DOLORES DEL RIO* tells why it's good business for her to smoke Luckies

"That $50,000 insurance is a studio precaution against my holding up a picture," says Miss Del Rio. "So I take no chances on an irritated throat. No matter how much I use my voice in acting, I always find Luckies gentle."

They will he gentle on your throat, too. Here's why Luckies' exclusive "Toasting" process expels certain harsh irritants found in all tobacco. This makes Luckies' fine tobaccos even finer ... a light smoke.

Sworn records show that among independent tobacco experts-men who know tobacco and its qualities - Luckies have twice as many exclusive smokers as all other cigarettes combined.

WITH MEN WHO KNOW TOBACCO BEST

1 _~, - IT'S LUCKIES - 2 TO 1

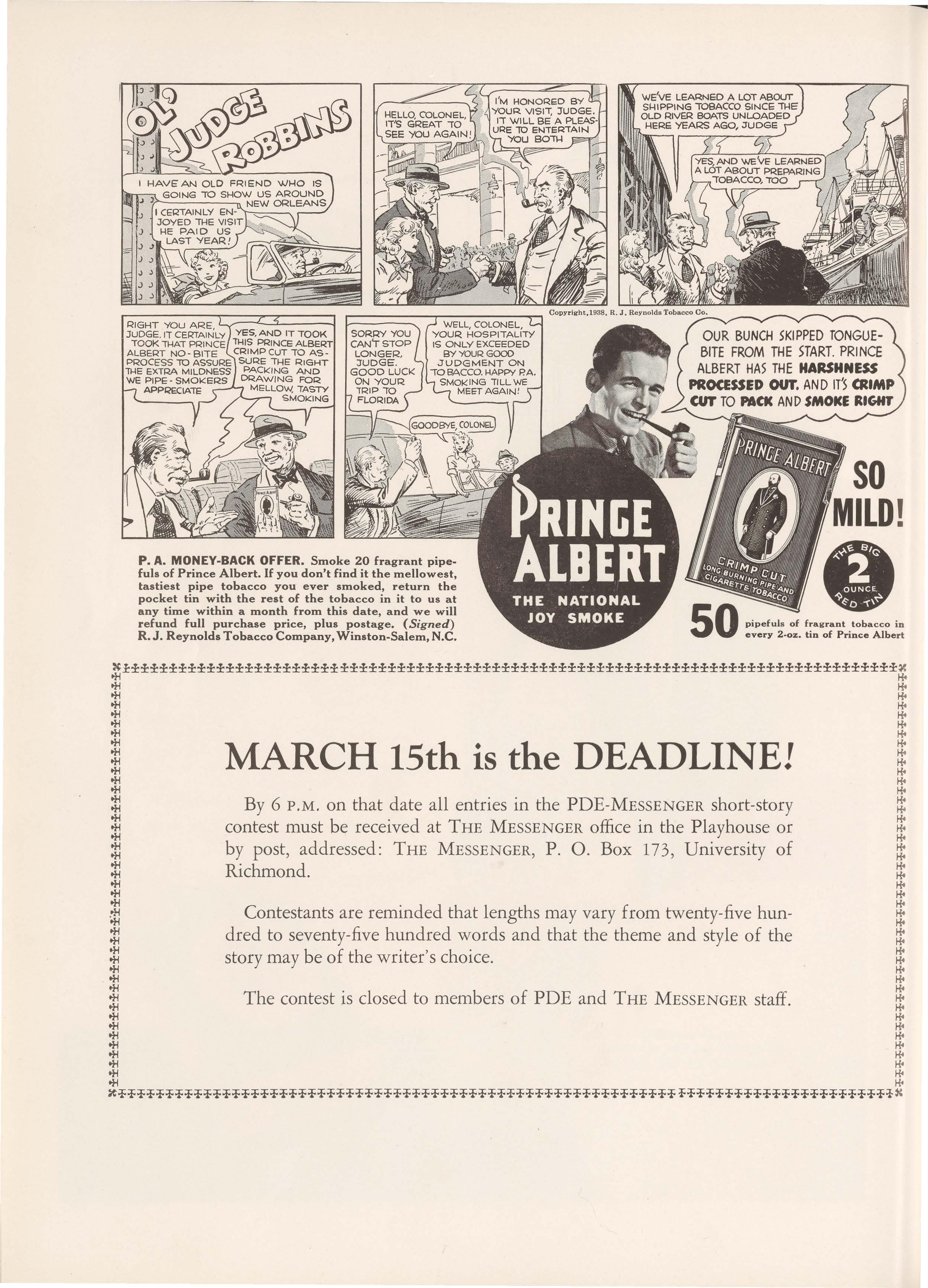

P.A. MONEY-BACKOFFER. Smoke 20 fragrant pipe• fuls of Prince Albert. If you don't find it the mellowest, tastiest pipe tobacco you ever smoked, return the pocket tin with the rest of the tobacco in it to us at any time within a month from this date, and we will refund full purchase price, plus postage. (Signed) R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Winston-Salem, N.C.

By 6 P.M. on that date all entries in the PDE-MESSENGERshort-story

contest must be received at THE MESSENGERoffice in the Playhouse or

by post, addressed: THE MESSENGER,P . 0. Box 173, University of

Richmond.

Contestants are reminded that lengths may vary from twenty-five hun-

dred to seventy-five hundred words and that the theme and style of the

story may be of the writer's choice.

The contest is closed to members of PDE and THE MESSENGERstaff.

-=<:><:><:><::Y<::YCYCY:;:y<:;:y<:;:y<:;::-o,,<:;::-o,,<:;::-o,,<~~=',<=',<=',<:--,.<:--,.<',.<',.<',.<--..<'--..<'-.,,,-C---.<'---.<----.~

GEORGE SCHEER , Editor-in-Chief; J. H KELLOGG, Richmond College Editor; LAVIN!:\ : WINSTON , ]11/esth a mpton College Editor; STUART GRAHAM, PAUL SAUNIER, JR., ROYALL BRANDIS, MARTHA ELLIS, MARIE KEYSER, EUGENIA JOEL, Assistant Editors,· R. M. C.

: HARRIS, JR. , B11siness Manager; JOHN S. HARRIS, MILDRED HARRELL, Assistant Business : M anagers. 25c per issue; $ l.00 per year.

By ETHEL O'BRIEN

THE THINKER,sitting in his usual position on a granite rock, perceived an Old Man and a mule cart, slowly wending their way up the rocky slope. As the man and his mules drew nigh, there loomed into sight in the cart a gigantic pair of scales.

''Where are you going with your scales, Old Man?" queried the Thinker.

The Old Man smiled, 'Tm a peddler, young chap, an' this here pair o' scales is the last piece o' my wares. Fer nigh on seventy years now I've tried to sell 'em, but no one'll buy 'em."

"Are they broken, Old Man?"

"No, though I can't say as you might think they were, son."

"How so?" asked the Thinker.

The Old Man placed a heavy rock on the scales, but they did not move. "You see, son, these here scales don't weigh quantities; they weigh qualities. Only trouble is, I've never been able to find the right ones. Now I've gotta be gettin' along."

When the Old Man had disappeared from sight, the Thinker again became immersed in thought. "Qualities," he pondered. Then he cast his telescopic eyes far down into the valley, where a prosperous city lay. He gazed long at the sight of men, like ants, industriously building up and tearing down the rudiments of their civilization, and he saw that they all lacked the sense of quality. Above all, he noted that the lack of this sense of quality

find the 1lzinlce't,.$'till

was most apparent in their literature and art, for of course it is in literature and art that the weaknesses of a people's intellect must needs show up.

"Just why," he reflected, "did this people have no sense of quality, and therefore no sense of true art or true literature?" Then he bethought himself of a statement of Oscar Wilde's: "An age that has no criticism is either an age in which art is immobile, hieratic, and confined to the reproduction of formal forms, or an age that possesses no art at all. There has never been a creative age that has not been critical too."

"No criticism." This people in this age did not take the time or the trouble to criticize what they had produced. They were much too busy producing more of what had already been produced, much too smugly satisfied with themselves to allow for criticism.

The Thinker prepared to study the situation, but before he could collect all his materials, he received an order from the government commissioning him to figure up the approximate cost of gilding the lilies of the fields.

Meanwhile the Old Man had arrived at the city. His gigantic scales caused a sensation. No one was interested in the fact that they did not work; it was their size that mattered. The largest cigarette manufacturer in the country offered to rent them as an advertisement for his product. Amateur photographers flocked about them in an effort to make trick shots. The mayor invited the peddler to dinner, while the mayor's wife inveigled him into

1 J

speaking at the Ladies' Delphian Society on the following Tuesday. The Old Man smilingly agreed to all proposals, but the next morning when they went to look for him, he and his scales and his mules were gone.

