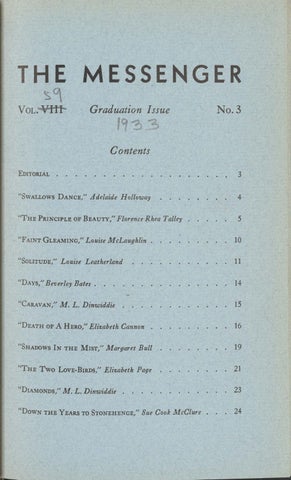

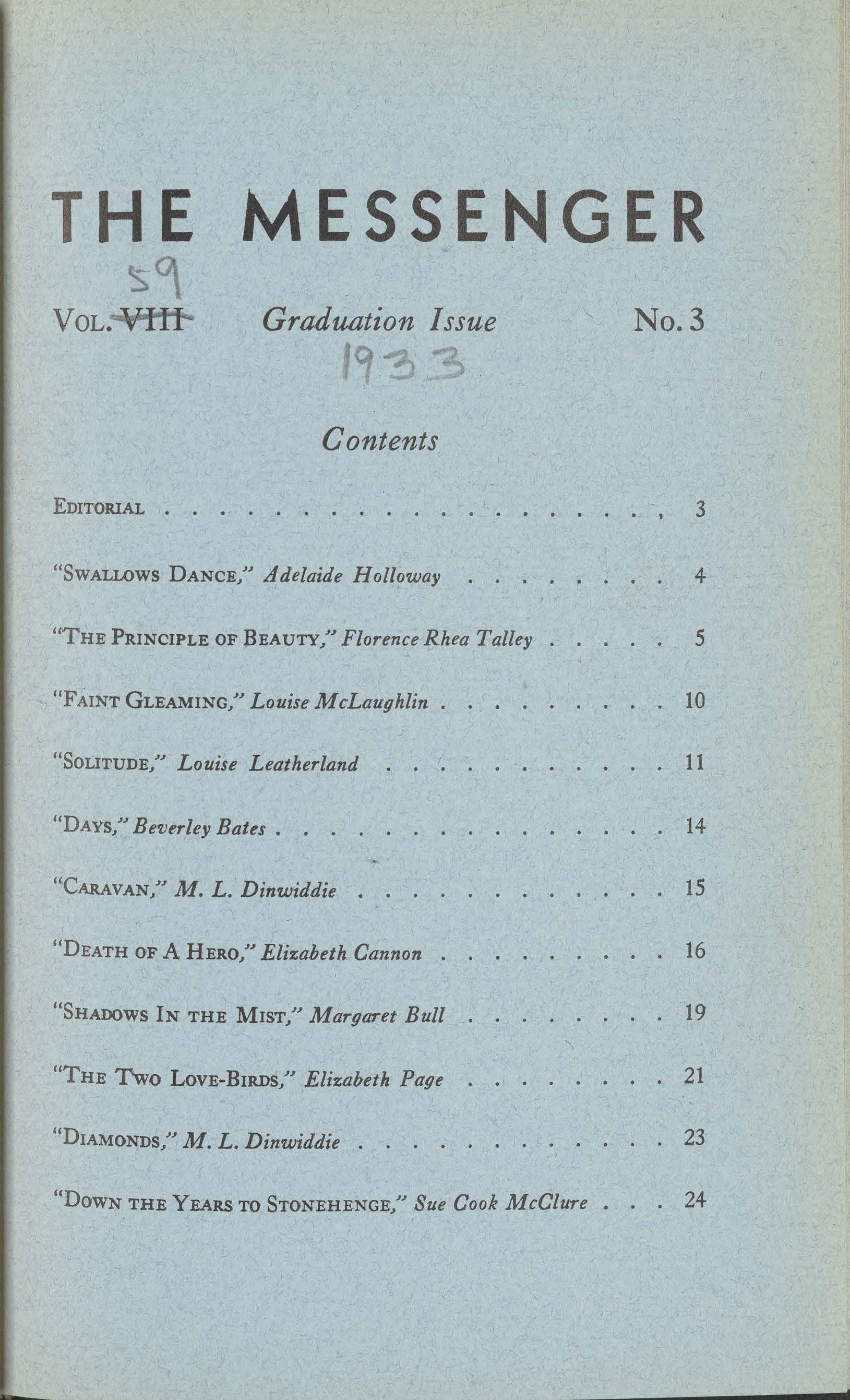

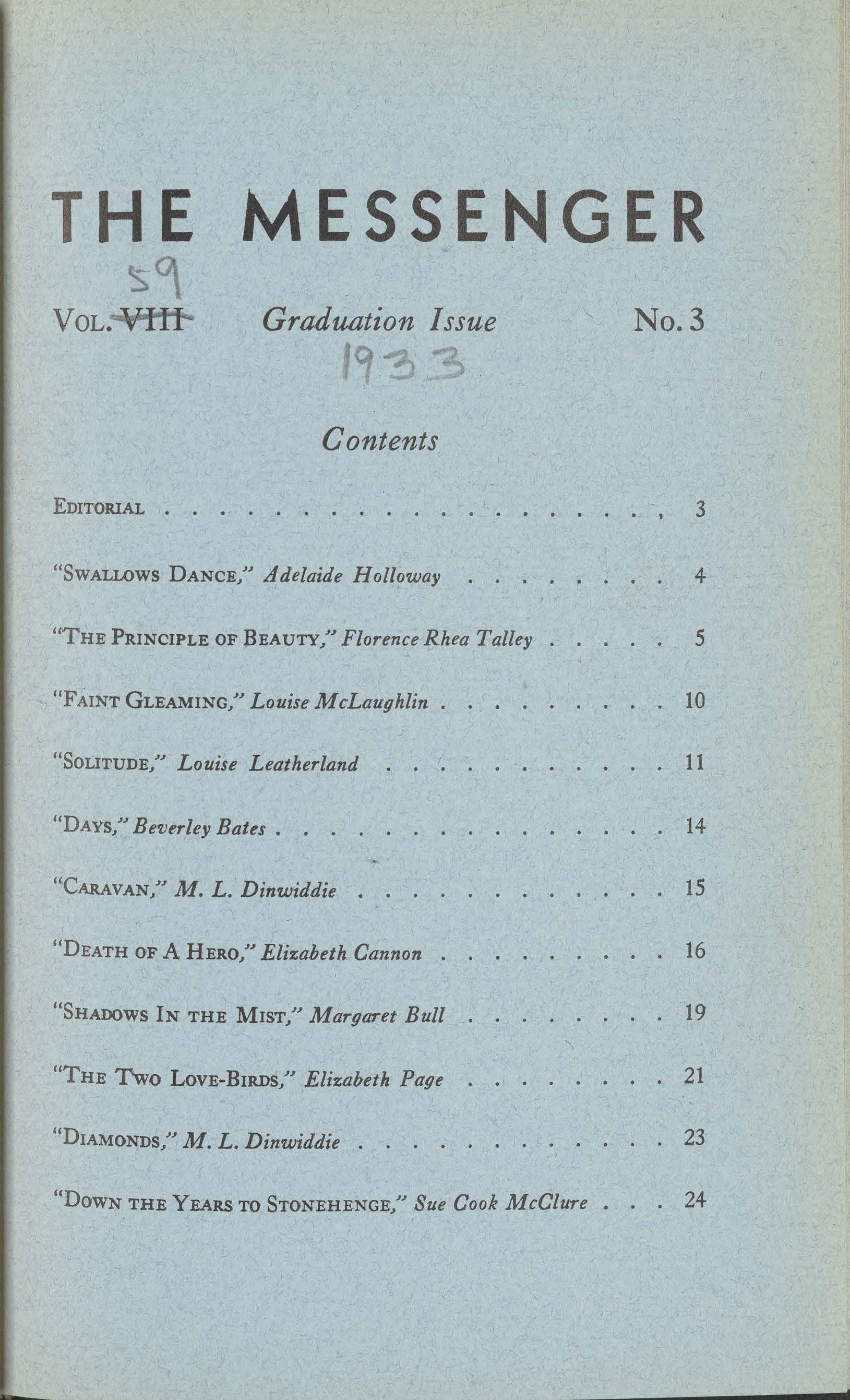

THE MESSENGER

LOUISE DINWIDDIE Editor-in-Chief

LOUISE McLAUGHLIN Associate Editor

LOUISE LEATHE&LAND

SUE COOK McCLURE Assistant Editors

MARION CLARK Busines Manager

E D T 0 R A L

Shakespeare once said, "the rarest of all things is a whole man"; this is no longer true. The rarest of all things is a whole MESSENGER-complete and volitional-the production of creative contributors I

The first design of creative writing is to amend the heart, to improve the understanding, to please the imagination, and, if properly governed, its tragic substance is conducive to the happiness of the reader. At Westhampton it is the tragic sl{,bstance of matter that has been conducive to the unhappiness of the editors. Creative writing has died and left its epitaph:

"Look ye, hereon is the site Of all and any who could write; From great ingenuity, Came empty vacuity, Creation was only a "might."

