UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND

December I 9 3 6

December I 9 3 6

by SAMUEL COHEN

It was a brainless dream of fancied things In which he built a cool land of his own Whose wonder made him scam what real life brings, But soon it drew him fast to earth alone. He dwelt where birds were seized by sword -sharp rapture As they touched the folds of sweeping night. He smiled at thrushes staving off their capture By entrancing hunters with delight.

" My God!" he cried , with tremors of emotion , " Can this be lasting all my magic bliss Like moonlight stealing on the curling ocean Elfin romance of its fume-blown kiss? " With that the bubbling pageant melted in his dream; His ocean narrowed down to one bright stream. Desire cleaved him from this land of Sane , A clutching Faustian web wrapped iron snares, Enflaming cups of drink stirred on his crying brain, And lusty fevered thrills bewitched him unawares. Then he thanked the Gods for changing things And blessed the living groups of gleaming clay Yet laying bare their souls to wicked slings Bright-arrowed down on them in painful play

by GEORGE SCHEER

Illustrated by Oscar Eddleton

THE FINGERS of dawn were drawing back the blinds of night, and the slightly chilled w ind of the early May morning puffed up from t he sluggish river , lapping the south pasture d own the hill. Outside his window , the slim t ree swayed , dark ivy rattled Wash sat up on h is pallet and rubbed sleep from his eyes. His bare , little feet moved noiselessly across the k notty , pine floor. Fumbling along the wall in t he dark , he pulled an old pair of leather breeches a nd a tattered , red shirt from a peg. He pulled o n the breeches , and squirmed into the shirt , w hile he ran through the kitchen to the door . As he jumped down the hewn log doorsteps , a hound puppy wormed out on his belly from b eneath the long , narrow cabin It followed W ash down to the spring and watched the boy splash the cold , sparkling water on his face , rub it in his kinky , black hair , and drink some of it fr om his cupped, black hands

" Come on, houn ' dawg , if' n yo ' all wants t ' go git Gen ' al Lee." The brown puppy leaped ahead of his small master toward the flat river b ank. The boy and the dog stood by the windla ss and watched " Gen ' l Lee ' s " approach along t he road across the muddy water When he was w ithin hailing distance , " Gen ' al Lee" shouted , " Gen ' al Stuart , will yo ' all come git me dis m awnin ' ?"

" Yes , sub ," the boy called back The boy a nd the dog walked down to where the ferry lay , like a tiny lighter , making sucking sounds on the b ank. They climbed on the flat boat , and , tugg ing fiercely at the rope running overhead , the boy pulled the ferry across. " Gen ' al Lee " s tepped aboard , and the ferry began its trip back. Midstream it hung in the down current , and " Gen ' al Lee " relaxed his hold on the rope. He solemnly scratched the back of his wooly head a nd addressed the boy : " Gen'al Stuart, we kin

sit right here an ' plan de day ' s wu k. Fust of all , is yo ' all had brekfast? Naw? Den mabbe yo ' all ' s mama will let me stay, so ' s I won' have t' go all de way home . Den I can hope you git de apples down. "

"Gen ' al Stuart " said , " Dat ' s what mama 'lowed yo'd do . Gen'al Lee , we's goin ' t' git somethin ' t' eat I' se hongry; le ' s go. "

After a " breakfast " of sliced apples , fried in bacon grease, and potato coffee, sour without cream or sugar , the two went down to the orchard , and , while Wash ' s father shook them from the trees , the boys sorted apples to send to the " Missus " at the " big house ." Toward noon they slipped away to the river , a nd, walking along the flats , poked frogs out of th e holes in the mud . After a while , they reached a tin y plateau on which was pitched a tent made of two dirty sheets . Here they threw themselves on the tender grass

" Wash ' ton ," the younger one asked , " why does you play Gen ' al Stuart and I plays Gen ' al Lee? Seems lak Gen ' al Lee am de haid man in de army. Mos' folks ain' heared much ' bout Gen ' al Stuart. What do he do , anyway ?"

" What do he do ?" the other echoed . " Why , ain ' yo ' heared old Missus say dat young massa done gone t' git in de war and fight wif Gen' al Stuart. My mama done tol' m e dat Gen ' al Stuart come to de big house once; she seen him . ' Twar at night , an ' he come , big an' tall, on a big , brown hawse He got a big beard an ' a mus 'tache an ' a big hat wif a star an ' a long feather hangin ' ont' hit An ' he got a man wif him what kin beat de banjer an ' a big giant--yes, sub , a real, live giant-what can sing . An' dey all come up one night , an ' dey singed undah de windows , all ober old Missus ' flower baids. But old Missus didn ' mind , ' case hit whar Gen ' al Stuart what tromped up de baid ."

Wash snatched a long stick from the ground and waved it over his head. " Why , I heared mama tell how Gen ' al Stuart done chase de Yanks clean out ob sight mor ' n once. Co ' se Gen ' al Lee am de haid man, but I laks Gen' al Stuart ."

The smaller boy stood up , and grinned. He said, " I 'spect yo ' ain ' got no feather in yo ' hat ' case yo ' jes ' ain ' got nary a hat !"

" I ain ' got no hat now , but when I gits big an ' jines de arm y I'se gwine hab a hat."

" Sheeks , my mammy done tol' me cullud boys can ' git in de army , lessen hits de Yankee a rmy , an ' don' nobody want t' jine dat army. Wash ' ton , is yo' eber seed Gen ' al Lee, nor Gen ' al Stuart?"

Wash shook his head and ran his hands into his pockets. They started back along the river. For several minutes neither spoke. Wash's anquished thoughts crouched , then sprang bitterly.

" Yo ' mama mus ' not know ' bout de war, " he cried " My mama sayed I c'ud jine de army , an ' I c' ud go ' way jes ' lak young massa, when I g rowed up An' my mama stays at de big house She hears de white folks talk , an she tol' me I c' ud jine de army when I gits big."

His friend ' s voice quivered with excitement, a s he shouted , " I knows my mammy ain ' wrong. She sayed dat de onlyest way dat yo ' kin git in de army is t' go on wif de massa t' look af' er his things She sayed cullud boys ain' gwine git in de army ."

" Dat jes ' ain ' so ," was all that Wash replied , a nd the two boys walked home in silence

Late in the afternoon , they walked down to the ferry The hot hours were past , and again it was cool and quiet there , as it had been early in the morning. Wash no longer called the younger boy '' Gen ' al Lee ''; he was mad \}..Tashknew that little colored boys could join the army when they " gits big ." Clarence was wrong , and Clarence didn ' t know about brave , big " Gen ' al Stuart . " He didn ' t speak to Clarence , as they pulled the ferry across the turgid water . Instead , he addressed his remarks to the hound. " Houn' dawg ," he murmured , " you jes ' wait till I sees

Gen'al Stuart ; den Cla-ence ain ' gwine talk so big. "

A crestfallen " Gen' al Lee " swung down off the ferry on the far side. He had walked only a few feet when he turned and said , ' Tse sorry, Gen'al Stuart. I din' mean nothin ' nohow. Mebbe yo ' is gwin jine de army when yo ' gits big . I' se sorry I' se made yo' mad. "

Surlily , Wash muttered, " Oat ' s all right , C la ' ence. "

The sun had almost set by the time Wash reached his side of the river. He trudged up to the windlass and hitched a length of rope around the two uprights. As was his custom, before turning to go home , he shaded his eyes from the last , long rays of the sun and peered down the road which Clarence had taken. A puffy cloud of dust seemed to be moving on the turnpike It turned into the road near Clarence's cabin , grew larger , and began to take the shape of a great cigar. Soon , Wash was able to discern horsemen, moving from beneath the billowy dust They approached rapidly , and Wash could see their dull, gray uniforms , coated with the yellow powder of the road. Wash quickly threw the ropes clear of the windlass , ran to the ferry , and started across the river A big man rode at the head of the column. He held up his sword , thin and red , in the sunset , and ordered the column to halt.

With two other men , he trotted his horse to the ferry. Wash looked up clos ely at him now. He was full in the body and wore a tight-fitting , gray jacket and blue trousers and a hat with a plume. He had a moustache and a silky beard , which he was now stroking thoughtfully Wash knew it was he; this man was Jeb Stuart. He was seeing "Gen' al Stuart."

The man leaned from his saddle and said, " Boy, I am General Stuart, and my men are tired. We must cross here and go a little beyond Enon Church. Are you going to let us use your ferry? " He smiled slowly and continued to stroke his beard with his strong, yellow-glov ed hand " Y-yes , suh , yo' all kin come on de ferry. Go'se hits gwine take time t' git all de gen ' muns 'cross. I kin try." . 6 .

