Forage Sampling Guide for Agronomic Crops

Jody Gale, Matt Yost, Megan Baker, Mike Pace, Earl Creech, Grant Cardon, Kalen Taylor, Cody Zesiger, Tiffany Evans, Rhonda Miller, and Clara Anderson

Why Sample?

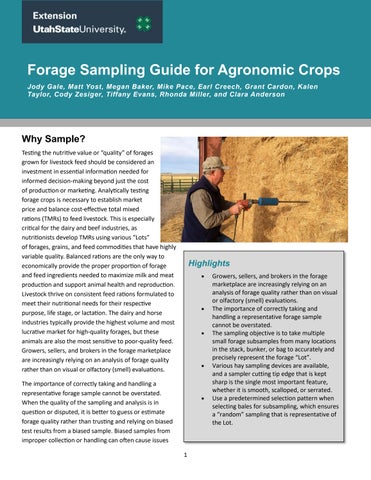

Testing the nutritive value or “quality ” of forages grown for livestock feed should be considered an investment in essential information needed for informed decision-making beyond just the cost of production or marketing. Analytically testing forage crops is necessary to establish market price and balance cost-effective total mixed rations (TMRs) to feed livestock. This is especially critical for the dairy and beef industries, as nutritionists develop TMRs using various “Lots” of forages, grains, and feed commodities that have highly variable quality. Balanced rations are the only way to economically provide the proper proportion of forage and feed ingredients needed to maximize milk and meat production and support animal health and reproduction. Livestock thrive on consistent feed rations formulated to meet their nutritional needs for their respective purpose, life stage, or lactation. The dairy and horse industries typically provide the highest volume and most lucrative market for high-quality forages, but these animals are also the most sensitive to poor-quality feed. Growers, sellers, and brokers in the forage marketplace are increasingly relying on an analysis of forage quality rather than on visual or olfactory (smell) evaluations.

Highlights

• Growers, sellers, and brokers in the forage marketplace are increasingly relying on an analysis of forage quality rather than on visual or olfactory (smell) evaluations.

• The importance of correctly taking and handling a representative forage sample cannot be overstated.

• The sampling objective is to take multiple small forage subsamples from many locations in the stack, bunker, or bag to accurately and precisely represent the forage “Lot”.

The importance of correctly taking and handling a representative forage sample cannot be overstated. When the quality of the sampling and analysis is in question or disputed, it is better to guess or estimate forage quality rather than trusting and relying on biased test results from a biased sample. Biased samples from improper collection or handling can often cause issues

• Various hay sampling devices are available, and a sampler cutting tip edge that is kept sharp is the single most important feature, whether it is smooth, scalloped, or serrated.

• Use a predetermined selection pattern when selecting bales for subsampling, which ensures a “random” sampling that is representative of the Lot

for all sides of feed transactions. Growers can be unfairly compensated for their forage, unhappy buyers may not receive the quality they expected and paid for, and unhappy livestock owners and nutritionists may experience unexpected livestock performance.

This guide provides practical, research-based information for forage growers, buyers, livestock owners, and nutritionists about how to properly sample various types of dry and ensiled forage for submission to a testing laboratory for quality analysis, ensuring unbiased analytical results.

What Can Be Sampled?

Any forage that is grazed, harvested, and marketed as a livestock feed can be tested for quality, nutritional value, and the presence of some toxins that can harm or kill livestock. The most common forages marketed or used in livestock rations that should be tested include: alfalfa, corn, small grain mixtures, grass hay, grass/alfalfa mix, and sudangrass, sorghum sudangrass, or sorghum. Forage quality is primarily determined by the plant species, maturity at harvest, and weather conditions during harvest and storage. Some forages need to be analyzed for toxic or poisonous compounds in addition to feed quality. Drought-stressed oats and weedy hay can accumulate nitrates to dangerous levels, and sudangrass crops that have experienced frost near harvest can potentially contain excessive amounts of prussic acid. Untested feed can result in sick or dead animals, and the ensuing economic losses can be catastrophic for a business.

When to Sample?

