~~±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±~±±±±±±±±±±1±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±+±~±~

~~±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±~±±±±±±±±±±1±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±+±~±~

~,~,-<::::,-<::::,-<::::,-<:::::>-<:-:>-<:-,-<:-,-<:-.,,,:::-.,,,:::-.,,,:::--,,<:-,,<:-,.<:-,.<:-,.<:-..,..,:::-..,..,:::-..,..,:::-,..,::::--,.<:><:><:><:>

VOLUME d::~-\l.II (o&; DECEMBER, 1939 No. 2

~~,<::::>,<::::>,<::::>,<::::>..<:::,..<:::,..<:::,..<:::,..<:::,..<:::,,.,C-,,,.C--,,.C--,-.<:--,-.<:--,-.<:--,-.<:--.,,,:::-.,,,:::--,.<--,-<--,,<:-,,<:-.,.,:;:-,.<:-,.<:-.,,.,,::::y<::::::.-<:::::,

: SAMUEL CHILES MITCHELL

By St. George Cooke

Rese ar ch by S. L. Gettier

SHANGHAI - AFTER THE WAR

By Louise Wiley

--- THE STAR FOLLOWED" .

By Kitty Crawford

By Reini Bernstein

By R. f. Martin

By W. Maner

By Henrietta S ad ler

~.-<:::,..<:::,..<:::,..<:::,..<:::,,-<::::,-<::::,-<:::::,,<:::::,,<::::><:::><:::><:::ye::><:::><:::><:::><:::>-<:>-<:>-<::,,.<.::,~~

: WALTER E. BASS, Editor-in-Chief; OWEN TATE, Richmond College Editor,· MABEL

LEIGH ROOKE , Westhampton College Editor; T. STANFORD TUTWILER , HARRIET YEA-

: MANS, Busi ness Managers,· SIMPSON WILLIAMS, Assistant B11siness Manager; HELEN :t ::; HILL , PHYLLIS ANNE COGHILL, JEAN NEA SMIT H , Westhampton College Advisory B oard,· FLORENCE LAFOON, ARTHUR BROWN, Art Editors; STRAUGHAN LOWE GETTIER, Re-

sea rch Editor; HENRIETTA SADLER , Non-Fiction Editor ,· ETHEL O ' BRIEN , BOB MARTIN, ::; P oetry Editors,· KIRA NICHOLSKY , Assistant P oetry Editor,· PHILIP COOKE, KITTY CRAWFORD, Fiction Editors ,· VIR GINIA McLARIN , Book Review Editor; ROBERTA WINFREY,

4

'Tl Assistant B ook R eview Editor.

'Ti

By ST. GEORGE COOKE

Research by S. L. GETTIER

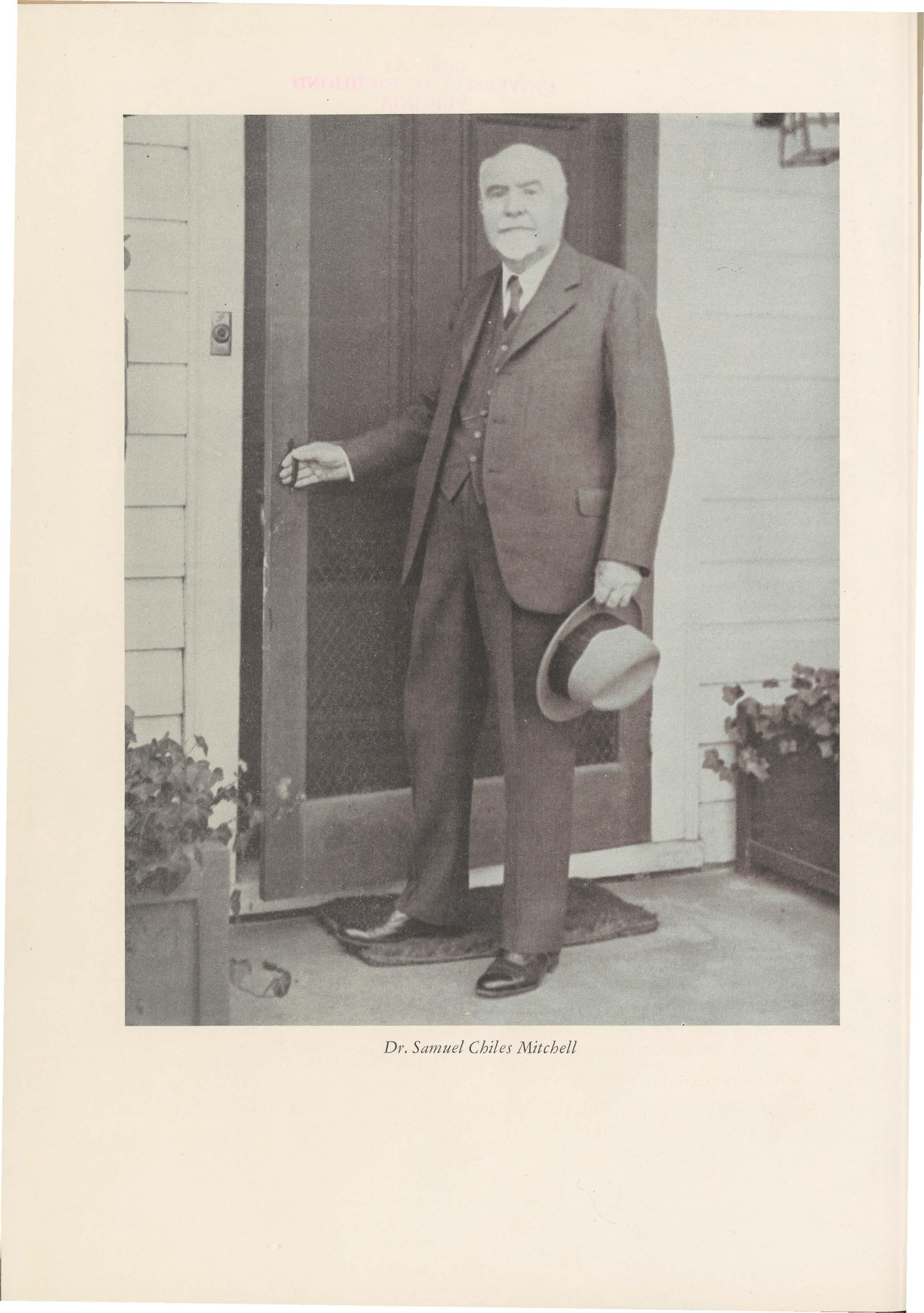

A man-child was born in Mississippi. The place: Coffeeville. The time: December twenty-fourth, 1864. The parents: Morris Randolph Mitchell, and his wife Grace Anne Chiles Mitchell. Their son was christened Samuel Chiles Mitchell. That was seventy-five years ago.

Following the schedule made famous by the late Horatio Alger, young Samuel, minus funds for a college education, began to work for his living It was his good fortune to accept a position as clerk and general handyman for an uneducated grocer named Terry. Samuel had ambitions. He wanted, as all do, to make his way in the world; to make a name for himself. Terry was interested in his young employee. He listened while the young Samuel told of his ambitions-he listened and thought of himself. Where would he be if he had had the chance of an education? Here he was the grocer of a small Mississippi town, getting along in years, never having had a formal schooling. And here was his clerk, a young man just starting his life; ambitious, eager to learn, penniless.

Terry pondered. He listened again and again to the young man who wished and dreamed to do things; big things. Terry thought of himself and what the outcome of his life had been. Terry came to a decision.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Of some men it can be said: "To know them is to love them." One of them is Dr. Mitchell. It is impossible in so short a space to portray fully the qualities which make him a great man. We feel assured, however, that those who do know him will understand and appreciate what we have tried to do. It is our hope that those who do not know him will, from this brief, see why and how we respect and honor him.

Terry was the moulder of a man. Samuel Chiles Mitchell is a moulder of men.

Samuel Mitchell's college education at Mississippi College was subsidized by Terry.

Terry must have been a dreamer; for only a man with dreams could have guided a great man through the first steps of a distinguished life and career and to have instilled into the young man: To do unto others as ye would have them do unto you.

A graduate of Mississippi College, Samuel Mitchell decided his calling was that of God. He entered a seminary, graduated, and was ordained the Reverend Samuel Chiles Mitchell.

Reverend Mitchell did not let his education stop there. He was then, and remains today, a seeker of knowledge. In 1888, at the age of twenty-four, he received his Masters Degree from Georgetown College. The foresight of Terry began to bear fruit. At Georgetown students Mitchell and Metcalf sat under Professor Reuben H. Garnett, a graduate of the University of Richmond, in the Greek Department. Professor Garnett, after having a nervous breakdown, said before his premature death, "I will live through Mitchell and Metcalf."

