The architecture and design journal of the Young Architects

The architecture and design journal of the Young Architects

Issue 03 celebrates a generation of architects who aren’t just adapting to change, but boldly steering the profession forward. From redefining career paths to amplifying diverse voices, these stories remind us that the future of architecture is ours to imagine—and to drive.

2025 Chair

2025 Vice Chair

2025 Past Chair

2025-2026 Advocacy Director

2025-2026 Communications Director

2024-2025 Community Director

2025-2026 Knowledge Director

2024-2025 Strategic Vision Director

2025 AIA Strategic Council Representative

2025 College of Fellows Representative

2025 Council of Architectural Component Executives Liaison

Sarah Woynicz, AIA

Kiara Gilmore, AIA

Jason Takeuchi, AIA

Tanya Kataria, AIA

Nicole Becker, AIA

Seth Duke, AIA

Arlenne Gil, AIA

Carrie Parker, AIA

Patty Boyle, AIA

Bill Hercules, FAIA

Jillian Tipton, AIA AIA Staff Liaison

2025

Alabama, Ashley Askew, AIA Alaska, Zane Jones, AIA Arizona, Andrea Hardy, AIA Arkansas, Lauren Miller, AIA California, Magdalini Vraila, AIA Colorado, Kaylyn Kirby, AIA Connecticut, Andrew Gorzkowski, AIA

Delaware, Jack Whalen, AIA

Florida, Bryce Bounds, AIA

Georgia, Laura Sherman, AIA

Hawaii, Krithika Penedo, AIA

Idaho, Katie Bennett, AIA Illinois, Raquel Guzman Geara, AIA Indiana, Matt Jennings, AIA Iowa, Ben Hansen, AIA Kansas, Garric Baker, AIA Kentucky, George Donkor, AIA Louisiana, Calvin Gallion, III, AIA Maine, Sarah Kayser, AIA Maryland, Joe Taylor, AIA Massachusetts, Darguin Fortuna, AIA Michigan, Trent Schmitz, AIA

Minnesota, Constance Chen, AIA Mississippi, Robert Farr, AIA Missouri, Chelsea Davison, AIA

Montana, Elizabeth Zachman, AIA Nebraska, Angel Coleman, AIA

Kathleen McCormick

Nevada, Daniela Moral, AIA

New Hampshire, Courtney Carrier, AIA

New Jersey, Abby Benjamin, AIA

New Mexico, Diana Duran, AIA

New York, Mi Zhang, AIA

North Carolina, Colin McCarville, AIA

North Dakota, Brady Laurin, AIA

Ohio, Alex Oetzel, AIA

Oklahoma, Brian Letzig, AIA

Oregon, Elizabeth Lagarde, AIA

Pennsylvania, Mel Ngami, AIA

Rhode Island, Taylor Hughes, AIA

South Carolina, Ryan Lewis, AIA

South Dakota, Liz Brown, AIA

Tennessee, Sara Page, AIA

Texas, Kyle Kenerley, AIA

Utah, Zahra Hassanipour, AIA

Vermont, Devin Bushey, AIA

Virginia, Erin Agdinaoay, AIA

Washington, Rio Namiki, AIA

West Virginia, Joey Kutz, AIA

Wisconsin, Justin Marquis, AIA

Wyoming, Kendra Shirley, AIA

Washington, D.C., Kumi Wickramanayaka, AIA

Puerto Rico, Reily J. Calderón Rivera, AIA

AIA International, Jason Holland, AIA

Connection is the official quarterly publication of the Young Architects Forum of AIA.

This publication is created through the volunteer efforts of dedicated Young Architect Forum members and made possible through generous grant funding from the College of Fellows.

Copyright 2025 by The American Insititute of Architects. All rights reserved Views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and not those of The American Institute of Architects. Copyright © of individual articles belongs to the author. All images permissions are obtained by or copyright of the author.

05 Voices That Shape Tomorrow: Editor’s Note

Nicole Becker, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C

06 Not By Default but By Design. Chair’s Message: Steering the Future of the Profession

Sarah Woynicz, AIA

07 Nonprofit Charting a Bold Path Forward Immigrant Architects Coalition

10 A Message of Hope to “Ms. Why Not Me?”

Christian Joosse, AIA, NOMA

12 The Impact of Global Trends on Future Practice

Cristian Oncescu, AIA

16 Evolution of AIA Contracts

Garric Baker, AIA

19 Are You a Mouse or a Panda?

Constance Chen, AIA RA and Dantes Ha, AIA, NOMA

22 Finding Home Through Design: Reflections of an Asian Immigrant Architect

Tanya Kataria, AIA

24 You’re Licensed. Now What? Navigating the Next Chapter in Your Architectural Career

Katherine Lashley, AIA and Kumi Wickramanayaka, AIA

26 Creating Learning Environments that Inspire and Engage Students

Julia Eiko Hawkinson FAIA, ALEP, LEED AP BD+C, O+M, WELL AP

29 Charting Your Own Career Path as a Young Architect: Young Architects Forum Webinar Recap

Abigail Benjamin, AIA, NCARB, CNU-A

30 Saying Yes: Even When You Have No Idea What You’re Doing

Brian Baril, AIA, CPHC

32 Project Almost Architect: Equity in Action

Savannah Sinowitz, AIA, NCARB

34 Opportunities for the Next Generation

Sofia Orozco, NOMA, LEED GA

36 The Future(s) of the Profession: How Asking Big Questions Shapes Architectural Practice

Rocky Hanish, AIA

37 Bridge Builders: Mentoring as a Two-Way Street

Devora Schwartz, AIA, NCARB

38 Reimagining Architecture: How Young Architects Can Shape the Future

Dele Oye, MGBCN

40 Navigating the Profession: Where’s Your North Arrow?

Noor Alzuhairi, Assoc. AIA

38 ABC | Archi-TEXT Book Club

“Likeable Badass: How Women Get the Success They Deserve”, A Review

Justin Marquis, AIA, NCARB

Nicole Becker, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C

Constance Chen, AIA RA

40 Connection & Chill AIA YAF Knowledge Focus Group

Nicole Becker, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C Editor in chief

Nicole is an Associate and Project Architect at ZGF Architects in Portland, Oregon specializing in Healthcare. She is the 2025 Communications Director of the AIA Young Architects Forum.

Bryce W. Bounds, AIA, NCARB, CGC Senior editor

Bryce is a Miami native, a Construction Project Management Supervisor in the Public Works department of Broward County, and Florida’s YAR. He attended Design and Architecture Senior High School (DASH) in Miami-Dade and graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with bachelors in both Architecture and Fine Art.

Constance Chen, AIA, NCARB Senior editor

Constance is a Minnesota native and a principal at Locus Architecture in Minneapolis. A University of Notre Dame graduate, her design approach intends to make meaningful connections between people and spaces. She serves as Minnesota’s YAR.

Andrew Gorzkowski, AIA, NCARB Senior editor

Andrew is a Senior Associate at Pickard Chilton in New Haven, Connecticut, where he works in design and project management roles on a variety of large-scale commercial projects. Passionate about advocating for a sustainable future for the profession, he serves as the Connecticut YAR and co-chair’s his local AIA Committee on the Environment. He received his degree at Cornell University, where he was a Meinig Family Cornell National Scholar.

Andrea E. Hardy, AIA, EDAC, NOMA, NCARB Senior editor

Andrea is a Senior Architect at Shepley Bulfinch, where she supports healthcare projects out of their Phoenix Office as a Project Manager. She is Arizona’s YAR, and is passionate about community involvement whether through work, AIA, or locally in the City of Phoenix. She has degrees from Wentworth Institute of Technology and ASU.

Kyle Kenerley, AIA Senior editor

Kyle is an Associate at Modus Architecture based in Dallas, Texas where he works on healthcare and workplace projects as the project manager and technical design lead. He is currently the YAR for Texas where he also serves on the board for the Texas Society of Architects. Kyle’s service with his local and state AIA chapter has primarily been focused on mentoring young architects and education outreach.