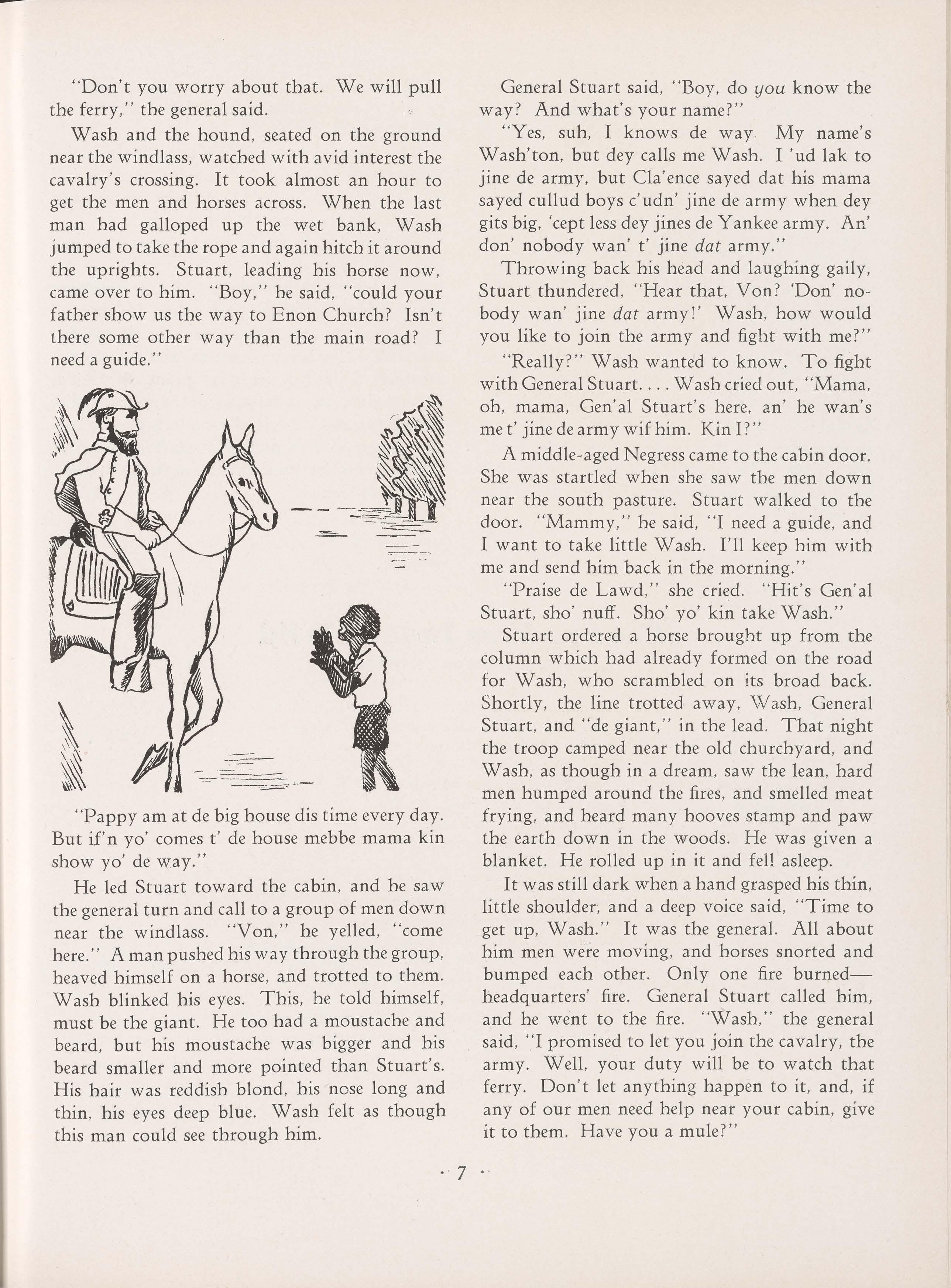

"Don't you worry about that. We will pull the ferry,'' the general said. Wash and the hound, seated on the ground near the windlass, watched with avid interest the cavalry's crossing. It took almost an hour to get the men and horses across. When the last man had galloped up the wet bank, Wash jumped to take the rope and again hitch it around the uprights. Stuart, leading his horse now, came over to him. "Boy," he said, "could your father show us the way to Enon Church? Isn't there some other way than the main road? I need a guide."

"Pappy am at de big house dis time every day. But if n yo' comest' de house mebbe mama kin show yo' de way."

He led Stuart toward the cabin, and he saw the general turn and call to a group of men down near the windlass. "Von," he yelled, "come here.'' A man pushed his way through the group, heaved himself on a horse, and trotted to them. Wash blinked his eyes. This, he told himself, must be the giant. He too had a moustache and beard, but his moustache was bigger and his beard smaller and more pointed than Stuart's. His hair was reddish blond, his nose long and thin, his eyes deep blue. Wash felt as though this man could see through him.

General Stuart said, "Boy, do you know the way? And what's your name?"

"Yes, sub, I knows de way My name's Wash'ton, but dey calls me Wash. I 'ud lak to jine de army, but Cla' ence sayed dat his mama sayed cullud boys c'udn' jine de army when dey gits big, 'cept less dey jines de Yankee army. An' don' nobody wan' t' jine dat army."

Throwing back his head and laughing gaily, Stuart thundered, "Hear that, Von? 'Don' nobody wan' jine dat army!' Wash, how would you like to join the army and fight with me?"

"Really?" Wash wanted to know. To fight with General Stuart .... Wash cried out, "Mama, oh, mama, Gen' al Stuart's here, an' he wan' s met' jine de army wif him. Kin I?''

A middle-aged Negress came to the cabin door. She was startled when she saw the men down near the south pasture. Stuart walked to the door. "Mammy," he said, "I need a guide, and I want to take little Wash. I'll keep him with me and send him back in the morning."

"Praise de La wd," she cried. "Hit's Gen' al Stuart, sho' nuff. Sho' yo' kin take Wash."

Stuart ordered a horse brought up from the column which had already formed on the road for Wash, who scrambled on its broad back. Shortly, the line trotted away, \Vash, General Stuart, and "de giant," in the lead. That night the troop camped near the old churchyard, and Wash, as though in a dream, saw the lean, hard men humped around the fires, and smelled meat frying, and heard many hooves stamp and paw the earth down 1n the woods. He was given a blanket. He rolled up in it and fell asleep.

It was still dark when a hand grasped his thin, little shoulder, and a deep voice said, "Time to get up, Wash." It was the general. All about him men were moving, and horses snorted and bumped each other. Only one fire burnedheadquarters' fire. General Stuart called him, and he went to the fire. "Wash," the general said, "I promised to let you join the cavalry, the army. Well, your duty will be to watch that ferry. Don't let anything happen to it, and, if any of our men need help near your cabin, give it to them. Have you a mule?"

"No, sub. De Yankees stoled de las' mule we had. We din' hab but two <lat ol' massa give us when he went t' war, an' dey tuk dem."

'' Well, Wash, I have a horse here that you can use for plowing. It's an old horse and not strong enough for the army, but if you take care of it , it will do for plowing. It's too slow for cavalry and too wild for wagons. You can quiet it. And here's a paper saying that you, Washington , are a soldier of the Cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia. There ' s your name, and here ' s mine.''

" Gen ' al Stuart," Wash said to the great, kind soldier, "C la ' ence and me play soljer every day , an' I' se always Gen ' al Stuart, an' I lets him be Gen' al Lee, eben if' n Gen ' al Lee am de haid man in de army. Cla' ence laughs at me , 'case I ain ' got no hat wif a star an' a feather. But now I kin tell him I' se in de army, eben if' n I ain' got no feather."

One of the men came over, laughing. "Boy," he said, " take this hat. Maybe later you can find a feather."

The giant rode up. Wash thought he had a funny voice. He said , " Yell, now, ve must haf d' fedder !" He tore the plume from his own hat and stuck it deep into Wash's hat band.

General Stuart thanked him, and the men galloped off.

The sun was beginning to touch the tree tops when Wash pulled up at the ferry. He shouted happily to the tiny figure across the river: "Hi, Gen'al Lee, l'se sorry ' bout las' night, but dat's all right. I jined de army las' night , an' Gen' al Stuart gived me a hawse. Jes a minute; I'se comin' fur yo'! He gived me a hawse an' a hat, an' see here, de sho ' nuff giant stuck a feather in my hat. Yes, he done stuck a feather in my hat , jes' lak de Gen ' al."

by FRANCIS \V. TYNDALi.

The sea was indeed wild.

Puffing and belching , the sea spewed Its salty breath ouer the frantic ship.

The wind whistled a dirge

Thru th e wildly flapping sails.

Lights on the shore crossed rapidly

Like shooting stars in Hade s.

Gazing aloft, a sai lor screamed

H e had seen Death

Death sat on the cross bars and Made shrouds from the fluttering canvas.

A sailor screame d and knelt in pray er.

Reaching forth an octupus arm,

T h e sea drew him to her breast.

Rocks on the shore echoed the steady boom

Of the madly rocking sea.

The ship broke upon the rocks with a sound

Like the cracking of dead bones.

The sea was indeed wild . . 8 .

by LEWIS EARLES

when she is talking volubly in a group of girls she suddenly halts in delicate confusion when you appear, and blushes prettily. (Don't be discouraged if she doesn't blush. Her blood pressure may be low.)

she speaks in saccharine tones when she comes upon you talking to another girl and waits for you to terminate the conversation on the pretext that she has something very important to tell you. (If she is near-sighted this will not work. But then if she is near-sighted nothing will work.)

while you are dancing together she leans her lovely head upon your shoulder and sighs a deep sigh, like this Ah-h-h-h-h-h. Note: (A yawn may easily be confused with a deep sigh, so don't take things for granted.)

... she fails to pass a class which you both attend and only that one-of course, other deficiencies in scholarship would make it hard to decide. (If she is smart enough to pass the class she is too smart to be in love with you.)

... upon leaving the stadium after the home team has triumphed by twenty-one points or more, she suddenly asks, "Darling, who won?"

( This may be exasperating at times but you must be patient. Also it may indicate a lack of interest in football, or worse-too much interest in that dark handsome stranger who sat just behind you.)

... you have money. Caution: If you attempt to four-flush you do so at your own risk.

... when you suggest a movie she doesn't always pick the latest Robert Taylor film and then go to the early show so she can sit through it twice. (Figure this out for yourself.)

... while your are in the corner having a tete-atete with that little blonde, you feel a rather un-

9

comfortable sensation in the small of your back ( guilty conscience) and on glancing around you discover her and her girl friend looking daggers at you. (The G. F. is wise.) And when you again look at the blonde she has that look in her eyes which says, "Mister, you are signed, sealed and delivered." (If this glaring keeps up very long you begin to feel like a flea on a hot rock

you know-jumpy.)

... you ask her girl friend's fellow and he tells you that she does (This is ruled out because it isn't cricket ... anyway it's no fun because it's too easy.)

when you ask her to marry you, she says, y-e-s .... Of course this step is to be taken only in extreme cases as it is final, fatal and finis!

