Driving Wellness: Mitigating Burnout,

Redefining Wellness

Sparking a flame inside or burning out. In this issue, we look at what it means to redefine – and design – our own wellness.

Cover image by Isabel Souza, Associate AIA, NOMA.

2025 Young Architects Forum Advisory Committee

2025 Chair

2025 Vice Chair

2025 Past Chair

2025-2026 Advocacy Director

2025-2026 Communications Director

2024-2025 Community Director

2025-2026 Knowledge Director

2024-2025 Strategic Vision Director

2025 AIA Strategic Council Representative

2025 College of Fellows Representative

2025 Council of Architectural Component Executives Liaison

Sarah Woynicz, AIA

Kiara Gilmore, AIA

Jason Takeuchi, AIA

Tanya Kataria, AIA

Nicole Becker, AIA

Seth Duke, AIA

Arlenne Gil, AIA

Carrie Parker, AIA

Patty Boyle, AIA

Bill Hercules, FAIA

Jillian Tipton, AIA AIA Staff Liaison

Kathleen McCormick

2025 Young Architect Representatives

Alabama, Ashley Askew, AIA Alaska, Zane Jones, AIA Arizona, Andrea Hardy, AIA Arkansas, Lauren Miller, AIA California, Magdalini Vraila, AIA Colorado, Kaylyn Kirby, AIA

Connecticut, Andrew Gorzkowski, AIA

Delaware, Jack Whalen, AIA

Florida, Bryce Bounds, AIA

Georgia, Laura Sherman, AIA

Hawaii, Krithika Penedo, AIA

Idaho, Katie Bennett, AIA Illinois, Raquel Guzman Geara, AIA Indiana, Matt Jennings, AIA Iowa, Ben Hansen, AIA Kansas, Garric Baker, AIA Kentucky, George Donkor, AIA Louisiana, Calvin Gallion, III, AIA Maine, Sarah Kayser, AIA Maryland, Joe Taylor, AIA Massachusetts, Darguin Fortuna, AIA Michigan, Trent Schmitz, AIA Minnesota, Constance Chen, AIA Mississippi, Robert Farr, AIA Missouri, Chelsea Davison, AIA

Montana, Elizabeth Zachman, AIA Nebraska, Angel Coleman, AIA

Nevada, Daniela Moral, AIA

New Hampshire, Courtney Carrier, AIA

New Jersey, Abby Benjamin, AIA

New Mexico, Diana Duran, AIA

New York, Mi Zhang, AIA

North Carolina, Colin McCarville, AIA

North Dakota, Brady Laurin, AIA

Ohio, Alex Oetzel, AIA

Oklahoma, Brian Letzig, AIA

Oregon, Elizabeth Lagarde, AIA

Pennsylvania, Mel Ngami, AIA

Rhode Island, Taylor Hughes, AIA

South Carolina, Ryan Lewis, AIA

South Dakota, Liz Brown, AIA

Tennessee, Sara Page, AIA

Texas, Kyle Kenerley, AIA

Utah, Zahra Hassanipour, AIA

Vermont, Devin Bushey, AIA

Virginia, Erin Agdinaoay, AIA

Washington, Rio Namiki, AIA

West Virginia, Joey Kutz, AIA

Wisconsin, Justin Marquis, AIA

Wyoming, Kendra Shirley, AIA

Washington, D.C., Kumi Wickramanayaka, AIA

Puerto Rico, Reily J. Calderón Rivera, AIA

AIA International, Jason Holland, AIA

Connection is the official quarterly publication of the Young Architects Forum of AIA.

This publication is created through the volunteer efforts of dedicated Young Architect Forum members and made possible through generous grant funding from the College of Fellows.

Copyright 2025 by The American Insititute of Architects. All rights reserved

Views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and not those of The American Institute of Architects. Copyright © of individual articles belongs to the author. All images permissions are obtained by or copyright of the author.

05 Rewriting the Rules: Editor’s Note

Nicole Becker, AIA

06 Chair’s Message

Sara Woynicz, AIA

07 Breathe In: Burn Out

Arti Verma, AIA

08 The Art of Suffering

Nicole Becker, AIA

12 The Unapologetic Productivity System

Abigail Benjamin, AIA

14 Redefining Productivity Through Wellness

Isabel Souza, Assoc. AIA

16 From Moments to Movements

Gabriella Bermea, AIA

19 Colleague to Colleague (C2C) Mentorship Program

Vince Avallone, AIA

20 How Do We Grow New Architects

Shannon Christensen, FAIA

23 Designing Balance Between Work, Service, and Self

Saakshi Terway, Assoc. AIA

26 Motherhood as a Catalyst for Redefining Care and Wellness in Architecture

Danielle McCormick, Assoc. AIA

29 The Future of Human Mobility

Manuel Granja, AIA

31 Women’s Leadership Summit 2025 Arti Verma, AIA

34 Beyond the Stamp Devora Schwartz, AIA

36 Taking Care of Business Aerianne Gil, AIA

39 Critical Aspects

Rocky Hanish, AIA

41 The Hidden Infrastructure of Practice

Alya Staber, WELL AP, Silvia Colpani, Assoc. AIA

43 Breaking the Silence Contributed by our readers

45 The ArchiTEXT Book Club: Eating Salad Drunk Review by Justin Marquis

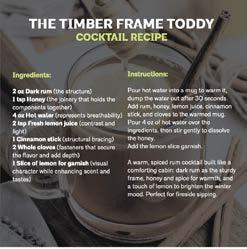

46 Connect & Chill AIA YAF Knowledge Focus Group

Editorial team

Nicole Becker, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C Editor in chief

Nicole is an Associate and Project Architect at ZGF Architects in Portland, Oregon specializing in Healthcare. She is the 2025 Communications Director of the AIA Young Architects Forum.

Bryce W. Bounds, AIA, NCARB, CGC Senior editor

Bryce is a Miami native, a Construction Project Management Supervisor in the Public Works department of Broward County, and Florida’s YAR. He attended Design and Architecture Senior High School (DASH) in Miami-Dade and graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with bachelors in both Architecture and Fine Art.

Constance Chen, AIA, NCARB Senior editor

Constance is a Minnesota native and a principal at Locus Architecture in Minneapolis. A University of Notre Dame graduate, her design approach intends to make meaningful connections between people and spaces. She serves as Minnesota’s YAR.

Andrew Gorzkowski, AIA, NCARB Senior editor

Andrew is a Senior Associate at Pickard Chilton in New Haven, Connecticut, where he works in design and project management roles on a variety of large-scale commercial projects. Passionate about advocating for a sustainable future for the profession, he serves as the Connecticut YAR and co-chair’s his local AIA Committee on the Environment. He received his degree at Cornell University, where he was a Meinig Family Cornell National Scholar.

Andrea E. Hardy, AIA, EDAC, NOMA, NCARB Senior editor

Andrea is a Senior Architect at Shepley Bulfinch, where she supports healthcare projects out of their Phoenix Office as a Project Manager. She is Arizona’s YAR, and is passionate about community involvement whether through work, AIA, or locally in the City of Phoenix. She has degrees from Wentworth Institute of Technology and ASU.

Kyle Kenerley, AIA Senior editor

Kyle is an Associate at Modus Architecture based in Dallas, Texas where he works on healthcare and workplace projects as the project manager and technical design lead. He is currently the YAR for Texas where he also serves on the board for the Texas Society of Architects. Kyle’s service with his local and state AIA chapter has primarily been focused on mentoring young architects and education outreach.

Justin Marquis, AIA, NCARB Senior editor

Justin is a Project Architect with Somerville Architects & Engineers in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Managing projects through all phases of development from conceptual design to construction administration, he currently supports the healthcare and educational studios at Somerville. He has a degree from the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee and lives in the Fox Valley area with his family. Justin is the Wisconsin Young Architect Representative..

Garric Baker, AIA, NCARB Senior graphic designer

Baker is a graduate of the College of Architecture, Planning & Design at Kansas State University and excels in leadership positions with state and regional Chambers of Commerce, Young Professionals, the Kansas Barn Alliance, local and state Wide AIA Kansas Board of Directors, and Regional Economic Development activites.

