CampusWriting

By MABEL LEIGH ROOKE

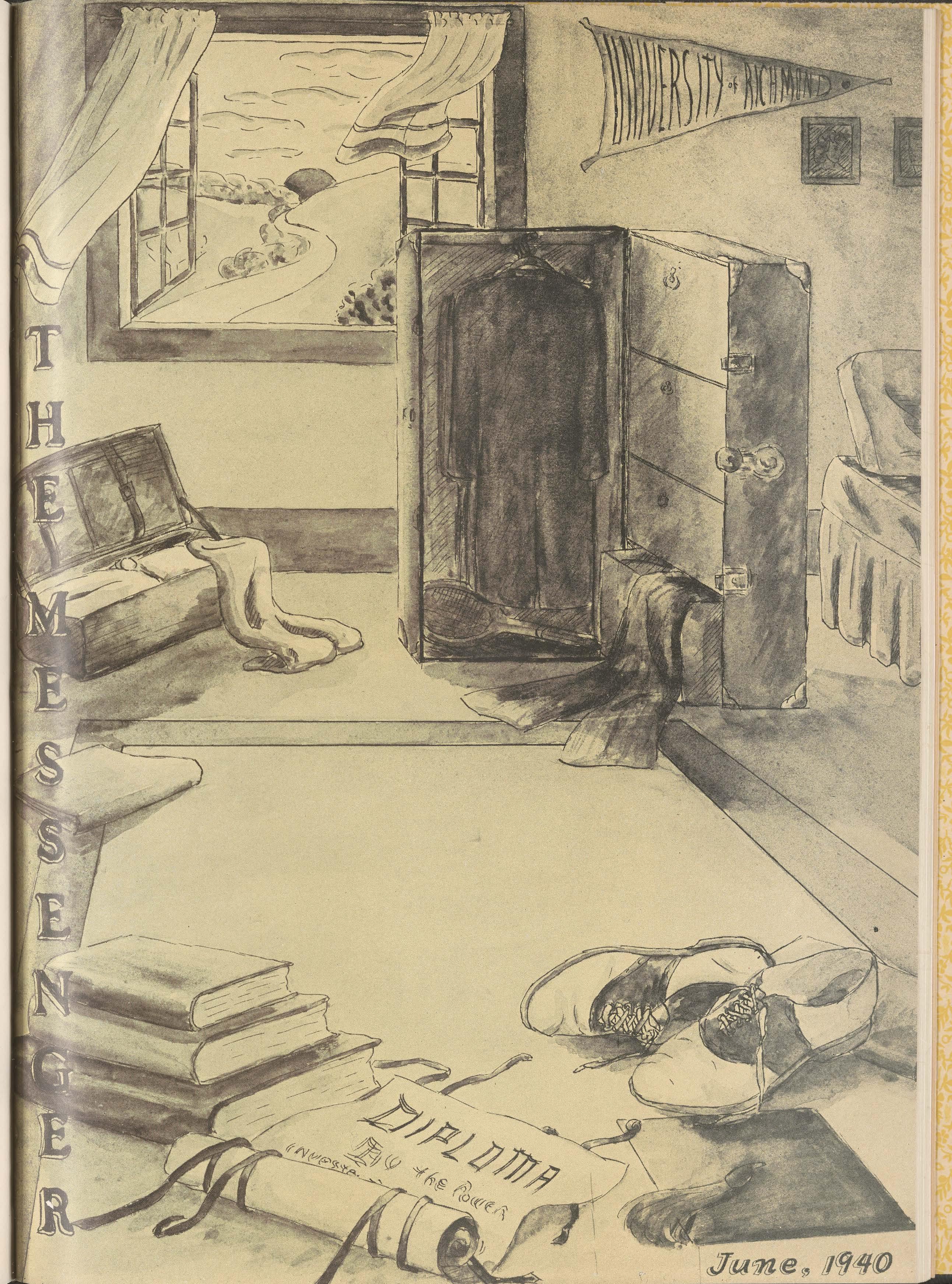

We live in a world dominated by the press and the radio-one in which the dissemination of ideas and opinions holds tremendous influence in our thoughts. The campus has been all too unaware of the importance and of the tremendous possibilities of literary production.

THE MESSENGERshould serve the purpose of stimulating writing-stimulating it in such a way as to produce not necessarily quantity, but a well flavored quality. However, it is not an untrue corollary that the quality is most often an outgrowth of quantity. If one would write, he must write; and this trite expression is, none the less, true. There is an interest in writing here, undeniably so, but its passivity has been such that this interest produced no tangible evidence of itself and, therefore, diminished noticeably. Recognizing these facts, we have sought during the past year new ways of accomplishing our goal-a larger volume of creative writing and its natural resultantricher thoughts in a more developed literary style and in a more perfected technique.

We have felt that there are several contributing factors to the dearth of campus literature. One has been that there is no definitely

established class in original writing at Westhampton. Academically, it has not received a recognition comparable to its importance, and its lack of stability as a course may well affect the general attitude. For several years, previous to the current one, there has been no Writers Club at Westhampton, but this was remedied during the year by the revival of the old club, and Richmond College does have its several literary societies. What are these groups doing? How constructively active are they? They, cooperating with the literary magazine, could serve to key the campus to a creative spirit, their active interest stimulating others in literary growth. The prestige of writers is desirable; the pride in achievement is worthwhile.

The Board of Publications promises the campus five issues of THE MESSENGERduring each academic year. The staff is ready to fulfill this obligation, but it cannot work alone. From the 1,050 members of the student body there must come the material with which to fill those thirty pages for each issue. We, and the campus as a whole, are dependent upon the literary creativeness of those who have the ability to express themselves in writing. With that we recognize, as we have said before, that, if THE MESSENGER is to exist, it must do so on its literary merit. Here the responsibility of the entire campus is involved. The student interest must be constantly increasing, with a friendly competition among the writers in seeking publication, and an increasing campus ability to read critically.

Again we reiterate, the campus will get the magazine it wishes in entertainment and in information. The more critical are you, the readers, the more critical will be your editors.

By JEANNE HUFFMAN

II am not a puppeteer, nor am I a person who has observed from the audience point of view very long; but I am impressed with the significance of the art synthesis found in puppetry, and I have discovered that the investigation I have recently made of their history is interesting to other people also. In this historical sketch that follows, I have not treated separately the various types of puppets - hand puppets, marionettes, finger puppets, shadow figures, rod puppets, and cardboard figuresbut have considered the development chronologically under the general term puppet, which is given to all animated theatrical figures manipulated by human control.

Cyril Beaumont tells us that future historians of the development of the theatre in the twentieth century will record at least two great influences of particular interest: one is the extraordinary popularity of the Ballet, and the other, the Renaissance of Puppetry

II

The exact origin of the puppet is not traceable. However, it is known that the roots of its family tree lie deep in the life of ancient

Egypt, India, Greece, and Italy. Also it is known that its great trunk springs from the soil of Europe and the Orient, and that its branches spread over to America

Max Von Boehn in his book entitled Dolls and Ptt ppets gives us his concept of the origin of the puppet-show. He says: "The child that occupies itself with its doll is playing, without knowing or desiring it, at a theatre; and thereby is poetically and dramatically active. It puts itself in the place of the doll; it is artist and public in one person; it creates the object of art and appreciates it at one and the same time. Herein lies the basis of the puppet theatre; for the first child who played with its doll as if it were a living being, may be regarded as the originator of the marionette stage. When and where this happened, we naturally do not

know; even as little as we know where and at what period adults first perceived this tendency of the child's mind arid created an art form out of its naive play." Nor is it known exactly when, although it was necessarily in very ancient times, the distinction was made between the doll and the puppet.

In the opinion of Winifred Mills and Louise Dunn the puppet had its beginning long, long ago in Egypt, because there have been found there small carved figures of wood and ivory with limbs that could be made to move by the pulling of strings For what use these figures were intended is not known. They may have been the first dolls in the world, or they may have been images of the gods which they worshipped. However, it is known that they were treasured and were buried with the kings and queens in their tombs along the Nile. Some scholars say that the large idols in the Egyptian temples were puppets, and that the priests, concealing themselves inside them, could make them move their hands and open their mouths. This so amazed the spectators that they fell down and worshipped them.

