ENCHANTING THE WATERMACHINE

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

JEFFREY VAN DER SLUIJS

MIRTE VAN LAARHOVEN

LADA HRŠAK

RENS WIJNAKKER

ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE

AMSTERDAM

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s fictional novel BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN unconsciously planted its seeds of inspiration in me several years ago. As he portrays stories of how peoples lives in Bangkok have come and gone over two centuries, he made me feel at home in a place that wasn’t innately mine being raised elsewhere.

In his title he reframes Bangkok’s relationship with water not as a modern crisis, but as a rhythm the city has always lived by. Just as the novel’s characters awaken to a city defined by rain, this thesis calls for an awakening to the need to look beyond the rigid ‘watermachine’ and rediscover the ‘amphibious intimacy’ that the rain has always demanded.

My academic path has been a journey toward that same awakening. I began with a Bachelor’s in Water Management in Rotterdam and continued with a Master’s in Landscape Architecture at the Academie van Bouwkunst in Amsterdam. These experiences shaped my understanding of landscape architecture, evolving from a technical practice into a critical way of engaging with complex environmental, social, and infrastructural challenges.

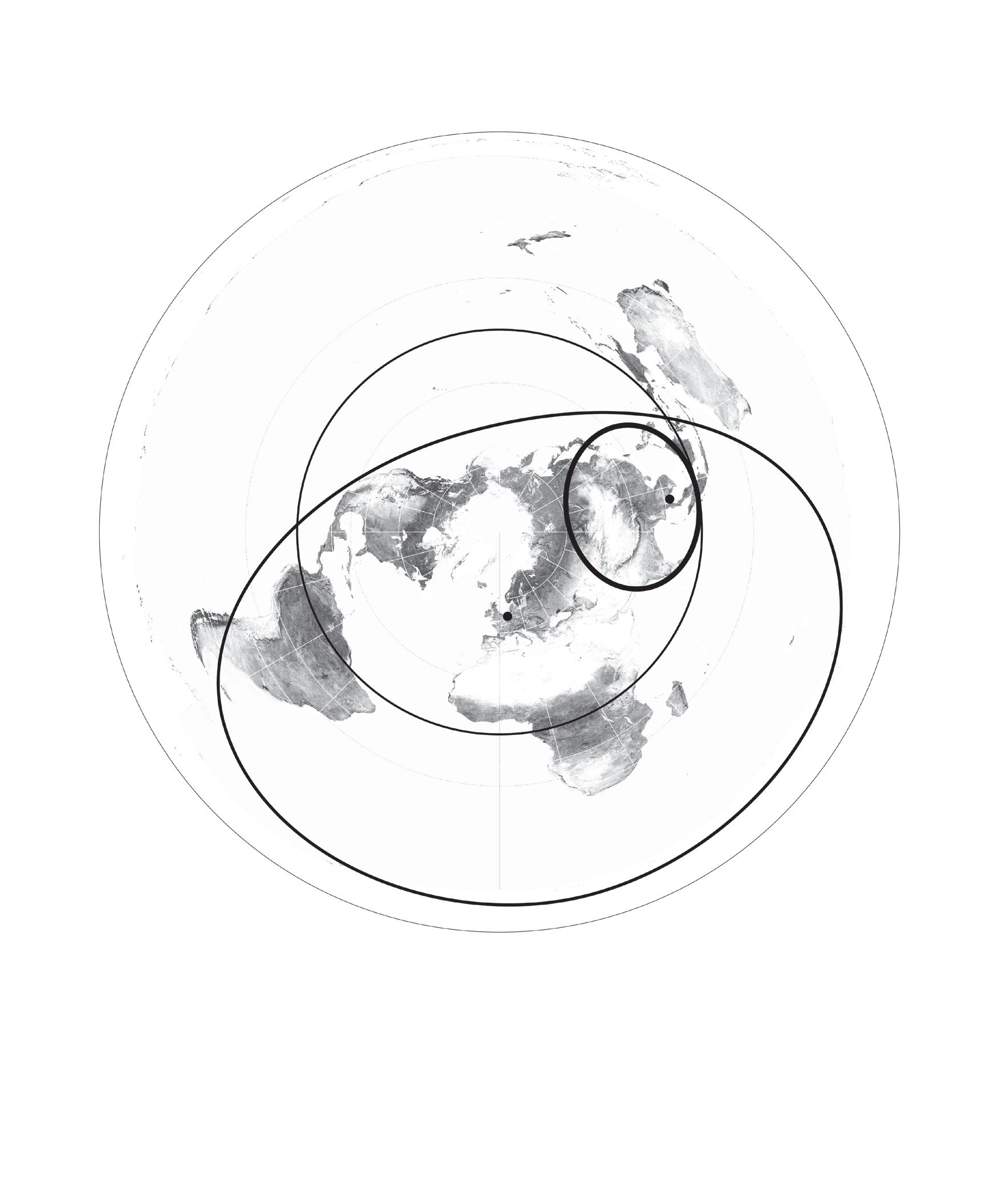

One image, the “Valerie Pieris Circle,” serves as a spatial reminder of the global stakes: over half the world’s population lives within this 4,000 km radius, including Thailand. As climate change and urbanisation intensify, this region’s landscapes become a key site for adaptive strategies.

This project is not only analytically urgent but personally resonant. It traces the confluence of my family’s journey between Thailand and the Netherlands while interweaving diasporic memory, lived experience, and inherited knowledge.

With this thesis, I aim to embrace a more situated and locally grounded approach to landscape challenges in Thailand. Approaches that may hold relevance across similarly vulnerable landscapes within the Valerie Pieris area. This will be complemented by methods and insights drawn from my education and experience in the global north

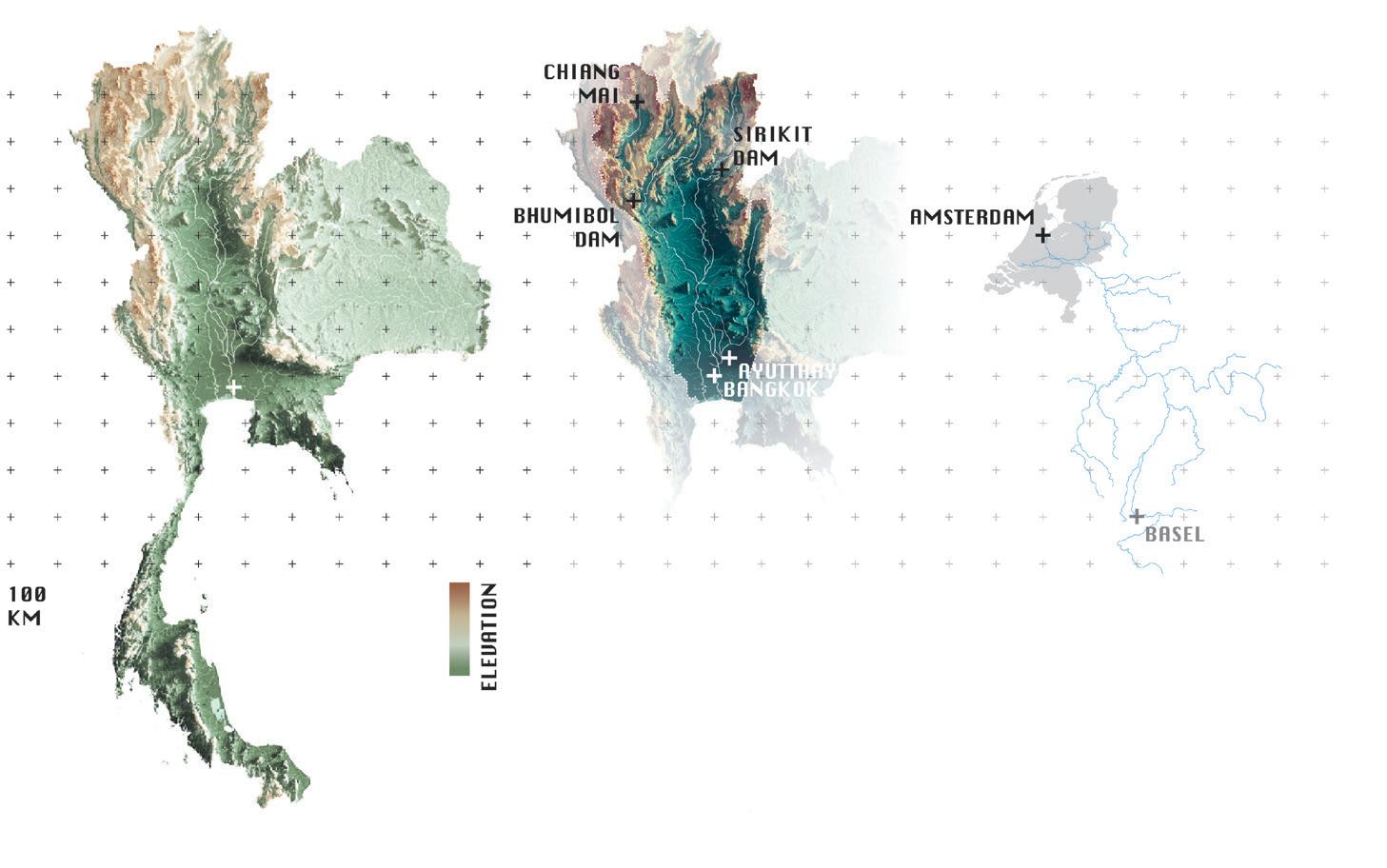

DATA SOURCE: KIRMA, J. 2023

PRE-FACE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ORIGINS

RECOGNISING

LIQUID LEGACIES

.1 Situating Thailand

.2 Why Bangkok?

.3 A Hydro-Cultural panorama

.4 Growth and Decline

.5 Geo-Choreographies

CRISIS

DE-CONSTRUCTING THE WATERMACHINE

.1 One Generation

.2 The Big Flood of 2011

.3 Flooding Causes

.4 Resist and Discharge

.5 Walls of Inequality

.6 Bangkok Through Time

.7 Anti-Fragility

.8 Loss of Green

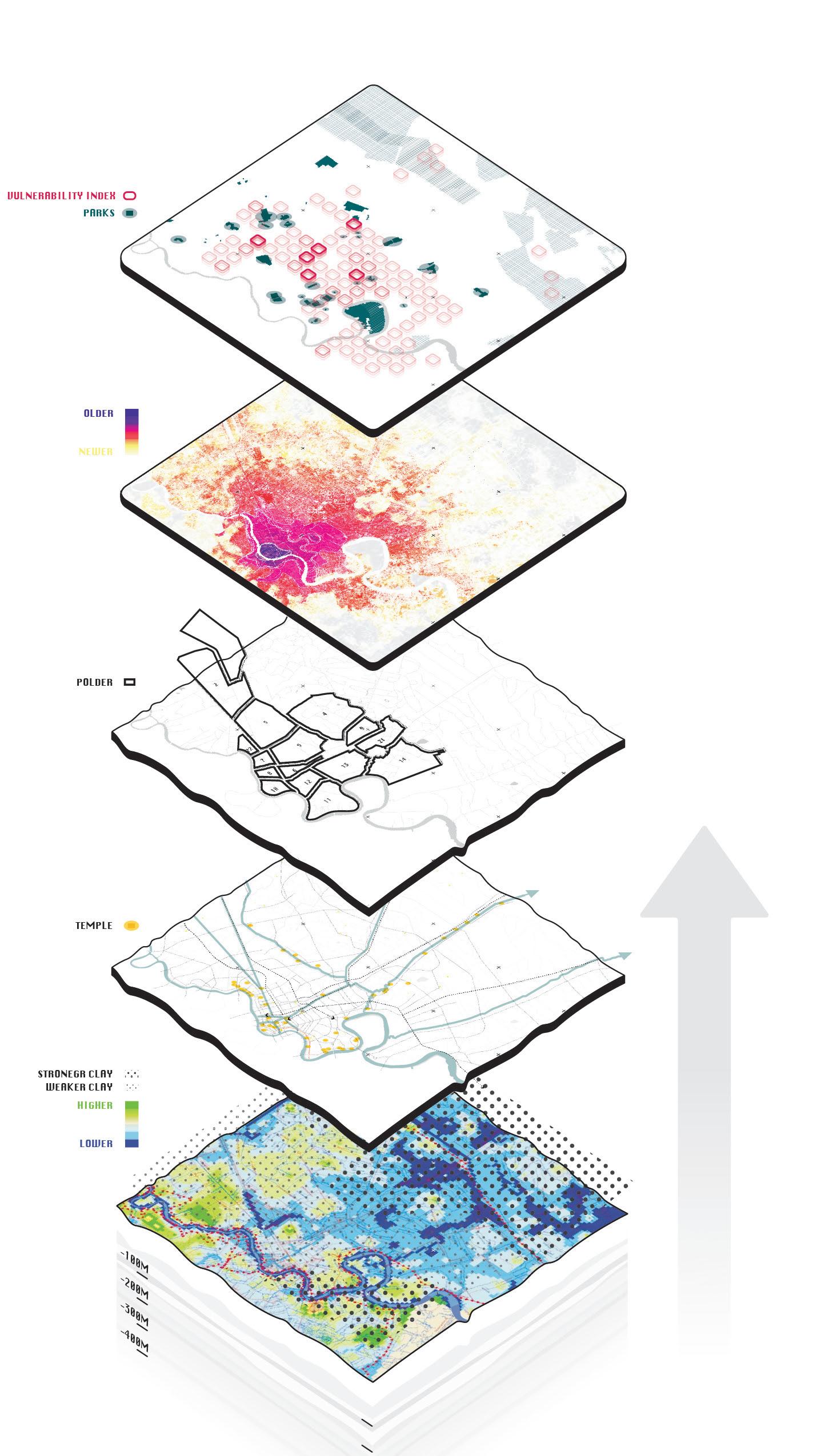

.9 Water-Soil Led Planning

DIALOGUES

THE MYTH OF MAE

PHRA KHANONG

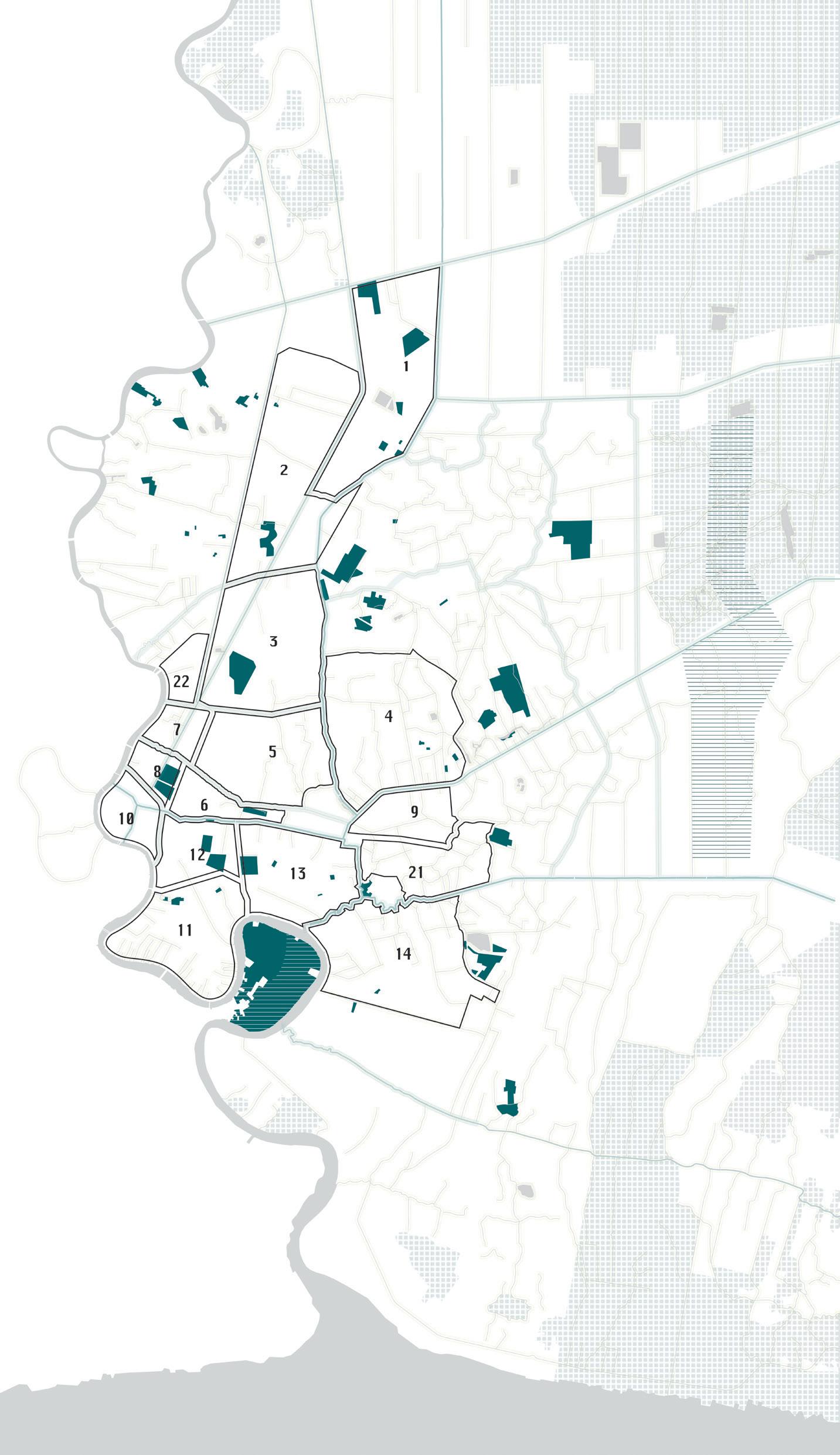

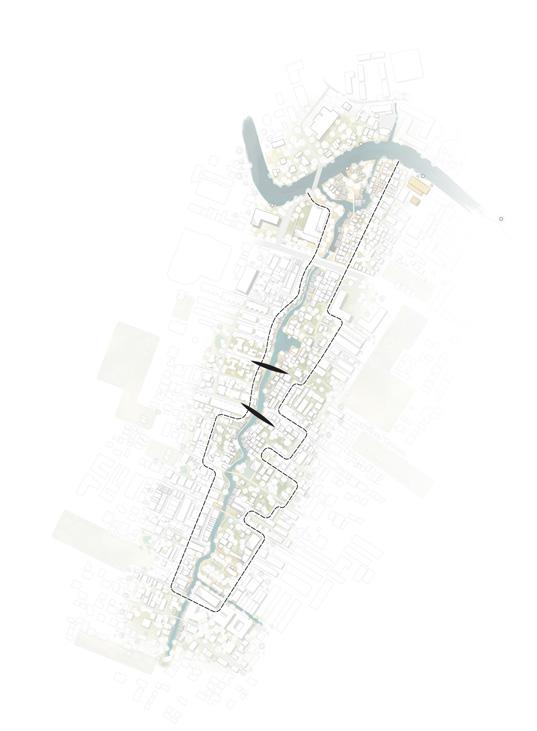

.1 Strategic framework

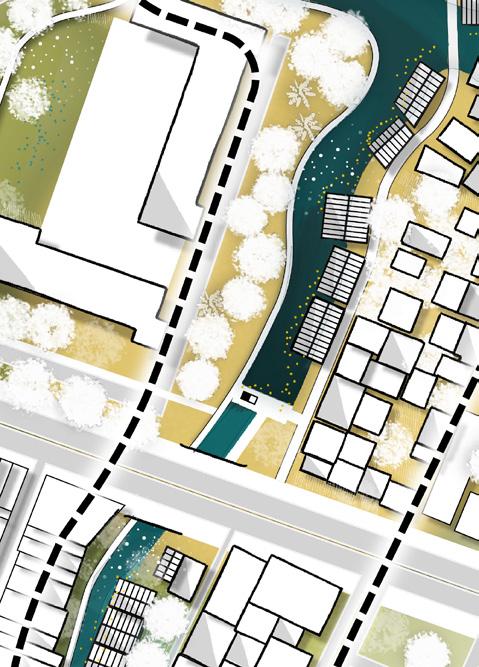

.2 Khlongside development

.3 The Site

5

.4 Wetland

.5 Field Log

.6 The Differences

.7 Beyond Rationality

.8 The Myth

METAMORPHOSIS

RE-ENCHANTING THE KHLONGS

.1 Landbased Lock-In

.2 Breakthroughs

.3 Key Actors

.4 Water Model

.5 Wetland

.6 Pocket

REFLECTIONS

STEPPING

FORWARD

.1 Conclusion

.2 Deconstruction

.3 Re-Enchantment

.4 Limitations of the Process

.5 Future Steps

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GLOSSARY

ORIGINS

Thailand is located within Southeast Asia’s heart, between the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. The country forms a hinge between the Indochinese mainland and the Malay Peninsula. Due to this strategic position, Thailand features a wide range of landscapes, from mountainous regions and dense tropical forests in the north to expansive lowlands and coastal deltas in the central and southern parts.

The Thai capital, Bangkok, is situated on the alluvial soils of the coastal delta. For the past 2.5 million years, the region has been shaped by a stable tropical climate characterized by three main seasons: wet, dry, and hot, largely driven by monsoon winds. This climatic stability, present since the early Pleistocene, has supported the development of fertile landscapes and water-based cultures across the region.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

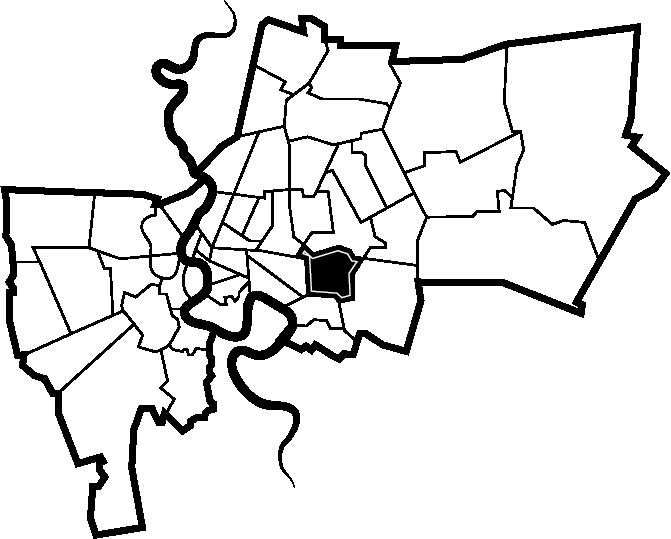

With over 16 million people Bangkok is a key urban center in Southeast Asia, with strong institutions, universities, and global exposure. However, it is also exceptionally vulnerable to environmental and infrastructural risks.

While Thailand’s overall climate risk ranking has improved, this national average obscures the specific, urgent reality for Bangkok. As a lowlying delta city, its vulnerability to extreme weather and rising seas remains acute.

Nevertheless Bangkok holds both the knowledge and potential to pioneer a resilient strategy for the densely populated Chao Phraya region, offering a proactive response to the tipping point it now confronts.

It is not uncommon for cities around the world to have emerged in deltas. In fact, only ten percent of the global population lives more than ten kilometers from a freshwater source. Yet water is increasingly perceived not as a foundation for prosperity, but as a threat manifesting through floods, droughts, and rising seas. Throughout history, water has not only sculpted the physical landscape, but has also shaped the cultures, economies, and rituals that have evolved around it.