Katie Bennett, AIA, NCARB Senior graphic designer

Katie is a project manager at Babcock Design in Salt Lake City, Utah and Boise, Idaho, and oversees projects during their inception phase through schematic design. She is the current YAR for the state of Idaho and is passionate about housing and sustainable design.

Calvin Gallion, III, AIA, NOMA, NCARB, LEED GA Senior graphic designer

Calvin is an architect and principal at studio^RISE in New Orleans. A Tulane graduate and Natchitoches native, he is a passionate advocate for community and rehabilitation projects. He serves as EDI Chair for AIA New Orleans and as Louisiana’s YAR.

Kendra Shirley, AIA, NCARB Senior graphic designer

Kendra is a project architect at Arete Design Group in Wyoming and Colorado and is Wyoming’s YAR. As a graduate from one of the top undergraduate architecture programs in the country, Kendra’s training and experience provides her with a unique and innovative perspective for creating extraordinary experiences and designs.

Rewriting the Rules

Editor’s Note

This issue is one that feels deeply personal. Like many in our profession, I’ve faced burnout, the kind that quietly builds until the work you once loved feels heavy. Working long hours was worn as a badge of honor, a symbol of passion and commitment. But somewhere along the way, exhaustion became mistaken for excellence. I’ve learned that wellness isn’t about perfection or balance that never falters, it’s about learning to pause, creating room to breathe, aligning our goals with our values, and then returning to our work recharged and grounded in purpose.

In this final issue of the year, we explore wellness not as a trend, but as a practice. We dig into what burnout really means beyond being a buzzword. We ask: what does it mean to truly sustain ourselves and our profession? Through reflections on Designing Balance Between Work-Service-and Self, Motherhood as a Catalyst for Redefining Care and Wellness in Architecture, and Redefining Productivity Through Wellness, this issue invites us to look beyond productivity and toward wholeness.

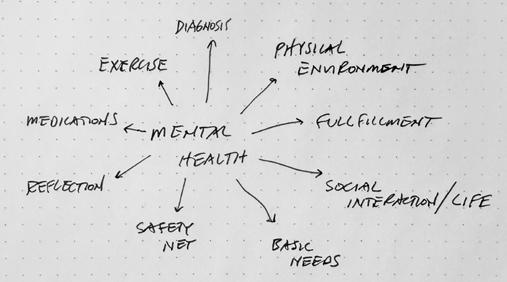

We also examine wellness through the lens of design and business. From Critical Aspects: Experiencing Mental Health, The Future of Human Mobility, and Breaking the Silence: What we Don’t Say Outloud on Burnout, our contributors unpack how systems, firm culture, and urban design can either sustain or strain us.

Articles like Breathe In: Burn Out, The Unapologetic Productivity System, and The Art of Suffering: Lessons from The Summit to the Studio remind us that care starts with setting boundaries and redefining what “enough” looks like.

This issue also celebrates forward movement: Women’s Leadership Summit reflections, the Future Forward Grant recipients research on motherhood and practice, and the Taking Care of Business’s holistic look at shaping successful practice management, all showcase leadership rooted in humanity. Together, these stories reveal that driving wellness isn’t a solo pursuit, it’s a collective recalibration of how we lead, mentor, and design.

As we close the year, may these stories serve as reminders to rest, to reflect, and to reconnect with the parts of this work that first inspired you and to eliminate what is leaving you without passion. The future of our profession depends not just on innovation or efficiency, but on our capacity to stay well enough to imagine what’s next.

In pursuit of wellness, Nicole Becker

Editor in chief / Connection

Take a deep breath.

All nighters are not a badge of honor or pride

Chair’s message: Committed to Designing Wellness

Architecture is a practice, not a profession. Wellness is a discipline, not a destination.

As we close out this year, I find myself holding two truths: this has been a really long year - and a deeply fulfilling one. A year of growth, challenge, inspiration, and,if we’re being honest,a year, like many others, that has left many simply tired. More and more when asking, “How are you?” the collective answer seems to be a familiar sigh of “hanging in there.” This is especially felt among mid-career professionals, many of whom sit squarely in the “sandwich” of the profession. We’re leading projects, managing client relationships, guiding teams, mentoring emerging designers, and simultaneously reaching upward toward leadership. It’s no surprise that the proverbial jelly is squeezing out.

The World Health Organization defines burnout specifically within the context of the workplace1. However, we know burnout arrives long before stepping into the office and lingers long after the workday ends. Many factors - life, culture, society, finance, family, demographics, and more - are the many pieces of this collective puzzle. So when talking about burnout and wellness, the question becomes: How do we build not only psychologically safe environments to talk about these realities, but also shift and shape policies and practices that honor them? How do we redefine the practice of architecture so that it mirrors the discipline of wellness we so often talk about and implement in the built environment, but don’t often enough recognize the impact to those behind the work?

Architecture is a practice, not just a profession.

Wellness is a discipline, not a destination. And to say it bluntly, the all-nighter is not a badge of honor.

my personal and professional wellness. I’m grateful for the hybrid workplace policies that create space and flexibility. For colleagues who offer empathy, patience, and compassion. For the open conversations that replaced “just pushing through” with “how can we support you?”

These changes and the articles you will read, are anything but small. They are honest. They are vulnerable. They are tangible. And they represent something powerful: a profession in motion. A needle moving. A culture shifting. A present practice shaping the future.

As a priority and focus to not just end the year, but be carried through and into the next, the Young Architects Forum is committed to designing wellness as thoughtfully and carefully as we design the built environment. Together, we can redefine the future of architecture; not just through our buildings and those continually engaging in the places and spaces architects design, but through the health and well-being of those who create them. For all who have joined us this year, thank you for showing up. Not just for the profession, but for yourselves, for each other, and for the future we are building together.

Though each of us defines our own boundaries, we also know that wellness in practice does not end with the individual. Our profession must shift—culturally, structurally, and collectively—if we truly want to drive wellness.

As I reflect on the year, this publication, and the stories you will read, I also reflect on my own journey—one of understanding the impacts of chronic burnout while slowly, intentionally reclaiming

With gratitude, Sarah

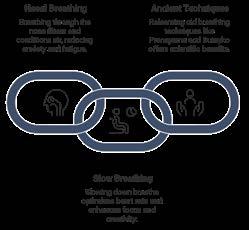

Breathe In: Burn Out

He highlights that mindful breathing during moments of high tension can help us gain composure and clarity.

Key takeaways from his book that we can incorporate in our lifestyle include:

• Breathe through your nose — not your mouth.

• Mouth breathing can contribute to anxiety and fatigue

• Nasal breathing filters, humidifiers and conditions air that improves oxygen circulation that in turn lowers blood pressure and stress

• Slow down your breathing — aim for about 5–6 breaths per minute.

• The “perfect breath” is 5.5 seconds in, 5.5 seconds out

• This optimizes your heart rate and increases focus and creativity

• Relearn old breathing techniques — they’re scientifically sound.

Stress is often seen as an integrated aspect in the field of architecture, embedded in every phase. Tight deadlines, complex coordination, time crunch, pressure to create something innovative and the relentless pursuit of perfection can cause slow and detrimental burn out. And due to our busy schedules, we need something quick and efficient, something that is easily accessible yet powerful that we can integrate effortlessly to contribute to our wellness.

Breath is a beautiful tool that sits at the intersection of an involuntary and voluntary activity. While we do not have to constantly remind ourselves to breathe in order to stay alive, we have the option to control the way we breathe. This aspect makes breath a unique tool that we rely on although we use it every moment, often without noticing.

In the book Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art¹, the author James Nestor reveals that most of us have forgotten how to breathe properly. We have taken breathing for granted which has led us to default to unconscious shallow breathing or mouth breathing. He mentions that this has resulted in the distortion of natural respiratory rhythms and causes us to be in a state of low grade stress that drains focus, energy and creativity.

• Techniques from India - Pranayama, Russia - Buteyko and Tibet - Tummo are great examples of the benefits of breathwork

• These techniques have now been scientifically validated through various research studies such as Yale’s Study on Breath and Mental Health²

Additionally, there are many tools surrounding breathwork that are available that we can learn to incorporate in our daily lives such as podcasts, books, breathwork workshops, videos, etc. Incorporating short breathing shifts in your day can provide you the much needed quick reset, similar to a boost of caffeine!

