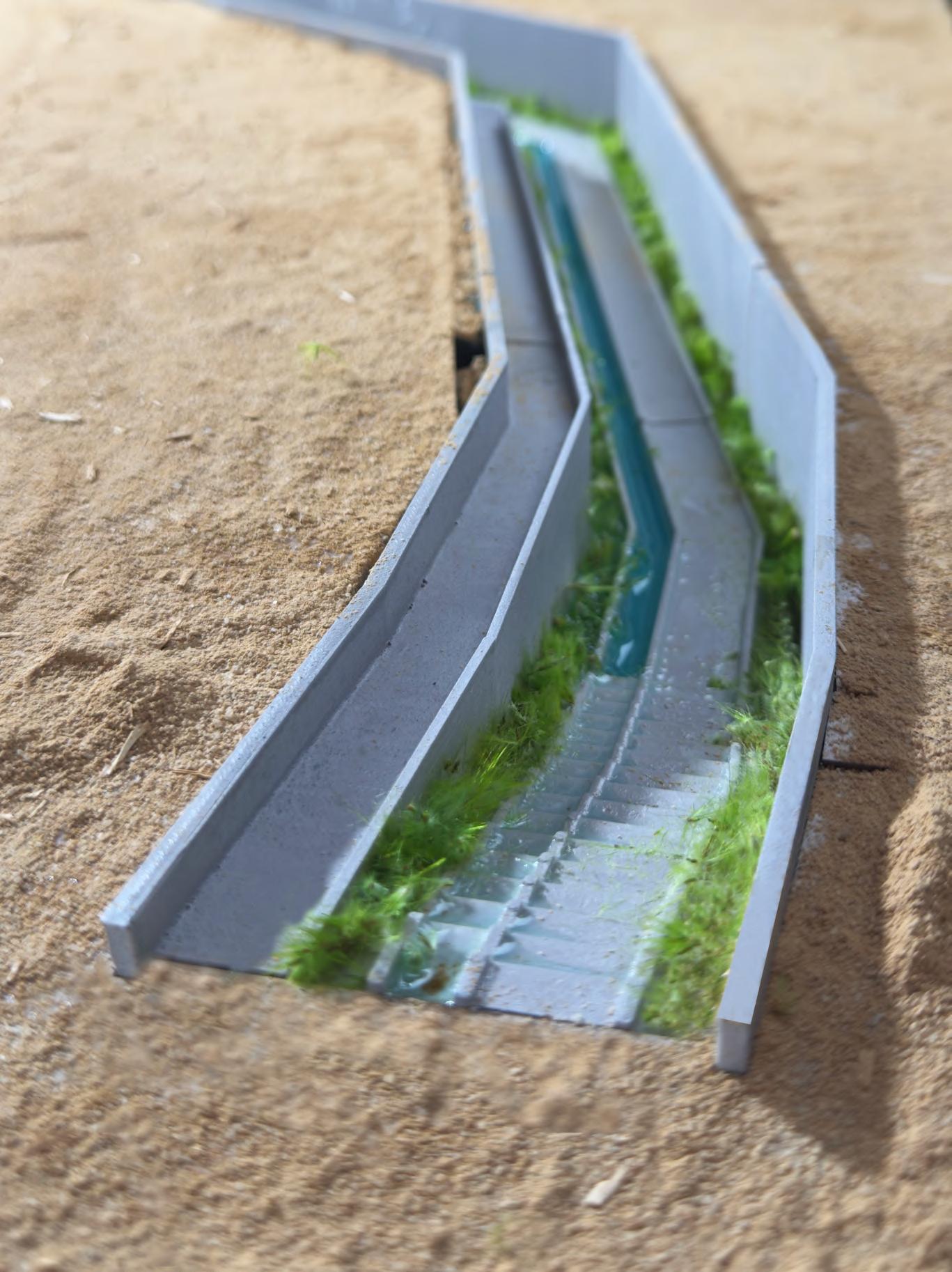

A qanat is a traditional subterranean water management system developed to provide a sustainable supply of groundwater for agricultural, domestic, and industrial use, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions (Taleghani, Tenpierik, & Dobbelsteen, 2012). Originating in ancient Persia (modern-day Iran), the qanat system is considered one of the earliest and most sophisticated methods of groundwater extraction and distribution using passive engineering (Beigli, n.d.).

The qanat consists of a gently sloping underground tunnel that taps into an aquifer at a higher elevation and conveys water, by force of gravity, to the surface at lower elevations (Taleghani et al., 2012). The tunnel is constructed by digging a series of vertical shafts (called mother well access shafts) that facilitate both excavation and ventilation.

These shafts, spaced at regular intervals along

the length of the tunnel, allow workers to remove soil and debris and provide access for maintenance (Beigli, n.d.). Water flows through the tunnel without the need for mechanical pumping, which minimizes energy consumption and reduces evaporation losses compared to surface canals. The final outlet of the qanat is typically located in agricultural fields, gardens, or settlements, ensuring a constant and reliable flow of water (Taleghani et al., 2012).

Key components of a qanat include: Mother well: A deep vertical shaft that reaches the water table.

Underground gallery (tunnel): A horizontal or slightly sloped conduit that transports water.

Vertical shafts: Used for excavation, ventilation, and maintenance.

Outlet (Mazhar): The point where water emerges at the surface.

Water table: The water table is the natural underground level at which the ground becomes fully saturated with water.

The efficiency and sustainability of qanats stem from their ability to balance water withdrawal with natural recharge rates, making them particularly well-suited for long-term water management in environments with limited rainfall and high evaporation (Taleghani et al., 2012).

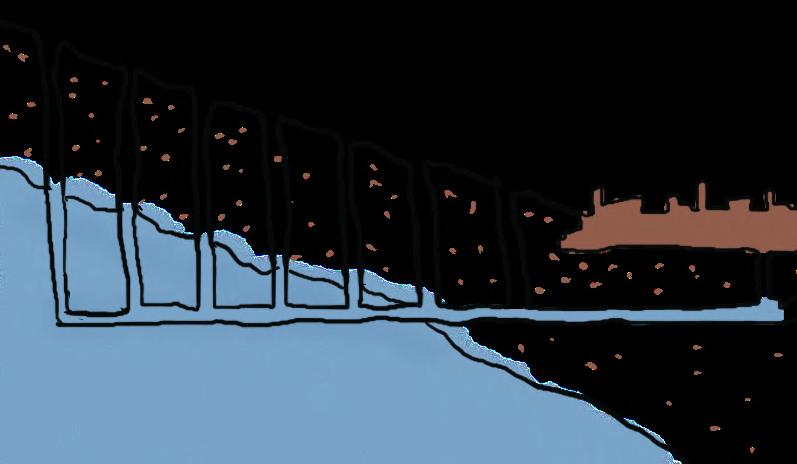

A payab is a deep chamber in traditional Iranian architecture, built around twelve to seventeen meters below ground level, designed to provide direct access to the cool, flowing water of a qanat (Beigli, n.d.). The payab is an underground room reached by a long staircase descending from the courtyard or interior of a building (Taleghani, Tenpierik, & Dobbelsteen, 2012).

Inside the payab, the temperature is naturally low—typically between 17 °C and 23 °C—due to the depth and the thermal stability of the surrounding earth (Beigli, n.d.). The qanat water passes through the chamber, allowing residents to collect clean water for drinking, washing, and ritual purification. Because the water remains in constant motion, it is naturally filtered and protected from contamination (Taleghani et al., 2012).

In some cities, such as Dezful, the payab is also known as shavadan or shavadoon. According to researchers, the Qajar and Pahlavi eras (1785–1979) represent the peak of payab/ shavadoon use, but with increasing urbanization and technological developments, these spaces were gradually abandoned. By the late 1970s, payab/shavadoon construction had ceased entirely. When the Iran–Iraq War began in 1980 and missile attacks targeted Dezful, shavadoons were repurposed as civil defense shelters, but afterward they again fell into disuse (, n.d.).

What is Badgir (windcatcher)?

Badgir is an architectural element designed to create natural ventilation in buildings using wind flow, a technique used in Iran for many centuries (Movahed, 2016). It consists of a vertical shaft with vents above the roof of a building that guide desired wind into interior living spaces to provide thermal comfort. The windcatcher is typically used to cool a house by generating a natural air-conditioning effect in one of the main rooms (Foroughi, Andrade, & Roders, 2024).

The city of Yazd in Iran is best known for its extensive use of badgirs. These structures are built so that their openings can be oriented to catch wind from multiple directions. As air travels down the tower, it cools and becomes cleaner, providing ventilation and thermal comfort to the rooms below (Mahmoudi Zarand, 2007).

Badgirs appear in a variety of shapes, including circular, octagonal, polygonal, square, and rectangular forms. Their designs differ depending on regional needs: some capture wind from only one direction, others from two, and in cities like Yazd they are often built with four or even eight openings to catch wind from all sides (Movahed, 2016).

Badgirs are typically constructed from mud or mudbrick, using mixtures of soil, earth, straw, and stone, and their surfaces are often finished with simple decorative features.

Altogether, they represent a remarkable example of how Iranian architecture harnessed natural energy long before mechanical cooling systems existed, transforming environmental challenges into architectural innovation (Foroughi et al., 2024).

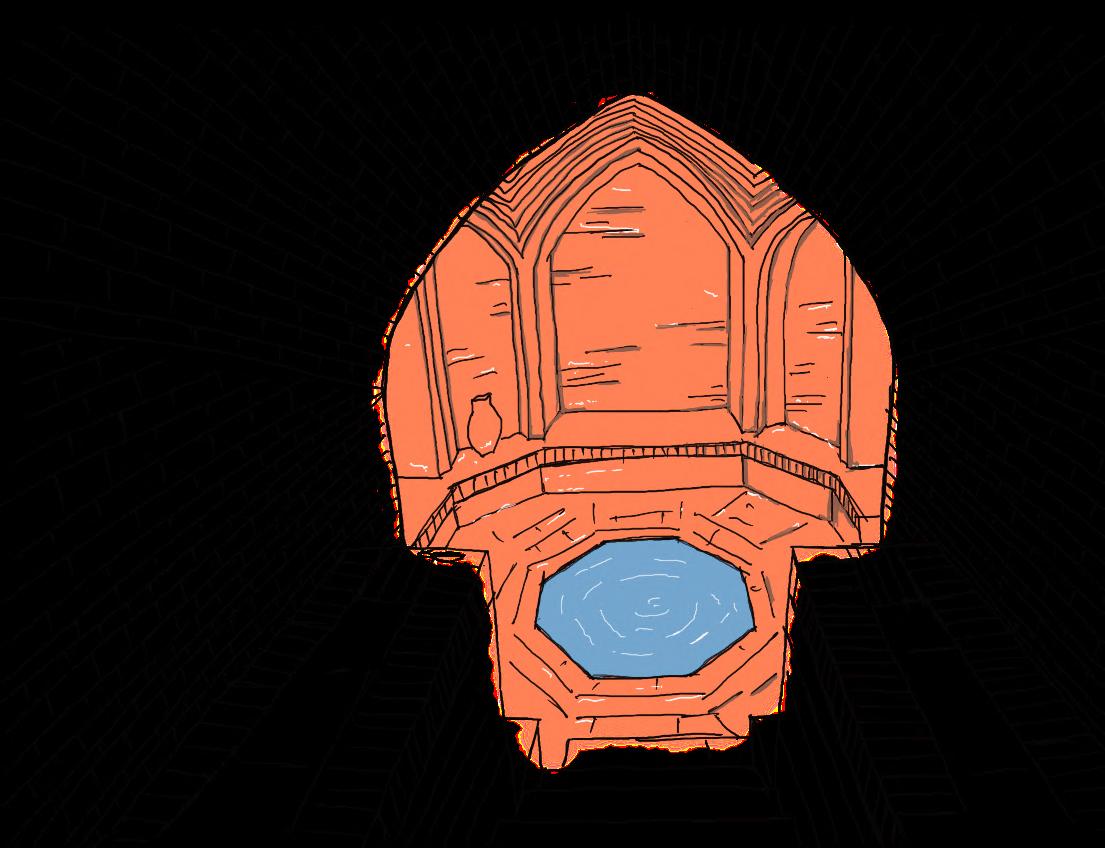

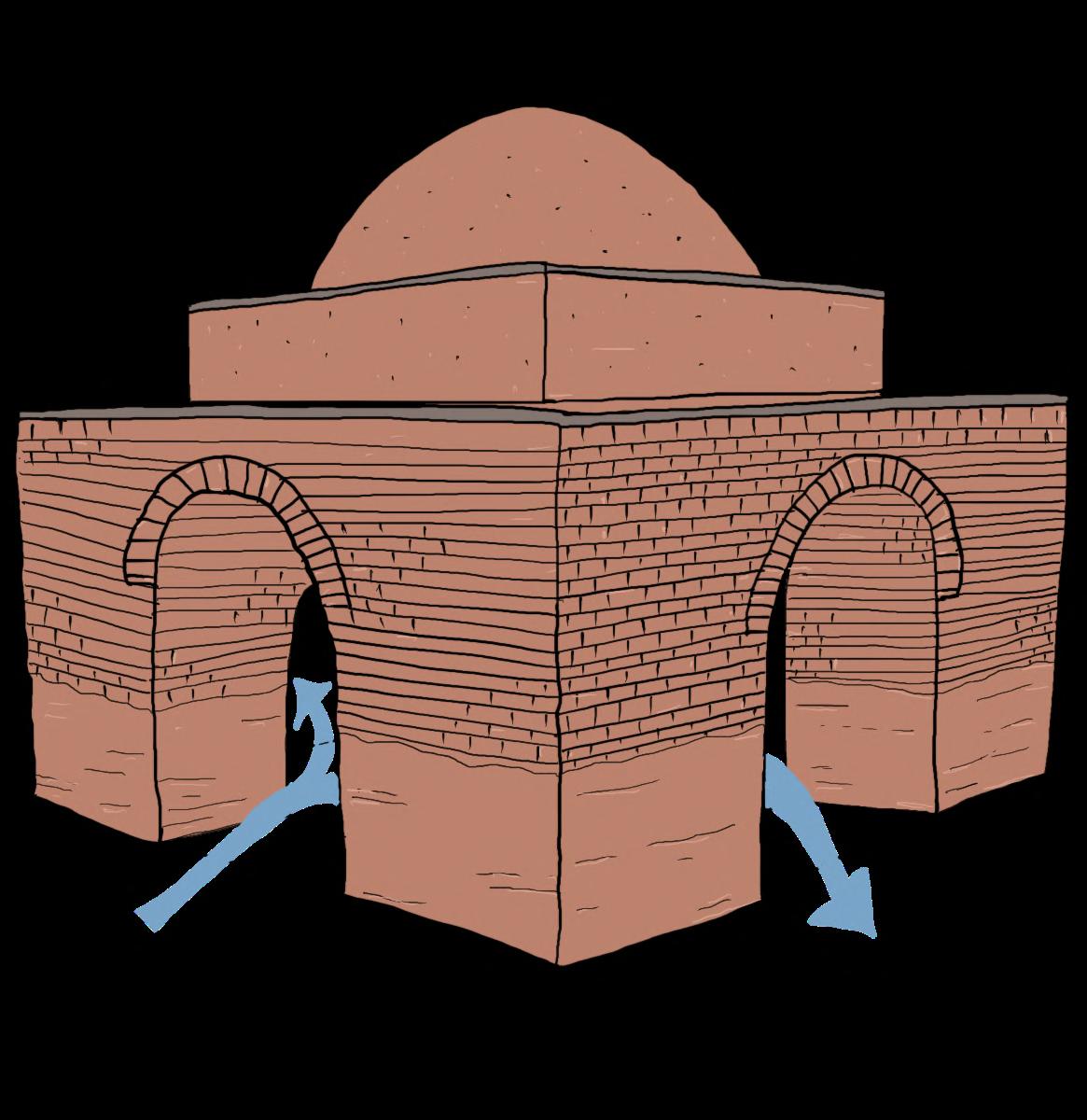

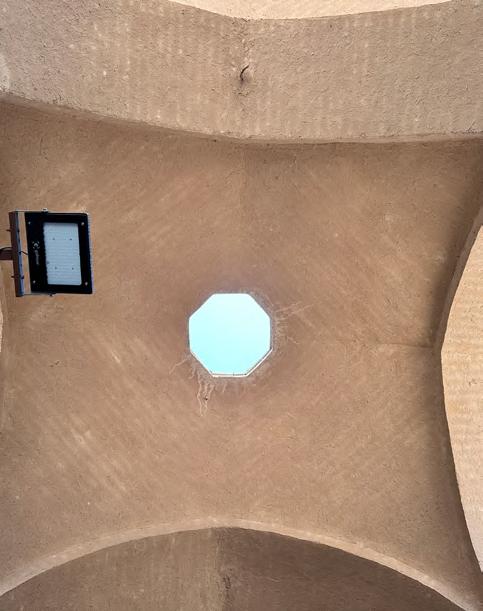

Chahartaq, meaning “four arches,” refers to a square architectural space defined by four supporting piers, four openings on each side, and a dome covering the central square, producing a cross-shaped interior layout (Huff & O’Kane, 1990). This form is one of the most recognizable and enduring elements of Iranian architecture and became second only to the ivan in importance (Huff, 1986).

Although the idea of covering a square room with a dome existed earlier in the Near East, the fully developed chahartaq appears in Iran during the early Sasanian period in the 3rd century CE. The earliest clear examples come from the royal complex at Firuzabad, built under Ardashir I (Huff, 1986). From this point onward, the chahartaq became a standard architectural unit and was used continuously for more than 1,500 years in both religious and secular buildings (Huff & O’Kane, 1990).

One reason for its widespread use is its structural advantage. The four arches and supporting piers create a strong, balanced framework that can easily carry the weight of a dome. This allowed architects to span large interior spaces without wooden beams (Huff, 1986). The layout also has strong spatial clarity: it provides a central, illuminated core with four symmetrical openings, making it suitable for fire temples, audience halls, palaces, shrines, and later Islamic domed chambers (Huff & O’Kane, 1990).

Over time, many chahartaqs came to be misunderstood as free-standing fire temples, but archaeological evidence shows that they were always enclosed within larger building complexes (Huff & O’Kane, 1990). The chahartaq was not a single building type but a flexible architectural unit that could be adapted to different functions (Huff, 1986).

In essence, the chahartaq represents a major architectural innovation of the Sasanian era. It offered structural stability, a powerful geometric form, and a monumental interior space that shaped Iranian architecture well into the Islamic period (Hillenbrand, 1986).

The geometrical structure of ChaharTaq. (a) Baze Hoor fire temple, Arsacid period (Kowkabi 2018). (b) Zahhak Castle, Arsacid period (Shamekhi, n.d.); (c) Chartaqi of Neyasar, late Arsacid period (Derafsh Kaviani, 2008); (d) Chahartaqi of Kheirabad Sassanian period (Pourfaraj, 2005); (e) Ateshgah of Baku 17-18 th century (Taylor, 2004).

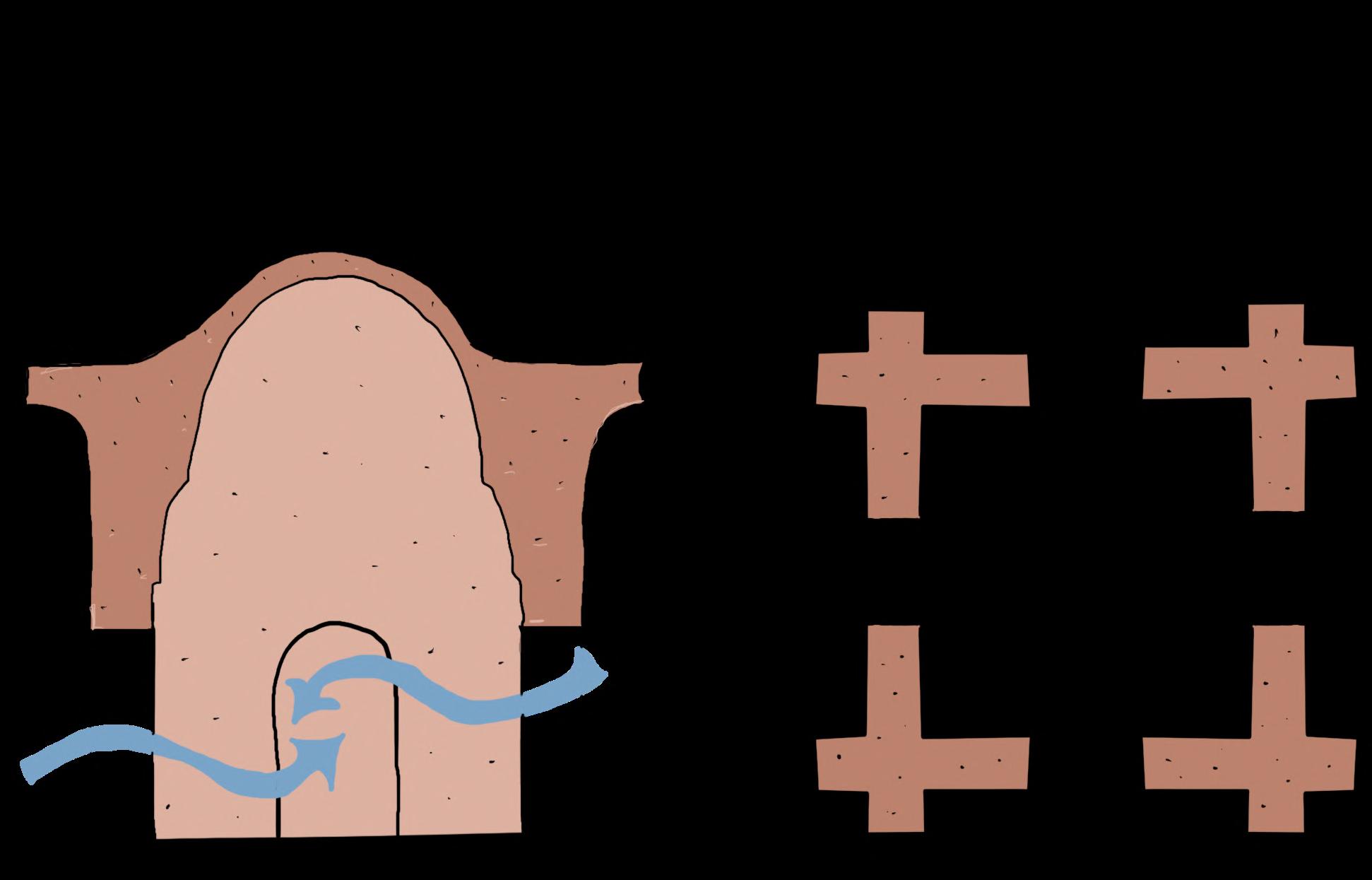

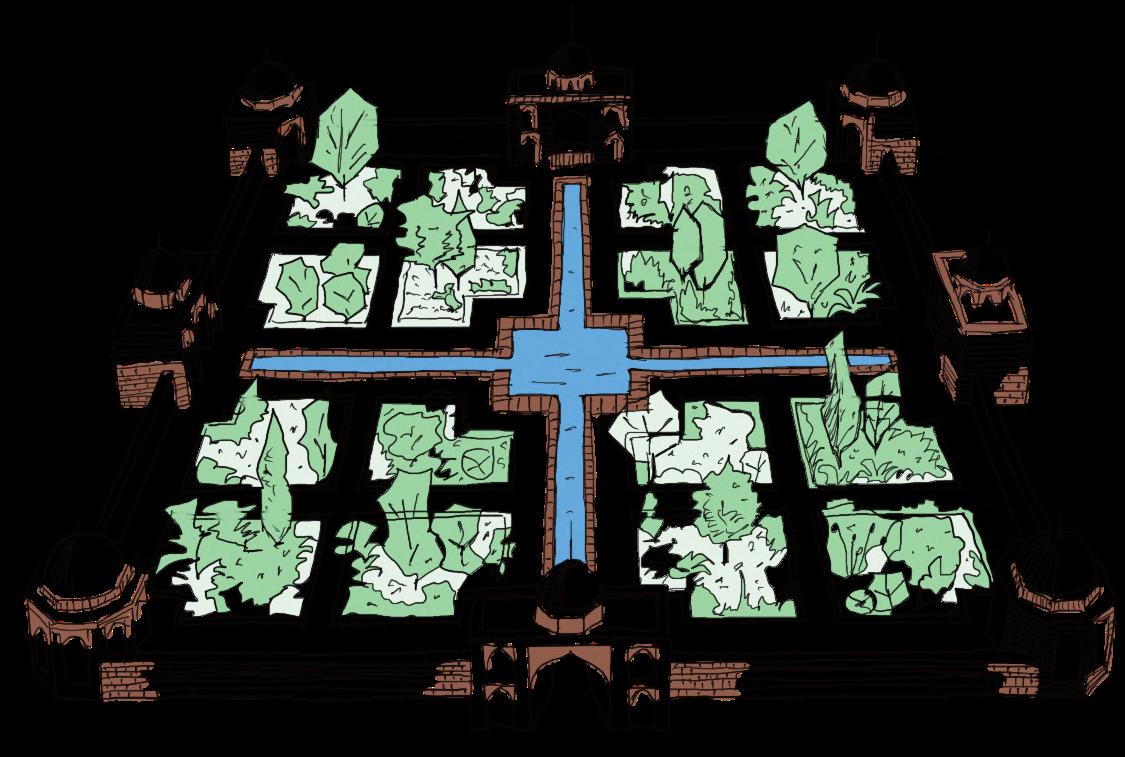

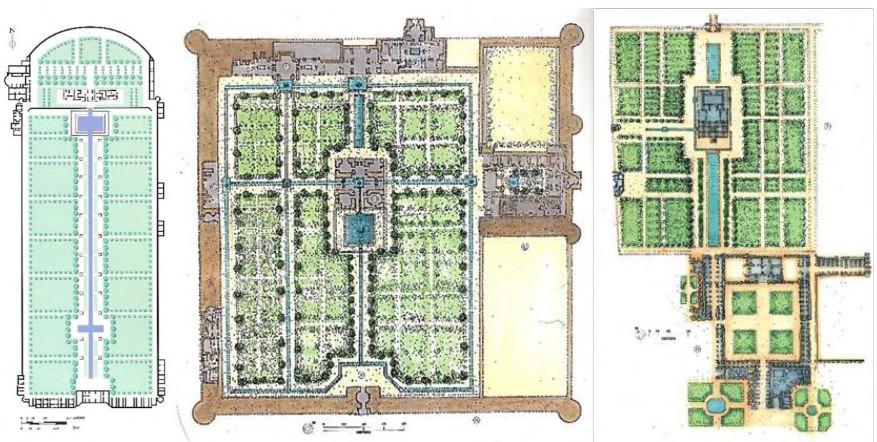

What is ChaharBagh?