Searching parties were immediately sent out in all directions, the wrong directions, of course, for the Old Man with his mules and his scales was quietly reposing under the shade of a huge elm tree at the end of the mayor's back yard.

"Qualities!" murmered the peddler. "Sure do wish I could find the right ones." He looked sadly at his scales as usual. Then he pulled a book out of his pocket.

"Picked this up off the mayor's parlor table, mules." He stroked one of the mule's nose.

"By a fellow named Bacon-seems as if I've heard of him somewheres before. It's a book o' essays. Says here in the front that this Bacon was born in 1560 an' died in 1626. King James o' England made him a knight 'cause he liked his writin' so much.

"Looka here, Jeff, on this page in the front where there's some sayin's o' people that've really studied him. Here's a Mr. Sidney Lee, who wrote a book on him. Says, 'for terseness and pithiness of expression there is nothing in English to match Bacon's style in the essays.'

That means, mules, he said a lot, but quicklike . . . 'his reflections on human life which he embodied there, his comments on human nature, especially on human infirmities, owe most of their force to the stimulating vigor which he breathed into English words.' . . .

An' that says that he jostled the words up so as to sort of reincarnate 'em.

"There's a Mr. Burke says, 'who is there, that upon hearing the name of Lord Bacon, does not instantly recognize everything of genius in the most profound, everything of

discovery the most penetrating, everything of observation on human life the most distinguished and refined.' "

The peddler pulled a hunk of chewing tobacco from his pocket and commenced to digress on his subject, all the while chewing contently.

"Says here, Sadie, what he did was to write down anything he thought had quality to it, -' cause he wrote other things too, on scientific an' religious subjects-then he divided the stuff into sets, an' sewed 'em up with his ideas-called 'em essays. There's one on truth, an' one on· adversity, an' one on atheism, an' here's one on studies. Let's read a little bit, mules. Says here: 'read not to contradict and confute; nor to believe and take for granted; nor to find talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider. Some books are to be tasted, others are to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested ... .' " Here he paused and chewed off another corner from his tobacco.

"There's a heap o' downright common sense in that hunk, mules. Just think o' the people that like to say a book's bad 'cause they think that makes 'em seem as if they were smart. An' take all these people that j es' read a book 'cause somebody else is readin' it. Jumpin' Jehosophat! Will you remember how everybody was readin' somethin' called Anthony Adverse an' somethin' else called Gone With The Wind last year? Then there's a heap o' people j es' read so as they can talk about it, or maybe so as they'll have somethin' to talk about. You know, Sadie, seems to me that they oughta post this sentence o' Bacon's on every bill board in the country, same's they do with those toothpaste ads. Guess your mind's j es' as important as your teeth.

"Gettin' down to this last part . . . 'to weigh and consider' in other words what [ 2]

you oughta do with a book is to put it on a set o' scales an' see if . . . Jumpin' Jehosophat! Maybe that's what I can use these scales fer!

"Will you look? Mules, will you look? It's amovin', by gum, it's amovin'. Say, where's that carse darn mayor? ... Ugh ... "

In his excitement, the Old Man nearly strangled himself on the cud of tobacco. Finally he managed to cough it up. Then, yelling for the mayor at the top of his lungs, he drove up to the house. But neither the mayor nor anyone else was there. Still shouting, the Old Man drove into the town, where the remnant of the befuddled searching party ran to him.

IV

"Looka here! Looka here, everybody!" He pointed to the scales in triumph. "They're aworkin'. I jes' put this book o' Bacon's on 'em, an' they started to work. I knew they'd weigh qualities, only I never would've found what qualities, if this here book hadn't told me. See, it says here: 'read not to contradict and confute; nor to believe and take for granted; nor to talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider.' To weigh and consider, that's the point!"

A young man with a shock of black hair sauntered up to the peddler and addressed him in bored tones.

"Old man, all Bacon is saying in that sentence is that we should criticize the literature we read."

"Seems to me, son, that that's a pretty good idee."

"My dear man, I am a poet. 1 am far too busy creating literature to waste time criticizing what other people write."

"And that's your trouble, Wilfred. I've always said you talked too much and thought too little. It's the same way with your writing -you write too much and read too little. Ask your mother if I haven't said that."

A stout matron with a determined look in her eye thrust herself through the crowd. After sending a triumphant look in the young man's direction, she turned to the peddler.

"Old man-I don't know your name-I've just been reading the most fascinating book. Here, I have it with me. I do think you ought to read it-Wilfred! Wilfred! Where are you going? Now you stay right here, young man . What I'm going to say partially concerns you. Goodness knows, I've put up with enough of your talk-even if you are my own nephew.

"Where was I? Oh, yes. This book-it's by Mary M. Colum. She's Irish, Mrs. Murphy. You wouldn't know her, would you? No? I thought you probably wouldn't. I guess Ireland is a pretty big place after all, even if it is only an island.

"Well, to get back to Mrs. Colum. She was brought up-here on page three she says it herself-'surrounded by writers, saturated in literature, rocked and dandled to its sounds and syllables.' My, that must have been lovely. Oh, er, then she studied abroad and wrote for the London-it tells on the fly-leaf-the London Nation and New Statesmen. Mr. Butler Yeats and Lord Alfred Douglas praised her work. Now, Wilfred, if you could get a Lord to praise your poems, instead of that love-sick girl of yours, I'd be quiet. The trouble with you is that all the girls tell you how poetic 1.n<l sensitive you are. Stuff and nonsense, all of it! Only time I've ever seen you sensitive is when it came to doing a little honest work. You don't even-oh, what's the use of talking to you?

"Let me see-where was I reading-oh, er -she joined the Abbey Theatre Group when she was in college, and afterwards married Padric Colum, who was a member of the group too I think that is so nice-the two of [3]

them working side by side, both interested in the same things. He writes poetry, and she criticizes it and inspires him to go on to greater heights."

The dear lady paused impressively so that her hearers might gather the full import of what she was saying.

"Mrs. Colum is regarded, on both sides of the Atlantic, as one of the leading contemporary critics. Now that is something to think about. Even over there in all those foreign countries people realize what a good critic she is.

"She writes in all the leading magazines and papers. Those of you who have read Scribner}s or the Forum must have seen some of her articles. I hadn't noticed them, but after I read this book, I looked them up. Oh, yes, she writes for the New Yark Herald Tribune too. Which reminds me-we have that in the library, you know. I happened to pick it up just a few weeks ago-that's why I read this book. A Mr. Carl Van Doren wrote the most fascinating review of it in the book section. Here, I have that with me, too-I'm preparing a little paper on it for the West End Women's Delphian Society-This is what he says about Mrs. Colum: 'All her criticism has the quality of light. She perceives and reasons with equal sureness.' Isn't that . . . "

The peddler stopped this flow of words for amoment by nudging her.

"What would be the name of the book you're talkin' about, ma'am?"

"O, dear me!-did I forget-It's called From These Roots.

"Now Wilfred, this is what I wanted you to hear. It's on page two of her book. 'It is not the form or character which is the decisive factor in determining whether any kind of writing is creative literature or not-it is the mind-(Wilfred )-behind it.'

"Then she goes on to say that that is the main trouble with American literature. Here, I'll read it: To produce works like Main Street or An American Tragedy a criticism is needed, but an even deeper criticism is needed before we can produce works like "Kubla Khan" or the "Ode To A Nightingale," or Faust! or Les Fleurs Du Mal/

"Wilfred, I know I have been picking on you, but, well, you are my own nephew, and I think you have a certain amount of sense, even though you do your best to conceal it. Now, why can't you profit by this and really write something that your family won't be ashamed. of?"

"Matildy! Matildy!"

"Yes, Mrs. Taylor, did you want to say something?"

An apologetic looking little woman in a grey suit stepped up to the front of the group.

• "If you don't mind, Matildy, I was just thinking of the report I read last week to the East End Ladies' Delphian Society on Dorthea Brande's Letters to Phillipa and Mr. Joseph Wood Krutch's Experience and Art. I don't think the West End Delphians have gotten around to discussing them yet, so you'll excuse me, if I say a few words, Matildy? Thank you.