Justin Marquis, AIA, NCARB Senior editor

Justin is a Project Architect with Somerville Architects & Engineers in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Managing projects through all phases of development from conceptual design to construction administration, he currently supports the healthcare and educational studios at Somerville. He has a degree from the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee and lives in the Fox Valley area with his family. Justin is the Wisconsin Young Architect Representative..

Garric Baker, AIA, NCARB Senior graphic designer

Baker is a graduate of the College of Architecture, Planning & Design at Kansas State University and excels in leadership positions with state and regional Chambers of Commerce, Young Professionals, the Kansas Barn Alliance, local and state Wide AIA Kansas Board of Directors, and Regional Economic Development activites.

Katie Bennett, AIA, NCARB Senior graphic designer

Katie is a project manager at Babcock Design in Salt Lake City, Utah and Boise, Idaho, and oversees projects during their inception phase through schematic design. She is the current YAR for the state of Idaho and is passionate about housing and sustainable design.

Calvin Gallion, III, AIA, NOMA, NCARB, LEED GA Senior graphic designer

Calvin is an architect and principal at studio^RISE in New Orleans. A Tulane graduate and Natchitoches native, he is a passionate advocate for community and rehabilitation projects. He serves as EDI Chair for AIA New Orleans and as Louisiana’s YAR.

Kendra Shirley, AIA, NCARB Senior graphic designer

Kendra is a project architect at Arete Design Group in Wyoming and Colorado and is Wyoming’s YAR. As a graduate from one of the top undergraduate architecture programs in the country, Kendra’s training and experience provides her with a unique and innovative perspective for creating extraordinary experiences and designs.

The future of architecture is being shaped right now, in studios, site visits, policy discussions, and design critiques. In this issue, we explore what it means for young architects to take the wheel; to lead with intention, question the status quo, and reimagine the profession we’re inheriting and evolving.

This quarter is filled with stories that reflect how the profession is shifting and how young architects are not just responding to change, but driving it. We highlight bold initiatives like Project Almost Architect, a movement tackling licensure equity, and a roadmap for You’re Licensed Now What, which reframes crafting your next chapter on your own terms and expanding architecture’s reach.

You’ll hear from first-generation and immigrant designers sharing how identity shapes design, as well as from the Immigrant Architect Coalition, whose interviews illuminate the layered experience of building a career across borders. We revisit the Charting Your Own Career Path as a Young Architect webinar which emphasized aligning values, embracing lifelong learning, and leading through curiosity and resilience. Through reflections on the Evolution of AIA Contracts, we examine the ways industry, law, and history have influenced the frameworks that guide our profession.

In this evolving landscape, we recognize that leadership doesn’t come with a title, it comes from a willingness to show up, speak up, and shape systems from within. Whether you’re navigating governance, redefining your relationship to practice, or learning how to say “yes” to new opportunities (or to say “no” for better balance), the profession needs your perspective. These voices remind us that shaping the future means honoring where we come from while daring to imagine where we can go next.

These pieces challenge assumptions about who architecture is for, how it’s practiced, and what it can become. We believe steering the profession forward means bridging generations, uplifting diverse perspectives, and embracing unconventional journeys, because the future is too important to leave on autopilot. Let’s drive it together.

With momentum,

Nicole Becker Editor in chief / Connection

Q4 2025:

Call for submissions on the topic Driving Wellness: Mitigating Burnout, Redefining Wellness.

Our editorial committee welcomes the submission of articles, projects, photography, and other design content. Submitted content is subject to editorial review and selected for publication in e-magazine format based on relevance to the theme of a particular issue.

2025 Editorial Committee:

Call for volunteers, contributing writers, interviewers, and design critics.

Connection’s editorial committee is currently seeking architects interested in building their writing portfolio to work with our editorial team to pursue targeted article topics and interviews that will be shared amongst Connection’s largely circulated e-magazine format. Responsibilities include contributing one or more articles per publication cycle (3–4 per year). If you are interested in contributing to Connection, please contact the editor in chief at: nicolejbecker1@gmail.com.

...how do we navigate into the future, harnessing an energy that is not just for this moment but a shift towards a movement?

Architecture as a profession, and its adjacent design fields, often do not follow linear career arcs. Our careers are woven from pivots and pauses, from leaps forward and quiet recalibrations, from shifts ranging from technology to society. For those who are mid-career, we often find ourselves in the middle of this complexity: close enough to where we’ve come from to remember, yet far enough along to feel the pull of what’s next.

This middle ground can feel like a balancing act. One foot is grounded in experience, the other reaching for new relevance. It can be a space of uncertainty. Yet it is also a powerful vantage point, one where we are uniquely positioned to shape what comes next.

As we have increasingly seen in recent years, and as amplified by the first two Connection publications of this year, we stand at a moment when the pace of change in our profession is not just accelerating—it’s demanding evolution. Technology, sustainability, equity, and shifting needs of our clients and communities are redefining our work, our process, our practice, our profession. If we wait passively for the future to arrive, we will always be catching up. But if we engage it head-on— leading not just from the front, but also from within—we have the opportunity to transform pressure into purpose.

This is not a time for reaction. It is a time for intention. As architects, we are trained to envision what does not yet exist. That skill is not just for buildings—it’s for our profession too.

So how do we navigate into the future, harnessing an energy that is not just for this moment but a shift towards a movement?

By asking hard questions. By embracing the discomfort of change. By realizing that the most impactful contributions often come when curiosity meets uncertainty, and we move forward together anyway.

The Young Architects Forum is committed to creating space for these conversations, to elevating voices that challenge the status quo, and to empowering emerging and mid-career leaders alike to steer the profession into the future—not by default, but by design.

With purpose,

Sarah Woynicz 2025 Chair | Young Architects Forum

Woynicz, AIA

Graciela Carrillo, FAIA

Graciela serves as Senior Manager at Nassau BOCES Facilities Services and oversees capital and operational school projects. She serves on the AIA Board as the 2025–2027 At-Large Director and as VP and Treasurer of the Immigrant Architects Coalition (IAC).

Gloria Kloter, AIA, NCARB, CODIA

Kloter, an author, advocate, and founder of Glow Architects, champions immigrant architects, women and mothers. She serves the AIA Strategic Council, AIA FL, and IAC. She is a recipient of the 2025 AIA Young Architect Award.

Yu-Ngok Lo, FAIA

Lo is the founder of YNL Architects and the President of the IAC. He’s received numerous awards including, the AIA National Young Architects Award, NAHB Young Professional Award, BD+C 40 Under 40 and is a fellow of the American Institute of Building Design. .

Oyuki Sulu, Assoc. AIA

Sulu is a designer II at CBRE in Pittsburgh, is licensed in Mexico and pursuing U.S. licensure and specializes in sustainable and commercial design. A champion of immigrant architects, equity, representation and community impact, she is the IAC Communications Director.

Saakshi Terway, Assoc. AIA

Terway is a Design Professional at Quinn Evans in Washington, DC, contributing to the heritage and living practice areas. A licensed architect in India pursuing U.S. licensure, she is the 2025 Associate Representative on the AIA Strategic Council and the IAC Secretary.

In an era when the architectural profession is being called to reimagine equity, access, and innovation, the Immigrant Architects Coalition (IAC) has emerged as a transformative force, centering the voices, experiences, and leadership of immigrant architects to steer the future of the profession.

What began as a grassroots effort to fill a glaring gap in support for immigrant design professionals has evolved into a nationally recognized platform with a clear mission: to elevate, educate, and engage. Since its founding, IAC has served as a vital resource for those navigating the unique complexities of practicing architecture in the United States-from licensure hurdles to cultural adaptation.

In 2023, IAC reached a major milestone by becoming a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, ushering in a new chapter of institutional stability and strategic growth. With the release of its second publication, Prospering in the U.S.: A Handbook for Immigrant Architects, in 2024 and the launch of key programs, IAC has

taken a major step forward. It is no longer just advocating for inclusion; it is actively building the infrastructure to ensure immigrant architects don’t just belong—they lead!

This article features a candid, roundtable-style dialogue with IAC’s Board of Directors, offering insights into their collective

Below: IAC Handbook Book signing at AIA24

vision, expanding initiatives, and long-term strategy. It also takes a closer look at the origin, purpose, and impact of Prospering in the U.S., IAC’s most recent publication that continues to empower immigrant architects across the country.