Proof that the Egyptians had miniature puppet-stages has also been found. One has been unearthed which has doors of ivory with the rods and wires still in their places.

Other authorities, especially the theatre authority, Richard Fischel, say that the home of the puppet-show is in India. From there it is supposed to have gone to Persia, and then to have reached Europe by way of the Arabs. Against this theory, other students argue that proofs of the existence of the puppet-show in ancient Greece carry us back to very much earlier times. Consequently, they say, India can hardly assume the credit of the origin.

" So far as the modern world is concerned," says Cyril Beaumont, "there is little doubt that the puppet was born in Italy and introduced to neighboring countries by travelling Italian showmen, whose puppet performances

were afterwards imitated and adapted to suit national tastes." He adds that the term puppet il; derived from the Italian word pupa, meaning a doll.

Regardless of the exact date and place of origin of the puppet, whether it be Egypt, India, Greece, or Italy, we do know that the puppet is as old as civilization itself. It is unfortunate that there are no direct Egyptian records of puppets. There are, however, numerous references in the works of such classical writers as Aristotle, Plato, Horace, Xenophon, and Socrates to figures worked by the pulling of strings.

III

While there are several countries that claim the origin of puppetry, there are numerous ancient companies in many other countries which together can be called the trunk of the family tree.

In Spain puppetry can be traced back to ecclesiastic ceremonies in churches and monasteries. Later, the puppets were aided in their movements by very intricate internal mechanisms; they thereupon became very popular and were soon adopted by the popular titeneros, or showmen, and thereafter were found in all public places, in cities, villages, fairs, even at court. In the Spanish section of Los Angeles today there is a public marionette theatre.

Perhaps the most interesting and unique of all puppets were those of the Orient; for they were as originally worked out as were all the arts of the Eastern peoples. There was capricious imagery displayed in their conception; infinite detailed skill and artistry in their creation; and endless, disciplined training in their manipulation, such as three years devoted to the operation of one arm. These operators of the Bunraku made a life profession of this work.

Probably the most weird and fascinating [ 6 J

of these unusual figures were the Javanese shadow figures. They were grotesque forms with long, lean, beckoning arms and incredible profiles, adorned with curious, elaborate ornamentation. They were supported and manipulated by fragile, graceful rods of bamboo.

In China the art of the shadow play long, long ago attained a degree of perfection as high, if not surpassing that of any other country . The Chinese marionettes were also very skillfully and quaintly designed, but never surpassed the beauty of the shadows. These shadows were famous for their range of subject and variety of appeal. The figures were made of translucent hide, stained with great delicacy . The colors glowed like jewels when the light shown through them, and the combination of these colors was amazingly beautiful.

In Japanese literature one finds the antiquity of the puppet-show traced back into the depths of the ages; and it is found that Japan has developed a marionette tradition altogether and amazingly unique. Indeed so powerful a factor has it been that living actors in the classic drama have accepted the conventions of the puppet stage and are trained to the gesture and manner of the ancient marionette. Their puppets were not quite half as tall as a man, and were maneuvered by operators who worked upon the stage in full view of their audience.

Puppets in Germany have been known at least as far back as the tenth century. This is not surprising when one stops to consider the luxuriant forests of Germany, the skill of the German people in wood-carving, and their delight in mechanical devices.

In Russia and in Czechoslovakia, puppets have long been an established art. In the former country there was a mystery performed annually on the Sunday nearest Christmas before the great altar of the Moscow Cathedral; and in the latter country, there were up into

the 1930's ninety-six itinerant puppet-showmen, or rather families, wandering over Czechoslovakia.

The earlier dramas of these countries were based either on religious subjects or on legends centered about historical heroes. One of the earliest uses of the puppet in Italy was made by the Church in the representation of the mystery of the Nativity, and for other important events in the Life of Our Lord. From the Church the puppet, like the big theatre, went out into the world to entertain both nobleman and peasant alike, the performances being given by showmen who set up their small, portable booths in palace or street, as the occasion afforded. By this time, tales of chivalry and satires were introduced. A little later comic characters based on local types began to make their appearance--thus, masks were born.

During the early days, the inhabitants of Europe were perhaps more familiar in comedy with the single glove-puppet than with other types, because jugglers and mountebanks often produced them from beneath their cloaks to delight their audiences.

At a later date in France, wandering musicians who picked up their living at various fairs, or performed along the wayside while travelling from town to town, were attracting attention with a new form of elementary puppet. This puppet was called marionnette a la planchette. "It consisted of a short plank with with an upright post at one end, to which was attached a piece of string, threaded through two jointed figures and ending in a slip-knot. The musician, having gathered his audience, placed the plank on the ground, slipped the loop about his leg, then placed his foot on the board and moved his leg in such a way that the figures danced while he accompanied their steps with music from a bag-pipe, or pipe and tabor."

In England it is evident that the Elizabeth-

ans were familiar with the puppet-theatre, for an Italian puppeteer established himself in London at an early date, and there are also many references to puppets in the works of Shakespeare and Ben Johnson. Milton is supposed to have received his inspiration for Paradise Lost from witnessing a puppet version of the story of Adam and Eve. Winifred Mills and Louise Dunn tell us that many people are surprised to learn that A Midsummer Night's Dream and Julius Caesar were written for marionettes, as well as Ben Johnson's famous play, Everyman in His Humour.

By the seventeenth century, puppet performances began to improve and were wellpatronized. In France they were so successful that living actors raised a protest and succeeded in driving the puppet-theatre back to the fairs.

In England about this time, we hear of puppet-shows through Pepys in his Diary, and also through The Spectator, and The Tatler. Charles II and his court are known to have been faithful patronizers, and to have held in · high regard the puppet-theatre.

By the eighteenth century, 'puppet-plays became more elaborate in treatment and presentation; and many members of the aristocracy had their own private theatres. It was around this time that Joseph Haydn composed the music for his five marionette operettas.

In 1753, Goethe was presented with a puppet-theatre, for which he composed many plays and, incidentally, received inspiration for his Faust.

In the nineteenth century, the puppet became more realistic, due to the ingenious mechanics of its construction. Some were even able to choke, cough, and spit. Actors were beginning to experiment with their own private puppets, as do John Barrymore and Tallulah Bankhead today.

Puppets here in North America are not new! The North American Indians for hundreds

of years used them for their great ceremonies. These puppets were operated in huts which were faintly illuminated by a fire. Their strings or other means of control were hidden, and their movements had an appearance of the supernatural. With the coming of the white man, however, most of them were destroyed, but a few have been discovered for the museums.

Most of the marionettes in America, until a few years ago, were Italian. A Sicilian theatre was operated for a number of years in New York.

IV

In the last decade there has been a revival of interest in the field of puppetry. At the end of the nineteenth century in Europe, puppet~ were more or less taken for granted. They were still, at the opening of the twentieth century, one of those familiar fixtures which one ceases to see. Little by little with our changing life and new amusements, they were forgotten altogether. Fortunately there had been at work literary and artistic forces which prepared the way for their spectacular comeback. As the century unfolded puppets became fashionable in parlors; while artists discovered their artistic possibilities in studios, performances were multiplied in old and newly established puppet-theatres, and puppet-plays and books about puppets were soon published, especially by Paul McPharlin.

The Revival spread to America, and through the hard and diligent work of such artists as Tony Sarg puppetry has been brought to the high place to which it belongs in the arts. Many names represent professional work in America today, such as Remo Bufano, Perry Dilly, Rufus Rose, Olga and Martin Stevens, and Marjory Batchelder. In educational work the classes extend from the lower grades through graduate work. A number of Ph.D. theses on puppets are now being registered. [ 8]

Puppets today are riding the very crest of a wave of popular, professional, and artistic recognition.