Warning to bachelors: Tread with care as this is extremely thin ice which may break at any moment and submerge you in a sea of matrimony.

you were a Jeffersonian Democrat and she never says, "I told you so." (The impulse to have the last word is almost irrepressible in most girls and should be taken into consideration.)

... you are always "paired off" as a matter of course, when the occasion demands it. (Everyone knows it but you.)

... she "never has anything to do" when you telephone her. ( All other factors being equal.)

she is always sweet tempered and refuses to argue on any subject, especially if she has red hair. (It's wonderful what love can do.)

when you escort another girl to a dance the looks that you get from her friends would make the Sphinx squirm. (Two-timer.)

by BERNARD M. DABNEY, Jr.

Little hidden leaf of green , Why must you live a life unseen

Amongst so many other leaves ? Why do you tum a brighter hue When ale Jack Frost calls out to youWhen clothes of snowy white he weaves? I often fancy , when I lie Beneath a tree and see the sky Above my leafy canopy, That leaves all try to talk to me And tell of wonders I should seeThat they have seen in fantasy. When brightly colored leaves drift dou : n - -As if they dread to touch the ground And die on Mother Earth so soon-I see the older loved ones go , Their hair as white as drifting snowThey ' re passing like the waning moon Of would I that the leaves could singIn music tell of ev ' rything

That they have seen beneath their shade; Of love ' s -first kiss-of cooing birdsOf babies and their precious wordsBut with the leaves all this must fade. Perhaps the leaves have loved and lostPerhaps their life is what love costMight be they fade and die from this ; But I think that the leaves have won Their sweethearts with their laughing fun That often gives me hours of bliss. I love the leaves upon the tree, While waving like the dark green sea, When full of life and joy; When they are in the prime of life And fear not Autumn's coming strife-I love them like a childhood toy!

by JOGOSO

Illustrated by James King

MAN'S VANITY must be fed, and woman is sometimes delayed, but inevitably. She sees the best feeder which nature has <level- through his vanity more easily than she would oped to date. With this great fact in mind we that of a person nearer her own age, so she seeks dare (We dare you-Ed.) to venture into the a freshman or classmate to be her future escort. science of why college boys date girls. In this The senior's vanity hurt, he finds another equally great field of science, as in any other field of social young and equally appealing girl to feed his vanscience, we must consider every condition which ity for a while. This same poor senior is the one might prove or disprove the theory. you will find at high school dances and parties,

First let us consider the college freshman: that being very indulgent toward the youngsters, and incurable romanticist just out of high school, receiving in return their expressions of admirathat vain and most worldly of men, that inimi- tion. Little does he realize that they would pretable jester. Throughout his school career this fer to dq without his "advice" and even his commaster in the art of "making Mary" has been a parry. Little does he realize that they admire woman-killer and a hero in the eyes of his con- him (?-Ed) only because he is older than temporaries. Entering college he believes that his former art will be nourished by new fields which he can conquer, by new girls who will idolize him. Here we see the master at work, being envied by classmates for his conquests, by " dates" for his popularity, and being revered by former friends who were unable to attend college . His vanity is being fed, and he is content with his niche in life. (Whee !-Ed.)

Alas, this type of glory-seeker is not limited to first year men. A deplorable number of sophomore, juniors , seniors and even graduates still seek to satisfy their vanity in the same way. In the upperclassmen this trait, if it survives first year shocks, becomes evident to the school at large. Most distressing of all in this group is the senior who thinks it his ironbound duty to t·score high-school girls to all college functions. This poor boy is never satisfied. (Whatta man -Ed.) He is constantly finding a new girl whom he thinks most attractive and deserving of an opportunity to meet college "men." He will bring this flattered child to a college dance. She will be very pleased, will look upon him as a benefactor of mankind, will feed his vanity until he is the most important man in the world. The showdown always comes, sometimes quickly,

they. He has convinced his vanity that he is their best friend and most needed ad visor.

Now let us consider why a college boy asks a college girl to a dance. Here we may have any of several reasons, but all are founded on his vanity.

Consider the boy who asks a very popular girl to a dance. Obvious motives (Aren ' t you forgetting one or two ?-Ed.) are an expression of superiority in getting a date with a girl others would like to date and finding out why she is so popular. Nothing pleases a college boy more than being chosen from many by a girl for her escort to a dance. He will soon be even more pleased , for her popularity is partially, at least, due to her flattering her dates. Another admitted reason for choosing a popular girl is that the boy will not have to spend his time introducing other boys to his date. Here we see his vanity creeping up when we realize he is very anxious to flatter other girls by dancing many times with them. Still another is that the boy is too vain to go the dance without a date. A very popular girl can keep him from going " stag" and at the same time not tie him down in the least. Think of it! He has been chosen from many, he has not been forced to go " stag , " he can honor many girls by dancing with them , and , above all, the girl very probably spends much of her time flattering him. Is it necessary to discuss why a college boy takes a girl to see an athletic event? Isn't it obvious that he wants to show her off to his friends? Isn ' t it obvious that he is very happy when explaining the fine points of the game to the poor little ignorant female? Haven't you , too , noticed how seldom he takes a girl to see a game about

which she knows more than he? (We thought "comps" had something to do with it.-Ed.)

Is it pardonable to discuss that type of inhuman person often referred to as a lounge lizard? Here we have a boy's ego being inflated to the Nth degree. He has a date with a girl who probably has been asked to a dance, party or movie, and she prefers to sit at home with him. It matters not that he asked for the date before she was invited to any of the other functions. (She should break it anyhow-Ed.) Then he can add to his own vanity by discussing his date ;1fterwards "I had a date with Mary last night. Had a swell time. No, we didn't go anywhere, just sat at home and listened to the radio. ( Ob, how you must envy me.)"

And now we come to why a boy "loves" a girl. He is the most blessed of all humans, if his love is returned. He has not been unwise. He has chosen a popular girl, and she flatters him by allowing her time to be monopolized. He is envied by all his friends, and he has been chosen from many by some very charming young lady. But , a.las, the course of true love never runs smoothly. There comes a time when she discards him. Here is the saddest of all humans, a boy who has been thrown over for another. Here is the desperate lover who would do anything in the world to win his fair lady back again, or to patch his selfrespect. Here we find the boy when he is most charming, doing everything prescribed by Dorothy Dix and by Emily Post, all to win his love back again. As often as not he is successful, and his wounded pride is healed.

Man's vanity must be fed, and woman is the best feeder yet devised by nature.

. .

by JOSEPH T. GREENE

IAM AF RAID My so beautiful tail wix eets silky hair and eets sinuous length frightens me My candle gutter and by ze light I see my , oh , so lovely tail wrap around my leg and caress , gently , ze flesh. Eet lak ' a lover when he touch biz mistress arm. Ah , ze passion , ze tender restrain eagerness. Eet thrill me. Y et , I know , I re alize zat he hate me He hate m e till he could crush , wiz all pleasure , ze very marrow from my bones. Eet is exquisite feeling , zat ecstasy Eet t itillate ze body and mak ' hem feel lak ' ze sweet surrender of lofe

But I am afraid ! He is so queer thing my tail. Sometime he seem to adore me ; sometime he seem to hate me; sometime he fight for me

I remember yesterday , ze arena at Proust where I mak ' ze wrestle wiz Zobombos, ze big , strong mans of all Europe . Eet is night. Ze stars seem lak' tiny , golden arrow points stabbed in ze p urple velvet of ze sky . Ze arena sh e glow whitehot wiz all ze lights an ze bla ck knobs of ze p eoples' heads extend for what look lak ' miles a n miles wiz zeir pale faces upturned and zeir eyes staring .

I climb into my corner and zen BONG .. . mak ' ze referee go ze bell.

Zat Zobombos is one beeg devil. He look lak ' z e papa an mama of all ze apes wiz biz beeg body a nd zat tiny head from which biz eyes glow lak ' re d-hot pennies . Wiz a roar zat sound lak ' thunder he leap across ze arena and grab at me

I, Pepo ze bool. am too clevaire. I drop to ze floor. I steek my head between he em legs. Zen Pouf I stand up. He lan ' s on zat small h ead wiz a thud zat mak ' ze arena lights shiver a nd ze crowd groan in awe . " Eet is nothing ," I say. " Pouf ... need ze lion be afraid of ze ape. " I wave my ban ' to ze peoples.

Zen I hear ze great roar of rage Mon Dieu ! Zat Zobombos is recover. I feel heem ban ' s around my neck. Zey crush until I hear ze happy voices of ze angels singing just inside ze gates of paradise. I think : " Eet is mos ' unfortunate for one so young , so handsome , to die ....

ZEN ... Holy Mary ! I feel eet ! My tail, m y so beautiful tail , I feel heem move .

He twist in ze bandage I so carefully wrap heem to my body wiz . He squirm lak ' ze little snake until I feel ze silky teep sleep out and touch my back. Ze rest of heem follow . . . .

Zat Zobombos ban ' relax and I see ... I see, zat tail so silky , so black , around Zobombos throat. Eet squeeze and squeeze and squeeze ....

Afterwards zey talk to me. Ze police say harsh words and pool what you call heem ze third degree. My body sink wiz exaustion. I talk wiz zem; I plead wiz zem ; I try to mak ' plain zat I do not control my beautiful tail ; zat eet has a mind of eets own. He is ze cause of z e trouble . He is ze murderer. Heern do it all heemself.

Zey believe Finally ze Commissionaire say : " Pepo , you mus' remove so doubtful an apendage. At once! Eet is unseemly for one in such a civilization to have a growth a a tail. "

" Monsieur le Commissionaire ," I answer " to you weel I be responsible. Tomorrow , as the heavens be my ·witness , weel I rem o ve my tail."

" Eet is agreed ," he answer .