The staff has become reluctant literary agents waylaying, wheedling and cajoling for material. WRITERS I must we fight, wont you write? It is summer now, and there is leisure and imaginative escape. There are hours when common reality no longer satisfies and one looks for the intangible for satiation. Here is the nucleus of creative work. In the daily round of living the poet finds rhythm and sings; with his delicate power of words he reproduces a cadence of words. The prose writer's use of language and delineation is more kaleidoscopic, it is more solid and material matter. The dramatist visualizes the motions and action of life itself but-all observe, absorb and then produce. They become individual consciolls artists who have mastered themselves. So may you find your ability from the rudimentary instincts of human nature-express it. Do not subjugate yourself to things situated outside of yourself, but find a harmony from the fundamental instincts within. Living is one of the arts that mankind has never perfected but writing has been. So believe in yourself and analyse your thoughts, and write ... "they begin-let us be still." Do I hear-meditative eloquence? , -M. L. D. [ 3 J

Swallows Dance

ADELAIDE HOLLOWAY

Together swallows dance in the swirl of the storm, While ecstatic lightning rips the cold, gray clouds And over the chimney ' in instinctive swarm Wheel madly. Thus would I dance when longing crowds My soul, eager to break the petty ties That hold me by the strength that is not theirs; And while each new, neglected interest flies, Direct my thoughts to little, futile 1 cares. The flock sweeps by me in abandoned flight, Blown by the rushing wind in rhythmic curve. Thus impelled by pent up longings, might I in rebellion from my set course swerve.

But now, while flight worn wings reseek their nest, I strive to set my struggling soul at rest.

The Principle of Beauty

(A Study of Keats and Bridges)

FLORENCE RHEA TALLEY

,THE "principle of beauty in all things" was for Keats the center of that world which1 he created for himself out of his desires and imaginings. His letters, no less than his poems, reveal to us a life that was an eternal expression of the doctrine that "Beauty is truth, truth beauty." A century later we find another English poet dominated by the same impulse and giving it first place in his great picture of the universe, which he fittingly calls The Testament of Beauty.

But the strange relation between Keats and Robert Bridges is not that love of beauty is the foundation for both their philosophies. The mystery of the rnatter lies in the fact that the writings of both reflect the same ideas of Nature, of God, and of all the other elements that comprise philosophy and poetry. The world which Keats built from his dreams and desires was the same world in which lived and wrote also Robert Bridges.

All that Keats ever wrote revealed that he had a clear and consistent idea of the order of things and in this conception of which he gives us glimpses, is the picture that Robert Bridges consciously and purposely strives to depict. Bridges was not unaware of Keats' world. He is recognized as one of the best critics of the young Romantic poet, probably because he feels with Keats such a kinship. The similarity, however, is one of spirit only; their external lives were entirely dissimilar.

After an early life not far removed from the normal, Keats suddenly discovered, not only the charms of poetry, but his own gift, and in four years arose, from inexperience, to as lofty a lyric eminence as has been attained in English literature. While he was doing his greatest work, financial trouble, an unfortunate love affair, malicious criticism, and disease that brought knowledge of certain death combined to make his life one of turmoil and unhappiness.

Totally dissimilar from the disturbing conditions under which Keats composed his poems were the circumstances of Robert Bridges at the time of the writing of The Testa[ 5 ]

ment of Beauty. His poetry was revealed slowly with little assistance from those spontaneous and dynamic processes which are usually trusted to liberate the lyric impulse. When he wrote the Testament, he had received the greatest honor England can confer upon a poet, the position of Poet Laureate. From this secure height he could view the world with a philosophic calm quite impossible to struggling young Keats. · .

In view of these differences, it is strange that their outlook upon their fellows, whose treatment of them had so little in common, should show so many similarities. Yet it is indicative of some inherent likeness in temperament that both should have toward humanity the same fundamental attitude.

For, · though both recognized Beauty as the essential truth, to neither did its pursuit signify a selfish absorption in sensuous pleasure. Keats' Endymion, in his st:arch for the ideal Beauty, could not attain it until he had shared in the suffering of others. Apollo who in Hyperion strives for the same ideal that Keats sought, awaked from his swoon of selfish isolation and learned that they will never attain completeness who do not feel

" ... the miseries of the world are misery, and will not let them rest."

Bridges' agreement with this idea of devotion would be sufficiently manifested by his love of Christ and his faith in Christ's teachings, were it not for his reiterations that man's "reconcilement with suffering is eased by fellow-suffering."

To poets especially belongs the greatest care for humanity: their art will never die, but will remain " in midst of other woe than ours, a friend of man."

When we lo'ok further into the writings of Keats and Bridges, to find the reason for such love of fellow-man we see that there is a bond, not solely of affection, but of an innate likeness between the poet and his fellows. Nothing on earth [6]

"hath any other foundation that the common base of Nature's building."