The next year Mississippi College listed Mitchell as a Professor of History and Greek.

The influence of a great man was beginnmg.

For two years, (1889-91) the young professor taught at Mississippi State before he accepted a chair at Georgetown College as a Professor of Latin. At the end of the first of four years ( during two of which he did some studying at the University of Virginia) he was to occupy the chair of Latin.

At the age of twenty-eight, Professor Mitchell married. On the thirtieth of June, 1891, Miss Alice Virginia Broadus, of Louisville, Kentucky, became Mrs. Samuel Chiles Mitchell. They are now completing their fortyeighth year of happy married life and, with the plaudits of the world ringing in his ears, Doctor Mitchell is still "Mister" Mitchell to his wife.

1895. The newly appointed President of Richmond College, Dr. F. W. Boatwright, made his first official appointment to the faculty. As Professor of History: Professor Samuel Chiles Mitchell. For nine years he was to hold that post. While teaching at the University of Richmond Professor Mitchell was working in the graduate department of the University of Chicago, from which he received his Ph.D. in 1899.

1908. Doctor Mitchell accepted the Presidency of the University of South Carolina, which position he held until 1913. He was also lecturer in History at Brown University during 1908-09, and was honored with a Doctorate of Literature from Brown in 1910. The same honor was bestowed upon him by Baylor University in 1913.

Born in a slave state before the Civil War had decided definitely the question of slavery in the United States, Dr. Samuel Mitchell's boyhood was spent during the darkest years in the history of the South, the Civil War and the Reconstruction. Reared amid poverty, knowing what it meant to be poor; observing the effects of the times upon the underprivileged,

Mitchell, early in life, adopted a liberal policy. He sought to instill in others his ideas of social appreciation and betterment. He gave to the University of South Carolina their motto: "Our Campus The State." In his efforts of social reform Mitchell ran into trouble.

The trouble was personified in the person of a state official and a trustee of the University.

A Negro-hater of the worst sort, an enemy of free thought, he was summed up by a contemporary as: "A rascal so bad you can't libel him." Doctor Mitchell handed in his resignation as President of the University of South Carolina rather than have his ideals crushed by one who did not understand them nor make any attempt to understand them.

In the year 1913 he accepted the Presidency of The Medical College of Virginia tended to him by those whose creed was, and is: "A man's thoughts are his own."

As president of The Medical College of [6}

Virginia, Doctor Mitchell brought about a merger with the University College of Medicine. Having accomplished what he had set out to do, he resigned in 1914 to accept the position of President of Delaware College. Doctor Mitchell entered the Presidency of a college, leaving it in 1920 a university, and today the University of Delaware remains one of the greatest monuments of Doctor Mitchell's ability.

In 1914 his accumulating honors were increased when he received an LL.D. from the University of Cincinnati.

In 1920 he once again returned to the University of Richmond. Today Doctor Mitchell is ageing in body, but his mind remains forever alert. Standing in front of his classes, dressed fashionably in English tailored clothes, his eyes sparkle as he lectures; those who walked the hall are often startled at his vigorous, sharp, voice driving home a point into the heads of his students. Sometimes shouting, sometimes so quiet is he that it is difficult to understand what he is saying beyond the second row, Doctor Mitchell carries on the tradition of Terry. He claps his hands together with a loud whack!-points the index fingers of his hands in the general direction of the students in the fashion made popular by two-gun men of the western movies"Thou shalt not think!" he shouts. His voice grows soft and the twinkle comes into his eyes. "That's an old Southern law. You're excused." The class disbands noisily.

Dr. Mitchell is a Trustee of the Jeans fund, a foundation which has as its purpose the "assisting in the southern United States community, country, and rural schools for the great class of Negroes to whom the small rural and community schools are alone available." He is also a member of the American Historical Association, Phi Beta Kappa, and of Phi Gamma Delta Social Fraternity.

Dr. Mitchell was editor of the section on

Social Life in the twelve-volume series, The South in the Building of the Nation, publicized by the Southern Historical Publication Society.

As his birthday approaches, and the winter winds grow blustery and cold, "Dr." Mitchell can be seen walking about the campus, wearing a dark overcoat, grey hamborg hat, grey gloves. He walks with short energetic steps, his shoulders bent, round; books in his hand. His figure is distinguishable from a great distance by all who have met and know him. As they come closer the first thing which is noticed is his white moustache and goatee. He has a word for everyone who walks by. Those who pass often stop, turn to watch him. Such is their respect.

On January third, 1935, a testimonial dinner was given in honor of Doctor Mitchell by those who know and have worked with him. Distinguished personages from all over the United States came in person or sent their regrets by letter or telegram, over two hundred of which were received. The committee for the dinner was made up of such distinguished men as: Dr. Douglas Southall Freeman, editor of The Richmond News Leader and a Columbia University professor; the late John A. Coke, of The Life Insurance Company of Virginia; Jacob Billicoff, of Philadelphia, Superintendent of the United Jewish Charities; Colonel Thomas Branch McAdams, of Baltimore, President of The Union Trust Bank of Baltimore; Howard L. McBain, head of the graduate department of Columbia University; and others.

The dinner was conceived by President F. \Xr. Boatwright. Two hundred and twelve persons attended among whom were: the former Governor of Virginia, the late John Garland Pollard; Dean Metcalf; Dr. Witmead and Dr. Josiah Morse of the University of South Carolina; Dr. James H. Franklin; to name but a very few.

[ 7 J

Doctor Mitchell was evidently thinking of the long departed Terry when he made his speech that night. He said: "If my friends encourage youth, I shall be amply rewarded."

Later, his voice sharp, tart, class-roomish: "Can a man become a myth while he's still alive; a mirage while he walks the streets of Richmond?''

Yes, Doctor Mitchell, he can.

Later that month, the twenty-fifth, Doctor Mitchell's portrait was presented to the Medical College of Virginia. Dr. Wortley F. Rudd, Dean of the School of Pharmacy in the Medical College of Virginia, presided at the ceremony. In a letter to the MESSENGERhe commented: "I was a student in 1895 when Doctor Mitchell came to Richmond and was a member of the first class he taught after coming here. It was evident from the first that a

great personality was among us. You know full well how this promise of great usefulness has been fulfilled across the years."

Another letter to the MESSENGERfrom Dr. Douglas S. Freeman makes the statement: "I was one of Doctor Mitchell's students and have been one of his disciples ever since."

Still later that year Doctor Mitchell, on leave of absence, made one of his frequent trips to Europe. One of his present students, having spent several weeks in London and professed to know the city fairly well, said: "I never realized how much of London I really missed until I took a class under Mitchell."

Doctor Mitchell has acquired a great insight into the minds and workings of his students from his five children: Broadus, Morris Randolph, Terry, named in honor of the man who had given him his chance, Mary Adams, and George Sinclair; and they have acquired much from him. His aim is to make students think for themselves. "Your teacher is always wrong!" he shouts, clapping his hands and pointing. "Give me your differences!". . . "I don't know anything except what I learn from my pupils." "Give me your name." The name is given. "Mister C-- has a mind of his own. He entered this class especially to teach me. I learn from him! You're excused." Someone has summed up his life with these words to which we agree:

"Only an institution of a noble and progressive turn of mind, backed with courage, can have a chair distinguished with the name of Doctor Mitchell. He is a man, who by ideals, has risen above all practical cliff erences; above the narrowness of those with whom he sought to labor.

"The tumult which ensued, the conflict of his vision with the stubbornness of ignorance has now subsided into the peace of final acclaim."

By LOUISE WILEY

Having lost her heart with the destruction of her dreams and hopes, Shanghai is nothing more than an empty shell-a city without a soul. Only the ruins are left of her factories, her trade and her dream city, the Civic Center.

Since many years ago when only a cluster of mudhuts kept a junk trade plying up and down the river, Shanghai, draining the wealth of China, had grown until three million people were jammed on those same mudflats. Once ocean liners, huge floating hotels and godowns, anchored in midstream, were surrounded with numerous satellite barges and lighters, being loaded and unloaded by rumbling cranes. Bales of cotton swung up and down into the crater of the ship's hold. Boxes marked Seattle, Marseilles, and London bumped down the side and were piled high by sweating and swearing swarms of coolies. Puffing and squealing launches carried lines of houseboats, mountained with vegetables, rice and fruit. Squatty tramp steamers disgorged their oil drums, their coal and their steel girders onto trucks and carts. Sanpans impudently bothered the long grey warships, derisively begging the cold monsters for garbage and junk. The patched and colorful, orange, brown, blue and grey junk sails, bellied forth in the wind, scooted their fishermen out to sea for the night's catch.