"Well, Mr. Krutch says he thinks the criticism of literature shouldn't be thought of as a science because science states positive, unprejudiced facts, and criticism can hardly be unprejudiced. There's one sentence in particular that I remember. Mr. Krutch says: 'Criticism rationalizes and gives temporary form to our experiences with literature, just as literature rationalizes and gives temporary form to our experiences, with nature.'

"Don't you think that is nicely put, Matildy? Of course-the rest of you as well"Now Miss Brande in Letters to Phillipa [4]

was trying to show her god-daughter what you're trying to show Wilfred, Matildy. She says what we older people ought to do is to make ourselves good enough critics so as to be able to tell our young folks what is the matter with books they read. Young people are so inquisitive now-a-days. It's not enough to tell them a book isn't good, you have to tell them what's wrong with it.

"Thank you, Matildy-and ladies and gentlemen, of course."

"Thank you, Mrs. Taylor. I'm sure we all derived a great deal from what you said. And I do hope, Wilfred, that you will take the trouble to read Letters to Phillipa. I'm sure it would do you a lot of good.

"There's one more thing I want to say about Mrs. Colum's book, before I go. Here it is in the back. 'If enough disinterested and competent minds had devoted themselves to the development of new ideas in art . . . it would not have been possible for literature to have gotten itself into the rut it is in at the present time.'

"Ladies and gentlemen, I feel it is up to us! Wilfred, wait a minute, and I'll walk home with you.''

Sometime later when the Thinker had .finished his calculations for the government on the cost of gilding the lilies of the .fields, he again cast his eyes down into the city.

Much to his surprise, he saw the Old Man sitting on the mayor's front porch, contentedly chewing tobacco and reading a book. "He must have sold the scales," mused the Thinker, and he started to look for them. His attention was called to a loud bray. He saw the source in the city park. The sight that met his eyes was one to be wondered at exceedingly. For there, knee deep in clover, stood the old peddler's mules, brushed a glossy gray, with garlands of flowers around their necks. "Well," exclaimed the Thinker, a bit aghast. Then, letting his gaze wander about the city in search of other things, his eyes caught sight of the scales standing forth impressively in the market place. Looking closer, he saw that there was a book in each pan. Above one book was the inscription, "Lord Bacon adjured us to criticize," and above the other, "Mrs. Colum taught us how to criticize."

"Well," sighed the Thinker, "I suppose they really believe they've .figured out the problem.'' And he smiled. ., ., .,

These be Princely pearls Christ, dead Cresar, trusting most His enemies . . . Mother love . . . a friend . And Peace.

D.E. T.

By KIRA NICHOLSKY

WO THINGS so different, yet so alike; so far apart, so mutually near. The first a picture, ·akin to Corot's twilightsa misty, indefinite, spiritual beauty enwraps the scene; the second, you, whose strange, interesting face I cannot forget. Both have ethereal aloofness, strange, drawing fascination; both have a haunting melancholy, which is like a sad tune you cannot forget, and at times, when gay and sparkling laughter flows from your lips, you grow sad with remembrance. You would not want to be compared to such a picture, you would scoff, mock, and laugh at things you know are sacred, you, whose heart and soul yearn for beauty, cry out for, demand, claim it, draw it to you, absorb it, and throw away the sordid remains. You laugh because you care; you mock because you ache and hurt, because you cannot see how others can be so careless with beauty, so heedless of it. You are the proud heir of a gay, glittering, madly-moving world; you belong to those whose habit is to laugh. You laugh-I know there's heartbreak in it; I know the golden fields of grain, the careless clouds, the woodland ' s autumn glory, the seagull's wing across the setting sun, the white foam of salty spray, the blossoms trembling on a branch, are your own kingdom. Your fragile eyes, your sometimes elfish smile, give you away. No, do not laugh, that brittle meaningless jingle; you know, and knowing, please don't mock.

Should you pretend? Your friends aren't

[6)

real, they crave excitement, joy; they crave mad laughter, madder music, lights and noise, and gay and happy crowds. You want all those? But no, I know, for are you not a spiritual likeness of another? Another, whose ethereal , poetic beauty makes me weep, whose fascinating, elfish face I see before my eyes, as he bends down to touch a floating water lily, whose face I see so piteous, yet lovely as he looked down at blossoms trampled and carelessly flung by. You love those things; you love real things that will last ever, when your happy friends are gone, to find another they can laugh more with.

You like to walk in slow and slanting rain, you love strong wind, and gusts of winter storms, thunder and lightning zigzagging across the sky; you like soft lights and poems . You write small snatches, just to hide away. You love the twilight merging into night, that soft indefinite time, so short and fleeing soon. You like uncertainty and tainted skies reproach, the whispered secrets of the wind and howling torrents, steep mountain sides and sudden drops. You love all these, you love all beauty, you live in a gay, materialistic, thoughtless world. You fascinate me, draw me to you.

Your soft, caressing tones enchant and bring me visions of the worlds I know you know. Why do you shrink? Why do you hide it all behind an artificial , cynical laugh and a hypocrisy of thought? You can't deceive me, your eyes haunt me, and I know you-the sad aloof idealist, the mad enchanting elf.

By STUART GRAHAM

A SURVEY of some of the rules in Southern women's colleges is almost as amusing as a glance through the popu-

nunnery. From a modern viewpoint, however, college should prepare the girl for life, and the confines of a convent can hardly be said to afford such preparation. lar magazine feature, called "It's the Law," in which the author reminds us that in Willimantic, Connecticut, an ordinance decrees that a horse must carry a tail light when travelling after dark, and

that in Phoenix, Arizona, a law requires every man to wear pants when he comes to town. The college regulations seem far from humorous, however, to the girls who are forced to live under them-and, strange as it may seem ,to the layman, some incredible rules are strictly enforced.

Sociologists will tell you that such rules are excellent examples of what they term "cultural lag." In this they mean that the customs, mores, and general character of society have undergone profound changes, but that certain institutions and regulations have failed to keep pace. In such a case, affirm the sociologists, discord will inevitably occur. Mauve Decade rules won't work in a streamlined age.

Def enders of the present system will contend that strict regulations are needed in colleges, probably inferring that there is need for a present-day counterpart of the ancient

True, there are, undoubtedly, some mothers who like to feel that their "problem-child" '-· daughters are constantly under strict supervision and surveillance. Their senti-

ments are easily understandable, but college in the accepted sense is, or should be, quite another thing from a respectable reform school. One thing is certain -that the majority of mothers would not object if their daughters were allowed as much freedom as they enjoy at home. A single glance at the rules is sufficient to show that wholesale revision would be necessary to provide such freedom.

A sociologist would render a sweeping indictment against the strict regulations of Southern women's schools on still another ground. The increasing tendency for women college graduates to remain unmarried is a source of much worry to sociologists. They s.ee the cream of the race failing to reproduce its kind . They see the race dying out from the top . They place, and righteously, a good part of the blame for this on the schools themselves.

There are two reasons a girl doesn't marry: [ 7]

because she can't get a husband, or because she doesn't want one. The colleges, directly or indirectly, contribute to both these causes. The average age of a girl graduating from college is twenty-two, at which age half of the women in the United States are already married. Unless the girl, while in college, is allowed some freedom in making contacts with boys, she is at a distinct disadvantage in competing for a husband with other less restricted or younger girls, and this disadvantage increases progressively as the girl grows older. On the other hand, unless a girl is permitted to make contacts, she is likely to get the mistaken idea that she will be unable to find a mate of her own level, one ideally suited to her own intelligence and personality. She is likely to conclude that marriage is an unworthy state and that she should pass it up for the simpler alternative of following a career. Because of these considerations, colleges, which should, theoretically, be the best marriage marts, are instead unsurpassed spinster factories.

The generalities touched on thus far have been the object of much serious thought and research. It is well at this point, however, to pass on to particular sets of rules, rules that are sometimes so petty as to appear ridiculous, and sometimes so contrary to modern trends as to constitute a serious problem. For purposes of example, four typical Southern schools have been chosen. These institutions, while affording by no means a complete picture of the situation, still form a fairly accurate crosssection of outmoded regulatory systems.

The schools differ slightly in character. Westhampton, with which we are more or less familiar, is a coordinate school, a unit of the University, but, nevertheless, quite literally segregated from the other divisions. Harrisonburg State Teachers' College, at Harrisonburg, Virginia; is all that its name im-

plies: a larger school typical of most statemaintained teachers' colleges. St. Mary's is a fashionable boarding school and junior college in Raleigh, North Carolina, while Alabama College, at Montevallo, represents women's colleges in the deep South.