Every mortd man, indeed, every atom, is part of the great order of things, good and evil, which is Nature. Keats, looking upon the world, "discerned in it a pattern, anq. divined that man must'also obey the pattern and be of ope . nature with the world which he inhabits." When he wrote, "Do you not see how necessary a World of Pain and trouble is to school an Intelligence and make it a soul?" he was accepting as beautiful all things pleasant and hateful. It was not with resignation, but with a full sense of its harmony that he perceived the eternal truth in all things, and the somewhat Stoic

" ... to bear all naked truths, And to envisage circumstance, all calm," was mellowed into the lovely song to Autumn:

· "Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they? Think not of them, thou hast thy music too."

And when Bridges tells man that "The wise will live by Faith, faith in the order of Nature, and that her order is good," he harmonizes all the pains that Keats suffered, and that he himself must surely have tasted, into a pattern of beauty. Yet there is one small portion of Nature on which men are wont to place too much reliance; thatt is, Reason. She is not so omnipotent as some believe, for "How should science find beauty?" Reason must look with deference and love upon the instincts and affections for, in Keats' words, "The Heart ... is the Mind's Bible, it is the Mind's experience, it is the teat from which the Mind or Intelligence sucks its identity." Bridges, in a different simile, ag~in ~ives R~ason her propeF place as secondary to the Imagination:

"The authority of Reason therefore rel~e~hat last hereon-that her discernment of sp1ntual things, the ideas of beauty,' is her conscience of instinct up grown in her to conscience of Beauty."

[ 7 J

In her analysis of things we can put no trust, for it has the imperfection of excluding everything that will not fit into the predestined scheme. "Things cannot to the will be settled, but they tease us out of thought," and the greatest saints and philosophers are those who have learned the truth that the thrush sang to Keats:

"0 fret not after knowledge-I have none, And yet the Evening listens."

Through what then, Reason being excluded, do we reach our goal? First of all, through our instincts.

"That dark mind with its potency is the stuff of life, nature's immutable provision."

To Keats, as to Bridges, the instincts are a treasure that Reason can convert into greater potentialities. As man grows in experience and intellect, his instincts become more spiritual, and the man Keats, who admired the energies displayed in a street-fight, becomes the poet of "Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter." For the ore of Instinct has been refined, by Reason's alchemy, into the gold of Imagination.

Keats' definition of Imagination carries on his simile of the "unheard melodies" : " ... have you never by being surprised with an old Melody ... felt over again your very speculations and surmises at the time it first operated on your soul? ... Even then you were mounted on the Wings of Imagination."

From the divine essence comes this Imagination, and through our communion with the spirits of life it leads us to truth. We "encounter Reality in the appearance of things," or, as Keats better says: "That the Imagination seizes as Beauty must be Truth .•. for I have the same idea of all our passions as of Love: they are all, in their sublime, creative of essential Beauty."

Man thus arrives at essential Beauty when that which is pleasing to the senses is changed into high spiritual loveliness. This is the allegory of Endymion, who, having glimpsed the moon, representing the essence of all beauty, finds her through sensuous charm, represented by the Indian maid, in the same manner that Bridges describes. [ 8 J

'' ... Nature ... teacheth man by beaut¥, and by the lure of sense leadeth him ever upward to heav'nly things, and the mere sensible forms which first arrest him, take on ever more and ~ore a spiritual aspect,-yet discard not nor disown their sensuous beauty." , until he has attained to

" ... the consummation of which is the absorption of Selfhood in the Being of God."

And when we read "the Being of God," we have come to the goal whither leads all Beauty, "that ladder of joy, whereon slowly climbing at heaven, man shall find peace with God."

For, though the Eternal Diety is for both, not an idea, but a living personality, he is also "the Universal Mind, whither all effect returneth whence it first began." To the question, "Wherein lies happiness?" both Bridges and Keats reply alike;

" ... that which becks our ready minds to fellowship divine, a fellowship with essence."

If such is the aim of these two souls, what of their poetry, which revealed the souls? In their philosophy, to every man whom Beauty has touched, and whose mind is in harmony with his instinctive feelings, Poetry comes naturally. That harmony of all things which has brought man into oneness with God produces also Poetry, and when Nature has raised our senses to a spiritual level,

"the ideas which through the senses have found harborage, being comes to .mortal conscience, work out of themselves their right coordinations, and, creatively, seeking expression, draw their natural imagery from the same sensuous forms whereby they found en trance."

Is this not God's way?

[9]

This is what Keats himself did, this is the purpose of Robert Bridges' Testament of Beauty, and the writings of both reveal to us the principle that "Beauty is truth, truth beauty-that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

Faint Gleaming

My past comes back with the<wind and the swallow, the shadow of the sky that is evening. The cricket is a memory of I know not what, a faint sweet stirring that is gone now

I reach out eager fingers but it is a shadow I cannot grasp0 let me hold it again!

