The MESSENGER

October, 1924

October, 1924

1. Richmond College, a College _ of Liberal Arts for Men.

2. Westhampton College, a College of Liberal Arts for Women.

3. The T. C. Williams School of Law, a Professional School of Law, offering the Degree of LL. B.

4. The Summer School. W. L. Prince, M. A., Director.

W. L PRINCE , M.A., DEAN

Richmond College for Men is an old and well-endowed College of Liberal Arts , which is recognized everywhere as a Standard American College. Its degrees are accepted at face value in the great graduate and technical schools of America . Its alumni are so widely scattered through the nation that the new graduate immediately joins a large and friendly group of men holding positions of power and influence. The College occupies modern and well-equipped buildings, on a beautiful campus of 150 acres in the western suburbs of Richmond.

MAY LANSFIELD KELLER, PH. D., DEAN

Westhampton College for Women, co-ordinate with Richmond College for Men, is housed in handsome buildings on a campus of 140 acres, separated from the Richmond College campus by a beautiful lake of about nine acres. All degrees are given by the University of Richmond, and those conferred on women are, in all respects, equivalent to those conferred on men. While the two institutions are co-ordinate, they are not co-educational.

J. H. BARNETT, JR., LL. 8., SECRETARY

Three years required for degree of LL. B. in the Morning Division, four years in the Evening Division. Strong faculty of ten professors. Large Library. Moderate Fees. Open to both Men and Women. Students who so desire can work their way.

For catalogue, booklet, or views, or other information concerning entrance into any College, address the Dean or Secretary.

F. W. BOATWRIGHT President

HERBERT L. SMITHERS ____________________________Editor-in-Chief

J. CHESTER SWANSON ___________________________Business Manager

WILMA SPANGLER _________________________________Editor-in-Chief

LILA CRENSHAW ________________________________Business Manager

DR. KELLER _____Advisory Editor

DR. LANDRUM _____________________________________Advisory Editor

All contributions should be handed to the department editors or the Editor-in-Chief by the 1st of each month preceding. Business communications and subscriptions should be directed to the Business Manager and Assistant Business Manager, respectively. Address-

l

This issue marks another year in the history o'f ~HE MESSENGER. It has behind it many years of notable success. But as glorious as its success has been, that will not suffice. We cannot live off of the past. We must constantly look to the future.

If THE MESSENGERis to continue to be a success, a greater interest must be aroused in literary work. There is an appalling laxity on the part of students as regards literary endeavor. Why such a lack of interest? Is it because some feel it would be of little or no use to write, since there are others who can write much better than they? If this be the attitude of some, now is the time to change it. You never know what you can do until you really put forth an honest effort. You may be able to write as good or better than any of the present contributors. Who knows? Let us find out. Why not at least make an attempt. No harm can result. And if your first contribution isn't accepted, don't get discouraged and quit. Just remember the old saying, "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again."

As we said before, however, more writing is the supreme need of our periodical. Next month let the editor be swamped with contributions. Let us all pull together and make THE MESSENGER the best college magazine in the State.

-H. L. S.

This is a new year for THE MESSENGER,and as is the custom at New Years we want every person to make a resolution. A resolve to help THE MESSENGERall you can through this year. If you have a thought, put it down, then hand it in. THE MESSENGERis your magazine, not the editor's. The editor is merely one you appointed to choose and arrange your material. With no material, what can an editor do? Take interest in making this a magazine you would enjoy showing as a representation of Westhampton culture, like your year book. Are you proud to have your MESSENGERsent in exchange to other colleges?

Let's go and make THE MESSENGERfor 1924-'25 the best yet.

- W. H. S.

· LESLIE L. JONES

First, let us decide j u st what const itutes idleness. An idler. There are no end of definitions for t his term. To the captain of industry, to the pseudo -captain of industry, to the would-be-captain of industry - in short, to the typical, bustling business man, from the most rotund chairman of the board of a billion dollar concern to the most recently enrolled freshman in the Alexander Hamilton Instit u te of Modern Business, an idler is a queer sort of person who does not wax enthusiastic over golf, is not interested in the complex details of commerce, does not read The American Magazine, and considers Joseph Conrad a greater novelist than Harold Bell Wright. An idler, then, as defined by the dominant spirit of the times - the spirit of aggressive success, the spirit of constantly accelerating progress, the spirit of getting on - is nothing less than a dissenter, a non-conformist. And there is nothing more disturbing to the model citizen than your non-conformist. After all his hot chasing of the fluttering greenbacks; after all his hurrying himself into a nervous breakdown, and into a sanitorium; after all his fus sing and mussing about with contracts, orders, conferences, and such other serious concerns; it rather takes the conceit out of a "peppy" gent to find some sleek, calm fellow lounging serenely through life utterly indifferent to the success-,. of his perspiring neighbor.

Of course, now, there are other ideas as to what composes idleness. The poet bemoans the dullness of the business man, and the scientist pities both the poet and the merchant. These, however, are only minor aspects of this engaging question . The prevailing notion is that first mentioned. Success, material succ ess, is the catchword, and Modern Business is the shrine at which a restless world now worships. To disdain the lu re of Commerce is to be marked down a fool, an exotic, a queer one Push, Pep, Persistence - these are the qu al ities exto lled by an efficiency-mad people, and not to throw your energies into approved, acknowl-

edged channels ( channels productive of dollars) is to fail miserably in Life. So sing the champions of Busy-ness. But may not other tunes be su ng? May not a few kind words be said upon the side of Idleness? Aye, marry, there may. And here they are.

Youth, of all times, is the time to be idle. And herein we find one of our strongest arguments for a college education. In spite of perspiring professors and ambitious parents, the knowledge acquired by the average student during his first two years of the higher learning is largely confined to forward passes, petting parties, and the cultivation of a taste for distinctive haberdashery. But is this a condition to be deplored? I do not think so. When arteries begin to ossify, and stomachs to lose their tone, and overshoes become requisite on misty mornings, what is it a man regrets the most? Dull, instructive moments in chapel? Sleepinviting lectures in stuffy classrooms? Or is it those afternoons he wasted in many a rousing "bull session?" Or those midnight hours thrown away in moving rhythmically across polished floors to the sound of a slow_ waltz? No, I am afraid it is not the midnight oil he regrets_:_ the midnight oil and ponderous tomes of history, and science, and math. It is those mad moments of Youth he laments those foolish, futile moments of idleness when hearts beat high, and the blood of twenty raced hotly. For large, white moons are idle things, and honeysuckle vines serve no useful purpose. Hammocks are mere thieves of fleeting hours. And gasoline burned in wild, nocturnal rides is a fearful, and idle, waste of an economic good. Thus croak the HighPriests of Success.