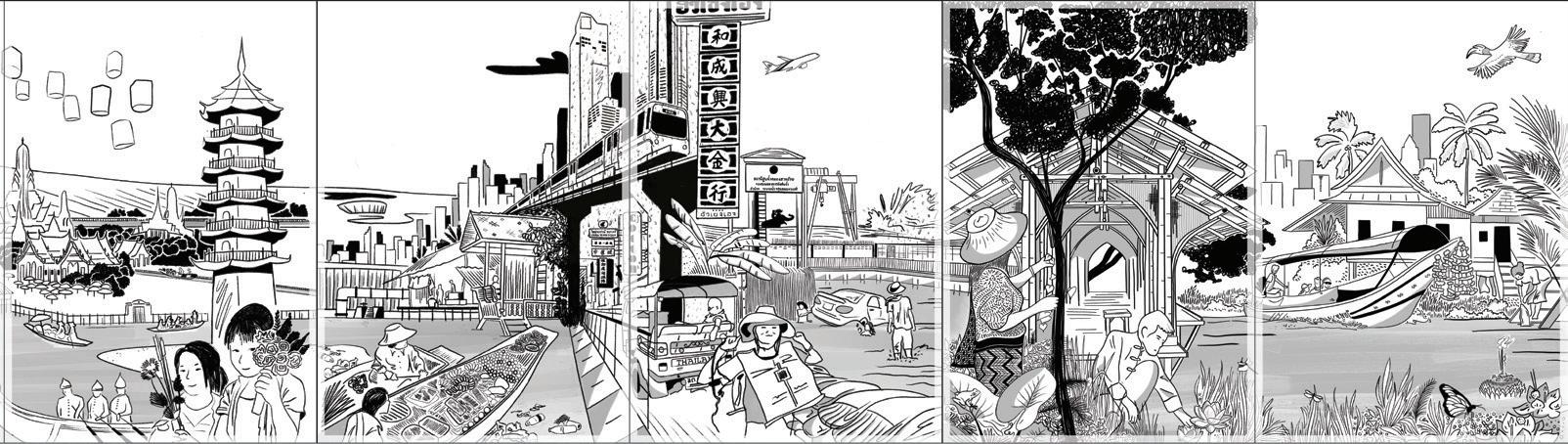

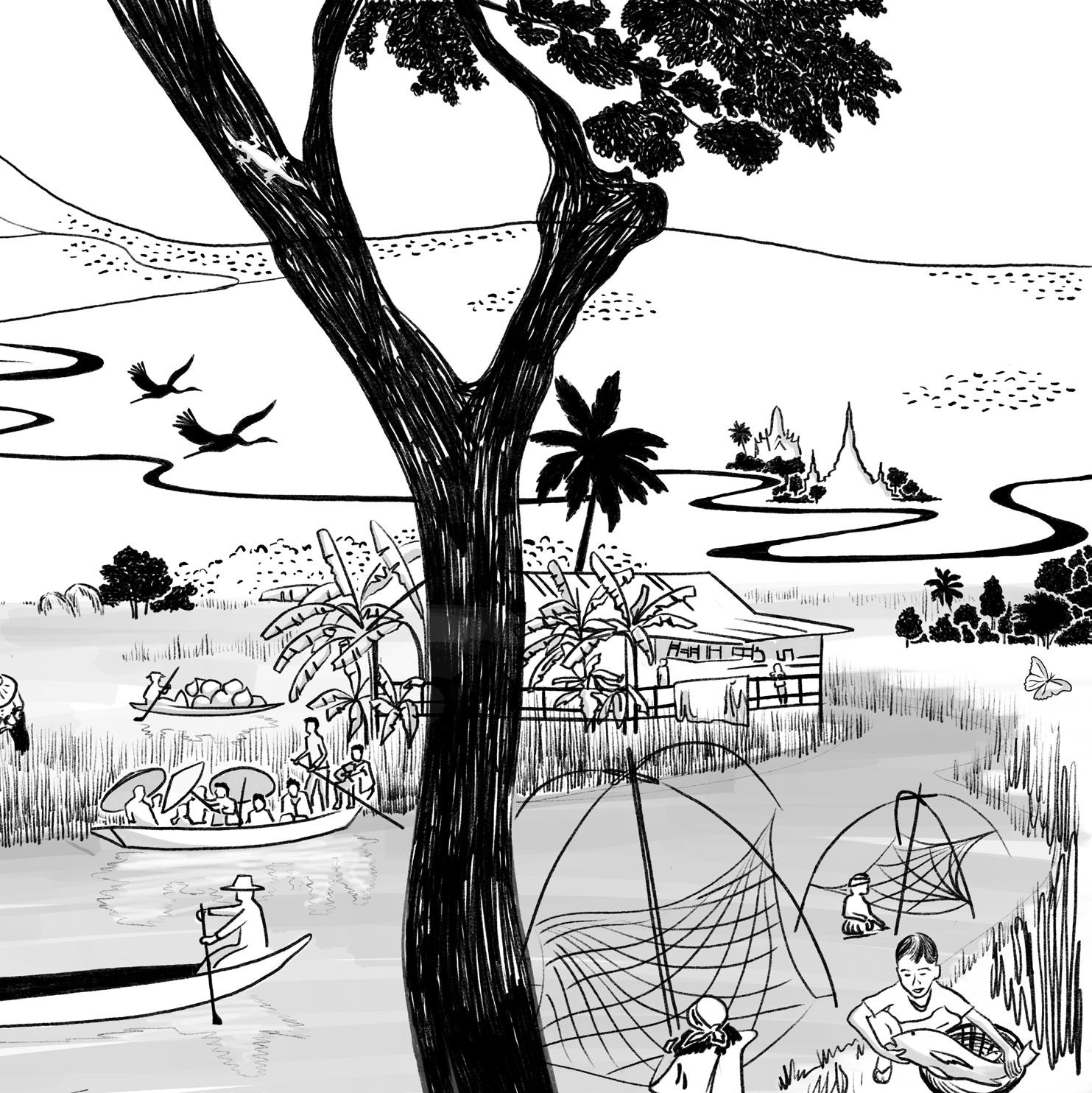

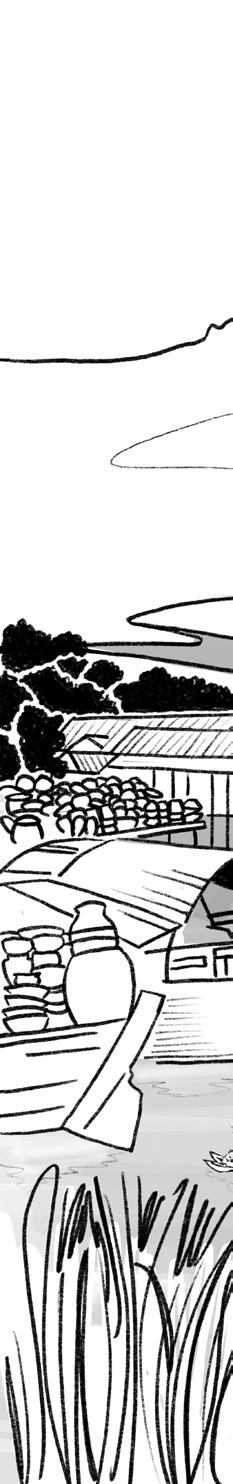

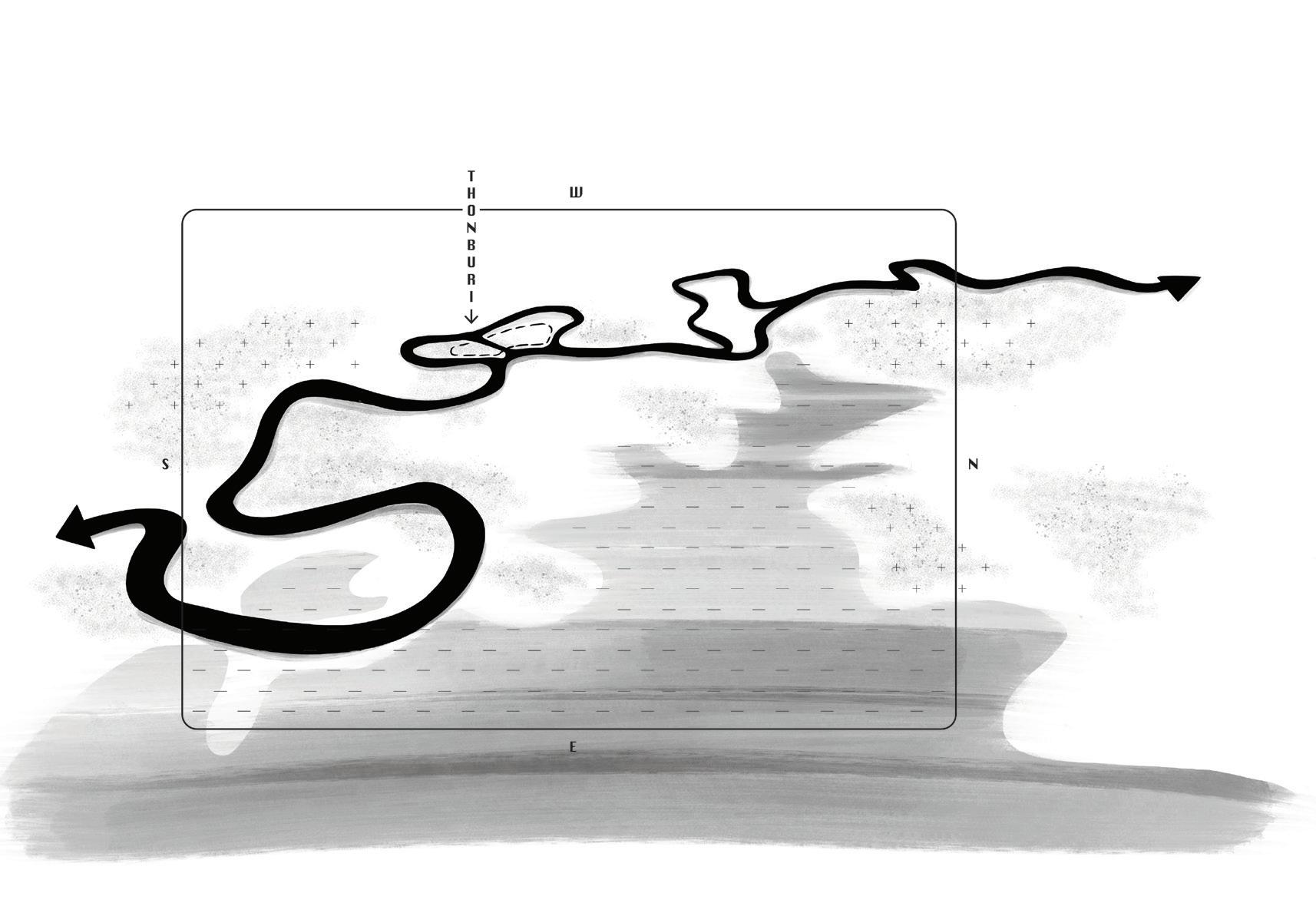

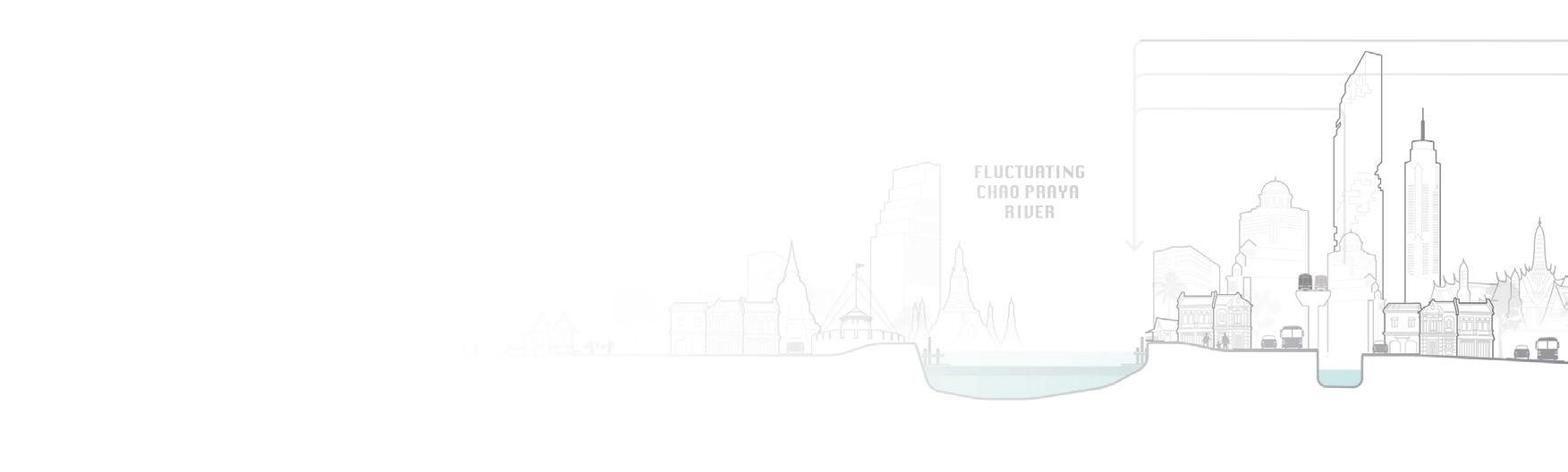

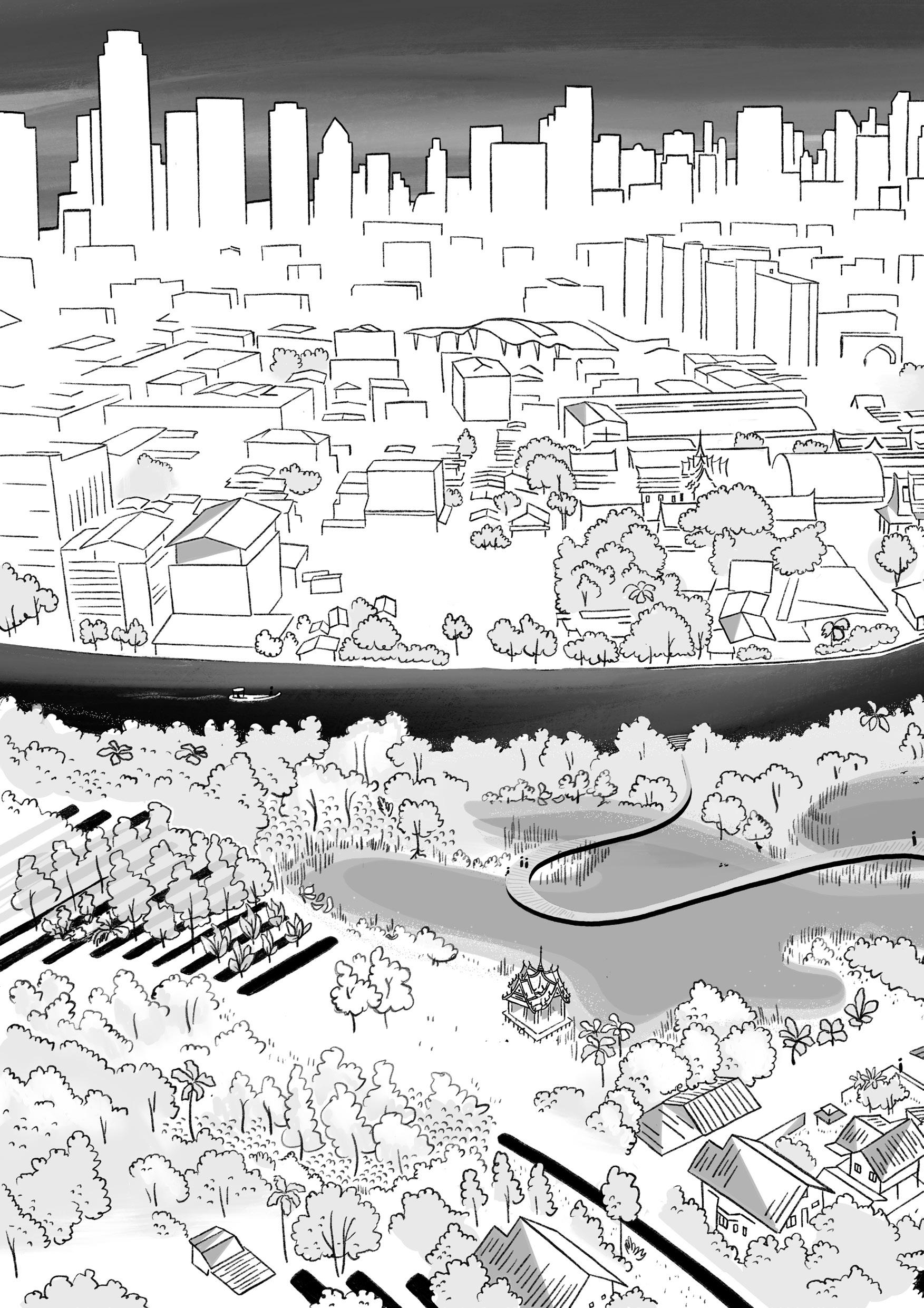

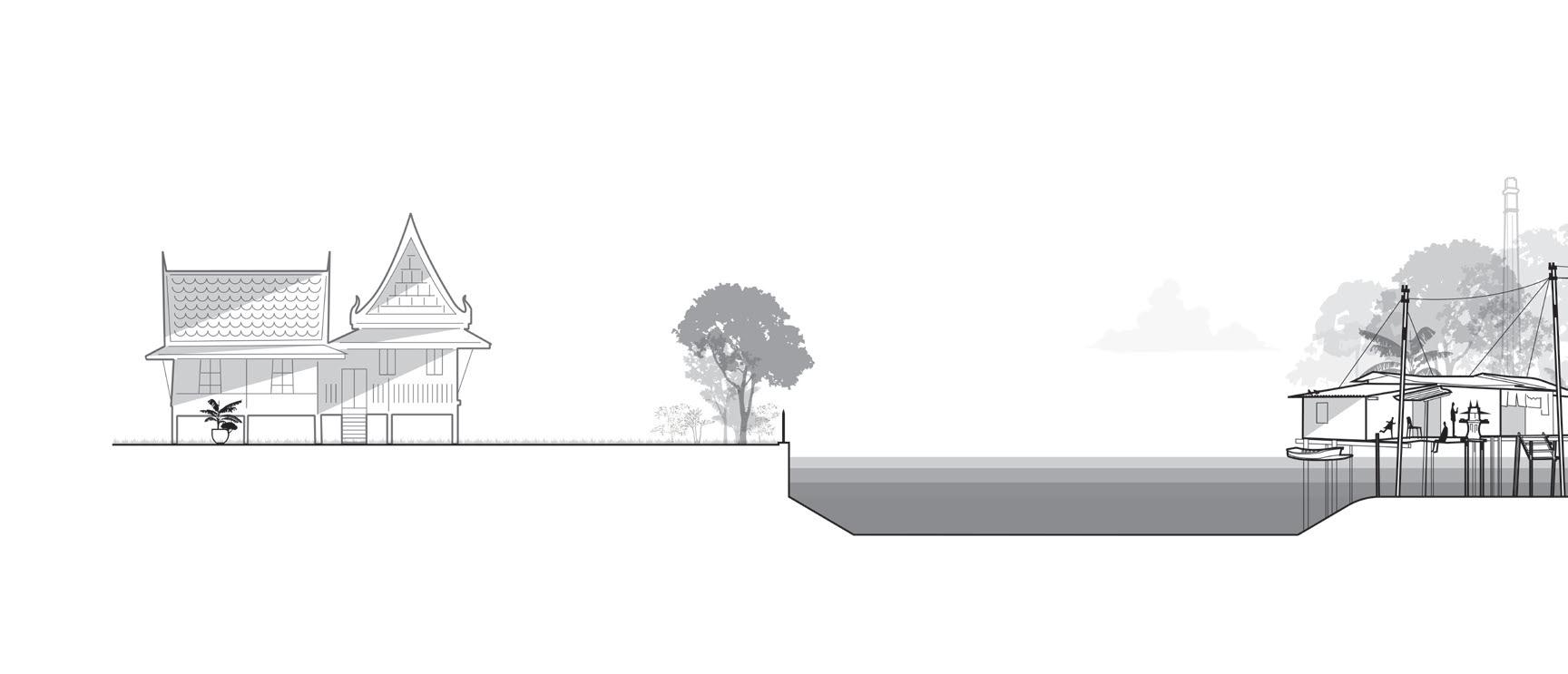

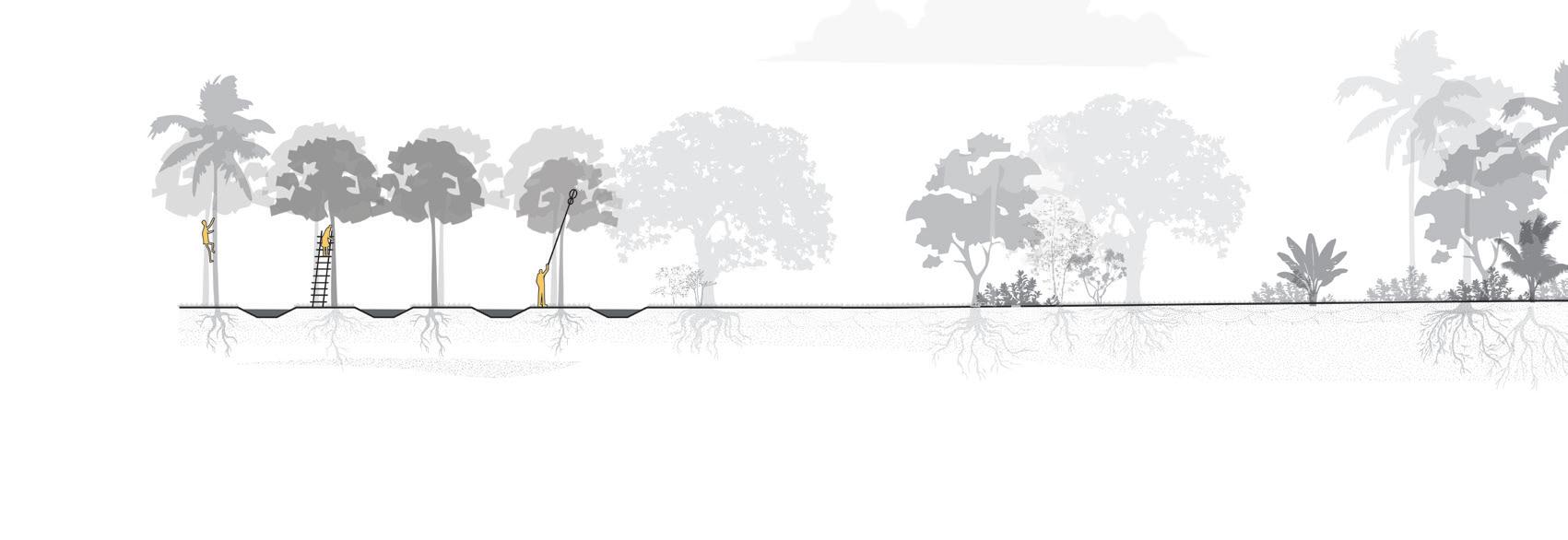

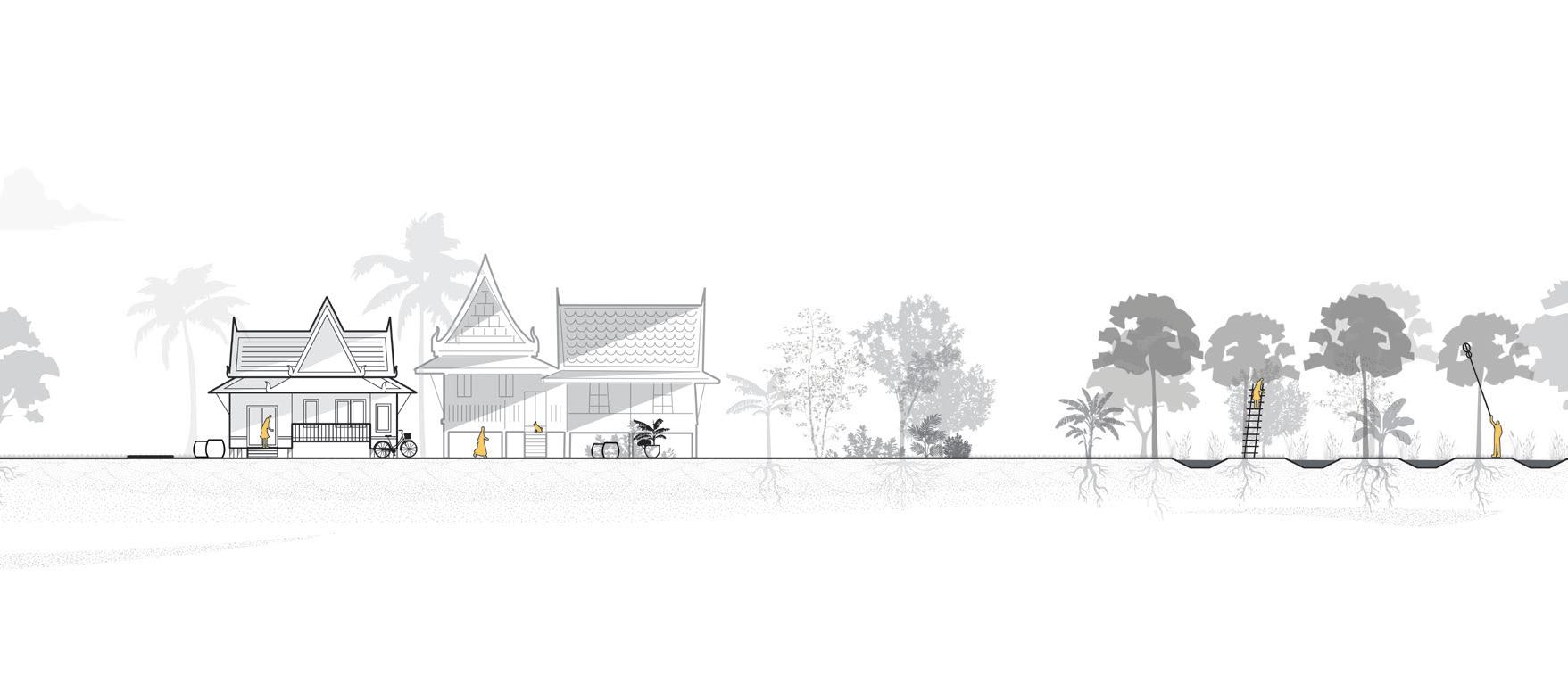

The panorama above offers a spatial and temporal overview of how humans have lived with the watery landscape of the Chao Phraya River catchment. From left to right, it descends from the mountainous headwaters through deltaic plains to the Gulf of Thailand. In parallel, it reveals how people adapted over time to Thailand’s amphibious terrain, developing techniques, rituals, and settlements that responded to seasonal rhythms and hydrological change.

BRUMMELHUIS, H. 2007

& PHONGPAICHIT 2014

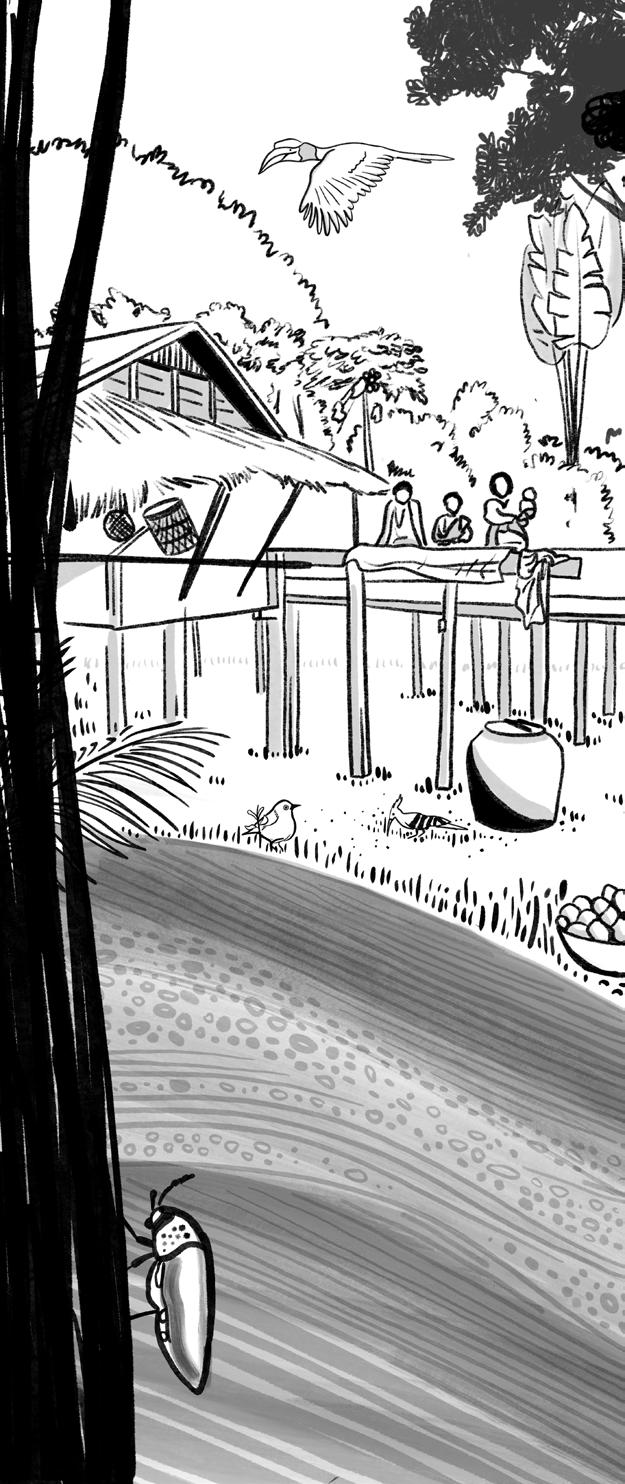

Early settlements emerged across Thailand around 500 CE, as Tai, Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, and Austronesian peoples migrated from different directions, bringing distinct knowledge systems and adapting to local water-based ecologies. Stilt houses safe from floods, wildlife, and heat remain a common feature across the country. The Tai, who settled around the 1st century, introduced rice cultivation and the region’s first land management practices, marking a period deeply attuned to environmental uncertainty.

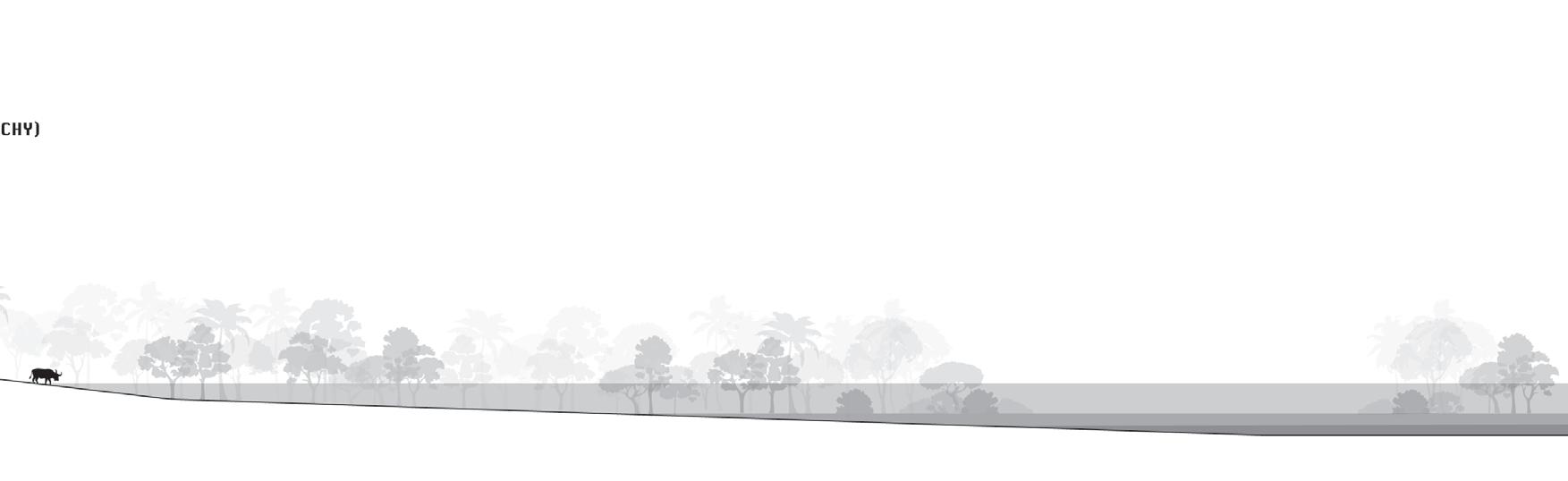

Further downstream into the perennially wet fluvial flats of the Chao Phraya delta, movement and transport were preferred by boat for centuries.

These conditions enabled rice cultivation for local consumption and supported fishing as a primary food source, with water buffalo assisting in small-scale agriculture. This reliance on water was central to the rise of the second historical moment: intra-Asian trade.

Driven by foreign demand, Ayutthaya flourished into a powerful trading hub connected to China, Persia, India, and beyond. Its growth and wealth was fundamentally underpinned by the fertile floodplains and strategic waterways. Consequently, many of Thailand’s enduring traditions and water rituals trace their roots to this prosperous period.

After fall of Ayutthaya the new capital Bangkok was founded closer to the coast, a relocation that established both the foundations for the city’s present wealth and the environmental vulnerabilities it faces today.

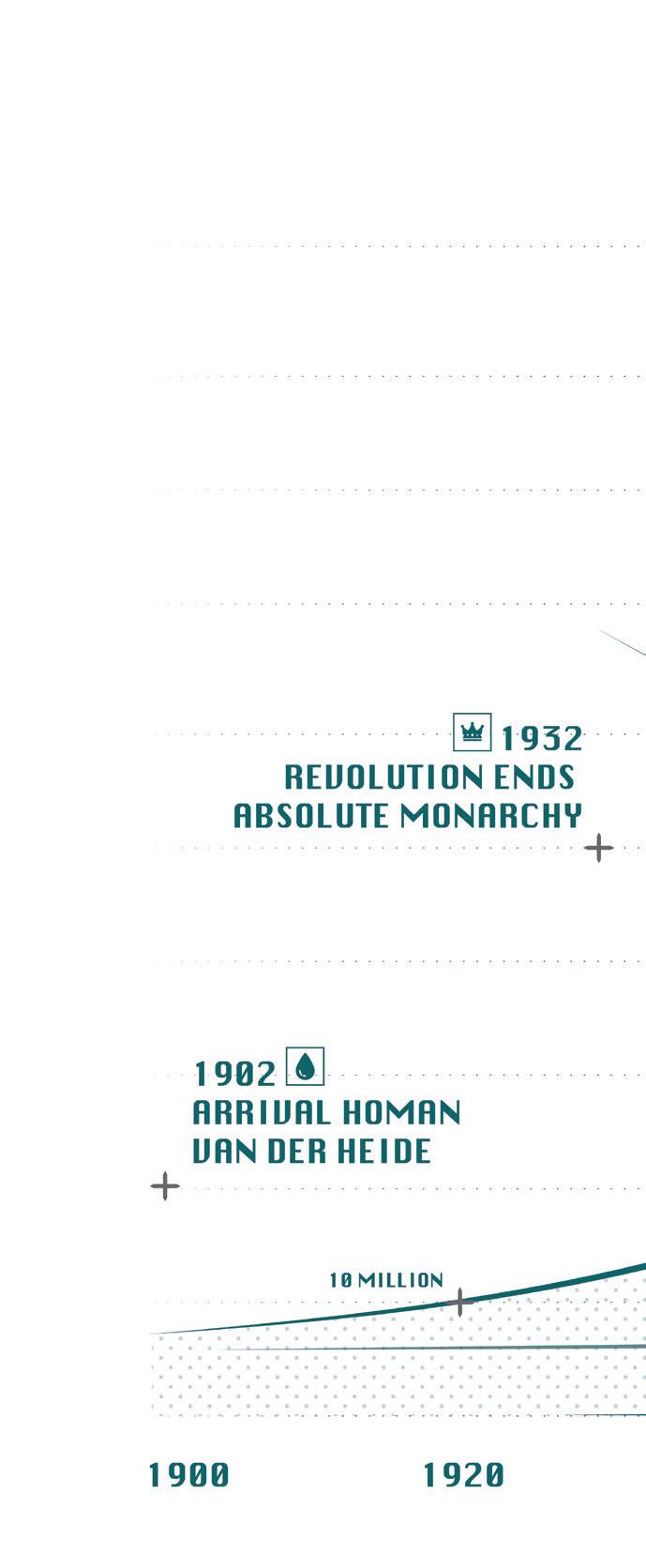

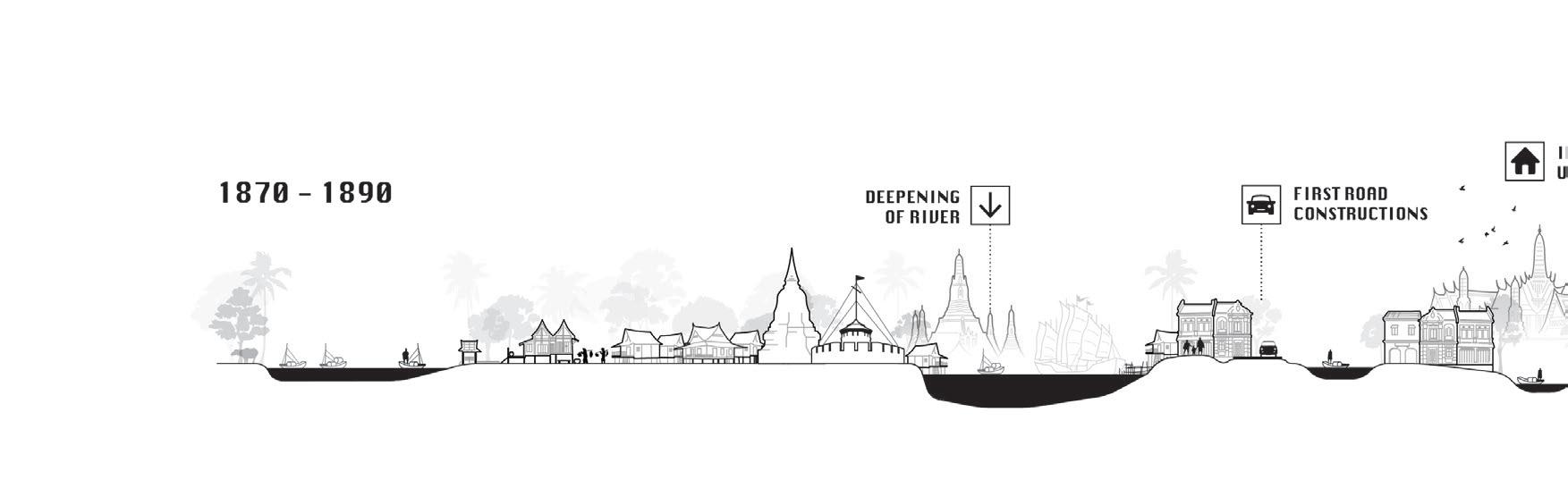

Pressured by British and French colonial interests Thailand, underwent a dramatic economic and political transition initiated by the 1855 Bowring Treaty, which dismantled royal trade monopolies and spurred modernization.

This era saw the rapid adoption of Western technologies, the abolition of slavery, and the swift urbanization of Bangkok. With the first modern road commisioned by westerners in 1864 Thailand has become increasingly land-based. After World War II the intensified US presence within the region grew Bangkok into both a military stronghold and a tourist magnet, embracing fossil-fueled, capitalist expansion.

