Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1. Foreword

The term “catalysis” was coined by Swedish scientist Jons Jakob Berzelius in 1836 [1]; he described the process as adding a catalytic power to a chemical reaction to accelerate it while itself is not consumed.

Berzelius stated [1]:

Many bodies have the property of exerting on other bodies an action which is very different from chemical affinity. By means of this action they produce decomposition in bodies, and form new compounds into the composition of which they do not enter. This new power, hitherto unknown, is common both in organic and inorganic nature; I shall call it catalytic power. I shall also call Catalysis the decomposition of bodies by this force.

Currently, catalysis is more specifically defined as the acceleration of a chemical reaction assisted by a species known as a catalyst. A catalyst operates by providing a mechanism with a different transition state of a lower activation energy (Ea) in comparison with those of the original mechanism. Through such an alternate pathway, more reactant molecules will have enough energy to reach the transition state and surmount the energy activation barrier, letting them react and transform into the product molecules (Fig. 1.1).

The process can be described by the Boltzmann distribution equation (Eq. 1.1 ):

(1.1)

where Ni and Nj are the numbers of particles corresponding to energy states Ei and Ej, respectively, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is absolute temperature.

In addition, one can explain it based on the Arrhenius law (Eq. 1.2), which says lower activation energies lead to higher kinetic rate constants, which in turn result in faster reactions:

(1.2)

where k is the kinetic rate constant (not to be mistaken by the Boltzmann constant), A is a preexponential factor, Ea is the activation energy, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

Heteropolyacids as Highly Efficient and Green Catalysts Applied in Organic Transformations. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-88441-9.00006-5

Copyright © 2022 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

reactants as well as the external conditions of the reaction. The study of catalysis is theoretically of interest as it reveals a plenty of information regarding the very nature of a chemical reaction; from a practical point of view, the study of catalysis is significant since many industrial processes rely on catalysts to be successful. The peculiar phenomenon of life would be absolutely impossible without the biological catalysts generally known as enzymes.

In general, a catalyst combines with the reactants but eventually is regenerated. Therefore, the amount of the catalyst remains intact. As the catalyst is not consumed in the course of the reaction, each catalyst molecule will be able to catalyze the transformation of many reactant molecules. For highly active catalysts, the number of the reactant molecules which are transformed by one molecule of the catalyst can be as large as several millions per minute.

When a certain substance or a combination of substances go through two or more parallel reactions to afford different products, it is possible to control the distribution of the products by applying a catalyst and selectively accelerating one reaction with respect to the other(s). One can make a particular reaction occur to such an extent that practically excludes another by selecting a suitable catalyst. Many important cases of catalysis applications are based on selectivity of this type.

Since a reverse reaction can take place by inversion of the steps comprising the mechanism of the forward reaction, the catalyst for a certain reaction is able to equally increase the reaction in both directions. In other words, catalysts do not influence the equilibrium position of a reaction; they only affect the rate at which an equilibrium is reached. Seemingly exceptions to this general rule are reactions in which one of the products is a catalyst as well. Such reactions are known as autocatalytic.

In addition, there are cases in which the addition of an extra substance, known as an inhibitor, reduces the rate of a reaction. This process, referred to as inhibition or retardation, is sometimes known as negative catalysis. Occasionally, concentrations of the inhibitor can be much lower than that of the reactant. Inhibition can be the result of:

(1) a reduction in the concentration of one of the reactants due to the formation of complex between the reactant and the inhibitor;

(2) a reduction in the concentration of an active catalyst (termed as the poisoning of the catalyst) due to the formation of complex between the catalyst and the inhibitor; or

(3) termination of a chain of reactions upon the annihilation of the chain carriers by the inhibitor.

1.3. History

The word “catalysis” was taken from the Greek roots kata- (down) and lyein (loosen). It was coined by the great Swedish scientist Jöns Jacob Berzelius in

1835 in attempt to address a group of observations by other chemists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Among those observations were the improved conversion of starch into a sugar upon the addition of acids by Gottlieb Sigismund Constantin Kirchhoff; Sir Humphry Davy had observed that platinum accelerated the combustion of various gases; the stability of hydrogen peroxide in acid solution, while it decomposed in the presence of alkali and metals like manganese, platinum, silver, and gold; the oxidation of ethanol to acetic acid was accomplished in the presence of finely powdered platinum. The species that promoted such reactions were called catalysts. Berzelius supposed that a particular unknown catalytic force was behind these processes.

In 1834, Michael Faraday studied the capability of a platinum plate to achieve the recombination of gaseous oxygen and hydrogen (the products of water electrolysis) and deceleration of that recombination in the presence of other gases like carbon monoxide and ethylene. Faraday believed that an absolutely clean metallic surface (on which the decelerating gases could compete with the reacting gases to repress activity) was essential for activity; the concept was later shown to be generally important in catalytic processes.

Many of the primary techniques included unconscious applications of catalysis. Fermentation of wine into acetic acid and making soap from fats and alkalis were activities well-known to humans from the dawn of civilization. Sulfuric acid prepared by combustion of a mixture of sulfur and sodium nitrate was an early version of the lead chamber process for the manufacture of sulfuric acid, in which the oxidation of SO2 was accelerated by the nitric oxide produced.

In 1850, the concept of reaction rate was developed during the examination of sucrose hydrolysis, specifically known as inversion. The term inversion is related to the change observed in rotation of the monochromatic light when passed through the reaction system. The parameter could be readily measured, thus facilitating the study of the reaction progress. It was revealed that, at any moment, the inversion rate was proportional to the concentration of sucrose undergoing hydrolysis and the rate was accelerated when acids were present. Afterwards, it was demonstrated that the inversion rate was directly proportional to the acid strength.) This work paved the way for later studies of the reaction rates and the accelerating effect of higher temperatures on them by scientist such as Arrhenius, van’t Hoff, and Ostwald, who played prominent roles in developing physical chemistry as a new discipline. Through his work on reaction rates, Ostwald came to define catalysts as species that changed the rate of a chemical reaction without altering the reaction energy factors.