"Ply thy books," says the correspondence schools. "Ply thy books," say the uplift magazines. "Ply thy books," says the successful man, the man who has arrived. Arrived where? At the harbor of financial independence, City of Success, Land of Mediocrity. Arrived! But, ah, the monstrous cost! Behind him, the route lies thick with the ghosts of golden moments that might have been. Golden moments to which your idle fell ow attaches - wisely attaches - such vast importance. But the busy man has no time for these things, these things which bring no tangible results He has forgotten that to live, to love, and to

be cheerful is no less important than is the achievement of success. But is this success?-this horrible devotion to business, this restless, ceaseless urge to activity? I cannot think it is. The more time we apply to the accumulation of dollars, and to the poring over books in dusty studies, the less time is there for the making of friends ( friends, if you please; not business acquaintances) and the less time is there for the storing up of memories. Memories ! The true wealth, these and tax-exempt.

But let us glance for a moment at a few typical idlers. Idlers, that is, when measured by the six-inch rule of Modern Business. And idlers, remember, even by this standard ( the accepted one) are not chaps who sit in the sun and dream, but strange, curious folk who dissipate their energies in effort not destined to augment the bank balance. For example, there's Robert Louis Stevenson: truly an idle fellow; for years never earning a penny, juggling words, wearing outrageous clothing, running about the world on strange journeys (in canoes, with donkeys, on immigrant trains), utterly worthless, according to Bradstreet, until the last few years of a short life. And Samuel Johnson: lethargic; lazy; downright lazy; eternally turning over a new leaf; inefficient; digustingly inefficient; always hard put for money; living on the King's pension; wasting what he did get on worthless, unproductive dependents -a colossal idler. And Shelley and John Keats. What did they accomplish? Eddie Guest turns out more poems every year ( in addition to his lectures) than both of these fellows confected during their entire lifetimes. And there's Villon, Francois Villon, Prince of Idlers, gallow's meat, pick-purse, worthless fashioner of spicy ballads. What can History be thinking of to preserve his name through all these centuries? And Gustave Flaubert, a sadly unpractical chap, wasting seven valuable years contriving a book not one bit thicker than the monthly tomes of Robert W. Chambers. Inefficient, idle folks all. Squanderers of time and energy, deserving thoroughly, no doubt, the scorn of their successful contemporaries. And yet, when I come to consider these successful contemporaries, these solid citizens, these substantial, sleek merchants who scoffed at the awkward tenant of Bolt Court; these good, respectable folk who

wagged their heads ominously at mention of that "spoilt Stevenson boy" ; these fashionable brokers who piled up golden guineas while John Keats piled up golden rhymes on scraps of paper, and coughed, and coughed, and coughed when I consider all these lords of industry who scurried feverishly about in their harsh, strained fashion, while these idle fellows -these and others -merely dabbled in smiles, and heartbeats, and beauty, then am I confronted with an astounding fact. Where are they now, these busy, prosperous folk? History is silent. Fame knows them not. Time winks a roguish eye. Time knows. And so does Francois Villon know. Once he asked that question himself, this curious vagabond did, this elusive idler who, for half a millenium now, has dodged the sharp sycle of oblivion. And he will tell you where the serious gentlemen of the mart hold forth. "Gone," says Francis, "Gone, like the snows of yesteryear."

And now, to make an end, why all this pother? I can never contemplate the institutions of Modern Business and Industry and their heated followers that I am not reminded of Emerson's "Why So Hot, Little Man, Why So Hot '!" Why so hot indeed? Perhaps a few simple lectures in astronomy would help to reduce our present cosmic temperature. Please to fletcherize the following. From this little dab of dust ( the scene of these obscene hustlings) to that sun there in the heavens, stretch exactly ninetythree millions of miles. Ninety-three millions of man-size miles. And ninety-three millions of man-size miles equal just one single astronomical mile, this yardstick by which unhurried men measure the unmeasurable. And that bright star yonder, that little pinpoint of silver to the left of the Woolworth Tower, is something more than one billion astronomical miles from the lower end of Manhattan Island. Truly, as Stevenson says, 'tis a thought to freeze the mind.

And so, viewing our own ball of mud in the frigid light of far-off suns, there is much that can be said for the philosophy of a certain tent-maker who once lived in Naisapur and for jugs of wine, and books of verse, and songs sung low in a desert. Idle things, these idle, idle, idle. But sweet, Brother, ah, ineffably sweet.

A. JUDSON EVANS

Presidential candidates hardly furnish the proper picture for the inspiration for youth to become political Lochinvars. Even idealistic college professors who are as hopeful as anybody do not present our great men in a manner that makes them appeal like Beowulf, or even the "wily Odesseyus" of old. We hear that the "big brains" of the country will not even concern themselves with politics, unless paid by corporations to do so, and a young man born in an atmosphere where "patriotism" was the motif for many symphonies by southern type orators, looks long for a "William Pitt, the younger," to envy.

In fact, we of the young who study text-books on government are perhaps unfortunately not yearning for the presidency. And we ought to be to, because 100 per cent Americanism to the conof the appearance in this clime of John Smith and other sturdy trary, we don't want a million or even $100,000 in a satchel.

Back in 1907, when Virginians were celebrating the anniversary gentlemen, the North Carolina public schools were adopting new methods of copy-book writing, Columbia university pedagogy and real and fanciful history of the Old North State for the inspiration of the young that they might raise the State from its low place in educational standards. The same young had already learned to sing "Carolina, Carolina, Heaven's Blessings Attend Her." Anyone over four could murmur ". where the weak grow strong and the strong grow great. Here's to down home, the Old North State."