Along the wharves, great factories hummed night and day, wreathing the city eternally in grey smoke. Twice a day a sea of humanity spilled out from their iron gates and high, spiked concrete walls to be swallowed up in the rows of grey-tiled tenements. At six in the morning and at six at night a chorus of sirens

filled the streets with blue-clad workers. Some swinging tin lunch boxes, emptied of their cold rice, wearily plodded home after twelve hours of sweat over cotton and silk looms. Others, just starting out, munched golden, fried bread sticks or stopped for a bowl of hot noodles, cheerily talking over the squeaks of the wheelbarrows, which carried pigtailed and permanented girls in from the country. Then the roaring of a half million shifting workers was gone and the rumbling of the mills again took their place.

Beyond the factories, from the mudflats and reeds along the river, rose the curved green and gold tile roofs of the Civic Center. Here on a stone pedestal, Sun-Yat-Sun, a grey man dressed in a long Chinese gown and carrying a Western hat, overlooked the fulfillment of his dreams, "Greater Shanghai." Here both the new and the old were combined; the buildings with their ancient curved roofs and painted beams, crimson lacquered columns and carved balustrades were reenforced by modern concrete and steel. Also ancient China was found in the scrolls and manuscripts of the library and treasures of the museum. Modern China was realized in the hospital center, the athletic buildings, and housing projects. The war has destroyed all these dreams. Now there are great shell holes in the green and gold tile roofs. Fires have been built on the marble floors, and the library and museum are only a crumbled, blackened mass of steel and stone. Where once was a roaring factory district, now there is an unearthly silence. In place of the rows of tenements, there seem to be only piles of giant burnt matches. Where a.

million people lived and slaved, only ghosts wander over piles of broken brick. The great market is covered with weeds. In the middle of the street a chair stands by a three-legged table. Stores still have faded bolts of cloth on their shelves. The breakfast dishes are still on the table in a silk store. No one has touched them since that morning when the war came, leaving one half of Shanghai in ruins.

In the foreign settlements which are left, horror and suffering hover over the refugees, crowded together, waiting for the gaunt skeletons to drop in the streets by the hundreds. They must have rice to live, and there is no rice. On the edges of the city enormous piles of coffins blaze up. Those that are left have tried to deaden their spirits by gambling and opium. In the midst of this suffering and death more gambling is done than anywhere in the world. Not content with the deadening of men's souls, the Japanese hold the entire city under their terrorism, so that blockhouses guard

every large street intersection; and all day long policemen stand with their fingers on the triggers of machine guns.

On a once busy street corner a few coolies walk by the barbed wire barricades and concrete blockhouse, not even bothering to step over a dead child, just a tiny bundle of rags. Refugees huddle on the floor of a former music store, and in the display windows the evening's rice bubbles on a pot of coals. Hate flashes through the glass and clings to the khaki back of a Japanese soldier. Tightening his finger on the trigger of his sub-machine gun, a French officer shivers in the cold wind. The owner of a pawn shop thrusts his head around the stone spirit screen, but relieved at the emptiness of the street, turns his attention back to the warm green celadon, clutched in his hand. Only this morning it had been brought in and exchanged for a few dollars, this precious heirloom of generations, now forgotten for a few handfuls of rice.

My comrades walked with me one night,

All laughing, joyous, young and free. They pressed me close on every side

But I was locked within myself, And felt that I was all alone-

A solitary soul stripped bare

Of warmth and love and pleasant things . Somehow I could not seem to find

A solace in their friendly cheer

But walked remote, unreached and chilled,

A stranger in the peopled night.

LILA WICKER

By KITTY CRAWFORD

All day the crowds had swirled in and out of the great front doors of Merriam's Department Store, arms laden with bundles, weary faces pinched under the strain of last minute Christmas shopping, tired feet relentlessly plodding past counter after counter, department after department. All day they had thronged up one aisle of the magnificent store, down the next, pulling, pushing , jostling , surging, congregating around bargain count- to the other with no apparent motion of her ers, eddying away in little ripples of satisfac- thin body. Oily and suave behind her, breathtion, heedless of the lavish decoration of the ing his avid breath on her neck, stood Mr. store's every corner-its silver ropes swinging Rubinstein, the floor manager, seeming to from pillar to pillar, the costly silvered fir rub his paunchy hands together even while trees on every shelf, the stacks of fragrant pine they were clasped discreetly behind him. Past and holly, piled with so careful an assumption them, and hundreds like them, the mob of carelessness, behind every stall. The roar poured, fluent, seeking every corner, swelling of their cries, the noise of their frantic search like a flood with each onrush of new customdrowned out completely the massive organ ers. Feet, feet, feet-that was all he could see, and massed choir of a hundred voices in the the little errand boy, beyond the wheels of his center of the building, chanting with shrill overloaded cart, the feet of those who obeffort the conventional carols. structed him: slippers and oxfords and high-

The steady pulsing tramp of their feet had heeled boots and rubbers and saddle-shoes, worn a path through the soul of the girl at the back and forth, around and around they perfume counter until she was mad with the swirled in their steady monotonous rhythm. persistent throbbing of it in her; yet she must Heel, toe; heel, toe; heel, toe; passing above smile and smile and keep her hair in place, and his head-it was an old song to Jim in the gently shift her weight from one aching foot basement, who had been at Merriam's since

the store was a Ulle-room house downtown, who had been faithfully tending the furnaces for years on end, until he had become blacker even than his own kind. The sound of the feet was a happy sound in his ears, for it meant to him the growth of the firm, and this he attributed in no small way to his masterly handling of the furnaces up the years. He did little now, because of the ache in his back, left the actual work to his several assistants, but his managerial eye surveyed all, and all the credit was surely his. The rhythm of the feet, feet, feet, could still be plainly heard far above on the fifth floor, muted now by distance into a great pulsing hum, music in the ears of J. Smythe Merriam, president of the firm. Each footstep in the harmony of that whole Mr. Merriam saw translated in terms of its purchasing probability, and unlimited profits rolled up before his eyes as the harmony went on and on and on-would they never stop coming and going? Up one aisle and down the next, through the day and into the darkness with never a pause, and the lights came on, all silver and blue until Merriam's first floor was a mammoth cave of blue crystal and icicles; up one aisle and down the next, heedless of the silver and blue and the electric candles of the great pealing organ and the ever shriller voices of the choirboys, crowds, pulling, pushing, jostling, surging on and on and on

Just inside the massive front portals of Merriam's, awe-inspiring as the gates to Heaven, in the midst of blue crystals and glittering icicles and silver ropes swinging from pillar to pillar, stood Santa Claus. The ridiculous incongruity of his bright-red suit and white flowing whiskers went unheeded by the swirling throng, as did his kind voice wishing them all a very Merry Christmas. It had long been a custom of Merriam's with their conservatively spectacular policy, to station a Santa at the front door every Christmas Eve

to wish the patrons a happy holiday. Each departing child was presented with a tiny bag of cheap candy, each adult wished a cheery Merry Christmas-with a genuine twinkle in the eye, and a hearty handclasp. Nobody counted-or could have counted-the hundreds of bags of candy, the thousands of merry good wishes, the millions of happy smiles which had been scattered into the crowd so sincerely, so generously. It was as though the man had tapped an inexhaustible reservoir of joy and holiday spirit which could not be worn thin by the tramping of many feet, nor wearied by the surging of many bodies.

The doors were to close at ten, and the glittering blue lights cut out, even though it tore Mr. Merriam's heart to turn away so many prospective purchasers, but the girl at the perfume counter could no longer stand the strain, and she had crumpled in a chair, Mr. Rubinstein greedily solicitous above her; the thin little boy pushing the heavy cart had deposited his last package gratefully; the old negro in the basement had ordered the fires put out over the holiday; and even Mr. Merriam, in his plush, inner-spring, swivel chair, confessed to a feeling of tiredness. Two hours to Christmas

Only the man who had stood at the great front portals seemed not to feel the burden of the day upon his broad shoulders, standing there still, wishing all who passed the very best of Merry Christmases. It was the numberless throng of employees now, passing on their weary feet, a defeated stoop to their shoulders, for whom he held open the heavy bronze door: the old, the middle-aged, the young, those who had been with the store since their light-hearted years, those who were taken on just over the holiday, all passed through the heavy bronze portal and into the night beyond, past the man in the Santa suit,

[ 12}

with the deep, kind eyes and the heartfelt wish for good cheer.