Faint gleaming of a forgotten moment, clear as crystal beauty, gone now

LOUISE McLAUGHLIN

Solitude

LOUISE R. LEATHERLAND

Athousand years ago one who sang of the sorrow of life complaining of being "left to roaming weary wastes with winter in his heart" phrased it thus:

Often alone in the dark before dawning

All to myself my sorrow I tell.

My heart's deep secret, my hidden spring of woe. Friend have I none to whom I may open

My heart's deep secret, my hidden spring of woe.

With what a pain-torn heart he must have discovered that to even the longed for friend he could not lay open his deep secret, that such an one his spring of woe and joy alike would be hidden! Centuries before him a shepherd king had found infinite understanding in himself alone. The Infinite came to mean to him a high tower, a walled garden. There is a solitude of high and distant places which draws man aside from men. Not only David knew it on calm hills, but Jeanne D'Arc found it in quiet woods. Only when solitary, do old men dream and young men see visions. Not often from stifling crowds come individuals to discover to humanity the path of life. There is a certain perspective in distance. For the multitude waiting the light denied, impetus lies in the voice "crying in the wilderness."

And there is the solitude of loss, the loss of friends, of which the wandering Saxon heart complained bitterly. Yet friendship is but a passing in the night, with a Hail and Farewell. The growth and change of Time make one eternally alone. A young musician sings sadly:

But you have been and have gone again And I must shut again my garden door.

This tragic note resounds in drama and poetry, the loss of understanding and longed for companionship which fades in the eternal aloneness of the one within. Not only literature but philosophy and science picture

[ 11 J

the vast separation of the Mind. The school of thinkers who define the elemental substance in the term "space-time continuum" explains the attraction of bodies by the unifying force of matter. Is one led inevitably to the conclusion that the mind is a separating force? I wonder. In very truth, Thought seems the gift of Consciousness to the solitary. Granted the inspiration and value of group thought, the discussions of a Socrates were preserved by a Plato who went home alone to think of the day's thoughts as a whole . . Form is to another Greek philosopher, Aristotle, the absolute reality. Then Solitude seems indeed the stuff that life is made of. That part of life which is eternal lives only in thought. One may feel and act in a group, yea, decide with others; but that keen essence of Life comes only when one thinks, and alone. The form of Life is perceived by retrospection. Experiences become not mere events but Life itself when one thinks alone. The Future is only as clear as Thought can make it. Introspection, the thought of the one within, gives Life Proportion, Value, and Form. Carlyle's hatred of babbling, Wordsworth's deep silences, Maeterlinck's perception of the vacuity of most human relationship are indicative of the boundaries that exist between minds without conscious builders. The Divine Will hath set a certain reticence within Man's soul which is on guard against exposure. Each may try to break the bands encircling the Self, but there is a lock on his heart, a weight on his tongue. For every glorious companionship in a Transfiguration on the mountain heights, there is a deeper loneliness of a deserted comrade in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Complete communion of spirits is: as likely as complete loyalty. No matter how close a companionship is, Time soon makes the one path twain. Rupert Brooke vainly protests:

Is it the hour? We leave this resting place Made fair by one another for a while.

Now, for a god-speed, one last mad embrace; The long road then, unlit by your faint smile. Oh! the long road! and you so far away!

[ 12]

In this sense, all roads are solitary. The Flesh may unite two hearts, but the Spirit divides two souls. In flight of joy or sorrow, each exultingly turns to grasp the beloved's hand and finds himself alone.

And there is the solitude of choice, whether one's own or Fate's, that inevitable Wyrd of the Saxon is complaint. A few among the many shall be thrice lonely. One is consecrated to a deeper Understanding. To him is the common touch, the key of Sympathy. Significantly to him come the haunting strains of the Russian's cry "Only the Lonely Heart Can Know My Sadness." Another is set apart for Defeat, not sadly, but as for a higher calling. William Butler Yeats exalts him "bred to a harder thing than Triumph." Of such, another says:

More to be envied that they lost Than pi tied that they did not win.

Yet another is separated through Grief or Pain. He retreats to his fortress within, having no communication, or means of it, with the outer world:

That in his lone obscure distress Each walketh in a wilderness.

Of him a Spanish ·poet has written, celebrating the pangs of love, "only in your heart will you find shelter." Rupert Brooke says again of the grief-worn:

. . . . . such are but taking Their own poor dreams within their arms, and lying E -ach in his lonely night, each with a ghost. ,

In these lonely night watches, lonely souls have experienced with the psalmist:

I call to remembrance my song in the night: I commune with mine own heart: And my spirit made diligent search.

And as his soul grows in lonely sear~h, growth is rewarded with the final search. Then there 1s the reward of com-

[ 13 J

munion. Having been cruelly alone, gloriously lonely, the solitary one says:

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death. Out of solitude he goes to meet Death alone: Proud, then, clear-eyed and laughing, go to greet Death as a friend l

What can Death hold for him who has experienced the depths of Solitude?