The Persian garden, known as pardis or paridaiza meaning “walled garden,” is one of the most important cultural and architectural traditions of Iran (Mahmoudi Farahani, Motamed, & Jamei, 2016). Its earliest known example dates to the Achaemenid era around 600 BCE at Pasargadae, where Cyrus the Great established a garden based on the Zoroastrian division of the world into four parts and the four sacred elements of water, wind, fire, and soil. This early form developed into the classical chaharbagh pattern, in which a rectangular garden is divided into four quarters by intersecting water channels (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016)

Structure

Most gardens follow a rectangular plan subdivided into smaller squares, creating a grid that organizes water, vegetation, paths, and architectural elements (Saiwalla, 2020). This geometric clarity does not follow Western perspective views but pursues unity, order, and harmony (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016).

Pavilion or Kooshk

The intersections of the garden axes define the placement of the main architectural structure: the Pavilion or Kooshk. This building is the spiritual and visual center of the garden and is usually positioned either in the center or at onethird of the main longitudinal axis (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016). The pavilion provided a place for rest, governance, ceremony, and contemplation Symmetry is one of the defining principles of Persian garden design.

The arrangement of paths, water channels, pools, and trees creates a balanced composition on both sides of the central axes (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016). The pavilion, the water pools, and the long straight paths reinforce this symmetrical order. At the same time, natural elements such as trees introduce slight variations, creating a dynamic balance between crafted order and organic growth expressing the idea of unity within diversity, a central philosophical value in Persian culture (Saiwalla, 2020).

Hierarchy in Persian gardens appears in the sequence of movement from the entrance toward the center. Visitors pass through long straight paths lined with tall trees, gradually approaching the pavilion, the focal point of the garden (IranTourismer, 2019). The main water axis often runs along this route, emphasizing progression, arrival, and the transition into a protected inner paradise (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016).

Water

Water is the lifeblood of the Persian garden. In the dry climate of Iran, water is both sacred and practical. The garden uses water in multiple forms—flowing streams, still pools, fountains, and narrow channels—to cool the air, irrigate plants, and provide sound, reflection, and symbolism (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016). The garden is often shaped around its water supply, especially when connected to qanats that bring water from distant mountains (Saiwalla, 2020). Without water, the Persian garden loses its meaning.

Enclosed walls and the role of Shah

The enclosing walls are one of the defining features of Persian gardens. These thick, high walls create an inner world of shade, greenery, and water, protected from the harsh climate and from outside intrusion (Mahmoudi Farahani, Motamed, & Jamei, 2016). This introverted structure reflects a long-standing Iranian architectural tradition in which paradise is understood as an inward, guarded space (Huff, 1986). In traditional Iranian thought, the garden was not only a place of beauty but a symbol of an ordered and protected world. The responsibility for guarding this paradise ultimately belonged to the Shah, whose role was to preserve harmony, fertility, and the well-being of the land (Saiwalla, 2020). The walls therefore supported this idea by enclosing and safeguarding the garden, allowing the paradise within to flourish (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016).

In essence, the Persian garden is a complete cultural and philosophical system expressed through architecture, geometry, water engineering, and landscape (Mahmoudi Farahani et al., 2016). It is not only a place of aesthetic pleasure but a physical expression of cosmology, kingship, spirituality, and environmental adaptation (IranTourismer, 2019).

Developed from the Achaemenid period and refined through Sasanian, Timurid, Safavid, and Qajar eras, the Persian garden stands as a unified model where structure, nature, meaning, and human experience are woven into a coherent whole (Saiwalla, 2020).

The geometrical structure of Persian garden Plan. (a) Shahzadeh-Mahan Garden. Kerman (Hobhouse 2003); (b) the Plan of Fin Garden, Kashan (Khansari et al. 1998); (c) the Plan of Chehel Sotun Garden, Esfahan (Khansari et al. 1998). @ Persian gardens: Meanings, symbolism, and design (2016).

What is Apadana / Eyvan / Ayvan?

An Eyvan (ayvān) is a (large), vaulted hall that is closed on three sides and open on one side, usually facing a courtyard (Grabar, 1986). In classical Persian and Arabic texts, the word often refers to a palace or to the most important ceremonial hall within a palace, especially the main reception or audience space. Over time, the term also became the technical name for this specific architectural form. The famous Sasanian palace at Ctesiphon, known as Ayvān-e Kesrā, is one of the best-known early examples of such a monumental Eyvan (Huff, 1986).

Functionally, the Eyvan marks spaces of importance, transition, and representation. It frames the approach to a courtyard, emphasizes major axes, and creates a monumental threshold between inside and outside (Grabar, 1986). In palaces, it served as the main audience hall; in religious and educational buildings, it became the principal space for gathering, teaching, and ritual focus. Developed in the Parthian and Sasanian eras and refined throughout the Islamic period, the eyvan is one of the most distinctive and enduring forms in Iranian architectural history (Huff, 1986).

As an architectural element, the Eyvan has been a consistent feature of Iranian architecture since Parthian times. It appears in pre-Islamic palaces and continues into the Islamic period in mosques, madrasas, shrines, caravanserais, and houses. In mosques it is often called soffeh. A single Eyvan is frequently combined with a domed hall, but its most characteristic use is in the four-eyvan plan, where four eyvans are placed on the sides of a central courtyard (Hillenbrand, 1986). This composition became a key organizing device in Iranian architecture, structuring both the spatial hierarchy and the decorative focus of buildings. Important examples include the Great Mosque of Isfahan and later Timurid and Safavid monuments such as the madrasas and mosques of Samarqand and Isfahan, where eyvans dominate both the courtyard and the main facades (Hillenbrand, 1986).

A courtyard is an outdoor space which is entirely surrounded by buildings or walls. A courtyard building typically contains an open space that is surrounded by buildings, rooms or walls. Although there is a wide range of variations in dimensions and shapes of courtyards, this spatial structure generally provides a secluded and private space, and often acts as a source of light, fresh air and heat. In different cultures, it can be used for rest, play with children, worship (meditation), women’s activities and exercise((Taleghani et al., 2012).

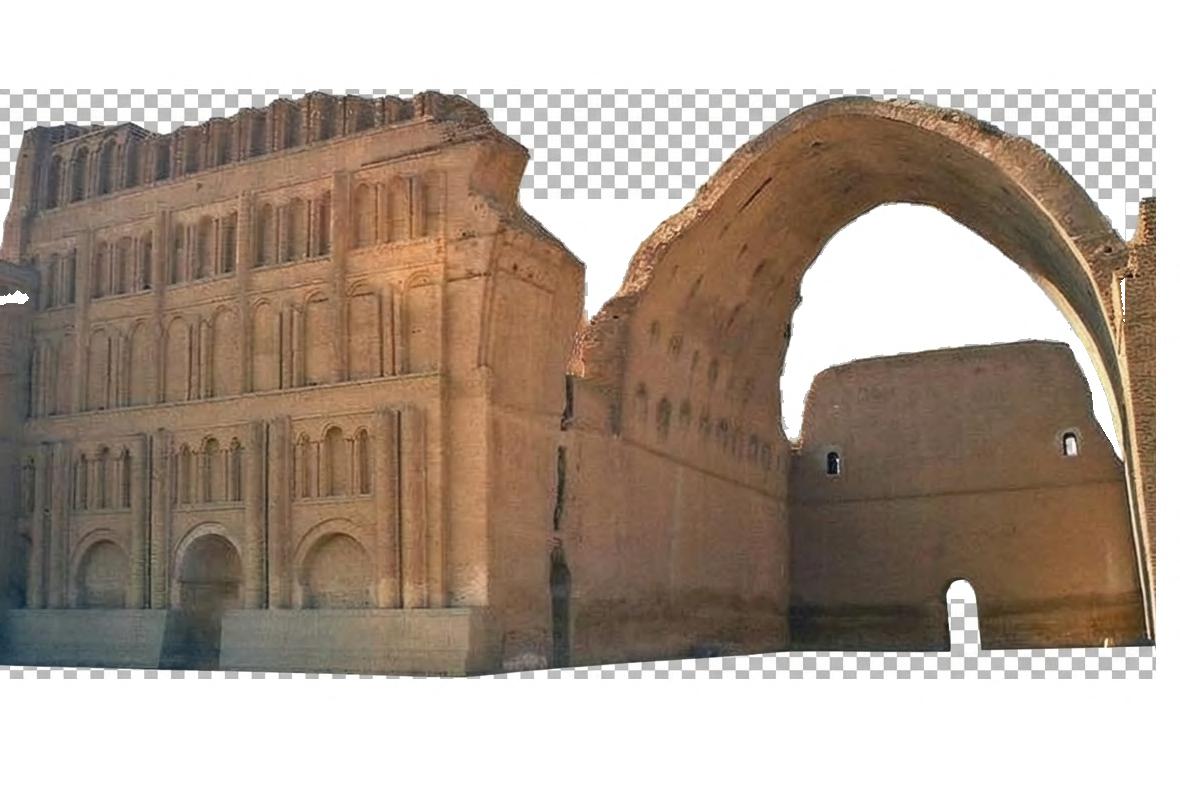

Taq Kasra, or Ayvān-e Kesrā, is the monumental vaulted hall of the Sasanian royal palace at Ctesiphon, located on the east bank of the Tigris River near present-day Baghdad (Huff, 1986). Built in the 6th century CE during the reign of Khosrow I, it is one of the most iconic examples of pre-Islamic Iranian architecture (Huff, 1986). The structure was heavily damaged after the Arab conquest of Ctesiphon in 637 CE and suffered further collapse in the late 19th and early 20th centuries due to neglect and flooding, with additional deterioration noted in recent years (Islamic Republic News Agency, 2021).

This section zooms out to trace the architectural eras of Iran, offering a timeline from the Sasanian period onward to show how shifts in power, religion, and identity have influenced the built environment.

A monumental Sasanian vaulted hall at Ctesiphon, built in the 6th century CE under Khosrow I. It is famous for its massive brick arch, the largest of the ancient world. Parts collapsed after the Arab conquest (7th century) and later neglect.

A Sasanian-era Zoroastrian fire temple near Qom, dating to around the 3rd–7th centuries CE. Built with stone and mudbrick, it preserves the traditional chahār-ṭāq plan used for sacred fire rituals.

A large Sasanian fortress in Khorramabad, originally built in the 3rd–4th century CE and later expanded in Islamic periods. Positioned on a hill above the city, it controlled regional trade and military routes.

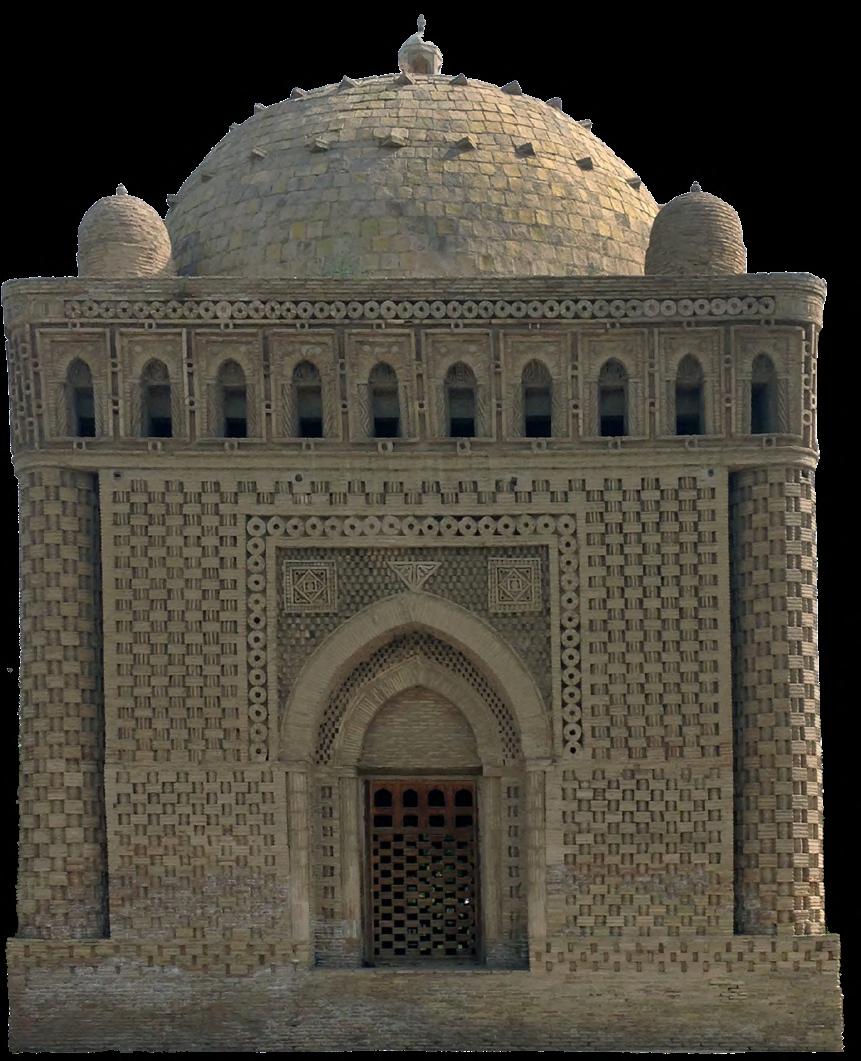

Samanid Mausoleum

A 9th–10th-century brick tomb in Bukhara, considered one of the earliest masterpieces of Islamic architecture. Its cube-domed form and intricate brickwork influenced many later mausoleums.

Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Isfahan

Built in the early 17th century by Shah Abbas I. This vast Safavid square unites the Shah Mosque, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, Ali Qapu Palace, and the bazaar, forming one of the world’s greatest urban ensembles.

Great Mosque of Isfahan

Founded in the 8th century and transformed during the Seljuk era (11th–12th centuries). It introduced the fouriwan courtyard plan and became a key model for Islamic mosque architecture.

Shahyād Tower

Completed in 1971 for the 2,500-year celebration of Iranian monarchy, designed by Hossein Amanat. Built of white stone, it blends Sasanian arches and Islamic geometry and serves as a symbolic gateway to Tehran.

Sassanian Era - 224 to 651 CE

The Sasanian Empire ruled Iran from 224 to 651 CE and created one of the most influential architectural traditions in the ancient world. Sasanian architecture is best known for its use of mortar masonry, mudbrick, rubble stone, and brick, which allowed the builders to create large vaulted spaces, domes, and monumental halls that were technically impossible in earlier periods. Gypsum mortar, which sets very quickly, made it possible to build large vaults without wooden scaffolding, contributing to the distinctive elliptical barrel vaults seen throughout Sasanian buildings (Djamali et al., 2017)..

One of the most important architectural achievements of the Sasanians was the development of the dome on squinches, a technique that allowed a round dome to sit securely on a square room. This structural innovation became a defining feature of Iranian and later Islamic architecture. The typical Sasanian domed hall had plain lower walls, a middle zone of squinches and niches for transition, and the dome above. When domed halls were combined with barrel-vaulted bays, they produced the chahar-taq form, a cruciform plan that appears in fire temples, palaces, and major monuments of the period (Huff & O’Kane, 1990).

The Sasanians also perfected the eyvan, a large vaulted hall open on one side, which became one of the most recognizable elements of Iranian architecture. Famous examples include Taq Kasra at Ctesiphon.

In palaces, the eyvan served as the main ceremonial reception space. Cities and large architectural complexes often centered their layout around an eyvan, a domed hall, or a combination of both.

Columns played a smaller role during this era because massive walls and pillars were better suited to supporting wide vaults. Decorative elements were created mainly with plaster and stucco, some of which were painted or carved in relief. These decorations show a blend of Iranian tradition with influences from Rome and Byzantium.

Functionally, Sasanian architecture included fire temples, palaces, fortified cities, bridges, and hydraulic systems. Fire temples often used the chahar-taq plan or domed chambers with surrounding corridors. Palaces, such as those at Firuzabad and Bishapur, used strict axial layouts, monumental eyvans, domed audience halls, and large courtyards. Fortifications, city walls, and bridges show advanced engineering, often built with the help of Roman craftsmen captured in war (Huff, 1986).

In summary, the Sasanian era defined the foundations of Iranian architectural identity: the mastery of vaults and domes, the eyvan, the chahar-taq, strong axial planning, and sophisticated engineering. These innovations shaped the architecture of the Middle East for centuries and became the structural and symbolic basis of early Islamic architecture (Huff, 1986)..

16th -19th century 1925 -1979

Islamic Era - 7th century

Islamic architecture in Iran begins after the 7th century CE, but its early history is difficult to trace because few buildings survive from the first centuries. What is certain is that Islamic architecture grew directly out of the earlier Sasanian tradition (Grabar, 1986).. Elements such as the ayvan, the dome on squinches, brick vaulting, and stucco decoration were inherited from the Sasanians and continued almost unchanged into the early Islamic period. Even older forms like the chahar-taq influenced the earliest mosques.

A clearer architectural identity appears from the 10th century onward under the Samanids and Ghaznavids. This was the era when baked brick became the main construction material and when sophisticated brick and stucco decoration developed rapidly. In the 11th to 13th centuries, during the Seljuq period, Iranian Islamic architecture reached a major turning point. The four-ayvan courtyard plan became widespread, domes expanded in scale and complexity, muqarnas emerged, and tall brick minarets became common throughout Iran.

Throughout all these centuries, a small group of architectural elements remained constant: the dome, the ayvan, the courtyard, the tower, and the wall. These forms, inherited from preIslamic Iran and transformed through Islamic use, created a continuous architectural language that shaped Iranian buildings until the rise of the Safavids (Hillenbrand, 1986).

16th -19th century 1925 -1979

From the 16th to the 19th century, Iranian architecture experienced one of its most visible transformations, beginning with the Safavid dynasty. Although few major buildings were produced before 1580, architecture reached maturity under Shah Abbas I, when classical Iranian forms were rebuilt on an unprecedented urban scale. In this period, the city of Isfahan became the center of architectural innovation: long axial boulevards, monumental squares, bridges, caravanserais, gardens, and palaces formed a unified urban composition unmatched in earlier centuries (Hillenbrand, 1986).

Safavid architecture relied on traditional Iranian elements inherited from earlier periods the dome, the eyvan, the courtyard, and the walls but enlarged them and reshaped their spatial relationships. The Masjed-e Shah and Masjed-e Sheikh Lotfollah represent the peak of the domed square and four-eyvan mosque. Tilework reached full coverage on domes, facades, and interiors using large painted tiles that emphasized color and light over structural clarity. Architecture became a careful orchestration of scale, proportion, and movement. Buildings such as Ali Qapu and Chehel Sotun used open talar halls, wooden ceilings, deep porches, and reflective surfaces to create fluid transitions between interior and exterior. Civic structures bridges, bazaars, and caravanserais demonstrated refined vaulting, repetitive arcades, and functional yet elegant plans.

16th -19th

In the Zand period, architecture continued Safavid vocabulary but combined it with Sasanian motifs and limited Indian and European influences. Under the Qajars, many Safavid forms were revived and imitated, especially four-eyvan mosques, long bazaars, and garden palaces. However, new visual styles appeared: bright narrative tiles, figural painting, Europeanstyle windows and façades, and extensive mirrorwork. Qajar palaces such as Golestan integrated traditional talar halls and domed kiosks with imported decorative features. While structurally conservative, Qajar architecture expanded surface ornament and theatrical display to new levels.

Across Safavid to Qajar centuries, the essential identity of Iranian architecture remained stable. Traditional spatial units domes, eyvans, courtyards, arcades, walls, and gardens continued to shape buildings, while the major changes occurred in scale, decoration, color, and the integration of buildings into larger urban compositions (Hillenbrand, 1986).

After World War II, Iranian architecture entered a new phase in which traditional forms confronted Western modernism. In the early period (1941–1963), construction was limited, but architects trained in the French Beaux-Arts tradition introduced a new monumental language. Their works combined modern materials with symbolic references to Iran’s past, while traditional courtyard houses slowly shifted into apartment blocks and suburban villas influenced by European models.

Between 1963 and 1973, rising oil income and new development plans transformed architecture. A generation of foreign-educated Iranian architects returned and brought modern design methods, while research into Iranian heritage revived interest in brick, arches, domes, and traditional spatial logic. Major public projects appeared, including universities, sports complexes, and cultural institutions. Two key works defined the era: the Tehran Sports Center, which reinterpreted ancient Iranian forms at a monumental scale, and the Shahyad Tower, which combined Sasanian and Islamic geometries into a modern national monument (Ardalan, 1986).

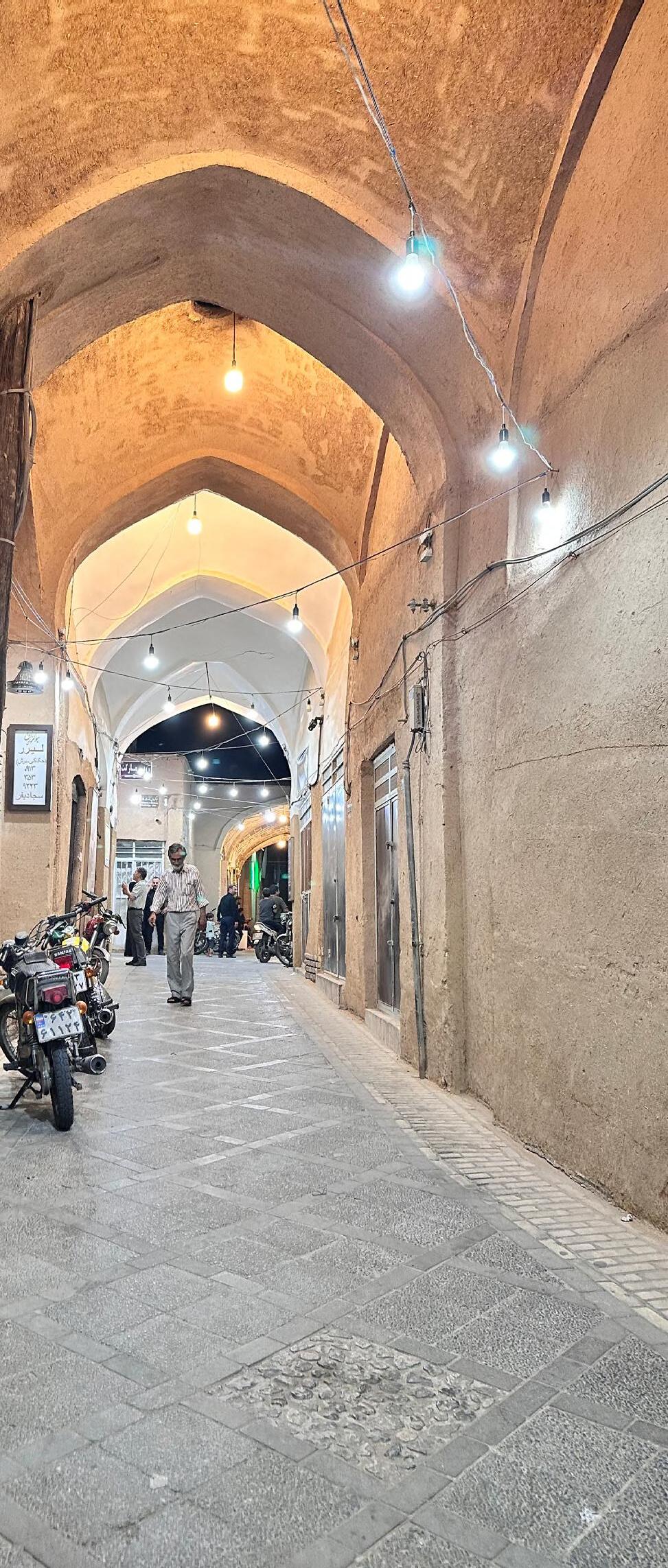

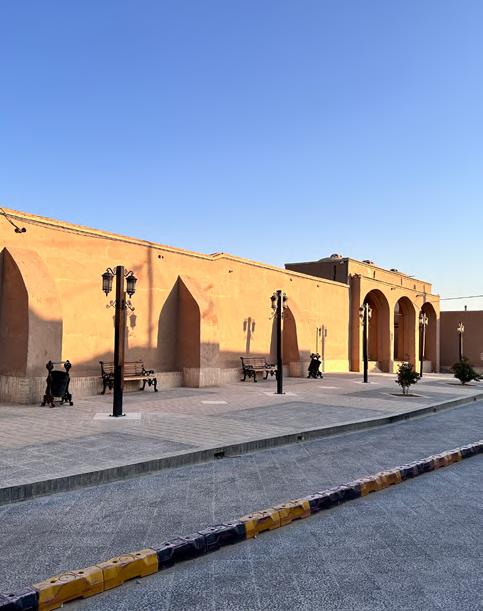

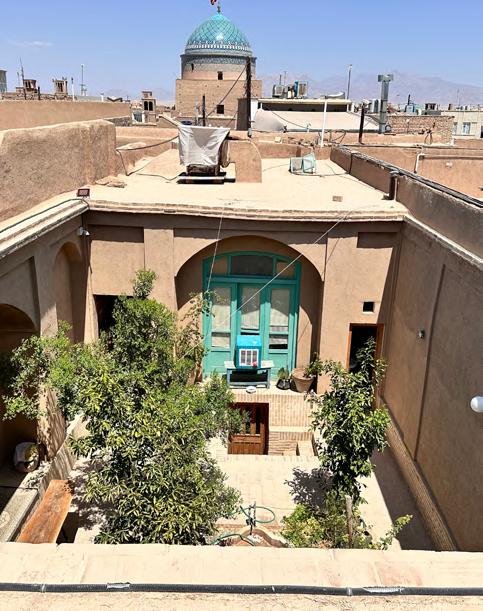

In this section, the daily life of residents in the city of Yazd will be examined. The findings presented here are based on my field visit to Yazd and are derived from direct conversations with local inhabitants, personal observations, and experiential engagement with their everyday practices and habits.