I am afraid ! Tonight , my so lovely tail, wiz eets silky hair and eets sinuous length , frighten me. My candle gutter and by ze light I see my , oh , so lovely tail wrap around my arm and caress , gently , ze flesh. Eet rub my shoulder and zen eet climb and touch lightly m y throat So lak' a lover's kess eet it. So lak ' a HOLY MOTH E R MY THRO AT

by WILLIAM G. REn,vooo

The stars were like diamonds that glittered. In the jet black hair of night ; A tune by the breeze , in the leafy trees Did nothing to lessen my fright.

As I passed by the wall of the graveyard , Each tomb seemed to open wide : And give up the ghost of its long dead host Who for years had slept inside

One ghost stepped quickly beside me , And the rest brought up the rear ; I shivered and shook , as my hand he took , And leaned to speak in my ear.

' 'Have no fear of us ghosts ," said he ,

" We ' re only looking for fun ; In our graves we have lain , through the snow and the rain , And something just had to be done ! And now we are out for a night of play , To scare you was not our intent; We ' re taking this chance to have our dance , Before the night is spent ."

All of them grabbed me by the hand , As we danced by the graveyard wall ; And I , with these jokers, did rhumbas and polkas, Until we heard someone call.

" Come back to your tombs , you ghosts ," he said , " The sun is beginning to rise.

You couldn ' t be found still dancing around , When daylight fills the skies! "

The dancing stopped , and I found my self Being carried over the wall . They wouldn ' t let go , and I wanted to know , What was the cause of it all !

" We want you to stay with us ," they said , And a tomb slammed shut o ' er my head ! But ' twas all a joke , ' cause I suddenly woke In a sweat on the floor by my bed !

D I T 0 R I A L

A TTENTION MEN! This is your publi_1-1l cation. With the exception of one book review and two poems, this issue was written, illustrated, and edited by Richmond College students.

This is due, in part, to the uncooperative attitude of members of the Westhampton English Department who have refused to allow Westhampton Freshmen to contribute to The Messenger. Not only is The lvIessenger suffering from this policy but other extra-curricular activities of the University are being stifled by the administrative regulations of Westhampton College which discourage and prohibit Freshmen from participating in newspaper work, dramatics, and other activities. Since The Messenger does not require of its contributors a definite schedule of work and time, but only acts as a medium for the publication of literary efforts composed at will, it should not be placed in the same category as the other activities so regulated.

At Richmond College, Freshmen are urged to participate in extra-curricular activities. The Administration, realizing the importance of activities in rounding out a college life, is cooperative in seeing that this phase is given a fair start.

The results of adhering to this policy are very much in evidence in this magazine, as this issue is almost entirely comprised of the work of Richmond College men, whereas, by the same token, it is obvious that the policy pursued by W ~sthampton also has its results-negative!

Throughout the nation today, institu- . tions of higher learning are placing more and more emphasis upon those features of

collegiate life which enable a student to make contacts outside of the classroom and to demonstrate an initiative unprodded by professorial assignments. Perhaps this may, to some extent, explain the fact that Westhampton has been standing still, while every other branch of the University has been expanc!ing both in enrollment and activities.

So far this editorial has been confined to a discourse as to the reasons for the literary inactivity of Westhampton Freshmen, but when we come to consider the creative stagnancy of the upperclasswoman, who last year were able to fill only one issue of their private publication, we must confess that we are a bit befuddled. It may be that their forced inactivity as Freshmen has instilled in them that attitude of indifference toward University activities which is so apparent in the large majority of Westhampton upperclasswomen. If this be the case, it is further proof of the evils which result from the above mentioned policy of suppression.

Without the support of Westhampton College, The Messenger cannot continue as a University publication. It is farcical to call it such at present. Be it then re_.solved: (I) that the Westhampton College Administration should enlarge its conception of education beyond the scope of the Latin Grammar School, ( 2) that Westhampton upperclasswomen should throw off their literary lethargy.

Until this is done the University of Richmond shall continue its tug-of-war between educational progressiveness and reading, 'rithmatic, and little writing.

THE writer of this plea is, at the present moment, most cold. Outside the snow drifts ruthlessly to and fro. Every now and then, an especially devilish little :flake sneaks through a broken window pane just behind me and settles on my neck. Alternately, I stuff paper in the windows and cigar butts in the cracks in the wall. Abe Lincoln had nothing on me. This building in which all the nonathletic activities of Richmond College are housed is known in polite circles as the Playhouse. - outside of said polite circles, however, you may hear the place more adequately described.

Across the lake, the weaker sex are now in possession of a palatial activities building. We of the supposedly more hardy sex, however, must continue to suffer the hardships and privations of "the barn.'' We are a long suffering people. Every year we are promised an activities building. Every year we return in the fall and busy ourselves rechinking the Playhouse e' re winter comes.

Now we of the stronger sex should be able to accomplish what have been done across the waters. But we cannot do it by shivering in the Playhouse and swapping stories about those heavenly activity centers which we have seen elsewhere.

TThat massive structure across the way was not graciously dropped in the broad lap of Mater Westhampton. Alumnae and students alike had to struggle and fight for years to achieve that ambition. For years we have had the ambition, but no fight.

Each year the student body of Richmond College is comprised of a larger number of "town students." And with the growing number of commuters, we have a growing need for such a recreation and activities center. These gentlemen, having struggled through their daily diet of classes, hunt down their respective means of transportation and wend their way homeward. No school spirit, we say? Why should they remain on the campus? Those who are not members of fraternities must either park on that most uncomfortable ledge in the Student Shop or take refuge in the (Wh) Y Building, and listen to that gallant little radio wheeze and stutter.

If we are to hold together our campus population, we must have such a building. If we are to retain any vestige of interest in campus affairs, we must have it. If you want to render the greatest possible service to your Alma Mater, fight for such a building!

HE editorial policy of The Messenger, as set down by the staff, is not one of destructive criticism. The editors of The Messenger are not cynics. They are healthy young men and women, with ideals which coincide with the principles and precepts of the University.

Any criticism which they level at the University or any of its separate parts, although the criticism might be couched in terms to suggest that it is destructive, is

·merely intended to call attention to certain problems which arise. The staff is not made up of radicals. It is their desire to see the University prosper and go forward in each of its units. But only by calling attention to the things which need remedying, can this desire be realized.

We, therefore, reiterate, the policy of The Messenger is not one of destructive criticism!

by NOAH E. FEHL, Jr.

THE basis of man's religious activity has been variously defined by a multitude of men. Each has written into his introduction that quality of Faith which he , himself , has discovered to b e fundamental and vital. Although my faith h as been very nicely described in many of these definitions , I should like to suggest a slight shift o f emphasais

I believe that the basis of man ' s religious act ivity is selfishness. I see God as the Great Designer who communes with individual man through an appeal to innate selfishness in an attempt to draw mankind toward His own p erfect ion Thus God has urged man onward in His g reat evolutionary plan by teasingly dangling an apple in front of him and threatening , cracki ng a stick behind him. Apples and sticks , rew ard and punishment are fundamental and vital i n religion .

The Hebrew in his story of creation writing of the first communion of Jehovah with Adam t ells of an apple : " . . . for in th e day that thou catest thereof thou shalt surely die. " Jesus confr onted with the despair of His disciples comforted : " In my Father ' s house are many mansions I go to prepare a place for you. "

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in his Education o f the Human Race after tracing religious development by the evolution of accepted forms o f reward and punishment repudiates the system a s selfish and inadequate as a basis for good cond uct. Lessing concluded these obs ervations with w hat he termed a premature birth of the doctrine o f doing good for good ' s sake alone . This he insisted was not selfish and thus higher and nob ler In this Lessing was writing nonsense Man, being a rational creature , acts according to reason . Each act, although perhaps prompted by p hysical environment , has its origin in conscious w ill, and conscious will is interested in goals

If by righteous acts man is introducted to a more abundant life , he will so order his will. In describing this decision as the choice of good for its sake alone Lessing fell into error; for , upon this definition he distinguished between the motive for the good life according to his own ideal and the motive in the ethic of the eighteenth century churchman on the basis of degree of selfishness

Both Lessing and his heavenbound brother walked uprightly because they were to be rewarded for their effort : Lessing in a more a bundant earthly life , the churchman in a blissful eternity. The difference here to be distinguished is the kind rather than the degree of selfishness. Specifically , the fault of Lessing's reasoning lay in his arbitrary condemnation of selfishness as sinful.

Selfishness , the basis of man's religious activity , is not sinful It is life ' s vital impulse that fosters activity It is the motivating power in life

In the lower levels of zoological life selfishness is described as the equivalent of the Law of Self Preservation. Here it is a :fixed fool-proof force In man it can be cultured toward a definite design preconceived by conscious will. Thus ethics becomes the utiliziation of selfishness , life force , for the achievement of moral values , and thus our ethical evolution involves the nature of this utilization and can be traced by it.

In our ethical evolution thus far we have become acquainted with four stages.

The morality of the pastoral Israelite who was interested only in the immediate dispensation of Jehovah's justice is representative of the first stage. The wandering Jew was an extremely practical man. His selfishness demanded immediate returns. It was the God who favored him in battle over his enemy for his good deeds or struck him down by lightning for his evil that com -

manded his respect and worship. Under this ethical economy David suffered illriess in payment for his untimely interest in a soldier's wife. Under this code also poor Jonah was condemned to incarceration for a period of seventy-two hours in the dark damp belly of a whale.

It was for that "crown of glory" at the end of the course that Paul "fought the good fight" and "kept the faith." It was the awful vision of a hell of very nearly literal fire that John Bunyan and Jonathan Edwards held up before their hearers to whip them into careful recognition of the "P's and Q's" of Puritan morality.

In about the year 30 A.D. Jesus devised a concrete plan for the direction of human selfishness toward the reality of a more abundant life for all mankind to be achieved through individual effort. This plan we have come to call Christ's Gospel of Salvation. Its significance for us here is as the introduction of the third stage in our ethical evolution. Jesus preached a gospel of social salvation through individual regeneration. It might be worthwhile to review briefly that gospel now.