Facetious aspects of college regulations are quite evident in unwritten rules of the schools, as well as in those guiding principles embodied in handbooks. The interpretation of a Westhampton ruling which permits girls to attend afternoon athletic events on the Richmond College campus, but forbids conversation with boys, is a classic. If the boys persist in forcing conversation, the girls are instructed to say, politely and firmly, "I can't talk to you today. If it's important, wait until Friday."

In this, the hey-day of dancing as the social pastime, dancing prohibitions seem, to put it mildly, incongruous. Westhampton forbids all dancing on the first floor (just why location on the second or third floor makes dancing more acceptable is left for the reader to decide), while Harrisonburg does not permit students to dance in any public place in Harrisonburg or vicinity, nor in private homes in Harrisonburg, except homes of professors. Other tidbits gleaned from handbooks include: ( 1) at Alabama College, students arriving at or leaving school by bus or train must use a taxi (possible collusion between college officials and taxi company!); (2) at Alabama, students may not enter a store on Sunday, and may not even patronize a drug store or roadhouse, while riding on Sunday; (3) at Westhampton, students may not play jazz on the drawing room piano; ( 4) at Westhampton, students may not walk down by the lake, entertain back of the building, or in the Greek theatre after dark; (5) at St. Mary's, no pajamas may be worn under other clothes. Perhaps the best illustration of cultural lag [8]

lies in the regulations regarding automobile riding and chaperonage. In this age when automobiles far outnumber bathtubs, and the government is seriously considering stuffing a few chaperones for museum pieces, the rules on the books seem incredible. At W esthampton, girls may go riding with men only during daylight hours and only when accompanied by a senior or two juniors as chaperones-that is, after they have signed up for permission with the House President. Permission for riding before 6 P.M. (none is granted after!) at Harrisonburg must be obtained direct from the dean of women, unless the driver is a parent, faculty member, or woman in good standing with the college. Riding at Alabama college also requires chaperones in the person of two juniors or two seniors, and it must stop abruptly at 6. Students there may not sit in a car on campus or talk to young men who are sitting in cars.

Although increasing permissions granted girls for attending dances and other social or athletic events would indicate a gradual relaxing of rules, women college students still have just cause for complaint. At Alabama College, St. Mary's, and Harrisonburg, a visiting list must be filed in the dean's office at the beginning of the semester and the names thereupon approved by practically everyone from dean and parents to the dormitory janitor.

In a week in which there are no dance permissions, Westhampton freshmen may have, by actual count, three and a half hours of night dates Sophomores may have four hours, and juniors, six hours. These estimates include Sunday night dates, one hour of which must be spent in vespers. At Alabama the situation is even worse, freshmen and sophomores being

allowed only five dates, averaging two and one-half hours each, per month. Add to these figures one, or, at most, two, afternoon dates per week (none for freshmen!), and you have a complete picture of the dating situation. While it is generally true that seniors of most schools have unlimited dating privileges until 10 P.M., it must be remembered that dates must be kept within certain narrow, prescribed boundaries, and that dating facilities are generally deplorably inadequate.

The foregoing paragraphs have merely attempted to enumerate a series of undistorted, uncolored facts for consideration. As to what, if anything, can be done to remedy the conditions outlined, opinions will surely differ. It is the fond hope of the sociologist, however, that college authorities will follow the example of the old Romans, who, when they were unsuccessful in changing human nature by law, legislated to make human nature legal.

A flaming meteor blazes through the sky And night is day with the glory of its light. Then behold it into fragments fly And vanish from sight.

The brilliant green of leaves in June Upon an awakening tree in summer's early days

Is short lived, and vanishes soon In autumn fires' haze.

The life most beautiful is often one Which ends abruptly. Just memories remain. But is it not enough just to have spun A web of beauty in some brain?

-GILBERT SIEGEL.

or "All the W odd' s a stage, And Life's a vaudeville."

[ A comedy-drama in prologue and three acts J

By HENRY SNELLINGS, JR.

Prologue: The prologue shall consist of the voices of the stately Dramatia and the beautiful Historia, as they look down from Mount Olympus, surveying the result of their labors.

Man from his most pagan and primitive state has been essentially a dramatic creature The scenes of his action have not always been on the rostrum or before the footlights. In fact, some of history's ,most interesting scenes have been enacted backstage in real life. In Biblical days we see Abraham with his son Isaac laid out on a make-shift altar, ready to be sacrificed, when the voice of God instructed Abraham to spare his son. We are thrilled when we hear of the Carthaginian Queen Dido throwing herself on a burning pyre, because her Aeneas had left for other lands. Antony acted a part in a real play, when he said, "Friends, Romans, Countrymen." Nero, fiddling while Rome burns, has been the theme of many plays. Bocaccio's Decameron is good drama in any man's country, even if it was acted in a drawing room instead of on a stage. Once a cow got in a dramatic frame of mind and kicked over a lamp that started the great Chicago fire.

And men have received just as great a thrill in the make-believe of the theatre. The kings of France had their own private stage and kept

troops of actors in the palace. The great event of the guilds of the middle ages was their annual "morality" plays. In the days when Elizabethan sea-dogs were scouring the seven seas, the old Globe was filled to capacity whenever Bill Shakespeare or his confreres had an offering. Even the great George Washington delighted in playing "Cato" with his legendary love, Sally Cary.

This might be the general train of a conversation among the goddesses of Olympus.

SCENE: The old Richmond College on Lombardy Street. Perhaps in a raised corner of a basement storeroom.

College boys like to act. And Richmond College was near the famous Mozart Academy, the Hippodrome and Strand Theatres. So the boys of the down-town school early got the feel of gas footlights and drop scenery by gazing at old Joe Jefferson, Jeanne Eagles, and other thespians that we moderns know not of. Nationally famed "black-face artists" came to Richmond when the minstrel craze was sweeping the country. And it must have swept into sedate Richmond College, for the first time that we hear any mention of a formal drama on the campus was in 1897 when the Glee Club presented their widely acclaimed show. So enthusiastic were they that a small group got together and formed the "Mask and Wig Club" for that wicked pastime called "play acting." And to the present they have enjoyed a varied and checkered career.

At first their productions were presented on the small stage of old Thomas Hall. As their initial presentation the Mask and Wiggers offered a little French play called f ean Henri et la Pere. According to the Spider write-up, it was "enthusiastically received." By 1905 the organization was feeling its

[ 10]

age and, consequently, became a little more ton Colleges did most of the work connected conservative in its outlook. Therefore, it with the pageant, which was under the direcchanged its name to the matter-of-fact, "Dra- tion of Miss Emily Brown. The students were matic Club." But under this name it had an so impressed with her personally and ·her interesting and progressive life. In 1910 the methods that they asked her to help them with club put on its most ambitious production. their dramatic activities on the campus. She Presented in the auditorium of the Woman's had just returned from study in London and Club, it was the perennially popular Two New York and instilled in her embryo actors Gentlemen of Verona. Little scenery and few some of her own enthusiasm for the art of the lights were used, but it was a big success. theatre.

Moving out to the new campus at West- On the Playhouse stage (the small one behampton was just like getting established in a hind the arch on the present stage) that had new home, and in the melee dramatic interest in its day been a bandstand, a bar, and was tended to lag. And for several years there later to be a zoology lab, the Dramatic Club of wasn't much thespianic activity. 1916 offered Shaw's You Never Can Tell, 1916, however, saw a change. Legend, and and later The Magistrate. Dean May L. Keller the facts, so far as we can ascertain, say that and Professor R. B. Handy were active with on April 23 of that year, William Shake- this group. They did the preliminary work, speare had been dead three hundred years. So, and Miss Brown whipped the players into as a tercentenary memorial to the Bard of shape. Avon, a wave of Shakespearian festivals Previous to 1923, no definite schedule was spread over England and America. Richmond, followed for the presentation of plays. Whenalways classically fond of Shakespeare, had ever the boys felt - the urge to act coming on, her festival. From the newspaper and maga- they would get together and read over some zine articles of the period we see that it was plays and pick one that appealed to their masa great affair. No more appropriate setting culine tastes. Then probably Dr. R. C. Mccould be found than the beautiful University Danel, who was Ralph in those days, and secof Richmond campus. And so on a memorable retary of the Richmond Players, would stroll day, amid its lake and pines and Gothic build- across the lake (as we do now) and nonings, were scattered miniature Shakespearian chalantly approach Mary Weaver, a popular stages. On them different scenes from the Westhampton actress of that day. "Mary," he works of The Master were enacted. There was might have said, "What' cha say we give a a general admission fee to the grounds, and play?" "Sure, Ralph," she would reply, "We one was privileged to wander about as inclina- were just reading some plays over here. I've tion directed-laughing with Falstaff, rejoic- got a couple with me that we liked .... What ing in the love of Romeo and Juliet, or thrilled do you think of them?" And then the war with "Friends, Romans, Countrymen." It was would usually begin. For the boys and girls a full day. From morning 'til night, on every could seldom, if ever, agree as to what would part of the campus, young people could be make a good play. seen in strange costumes, presenting scenes Finally the case would be carried to Dean from Shakespeare's popular plays. Keller, who would discuss the suggested plays The students of Richmond and W esthamp- and then contact Miss Brown. With the final

[ 11}

selection made, the boys would be told in slightly more polished terms to take it or leave it. They usually took it, and the old Red Cross Building saw some corking good plays as the result, or so say the Collegian reviews and the old grads, who made their histrionic overtures there.