How is the daily life in Yazd?

Yazd is a historic city located in the heart of Iran, between the northern Dasht-e Kavir and the southern Dasht-e Lut deserts. Surrounded by arid plains and mountains, Yazd has long been known for its distinctive desert climate: scorching summers, cold winters, dry air, and minimal rainfall. This climate has not only shaped the architecture of the city, but also deeply influenced the daily rhythms and lifestyle of its people. In the next section, I will introduce the architectural elements that define the city from badgirs (windcatchers) and eyvans to chahartaqs and qantas. But before we dive into those, I want to focus on the daily life in Yazd not from books or academic sources, but from walking through the city myself and speaking with the people who live there.

The midday rest!

One of the first things I noticed was how the heat controls the pace of life. From early morning until midday, people are at work often indoors or in shaded areas. But around noon, everything slows down. Streets become empty, shops close, and a quiet stillness takes over the city. Life pulls back behind thick walls and cool courtyards, where families rest sometimes sleeping, sometimes simply pausing to recover from the heat.

This midday pause isn’t officially scheduled, but it’s deeply embedded in daily life. Around 12:00, many shops, bazaars, souvenir stores, coffeehouses, restaurants, and even some museums close their doors. While some reopen around 17:00, others remain closed until 19:00, avoiding the peak heat hours.

From a tourist’s perspective, this is very noticeable. For three days, I searched for a simple coffeehouse to sit, have a coffee, and do some work but found none open during the day, until I stumbled upon one by chance. For visitors who aren’t held back by the heat and still want to explore the city, this midday closure creates a real absence of accessible spaces.

And yet, these very visitors, the ones walking, discovering, and spending are a key part of Yazd’s local economy. This quiet pause in the city’s public life may serve local comfort, but it also highlights a gap: a missed opportunity for small-scale cultural and economic exchange, especially in tourism.

Rooftops as living spaces!

Then, as the sun sets and a gentle breeze rises, Yazd wakes up. This is when life returns to the streets. People stroll along the alleyways, sit on benches in the public squares, or climb up to their rooftops. These rooftops are not just architectural features, they are living spaces. In the evenings, they are cooler than the streets or courtyards. Families gather there, sometimes to sleep, often just to enjoy the night sky and the wind.

To my surprise, when the temperature dropped and shops reopened in the evening, people preferred the rooftops to the bazaars. And the reason is simple: it’s the end of the day. Locals want to enjoy their time, unwind, and socialize. Tourists, on the other hand, are eager to eat, explore, and experience Yazd’s nightlife. As a result, the energy shifts toward areas that offer leisure and ambiance not shopping.

This creates a clear disadvantage for shops located outside the old city, especially those not catering to tourists or those selling very specific goods. In contrast, the old city itself becomes the experience: the narrow alleys, the light, the architecture, the galleries and rooftop cafés all encourage people to walk, explore, and spend. In these streets, even a souvenir shop feels like a natural part of the journey.

The importance of courtyards! Just like the rooftops, courtyards play an important role. Traditionally designed to be protected from the sun and wind, they once served as private oases cooler in summer and warmer in winter thanks to their central placement and the surrounding thick-walled rooms. Today, however, with rising temperatures and reduced greenery or water, many courtyards no longer provide the same thermal comfort.

Still, they remain meaningful spaces: places where daily life unfolds, where people gather for breakfast, conversations, and quiet moments. While the courtyard itself may not always be shaded, the eyvan a semi-open, roofed platform attached to one side offers shelter and relief. Most courtyards still feature a howz, a shallow water pool, which once helped cool the air and create a pleasant atmosphere.

In Yazd’s traditional homes, the use of space shifts with the sun: courtyards are used in the morning and around midday for rest, while rooftops come alive in the evening when the air is cooler.

What is Nowruz?

Nowruz comes from two Persian words: “now” meaning new, and “ruz” meaning light or brightness. It marks the first day of spring, celebrated for thousands of years as a moment of renewal, joy, and connection with nature.

Nowruz is not passed down through facts it lives through stories, beliefs, and shared memory. In Yazd and many regions, it holds a deep connection to nature. In Iran’s dry climate, knowing the start of spring was essential for farming and survival, and over time, that practical need became a cultural tradition (Boyce, 1989; Daryaee, 2008).

One symbol that remains is the number seven, now seen in the Haft-Seen table prepared for the New Year which I will return to later. But this number has older roots. In the Zoroastrian worldview, seven divine forces the Amesha Spentas each governed part of the natural world and shaped how people understood life and balance (Boyce, 1979; Boyce, 1989).

1. Ahura Mazda-humankind

2. Vohuman (Bahman)-animals

3. Asha Vahishta (Ardavahisht)-fire

4. Khshathra Vairya (Shahrivar)-metals

5. Spenta Armaiti (Spendarmad)-earth

6. Haurvatat (Khordad)-water

7. Ameretat (Amordad)-plants

Over time, the spiritual concept of seven evolved into the famous Haft-Sīn table. The items may have changed, but the connection to life and nature remained.

Pre-Islamic Era - Zoroastrian Origins (c. 1200 BCE - 651 CE)

Nowruz began as a Zoroastrian festival celebrating light, balance, and cosmic order. It aligned with the spring equinox and honored the renewal of the earth and the spirit. It was one of the most important rituals in the Zoroastrian calendar.

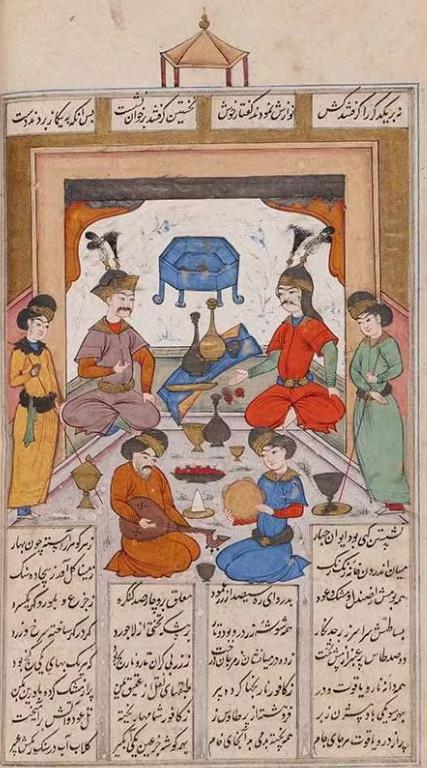

Sasanian Era (224-651 CE)

In the Sasanian Empire, Nowruz became a formal state event. Kings celebrated it publicly to show power and prosperity. Stories from this era suggest that the tradition of planting seven seeds began here: Before Nowruz, seven kinds of seeds were sown. The one that grew best was recommended for widespread farming that year linking the sacred number 7 with both nature and survival.

Post-Islamic Era (651 CE – today) After the Islamic conquest, Nowruz survived as a cultural tradition, independent of religion. The Haft-Sīn table, now central to the celebration, holds seven symbolic items, each representing renewal, health, patience, love, growth, and rebirth. Though its religious frame faded, Nowruz remained a powerful ritual marking time, honoring nature, and bringing people together across generations.

From

01: King and His Attendants Shahnameh: After Jamshid mons, and darkness, he sky (carried by divs or demons), place, he shines with divine amazed by the brightness the new day — celebrating

01: 7-S table of Nowruz

03: Persepolis was the ceremonial Achaemenid Empire, founded around 518 BCE. Located Along the staircases and cially at the Apadana (audience reliefs show satraps and Achaemenid Empire bringing scenes represent the Nowruz and representatives gathered reaffirm their loyalty.

04: A 7-S table of Zoroastrians.

bottom:

Attendants Feasting Folio from the Jamshid conquers disease, deraises a throne high into the demons), and from this high divine light. The people are brightness and call that day Nowruz, celebrating light, victory, and rebirth.

ceremonial capital of the founded by Darius the Great Located near present-day Shiraz. walls of Persepolis, espe(audience hall), detailed stone delegates from across the bringing gifts to the king. These Nowruz ceremony, when rulers gathered to honor the king and Zoroastrians.

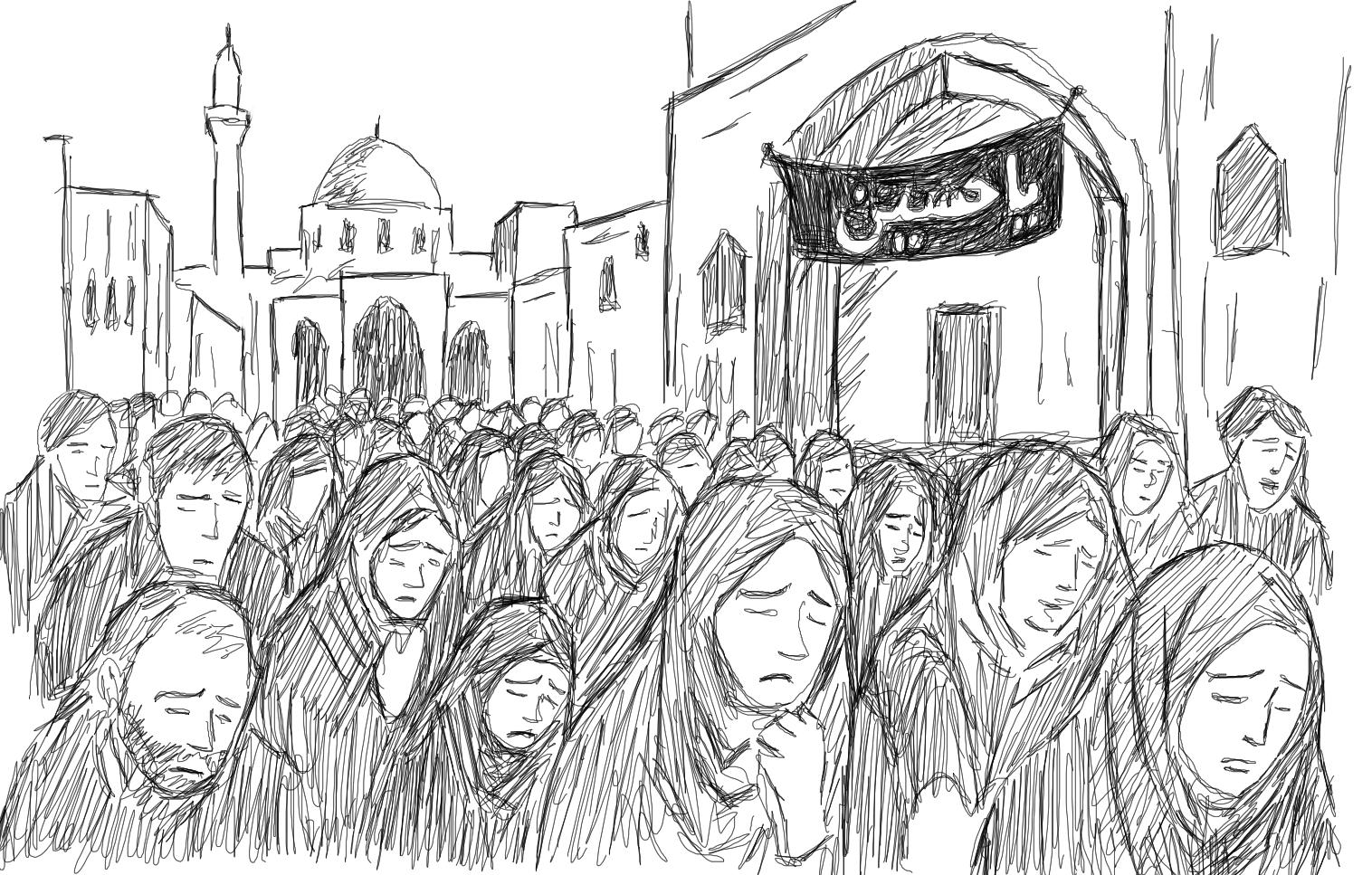

What is Muharram?

Muharram is the first month of the Islamic calendar, marking the martyrdom of Imam Husayn in 680 CE. Public mourning rituals entered Iran during the Safavid era (1501–1736), when Shi‘ism became the state religion. These rituals especially on the 10th day, Ashura blend devotion, performance, and collective memory.

Muharram in Yazd

In Yazd, preparations for Muharram begin before the month arrives. Black cloths cover the city’s streets, mosques, and husayniyyas (mourning halls). Historic husayniyyas such as Fahadan, Alqamah, Bagh-e Gandam, and Amir Chakhmaq become centers of gathering and collective remembrance.

Several unique customs define Yazd’s Muharram rituals:

Chavush Khani A group or individual walks through the streets reciting poetry to announce the arrival of Muharram.

Rozeh Khani

Throughout Yazd, mourners gather to listen to a maddah (eulogist) recite the tragedy of Karbala. This is followed by chest-beating (sineh zani), and continues from early morning to midnight for 60 days from Muharram through Safar.

Parsehzani

Mourners, led by a Sayyid and a flagbearer,

pass through neighborhoods while residents offer food and contributions in support of the ceremonies.

Nakhl Gardani

A massive wooden structure, the Nakhl, symbolizing the coffin of Imam Husayn, is carried by mourners in a solemn funeral procession. The tradition of Nakhl has deep roots in Persian culture.

Nakhl” means palm tree in Persian. In ancient Iran, the palm tree was called the “tree of life” representing resistance, beauty, and blessing. Before Islam, the Nakhl was used to mourn mythic figures such as Siavash, the innocent prince killed in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. After the Safavid period, this symbol was incorporated into Shiʿi mourning. One story tells that Imam Husayn’s body, left unburied for three days, was later carried using palm branches thus the coffin-shaped Nakhl became a symbol of his martyrdom (Calmard, 2000)..

What is anar feast?

Anar is the Persian word for pomegranate. Every year at the beginning of November, the village of Saryazd comes to life for the Pomegranate Feast, a seasonal celebration held during the harvest. Although small and quiet for most of the year, Saryazd becomes a vibrant destination as people travel from many different parts of Iran to take part in this event. The feast is well-known far beyond the region, drawing attention to the village’s deep connection to the land and its traditions.

Visitors and locals gather to enjoy freshly picked pomegranates, local food, music, and handmade goods. It is a communal moment to honor the harvest, appreciate the farmers’ work, and share in the joy of the season. The pomegranate is more than a fruit here it represents life, fertility, and cultural memory, making the feast a symbol of connection between people, land, and tradition.

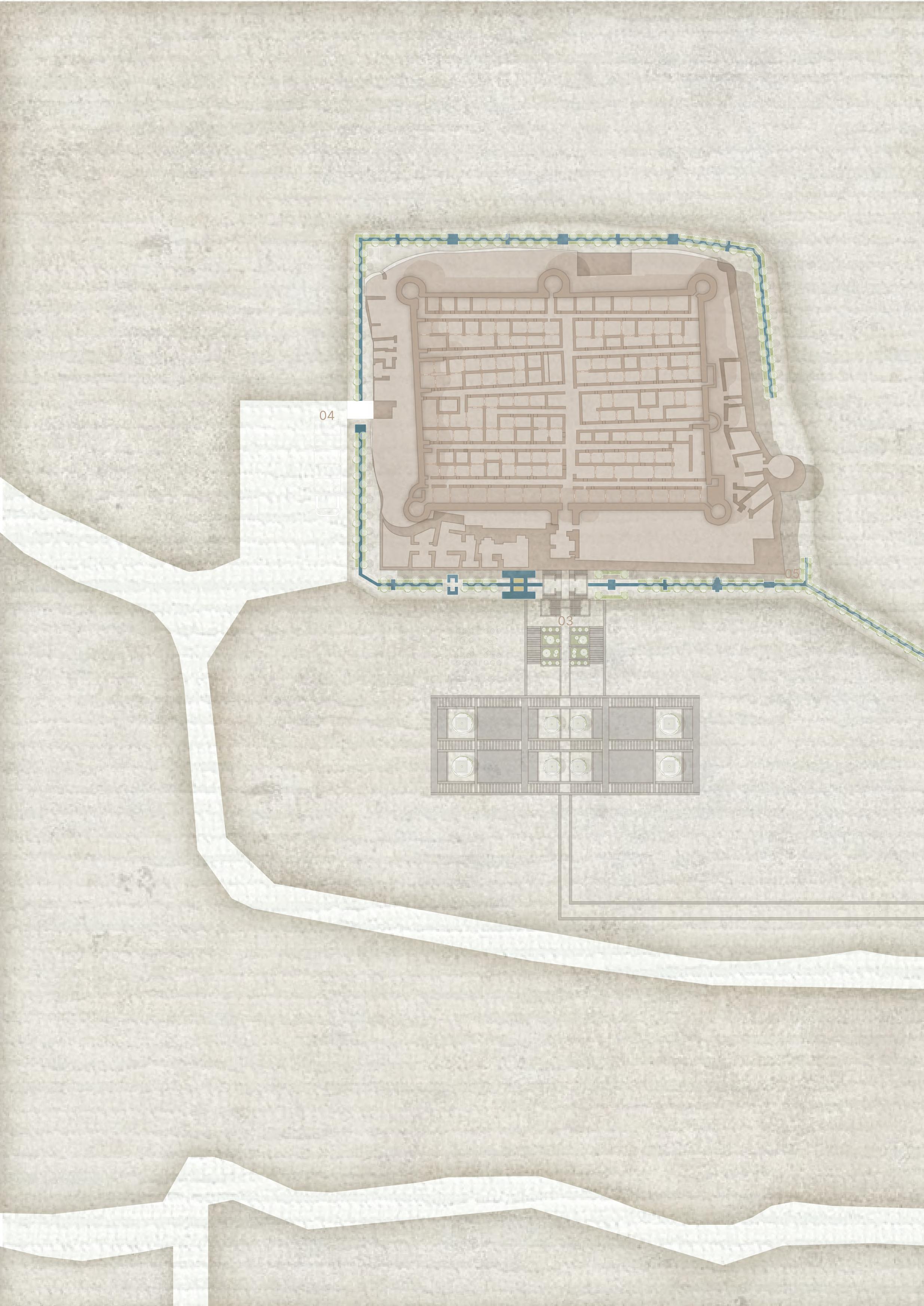

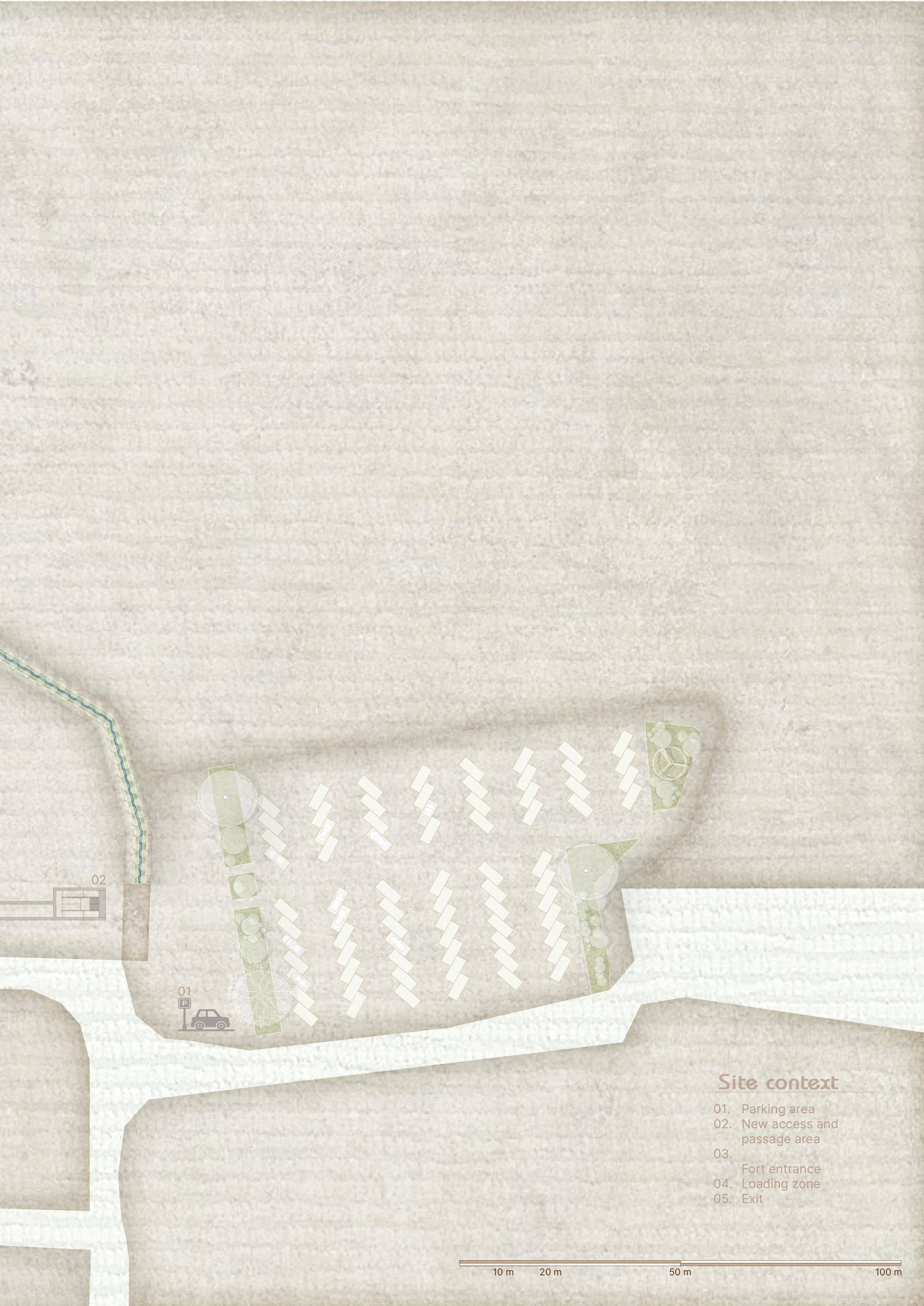

Chapter Two introduces the physical and architectural setting of Saryazd Fort. The first section describes the fort’s location, landscape, and historical context, showing how its placement within the Yazd region shaped its character and purpose. The second section presents the architectural analysis, examining the fort’s spatial organization, construction techniques, and key design elements that define its identity.