The girl from the perfume counter, teetering down the marble floor on her absurd little heels-she had changed from her working shoes-as she came, the pitter patter of her footsteps echoed hollowly through the dim reaches of the store The silver rope swinging from pillar to pillar, vaguely discernible now in the half-light, mocked her with its suggestions of Christmas parties and laughter and

him than of the man in the Santa Claus suit who had bidden her so hearty a Merry Christmas, who had looked at her with deep, kind eyes like pools of sympathy. . . . The night was still and cool upon her face and throat, the stars little candles burning on Heaven's Christmas tree ... . What had he said to her, that man in the Santa Claus suit, to have given her so suddenly a still, warm center of peace in her heart, to have made the cold night so suddenly lovely, to have made a beauty a very real and precious thing? His words she could not remember-only the simple communion of their souls when his eyes looked into hers: only the exaltation of her spirit on Christmas Eve. With singing steps she moved quickly away into the beauty of the night, leaving the expectant Mr. Rubinstein standing motionless on the hard pavement, one hand still twitching slightly ....

The little boy stuck his calloused handsscarred from his rough work at pushing carts - into his patched pockets, hunched his shoulders against the coming cold , and walked softly down the marble aisle toward the heavy bronze portals. His bony fingers clutched in his pockets the two dollar bills which were his reward for pushing carts around all day; crumpled with them, in scared proximity -a dirty greenback whose exact figure the little boy had not quite seen, in his sudden sly dancing and happy faces and plenty of good hurry to seize it and be away. Yet he did not food;thesilverfirtreesinthecornerswerepiti- run, for They were not after him, They had fully reminiscent of the attempt she had made not missed the bill, could not with all the to decorate her lonely hall room. Christmas- money They had collected today; They didn 't tinsel and glitter and wrapping paper and need it, and he did, for his mother and his feet, and a chance to sleep for her; but on the baby sister. They needed food and gosh! other hand, there was always Mr. Rubinstein. they could have a swell Christmas turkey, She passed through the heavy bronze door maybe, and a shawl for mother, and a blanket and into the night beyond, with the vague for little Baby, and lots of swell things for realization that he was directly behind her, his him. And They would have just bought more greasy white hand slyly enclosing one thin silver ropes and silver fir trees and silly stuff arm hopefully; yet she was less conscious of with it. .

[ 13]

He was in the street now, one hand clutching a tiny bag of cheap Christmas candy, the other folding and unfolding the bill so large in his pocket. What had Santa Claus said to him when he passed through the heavy door into the night? He could not be quite sure of the words, but he did remember, with a quick lump in his throat, the deep, kind eyes, like his mother's when the pain was extra-bad and she was smiling through her tears at him

quick motion, wiping his nose on his sleeve, he turned to go back into the store. . . .

The old negro shuffled down the marble aisle, his worn shoes flapping rhythmically against the stone, his dirty figure dwarfed by the high pillars and the dim vastness of the store he had loved so long. The cold, forbidding majesty of the place-he stopped in his slow steps and looked around and up, into depths and heights. He had seen it grow into this from the time when ol' .1-farseRobert was running the little store over on Fourteenth Street behind the fish market. Hadn't had no pillars or silver ropes or fir trees then; just one room and a storeroom back of that, and a great big stove that stood behind the one long counter, and blew smoke into the room all day. Lawd! There wasn't no furnaces in Marse Robert's day, nor no organ with choirboys singing Christmas carols either; Marse Robert sold his Christmas trees right out of the .family lot, didn't put no silver stuff on. He'd been in Marse Robert's store since he were a barefoot kid, and then when ol' Marse John moved uptown, he come with him , and ol' Marse John always treated him right, say "Hello, Uncle Jim!" like he was a white man. And then young Mr. John come along, he don't care about ol' people around, he says he wants new people who can do more work

-sympathetic eyes which looked so under- than ol' people. . . . And the hard, cold stone standingly into his: why must he feel as though of the pillars was no harder nor colder than he were going to cry? But even beyond his the simple words printed on the paper in the tears there was an unexplainable joy in his negro's gnarled old hand-"Your services heart, a feeling of promise and hope-as will no longer be required after the New though everything were going to turn out all Year." ... His lip sagged and quivered, and right somehow, because it was Christmas Eve, suddenly he felt the weight of his years and Santa himself were going to come down upon his shoulders like a load of wood, and his chimney tonight with a swell Christmas the solemn, unusual spectre of Age and Death turkey, maybe, and a shawl for his mother and stared him for an instant in his wrinkled old a blanket for little Baby. And the bill, so face. Surely his days were growing shorter, large in his pocket it was Theirs, after and his weary feet could carry him not much all; he had almost forgotten it. And with a longer; slowly he began his shuffle again to

[ 14}

the heavy bronze portals at the front of the store.

The wind that came around the corner in a hurry to get home to bed ran sharply into the old negro standing motionless in the middle of the sidewalk. In one hand he held a battered hat, careless of the cold on his grizzled head; in the other hand he clutched a tiny bag of candy. He had been given it by the man in the Santa Claus suit with the outstretched hand and the deep, kind eyes, and the fine, warm voice wishing him a Merry Christmas or was that exactly what the man had said? The old negro was not certain, he could not remember, his memory played tricks on him. He was getting old, surely, and yet suddenly he did not feel old at all, but young -in heart and in spirit, and his unhappiness fell from him. Lonely and old and unwanted he was still, and the store which had been father and mother and friend to him was his no longer; but there was a warm core of peace in his heart which protected him against the cold, and his hand was warm where a firm

handclasp had lifted him into fellowship with something eternal, and his eyes were warm where other warm, deep eyes had looked with kindness and love into his. And he knew, even without knowing that he knew, that when he had-and soon-put out his life's last furnace, there would be a long holiday of warmth and fellowship and love for him . . ..

Mr. J. Smythe Merriam tapped his ivoryheaded cane smartly against the marble aisle as he swung along, well-groomed, impeccable, hard with a hardness that matched his architecture. It had been the biggest day in the history of Merriam's, and the profits had rolled up into tremendous amounts, staggering even to the experienced eye of Mr. J. Smythe Merriam. He really wished Christmas would come more of ten, this Mr. Merriam, almost smiling at his own little joke. Even the silver ropes swinging from pillar to pillar, the silver fir trees on their shelves-all were symbolic of the prosperity and success of his firm: the stone, the beautiful decorations in crystal and blue, the pealing organ, all the grandeur and glory of it he revelled in, the magnificence of it, the wealth it represented; he resented anything, anyone, who detracted one iota from the splendor of it. And the massive bronze portals further satiated his ego, with their carvings and exquisite workmanship

But the high vault of the ceiling of Heaven with silver ropes of stars swinging from the pillars of night mocked him as he stood silent on the sidewalk, and still words echoed in his ears, whose sound he could not catch, but whose thought was heard and understood in his heart. . . . What had the man in the Santa Claus suit said to him that he should feel so suddenly his smallness and loneliness in a world which was his for the buying? What words reverberated in his soul to make him see so suddenly clearly the hollowness, the bitter emptiness of his life? He remembered [ 15 }

too well the deep, clear eyes of the man, piercing his soul in all its pitiful shallow~ess and false values and sordidness, stripping him before his own eyes of all the walls of straw behind which his little petty soul had crawled, leaving him naked and ashamed before his own face. Yet there was in that moment kindled in his soul a tiny flame of peace and lasting happiness, and he was quickly, humbly grateful for the little things in life which loomed now so large in his eyes-home and children and a fireside; night and stars and the spirit of Christmas still moving upon the face of the earth.

My imaginings take me Wherever I want Whenever I want, And the men I see Or the voices I hear

On these excursions

Live on a plane

Five miles (mentally speaking)

Above the stratosphere of experience

So that when I come back

To the ground of rationality I sometimes crash.

ALYS D' AVESNE.

After the last had left, and the final blue light had been cut out, the man at the heavy bronze door stood quietly in the midst of silence, listening to the echoes of thousands of hurrying feet, the peal of the mighty organ, and the choirboys chanting carols. Then he too went out of the portal and into the night beyond. High above the deserted streets and buildings, in the crisp coldness of the new day, hung a single star, large and clear and bright. The man walked slowly down the street, and as he went, the star followed overhead.

Weep, my children, Weep and cry. Your silly father's Gone out to die.

The guns will rattle The bullets fly, And bloody corpses Like cherry pie

Run red and sticky Where they lie.

ALYS D' AVESNE.