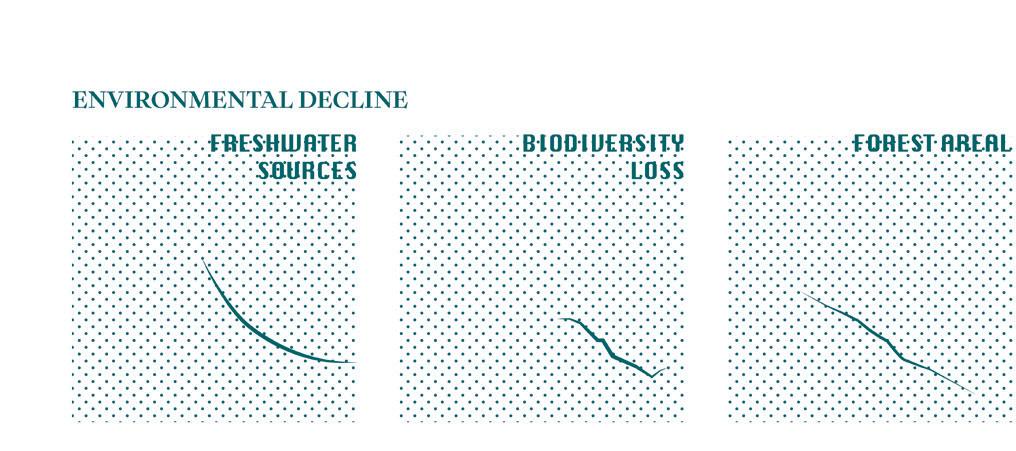

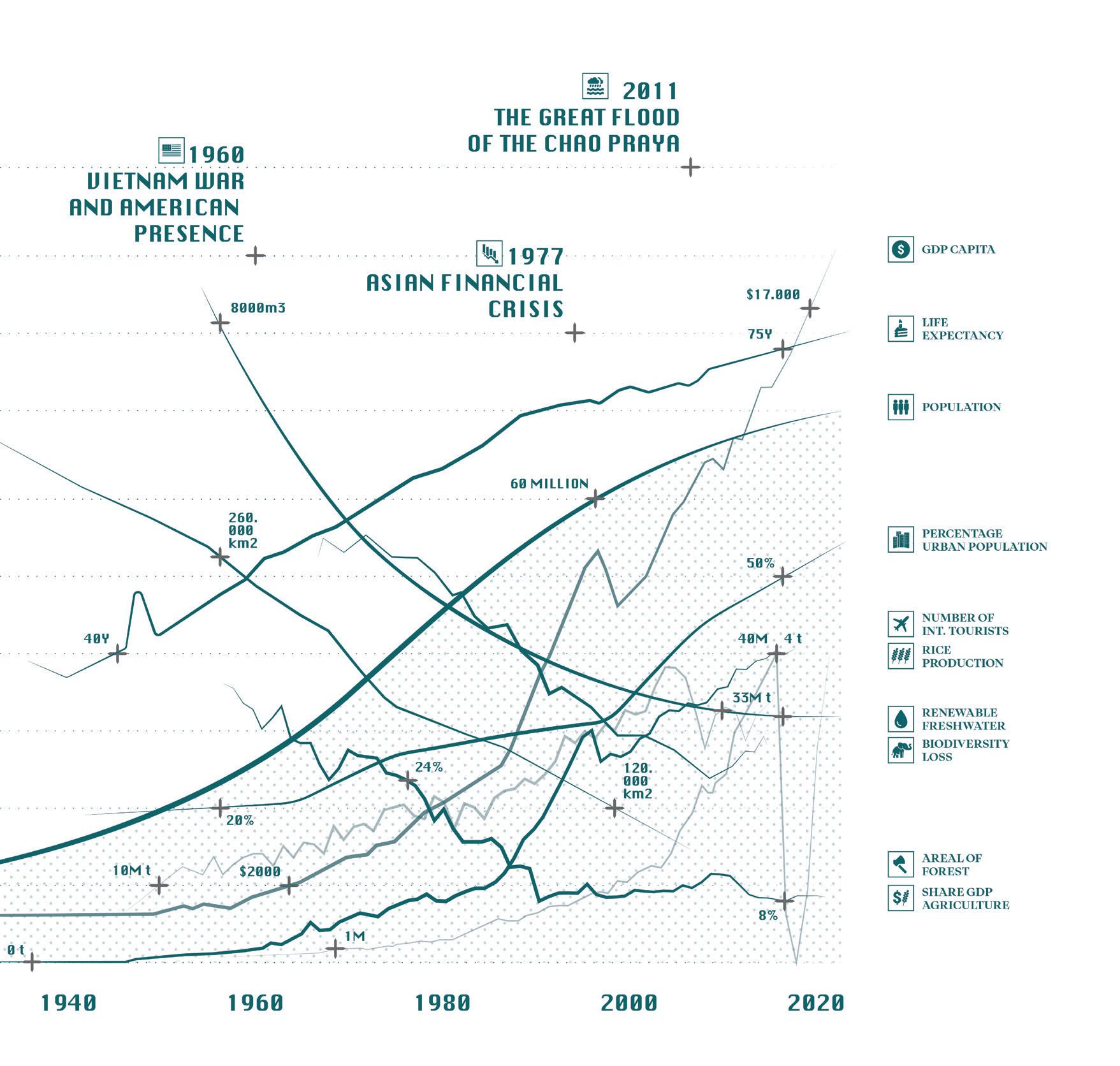

Viewing Thai history through the lens of water reveals a dynamic tension: while the past century brought immense growth—life expectancy nearly doubled, GDP soared, and the population grew from 10 to 70 million as the country shifted from agrarian to manufacturing.

This progress incurred a steep ecological cost. Health and income improved at the expense of natural systems, resulting in increasingly strained freshwater sources, loss of forest cover, and declining biodiversity, mirroring global trends toward a potential sixth mass extinction. This trajectory raises urgent questions about the sustainability of the current growth model.

As we face the current climate and biodiversity crises, alongside the acknowledged flaws of technological solutions, examining our historical relationship with water becomes essential. By looking through the lens of water, this analysis traces how human perceptions and uses have shifted, offering a detailed framework for understanding hydro-societal interactions. These shifts, which loosely align with key historical tipping points, provide crucial building blocks for formulating a resilient relationship with water moving forward.

“

To explore relationships between people, place, and water, I introduce the term :

Following pages introduce an overview of different geo-choreographies within the five perceptions of water described.

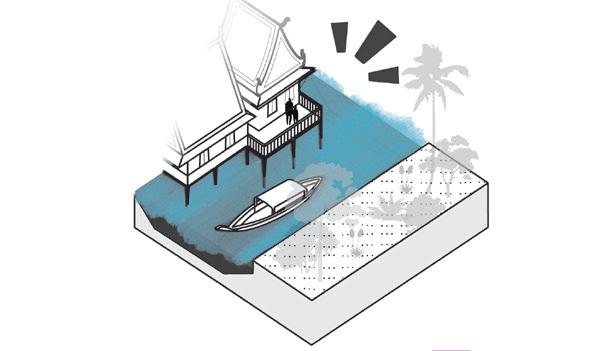

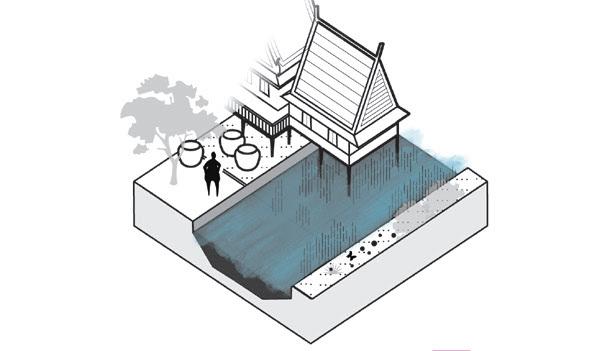

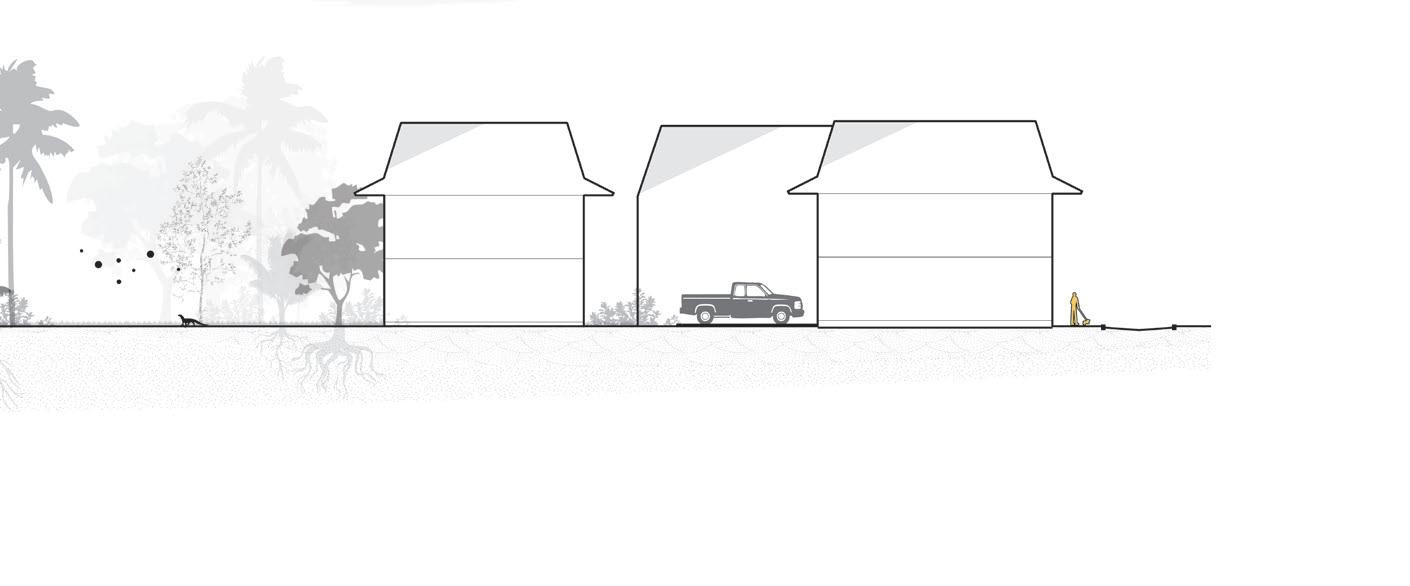

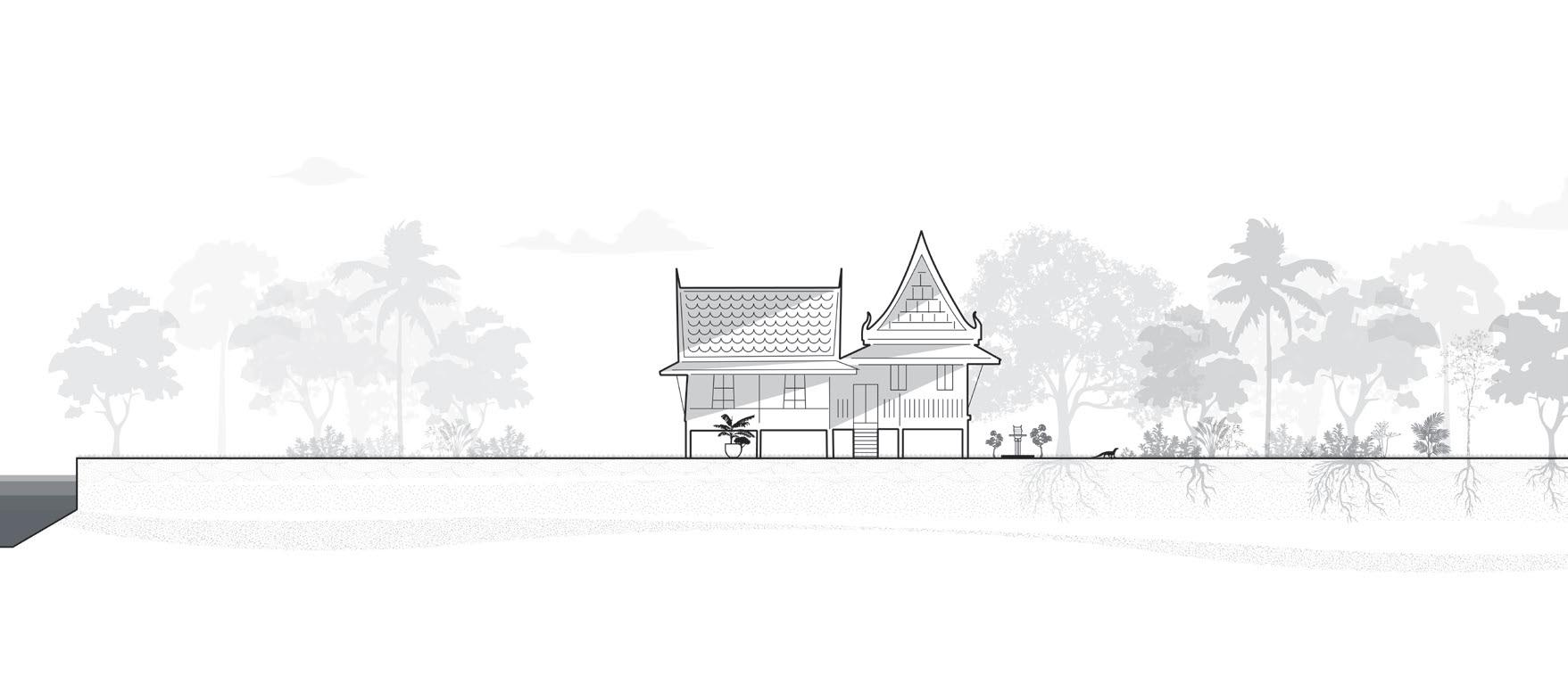

Traditional Thai Architecture is not longer the common mode of living in Thailand. It has either become object of privilaged consumerism for tourists, or protected as cultural heritage disposed of its intended use. Nevertheless its vernacular is fundamental to adaptive living in the wet delta of Chao Praya.

Naturally a wide variation exists between LO-TEK applications more often seen in lesser economically developed neighboring countries such a Myanmar, and more celebrated architecture seen in expensive houses on stilts.

Throughout the country the Thai live in houses raised on stilts. It is a traditional architecture that is increasingly dissappearing as architecture evolves.

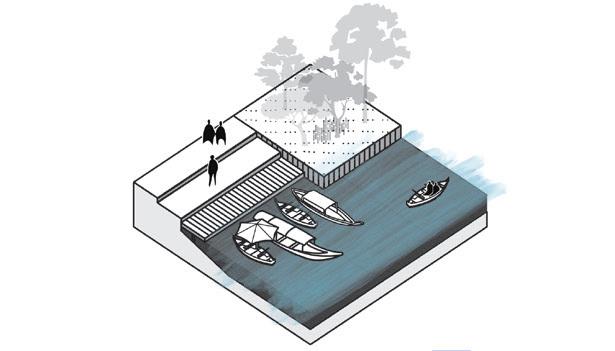

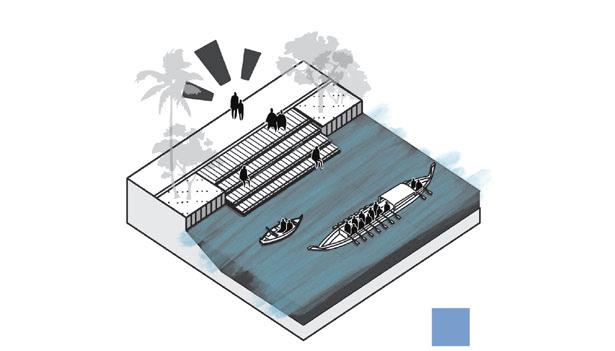

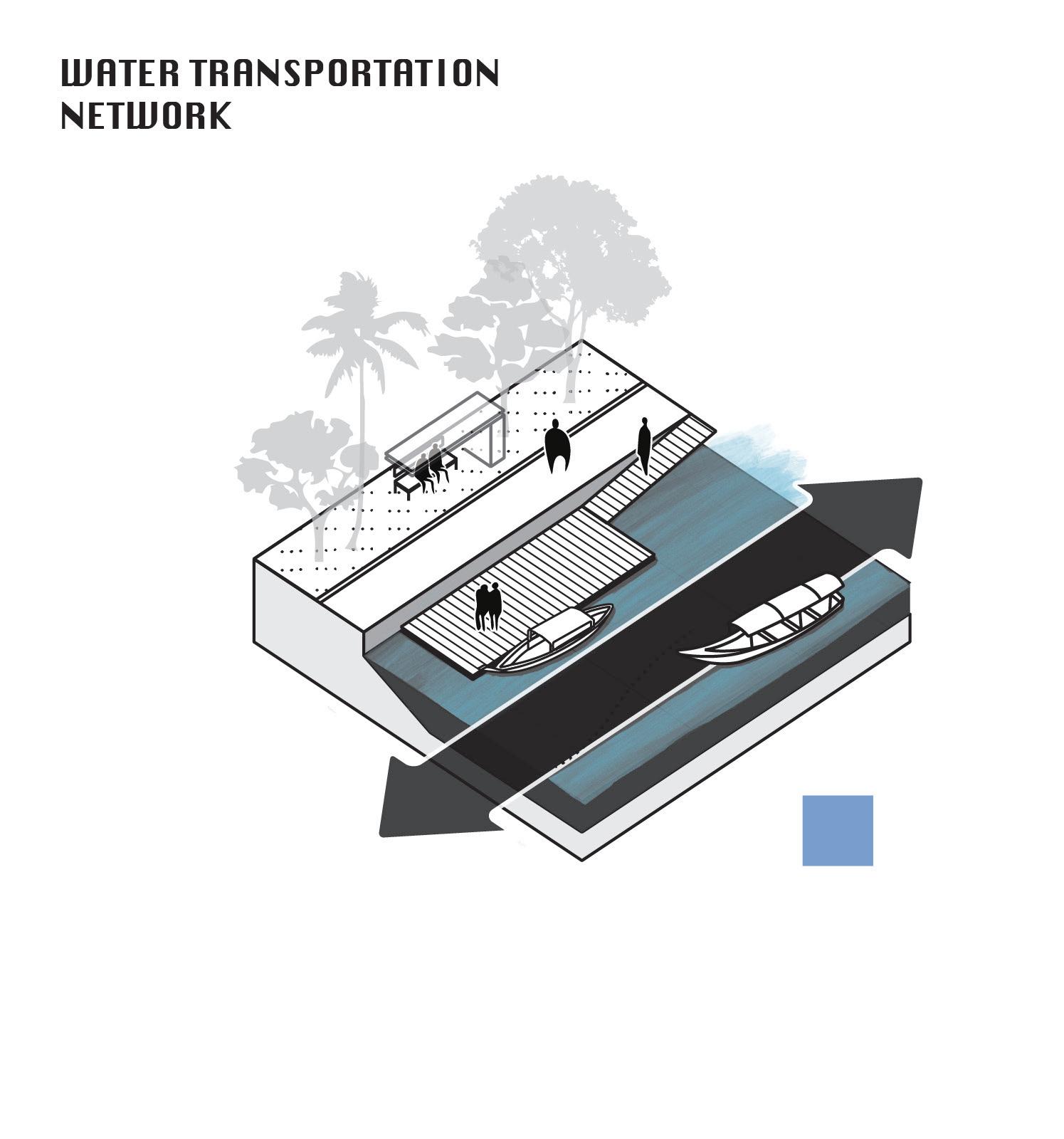

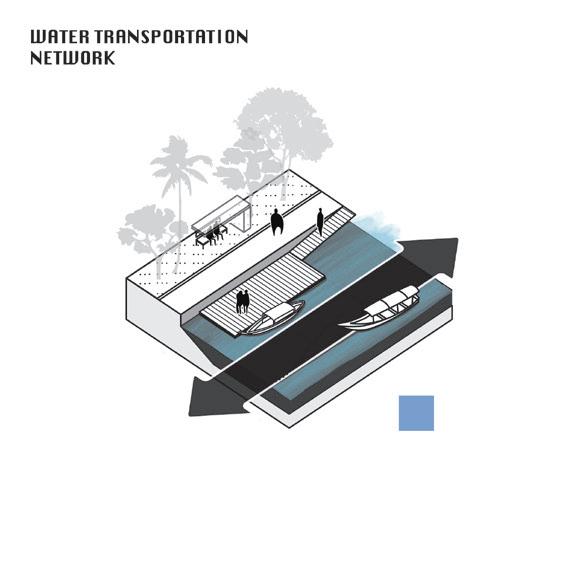

Waterways once enabled transportation and trade, allowing societies to expand beyond local boundaries. Rivers, canals, and coastal routes formed vital infrastructure for regional and international exchange, carrying goods, people, and ideas.

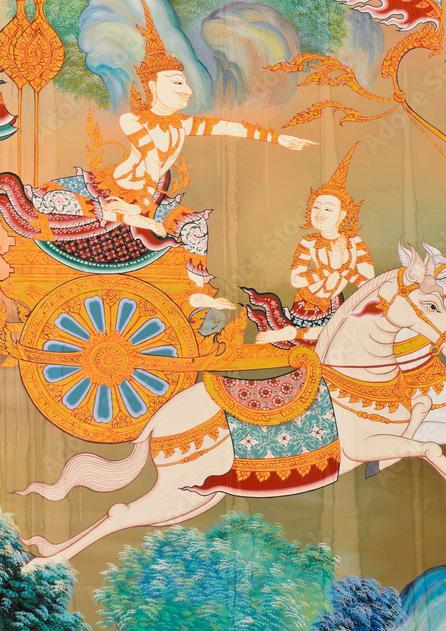

During the Rattanakosin period, canals became central to urban mobility in Bangkok—just as Ayutthaya before it earned the title “Venice of the East.”

This legacy remains visible today: traditional vessels still animate the landscape, from everyday ruea hang yao (long-tail boats) and ruea phrae (cargo barges) to ruea pramong (fishing trawlers) and the ornate ruea thong used in royal processions. Although modern infrastructure has replaced many traditional uses, Thailand’s enduring boat culture continues to shape its relationship with water.

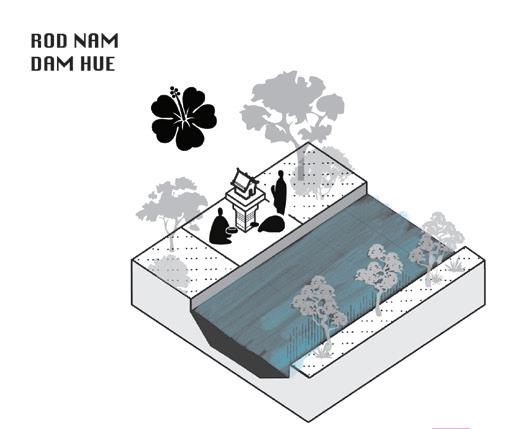

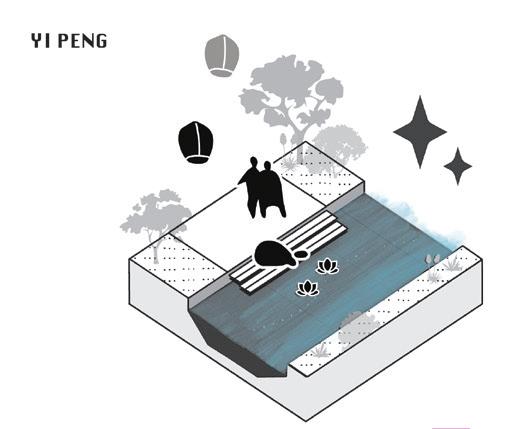

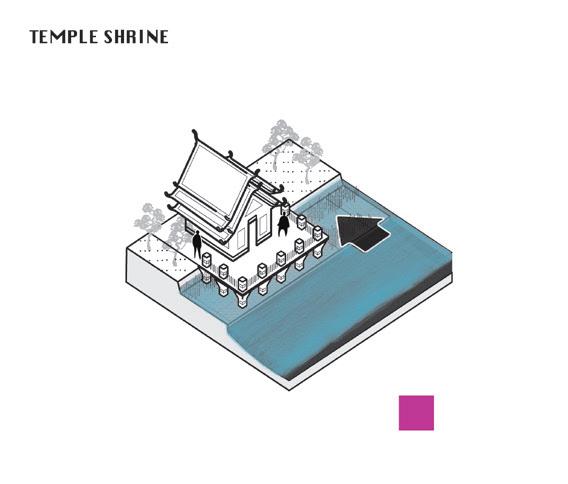

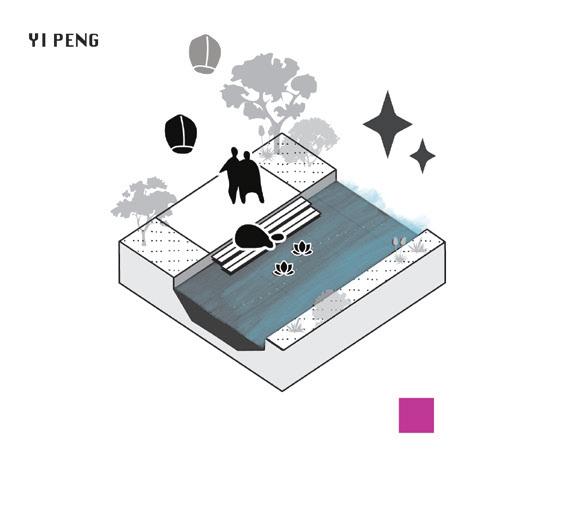

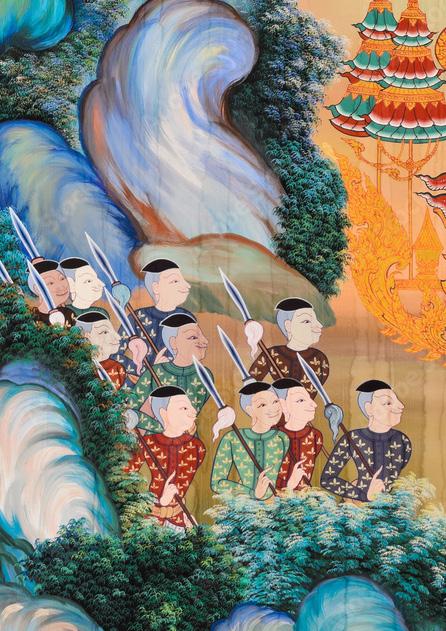

Seasonal and everyday rituals reveal Thailand’s deep cultural intimacy with water. During Songkran, the Thai New Year in April, water is poured as a symbol of renewal; in more intimate acts, people sprinkle water on Buddha images to make merit or release candlelit krathong floats during Loy Krathong to let go of misfortunes and honor the water spirits. Such practices embody a lived entwinement with the environment where water signifies purification, connection, and continuity.

As communities and power structures evolved, water also acquired profound symbolic and sacred significance, becoming central to rituals, cosmologies, and state ceremonies that shaped Thailand’s social and spiritual fabric. Thai religiosity, shaped by the coexistence of Theravāda Buddhism and animist traditions, remains visible in everyday landscapes through spirit houses and sacred trees.

As agriculture expanded and connected to global markets, water became a key driver of economic growth. Environmental conditions and specific demands from regional powers like China defined the type of crops cultivated, characterized by expansive rice fields across the lower Chao Phraya delta.

This transformation turned subsistence farming into a commodified, exportoriented sector, making Thailand the world’s largest rice exporter and profoundly influencing the Thai kitchen (e.g., the use of hot chilies to contrast plain rice). This shift brought significant wealth but also deepened inequalities in access to land and water. Within Bangkok, however, planting is characterized by smaller family orchards throughout the city, focusing on fruits and vegetables rather than dominant export crops.

The rise of hydraulic engineering, enabled by the accumulation of capital and knowledge, led to water being increasingly viewed as a resource to be controlled, regulated, and extracted. This resulted in megastructures like dams and drainage systems that reshaped landscapes to serve urban and industrial needs.

While the Chao Phraya basin historically developed a rich, adaptive watery heritage, the pressures of global capitalism drove cities like Bangkok toward a rigid modernization in pursuit of stability. Over the past seventyfive years, these transformations have eroded traditional relationships with the landscape, replacing them with the engineered, mechanical systems that still define Thailand’s built environment.

This chapter deconstructs the watermachine that Bangkok has become dependent on, and articulates its hydro-urban challenges

A timespan of not more than sixty years divides the two images to the left.

My mother moved to Bangkok during the post-war urbanization wave of the 1970s. She, along with her five sisters and their mother, my grandma, began working in Bangkok. Some of their memories still carry traces of this watery past.

Within one generation however, the deep, lively connection to the amphibious past has become a distant memory.

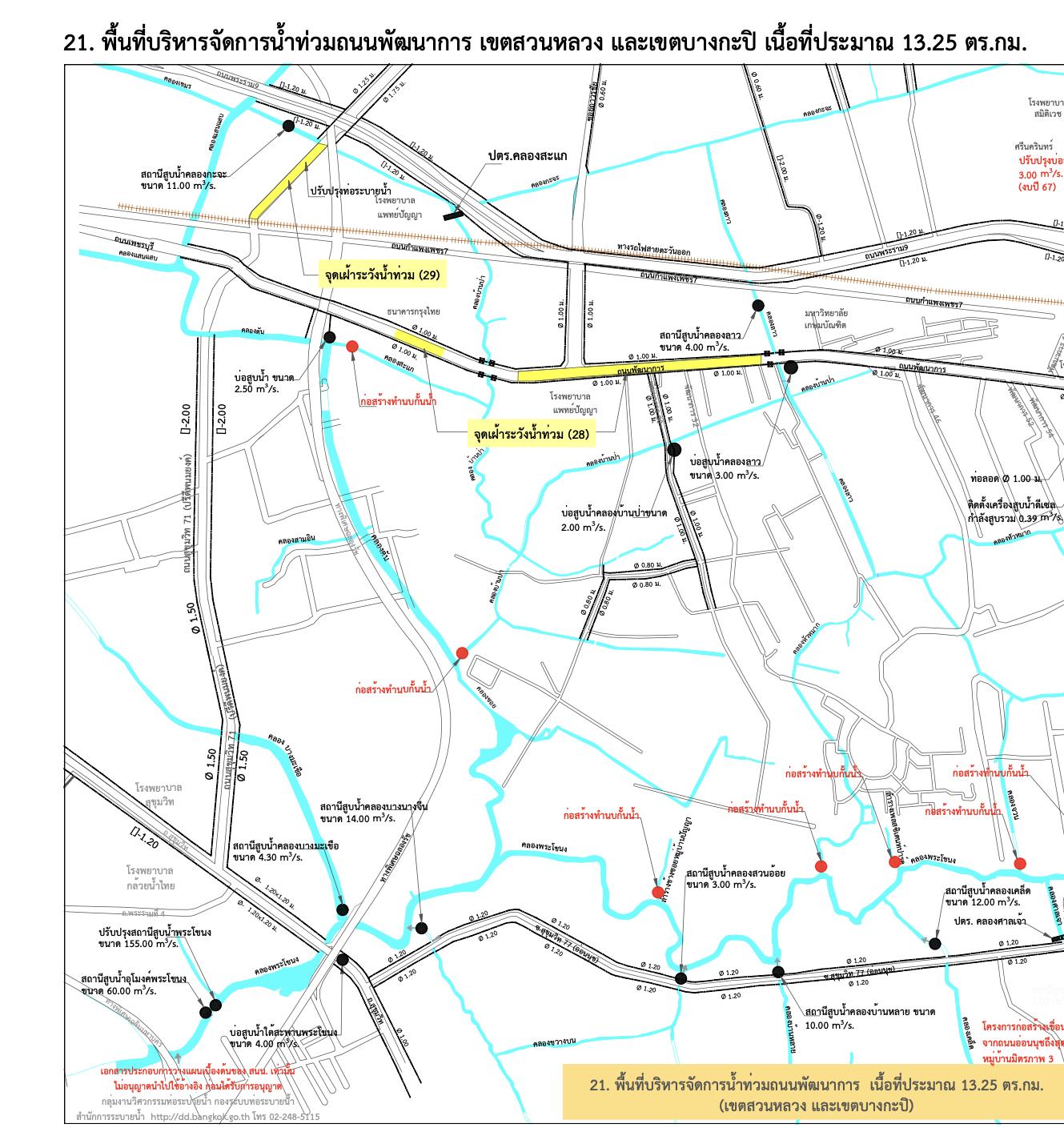

Today, my mother’s sisters and my grandmother fear the return of major floods. Living between the rural landscapes of Lop Buri, the former capital Ayutthaya, and the northern suburbs of Bangkok, were all affected by the devastating 2011 floods. The aftermath of this compound event became a turning point in Thailand’s contemporary approach to water management. The map to the right shows the affected areas of the flooding.

While historically, extensive rice fields could accommodate and buffer seasonal inundations, the 2011 floods revealed how current urbanization patterns marked by industrial zones and sprawling residential developments amplified the damage. Notably, both car manufacturers and individual car owners suffered significant losses, highlighting the vulnerability of economic assets in low-lying areas.