The vital impulse of the individual when it first manifests itself in the soul of the infant, the selfishness of man in its natural state is evil. This premise of Christ's Gospel has its ecclesiastical statement in the doctrine of Original Sin.-''As in Adam all die .... "* Jesus meant by this that the course into which instinctive selfishness will naturally fall invites damnation rather than a more abundant life. The Law of Self Preservation in its primitive form becomes the Law of Self Elimination in human society.-"He that would save his life shall lose it."

Christ directed His emphasis upon a new kind of selfishness. His appeal to man's vital impulse when He said: "It is more blessed to give than to receive , " was different from that of Jehovah's promise of armed victory to Israel. Jesus was inviting men to taste of the spiritual riches of a sacrificial life.

*The Gospels do not record a definite statement by Jesus concerning original sin However, His insistence upon man ' s acceptance of His gospel as the only salvation certainly does provide authority for this statement of Paul's.

But He also had a message for the more practical man. To the economic and social reformer he said: Do not require the immediate satisfaction of your injustices. Do not be content to pay back in the same terms with which you have been unjustly dealt. If someone slaps you on the cheek, do not merely return the slap. Make the man your friend. Then you will receive a worthwhile compensation.

To both the spiritual and the practical man Jesus made this further appeal: If you live wisely; if you make men your friends and thus create happiness and love rather than hatred and pain, then you will be recognized by God as one who is helping Him in His great evolutionary Plan and you will receive as your reward a glorified immortality.

Although Jesus' direct emphasis was upon paternalistic sharing in order to provide for the then poor, He put into His Gospel a capacity for adaption to the fourth stage of ethical evolution-co-operative sharing.

Today we are no longer satisfied to put our trust in paternalistic sharing, to be content with the meager returns of philanthrophy. We will not indorse that ethic which protects rugged individualism on the grounds that it sacrifices in philanthrophic endeavor. We demand that the sacrifice be made in the beginning, that profit making be prohibited, and that a fair reward for earnest effort arising from the equality of opportunity be made the rightful privilege of every man.

Jesus had a firm conviction that such an ethic could have a practical application in human society through individual regeneration. But in what manner does this startling right-about-face conversion from instinctive self preservation to unnatural self sacrifice occur? A desirable faith is our answer. And that faith is the obsession that the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the salvation of man through the direction of selfishness toward self sacrifice, is the only way to a more abundant life.

The person of Jesus Christ is the proof of His Gospel of Salvation. As such we must accept Him. Jesus is our Saviour.

by J. T. RATCLIFFE

-..Towtake your time ," said Doctor Mornay l " Just tell me the whole story from the beg inning ."

A lean , haggard man , his sens i tive young face a mask of misery , old and lined , haunted and I h opeless , looked across the desk at the eminent p sychiatrist and started to speak.

His story , told in a swift rush and in a curious me tallic voic e, without break or hesitation. g r eatly interested the noted doctor , accustomed t hough he was to pitiful tales of human suffering. It interested him yet more , ne x t day , when h e learned that for some unknown reason his p atient had shot himself during the night

He told the doctor that his name was Jones a nd that there was something he had to get off h is mind.

And a tragic thing it was to the doctor , prep ared as he was to hear a dark story of vice , crime , ruin and downfall. Tragic , pathetic , p itiful and ridiculous , like a torrent , the absurd story came

" Looking back and considering the affair ag ain ," he said , " I am still of the opinion that I d id my duty and nothing more; that I acted like a man and like a man of conscience

" Only the moral coward says , ' Am I my b rother's keeper ?' My mother and my saintly u ncl e had trained me all my life to have a sense o f r esponsibility to my neighbor and myself.

" Therefore I will tell the exact truth about w hat I thought and did ; and you shall decide as to whether any high-minded and morally coura geous person could have done otherwise

" I was brought up by the best mother any m an ever had and by an uncle , ( a priest) , whose chief regret , I think , was that burning at the st ake had become an outlawed pastime. This u ncle wished to go abroad to p erform a labour

o f love among the heathen and perhaps find for himself a martyr ' s crown .

" He and I both left for India on the same boat ; he to try to join the holy army of martyrs , and I to join the Indian regiment into which I was transferring. The fact that I was to travel with this good man and not be left to stray alone into the evil atmosphere of Gibraltar , Malta , or Bombay was a great joy to my mother.

" On that thrice accursed boat I saw my new colonel's young wife kiss another man I saw him with his arms about her waist. I saw him go into her cabin , when the colonel lay snoring in a deck chair

" When I heard them plotting together to sneak off at Port Said , on Christmas day , my struggle with my conscience was ended. My conscience had won , and I knew I must face the hateful and distasteful duty of telling the colonel the truth. Yes , I was a ' Young Man with a Conscience !' But I shall tell the facts as they occurred.

" My new colonel, who was re t urning from leave and his honeymoon , was a stern and unapproachable man with whom few would have dared to jest or trifle.

" His bride was a beautiful y oung girl who might easily have pass ed for his daughter-as merry , frivolous , and gay as Colonel Gordon was sober , stern , and hard . Opposites attract-and he worshipped her.

" I admired her greatly, and she was very kind to me on the few occasions on which I spoke to her. Sometimes I felt I would rather be sitt i ng b y her than eternally walking and talking with my saint-like uncle

" But I was far too much und er his control to think of breaking away . He had educated me from childhood until I went to Oxford , and had · 19 ·

even followed me there and continued to exercise his powerful influence upon my character. I was with him daily, and, although I was now in the army-with a university commission, as my mother would never think of allowing me to undergo the hardships of the British Military Academy-and was about to enter the wicked world. he was still with me. Yes. I was a 'Young Man With a Conscience.'

"While I did not desert my worthy uncle in order to enjoy the company of the Colonel's lady, yet, my eyes, doubtless drawn by the devil, were ever upon her.

"When the passengers came on board at Marseilles, a chain of events leading to a calamity was set in motion. Walking the promenade deck that evening, I noticed that one of the new passengers already sat beside her, and I was sorry to see her accept and smoke one of his cigarettes. He was, like her, young and frivolous, and most unlike the dour-visaged Colonel.

"They made friends very quickly and were always together. They were a splendidlymatched couple, and she seemed far more bright and happy in his company than when with her husband.

"But the Colonel seemed content. He would sit in the writing-room scribbling away all the morning on a military text he was writing; sleep all the afternoon; write again in the evening; walk round and round the deck, eat, and go to bed early. I confess I envied the handsome, merry boy and that I often longed to talk to someone other than my uncle-someone like this laughing, frivolous girl, for example.

"On the second day out from Marseilles I received a terrible shock.

"Coming suddenly around a corner, I almost ran into her deck chair as she withdrew her hand from her companion's with the words:

'' 'You' re a darling, Bobby! you shall have a hug for that!'-and her eye met mine, even as she spoke. Did she look confused or guilty? Not she! Her gaze was perfectly untroubled, and it was evidently nothing to her that I must have heard every word she said.

''As for him-he had the boldness to murmur quite distinctly, 'Hold up, old boss!' as I stumbled and blundered past.

"Of the three, I would certainly have struck an onlooker as the guilty one, as I flushed and hurried away.

"Think of it! Married a month , and the man had not been on the boat three days! I was shocked to the point of physical nausea.

"Should I tell my uncle?

"Should I not tell her husband? Was I my brother's keeper? I knew I was. I knew it was my duty to save the Colonel, his wife, and the young man 'Bobby.'

''But I knew I was not brave enough to do it. And the devil tempted me by whispering: 'Most ungentlemanly of you to tell taks on a lady!' 'Colonel Gordon will kick you downstairs.' And even: 'Ivlake love to her yourself, since she's such a flirt!'

"That evening, I went on deck. As it was a glorious moonlight night , I decided to go up into the bow and watch the knifelike stem cut the phosphorescent waters.

"I ran down the companionway, crossed the deck, and climbed the ladder to the foredeck.

''There they were, leaning on the rail, and his arm was around her waist!

"On deck early next morning I saw them meet -and embrace! During that day, the young man (his name was Harrison) cultivated the society of other young women a good deal. He was a regular Don Juan. But, just before dinner, as I sat reading in the lounge, Harrison and Mrs. Gordon came in and sat down close beside me, and made their arrangements for going off together, on Christmas day, at Port Said.

''They spoke with shameless openness and lack of decency; and I heard Harrison say: 'Slip away while he's writing then,' and bring all the cash you can; 'you'll want it at and I am nearly broke. I can't keep-' and her reply, with a heartless giggle; 'Suppose he comes after us?'

"I jumped up and said: 'Pardon me-I am hearing much of what you say and I will-'

"With brazen nerve, Harrison interrupted me with, 'Sure thing, old boy! I'm sorry our prattle

disturbed you,' while Mrs. Gordon stared at me as if she thought I was crazy.

" I rushed to my cabin and spent the whole day and the next night trying to decide what to do. My conscience tortured m e all night.

" But in the morning , I arose calm and decided , a nd dressed as if I were going to my execution M y conscience had won , and I w as going to do my duty no matter what it should cost me . I h ad decided to tell Colon el Gordon in the presence of his wife and Harrison .

" As the passengers came up on deck , I app roached the Colonel, with whom were his wife a nd Harrison , and said :

" ' May I speak to you . sir , on a most importa nt matter-and Mrs. Gordon and Mr. Harrison be present ?'

" The Colon el stared , and started to speak and m y heart sank within me .

"' Well ? What is it ?' growled the Colonel.

" ' It would be better if we were alone , sir ,' sa id I.

" ' Come in here ,' said the Colonel, entering the empty smoking room

" ' Sir ,' said L ' it is my most painful duty to tell you , that I have seen this man kiss your wife , and have heard him arranging to go off with her ;:it Port Said. I have done my duty , my conscience is clear .'