By REINI BERNSTEIN

The game of golf was originally played only by royalty and is thus very aristocratic in origin, if not in practice. Its object is to hit the ball with a certain degree of regularity Once this result is achieved the game ceases to be golf and becomes a business.

A course consists of 19 holes, the 19th being the most important. Curiously enough, those who have played badly for the first 18 holes usually make a fine show at the last, fre- · quently getting home with a full midriff at this very long hole. Sometimes the course only consists of 10 holes, but the tenth is still called the 19th out of habit.

On the course are

found many strange geographical features. Take, for instance, teeing grounds, which are of two kinds. The first is a very small, uneven piece of ground, covered with a generous layer of soft sand or earth; the second is a very large piece of ground, covered with the choicest grass, per-

fectly kept and so hard as to render the insertion of a tee impossible. Obviously either of these varieties is calculated to inspire the player with terrific confidence. A so-called fairway, which, however, is little used, leads from the tee to a sharply undulating space called, even in summer at some of the out-of-the-way courses, a Green. These again are of two kinds, being either very small with a very fast surface, or alternately very large with a very slow one. On the very edge of the greens lies a small hole, called a "Hole." In it rests a wooden pole with a flag on top, named a Pin, or an iron pin with a bunch of wool on top, named the Flagstick. When the green is reached it is lifted out so that the opponent is unable to see the whereabouts of the Hole. There are many kinds of hazards, some natural, others supernatural. These last have a curious power of moving about, so as to catch the player's ball [ 17]

wherever he hits it. A particularly violent hook or slice, however, will occasionally put their judgment at fault, and will merely finish up in a thick bush or be carried off by a dog.

Every good golf course has a stream, called creek, which flows at least three times round each green and has quicksand in the bottom. Every ball which is sucked under by the sand is carried away by an ingenious drainage system, and reappears in the professional' s shop the next day, to be painted up and sold as a new ball. Other hazards include spinneys, whinneys, rabbit holes ( these also lead to a secluded nook behind the professional's shed) , mouseholes and bogholes, ponds, pools, whirlpools, and cesspools, gullies, gulches, glens, banks, and braes.

Golf courses are literally studded with shelters, except in rainy districts, where they are extremely rare. Each shelter has a hidden filter on the roof which catches all the rain and passes it through in the form of spray onto the players standing beneath. They are also furnished with collapsible chairs, which collapse in a wonderful way when sat upon. Direction posts are placed at blind holes, to indicate the direction a player must take in order to finish in the large pot-bunker on the left of the green. They thus save many strokes for the visiting golfer.

The art of golf is twofold. It consists of trying to play well oneself, and to make the opponent play badly. The latter can be effecteel in various ways, the former in none. Any long-handicap man will tell you that, as a man plays well, he ceases to be a golfer and becomes a machine.

The golf er has numerous devices at his command for putting his opponent off. The most commonly employed are (a) Smearing soap or hair-grease on his club-handles before starting; (b) Treading his ball into the ground on every occasion; ( c) Sneezing or otherwise articulating just before the moment of impact.

Often, however, no impact occurs, and this artifice then ceases to be necessary. Neither is it necessary during the putting process; in fact it may even have a boomeranging effect, and succeed in causing the opponent to hole out on his third attempt, a very sad occurrence indeed.

The first essential towards good golf is the acquisition of a good swing. For this purpose a professional should be consulted, or not, according to the professional. After the first lesson, granted normal progress, the beginner should not use more than 36 shots off the Tees, 72 on the Greens, and 144 off the fairways, while his working vocabulary will not exceed 288 words. After two lessons these figures should be halved, after which a well-deserved visit is payed to you-know-where. If the player does not follow this custom he cannot be considered a true golf er. There are others whom no amount of teaching can improve, who descend ever deeper into a morass of repressions and other phobarium. With respect to these, one can only mention the old and tried formula, that distance lost equals vocabulary gained. Others again quickly pass out of the golfing stage, and enter upon the merely mechanical. They do not come within the scope of this treatise.

The tyro should spend at least 2 5 hours a day in diligent practice. He is adjured to return to the teeing ground after finishing each hole, to make sure that the ball he has lost is not still resting on the tee. Another alternative is to examine the peg closely before leaving the tee, instead of gazing into the middle distance and trying to pretend that the ball has gone somewhere. He should also take out a friend's bag of clubs as well as his own, so as to have something to throw into the stagnant water on the left of the 13th green.

Some rules of courtesy must also be observed on the links. For instance, after driving into the back of the fat man in front, one

should not pass by without a word, nor make a bee-line for the Club, but humbly explain that you had shouted "Fore," and that, as he had lifted his head while playing his shot, you had to conclude that he had heard. You had never done such a long shot before and would probably never do it again. (Here you are probably right.) These rules do not apply when you are nearing the 18th green, nor where a convenient bush or wood is at hand. In addition, they naturally apply only when dealing with teetotallers, parsons, and old incorruptibles generally. Never play from a tee until the two old ladies in front have left it; they might think that you wanted to go through. And never play onto the green until they have holed their 3-inch putts; you might make them miss, and 39 for a hole sounds much better than 40 for these dear folk.

Again, never approach a green while a " tiger" is taking his 30-yard putt. He might fail to hole it. Do not forget that, when a tiger is held up by a rabbit on his morning round, the tiger is always in a hurry to get back to an early lunch, and be tactful when you see him

play three balls on the next few fairways. In order further to observe the etiquette of golf, a player should refrain from deflecting his opponent's ball as it approaches the hole, bending down under the opponent's legs and removing the ball from behind, working his ball into a pot-bunker while he is not looking, or any other such minor indiscretions These rules do not apply when playing with an undersized business clerk with a doormat moustache and a weak chin or a very shortsighted man. Women cannot be trusted on any account.

Various public nuisances will be found on any golf course, and must be avoided. For instance there is the professional, who sends out a groundsman every night to change the position of the hole, while leaving the flag stuck into the ground in its former position. By this means he doubles the sale of the bar, of whose profits he takes 75o/o . Then there is the secretary, who will constantly remind you that your dues are not yet paid, and who always drops in at your home when you don't want him.

I awoke to a new and glistening world, With a dread feeling of stale, dead hopes.

The world was brittle, crisp, alive and cold, And I was so afraid-and growing old. And clutching madly with a stiffening handI thought he knew enough to understandTo the last taut string that tied us to the pastI did not feel the cold and icy blastI held too tight; it sprung and hurt my handI thought he knew enough to understand.

I awoke to a new and glistening world, \Vith a dread feeling of stale, dead hopes.

KIRA NICHOLSKY.

[ 19]

By R. J. MARTIN

Conventions have always proven themselves to be walls which KNOWLEDGE must struggle to surmount. Con. ventions of superstition and ignorance drown in their stagnation the LIGHT which can enable men to free themselves from natural social error. And many nations have perished because they preferred to grasp at a nearby straw rather than wait for the coming life-boats. An analysis of destructive philosophies is found in THEMAN. The circuitous route or interpretation is left to the reader.

The Editor.

There once was a country in which learning that moved again with life not their own. had progressed to a great degree and wherein In the time of harvest it was found that all men were filled with a thirst to know. Long fields had failed to yield as in years past, that hours after the city slept lights burned in the vineyards and orchards had produced only imwindows of scientists and, even after these perfect fruit; so the King issued a proclamabeacons had been turned low, the :flame of tion offering a great reward to the man who unanswered questions glowed in restless produced the largest crop the next year. minds . Tongues wagged and curtains were placed in

Nor was this quest confined to men of sci- shed windows as all the men of the villages ence. In shops along the busy streets the butch- experimented with new fertilizers. The butcher worked with blood-stained hands over still er ground his bones and scraps of meat, the pulsing organs and wrote on wrapping paper smithy saved the ashes from his fire and all what he hoped would contain a clue to the were put in bags and secret hiding places to mystery of life and death; a smithy weighed await another spring. the powdered ash of burnt-out coals and asked Less moved to new attempts than those if that force which melted iron had physical around him was a certain man of the soil who being. Even the corporal of the King's guard lived in a small village where he was marked drew diagrams of strange, new weapons in by those who knew him as a man of ceaseless the dust by the palace gate-and in that dust energy rather than profound philosophies. there lay a weapon deadlier than those he · Not that Theman was without ambition but drew. the earth is a jealous wench, kind alone to

All through the land the drudgery of daily those who serve her constantly and, when tasks was done in haste so minds might sooner there are few to do it, the common tasks beturn to realms of tantalizing thought. On the come important. Thus it was that the great rough boards of tavern tables fingers, grimed popularity of abstract thought had brought to and gnarled by work, drew cabalistic marks in Theman many who were willing to buy his the damp of tankard rings, while underfoot grain that they might have more time to think the dust of idle fields gritted a dull protest at and many others who were willing to think dead things left unburied and of buried things that they might buy another man's grain.