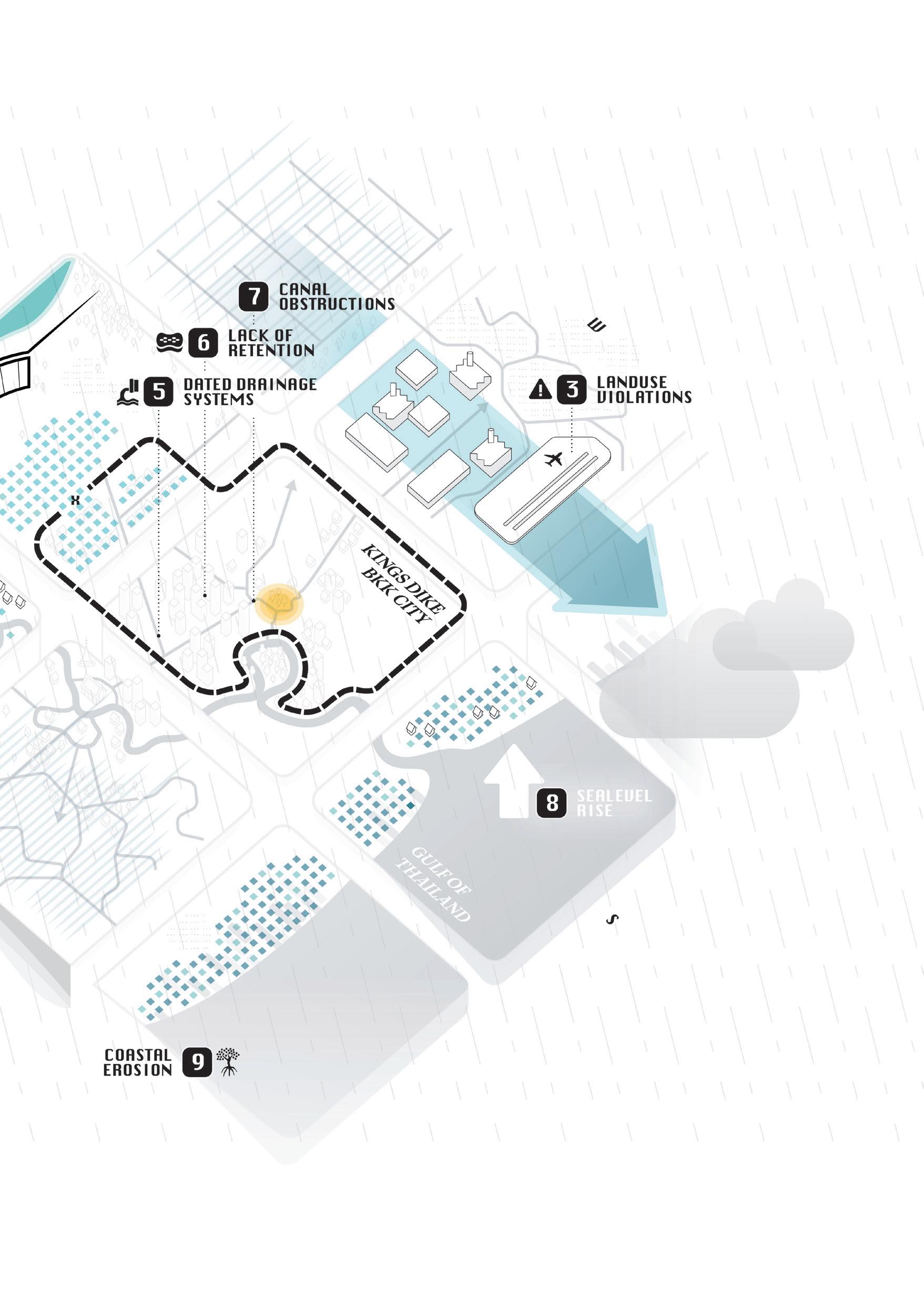

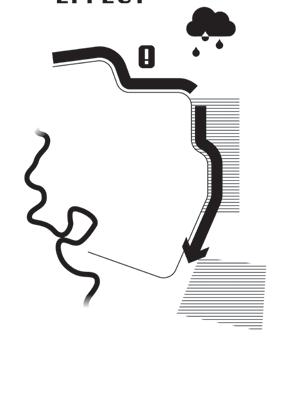

The flat terrain of the Chao Phraya Delta makes it highly susceptible to flooding. In the past, a dense network of natural streams provided surface drainage.

Increasingly unpredictable rainfall patterns and heavy cloudbursts make for high peak discharges which require adequate drainage flowrates or sufficient retention area.

Bangkok’s planning regulations designate flood zones around the city and along the Chao Phraya River, yet weak enforcement and financial incentives for industrial estates often lead to their violation.

Although groundwater exctractions are regulated and land subsidence is declining from 5-10cm a year, Bangkok still experiences 1-2cm subsidence a year

Deferred maintenance and investment into pumping systems leave space to improve the drainage systems of Bangkok.

Rapid urbanisation has significantly diminished the capacity of Bangkok’s soils to absorb and retain water. The shortage of parks and other permeable surfaces illustrates this lack of infiltration.

Informal construction and the accumulation of solid waste have significantly diminished the drainage capacity of Bangkok’s canal network.

The expansion of aquaculture and the construction of concrete coastal defences have degraded the mangrove forests that once served as natural buffers. In combination with rising sea levels, this exacerbates coastal hazards and accelerates salinisation and groundwater depletion inland.

The surrounding images illustrate this shift:

“FROM

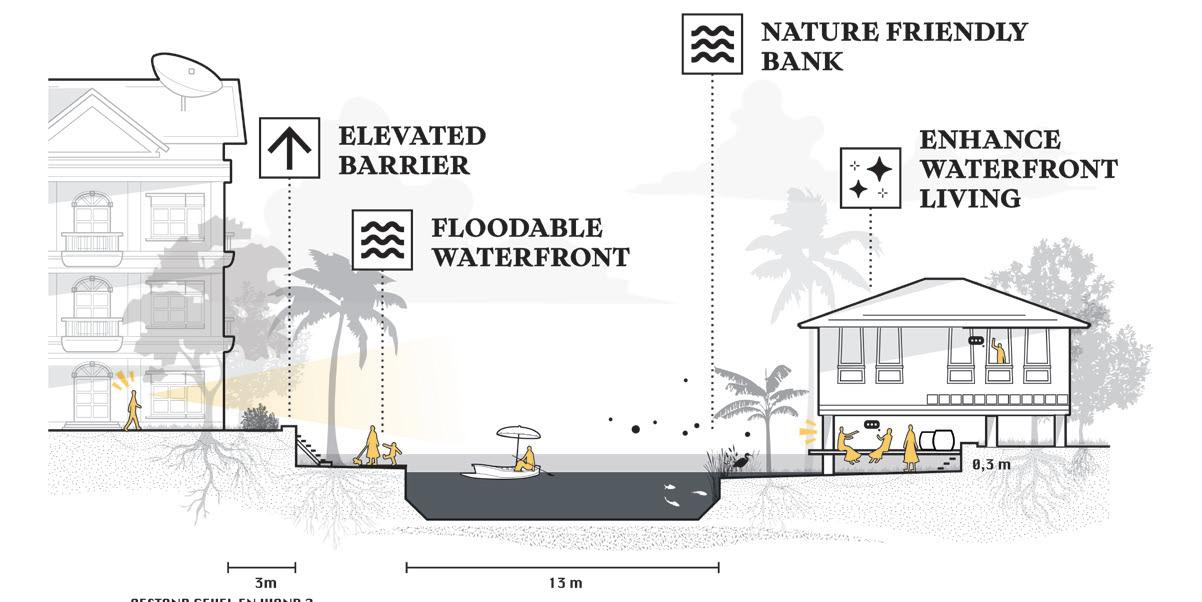

While the previous chapter described diverse geo-choreographies that embraced water as part of daily life and cultural identity, the aftermath of 2011 accelerated a paradigm shift toward land-based, risk-averse development. This turn prioritizes flood prevention and economic protection often at the expense of socio-cultural and ecological resilience. These defensive strategies, framed as safeguards, have largely benefited foreign investors and elite enclaves, frequently supported by public subsidies. Meanwhile, Bangkok’s broader population long accustomed to periodic flooding faces growing precarity. The largescale infrastructural responses reinforce a selective desire to remain dry, deepening spatial inequalities and eroding the city’s potential as an amphibious and inclusive landscape.

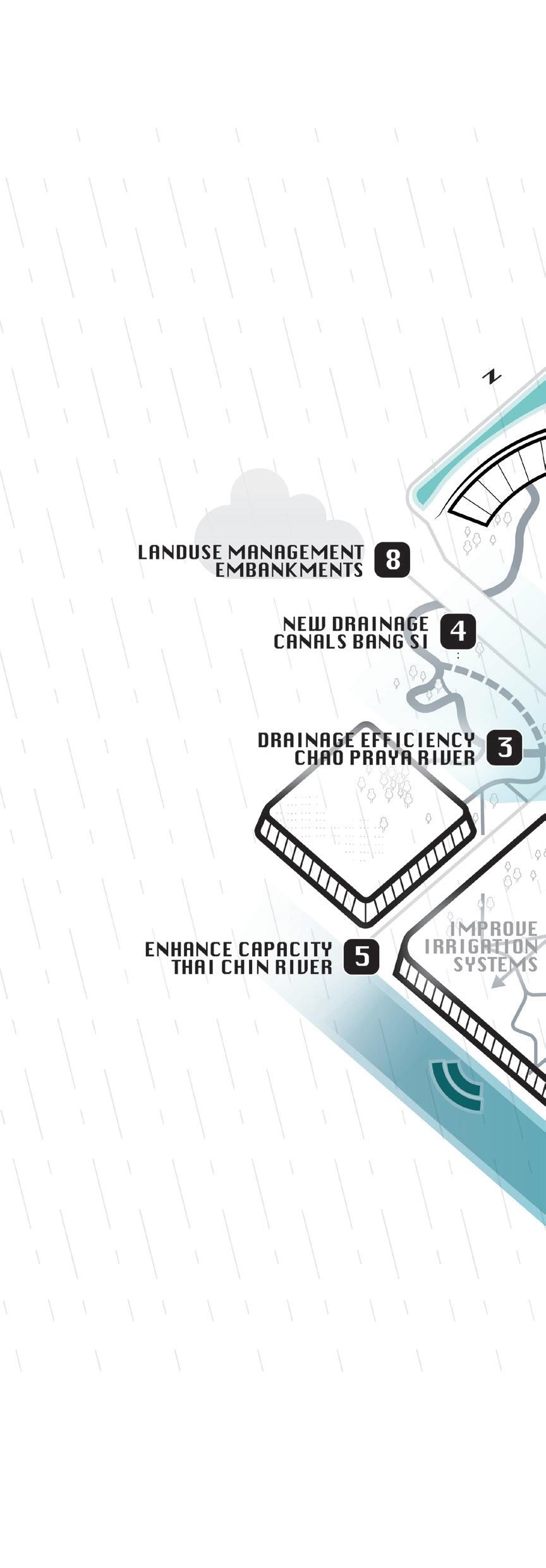

This approach of defensive strategies prioritised by the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) and political agendas are classified as water-resist and discharge measures, such as the elevation of dikes and enhancement of drainage infrastructure.

Meanwhile, strategies embracing the watery context that focus on delaying and storing water remain largely underutilised, despite their potential to yield multifunctional benefits for microclimate, spatial quality, and ecological systems.

BANGKOK

JEROME WITHINGTON IN HIS ARTICLE

BANGKOK’S NEW CITY OF WALLS

DATA SOURCE: TEBAKARI, T. 2020

The floods of 2011 not only exposed the stark divide between urban and rural areas, but also revealed deep inequalities within Bangkok’s urban fabric itself. The prevailing water management strategy centered on resist and discharge has since reinforced these disparities, prioritising protection of high-value urban zones while increasing vulnerability elsewhere.

In contrast, delay and storage strategies offer opportunities to address these inequalities by redistributing benefits and risks more equitably across the city.

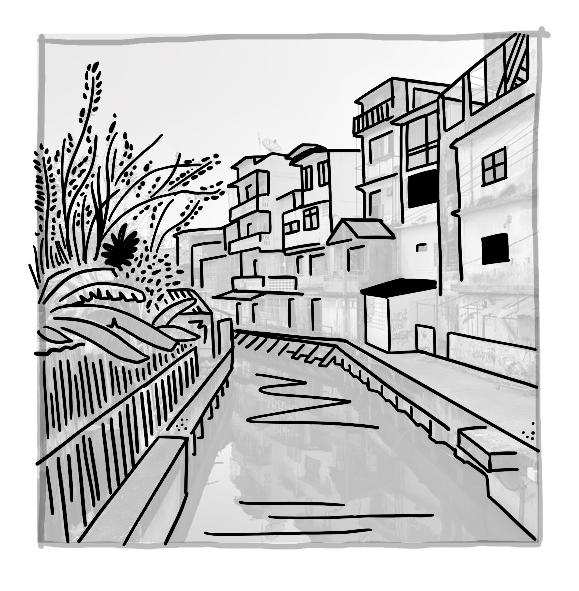

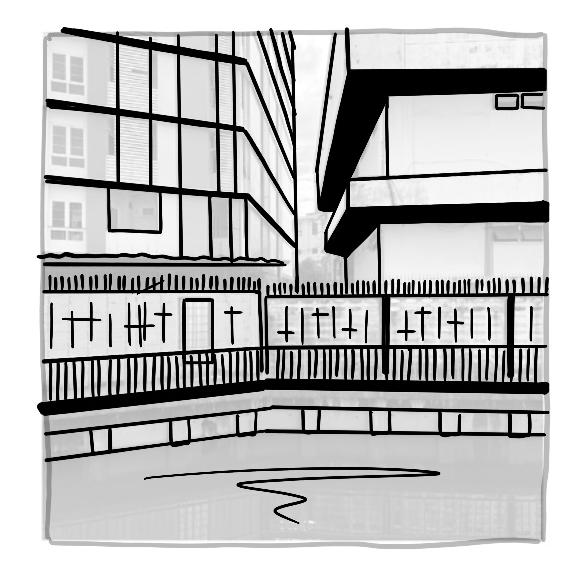

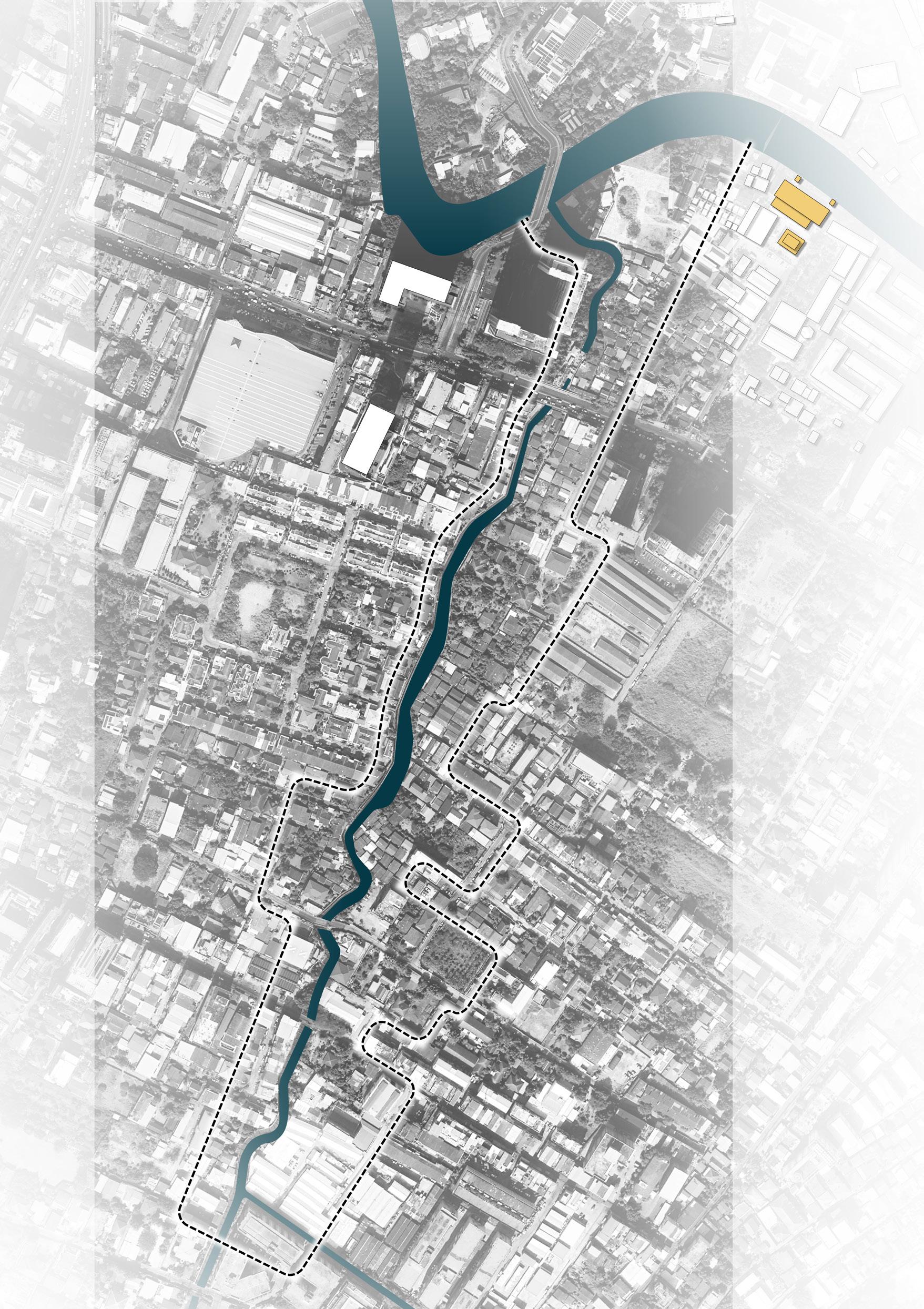

The image on the right illustrates this uneven vulnerability, particularly among residents living along the city’s khlongs, most notably along Khlong Lat Phrao, which flows southward into Khlong Phra Khanong.

One of the areas where inequality in water management becomes most apparent is in the treatment of canalside communities.

Once the lifeblood of Bangkok, these neighbourhoods are now often perceived as obstructions within the city’s water network. It is striking and painful that the very communities who have long lived in close relationship with the water are now the ones forced to adapt in the name of urban flood safety, while the city around them has undergone a complete transformation.

Through the Baan Mankong program, the Community Organization Development Institute (CODI) seeks to upgrade these informal settlements, a process that may improve short-term drainage yet often weakens the spatial and social relationships that once connected residents to the water.

The next page offers an overview of how this transformation has unfolded in Bangkok.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

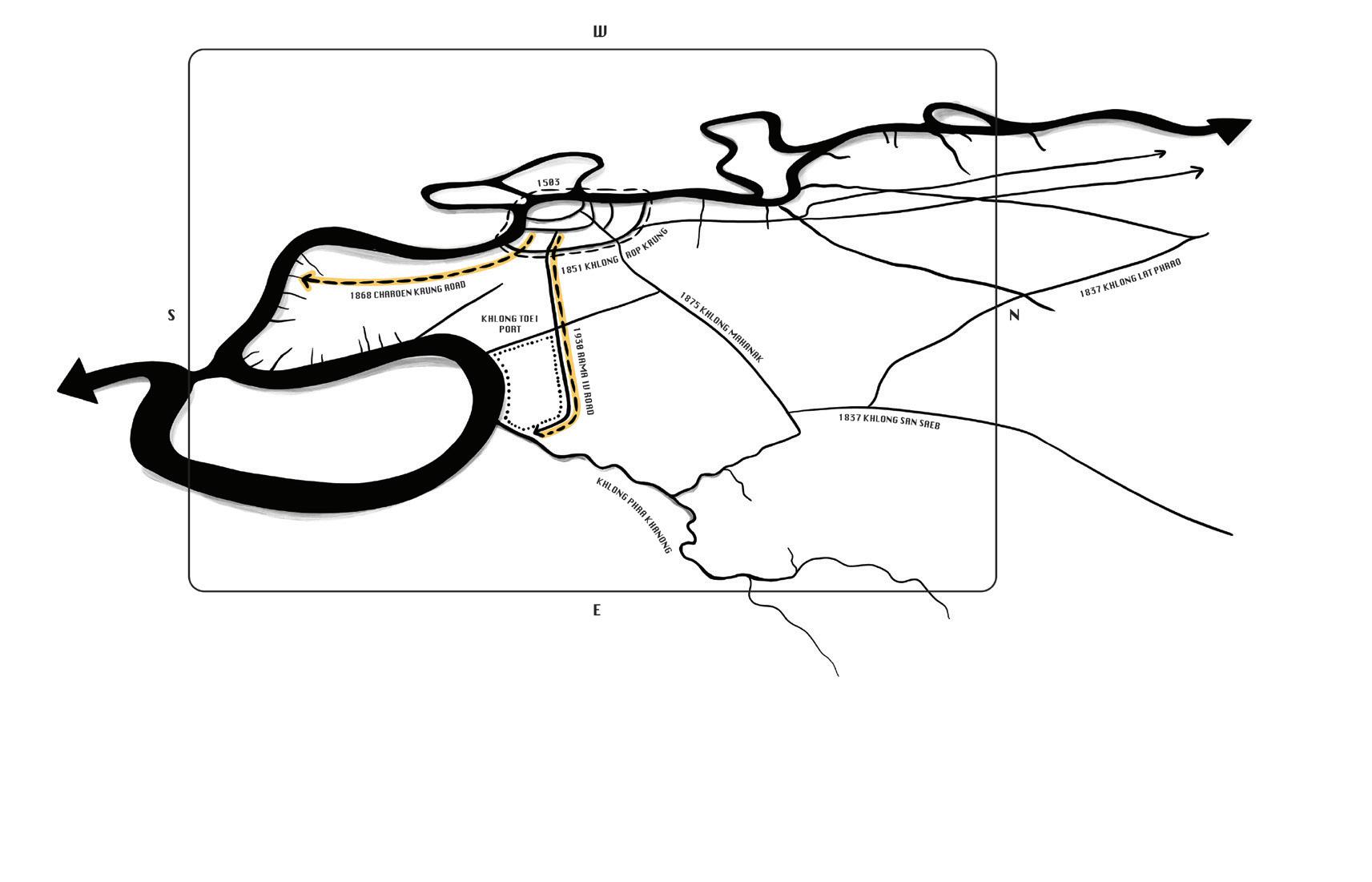

After the fall of Ayutthaya the new capital was established on the inner bend of the same Chao Praya river downstream. Perfectly positioned as a fortress protected by wet soils and the river.

But to grow to the stature of a capital the new king Rama V decided to develop a city plan on the other side of the river. Here was enough space to develop and water would naturally refresh the planned rings of canals

Newly dug khlongs connecting to other rivers allow the city of Bangkok to grow into different directions. The first two roads are commissioned by foreigners: the first parallel to the river for shophouses, the second to shortcut towards the port of Bangkok closer to sea.

After the first two roads many more followed starting an urban sprawl away from the more stable soil deposits along the river. The Landbased city became the norm.

Within Bangkok’s polder-like system, only two undrained wetlands remain in the heart of the city. While a complete dismantling of this engineered water machine is neither realistic nor a short-term solution to flooding, preventing further mechanisation is a crucial first step. Yet the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) continues to propose new pumps and expanded drainage capacity, turning once-

lively canals into hyper-efficient discharge corridors. Such interventions reinforce the waterbed effect, locking the region into a perpetually defensive logic. This deepens dependence on mechanical control and further erodes the cultural and landscape identities once defined by Bangkok’s adaptive relationship with water.

Bangkok’s defensive pursuit of resilience reflects a weaving error in contemporary water management. Resilience, by definition, seeks control and stability, an ability to return to the status quo after disturbance. While this seems desirable, it prevents true evolution of the urban system. An alternative perspective emerges through the lens of anti-fragility, a concept that embraces variability and disturbance as forces of renewal.

Rather than resisting shocks, anti-fragile systems learn and improve through them. In landscape terms, this shift translates to an affective approach grounded in delay and store measures that align with nature-based solutions. Such an approach enables the urban landscape to absorb, adapt, and even benefit from variability. Temporarily storing or delaying water introduces dynamic ecological and spatial processes that build flexibility rather than rigidity. Anti-fragile water landscapes treat uncertainty not as a threat but as a generative force.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

A key spatial foundation for developing such a delay-and-store strategy lies in restoring and expanding Bangkok’s green–blue arteries. The city’s limited green spaces must be strengthened to retain and gradually release water, fostering a more adaptive urban metabolism.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

Broadening the lens on Bangkok—from water management to its wider urban complexity— reveals the multitude of challenges the city now faces. A narrow focus on safety and dryness has neglected the delta landscape and its amphibious culture. Reconnecting to this foundation requires a water- and soilled approach that treats hydrology as the structuring element of the urban fabric.

Such a perspective envisions a multi-layered city—one that integrates water, land, and culture into a single adaptive metabolism. What new relationships with the watery environment might emerge if it were embraced once more? The lost geo-choreographies of Bangkok’s delta could guide us toward recovering an intimacy and affection with water, transforming it from a threat into a teacher.

The two remaining wetlands in Bangkok embody the city’s final chance to preserve spaces that work with water rather than against it. More than historic remnants, they illustrate the principles of anti-fragility—absorbing and adapting to disturbance.

Though exposed to flooding, local communities have evolved with these dynamics, revealing water’s dual role as both risk and teacher. These wetlands remind us that water’s power lies in its ambiguity and motion, where the amphibious and the informal continue to shape the city’s living fabric.

Parks, wetlands, and canal corridors can function as porous infrastructures absorbing excess water while simultaneously improving microclimates, biodiversity, and public wellbeing. These open spaces provide the structural framework for a shift from a defensive to a regenerative water logic.

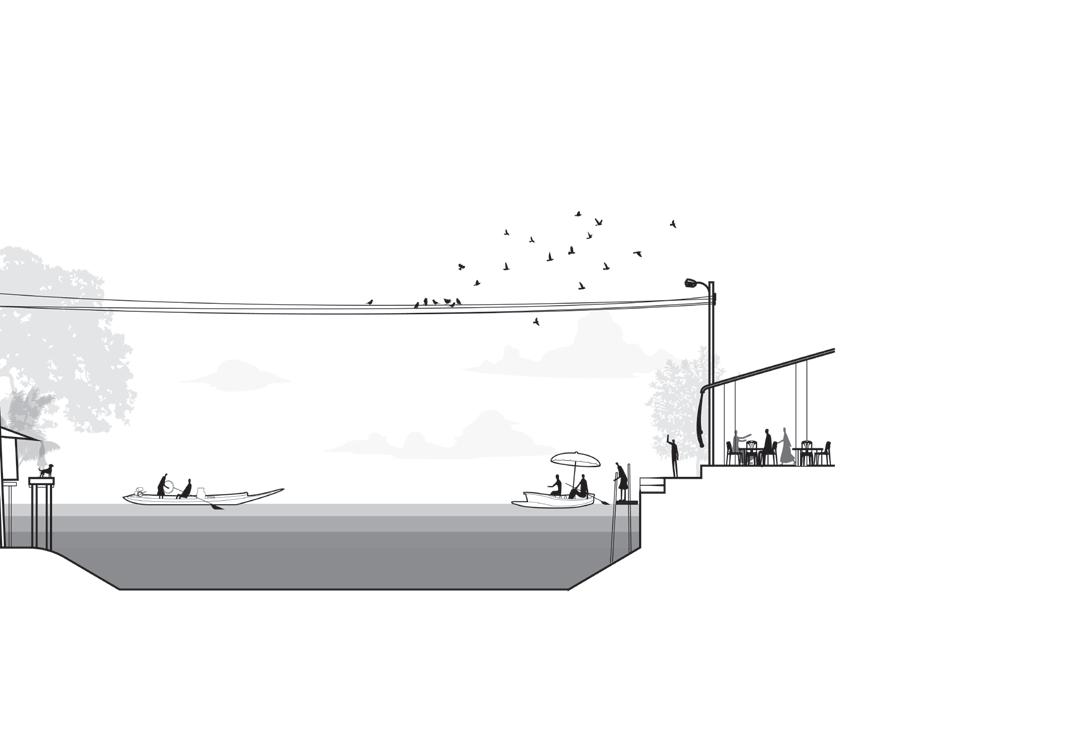

Although the importance of Bangkok’s khlongs has diminished under road-based urbanisation, these waterways historically embodied the city’s cultural abundance and vitality. A layered landscape approach that re-animates the green–blue network could reintroduce informal and communal life to the water’s edge. In doing so, it transforms canals from infrastructural backwaters into vital social and ecological arteries. Amid rising urban heat, air pollution, and congestion, these spaces could again serve as refuges for public life.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