According to the National Forage Testing Association (NFTA), forages should be tested just before they are used (Putman & Orloff, 1998). Further, the results are most needed just before making a major marketing decision to buy or sell forages or to balance a TMR. Though not common, forages can easily be sampled “on the stump” as they are growing in the field, long before harvest. Results from periodic testing of forage crops as they mature is a great way to track changes in quality to best predict the optimal harvest time to maximize quality, yield, and economic returns of alfalfa (Gale, 1988). Avoid sampling alfalfa and other baled forages hay for at least 30 days after baling to allow the forage to complete its natural “sweat” cycle. Also, avoid sampling forages that are ensiled until at least 5 to 6 weeks after first ensiling when the fermentation process is completed.

How to Sample?

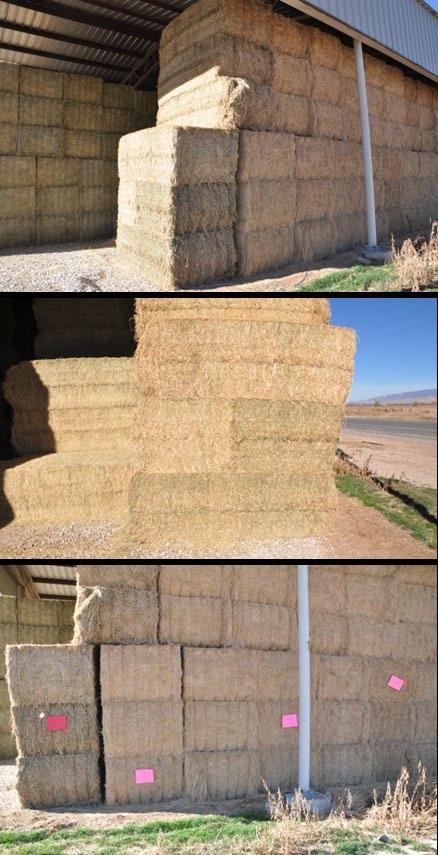

Figure 1. Three Views of the Same Alfalfa Stack

Note: In the top image, the six alfalfa bales in the foreground and front part with a darker color is a different lot than the rest of the stack. In the bottom image, alfalfa in the different lots have red or pink markers for sampling.

Ensuring a representative sample is taken is essential for an accurate analysis. The process of taking a representative sample of any crop or material on a farm, including dry hay, wet silage, seed, soil, and irrigation water for quality testing, shares similar basic concepts. When done correctly, sampling is straightforward and relatively easy with the right equipment. The objective of sampling is to take multiple small subsamples of the forage, or material of interest, from many locations in the stack,

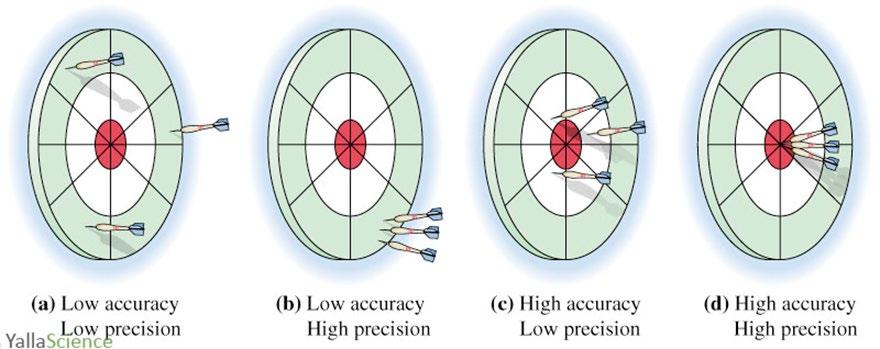

2. Illustration of the Concepts of Precision and Accuracy

Photo credit: Yalla Science, Freefullpdf for Scientific Publications

bunker, or bag in such a way that the composite sample, which consists of the combined subsamples, accurately and precisely represents the relatively large quantities of what is being evaluated (Figure 1). Figure 2 illustrates the difference between the concepts of accuracy and precision that are important to understand. Representative samples are not biased when both concepts are addressed. Only taking one or two subsamples per composite sample will not be representative of the forage and will result in biased results.