05. Saryazdfort in its landscape 06. Analysis

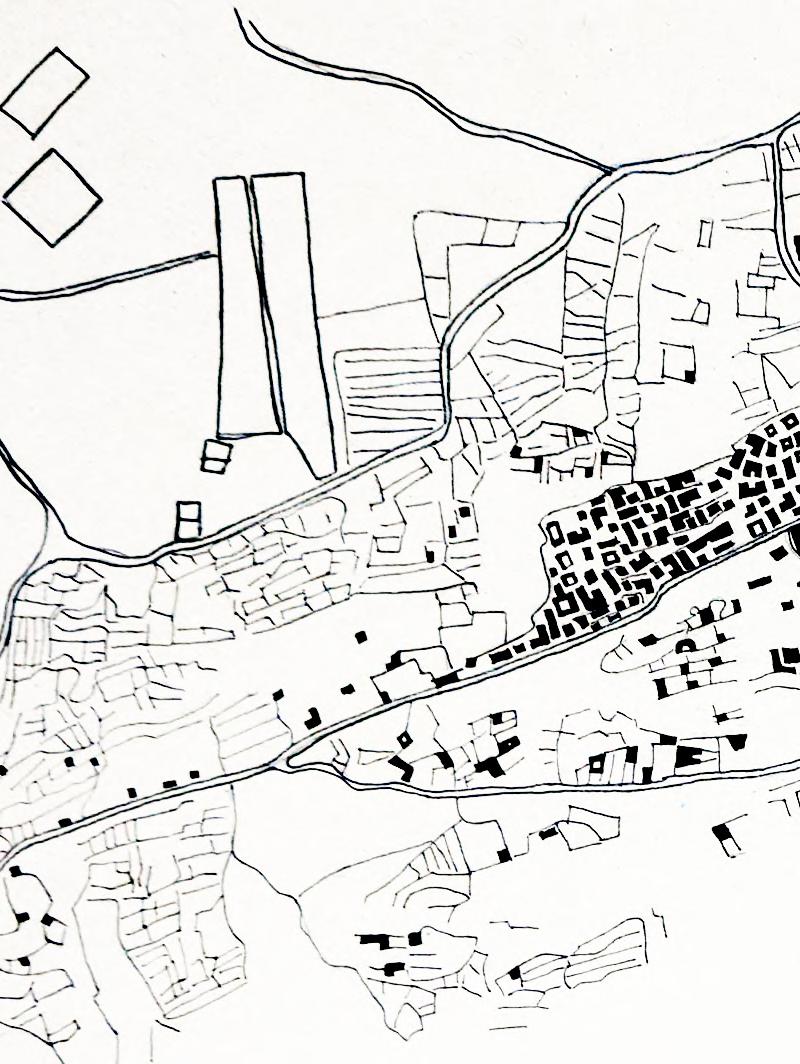

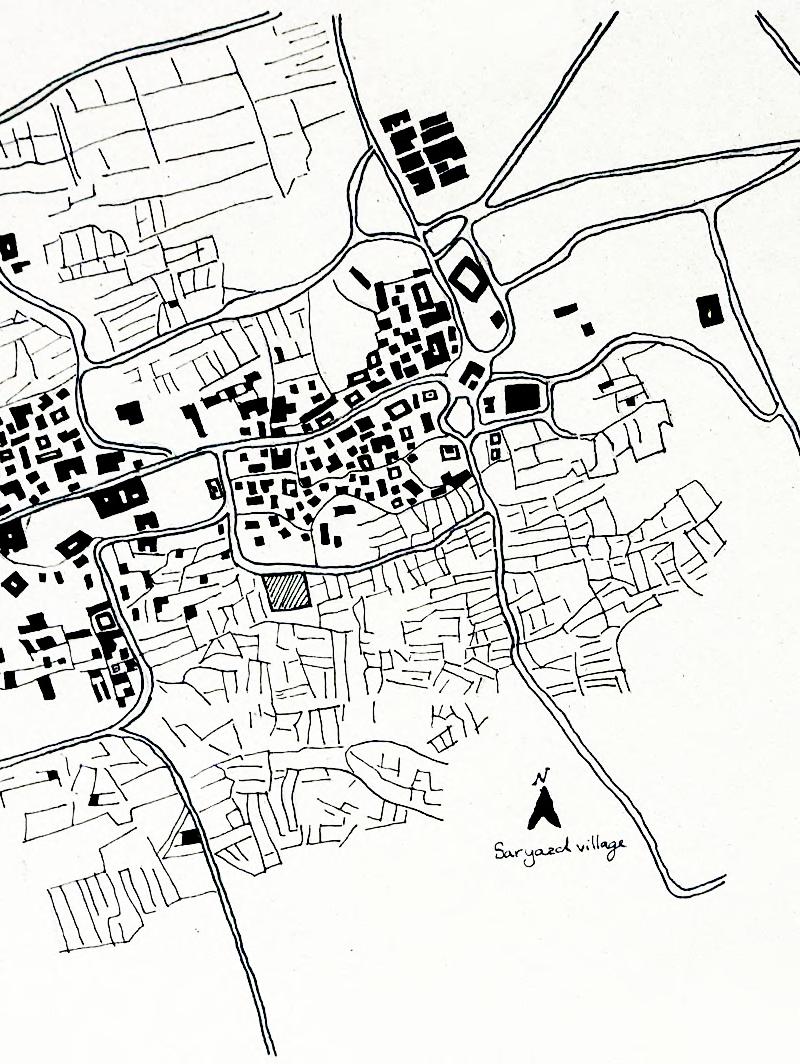

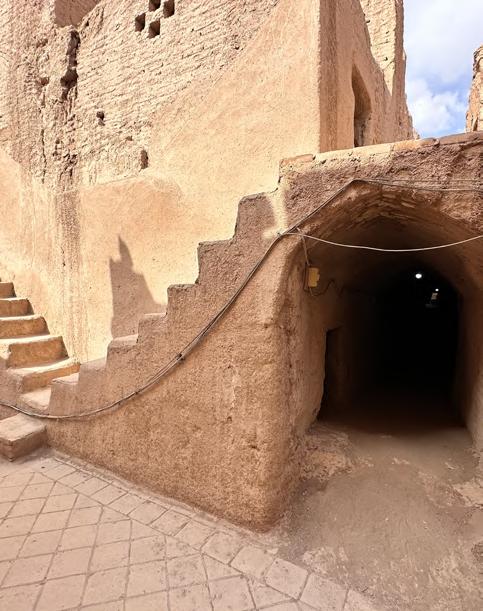

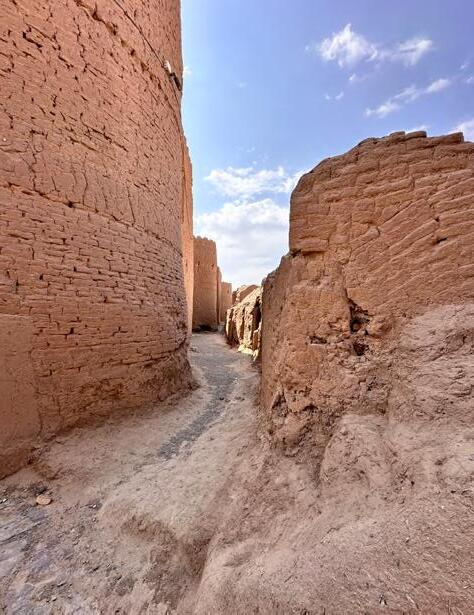

Before analyzing the architecture of Saryazd Fort, it is essential to understand where it is located. The fort sits in the village of Saryazd, in Mehriz region, within the Yazd province in the central heart of Iran; a region defined by its harsh desert climate, extreme temperature shifts, and scarce water resources. This environment shaped both the fort’s defensive character and the traditional architectural strategies used in the area.

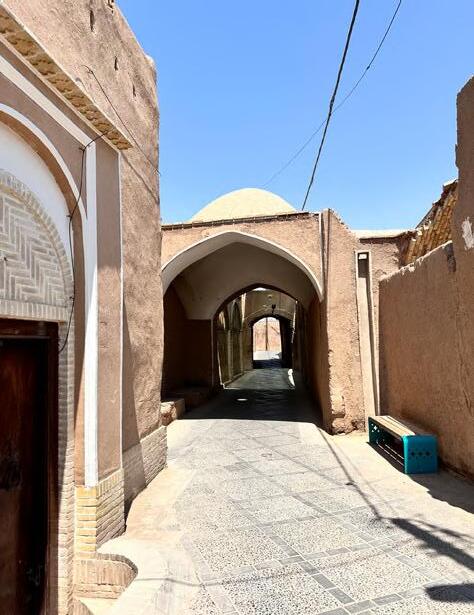

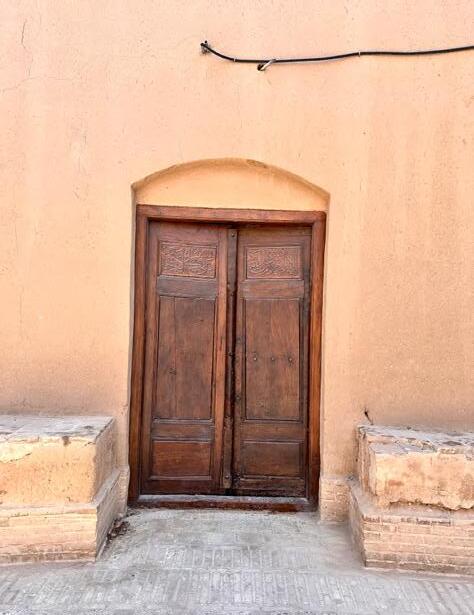

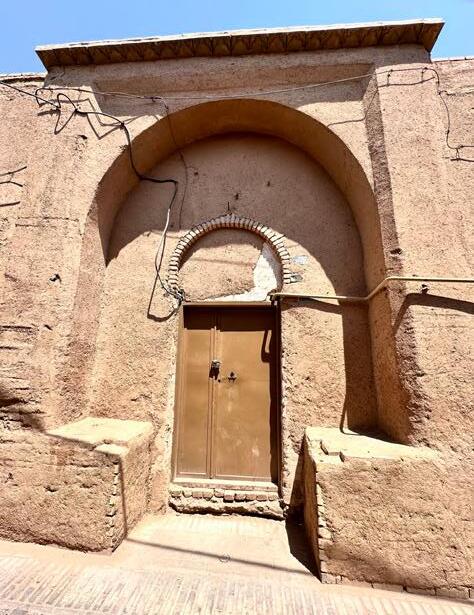

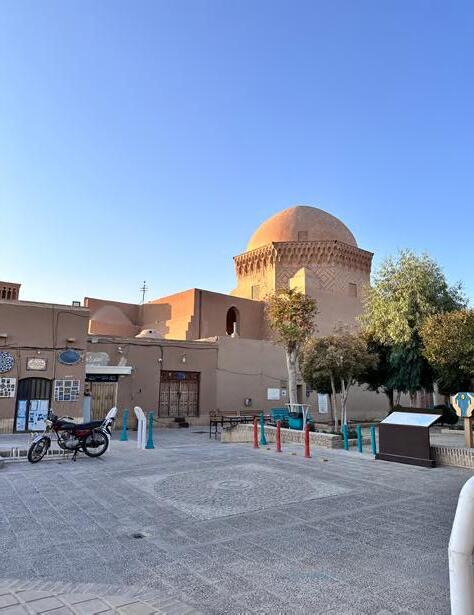

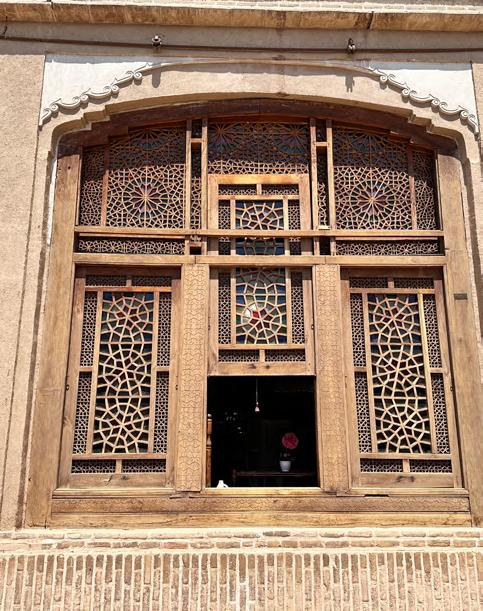

See next page for photographs taken in the city of Yazd.