But this was no way for an up-and-coming organization to work, so "the curtain comes down on the first act of the Little Theatre across the lake."

SCENE: Let us! for convenience sake! say the Westhampton Blue Room! the Red Cross Building! and the far-famed ( and cursed) Playhouse.

It was fall of '23, and Miss Brown, who was living on the campus that year, approached the dramatic organizations on each side of the lake with the idea that they join forces and try working as one. The boys and girls were overjoyed at the idea, and proceeded with plans for the organization. All, however, was not "a bed of roses." There were many obstacles and prejudices to overcome, for never since the founding of Westhampton College had there been a mixed group. It was unheard of. Why, boys and girls meeting together in the same organization! But the voice of liberals prevailed, and the University of Richmond Players was established. (Though, even here, the authorities stipulated that there should be an alternate Richmond College president and a Westhampton vice-president and vice versa. As the barriers against combined organizations were dropped, this proviso became a dead letter.)

So in the splintery Red Cross Building, with no scenery and tin-can lights, the new organization went to work with renewed vrgor. It undertook many productions, and

enthusiasm ran high. Among the plays seeing their inception during this period were: Merely Mary Ann! You Never Can Tell! Feast of the Red Barn! Alice Sit by the Fire! South Sea Dust! Lady Frederick! Bidders! Dover Road! Grumpy! Milestones. The Wonder Hat! Romeo and f uliet! and The Merchant of Venice! were presented in the cloister of Ryland Hall or Richmond College Administration Building as part of the annual commencement program. Great preparations had been made for the famous balcony scene in Romeo and f uliet. The balcony had been made, and the show was on. When the time came for the lovely Juliet to come out on ·her balcony, the prop men remembered that they had forgotten to put a platform behind the scenery for her to stand on. In desperation a board was laid across two boys' backs, and the young lady calmly took her place. The audience, revelling in the eternal beauty of the scene, did not see the agony of suspense that was making it possible.

Before each show, Miss Brown would "borrow" Chief Burns, and between them they would hang curtains and try to collect a few properties. She proudly recalls one year, when she was preparing for Shakespeare, that a boy came over from Richmond College to aid her in her preparations. Though she doesn't remember his name, he occupies a very warm place in her heart to this day. It might have been Charles McDaniel, prominent Player of his time, who is now doing his acting as United Press correspondent on the Chinese front.

Not receiving any financial aid frorri the college or student government bodies, the Players found the going hard sledding, financially, even though the Red Cross Building was practically filled for each production. In the fall of 1927, a new constitution was adopted, giving the busine ss manager almost [ 12}

unlimited powers and also paying Miss Brown on a percentage basis.

Out to reestablish the Players in campus favor, the dramatic group took their Merchant of Venice which had been presented the previous spring, on a short tour. Twentyfive made the trip in a chartered bus to Loudon and the following night to Leesburg. The Players were enthusiastically received and had a fine time in the homes of their sponsors. The "old fellows" still recall the trip with fond memories. They remember that they arrived in Leesburg three hours late, having just enough time to set up the scenery. But the show had to go on. They worked with feverish haste, foregoing even the delicious, mountain supper that had been prepared for them. Necessity gave them added strength, and exactly at 8: 30 the curtain began to rise on a street scene in Venice.

So thrilled was the campus about this venture that three full columns in the Collegian were given to an account of the trip ( or perhaps they were short on news). Be that as it may, they began immediately to plan for a trip the following year. That same spring they received an offer to put on the "Merchant" in Blacksburg; so the thespians again enbussed. These tours were the topic of mention and conversation for the next several years, being pointed to as the goal which they should ever afterwards seek to equal. In this respect, to date, they never have.

The old Red Cross Building was the scene of many outstanding plays around this period. Among them were Shenandoah) a sword-androses romance of the Civil War, Kempy) Swan) Suppressed Desires) The Rivals) Wild Duck) Lady Windemere's Fan.

Increasing in their fame were the annual Shakespeare plays presented each year as a

part of the Commencement program in the cloister of Ryland Hall. Using three sections for the different scenes, the Gothic architecture of the building made a very effective background. Besides those plays before mentioned, the Bard's Taming of the Shrew) Hamlet) and The Merchant of Venice were produced here.

As a fitting dedication for the beautiful Greek Theatre, the University Players presented the famous Greek tragedy, Electra) in the fall of 1929. The following spring, The Merry Wives of Windsor was the offering in the new theatre. From the recurrence of their names it would appear that Elmer Potter and Lydia Hatfield were the actors declared by the campus "most likely to succeed."

Each year the senior play was the BIG event. It was presented under the sponsorship of the University Players at the old Strand Theatre. Now the Booker-T, it was then "dark" and was opened especially for this occasion. For days it was scoured with disinfectant, and often on the night of the production faint whiffs of it could be detected. On the night of "the play," the boys came in their tails ( if they had any) and the girls in their silks and ermines. It was a gala affair. The fraternities reserved boxes and hung Greek-lettered pennants over the side, and Dr. Boatwright and his party always led the group of educational and civic leaders present. We might try something of the kind today-but the Playhouse is not very conducive to tails and ermine.

The next general group to file across the stage on the pageant of drama at the University was the one that preceded us. It was the period that produced Joe Holland and Betty Burns (Nuckols). Joe has since become one of the outstanding Shakespearian actors of today. He has played in several productions with Katherine Cornell and is at present filling

[ 13 J

the title role of the much discussed modem version of Julius Cc:esar:

The makeshift stage in the Red Cross "gymnasium" was never suitable or properly equipped for dramatic productions. When the biology department moved from the Playhouse into newly completed Maryland Hall, the old barn was changed into a theatre and a student activities building. The administration gave Miss Brown carte blanc in the renovation of the building-as long as she did not spend over $200. And she, with her coworkers, stretched those dollars farther than one of F.D.'s fifty-nine cent ones.

The dedicatory play, Meet the Prince 1 was buffeted about like the sailors in the shipwreck scene of The Tempest. The serious illness of Miss Brown first halted the rehearsals and caused considerable postponing. Finally "Bus" Gray, who was playing the leading role, took over the directoral reins and put the play on. And a good job he did of it, too.

Other productions filling the bill during the period of 1931-1935 were Prunella 1 Mary 1 Mary 1 Quite Contrary 1 The Thirteenth Chair 1 The Ninth Guest 1 Outward Bound 1 Hay Fever 1 The Silver King 1 Journey's End 1 The Swan. Among the Shakespearian offerings were Twelfth Night 1 Richard III 1 and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

In Richard III 1 Joe Holland, who had just played the role in London, returned to take the leading part. Plans were made for a thrilling and stirring production. And it was a good show - for a collegiate group - but "Richard" did not make much of a campus hit. A few amusing technical errors occurred during the production. At one point, Richard was supposed to address his men from the top of a colonnade. The spot dramatically moved up to the selected position-but there was no Richard. Consternation reigned, as Joe threw

away an apple he was nibbling and vaulted for the top.

Beverley Britton, Vernon Richardson, Jacquelin Johnson, and Mary Mills were the other leading members of the Players at this time, filling either a large or small role in almost all of the productions.

Though the University Players did not know it, the curtain was about to fall on the second act of their story. As we see this small group working on Richard III 1 the curtain slowly covers the stage.

SCENE: The fall of 1935. Still in the airconditioned Playhouse along with the Web, Collegian, Messenger, and a few bats.