Q: Why is it important to center immigrant voices in shaping the future of architecture in the United States?

IAC Board: The future of the profession must reflect the world we live in, diverse, interconnected, and globally informed. Immigrants bring unique problem-solving approaches, cultural fluency, and resilience. When these voices are centered, not sidelined, we create more equitable, creative, and future-ready practices.

Q: What does “steering the future of the profession” mean to IAC?

[steering the future of the profession] means building a profession where inclusion is not just a policy, it is a practice.

IAC Board: It means building a profession where inclusion is not just a policy, it is a practice. Through our programming, resources, and leadership, we are centering the experiences of immigrant architects and creating pathways that were previously unavailable to us. We are designing systems that future architects can thrive in.

Q: What are the most exciting initiatives currently underway at IAC?

IAC Board: We launched our mentorship program in early 2025, matching seasoned professionals with immigrant students and emerging professionals all across the USA. In addition, we have introduced two new platforms to expand our reach and storytelling capabilities: the IAC Quarterly Newsletter,

Above: IAC Handbook Book signing at WLS23 Left: IAC Panel session at NOMA24

which shares organizational updates and resources, and IAC Perspectives, a monthly blog series featuring first-person narratives and reflections from immigrant architects. These initiatives help us build a community, share knowledge, and foster a culture of support that extends beyond one-on-one connections.

Q: How is IAC advocating for immigrant architects beyond individualized support?

IAC Board: We are actively engaged in system-level advocacy. That includes collaborating with NCARB, NAAB, AIA, and architecture firms to highlight licensing barriers and promote more inclusive hiring, retention, and leadership practices. We also host public events, podcasts, and panel discussions to elevate immigrant voices and normalize conversations around immigration within the profession.

Q: How do you ensure that your programs reach architects from diverse cultural, geographic, and language backgrounds?

IAC Board: We approach communication with accessibility in mind. That means using diverse formats and platforms that resonate across different regions and demographics. As a board composed of immigrant professionals ourselves, we understand the nuance and work intentionally to be inclusive in both message and delivery.

Q: One of IAC’s most notable resources is Prospering in the U.S.: A Handbook for Immigrant Architects. What inspired its creation, and who is it for?

IAC Board: The handbook came out of the many repeated questions we were receiving, about licensure, finding jobs, adapting culturally, navigating visas, and more. After the success of City Shapers, which highlighted personal stories, we wanted to create something equally powerful but practical. Prospering in the U.S. is designed for immigrant students, emerging

professionals, and even firm leaders who want to better understand and support their international team members .

Q: What topics does the handbook cover, and how does it differ from other career guides?

IAC Board: It covers a wide range of topics: EESA (Education Evaluation Services for Architects) and NCARB processes, job hunting, resume and interview preparation, communication skills, cultural adaptation, and immigration logistics. What makes it different is that it is rooted in lived experience. It is not just procedural, it is personal. It addresses both the logistical hurdles and the emotional realities immigrant architects face.

Q: How was the content developed, and who contributed to it?

IAC Board: We collaborated with 29 immigrant architects across the country. Each contributor, from emerging professionals to designers to licensed architects, brought their own story and expertise to the table. The result is a resource that reflects a rich diversity of backgrounds, pathways, and strategies. It was a deeply collaborative effort, and that diversity is its greatest strength.

Q: How do you hope firms and institutions will use this handbook?

IAC Board: It is a resource not just for immigrants, but for allies. We envision firms using it as an onboarding tool or part of their DEI strategy, and university advisors sharing it with international students. It provides real insight into the challenges immigrant architects face and offers actionable ways to foster more inclusive practices.

Q: What is your long-term vision for IAC in the next five to ten years?

IAC Board: We envision IAC becoming the hub for immigrant architects in the USA, supporting thousands of individuals, offering localized resources, expanding our scholarship and mentorship reach, and influencing policy at the state and national levels. We want to see immigrant voices not only represented but also leading in firm leadership, academia, and public discourse.

Q: Is there anything else you would like to add?

IAC Board: We want immigrant architects to know they are not alone. This coalition was created by people who have walked that path, faced those same questions, doubts, and barriers. Whether you are just starting out or navigating licensure years later, IAC is here as a community, a resource, and a collective voice. And for allies, we invite you to engage with us to listen, support, and help build a profession that reflects the true diversity of those who shape our built environment.

YL: Anything else you would like to add?

BL and SO: We’d like to thank the AIA College of Fellows for giving us this amazing opportunity!

Excerpt from Letters to Ms. 1000| Words of Wisdom from African American Women Architects, Vol. 1

“[The National Organization of Minority Architects’ (NOMA)] directory currently identifies 632 African American Women Architects who are licensed and practicing in the United States. Upon joining this community of women, I recognized the urgency to advocate for more intentionality in mentoring the next generation. Since 2020, approximately 132 individuals have joined this community of women. If the current trajectory is maintained, Ms. 1000 [the 1000th Black Women Architect] will become licensed around the year 2040.

An unexpected yet powerful realization emerged while developing Letters to Ms. 1000—one that has pushed me to reconsider the future of the profession and reshape my vision for the next generation of architects, including ‘Ms. 1000.’

Every step you take is a wave of change. Envision a future where our brilliance isn’t defined by ‘firsts’ but our lasting strength, skill, and resilience.

Co-Author Jennifer Rittler, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, NCARB, WELL AP

Historically, African Americans have relied on storytelling to pass life lessons from generation to generation. These stories have become a critical part of establishing our identity. Publications elevating this community of women currently practicing are sparse [but] these inspiring letter-writers are among those in our community who believe in a dream coming to fruition. These letters illustrate that we are more than architects. We are Black women who have sculpted ourselves from various walks of life. We can change the narrative and empower our future Ms. Architect for many generations to come with our words of wisdom and encouragement. It is my hope that our future Ms. Architect will read these letters seeing a reflection of themselves.” (Joosse)

“More people have gone to space than there are Black women architects.” This reminder, during the Tangible Remnants podcast interview in April with Nakita Reed [originally quoted by Tiara Hughes, founder of First 500] is when one truly feels the gravity (no pun intended) of how few of us there are. While many may be aware of the shockingly low number of Black women architects in the United States, Letters to Ms. 1000 is a message of hope. It is a part of a greater conversation regarding the pivotal role of mentorship in the profession.

Presently, crucial effort and focus are being placed on the formation of early pathways at the educational level. Although AIA and NOMA have made great strides in diversity efforts through initiatives such as AIA’s K-12, Camp Architecture, and NOMA’s Project Pipeline, research shows us that we are only seeing a part of the equation.

More people have gone to space than there are Black women architects.

Concurrently, we are contending with the reality that data from The American Society for Microbiology (October 2024) demonstrates that women earn 50% of STEM-related bachelor’s degrees in the U.S. However, despite these advances, gender equity in STEM still lags, suggesting a “leaky pipeline” at the professional level. This study also shows direct correlation between effective mentorship programs and improvements in representation of women in STEM fields.1

A powerful thread intertwining each narrative within Letters to Ms. 1000 is that the writers attribute their success to a mentor who came at a critical cross section in their career after they had completed their degree program.

At AIA’s 2025 National Conference in Boston, I joined a conversation on mid-career mentorship during an EDI session co-hosted by NOMA and AIA, centered on the Guidelines for Equitable Practice. There, I had the opportunity to share the book and discuss how AIA’s Next to Lead program is actively building leadership pathways for racially and ethnically diverse women—precisely at this critical mid-career stage. Yet, in reflecting on NOMA’s goals during the EDI session to reach 5000 black architects by 2030, I pondered how Letters to Ms. 1000 could be a tool for mid-career mentorship and a pathway to an untapped pipeline in creating new architects.

I left the session wondering, “How do we get there? What are those barriers that we need to overcome to reach 1000?”

A few of those barriers came into focus when attending a keynote

speaker at a higher institution focused conference, ACUHO-i. The speaker from Georgetown University, Bryan Alexander, author of Academia Next: The Futures of Higher Education, referenced a 10-15% reduction in enrollment due to the value proposition of higher education decreasing in a tumultuous economic climate, as well as, the ongoing role of AI in reduction of certain job types and individuals attaining second careers. Despite these many changes in economy and enrollment, the provided visual outlined that architecture has maintained its enrollment as a profession for the last 10 years.