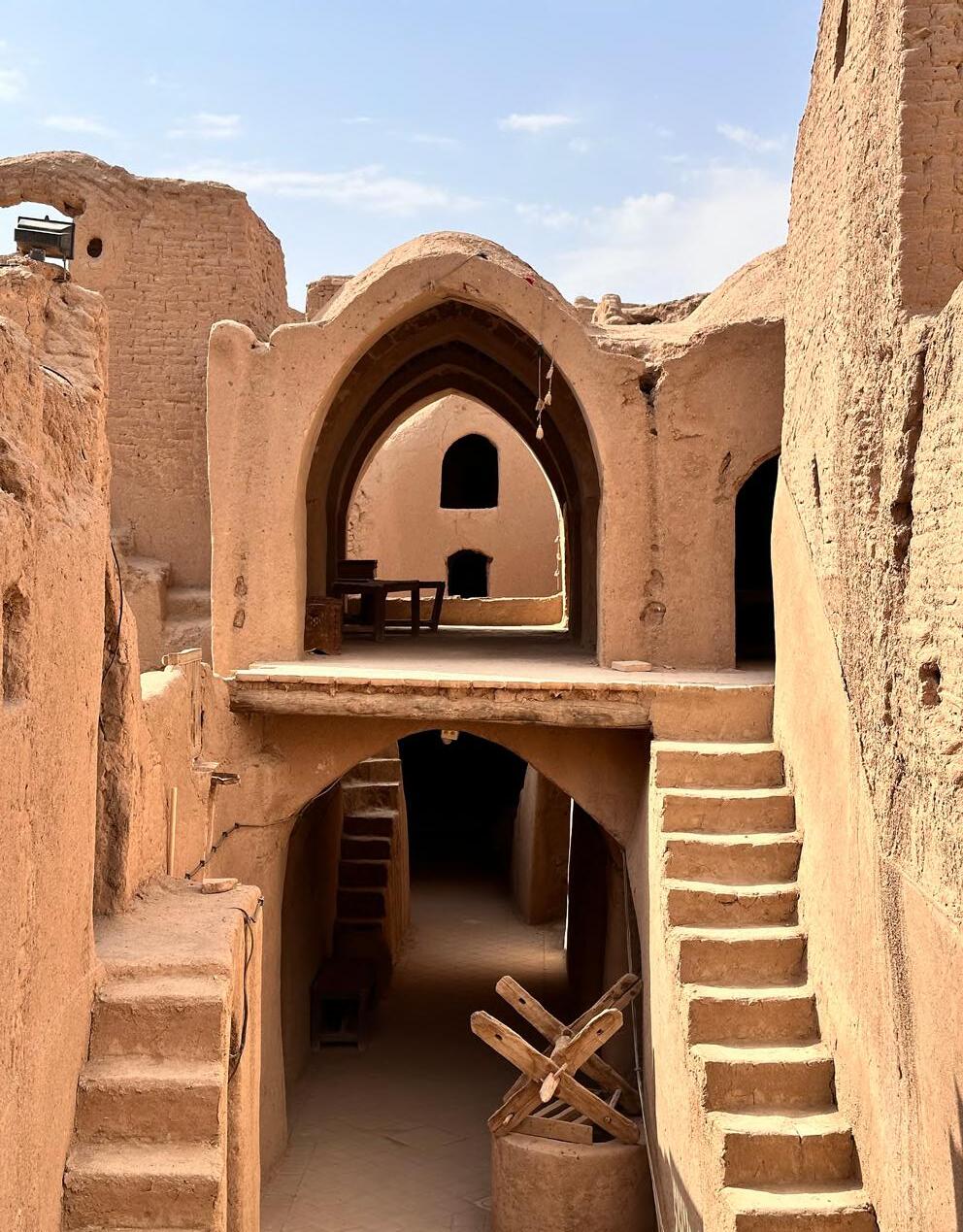

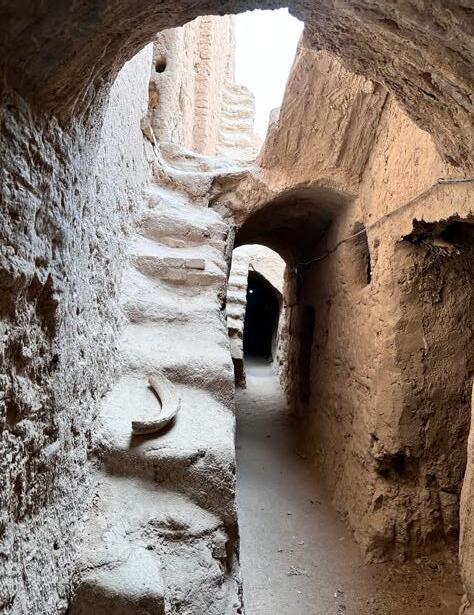

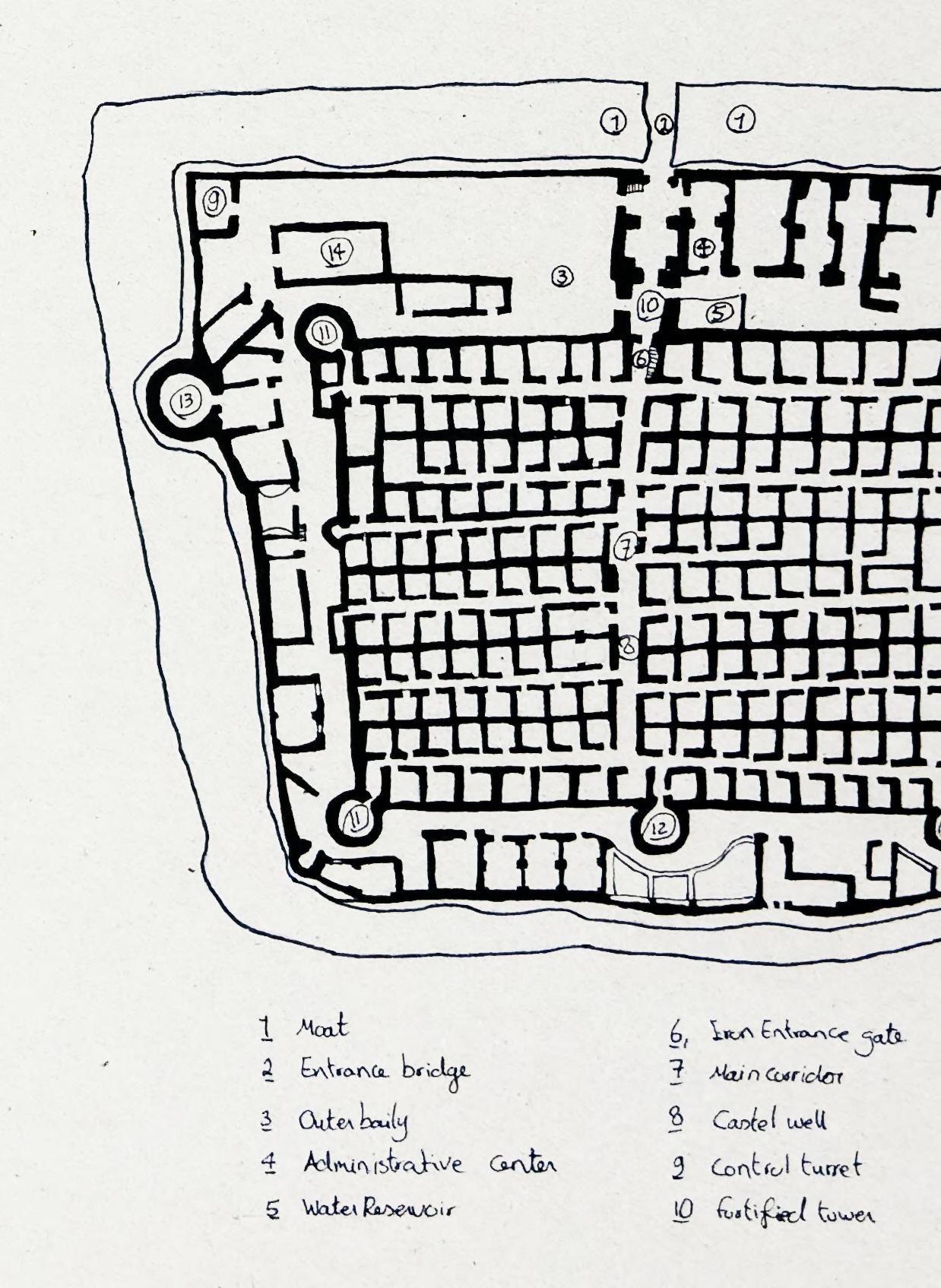

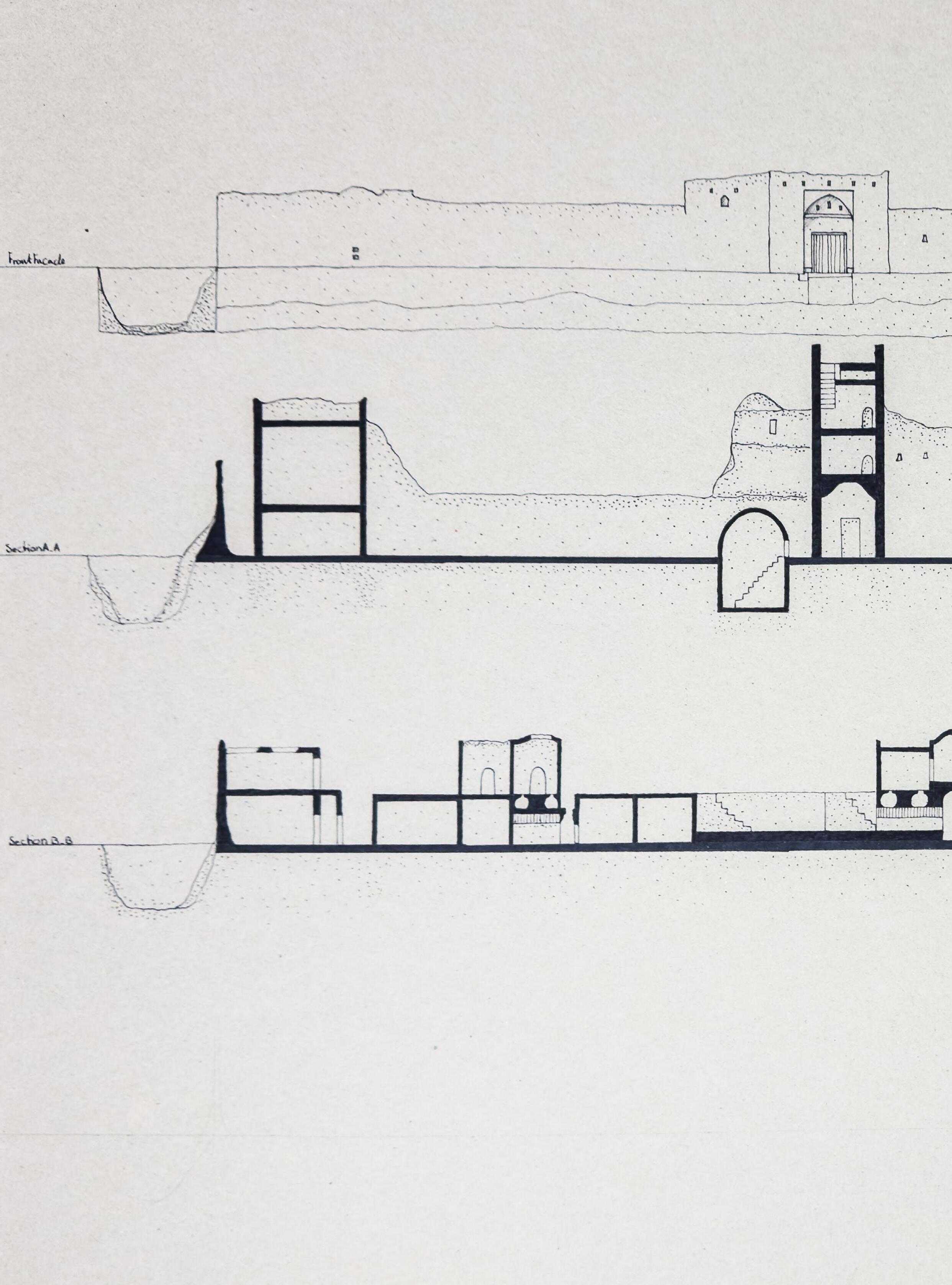

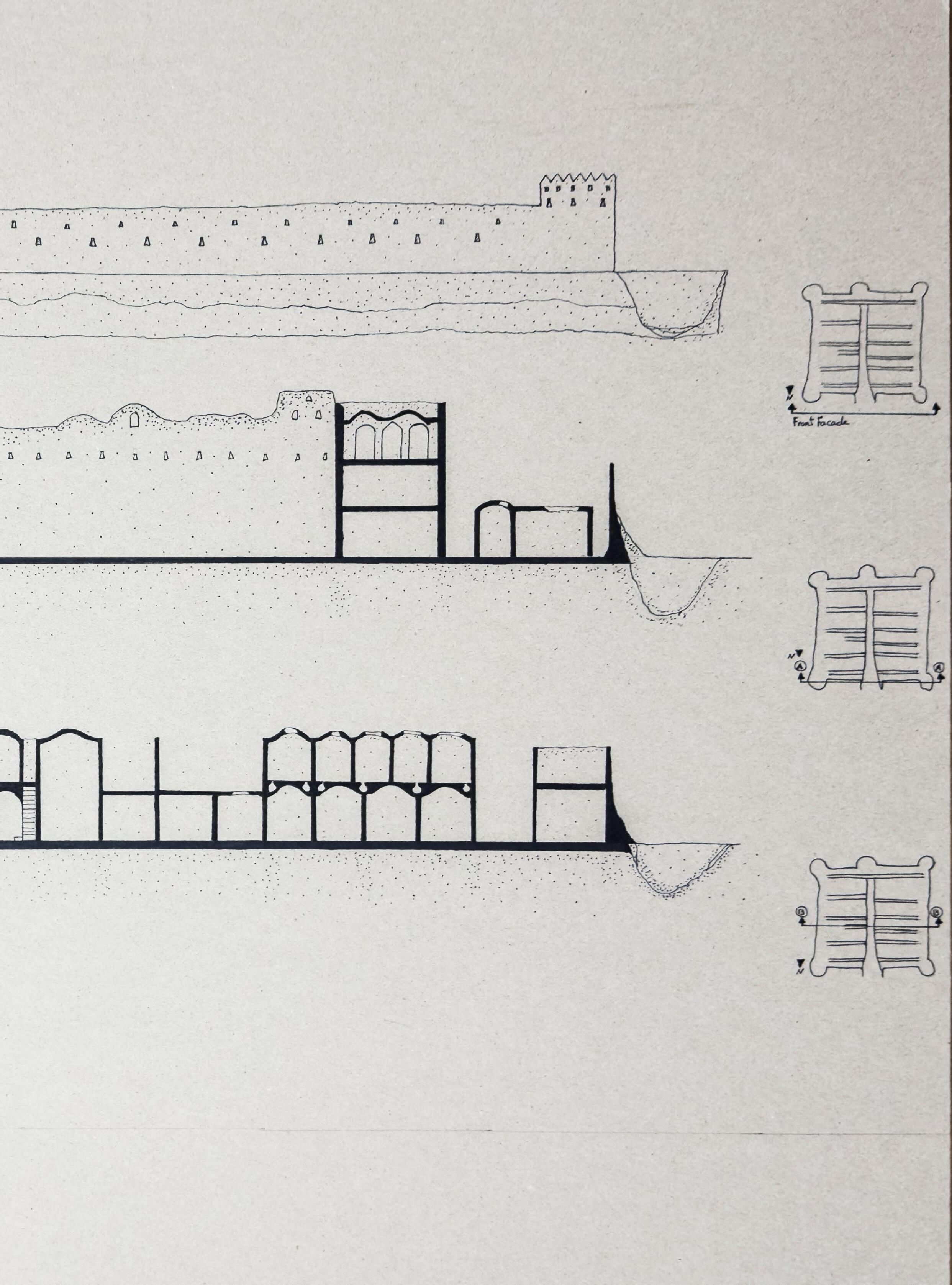

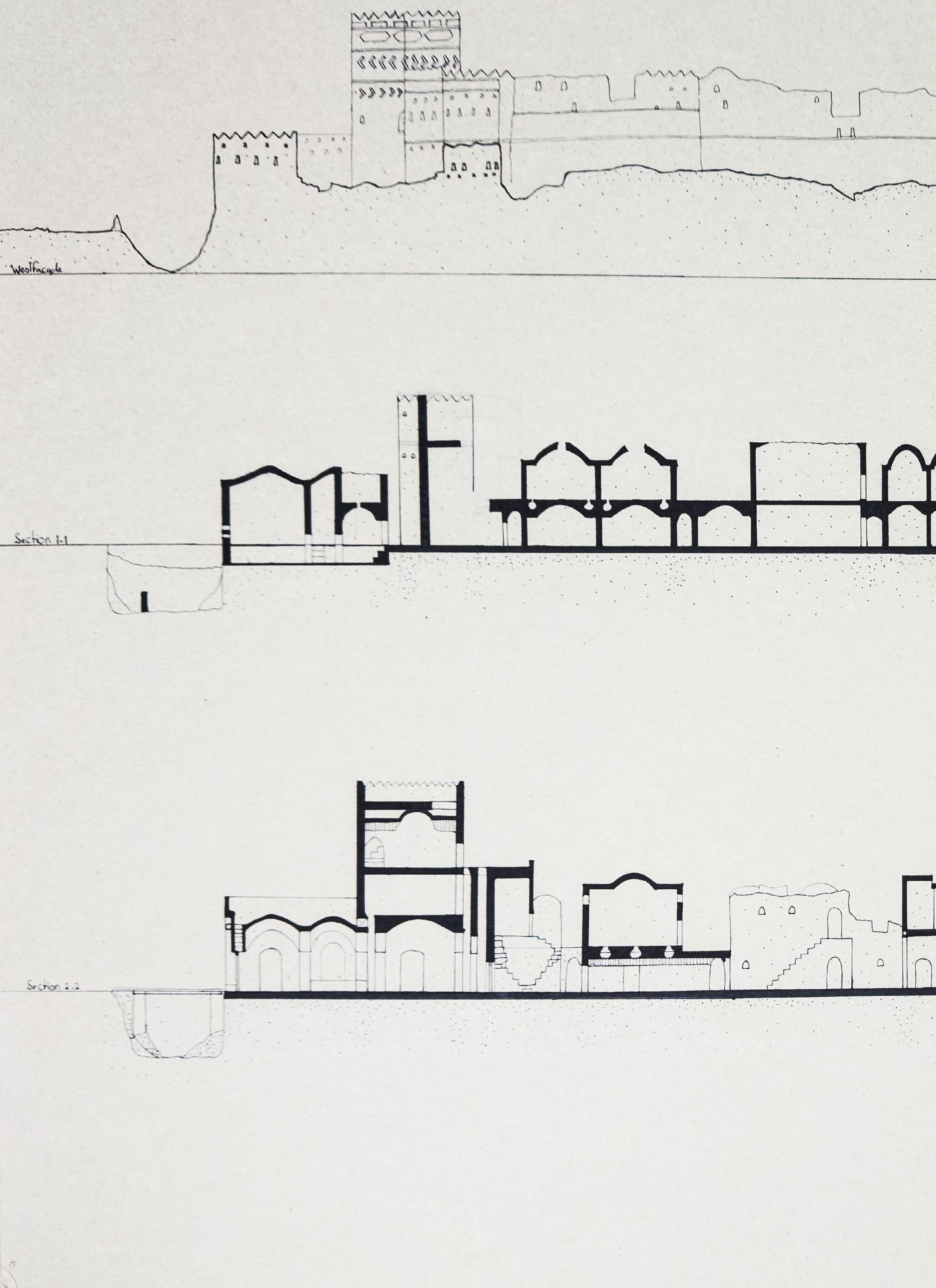

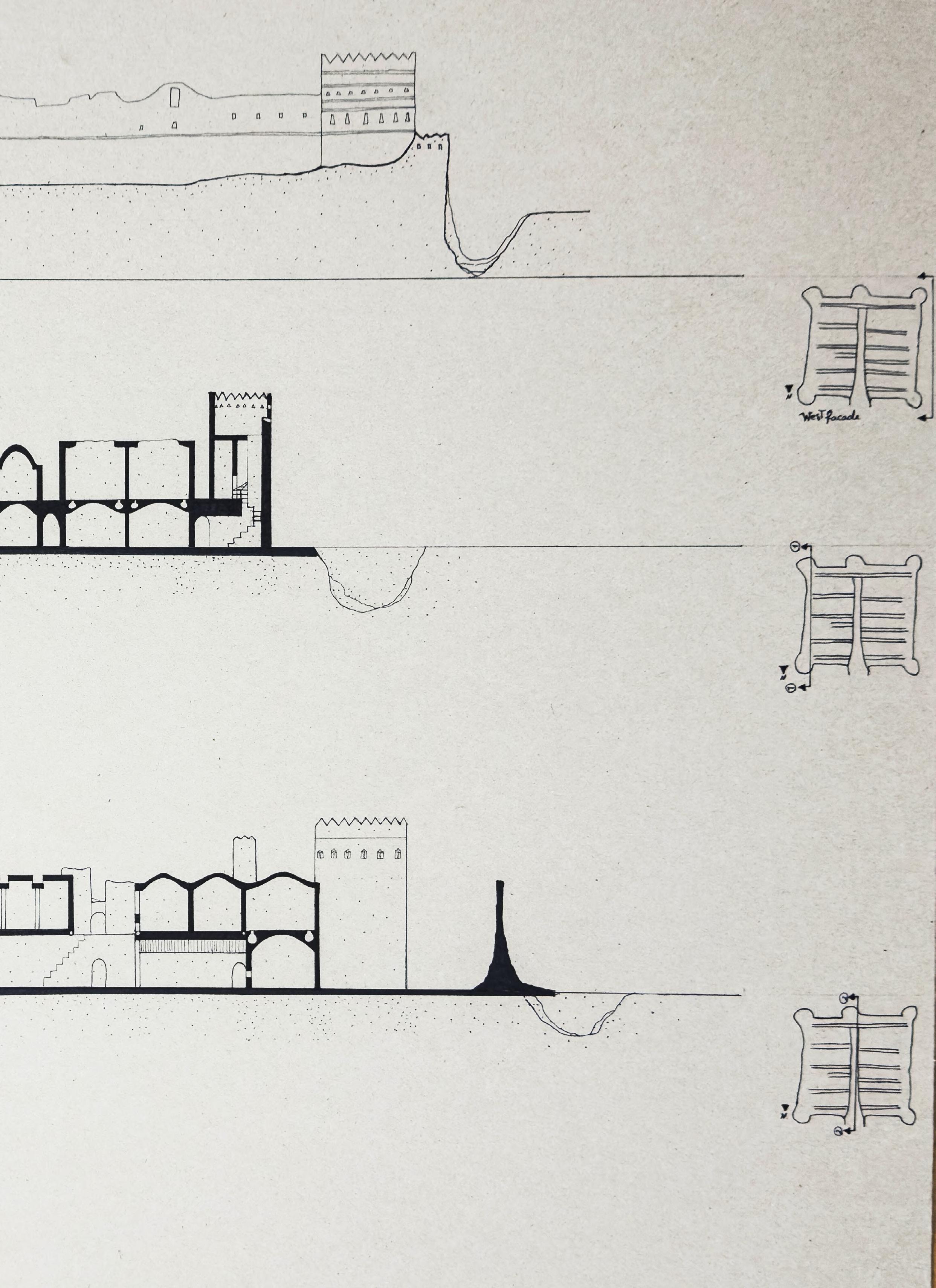

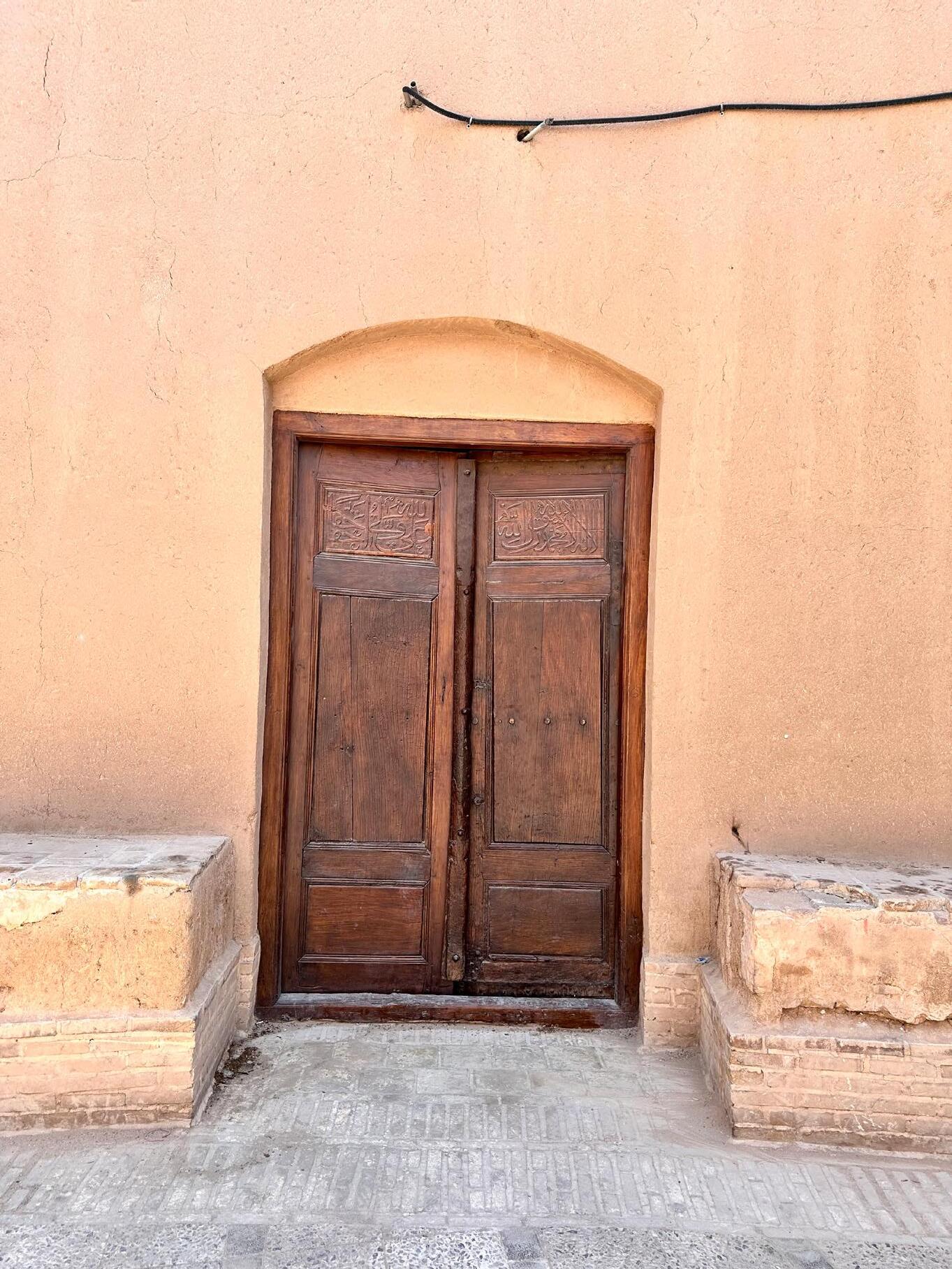

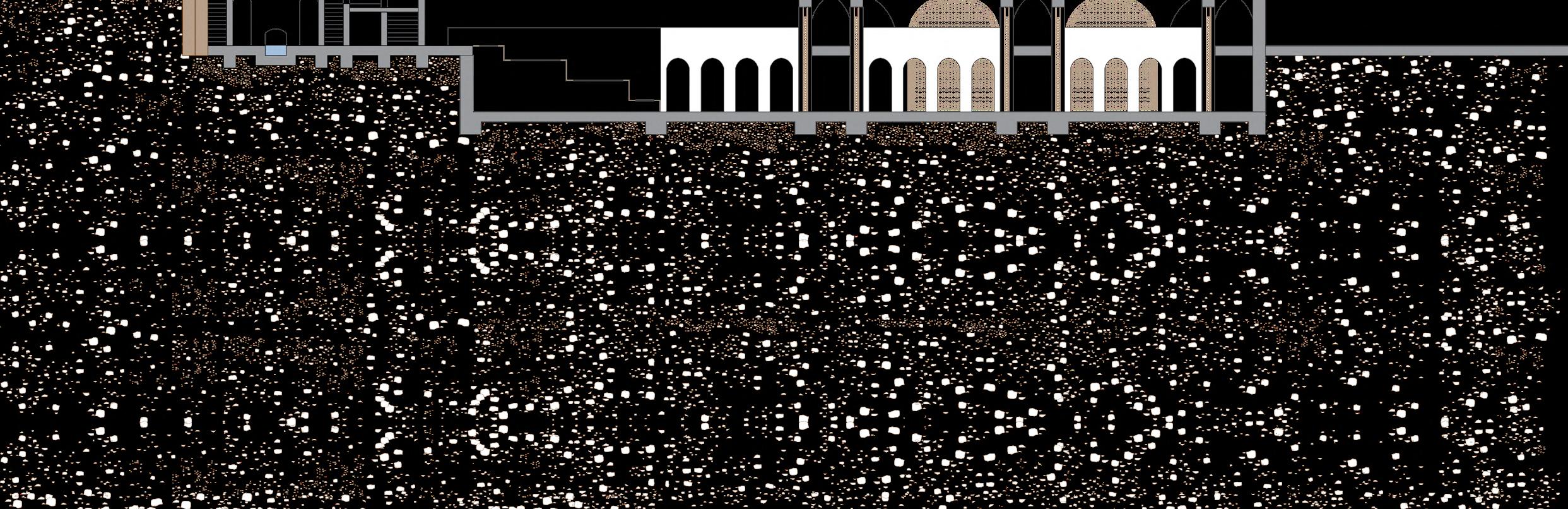

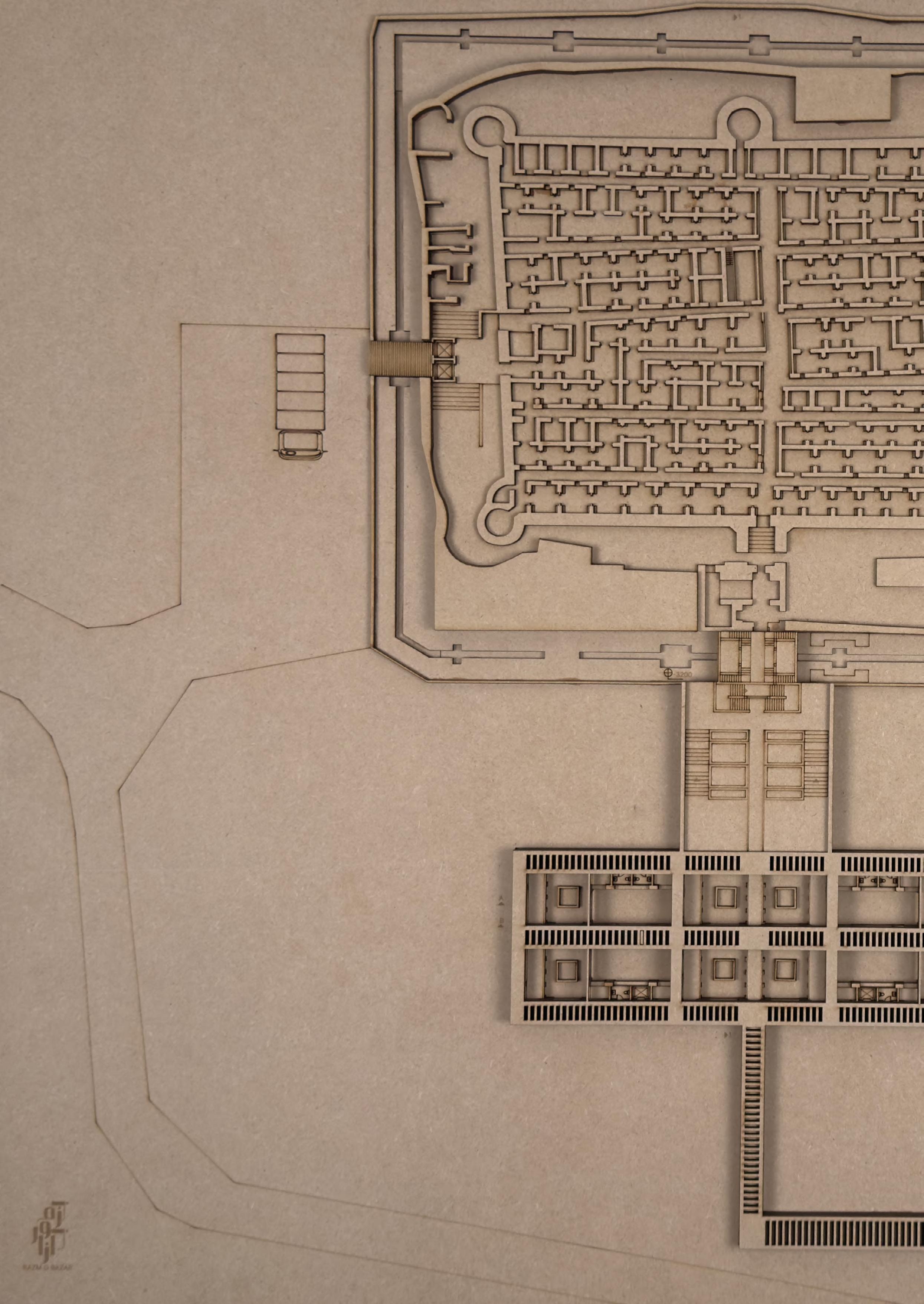

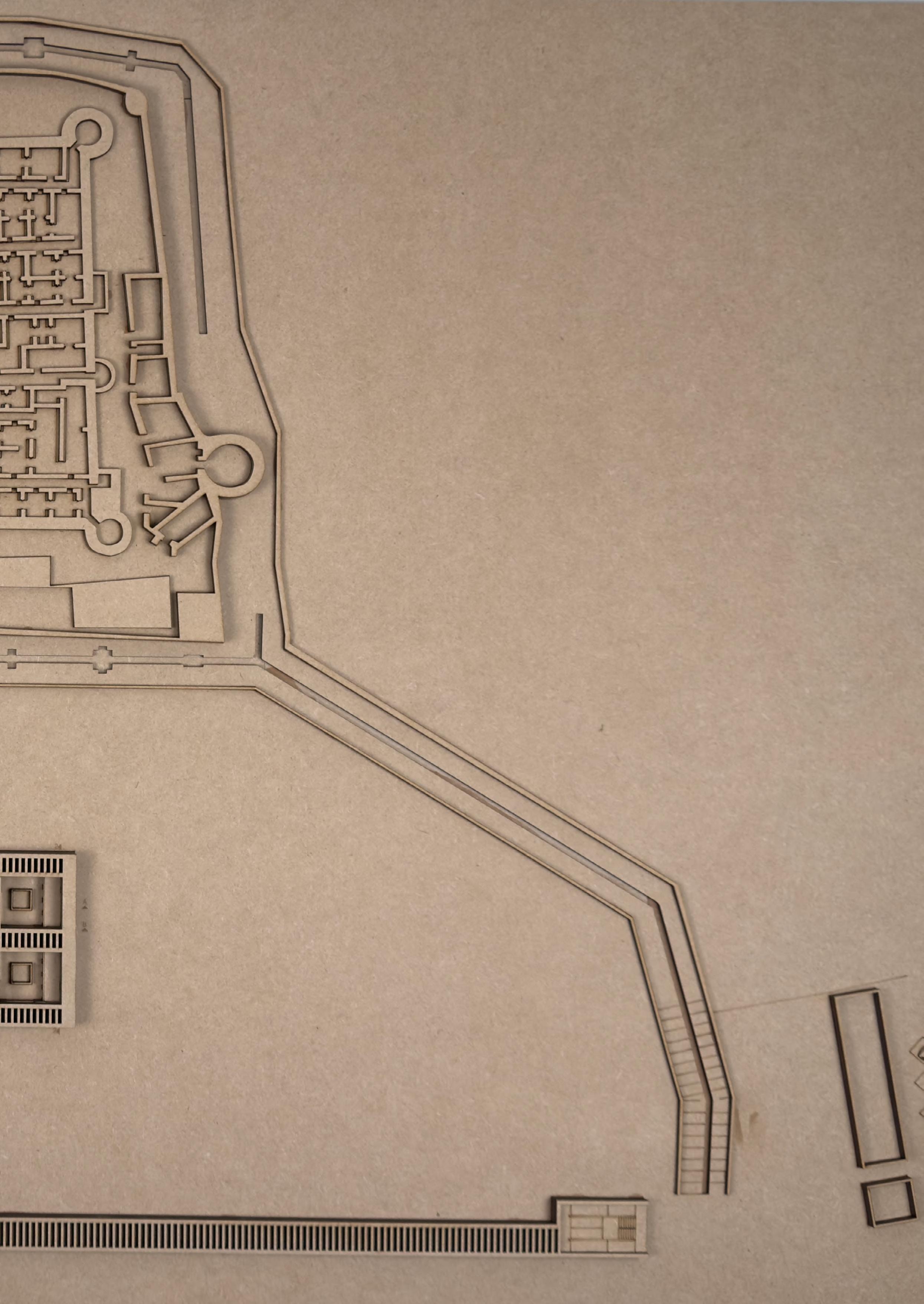

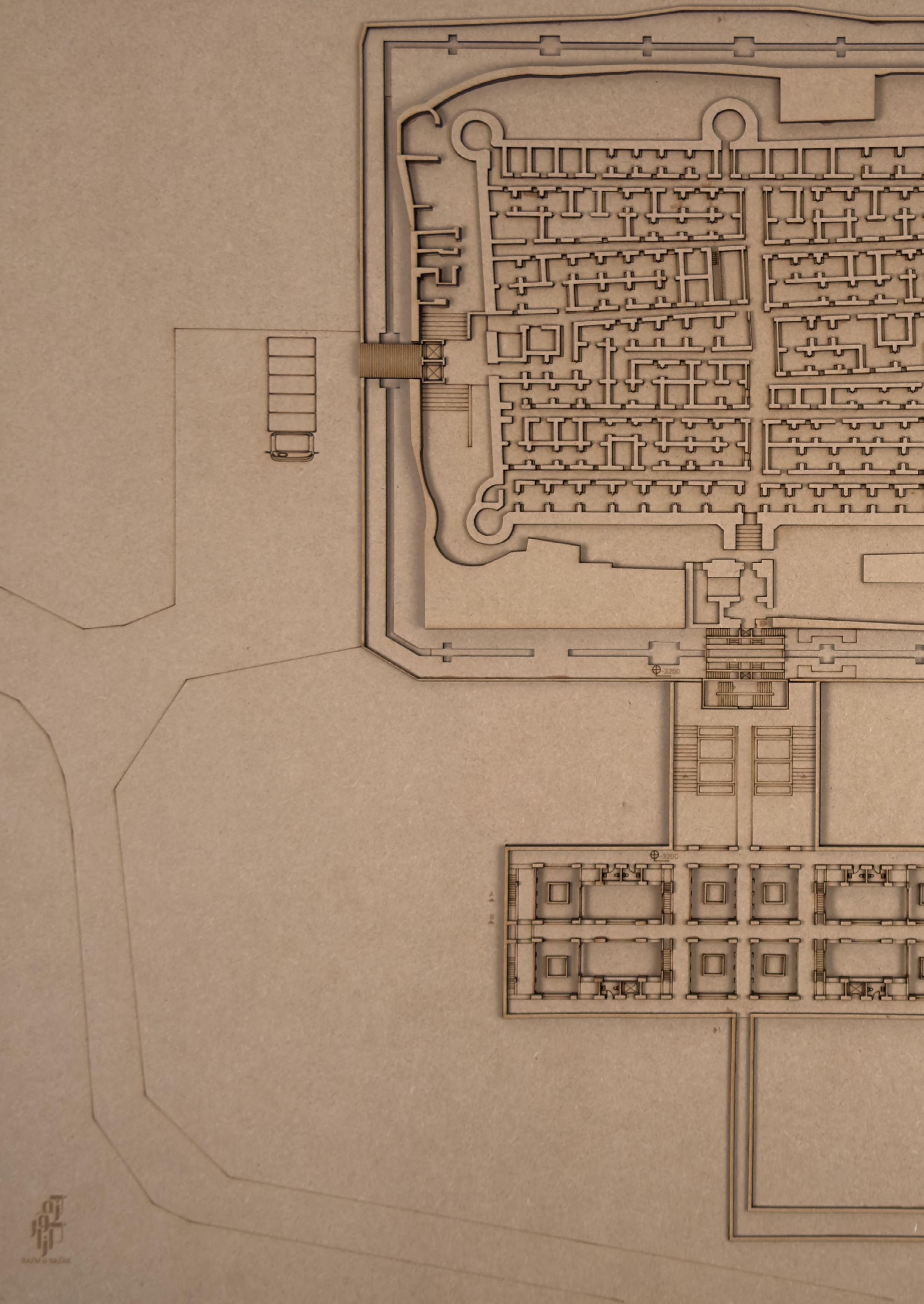

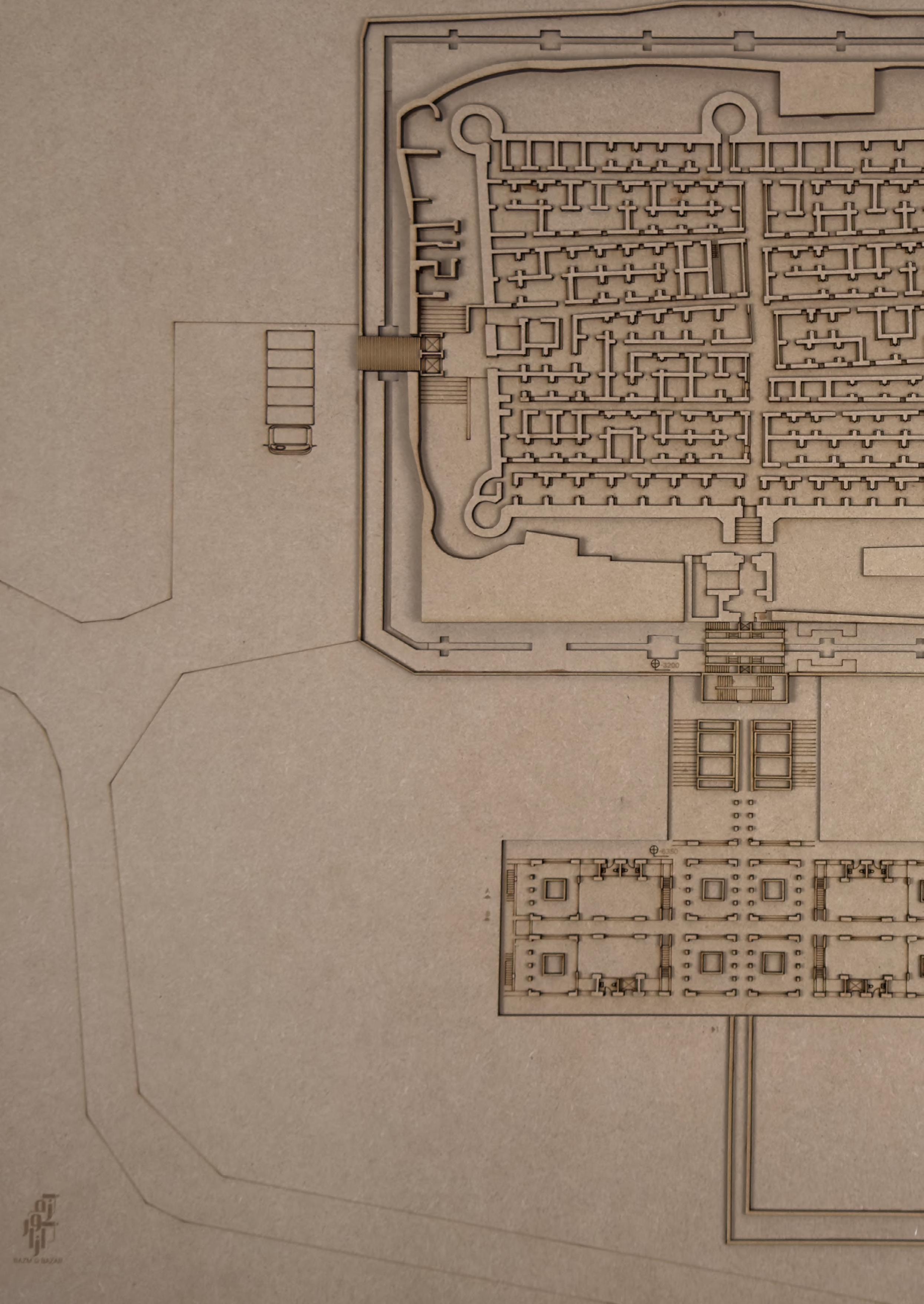

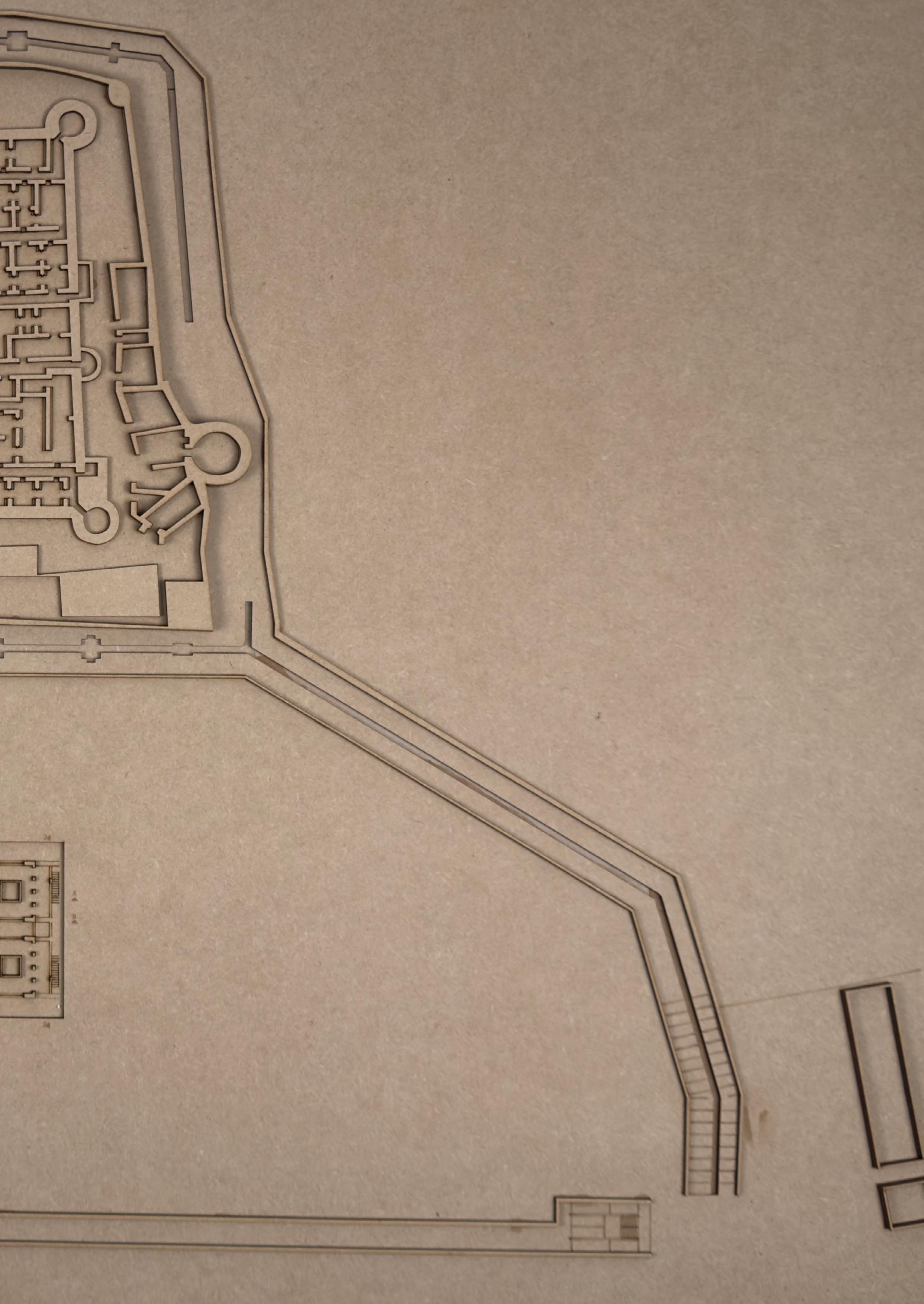

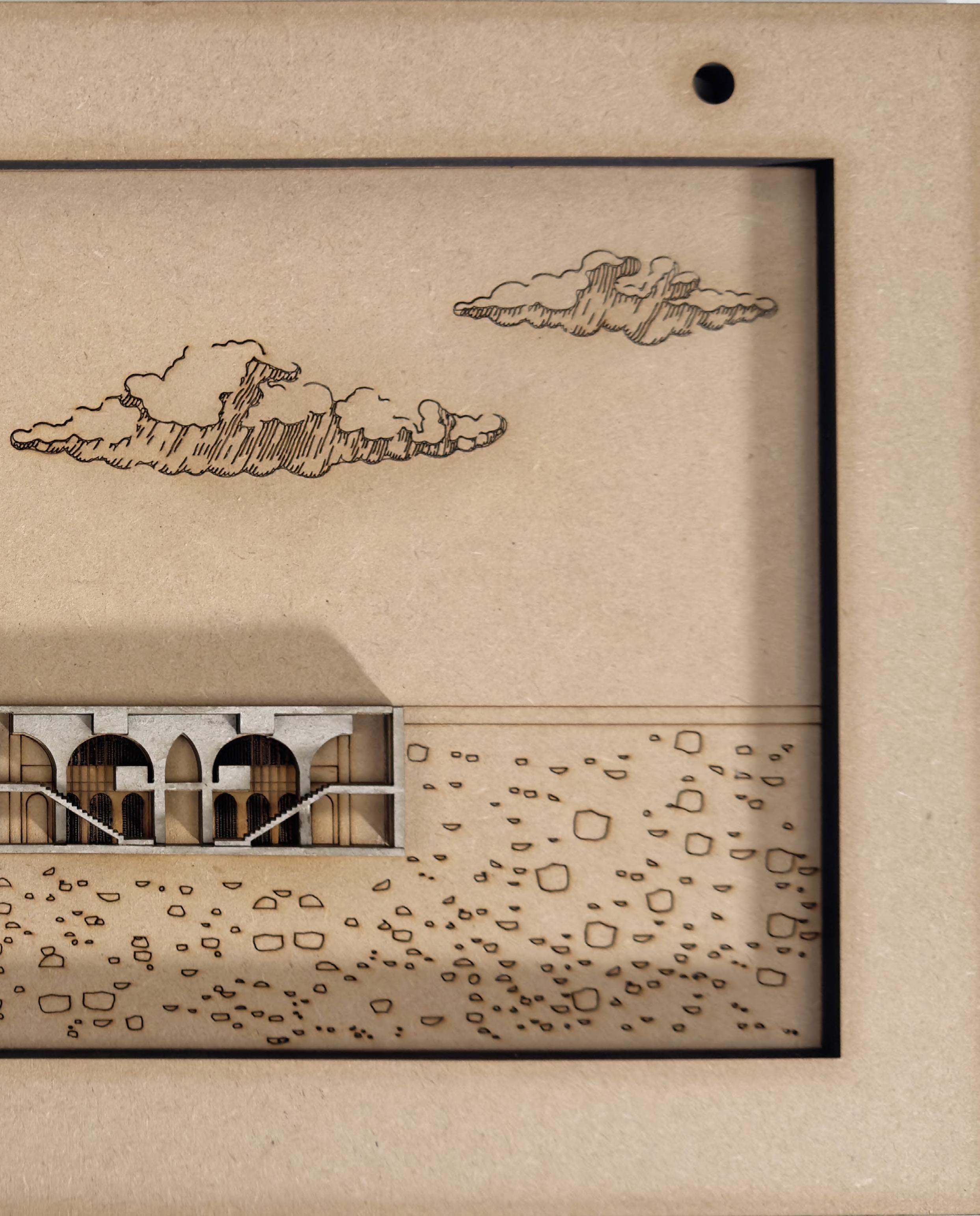

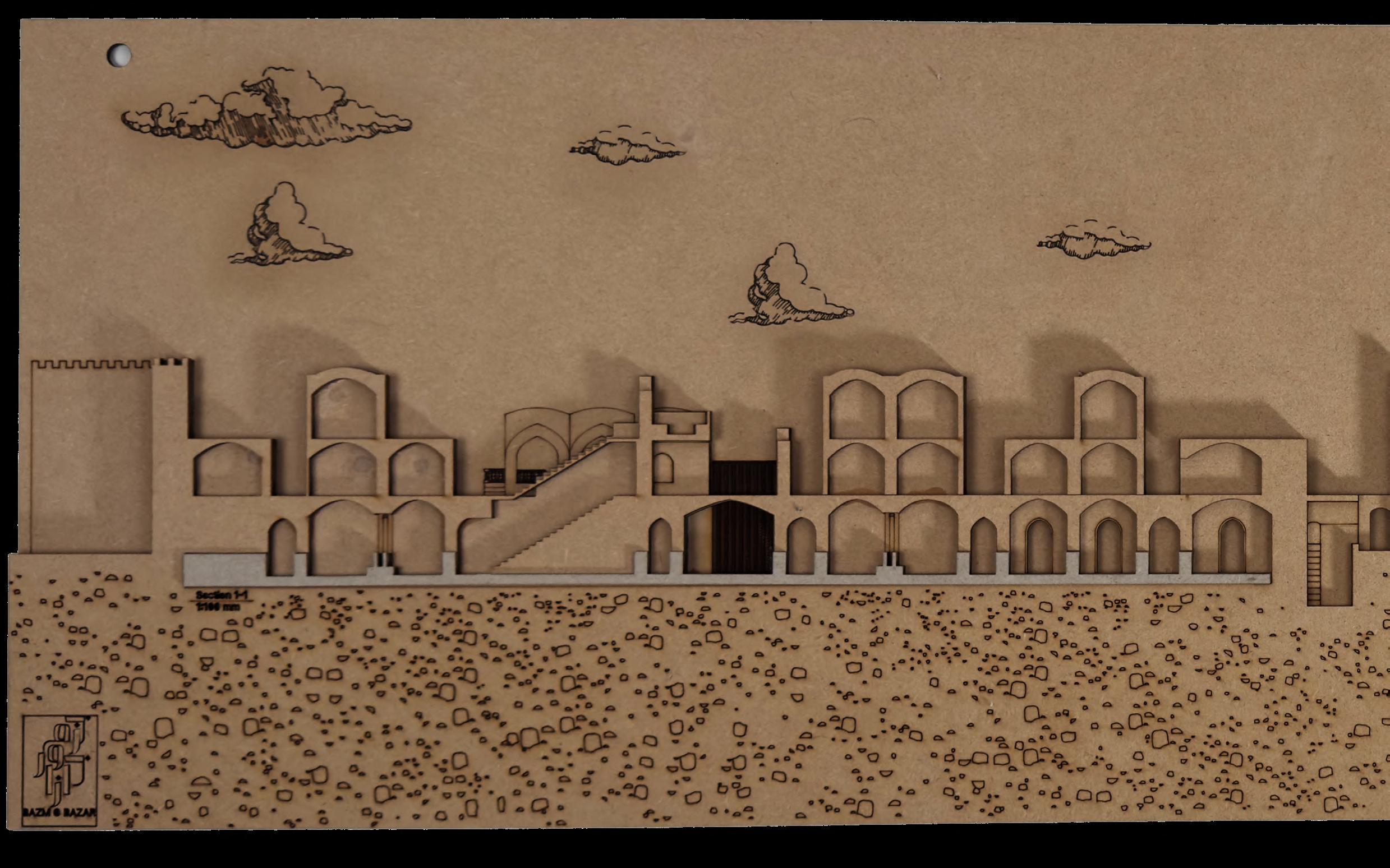

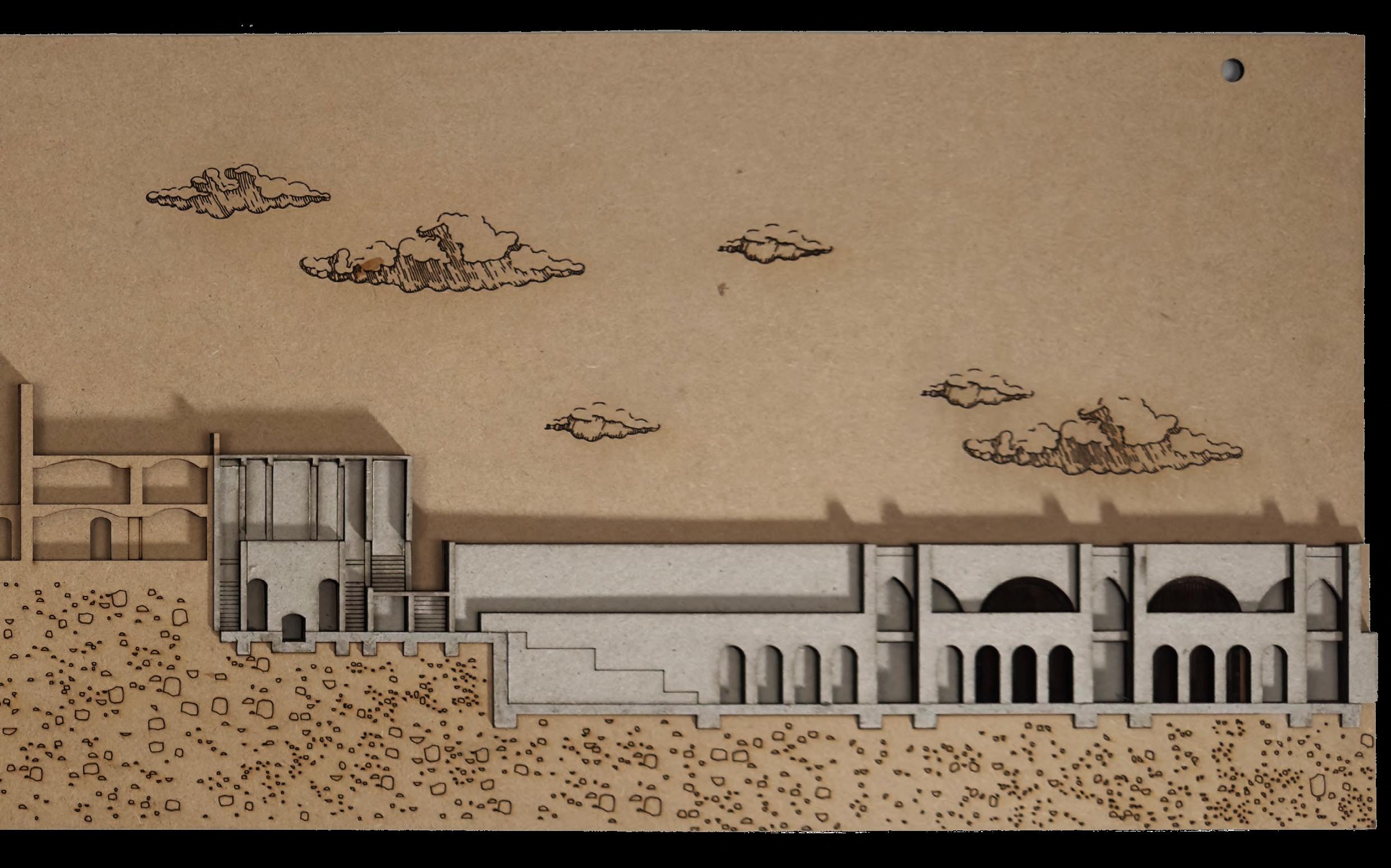

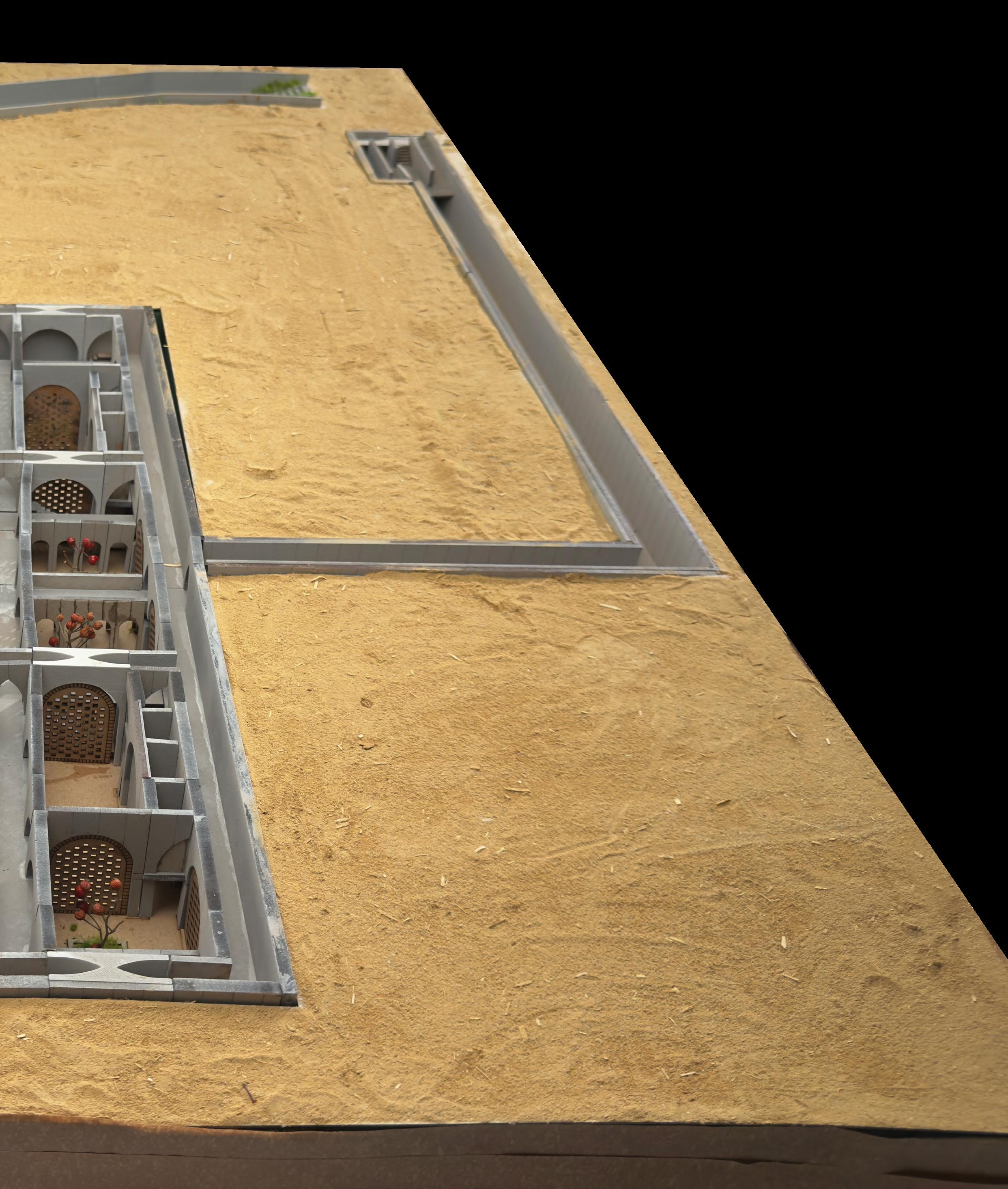