This account of Ostwald was a breakthrough as it maintained that a catalyst did not change the equilibrium position in a reaction. In 1877, Lemoine proved that the decomposition of hydriodic acid to hydrogen and iodine reached the same equilibrium point at 350°C, 19% regardless of whether the reaction was conducted slowly in the gas phase or rapidly in the presence of platinum sponge. The observation had an important outcome: As noted before, a catalyst for the forward process in a reaction is also a catalyst for the reverse reaction. Berthelot, the eminent French chemist, verified this observation in 1879 with

liquid systems, when he found that the esterification of organic acids and alcohols was catalyzed by small quantities of a strong inorganic acid, just as was the reverse process, i.e., the hydrolysis of the ester.

The purposeful application of catalysts to industrial processes commenced in the 19th century. Phillips, a British chemist, patented the use of platinum utilized in the oxidation of SO2 to SO3 with air. His process was used for a while, but it was discontinued since the platinum catalyst lost activity. In 1871, an industrial process was established for the oxidation of hydrochloric acid to chlorine in the presence of copper(II) salts impregnated in clay blocks. The afforded chlorine was utilized in the manufacture of a bleaching powder (a dry substance that released chlorine upon adding acid) in a reaction with lime. Once more, it was observed that the same equilibrium was reached in both directions. Moreover, it was revealed that the lower the temperature, the greater the equilibrium chlorine content; the maximum amount of chlorine was produced at a temperature of 450°C in a reasonable time.

By the end of the 19th century, the research by the distinguished French chemist, Paul Sabatier, on the interaction of hydrogen with a various organic compounds were conducted using a variety of metal catalysts; his studies led to a German patent for the hydrogenation of unsaturated liquid oils to solid saturated fats with nickel catalysts. Three important German catalytic industrial processes proved to be totally important by the end of the 19th century and in the early decades of the 20th century. The first one was the contact process for the production of H2SO4 from SO2 by smelting. The second was the synthetic manufacture of the valuable dyestuff indigo. The last was the reaction of hydrogen and nitrogen gases to produce ammonia (known as the Haber-Bosch process for nitrogen fixation).

1.4. Nanocatalysis

Catalysis was among the very first applications of nanoparticles. A wide variety of elements and materials such as iron, aluminum, titanium dioxide, silica, and clay had been utilized as catalysts in nanoscale. However, an appropriate explanation of the outstanding catalytic behavior exhibited by nanoparticles has not been provided. The large surface area of nanoparticles has a forthright positive effect on the reaction rate also being a possible explanation for their catalytic activity. Structural properties of any substance at its nano size may also influence its catalytic activity. By fine-tuning of a nanocatalyst in terms of composition, size, and shape, greater selectivity is achievable. Therefore, one may ask what effects the physical properties of a nanoparticle have on its catalytic properties, and how the fabrication parameters may influence those properties. A better grasp of these factors allows a scientist to design highly active, highly selective, and highly resilient nanocatalysts. With all these advantages, industrial chemical reactions will be more efficient, consume much less energy, and generate less waste, thus alleviating the environmental impact arising from our reliance on chemical processes [3–7]. Nanoparticles are indisputably the most

SCHEME 1.2 Effect of intrinsic properties of materials on its catalytic activity [8].

Nanomaterials can be extensively utilized as catalysts with novel features and activity precise adjustment of their size, shape, electronic structure, and surface composition, as well as thermal and chemical stability. Lately, nanostructured catalysts have been considerably studied in both academic and industrial sectors due to their plentiful potential benefits (Scheme 1.3).

1.5. Classification of catalysis

Catalysis is dividable into three major classes: biological, homogeneous, and heterogeneous. Better known as enzymes, biological catalysts naturally occur in living organisms. In a reaction enzyme catalyzed by an enzyme, the reactant is called a substrate, which is converted into the desired product. Most enzymes are proteins and catalyze more than 5000 types of biochemical reactions. A number of important reactions, which are catalyzed by enzymes, are listed in Table 1.1

In homogeneous catalysis, the catalyst exists in the same phase as the reactants are. Many commercially feasible processes have been devised in which homogeneous catalysis is utilized (Table 1.2).

A majority of homogeneous catalysts are expensive compounds of transition metals, and recovery of such catalysts from the workout solution is a challenge. In addition, many homogeneous catalysts can be used only at relatively low temperatures. Even under those conditions, they slowly decompose in solution.

SCHEME 1.3 Beneficial features of nanocatalysis [8]

TABLE 1.1 A few chemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes.

Application Enzyme

Digestive system

Molecular biology

Biological detergent

Proteases, amylase, lipase

Nucleases, DNA ligase, polymerase

Proteases, amylases, lipase

Dairy industry Rennin

Use

Used to digest protein, carbohydrates and fats

Used in restriction digestion and Tire polymerase chain reaction to create recombinant DNA

Remove protein, starch, fat, and oil stains from laundry and dishware

Hydrolyze protein in the manufacture of cheese

TABLE 1.2 A few chemical reactions in which homogeneous catalysts are utilized.

Commercial process Catalyst Application

Hydroformylation Rh/PR3 complexes Production of aldehydes

Adiponitrile process Ni/PR3 complexes Production of nylon Olefin polymerization (RC5H5)2ZrCl2 Production of high-density polyethylene

In heterogeneous catalysis, the catalyst is in a different phase from that of the reactants. Fig. 1.2 shows a simplified energy diagram in which the steps involved in a heterogeneous catalyzed reaction are illustrated. A few reactions which utilize heterogeneous catalysts are listed in Table 1.3 . In heterogeneous catalysis, the catalyst is usually a solid and the reactants are either a liquid or a gas. The reactants interact with the catalyst surface via a physical phenomenon known as adsorption. Upon such interaction, the chemical bonds in reactant A are loosened and break. Then, reactant B adsorbs to the catalyst surface. Reactant B reacts with the atoms of the adsorbed reactant A on the catalyst surface via a stepwise process, after which the product desorbs from the catalyst surface.