Besides offering immense scope as a means of dramatic expression and speech training, the puppet finds many new uses in presentday life. Puppets have been used in television broadcasts, and are found to be excellent broadcasting subjects. They have been used as salesmen and creators of publicity in commercial sales campaigns and advertising. We find them demonstrating, ballyhooing, or merely beckoning politely for groceries, refrigerators, scouring powders, cosmetics, bathing suits, floor wax-in short, almost anything that

manufacturers today want to sell to the world. Puppets are also used in hospital psychiatric wards. Reactions of certain mental cases while watching a puppet performance have been of great aid. Also they are used to give craft occupation to disabled adults. Another use of the puppet is as an educational factor in schools. Aside from the dramatic pleasure derived from making and presenting a show, there are numerous practical benefits, such as acquisition of skills, use of good diction, and unselfconscious practice in foreign languages. Puppetry offers such an enormous field for development that one sees more and more the truth in the Russian Efimova' s famous statement: "The puppet is as old as mankind, but its history is just beginning."

I close my eyes, and you are near again, And all the vows professed, unspoken and unknown

Your silence speaks to me through timeless spaceAll sanity, all reason now have flown. I shall remember only days like thisIf ever you should leave-not tell me whyYou are the substance of my soul, my lifeA star within the heaven of my skyBut even those can fall in meteor's flightFor we had dwelt in other worlds this night.

KIRA NrcHOLSKY.

On moonlit nights when the wind moans low And clouds ride swift and free, I dream of a cliff called Devareau Which overlooks the sea. It's the breeding place of thunderheads Where the sun's last rays appear; When its face is stained with twilight reds The drop is long and sheer.

In the distance Castle Devareau Looms dark against the skies. Its voice is the sound of the surf below And its windows are hollow eyes. The moon glows pale as a memory As, over the silver grass The shadows of pines move restlessly Where earth-bound spectres pass.

I followed a path one summer night Through the spray, along the rocks, When I caught a glimpse of a maid in white And wind in raven locks. I stood for a moment with bated breath As she turned and was suddenly gone, Like the wraiths that hark to the pipes of death In the first cold plush of dawn.

The sea won't tell though the waves intone Her name, like a prayer at night, To the cliff where I know the moon once shown On a girl who was dressed in white. What phantom shape did she hope to see, What tryst was it brought her there? I'll never know for I watched her flee While the wind was in her hair.

R.f.M.

fla:clc 7't:o-m1exa:J

A COMEDYIN ONE AcT

By WILLIAM L. MANER, JR.

Written in the Playwriting Class at the •University of Richmond! and produced at the Southern Drama Festival! University of North Carolina! Chapel Hill! on Saturday! April 6! 1940.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

SMITHTHOMPSON, a revolutionary veteran Phil Mason MARTINWYGAND,a church sexton William Ryan MATTIEBROOKS,wife of the Presbyterian minister Henrietta Sadler FANNIEBosANGCALVERT,keeper of the Wayne Tavern! a fiery Irishwoman Carolyn Gary JOHNNYPEA,local dimwit Alex Sternberg CLAUDIUSBusTER,a Democrat politician Salvadore Casale LIGECALVERT,Fannie!s husband . . Carlson Thomas

THE SCENE

The courtyard of the Wayne Tavern! Staunton! Virginia! on the fourth off ul y! 1836. It is early afternoon.

The scene is the yard outside a tavern. Surrounding the yard on two sides is a white rail fence! with most of the white gone. There is a gate in the back! center, with a pole on one side bearing a sign: Wayne Tavern, Elijah Calvert, Keeper! also Expert Tailoring. This last has been marked through, and Mrs. Fannie Bosang! Kee per! painted below it. To one side! near the corner of the fence is a stone wellhead with a small roof. On the other side is a large tree with a bench beneath. The tavern itself is off-stage beyond the well.

It is the Fourth off uly, 1836! and a small dirty fiag has been fastened to the sign in

honor of the day. As the curtain rises it is early afternoon.

Smith Thompson and Martin Wygand enter through the gate. Thompson is an old man! dressed in a baggy uniform of the Revolutionary War! cocked hat and all. He walks with a limp and uses a cane. Wygand is a middle aged man, on the dried-up side. He is dressed plainly in black coat and trousers and a dark felt hat. He is a Bavarian! and speaks with a slight German accent.

THOMPSON:Dag-nab it! I don't want to come here.

WYGAND:Yes, Mr. Thompson.

[ 11]

THOMPSON:This here's the biggest Fourth of July Staunton's ever seed, and I ain't gonna set here all afternoon by myself.

WYGAND: Mrs. Bosang told me to bring you here after the parade.

THOMPSON:Great shootin' cannonballs! I don't have to do everything Fannie tells me to. (Sits on the bench.) Let me go.

WYGAND: You can argue that with Mrs. Bosang.

THOMPSON:Don't call her. She'll just find something for me to do. She don't think I'm strong enough to go to the picnic, but she ain't particular about keepin' me strength when she's got something she wants me to do.

WYGAND:Being in a Fourth of July parade is a lot for an old man like you.

THOMPSON:I didn't walk. I rode in a carnage.

WYGAND: Isn't that enough? (Crosses to well and draws water.)

THOMPSON: I'm the only Revolutionary soldier around here, 'ceptin' Tom Evans, and he's a nigger and don't count, but I ain't so old I can't get around yet. And I want to go to that picnic.

WYGAND: Those Democrat politicians aren't interested in listening to you talk. They're nominating a president, and they've got more important things to do. (Dips water and drinks.)

THOMPSON: Dad gum it! If Lige Calvert waw here, I'd go to that picnic. He can handle Fannie. Bring me some water.

WYGAND: Ve don't vant no gamblers in Staunton.

THOMPSON: Lige was a honest gambler. He just shouldn't've played with the sheriff and the judge.

WYGAND: I'm glad they made him leave . And Mrs. Bosang is right not to use his name no more, when she has to pay for his debts.

THOMPSON:Lige is a better man than that first husband o' hers. And she's gonna miss

both of them. Fannie ain't one to like sleepin' alone.

WYGAND:You think he will come back?

THOMPSON: I dang sight wish he would. Fannie's gettin' powerful bothersome, not having nobody but me to holler at.

WYGAND: You think she might marry again, maybe?

THOMPSON: Fannie ain't one to miss no chances. But she's still got one husband.

WYGAND: Maybe he's dead. He's been gone a year now.

THOMPSON: Lige Calvert ain't dead. He can take care of himself.

WYGAND:You know whether she vants to marry, yah?

THOMPSON:Why are you so all-fired curious about Fannie's affairs fer?

WYGAND:I vas just vondering ....

THOMPSON: Just because you gave her money to pay them taxes, don't think you've got a free hand around here.

WYGAND:How did you know that?

THOMPSON: I hear things around here. That sheriff and Judge Stuart had that tax put on taverns just to git their money back from Fannie.

WYGAND:Suppose they did?

THOMPSON: Now you listen to me. Lige Calvert is my friend, and I ain't gonna have nobody, leastways a dad-gum church sexton hang in' around here try in' to take his wife.

WYGAND:I come here to sell her eggs and butter and potatoes.

THOMPSON:You don't sell her stuff every time you come. She don't feed me that much.

WYGAND:She still owes me for it.

THOMPSON: She'll pay you when she gits it. But that don't give you no right to marry her. I ain't gonna let her do it.

WYGAND:You think you can make her do what you want?

THOMPSON: She ain't gonna do what you [12]

want her to. Now go on, git outa here. (Nudges him with his cane.)

WYGAND: Be careful, Thompson, you're too old to be :fighting.

THOMPSON: If I can take care of :five redcoats, I can handle one church sexton, even if it is the Presbyterian church. Go on. Git. (Thompson pushes him angrily toward the gate.)

WYGAND:Don't push me, old man.

THOMPSON: Go on. Git out.

(Wygand resists, and Tham pson keeps pushing. Mrs. Mattie Brooks enters.She draws herself up at the gate.)

MATTIE: Oh! ... Oh!

(She starts back, horrified, her parasol ready for any defence she might need. Wygand starts back when he sees her.)

WYGAND:Mrs. Brooks! ah good afternoon, Mrs Brooks. I I. Good afternoon! (He turns to go, but comes ttp sharp when Mrs. Brooks speaks.)

MATTIE: Mr. Wygand. What are you doing here?

WYGAND: It ain't vat you think, Mrs. Brooks.