Saryazd Fort is a defensive adobe complex whose primary function was the protection of people and their valuables during periods of invasion. It served as a communal stronghold where food supplies, documents, money, and precious items were secured. The original core of the fort dates back to the Sassanid era, with later expansions ncluding the outer defensive wall constructed during the Safavid period.

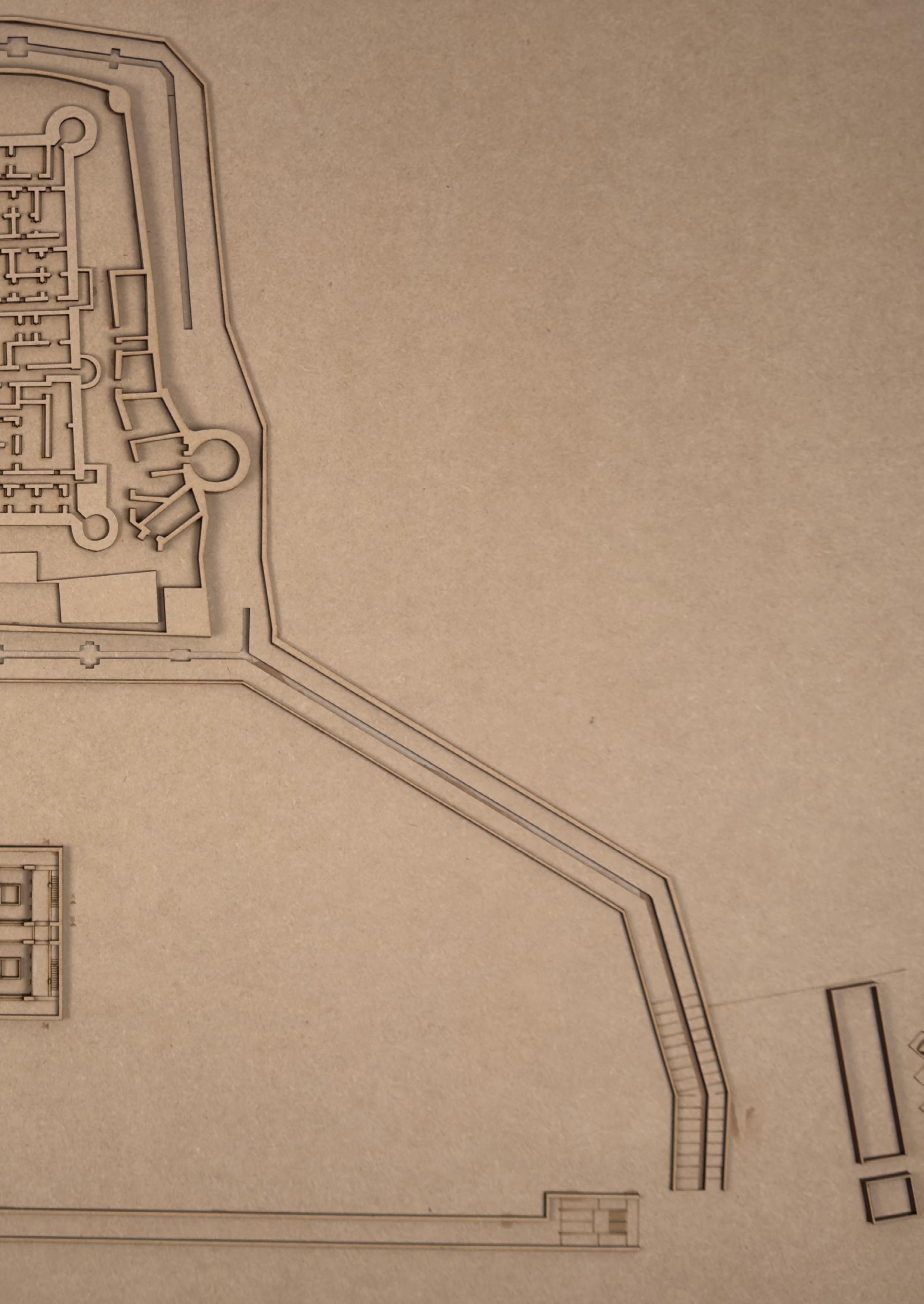

The fort is located beside the village of Saryazd in Mehriz, on the Yazd–Kerman axis in central Iran. Historically, this area lay along a branch of the Silk Road (Jādde-ye Abrīsham), a major east–west trade route. Its strategic location meant that Saryazd was a stopping point for merchants and caravans, functioning as a place of exchange, storage, and contact between Iran and other regions. The need to protect goods, travelers, and local communities against banditry and invasion helps explain the development of such a fortified structure.