A simplified energy diagram illustrating the steps involved in a heterogeneous reaction [15]

TABLE 1.3 A few chemical reactions in which heterogeneous catalysts are utilized. Commercial

Contact process V2O5 or Pt

Haber process Fe, K2O, Al2O3

Ostwald process Pt and Rh

acid

Water-gas shift reaction Fe, Cr2O3, or Cu H2 for ammonia, methanol, and other fuels

Catalytic hydrogenation Ni, Pd, or Pt

Partially hydrogenated oils for margarine

FIG. 1.2

of possible compounds polyoxometalate generally known as polyoxometalates (POMs).These materials can be classified into three broad subcategories [16]:

1. Isopolyanions contain the same metal oxygen framework as heteropolyanions but lacking the central heteroatom. Isopolyanions are mostly less stable in comparison with heteropolyanions and carry a large negative charge [16].

2. Reduced polyoxometalate clusters like molybdenum blue and molybdenum brown are among the very first discovered polyoxometalates; significant research has been dedicated to comprehending and controlling the formation of such materials [16,17]. These polyoxometalates are metal-oxygen anions with wheel-shaped structures.

3. Heteropoly anions are undoubtedly the most widely studied category of polyoxometalates. These species have been utilized in a wide variety of fields [18] such as catalysis [19–23], materials [24–26], and medicine [27]. They are composed of polyanion clusters and cations [28]. These compounds enjoy a structural diversity, in which the oxometal polyhedrons of MOx (x = 5, 6) are the basic construction units. Here, M represents some of early transition metals in their high oxidation state centered by heteroatoms that considerably influence the properties of the species. Typically, the heteroatoms are main group elements, e.g., B, Si, P, S, As, Ga, Ge, Al, and Se. Late transition metals such as Co and Fe have also been observed as heteroatoms. Polyanions are bulky structures with highly negative charges on them. On the surface of the polyanions there are many oxygen atoms capable of donating one or more electrons to an electron acceptor. Polyanions can therefore be considered as soft bases. It is evident that the metal ions on the polyanions’ skeleton have unoccupied orbitals that can accept electrons. In other words, polyanions can also serve as Lewis acids. Thus, polyanions can play the roles of a Lewis acid and Lewis base depending on different conditions. Furthermore, owing to their strong capacity to bear electrons and release electrons, polyanions are usually regarded as electron reservoirs; that is to say that these species possess redox properties as well [29]. Above all, these polyanions are designable. In order to achieve specific properties, their structures and components can be adjusted. Substitution of polyhedra, variation of the heteroatom, and pattern rearrangement of the basic construction units are among the most common methods to realize this. The most known structure of heteropoly acids is the Keggin structure. Keggin-type heteropoly acids have been investigated most of all in catalysis because of their unique stability. A Keggin heteropoly acid follows the general formula of [XM12O40]n , in which X is the heteroatom (typically P5 +, Si4 +, or B3 +), M is the addenda atom (usually molybdenum or tungsten), and O is oxygen.

The advantages of heteropoly anions as catalyst were summarized by Okuhara et al., and are listed in Table 1.4.

Heteropolyacids as highly efficient and green catalysts

TABLE 1.4 Advantages of heteropolyanion catalysts.

1. Catalyst design at atomic/molecular levels based on the following

• Acidic and redox properties

These two important properties for catalysis can be controlled by choosing appropriate constituent elements, i.e.:

• Type of poly anion

• Addenda atom

• Heteroatom

• Counteranion, etc.

• Multifunctionality

Acid-redox, acid base, multielectron transfer, photosensitivity, etc.

• Tertiary structure. Bulk-type behavior

2. Molecularity-metal oxide cluster

• Molecular design of catalysis

• Cluster models of mixed oxide catalyst and of relationships between solid and solution catalysts

• Description of catalytic processes at atomic molecular levels

• Spectroscopic studies and stoichiometry are realistic

• Model compounds of reaction intermediates

3. Unique reaction field

• Bulk-type catalysis

“Pseudoliquid” and bulk-type II behavior provide unique three-dimensional reaction environment for catalysis

• Pseudoliquids behavior

Spectroscopic and stoichiometric studies are feasible and realistic

• Phase-transfer catalysis

• Shape selectivity

4. Unique basicity of polyanion

• Selective coordination and stabilization of reaction intermediates in solution and in pseudoliquid phase

The properties and applications of heteropoly acids will be discussed in the following sections.

1.7. Heteropoly acids as green catalysts

Over time, a number of different principles have been suggested that may be used when considering the design, development, and implementation of chemical processes. With these principles, scientists and engineers will be able enhance

and protect the economy, people, and the planet through devising new innovations and creative ways to save energy, diminish waste, and discover replacements for hazardous substances. Paul Anastas and John Warner [30] formulated 12 principles of green chemistry in 1998, which are outlined as follows:

1. Prevention. It is better to prevent the waste from being generation than to treat or clean it up after it has been generated.

2. Atom Economy. Synthetic procedures must be designed in which the incorporation of all the materials utilized in the process is maximized.

3. Less Hazardous Chemical Synthesis. Whenever possible, synthetic procedures must be designed to utilize and produce substances with little or no toxicity.

4. Safer Chemical Design. Chemical products must be designed in a way that the desired function is fulfilled while their toxicity is minimized.

5. Safer Auxiliaries. Using auxiliary substances, i.e., solvents, separation agents, etc. must be excluded whenever possible and/or the most innocuous ones are used.