THOMPSON (Seeing his chance): Ain't it shameful?

MATTIE: I don ' t know what Mr. Brooks would say to this.

WYGAND: Mrs. Brooks, it vasn't me that vas

MATTIE: I saw you :fighting.

THOMPSON (Angling for sympathy): Me bad legs got me. (Hobbles to bench.)

WYGAND: Thompson. You vere pushing me. I vas not :fighting you.

THOMPSON: How could I be :fightin' a young fell er like you?

WYGAND:You tried to push me out.

MATTIE: .Mr. Brooks will certainly take this up with the church My husband will not have the sexton of his church misbehaving in a place like this.

THOMPSON: This here's a respectable tavern. Take him away from here.

MATTIE: It reeks with alcohol.

WYGAND:But I don't drink, Mrs. Brooks.

MATTIE: They sell it here, don't they?

THOMPSON: Where you smell whiskey, there's bound to be whiskey, that's what I always say.

WYGAND(Getting red in the face): I vas not drinking! And I vas not :fighting. You know I vasn't drinking. (To Thompson): Damn it, you damn, damn. .

MATTIE: You' re acting like you were drunk.

THOMPSON (Kidding him): Dag nab it, sexton. That's the way to talk. Cuss up.

WYGAND: Tell her vat you were doing. You vant to make me lose my job?

MATTIE: Mr. Wygand, don't yell at the poor man.

(On this, Fannie Bosang enters from the tavern. She is a peppery Irishwoman, still youngish, but beginning to age. She doesn't stand for any monkey business.)

FANNIE: Stop all this fuss in me tavern. Smith Thompson, what are ye up to?

(Thompson looks cherubic. Wygand turns to her for help, and Mrs. Brooks draws herself back. Fannie ignores her.)

WYGAND:Mrs. Bosang, I vas not :fighting. It vas Thompson.

FANNIE (To Thompson): What's the matter with you?

THOMPSON:Me? Nothin' Fannie.

WYGAND:He vas pushing me out, and he said I vas drinking.

MATTIE: He was :fighting when I came.

FANNIE: Fightin' Thompson?

WYGAND:He was trying to make me go.

FANNIE: Thompson, what've you been drinkin ' ?

THOMPSON: You know I ain't been drinkin' around here. (Resignedly.)

FANNIE: Well, what's eatin' on you?

[ 13]

THOMPSON: I didn't want to come back here.

FANNIE: I'm not going to have you brawlin' in me tavern.

MATTIE:But it wasn't him.

FANNIE: Yes, it was. If there's any row in', you can lay it to Thompson.

MATTIE: Is rowing the usual thing around places like this?

FANNIE: This is a decent, respectable tavern.

WYGAND:I just bring things from my farm to sell her.

MATTIE:I should think you could find better markets.

FANNIE: He just brought Thompson home from the parade.

THOMPSON: And I didn't wanta come, Fannie. You know' d that.

FANNIE: That doesn't concern the present argument. (To Mattie): I'm that sorry you thought Mr. Wygand was fightin'. He's the good man he should be.

MATTIE:Well, we won't say anything more about it. I'm glad that I saw it, instead of a member of the congregation. It won't get any farther than my husband.

WYGAND:Thank you, Mrs. Brooks. I vill go, now, Mrs. Bosang.

FANNIE: Your basket's in the kitchen, Wygand.

WYGAND:I'll go get them. (He exits into the inn.)

FANNIE: I've never seen you here before, Mrs. Brooks. Wont you sit down for a bit? (She nudges Thompson over to one side of the bench.)

MATTIE:I mustn't stay. My husband asked me to come. Is there a Mr. Buster here?

FANNIE: Mr. Buster? No. There isn't annybody here by that name.

THOMPSON:There's lots of other men here. Who is he?

MATTIE: He's representing Winchester at

the Harrison convention here. He's a very important man.

THOMPSON: He must be, to get you to a tavern lookin' fer him.

FANNIE: Be quiet. (To Mattie): Why' d you'd come here looking for him?

MATTIE:Aren't most of the General Harrison men here?

FANNIE: Yes, they are. Were you expecting him?

MATTIE: He should have been here last night. He's going to debate that Kinney at the picnic.

THOMPSON: That yankee what's workin' fer Van Buren?

MATTIE: Yes. I was very agreeably surprised in church this morning. He looked quite presentable. He's a Whig, you know.

FANNIE: I heard his speech was grand altogether.

MATTIE: He read it. And most of it was •just the Declaration of Independence.

THOMPSON: Knew the fell er what wrote that. Shaved him once.

MATTIE: My husband says he was warned about him. They say he's utterly depraved. He was drunk in Richmond last week, Mr. Brooks was told. In a hotel, too.

FANNIE: They tell me he's trying to raise money for the Whig campaign.

MATTIE:He won't get much money around here. Mr. Buster is bringing a large sum from Winchester with him for the Democrats, my husband tells me.

THOMPSON: You'd think women was in politics, the way you' re actin'.

MATTIE:Mr. Thompson, it's hardly respectable to speak that way. My husband asked me to find Mr. Buster.

THOMPSON: What's the matter? Does he owe you some of that money?

MATTIE:Mr. McCue asked me to share my lunch basket with him. We must let him know that the church is behind him, and his party.

[ 14]

THOMPSON: Is that respectable?

MATTIE: We stand for what is right. Mr. Buster is a very important man.

FANNIE: He isn't important till he gets here.

THOMPSON: His money's what makes him so important.

MATTIE: Mr. Buster's position is one of high character.

THOMPSON: He ain't showed up with his money yet.

FANNIE: It looks as if you aren't going to have a debate. He isn't here.

MATTIE: I do hope nothing has happened to him.

FANNIE: If he comes, I'll send him along. (Exit Mattie.)

THOMPSON (Yells after her): If you' re lookin' fer somebody to eat yer food, how 'bout me?

FANNIE: You aren't going to that picnic.

THOMPSON : Dag-nab it, F:annie. This here's a special day, and besides, I'm the only Revolutionary soldier left around here, 'ceptin' Tom Evans, and he's a nigger.

FANNIE: I'm not going to have you sick on me hands with me tavern full.

THOMPSON:Dag-nab it, Fannie

FANNIE: You've been resting yourself all day. Go and get the buckets and draw some water.

up after those men all day long.

WYGAND:I vant to talk to you , Mrs . Bosang.

FANNIE: Sit down, Wygand If it's about the money I owe you. . . .

WYGAND:Vell, part, Mrs Bosang

FANNIE (Her temper rising): Judge Stuart and Sheriff Bailey had those tavern taxes passed just to get their money back I don ' t allow gambling in me tavern, and Lige Calvert knew it.

WYGAND : I vas glad to lend you money to pay them last month.

FANNIE: Well, m y inn is full, and will be for the next three weeks, while those Harrison Democrats are meeting here, and what with the Knoxville teams coming through in another month from Baltimore, I'll be able to pay you what I owe you.

WYGAND:It ' s a lot of money.

FANNIE: You ' re a shrewd one, Wygand

WYGAND:It vas good business .

FANNIE: Me owing you ninety-seven dollars?

WYGAND:And three shillings.

FANNIE: You ' ve taken a risk.

WYGAND:It's vat you called invested.

FANNIE: It makes me so raging mad when I think Lige Calvert left with ever y cent we had in the house.

WYGAND:It vas a good thing he left town,

THOMPSON: If I ain't strong enough to go and vent somewhere else. to the picnic, you reckon I can stand toting

FANNIE: Wherever he is, he ' s out of m y them heavy buckets? reach now.

FANNIE: Get up and do something. Let

WYGAND:You v a s right to change your me sit down for a while. (Urges him up.) sign.

THOMPSON: All right, Fannie. All right.

FANNIE: The ta vern ' s mine from me first

I gotta go slow on me bad leg . husband .

(He exits to the tavern. As he goes out he

WYGAND:When are you going to take a meets Wygand coming in. He snorts at him third husband? and goes in. Fannie sits on the bench and fans

FANNIE: I've still got one husband, someherself with her apron.) where.