WATERMACHINE STRATEGY

WATERBED EFFECT

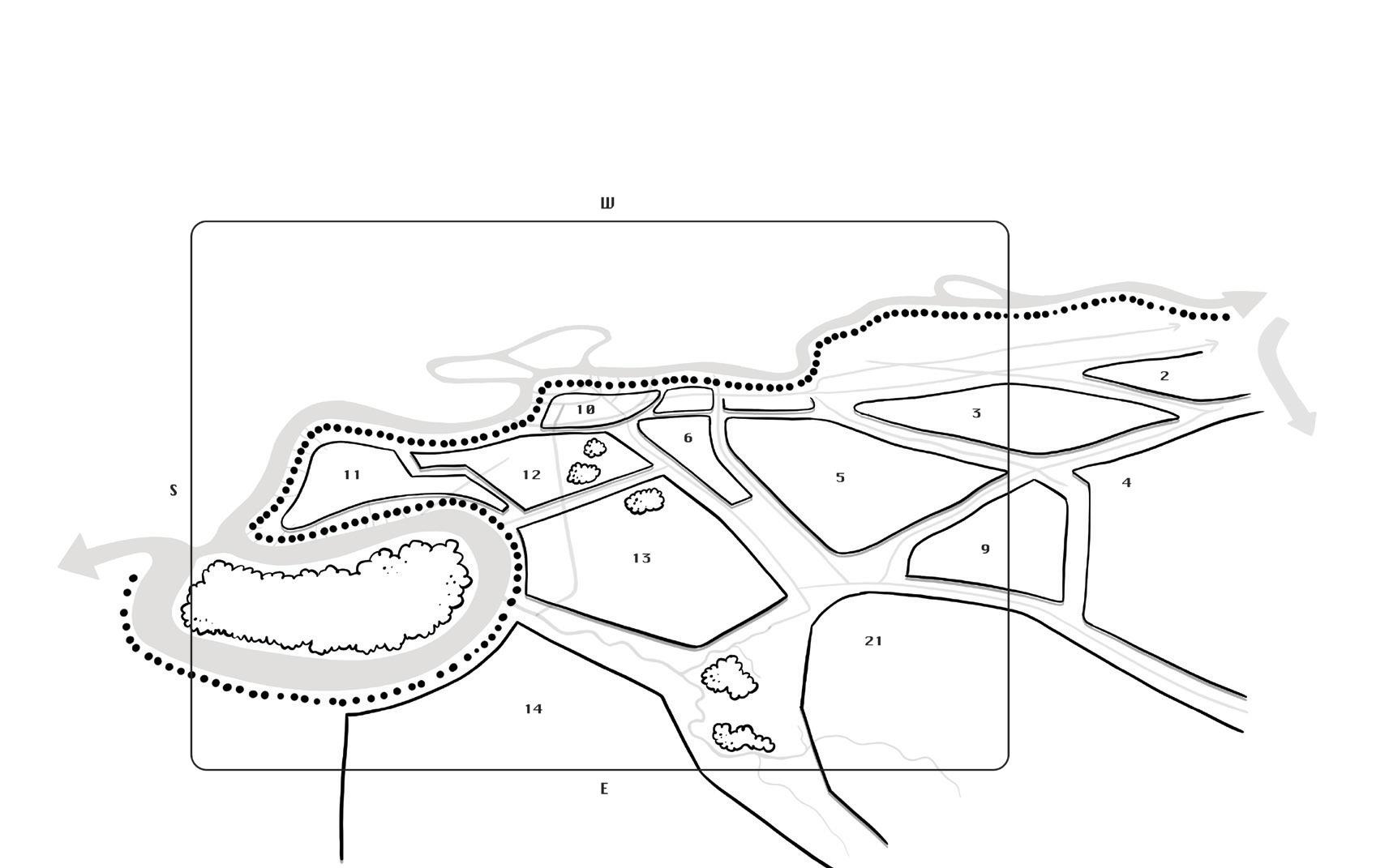

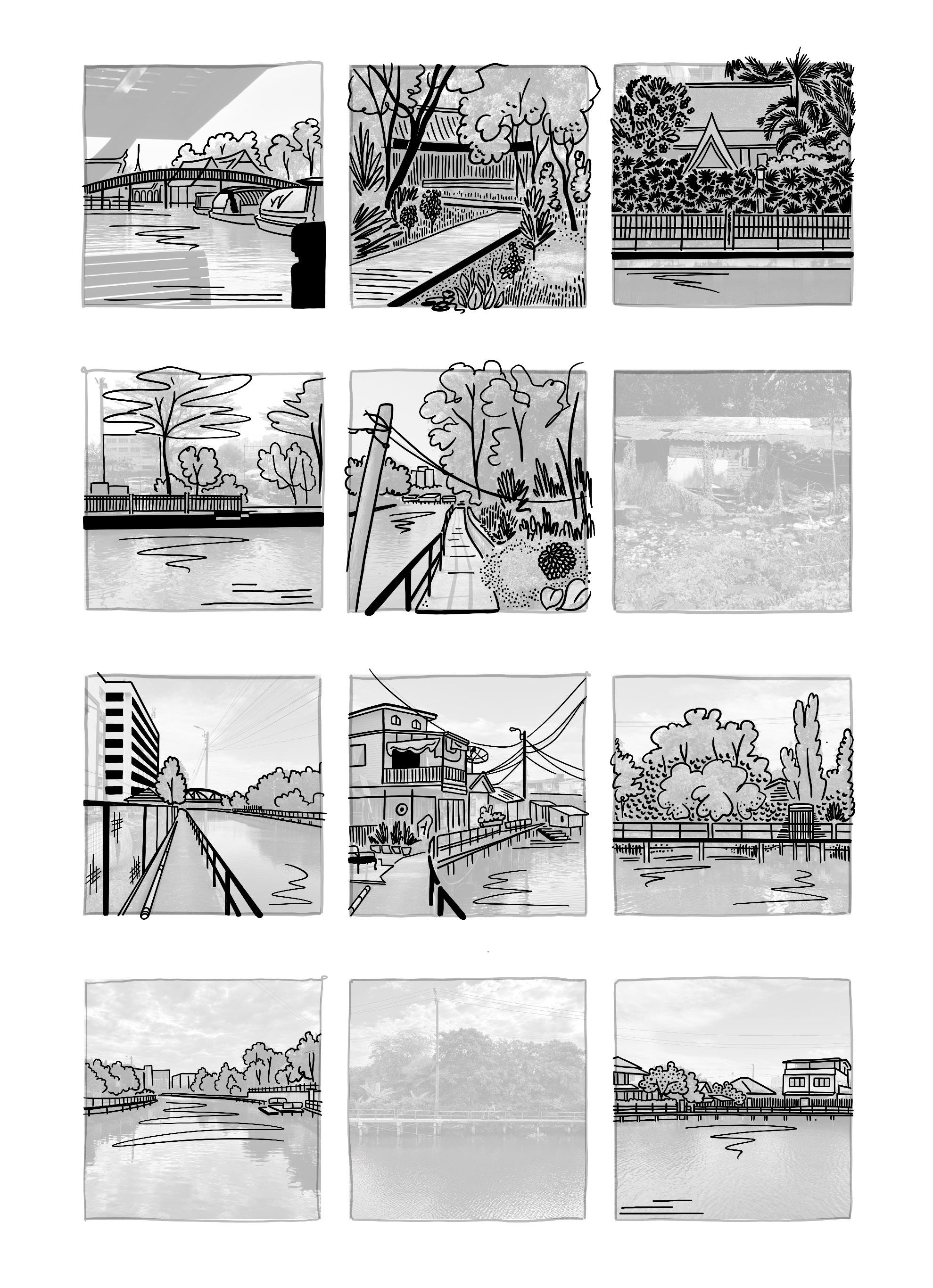

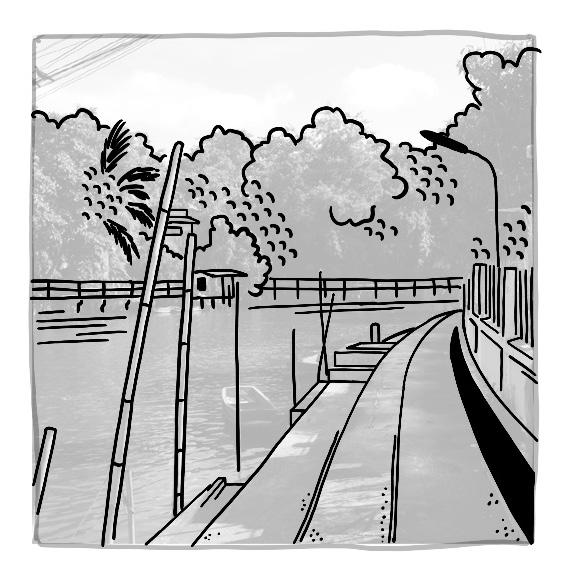

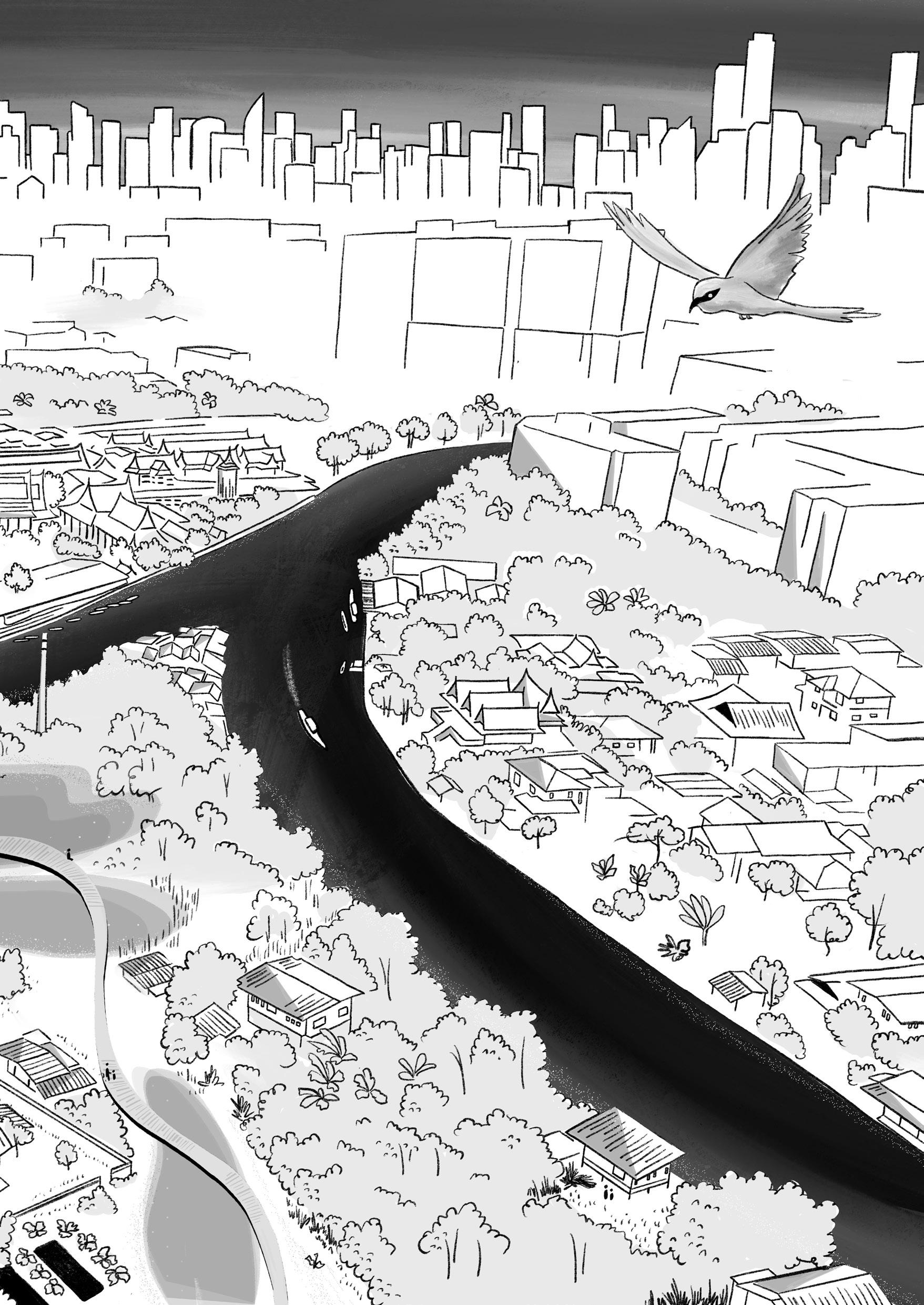

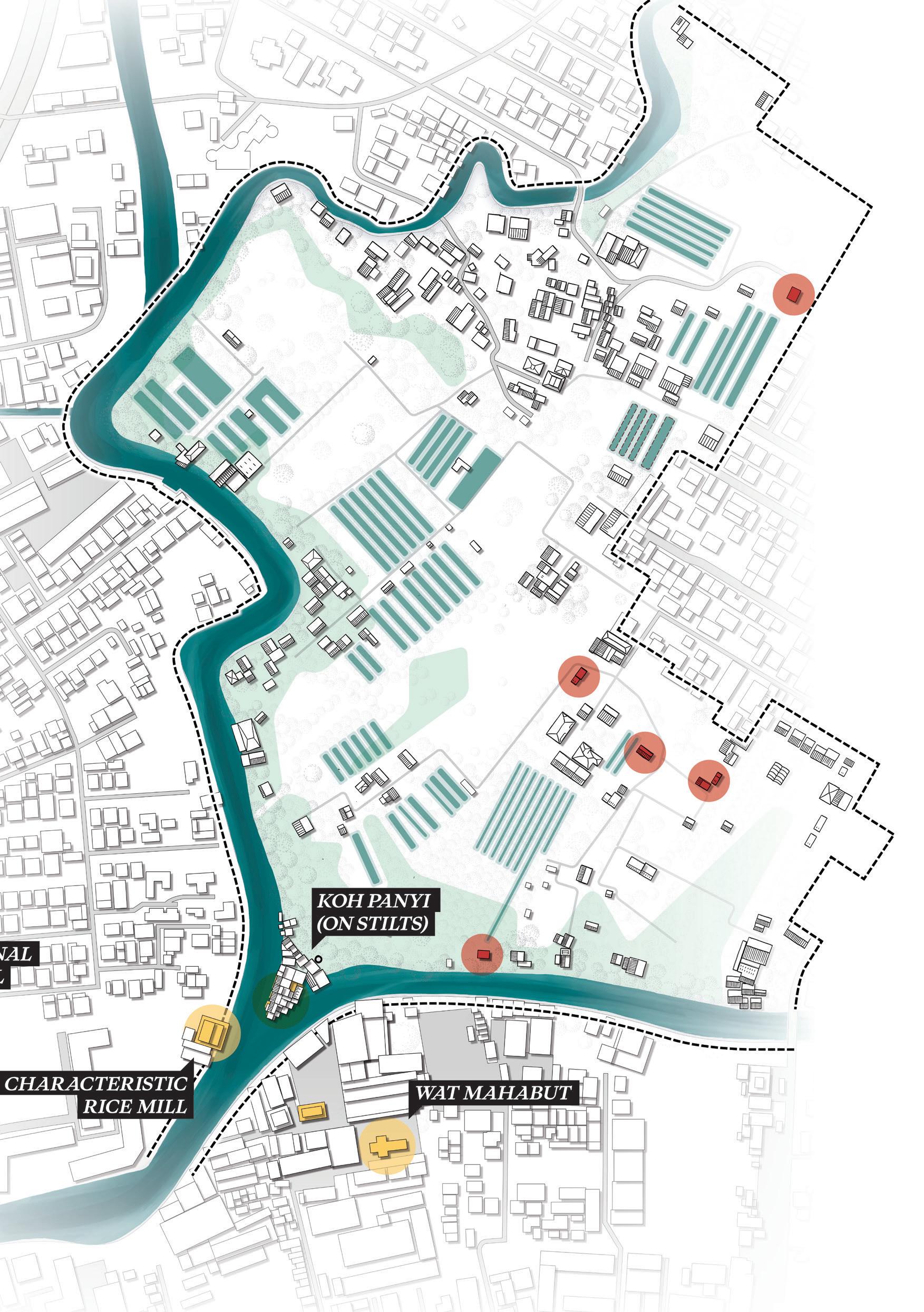

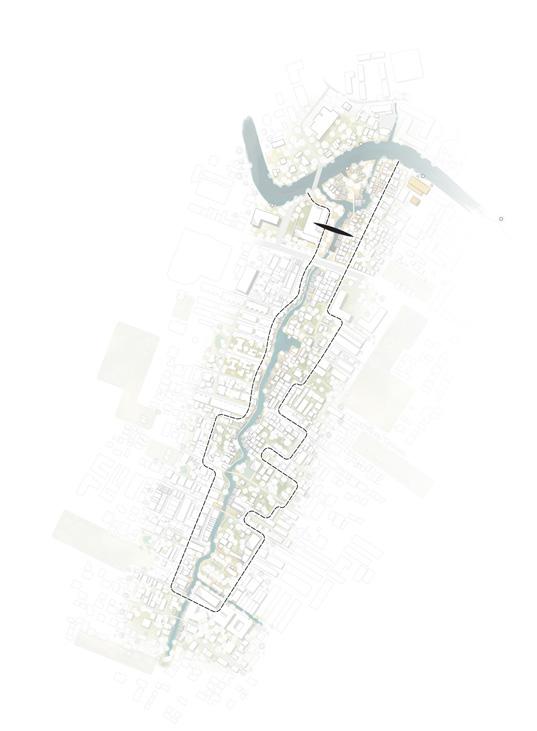

The wetland adjacent to the Khlong Phra Khanong traces a unique history. Characterised by many waterfront houses and tropical orchards this canal distinguishes itself from the more urban canals of Bangkok.

This may partially be due to the natural origins of this old khlong which can be read from the meandering shape.

Discovering this neighborhood by foot taught me a completely new perspective on how this place came to be and preserved. Next page firstly sheds a light on the urban growth of the Khlong Phra Khanong area:

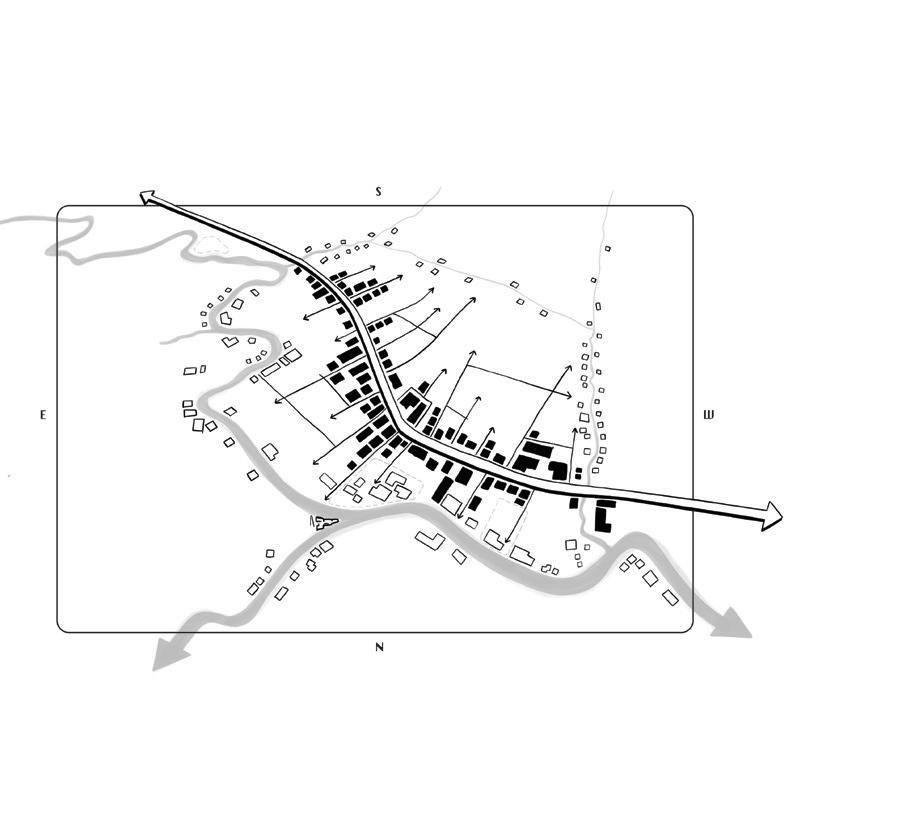

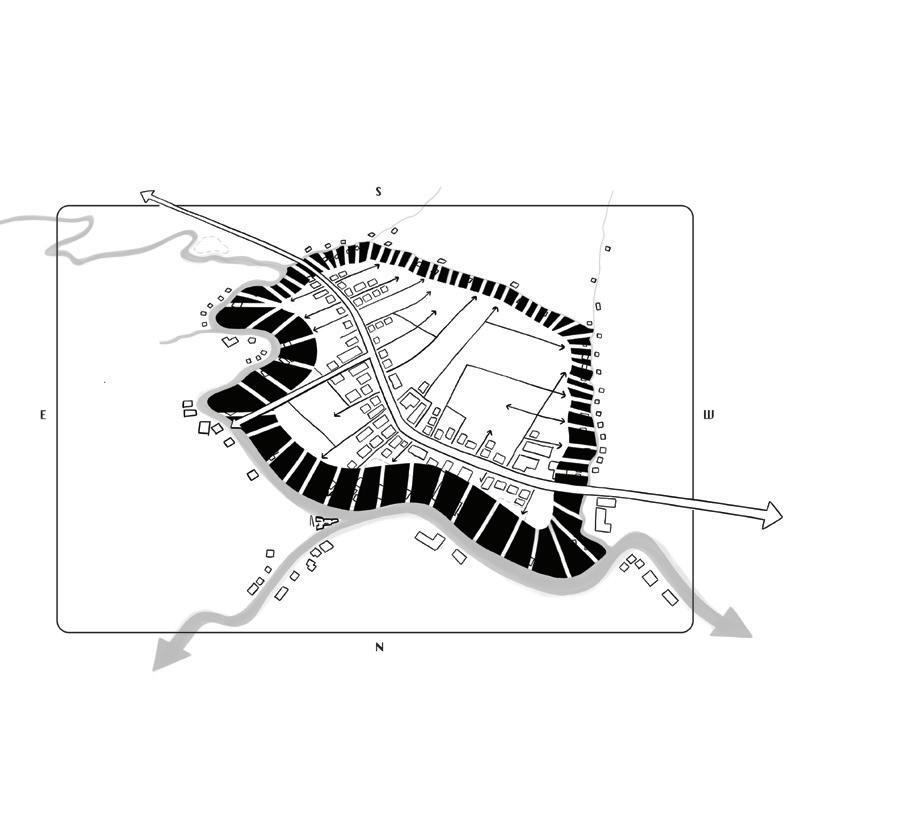

A naturally meandering river initially positioned with an independent village before entering Bangkok. Temples which are the communities cultural focus line along the stream

Housing emerges along the streamsbanks. To accomodate population growth new canals were dug perpendicular to the mainstream to allow for new plots to be developed.

Additional canals dug between perpendicular canals facilitate a complete cultuvation of unused or unaccessible land. This optimises water drainage for tropical orchards

While water always acted as an urban front, the introduction of roads acted as a tipping point flipping over the urban fabric where urban developement started to be land-based

The role of water descreases from a cultural focal point to a polluted backside which only serves as a hyper-efficient drainage system.

These are unbuilt areas which are not actively drained. Often maintaining an ecological as well as an cultural porosity of the waterside. Institutional plans for new pumping stations threaten the status quo by cutting these systems off.

Phra Khanong

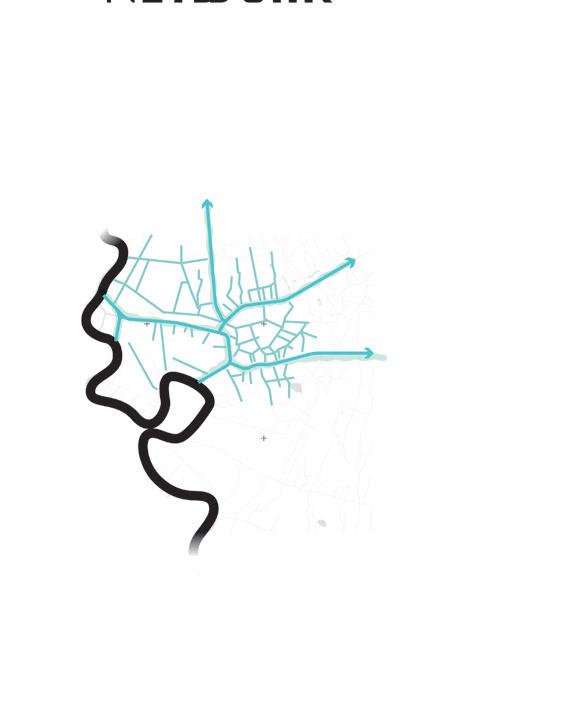

Khlong Phra Khanong can be indicated as bosom canal which in turn drains through a pumping station onto the main river the Chao Praya towards sea. Large distances can be crossed without hinderance of pumping stations or sluices.

These constitute of smaller canals behind pumping stations in mostly residential and green areas. These drain onto the larger bosom canals.

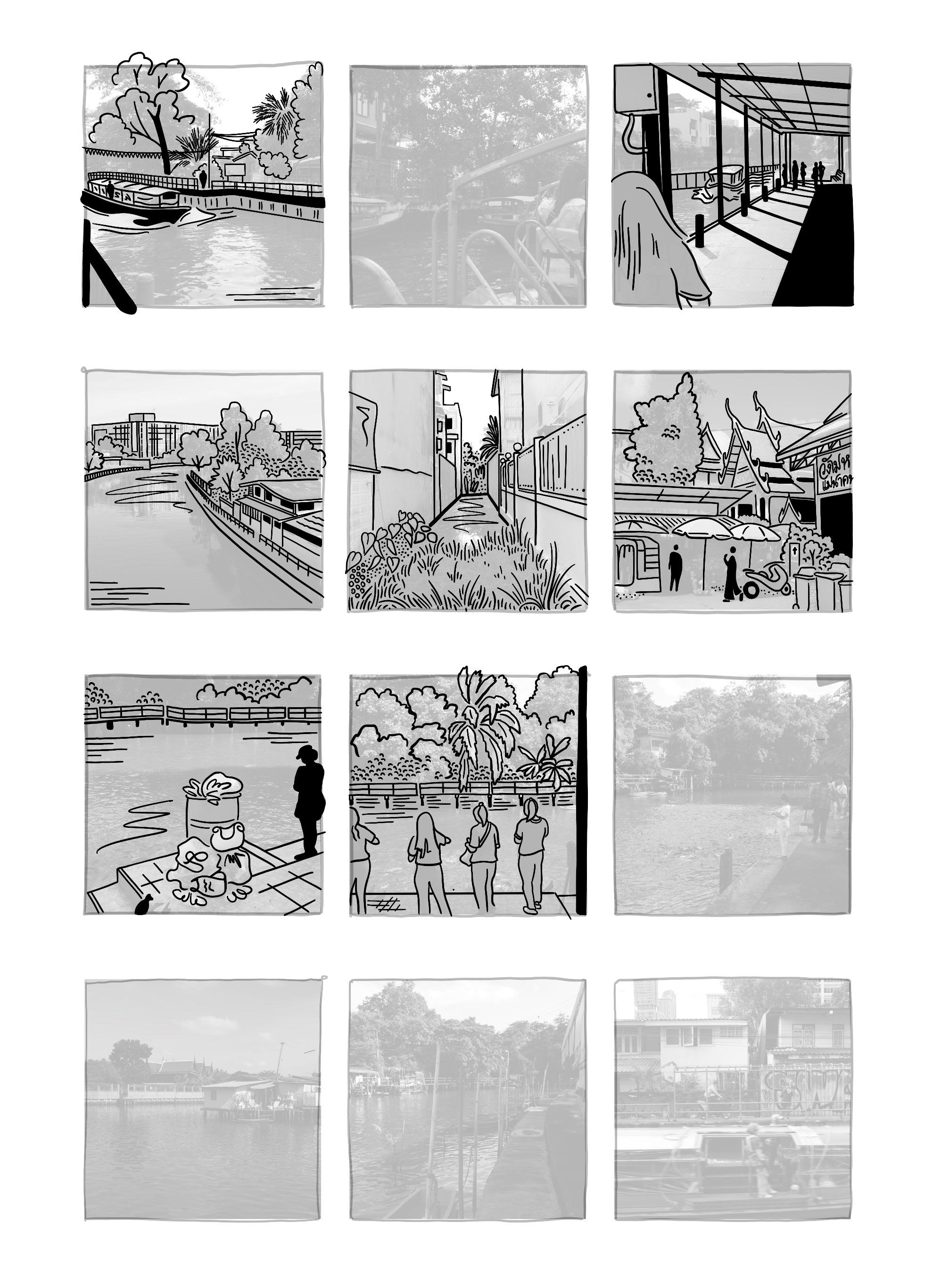

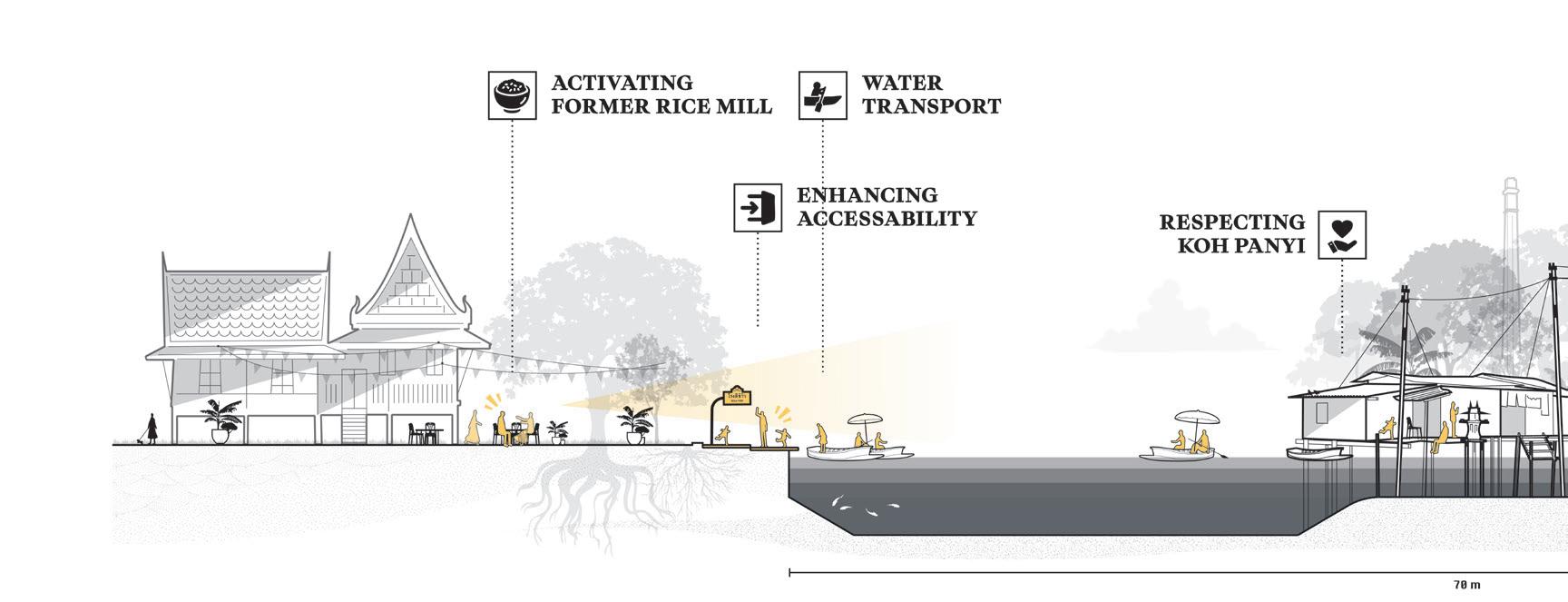

Koh Panyi is named after the original in the Gulf of Thailand this small migrant community has lived here for decades.

Elevated walkways float above the lush, swampy ground.

As I reach the smaller side canals, the walls on both sides begin to close in, narrowing the space.

Vegetation in the water is minimal, though reeds and lotuses appear at certain junctions where waterways meet.

The Jim Thompson House illustrates the potential of Bangkok’s canals as both cultural heritage and tourist attraction.

The wetlands, in contrast, reveal a far more porous transition between water and land. Although closed off by a large gate, one can still catch glimpses of tropical fruit orchards beyond.

A socially vibrant waterfrontn with restaurants can still be seen along Khlong San Saeb, closer to the center of Bangkok.

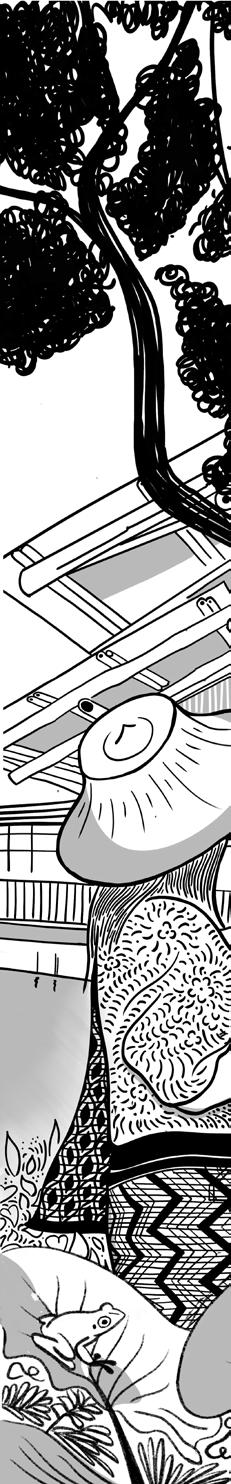

Traditional Thai architecture is an important source of inspiration, showing the deep connection with water.

The small stilt village nicknamed Koh Panyi is entirely dependent on boats for transportation.

Elderly women, in particular, can be seen paddling between temples under parasols, selling their goods.

A few houses along Khlong Phra Khanong have retained their orientation toward the water, with small mooring spots still in use.

In most places, concrete walls continue to dominate the canal edge. What stands out, however, is that the sensory experience of the water quality here feels less repelling than in the smaller khlongs.

I follow the canal alongside concrete walls, behind which tall trees rise above the edge.

Temples today are mostly oriented toward the street, though many were originally established along the water.

Rituals are still performed, such as feeding fish or birds, though these practices often coincide with some degree of pollution and waste.

The diversion of water through local land elevations is common among modernized houses, often leaving stagnant water trapped between buildings.