In this happy era young men recalled that Tarheels were second to none -"the salt of the earth," or in fine, "as-good-asyou - or-a-damsight -better." Ambition was a thing for a young man. Even in front of the vendome box ball alleys next to the Star Theatre, where the electric piano played "Steamboat Bill," it was legitimate to want to go to Congress when you grew up, instead of being satisfied with wanting to run a train engine. Statesville, a hamlet of about 5,000 then in the foothills of the Blue Ridge, was picking up, too. Woman's clubs, tarvia

streets and twenty-foot sidewalks were talked of ( they finally arrived, too). "Statesville, the best town in North Carolina" was the slogan. It had gotten so big nobody went to the station to see the trains come in. This was before sand clay roads, when you could still find an occasional Tarheel up around Asheville and the summer resort people did not all roll their R's or feel sorrow for the backward South and the down-trodden negro. At this time, before the ultimate triumph of these sand clay roads, the F. F. V.'s of Virginia still placed N. C. in the region of the great unwashed. All Tarheel excursions to the land of aristocracy meant was extra duty to the police of the Old Dominion, who had to haul many raucous citizens up the hill to the hoosgow to sober up. In this , epoch one might say: "Us High School girls taken a walk" and still remain a lady.

"First at Concord, farthest at Bethel and last at Appomattox," "Tar, pitch and turpentine" and the psychology of the underdog was banished. The U. D. C. and the D. A. R. marked historic spots, such as Fort Dobbs, where the Indians fought and little boys wanted to grow up and wear Jim swinger coats and be distinguished like Dick Hackett, handsome bachelor, who was elected to Congress.

But despite this background more inspirational than Dr. Frank Crane we have become more and more reconciled to the thought that we will never be President. This, after reflecting on the present campaign, breathing a silent prayer and looking at the picture of "Brother Charlie."

The secret of the sphinx, as discovered by Peer Gynt, is that he "is himself." The secret of Calvin Coolidge, the New England lawyer, is that he is silent.

Formerly in our history, a good crop of whiskers such as captivating Clarence wore to the six-day bicycle races, a frock coat and silence would insure a reputation for wisdom and dignity -so well grounded was the maxim: "Still waters run deep." But as George Ade has said, dignity received a body blow when the top hat went out.

One would hardly think, then, that in this good year of enlightenment the homely virtue gag of "silent Cal" would entrance the

folks in the hinterland, but to a certain extent, surely, it does. Mr. Coolidge's speeches seem to us, thus far, to be the tritest pieces of hokum which have been carried over the Associated Press wires since General Pershing's "It is with mingled emotions that we recall the pleasures and hardships together."

What sane, but ambitious young man could possibly want to emulate Coolidge? Truly, since W. L. Douglas died recently after pegging shoes at the age of seven, one has to return to Frank Merriwell for a worth-while hero.

Then there's ! !*/ §- ! Dawes, the purchasing agent of the A. E. F., who enjoyed Paree, while Owen Young figured out the famous "Dawes Plan," and who formerly enjoyed saying "Gosh" on occasions of high emotional stress, now isn't even allowed to "Damn the movie men" without Cyrus H. K. Curtis' papers changing it to "darn."

All Hell'n Maria has contributed to the long suffering republic, listening for a return of Patrick Henry's fire, is a few vivid word portraits of "Fighting Bob" La Follette, clad in a red shirt with the last words of Lenin tatooed across his heaving breast.

The constitution, not tampered with since the amendment which popularized corn whiskey, has been revived by Coolidge who read off a few paragraphs of the document as a political speech and admitted that he was willing to take the presidential oath. He seemed to want to show what a magnificent structure La Follette is plotting with the energetic Wheeler to blow up.

It would be tough not to have a constitution, for then there wouldn ' t be anything but the flag and the little red schoolhouse to make a speech about.

John W. Davis was not born in a log cabin and he has sinned to the extent of making a success of law practice. He has more education than is considered good form among the voters and he has had experience in international affairs - the latter fact making him a disciple of "chaos," because he might insist that the United States make some efforts to provide necessary foreign markets. He has made what are far and away the best speeches in the campaign, and, it seems to us, is as well qualified to be President as any good man who ever lucked it through a con-

vention. But he won't be nominated for that reason, even though the fact be generally conceded.

"People love us for our vices and hate us for our virtues" might apply to politics. The ideal is mediocrity, revered on Main Street and taught in the colleges, as a general thing.

"Fighting Bob" is supposed to be a hot radical. But it seems that he is at least sincere and he has a reputation for ability, and he would not leave the country if he were elected President. This, even though and because we don't believe he could accomplish anything radical in this land of luncheon clubs and prosperity. We like revolt, being a romanticist by nature, training and inheritance, but sad to say, no first-rate revolt has been staged in this country since the "younger generation" stepped out and landed a few good uppercuts in 1914.

-It will appear, then, that we are back on familiar ground and find that "the system" is still with us. What can any President do, more than any other President? Something, at least, if he is a man of some little force of intellect capable of wheedling Congress into action.

But will our candidate, the able ·gentleman from West Virginia, get elected? Our candidates seldom do and President Hibben and others are supporting him. That's the way to kill his chances. Anybody, the choice of men of intellect and experience, does not necessarily command a huge constituency. Who ever gave a darn, as Helen Maria might say, about what men qualified to judge have to say about the republic. Oh well, voila !

And so, we wouldn't be President. Even though we recall the patriotic urge prompted by the Old North State. Emerson remarked: "The President pays dearly for his White House," and the line was skipped over by three-fourths of the hard students delving therein.

We blush to say so, as Laurence Sterne puts it, but we simply couldn't be induced to run. This because we are supporting Andy Gump, anyway, and secondly, we never would have a ghost of a chance of polling any votes. Pretty soon we'll settle down under a liberal and conservative party system and our government will function without fuss, like the estimable British nation.

M. HARLAN

Squam Head with its scant settlement of a half dozen fishing shacks faced seaward from the mainland, high upon a windblown cliff. Below, a wide, clean beach stretched endlessly along the island edging the green, mottled waters of a northern sea. Ships rarely passed near the Head, but at times we could see, along the horizon to the south, the smoke and faint outline of a steamer going out from the cape. The clumsy dories of the fishermen who limited their catch to lobsters and shore fish, and the cat-boats of the summer people were the only craft with which we were intimately acquainted. In summer the days were long and of brilliant clearness save for a few weeks of dense depressing fog. It was in the evening of such a foggy day, that with the last of daylight, that a small schooner slipped alongside the Head and anchored. All night its one light glimmered through the fog, arousing the curiosity of those ashore.