Sooner or later everyone of us grows up. And so it was with the University Players. Sorry to see their beloved Miss Brown go, and yet thrilled at the prospect of having a fulltime professional director, the Players welcomed California's, Mexico's and North Carolina's Alton Williams. Having just completed his work under the famous "Prof" Koch at the University of North Carolina, he brought to campus dramatics a new spirit and enthusiasm for the theatre. Treated more as a thrilling game to be played than a delicate art to be touched with reverend fingers, a new type of drama began to arise at Richmond.

The curtain rose for the 1935 season on a picturesque scene in the Grecian mountains. It was the setting for the fantasy Devil in the Cheese. This gave the technicians their grande opportunity to do some real work-and they did. As the action of the play moved on, the title figure came to life and began wielding his magic powers, among them the enabling of a person to see within another's head. Milton Lesnik, as a successful business man, wanted to see what his daughter Goldina

[ 14]

(Helene Miller) could see in that young rector Harold Phillips gave their best. But aviator (Clyde Hardy), who had crashed into when you try to put on a musical comedy with the mountains. So the next four scenes took a volunteer orchestra rehearsing only twice, place "in Goldina's head." And it kept the the odds are too great. It was a good stunt, stage crew trotting double time to change the and with a good campus orchestra could be scenes from a yacht to the beach of a Southern made an outstanding student event. tropical isle, to their little cottage home, all But back to our more serious productions. as the action of the play was going on. Some- The 1935 spring offering was Pollock's The times they didn't quite make connections, and Enemy. Set in the dreary atmosphere of a so Lesnik went on adlibbing lines which were dingy Austrian room, the ravages of war were better than the original, but rather disconcert- poignantly pictured. The transformation of ing to some of the actors. peaceful students and playing children into

It was a good season, with the one-acts com- fighting lunatics; the riots for bread; the rise ing in December, the Rigmarole just after of servants into millionaires-all were picexams, Channing Pollock's anti-war drama tured in this room. Many said that the set and The Enemy and closing with Shakespeare's acting combined to make it the best producComedy of Errors. tion, either professional or otherwise, ever Griffin Garnett, as president of the Players, offered on the campus. begged, threatened, or cajoled nearly every- Mr. Williams came to Richmond with the one on campus, who had the slightest degree idea that Shakespeare was not some drab old of talent in any field, into taking part in his fell ow who wrote lines over three hundred Rigmarole show. Though it was clearly an years ago, but was such a good playright that amateur group trying to imitate Broadway, his plays are good drama today. And none those who packed the aisles thoroughly en- was better than his medley of mistaken idenjoyed it (until it began to drag out after tity, The Comedy of Errors. Richmond Col11: 30). lege drafted its three sets of twins (Robert-

The highlight of the show was the "girls" sons, Millers, and Kings) and proceeded to of the pony ballet, composed partly of some give Mr. Williams and the rest of the cast a of our present illustrious members of the bad case of double vision. The production Student Government, going through their gave the Commencement visitors an evening tricky routine with amateur precision. And of good, fast-moving comedy, and many went people are still talking about the song that away saying, "By George, I never knew ShakeHilda Kirby sang-though not one in a hun- speare was like that. . . . Good direction. dred could tell you its name. (I know I ... Bill Shakespeare knew his stuff.... couldn't.) Why that was darn good."

Last year, in an effort to liven up the show, By the next fall (1936) the influence of the the scene was laid in a Negro night club and so-called "zanny" comedy was beginning to the story of a dusky maiden spurned used as a be felt, so for the Player's first offering, the plot on which to hang the original songs antics of the mad Rimplegars were depicted (splendid), fraternity skits (terrible), dance in a play appropriately called Three Cornered routines (good), singing (O.K.). It was a Moon. This type of high comedy is the most fairly good show, and those working with di- difficult form of drama to put across the foot-

[ 15]

lights, but Martha Ann Freeman, Dick Scammon, Bill Saunders, and others performed their task so ably that the audience was either in a deep "belly laugh" or an inward chuckle throughout the show.

The one-acts, Rigmarole 1 and the eerie Black Flamingo completed the winter season, with Shakespeare's charming fantasy, The Tempest filling the Commencement spot. Black Flamingo answered the campus conception of a "darn good show," but The Tempest was a little too ambitious a production for us to essay.

Generally speaking, that brings our show up to this year and the gently biting sarcasm of George Bernard Shaw in his Arms and the Man. With Sally Moore Barnes playing the fair Raina and Carlson Thomas as her "chocolate cream soldier," pleasant fun was poked at th~ whole idea of war and those who make it. The supporting cast made an interesting study of the divergent personalities as portrayed by the students.

The central theme of the Carolina Playmakers, where Mr. Williams did his graduate work, was the development of a native folk drama. Their director, "Prof" Koch, argued that the simple tales of our legendary and historic past, the everyday events of today, the crises of our native youth in a modern society, make a much more powerful drama than some lofty theme of cosmopolitan society, dancing and loving on the Riviera, or a comedy of professional fools on Broadway. As a part of Mr. Williams' effort to arouse interest in the development of a Virginia folk drama, the one-act bill was composed entirely of Carolina Folk-Plays. Ranging from the farcial comedy of a patent medicine doctor, to a mail order proposal, to the stark tragedy of life in a Carolina mill town, all shades of intere§t w~re appealed to.

The mere cataloging of plays presented, however, cannot give a true or complete picture of the Players at work ( or at play).

Along with the usual concerted attempt to develop dramatic talent among the student body, particular emphasis was made on the improvement of the technical ends of the productions. And so, before each play, anyone coming into the Playhouse would find Westhampton's social butterflies, clad in paint spattered coveralls working side by side with Phi Betas and football players from Richmond, doing sawing, painting, nailing, upholstering, necessary for the make-believe of the stage.

Beginning with the elaborate Devil in the Cheese set, an increasingly high standard has been maintained. The Ene~y set, though only one interior, was authentic in every detail, and it, as much as any other factor, helped to create the mood of the play. It is usually agreed, however, that the gloomy castle created for Black Flamingo was the best of them all. And the stylized scenery created for the Rigmaroles produced many novel and unusual effects. The dice and card motif of last year's show would have done credit to any Broadway club.

These elaborate settings made necessary the purchase of much additional equipment. During the last few years a new cyclorama, sky drop, ' new flats, switchboard, lighting equipment, and stage properties have been collected. Before a switchboard was put on the stage, one was jammed up in a small back room, and light cues had to be relayed through three persons to get to the electrician. Many close shaves and misplaced effects were the result.

For technical work a thoroughly equipped shop has been developed, with facilities either for making delicate wood inlays or the [ 16]

.finishing of massive timbers as used in the Black Flamingo set.

With their professional director, splendid equipment, and background of fourteen years' experience, the Players pride themselves on their precision and methodicalness. But even with such a group as they ( !) hitches sometimes occur. But, so the sages say, variety is the spice of life.

Paul Green's story of how a Negro girl " skeared her pappy into letting her marry up wif her man," told in The Man Who Died at Twelve O'clock, has had its share of vicissitudes on the Playhouse stage. It was .firstpresented in the fall of '36 on the bill of one-acts. The title role was .filled by our football, basketball and blackface ace, Bill Robertson ('37). The night of the play he had to help the Spiders whip Hampden-Sydney before he could don his burnt cork. Nine-thirty passed ( the latest time at which he was to be due) , nine-forty-five, ten. Harold Phillips, who was ·directing the play, was pretty nearly out by this time . Messengers said that Bill would be right over. And at three-after-ten, in came the hero, with a grin on his face and one shoe on. The play began as the last cork was applied and the kinky wig put in place.

This year when the same play was put on as a part of the Orientation Week program, the costumer who had agreed to furnish the devil's costume unexpectedly closed shop and left us holding the bag. Every costumer and pawnshop in Richmond was searched, but there was a dearth of devils. So that night

after supper, from scraps of red cambric found in our collection, Caroline Spenser double-quicked to make a suit. As the curtain rose, she was sewing on a long red tail.

And in the performance of Quare Medicine, neither the cast, nor the audience could keep in their seats, for wondering whether or not Billy Griggs' beard would stay on. By the time he had said his last speech, only three strands connected his mustachio with his chin. But "the show must go on!" and valiently he carried out his part, never once breaking.

It is these experiences and incidents that make the Players live for us. Smooth waters are all right on a moonlight night, but it is really a show when the waves begin to break and thunder begins to roar.

Drama on the campus, and the Players in particular, have been helped by the establishment of a department of drama and the inauguration of classes in the various phases of dramatic arts. This seems destined to put drama on an even .firmer basis, and to point more clearly to its development in the future.