WYGAND:I left the eggs, Mrs. Bosang. WYGAND:Suppose he's dead? If he doesn't

FANNIE: I've been scrubbing and washing come back, he vould be dead .

[ 15 ]

FANNIE: Why?

WYGAND:That's what the judge said.

FANNIE: What judge?

WYGAND:Judge Stuart vas telling me, if a voman vants to marry, and her husband has been gone a year, he is dead, and she can marry agam.

FANNIE: I'm not going to marry annybody.

WYGAND:Why not marry me?

FANNIE (Incredulously): You?

WYGAND:The judge said you haven't got a husband after a year, if you don't vant him.

FANNIE: Have you been talking to the judge about me?

\VYGAND:Vhy not? You owe me money.

FANNIE: What do you think you' re doing talking to the judge about me without me knowing? If I want me husband dead I'll kill him meself, and not get anny judge to do it.

WYGAND:I've got a good farm and a good job.

FANNIE: You think I'd marry you for that?

WYGAND:With your tavern and my farm ve vould be rich.

FANNIE: This tavern's mine and there isn't annybody getting it by marrying me.

WYGAND:I vant to marry you or I vant my money.

FANNIE: I'll pay you when I get it. And you can stop coming around here.

WYGAND:You're not buying from me no more?

FANNIE: No. And I'll send you your money when I get it.

WYGAND:But you'll buy my eggs. I'll ask the judge vat I can do.

FANNIE: Don't you go consulting that judge about my affairs. 'Tisn't anny of his business. Or yours either. And I'll get rid of me husband the way I choose!

(She shoos Wygand off and shouts after him as he hurries up the road. Thompson appears at the inn as this is going on. He stands!

a bucket in one and! and in the other! hidden behind him! a bottle.)

THOMPSON:Fannie, what's ailin' you?

FANNIE: Nothing. Draw me some water.

THOMPSON(Crossing to the well! trying to hide his bottle): I don't understand you, Fannie. You holler at me fer gittin' after Wygand, then you turn right around and run him away yourself. What's he done?

FANNIE: 'Tisn't anny of your business.

(Thompson is having trouble drawing water and concealing his bottle at the same time. He tries to drink.)

FANNIE: You can't pull that bucket with the one hand. Use the both of them.

THOMPSON:I can git it, Fannie.

FANNIE: You can't lift it like that. What have yez got in that hand?

THOMPSON:What hand, Fannie?

FANNIE (Crossing to him): What have yez got?

(He is trying to conceal his bottle in the well ledge! and in doing it! he knocks it off into the well. Fannie sees him try to catch it. He gives up the pretense.)

THOMPSON: Dag-nab it. Now look what you've done. (He looks down the well.)

FANNIE: Haven't I told you to keep out of that whiskey?

THOMPSON: It warn't your good whiskey, Fannie.

FANNIE: Well, it's wasted, now.

THOMPSON:Kin I have some more?

FANNIE: No, you cannot. Now draw that water. I'm going to sit here and wait. (She sits on the bench. Thompson draws slowly.)

THOMPSON: Is you goin' to marry Wygand?

FANNIE: That isn't your business.

THOMPSON:Yes, it is, Fannie. Now don't you fer git about Lige.

FANNIE: How can I forget him?

(Thompson has the bucket up! and he sniffs [ 16]

at it} then takes a quick sip. Fannie sees him and comes out of her revery.)

FANNIE: Stop drinking that water. You won't get a good drink of that whiskey if you drink the well dry.

THOMPSON:Looks like I ain't gonna unless I do.

FANNIE: Get out there from under me feet. (She takes the bucket from him. Thompson heads for his bench as Claudius Buster enters. He is a large man, very impressive. He carries a wo-rn valise} and his coat is over his arm. His bright vests parkles in the sun. He is in a hurry, and stops, panting, at the gate.)

THOMPSON:Howdy, mister.

BUSTER:Good afternoon, sir. Are you the proprietor?

THOMPSON:Well, now, nope. I ain't. But I.

FANNIE: If you' re wanting the tavern keeper, it's me.

BUSTER:How do you do, madam. I am Claudius Buster.

THOMPSON:Say. Ain't you the one they is all loo kin' fer?

BUSTER( Momentarily startled out of his dignity): Looking for me? Who? Where?

THOMPSON:Yeah. Ain't you gonna speak at this here convention?

BUSTER:Oh . . . yes. Yes, indeed. And I'm late for it, too. (Turns to Fannie): I should like to get a room, madam. Right away.

FANNIE: Are you in a big hurry?

BUSTER: Yes, I am. The stagecoachman sent me this way. We were delayed overnight.

THOMPSON:Yeah? What happened?

BusTER: I'll tell you the story later. I should like to ...

THOMPSON:Oh, you got time now. Plenty of time.

BusTER: We hit a ditch and broke a wheel. We had to spend the night in a tavern called the Bell.

FANNIE: That's the widow Mitchell's place. It isn't anything at all but a stable.

BUSTER:It wasn't comfortable. (Impatient/y): Madam, I would like to go to my room. I'm in a hurry.

FANNIE (Taking her time): If it's comfortable lodging you want, I can give you that. Me place is clean and me rates is regular, set by law. Wan in a bed with wan clane sheet, two and three pence; wan in a bed, two clane sheets, three shillings; two in a bed, wan clane sheet, three and six pence; two in a bed, two clane sheets, four shillings. Three in a bed, wan clane sheet, nothing. You'll have to share. We' re crowded.

THOMPSON: Don't put him in my bed, Fannie.

BusTER (Losing patience): I'm sure you'll do the best you can for me, madam. J\nd now, if you don't mind ....

FANNIE: You're a Harrison man, aren't you?

BUSTER(Resignedly): Yes, madam, I am. A firm backer of General Harrison. The hero of Tippicanoe; a fearless warrior. I am throwing my influence behind General Harrison, and I know that when he is elected. . . .

FANNIE: You'll have to share a bed with somebody. And there isn't annybody left but that Van Buren man, Mr. Kinney. Or you can sleep in Thompson's bed, and he can stay in the kitchen. His isn't much of a bed, though.

THOMPSON:You ain't gonna put him in my bed, is you?

FANNIE: I am if I can get money for it.

BUSTER:I'd prefer that, madam. And I'll pay you well. Only, please hurry.

THOMPSON:Why don't you pay me? It's my bed.

FANNIE: You don't pay me, do you, Thompson? You sleep in the kitchen.

THOMPSON:Dag-nab it. You'd think that being a Whig was cat chin', the way you Democrats stay away from them fellers. You might

find him entertaining company for the night.

BUSTER:He'll be entertaining enough when I debate him. And I'm late for that now.

THOMPSON:Everybody thought you wasn't coming, with all that money you got.

BUSTER (Alarmed): Money? I have no money. Where did you hear that?

FANNIE: No money? Well, me rates is cash.

BusTER: I mean I have no large sums. What are you talking about?

THOMPSON:I heard you had a lot of money for the convention. That's why they been lookin' fer you so hard.

BusTER (Upset): They're looking for me for money? They are wrong. There was some money raised, but-ah-it's all being spent in northern Virginia. I only wish I did have some money for the fund.

THOMPSON:Hey, Fannie. Maybe he could borrow from Wygand, too?

FANNIE: Shut up, you old omadhoun.

BusTER (In a frenzy): Will you show me to my room, please? I'll pay you in advance, if you wish.

FANNIE: That'll be foine. I'll accept Virginia pound notes, but I don't welcome them. (! ohnny Pea comes marching in through the gate. He is a simpleminded young man, dressed in nondescript trousers and shirt, and is carrying as plit oak basket, which he at the moment is playing, like a drum. He makes the sound of a rolling drum with his lips as he marches up. He has a blue military coat over one arm.)

JOHNNY: Brrrrrummmmm. Brrrrummmm. Brrumm Brrumm Mrs. Calvert. Hey. Hey. Mrs. Calvert. Halt! (He halts.)

FANNIE: Go along with you Johnny Pea. I don't want to buy anny of your peas today.

THOMPSON: Hello, Johnny. How'd you like the parade?

JOHNNY: Brrrummm. Brrummm. I like the

drums. Brrummm. Mrs. Calvert. That soldier at the picnic wants you to fix his coat.