'' The Colonel started . His wife and Harrison looked at me open-mouthed . Thus we stood for what seemed centuries until suddenly Harrison fell on the sofa and buried his face in a pillow ; the Colonel raised his hand-not to strike , but to cover his face ; and Mrs . Gordon burst into screams of hysterical laughter.

" I had obeyed my conscience at what cost !

'' And then the Colonel turned to his wife and the ' other man ,' and said :

" ' Is this true? If so , you are not to spend more than ten pounds in the shops Alice And , as for you , Bobby , if you have b een kissing your o wn sister for a change , it's certainly a change for the better !' ''

by HERBERT HEADEN

MEN in the box-cars had rott en hors e m eat for dinner. Hooting and b,dlowing they revolted. They tramped forward and surged a round the parlor coach.

A big , burly private assumed command , gave te rms to the officers : surrender or be burned to d eath Gun butts smashed against a box-car , they b roke up fuel to start the fire.

Only when the parlor car had become a roaring inferno did the officers attempt to escape. As each o ne jumped an automatic coughed They sprawled horribly.

Within six hours Cossacks rod e down th e mutinous regiment, drew it up into two long rows . " Every third man in the front line take two paces forward. '' A young corporal was a third man-terrified and biting his lips. Behind him was the big , burly private .

Pulled back with such force the corporal fell into the ditch alongside the railroad tracks He lay there trembling , heard sixty - three men scream and die

That night he found the dead private , ten slugs in his chest and face

OLAF NELSON leaned heavily against his wagon and gazed resignedly at the carcass of one of the plough team .. Old Bess hadn't quite been able to pull Mill Moutain with the timber load; her legs had crumpled under her as she neared the top . After all, Bess wasn ' t Mohammed. And now she lay dead before him , just as his A unt Matildy had died-with her shoes on. Olaf Nelson was a dejected man.

Bess ' accident was in April. The preceding October Ollie, his eldest,-the one that was such a hand at the haying-stepped on the scythe blade with his bare foot , his good foot, and took sick with blood poisoning. When he died, Olaf was broke up terrible, but then not half as broke up as Ollie But Olaf, gritting his tooth and shifting his quid, didn't let on much. He just said he reckoned Ollie would like Heaven better anyway because he had been such a solemn looking boy, with his wooden leg and glass eye. Olaf had made that wooden leg himself out of the telephone pole he chopped down out in the pasture , and when the telephone people got nasty about it he took out after them with his old twelve gauge. All this passed through the mind of Olaf Nelson as he stood looking down on the still warm body of Old Bess. -·

Then came a hard winter when Olaf had a time managing without Ollie. By March , though, he figured he had come through the winter pretty good , until one day there came a uncommon late blizzard that took all his cattle save one old steer that was too blind with the staggers to leave the barn and also the hired man who was blind with the staggers from Olaf's moonshine. Olaf fired him anyway the next day and sold his farm to some city fellers and moved with his wife to a little shack further back in the brush. These

days he didn't smile much. He couldn't make out how it was right for him to suffer all this misfortune, specially since he had gone to church every Sunday since he was seven and was a Godfearing man and always was a good husband to Maude; hadn't ever beat her much except a few times when she had his breakfast late and put vinegar in the scrambled eggs just for fun. Maude sure was a card . But Olaf Nelson was sad and couldn't even smile anymore.

When spring came on , Olaf got a little bit brighter. His early potatoes didn't show any signs of blight yet, and eggs were bringing thirty cents, and Maude's case of itch was dying out. In fact , she said later , between times at the frying pan turning the sow belly, she thought everything would have been all right by the next harvest if it just hadn't been for the nag ' s death.

After Olaf had covered Old Bess with his lumber jacket, he bent over, his joints creaking a mite, to shove her off the road in the bush. Olaf Nelson was a very large and very strong man. When tears began to come to his eyes, he tried powerful hard to blink them away. He reckoned he was just a sentimental old fool. The mare had been well nigh dead with the heaves anyway. Then, strangely, he couldn't bring himself to touch Old Bess. Something seem to snap inside him. He guessed he'd have to take a dose of sody when he got home. He turned away and began to sob. Every since that day he has been a quiet, bleary-eyed , hare-lipped, paralytic, doting old man, who mumbled to himself and won't wear lumberjackets any more. The villagers, who wears boiled shirts and store clothes and change their sox every winter , say old Olaf Nelson is tetched in the head. Maude has to take in washington to help out ... C ' est la uie.

• 22 ·

by JOSEPH TURNER

Illus t ra te d by Jame s King

BE STO OD under the con e of harsh light that illuminated the street corner and counted t he change from his pocket There were two n ickels , six pennies and three quarters-ninetyo ne cents in all. Just enough for bus fare both w ays with something left over to buy Anne a small present.

He grinned crookedly This was the last of bi s pay check . Well, h e didn ' t mind if it made he r happy The crookedn ess of his g rin smoothed i nto a semblance of serenity as if , for the time , li f e regretted the sorry tricks it had played on o ne so young and was trying to repair the dama ge etched on the pale cheeks and erase the shad ows beneath the blue eyes.

H e moved over to the confectionery window a nd let his eyes rest on the objects colored so de licately , by the soft glow of the indirect lightin g There was candy in long boxes tied with ex p ensive looking blue and pink ribbon and m arked accordingly Placed on a throne of ruffled satin were tiny elephants , trunks upcurled , m arching in unending succession to an unknown destination. The price tag fastened to the leader' s ear read five dollars In a far corner , half h idden by the draperies that formed the backd rop , stood a tiny little dog A toy Scotty ! His saucy glass eyes sparkled . From the tip of his impudent nose to his wagging tail he radiated fr iendliness

Tommy grinned in sympathy Somehow the appeal went straight to his lonely heart . Imp ulsively he entered the store .

" How much ," he asked , " for the puppy dog in the window ?''

" Eighty cents ," said the man . ··want that I should wrap heem up ? Y es ?"

" Y es ," Tommy said. " Don ' t put him in a ba g Wrap him up nicely ."

' 'Can do ,'' said the man. He opened the sho wcase and with clumsy hands removed the dog and began wrapping it in white paper.

Tommy reached out

" Let me ," he said. " It ' s a ver y personal gift ."

" Don ' t care ," said th e man. " Eighty cents please."

Tommy handed over the money and , wrapping the dog carefully , almost tenderly , in the paper went out with the package to resume his vigil at the bus stop.

Eighty cents-he ' d have to walk home . W ell , that didn't matter if Dear Lord , please make Anne like this puppy dog ....

He huddled in his thin raincoat as if the cold , clear sky was clouding over Dear Lord

It was almost a quarter to nine when he descended from the bus in front of Anne's house He waited until the tail lights dimmed in the distance. Then , shivering , he removed his raincoat and tucked the package deep in its folds . It was all right to give Anne the football extra but the family might object if he brought her gifts too frequently. Families were funny that way . He and Anne weren ' t engaged y et-that is openly They had an agreement , tho ug_h

· 23 ·

He threw back his shoulders and marched across the street to the hedge-protected yard and up the walk to the porch. He pushed the bell Somewhere in the rear of the house a tiny jangle protested the thundering piano music in the front room . Old Man Stewart was playing again . Trying to drown his sorrows with sound. Wish to heaven he ' d stop . H e pushed heavily on the bell.

Its summons was disregarded . The music went galloping on , each bass note trying to outdo the other. Gradually it slid into Rachmaninoff's de di-de di dum .

Tommy shivered He ' d have to put the coat on soon if someone didn ' t answer the door. Oh , Lord , he prayed , make Old Man Stewart come out of his trance. It's damn cold out here

For the third tim ~ he touched the bell. Almost before the jangle ceased the door opened and Anne was framed against the glowing brightness and warmth of the room .

" Hello Tommy ," she said aloud Then whispered , " Darling ."

Tommy stepped inside. " Hello , Sorry I'm late but I missed the first bus. Could ' nt help it. "

She walked over to the chesterfield and sat down

" I just finished dressing ," she said ' Tm just as tardy as you are. "

Tommy looked at the piano

" Good evening , " he said.

Abruptly the music ceased .

" Good evening ," an automatic smile creased Mr . Stewart's face . He bowed his head and arising from the piano swept in a running walk across th e room and up the stairs.

'' Well- " Tommy said.

" Oh don ' t mind dad. He ' s in one of his musical moods tonight. He's like that. Sit down."

Anne patted the cush ion beside her. "He needs a little football in his blood ."

Tommie picked up his coat and fumbled in one of the pockets

" That reminds me ," he said , " I bought you an extra. "

" Oh , Darling. " Th en softly " You always think of me. "

Tommie grinned. ' Tm selfish , " he said , " I like to see you smile . .. Cigarette? '' He pulled a mashed package from his pocket.