Breathing doesn’t require extra time or tools - only a gentle awareness is enough. It is like paying attention to detail, something that enhances our daily life, just like details enhance our designs, and luckily we already are trained to do that as a part of our profession.

Footnotes

1. Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art, by James Nestor 2. Yale News, published July 2020

Arti Verma, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C, ALA

Verma is a Project Manager at Dynamik Design in Atlanta, GA. Verma is a licensed Architect and is also a certified breathwork and meditation instructor.

The Art of Suffering: Lessons from the Summit

Mountaineering is the art of suffering. The sooner you decide you like it, the better you’ll be at it.

– Voytek Kurtyka

To most, mountaineering and architecture seem worlds apart. One involves ice axes¹ and crampons²; the other, Revit files and red pens. But in a strange way, the mountains have become my best teacher and my sanity saver in the profession of architecture. Not because they don’t test me, but rather because they do. Learning to embrace suffering isn’t just for the mountains; it’s essential in life and in the creative process of architecture.

What is Suffering?

There are no shortcuts to the top of the mountain or to good architecture. What gets you there is commitment, process, and the ability to endure and transform. Suffering in the mountain context: food poisoning at 15k feet, frozen eyelashes, bone chillingly cold bivouacs3, and terrifying exposure.4 But, architects know their own version all too well: endless iterations, design competitions that go nowhere, and being underestimated in rooms where you should have a voice.

Different gear. Same language.

And somehow, we keep coming back for more. Because through adversity we are shaped.

The Mindset Shift

Every climber has the, “What the hell am I doing here?” moment. The doubt and the discomfort seep in and you wonder if you belong. You wonder if you should quit. I have felt it both on alpine ridgelines and in the office at 2 a.m.. Climbers embrace suffering because it transforms them; architects avoid burnout because it depletes them.

Here’s the critical distinction: suffering and burnout may look alike: exhaustion, frustration, doubt - but they are not the same. Suffering is temporary, purposeful, and sometimes chosen. It sharpens us.

Burnout is chronic, draining, and imposed. It strips away meaning.

The goal isn’t to avoid hard things, it’s to learn which kinds of struggle build you and which break you. There’s an art to that, and both mountaineering and architecture require it. It’s in the alpine starts5 and the harsh critiques, the taped-up blisters and the battle-tested models.

The difference lies in intention: one builds resilience, the other erodes it.

Avoiding Burnout Matters

Architecture is a profession that too often confuses burnout with commitment. We call it a “labor of love”, and we wear exhaustion like a summit flag. But that mindset is not only unsustainable, it’s dangerous.

In mountaineering, ignoring fatigue gets you benighted6, frostbitten, or worse. You learn to respect your limits, listen to your body, and turn back when needed. Not because you’re weak, but because you want to come back stronger. In architecture, we need the same wisdom. When we romanticize overwork, we lose people. We lose talent, creativity, diversity, and perspective. We burn out the very voices we need most, often the ones still fighting just to get on the rope team7

The profession suffers when we define success as summits at any cost. Avoiding burnout isn’t just about surviving, it’s about working smarter, climbing as a team, and creating space for everyone to breathe - because no one gets to the top alone.

Wellness Is Not the Absence of Struggle

Burnout doesn’t just come from long hours, it’s caused by a lack of meaning. If everything feels like drudgery with no payoff, no ownership, or joy, of course you’ll crash.

But when struggle challenges and humbles you, it builds you. Climbers call this “Type 2 fun”- misery that turns into joy in hindsight. The retrospective “I’d do that again” kind of suffering. The kind that makes us stronger, sharper, and more grounded. The healthiest people I know, climbers and creatives alike, don’t avoid stress, they embrace it on their own terms and in ways that align with their values. That’s not burnout. That’s resilience.

Redefining Wellness

Wellness in architecture doesn’t mean yoga at lunch or free snacks in the office (although as a dirtbag climber8, I won’t say no to free food). It means having something outside the profession that lights you up, challenges you in new ways, and allows you to return to your work feeling restored. Something that reminds you that your worth isn’t measured by design awards or billable hours.

For me, that’s mountaineering. For you, it might be music, volunteering, writing, teaching, or activism. The point is: we need

more than architecture. If our entire identity is wrapped up in one thing, we have no perspective when it breaks us.

Wellness is having an impact. Having interests. Having balance. A balance that is dynamic and intentional and leaves room for you to be a human, not just a productive designer.

The Art of Suffering

There’s a strange euphoria in surviving misery. Everything feels earned. Whether it’s watching sunrise from a summit or seeing your design realized in the real world. It’s a joy that only makes sense after the pain.

The suffering becomes the story. It isn’t a side effect; it is the process. Architects and mountaineers are wired to want hard problems. These challenges rewire our threshold for resilience that keeps us coming back for more. Once you’ve stood on a precarious slope, a tough client meeting doesn’t shake you. Every climb, every project, every risk teaches us who we are.

But here’s the reminder: suffering and burnout are not the same. Suffering is temporary, and transformative; it gives back more than it takes. Burnout is imposed, and depleting; it takes until nothing is left. One builds resilience. The other destroys it. It’s

crucial to recognize the difference.

Suffering becomes an art form on the path to building resilience. A practiced elegance in pain. A way of thinking that says: “This is hard. And that’s okay.” Whether it’s a crevasse9 or a critique, true artistry lies in transforming the pain into purpose, so long as that pain is building you and not breaking you.

The sooner we choose to embrace suffering, the sooner we can grow. The sooner we stop just surviving, the sooner we can start crafting something worthy; in the mountains, in architecture, and in life.

Footnotes:

1. “Ice axes” are tools for climbing on ice or steep snow, also for self-arresting (stopping oneself) during a fall.

2. “Crampons” are spiked devices attached to boots to provide traction on snow and ice.

3. “Bivouac” is a temporary, often minimalist overnight camp, usually without a tent, often in high alpine conditions.

4. “Exposure” is a situation on a climb where a fall would be long and dangerous; often deadly and can be described as

feeling very “open” or unprotected.

5. “Alpine start” refers to beginning a climb very early in the morning, typically between midnight and 4:00 a.m., to avoid dangerous afternoon conditions by climbing during the coolest part of the day.

6. “Benighted” refers to getting stuck on a mountain overnight, unintentionally, often due to poor planning or fatigue.

7. “Rope Team” is a group of climbers connected by rope for safety, often in glacier or alpine environments. Implies teamwork and mutual risk.

8. “Dirtbag climber” is a term of endearment in climbing culture referring to someone who devotes a lot of their life to climbing.

9. “Crevasse” is a deep crack or fracture in a glacier caused by movement of the ice.

The Unapologetic Productivity System

How I Found 1,500 Extra Hours to Achieve My #1 Goal

What if I told you that you could find an extra 1,500 hours to achieve your number one goal in the next year?

That’s the equivalent of 62.5 days straight — two full months of time — on top of working a full-time job, maintaining relationships, and keeping your life in order. Sounds impossible, right?

Well… over the course of 1 year, 1 month, and 1 day, I found over 1,500 hours to devote exclusively to studying for the Architect Registration Examination (ARE). In that time, I passed all six divisions and earned my architecture license.

Looking back, even I was shocked by the numbers. But the truth is — it wasn’t magic. I developed a system for evaluating opportunities and making deliberate choices that aligned with my goals. I call it the Unapologetic Productivity System

It’s a way of finding the time you don’t think you have to say “yes” to your goals — by learning to unapologetically say “no” to everything that doesn’t serve them.

How It Started: Tracking Everything

You might be wondering how I know these statistics so precisely.

It’s because I tracked them. Neurotically.

At the beginning of 2018, I decided I was serious about passing the ARE. But life wasn’t slowing down to make it easy. I was working full-time, managing deadlines, client meetings, and travel. My mom had just had surgery, and I was helping her get to physical therapy and doctor’s appointments — all while trying to eat, sleep, and stay sane.

Something had to change.

I needed to get intentional with my schedule, so I started tracking where every hour of my time was going. I shared my schedule with my family to stay accountable, and together we found pockets of time that could be repurposed for studying.

