Introduction

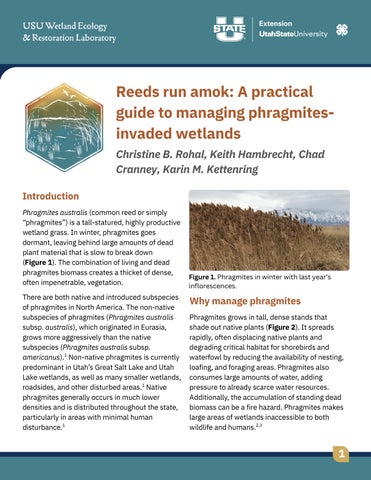

Phragmitesaustralis(commonreedorsimply “phragmites”)isatall-statured,highlyproductive wetlandgrass.Inwinter,phragmitesgoes dormant,leavingbehindlargeamountsofdead plantmaterialthatisslowtobreakdown (Figure1).Thecombinationoflivinganddead phragmitesbiomasscreatesathicketofdense, oftenimpenetrable,vegetation.

Therearebothnativeandintroducedsubspecies ofphragmitesinNorthAmerica.Thenon-native subspeciesofphragmites(Phragmitesaustralis subsp.australis),whichoriginatedinEurasia, growsmoreaggressivelythanthenative subspecies(Phragmitesaustralissubsp. americanus). Non-nativephragmitesiscurrently predominantinUtah’sGreatSaltLakeandUtah Lakewetlands,aswellasmanysmallerwetlands, roadsides,andotherdisturbedareas. Native phragmitesgenerallyoccursinmuchlower densitiesandisdistributedthroughoutthestate, particularlyinareaswithminimalhuman disturbance. 1 1 1

Phragmitesgrowsintall,densestandsthat shadeoutnativeplants(Figure2).Itspreads rapidly,oftendisplacingnativeplantsand degradingcriticalhabitatforshorebirdsand waterfowlbyreducingtheavailabilityofnesting, loafing,andforagingareas.Phragmitesalso consumeslargeamountsofwater,adding pressuretoalreadyscarcewaterresources. Additionally,theaccumulationofstandingdead biomasscanbeafirehazard.Phragmitesmakes largeareasofwetlandsinaccessibletoboth wildlifeandhumans.2,3

Phragmitesspreadsbothasexuallyandsexually, whichallowsittoproliferaterapidly. Asexually,it expandsbyproducingbelowgroundand abovegroundstemsthatgeneratenewshootsat patchedges. Sexually,asingleinflorescence (floweringhead)canproducethousandsofseeds eachfall,whicharedispersedthroughwindand water Inspringandsummer,seedsgerminate readilyinwetlandswheremoistsoilisdisturbed andexposed. 1

4

Itisnotalwayspossibletoeffectivelymanageall phragmitesonyourproperty.Prioritizehealthy, robustpatchesaccessibleovermultipleyears. Treatingpatchesnearestablishednativeplants willhelpprotectcrucialnativehabitatand promotepassivenativeplantrecruitmentin managedareas.Managingsmallerphragmites patchesismorelikelytoresultinlasting reductions. Refertothechecklistattheendof thisdocumentforadditionalguidanceonsite selection.

5

phragmites, but these treatments will not kill the plant (Figure 3). Herbicide application is currently the only method proven to effectively kill both aboveground and belowground plant parts, which is necessary to reduce or eradicate a phragmites patch. We recommend combining herbicides with physical treatments to remove dead phragmites biomass that would otherwise impede follow-up

When employing burning for biomass management, be sure to follow local burning restrictions. Fire photo: Jeremy Smith, USDA WS, public domain.

Physicaltreatmentssuchasmowing,burning,and grazingcanreducetheabovegroundbiomassof 1 2

herbicide treatments and prevent native plant germination and growth. As with all invasive plant management efforts, the timing of herbicide application and physical treatments is important for treatment effectiveness 6

Recommended integrated management timeline in Utah (Optionalstepforsmallerpatches)

Step 1.

Managebiomassbeforetreatment.In Year1,mow,cut,orintensivelygrazein thesummerbeforeherbicide application.