Days

BEVERLEY

BATES

Days of quiet waves lapping on smooth shores; Far fields and green fields seen thru open doors; Wide winged birds drifting by the hill; Cooled sunlight thru dark leaves, and still Thin ' lines of clouds spiralled and hung; Pale down, snd lone note no man has sung; Days that drifti . and live and should never cease, If death should claim such peace-

Days of bent trees in the rain; Wild thoughts and dark thoughts beating in the brain; Cold rocks and bleak that know no green,,Eyes of creature$ dying caught unseen/ A glaring universe, stretched on every sideNo place, no place on earth to hide: Cruel looks and ugliness 'ti! only weeds are saneIf death could ease this pain! ( 14 J

Caravan

M. L. DINWIDDIE

Tonight our caravan is resting;

The sun in a mist of prism lights

Has found the night, and there are stars. Now in the deepness of the night

We are dreaming

Our hearts silently humming the songs they have always sung

Our eyes drink in this momentary beauty and look ahead. Tonight is only tonight.

Time yet has hidden pictures in the diary of daysTonight our caravan is resting.

[ 15]

Death of a Hero

ELIZABETH CANNON

HE could hear them coming along the corridor. Their footsteps re-echoed from the walls with a hollow sound. He stood back from the barred window. "What a miserable hole!" he thought contemptuously. Was this the way all glory ended? No matter how high you climbed nor how fast you traveled, did there always come a cold, grey morning when you must go out from four walls and faceinfinity?

Well, if that was how the universe was organized, he was glad that he could die in a certain splendor, die with his boots on, upright, instead of watching his life seep away among a smother of blankets and pillows. His way would be quicker, at least. One second he would be standing there, tall, defiant, then-crack I And he wouldn't be any more.

A soldier's death is a glorious death, whether accomplished on the field of battle or before a firing squad. That is, if one must die. But how had he come to be captured? Where had his plans gone wrong? He remembered leading his column of Libertadores into Pataxical and then blackness until he had awakened with a throbbing head here in a N acionalista cell. No, there was something else -he recalled having halted the column in the little town, telling them to fall out. They had all gone into one of the cantinas. Ah, now he remembered-too much vino blanco, and the N acionalistas had come while they were too drunk to defend themselves, and now here he was-a choice prize. His men had already been executed that morning in wholesale fashion but for him there was reserved the dignity of individual attention by the firing squad.

They must be very proud of themselves, those Nationalistas, to have captured him - El Intrepido - who Rumour whispered) had slain thirty men single-handed in battle the week before; who, but a month ago, had taken the capital with a few hundred soldiers, only to evacuate it the next day without even deigning to destroy the fortaleza, who had r~sen from being a renegade, United States army [ 16]

officer to the dignity of full command of the insurrectos in this tiny Central American mud-hole, where the sun shone feverishly half the year and the rain came down in a ceaseless torrent the other half.

The Libertadores would have made him a general but he refused, having a childish preference for the soudd of "El Capitan."

There was another reason, too: back in the States he had been a lieutenant of cavalry. There had been a little unpleasantness between the captain and him - something about a woman-and the captain had taken care to report trivial offenses to the commanding officer as "insubordination." Until one night there was shooting, and the lieutenant had to leave quickly.

So now it rather pleased his vanity to be called "Captain." He often wondered if he had survived the shootingthere hadn't been time to find out.

The firing squad was at the door, the soldiers in their ragged uniforms and unacccustomed shoes stiffly conscious of the honor attached to their duty.

The American smiled thinly and nodded a greeting to the N acionalista generalisimo, who in turn bowed and clicked his heels ceremoniously.

("Too many American movies," thought the prisoner irreverently.)

The little procession moved down the long corridor and out into the sunshine. The yard of the carcel had been scrubbed and decorated for the occasion. The prisoner stood against the low wall and looked curiously at the crowd: pompous officials, nervously giggling senoritas, awed chicos peering from behind their mothers' skirts. Apparently the elite of the town had turned out for the show. Very well-he would let them see how a hero should die.

The generalisimo had drawn an imposing document from his pocket and was beginning to read. Evidently this was the indictment-a summing up of El Intrepido's "high crimes and misdemeanors." He interrupted the reading to ask for a cigarette, lit it, and stared through the haze of smoke, above the heads of the crowd, at the blue sky.

[ 17]

He wished it weren't so incredibly: blue. He wanted to remember the look of the sky at home in Vermont when he was a young boy, lying on his back on a pile of sweet hay, watching the soft clouds marching with soldierly precision across a blue parade ground. He would be a soldier some day ... and wear a sword ... and go to war. But just now it was so pleasant to lie in the scented hay, lazily swinging brown legs over the edge of the stack.