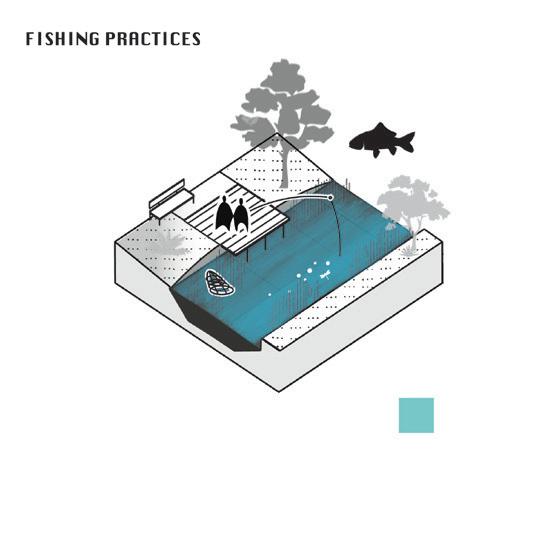

The pumping station, many fishermen cast their nets, benefiting from the stirred-up water.

Concrete structures reinforce the embankments. It is possible to walk across them, but they are rarely used.

The pumping stations form a significant barrier within Bangkok’s green–blue network, also separating spaces on a socio-cultural level.

Reinforcement of the khlong’s embankments is actively taking place, especially near the pumping station.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN |

Enchanting the Watermachine

disconnected flow construction as walkway concrete waterside stagnant water solid and waste pollution

connections over long distances paths as walkways porous waterside flowing water underutilised banks

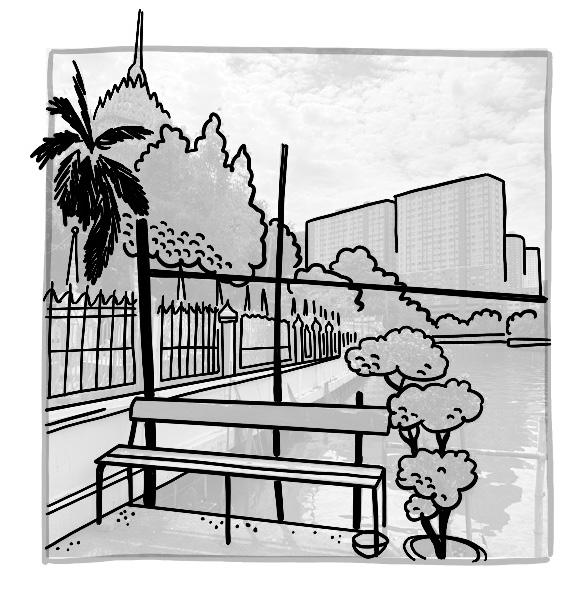

.7 THIS IS THE WATERFRONT ALONG THE KHLONG PHRA KHANONG WETLAND. APART FROM THE BOATS, IT IS THE ONLY ACCESS ROUTE TO THE STILT VILLAGE.

Over the course of this project, I visited Bangkok several times, each visit corresponding to a different phase of the research.

Initially, I explored sites across the city from the dense downtown core to the suburban fringes. Following these khlongs my attention later turned more specifically to the Khlong Phra Khanong neighborhood, where I spent time walking along its canal edges and backstreets.

.1 CONSTRUCTION WORKERS ARE REINFORCING THE WATERFRONT WITH CONCRETE WALLS. THIS ELIMINATES THE POROSITY OF THE QUAY AND A GRADUAL TRANSITION BETWEEN WET AND DRY.

.2 TEMPLES ALONG KHLONG PHRA KHANONG ARE AMONG THE FEW PLACES WHERE A GREEN AND ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT HAS BEEN PRESERVED.

.3 RESIDENTS OF HIGH-RISE COMPLEXES ALSO HOLD THE PRIVILEGE OF ACCESS TO THE WATERFRONT. HERE, HOWEVER, IT IS NOT REGARDED AS A LUXURY. ALTHOUGH LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS ARE COMMISSIONED TO DESIGN THE LUSH GARDENS, THE LANDSCAPE STOPS AT THE WALL THAT MEETS THE WATER.

.4 RAISED GROUND LEVELS AND WALLS FORM NOT ONLY A BARRIER AGAINST WATER AND POLLUTION, BUT ALSO OBSTRUCT SOCIAL INTERACTION.

.5 CLOSER TO THE CITY CENTER, WATER TRANSPORT IS STILL WIDELY USED, BUT AROUND KHLONG PHRA KHANONG IT HAS DECLINED SINCE THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC.

.6 THE CONCRETE STRUCTURES CROSS THE ELEVATED EDGES OF THE WATERWAY. BEHIND THEM, MANY TRADITIONAL THAI HOUSES STILL STAND—ALSO ELEVATED, BUT COMPLETELY SEPARATED.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN |

Enchanting the Watermachine

While I am formulating a strategy to anticipate on a watery future I have come to realisation that the rational does not always have to determine reality nor future.

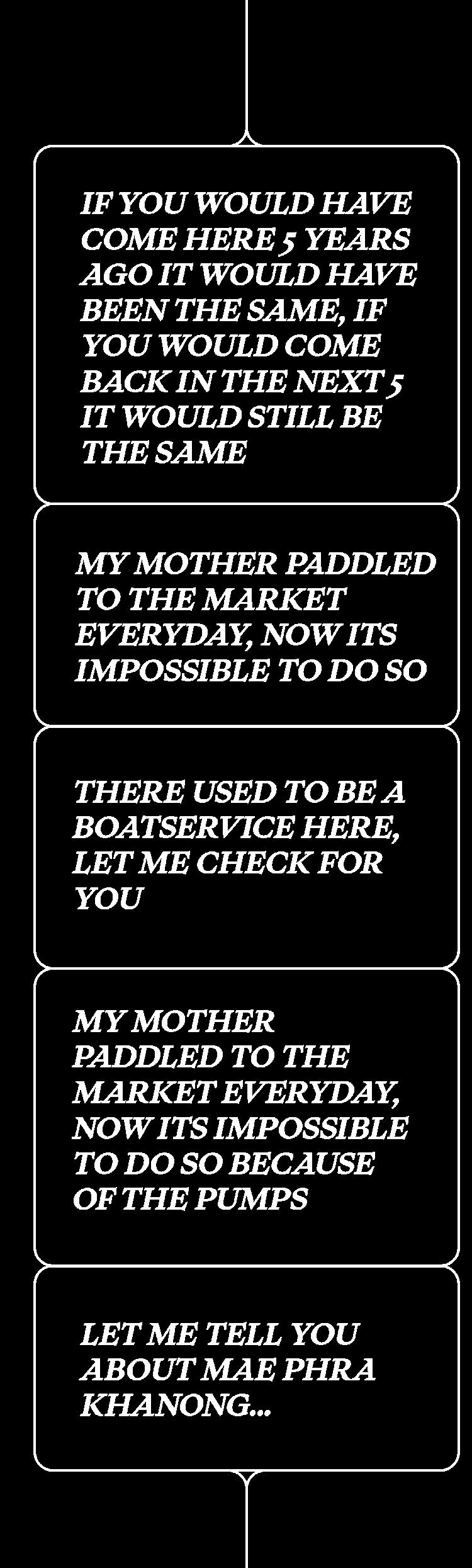

From my dialogues around khlong phra khanong many wondered why I picked this place, and why the khlongs...?

One of the reasons the wetland has not been actively drained and developed yet is that the myth of Phra Khanong. The woman the neighborhood and canal are named after she drowned at this exact spot across temple Wat Mahabut

What fascinated me most during my project is a history forgotten by the people on the street. When I ask about flooding, they say it’s manageable. When I ask about the problems, I get a shrug. Peter, whom I met several times at the temple, told me:

“Nothing changes here. Five years ago was the same as now, and if you come back in ten years, it will be the same still.”

What he did want to talk about was the story of Mae Nak, the spirit who makes this temple so popular, a national myth. As we sat by the water, he began his story. Here, in Phra Khanong, the khlong was once the lifeline: the road, the market, the playground. The vibrant khlong was life. Mae Nak lived here two hundred years ago, in a house on stilts, breathing in the scent of the falling rain. While her husband Mak was at war, she died in childbirth.

When Mak returned, he found her as he had left her, unaware he had returned to her spirit. This temple, where I now sit watching people feed the fish, is the very place Mak fled to, and so, Peter explained, Mae Nak’s spirit doesn’t just wander the water. She has become the symbol of the water itself

“

RE-ENCHANTING THE ENVIRONMENT TO HONOUR ALL INCRANATIONS OF MAE PHRA KHANONG AT THIS PLACE. FOR A HEALING OF CONNECTION AND PLACE.

And yet, what have we done to her water? We have built high walls and installed pumps that suffocate the canal. When I first walked these banks, I no longer smelled the rain, but the biting stench of sewage. The water Mae Nak loved now evokes disgust. We have turned her home into a tomb. Her spirit, trapped in the machine, has become a shadow, a mirror of our own neglect.

My design, therefore, is not just about controlling floods. It is about enchanting the watermachine. The old story was about a spirit who refused to let go. This new story is about us, the city, finally learning to answer her love. An act of reconciliation, almost a ritual.

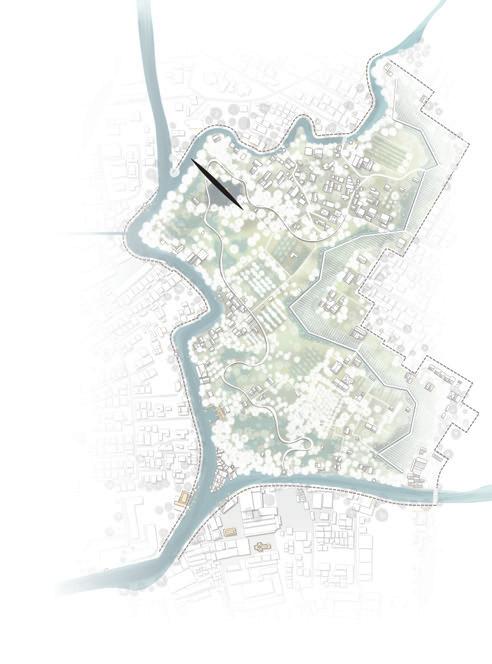

Three opportunties are indicated to break free from the landbased lock-in.

BANGKOK

WATER ACCESS

Three landscape interventions allow for a more affective water approach to the khlongs of Bangkok

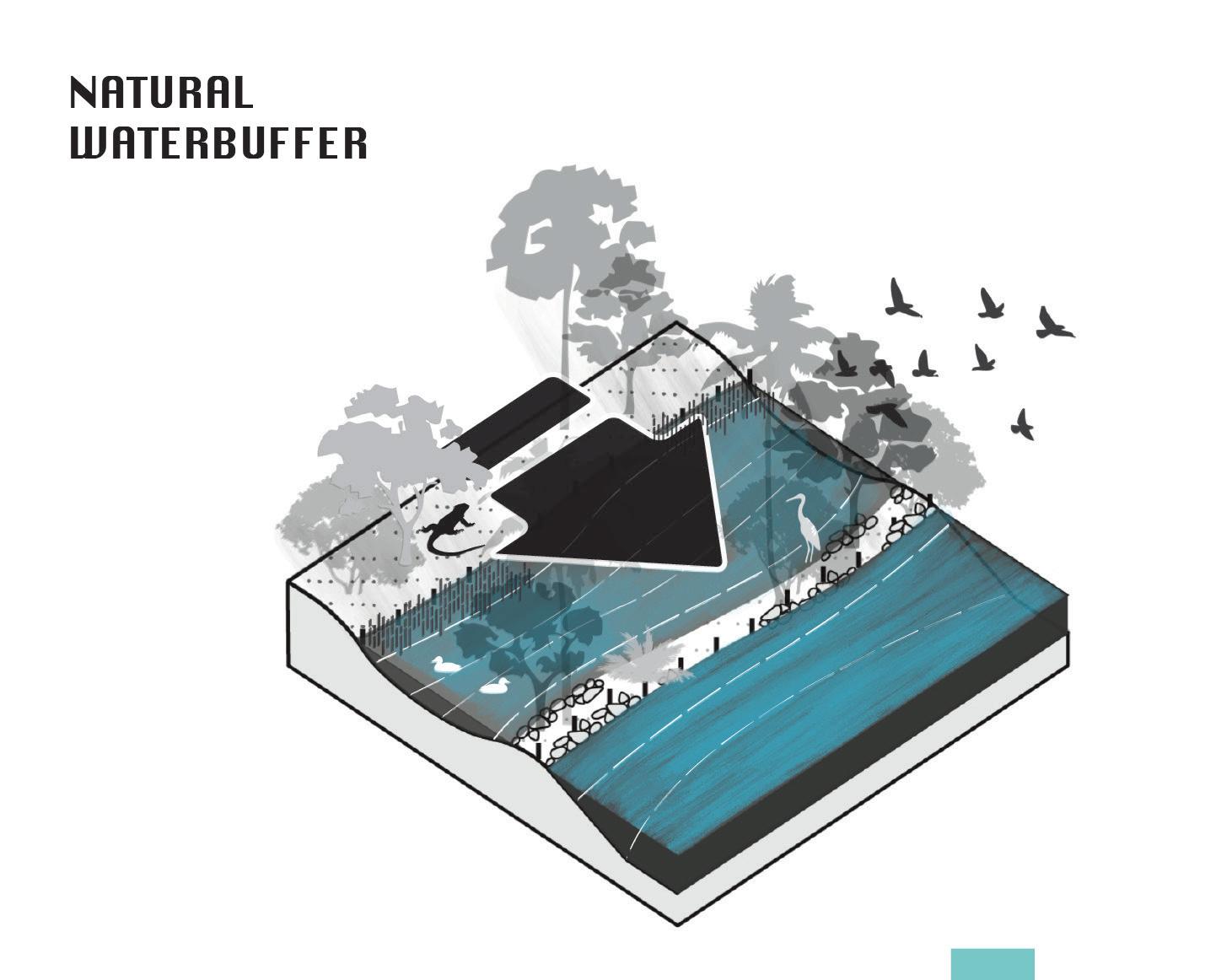

1 – Firstly defining an alternative approach to dealing with excess amounts of water quantity, and thus safety is embracing water by delay and storage instead of resistance and discharge. In other words, a slower metabolism of water.

2 – Secondly the current state of water evokes disgust with the Bangkokians. A reduction of solid waste pollution, wasterwater discharges on open water, and ecological treatment are involved with this topic.

3 – Third is the re-introduction of access to water. By utilising the qualities of amphibious conditions temporality and informality can flourish in these otherwise redundant spaces. In a way to learn to live with water again, find care and a common space for eco-sociocultural interactions.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

BANGKOK METROPOLITAN ADMINISTRATION

STRATEGY AND PLANNING DEPARTMENT

FINANCE DEPARTMENT

BUREAU OF BUDGET

BANGKOK DISTRICT SUAN LUANG

PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT

DRAINAGE AND SEWERAGE DEPT.

DEPT. OF ENVIRONMENT

HEALTH DEPARTMENT

BANGKOK EDUCATIONAL OFFICE

TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT

DEPT. OF PLANNING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

OFFICE OF DISASTER PREVENTION AND MITIGATION

MEDICAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT

METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT OF THAILAND

ROYAL FOREST DEPARTMENT

DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL PARKS AND CONSERVATION

ROYAL IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT

DEPARTMENT OF LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT

DEPARTMENT OF RURAL ROADS

DEPARTMENT OF GROUNDWATER RESOURCES

DEPARTMENT OF MINERAL RESOURCES

DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES

DEPARTMENT OF ROYAL RAINMAKING AND AGRICULTURAL AVIATION

ELECTRICITY GENERATION AUTHORITY OF THALAND

DEPARTMENT OF ALTERNATIVE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT AND EFFICIENCY

More than fifty stakeholders are involved in Thai water management. Despite the presence of both knowledge and governmental ambition, expertise remains largely fragmented across institutional silos. Consequently, the prevailing top-down approach has proven insufficient in safeguarding the everyday lives of Bangkok’s residents.

HYDRO-INFORMATICS INSTITUTE

METROPOLITAN WATERWORKS AUTHORITY

PROVINCIAL WATERWORKS AUTHORITY

MINISTRY OF PUBLIC HEALTH

DEPARTMENT OF DISEASE CONTROL

CITY PLANNING DEPARTMENT

LAND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENTAGRICULTURAL LAND REFORM OFFICE

OFFICE OF NATIUONAL WATER RESOURCES

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING

In response, three key actors are identified who have the potential to realize Bangkok’s three water breakthroughs.

DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES

DIGITAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT AGENCY

THAILAND GREENHOUSE GAS MANAGEMENT ORGANISATON

POLLUTION CONTROL DEPARTMENT

INDUSTRIAL ESTATE AUTHORITY OF THAILAND

DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIAL WORKS

WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY

HYDROGRAPHICS DEPARTMENT ROYAL THAI NAVY

DEPARTMENT OF MARINE COASTAL RESOURCES

MARINE DEPARTMENT

When it comes to water safety, both the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) Department of Drainage and Sewerage plays a crucial role in the ongoing normalisation of khlongs.

Wastewater discharge from homes, businesses, and institutions remains a major issue. Introducing remediative planting by both the BMA and residents can start improving canal water quality through small, collective actions enhancing stewardship.

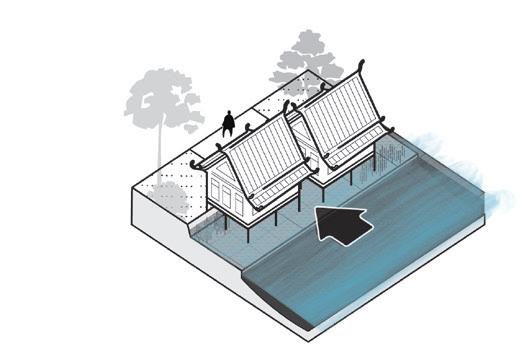

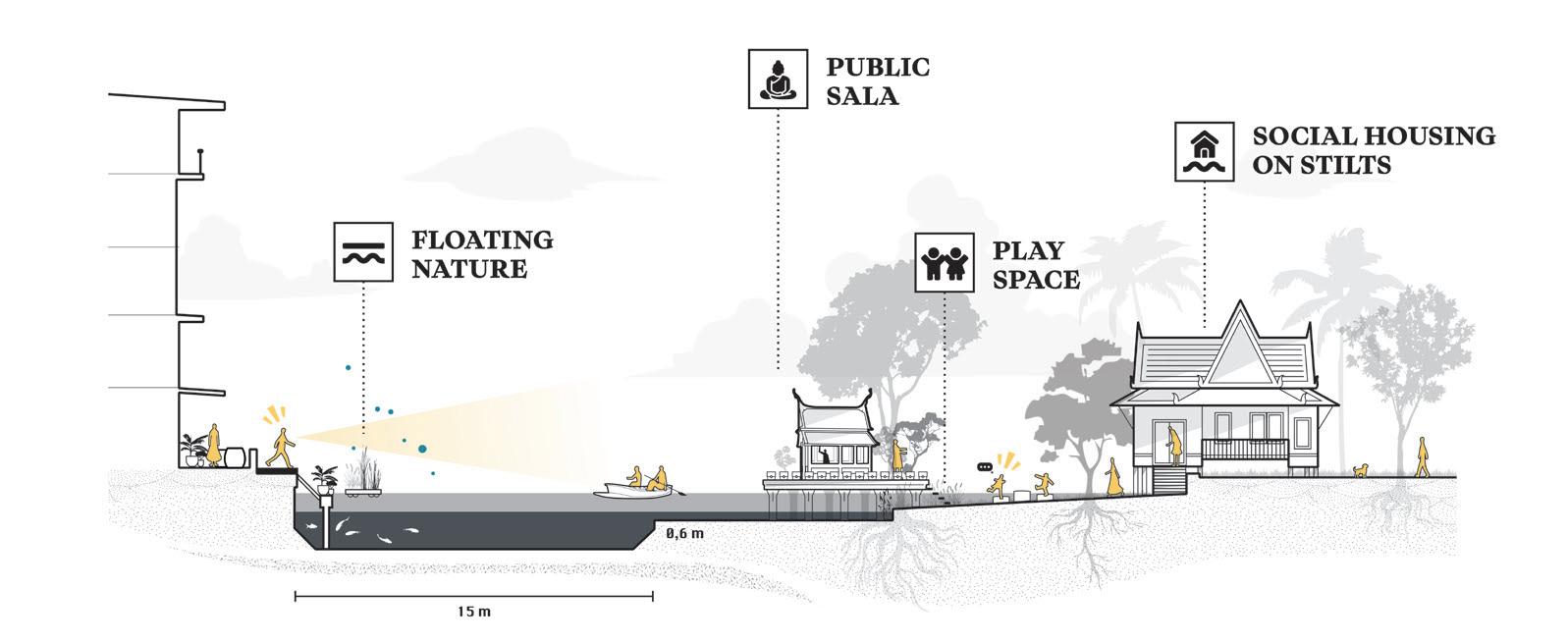

Together with the Community Organisation Development Institute (CODI), experiments in affordable amphibious housing can increase adaptability to fluctuating water levels, making rigid barriers redundant and communities more resilient.

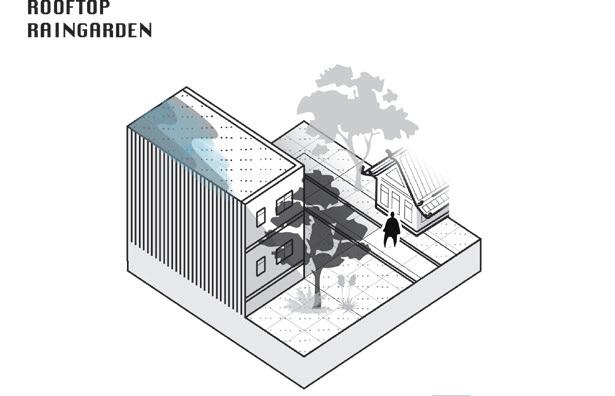

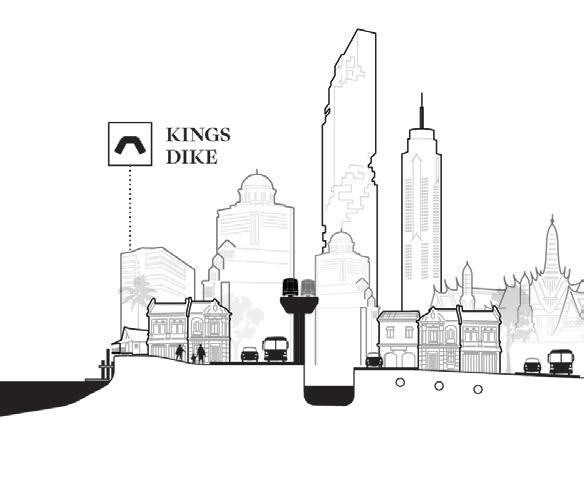

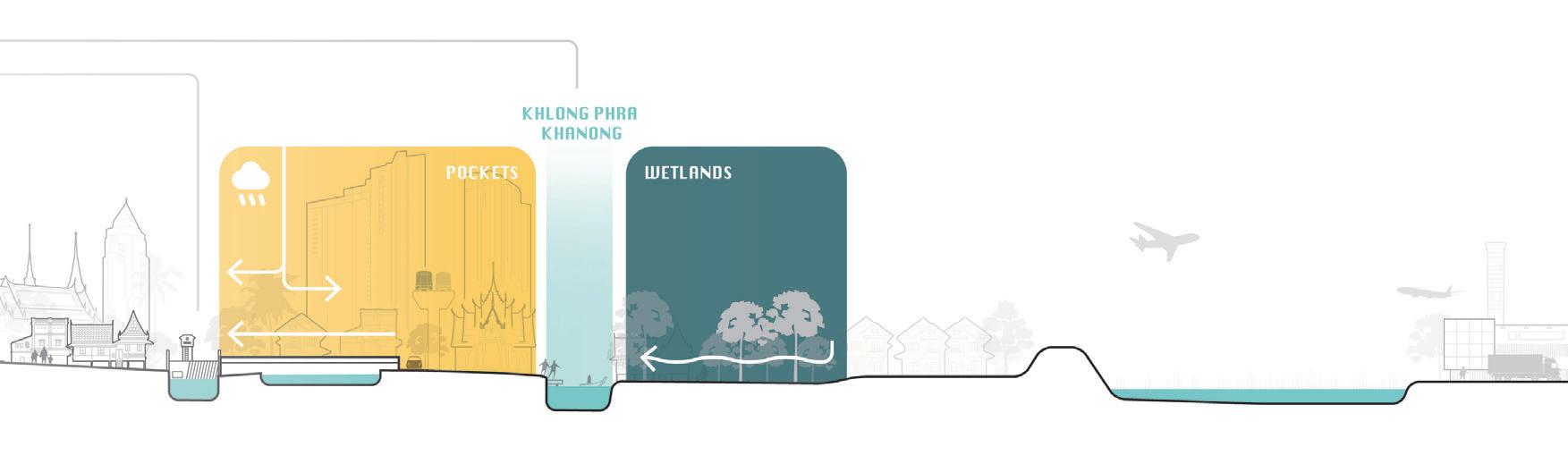

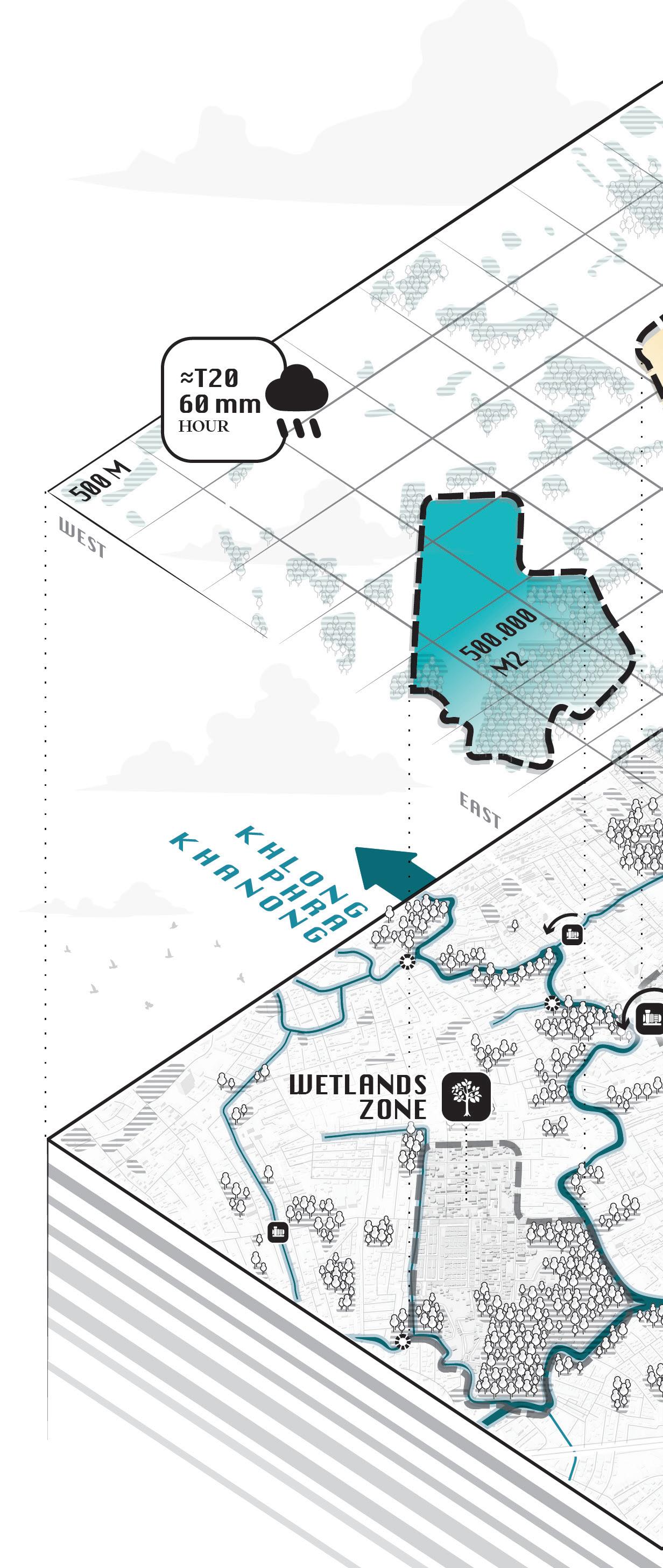

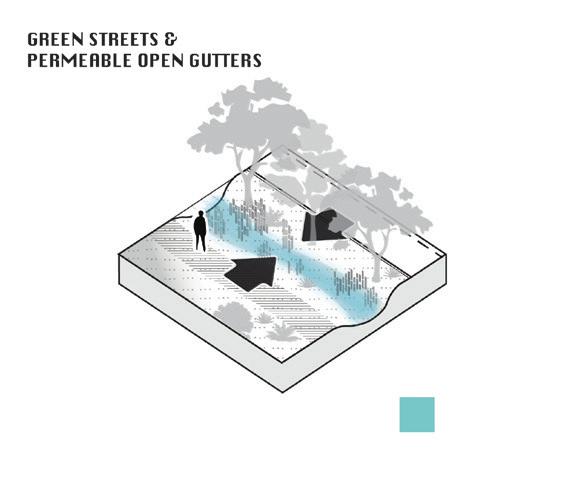

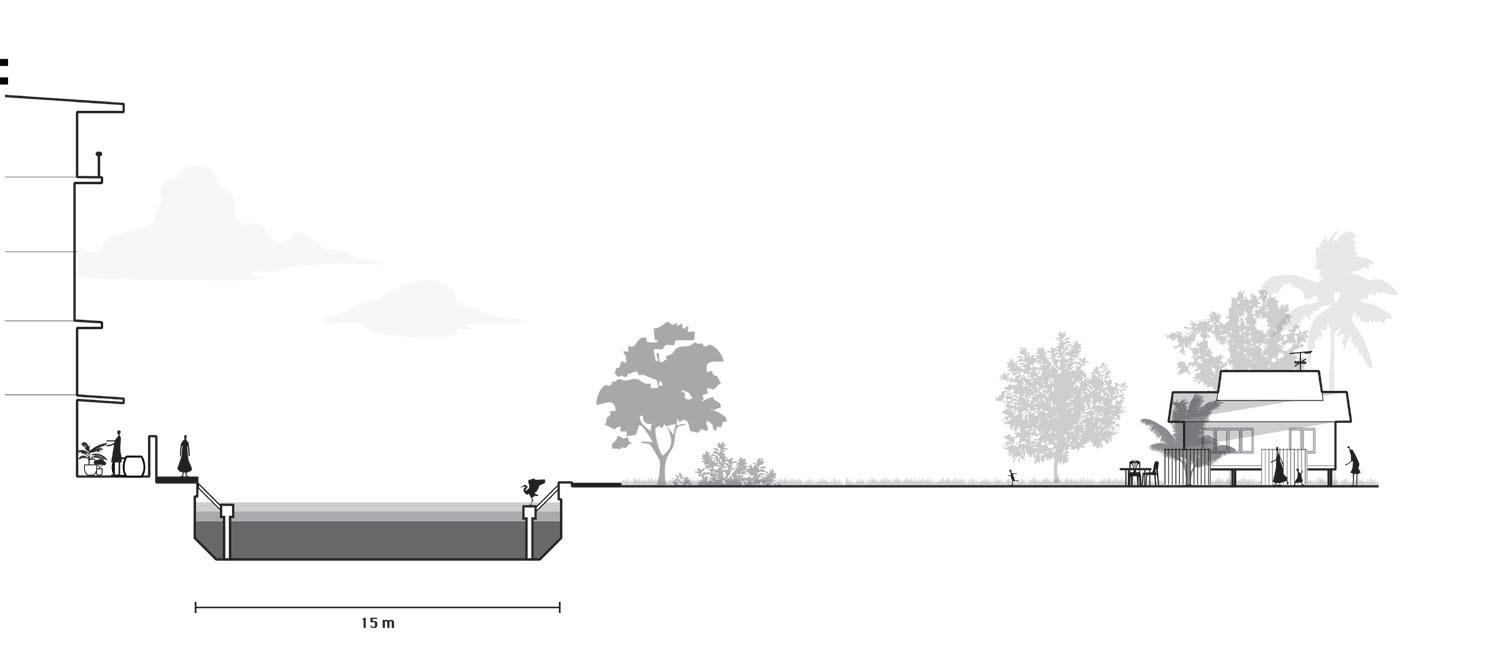

Instead of raising walls to resist and rapidly discharge water, this proposal seeks to slow down and accommodate it. By maintaining porous surfaces and reclaiming canal banks, the design promotes a miniature urban interpretation of the Room for the River principle. Before determining the required storage volumes, environmental scenarios must be defined: BROADENING

Represents the most common condition, typically dry or with a base water level that allows regular use. The design focus lies on maximizing benefits and accessibility during this state.