" Um , Camels. "

" Yeah. I had an idea that you liked them better than my usual brand "

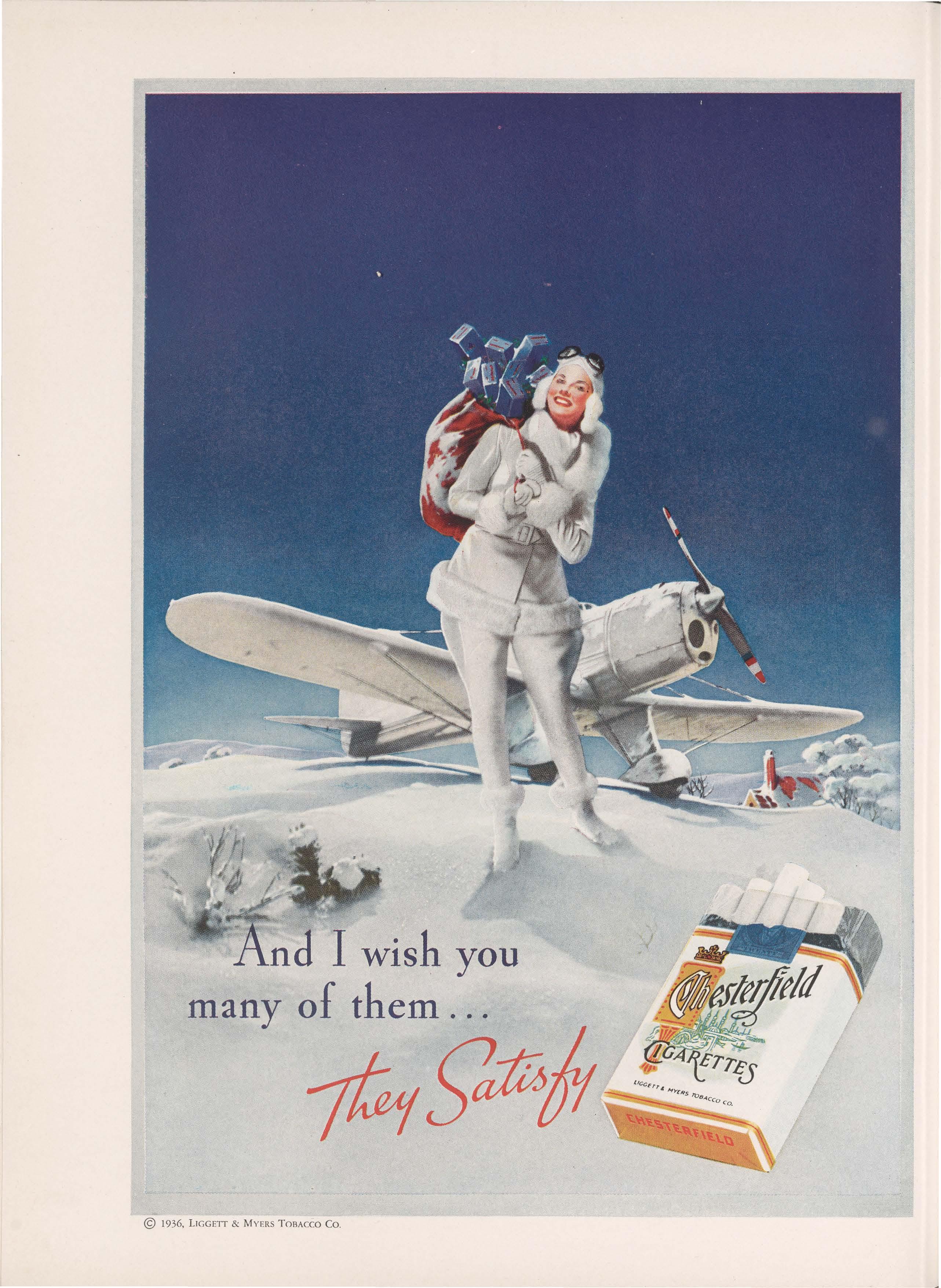

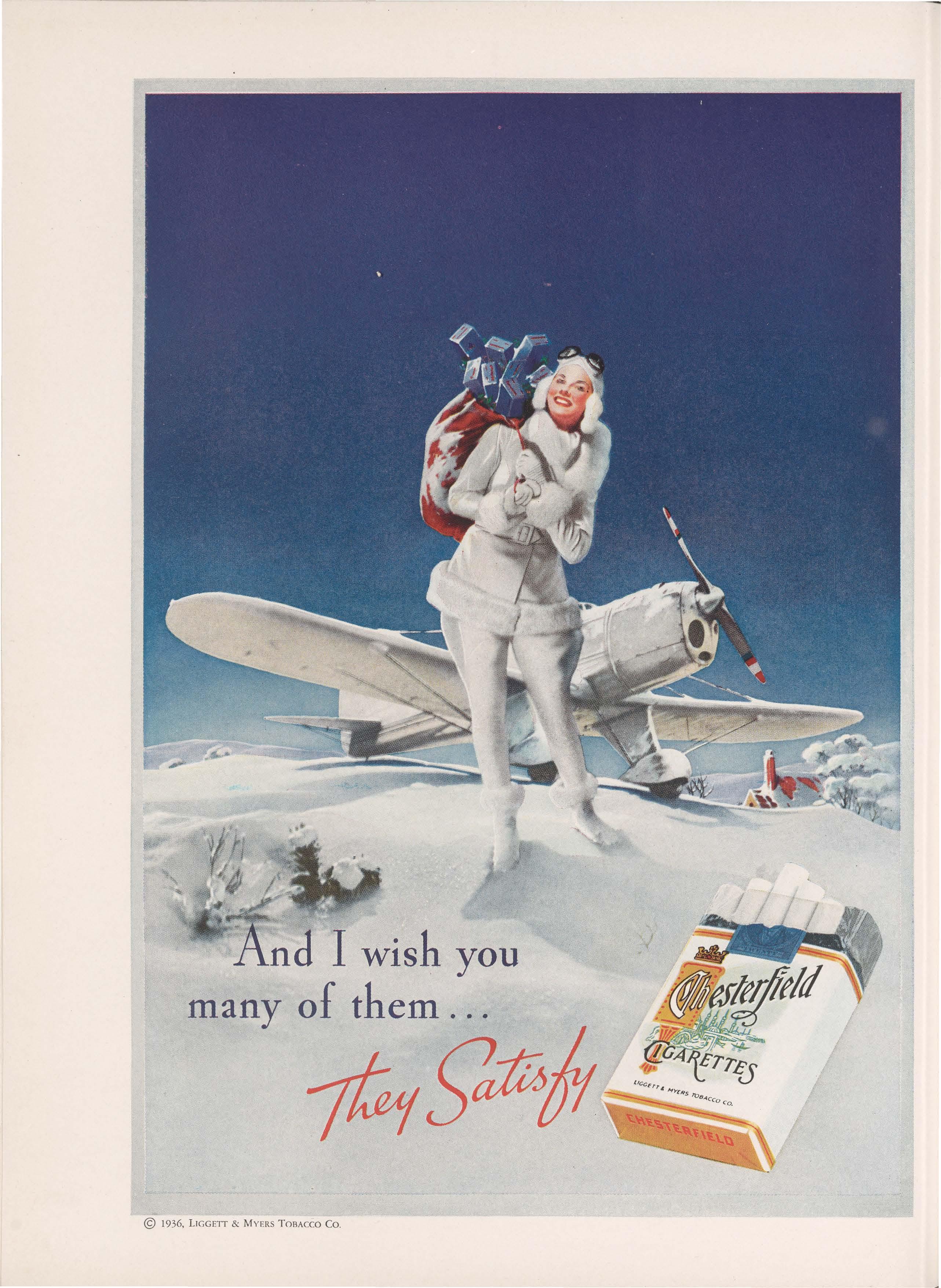

" I like Chesterfields too ... . "

"Well?"

" Well?"

Suddenly they both laughed

Anne tilted her face , " Kiss me ," she commanded

" Yes , Milady . To hear is to obey . "

" Ob ? I d ' l'k " ey. on t 1 e.. ..

Tommy pressed his lips against the smoothness of hers It was unbelievable the sweetness , the tenderness that hovered there. It was like the delights that were vaguely promised for heaven only heaven was so far away and this was real. This was heaven . Slowly he lifted his lips. "Oh , Anne ... we can't ... . "

" Can ' t what , darling ?"

" Keep . . . keep on with this everlasting waiting." He stopped short. " Nothing!"

Anne ' s eyes searched his face '· Go on ! Tell me !'' she commanded .

" Oh , this waiting. This everlasting waiting ! We can't go on like this forever. There ' s got to be an end sometime . We can't get married. I can't get a decent job Soon you'll be bitter too. But , not against life , against me . Bitter because of the chances you've given up and because I'll have nothing with which to fill in the empty spaces . Can ' t you see, Anne .. .. "

Anne closed his lips with hers. For a long , long time she held him close as if to dispel his fears with her nearness. Finally she disengaged her arms.

" Tommy , " she said softly , ' Tm funny . I don ' t understand myself sometimes. I'm selfish, cruel but Tommy I do know I love youand I'll wait forever "

Tommie touched her cheek with his fingers.

" And two days ?" he asked in sad whimsy .

" Four days, if you insist. "

· 24 ·

Tommy stood up. But I mustn't insist, he thought. Aloud, he said, "Four days then, Milady."

He walked over and, picking up his raincoat , r emoved the package. " Something I brought y ou. Don't look now. Wait until after I'm gone.''

"Please ... Tommy?"

" Not even with pink sugar! After I'm gone."

"Tommy, you're mean . " Anne moved into t he circle of his arms. "Don't go It's early yet."

' 'I've got to, hon," he said. He looked deep into her eyes. Seeing there ... ! Slowly , tenderly , h e kissed her.

" Goodbye, darling." He opened the door.

" Goodnight, hon ... until tomorrow. "

He stepped into the night and as the door closed behind him , shutting Anne and the warmth and the cheer from the darkness , he went to meet the inevitable.

If Anne wouldn't give him up then it was his duty to make things right

" Damn them!" he shouted. He turned and savagely shook his :fist at two old men in a passmg car. " Damn the whole works! They ' ve messed up everything , and we pay Oh , Anne "

A low-throated whistle sounded through the night. Tommy , for an instant, looked at the lighted window in the house behind him, then turned and tramped steadily in the direction of the freight yards with shining rails to the west

by MARGARET CARPENTER

To what avail is your loveliness ?

Even it , too , will crumble to dry dust , Lie in the earth dull grey and colorl ess Deep under each new year' s relentless rust. What then is life ,- but one pale blo ssom blown To sudden beauty , which must shrink and die ; A violin 's swift ecstasy of tone , A flash of sudd en silv er in the sky ? , 25 •

by LLOYD A. ROWLAND

Robert ( Bob ) Horton ; age thirty years ; height fiv e feet eigh t inches ; weight one hundred six t y-fiv e pounds ; dark complexion and hair ; normal features ; left ear-lobe missing Want ed on a charge of murder by the Denver , Colorad o, p o lice force.