As the lights begin to dim, we see Mr. Williams, Harold Phillips, and some of the other Players looking at the plans of the new collegiate theatre just built at Amherst. The lights deepen into darkness and we hear a dreamy "Someday. . . . Perhaps. . . "

(Future acts in the making.)

AUTHOR ' S Norn: The majority of the information incorporated in this article was secured through the courtesy of Miss Lucy T. Throckmorton, Miss Emily Brown, and B everley Britton.

[ 17]

WHILE THE December MESSENGERwas magazines to ours, we would not, in all probcoming off the presses, we were in Lexington, ability, appreciate the ramifications of "daring attending a convention of the Virginia Inter- article." collegiate Press Association. One surprising Every editorial staff member with whom fact we brought away from our discussions we talked expressed amazement when told with fell ow-editors has evoked no little there had been no administrative repercusthought since our return to the office. sions from the story, that no one had been

We had set out deliberately to ascertain threatened with dismissal from THE MESwith what reaction the article in our October SENGER,and no ruling at the University of number, rrour Enemy Within," an expose of Richmond provided for faculty literary "adconditions in the Richmond College dormi- visors." tories, was received on other campuses; for Many schools, we learned, require that all one of the sundry charges brought against us material selected by the editors of their magalocally was that of damaging the prestige of zine for publication be examined, before gothe University by its publication. This had, ing to press, by "advisors"-a genteel word of course, been taken into consideration be- for learned, mature persons who. tell naughtyfore the investigation was completed, and we boy editors what is nice and what isn't nice. had decided that over-emphasis had been In one case a page-one story of vast imporplaced on this aspect. tance, one that might have aroused even the

We were right. Somewhat typical of the public press, was stripped from the forms at attitude of others is the passage from Cargoes the printshop on orders from the "advisors." of Hollins College: "In the MESSENGERfrom In another instance, the editors of a magazine Richmond College, there is an excellent edi- had awarded a prize to a piece of writing subtorial accusing the college dormitories of be- mitted in a contest. After the winner had been ing 'outmoded, antiquated, unsanitary.' We named, the "advisors" reversed first and sechope it has some effect, because it is a daring ond awards over the editors' decision! Since article, written by one who evidently feels pis our trip, another college magazine, a combisubject deeply." nation of the humor-literary group, has been

There is more in this quotation than first forced to suspend publication, because of the meets the eye. It is not our intention just now "radicalism" of its editor who has been disto revive the question of what shall be done charged. to remedy the attacked situation, because we In short, we are indeed fortunate that ours have reason to believe that action in the matter is one of the few colleges in the state devoid is forthcoming. of censorship, except that laid by the editors

But we want to focus attention on that word upon their respective publications, one dic"daring." Had we not attended the conven- tated solely by common-sense, decency, and tion and queried several editors of similar fair play.

[ 18]

THEREAREALWAYS a few persons who are ever ready to read vulgar meanings into innocent words, thoughts, and expressions. Running true to form, a number of members of this minority class objected to the word "skronch" which appeared in a story in our December number. We don't want to disappoint any of our chop-licking customers, but, in fairness to the author of the story and to anyone else concerned, we must report that "skronch" is gibberish.

"Skronch" sprang into being as an innocuous combination of one vowel and several consonants, similar combinations of which frequently result in interesting inharmonious mouth-fillers and ear-arresters. "Skronch" isn't even a good, healthy hybrid. Other examples of such delightfully harebrained coinage are: "nghyakh," "glop," "squeedunk," and any of the Cab Calloway-type vocal emissions. All are without any universal meanings All can be assigned meanings appropriate to the occasion. None can be justified on philological grounds, since all are happily devoid of stuffy etymologies. The only "dirty" meaning of "skronch," then, is that put there by the prurient mind of the reader.

"Skronch" is used locally in a number of ways: as a transitive verb, as an intransitive verb, as a greeting, as an exclamation, as a password, and as a title. A low meaning may be inferred in each use and need not be inf erred in any. Personal choice here has wide range. No erotic or obscene meaning was implied in the story. If we want to express disapproval of someone, we snarl, "Skronch you!" If we feel that we've been deprived of our just rewards, we say, "Prof. Bones sure

skronched me." As an exclamation, "skronch" is roughly equivalent to "Bah!", "Rats!", T ommyrot !", except that "Skronch !" undeniably has more color. By popular usage, "skronch" has come thus to mean something resembling "squelch." But why elaborate further?

This whole matter, essentially trivial though it is, illustrates once more the eagerness of some persons-unfortunately, not always a minority-for reading matter supposed to be spicy or risque. A variation of this tendency is the vigilant searching for unintended offcolor significance, as in the "skronch" case. This situation disgusts us. The "skronch" case probably disgusts the diseased-mind boys more, however, because this time they were , fooled. "Skronch" doesn't mean what they hoped it would. As we pointed out, it doesn't mean anything! Better luck next time. If we wanted to be vindictive toward these sly individuals, we might even say "Skronch you!" -f -f -f

The 1936-37 MESSENGERwas awarded first prize for excellence among literary magazines in its class at the Virginia Intercollegiate Press Association convention, held at Lexington in December. We are tremendously pleased to see the efforts of last year's editors, Russell S. Tate, Francis W. Tyndall, and Margaret Dudley, in reestablishing the book as a joint publication of Richmond and Westhampton Colleges and one of influence thusly recognized.

[ 19]

"qoiu9 to chu'tchdoesu' t make ~ou a Clt1tistiauau~ mo'teftiau 9oiu9to a 9a1ta9emake&~ouau automobile"

By MARY ARNOLD ALTHOUGHGROWTHhas

altered my views, I have always employed a studied program of thought and behavior within the church. Looking backward, I am frequently amused by the distinctly separated pigeonholes in my development as a churchgoer. Though now I feel my perspective is somewhat the ultimate one for me, I can never quite forget the humor that the cinematic story of my early adventures in church emanates. For those days of counting sleeping neighbors, comparing in kittenish manner the apparel of Jean and Martha, pressing back laughter at the buzzing fly making neat three-point landings on the smooth pate of Mr. Doe were happy and have led me to the richer conception of church I now have.

Compulsory church attendance was wordlessly established in our household, and in my early childhood I was resigned to it with the innocent acceptance of fate, characteristic of the very young. Once inside church, however, my thoughts were my own, and I immediately adopted my premeditated routine, which at that age consisted of incessant twists, squirms, and wiggles that I doggedly maintained until I was thoroughly convinced that the entire congregation longed to take me over its collective knee.

Then, with a smug little smile, I would

change my tactics. At the "let-us-pray" point of the service, if completely certain of an audience, I would clasp my hands together, bowing my head demurely, well aware of the sweet picture of childish piety I presented. I could sometimes manage to stand on the pew, scan the congregation for a watchful and appreciative eye, and, finding it, immediately go through my babyish tricks, smiling impishly at the momentarily delighted spectators. As their interest waned, my next course of action was to walk along the pew, jolting hats from the row of heads in front of me. When the benediction was mercifully pronounced, hundreds of tired souls departed from the church, souls void of beautiful feel ings, and filled with malice toward one small child. But my black, guileful little heart knew no pangs of remorse. I had bigger, more important things to think about. I had to find out what had become of Chester Gump, who, when last seen, was standing at the brink of a poison-filled pit in the depths of China, with a hundred green-eyed monsters behind him.

As I approached the unfortunate age of ten, I inevitably began to lose the rougish charm I had previously used to best advantage. My legs lengthened alarmingly, and I rapidly developed into that unattractive age called "gawky." Being of average intelligence, I was [ 20}

not slow to realize that I could no longer get away with my cute little tricks. Hence, Sunday morning church came to mean a choice of two alternatives: to try with various rough and yet unskillful methods to be exempt from church, or, that failing, to adopt a new plan of action within church. The latter invariably became the case, as my timely and dramatic illnesses were always disposed of by a knowing smile from Mother, who would assure me sweetly that I would feel much better after church. Consequently, my program became revised, lacking much of the spirit and dash of the rejected one. I now sat quietly between Mother and Dad, carrying on mental conversations with myself. My favorite topic was the everpresent argument of whether the pastor bore more resemblance to a penguin or to a walrus. We would discuss it at great length-myself and I-but we inevitably compromised by agreeing that it was clearly a tie, as his drooping jowls and waddling carriage marked him as being definitely of the walrus type, and yet the full dress attire on his particular physical stature labeled him as being of the penguin variety.

My next diversion was to listen for the choir to whistle on their "s's. " Then I would take fiendish delight in listening for errors in the responsive reading, at which I became convulsed with forbidden laughter. I was often reduced merely to staring at the ceiling; consequently, I can still remember that the ceilingdome is divided into six sections, with eight cross beams to a section, each beam being studded with forty-eight gold knobs.