In the morning two of the crew came ashore; an old brutal sailor with small cruel eyes and a yellow, tobacco-stained moustach, framing broken teeth, and a Portuguese boy, very young and half shy, with half curious eyes, barefooted, his trousers rolled above his knees, and wearing a faded blue shirt open at the throat. He seemed almost a .s:hild, a mistreated child, fearful, yet with an air of stubborn courage. As the dory ground the beach the sailor jumped out and walked with an almost insolent swagger towards the boys who had hurried to the beach as soon as the dory put off from the boat. "One of you kids think you could get us some newspapers and soap?" he asked. Some of us ran to get them.

"That there schooner," he explained to the increasing group of boys and the few girls who hung on the outside of the circle, wide eyed and fearful. "I'm captain. Gotta anchor here for the fog to rise 'fore we put on out to the banks."

The newspapers and soap were but excuses to idle away the day on the beach, spinning yarns. Strange were the stories he told, sitting there with a pipe clenched in his teeth, enjoying to the full his ability to draw envious glances from the small boys and excited shudders from the girls. There was nothing in his personality which drew the children to him in friendliness, only a sinister fascination, from why they sometimes drew away in fear.

Some of us older boys, tiring of the man's yarns, turned to the Portuguese lad, who was eager to talk in his poor broken English. We liked him at once, his quick flashing smile, the manner he had of raising his eyebrows at the end of a sentence as if to ask our approval. I asked him how he liked the boat and the captain. At this his face clouded with a look of hatred and almost of fear. He was the youngest of the crew, barely eighteen, and a sort of cabin boy to the captain. It must have been a lonely life for him, for he was all eagerness to get back to Portugal. There was a girl there, he told me, a wonderful girl with hair black as the night of a fog. He had a fine picture of her which -he would show me. When he got back to Portugal he was going to leave the captain and the schooner, and marry her. "If," he added, his face dark with hatred and fear, "if a day finds me there alive." I soon saw that there was some strange bitter feeling between the boy and the captain, but he would say nothing to my questions except to express his loathing for the man.

About noon, when the sailor rose to go, the boy asked me to go with him to the boat. He would show me the picture. Although not caring greatly to see it, I wanted to see the schooner. As we rowed out the captain was polite to me, but to the boy, he was curtly insolent. I longed to find out what was between them, but the boy was deaf to all questioning and only said that he hated the boat, the captain, and the whole crew, and he admitted that he was afraid of them all. The boat was something of a disappointment to me, for it was only an ordinary fishing schooner, smelling vilely of fish, and dirty to a most indecent degree.

The crew lounged about on deck. And I saw their faces form into sneers when they met the glances of the boy. It was, evidently, not the captain alone who hated him. I wondered what they could have against him, what he could have done to arouse their animosity. Had he exposed them in some crime or thwarted their purpose of smuggling? My mind formed a hundred solutions in which I could not bring myself to believe the boy in fault.

We had our noon meal in the close cabin of the schooner. It was not badly cooked and better than I had expected from the appearance of the place. The crew talked pleasantly to me, revealing little of their course and purpose, but they said not a word to the boy except through their eyes which spoke a thousand hates. It made me shudder to watch their glances. I didn't blame the boy for hating them. Then I told myself that I was working upon my imagination.

After the meal we left the captain asleep on deck and started for shore. When we were well out, he drew the picture from his shirt and handed it to me. I wondered why he had got it secretly and hidden it from the crew. Was it then something about the girl that aroused their evil looks? The picture was about six inches long, a well done oil portrait of a sweet face of only ordinary beauty, mounted in a fine gold frame. It was not the kind of a portrait which a sailor usually carries. Wondering that a poor boy should have it, I asked him where he had got such a finely worked portrait. At this ( did I but imagine it?) the look of fear returned to his face and he would not respond. I praised her beauty, at which he was much pleased. He refused to stay ashore. The fog was !if ting and they would soon be going, he said. So I wished him well on his way and a happy life with the girl of the portrait.

As I walked home, I resolved to tell my father about it, and to ask his advice as to whether something ought not to be done to help the boy, that was if he really needed help. My father listened to my story with no surprise, and assured me that I had probably imagined most of it. How little we look for crime

in everyday life? In our smug days the misuse of a cabin boy does not develop into crime. Things like that belong to the days of Stevenson. So I watched the boat put out, in a straight course, to sea.

Two days later a sailor's chest was washed ashore. It was a grey weather-beaten box. The top had once been painted blue, but was now pealed and worn. The handles were of rope, the hinges and lock were greatly rusted. When we broke it open we found some clothes, a rosary, and in the bottom, wrapped in a faded blue shirt, was the portrait of the boy's sweetheart.

w. E. SLAUGHTER

The first rays of the early September sun flickered across the peak of Mount Ararat, leaped over the Euphrates, and forced their way through the crevices in the thatched roof of a dilapidated cottage, where the brilliant shafts pierced the gloom of the room beneath. One, more playful than the others, found the bearded face and open mouth of a snoring, slumbering form. As though irritated by this annoyance, and his dreams disturbed, the man heaved a mighty sigh, stretched his long arms, and glanced over to the silent form in the other twin bed.

"Hey, Maw, dernit, is it time to git up yit ?"

The rising sun found its opportunity to shoot a stream of light upon this other bed just then, exposing the form of a large, middleaged woman. The covers had been kicked to the floor in her restless sleep, leaving a dirty sheepskin nightie as her only protection. At the untimely interruption to her slumbers, she slowly opened her eyes.

"What's the big idea of waking me up so early, Noah? Pipe down and let me sleep."

"Well, it's time to git up, I tell ye. There's the clock striking . " six now.

"Oh, dear me, I do believe the nights are getting shorter," sleepily mused Mrs. Noah.

"For Heaven's sake, Maw! Where's yer modesty? Suppose the kids should come in here. Dernit, pull 'em covers over ye!"

"Well, of all the men! Noah, I do believe you're getting old."

"Old? Who's old? Say! What day is today?"

"You're closer to the calendar, look at it yourself," retorted his loving wife, turning over in her bed for another nap.

"Hey, Maw, dernit, today's my birthday. Yessir, today's the sixth day of the seventh moon of the year 3524 B. C., if old Ussher is right. Four hundred and eighty years old! Gosh!"

With these ejaculations he persuaded himself to leave his bed and slip on his red robe.

"Maw, ain't ye ever gonna git up? I'm going down and wake up the boys and have a little game of Mah Jongg before breakfast," he said, as he walked out the narrow door, leaving Mrs Noah reaching for her mirror and complexion clay.