6. Designing for Energy Efficiency. The energy needed for a chemical process must be considered for its environmental and economic impacts and minimized. Synthetic methods should be conducted at ambient temperature and pressure whenever possible.

7. Use of Renewable Feedstock. Whenever technically and economically possible, renewable rather than depleting raw materials must be used.

8. Reduce Derivatives. Unnecessary use of protection/deprotection, blocking groups, or temporary modification of physical/chemical processes must be minimized or avoided whenever possible, as these steps require more reagents and energy and result in more waste.

9. Catalysis. Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are preferred over stoichiometric reagents.

10. Design and Degradation. Chemical products must be designed in a way that eventually they break down into harmless degradation products that do not last for a long time in the environment.

11. Real-Time Analysis for Pollution Prevention. Analytical methodologies have to be developed more than before to enable real-time, in-process monitoring so that it is possible to control hazardous substances before they are formed.

12. Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention. Substances and its various forms used in a chemical process must be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents including explosions, releases, and fires.

Ryoji Noyori, a Chemistry Nobel Prize winner, pointed out to three important developments in green chemistry [31]. The first was to solve the solvent problem using supercritical carbon dioxide; the second was green oxidation with aqueous hydrogen peroxide; and the third one was the application of hydrogen in asymmetric syntheses.

These solid acids are used in bulk or supported forms. They can serve as homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts [36]. Several aspects of heteropoly acid as green/sustainable catalysts are described.

1.7.1 Water-tolerant solid acid catalysts

Acidic cesium salts of strongly acidic heteropoly acid are appropriate examples of useful active solid acid catalysts demonstrating a very good performance in many organic reactions because of their high surface acidity, and presumably due to their unique basic properties [37]. However, most of the times, the catalytic activities of solid acids are significantly suppressed in the presence of water; on the other hand, H-ZSM-5 with a high ratio Si:Al has been observed to have fair tolerance in aqueous solution [38]. Recently, it has been shown that the acidic cesium salts of heteropoly acids are catalysts high tolerance for water in hydration of olefins [39] and hydrolysis of esters [40]. This was attributed to the mild hydrophobicity of the catalysts [41]. Some examples of catalytic performances are provided in Table 1.6 [40].

1.7.2 Pseudoliquid phase

Having a flexible solid structure, in some heteropoly acids, reactants with polar molecules or basic properties are easily absorbed into the solid lattice (in the cavities between the polyanions of the lattice) sometimes expanding the lattice) and reacting therein. That is to say, the reaction field becomes a threedimensional one as if it is in a solution but much more orderly.

Because of such a behavior, heteropoly acid catalysts usually demonstrate high catalytic activities as well as unique selectivities. A few examples are listed in Table 1.7 [42]. In this particular case, a heteropoly acid catalyst can be termed as a catalytically active solid solvent.

TABLE 1.6 Water-tolerant catalytic activities of solid acids for the hydrolysis of cyclohexyl acetate.

TABLE 1.7 A comparison of catalytic activities of heteropoly acids with silica-alumina. Reaction

Dehydration of 2-propanol PW12a

Isobutene + CH3OH → MTBE

PW12/SiO2 90

Dehydration of ethanol PW12

Acetic acid + ethanol → ethyl acetate

a PW12: H3PW12O40.

PW12/carbon

1.8. Solid-solid phase c atalysis

Very small particles of the acidic cesium salts of 12-tungstophosphoric acid effectively catalyze many organic reactions in the solid state, among which is solid p-toluenesulfonic acid [43]. In such cases, catalysts and reactants are both solids. The greenness of these reaction systems is probably dependent upon the workup process of the products after the reaction.

1.8.1 Combination of a heteropoly acid and noble metals (bi-functional catalysis)

Heteropoly acid catalysts promoted by platinum or palladium exhibit high catalytic activity and selectivity for the skeletal isomerization of n-alkanes (C4–C7) at low pressures of hydrogen and low temperatures. This is most likely because of the uniform and mildly strong acid strengths of heteropoly acid catalysts. An attractive example of heteropoly acid catalysts in combination with noble metals is Pd-H4SiW12O40 promoted by Se or Te for the one-step oxidation of ethylene to acetic acid in the gas phase at about 150°C [44]. It was postulated that the reaction proceeded in two steps: first, hydration of ethylene to ethanol catalyzed by heteropoly acid (acid catalysis); and second, oxidation of ethanol to acetic acid on the palladium site. Presently, a plant annually producing 100,000 MT is operating in Japan (since 1997, by Showa Denko). The new process produced a much smaller amount of wastewater and by-products, and the system was not corrosive.

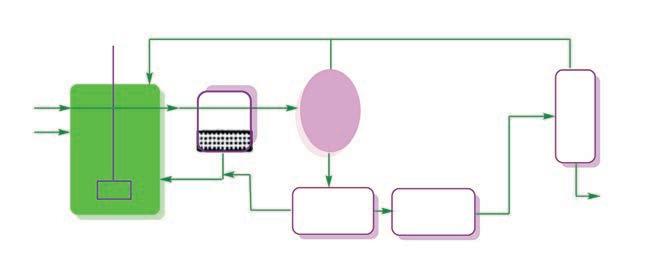

1.9. Green processes using heteropoly acid catalysts in two phases

Using heteropoly acid catalysts in solution, Asahi Chemical commercialized the selective hydration of isobutylene in a mixture of n-butenes and isobutylene

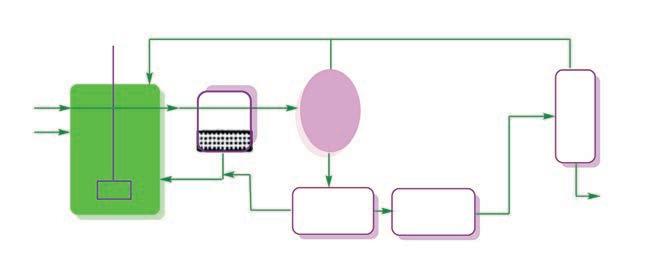

as well as the polymerization of tetrahydrofuran in the 1980s. Both of these reactions were conducted in two phases. Since the separation of product from the catalyst is very easy and the process is quite simple, energy and cost are tremendously reduced. The polymerization of THF is shown in Fig. 1.3 [46].