Then, I joined a study bootcamp where we took time tracking to the next level. We logged our study minutes in a shared Excel file, visible to everyone. It became a friendly competition — no

one wanted to be last or called out by the instructor, Michael. That system forced me to get brutally honest about how I spent my time.

And, that’s how I know exactly where those 1,500 hours came from.

The Mindset Shift: From Productive to Unapologetic

Looking back on what worked, I realized that this wasn’t just a productivity system — it was an Unapologetic one.

Because at its core was a simple but powerful habit: a series of questions I asked myself every time an invitation, opportunity, or distraction came my way.

Here’s how it worked:

1. Do I actually want to spend my time on this?

Independent of others’ opinions — is this something I truly want?

• Personal example: When invitations came for distant family events (you know, the third cousin’s BBQ two hours away), I learned to say, “Sorry, not this time.”

• At work example: I paused on taking new roles or responsibilities that would compete with my study schedule. I didn’t need to “advance” in every direction at once.

2. Does this opportunity support my goal — directly or indirectly?

If yes, great. If not, it’s probably a “no.”

• Direct support: Study groups, architecture podcasts, or practice exams.

...be intentional. Every “yes” has a cost - and every “no” creates speace for something that matters.

• Indirect support: Self-care and accountability. For instance, having dinner with friends who respected my study schedule was a “yes.” Going out for late-night drinks with coworkers who didn’t — “nope.”

I’m not saying you should never hang out with coworkers or go to happy hour. But be intentional. Every “yes” has a cost — and every “no” creates space for something that matters.

3. What is the time commitment?

Even a worthwhile opportunity can be too heavy a lift at the wrong time.

• When I was asked to volunteer as an AIA New Jersey Licensing Advisor, the timing overlapped with my final exam. I evaluated it carefully — I was already helping coworkers navigate AXP and licensure questions, and the role only required one committee call a month.

• Worth the time investment. Saying yes to this role has opened doors to additional opportunities over the last 6 years within AIA NJ, the local sections and now on the national level, which otherwise may not have come around. When looking back at the big picture, there was only a 2 month overlap in my studying and service which has turned into a 7 year and going volunteer endeavor.

• Now, I’m proud to say I’m serving my seventh year as Licensing Advisor, have served one term as AIA NJ Treasurer and am in my third year as AIA NJ Young Architect Representative with the Young Architects Forum (YAF).

4. If I say no now, will this opportunity come again?

Some things are once-in-a-lifetime. Most aren’t.

When I got invited to a friend’s wedding across the country during my final testing window, I realized the event itself was nonnegotiable — but how I showed up was flexible. I studied on the plane, reviewed flashcards in the hotel, and stayed mobile with my materials. I showed up for the people I cared about without abandoning my goals.

What You Can Learn From This

The Unapologetic Productivity System isn’t about being rigid or robotic. It’s about being intentional

It’s about realizing that every “no” is really a “yes” to something more important.

Over the course of 13 months, I didn’t just find 1,500 hours — I reclaimed them from distractions, overcommitments, and obligations that didn’t serve my purpose.

So, if you’re staring down a big goal — whether it’s passing the ARE, earning a promotion, or starting something new — start by asking yourself:

“What can I say no to, so I can finally say yes to what matters most?”

That’s the essence of being unapologetically productive.

Abigail Benjamin, AIA, NCARB, CNU-A Benjamin is an Associate Vice President and New Jersey commercial studio leader at AECOM, licensing advisor at AIA New Jersey and the Young Architect Representative for AIA New Jesery.

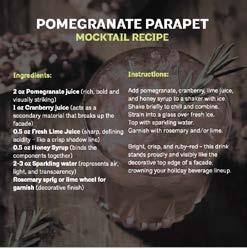

Redefining Productivity Through Wellness

Above: Wellness and work in sync — where creativity and performance thrive together. (Graphic created by the author)

In the architecture profession, demanding deadlines, client expectations, and project goals often drive us to stay glued to our desks for long hours. Many professionals push through the day without taking breaks, convinced that constant effort equals productivity. But our bodies weren’t designed to sit all day and neither were our minds. To truly perform well and deliver great work, we need to find balance, or better yet, harmony, the space where wellness and performance meet.

Research shows that rest, movement, and intentional downtime don’t slow us down, but instead make us sharper, more creative, and more capable over time (Greater Good Science Center, 2024)¹. For architects, whose work demands both technical precision and creative vision, redefining productivity through wellness isn’t a luxury—it’s essential for sustainable success.

Research shows that rest, movement, and intentional downtime don’t slow us down, but instead make us sharper, more creative and more capable over time...

What the Research Says

1. Rest Fuels Creativity

Rest isn’t wasted time; it’s part of the creative process. A Stanford study found that people who walked produced twice as many creative ideas as those who remained seated (Oppezzo & Schwartz, 2014)². Even a brief nap can enhance problem-solving; dipping into the first stage of sleep can triple creative insight (Lo et al., 2023)³.

In practice, this means giving yourself permission to pause—take a short walk, stretch, or step away from the screen. That “lost” time often leads to better and faster design thinking when you return.

2. The Power of Downtime

In a profession that prizes constant focus, true rest can feel uncomfortable. Yet research shows that daydreaming and mental breaks allow our brains to form new connections (Rominger, Fink, & Weiss, 2024)⁴. Psychologists call this the incubation effect. When you stop thinking about a problem, your subconscious keeps working on it (Wilson, 2024)⁵. This is why ideas often strike in the shower or during your commute.

3. Movement and Hydration Boost Focus

Staying hydrated, moving around, and stretching throughout the day play a huge role in our performance and health. Movement isn’t just for fitness—it’s a creative and mental reset. Short walks, stretch breaks, or even walking meetings can restore focus and energy (Van der Zee, 2024)⁶. Microbreaks also help reduce fatigue and sustain attention throughout the day (Greater Good Science Center, 2024)¹.

4. Boundaries Prevent Burnout

Constantly saying “yes” can lead to exhaustion. Burnout often happens when boundaries blur and we feel we must always be “on.” Executive coach Molly Wilding (2025)⁷ suggests doing a “resentment audit”, or paying attention to moments of frustration or fatigue, which often signal where limits need to be reset. Setting boundaries protects your creativity and long-term motivation.

Conclusion

Redefining productivity through wellness means shifting our work attitude from constant output to sustainable creativity. Staying hydrated, moving, stretching, resting, and getting enough sleep are small actions that make a big difference. When we take care of our bodies and minds, we bring our best selves to the drawing board.

For architects and designers, wellness is not separate from good design—it fuels it. By prioritizing balance, we don’t just create better work; we create better lives.

Practical Strategies

Strategy

Why It Helps

Scheduled Rest Breaks Keeps energy and focus steady throught the day

Power Naps & Good Sleep Boosts creativity, memory, and problem-solving

Walking, Stretching, & Hydration Improves mood, focus, and overall health

Mindful Rests & Idleness Encourages fresh ideas and mental clarity

Clear Boundaries Reduces burnout and maintains motivation

Supportive Firm Culture Promotes lasting wellness across teams

Resources

1. Greater Good Science Center. (2024). The Science of Rest and Renewal.

2. Oppezzo, M., & Schwartz, D. L. (2014). Give your ideas some legs: The positive effect of walking on creative thinking. Stanford University.

3. Lo, J. C., et al. (2023). Napping and Creative Insight. Nature Scientific Reports.

4. Rominger, C., Fink, A., & Weiss, E. M. (2024). MindWandering and Creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts.

5. Wilson, T. (2024). The Incubation Effect and Creative Problem Solving. Journal of Applied Psychology.

6. Van der Zee, E. (2024). The Connection Between Movement and Creativity. European Journal of Behavioral Science.

7. Wilding, M. (2025). The Resentment Audit: Reclaiming Energy and Focus. Harvard Business Review.

Isabel Souza, Assoc. AIA, NOMA

Isabel is a design professional with 10+ years in the AEC industry, working at PMBA Architects in Ohio. She’s pursuing licensure and is committed to creating innovative and impactful design solutions.

From Moments to Movements

Four architects on the sparks that shaped their call to lead, and the movements they’re building now.