The three boys, already awake, were lying in bed telling jokes when Noah walked into the room.

"Aw, no! Pop. Let's get out the Ouija board this morning instead of that Chink game," objected little Japheth, the youngest of the trio. "We've played with those ivories every morning this week." Shem and Ham supported their brother in this idea and the old man yielded.

So it happened that when Mrs. N oali climbed down the ladder some time later she found the four very, very quiet and serious, leaning over the mystic board. Shem was taking down some figures and words that the little table was spelling.

"The end of all earth is come.

Make thee an ark of gopher wood 625 feet long, 105 feet broad and 65 feet deep " and so on. It was a long list of instructions.

Suddenly the little table stopped and Noah looked up. His face was whiter than his long beard and his hands trembled. In awed tones he related to his wife the rev .elation of the coming flood. The news of the impending cataclysm was spread around the village before Mrs. Noah had the percolator warmed.

It was twenty-three years later that the first difficulties were encountered. The men employed to build the massive ark were quarreling among themselves.

"This is a big job we're doing, and it's useless. Where is that old fool Noah going to find enough water to float this thing? How's he going to get it down to the water if he finds enough? We ought to strike for more money or shorter hours or something. We haven't struck for three months." Such was the summary of the contention.

So at four by the clock one afternoon forty-seven hammers were dropped to the ground and forty-seven men clambered down the skeleton of the great ship. Noah was being examined for more life insurance at the time. When he returned to the scene of the construction work he found only the foreman of the job and the contractor.

"Say, what's this mean? Where's everybody, anyway?"

"Noah, old boy, we're sorry, but the men have gone on a strike for a five-hour day."

"But they can't do that, dernit. I've gotto have this ark finished by 3644 B. C. or we'll be drowned."

"Oh, dry up that stuff about the flood. There ain't never been such thing happened before, or how can there ever be?" reasoned the foreman.

"Well, who's paying for this job?" retorted Noah. men back and I'll pay 'em two sheckels a day more. give them each a thousand if they get through the job Dernit, now I'll have to mortgage the old homestead. have more money."

"Git the And I'll on time. I gotta

Under such generous inducements the work was once more resumed, and every succeeding day saw the ark nearer completion.

Serious matters occupied the minds of the other members of the family. Shem was having trouble with his end of the work. Noah encountered his oldest son one morning pacing the floor and tearing his hair.

"What's eating you, Shem, my son?" asked the fond father.

"Oy, Pop, the railroads have an embargo on giraffs and that pair we're importing for this flood are held up. Then, those two pedigreed tuberculosis germs got mixed up with a lot of pneumonia bacteria and I can't separate them."

Old age is not so easily excited as youth. "Well, stop this running around and do something. Send for some more and destroy what you've got," directed Noah. "We've gotta have a

complete outfit to start this world over again when the flood's over. What's Japheth gonna do with this doctor's degree of his if he doesn't have any sickness to work on?"

J apheth, also, seemed burdened with difficulties. He had been appointed commissary of the coming expedition. Elephant food was scarce. The brokers in Egypt had a corner on rye, and a shredded wheat shipment had become lost. A supply of medical appliances was needed for the long voyage, as well as ointments and cosmetics. He hailed Noah one day as the old man passed by the little office.

"Hed, Dad , where did you say to order those Cascarets? The Vick's Salve came in yesterday, but they won't ship any Aunt Jemima's Pancake Flour unless we pay them in advance. And, say , what do goldfish eat? Gosh! Dad, this is an awful job you g ave me."

"Jap, my child, you must maintain your natural composure. You know what happened to Goliath when he lost his head, don't you? Send out more want ads. Put a full page in the Saturday Ev ening Post. We'll spend every sheckel I've got to equip this trip."

Ham, too, was in a broiling situation. He was in charge of the household affairs. The women wanted to take more things with them than the ark would hold. Noah found him in a warm argument with Shem's wife one evening.

"Pop , this woman wants to take the electric piano with us. How in the dickens can we do it? Maw wants to get a new brass bed in case company comes. Can you beat it? Those life preservers all had holes in them so I sent them back, and I can't get a high chair for the baby. Gee! I can't get any co-operation."

"Don't mind the women, son. Never argue with them; they don't know any better. Come on down the street and get a dope."

The ark neared completion. Crowds of people came to view the wonderful spectacle and to scoff at poor Noah. Such a catastrophe as he prophesied had never happened before and could not be conceived of by the sinful multitudes. What was the old fogey talking about? His wife said little. She was doubtful at

times whether to believe the man she had lived with for four hundred years or to listen to the assertions of the neighbors that he had lost his mind. But didn't the Ouija board say it would happen? It never makes mistakes. So the family stuck together.

One hundred and twenty years passed. The time had come. Two weeks before the threatened storm was due Noah had collected his menagerie. Everything was put into the ark that the ship could possibly hold. The milkman was told to leave no more bottles and the rat traps were re-set. Mrs. Noah was closing and locking the doors and windows and the three young wives were dressing the babies when the first drops came. Immediately Noah's faith jumped above par and the shorts sought cover. The old man rushed for the ark yelling for the others to follow. It was not until the great door was closed and bolted did the old man find that his wife was mis sing.

"Hey, Ham, Shem, Japheth ! Where's Maw? Look around quick and see if we left her out. Dernit, where'd she git to, anyway?"

A hasty search failed to find Mrs. Noah. The great doors were once more opened and Noah stepped out into the heavy rain. He walked up to the bow of the great ark and looked across the muddy field to his old house. There on the porch was Mrs. Noah weeping and surrounded by several women. Noah became angry.

"Ahoy, there , Maw! Come on her, will ye? Dernit , can't ye see it's raining?"

"Oh, Noah, dear, I can't come away and leave the old homestead. I can't. I can ' t leave the old place where we two have lived so happily for over four hundred years. Oh, I can't do it! I can't !" wailed back the good woman.

The old man lost his patience. "Hey, Sham, go out there and bring your mother in . Dernit, I'm gettin' soaked to my skin. Hurry up!"

Shem reached the porch in spite of the mass of mud, and pleaded with his mother to hurry over to the ark. But she would not be persuaded.

"Shem, dear boy, would you have me leave all these things we worked so hard to get, stinted and saved, me and Paw? See, here's your picture when you were wee small. There's the old hen that laid so many eggs. There's the fireless cooker we just got after waiting so many years. Oh! don't let us leave."