If enrollment has not changed for a decade despite the demographic shifts in STEM careers then how do we get to 1000 licensed architects? Perhaps, our future Ms. Architects must come from somewhere else.

The answer came in the form of a young woman at the same conference. She explained that she had spent years as a Resident Hall Director although she always wanted to be an architect. For her the book was her sign to complete her application for a second degree and career in New England.

Now I bring the book everywhere.

There are so many others who share her story. To embrace the future of the profession, we have to collectively and intentionally widen our circle; not just to make space for diversity but also for who we envision as the future of the profession. The decline in need for other industries is an opportunity for even more crossdisciplinary architects than ever before. Letters to Ms. 1000’s partnerships are a step towards unconventional outreach to come alongside communities from within; transforming the mindset of mentorship from being “who you needed when you were younger” to being a source of inspiration in a time when we are desperately in need of more innovators to solve universal challenges of the world.

Admittedly, I also initially presumed that ‘Ms. 1000’ may now be a child. But I’ve realized that the message of hope to “Ms. Why Not Me” is that it is never too late to pursue your dream and inspiration can be found anywhere, even on a shelf.

Above: Book Spread at 2025 Conference

A special thank you to the many advocates that have come before this project and are honored in the publication, such as Riding the Vortex, 400 Forward, and First 500. I know this publication will certainly not be the last of its kind and what will happen between now and 2040 remains unknown, but one thing is certain: we cannot journey alone. We need every ally to make a difference.

Pre-order Letters to Ms. 1000 Limited Edition here. All book proceeds go to the Letters to Ms. 1000 Empowerment Fund to empower the next generation of architects by using the publication as a financial resource. #empowering1000

1 Women in STEM: The Importance of Mentorship and community | ASM.org. (n.d.). ASM.org. https://asm.org/articles/2024/ october/women-stem-importance-mentorship-community

Resources

Podcast Episode | Instagram | Website

Hashtag: #empowering1000

In 2024, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) published the Horizons 2034 Report, identifying four significant forces that will drive global change over the next 10 years: the Environmental Challenge, the Economics of the Built Environment, Population Change, and Technological Innovation.1 Each of the four themes was divided into four topics. Subject matter experts undertook horizon scans of the sixteen topics to evaluate the current state of the world and project how each issue will evolve as a driving force over the next decade. Together, they painted a picture of the complex challenges facing the global architectural profession: designing a resilient and just built environment for a growing and aging population amid a climate emergency. The research, analysis, and observations in this article are part of a report commissioned by RIBA to connect the Horizons 2034 Report to the ongoing Future Business of Architecture program, a research effort aiming to help firms recognize long-term business opportunities and challenges.2 The report “The Impact of Global Trends on Tomorrow’s Practice: The Horizons 2034/ Future Business of Architecture Review,” is published on the RIBA website in full, and this content and the following future scenarios have been excerpted and edited for brevity and clarity.

Horizon scans and strategic plans undertaken by organizations like the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and RIBA offer moments of reflection to help us prepare for the future. Within the context of the aforementioned RIBA programs and their 10-year outlooks, the research report focuses on two basic

questions:

• How do the four grand themes steer the future of the architectural profession?

• How can architects shape or adapt to these forces over the next decade?

This report responds to the first question by painting two possible global futures, based on an analysis of the four Horizons 2034 themes and their projections, the data they are based on, t and new independent research. These possible paths are excerpted in the next section. The second question warrants a more expansive yet detailed answer and is explored in the full RIBA report. For the purposes of this discussion, the themes can be summarized in the following way:

• The Environmental Challenge underscores the need for architects and built environment professionals to prioritize carbon mitigation, climate adaptation, and biodiversity protection in building and urban design.

• The Economics of the Built Environment reveal how global finance and market forces accelerate urbanization. Architects must understand the commoditization of real estate as financial assets and the implications of urban density in order to create sustainable, just, and egalitarian solutions for cities in developed and emerging economies.

• Population Change, encompassing the growth, contraction, and migration of people, constantly reshapes communities globally. Architects and design professionals must address the varying effects of aging populations, international migration, and ethnic diversification at multiple scales.

• Technological Innovation highlights the ways in which the global architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry can adopt new design and construction methods driven by leveraging data, increasingly sophisticated tools and workflows powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), and the automation and industrialization of construction.

The authors of the Horizons 2034 Report make a plethora of evidence-based projections across their essays, but the relationships between them vary. Some reinforce one another to effect greater change while others create tensions or are mutually exclusive. Further analysis was undertaken, qualified through new data, research, and global developments through the first half of 2025.

While the future is always hard to predict, we can build up evidence-based, interpretive, and somewhat speculative scenarios to serve as guideposts for the future. These can help architects in identifying signs of progress (or lack thereof). The aspirational Ideal Scenario and grounded Pragmatic Scenario lay out the opportunities and challenges facing the AEC industry to help make better decisions on the road to 2035.

• The Ideal Scenario materializes over the next decade if many things go right in the world, without relying on any silver bullet solutions. Great opportunities lie ahead, but the pathway to success is narrow given the competing challenges in the Global North and South.

• The Pragmatic Scenario is a plausible trajectory if less rosy current reports, computer model projections, and regulatory and practical challenges come to pass.

The year is 2035. Globalization has reached new highs as increased trade, capital, information, and people flows across borders. The value of global construction work has grown by 40% over the preceding 10 years, with China, the US, and India responsible for half of all work.3 Sub-Saharan Africa and emerging Asia compete for the title of ‘fastest growing global construction market.’ In western Europe, the UK is the fastest growing construction market.4

In the Global North, projects at all scales have benefitted from energy-performance-based design approaches, low-carbon energy technologies, and increased circularity for carbon mitigation. New low-carbon materials have come to market, though many projects continue to utilize high-carbon steel and concrete.

New national legislation has stimulated more adaptive reuse and renovation of existing building stocks, particularly housing. Urban environments have benefitted from less demolition and less new construction, resulting in healthier homes, greater biodiversity, and mixed-income neighborhoods with access to better infrastructure and transport.

Financialization is still the primary force shaping cities, but new public policies in many countries and international investor pressure have incentivized different behaviors. The prerequisite for developers sourcing real estate investment in 2035 is actionable progress on complete decarbonization of portfolio assets.

In 2035, Africa’s population has increased by 400 million people to 1.8 billion, as predicted, and the increased urbanization has turned sub-Saharan Africa into one of the fastest growing

markets.5 Delivering sustainable urbanization at a rapid pace is an ongoing project, enabled by a large, local, working-age population, imported professional expertise, and affordable solar technology and battery storage.

Architects from the Global North are collaborating with Global South professionals to work for local clients on developing sustainable projects that improve resilience, reduce poverty, and respond directly to the needs of local communities. Firms are taking on advisory services with governments to create modern building and energy codes and pass better built environment policies. Architects, engineers, and professional organizations are partnering with universities to educate new design professionals and upskill local labor forces.

Cutting-edge technology, powered by the AI revolution, is accelerating design and construction productivity in the Global North, and its use has become part of the professional standard of care. Years ago, large AEC software companies began pooling resources and drawing on new cross-industry data trusts, resulting in greater information-sharing and collaboration across the industry.6

Multimodal AEC AI/ML tools are trained on large amounts of curated AEC data, with functionality for end-users to incorporate firm-specific data. The design process is informed at every step by AI tools and AI agents that can compare a firm’s current design metrics with performance data from similar building projects, check code and program and automate cost estimating and supply chain analysis. Architects work more closely with builders within a combined data-driven ecosystem of building (and building component) performance.