Architecture is often seen as a profession of permanence - concrete, steel, and glass. But for many designers, the foundation is built far earlier: in classrooms where their names were mispronounced, among neighborhoods no one cared to map, or within family histories etched in resilience.

In this feature, four architects reflect on the moments that lit the fuse: Brien, Shadia, Richie, and Samantha. Before the board appointments and keynote stages, and before the awards and the advocacy, there were pivotal memories that sparked something deeper. This is where their movements began.

This is how their sparks ignited.

Architecture Should Always Be About the People Brien Graham, AIA, NOMA, NCARB

“The combination of architecture and advocacy has been a culmination of pivotal moments throughout my career,” says Brien Graham. But two memories stand out.

The first: being a young boy, living in a neighborhood where voices weren’t invited, only impacted. “[I realized] the lack of residents’ input in my neighborhood to voice concerns or desires about the spaces we wanted to inhabit.”

The second: realizing the immense power of architecture to shape people’s daily lives.

That contrast, between disempowerment and potential, sparked something that would define Brien’s path forward. Growing up in public housing, he recalls the coldness not just in concrete walls and tile floors, but in the environment itself. “It didn’t exude joy,” he says. “It fostered symptoms of hopelessness.” That’s when he began to understand the power of place.

And it’s what anchors his work today, as the Civic, Municipal, and Cultural Market Leader for KAI Design, as Texas’ representative on the AIA Strategic Council, and as the South Region VP for the National Organization of Minority Architects. Every project is guided by one clear belief: Architecture should always be of, for, and about the people.

Architecture should always be of, for, and about the people.

“I’ve made it my personal mission to use joy as a motivator and hope as an aspiration,” he says. “To provide spaces where people can enjoy, grow, thrive and spark the next changemaker.” Because the truth is, design doesn’t reflect value, it sets it. And Brien’s work makes it clear: communities deserve to be at the center of the process. Not afterthoughts. Not outsiders. Authors.

It’s Not Just About the Building Shadia Jaramillo AIA, WELL AP

The lesson was deceptively simple. “If an architect designs even one stair rise at a different height, it could affect someone physically for life.” It’s a line Shadia Jaramillo, AIA, WELL AP, will never forget, spoken by a professor in a prospective class

back in Panama. This lesson was beyond technical instruction. It was the first moment she truly understood the weight of the architect’s responsibility, that design decisions ripple far beyond the drawing set.

“That moment defined my purpose,” she reflects. “That lesson revealed how deeply our decisions shape human experience.” For Shadia, architecture is not simply about completing buildings. It’s about crafting experiences, and ensuring that clients, users, and communities feel acknowledged, supported, and connected. That awareness has been the foundation of her leadership ever since.

Today, Shadia is based in Pensacola, Florida, with a diverse portfolio spanning residential, commercial, healthcare, higher ed, and civic design. But just as powerful as her built work is her commitment to the people behind it: empowering professionals, mentoring emerging leaders, and serving as a passionate advocate for volunteer leadership.

“The value of our work extends far beyond what we can fully grasp,” she says. “my purpose has centered on more than tangible outcomes; it’s about the people behind them and the awareness that every choice I make carries the power to influence and impact someone’s life.” That, for Shadia, is what gives architecture meaning. It’s not just about shaping space, it’s about shaping meaning across generations.

It’s not just about shaping space, it’s about shaping meaning across generations.

Mentorship Was the Door That Opened Everything

In the early years of Richie Hands’ career, it wasn’t a title or a project that changed everything, it was two people. Jason Pugh and Oz Ortega saw something in him, and more importantly, they made sure he saw it too.

“They didn’t just mentor me,” Richie says. “They looped me

in. Pulled up a chair. Made sure I had a seat at the table—and the confidence to speak up once I was there.” That quiet act of inclusion unlocked something. Because once you’ve felt the impact of being seen, you start to see others differently too. “It helped expand my career,” he says, “but it also helped form the foundation of what I find to be incredibly rewarding and engaging: mentoring the next generation.”

I know how much representation matters. It’s not just about access, it’s about belief.

That calling led him to Project Pipeline and ACE Chicago, where he worked with students who looked like him, came from where he came from, and who might not have otherwise known that architecture was for them. “It afforded me the opportunity to offer advice to students from communities that are still largely underrepresented in the profession,” Richie shares. “I know how much representation matters. It’s not just about access, it’s about belief.”

Now, Richie serves as National Chair of Project Pipeline, shaping programming and outreach for future architects across the country. He’s also a Director on the ACE Chicago Executive Board, and the acting VP of Membership and Secretary for AIA Chicago. The same tables he was once invited into, he’s now building for others.

“These opportunities only happened,” he reflects, “because I was surrounded by exceptional NOMA mentors and heavily involved in those communities.” What started with one door opening has turned into Richie holding space open for hundreds more. And the movement? It’s growing.

Designing Spaces That Shape Belonging Samantha Markham, AIA

“The moment that first sparked my purpose happened during the community opening of a junior high we had fully renovated,” says Samantha Markham. It wasn’t the construction milestones or the polished finishes that stayed with her. It was the people.

She remembers standing in the hallway, watching students, parents, and teachers step into their transformed spaces for the first time. “Their reactions shifted from surprise, to pride, to pure joy,” she says. In that instant, Samantha understood that architecture isn’t only about buildings, it’s about daily lives. It’s about crafting environments where people feel seen, supported, and valued.

That realization became the throughline of her work. As the North Texas K–12 Market Leader at Stantec, Samantha leads with that same clarity of purpose, balancing technical expertise with a deep commitment to community. Her leadership extends far beyond the firm: through the ACE Mentor Program, AIA, and A4LE, she’s helped hundreds of students step into their own confidence and potential.

“As my career grew, that same spark pushed me toward mentorship,” she reflects. Investing in high school students, sharing the possibilities of the profession, and helping them find their voice became as essential as any design project. Years later, watching those students enter the industry, mentor others, and give back to their communities, Samantha experienced a full-circle moment that reaffirmed everything she believed. “The impact becomes exponential,” she says, “when we help the next generation realize their potential.”

. . . architecture isn’t only about buildings, it’s about daily lives. It’s about crafting environments where people feel seen, supported, and valued.

These aren’t just stories of architects. They’re stories of sparked purpose turned into lasting impact. Each of these leaders, Brien, Shadia, Richie, Samantha, chose to answer the call not just to build, but to build differently. To shape spaces with empathy. To mentor with intention. To center people in every elevation.

If you’re reading this and feeling a pull, don’t ignore it. Start with your moment. Trace it back. What ignited your passion? What change are you uniquely positioned to lead? Because movements don’t start with titles. They start with you.

Those early experiences moved her from simply practicing architecture to shaping movements around design, equity, and leadership. They taught her that this work extends beyond a single school or program. It’s about building systems, opportunities, and spaces where people can thrive.

“That purpose has guided every step of my journey,” Samantha says, “and it continues to drive the work I hope to elevate across our profession.”

Gabriella Bermea, AIA

Bermea is a senior associate and project manager at Perkins Eastman in Austin, TX, where she speacializes in Pre-k - 12 educational facilities. She is a co-chair of NOMA National’s Elevate Committee.

Colleague to Colleague (C2C) Mentorship Program AIA Academy

of Architecture for Health

Healthcare architecture is the specialized design of spaces like hospitals, clinics, and medical offices to support patient healing and staff efficiency. It focuses on patient-centered design, functional and efficient planning, healing environments and community well-being.

The Colleague 2 Colleague (C2C) Mentorship Program is the mentoring program of the AIA Academy of Architecture for Health. It’s an online program targeting design professionals who are new or early in their careers with an interest in healthcare architecture, planning, and design. It’s a 10-month program from March to December, with presentations and discussions around the topics of healthcare architecture, planning, design, and career development.

The mission is to empower a diverse cross-section of professionals within the health design field through an intentional community fostering growth, networking, and leadership creation.

Commitment

• Two (2) online meetings a month, one (1) hour each.

• Previewing material speakers might send in advance.

• Willingness to join the conversation, participate in group discussions, and be open to networking and connecting within your mentoring Pod and within the larger group online

“All the sessions I participated in thus far have been incredibly enlightening. Not only are the topics well-structured for open discussions, but what I find far more enjoyable is learning through getting this one-on-one experience with all the mentors and mentees”.