Shem was a good son and loved his mother. He hurried back to his father, who was pacing the deck in his rage.

"By golly, I'll get her myself. Dernit ! We gotta eat on this trip, and she's the only good cook in the family."

With that he leaped over the side of the boat and hastened over to his faithless wife. Noah was a large man.

"Now don't offer no resistance, Maw. You gotta come," he said as he grabbed her around the waist and carried her off. The sons helped hoist her on board and Noah climbed after. They could hear the rain come ·down like a mighty sheet of water when they had again fastened the door.

Inside all was not peaceful. A cry of warning suddenly came from the front hold.

"Look, quick, the poodle's scratching! Don't let him kill that fl.ea; it's a pedigree," yelled Noah. He jumped up excitedly from his stool and struck his head against a rafter. Just then little Ham Junior grabbed hold of a wasp

(Writer's Note: This is as far as my records go.)

GEORGE R. FREEDLEY

Stark heat stridently sweeping through silent pathways of faded ,light is a mad thing that makes streets shudder and run helterskelter among the black cries of the night .

JEAN McCARTY

. For over a year I hadn't had a piano. All my music lay packed away in a storage house. This, to me, was far from a well furnished , comfortable house and be happy without a piano. A house seem empty in spite of elegant furnishings if in some room there is not a piano.

I often thought of some old tune and wished to rush to the piano. If I went to a concert I came back with the airs tumbling over each other in my head. I looked at the program, and knew in just what book to find each number, but alas all the books of music were hopelessly out of my reach. This was surely provoking.

One day I moved into a new house and found my instrument standing against a wall of a so£t yellow tint. The mahogany shone softly with a welcoming gleam, while the ivory keys beckoned me. I quickly drew out some music from the case, and sat down on the piano bench.

I first tried Sinding's "Rustle of Spring." The ripply triplets sounded wonderfully sweet. All the joy and rapture of spring bubbles forth in this piece. The piano was as full and melodious in tone as ever . It was so delightful to have it again. Piece after piece of old music I played. Every one was like an old friend, whom I had met after long separation. I had the same sensation that I have when I haven't seen somebody in a long time. It is a little difficult to get close to her again. You have to feel your way, because you've both changed a little. With each piece I had to become acquainted, although I was already familiar with it. These old "friends" must have felt rather resentful because my fingers had forgotten to manipulate their little intricacies. I felt like apologizing to the piano for making it utter such discordant sounds at times, when I knew it was longing to show its beauty of tone.

Each piece sounded new, yet familiar, and lovelier than ever before. It had grown in meaning and expression. I noticed

exquisite harmonies that I had never heard before. It was exactly as if I had met a person with whom I was very familiar, and yet was taken by surprise. Just such a thing happened to me recently. I passed by an awninged porch, and saw a lady whom I had not seen for many months. I remembered that she had very blue eyes, but when I saw her eyes glowing there in that shaded porch I was startled. They were bluer and deeper than I had ever imagined.

I was just beginning to feel more at ease with my "friends" when I happened across the "Dragon Fly," which is one of my most fascinating loves. It is such a whimsical, wayward little composition, just as its name tells. It is light and delicate as the dragon fly' s wings, and you can almo st see their transparence. In the bizarre little treble notes you hear the dragon fly buzzing joyously higher, higher in the summer heat, until he rests on one note, fluttering through several measures, then he is off again, flitting, buzzing -abruptly he whizzes -up-down then upand the piece is ended.

Each piece of music will conjure up a place or scene for you. This same "Dragon Fly" brings my last music master back to me. I see his tall form bending over his grand piano in a tremendous studio. The sunshine of spring in Texas drifts in golden flood through the French windows. A breeze brings the scent of a Texas garden and the chirping of birds. The master plays the "Dragon Fly" with his great strong hands, which produce the most delicate sounds.

When I hear "Thais" I think of a lovely pageant I saw given on a lawn late in the afternon of a midsummer day. The pageant told the story of Alcestis and Admetus. Every time the beautiful blond Alcestis appeared in her chariot the sad, weirdly sweet notes of "Thais" filled the air ; as though poured from her heart. Slowly she waved farewell to the prostrate Admetus as she was borne away to the lower world. Softly, smoothly floated the melody of "Thais."

In burst Hercules with the crashing chords of Chopin's "Third Polonaise." Then came his mighty battle with death. Pluto

remained obdurate until Mercury, clad in flaming red, leapt through the air until he remained poised before Pluto. Mercury, with arm raised in graceful salute, declared the will of Jupiter. Death was overcome.

Joyfully, yet with subtle sadness, flowed the strains of "Thais." Alcestis, pale and beautiful as a moonbeam, was borne in her snow-white chariot into the faint golden sunshine of a late summer afternoon. This time she waved in greeting to Admetus. Mournfully and excruciatingly sweet poured out the morendo strains of "Thais."

Music is ever fresh. These old pieces had not lost one bit of flavor in all the time of their obscurity. It is possible to play a piece every day withoµt feeling weary or bored. In this way music is greater than books. If it were possible to read a book every day, even though it were an admirable book and one of your favorites, you would soon wish never to see it again. A piece of music ever delights your senses and grows in beauty.

I think that a meeting with an old friend does not exhilerate you as playing after an absence from a piano. You feel so hot and happy that you become utterly weary. I played and played, afraid to stop and lose the ecstasy. At last, however, I dusted the keys, and softly closed the lid. I turned out the light and longed for tomorrow so that I could begin all over again. As I went out of the room I looked back. The dark mahogany of the piano gleamed softly in the moonlight.

<!&ur<!&pal

Little cold blue dancing lake

Sparkling in the autumn sun

Like a cold blue opal takes All the shadings leaves have run. Here a scarlet flash of maple Blood-red glows in every ripple, Falling acorns have begun.

Gloomy pines with deep green shadow

Mingle with the sycamore. Fore st green and golden yellow Glorious blendings by the score. Wide-branched beech his silvering head Bending o'er this lucid spread Summer's glory doth deplore.

Gentle tiny sky-blue lake

Sparkling in autumnal beam.

A million jewels I would not tal,e Precious treasures though they seem Not to see your colors shimmer As the trees their shadows glimmer In your opalescent stream.

-W.H.S.