Note:Donotmow,cut,orgrazewithin 30daysofherbicideapplication(before orafter)

Repeat this process for 3 consecutive years, spottreating the regrowth. Mowing is most essential in the initial treatment year. If the initial herbicide treatments dramatically reduce phragmites cover, mowing may not be necessary in subsequent management years. Following the third year, monitor phragmites in treated areas and continue spot-treating as needed

Disruptingbirdnestingwithphragmites managementactivitiescouldviolatethe MigratoryBirdTreatyAct.

Step 2. Step 3.

Applyherbicide.Spraywithanaquaticapprovedglyphosateformulationin AugustorSeptember(Figure4).

Reducebiomassaftertreatment.Ifthe phragmitespatchwasnotmowedin summer,orgrewbacksignificantly,mow, cut,trample,orburnitinfallorwinter.

Note:Waitatleast30daysafter herbicideapplicationtoallowittotake effectfirst.

Note:Youmustfollowallherbicidelabels,asthe labelisthelaw.Alwayscalibrateyourspray equipmenttoensureyouachievethecorrect applicationrate.Applyingthelabel-recommended rateoptimizesherbicideeffectiveness,while applyingtoomuchisnotonlyineffectivebutalso illegal.

1.Spray-grade ammonium sulfate (8 to 17 pounds per 100-gallon spray solution). Add first.

2. Aquatic-approved glyphosate (use the high end of the labeled rate).

3. Aquatic approved non-ionic surfactant (use rate on label).

Alternatively,aquatic-approvedherbicides containingimazapyrcanalsobeeffectivein managingphragmites.However,imazapyrismore expensivethanglyphosate,breaksdownmore slowlyinthesoil(whichcouldimpedenativeplant recovery),andcomeswithmorelabel restrictions. Considerrotatingtoimazapyr,if permittedbythelabel,inareaswhereglyphosate hasbeenusedrepeatedlyforseveralyearstohelp slowthedevelopmentofherbicide-resistant plantsandsustainlong-termmanagement effectiveness.

The timing of herbicide application is crucial. Apply herbicide just before the plant goes dormant, between tasseling and first frost. The best herbicide timing depends on the location and is weather-dependent. However, in Northern Utah, it typically occurs between August and September. Ensure the plant is actively growing to absorb the herbicide effectively. Avoid spraying drought-stressed plants. Do not mow or graze phragmites within 1 month before spraying to allow for adequate regrowth for herbicide treatment. Avoid physical disturbances within 1 month after herbicide treatment to allow for maximum herbicide uptake and movement to the roots.

Avoid trampling recently sprayed phragmites whenever possible. Crushed stems may reduce herbicide translocation to the roots, resulting in reduced effectiveness.

Ifpossible,managingwaterlevelscan significantlyimprovephragmitesmanagementby increasingherbicideeffectivenessandpromoting nativeplantrecovery.

Water can be directed to phragmites patches in the months (ideally ≥ 1 year) before treatment to ensure it is healthy before spraying, which improves herbicide effectiveness (Figure 5).

After mowing, flooding sites as deeply as possible can help decompose the phragmites litter and potentially drown any stems that were not killed by the herbicide.

Following treatment years, drought-stressing treated areas will help suppress phragmites regrowth and promote the establishment of drought-tolerant plants such as pickleweed (Salicornia rubra) and saltgrass (Distichlis spicata). However, if the objective is to reestablish emergent plants, such as bulrushes (Schoenoplectus and Bolboschoenus species), deeper water levels will be required.

Once native vegetation is established, following a natural hydrologic cycle (characterized by high water levels in spring, phasing to little or no water in early summer, typically mid to late May) will support native plant persistence and reduce phragmites spread.

Caution: Leaving shallow water on an area all summer and into the fall will promote phragmites germination and growth.

Figure 5. Installing a board in a headgate used to control water levels in an impounded wetland. Managementoptionstoreduce phragmitesspread Often,therearenotenoughresourcestomanage allphragmitespatcheswithmultipleyearsof herbicideandphysicaltreatments.Inthesecases, thereareothermanagementtoolsavailableto reduceseedproductionandlimittheoutward expansionofpatches:

Summer grazing and mowing can reduce phragmites seed production and slow the expansion of clones. See the Utah Stat University Extension fact sheet by Dunca colleagues (2019) for more information integrating grazing into phragmites management. 6,8 9

If physical treatments (e.g., mowing, gra are not possible, well-timed herbicide sp will at least prevent the plant from sprea though natives are unlikely to establish in dense, dead phragmites stands that rem Areas that you are unable to treat with h can be drought-stressed to minimize phragmites spread through patch expansion and seed production.