Describes an occasional flood situation in which access, safety, and health standards must still be maintained. Uses are temporarily reduced or adapted. The 2011 Bangkok floods (a T25 event) serve as reference for this level.

These cannot be fully prevented, especially under increasing climatic uncertainty. The design therefore aims to minimize damage and enable evacuation rather than resist flooding entirely.

Within the proposed wetlands, the total drained surface defined by the BMA plans for drainage corresponds to a volume of 30,000 m3 during a T20 rainfall event. This serves as the design reference.

For the pocket area, which covers a defined catchment, the same rainfall event produces a total runoff of 150,000 m3. Accounting for infiltration, surface flow, and existing pumps, the effective design volumes are reduced to 13,800 m3 for the wetlands and 41,350 m3 for the pocket.

Total surface area 500.000m2 Villa’s, teracced houses, informal houses, tropical orchards

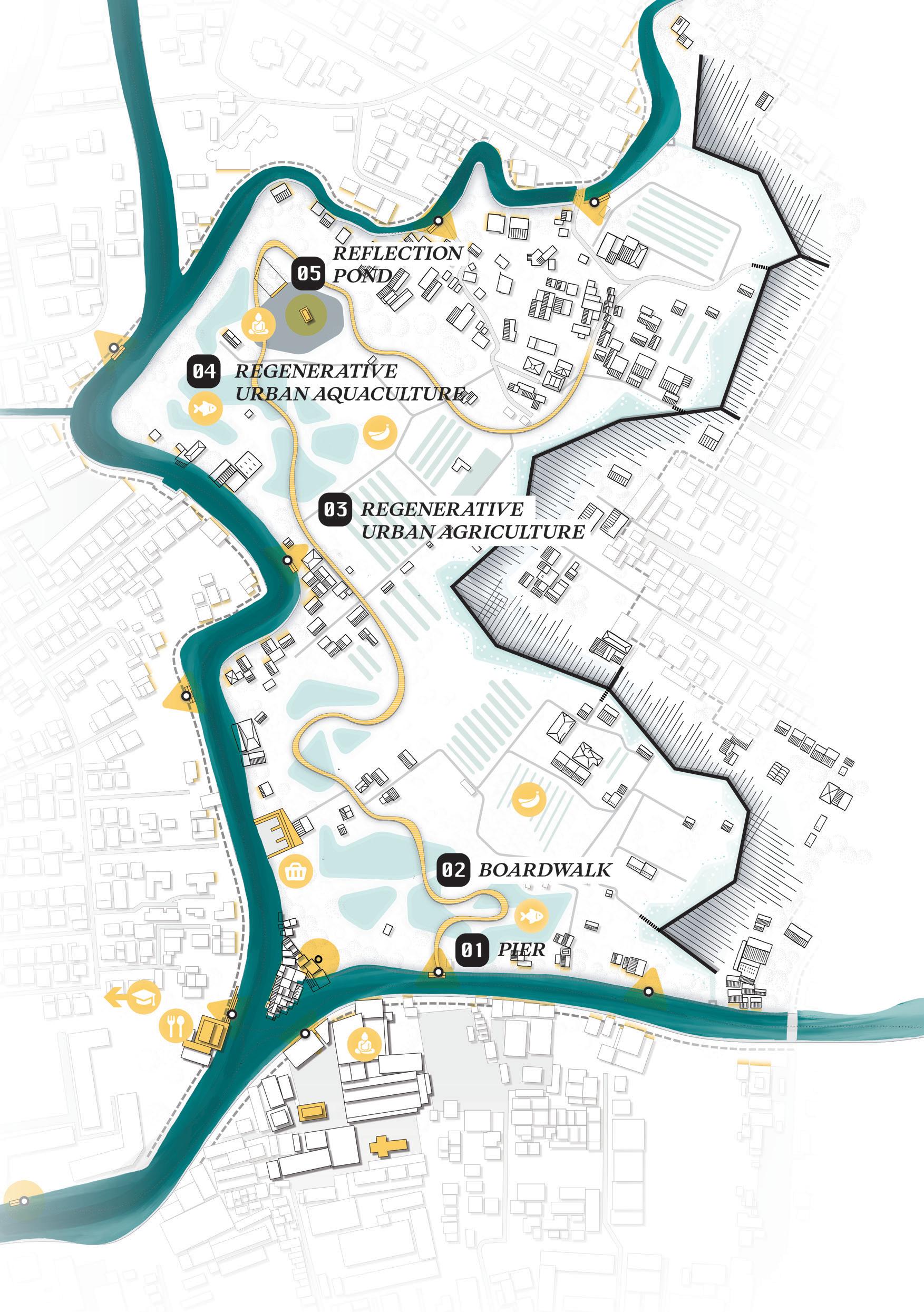

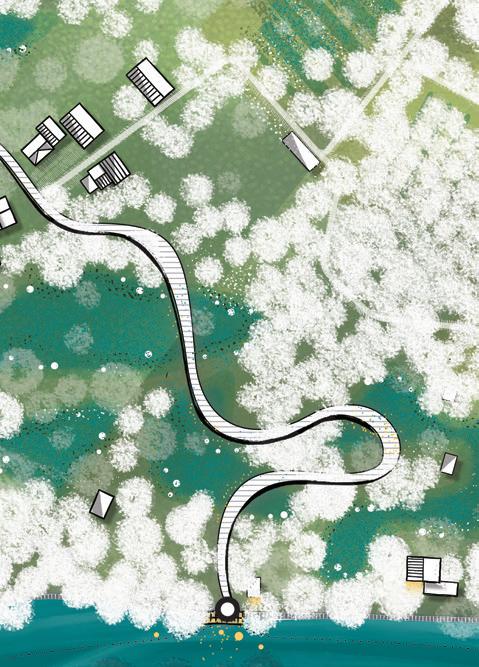

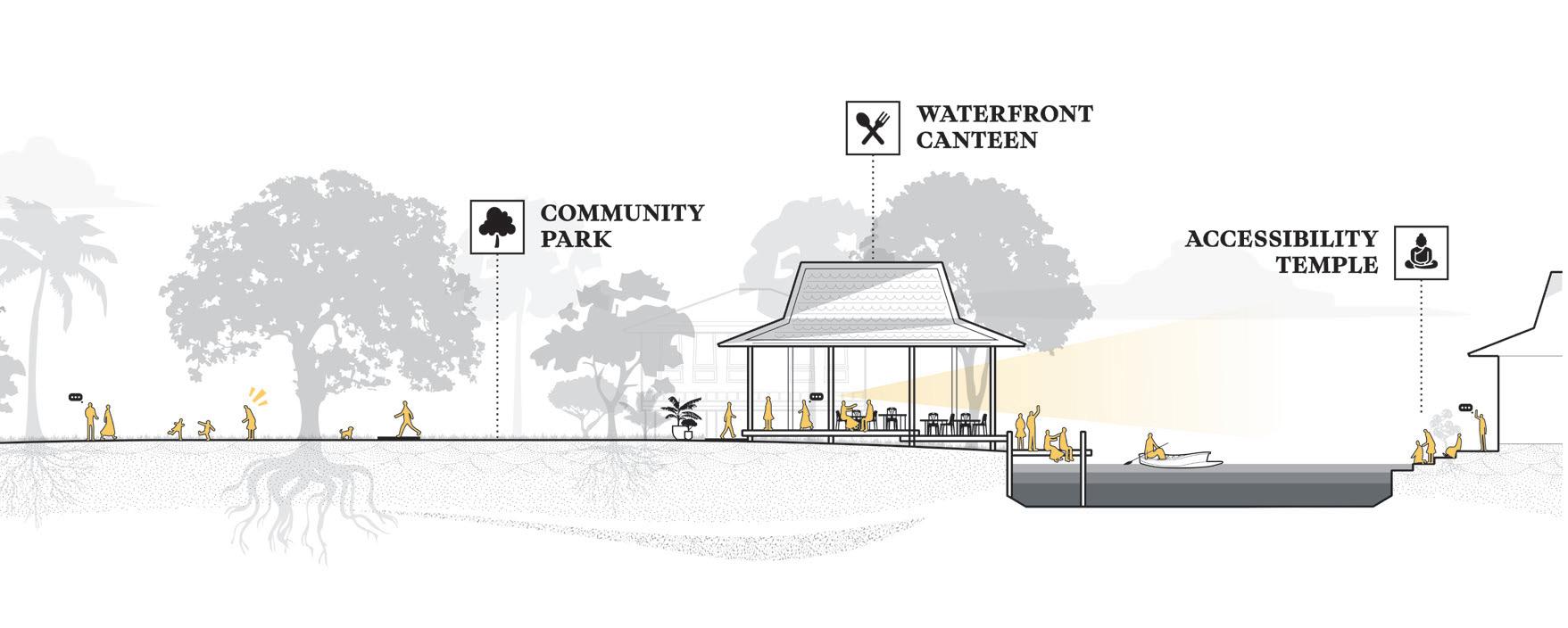

Koh Panyi is the main focalpoint of the wetlands. Across the water temple Wat Mahabut attracts people to worship mae Phra Khanong. From the waterfront canteen at this temple you can also see the gorgous roofs of the unused rice mill across the water. A bit downstream Wat Tai is five minutes away. Also the International Bangkok Prep School is on walking distance.

Only five buildings have to be relocated within the design of this plan. These are indicated red.

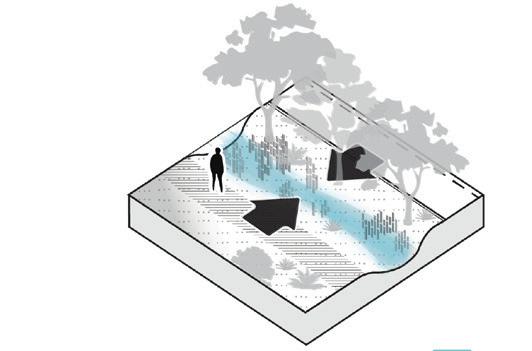

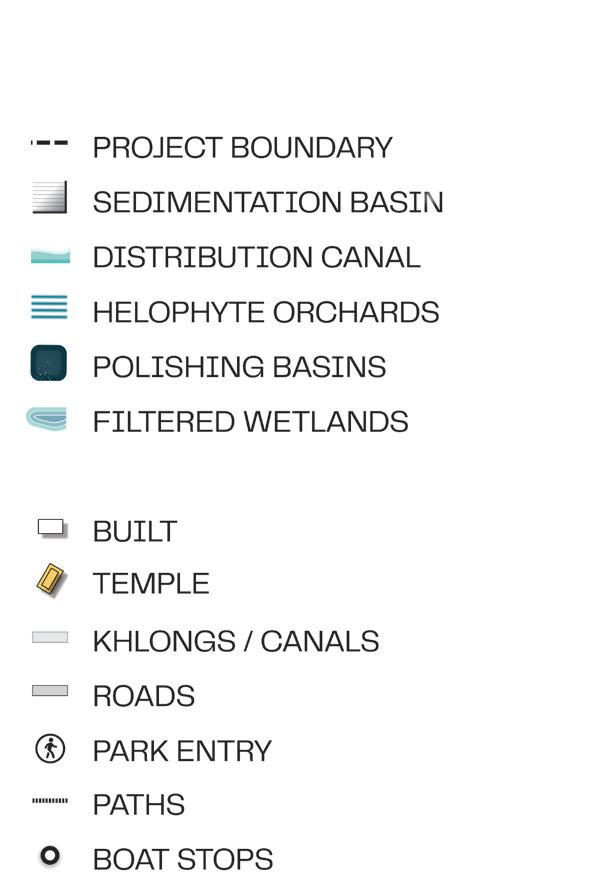

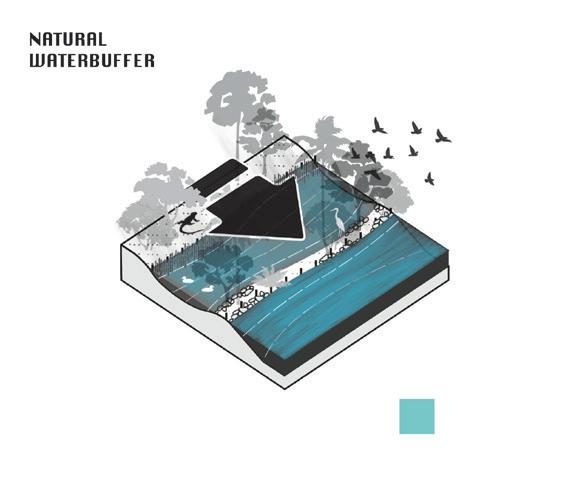

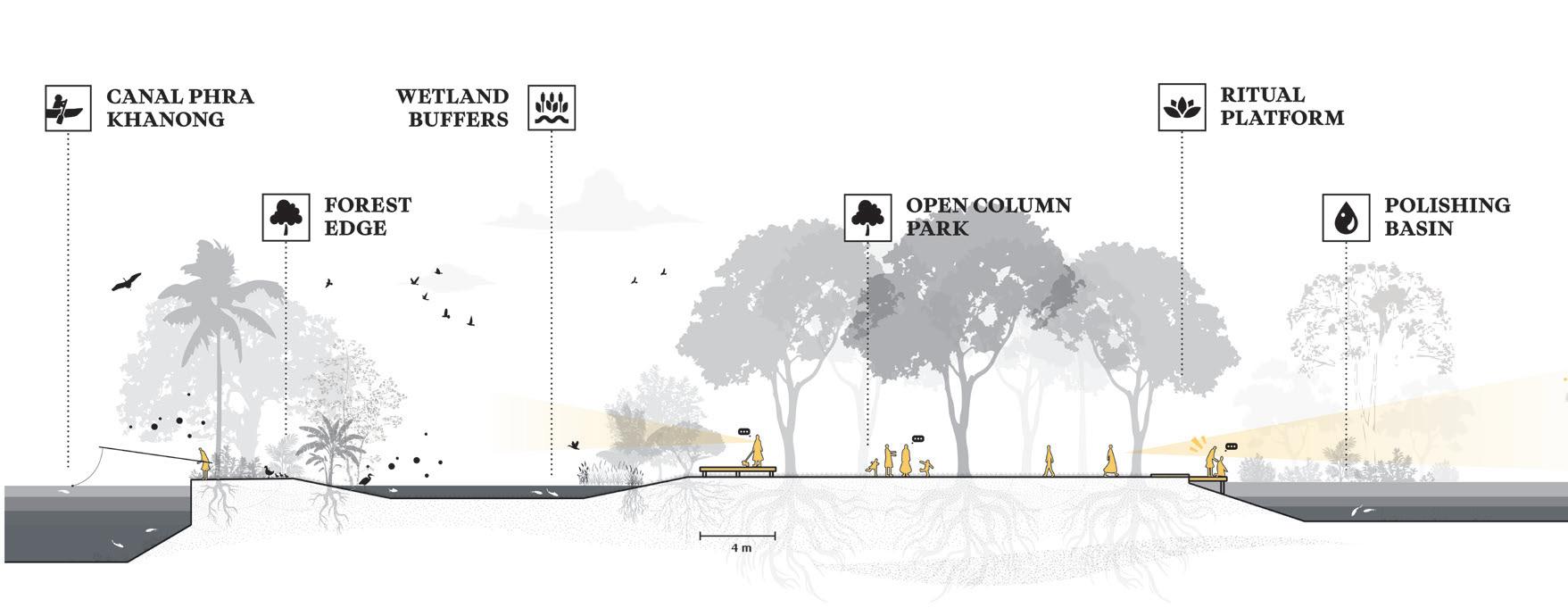

As an alternative proposal to pumping out urban rainwater run-off, the wetlands are designed to buffer this water temporariliy.

1. Through hollow streets water will be conveyed towards the wetlands.

2. A collection basin will collect the first-flush into a concrete basin, excess water flows directly to the river

3. Opposite side of the concrete wall the water is filtrated by a open surface wetlands system which purifies the water for irrigational use.

4. Local farmers can connect their existing systems to the wetland system to use water.

5. Remaining water will be stored in a natural wetland overflow landscape

6. A reflection pond with the clearest water will store water for ritual use.

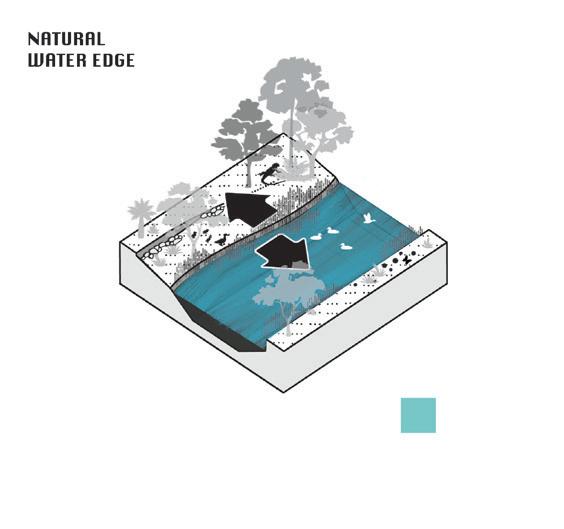

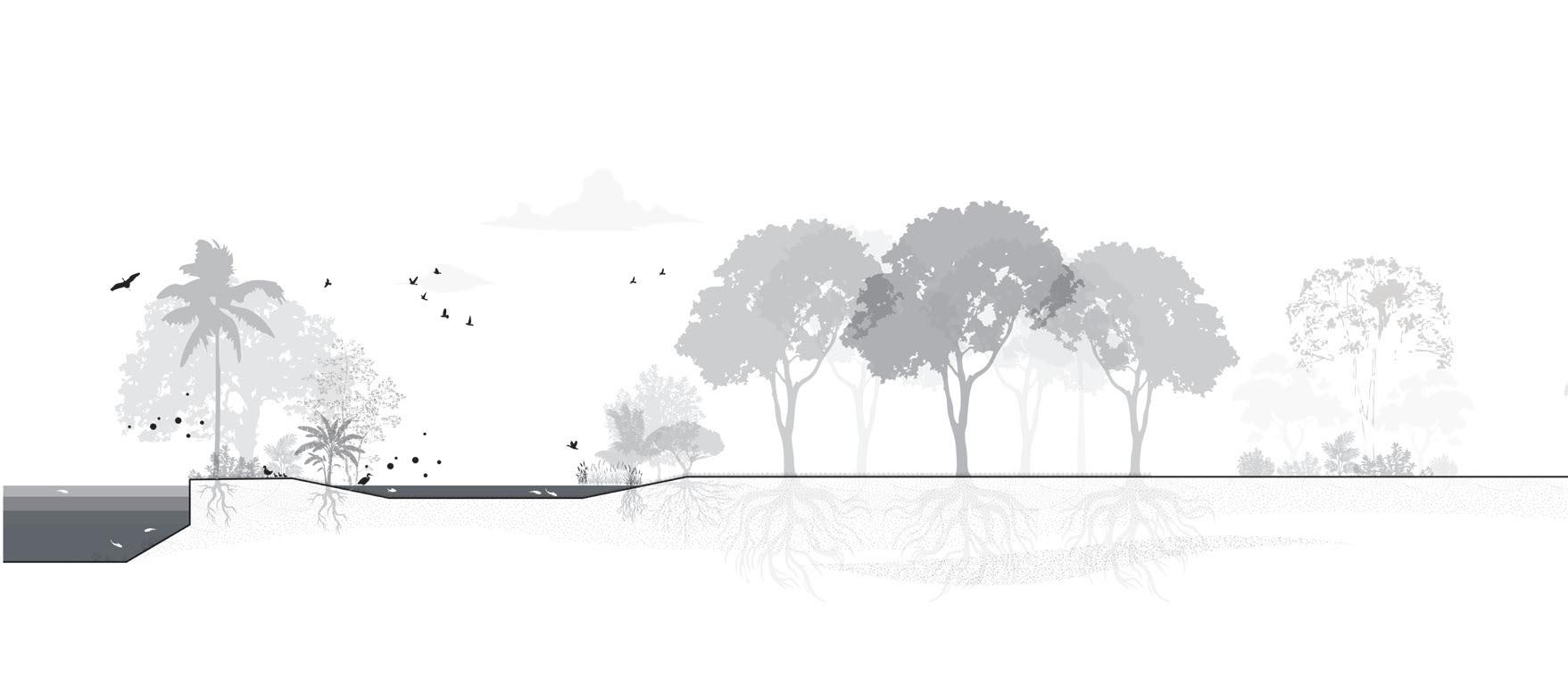

The design explores a dialogue between three natures — wild, cultivated, and designed.

.1 Designed nature: A linear concrete structure separates roads and row houses from a forested interior. Though conceived as functional hardscape, it deliberately invites overgrowth and ecological contrast.

.2 Cultivated nature: This productive landscape blends tropical orchards with traditional irrigation systems, encouraging native farming techniques to merge with natural processes.

.3 Wild nature: What appears untouched is subtly sculpted to evoke natural ideals for recreation and reflection. It buffers built functions while retaining ecological and spatial performance.

The wetlands reveal a dual ownership pattern: predominantly private in the east and municipal in the west.

To preserve their intimate, private character, only subtle, adaptive interventions are introduced, designed to complement earlier structures.

A rigid concrete basin contrasts with a meandering wooden boardwalk that floats above the landscape. This pathway links the pier, reflection pond, and pavilion, as well as the scattered houses across the wetlands.

Occasional decks and a small floating market activate the waterfront, gently puncturing the wetland fabric with moments of social life and exchange.

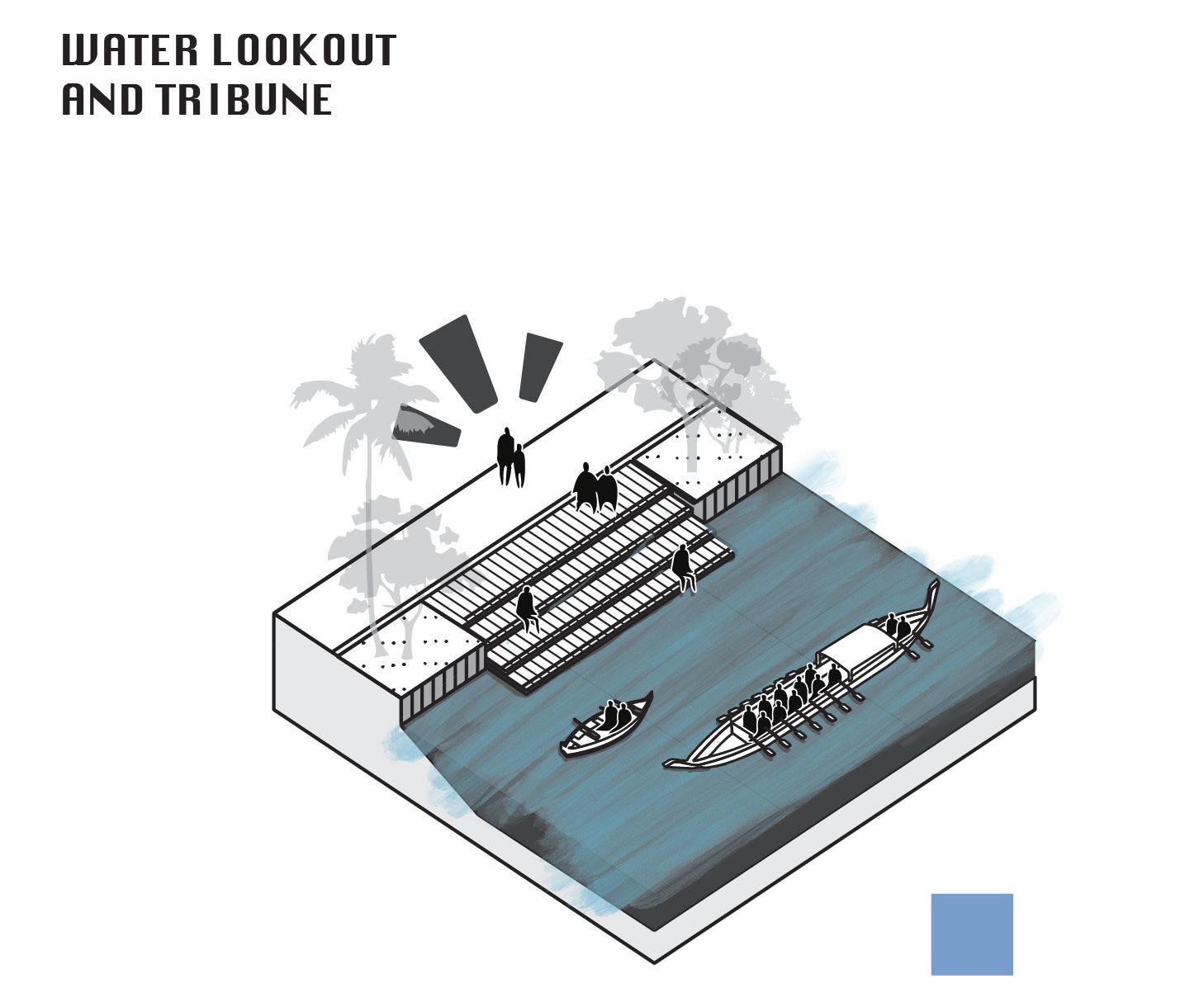

Anchored by the stilted village of Koh Panyi, the historic rice mill, and Wat Mahabut temple, the Khlong Phra Khanong area offers rich spatial and cultural potential.

Its prospects for eco-tourism and water transport position it as a vital link in Bangkok’s urban network, one that could support more locally rooted and community-driven development.

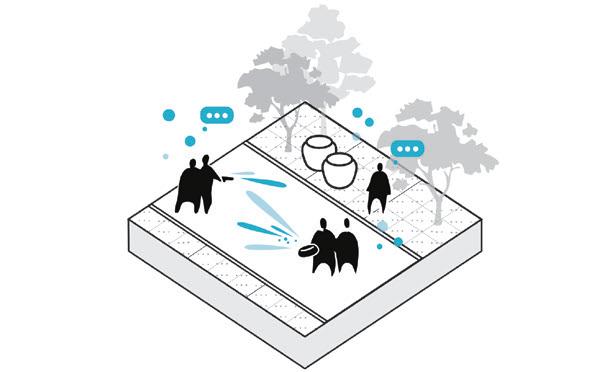

Before elaborating on the design interventions, I want to recall the term geo-choreographies once more. It describes and reminds us of the ways living beings move, inhabit, and interact with landscapes. Throughout this chapter geo-choreographies illustrate how these dynamics translate into specific spatial strategies and interventions.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN |

Enchanting the Watermachine

LIFE & HABITATION

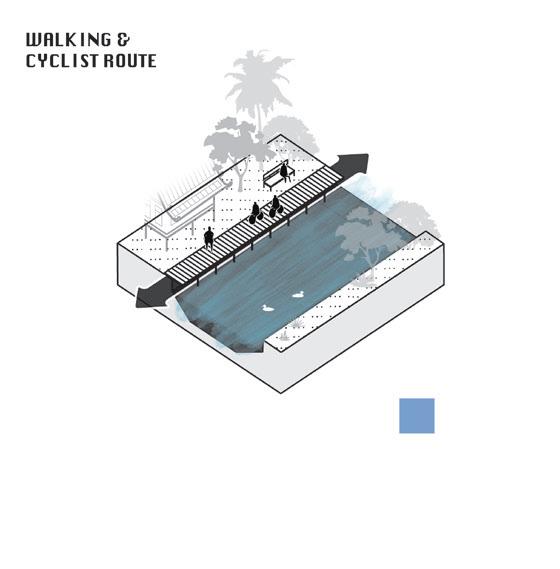

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

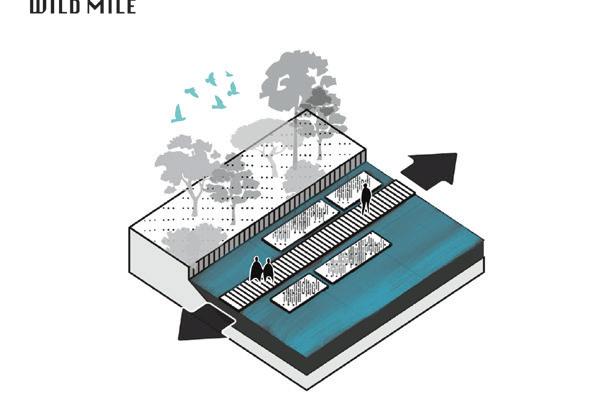

Instead of accelerating stormwater discharge through sewers and pumps, urban rainwater runoff is captured and guided through hollowed roads toward a retention basin. There, water is temporarily stored before gradually flowing through constructed wetlands.

The wetland vegetation remediates pollutants, allowing the cleansed water to irrigate tropical orchards and serve ritual or communal purposes — restoring both ecological and cultural connections to water.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

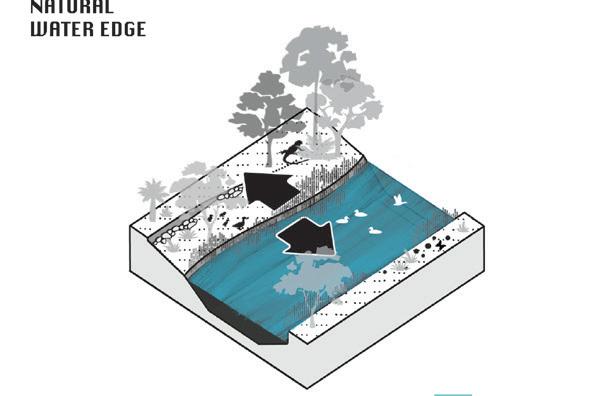

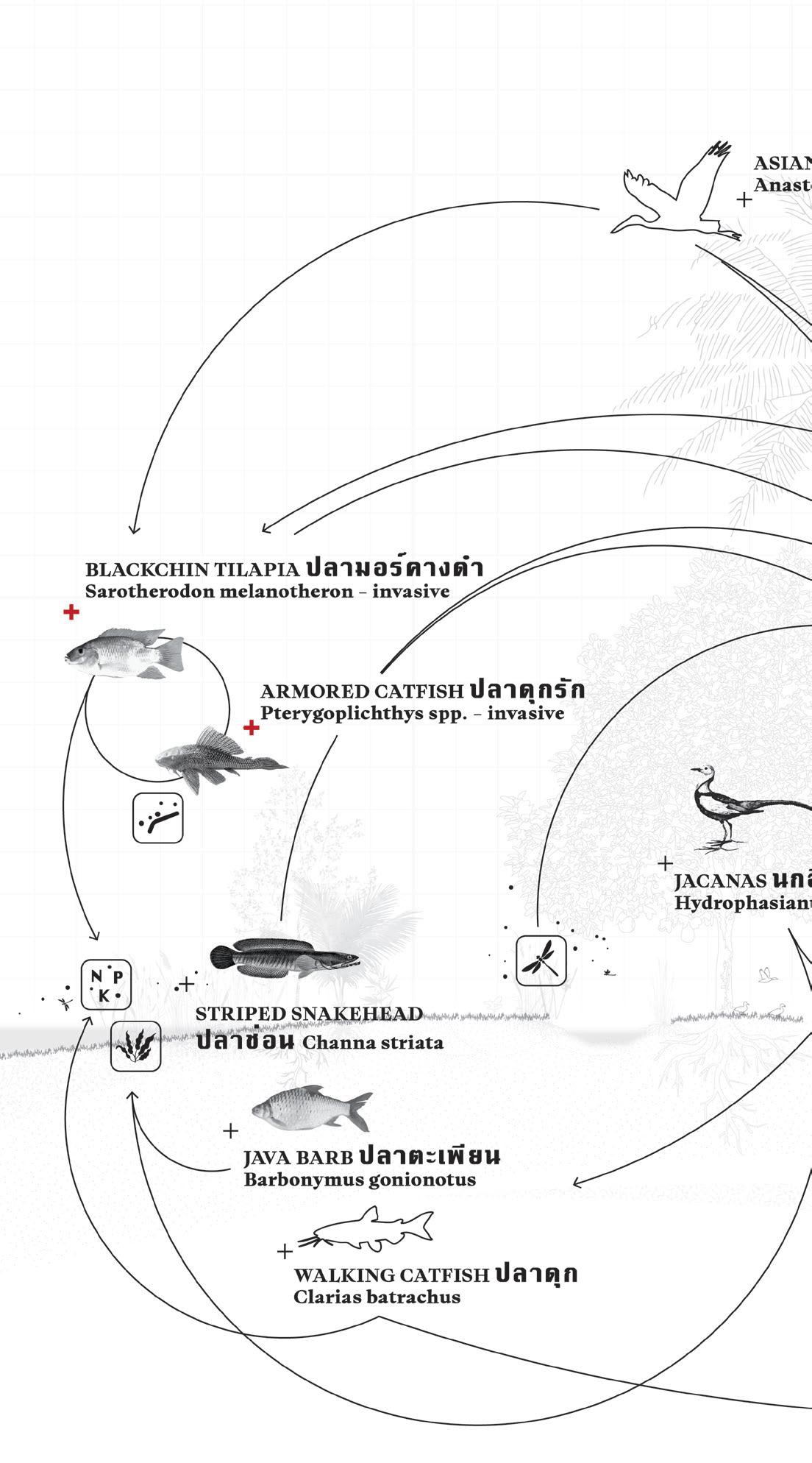

Re-establishing the fluid boundary between land and water nurtures a mosaic of habitats. This living gradient enhances biodiversity, resilience, and natural selfregulation within the landscape to mitigate pests for example

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN |

Enchanting the Watermachine

Re-establishing the fluid boundary between land and water nurtures a mosaic of habitats. This living gradient enhances biodiversity, resilience, and natural self-regulation within the landscape to mitigate pests for example

A wooden boardwalk meanders over the lush, swampy terrain. Excess filtered water from the orchards flows into this natural buffer zone, situated between the waterfront homes and the orchard dwellings. The gentle gradient between land and water creates a rich ecological hotspot that supports both biodiversity and everyday life.