Hay Sampling Devices

There are several different types of hay samplers that meet NFTA requirements (Figure 3). Some of the most common are the straight tube, multiple core collection, and bulb-out samplers. Required design features of samplers include a 12inch to 24-inch long hollow tube (not an open auger type) having a 3/8-inch to 3/4-inch diameter cutting tip. You can purchase these samplers from various sources. They can be costly, and often neighbors, feed distributors, or county Extension offices have samplers to borrow. There are some convenient design features, including adaptors for electric drills, to consider if several lots are being sampled.

Hay Sampler Types

• Straight tube

• Multiple core collection

• Bulb-out

Sampler Considerations

• Manual or drill insertion

• Length

• Ease of use

• Cost

• Durability

• Sharp cutting tip edge

Each sampler has unique strengths and weaknesses to the design that should be noted before using. Some of the considerations include manual or drill insertion, length, ease of use, cost, and durability. Straight tube samplers have the same diameter inside the cutting tip as the collection tube, and there is a risk of friction heat damage to the core affecting quality analysis when samples are taken too rapidly. This is especially a problem with dense bales. Samplers with multiple core collection chambers and exterior spiral assist on the hollow collection tube are especially useful. Bulb-out-type tips, which have a larger outside tip diameter than outside diameter of the collection tube, are particularly well-designed and easy to use. Tips that are easily sharpened or have replaceable cutting tips can reduce maintenance costs. The single most important feature of the sampler cutting tip edge is that it is kept sharp whether it is smooth, scalloped, or serrated. Without a sharp tip, stems will be pushed aside as the core is taken, misrepresenting the bale.

Figure

What Is a Hay or Silage “Lot” and Why Is It Important?

When sampling forage, the first step is to identify material, such baled hay or wet forage, that has all been treated the same. This grouping is referred to as a “Lot.” This Lot includes forage that has come from the same field, variety, planting, soil type, fertility, irrigation, maturity (especially important), cutting time (within about 48 hours), baling or chopping conditions, equipment, etc. A forage Lot may contain a maximum of about 200 tons. Forage that is not treated the same should be identified, separated (if possible), and labeled as a separate Lot (Figures 1 and 4).

Figure 4. Examples of Random Sampling Patterns for Different Hay Lots

Figure 3 Examples of Various Hay Sampling Devices

Dry Forages

Sampling dry baled hay is relatively straightforward. Once the Lot has been identified, use a hay sampling device with a sharp tip (features will be discussed later) to extract forage cores according to NFTA recommendations.

• Sampling Pattern - It is important to use some kind of predetermined selection pattern when selecting bales for subsampling. A selection pattern ensures a “random” sampling that is representative of the Lot (Figure 4). Using a pattern also ensures that personal bias or tendencies to skip or select a particularly bad or good bale of hay are avoided. If a sampling pattern is not used, sampled bales may reflect the bias of the person sampling (selling vs. buying hay). Figure 4 shows examples of how patterns could be used to take representative samples from large and small haystacks. One simple pattern is to select the same bale in each row or column in a stack.

• Sample Collection“Grab samples” taken by hand without a sampling device are not an accepted way of sampling dry forages. This method often results in lower than actual forage quality values. This is because the fine, shattered plant parts, mainly leaves, drop to the ground and are lost, skewing the sub and composite sample. Leaves of alfalfa, grass, and other forages contain a much higher percentage of protein and other important plant nutrients and contribute more to improved feed quality than stems (Gale et al., 2019)

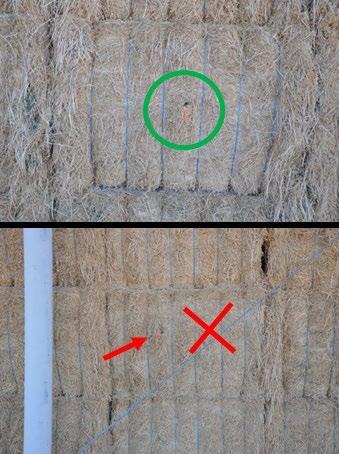

When sampling dry forages, each subsample core is taken by screwing or thrusting the respective sampling device straight in the center of the butt end of the bale between the strings (Figures 5 and 6). When sellers take subsample cores from only the bottom of the bale or buyers only take cores from the top of the bale, it will bias the results and does not meet NFTA sampling protocol. Between each core collected, it is very important to use the sampler push rod to plunge the collection tube. This reduces back pressure and ensures that the core will be cut uniformly throughout the bale (Figure 5). It is also critical that the sampling device has a sharp cutting tip. A dull tip can bias the core by pushing stems out of the way of the penetrating collection tube and collecting more fine materials.