[ 20}

With so much to be done, and done by him alone, Theman had but little time to turn to thoughts of Kingly proclamations . Instead, as the greater numbers of his neighbors began to work in secret and to cultivate small testing gardens, Theman found himself hard pressed to supply the increased demand on his storehouse. So, while others planted boxes of earth in secret rooms, he made plans to tear down his boundary walls and till his unplowed ground.

As the long grey winter drew to a close and the last of the granaries were opened to the higher bidders, the tap rooms were filled with rumors from the farthest province of better methods and new seeds of miraculous yield. Secretly, with great haste a score of messengers were sent from every town by those who were sure that, with their perfected methods, these strange new seeds would bring to them the prize. And Theman bought for very little the seed grain of his neighbors.

turned back to mending bags and building larger bins.

In the weeks that passed each shoot of green that grew in Theman ' s fields cast a shadow of anxiety over the hearts of those who waited word from their messengers. The journey was long but time was short and even miracle seed must be planted, germinate and grow.

With the coming of spring, a host of be- One day as Theman sharpened his scythe a witching odours arose from the warming messenger rode along the road toward the inn . earth, and those who worked with foul messes Like wildfire the story spread, and those whose in gloomy sheds were all too glad to lay down emissaries had not yet been heard from were their trowels and wait for the strange new appalled by the news. Until recently in the seeds. They wandered over all the fields that distant province but little grain had been they were going to reap and watched with ill grown. For many years its inhabitants had concealed smiles the solitary figure of Theman depended on the lands to the north for grain as he cleared the ground, followed his buck- but, with the spread of great research into ing plow, and sowed the common seed in soil those provinces, they had been forced to till where only trees had grown and cattle grazed. their own lands and shut down the mines

With time the heat grew more intense, and which had fed them in the past. Great indeed men who followed a vision over their lands was the progress made by this mining nation were as content as he, who walked behind his turned to the soil and their crops were larger plow and sweating team, to leave the field and every year-miraculous to them but poor comprepare for what would come. While his pared to even the poorest seed his neighbors neighbors fretfully stirred their crates of fer- had sold to Theman. tile compounds, Theman looked out over the Gone were the smiles of Theman ' s neighcorrugated acres, where slanting lines of rain bors, forgotten were their fertilizers in th e sketched in the crops that were to be, and then mad rush for plows and seed. From dawn ' til [ 21}

after dark they worked in feverish haste. Each province after province was entered, crossed, rising sun saw sleepy men toiling in the fields and left. The King and his company were as though to wrest by sheer brute force a har- staging a grand review and, in the midst of it vest from the ground. In Theman's fields he all, the winner of the contest was all but fortoo worked hard from dawn to dusk, for vir- gotten. gin soil, so newly turned by iron share, had As there are among men those who delight stirred as if in sleep and with all the vigour of in giving banquets on any occasion where the youth thrust up green arms in a stretch of host can hold the center of the stage, the King wakening strength. The same sun which but briefly mentioned the fine crop grown by burned the other furrows black turned The- one of his subjects and passed on to dwell on man's grain a golden brown and swelled to the beneficence of his rule, leaving Theman bursting every ear, so that, as the days grew to do as he wished in the towns they visited. near for the arrival of the King, Theman's While the main body of the King's company bins alone were filled. flowed like a great river down the central At last the day arrived when all the village street, Theman, having heard the monarch's should have been prepared to greet the royal words before, wandered along narrow side party. As it moved along the village streets a streets and into courts where strangers seldom great number of people blocked the trumpet- came. Untaught as to the numerous differer's way for a crowd had gathered-but out- ences separating men, Theman spoke to those side Theman's house. The King wondered he met in the simple manner of his own village greatly at the sea of faces that were turned and, to those who reminded him of his old toward his carriage but he was more amazed friends, he talked of seed and weather and to see it surge away from him toward the door taxes. Often he was struck by the similarity where Theman was selling grain. between the innkeeper here and the blackHunger levels even royalty and respect for smith there and, seeing the likenesses he began royalty is a poor substitute for bread. The to see the differences. king drew near, disdainfully, for common peo- This society of men is capable of strange inple, though they be strong enough to support versions. A festering wound on a man ' s body a king, are in some ways too strong for a king is opened, drained, and exercised until it beto bear. Then even he was constrained to join comes well, but the leprous faults on the face the mob in their homage to Theman, for never of the earth are hidden, shut off and indigin all his inspection of the provinces had he nantly denied while their poisons numb the ever seen so great or fine a harvest-and al- very farthest reach of life. ready its owner had been selling for hours. In the fields on either side of the main high -

way all the pride of the guilds was exhibited. At first Theman was reluctant to leave his The fattest pig, the most productive cow, the work but the acceptance of the position as finest handiworks of pen, brush, and tool were Lord of the Granaries involved a visit and pos- arranged to their best display. These things sibly residence in the capitol. Leaving home the King saw. and farm in the care of his nearest friend, In the tributary streets where Theman walkTheman gathered his few belongings and rode ed was filth the pig would have disdained and in bewildered state after the carriage of the stair-stepped hosts of children that would King as it made its majestic way from town have put the most productive cow to shame. to town. Days passed and borders fell behind, Here, in courts where sunlight seldom ven[ 22]

tured, mockeries of human handiwork snored in sodden oblivion or stole in stealthy preservation from those who slept. These things Theman saw and over the narrow streets hung an odour that was haunting! y familiar until he finally remembered the reeking mixtures concocted in the sheds of his village neighbors, for here the dust was damp and seemed to move.

Greatness is a force} not a goal. That relentless inner drive which carries men to heights lies dormant, seed-like in the chosen few, only waiting the warmth of opportunity to start the upward climb. Mighty waters may be held in check for a short time but, once the breach appears, they flow with ever increasing power through any bed with equal ease, only seeking an outlet for their pent up energy. So it must have been with Theman.

A preoccupation with elemental things had given him perspective and from the earth he drew a sense of strength, of faith in things unseen. Too busy to become narrow, too sincere to become cunning, Theman faced the things he saw with nature as a norm; and first felt, then reasoned that such things were wrong.

Long weeks passed and even the King grew tired of the same cheers in different throats. Even longer weeks passed for Theman as in his mind there stirred an unaccustomed restlessness and it was with anticipation that he turned with the procession toward the capital city.

As rapidly as the King tired of his new experience so he tired of Theman and, as a child turns to other toys yet keeps the old ones near at hand, so he hurriedly signed a set of papers which gave to Theman certain privileges. No doubt his Majesty completely forgot the man whose pension he had granted but, once set in motion, the laws of cause and effect have a way of doing unexpected things.

In his little room in a palace tower Theman's very existence was probably unknown to all but a few, for a successful ruler has many boons to grant and pensions are widely favored as a means of obligating as well as fulfilling obligations. The treasury clerk who honored Theman's modest requests knew him, as did the servants who once moved him nearer the royal library but, on a whole, he himself was too busy tapping new found storehouses of learning to spend much time in cultivating official favor.

Years passed and, haunted by a vision of things undone, Theman studied and worked in undusted alcoves of forgotten knowledge. Fascinated as he was by the problems of history, of alchemy, of the stars and the men who live under them he nevertheless was closest drawn to medicine.

The King and his court had long forgotten most of what they'd seen on their journey through the land, but each new discovery etched still more vivid memories in Theman's mind. Perhaps the answer lies in what they saw, perhaps in how they saw it, but, while Theman studied and the King reigned, other things than memories stirred.

No one ever knew just where it started or how many lives it claimed before the news had spread, but, as Theman had predicted in many futile, f ervant pleas for change, disease rode rampant in the country. Out of the squallid slums it came; nursed by the dark of ignorance it grew, sweeping alike before it those into whose midsts it had been born and those by whose avarice and greed it had been conceived.

Great as was the toll in crowded streets where death and suffering had always been well known, real consternation struck only when, leaping barriers of position and influence, the scourge laid hold of those who had heretofore looked with detached pity from the

23]

safety of the King's court. Lovely ladies grew pale with fear when, reaching for some article of feminine adornment, their fingers touched the table inches from the intended spot. Veteran soldiers and diplomats of matchless suavity felt cold terror rake their souls when they too recognized the dreaded symptom of lost coordination which preceded the slow disintegration of nerve fibers.