To meet the construction demand anticipated for 2035 and beyond, the global construction industry has adopted new technologies and practices to increase productivity by 1% annually. Migration of skilled workers from the Global South has narrowed the skilled labor gap in the Global North. In the most developed nations, rather than focusing on innovations that only increase control of process and risk, the construction industry has adopted technology to improve workforce productivity

at scale, such as industrialized prefabrication, supply chain marketplaces, and AI tools.7

Over the previous 10 years, global policymakers continued to incentivize renewable energy development and adoption in line with 2025 projections. As a result, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions peaked in the mid-2020s, then started a consistent decline as renewables overtook fossil fuels.8 However, the rapid population and economic growth in the Global South and a tenfold increase in global demand for data centers have meant that reductions are not even close to net-zero targets and a global temperature rise of 2.6°C by 2100 is anticipated. 9

The passage of new legislation incentivizing adaptive reuse has been slow across the Global North, and, where passed, building owners continue to seek exemptions from compliance. There has been a modest increase in the number of adaptive reuse and renovation/retrofit projects to improve energy efficiency and reduce GHG emissions, but city neighborhoods face other challenges. Newly constructed housing neighborhoods attract wealthy homeowners while displacing local communities, driven by real estate financialization and accompanying gentrification.

In developed countries, energy performance-based design approaches and low-carbon energy technologies are only implemented in well-funded projects, as policymakers offer little or no new financial support to bring hydrogen, carbon capture, and clean fuels to the mass market.10 Most construction projects are still built using steel and concrete, and minimal progress has been made towards decarbonizing the production process by 2050.11

Africa’s population has reached 1.8 billion, and the increased urbanization has turned sub-Saharan Africa into one of the fastest growing markets. India has over 1.6 billion people and is the third largest construction market.12,13

While the working-age population in India14 and in African countries such as Kenya and Nigeria continues to grow, economic growth is limited due to low labor force participation and reduced access to education. The plentiful young labor force has not left to fill the skilled worker gap of the Global North construction industry.

AEC software companies have invested in developing AI/ ML tools, but AEC industry-wide information-sharing and collaboration through data trusts has not come to pass. The preceding decade saw the peak and bust of the AI hype cycle, followed by an assessment of which AI firms have produced fitfor-purpose tools.15 The resulting AEC AI tools are not holistic building simulation and analysis co-pilots, but have a deep, narrow focus and excel at discrete, automatable tasks.

The construction site of 2035 is in many ways like that of 2025, but more digitized. Sensors, scanners, and robots are integrated into day-to-day operations, tracking and moving building components into place, some of which are prefabricated offsite. Despite some AI tools being widely adopted, the global construction industry has not seen meaningful productivity growth, and, coupled with skilled labor shortages, construction supply in the developed world falls short of high demand by trillions of dollars.

The purpose of forecasting programs is to provoke thoughtful discussion rather than lay out certainties, ultimately providing a long-term view that allows architecture firms to make informed decisions about their practice, work, and staffing. Each scenario comes with significant implications for the practice composition and skills, business models, clients, and markets that will affect US and global architecture firms. (These are explored in greater detail in the full RIBA report.)

In both scenarios, significantly increased construction demand due to global population growth is expected, as is aging and ethnic diversification in the world. The differences between the scenarios arise from our ability to meet the moment and respond to multiple demands at the same time in the coming decade and beyond. The adaptation and innovation of the AEC industry over the next decade will be driven by individual firms’ analyses and approaches as they respond to the global forces already in motion. Today, careful thought and strategic planning will help the architectural profession play an active role in shaping a more ideal future.

Footnotes:

1. Royal Institute of British Architects, Horizons 2034 Report, London, Royal Institute of British Architects, 2024.

2. Royal Institute of British Architects, Future Business of Architecture, London, Royal Institute of British Architects, 2025.

3. N. Fearnley, R. Graham, and J. Leonard, Global Construction Futures: A Global Forecast for the Construction Industry to 2037, London, Oxford Economics Limited, 16 March 2023, p. 12.

4. Fearnley et al., Global Construction Futures, p. 23.

5. World Green Building Council and Africa Regional Network, Africa Manifesto for Sustainable Cities and The Built Environment, London, World Green Building Council, 2022, p. 7.

6. P. Bernstein, Machine Learning: Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, London, RIBA Publishing, 2022, pp. 130–135.

7. J. Mischke et al., Delivering on Construction Productivity is No Longer Optional, New York, McKinsey & Company, August 2024, pp. 9–11.

8. D. Hostert, BloombergNEF New Energy Outlook 2025 Executive Summary, New York, Bloomberg Finance LP, 15 April 2025, p. 7.

9. Ibid., p. 8.

10. Hostert, New Energy Outlook, p. 4.

11. Ibid., p. 5.

12. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects 2024: India Total Population, 2024.

13. Fearnley et al., Global Construction Futures, p. 21.

14. N. Fearnley, Key Global Construction Themes 2025, London, Oxford Economics Limited, 9 January 2025, p. 3.

15. A. Jaffri, ‘Explore beyond GenAI on the 2024 Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence’, Gartner, 11 November 2024.

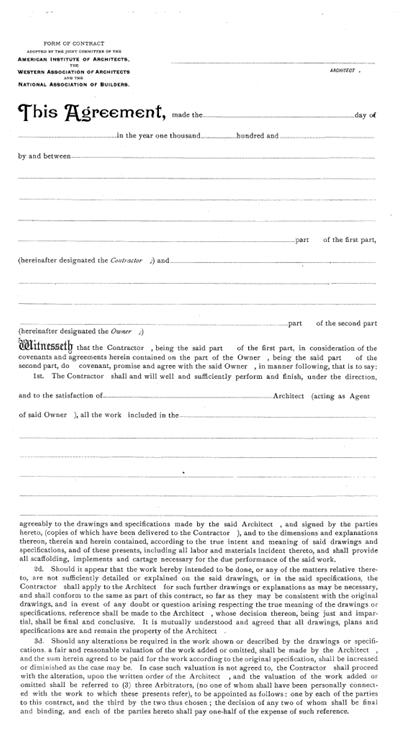

Laying the Foundation: Origins of the Documents

The field of architecture is a continually evolving one. From the outset of an established association of architects in 1857 originally called the New York Society of Architects by its thirteen original founders, to its subsequent renaming as the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Within ten to fifteen years later, chapters were being established all over the country, and today, the AIA has over 200 chapters worldwide.

By the 1880s, these various chapters began investigating the establishment of a standard contract to engage an architect and construct a project. This led to the formation of the Committee on the Uniform Contract of 1887. Together, the three member committees drafted and published the first AIA agreement, the Uniform Contract, the following year in 1888. As the Uniform Contract was utilized by more and more chapters, deficiencies within the documents became evident. This led to the first revision of the Contract in 1893, only five years after the initial publication. It took another nine years for the next revision in 1902.

As these documents began setting the framework for how projects were governed, the Committee garnered input and feedback from organizations such as the National Association of Builders, contractors, legal counsel, and many others who

advocated for different parties involved in the projects. In 1900, the committee renamed itself to the Committee on Contract and Lien Laws, and on the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of the original Committee, a revised Uniform Contract was published in 1907 incorporating this feedback. Over the next four years, the Uniform Contract expanded the suite of governing documents. In 1911, the Standard Documents of the AIA were released. Furthermore, this evolution led to the Second Edition of AIA Documents in 1915 which established the first actual conditions of construction.

By 1918, the entire suite of documents had again been revised and republished. This coincided with the end of World War I, when the United States started to bring soldiers home that needed jobs and housing, to begin living more urban lives. Shortly thereafter, the documents were republished with more revisions in 1925. By the thirtieth anniversary of the original agreement, it had been updated and revised eight times, with a new document being released, on average, every four years. Then, the Great Depression began in 1929. The economic downturn slowed rates of construction and the need for revisions of the documents. By the time the world started to recover from the recession, only one more revision was published which coincided with the influx of Works Progress

Administration (WPA) projects being implemented. This new growth was short lived and derailed by the coming decade.

World War II devastated the world and halted overall progress of the development of world economies. As the war came to a close the number of soldiers coming home seeking urban and eventually suburban lifestyles accelerated immensely. This increase in economic development sped up the number of revisions to the documents with new releases in 1937, 1951, and 1958. In this context, it can be noted that world events are catalysts for positive and negative changes in the construction industry. Reverberations of World War II had incalculable impacts on the construction world. As a result of the war and needing to move resources great distances at a rapid pace, the interstate highway system was established in 1956.