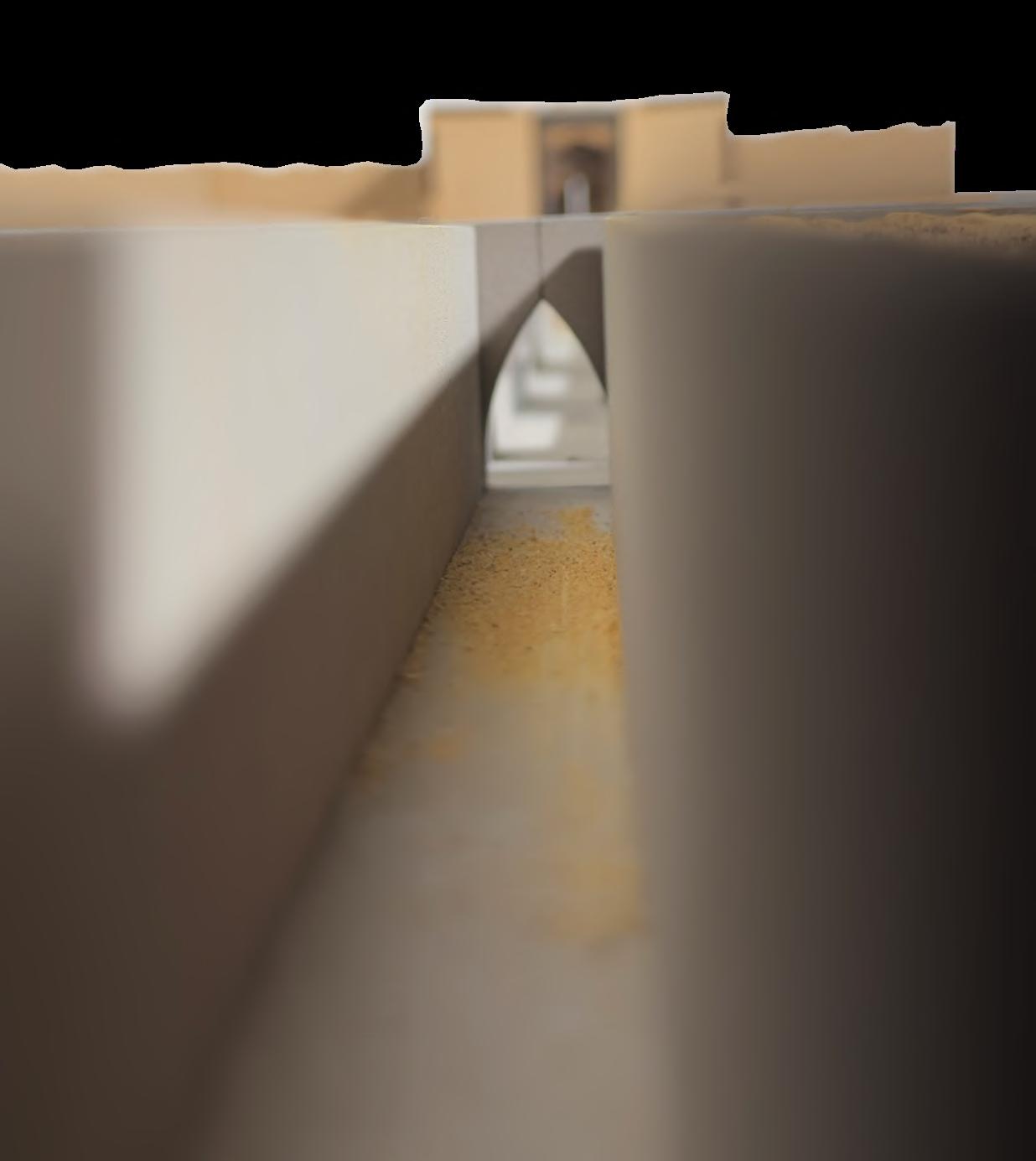

Architecturally, the fort rises vertically in two to three floors and contains around 468 interior chambers. These rooms were assigned to individual families and used as temporary refuge during conflict. Although equipped with small windows and fireplaces, they were not permanent dwellings; they were designed for short-term shelter and secure storage.

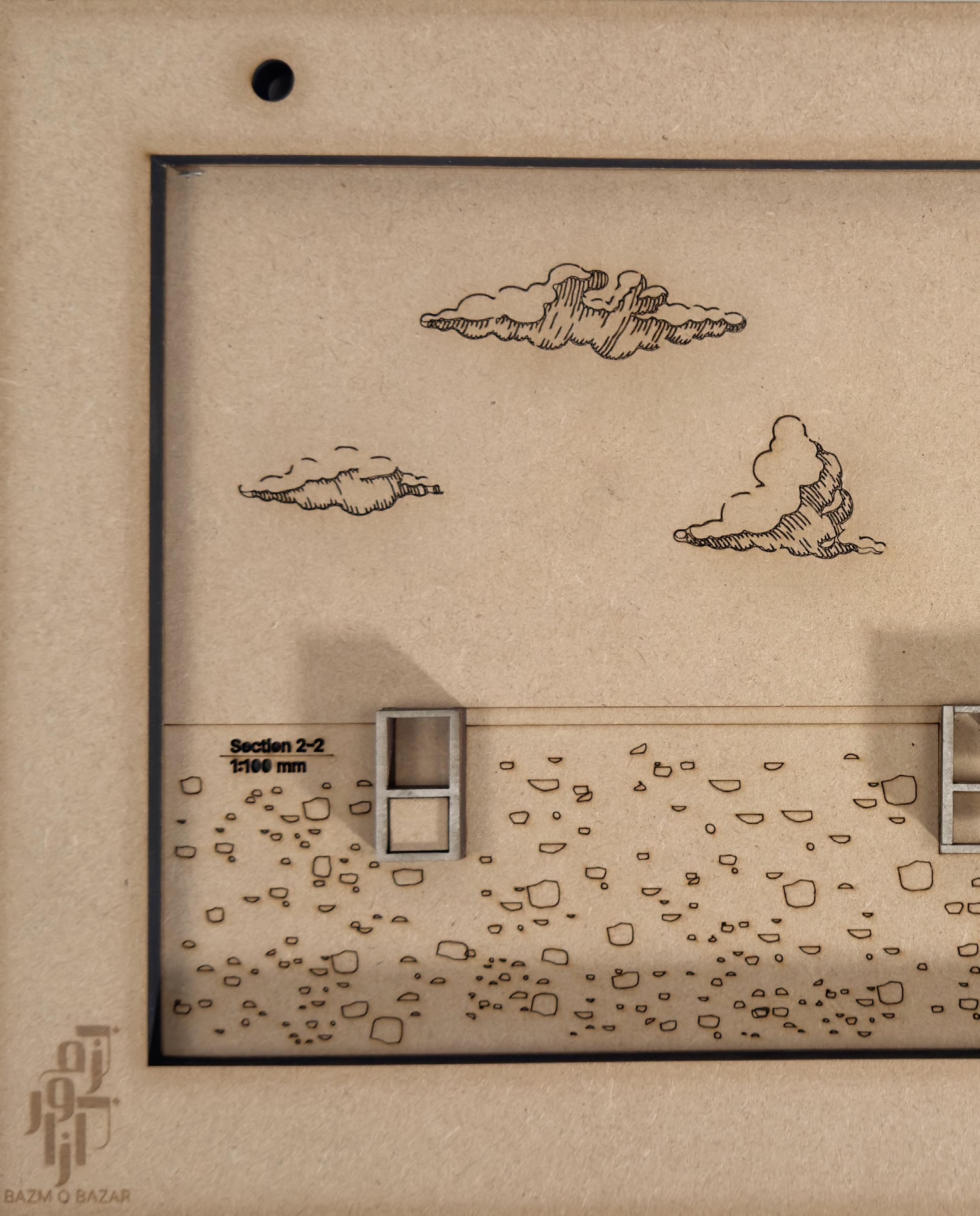

The fort consists of two concentric defensive walls. The inner wall, about nine meters high, includes six circular towers and represents the earliest phase of construction. The outer wall, roughly six meters high, includes three circular towers and one square tower. A surrounding moat approximately six meters wide and four meters deep formed the first line of defense and was originally crossed by a movable wooden bridge.

Saryazd Fort was registered as a national heritage monument in 1975 (no. 1084). Today it stands as one of the most significant adobe fortifications of central Iran, demonstrating how local communities safeguarded property, facilitated trade, and created temporary refuge at a crossroads of regional and international exchange.

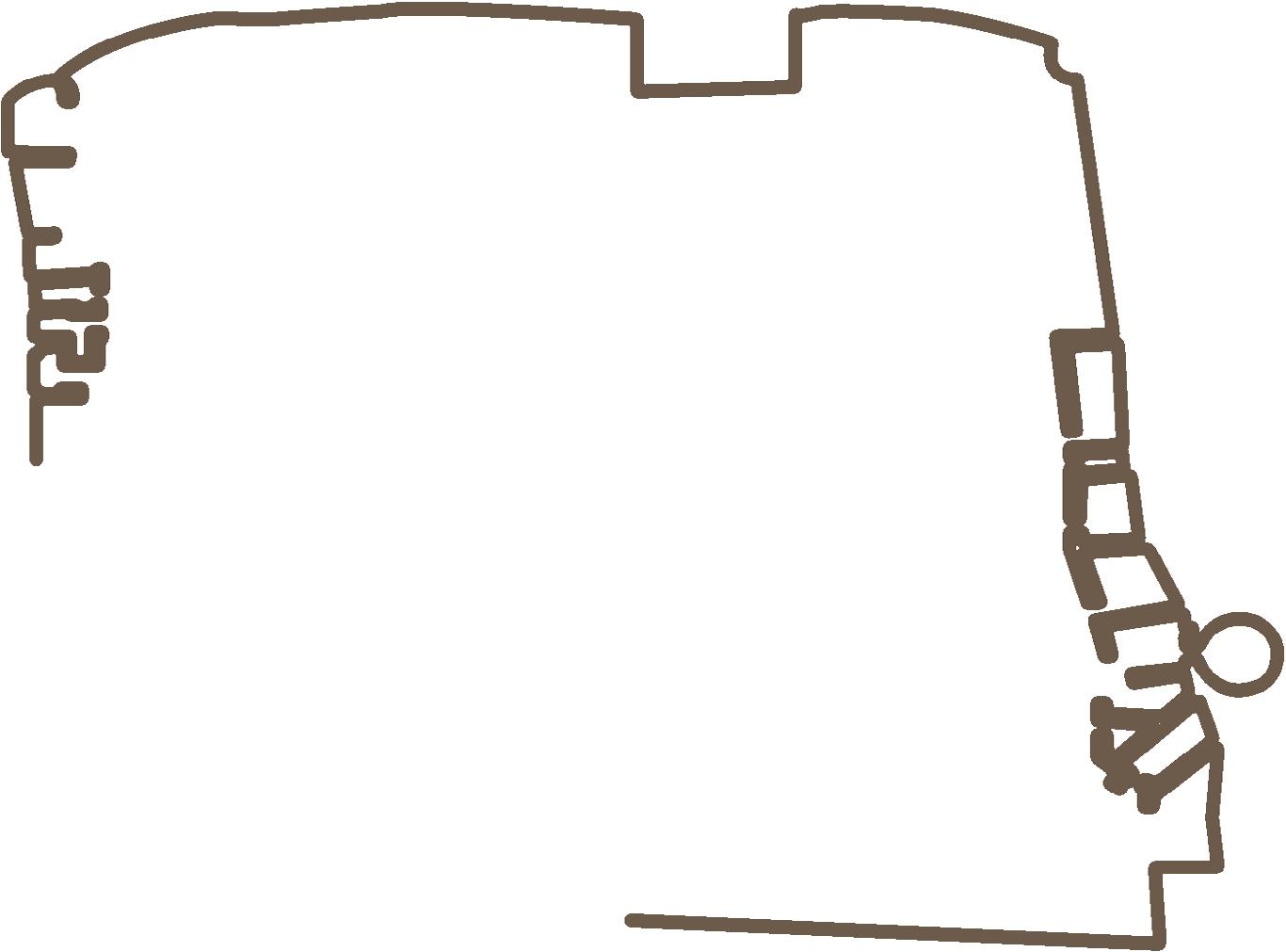

This section studies Saryazd Fort from an architectural perspective. The aim is to understand how the fort’s role as a defensive refuge influenced the way its spaces were organized and constructed. To do this, I analyzed several key aspects: circulation, repetitive patterns and spatial anomalies, views and sightlines, climate and natural light, material use, and space syntax. Each of these reveals how movement, visibility, and security shaped the design.

In the following pages, each aspect is explained separately. Together, these analyses give a clearer picture of how the function of the fort directly shaped its spatial layout and architectural character.

Sightline

Defense towers

Main corridor

Secundary corridors Chambers

The floor plan highlights the Forts dual role as both a defensive stronghold and a secure storage facility. This multifunctionality significantly influenced the circulation patterns.

Impact of defense strategy on circulation in Saryazd Fort

5 Defense Towers: Positioned at 4 corners and one at the middle back to ensure a panoramic view.

Access: Towers are only accessible via the ground floor, not other floors.

Main corridor: One straight, narrow corridor connects to 6 secondary corridors.

Key corridors to towers: The first two and last two secondary corridors lead to the towers.

Defense advantage: Tower placement at the end of corridors makes defenders harder to detect due to the maze-like layout.

Effect of defense strategy on the position of main corridor

Middle Tower Shift: Positioned off the main corridor line for added defense, making it less visible.

Defense towers

Main corridor

Secundary corridors

Chambers

Vertical circulation

Vertical Circulation

Access to upper floors: upper floors and chambers are reached via small stairs located in the main corridor or niches within the adobe walls of the secondary corridors.

Limited stair access: Not every secondary corridor has stairs leading to the upper floors; some stairs are accessed from other corridors on the opposite side of the main corridor.

Narrow stairs for defense: The stairs are very narrow, designed to prevent intruders from easily advancing; only one person can use the stairs at a time, providing a defense advantage.

Limited stair access: Not every secondary corridor has stairs leading to the upper floors; some stairs are accessed from other corridors on the opposite side of the main corridor.

Defender advantage

Visibility for defense: By positioning the stairs in the main corridor, defenders could easily monitor any movement or attempts to ascend. This visibility would allow them to control access to the upper floors and respond quickly to threats.

Strategic control: The main corridor is a key passageway, so having stairs here ensures that access to upper levels is centralized and easily controlled by those defending the fort. It could also serve as a bottleneck, forcing intruders to approach in a predictable manner.

Defense towers

Main corridor

Secundary corridors

Chambers

Access to chambers

Floorplans layout is another aspect which is influenced by the Fort’’s dual role as both a defensive stronghold and a secure storage facility.

Chamber access: The acces to chambers begins from the main corridor, leading to secondary corridors.

Secondary corridors: Each secondary corridor provides access to two rows of chambers.

Defense towers

Main corridor

Secundary corridors

Chambers

Larger rooms

Anamolies

Anomaly one: Chamber size variability

The chambers on the ground floor of Saryazd Fort are primarily used for storing grain and rice. Their sizes vary depending on the needs of the owner, with the larger chambers placed at the back of the corridors, making them the last chambers in the sequence.

Anomaly two: Corridor length variation and Interrupted Corridors The variability in chamber sizes also impacts the length of the corridors, resulting in secondary corridors of differing lengths. Additionally, some corridors are intentionally interrupted, stopping midway rather than extending fully. This interruption creates larger chambers at the ends of these truncated pathways.

Such anomalies enhance the defensive strategy by introducing unpredictability, making it harder for invaders to navigate the fort while simultaneously maximizing functional storage space.

Defense towers

Main corridor

Secundary corridors Chambers

Increased chamber count

Dead-End Corridors & Chamber Counts as result of defence strategy

Dead-end corridors: Designed to limit intruder movement, forcing them to retrace their steps to the main corridor before accessing other sections.

Increased chamber count:The last chamber in each dead-end corridor functions as a storage room, not a passage, increasing the overall number of chambers.

The aspect of view and sightlines plays a key role in the defense strategy. Towers positioned at the four corners and the center of the fort provide a 360-degree view of the surroundings. The middle tower at the front aligns directly with the Shahneshin room (king’s room). This room belonged to the highest-ranking official, who managed the castle and was also the key keeper of the chamber where the most valuable items, such as gold and silver, were stored. The Shahneshin room also played a crucial role in overseeing the main corridor, where most of the stairs were located. It is the only chamber with a visual connection to both the middle front and back towers.

Once invaders were spotted by the soldiers in the defense towers, the news was passed to the soldier in the middle tower, and from there, it was relayed to the Shahneshin room. The four defense towers were aligned in a straight line, maintaining clear visual communication with each other.

llustration 1

temporary shelter storage place

llustration 2

llustration 3

llustration 4

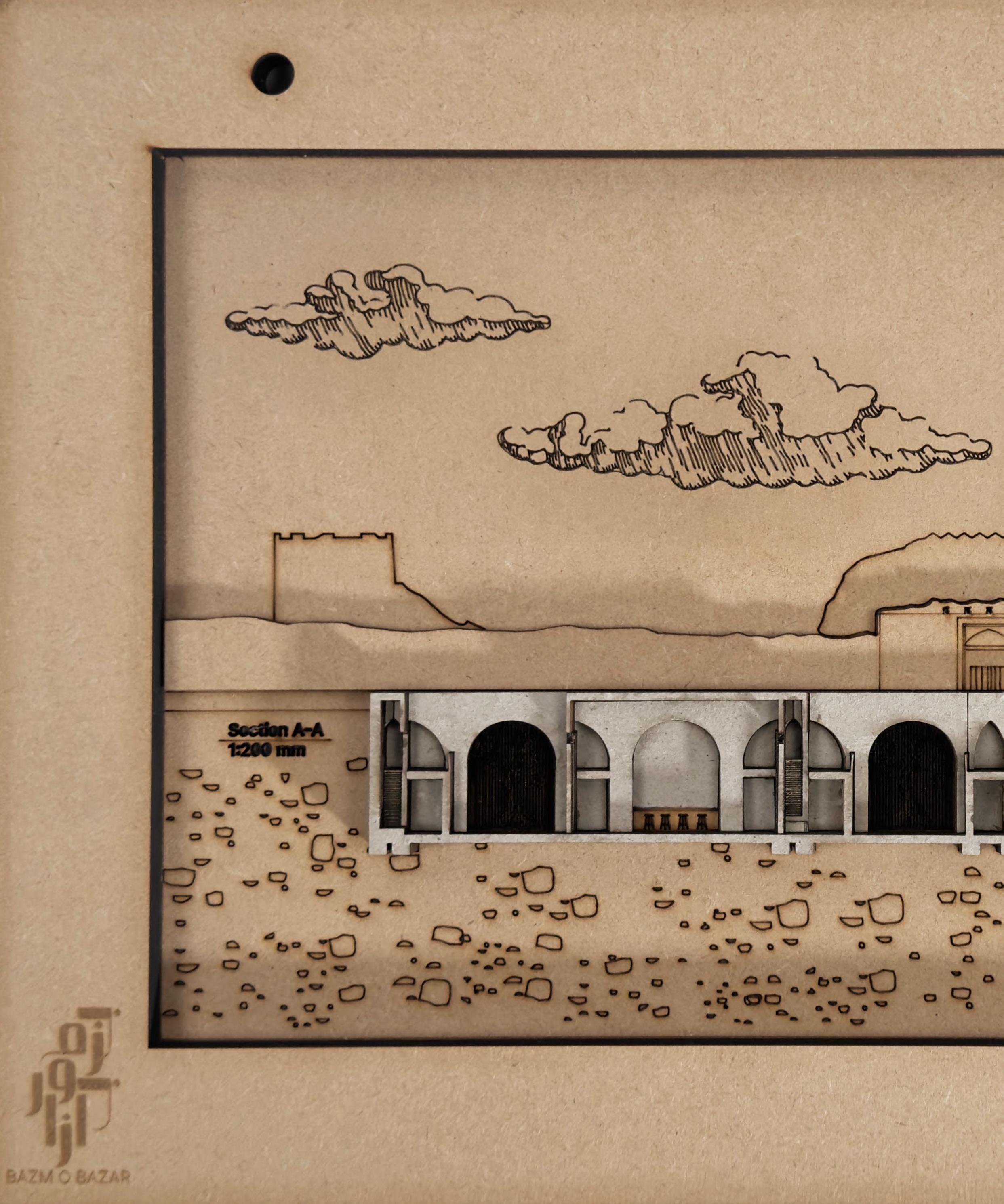

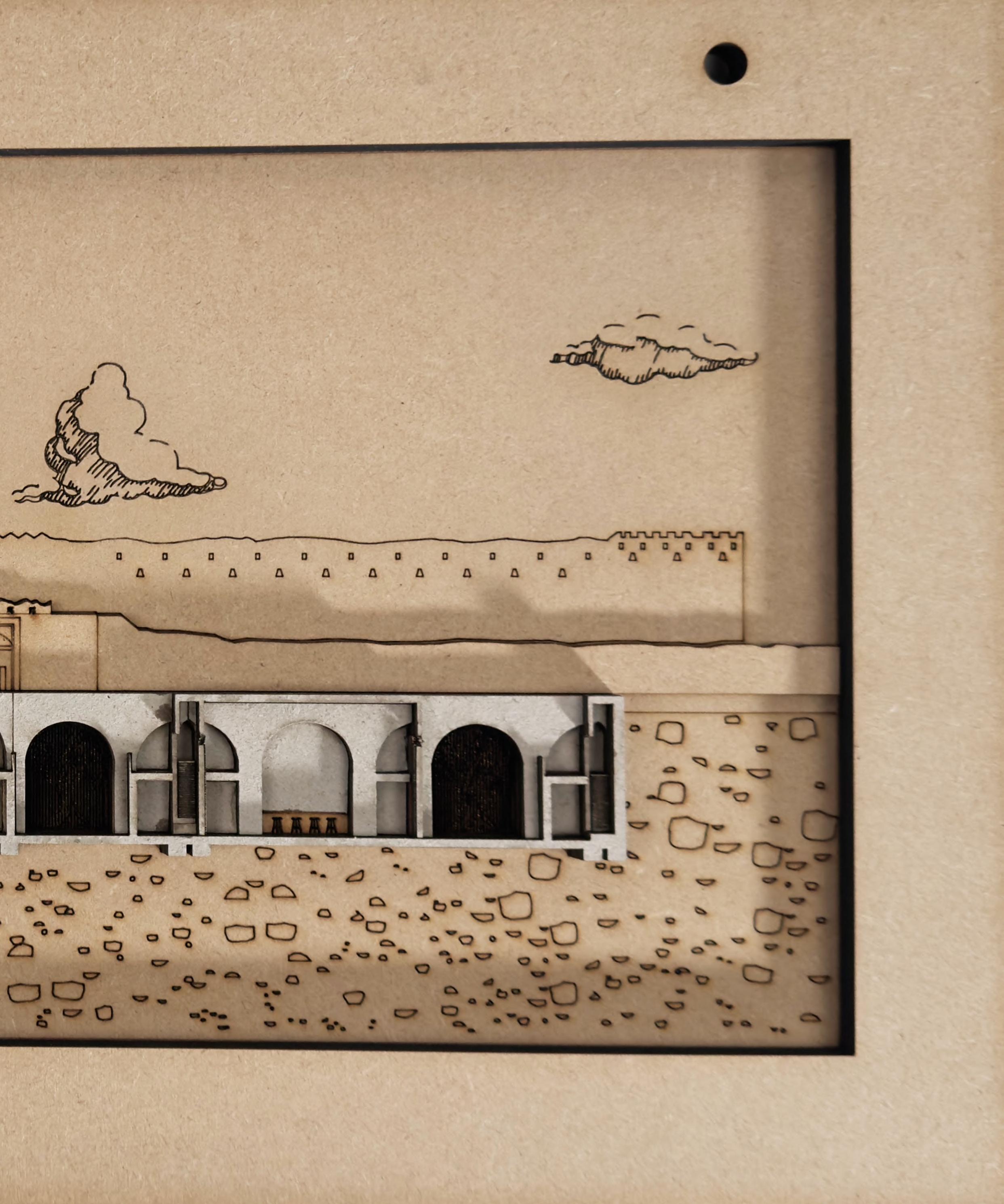

Climate significantly influenced the fort’s design, particularly in the following aspects: program positioning, chamber shapes, heights, thermal comfort, and air circulation.

Below is a breakdown of how the arid climate of Saryazd shaped its architectural features: Program positioning (illustration 1)

Ground floor (Storage):

Chambers on the ground floor were used to store rice and grain.

These chambers lacked windows, making them darker and better suited for grain storage as darkness helps preserve the stored items.

Upper floors (Temporary Shelter & Valuables): The upper floors served as temporary living spaces during invasions and for storing more valuable items.

Vault Roof Design vs. Flat Roofs: Chambers were built with vaulted roofs rather than flat ones. Vaulted roofs maintained lower indoor air temperatures, especially in the arid climate, by:

Enhancing heat dissipation through convection and thermal radiation at night.

Enlarged curved surfaces dissipating heat more effectively compared to flat roofs.

Illustration 2: A dome-shaped building have 30% less surface area than a similar size box building which should result in lower heat transfer to and from its surroundings.

However, a dome shaped Roof has more Surface (curved surface)which helps dissipating heat more effectively compared to flat roofs.

Illustration 3: Vault roof buildings has lower indoor air temperatures as compared to those with a flat roof, because such roofs dissipate more heat than a flat roof by convection and thermal radiation at night due to the enlarged curved surfaces.

Illustration 4: Increased height of the interior allows rising warm air to be trapped at higher levels, which improves occupant comfort level in the lower zone.

Material

Thermal Insulation:

Adobe, made from a mixture of clay, straw, and water, has excellent thermal mass, meaning it can absorb heat during the day and slowly release it at night. In the hot, arid climate of the region, this would help regulate the temperature inside the fort, keeping it cooler during the day and warmer at night.

Spatial Connectivity: The fort’s design demonstrates clear connectivity between spaces. Starting from the bridge, one passes into the entrance hall. From there, movement splits: to the outer bailey on the left and right, leading to spaces like the kitchen and watchtower, or forward through the iron gate to the main corridor. This connectivity ensures logical pathways linking various parts of the fort.

Movement Patterns: Movement is guided by the spatial arrangement. The main corridor serves as the primary axis, branching into secondary corridors that lead to chambers and ultimately to defense towers. This hierarchical structure encourages organized movement while making specific areas, such as the towers, less accessible to intruders.