Polymerization to polyoxymethyleneglycohol (PTMG) proceeds in the H2OTHF-HPA phase. Polyoxymethyleneglycohol is recovered from its own phase and the phase containing the heteropoly acid and oligomer is just recycled to the reactor. It has been claimed that there is literally no waste. The molecular weight of the product polymer is controlled by its appropriate solubility in the THF-PTMG phase making the distribution narrow.

1.10. Types of catalytic activity of heteropoly acids

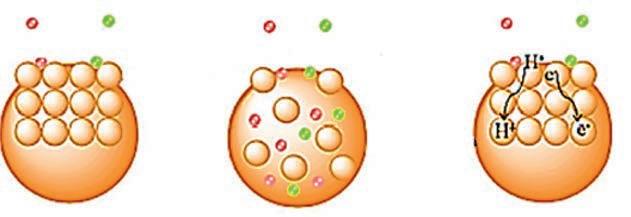

As illustrated in Figs. 1.4 and 1.5, Misono and coworkers [49] have defined the catalytic activity of heteropoly acids in two different types of reaction: reactants (R) and products (P) interact either at the surface (Fig. 1.4A) or in the depth of the three-dimensional bulk (Fig. 1.4B). The first type shows the common process in a heterogeneous system, in which the reaction is catalyzed on the external surface of the solid; the reactant is a nonpolar molecule only interacting with the external acid protons. Reaction rates are determined by the catalyst surface area and the number of protons accessible to the nonpolar substrate. In the second catalytic mechanism, catalysis takes place within a tertiary structure, in which the reactant diffuses, leading to an expanded interpolyanion distance occurring when the reactants are polar. After the formation, the products diffuse back to the external surface and then into the reactant phase (gas or liquid). This bulk-type catalytic mechanism may in turn be divided into two subcategories: pseudoliquid catalysis and redox catalysis. In pseudoliquid catalysis with the protons from the bulk are the active species. The title pseudoliquid comes from the fact that polar molecules like water, alcohols, or

FIG. 1.3 Flow diagram for the polymerization of tetrahydrofuran to poly-oxytetramethyleneglycol (Asahi Chemical) [45]

small amines are able to diffuse into the bulk structure of the heteropoly acid to give a concentrated reaction solution in which conversion occurs [50]. Redox processes take place in reactions in which protons and electrons are rapidly diffused into the bulk.

1.11. Cat alytic properties

The fascinating properties of heteropoly acids, such as tunable acidity and redox properties, high thermal stability, inherent resistance to oxidative decomposition, and striking sensitivity to light and electricity, have made them excellent candidates for catalytic purposes. There is a tight relationship between these remarkable properties and their structures and compositions. Their distinct atomic connectivity provides the compositional diversity necessary for a close assessment of the outcomes that result from composition change on catalytic reactivity.

With such tempting promises in industry, these powerful catalysts have been investigated for a long time. Presently, dozens of processes have been industrialized with heteropoly acids as the catalysts, among which are the hydration of propene [51], isobutene [52], and 2-butene [53] to their corresponding alcohols, oxidation of isobutyraldehyde with O2 to isobutyric acid [52], polymerization of tetrahydrofuran [46,54], amination of ketones to imines [55], oxidation of ethylene with O2 to acetic acid [44], and esterification of acetic acid with ethylene to ethyl acetate [56]

1.11.1 Active sites

Owing to their multiple active sites, which include protons, oxygen atoms, and metals, heteropoly acids are regarded as versatile catalysts. Protons are seemingly able to serve as Brønsted acids and promote acid-catalyzed reactions. Some oxygen atoms on the surface of these anions, especially those on the lacunary sites of lacunary anions with high negative charges, are basic enough to react with protons, to the extent of abstracting active protons from the organic substrates. In other words, the oxygen atoms on the surface of heteropoly acids can serve as active sites in base-catalyzed reactions. However, attention should be focused on the metal cores of a heteropoly acid catalyst since they are the active sites in all oxidative reactions, part of acid-catalyzed reactions, and a majority of other reactions. Thus far, plenty of heteropoly acid catalysts have been utilized in oxidative reactions, almost all of which are tungsten- or molybdenum-based compounds. Additionally, some heteropoly acids work as catalyst precursors so that during the reaction, they may decompose to small active species. This is shown in a work by Ishii [19].

1.11.2 Stability

Stability is a critical concern for catalysts, which is in part due to the fact that it directly influences the activity and recyclability of the catalyst.

The stability in the case of heteropoly acid catalysts usually means thermal stability, oxidative stability, and hydrolytic stability. Depending upon the type of heteropoly acid catalyst, these stabilities change significantly. In general, heteropoly acid catalysts enjoy attractive thermal stabilities. The thermal stability in some of Keggin-type heteropoly acids is so high that they can be applied as catalysts in gas-phase reactions at high temperatures. The high thermal stabilities of heteropoly acids are relative. For instance, H 3PW 12 O 40 loses its protons at 450–470°C to form a new species of the formula {PW 12O 38.5}, and the structure is completely devastated at about 600°C [57] . Therefore, suitable reaction temperatures are essential for the systems using the Brønsted acid sites of a heteropoly acid catalyst, particularly for the gas-phase systems operated at high temperatures, since high temperatures will cause the molecule to lose its active protons. Moreover, the thermal stabilities are important for the regeneration process of the catalyst. High temperatures often result in coking on the catalyst during the reaction, which in turn deactivates the catalyst. Therefore, the catalyst regeneration involves decoking, which is typically done at high temperatures. The suitable decoking temperature must be less than the temperature at which the catalyst loses its active protons.