In this context, it can be noted that world events are catalysts for positive and negative changes in the construction industry.

Architecture is very much a knowledge-based industry whereas the contracts were commodities of the paper-era. In 2020, AIA recognized the need to shift back toward the knowledge-based industry model and sold the majority of ACD (AIA Contract Documents) to True Wind Capital steering ACD back to a service (in the tech community, it would be considered SaaS –Software as a Service). This initial partnership proved strategic – True Wind Capital has the means and resources to develop and revise the contracts, in digital format, rapidly and keep the documents accessible. AIA can then focus on other aspects of the mission while retaining the revenue generating stream from its minority shareholder position. This places AIA in a position to earn more through SaaS rather than attempting to sell phasedout paper documents.

Because of this, the nationwide network of movement fueled the ability of people to relocate to urban areas, displaced over a million residents, connected product to project pipelines, and further facilitated rapid development of new products. The impact of this resulted in four more revisions to the documents over the next ten years. Twenty years after the enactment of the interstate highway system, the population grew and the economy was expanding, leading the complexity of projects to grow exponentially. The American Institute of Architects acknowledged this by recruiting more members to sit on the documents committee, expanding from around five members to twelve. Since then, the committee has nearly tripled and the number and types of documents have grown in tandem.

After the turmoil of the first ninety years of documents being in existence, the documents had gone through a minimum of 16 revisions. To overcome the uncertainty of economic and world factors, and maintain continual updating, in 1976, AIA established the ten-year cycle of revisions. Thus, in today’s documents, we note the 1997, 2007, 2017, and similar editions. The 2027 release of documents will mark 140 years since the establishment of the original committee. Over the 140 years, the committee has grown from three to nearly thirty, while the document suite has grown from a single document to over 250.

Since the 1960s, the introduction of computers into the world of architecture has created rapid change, especially in terms of software development. Just as the tools of trade, equipment, and materials have all changed within the construction industry, the same can be said for architecture. For more than a century, AIA raised capital through the sale of paper documents, however, with the need for physical, paper copies decreased once the digital world was established.

For AIA to create an online, digital platform for contracts, one could view it as a tech start-up without the tech resources. In July 2025, private equity firm Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe (WCAS) ACD Operations, LLC announced it had acquired a majority stake in ACD. As a result, True Wind Capital is a minority shareholder, but AIA a partner to both WCAS and True Wind Capital when it comes to advising its industry.

Much like with historic preservation projects, the foundations were long ago placed, and then along the way, restructuring has been undertaken, and now, the systems have been updated for the next century. Here’s how it works: WCAS as the majority shareholder, and True Wind Capital, a minority shareholder, in partnership with AIA, ensure that AIA’s long-established Documents Committee and the ACD Content Team work together to cover all areas of the design-built industry along with insurance and construction law. For this section, Josh Flowers, FAIA, 2025-26 AIA Secretary and former Young Architect’s Forum Chair was interviewed for insight into what this process looks like. He has extensive experience not only in architecture, but specifically construction law and contracts. He serves as the in-house counsel for Gresham Smith – a multi-specialty firm that designs everything from roads to corporate campuses.

Every year, the call for volunteers goes out and at this time, interested parties can apply to the ACD committee. ACD and the selection committee then interview the potential candidates who will eventually serve a ten-year term. A limited number of seats become available annually, so potential candidates are kept in mind for whenever a position opens. Each sector, design, construction, insurance, legal counsel, among others is represented, and the selection committee attempts to cover all geographic locations in addition to representatives from varying size firms and practice areas. This ensures a representation of the entire country, a sampling of the design-built environment, as well as representation from every level of firm size.

Once on the committee, individuals are divided into task groups that take on a different suite of documents. They work with their industry partners to gain different areas of expertise, insights

into issues or ideas, and potential revisions or adjustments that need to be made to a specific set of documents. There is even a process that can be undertaken to establish an all-new document tailored to a new need.

The committee works closely with the management and staff of ACD, which remains constant in the entire process. WCAS, as the majority shareholder, and True Wind Capital, a minority shareholder, partner with AIA whose expertise makes the collaboration so valuable to all parties. Each division or suite of documents is revised every ten years and each section is staggered so that the entire 250+ documents aren’t released simultaneously.

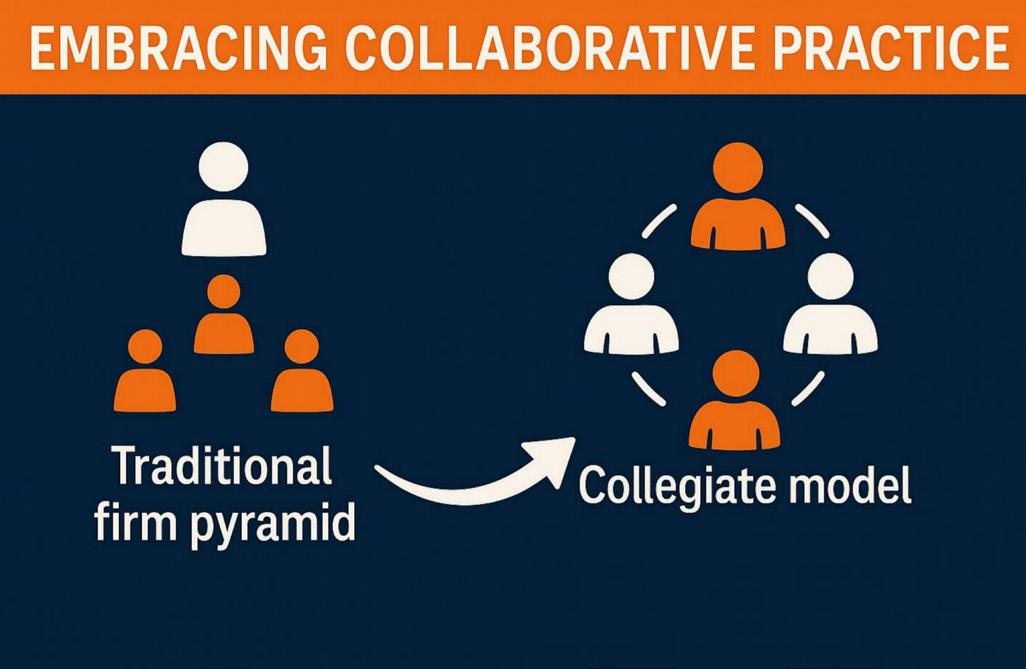

When asking Josh about trends that he sees in the coming years, he noted the preference for collaborative project delivery options is driving the need for further diversified options to meet the needs of future project teams. This sense of shifting preferences is only one aspect of how the committee goes about selecting areas of the documents to remain relevant, balanced, and responsive to the needs of the AIA membership and the industry as a whole.

... he noted the preference for collaborative project delivery options is driving the need for further diversified options to meet the needs of future project teams.

The AIA has long worked with the Associated General Contractors of America through a joint AIA-AGC Committee to help bridge the design and construction communities. The current focus of the committee is on developing best practices to improve collaboration between architects and contractors. Brian Baril, AIA, CPHC, Director of Preconstruction for A/Z Corporation and a former Young Architect Representative, brings over two decades of design and construction experience to the group. He emphasizes that while contracts are essential for managing risk and ensuring fairness, the most successful projects are built on a foundation of trust, open communication, and shared goals. “The contract should be there as a backstop,” Baril explains. “But the real work happens through collaboration. Our committee’s efforts are about strengthening that day-today partnership—building tools that support a more aligned, integrated team dynamic.”

In its first half-century, AIA established itself as a collaborative partner in providing balanced, legal representation documents which began driving not only the country, but the global construction industry. The following half-century found AIA refining these documents to an all-encompassing suite that was responsive to a quickly changing world. Going into the third half-century, AIA has focused ACD on becoming even more responsive to a digital world by leaning on its roots of being a collaborative partner. Acknowledging that AIA is a membership-

Josh Flowers, AIA

AIA Secretary, former Young Architect’s Forum. He serves as the inhouse counsel for Gresham Smith – a multispecialty firm that designs everything from roads to corporate campuses.