THIS terse notice and the picture of the criminal under it were being carefully noted by a young man in the post-office of Greenriver , Utah The observer instinctively yanked the tattered hat which was crammed on his head still further down on the left side. The brim was turned down , and the hat nearlv concealed the ieft side of its owner's face. The rest of the man ' s ensemble was in an equally dilapidated state.

'.Bob Horton moved away in the deepening twilight. There was no alternative for him except to go west. He had a few vague plans in mind Somewhere in Oregon he might settle down to honest pursuits until his name would be put on the list of the vanishing thousands who disappear every year and are never heard of afterwards. He wandered aimlessly for a while and then directed his steps towards the railroad yard. There he met a disconsolate looking bum whom he questioned.

" When is the next freight , buddy?"

" One going east at two-thirty in the morning , and another headed west tomorrow noon."

It was a warm summer night, which might have provoked a friendly conversation if these two had had anything in common or if either had been socially-minded As it was , the two drifted away from each other without any other comments Looking for a place to spend the night , Horton saw a solitary box-car on a side t r a ck . Since the past forty-eight hours had given him only a few intermittent snoozes, Horton crawled back into the empty recesses of the car and v ery soon was plunged into the sleep of ex-

ha ustion. Towards morning he began to toss and dream. Fantastic pictures of his victim and scenes of the crime from which he was running away flashed intermittently across his mind. The last of his dreams was even more realistic than the others; Bob Horton had been captured and was riding back to Denver to pay the penalty. The rumble of wheels and the steady puffing of a steam engine seemed to be reminding him that he was on the way back. The noise seemed to rise in a crescendo until Horton finally awoke. It was pitch dark, and cold perspiration covered him.

"How crazy a man's dreams can be!" he laughed. But then there was a rumbling noise ; he was on a moving train. For a moment the darkness and his drowsiness joined in a coalition to defeat his slowly returning wits. First they were successful ; then Horton began to reason out where he was and under what circumstances he was there.

" The solution is simple , " he thought. " A section hand has shut the door , and wh i le I was still asleep , this car was attached to a freight." There was little to worry about; even though the train was probably heading for Denver, Colorado , it wouldn ' t take three minutes to jump off. As his eyes accustomed themselves to the darkness, he was able to discern the pale light of dawn seeping through the few small cracks and around the door. All there was to do was to open the door , pick a soft landing spot , and jump Horton arose from his uncomfortable bed of wrapping paper and crossed over to the outline of the door. His first push was not strong enough to budge the massive door. A little nervous , he gave a weak lunge in order to start the rusty, outside rollers. The result was a little as before. Horton stopped to catch his breath.

" The door is probably locked on the outside. ,. 26

If I am unable to free myself, the Denver police undoubtedly will catch me and recognize me when we pull into the Denver yards."

Horton tried to be calm, but the blood mounted to his head. He rushed at the door with a mad desire to break it from its hinges and gain freedom. The hard iron-reinforced pine was not to be broken by the comparatively puny strength of a man, and the door did not budge an inch with the impact. Beads of perspiration began to cover the captive who did not have a guard, who seemingly little needed one. Frantically , he redoubled his efforts to break out of his dark moving cell. He swung his sturdy frame time after time at the door but to no avail. At last he fell exhausted on the floor . His bruised muscles did not actually hurt but through his subconscious mind they gave him the feeling of f rustration , despair , something akin to what o ne buried alive must feel. At this moment it was not the gas-chamber which was awaiting him that he was thinking of; it was the horrible prison he was in and the immediate results of his captivity. Again he tried forcing the door as furiously and frantically as before. He was a w ild beast taken from its habitat and placed in a new environment , a cage. After repeated failure at the door, he tried the side of the car, w hich was constructed with material a little less suited to contest with time , and a ray of hope burst into his undertaking . A few moments of r easoning told him , however , that his present approach to his problem was wrong and futile. I t was maddening to stop his work in order to consider his situation and to determine the most logical course to follow , but he realized that this w as what he had to do.

Horton reasoned. Undoubtedly the train was beaded for the east and Denver, because the westbound freight was not to pass through Greenri ver until mid-day. It was still early morning n ow. As near as he could :figure Greenriver was o ne hundred and seventy-five miles from Denv er, which was about a seven hour trip at the r ate the slow freights travelled over the mountains. But if , as he had been informed , the eastb ound came through Greenriver at one-thirty,

he had slept most of the journey . The height of the sun , which he viewed through a tiny crack , indicated that it was probably about seven o ' clock . That would leave him thr ee-no , only two hours to break loose.

Suddenly Horton felt the surge and pound of his heart which had a few minutes prior driven him to such a waste of energy. He managed to conquer the impulse this time , however. Odd how his native instincts and fears would act so contrary to the very thing he desired most , freedom. But enough for logic!

Horton rose and made a careful circuit of the car, searching for an easy way out and some manner of implement with which to work. The car was completely empty ; there ,-vas not even a loose board with which to pry. The only thing that would be of any use to him was the small two-bladed , pocket knife , scarcely larger than a penknife, which he carried with him. Whittling his way out with that would require two days, not a brief two hours. But then there was one possibility. Freight-car doors are usually secured by a two-by-four loosely thrown into a catch on the outside His task would be to cut a hole in the side of the car near wher e he imagined the catch to be , and then reach out in order to trip the latch.

Encouraging himself in this fash ion , he began his tedious job eagerly. The pocket knife would be his key to a new life . Attacking the flat surface was a difficult project . His scraping , sidewise slashes soon bruised his unprotected knuckles until blood oozed forth in tiny rivulets to wet the siding. Fate was not unflinchingly cruel in giving him no light to work in , because he was spared seeing his knuckles torn to shreds and also in seeing the tiny indentation made by his labor. At least half an hour of his two hours was gone , but fatiguing muscles required him to cease Sitting down , Horton tor e long strips from his shirt. With the lengths of cloth he bandaged his knuckles. Again he mad e a minute study of the cell for some more feasible method of escape. There was none .

Back at his post Horton began to think as he worked. If he managed to liberat e himself , his

future would be different. Crookedness payed small dividends and demanded heavy recompense . Crime was no different from any " big business. " To profit from it one had to be on the " inside ," to be one of the favored few chosen as leaders ; such was the complexity and intricate organization of crime in all large American cities The Pacific Northwest and a normal life were his goals. Only an inch of hard lumber separated him from the opportunity to regain his self-respect and to start afresh. The steady scratching of his knife reminded him of a rat he had heard gnawing at a barrel of apples a few nights ago. There was a simile for you ! Horton couldn ' t help comparing himself with a rat

Maybe he had made some progress now; his strokes began to assume a different angle with th e siding . The time had seemed an eternity , but h e realiz ed almost an hour was still left before Denver would loom into vision . Horton again lapsed into his moody thoughts as his strokes increased their tempo. He recognized th e chief contributing factor in his moral failur e. It was that he was alone in the world ; h e had neither parents nor a sweetheart to interest him or guide him. Born in poverty and misery , he believed himself destined to inhabit those env irons the rest of his life. These somber thoughts calmed him , but his measured cuts did not slacken. Horton was working with three things in mind : first , an inherent dread of death ; second , a chance to begin again; third, liberation from the cell he was cooped up in. He did not

fear death more than another might have, but his mind was normal, and he felt strongly the tenacious spirit of human life Horton's was not a religious nature , and consequently it was not prayer or conscience that occupied his wandering thoughts. He strove to forget the future in an attempt not to think of the possible fate awaiting him.

Finally a tiny dot of light appeared in the center of his work; the job was going well. The blade snapped in two, but without a pause the remaining blade of the knife w .1s put into use. Although the hole was already large enough to permit a clear view of the country outside , there was little time to spare. The view which came to Horton ' s eye was a familiar one to any citizen of Denver ; the train was a scant fifteen minutes from the railroad yards But his work was taking form, a few more whittlings , and the hole would permit his hand to reach the cross-bar locking the door. Success was to be his Horton thrust his arm through the hole. It was a tight squeeze , but his elbow finally went through . Now it was only a matter of lifting the heavy cross-bar. A failure in the attempt, and then, success He was free. He had defeated the law after all, but there was no time to lose. Horton rolled the door partly open with one thrust and the next moment jumped free

Fate was not as kind to Horton as he imagined , or perhaps it was more so Horton jumped off a hundred foot trestle.

by HERBERT DEADEN

AC OMPAN Y of Royal Engin eers turned in at a little church yard . A way to the east heavy ordnance crashed. The captain : " Who ' ll spot that battery ." A young hardly known soldier picked up the binoculars . He seemed a gargoyle high on the church steeple. As the sun slid lower he became a perfect

sniper ' s target. Slate showered around him But only at nightfall did he come down . He saluted his captain. Nothing of fear or hate in his voice , just ' Tm sorry , sir ; the blighters got me." Blood gushed from his mouth , drenched the front of his captain ' s uniform He pitched forward onto his face . · 28 ·

by t.. MOTTE MARTIN

Impatient Youth , be still! Be still and wait. Now look anon through wisdom's jeweled eye, And breathless , watch the lovely butterfly Emerge from silken cell at Leisure ' s gait. No hand can speed. Be quiet! It is not late. Observe this budding bluebell and but try With hasty hands to ope the bloom thus nigh ; You would the Flower ruin as sure as Fate. And Love, more delicate in growth than theseThough when the blossoms blown it has its steel , Compels you wait until the Muses please To slow the flaming flower of Love reveal. But ah , on him , who quiet this blossom sees, The Gods bestow their greatest ecstacies.

Charred forms now stand where but a day ago Majestic trees stood in their proud array Of bright green leaves. Black arms toward Heaven outstretched