As explored throughout this project, water extends far beyond mobility and subsistence — it embodies atmospheric, emotional, and experiential value. It has the capacity to invite introspection, reflection, and connection.

In this reflection pond, treated water gathers after being filtered throughout the landscape. At its center stands a traditional Thai sala, recalling the spirit of Mae Phra Khanong.

THIS SPACE SERVES AS A MONUMENT TO THE COLLECTIVE IMAGINATION, TRANSFORMING FEAR OF WATER INTO AN EMBRACE OF ITS PRESENCE “

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN |

Enchanting the Watermachine

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

Puncturing the wetland offers opportunities to make these spaces more accessible for local residents while fostering a sense of community ownership.

Such openings can also serve as places of learning and exchange, for instance, teaching urban agricultural practices to students from the nearby international school. By carefully integrating these interventions, the wetland becomes not only an ecological asset but also a social and educational landscape.

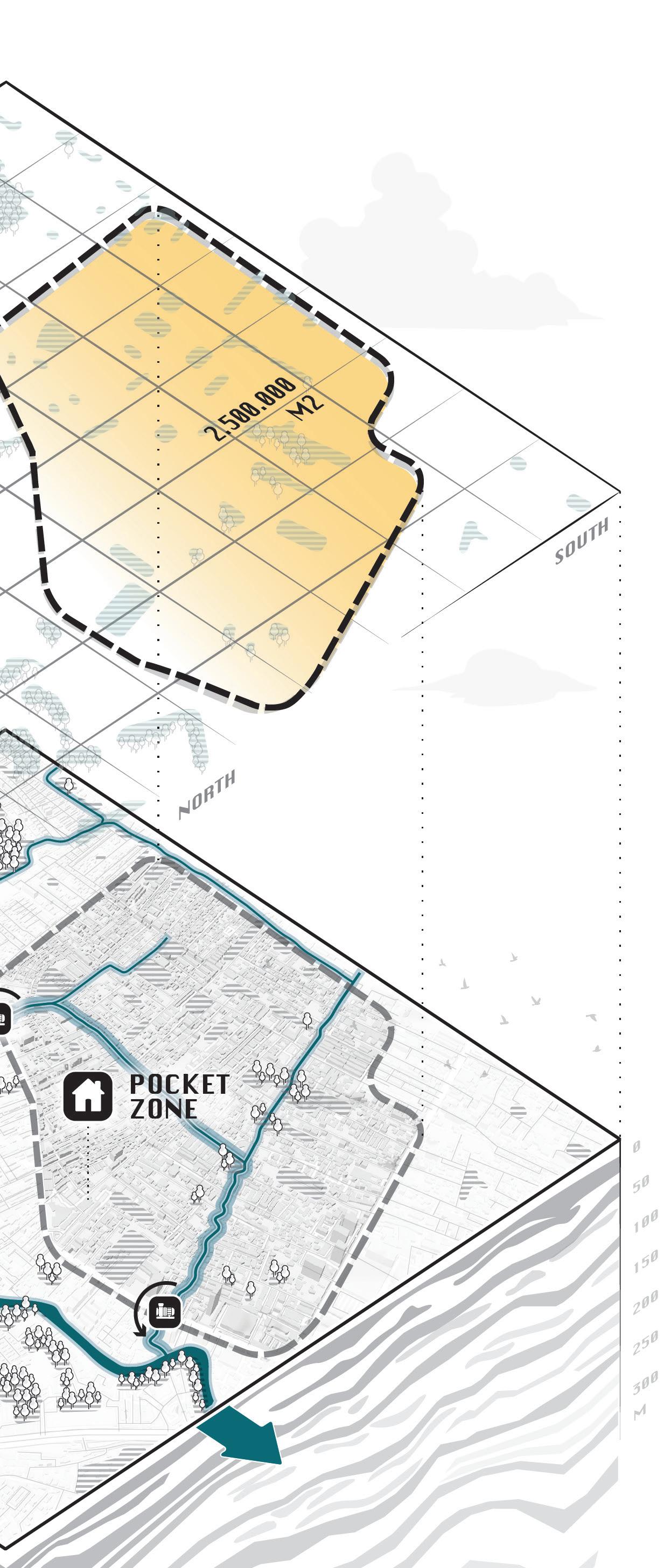

Total drainage area 2.500.000m2 Villa’s, teracced houses, informal houses, tropical orchards

A variety of houses occupy the ten-metre zone along the smaller khlongs. Some are permanent villas that cannot be relocated, while others are traditional Thai houses or informal dwellings capable of adapting to fluctuating water levels.

Yet all are currently concealed behind high walls, isolating the canal from daily life and activity.

All open plots should be actively maintained to reduce further urban runoff. Within the tenmetre zone along the smaller khlongs lies an opportunity to establish a green–blue corridor that benefits the community as a whole.

This shared landscape is not only essential for preventing future flooding, but also creates a healthy, pleasant, and safe environment for living, playing, and resting. It stands as an antithesis to the increasingly uninhabitable streets, where informality is being displaced by traffic efficiency.

To compensate for non-removable plots, selected available plots are repurposed instead. This prevents other functions from capitalising on vacant land and enables the development of a cohesive green–blue network.

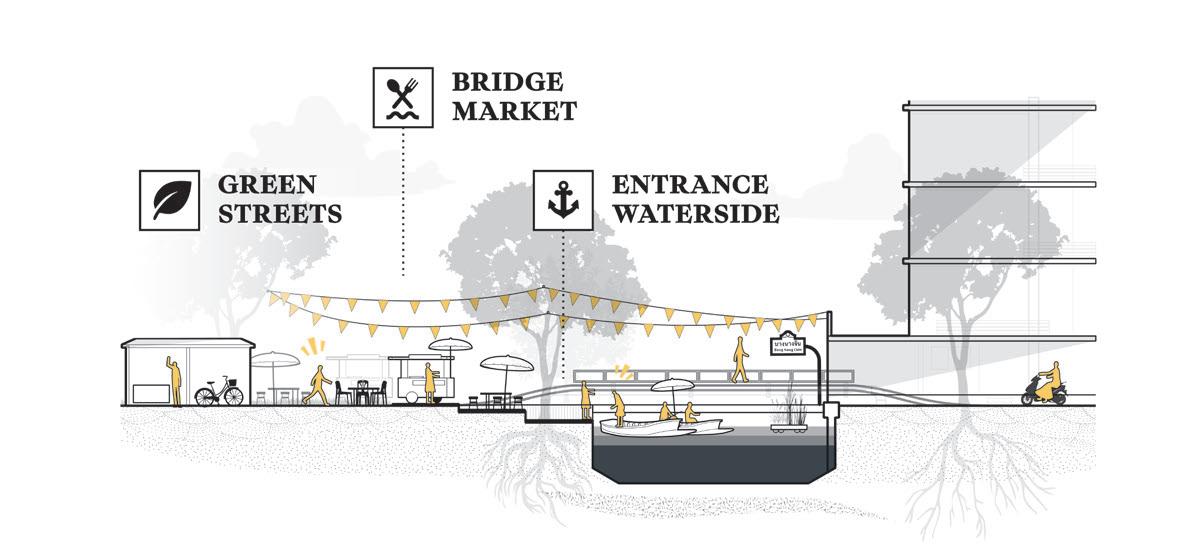

Historically, trade flourished along Khlong Phra Khanong due to its strategic connection with the Chao Phraya River and the waterways of the hinterland.

Further upstream, as the canal branches into smaller channels, the atmosphere gradually shifts toward agricultural and residential use.

Here traditional intimacy between water, home, and community are restored. Along the canal, new Thai-style houses are built in harmony with the landscape, framing a shared park at the center and a temple along the edge. The park serves as a communal heart, a lively space where children play, residents gather, and water becomes part of daily life again. A small mooring area connects homes to the canal, while a waterfront canteen welcomes both the local community and visitors from the nearby temple.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN |

Enchanting the Watermachine

LIFE & HABITATION MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE

COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

LIFE & HABITATION

MOBILITY

SPIRIT & CULTURE COMMODITY

UTILITARIAN

QUALITY OF LIFE

INCREASE ADAPTATION

STRONG ECONOMY

Instead of dividing the city, water can become its social connector. By opening up private riverfronts, condominium complexes can blend into the city’s living fabric, creating spaces shared by all.

Floodable banks and multifunctional platforms allow the water’s rhythm to shape daily life, where a floating market nearby the pumping station brings back vibrancy, offering a place to eat, trade, and meet. Here, water reconnects rather than separates, stitching together the city’s fragmented edges.

Traditional Thai architecture is amphibious by nature. It responds gracefully to changing water levels and creates comfortable microclimates amid rising urban heat.

A peaceful green path weaves through the city, a place to walk, play, and breathe away from the roar of engines.

Along the way, sala offer shade and stillness: places of pause and affection, where care for a place becomes care of the place

Where bridges cross the canals, they can become places of encounter, connecting neighbourhoods and restoring everyday intimacy with the water.

Within this hyper-urbanised landscape, the preservation of tropical orchards is vital. They keep cultural memory alive, teaching future generations while nurturing Bangkok’s ecological and spiritual connection to its land and water.

Counterintuitively, the greatest flood risk now lies not in the wetlands but in the adjacent pockets, which have lost their resilience to wet conditions. As mentioned earlier, the idea of anti-fragility shows how small-scale water dynamics can generate regenerative effects that ultimately reduce vulnerability to large-scale events. From this lens, the pockets require the most urgent intervention, making them central to the project’s phasing.

Yet the wetlands offer something equally important: cultural leverage. By breaking with the entrenched habit of defensive water management, the wetlands can model an alternative approach, one that is tangible, relatable, and capable of inspiring a broader shift in how we imagine renewed relationships with water.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine

THIS APPROACH SHOWS HOW EMBRACING ALTERNATIVE WATER STRATEGIES AND SLOWING WATER METABOLISMS CAN RESTORE LOST GEO-CHOREOGRAPHIES

BANGKOK STANDS ON THE FRONTLINE OF CLIMATE COLLAPSE. RATHER THEN IMPORTING WESTERN SOLUTIONS, I SEEK TO REVEAL THE LOCAL WISDOM AND WATERCULTURES THAT ONCE DEFINED THIS REGION

IT’S MUCH MORE THE WAY WE DEAL WITH CLIMATE CHANGE THAT THREATENS LOCAL CULTURE, TRADITIONS AND OUR LIFESTYLES THAN CLIMATE CHANGE ITSELF.

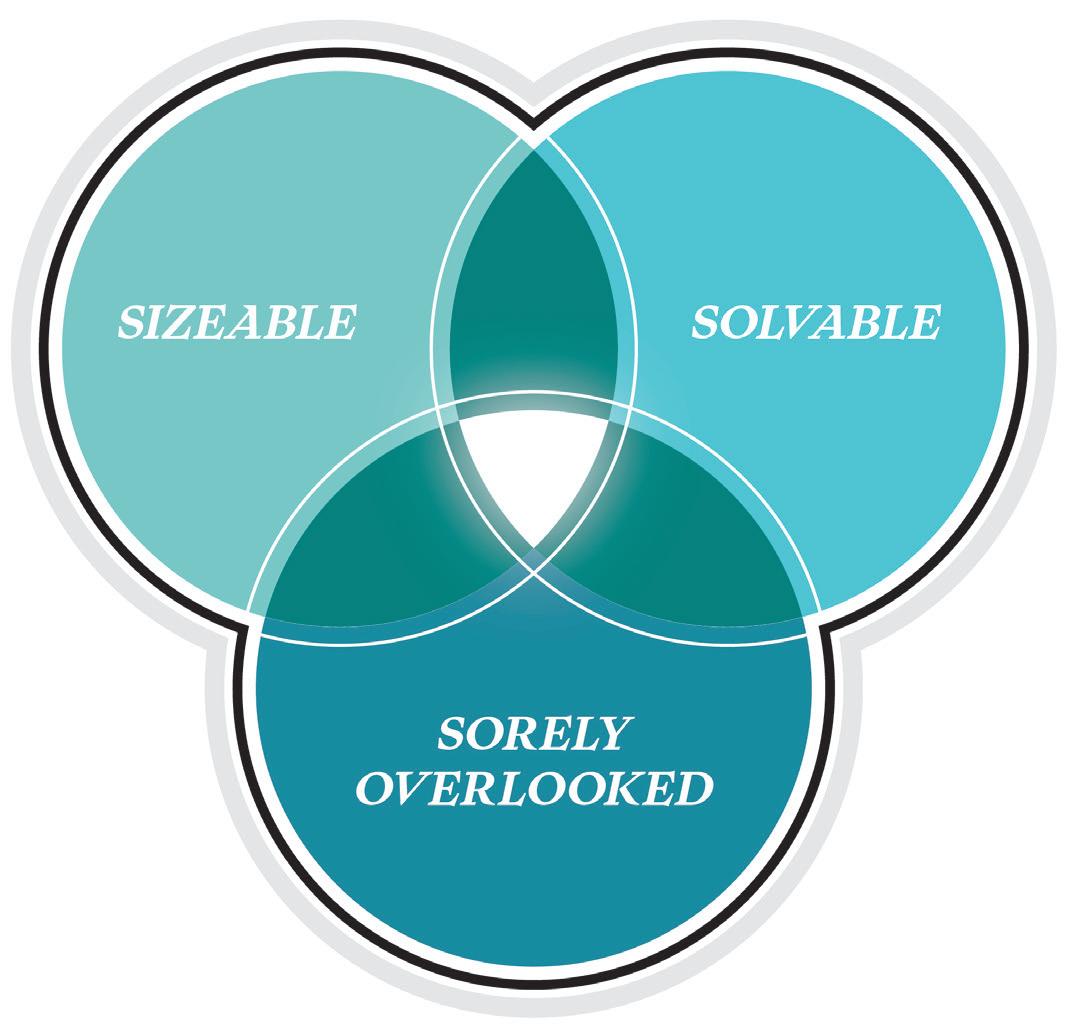

When starting my graduation process, I faced a fundamental choice: to ground my work in my hometown of Rotterdam or to follow my ancestral roots to Bangkok. After discussions with landscape professionals, I chose the latter. This was not an easy path, gathering GIS data and connecting with professionals remotely would be difficult. However, my mentors noticed my deep curiosity for the challenges Thailand faces and encouraged me to pursue what Rutger Bregman calls moral ambition: to seek a problem that is both solvable and significant, overlooked yet urgent.

ORIENTATION & EXPLORATION

This perspective, shifting between Thai and Dutch cultures, felt meaningful. Coincidentally, the Water as Leverage program was launched during this time, creating a collaboration between Dutch and Thai institutions. This convergence offered an invaluable opportunity to align my work with ongoing transitions toward urban water resilience.

My research moved between landscapehistorical analysis and the contemporary water challenges facing Bangkok, exploring how Thai culture has long been shaped by its relationship with water. While delta systems worldwide share physical traits, it is the cultural adaptations that fascinate me most. What I take away most strongly from this research is that it’s not climate change itself that most threatens local culture and lifestyles, but rather the way we respond to it.

ANALYTICAL & STRATEGIC

DESIGN & REFLECTION

Although this project has primarily put attention to the potential of local knowledge and added value slowing water metabolisms, the urgency of action cannot be overstated. As mentioned in chapter one Bangkok finds itself at an fundamental tipping point as current watermanagement strategies have proven inadequate to serve the majority of humans and non-humans living in Bangkok.

While I am aware the use of popular rehtoric in embracing Thai culture the proposed interventions cannot be mistaken for mere beautification. My argument is that the functionality of Thai architecture, rituals and traditions extend way beyond its aesthetics.

Therefore, I would like to once more raise the urgency to the watercrisis at hand. The interventions are presented not as a remote possibility, but as an essential roadmap into an inevitable future as top-down approaches seem to be insufficient.

This became clear during my fieldwork. Urban water no longer plays a vital role in daily life the khlongs evoke disgust or indifference, not dialogue. This cultural detachment mirrors the broader climate discourse and is the direct result of Bangkok’s modern approach. Following the great flood of 2011, the city doubled down on a mechanistic, land-based strategy, trapping itself in a “lock-in” that has severed its cultural intimacy with water.

I call this rigid, technocratic ideology the “watermachine.” This approach, often adapted blindly from Western science, imposes a binary (dry-wet) landscape and has no regard for the “geo-choreographies”, the fluid, adaptive movements emerging from the underlying landscape. This critique is not just spatial; it’s social.

As Jerome Withington highlights, these concrete walls create deep inequality. The result is an impoverishment of Thai culture, which is hollowed out and reduced to a nonfunctional, touristic decorum. This flawed pursuit of “overcoming” flooding only sets a wave of further mechanization in motion. As my research progressed through fieldwork and analysis I uncovered the deeper meaning and relation of ritual and culture taking root in the local landscape. With mapping this the contrast of the era following the great flood of 2011 resulted in a profound cultural detachment that manifested following Bangkok’s mechanised approach.

To conclude, Bangkok is trapped in a manifest landbased lock-in that has severed its cultural intimacy with water. As a landscape architect, this realization shifted my focus: before local rituals and practices could be ‘used’ or ‘re-introduced,’ the fundamental relationship itself had to be healed. The challenge was not merely ecological, but profoundly perceptual and emotional. Therefore, my research question evolved into a more fundamental one.

GRADUATION PROPOSAL QUESTION

HOW CAN LOCAL RITUALS AND CULTURAL PRACTICES BE USED TO ENHANCE AMPHIBIOUS URBAN ECOLOGIES IN BANGKOK?

The central challenge here is linguistic and cultural. It was Andri Snær Magnason’s On Time and Water that provided a pivotal insight. He reveals how our modern language fails to grasp the magnitude of climate change; what remains ineffable becomes vulnerable to inaction. This linguistic disconnect exposes the inadequacy of purely instrumental solutions.

This led me to my core thesis: our responses can no longer be merely technical. Design must bridge the gap between data and experience, becoming a narrative tool that translates urgency into meaning. This is why I embrace the power of myth, belief, and ritual. This is not nostalgia, but a critical framework. The effects of climate change are not “mythical” in the sense of being untrue;: rather, the scale of this crisis, where geological changes now unfold in a single lifetime, is itself of mythical proportions and demands a response that can speak to this deeper, cultural level.

In formulating an alternative, my work aligns with nature-based solutions and a water-and-soilled approach, similar to the Resist+Discharge and Delay+Store framework from Rebuild by Design. But more than just physically enhancing the landscape, I advocate for the ethereal relevance of how we integrate these strategies. That is where re-enchanting plays a pivotal role, sprouting from a vibrant community and rooted stewardship.

For this, I adapt the concept of geo-choreographies from Gilles Deleuze. He used it to describe how bodies move through and are shaped by environments, often finding “lines of flight” to escape rigid systems. In the context of climate collapse, I re-interpret this: my focus is not on how bodies escape rigid systems, but on how our human systems have themselves become a rigid, geological force the “watermachine” that overwrites the fluid choreographies inherent to the landscape.

My method draws inspiration from Julia Watson’s LOTEK, which re-values the local, adaptive strategies—like traditional Thai architecture—that “colonial-capitalismdriven technologies” have displaced. In this, I attempt to translate professional tools into images and stories intelligible to a broad public, not just for Thailand, but to inspire mutual learning for the Dutch landscape approach.

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting

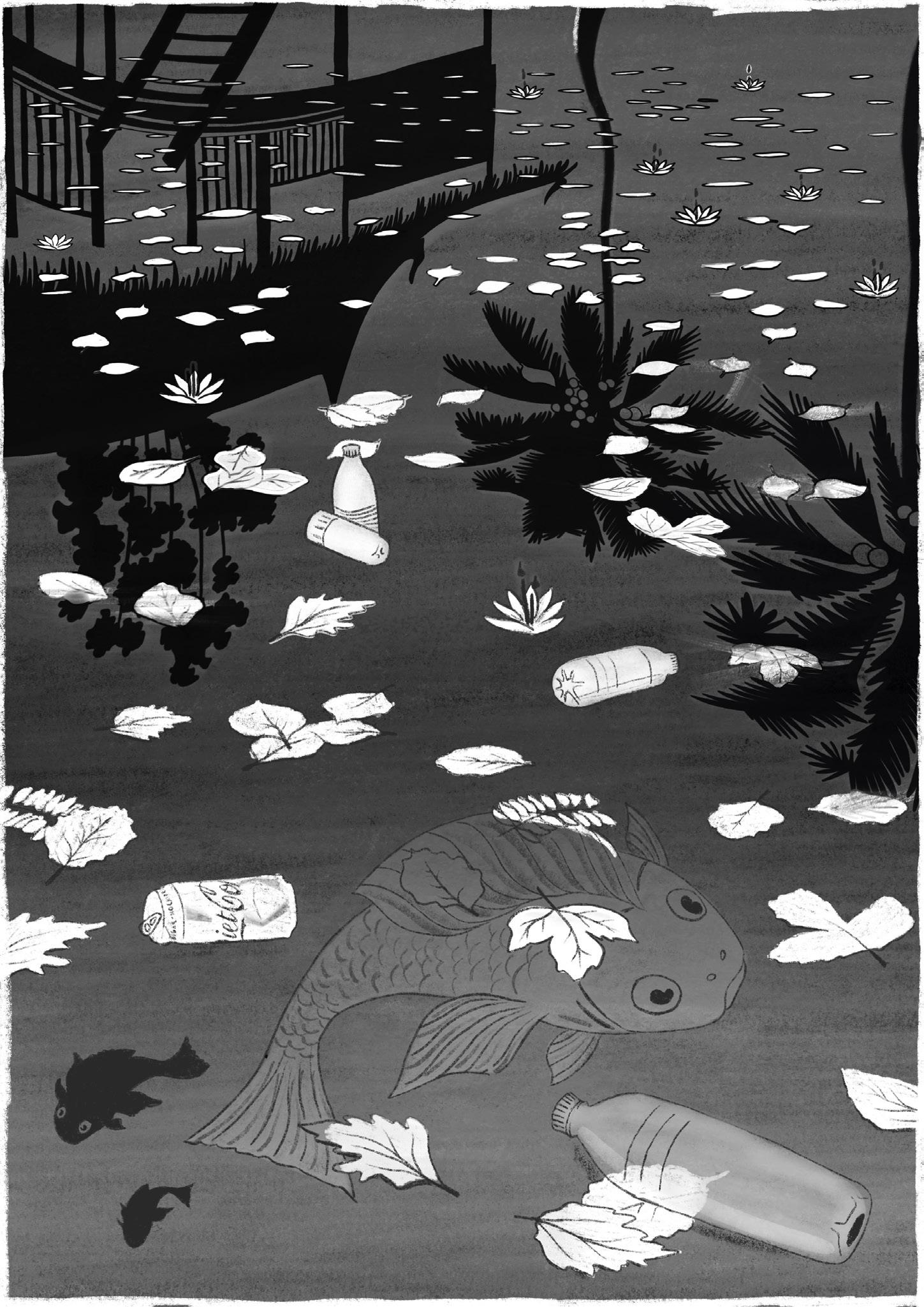

THIS IMAGE EVOKES THE LAYERS THROUGH WHICH WE PERCEIVE THE ENVIRONMENT. THE WATER’S SURFACE HOLDS A CONTRADICTION OF BOTH RITUAL AND POLLUTION. BENEATH IT DRIFTS A SUBMERGED WORLD OF LIFE THAT ENDURES IN SILENCE. ON THE SURFACE, REFLECTED IN FRAGMENTS, SHIMMERS A CULTURAL MEMORYOF LOST AFFECTION...

Overcoming the profound cultural detachment rooted in the land-based lock-in is a significant limitation which determines the success of an “affective approach”. Moving beyond the deep-seated disgust or indifference of Bangkokians towards the khlongs remains a major uncertainty.

While I have proposed three breakthroughs in this lockin, a swift abandonment of defensive strategies will not occur in the short term. With the wetlands, I have shown further mechanisation can be averted, preventing a waterbed effect that necessitates further mechanisation in places that have retained water-affective lifestyles.

Further, I have identified stakeholder fragmentation, with more than fifty institutional stakeholder parties involved in Thai water management. This institutional siloing and dominant top-down approach presents a massive barrier to implementing a holistic landscape strategy.

Therefore, I have appointed three specific actors to enforce a breakthrough while also advocating for a bottom-up approach from local residents, entrepreneurs, and NGOs. This is an essential element, as the interventions are proposed on a combination of municipal but primarily private-owned plots.

Finally, while my ancestral roots trace to Thailand and I frequently visit Bangkok, I am not native to the place and remain an outsider. In the execution of this thesis, I have overcome this by maintaining several contacts with experts living in Thailand and landscape architects in Bangkok. My goal was not to bear exotic Western knowledge, but to learn from the values, perspectives, and approaches to water and landscape throughout history. With this, I hope to have contributed a fresh perspective that holds respect for place and culture.

the Watermachine

The findings of this thesis open a path for future action that moves beyond mechanical change and instead proposes a fundamental shift in perspective. To make the previously outlined strategies for design, policy, and research concrete, they can be distilled into six core principles. These principles are not isolated steps but an integrated framework for action.

This framework is intended as a direct antidote to the “watermachine”. It provides a new language for reenchanting degraded landscapes by valuing “affective design,” implementing “delay and store” policies, and blending global methodologies with local wisdom. These six points are the conceptual guideposts for cultivating “amphibious intimacy.”

01 02 03

Future design must move beyond function to actively re-enchant the landscape. This means designing for affection, myth, bealief, and ritual by creating spaces like salas (places of pause) and restoring cultural practices that build “care.

Future design must embrace a hybrid approach. This involves physically restoring amphibious architecture for both humans and non-humans while socially weaving these spaces together with leisure and informality, such as in community-led upgrades.

Future policy must recognize that purely technical, “resist and discharge” strategies are culturally destructive. The goal is to stop further mechanisation that severs environmental intimacy and transforms vital waterways into dead infrastructure.

The core policy alternative is to ‘delay and store’ water. This means preserving urban wetlands as showcases of anti-fragility and transforming canals from infrastructural backwaters into vital, slow-moving social and ecological arteries.

Future research must focus on this reciprocal loop. It must provide a model for blending “global north” (Dutch) methodologies with “local wisdom,” studying how this blend can actively cultivate and measure a renewed “amphibious intimacy.”

Future policy must be integrative and inclusive, breaking down silos. This means mandating that private waterfronts become “social connectors” and ensuring community upgrades actively restore environmental intimacy, not just provide housing.

My time at the Academy of Architecture has been an incredible privilege. I am grateful to have been exposed to the immense diversity of knowledge, perspectives, and the unique passion of my fellow students and mentors.

I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my mentors and tutors. Thank you for sharing your invaluable ideas and enthusiasm throughout this project, whilst challenging my design thinking.

Mirte van Laarhoven / mentor

Lada Hršak Rens Wijnakker

For this project specifically, I am also deeply thankful to the numerous people I met in both Bangkok and the Netherlands. My gratitude extends from the experts at the Water as Leverage meetings to the many individuals who shared their insights during spontaneous talks on my field trips.

Finally, my deepest gratitude is reserved for my family and friends, who have been beyond supportive, every single day, Thank you!

Image KESSEL, D. 1951

Data KIRMA, J. 2023

1 ORIGINS

Image VIEW OF BANGKOK JOHN HEAVENSIDE, 1828

Data STUDIO MARAS 2023

Data MOORMANN & ROJANASOONTHON, 1967

Data E.O. WILSON, WELLER, HOCH & HUANG, 2019

Image LA TORRE, F. 1961

Image PUNPAIRO, P. 2010

Image THAILAND POST () VIEW OF JUDEA, VINGBOONS, J. 1665

Image TANYAPURA PHUKET, 2025 & AMANTA, 2025

2 CRISIS

Image PLANES OF YONDER, 2025

Image KESSEL, D. 1950 & KOSNIO 2025

Data LANDPROCESS, 2023

Data WAL MEETING II 2024

Images THE ATLANTIC 2011

Data WAL MEETING II 2024

Data TEBAKARI, T. 2020

Images CODI

Data BKKBASE (for elevation) MARRON IN. OF URBAN MAN. (for urban growth)

3 DIALOGUES

Image SILPA MAG.COM, 1989

5 REFLECTION

Image DALL-E, 2024

Image BOONSOM 2013

Inspiration ESSCHER, M.C. 1955

Images LA TORRE, F. 1961

Book 100 WORDS FOR WATER: A PROJECTIVE ECOSOCIAL VOCABULARY, 2025

Book Andri Snær Magnason ON TIME AND WATER, 2019

Book Baker, C. & Phongchaichit, P. A HISTORY OF THAILAND, 2014

Book Cornwel-Smith, P. & C. Goss, J. VERY THAI: EVERYDAY POPULAR CULTURE, 2013

Book Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. A THOUSAND PLATEAUS, 1987

Book Gilles Clement GARDENS, LANDSCAPES & NATURE’S GENIUS, 2024

Book Julia Watson LO-TEK : DESIGN BY RADICAL INDIGENISM, 2019

Book Kasemsook, A., Tovich, S. et al BANGKOK ADAPTIVE CITY 2045

Book Laura Cipriani (CO)DESIGNING HOPE: AQUEOUS LANDSCAPES IN TRANSITION, 2025

Book Rahmann, H. & Walliss, J.

THE BIG ASIAN BOOK OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE, 2020

Book Ten Brummelhuis, H. KING OF THE WATERS, 2005

Report 100 Resilient Cities

RESILIENE STRATEGY BKK, 2017

Report Landprocess

BANGKOK THE CITY OF THREE WATERS – HOTSPOTS ANALYSIS FOR WATER AS LEVERAGE, 2023

Report The World Bank

THAI FLOOD RAPID ASSESSMENT 2012 and other reports provided by LANDPROCESS and the WAL MEETING II 2024

Fonts PP Telegraf / PP Writer / Krungthep

BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN | Enchanting the Watermachine