In addition to the heteroatoms, substituting metals and the countercations may considerably influence the thermal stability of a heteropoly acid. Substituted heteropoly anions are generally more labile than their unsubstituted counterparts. For instance, vanadium atoms are released from the H 3 + n V n PMo 12 n O 40 skeleton at elevated temperatures to form monomeric vanadium species along with PMo 12O 40 [58,59] . The detaching of substituting metals occurs for [FePMo 11O 39] 4 as well [60] . However, the detachment temperature is strongly related to its countercation. If the ammonium ion is used as the countercation, the release of iron from the Keggin anion occurs at 197°C due to the reaction of Fe 3 + with NH 4 +. On the other hand, if cesium cation is used, iron is released at 297°C. Typically, heteropoly acids have a significant hydrolytic and oxidative stability owing to the absence of organic ligands. Even though it is possible that the polyhedral subunits of the anions are detached from the main skeleton in the presence of water, their stability in over a certain pH range is secured. A wide variety of reactions with heteropoly acid catalysts can be performed even in pure water [61–69] . In addition, heteropoly anions are intensely persistent against oxidizing agents. Therefore, this type of catalyst may be utilized in water- and oxygen-rich systems without the protection by inert gases, which is usually necessary for many organometallic catalysts. The strongest evidence is the oxidation of organic substrates by dilute hydrogen peroxide [70] and booming water oxidation with heteropoly acid catalysts [69]

In brief, all three kinds of catalyst stability—thermal, hydrolytic, and oxidative stability—are important, their relative importance being dependent on the type of catalysis and transformation.

1.12. Photocatalysis

It is possible to excite the heteropoly anions from their ground states can be by ultraviolet or near-visible radiation. The excitation is essentially a charge transfer from an oxygen atom to the d0 transition metal in the presence of radiation with enough energy. For instance, the excitation of [PW12O40]3 corresponds to a charge transfer from O2 to W6 +, which results in the formation of a pair consisting of a trapped electron center (W5 +) and hole center (O ) [71]. Heteropoly anions in their excited states usually exhibit a better performance than in their ground states as both electron donors and electron acceptors [72]. Therefore, some of heteropoly acids, which are catalytically inactive even at high temperatures, but under dark conditions, may turn into robust reagents with the ability of oxidizing or reducing various substrates upon the irradiation of ultraviolet or near-visible light. In addition, the HOMO-LUMO bandgaps in heteropoly anions prevent the recombination of electrons and holes resulting from the irradiation of a light with an energy greater than or equal to their bandgap energy [71]. The photogenerated electrons and holes can therefore initiate the chemical reaction owing to the strong photoreductive ability of the electrons and photooxidative ability of the holes. Under moderate conditions, many photocatalytic reactions take place readily in the presence of heteropoly acids, among which are: the oxidation of alcohols [73–75], benzene [76], and phenol [77]; oxidative bromination of arenes and alkenes [78]; reduction of CO2, [79,80], etc. More significantly, the photooxidation properties are eminently suitable for the degradation of a variety of aqueous organic pollutants [81–91] and their photoreduction properties can be utilized to remove transition metal ions from water [92].

Streb et al. [93] have reviewed new trends in the polyoxometalate photoredox chemistry of polyoxometalates. According to the review, in addition to the facile photoexcitation using ultraviolet or near-visible radiation, homogeneous heteropoly acid photocatalysts exhibit a number of advantages, e.g., intense absorption of radiation with high molecular absorption coefficients, high structural stability, high redox activity, multielectron redox capability, and easy reoxidation of reduced species. However, as an important problem, absorption of the radiation by heteropoly anions only takes places in the region of 200–500 nm. Therefore, photosensitization can be utilized as a strategy to allow for using visible light. Some photosensitizers, like fullerene, can be attached to heteropoly anions by forming covalent bonds; also, some cationic photosensitizers may be associated with heteropoly anions via electrostatic interactions.

For practical purposes, more emphasis has been put on heterogeneous photocatalysts in the field of photocatalysis by heteropoly acids. The original parent heteropoly acids are ordinarily supported on other substances to give composite heterogeneous photocatalysts. The most commonly used supports are TiO2 [94–98], SiO2 [99–103], ZrO2 [104,105], etc. Moreover, the solidification of heteropoly acids—i.e., their combination with supports—provides them with much larger specific surface areas, which in turn may lead to an increase in their