THOMPSON:What soldier?

FANNIE: I haven ' t got time to fix anny coats now, Johnny. What's the matter with it?

JOHNNY: He tore it. See?

THOMPSON:That there looks like Kinney's coat. He wore one like it this mornin'.

BUSTER:Kinney? Is that his coat? Where is he, boy?

JOHNNY: Who?

BUSTER(Irately): The man you got that coat from?

JOHNNY: Oh! He ' s down where the rest of the soldiers are. Brrruummm.

FANNIE: You wait here, Johnny. This way, Mr. Buster.

JOHNNY: All right, Mrs. Calvert. Brummm. Brrrummm. I'm gonna get me a drum. Brrumm.

(Fannie goes in the tavern. Buster waits . for her to go in, then hands f ohnny a coin.)

BUSTER:Here, boy. You go back to where the soldiers are. Tell Mr. Kinney you couldn ' t find anybody to fix that coat. Understand?

JOHNNY: But Mrs. Calvert said to wait. I don't know you.

THOMPSON:That there ' s Mr. Buster.

JOHNNY: I don ' t know him.

BUSTER: Take the money and go. (To Thompson): If he can't get his coat fixed, he can't speak.

(Buster exits to tavern.)

THOMPSON:You better find somebody else to do that mendin', Johnny. Lige Calvert ain't around now, so you'll have to find another tailor.

JoHNNY (Bites coin, then puts it aw ay): Where is Mr. Lige? He's good to me.

THOMPSON: Don't know, Johnny. But I wish he was back .

JOHNNY: Huh. Me, too.

THOMPSON:You just take that coat back to the picnic grounds and get some of the ladies

[ 18]

there to fix it. That's probably what he don't want done.

JoHNNY: I'll go back and see the soldiers. Bruummm. Brrrummm.

( f ohnny marches off through the gate.)

THOMPSON: Heh . Heh. Crazy as a loon. But he likes Lige.

(f ust as f ohnny gets off stage, he turns and comes back, very excited. He points up the road.)

JoHNNY: Hey look hey it's him! (He bounces up and down in his excitement.)

THOMPSON: What's the matter, Johnny? What's happened?

JOHNNY: It's him.

THOMPSON:Who?

JOHNNY: It's Mr. Lige. Mr. Lige. (He goes off at a run to meet Lige.)

THOMPSON: Lige? What are you talkin' about, Johnny?

(He hurries to gate as Lige enters with f ohnny f ohnny is bouncing up and down beside Lige, saying rrMr.Lige" in a happy sing song. Lige has his coat over his arm, and carriesa tied up bundle. He and Thompson greet each other with great gusto.)

THOMPSON:Great jumpin' generals! Lige! Lige Calvert! What're you doing here? Where'd you come from?

LIGE: Hello, Thompson, you old loaf er.

JOHNNY: Mr. Lige. Did you see the soldiers? Bruummmm. Brummm.

THOMPSON: Holy suffering angels! I'm glad to see you, Lige. I sure am glad you' re back.

LIGE: I hope I'll stay, Thompson. Where is everybody? The town looks deserted.

J OHNNY (Marching around): Brrummm. Bruumm. I saw a parade this morning, Mr. Lige. I sti ll go fishing.

THOMPSON: Say, you look fine, Lige. Everybody's down at Bushy Field.

LIGE:I hear they've got a big crowd here for the politicking.

THOMPSON:Yessir. There's some real big men here, now.

JOHNNY: I still got that knife you gave me. There's lots of soldiers down there. With drums, and fifes, and flags. (He imitates all three.)

LIGE: Sounds like big times.

THOMPSON: Y essir. An' I rode in the parade this mornin' right behind the drums. Jes' like I always do. But Fannie wouldn't let me go to the picnic. Dad-gum, but I'm glad you' re back, Lige.

LIGE:Where is Fannie? I want to see what she'll say when she sees me.

THOMPSON: She's gonna kick up the dirt when she finds out you' re back.

LIGE (To f ohnny Pea, who is fiddling with his bundle): Leave that alone, Johnny. What's ailing Fannie, as usual?

(f ohnny stops and squats on the ground near Lige.)

THOMPSON (Importantly): She's maybe gonna marry agam.

LIGE: Fannie? She can't do that. Who's she thinking about marrying?

THOMPSON:That Martin Wygand.

LIGE ( Making gestures to describe Wygand): You mean . . . that feller?

THOMPSON:Yep.

LIGE(Laughing heartily): Martin Wygand. Hahahahahahahahaha.

THOMPSON:Tain't funny, Lige. It's mighty liable to happen.

LIGE: I can't believe that. What's the matter with Fannie?

THOMPSON:You took all her money with you, and she's been buying eggs and things from Wygand and she ain't paid him for none of it. Then 'bout a month ago that Judge Stuart and the sheriff had the taxes raised so's they could get back what you won from them.

[ 19]

Fannie had to borrow it from Wygand to pay the taxes.

LIGE: Well, if it's money she needs, I think I can match him. (He pulls out a leather pouch full of money and jingles it.)

THOMPSON: Where'd you git that money, Lige?

LIGE: There ain't no money in tailoring, Thompson.

THOMPSON: Fannie ain't gonna stand fer no gamblin'.

LIGE:It ain't gambling, 'cause I always win.

THOMPSON:How much is it, Lige?

LIGE: One hundred and fifty dollars.

THOMPSON: Where'd you git all that money? You can't win money like that around here.

LIGE: Unless there's a lot of politicians around.

THOMPSON:You better be careful. Them fellers is slick. They has to be.

(f ohnny Pea suddenly stands up and touches Lige on the shoulder.)

JOHNNY: Mr. Lige. Can you fix this?

LIGE: What do you want, Johnny?

JOHNNY: You make clothes, Mr. Lige. Can you sew this?

LIGE: Where did you get that, Johnny?

THOMPSON: That coat belongs to that Whig.

JOHNNY: That man at Bushy Field told me to get it sewed up.

LIGE: What happened to it?

JOHNNY: She tore it. I saw her.

THOMPSON:Who?

JOHNNY: That girl. Clara.

THOMPSON (Very interested): Clara! What was goin' on?

JOHNNY: Huh?

THOMPSON:Come on, Johnny. What happened?

JOHNNY (Very emphatically): Huh unh. I ain't gonna tell.

THOMPSON: Well I can guess That Van Buren fell er better watch out.

JOHNNY: Will you fix it, Mr. Lige? He said hurry.

THOMPSON: H~ sure made a big impression at the Presbyterian church this morning when he read the Declaration of Independence dressed in that there military uniform. All the ladies thought he was downright handsome.

LIGE:Liked him, eh?

THOMPSON: Yep. Them womenfolk always cheers loudest when the Infantry passes by in a parade. Seems like it's always been that way.

LIGE: You found it so?

THOMPSON: Yep. Why, I remember durin' the war, if I was wearin' a uniform, there just wasn ' t anything you couldn't do. Y essir. And nice lookin' girls too.

LIGE: You like uniforms, Johnny.

JOHNNY: Yeah. I like soldiers. I'm gonna get me a drum and be a soldier.

THOMPSON : I guess that's why Kinney ain't gonna make his speech until he gits his coat fixed. If you was in a uniform, mebbe Fannie might even soften up some.

LIGE: Say, Thompson. You suppose that would work?

THOMPSON: What? You mean wearin ' a uniform to make Fannie like you? It might. But I been wearin' one for years, and it don ' t do me no good with her.

LIGE: Johnny. Give me that coat. I'll fix it.

JOHNNY: You gonna fix it in a hurry, Mr . Lige?

LIGE: I don't know how fast, Johnny, but maybe I can fix it. You go back to the picnic and tell him its being fixed. Come back later.

JOHNNY: You gonna fix it. I'll tell him He ' s hidin' in the bushes waitin' for his coat. I'll tell him. Brrrummm. Bruummmm. You go fishing with me sometime, Mr. Lige?

LIGE:Yeah, Johnny. Mebbe tomorrow.

[ 20]

(Johnny marches off.)