- C2C participant

Mentoring Candidate (Mentee) Qualifications

• Students in their final year of a professional or postprofessional degree in architecture.

• Less than 10 years total work experience starting from graduation with a NAAB accredited degree or on an NCARB equivalency path.

• Strong interest in healthcare architecture, planning, and design.

Mentee Candidate Application criteria

• One (1) page letter from your supervisor or faculty lead on firm or school letterhead, recommending you for the program and agreeing to support your commitment for two

(2) hours a month for your participation in this program.

• Half page CV/Resume.

• Half page essay (200-word max) describing your interest in this mentoring program and your willingness to commit to the two (2) meetings per month.

2026 Application Timeline:

• December 1, 2025: Application process opens.

• January 23, 2026: All Applications are due.

• February 2026: Selection. Accepted candidates will receive an email notification and program details.

• March 2026: Program kick-off with schedule of all sessions for the mentoring year.

• December 2026: Final session.

“All the topics were well done and insightful. Keep this program going. I am so happy I was involved in this program!”. - C2C participant

Applications can be submitted through this jotform on the AIA AAH C2C webpage.

If you are interested in knowing more about the AAH Knowledge Community or have questions about C2C, please send an email to Isabella Rosse IsabellaRosse@aia.org and put C2C 2026 in the subject line.

Vince Avallone, AIA, FACHA, CASp, LEED AP is a Vice President and Director of Medical Planning at SmithGroup based in San Francisco. Among his 30+ years in healthcare architecture, Vince has led projects in roles such as principal-in-charge, senior medical planner/programmer, project manager, and project architect.

How Do We Grow New Architects?

Previously Published in COF Quarterly Q3 2025

How Do We Grow New Architects?

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” is a question often answered with well-known and shared professions like teacher, firefighter, policeman, doctor, sports star, and even YouTuber. Less talked about professions, like architecture, design, and engineering aren’t exposed to younger audiences who may very well develop a love and interest for these and other STEM careers early on in their lives.

The Architecture Job Market Gap

In regard to architecture, as of 2025, there were about 116,000 working architects in the United States, according to the National Council of Architecture Registration Boards. There are about 8,500 openings for architects each year and many of those are expected to result from a need to replace workers who exit the workforce, often for reasons such as retirement.

K-12 mentorship programs are critical to reach students at all levels to expose them to architecture and design.

This is to say that architecture is a field that requires constant

pruning, much like a prized plant. To meet the output necessary for architectural positions — which are undeniably essential for urban planning and development, historic preservation, business development and growth, and residential development — there must be a consistent watering, trimming, and propagation of architects to meet the demands of the world.

As we know, becoming an architect often takes years and includes schooling, on-the-job experience, and licensure, which further complicates the job market. Those who may be interested in this creative, strategic, rewarding, and stable profession are required to begin planning accordingly, years in advance, which brings to light the need for early architectural mentorship.

The Importance of K-12 Architectural Mentorship

I decided to be an architect in seventh grade, even though I didn’t know a single architect. If it wasn’t for my seventh-grade shop teacher who assigned us to hand draft stacks of blocks, learning the basics of plan, elevation, and isometric drawings, I might never have known architecture was an option for me. Well, there was also the fact that I loved drawing out a house plan or planning out my bedroom furniture as a kid, but other children may engage in these kinds of activities without understanding that this creative practice could develop into an affinity for architecture.

Luckily, my father knew some architecture students in college and as such was quite encouraging to me in my pursuits. As previously mentioned, children are unable to explore fields they aren’t exposed to. K-12 mentorship programs are critical to reach students at all levels to expose them to architecture and design. This is why I, and Cushing Terrell, participate in educational initiatives and volunteering efforts for schools.

Mentorship Programs for Children and Teens

One such program, which is nearing an almost 30-year partnership with Cushing Terrell, is our support of Newman Elementary School. What started as reading fluency support has now expanded to mathematical enrichment and other STEM activities. It’s during these interactions with kids that I make sure to introduce myself as an architect and explain what my job is just in case there’s another little one out there who has never heard of the wonderful world of architecture. You never know who may be sparked by those conversations.

Additionally, programs exist like:

• ACE Mentor Program

• For highschoolers across the country to learn about architecture, engineering, and construction

• NOMA Project Pipeline

• Gives 6th-12th grade students of color the opportunity to learn the fundamentals of architecture and design

• AIA Dallas Designing My Future

• A hands-on program that teaches students ages 6-18 about the world of architecture and design

• AIA New York Summer Programs

• Week-long classes for students in 3rd grade through 12th that are held at the Center for Architecture

If you don’t live near one of these programs, there are still chances for you to get involved. You can reach out to a local school, Girl or Boy Scouts troop, etc. to find out how you can help. AIA has many child-centric resources on “What is an Architect?” as well as specific lesson plans and worksheets for K-5 and grade 6-12 classroom projects that are ready to go for instant architectural engagement.

Mentoring Architecture at the College Level

What’s more, you can connect with local colleges or universities to encourage students to keep up their studies and remind them why they started in the first place. Sometimes, when you’re in the thick of mid-terms, studio deadlines, and finals you need that extra push of encouragement and the spark of desire to reignite your “why” and follow through on your aspirations — and not every student, especially those who are very new to the field, has that built-in support system. Things that have beneficial outcomes can be challenging to keep up with and sometimes, it just takes that one impactful voice to set someone up for success.

It’s during... these interactions with kids that I make sure to introduce myself as an architect and explain what my job is just in case there’s [a child] who has never heard of... architcture

Programs such as the Wing Mentorship from AIA Chicago and AIA Atlanta Student Mentorship Program pair architecture students with working professionals, letting them see

Connection

architecture in practice and can help young people truly envision it as a viable career.

Furthermore, universities may have an advisory council that connects professionals with students. For example, the AIA Montana School of Architecture Advisory Council hosts formal, one-on-one and informal mentorship opportunities. These mentoring sessions may include panel discussions, resume and portfolio workshops, networking events, mock-interviewing, and more.

Becoming a mentor for young architects can be as fulfilling and rewarding as you make it. It may be as simple as providing a firm tour and making yourself available for questions or interviews, or as deep as one-on-one mentoring and becoming a pillar of architectural education to your local K-12 community and beyond.

Christensen is an architect and principal at

where she specializes in commercial architecture, with a focus on the design and construction of financial institutions.

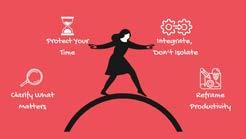

Designing Balance Between Work, Service, and Self

In architecture, “work-life balance” often feels like a myth. Between demanding projects, volunteer roles, and personal commitments, we are constantly negotiating time and energy.

The challenge is not that balance is impossible; it is that our definition of it is too limited. Work-life balance and time management are a never-ending study, one that evolves with every stage of our careers and personal lives.

As architects and designers, we are trained to synthesize complexity into coherence. Yet in our own lives, we often separate work, service, and self into competing priorities. What if wellness is not about dividing time evenly, but aligning choices with values?

The Myth of “Having It All”

Early in my career, I held the belief many young designers share: that passion equals endless endurance. I thought that to

succeed, I needed to excel at work, stay engaged in volunteer leadership, nurture creative interests, and remain emotionally present for family living thousands of miles away. Like many, I thought being busy was proof of commitment.

But “having it all” often translates to “doing it all, all the time.” And the traditional mindset of the profession, “you can do it all if you work hard enough”, reinforces it. Many firms today are adopting healthier practices such as flexible schedules, implementing mental-health initiatives, and hybrid workweeks. The personal rewiring required to break old habits takes far longer than policy changes, though.

...wellness is not the absences of stress; it is the ability to understand which pressures are necessary and which are negotiable.

Above:

The pandemic intensified this misalignment. Work seeped into evenings, weekends, and the emotional spaces where rest should have been. I realized that wellness is not the absence of stress; it is the ability to understand which pressures are necessary and which are negotiable.

Navigating Expectations as an Immigrant Woman

For many immigrants, ambition is shaped by sacrifice. We leave home, start over, and internalize the belief that endurance equals worth. Saying no can feel like disappointing not just a colleague but an entire family watching and cheering from afar.