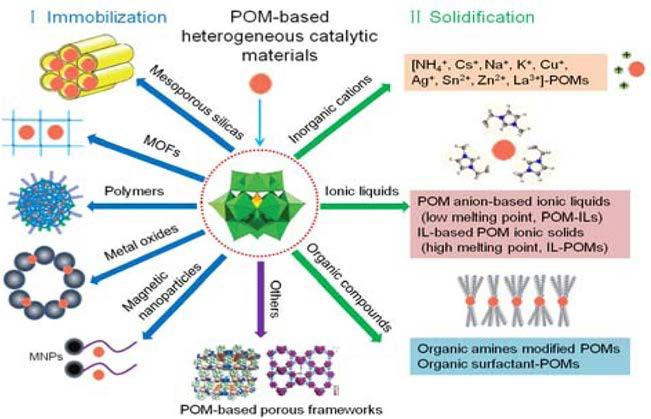

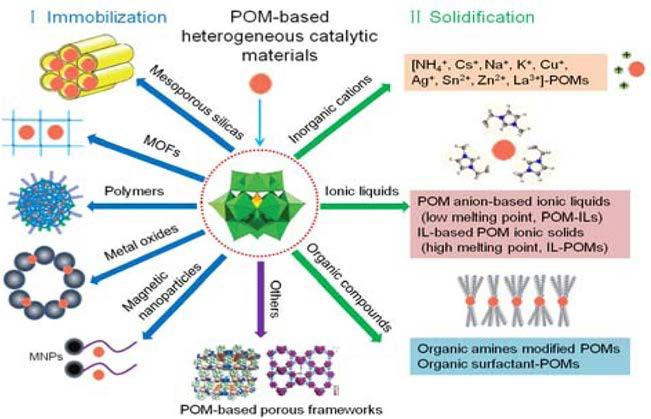

which is largely attributed to the diffusion limitation of the active sites and the mass transfer resistance. In order to resolve the mentioned restrictions, many tactics have been suggested to enhance the stability and catalytic performance. Commonly, preparation of HPA-based heterogeneous catalysts is achievable mainly by two strategies, i.e., solidification and immobilization of the catalytically active heteropoly acids [111]. As presented in Scheme 1.4, the former involves preparing an insoluble salt of the heteropoly acid, while the latter involves supporting the active heteropoly acid on various porous substances. The preparation and application of HPA-based heterogeneous catalysts have been covered in many reviews, but very little attention has been paid to their homogeneous behavior.

It is also noteworthy that in heterogeneous catalysis with a heteropoly acid, in order to achieve high activity as well as sound recovery and recyclability, emphasis is placed on the solidification of heteropoly acid catalysts. A number of methods have been utilized in solidification of soluble active heteropoly acids among which are the introduction of large inorganic cations and dendritic organic cations, encapsulation by metal organic frameworks (MOFs), and blending with supporting materials, such as metal oxides, various C/Si-based substances, polymers, etc. There is another important difference between the heterogeneous and homogeneous systems in heteropoly acid catalysts, and that is their reaction fields. Homogeneous reactions take place in the solution since the heteropoly acid catalyst is evenly distributed in the solution. On the other hand, the case for a heterogeneous catalysis is extremely complicated. As illustrated in Fig. 1.6,

SCHEME 1.4 Major strategies for the preparation of heterogeneous heteropoly acid catalysts [112].

FIG. 1.6 Three catalysis models for solid POM catalysts: (A) surface type; (B) pseudoliquid bulk type; and (C) bulk type [49]

three different modes of catalysis exist for heteropoly acids as heterogeneous catalysts: the surface-type catalysis, bulk-type I (pseudoliquid phase) catalysis, and bulk-type II catalysis in the presence of electrons or protons [113].

1.14.1 Surface-type catalysis

The surface-type catalysis is the regular heterogeneous catalysis, in which the reactions occur on a 2D surface (outer surface and pore walls) of the solid catalyst. The rate of the reaction is principally proportional to the surface area. Reaction rates of olefins double-bond isomerization processes are proportional to the surface area of H3PMo12O40 [114]. Most of the reactions catalyzed over the acid Csx H3 xPW12O40 (2 < x < 3) display the same correlation between the rate and surface acidity [115,116].

1.14.2 Bulk-type I catalysis

In the bulk-type I (pseudoliquid phase) catalysis, for example, reactions of polar molecules over the hydrogen and catalyzed by acid salts are formed at rather low temperatures, the reactant molecules are absorbed into the space between the heteropoly anions of the ionic lattice, and the reaction occurs inside that space. Next, the products desorb from the solid [117–119]. In this process, the solid behaves as if it is a solution and a three-dimensional reaction field is in operation. This is why it is also called the pseudoliquid phase. The reaction rate is proportional to the catalyst volume in the ideal case. From a different point of view, the rate of the acid-catalyzed reaction is governed by the bulk acidity. This sort of catalysis has been observed for both gas-solid and liquid-solid systems [120].

Using the transient response method with nondeuterated and deuterated alcohols, it was confirmed that under the reaction conditions of dehydration, a large number of alcohol molecules are absorbed into the catalyst bulk and the adsorption/desorption rate is faster than the dehydration rate [121].

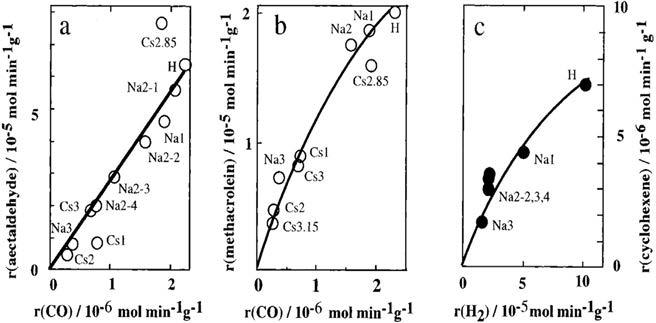

1.14.3 Bulk-type II catalysis

Some oxidation reactions, such as oxidation of hydrogen and oxidative dehydrogenation at high temperatures, demonstrate bulk-type II catalysis [122]. In this sort of catalytic oxidation, the main reaction may proceed on the surface, but the whole solid bulk participates in the redox catalysis process due to rapid migration of redox carriers, i.e., protons and electrons. In such cases, the reaction rate is ideally proportional to the catalyst volume. The correlations between the catalytic activity for oxidation and the oxidizing ability of the catalysts are illustrated in Fig. 1.7A–C [123–126]. A monotonous correlation can be seen between the rates of catalytic oxidation of acetaldehyde and methacrolein (surface-type reaction) and the reduction rate of catalysts by CO (surface oxidizing ability) [124,125]. A similar correlation is evident for the oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexene (bulk-type II) and reduction rate of the catalysts by hydrogen (bulk oxidizing ability, Fig. 1.7C) [126]. For the catalytic oxidation of hydrogen (bulk-type II) and CO (surface-type) over alkali salts of H3PMo12O40, a redox (Mars-van Krevelen) mechanism has been proposed. It is observed that the rates of catalytic oxidation, the rates of reduction, and reoxidation of catalysts coincide with each other at the stationary oxidation state of the catalyst [127].