THOMPSON: Women'll do anything fer a man in a uniform. They must think there's something special about him. And specially a wounded man. Why, I remember once, soon after the battle of Guilford it was, there was a pretty little thing on a farm where I stopped to git something to eat. Wounded in me leg, I was. And she sure took a special favor to me. Wanted to dress my wound, and there wasn't anything she wouldn't do for me.

LIGE:You' re still limping from that wound.

THOMPSON:And it still gets results. There ain't no better combination than a wound and a uniform.

LIGE: A wound, eh? Let's see what I've got. (He fiexes his arms}his legs}trying to see what he}s got.) Walk some, Thompson. Let's see how you do it.

THOMPSON(Walking acrossthe stage): If you throw in a extra limp, like you was about to fall, like this, it helps.

LIGE: How's this, Thompson?

THOMPSON: Put a little more drag in that foot. That's better. Heh. Heh. Good.

LIGE: Watch me, Thompson. (He goes to the door of the inn} then turns.) Thompson. Call her.

THOMPSON:Call Fannie out here?

are on his shoulders. He's tired of war.)

FANNIE (Throwing her hands up in surprise): Oh. Glory be, it's himself.

THOMPSON:Look, Fannie. Lige is back.

LIGE (Rushing to her): Fannie. Fannie. (He embraces her, but she pushes him back.) Fannie. It's me. It's Lige. Remember?

FANNIE: Don't try anny of your fetching tricks on me, you dirty snake.

LIGE: Fannie. It's your husband.

FANNIE: As if I don't recognize the very shadow you cast.

THOMPSON: He just walked in. Just like that, Fannie. I was just sittin' here, and in he came.

FANNIE: That's what you get for sitting idle.

LIGE: Oh, Fannie. How good it is to be back home again.

FANNIE: Is it now?

THOMPSON:That sure is a handsome lookin' uniform, ain't it, Fannie?

LIGE: You don't know what it means to be back.

FANNIE: Yes, I do. Where'd you get them clothes you' re wear in'?

LIGE:I want to forget all that, now, Fannie. I'm back.

THOMPSON (Winking): Yeah, Lige.

LIGE: Yeah. Tell her who's out here. Where did you get that uniform?

THOMPSON:You're just calling out a pack

LIGE: I don't want to talk about that. I've of trouble. I hope it works. (He goes to the been through too much. door.) Say, Lige, where you gonna tell her

THOMPSON (Pursuing the subject): You you've been? been in the army, Lige?

LIGE: Oh ... Texas. Now call her.

FANNIE: The army? Lige Calvert, what

THOMPSON:Fannie. Hey, Fannie. would you be doing in the army?

LIGE: Get excited, Thompson. Make her

LIGE: Fighting, Fannie. think I just got here.

THOMPSON:That there coat looks like you

THOMPSON: Fannie. Hey, Fannie. Come was maybe a captain, eh, Lige? out here. Fannie.

FANNIE: What would you be fighting for,

FANNIE (Inside): What's the matter with excepting yourself? you, now, Thompson?

LIGE:I gotta sit down, Fannie. I can't stand (She comes to the door. Lige stands there, up for long. (He staggersto the bench. Fannie weary and worn. The troubles of the world is impressed for the moment.)

[ 21]

FANNIE: What's the matter with you? Lige Calvert, you aren't coming back here sick, are you?

LIGE: Get me some water.

THOMPSON:You sit down, Fannie. I'll get the water.

(Thompson goes to the well and gets a dipper of water. Fannie crosses to the bench where Lige is sitting.)

FANNIE: What's the matter with you?

LIGE: It's my wound.

FANNIE: Your wound? Where?

THOMPSON (Bringing water): You musta been in some real fightin', Lige.

LIGE: Thanks, Thompson. It's just a spell. I get them every now and then. Since I was shot.

FANNIE: Shot? Where?

LIGE:In the war.

FANNIE: No. Where were you shot?

(He groans, gives her a look 1 and rises· from his bench. Then he settles back.)

THOMPSON:Were you hurt bad, Lige?

FANNIE: You aren't going to be like Thompson here? I'm not going to have two loafers hang in' around all the time.

THOMPSON:It's just my leg, Fannie. Comes in spells. ,.

LIGE: I can tailor sitting down.

FANNIE: You can play cards sitting down, too.

LIGE: Fannie, you don't know how many times I longed for you while I was away. For days while I was wounded, I lay in the hot Texas sun.

FANNIE: Texas?

THOMPSON:You go all the way to Texas?

LIGE: All I thought of was you, Fannie. I'd

call to you. Fannie. I was dying of gunshot wounds and thirst. "Water," I cried. "Water, Fannie. Fannie, water. Water. Fannie." I was delirious for days. When I woke up I was in a tent with Fannin's cavalry.

22]

THOMPSON:You was fightin' with Colonel Fannin?

LIGE: I've seen some desperate battles, Thompson. Some I've lost, and some I've won.

FANNIE: You joined the army? You haven't been gambling?

LIGE: Because you made me leave, Fannie. Why, Thompson. In my last fight, I took over a hundred prisoners.

FANNIE: You left of your own free will. You' re a cruel, blackhearted scamp, running away from your wife, and disgracing her with your card playing.

LIGE: It was a fair game, and I won fairly.

FANNIE: But you didn't have to win from the judge and the sheriff in me own tavern, and then offer to cut cards with the Presbyterian minister to see which one would go to hell when he taxed you for gambling.

THOMPSON: That was funny, and you know it, Fannie. You laughed yourself.

FANNIE: I don't know whether I'll put up with yez around me house or not. I've been thinking maybe I'll get the judge to declare me free of you forever.

THOMPSON:Fannie, you ain't really going to do that?

LIGE:But, Fannie. I'm your husband.

FANNIE: You haven't been me only one, and you're not likely to be me last. I won't go begging for any husband.

LIGE: Fannie. What do you mean?

(Wygand enters 1 intently. He draws up sharp when he sees Lige and the rest of the group. He is dumbfounded.)

WYGAND:Mrs. Bosang, I.

FANNIE (Vexed at Wygand for showing up to call her bluff): What do you want?

THOMPSON:Yeah. What do you want?

LIGE: Fannie. What does that bell-ringer want?

WYGAND(Finding his tongue 1 and point-

ing a finger at Lige): Mrs. Bosang. Vhat about me?

LIGE: Her name is Calvert. What about you?

THOMPSON: Looks like you gotta tell him, Fannie.

LIGE: Tell me what?

THOMPSON: There just ain't no way out of it, Fannie.

FANNIE: No way out of what?

THOMPSON:Ain't you gonna tell him about you maybe marryin' that?

LIGE: Marrying? That?

WYGAND:Vell. Vhy not?

FANNIE: Thompson. You know that isn't so.

LIGE: Is that what you' re making your next one, Fannie?

THOMPSON: I heard you say so, Fannie.

FANNIE: Oh, be quiet, Thompson. It isn't so, Lige. I just owe him money.

LIGE: What do you owe him money for?

FANNIE: Because you with your black heart ran off with every shilling there was in the house.

WYGAND:But, you said, Mrs. Bosang

LIGE: Calvert.

FANNIE: Go away, Wygand. You'll get your money. I thought I told you.

THOMPSON: Lige'll fix that. Won't you, Lige?

LIGE: How much?

FANNIE: Ninety-seven dollars. (She breathes deeply.)

WYGAND:And three shillings

FANNIE: Yes, and three shillings.

LIGE ( Casual!y): Is that all?

(With a grand gesture he pulls out his pouch1 counts out some bills1 and hands them carelessly to lf/ ygand. Fannie stares.)

FANNIE: Where did you get all that money, Lige Calvert?

LIGE (Pocketing it as she reaches): It's me army pay. I saved it all.

WYGAND:But, Mrs. Calvert.

FANNIE: Go and ring your church bells, Martin Wygand. You've got your debt.

LIGE: And you've got your husband. Don't forget that.

WYGAND: Yah, but I don't vant just my money.

THOMPSON: Lige and me don't want you around here no more.

LIGE:No. We don't, do we, Thompson?

THOMPSON:Lige and me got a lotta practice shootin' durin' our army days, and once you git the fever, you just want to keep on shootin'.