The emotional labor multiplies, navigating two cultural worlds, managing time zones across continents, and constantly proving credibility in spaces where few people share your lived experience.

Over time, I learned that boundaries do not signal a lack of commitment. They signal sustainability. When I began communicating my limits clearly, people respected them. I reclaimed agency over my schedule and well-being.

...boundaries do not signal a lack of commitment. They signal sustainability.

My community strengthened that shift. Connections formed through AIA committees, the Women’s Leadership Summit, the AIA National Associates Committee, and the Immigrant Architects Coalition reminded

Above:

me that shared purpose sustains us when individual capacity wears thin. Mentorship became more than service; it became a wellness practice. It replaced isolation with belonging. Yet the profession still lacks adequate support systems. Nearly 25 percent of architecture graduates in the U.S. are international students¹, but few structured resources exist to guide their cultural, emotional, and professional transitions. If our profession values diversity, it must also value support.

From Balance to Alignment

Success in Architecture is often measured by outputs like projects completed, awards won, and committees joined. But wellness demands a shift in priorities from performance to presence.

The question is not “How do I balance everything?” The question is “How do I align what I do with what matters most?”

Below are the approaches that reshaped my own rhythm.

How do I align what I do with what matters most?

Clarify What Matters

Once a year, I list every role I hold and evaluate whether each one still aligns with my priorities and values. Anything that feels purely transactional deserves reevaluation.

Protect Your Time (and Your Health)

Time is the first boundary of wellbeing. There are seasons of growth, rest, and transition. During project-heavy months, I scale back on volunteer work; when deadlines ease, I re-engage. This rhythm replaces guilt with grace. I also maintain “no-work zones” such as Sunday calls with family, board-game/ movie nights, or writing hours.

Integrate, Do not Isolate

Intersection enriches impact. Rather than treating professional and volunteer worlds as separate, I look for ways to let them inform one another. Many of my closest friends are also colleagues, mentors, or collaborators. Allowing work and service to intersect creates a holistic sense of purpose instead of compartmentalized pressure.

Reframe Productivity

In design, we celebrate iteration, yet in life, we chase output. Redefining productivity as intentional alignment rather than task accumulation creates space for creativity and rest.

Designing a Roadmap to Thrive

Thriving today means designing systems where ambition and well-being can coexist. The roadmap is not fixed; it evolves with every stage of our careers.

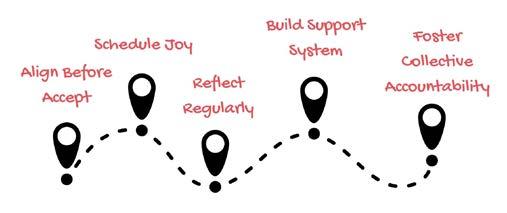

• Align Before You Accept: Ask whether the opportunity supports your core values, not just your résumé.

• Schedule Joy: We schedule deadlines and deliverables, but joy must also be intentional. Connection is fuel, not a distraction.

• Reflect Regularly: Check whether you feel energized or depleted. Adjust without guilt.

• Build Support Systems: Surround yourself with mentors, peers, and friends who can remind you of perspective when the pace accelerates.

• Foster Collective Accountability: Wellness should not be an individual burden. When leaders model balance, it becomes culture.

From Individual to Collective Wellness

Redefining balance is not just an individual act; it is a cultural one. As firms, institutions, and mentors, we have the power to model healthier practices and dismantle the idea that exhaustion is proof of passion.²

We cannot pour from an empty pot. But when we fill it with purpose, connection, and clarity, the impact extends far beyond our own careers.

Volunteerism, mentorship, and community care remind us that giving back can also restore. Collective care sustains creativity and ensures that purpose does not come at the cost of health.

We cannot pour from an empty pot. But when we fill it with purpose, connection, and clarity, the impact extends far beyond our own careers. Balance, like any well-designed space, emerges through iteration, one decision, one boundary, one breath at a time.

Footnotes

1. 2024 NAAB Annual Report

2. Guides for Equitable Practice

Saakshi Terway, Assoc. AIA

Terway is a Design Professional at Quinn Evans, the 2025 Associate Representative on the AIA Strategic Council, and Secretary of the Immigrant Architects Coalition.

Motherhood as a Catalyst for Redefining Care and Wellness in Architecture

Architecture is a profession built on endurance. From design school to licensure, we’re conditioned to equate passion with overextension, to push harder, stay later, and deliver more. This culture leaves little room for wellness, especially for mothers who navigate two full-time responsibilities: the work of caregiving and the work of creation.

Having my first child magnified these tensions but also clarified a personal question: How can I redefine success in ways that sustain both my practice and my well-being? When I became pregnant during the beginning of the pandemic, as the world stood still, I began reflecting on my career and sense of purpose. I realized I had been chasing deadlines and milestones - licensure, higher salary, more prestigious job title - believing they were prerequisites for starting a family. But when I finally became a mother, my world didn’t just shift; it completely reframed how I saw my profession.

Architecture had taught me to manage complexity and lead with precision, but motherhood taught me something the studio rarely emphasized: the necessity of self-care. Balancing late-night feedings with early-morning meetings revealed a truth many in our field quietly live with. Burnout isn’t a badge of honor; it’s a symptom of imbalance. Motherhood is not a detour from architecture, it’s a framework for resilience, creativity, and empathy . It demands boundaries and redefines what “productive” truly means. With that realization, wellness becomes not just a personal pursuit but a collective responsibility, challenging us to design workplaces as thoughtfully as we design buildings.

Architecture has long celebrated the myth of the tireless designer, the one who outlasts deadlines, perfects every detail, and proves devotion through exhaustion. From studio to practice, we inherit an unspoken expectation that creativity thrives under pressure. Yet behind every all-nighter lies a quieter truth: burnout is not a personal

weakness but a flaw in how the profession measures success. The culture of “more” - more projects, more hours, more outputrewards endurance over empathy. Mothers feel this most acutely. They navigate rigid timelines while managing the unpredictability of caregiving, often within systems that offer limited parental leave, inflexible schedules, and little recognition for the demands of family life. The profession still operates on a false comparison: you’re either “all in” or “not passionate enough.”

The result is chronic burnout disguised as dedication. According to the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture’s (ACSA) Where Are My People? study, women, particularly caregivers, continue to leave the profession at higher rates, citing inflexible structures and unsustainable expectations. The pinch points remain: licensure, caregiving, and the glass ceiling. Many leave before completing licensure, not from lack of talent, but from lack of support. This loss is cultural as much as personal. When we lose mothers and caregivers from practice, we lose perspectives attuned to balance, adaptability, and human-centered design.

During my first year back from parental leave, I struggled to find balance. To mitigate burnout, I had to reevaluate what success looked like and ask harder questions about how we work. Who sets the pace? How is commitment defined? What would it look like if architecture valued sustainability not only in buildings, but in people? Until these questions are part of our design process, burnout will remain embedded in our deliverables.

Motherhood is an exercise in adaptability. It teaches patience amid uncertainty, resourcefulness in constraint, and compassion in chaos - skills architecture demands, but rarely rewards. While firms often define wellness through benefits or billable hours, mothers redefine it through balance: the negotiation between caring for others and caring for oneself, between ambition and sustainment. Returning to work after maternity leave, I began to see wellness not as an individual pursuit but as a shared design problem. Remote work revealed that flexibility isn’t a luxury, it’s infrastructure. Supportive leadership isn’t optional, it’s structural integrity. If design is the thoughtful arrangement of relationships, then designing for wellness means reimagining how those relationships functionbetween colleagues, clients, and time itself.

Motherhood also reframes productivity. It challenges the assumption that value lies in visible hours rather than meaningful outcomes. Many mothers learn to work with sharper focus, deeper empathy, and a clearer sense of purpose, qualities that strengthen teams and elevate design culture. When firms recognize these traits rather than penalize them, they create environments that are more humane, resilient, and inclusive.

Since the pandemic, small but powerful shifts have begun. Firms experimenting with flexible schedules, hybrid options, and transparent expectations are seeing better morale and retention. Peer networks and caregiver resource groups provide validation and support, proving that wellness is not found in isolation but in community. The lessons of motherhood, empathy, adaptability, and care, when embraced by practice, can help us design cultures that value both creativity and well-being as professional strengths.