• Sample Size - At least one composite sample should be taken for each Lot being analyzed. The composite sample should consist of 20 subsamples (or cores) each from different bales and weigh around ½ pound (200 grams or ½ gallon). If the Lot size is less than 20 bales, 20 subsamples are still recommended to get a large enough sample for analysis. For large Lots, increase subsamples or collect multiple samples with 20 subsamples. The size of the composite sample is important because a tablespoon of ground sample will represent many tons of forage. Having extra sample allows you to send it to multiple labs if necessary or desired. A dry sample larger than a ½ pound is not an issue if it is ground before sending to the lab. Most labs cannot handle large samples and may only grind a portion of the sample, introducing bias because the whole lot will not be represented in the analysis (Teutsch et al., 2020).

Figure 5. Examples of Correct (top) and Incorrect Sampling the Center of Hay Bales, When the Sampler Tried to Avoid the Hay Barn

Structural Cable

• Sample Storage - The most practical bags for dry and wet samples are heavy-duty freezer-rated plastic bags. These bags have a thicker plastic and are better able to resist punctures from dry stems. Be sure to label each sample to identify the Lot of hay it represents (Figure 7).

Wet or Ensiled Forages

Many of the principles and methods used to sample dry forages also apply to wet and ensiled forages. Some differences and special considerations for ensiled forages in bunkers, pits, bags, and wrapped bales (Figure 8) follow.

• When - For all ensiled forages, wait 5–6 weeks before sampling to ensure the fermentation process is complete.

• How - Sampling devices used for dry forages do not typically work for loose silage and wet forages. Thus, it is often best to collect a “grab sample, ” because wet forage has a much lower risk of loss with this method than dry forages do When sampling from the side of ensiled forage bags, cut two of three sides of a 6-inch triangle on the side of the plastic bag. Dig out 4–6 inches of non-surface forage before collecting subsamples. Immediately seal the sample flap with permanent plastic tape to prevent spoilage by oxygen contamination. Take multiple subsamples (at least four or five) along the length of the bag to make a composite sample that is at least a half-gallon of forage. The number of samples to collect should be relative to the size of the Lot, with more samples for larger Lots. Combine and thoroughly mix the subsamples in a plastic bucket, then collect enough to fill a sample bag.

Figure 6. Baled Forage Comes in Several Bale Types and Dimensions

Note: All should be sampled on the butt end except for round bales, which should be sampled between the strings.

• Where - When filling the bunker, pit, bags, and wrapped bales, be sure to mark differences in forage Lots with permanent markings or records so they can be sampled separately if needed. Also, be sure to collect a representative sample from a clean and fresh face of a bunker, pit, or bag. Collecting samples from the patchable sides of bags is also acceptable.

• Transport - Each laboratory can vary in terms of their shipping instructions, so the best practice is to contact the lab for their specifications regarding packaging, temperature control, overnight or time of week, etc.

Figure 7. Ground Composite Sample Ready for Certified Lab Analysis

8. Examples of Ensiled Forages That Require Different Sampling Methods Than Dry Forages

Sample Handling

It is vital to properly handle, store, and transport composite forage samples. If the sample is excessively heated when the core is taken, the protein in the sample will be damaged, leading to a biased sample (Coblentz et al., 2010). Excessive heating can occur when using a sampler with a dull tip or when samples are left in sunlight (e.g., a pickup’s dashboard). Keep dry forages cool, dry, and out of the sunlight. Keep ensiled samples cold and tightly sealed, with as little pore space in the bag as possible. An appropriately sized ice chest with ice will keep the ensiled sample fresh and in good condition.