The generalisimo stopped reading ....

There is another odor on the wind, sweeter than that of the new-mown hay. M-m-m~Mom's baking apple pies. The boy sits up and stretches, then slides down from the haystack.

The generalisimo raised his sword, his bright untarRished sword, saved for state occasions ....

. The boy walks slowly up the path toward the house. The long weeds brush gently against his bare legs.

The generalisimo shouted to the firing squad-"Attention !" . , ,..

His mother is . standing in the kitchen doorway, drying her hands on her white apron. Her face is flushed and shining from the heat of the oven.

"Apunten 1" ....

Funny; she had always liked him best of all the children. "Such a scamp!" she would say and give him a comradely pat on the shoulder. The soldier shivered. The house. is very near. The woman smiles and beckons·to him.

"Wait l" he cries.

"Tiren !"-and there is a flash of fire all around. "Mother---!"

[ 18]

Shadows In the Mist

MARGARET BULL

THERE is a narrow valley between the mountains of the moon where a fine, shadowy mist hovers. The shadows in th~ mist are curiously shaped and beautifully tinted with strange colors. Halfway down the slope of the valley there is a figure, a shadow, darker than the other shadows. It is the figure of a man. He swings a net to catch the shadows,a net woven of songs, gathered from the mountain slopes, and a dream, snatched from the horn of the moon.

If you have the shadow-seeing eye, you will be able to see shadows everywhere,-on a single word, on a familiar face, and in the far places of your mind. There are transient shadows which spring into being at unexpected moments; 1 recurring shadows which are an integral part of certain people; and the vast shadow which falls from the wings of life itself, as it flies across the world.

Momentary shadows come most frequently when you sit very still and fold your thoughts down quietly. A thought which has become ridged with running too constantly in a . persistent groove will slant suddenly, and cast a new shadow across the question in your mind. Or, a single word will slip out of a hidden: nook in your mind,-a casual word a friend used in speaking of you, as startling, now, as a mirror faced unexpectedly.

There are lovely, fleeting shadows in church: purple shadows when the organ begins to play; silver shadows where seven candles burn before a lifted cross; a jagged, crimson shadow when a tall, gaµnt man begins to speak.

But momentary shadows are so fragile that a sudden noise or a tone of a voicd can rip across them and destroy them utterly. The newly-risen sun is shining through the maples and is throwing strips of color across the lawn. There iS'a quiet expectancy in the air as if the world yv_ere freshly made on this particular morning and were wa1ttng

[ 19]

for something quite extraordinary to happen. You hold your breath. There is a dawn-colored shadow just before you. If you can grasp this shadow, you will know what the morning is waiting for. You slip out of bed and lean your elbows on the window sill. Then a voice breaks through the stillness, "What are you looking at? You'll catch a cold there in the window."-And something is lost from the air.

Shadows springing from the hidden core of a person have more permanence. These shadows form the central part of your memory of certain people. There was a luminous lady who visited your mother when you were a little girl. You would sit wide-eyed and wonder how a person could become so soft and shining. Then there was the woman next door whom your mother did not like. She said too much too loudly. Yet that day when you fell down and skinned your knee, and you wanted so much to cry, she picked you up, and, somehow, you found yourself laughing. When you looked at her, you saw a shadow, hard and bright like polished metal. Once there was a salesman in a bookstore. You would watch him fold the edges of the wrapping paper meticulously at the corners of the book you had just bought, and you would almost forget to listen to his quick comment on the book he was wrapping, as you watched a shadow just behind his eyes. You learn to remember these shadows from one time to the next, but you are never quite sure of what stuff these familiar shadows are made.

There is a shadow so large that you can never see the whole of it at one time. This is the shadow of life, itself. You get a glimpse of it here, and a glimpse of it there, an4 fit the parts together the best way you can. It is like fitting together the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle on the wrong side without knowing the picture of the whole. * * * * *

On across the valley between the mountains of the moon moves the figure of a man. He swings his net to catch a shadow. The shadow slips out of sight and the man follows it and disappears among the shadows 'in the mist.

[ 20]

The Two Love-Birds

ELIZABETH PAGE

IT was midn!ght. The street was deserted, and a thick fog choked the air. The moon was veiled in heavy, jealous clouds; the more timid stars were in hiding. Down the street swept a biting wind, rushing along as though the devil himself were in pursuit. Every window and door was closed tightly against the rawness of the night atmosphere; every house so dark and silent that it seemed impossible for any living thing to be contained within the brooding walls. The only light relieving the blackness was the hazy blur of a lonely street lamp, standing guard on the corner.