Brian Baril, AIA, CPHC Director of Preconstruction, Accidental Construction Guy, Still Technically an Architect

based organization, resources were redirected to support members rather than toward digitization of the documents. Bringing in WCAS and True Wind Capital has allowed AIA to continue delivering on the core mission of providing value to its members. Moving forward, ACD is now positioned to be agile and flexible, while retaining the steadfast knowledge built on over a century of experience, collaboration, and practice.

How do you see the profession and contracts changing in the coming years? What trends have you noticed that could potentially be benefited by updates to the documents?

About the Author

Garric Baker, AIA (Kansas’ Young Architect Forum Representative) is majority shareholder in Baker McMillan Architects, a Kansas-based architectural firm. He also leads Construction Evaluation workshops through Black Spectacles, an online learning platform for licensure candidates. The CE division focuses largely on AIA contract documents and how they are used throughout the life cycle of a project. His other writings include the Young Professional’s Handbook collection that covers everything from the young professional entering the workforce through becoming a manager.

Sources:

The History of AIA Contract Documents

AIA Documents Committee

WCAS Announcement

Brian Baril, interview.

Josh Flowers, FAIA interview.

Baker McMillan Architects; Kansas YAF Representative

A jack of all trades is a master of none, though oftentimes better than a master of one. – William Shakespeare

Becoming an architect is no small feat! In most jurisdictions, it requires four to seven years of college, followed by 3,740 hours of documented experience, and six licensing exams. Some jurisdictions even have supplemental requirements (Alaska, California, and Florida, etc.). According to recent NCARB data, the average path to licensure now takes 12.5 years. That’s a long road, especially since it’s only then you can finally call yourself an “Architect”.

If you graduated in the 1990s, your path to licensure likely looked very different. At that time, you could sit for all your exams in a single four-day window. If the timing aligned, you could become licensed just months after graduation.

You were trained to be a mouse. And we say that with admiration, not criticism.

The mouse thrives in a world in flux—where the food sources are scarce and environmental pressures are mounting. Agile and adaptable, it can survive on anything from steak and chocolate to junk and litter. It’s not picky, it’s resilient. And that resilience was built into your training.

So what changed? Have buildings become so radically complex that it now takes nearly twice as long to prepare architects for the profession? Or are we using space-age materials and antigravitics that require more time and attention?

The buildings haven’t changed as much as our process. Here’s what we mean.

In the early ’90s, most architects still drew by hand. Project teams were relatively unified because everyone drafted. Drawing was the shared language of the office and the cornerstone of project delivery.

Then came technology… And with it, “The Fracturing”. Firms that couldn’t adapt were gradually pushed to the margins. Fastforward a few decades, and many offices now host an eclectic mix: hand-drafters, CAD veterans, Revit-ers, SketchUp-ers, Enscape wizards, Photoshopers, and spreadsheet gurus all working in parallel, often speaking different technical languages. What once felt like a studio now resembles a production floor, divided by tools and tasks.

Issue No. 17: 2019 Quarter 3

Like the Tower of Babel, our shared [drawing] language splintered. The profession began to drift apart into isolated islands of specialization. As technology evolved across generations, larger firms started encouraging new grads to find their niche–to pick a lane and be productive. But for those still figuring out what excites them, that kind of early specialization can feel more like a trap than a launchpad.

Smaller firms face their own challenges. They often need someone who can manage a project from start to finish, but without the luxury of years of in-house training. It’s a tough spot–one that leaves both ends of the spectrum struggling to balance expertise with flexibility.

Is this necessarily a bad thing? Not when business is booming. But as AI looms, promising speed, efficiency, and automation, we have to ask: what happens to those hyper-specialized roles if the environment shifts?

Enter the panda. Once on the brink of extinction, pandas have become the poster animal for conservation. The opposite of the mouse, they can eat one thing and one thing only, Fargesia rufa, a woody bamboo native to western China. They are helpless in the wild and seem to lack basic survival instincts. (See hilarious Youtube video of panda moms trading their cubs for snacks.) They survive only in artificial environments.

Architectural specialists risk a similar fate. Deep expertise is valuable until the environment no longer needs that particular skill set.

However, like a clever, omnivorous rodent, the generalist thrives in uncertainty. They adapt. They survive. In a profession constantly reshaped by new tools and processes, versatility is essential.

Of course, becoming a generalist takes longer. Architecture is a broad field, and projects are long and complex. Gaining fluency across design, codes, budgets, and coordination doesn’t happen overnight. These skills are gained through learned experience and can’t be “hacked” to learn quickly. But architecture has historically been a generalist’s game. Think about it: client meetings, budget talks, coordination calls—these aren’t niche skills. They require context, perspective, and the ability to zoom in and out. Architects don’t just make drawings. They connect the dots.

In the end, generalists may not be the flashiest. But like those small mammals that survived the asteroid, they’re built for change. And in a profession that’s rapidly evolving, adaptability might just be the most valuable skill of all.

So, if you must specialize, specialize in being a generalist.

This May, I had the honor of participating in a panel hosted by the University of Washington’s National Organization of Minority Architecture Students (NOMAS) chapter for Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AANHPI) Heritage Month. Titled “A New Chapter: Home, Origins, Resilience (ANC:HOR),” the panel invited Asian American architects to reflect on the meaning of home, their lived experiences, and how those themes shape our work in the built environment. As an Asian immigrant architect, the topic felt deeply personal. It gave me an opportunity to pause and look inward—how migration has shaped my identity, what gives me fulfilment, and the legacy I hope to build.

Above: Panel discussion, “A New Chapter: Home, Origins, Resilience (ANC:HOR),”by NOMAS & AANHPI.

For me, the idea of home is layered. Delhi is the home I inherited. Seattle is the home I am building. One does not replace the other; rather, they compound.

I was born and raised in Delhi. It’s where my roots are—where my family lives, the place of my childhood, where the smells and sounds are familiar, and where I instinctively understand how the culture and life works. It’s my place of comfort, memory, and belonging.

Seattle, by contrast, began as unfamiliar. I arrived here with no family, but slowly, through friendships, conversations, small rituals, and meaningful work—I found my community. Over time, the relationships I’ve built, the life my husband and I

share with our dog, and the buildings I’ve helped design, have woven themselves into my own evolving narrative of home. In designing spaces here, I’ve not only made my mark on the city, I’ve discovered new parts of myself: what brings me joy, what fuels my work, and what gives me purpose.

In designing spaces here, I’ve not only made my mark on the city, I’ve discovered new parts of myself: what brings me joy, what fuels my work, and what gives me purpose.

A formative moment in my migration journey came during the pandemic. With life slowing down, I suddenly had extra time, and the first thing I wanted to do was to get licensed. That milestone was something I had longed for, but once it was checked off, I found myself asking: What now?

For the first time, I wasn’t just in survival mode as an immigrant. I had the power to take my career by the reins and shift into thriving mode. I started soul-searching and reflecting on what truly drives me. I enrolled in AIA’s Next to Lead programleadership training designed for diverse women and volunteered in my city’s Housing Commission as a citizen architect. Through that experience, I discovered a new side of myself - one that was passionate about leading and serving others.

This new sense of direction fuelled my involvement with AIA Washington Council, then the Young Architects Forum as Washington state’s Young Architect Representative and eventually YAF’s Advocacy Director. That journey from survival to agency wasn’t linear, but it was transformative, and it continues to shape how I show up in the profession.

I recently heard Karen Braitmayer, FAIA, of Studio Pacifica say: “The best architecture happens when the people designing the spaces actually reflect the diversity of the people using them.” That resonated deeply with me. When our teams reflect the communities we serve, the spaces we create become more authentic, more inclusive and more meaningful.

One of the most meaningful projects I’ve worked on in my career was an affordable housing building for formerly homeless AANHPI seniors in Tacoma, Washington. From the beginning, the design was centered on wellness, dignity, and the embodying the feeling of home for residents who may not have had one in a long time.

I drew inspiration from lanterns– a recurring symbol in many Asian cultures that represents celebration, warmth, and new beginnings. Those were the exact emotions we wanted to evoke in the building. In designing the building, I often asked myself, “What would my grandmother want if she lived here?”