At the sensitive age of fourteen I commenced to think about clothes and boys. Early Sunday morning I began to worry about what I should wear, and later in church I began to worry-after a careful survey around meabout what I should have worn. My mental

[ 21]

activities at this age were mostly directed at retrimming hats in the congregation. However, the core of my thoughts was always absorbed by an overwhelming envy of my older sister, whose young man now attended church with us. My one ambition was to reach her status, and, accordingly, her privilege, which was to me the essence of romance.

I realized a few years later from experience that my ideal was a fragile air castle, for being accompanied to church by one's young man was to be accompanied by relentless embarrassment and uneasiness. It was during this period that I first discovered that hats-all hats-big or small, picturesque or tricky, were unbearably unbecoming to me. Walking up the aisle with my Mr. Non de Script, was walking endless miles through a treacherous chaos of whispers, which mercilessly reached our reddening ears: from the very young, a singsong chant of "Mary's got a fell a'," from the very old a whisper, "Miss Arnold's growin' up! See her with a beau?" (Detestable word!)

Arriving at last at our pew, we were always confronted by another problem in the bulky form of Mr. X, large and balloon-shaped. I ref er to the dirigible balloon, not the red, green, or yellow kind that characterize fair grounds. Trustee of the bank and pillar of the church, he occupied the extreme end of our pew in a state of semi-somnambulism, as surely as the pastor occupied the pulpit in one of gusto and fervence. It was always a most perplexing decision, whether we should attempt to squeeze through the small space between his pudgy knees and the back of the next pew, or to arouse him enough to indicate the necessity of his arising, risking the embarrassment of his loud grunts. Either method presented a disturbingly vivid picture in my mind of its possible failure.

Once safely seated, new difficulties arose. I

became more and more aware of my unflattering, Sunday morning appearance, and even more acutely aware of Mr. Non de Script's awareness thereof. Sharing the heavy hymnal with him presented the unmistakable fact to Mr. Non de Script that my vocal accomplishments were exceedingly poor, and, as my voice wandered uncertainly to false notes, I yearned for the carefree days when I could crawl around on pews with nothing more to contend with than a "no-no" look from Mother.

At eighteen, which is more-or-less conceded to be mental maturity, my attitude toward church underwent the most radical and fortunate change of all. Whether it was a subtle change or an impulsive one I do not know. My vain ideas of dress were replaced by the desire simply to be clothed appropriately. Whether or not I was accompanied by a man was of little importance. I began to enjoy church as church.

Perhaps, this metamorphosis came when I accidentally overheard an interesting portion of the sermon. Perhaps, the choir offered a particularly beautiful selection. But I am more inclined merely to credit myself with having developed a deeper mental capacity and appreciation. In view of all this, I have again adopted a new and comfortable routine of thought. I listen experimentally to the first part of the sermon. If it does not please me, I dispense with that and dedicate the remaining time to catching up on thoughts of a religious nature.

One cannot always stop during the busy week to sort her ideals and standards and ponder over right and wrong. Sunday morning brings a chance to reflect back over the past week, and it provides me with the inspiration and desire to meet the problems of the approaching one in a more Christian fashion. I do not always listen to the pastor's prayer. Quite of ten I originate my own, suiting my own emotions, difficulties, and circumstances. I no longer dread church; I welcome it, sometimes as a peaceful setting for my religious moods and silent communication with Him, sometimes as an opportunity to listen to someone, who is more versed than I, talk to me on a subject about which he knows much, and I little. I no longer see services dismissed with a mental expression of glee; I see them go with an inexpressible feeling that I have either learned or experienced something for which I am a better person.

I can now see the pastor as an intelligent human being, without absurd similarities diverting my mind. I have nearly forgotten that there are forty-eight gold knobs on each beam of the ceiling. But best of all, I am on my way toward a fullness of religious appreciation, which I am sincere in wanting to develop, that the curtains separating my mind from Knowledge, my heart from Love, and my soul from God may be lowered, so that more distinctly I may hear the Voice, more truly I may be in the Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man.

The other night

The moon was bright And shone on fence and path That turned and ran, a silver sliver,

Behind the hill, a pile, a mass

Of dark stark Oaks. One stood dim Against the bright Stars; and from one limb

Hung a slight Form, twisting and turning. Under was burning

A leaping fire that seared and sheared Rags from a tortured body. A multitude of masked men Became enmeshed

In the odor of scorching flesh. At the bottom of the hill

An old man, ill, Bent, leaning on a cane, Wept bitterly. Tears coursed down his brown

Wrinkled face. "Oh, God, that sane Men act thus!"

In the east the cold grey dawn Broke. The sun Was rising as the wan Old man turned and stumbled on, Sobbing, "My son, my son!"

-ROBERT MURRILL.

By OWEN TATE

FROM ACROSS the lake a strong voice has come telling us that woman is so hampered by convention and by the active opposition of men that she is unequal at present, but in the future she will rise to equality and, possibly, dominance. It has been said that the girls are ham-strung by fear of public opinion to the extent that they have no chance to live their own lives and to exert their individuality. The bone of contention seems to have two main protuberances: woman does not have an equal chance with man in the business world, and ·woman does not have the same freedom of choice in her love life.

If it is granted that this is a true brief of the case as was stated in "Twilight of the Gods," then let the discussion continue.

The successful business woman of today is holding her job, not because "the female is deadlier than the male," and not because some kind hearted boss believes that women ought to have a place in commerce, but for the simple reason that she contributes valuable service to her employer. She receives a salary in payment for work performed. She is not hired to wear skirts, but to do work. If the quality of her work falls to a point at which her services no longer render her employer a profit, then she will be replaced by some one better fitted to do the job. The employer will try to hire the most capable person available regardless of sex.

Labor is hired to do work, and if the work brings a profit on the capital invested, the owner of the capital doesn't give a damn whether the employees are male, female, or neuter. Competence in work, instead of sexual potency, is the requisite of the employee. Were your skirts or your trousers made by a man or a woman? You don't care which. You are interested only in the quality of the goods. It has been said that the world is striving to keep the woman in the home and that man resents her influx into the positions that he has formerly held. We readily concede that man hates for woman to get his job. Now, will the militant ladies be kind enough to admit that a woman might hate to see a man get her job? Let's get close to earth with a hypothetical case, in which there is one vacancy to be filled and four applicants. Two of these applicants are men and two are women. Suppose one of the women gets the job. Both of the men will react as individuals and say, "I should have gotten that job." And equally important, the jobless woman will say, "I should have gotten that job." A man trying to get a job wants that position for himself and doesn't want to see any other man or a woman getting it. In the competition for jobs, the men fight each other as hard as they fight the women, and it is just. Men or women who find themselves unable to meet the competition have no right to blame the opposite sex. The employer hires ability, not anatomy.

"Twilight of the Gods" tells us that woman is tied by convention so tightly that she does not have the same freedom in her love life that man possesses. The case in point of a woman

[ 24]

who defied convention was taken from H. G. Wells' Ann Veronica. It seems that Ann was a modern girl, who wanted to live her own life; so she approached a married man and requested him to be her lover. We haven't gotten around to reading the book yet, but, according to the author of the article, Ann wins. If we scrap existing conventions-and why should we not ?-woman has the right to as free a sex life as any man. Of course, marriage will then be an excresence of love and will be discarded. Ann will have children, because that is a fundamental desire, having nothing to do with convention, but her children won't have any last name, for surnames are conventional. It may be that Ann will have to work very hard to support herself and offspring, and, if her lover believes in the dominance of women, then she will have to support him too. If Ann's pretty young daughter lives her own life so independently that she becomes diseased, poor, and has only her freedom left, she may want to return to the shelter of her father's home. But, alas! she won't know who her father is! We believe that most of the conventions regarding love have been set up by women to fill a definite need. In a society without conventions, the man could always escape responsibility for his acts, but there would be no escape for the woman.

Beyond question, woman is inhibited by conventions. The fear of gossiping neighbors exerts a tremendous influence on the behavior of everyone, but on women most of all. In our own Southland, the double standard has created a wide gap between what is acceptable conduct for men and for women. While the man sows his wild oats with a minimum of disapproval from his contemporaries, the girl who does the same thing is likely to lose caste for a lifetime. Admittedly, this is unfair, and the solution lies in changing the conventions

which have brought these conditions about. How to change the modes of civilization is a problem for Solomon.