LIGE:Usually that way, Thompson.

(Wygand backs off, and exits running.)

FANNIE: Stop all this nonsense. Lige Calvert, tell me about that army pay.

LIGE: Ohhhh. It's me wound again. Ohhhh.

FANNIE: You sit still. I' 11get something to mend it with.

LIGE:No, Fannie. It'll be all right.

THOMPSON: Jest let him set a while, Fannie.

FANNIE: I'm not going to have you sit around here doing nothing. I'm going to cure that wound. You aren't any use to me crippled

(She goes inside to get the bandages. Lige jumps up from his bench.)

LIGE:I knew that money' d make her change her mind. She's not going to let that get away from her.

(He waves the bag up and down. His back is to the inn door1 and he doesn't see Buster enter. Thompson does1 and tries to signal him.)

THOMPSON:Hey, Lige. Sit down, quick. (Lige stops and backs up to his seat quickly. Without looking1 he puts on his act again.)

LIGE: Fannie. Give me your hand. You're so good to me.

THOMPSON: Hey, Lige . It ain't Fannie. [ 23]

(Lige looks up and sees Buster. They recognize each other.)

BusTER: Say, what's your game here?

LIGE: Where'd you come from?

THOMPSON: That's one of them Harrison Convention fellers, Lige. You know him? Name's Buster.

BUSTER:He knows my name. (To Lige): I didn't think I'd run into you here.

LIGE: I can't say I'm happy to see you here right now. Though you do hold a pleasant place in my memory.

BusTER: What's your game here?

THOMPSON: Say, Lige. Do you know this feller?

LIGE: Slightly. We sat together in a game in Winchester.

THOMPSON: Oh. Oh.

BUSTER:I'll get in your game here, too.

LIGE: You aren't invited.

THOMPSON: Say. Ain't you in a hurry to that picnic?

BUSTER:Yes. But I've got time to straighten out some urgent business here.

THOMPSON:You better hurry to that there speech.

LIGE: All my business with you is over, I think.

BUSTER: That's where you're wrong. I'd like that money back.

(Fannie enters with liniment and bandages.)

FANNIE: Here's some snake root, fresh from the Indians in Buffalo Gap.

BUSTER: Is this man a friend of yours, madam?

FANNIE: In a manner of speaking. He's my husband.

THOMPSON: Don't you reckon you better be gettin' on to that picnic.

FANNIE: Lige, have you met Mr. Buster?

LIGE: We've met.

where he's been fighting the Mexicans for the freedom of Texas.

THOMPSON:Maybe you'll lose your debate if you don't hurry.

LIGE: He's not interested in what I've been doing, Fannie.

BUSTER:But I am. Very interested.

FANNIE: The Texas war was a good cause.

THOMPSON:He and me both fit fer a good cause. He was wounded, too.

Bu

STER:You weren't wounded last week.

FANNIE: Last week? Did you see my husband last week?

THOMPSON: Say, you better hurry, Mister.

BusTER: Yes, I did. ln Winchester.

LIGE: He did, Fannie. But I was just on my way home.

BUSTER:Did he bring home any money?

THOMPSON:It's his army pay, ain't it, Lige?

FANNIE: It is. And he's just paid off a hundred dollars debt for me.

LIGE: And here is the rest of it, Fannie. For you to have.

BUSTER:That money you've got. ...

THOMPSON (Remembering something): Say. Ain't you supposed to be bringin' a lot of money for the Democratic campaign? That the people in Winchester gave?

BUSTER:What? ... No. No. I guess you are right. I'd better hurry, or I'll be late for my speech. No. You're mistaken. I have no money for the campaign. I only wish I did.

LIGE (Light dawns): Hey. I'll bet you do wish you had it.

BUSTER:Madam, if you're looking for a good investment for that money, I should be more than delighted to handle it for you.

FANNIE: I'll invest me own money, thank you. (She invests it in her dress.)

THOMPSON: If you're looking for investments, why don't you try Wygand?

( Mattie Brooks enters rapidly.)

MATTIE:Has Mr. Buster arrived yet? I saw west, the stage pass the field.

FANNIE: He's just back from the [ 24}

BUSTER:I am Mr. Buster, Madam. Do you wish to see me?

MATTIE: I'm Mrs. Brooks. My husband is the Presbyterian minister. You are to share my basket with me.

BusTER: I should be delighted, madam.

LIGE: Your husband and the rest of them churchmen is strong for Harrison, ain ' t they, Mrs. Brooks?

MATTIE: Oh! It's that man! Shall we go, Mr. Buster?

THOMPSON: That there Van Buren fell er don't like gamblin' either, does he, Mr. Buster?

BusTER: Come, Mrs. Brooks . I want to

meet a Mr. Wygand. Do you know him?

MATTIE: Oh, yes. (They exit.) I do hope you'll like my basket.

FANNIE: I don't like this, Lige. What were you doing in Winchester?

LIGE: I think my wound is healin ' , Fannie.

FANNIE: I want to see that wound, Lige Calvert. (She drags him to th e inn.)

LIGE: You ain't gonna be disappointed, Fannie

(They exit to the inn together. Thompson w atches them go.)

THOMPSON: She'll soon forget about that wound, if I know Lige Calvert.

(C URTAIN)

25]

By EDWARD BARNWELL WALKER, JR.

Damn 'f;m, .f?awd{

Oh, Lawd, who tole dem blusterin' fools

Ter come an' break mah heart?

Wha' fo' dey steal mah li'l shack?

An' tuhn me free ter roam?

Damn 'em, Lawd!

Free! Dat's wut dey said Ah'd be; Free f' om de massuh's whip.

Oh Lawd, you know de wuses' blow

Mah massuh put on me,

Was de time he stroked mah achin' haid

De day w'en Ah was sick.

Who told dem fools dat we was beat, Dat we was treated mean?

Dey tuhn us loose; Ah had mah share; Ah'm sicko' bein' free!

Ah want mah :fiel' o' sugar cane,

Mah plow an' wukkin' do' es,

De feel of a bag o' sof' est cotton

A-draggin' on de groun'.

An' de happy song o' sweatin' dahkies

A-.floatin' t'ru de air.

Mah feet is tired, mah back is bent;

Dis thing called freedom done it.

Ah want mah home, plantation home.

Oh, but Ah'm lonesome, Lawd!

Dem scums wid guns an' pretty speeches 'Bout equality o' man,

Dey took mah home an' lef' mar heart

A-bleedin' on de groun!

Damn 'em, Lawd!

1fte~taii

A trav'ler on the road of life

Espied an ancient man whose face

Was seared by years of strife and failure; A crooked staff he leaned upon.

Then spake the traveler: "What may be

The name of your staff?" A wise man heard

And said: "For sooth, I know its name: Surely, it must be 'I Would Have, But.' "

~olution

After school when I'm tired of the job of protecting my grisly young pate

From the :fistsof all the profs that my face and my brains irritate,

My favorite haunt seems to be, I belate,

An easy chair which I should abdicate

For the texts that my hate

Radiate.

The glow of the lamp as it falls on my head so serene and content

Shows a face with a smile and a pipe and a nose prominent.

All a-glow with the peace of the moment heaven-lent.

But alas! To my nose comes the scent

Of my texts-imminentExigent !

My comfortable smile dies the cold bleak death of a shaded satellite

As I growl like a wolf and glare like a snake, at the blight.

And then the blights seem to shriek with joy at my plight!

So there, little :fiends!You alight

In the :fire.Be contrite And ignite.

[ 26}

?2ew4o1ke1t

There are deeper roots and firmer Grasping richer grounds than these. There are finer roots of living Than are yours-New Yorker. And the tunnels and the buildings That you glue together here-

They are weak and find you wanting For the truthfulness of earth. Where are all your brittle laughters When they bounce from iron walls? In your eyes there is a gleaming But that light is dry and dead, Since the sun has left you scheming For a new electric head.

You are hiding in a whirlwind From the calm of day without.

You are building in your turmoil Only what has been before.

Have you ever seen the equal In your highest, richest dream Of one face, one leaf, one flower Of one snowflake in the air?

ALYS D' AVESNE.