The silver voice soared up, up, till Ivor felt that it must touch the shining edge of Venus. He lay his tired head on the windowsill and, looking up at the myriad stars, blinking and winking in the night sky, he let the ra v ishing harmonies of the song steep his soul. Now she was singing an aira from a famous opera. "O, Caro Mio," trilled the voice. It came from an open window in the small brick boarding house, directly across the street from the house where Ivor McAnnaly boarded. The street was very quiet at night, and Ivor could hear the tones of the invisible singer as well as if they had been in the same room. Below on the sidewalk a child shrieked as she danced after a firefly, and the sound drowned the song. Then "O, Caro Mio," rose the voice, swelling passionately. The full rich "O" sound floated on the air, and, growing softer and softer, died away.

Ivor sighed, got up slowly and lighted the gas above the fireplace. The bluish-white light leaped up, revealing the bare plaster walls of a small room, the cot near the window, imitation oak bureau and rocker, and glittered on the brightly polished silver of a large saxophone hanging on its own special peg on the wall. He looked at his watch: ten minutes past mne. "Time to go," thought Ivor, and pulled off his collar.

The whanging, banging thunder of a jazz band in full swing, the growing, moaning notes of a saxophone, and the dancers' voices lifted spontaneously in the words of the latest popular song, "Whose Izzy Is He?" they wailed ; "Is He Yours or Is He Mine?" Her laughing partner raced a brunette in a scarlet dress down the length of the ball room. A peroxide blond flapper in grass gre~n and a fish-eyed cake-eater, totally absorbed in regarding each other, stood stock stil1, occasionally swaying absent-mindedly in time to the moaning saxophone. Scarlet, vermilion, cnmson,

peacock-blue and almond green, lemon yellow and burnt-orangethe splotches of color whirled here and there, like the bits of glass in a kaleidoscope.

The number came to its "Shave and a Hair Cut, Bum, Bum!" close, and the saxophone player wiped his handsome brow. He was a good-looking chap; this Ivor McAnnaly.

"Good crowd," he shouted to the first violin above the noise of the hand clapping. "Liked that one, huh? Don't blame 'em. 'S snappy piece. Say, is Babbs signalling for encore?"

With a mighty crash the "Royal Twelve" orchestra sailed into the encore. In the midst of his solo, Ivor started and nearly missed a note. There she was again - the primrose girl. Tall, slim, with skin as fair as dawn, and hair as black as night, in a primrose gown, as usual, she floated past him, and her blue eyes seem to flash in recognition as they met his. It was the third Saturday night he had seen her - obviously she was a member of the club. And with the same man - but, oh heck, he didn't care; he just liked to look at her.

Several hours later, Ivor pushed his cot nearer the window, so that he could see the stars, and tumbled into its downy embrace. There was a fragrant tulip tree outside his window, whose branches almost touched the sill. Above its somber outline the midnight sky was peppered with multitudinous sparkles. He thought of the voice across the way.

"What's that line of Tennyson's?" he said to himself. " 'A voice that shivered' - that's not right-'a cry' - yeah, a cry, 'that shivered to the tingling stars.' That's it, good that is - well, it's not a cry, but a voice Doesn't shiver exactly, but it does seem to reach the stars." That made him think of his mother. She had had one of those silvery lyric sopranos. "Gosh, she could sing 'Bonnie Sweet Bessie' !" His mother was a concert singer in her youth, and well on the road to fame, but she gave up her career for her husband and children. Ivor almost thought he could hear her singing to him -very softly, as she used to do at twilight, "Bonnie Sweet Bessie, the Pride of Kaildair." It had been her favorite song, a simple Scotch ballad, that reminded her

of her birthplace. "I wish she would sing it," thought Ivor, meaning his neighbor, and then an idea entered his head. After a few minutes' thought, he grinned to himself, gave a farewell blink at the Milky Way, and went to sleep. But not, however, before he had thought of the primrose girl; indeed, it was his habit to think of her once or twice before going to sleep.

When a few dusky orange bars lingered in the west of the purple sky next evening, the voice was again lifted in song. At first it trilled like a happy bird, and darted up and down innumerable scales like a stream bubbling over stones. Then unexpectedly it slipped into the rich tones of "O Patria Mea." The voice sang many songs, from that first great aria from Aida to the delicately melancholy "Last Rose of Summer." Ivor knew them all-his mother had taught him arias, and sung him the greatest of the world's songs since he was old enough to lisp a dozen words. When the last note had died away, Ivor took down his saxophone, and sitting on the edge of his cot, he began to play "Bonnie Sweet Bessie." He fancied she was singing under her breath at first, for half way down the first verse, the words broke out, as if they would not be repressed. Through the chorus and the next verse they we_ntin full swing. After a moment's pause, Ivor swung into the catchy waltz strains of "A Kiss in the Dark" and she followed unhesitatingly. "Hum; pretty good," thought Ivor, "new jazz -old ballads -arias from all the operas."

Ivor came to look forward to the twilight hour every night when sometimes he played for her. They never failed to give "Bonnie Sweet Bessie"; it was their favorite "Funny thing to sing with this saxie," he used to laugh to himself sometimes"Wonder what she thinks of it?" At any rate, for Ivor it was a peaceful hour sandwiched between the busy rush of the office where he was employed, and the tempestuous whirl of the jazzsaturated evenings when the "Royal Twelve" were playing.

One off night when the jazz hounds were practicing, Babbs, the director, fingering a pile of new music, announced, "Say, boys, here's a good one. Ever hear that old song, 'Bonnie Sweet Bessie'? Goes like this" -and he hummed a few lines -"tum

yum de dum -'of Bonnie Sweet Bessie, the pride of Kaildair.' Well, Merrill's jazzed it. I heard the 'Century's' playing it today and it's a knock out. Come on, let's try it."

The following Saturday morning was brightly beautiful. Ivor sang blithely to himself as he dressed -funny how "Bonnie Sweet Bessie" rose to his lips. Ivor was always happy on Saturdays, for one thing, ( or maybe everything) the primrose girl would be at the dance. At eight-thirty Ivor was running down the steps and out the front door, giving it a vigorous slam that resounded loudly. He looked at the second-story window of the house across the street, in the hope, almost vain he knew, that it might see the owner of the silver voice. Just at that moment, a white arm pushed open the blinds and tossed outsomething yellow which fluttered to the pavement. Ivor cross the street eagerly and picked it up. It was a primrose.