Integration and Segregation: The outer bailey and entrance hall are more integrated spaces, offering multiple access points and routes. In contrast, deeper spaces like the chambers and defense towers are more segregated, reflecting their defensive purpose and limited accessibility.

Visual Field and Sightlines: Visibility plays a significant role in how spaces influence movement. For instance, open areas like the entrance hall and outer bailey encourage fluid interaction and movement. In contrast, the main corridor narrows visibility and creates a controlled flow, emphasizing the fort’s defensive strategy.

This chapter brings together the insights gained from the previous chapters and translates them into a clear design direction. It outlines how the principles studied in Chapter One, typologies, historical timelines, and Yazd’s architectural traditions, together with the spatial and architectural analyses of Saryazd Fort in Chapter Two, will inform the design concept. The aim is to show how these findings will shape the spatial strategy of the project. Ultimately, this chapter turns analytical observations into a coherent architectural approach that respects the heritage of Yazd while responding to contemporary needs and helping the Saryazd Fort become relevant again.

07. Design directions

08. Concept

Saryazd Fort is at risk of becoming disconnected from the needs of contemporary life. Although it is a significant heritage site, its original social role has faded, and without a meaningful function it faces the danger of being forgotten. The aim of this project is to propose an architectural approach that restores the fort’s relevance by reconnecting it to the community it once served.

For me, innovation is not about creating something new for its own sake. It is about creating relevance, making architecture meaningful to its place, its people, and its history. A place endures when it responds to the needs of its community and becomes a setting for social life, identity, and local economy. This project follows that principle. It looks at how the fort can once again support everyday life while respecting its historical character.

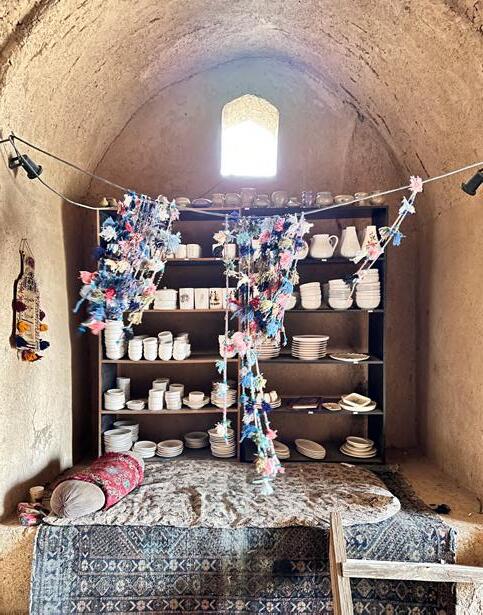

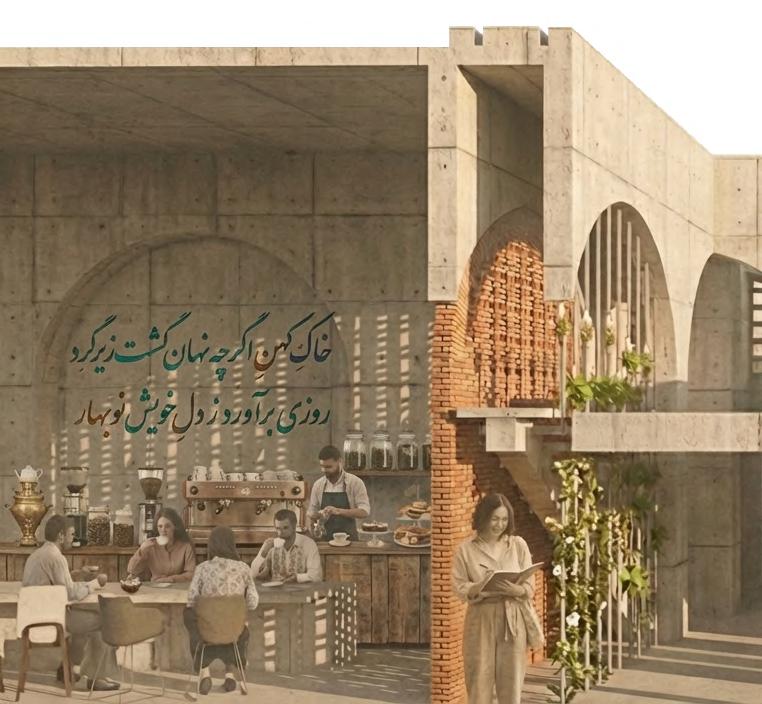

The analyses carried out in Chapters One and Two, studies of Yazd’s traditions, spatial typologies, and the architectural characteristics of Saryazd Fort show that the spatial logic of the fort already contains the potential for renewed use. Historically, the ground floor served as storage, and this project maintains that logic while expanding it into a small-scale bazaar that can support the economic life of Saryazd’s villagers. However, adding a new function alone is not enough to make the fort relevant again.

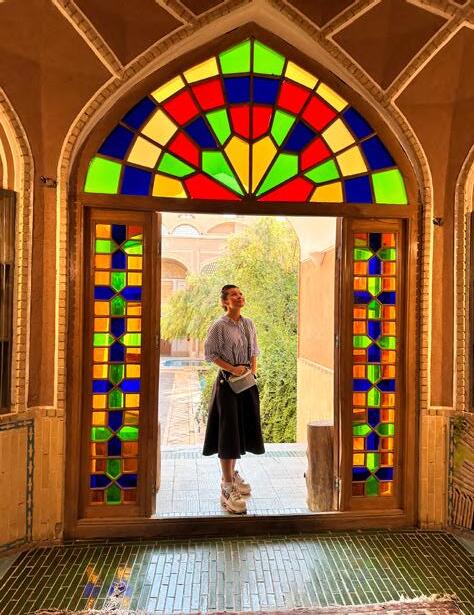

To truly reconnect the fort to its people and its context, the project introduces a new passage inspired by Iranian culture, traditions and architectural elements. This passage is designed not as an addition, but as a continuation of the spatial language found across Yazd. It follows the same principles seen throughout the region: inward-oriented paths, shaded walkways, climate-responsive spaces, and areas that encourage social interaction. By creating this connection, the fort can become accessible and active again, allowing it to regain its role as a meaningful place for the community.

This section identifies the architectural typologies and spatial principles that shape the design direction. It explains how the findings from cultural traditions, Yazd’s urban patterns, and the architectural analysis of Saryazd Fort inform the next step of the project. These insights provide the foundation for developing a design that is grounded in heritage while responding to contemporary needs

Temporary shelter / museum Bazaar

Local crafts and Goods

Spaces for pottery and handmade products preserve village craftsmanship and extend traditions already present in the fort.

Vegtable & Fruit

A produce section supports Saryazd’s farmers and brings their harvest directly into the heart of the community.

agriculture supplies

Selling tools and farming materials makes the bazaar a practical service hub for local agricultural life.

Art & Culture

Small studios or workshops keep Iran’s tradition of community arts alive and add cultural activity to the bazaar.

A: Respect for historic context

The fort architectural integrity will be maintained

B: Strengthen spatial experiment

Traditional materials such as Adobe will be protected

The existing sense of disorientaion will be reinforced by the maze like layout

C: Climate responsive design

Circulation will encourage exploration

The project will allow for future layers of history, ensuring that new additions do not erase the past but complement it

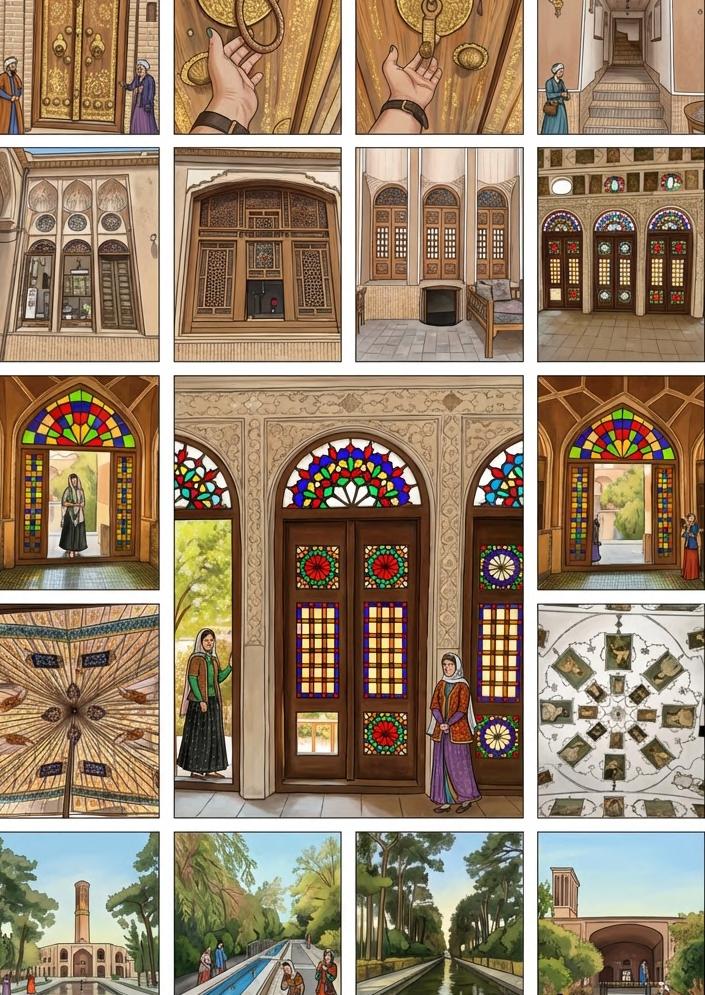

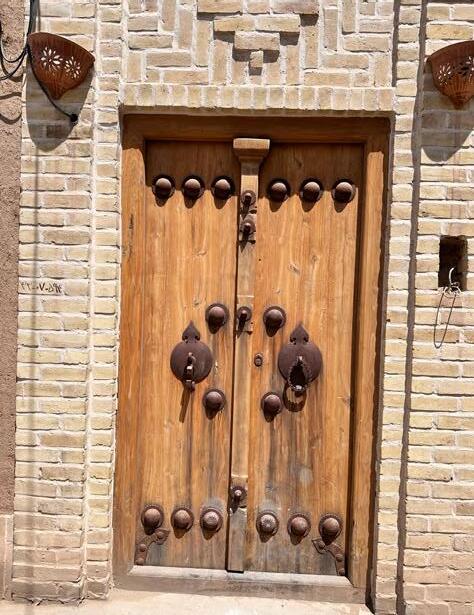

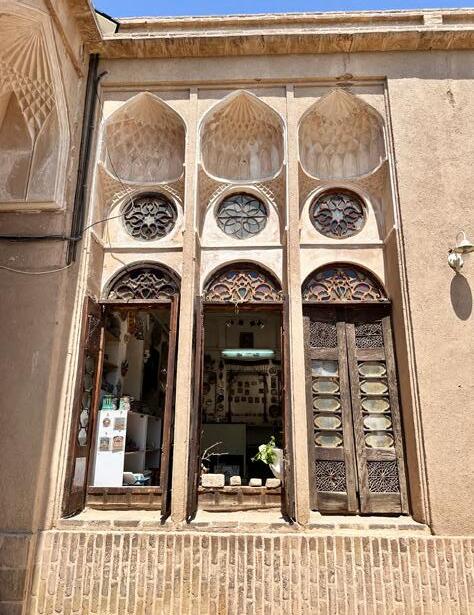

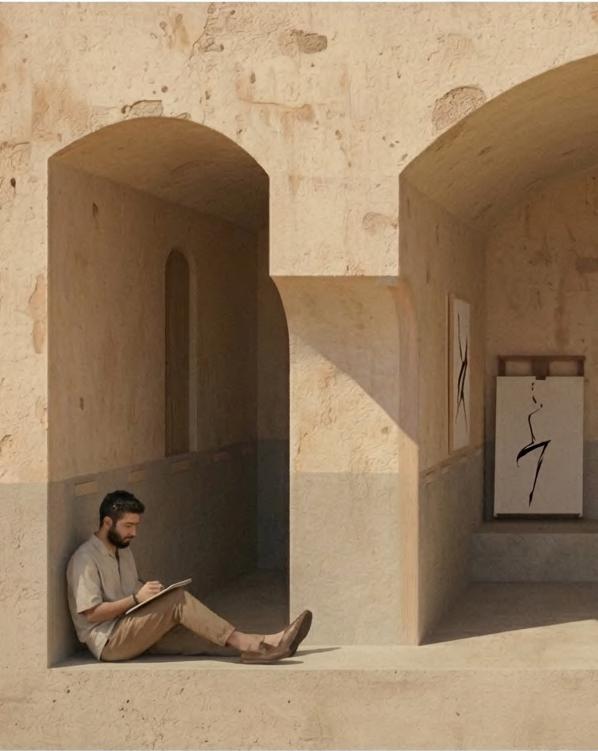

A selection of elements and spaces by which the design is inspired

A selection of elements and spaces by which the design is inspired

A selection of elements and spaces by which the design is inspired

A selection of elements and spaces by which the design is inspired

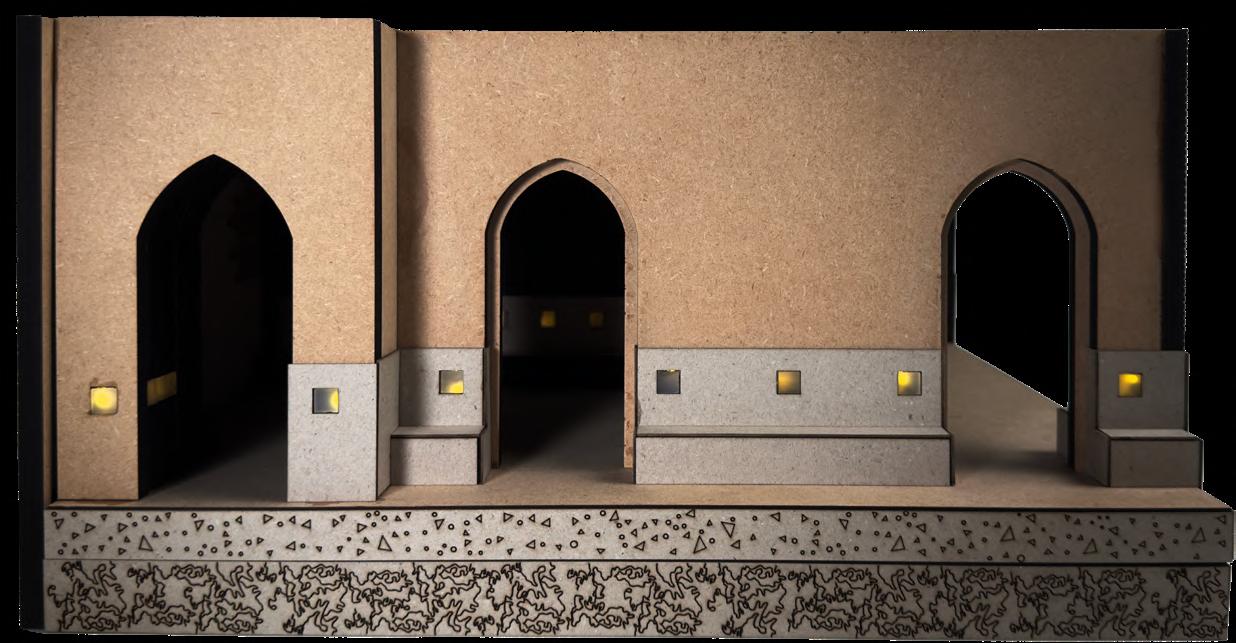

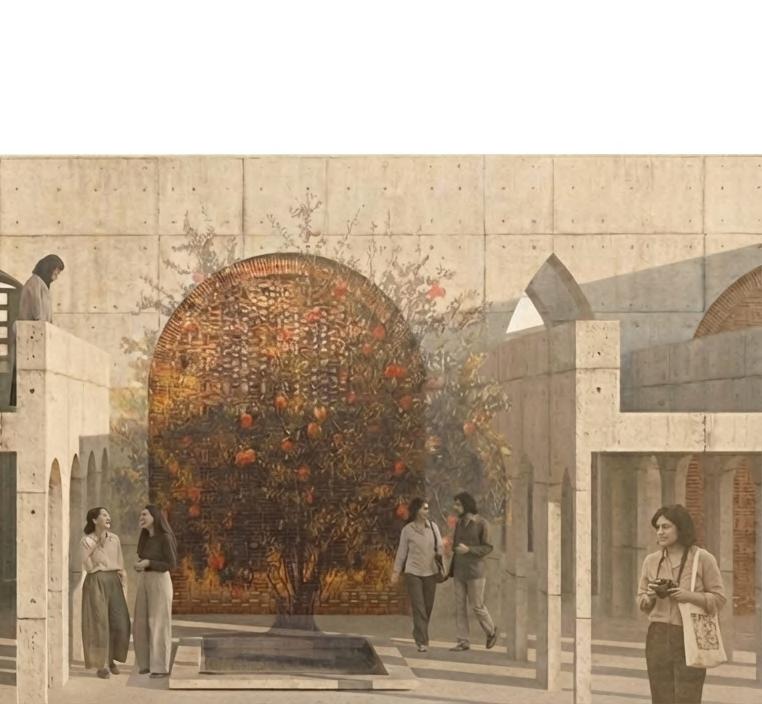

This section presents six conceptual scenes that show how the spaces of Saryazd Fort can evolve from their current condition into a meaningful visitor experience. Each scene compares the existing situation with a proposed transformation moving from isolation to integration, shaping a ritual of entry, guiding visitors through a maze of discovery, activating the chambers, and creating a thoughtful moment of departure.

These scenes focus on how the fort itself can regain relevance, while the new passage is conceived as a natural continuation of the same architectural logic. Its form and spatial qualities are inspired by the selection of architectural elements and spaces shown in the previous section. Together, the fort and the passage form one coherent strategy that leads into the full design proposal developed in Chapter Four.

From isolation TO integration existing

A ritual of Entry existing

A ritual of Entry - A moment of joy future

A ritual of Entry - Entering the Fort future

existing future

A maze of discovery

Experiencing chambers existing

A ritual of leaving existing

Chapter Four

Fruit and Vegetable Chamber

& pomegranate trees

Acknowledgement

This project made me learn a lot about my culture, heritage, and our past, and without the help of my mentor, my committee members, and external advisors it wouldn’t have been possible. Therefore, I especially thank my mentor, Hans van der Heijden, who guided me through this challenging process.

To my dear committee, Yonca Ercan and Milad Pallesh, I sincerely thank you for your eyeopening advices.

Throughout my trip to Iran, I had the great chance to meet wonderful people in the field of architecture. I am truly honored to have met you. Therefore, a special thanks to Torab Home, and a sincere thank you to Niloofar Moji-Jan and Hani Shayegh-Jan for enlightening me through their valuable experience and showing me their beautiful projects.

I am also beyond happy that I happened to watch the video made by Hasty Fallahzadeh, and even happier that I had the chance to meet Hasty-Jan during my trip and learn so much from her.

I would like to thank my parents, who immigrated 17 years ago to give us the chance to study, a chance they never had themselves. Also my kind, supportive sisters, who were always there for me.

And to end on a personal note, my partner, Arash Khajehzadeh, who supported me in every possible way.

Bibliography

Ahmadinia, R., & Shishegar, A. (2019, April 22). Jubaji, a Neo-Elamite (Phase IIIB, 585–539 BC) tomb in Ramhurmuz, Khuzestan. Iran, 57(2), 142–174. https:// doi.org/10.1080/05786967.2018.1532771

Ardalan, N. (1986, December 15). Architecture VIII. Pahlavi, after World War II. In Encyclopaedia Iranica (Vol. II, Fasc. 4, pp. 351–355). Retrieved from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/architectureviii/?highlight=Architecture

Beigli, F. (n.d.). Underground and semi-underground passive cooling strategies in hot climate of Iran. Department of Engineering, La Sapienza University of Rome.

Beigli, F., & Lenci, R. (n.d.). Underground and semiunderground passive cooling strategies in hot climate of Iran. Journal of Environmental Science. Retrieved from http://environment.scientific-journal.com/

Bishapur memorial columns [Photograph]. (n.d.). Iran Marco Polo. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from https:// www.kavehfarrokh.com/arthurian-legends-and-iraneurope-links/the-ancient-sassanian-city-of-bishapur/

Blank, L. (2018, June 21). Nasir al-Mulk Mosque. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/ places/nasir-al-mulk-mosque

Boyce, M. (1979). Zoroastrians: Their religious beliefs and practices. Routledge.

Boyce, M. (1989). Haft sīn. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://iranicaonline.org/articles/haft-sin

Boyce, M. (1989). Nowruz. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://iranicaonline.org/articles/ nowruz-i

Calmard, J. (2000). Moḥarram rituals. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://iranicaonline.org/articles/ moharram-rituals

Grabar, O. (1986, December 15). Architecture v. Islamic, pre-Safavid. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/architecturev/?highlight=Architecture

Hillenbrand, R. (1986, December 15). Architecture VI. Safavid to Qajar periods. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ architecture-vi/?highlight=Architecture

Hovannisian, R. G., & Sabagh, G. (Eds.). (1998). The Persian presence in the Islamic world. Cambridge University Press.

Huff, D. (1986, December 15). Architecture III. Sasanian period. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/architectureiii/?highlight=Architecture

Huff, D., & O’Kane, B. (1990). Čahārṭāq. In Encyclopaedia Iranica (Vol. 4, Fasc. 6, pp. 634–642). Retrieved August 14, 2018, from https://iranicaonline. org/articles/cahartaq

Hultgård, A. (2018). Iranian festivals. In Encyclopedia of Jewish–Christian relations (pp. 1–6). Springer. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1153-8_246-2

IranTourismer. (2019). Persian garden | Paradise on earth. Retrieved from https://irantourismer.com/persiangarden/

Iranian society of the 70s [Photograph]. (1970). Historypin. Retrieved from https://www.historypin. org/en/explore/geo/37.77493,-122.419416,12/boun ds/37.609889,-122.558977,37.939604,-122.279855/ paging/1/pin/201276

Islamic Republic News Agency. (2021, January 12). Iran to mend ancient Iranian Taq-e Kasra monument in Iraq. Retrieved from https://en.irna.ir/news/84182954/ Iran-to-mend-ancient-Iranian-Taq-e-Kasra-monumentin-Iraq

Jaffari, M. (2024). مدرسه در تاریخ [School in history]. Retrieved from https://dbamag. ir/360707/%D9%85%D8%AF%D8%B1 %D8%B3%D9%87-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%AA%D8%A7%D8%B1%DB%8C%D8%AE/

Jameh Mosque of Isfahan. (n.d.). PersianTouring. Retrieved from https://persiantouring.com/things-todo/jameh-mosque-of-esfahan/

Kowkabi, L. F. (2018, September). Baze Hoor fire temple [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons. wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baze_Hoor_fire_temple.jpg

Mahmoudi Farahani, L., Motamed, B., & Jamei, E. (2016). Persian gardens: Meanings, symbolism, and design. Landscape Online, 46, 1–19. https://doi. org/10.3097/LO.201646

Mahmoudi Zarand, M. (2007). Wind catcher symbol of the image city in Yazd. Baghe Nazar, 5, 97.

Mehraby, R. (2021, February 23). What are the attractions of heritage tours of Iran? Destination Iran. Retrieved from https://www.destinationiran.com/whatare-the-attractions-of-heritage-tours-of-iran.htm

Mirahmadian, B. (n.d.). Ruïnes van het Paleis van Tachara of het Paleis van Darius in Persepolis, Shiraz [Photograph]. Dreamstime. Retrieved from https:// nl.dreamstime.com/stock-foto-ru%C3%AFnes-vantachara-paleis-paleis-van-darius-persepolis-van-shirazimage72757783

Movahed, K. (2016). Badgir (wind catcher): An example of traditional sustainable architecture for clean energy. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE).

Nikzad, N. (2018, March 21). Persian New Year Nowruz! Part 1. Roya Project. Retrieved from https://royaproject. wordpress.com/2018/03/21/persian-new-yearnowruz-part-1/

Saiwalla, C. (2020, December 26). Baghe Shazdeh Mahan in Iran: Historical garden; travel, culture, history; Aban. Retrieved from https://cyrus49.wordpress. com/2020/12/26/baghe-shazdeh-mahan-in-iranhistorical-garden-travel-culture-history-aban/

Stanley, D. (2014, September 23). Tomb of Cyrus. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/ places/tomb-of-cyrus

The Independent. (2016, May 23). Rules on “Islamic dress” for women are enforced by police in Iran [Photograph by Majid Saeedi]. Retrieved from https:// www.independent.co.uk/news/people/iranian-womencut-hair-off-and-dress-as-men-to-avoid-moralitypolice-a7041236.html

The Shahnameh: A literary masterpiece. (n.d.). The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Retrieved from https://shahnameh.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/literary

UNESCO Nederland. (n.d.). Masjed-e Jame van Isfahan. Retrieved from https://unesco.nl/werelderfgoed/masjede-jame-van-isfahan

This project began from a place of pure curiosity - a curiosity that, for many of us born in Iran, has always been a quiet act of courage. Growing up in a deeply religious family, questioning what I was told was never truly welcomed.

Yet somewhere inside, that small spark of wondering never died. Choosing this location, Saryazd, was my way of following that spark.

Through this journey, my eyes opened to a world I had never been allowed to see, a world that existed long before us, yet remained out of reach.

A world built by hands that understood space, meaning, and belonging,in ways our present time has forgotten.

It is a shame a painful one that Iranian monuments, rich with history, architecture, and untold lessons, stand on the edge of disappearing.

These are not just structures; they are classrooms without teachers, stories without voices, and mirrors reflecting who we once were.

From them, we can learn about architecture, about public life, about the spirit of a space, and about the profound intelligence hidden in our architectural heritage.

My hope is simple:

That the young generation of Iran will never stop asking questions.

That we reclaim our right to be curious, to explore, to doubt, to rediscover. Because I know, with certainty, that by digging into our past, a brighter future reveals itself patiently waiting for us to return to it.