Check with your lab for shipping instructions, but samples should usually be hand-delivered or shipped overnight to the lab in a cold or frozen state in a foam-insulated shipping box with dry ice. It is best to ship all forage samples to labs at the beginning of the week, so they do not end up in a truck or mail room over a weekend or holiday. Large samples of dry forage should never be split after sampling and before grinding. The lab may apply a surcharge for extra-large samples. Large samples must be pre-ground through a mill before subsampling. The coarse ground sample can then be split and subsampled.

Selecting a Laboratory for Analysis

When selecting a laboratory to analyze your forage sample, it is important to ensure the lab participates in an independent third-party data quality assurance or accreditation program (see the NFTA web page for an example list of certified labs). Other factors to consider include:

• Shipping and analysis costs

• Turnaround time to obtain results

• Quality of analytical methods and test result interpretations

• Certifications (type and most recent)

• Declared or undeclared conflicts of interest if laboratories are connected to commercial sales

What to Sample?

Consider the end use of the forage when deciding which forage quality parameters to measure. Various buyers and forage markets may evaluate different metrics, so be sure to determine which parameters will be required. Forages not marketed but rather used on one’s own farm or ranch may require different parameters. The most common parameters used for alfalfa and hay markets are crude protein (CP), acid detergent fiber (ADF), total digestible nutrients (TDN), and relative feed value (RFV) and/or relative forage quality (RFQ) (U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Marketing Service [USDA-AMS], 2025). Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and various measures of NDF digestibility after 30 or 48 hours in the rumen are common measures used in TMR balancing, especially for dairy cattle.

Figure

Many analytical methods can be used to measure forage quality. Their respective use has changed over time with improvements in analytical technology, market forces, and increased understanding of livestock nutrition. It is important to recognize that some quality indicators are measured (e.g., CP, ADF, NDF), while others are calculated based on the measured indicators (e.g., RFV, RFQ). Measurements are typically made by wet chemistry or near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). Wet chemistry is available in public or private laboratories and is the traditional method, using research-based methods that have been available for over a century. It is more expensive than NIRS. Since the mid-1980s, NIRS technology has also become available in public or private laboratories and is a widely used, standardized, research-based method in the marketplace. Most laboratories will offer both wet chemistry and NIRS options.

Summary

Forage sampling is a valuable tool that provides producers with quality information for calculating feed rations and marketing their forages. To ensure that this information is accurate and reliable, it is important to understand how to collect these samples correctly. Sampling tools have been developed that simplify this process and improve accuracy. The collection and processing of dry and wet forages differ, and it is important to check with the intended analysis laboratory to ensure you follow the correct steps. Choose the laboratory based on the cost of analysis, quality certifications, and the methods used. To provide the desired information for management decisions, all these factors should be considered when collecting forage samples. By taking care to ensure the proper techniques are used, the information obtained can improve the experience for all involved in producing and using forages.

References and Resources

Coblentz, W. K., Hoffman, P. C., & Martin, N. P. (2010). Effects of spontaneous heating on forage protein fractions and in situ disappearance kinetics of crude protein for alfalfa–orchard grass hays packaged in large round bales. Journal of Dairy Science, 93(3), 1148–1169. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2009-2701

Gale, J., Creech, E., Shewmaker, G., & Putnam, D. (2019). Forage sampling protocols and hay sampling device features. In: Proceedings, 2019 Western Alfalfa and Forage Symposium, Reno, NV, 19-21 November, 2019. UC Cooperative Extension, Plant Science Department, University of California, Davis https://alfalfasymposium.ucdavis.edu/+symposium/proceedings/2019/Articles/Forage%20Sample_Gale_Article.pdf Gale, J. A. (1988). A simple model to predict optimal harvest time of alfalfa using near infrared reflectance spectroscopy, environmental, morphological, and growth parameters Utah State University: All Graduate Theses and Dissertations, Spring 1920 to Summer 2023. 7454. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7454

Iowa Beef Center. (2024). Hay sampling. [Video]. Iowa State University. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVfWWaTdB9o.