Avoid disturbances (such as mowing) in intact native communities adjacent to phragmites patches, especially during spring and summer. Minimizing soil disturbance reduces warm, moist, bare soil conditions that facilitate phragmites seed germination and the establishment of new phragmites patches.

Nativeplantrecruitmentfollowingmanagement isessentialbecauseithelpsrestorehabitatand limitthereinvasionofphragmites.Rapidly establishingdiversenativeplantstocovernewly exposedsoilisanapproachtolimitthereturnof newphragmitespatchesfollowingherbicide management.

Phragmites patches that are newer or adjacent to established native plants are more likely to have a diverse and robust native seed bank to promote passive native plant recruitment (Figure 6). Research has shown that native plant cover in treated areas following phragmites management is higher in patches with diverse native plants in the surrounding area.10

Phragmites patches that are older or distant from established native plants may have depleted native seed banks, leading to poor native plant recruitment following management. Active revegetation through seeding and planting is the most effective option to quickly establish plants that can outcompete phragmites (Figure 7). Dense native plant cover reduces the moist, bare soil conditions that phragmites seeds need to germinate.

Do not rush into native plant revegetation in the first year; wait until phragmites cover is significantly reduced and you can assess the extent of natural recovery. Follow-up herbicide may kill any recently established native plants. Detailed information on the best approaches

for seeding and planting native plants following phragmites management are detailed elsewhere.12,13

Figure 7. Revegetating a wetland with sod mats after multi-year phragmites management. Photo credit: Utah Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands (with permission).

Prioritize sites with more favorable site conditions to achieve the greatest reduction in phragmites cover and to foster native plant recovery. Expect that sites with less favorable conditions will require more resources (e.g., more years of management, more revegetation) to achieve management goals.

Resources secured for multiple years of herbicide treatments

Phragmites patch accessible to machinery

Phragmites patch is healthy (not drought stressed)

More favorable----------------------------------------------------------------------------Less favorable

Diverse native community nearby--------------------Adjacent native community largely absent

Neighboring phragmites patches absent-------------Neighboring phragmites patches adjacent (fewer phragmites seeds around) (more phragmites seeds around)

Small (< 1 acre) phragmites patch-----------------------------Large (> 1 acre) phragmites patch

Recent (< 5 years ago) phragmites patch arrival---Long term (> 5 years ago) patch persistence

Water control available------------------------------------------------------------No water control

Literaturecited

Kettenring,K.M.,&Mock,K.E.(2012).Geneticdiversity,reproductivemode,anddispersaldiffer betweenthecrypticinvader,Phragmitesaustralis,anditsnativeconspecific.BiologicalInvasions,14, 2489–2504.

2

1 Kettenring,K.M.,deBlois,S.&Hauber,D.P.(2012).Movingfromaregionaltoacontinental perspectiveofPhragmitesaustralisinvasioninNorthAmerica.AoBPlants,1–18.

Rohal,C.B.,Kettenring,K.M.,Sims,K.,Hazelton,E.L.G.,&Ma,Z.(2018).Surveyingmanagersto informaregionallyrelevantinvasivePhragmitesaustralisresearchprogram.JournalofEnvironmental Management,206,807–816.

4

3 Kettenring,K.M.,Mock,K.E.,Zaman,B.,&McKee,M.(2016).Lifeontheedge:reproductivemode andrateofinvasivePhragmitesaustralispatchexpansion.BiologicalInvasions,18,2475–2495.

5

Rohal,C.,Cranney,C.,&Kettenring,K.M.(2019).Abioticandlandscapefactorsconstrainrestoration outcomesacrossspatialscalesofawidespreadinvasiveplant.FrontiersinPlantScience,10,1–17.

Rohal,C.,Cranney,C.,Hazelton,E.,&Kettenring,K.M.(2019).InvasivePhragmitesaustralis managementoutcomesandnativeplantrecoveryarecontextdependent.Ecology&Evolution,9, 13835–13849.