If architecture is about creating environments that support human experience, then our workplaces should reflect the same principles. Designing a culture of care means rethinking how we structure time, define value, and support one another. It means moving beyond wellness as an individual responsibility, something managed in the margins, toward wellness as an organizational ethic woven into practice.

A culture of care begins with leadership. When firm leaders model empathy, set boundaries, and acknowledge capacity, they normalize care as part of professional excellence. Simple actsasking “How are you doing?” and truly listening - build trust and safety, the foundation for creativity and collaboration. But intention isn’t enough; systemic care requires policy. Flexible schedules, equitable parental leave, and return-to-work programs should be standard, not special accommodations. These aren’t perks; they are essential tools for equity and retention. The pandemic proved that flexibility can drive efficiency and loyalty while diversifying leadership pipelines.

We also need to measure wellness differently. Instead of equating success with output, we can measure sustainability: how supported employees feel, how equitably work is distributed, and how healthy teams remain over time. Some firms now include wellness metrics in project planning or create peer “care councils” to monitor workload and culture.

Ultimately, designing a culture of care asks us to apply design thinking inward - to our firms, our teams, and ourselves. Wellness becomes a form of architectural integrity; a measure of how well our practices serve the people who sustain them.

Motherhood has taught me that wellness isn’t found in stillness alone, but in support, in caring for others while being cared for in return. Architecture thrives on collaboration; our best work emerges from trust and collective intelligence. The same must be true for how we sustain ourselves within the profession.

Burnout isn’t inevitable; it’s the product of systems never designed for care. Like any flawed design, it can be reimagined.

To truly advance wellness, we must broaden its definition beyond self-preservation. True wellness is systemic, reflected in how firms distribute work, how leaders set expectations, and how teams support one another. It’s not about merely surviving the work but cultivating the conditions to thrive within it.

When mothers, caregivers, and advocates challenge the norms that equate overwork with excellence, they’re not asking for less commitment to architecture, they’re asking for a more sustainable one. Our lived experiences offer a perspective for designing practices that value empathy, flexibility, and longevity as essential measures of success. Care is not an interruption to the profession; it is the foundation upon which its future can be built.

The Future of Human Mobility: Why the Humble Shower is the Hidden Key to an Active Workforce

In the United States, a nation saturated with fitness facilities and dedicated exercise spaces, a striking paradox exists: according to the CDC, only about 25.5% of American adults meet the guidelines for both aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities. We have the infrastructure for fitness, but we lack participation. The question is, why? The answer may not be found in a new workout trend or a high-tech gym, but in a far simpler, oftenoverlooked amenity: the shower. As our cities evolve, the shower is emerging as the hidden key to unlocking the future of human mobility and wellness.

A Commuter’s Dilemma: My Story

As a passionate urbanist trained to understand the dynamics of city life, I put theory into practice by commuting via bicycle in Panama City. The experience was an immediate lesson in the practical barriers to active mobility. The tropical climate meant that rain was a frequent challenge, but the most common questions from my colleagues were not about safety or traffic, but about logistics: “What about the sweat? What do you do when it rains?”

I was the only person in my office who biked to work. On dry days, I could manage by changing my shirt in the restroom, as I don’t sweat heavily. But when it rained during my morning commute, my choice was stark: either turn back, go home to shower, and arrive late to work by car, or not bike at all. The evening commute was different; rain was no obstacle, as a refreshing shower was waiting for me at home.

This personal experience highlights a universal truth: the primary deterrent to active commuting for many professionals isn’t the physical effort, but the logistical nightmare of arriving at work sweaty, damp, or disheveled.

The Modern Workplace and the Exercise Paradox

Many people find it difficult to plan physical activity after a long day at work. Morning exercise is often a more viable option. Logistically, it makes more sense to exercise near your workplace than your home. Consider the time saved: you can leave home at 6:30 AM, arrive at a park or fitness facility near your office by 6:45 AM, enjoy a full hour of exercise, and still have time to prepare for the workday. This strategy allows you to bypass the stress and variability of peak rush-hour traffic.But this perfect scenario hits a wall with one simple question: Where do I take a shower?

This is the root cause of inactivity that many people don’t even recognize. Without access to showers at or near the office, employees are forced to either wake up significantly earlier to exercise and commute from home during rush hour, or forgo morning activity altogether. Showers in the workplace fundamentally change this dynamic. They empower people to:

• Commute actively: Bike, jog, or walk to work, eliminating concerns about sweat in the summer or rain and snow in the winter.

• Utilize urban spaces: Take advantage of nearby parks, running trails, or even boutique gyms that may not offer their own shower facilities.

Designing for Wellness: Building Codes and the WELL Standard

If we are serious about fostering a healthier, more active population, we must integrate wellness into the very fabric of our buildings. This begins with updating building codes to encourage or even mandate the inclusion of showers and changing facilities in new commercial developments.

This concept is already a cornerstone of leading-edge design philosophies like the WELL Building Standard. WELL is a performance-based certification that measures, monitors, and verifies features of the built environment that impact human health and well-being. Within its “Movement” concept, WELL specifically rewards projects that provide dedicated support for active transportation. Feature V05: Active Transportation Support often requires the implementation of secure bicycle storage and, crucially, corresponding shower and changing facilities.

By pursuing WELL Certification, companies signal a genuine commitment to employee health that goes beyond superficial perks. They recognize that enabling physical activity is as critical as providing an ergonomic chair or good lighting.

A Call for a Mindset Shift

The solution to our exercise deficit is not another subsidized gym membership that goes unused. The solution is removing the most significant practical barrier.

• For Employees: The next time your Human Resources department surveys wellness needs, ask for a shower and changing facilities. It is a one-time investment that provides a permanent solution, empowering you to integrate activity into your daily life on your own terms.

• For Architects and Owners: When designing a new office space, resist the urge to simply install a small, private gym. Instead, invest in high-quality, spacious showers and changing facilities. This single amenity unlocks the entire city as a potential gym. It is a more cost-effective and utilitarian solution than purchasing some treadmills that see limited use. By solving the root cause, you provide your workforce with a place to refresh and prepare for the day, fostering productivity, health, and morale.

In conclusion, the future of human mobility is not just about bike lanes, electric cars or hyperloops; it’s about enabling humanpowered movement. The humble shower is not a luxury—it is a piece of critical infrastructure for wellness. By prioritizing it in our workplaces and building codes, we can finally begin to close the gap between our fitness ambitions and our daily reality.

Resources: Healthy People 2030

Manuel Granja, AIA, LEED AP, WEEL AP, MBA is a Project Architect at Mt Studio in Troy OH. He serves as a National Associate Representative of AIA Ohio and Co-Chair of the Urban Design Committee in Cincinnati. Granja is interested in fitness and human mobility in the architecture environment.

Women’s Leadership Summit 2025, Atlanta GA: A Recap

The 11th edition of the Women’s Leadership Summit 2025 took place in Atlanta, GA on November 3-5 inside the Marriott Marquis Hotel designed by distinguished architect John Portman. This conference being held in the soaring atrium of this iconic hotel was almost symbolic, women in AEC inhabiting a building that has pushed the boundaries of hotel and atrium design, to gather and talk about leadership, ambition and the future of women in the profession. With almost 1000 attendees this year, this conference has evolved into the biggest gathering of women in AEC that provides a unique stage and a safe space for women to discuss challenges that are unique to them.

The learning tracks for the 2025 WLS Conference spanned across leadership, wellness, designing equitable practice, money making, and navigating the mid-career slump. These themes were explored through keynotes, round tables, breakout sessions, talks, walking tours, firm visits, and networking - engaging women at every stage of their careers, from early to mid-career professionals to seasoned architects and firm leaders.

The Summit opened with the “Executive Leadership Roundtable” which was a hands-on session for senior firm leaders to navigate today’s complex professional landscape. Attendees discussed the emerging issues in the profession including advocating for leadership roles for women, sustainability, emerging technologies like AI, DEI policies, and many more. After this collaborative workshop, attendees returned with actionable takeaways to drive meaningful change in their firms.