National Forage Testing Association (NFTA). (2024). Forage sampling [Website]. https://www.foragetesting.org/foragesampling. Note: This webpage has resources that include sampling recommendations, certified labs, and exam requirements for certification.

North American Proficiency Testing Program (NAPT). (2024). [Website]. https://www.naptprogram.org/.

Oregon State University Extension. (2024). How to sample a lot of hay [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=brXDU47Ww0U. Note: Some errors included sampling too high on bale, too few cores, and using a hot sampler.

Putnam, D., & Orloff, S. (1988). Proper sampling methods improve accuracy of lab testing. University of California Summer 1988 California Alfalfa & Forage Review. https://www.foragetesting.org/_files/ugd/a8d5e8_4d1d9d8016d04bd4a0954cf4d0dad669.pdf

Putnam, D., & Orloff, S. (1998). Recommended principles for proper hay sampling. National Forage Testing Association. https://www.foragetesting.org/exam-info.

Putnam, D., & Orloff, S. (n.d.). Hay sampling protocols and a hay sampling certification program. In Western Alfalfa & Forage Conference, Reno, NV University of California Cooperative Extension, University of California, Davis https://alfalfasymposium.ucdavis.edu/+symposium/proceedings/2002/02-149.pdf

Rock River Laboratory. (2014). Sampling from a silo bag [Video]. Rock River Laboratory. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UTJJLLrLPtg&ab_channel=RockRiverLaboratory Note: Use for face sampling only.

Teutsch, C., Bush, J., Keene, T., & Henning, J. (2020). Hay sampling strategies for getting a good sample [Fact sheet] University of Kentucky Extension. https://publications.ca.uky.edu/sites/publications.ca.uky.edu/files/AGR257.pdf. The University of Maine. (2024). How to test forage quality [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rP_nOx4OHFU. Note: Splitting unground samples is not recommended.

Undersander, D., Shaver, R., Linn, J., Hoffman, P., & Peterson, P. (2014). Sampling hay, silage and total mixed rations for analysis. University of Wisconsin Extension. https://forage.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/WI-A2309ForageSampling-Undersander-etal-20051.pdf

UNL BeefWatch. (2024). How to take a representative forage sample [Video]. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rTGkb_u1838. Note: Splitting unground samples is not recommended.

University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. (2017). Choice and utilization of hay probes. University of California and Utah State University Extension. http://lecture.ucanr.edu/Mediasite/Play/573a4f03d3e74c6581bb77fe89922af81d

University of Minnesota Extension. (2015). Taking a hay sample [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sJMyvYyYZek. Note: Grab sampling can cause biased data that can be more misleading and harmful than no data at all U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA-AMS) (2025). Utah direct hay report. USDA AMS Livestock, Poultry & Grain Market News. https://www.ams.usda.gov/mnreports/ams_3731.pdf

Utah State University Extension. (2024). Where can I submit my soil and plant samples at USU? [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NeFB8La8NkA Note: See the forage testing tour at 8:57 minutes. Ward Laboratories, Inc. (2024). Hay sampling procedure [Video]. Ward Laboratories, Inc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7BMymkY_em8

Authors provided all photos, unless otherwise noted

In its programs and activities, including in admissions and employment, Utah State University does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination, including harassment, based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy, Title IX, or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University is an equal opportunity employer and does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination including harassment in employment including in hiring, promotion, transfer, or termination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University does not discriminate in its housing offerings and will treat all persons fairly and equally without regard to race, color, religion, sex, familial status, disability, national origin, source of income, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Additionally, the University endeavors to provide reasonable accommodations when necessary and to ensure equal access to qualified persons with disabilities. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the application of Title IX and its implementing regulations and/or USU’s non-discrimination policies: The Office of Equity in Distance Education, Room 400, Logan, Utah, titleix@usu.edu, 435-797-1266. For further information regarding non-discrimination, please visit equity.usu.edu, or contact: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 800-421-3481, ocr@ed.gov or U.S. Department of Education, Denver Regional Office, 303-844-5695 ocr.denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L. White, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University. July 2024 Utah State University Extension

September 2025

Utah State University Extension Peer-reviewed fact sheet