That night the primrose girl came early, and she was more bewitching than ever. Her slim ankles flew as if they had borrowed Hermes' winged sandals, and as she flitted past, Ivor was sure she smiled at him.

Babbs was called to the phone after one of the dances. As they were waiting for his return, Ivor, who was watching her as usual, saw the primrose girl write something on a slip of paper, which she gave to one of the club attendants. A moment later, Ivor looked up from his scruting of her to find the waiter holding out the slip to him. Unfolding it he read a request that they would play "Bonnie Sweet Bessie." He glanced up to find the primrose girl regarding him. He smiled and bowed, and she nodded smilingly back. Ivor thrilled; there seemed some intangible bond between them, some calling of soul to soul.

When Babbs returned, they played "Bonnie Sweet Bessie" and the primrose girl danced blithely, singing as she swayed lightly to the melody.

When the "Royal Twelve" came back after the intermission, Babbs, having had several drinks, became quite communicative. Ivor, who sat at the director's le£t, listened with but one ear, though he was the person addressed.

"See that flapper in green, Mac?" Babbs was babbling to him. "She goes to every dance in town. See her 'fore, haven't you? She's at all of 'em. So's that red-headed woman yonder. Now there goes what I call pretty -there in that queer shade of yellow."

Ivor, looking carelessly where Babbs indicated, was startled to eager interest when he saw that his primrose girl was the topic of discussion.

"Well, what 'bout her?" he demanded gruffly.

"Nothing 'tall, special -just extra good looking. Lives in same apartment with my sister. She and that skinny fellow been married 'bout a month. Still going to dances strong. They'll quit soon -they all do."

* * * * * * *

Venus was blazing steadily above the black tulip tree as Ivor lay his tired head upon the window-sill. The dance was over; the dream of the primrose girl was ended. He might not have been so unhappy, but something whispered to him that the silvery voice would never sing again for him. He couldn't help believing it was the silvery voice that was married to the skinny man and lived in Babbs' sister's apartment. But the stars seemed to wink at him as if they knew some delightful secret. Then softly, softly, as if it knew it should be asleep at such an hour, and silvery as a far-off fairy bell, the voice rost liltingly :

"Oh, bonnie sweet Bessie, the pride of Kildair."

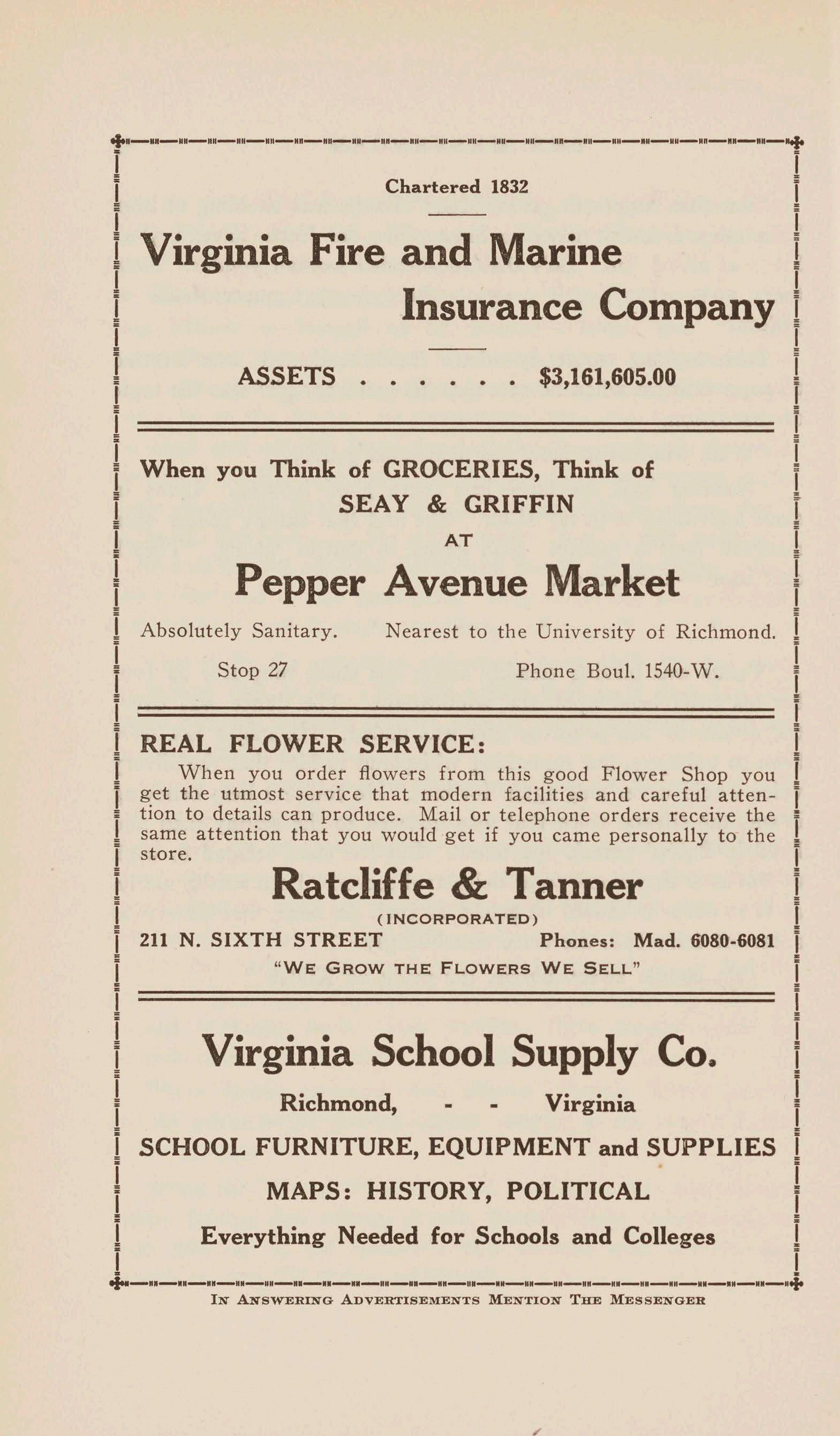

Absolutely Sanitary. Nearest to the University of Richmond. Stop 27 Phone Bou!. 1540-W.

When you order flowers from this good Flower Shop you get the utmost service that modern facilities and careful attention to details can produce. Mail or telephone orders receive the same attention that you would get if you came personally to the store.