As might have been expected, fabulous rewards were offered to anyone who could discover a cure but, even as the shaking hands of Midas bruised themselves on unwanted gold, so the lords of the treasury were acutely conscious of the worthlessness of all they had to offer.

Night and day a frenzied activity gripped the nation. Overnight life's bitterest rivals were allied in fighting a common enemy, death; and still the air was rent with screams from stretcher bearers who, in the very act of carrying unburied dead, were stricken by the twisting agonies of shattered nerves. Was it any wonder that the first discovery was hailed with so much hope?

At the beginning of the plague Theman had found an unfamiliar figure stooped over the tomes so long deserted but for himself. In the extremity of his despair, the talented but pampered physician to the King had turned again to the laboratory from which he had been called by social aspiration. Hours of comparison and days of fruitless experimentation resulted in little progress until one day a startling phenomenon was observed. The cases with which they were working stopped dying. Apparently a specific had been found which, as the impatient doctor looked on, Theman discovered destroyed some parts of sight and hearing. Feeling that he was on the verge of isolating a perfect cure, Theman begged to be allowed to purify the drug before it was given to a suffering world. Beyond a certain point, no drug could save and, before that, however

slightly advanced the stage of the malady, the administration of the drug destroyed the sense of color and of all but a bare octave of sound. But no reasoning could convince the King's physician, and that evening, while Theman feverishly worked with the end in sight, an impatient man gave to the world "his" wonderful elixir.

Values are flexible qualities as the nation soon found out. Scarcely a man, who a short year ago would have been loathe to lose a single sense, but who now clamored for the privilege of trading a spectrum of color and a scale of notes for life. The King, humbled by the magnitude of the tragedy around him had put all resources into the hands of his physician in order that the elixir might be available to all who sought it. By the thousands they were treated and Theman sought audience with the King. He had found a new derivative which saved not only life but all the senses with it.

Yet even the triumph of his discovery was alloyed by the bitterness of something he had observed in his experiments. When color sense and hearing were impaired the defect became hereditary. So strong an action could easily be true, for, as the finest bit of metal succumbs to the heat of smelting, so the same force which dulled the individual organ destroyed forever that little bit of potentiality in the generation yet unborn. And yet audience was denied him with the King.

Back to his native village Theman journeyed with all haste, carrying with him apparatus and his precious distillate. Even the desolation and despair along the road had hardly prepared him for the wrenching sight of familiar places grotesquely the same and old friends weirdly changed. To his ears as he walked along his weary road had come the dull, dead monotone of the speaking dumb and his heart was made more sad because he

24]

held in his hand the thing which could have saved them.

At every place he stopped and often when he first began his march he offered his remedy to those not already stricken. Suspicious glances turned to hatred when differences were seen between that which he had to offer and the thing they had been told would save them, so that, as he drew nearer to his own village he spoke but little and bent all his efforts toward reaching and helping those he knew and loved.

The first of his former friends to see him greeted him in the detached manner of one from whom bitter experience has stripped all capacity for emotion, and in the lifeless tone of one beyond his help. To this man he had entrusted his farm and home long ago before he left the town. Him he had particularly wanted to save. Sorrowfully, Theman gathered about him a small group who knew him and began his story in simple manner, always careful to keep his voice within their narrowed range of hearing. Earnestly he pled that they bring to him all their families not too far stricken by the plague but, as they and their fathers had waited long years before for other grain, so now they waited only another supply of the standard drug. "Why don't you cure the steward of your house?" they asked and at his reply of "too far gone" they laughed and muttered warnings to him to "stick to raising bumper crops of grain."

After a while even their laughter stopped and, while Theman moved from place to place on his many futile visits between the palace and his village, he heard rumors of a new philosophy which had arisen. Rumors that spread and gained in force and more people accepted the new belief.

Based on the evidences of their now imperfect senses men had begun to wonder, desultorily at first, if perhaps there might not have been an error in the idea of colors and musical

sounds. Man has always relied greatly on his too imperfect body and here, as always unwilling to admit that the fault might lie in them, men were building up new doctrines to suit their changing grasps.

It was a comforting thought to feel that sense of rightness and, for every isolated man that Theman saved, a thousand others scoffed and showed their disbelief by the destruction of paintings, music, and instruments "in honor of the new revelation. "

And so it was that in the twilight of his life Theman gathered together his little band and, carrying all the treasures they could salvage from the smoking monuments of men's conceit, they traced again a portion of the journey Theman's feet had walked so long before. On and on they traveled, jeered at and ignored, until at last they reached the rocky heights of primeval crags. Here, on the brink of a rugged cliff, Theman sat silhouetted against the purple sky, watching a moving shaft of light trace crimson staffs on which the last silver notes of birds' songs hung as the sun went down on a cold, grey world that refused to see or hear.

@ @ Why ask you then for happiness?

i You'd not be happy in Elysian fields-

@ @ Why ask you then fot happiness?

@ @ 'Tis not for you.

@ @ Happiness is for the irresolute;

i

@ @ y OU are resolute.

Happiness is finite in its end,

@ @ And you are infinite.

i Why ask you then for happiness?

@ @

ETHEL O'BRIEN.

@ The landscape weeps in Beauty's rapture rare,

@ And wild geese sing dirges to the sky-

i I look within my heart to :find it only bare, i

@ Nothing lingers except a half-choked sigh.

@ @ It is like elfish gold, and never can be real, i i This sad and tender melancholy in your eyes,

@ You are pretending, to torment me and to feel

@ A sudden surge of joy at my surprise. @ i i

I have been loved before, and it will come

@ agam,

@ Perhaps not with your lilt and careless grace- i i But now I :find a comfort in the rain i i

@ Because it sweeps away the mem'ry of you r

@ face.

@

@ @ @ @ i @

KIRANICHOLSKY.

ByW.MANER

Palmetto Beach is one of those scrubby growths that are so very common up and down the South Carolina Shore, springing up along the edges of the backwaters which form the Inland Waterway. None of them have beaches. A short stretch of sand and grey clay, overgrown with patches of marsh grass is all that they can lay claim to. Palmetto Beach is no exception. A few scrub oaks, a couple of young pines, and a row of palmetto trees waving along the edge of the water were all there was to start with. These and some flat fields. A few cottages had been built some years before, and later someone had had the idea of

of trees in the community. Mr. Joe Jones was the first inhabitant of Palmetto Beach in the spring, and was the last to leave when the summer was over. His was the first house built there, and he took particular pride in his own private strip of beach. The elect among the rest of the colony were given the special privilege of floating up and down in front of his house in the sacred Joe Jones waters. Theirs was the special privilege of using his dock to set sail from and sun bathe upon. Mr. Joe Jones lay in his hammock stretched between palmetto trees and surveyed his kingdom with much relish. developing it as a summer resort. More small The bourgeois cavorted on the rest of the houses had been built, and families took them beach. Here there was no line of palm trees; over for the summer. just a few scattered specimens which had

There was no elaborate life at Palmetto grown there by mistake. Here everybody Beach. The men wandered about in bathing shared the same pier. Here the beach was not trunks or khaki shorts and paper sun helmets; so well kept. Here the Gays swam. the women, whether sixteen or sixty wore The Gays were other old settlers, and were cotton shorts and scanty tops, and topped their responsible for the construction of many of costumes off with large rough straw hats. All the houses and the development of the place of them developed nice cases of sunburn after as a summer retreat. Their residence was a the second day. Their noses turned red and large barn-like structure, which, according to peeled, and their arms and legs glowed from a faded sign posted above the front door, was too much sun. called Gay-Joy. Gay-Joy was referred to by the Their life was routine. Going to town for rest of the beach as the Hotel. For th~ Gays the daily mail and fifty pounds of ice, swim- used Gay-Joy as a spot for entertaining weekming when the tide was in and fishing or crab- end parties who paid for their board and keep, bing when the tide was out, and gorging them- and Gay-Joy was apt to live up to its name a selves with seafood all the time. Once or twice bit too often to please the rest of the beach. a week they put on all their clothes and went Mr. Joe Jones did not like the Gays or Gayto Savannah for the day. Joy. He thought it not becoming the atmos Mr. Joe Jones was an exception. He never phere which he tried to develop at Palmetto went out in the sun if he could help it, he wore Beach. In Mr. Joe Jones' daily promenade up all of his clothes all the time, and his house and down the length of the beach, he always was set apart in the only considerable growth frowned and looked the other way when he [ 27]

passed Gay-Joy. He had been doing this for twenty years.