I imagined her sipping tea on a bench in the courtyard, enjoying an evening stroll while chatting with neighbors, or reading by the window in her sunlit apartment. That vision and cultural memory helped guide my design direction. I incorporated large windows for amply daylit apartments, created inviting communal areas, and added intimate nooks for quiet reflection. Walking paths, seating surrounded by lush plantings, and a community garden were all shaped by a desire to support wellness, connection, and joy.

A majority of my career has been spent working on affordable housing projects in Seattle. Once these projects are complete, I frequently hear deeply moving stories from the leasing team of new tenants brought to tears as they receive their keys, overwhelmed with relief and gratitude at finally having a place to call home. For many, it’s more than just a roof over their heads, it marks the beginning of a new chapter and a renewed sense of hope.

Knowing that I played a role, however small, in creating a space that feels beautiful, safe, and welcoming, fills me with a profound

sense of purpose. This is my anchor, the reason I do what I do. In helping others find home, I continue to build my own, right here in Seattle.

Speaking on the ANC:HOR panel was not only a chance to reflect on my own journey, but also an opportunity to connect with students and the next generation of architects. The students in the audience asked thoughtful, courageous questions about urgent challenges faced by AANHPI populations in Seattle, design spaces for intergenerational living, and creating successful project teams. It was deeply fulfilling to offer guidance, share lessons I’ve learned, and see the spark of leadership and vision in their eyes. To be part of a conversation that both honored our collective heritage and inspired future paths felt incredibly meaningful.

The best architecture happens when the people designing the spaces actually reflect the diversity of the people using them.

Licensure is a milestone worth celebrating. After years of study groups, AXP hours, exams, and juggling project deadlines, you’ve earned your title: Architect. But once the confetti settles, many young architects find themselves asking: Now what?

It’s a question the Young Architects Forum (YAF) hears often and one we’re here to help answer. Licensure isn’t the finish line, Instead,it’s the starting point of a career you get to shape intentionally. Whether you want to deepen your expertise, expand your network, advocate for the profession, or pivot into a new focus area, there is a path for you.

Here’s a roadmap to help you navigate your next chapter:

Post-licensure, many architects find purpose in sharpening their skills and exploring new focus areas—but growth doesn’t always require a big leap. Some of the most meaningful development can happen within your current role.

Networking isn’t only about finding your next job; it’s about finding mentors, collaborators, and peers who will inspire and support you.

Architects play a critical role in shaping communities, and postlicensure is a chance to step into leadership and service. Serving the profession and your community doesn’t just help others, it strengthens the relevance of architects in society. By showing up, sharing your expertise, and participating in your community, you help people see the value of design thinking in addressing everyday challenges, building trust in the profession, and ensuring architects have a voice in shaping the future.

Service enhances your leadership skills, broadens your perspective, and strengthens the architectural profession for the future, while reminding your community that architects are essential contributors to a more equitable and resilient built environment.

“Expertise isn’t built overnight; it’s the result of curiosity, initiative, and a willingness to keep learning.”

Whether it’s earning certifications like LEED or WELL, learning new tools, pursuing a niche like housing, sustainability, or adaptive reuse, or stepping into project leadership, this is the time to shape your expertise with intention. Reflect on what excites you and align your growth with your long-term goals.

Expertise isn’t built overnight; it’s the result of curiosity, initiative, and a willingness to keep learning.

Your community will shape your career just as much as your projects will. Post-licensure is a prime time to find your people, those who will cheer you on, challenge your thinking, and remind you why you chose this profession in the first place.

Architecture often can feel isolating, and it’s easy to get lost in project demands or firm pressures. Finding your community helps counter burnout by providing spaces to share challenges, celebrate wins, and gain perspective outside your day-to-day. It’s a way to be reminded that you’re not alone in your journey.

You’ve achieved licensure, don’t stop there. Advocating for yourself and the profession is part of your journey, and sharing your work and knowledge can inspire others like you to step up and lead change within their own careers.

Promoting your work isn’t about self-importance. It’s about ensuring architecture’s impact is visible and valued, and showing emerging professionals they too can step forward to shape the future of the built environment. Sharing your process, lessons learned, and successes can empower others to do the same. Mentoring someone through such a process helps ensure that the profession continues to grow with diverse, and passionate leaders.

Licensure can also be a launchpad to explore adjacent paths. Your license gives you a foundation of credibility and expertise that translates into many impactful careers. Whether it’s development, policy, academia, sustainability consulting, tech, or design leadership in a different industry, your architectural training gives you a unique advantage.

Expand Your Network

The right community will fuel your career and remind you you’re not in it alone.

Celebrate Your Work and Others

Explore New Horizons

Your license is a launchpad, use it to expand into new fields and opportunities.

Sharing your story inspires others and helps amplify the impact of the profession.

Deepen Your Expertise

Licensure gives you the chance to focus your skills and shape your expertise with intention.

Architects are systems thinkers, skilled at navigating complexity, balancing constraints, and crafting solutions that serve people and purpose. Your ability to problem-solve creatively, communicate ideas visually and verbally, and synthesize input from diverse stakeholders makes you well-equipped to lead in many fields.

“Licensure isn’t the finish line, but a launchpad for you to grow, connect, serve, promote, and pivot...”

Pivoting doesn’t mean stepping away from architecture, it means expanding its reach.

Give Back to the Profession and Community

Giving back strengthens both your leadership and the relevance of architects in society.

Acknowledgement: Grateful to Kathrine Lashley - YARArkansas - 2023/2024 for their research and insights, which helped shape and enrich this article.

Your architectural career is yours to design. Licensure isn’t the finish line, but a launchpad for you to grow, connect, serve, promote, and pivot in ways that align with your values and ambitions. Take time to map out your next steps: explore what excites you, gather resources that will support your goals, and seek out mentors who can help guide your journey.

As you step into this next chapter, remember: licensure marks the start of a career filled with creativity, impact, and lifelong growth—on your terms.

Stay tuned as we share deeper dives into each of these five pathways to help you shape your future with intention and confidence.

Katherine Lashley, AIA

Katherine is a Project Architect at Marion Blackwell Architects and has served as an active volunteer within AIA AR and the YAF.

Kumi Wickramanayaka, AIA

Kumi is passionate about public interest design and affordable housing, and currently serves as the YAR for DC and co-chair of the CKLDP DC program.

Schools may be one of the only building types that we as architects almost all have direct experience with, for most of us went to school in school buildings. What were our experiences in school? How did we relate to those buildings and more importantly how did those experiences shape who we are as architects and planners for the students of the future? When we design, we carry with us our own experiences and memories both positive and negative.

Our experiences shape who we are as designers and planners, but they also may impede our ability to listen openly to our students of today. Their needs and their experiences of the world and of school are very different than ours. Designing places that inspire students to come to school each day excited to learn begins with listening to students with an open heart and an open mind.

What happens when we listen? We learn what school experiences students find memorable, inspiring, and motivating. We learn what makes them feel that their school is for them and is designed with their needs in mind. We learn how they value and connect with their school’s identity. We learn what makes them feel safe.

This guidance informs the creation of schools with strong sense of place and an accessible and relevant identity. All aspects of the learning environment - from the welcoming entry to the comfortable shared spaces to the inspiring classrooms - shape and influence the student experience and create a place of belonging.

We learn from students that some of their most memorable learning experiences happened outside of the traditional classroom or were connected to a specific teacher or coach. As architects, we have less impact over interpersonal experiences than we do over placemaking which is our strength as designers. However, there are still opportunities to create learning environments that engage learners, beginning with identifying activities that motivate and inspire, provide a sense of purpose, and that bring joy. These are exciting spaces to plan and design because we utilize an essential skill of architects: “Tell us what you want to do and we will design a space to do it.” This process is an exciting and rewarding aspect of the planning and design of student-centered learning environments.

Outdoor learning environments are located adjacent to classrooms to engage students in nature-based learning, active play, and

environmental awareness. Landscaped school yards reflect and demonstrate native plants and ecosystems teaching students about their place in the world. Edible gardens and raised planters support interdisciplinary project-based learning opportunities integrating science, health, and geography.