Such correlations have not been observed for H3 + x[PMo12 xVxO40] due to the thermal instability.

FIG. 1.7 Correlations observed among the catalytic activity and oxidizing ability for the oxidation reactions of (A) acetaldehyde, (B) methacrolein (surface reactions), and (C) oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexene (bulk-type II reactions). r(acetaldehyde), r(methacrolein), and r(cyclohexene) are the rates of catalytic oxidations of acetaldehyde, methacrolein, and oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexene. r(CO) is the rate of reduction of the catalysts by CO; r(H2), reduction rate of catalysts by hydrogen. Mx denotes MxH3 xPMo12O40. Na2-1, -2, -3, and -4 are Na2HPMo12O40 of different lots, for which surface areas are 2.8, 2.2, 1.7, and 1.2 m 2 g 1, respectively [20].

The technique used for developing chemisorbed carbon-POM nanocomposites is commonly straightforward. First, the carbon substrate is oxidized with a strong acid to add surface functional groups, which act as binding sites and modify the polyoxometalate. Then the carbon material is dispersed in an organic or aqueous solution of the polyoxometalate and agitated by stirring or ultrasonication under ambient conditions. The solid product is finally washed with water many times to remove the excess loose species, dried, and the surface modified carbon-POM composite is produced [129–132]. This technique is extendable to a various carbon substrates, e.g., carbon nanofibers (CNFs) and multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [129,132–138], mesoporous carbon [139], activated carbon [140], and graphene [141–144]. The chemisorption technique provides a simple, efficient means for the preparation of a wide range of nanostructured carbon-POM composites.

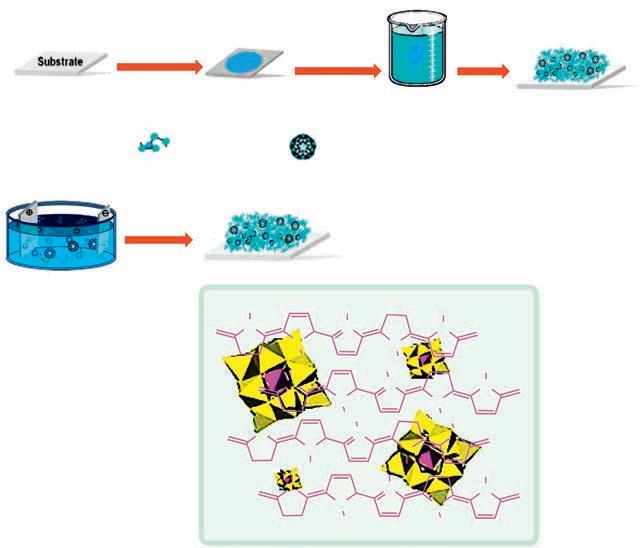

1.15.1.2 Immobilization in a polymer matrix

The reversible redox chemistry and conductivity exhibited by conductive organic polymers (COPs) in combination with their relatively low cost and good handling capacity have rendered these materials excellent substrates for polyoxometalate integration with polyoxometalate. Various conductive organic polymers can be utilized to afford hybrid materials with polyoxometalates among which polypyrrole (PPy) [145–148], polyaniline (PANI) [149,150], polythiophene (PT) [151], and their derivatives are the most common. As illustrated in Fig. 1.8, the procedures for immobilizing polyoxometalates within a COP matrix are categorized into two broad groups. In the first type, after following a two-step approach, a polymer thin layer is deposited on a substrate through electro-polymerization or spin coating. Then the polymer film is dipped in a polyoxometalate solution so that the polyoxometalate is diffused and incorporated into the polymer matrix [145]. In the second type, which is a onestep method, a monomer molecule is chemically or electrochemically oxidized to form a polymer thin layer in the presence of a polyoxometalate solution. High ionic conductivity, strong oxidizing power, and acidic character of heteropoly acids deliver the best conditions for the polymerization of such monomers as thiophene, aniline, and pyrrole. In the electrochemical polymerization of a monomer, the polyoxometalate solution is frequently utilized as the electrolyte. A thin layer of polymer is deposited on the working electrode by applying a sufficient oxidation potential, which is doped with the polyoxometalate molecule. Polymerization techniques give rise to a nanostructured hybrid species in which the bulky polyoxometalate molecule is confined within a COP matrix [149,150]. The abovementioned approaches can be adapted to prepare a wide range of new POM-COP hybrids.

In comparison with chemisorption, immobilization within a COP matrix enjoys the advantage that it results in combined electrochemical activity. In addition to providing structural support, the substrate contributes reversible Faradaic reactions to improve the overall electrochemical performance of the

FIG. 1.8 Preparation of a POM-COP matrix through (A) a two-step and (B) a one-step method. (C) The structure of hybrid PPy-PMo12O403 [152]

hybrid. Chemisorbed carbon-POM composites can be prepared by simple mixing, while more complex and potentially costly synthesis techniques are necessary for carbon-COP hybrids, particularly in the case of electropolymerization. Additionally, since inclusion within a COP matrix is not a technique for surface modification, the polyoxometalate is frequently embedded within the bulk of the polymer. Hence, additional preparation steps (such as the use of an external oxidant) are required to fabricate a true nanocomposite.

1.15.1.3 Layer-by-layer self-assembly

Developed by Decher in the 1990s [153], layer-by-layer (LbL) deposition is the alternate adsorption of positive and negative layers on a support surface using electrostatic forces. Aqueous solutions of two molecules with opposite charges are consecutively coated on the support surface. The surface charge is reversed after each dipping cycle to allow the deposition of the succeeding layer. With this method, multilayer structures are formed, which are predominantly stabilized by strong electrostatic forces; other interactions, e.g., hydrogen bonding may be present as well [154]. Layer-by-layer self-assembly is an excellent method for the preparation of carbon-POM films; since the groundbreaking