The Gays didn't give a damn. They were a party of three; Mrs. Gay (Tonie she was to everybody after the second day), her daughter Lilly (who had labored through the successive stages of Lillie, Lily, and Lilye before she had arrived at her eighteenth anniversary), and her son Harry. Harry was just another Harry, and doesn't enter into this, since he was gainfully employed in the service of an oil company in Columbia. There had been a Mr. Gay at one time, but he had disappeared, not being able to stand Tonie's undiminished energy and gaiety. Tonie, in her infrequent references to him, called him "that man."

It was Tonie's custom to "chaperone" house parties of young people who came down for a week at a time. These young people, students at Carolina, Citadel and Coker were apt to be what the older inhabitants called unprincipled if given a free hand. And if there was one thing Tonie believed in, it was giving young people "plenty of string" as she told the other women who had not managed to see her coming and thus get out of sight. They couldn't exactly decide what it was that they didn't like about Tonie, because she certainly tried to be sociable. It may have been the parties at GayJoy, but there was really nothing to object to on that score, even though they did make a little noise late at night. That was all, as all the sons and daughters in the colony assured them. And they all went to Gay-Joy's parties.

Mr. Joe Jones, though he did not exactly like having the Gays around, could do nothing about it. They had been there as long as he had, and there the matter stood. He was content to ignore them completely and to fume outrageously to his family the morning after each party when he had been kept awake by the noise from the the radio at Gay-Joy. He could, however, forbid his son to go there, and this he did, to his own satisfaction and to

Joe Jones, Jr.'s annoyance, because it meant just one more thing to keep his father in the dark about.

The fact was, Joe, Jr. liked Lilly. And Lilly liked Joe, about as much as she liked any of the boys in the crowd. And Lilly wasn't partial. There wasn't anything she would do for one of them that she wouldn't do for the rest.

One night somebody dropped a lighted cigarette on a studio couch and there was a bit of excitement when somebody tried to douse the fire with half a bottle of gin. This broke up the party to some extent, because it was all the gin that was left, and they couldn't get anymore until the next day. When Mr. Joe Jones heard about the fire, he just grunted and said he wished the place had burned to the ground.

The next morning Tonie was called back home to attend the last rites of her grandmother, a worthy old patriarch of ninety-seven who had control of all the remaining property in the family, and on whose grudging support the Gays were dependent for sustenance.

Given a free hand, the guests at Gay-Joy planned another celebration to make up for the fiasco of the night before. There had been parties at Gay-Joy before, but this one surpassed them all. Previous parties had been passed off at breakfast with a light comment by the rest of the Beach, but this one was going to be remembered and spoken of in hushed tones for years. It was what the participants afterwards referred to as a "stinker." A carload of kids came up on the special invitation of Lilly, and things got underway early. This time there was no scarcity of gin. By midnight everybody was rowdy drunk, as only college crowds can get rowdy drunk, and the rest of the colony was beginning to notice things.

Mr. Joe Jones heard the noise, too, and fumed. He boiled up and down his screen porch, silently but vociferously cursing the fate which had brought the Gays to Palmetto

[ 28]

Beach. Why in hell, he wondered, hadn't the place burned down the night before when it had the chance. Then he'd be rid of such people. His anger mounted to such a pitch that he had to do something, and the natural thing was to stomp off in the direction of Gay-Joy, vengeance bent. He did just that.

At the same time that Mr. Joe Jones was pacing up and down, things were happening at Gay-Joy. The first casualties of the evening had occurred. Two boys from Savannah had passed out over a hammock, and a girl from Columbia was being violently sick in the kitchen. A great discussion had arisen around the two on the hammock, and hazy efforts were being made to wake them up. Finally somebody suggested fresh sea air. Somebody hauled the girl out of the kitchen, and the entire party stormed down to the beach, ready to put out to sea to find some fresh air.

Amid the confusion on the beach, no one noticed Mr. Joe Jones as he stomped up to Gay-Joy's front door. He slammed through the screen door and into the house. There was no one there. He slammed his way through the dining room, the kitchen, and out into the hall, where he came to a sudden stop when he

opened a door which turned out to be a closet. This was but a momentary delay, and then he picked the next door. This led into a bedroom.

Joe Jr. and Lilly had not gone down to the beach with the rest of the crowd.

It was a few minutes later that one of GayJoy's neighbors noticed the flames glittering through the kitchen window. At first she paid no attention, but soon it was too insistent to ignore, and she was sure it was fire.

After the fire got started, there was no stopping it. The flames crunched the dry timber of the lightly built house like it was paper, and before it was under control the roofs of two adjoining cottages had perished. The neighbors made an attempt at dousing the fire, but soon they found it was no use. They spent their time trying to clear out their own cottages, in case they caught too.

Mr. Joe Jones sat on the ground, his back against a palm tree, and watched the fire. After a while he got up and went down to the water's edge to wash his hands. He rubbed them with sand, and then rinsed them off. But when he sniffed them, they still smelled like kerosene.

By HENRIETTA SADLER

He was just ready for bed when a car stopped in front of his house. Sagging a bit from weariness, he sighed as he saw a man carrying a child come through the tropical night. The man, tall, broad-shouldered, was hollow-eyed from worry and fatigue, for he had driven forty miles through the African night to bring the child to the little doctor.

" Dr. Hannington, my little girl has broken her arm. Our doctor is not in our station and- "

He got no further . Dr. Hannington took the child and carried her into the house.

"P-p-p" Dr. Hannington gave up with a shrug. He had never been able to control his stuttering. Although he couldn't express it, his swift sympathy illuminated his face.

He put the child into a deep chair, smiled, and placed a huge satin pillow on her lap. He picked up three kittens from their basket in the corner and put them on the pillow. The child was so busy trying to keep the kittens from falling off the satin pillow she forgot that her arm was being set-at least, almost.

Her father, greatly relieved, walked beside Dr. Hannington as he carried the child back to the car. He towered above the doctor and yet felt so much smaller. The great tenderness of the little man lifted a hand to sooth all trou - · bled hearts that night.

The car moved away. Dr. Hannington lifted his face to the brilliant stars. They seemed to be trying to burst through the veil of night, so eager were the y to shine. The doctor turned to his house, his light, and his kittens.

The next day the doctor drove those forty miles over African roads to see the child. At dinner he sat beside her and cut her meat. He

[ 30}

smiled at her with that ever young but tired grin. She felt so near to him that she curled close to his side and told him of her fairy kingdom.

"Down in the orchard there's a tree-the one I fell from and broke my arm. My fairies live there. I'm the fairy queen and I tell them to put the dew on the flowers and help the bees gather honey. I take some cake up there sometimes when Cook's not looking. We have a feast and the ants come and take the crumbs away to the sick fairies who couldn't come to the party. Sometimes I take Kitty up with me . She helps me rule, too. Although she's rather hard on the grass fairies 'cause they made friends with the mice. Would you like to see my kingdom?"

· The little doctor and the child walked through the orchard. The trees were in bloom. A light wind blew some petals from the orange blossoms and covered them with a white fragrance. They came to the tree and the child stopped him.

' T d better go first. Strangers sometimes frighten them ." She peered around the tree whispering softly under her breath to quiet her tiny subjects . The doctor watched. Then she nodded. He came and looked up into the thick branches of the tree.

"What a wonderful kingdom! I think I have fairy subjects too. But I've forgotten their fairy names."

Years passed, the fairies slipped away from the child and in their place came some of the realities of life The little doctor continued his work. One day he was called from his tiny laboratory by a native runner. The man was almost dropping from exhaustion.

"Doctor ... white man in bush ... blackwater fever."

The doctor _ turned swiftly to gather his medicines, shouted to the camp boy to get the camp equipment and turned back to the runner-"Where?"

In a lonely plain two hundred miles from any other human being he found his patient. The grass was over the doctor ' s head and the wind rushed through leaving behind a whistling moan. The patient was too ill to realize that help had finally come. Two weeks the little doctor worked. One morning he saw the ill man open his eyes and ask for a cup of tea.

Dr. Hannington began to train the camp boy to take care of his master during his convalescence. But as the little doctor was about to turn his face toward his tiny laboratory he too was stricken with the dread African fever. Too ill to take care of himself he lay on his camp bed watching the tall grasses in the moonlight cut snaky shadows on the tent top.

In the hour of hush before the rising of the

sun when all nature waited breathlessly for the miracle of light-he slept. The birds began to twitter and a soft breeze slipped through the grass. The new-born sun poked inquiring fingers into the tent. There they found a man sleeping. In the wrinkles around his mouth was the ever young, yet tired, grin. The thrust of his chin was that of a victor. The little doctor slept on and on. They buried him there in the middle of that plain. The stone they erected was simple:

H. H. Hannington, M.D.

Died while on duty.