7

6 Hazelton,E.L.,Mozdzer,T.J.,Burdick,D.M.,Kettenring,K.M.,&Whigham,D.F.(2014).Phragmites australismanagementintheUnitedStates:40yearsofmethodsandoutcomes.AoBplants,6,plu001.

Rohal,C.B.,Duncan,B.,FollstadShah,J.,Veblen,K.E.,&Kettenring,K.M.(2024).Targetedgrazing reducesawidespreadwetlandinvaderwithminimalnutrientimpacts,yetnativecommunityrecovery islimited.JournalofEnvironmentalManagement,362,121168.

8 Duncan,B.,Hansen,R.,Hambrecht,K.,Cranney,C.,FollstadShah,J.J.,Veblen,K.E.,&Kettenring,K. M.(2019).CattlegrazingforinvasivePhragmitesmanagementinNorthernUtahwetlands[Factsheet]. UtahStateUniversityExtension.

10

9 Rohal,C.B.,Hazelton,E.L.G.,McFarland,E.,Downard,R.,McCormick,M.,Whigham,D.,Kettenring, K.M.(2023).LandscapeandsitefactorsdriveinvasivePhragmitesmanagementandnativeplant recoveryacrossChesapeakeBaywetlands.Ecosphere,14,e4392.

11

Rohal,C.B.,ReinhardtAdams,C.,Reynolds,L.,Hazelton,E.L.G.,&Kettenring,K.M.(2021).Do commonassumptionsaboutthewetlandseedbankfollowinginvasiveplantremovalholdtrue? Divergentoutcomesfollowingmulti-yearPhragmitesaustralismanagement.AppliedVegetation Science,24,e12626.

Tarsa,E.,Robinson,R.,Hebert,C.,England,D.,Hambrecht,K.,Cranney,C.,&Kettenring,K.(2022). Seedingtheway:AguidetorestoringnativeplantsinGreatSaltLakewetlands.UtahStateUniversity Extension.

13

12 Braun,J.V.,Robinson,R.,Henry,A.L.,&Kettenring,K.M.(2025).Restoretheshore:Aguideto lakeshorerevegetationintheGreatBasin.UtahStateUniversityExtension.

Thisresearchwassupportedby:CommunityFoundationofUtah;DeltaWaterfowl;DucksUnlimited Canada;EnvironmentalProtectionAgency;FriendsofGreatSaltLake;IntermountainWestJoint Venture;KennecottUtahCopperCharitableFoundation;SaltInstitute;SocietyofWetlandScientists; SouthshoreWetlands&WildlifeManagement,Inc.;U.S.Fish&WildlifeService;USUEcologyCenter andOfficeofResearch&GraduateStudies;UtahAgriculturalExperimentStation;UtahDepartmentof AgricultureandFood;UtahDivisionofForestry,Fire&StateLands;UtahDivisionofWaterQuality; UtahDivisionofWildlifeResources;UtahWaterfowlAssociation;UtahWetlandsFoundation;and WetlandFoundation.ThankyoutoAnnieHenryforgraphicdesignsupport.

Authorsprovidedphotos,unlessotherwisenoted.

In its programs and activities, including in admissions and employment, Utah State University does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination, including harassment, based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy, Title IX, or any other federal, state, or local law Utah State University is an equal opportunity employer and does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination including harassment in employment including in hiring, promotion, transfer, or termination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University does not discriminate in its housing offerings and will treat all persons fairly and equally without regard to race, color, religion, sex, familial status, disability, national origin, source of income, sexual orientation, or gender identity Additionally, the University endeavors to provide reasonable accommodations when necessary and to ensure equal access to qualified persons with disabilities The following office has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the application of Title IX and its implementing regulations and/or USU’s non-discrimination policies: The Office of Equity in Distance Education, Room 400, Logan, Utah, titleix@usu edu, 435-797-1266 For further information regarding non-discrimination, please visit equity usu edu, or contact: U S Department of Education, Office of Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 800-421-3481, ocr@ed gov or U S Department of Education, Denver Regional Office, 303-844-5695 ocr.denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U S Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L White, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University

This peer-reviewed document was published September 2025 by Utah State University Extension.