Out of the surrounding fog and into the circle of light stepped the figure of a man. The collar of his overcoat was turned up around his neck, and a soft hat was pulled down over his forehead, shading his face. He fumbled a moment in his pocket, there was sharp scratch, and he held a blazing match cupped in his hands. He brought it up to the cigarette in his mouth, revealing a strong, square-set jaw, above which was a pair of glinting dark eyes. When the cigarette was a glowing spot in the darkness, he threw the match into the gutter, where it sputtered and went out.

After peering around him, he began to stroll leisurely up and down the street. To any casual passer-by he would seem to be merely a loaf er enjoying a smoke before going home. If one looked more closely, however, one could see in his eyes a light of tense expectancy. Under a veil of nonchalance was an under current of determination and menace, evidenced by his stealthy, purposeful steps. As he passed beneath the street lamp, his hand tightened noticeably on something bulky in his pocket. He inhaled the smoke from his cigarette and blew it out decisively. He stood where he was, looking steadily down the street ahead of him.

A clock somewhere in the city struck the quarter hour, then the half. With each chime the dark figure of the man grew more watchful. Cigarette after cigarette was lit, puffed on, only to be thrown away when half-smoked.

[ 21 ]

Never for a second did his searching eyes leave off scrutinizing the end of the next block, indicated by a light shining dimly through the ' fog.

Suddenly he started, and moved quickly into the shadow of the nearest house. The sound of footsteps could be heard -faint at first, then gradually growing louder. The man stood in the darkness, watching and listening. He seemed satisfied. His jaw set in a harder, more determined line, his right hand clenched the heavy object bulging at his side. But his eyes took on a surprised look as it became evident that two people were approaching. He was puzzled; and leaned forward anxiously, trying to pierce through the fog. Two figures emerged into view slowly, one a man, the other a woman, who clung to her companion's arm. The waiting man appeared undecided for a moment; then determinatiorn was written again on his face. He gripped the thing in his pocket, and poised himself on the balls of his feet. Then at the sound of a high-pitched giggle, he jumped. He stared again at the figures who were nearing the light in front of him. With its aid he saw their faces; his suspicion was apparently confirmed. His expression changed. .N half-smile relieved the grimness of his thin lips, and with this grin twisting his mouth, he stepped out of the shadows into the path of the couple. They stopped short. Fear paralyzed them as they recognized the man before them. They watched his face, terrified by that inscrutable smile. Their eyes went instinctively to the hand hidden in the protruding pocket, and stared at it, fascinated. Slowly it was withdrawn, bearing a cigarette to the mouth of its owner. "Got a light, buddy?" ?esaid.

The other man was too stunned to answer, but his hand automatically produced a box of matches. With trembling hands he struck one, and held it up to the cigarette between the still-smiling Ii ps.

"Thanks-You two are pretty scared, aren't you?" He gave a short laugh. "I don't blame you. I sure didn't expect to see you here, Molly, any more than you did me. I guess that makes it mutual."

"Molly" assumed an air of bravado and said nothing.

[ 22]

The man turned to her companion:

"Sure, I was waitin' for you-and you know damn' well why. That was a pretty dirty trick you pulled on me the other night, and I meant to get you for it. Now I see you've sorta stolen my gal." He made a gesture towards Molly. "What am I going to do about it?. Well, you can rest your mind on this point. I'm not going to send you where you belong-you'll get plenty of hell here with her eternal giggling and baby talk-It's no use, beautiful, you're both gonna hear me out. This isn't any pop-gun in my pocket. I came prepared to do business.

"Well, Buddy, I guess I'll call the score even. After thinking it over, you don't seem good enough for me to waste a bullet on. It wouldn't do my rep any good to have people say I went around bumping off sneaking dogs ... Now I'll just make myself scarce, and leave you two lovebirds to coo in privacy. So long-and God bless you both, my children!"

And with a low, mocking bow, he strolled away. The two ruffled love-birds watched him until he had disappeared into the fog, then turned to look at each other in amazement.

"He's nuts " said the male bird when he had recovered ' his voice.

"I'll say so," piped his mate. [ 23 J

Diamonds

M. L. DINWIDDIE

Diamonds are hard and coldprecious stones. Man paid the toll in sunlight, and toiled in the pits of earth's belly 'drank its black bitter bile, to give an iridescent spark to a woman's smile.

Dowri the Years to Stonehenge

S u E C o ·o K M c C L u R E

Through dark forests, By pale moonlight, Flit frail ghosts Of long dead priests. Past tall trees, Black by might, Druid shades steal With uplifted knife To blood-stained altars Gray in pale moonlight. Druid shades walk; Gray priests stalk Down the dark aisles Of the dark past. All is shadowy, night; Time is past-centuries flee Backwards through the trees, Down the years to Stonehenge.0

UB~ARY ~SITY-OF IC VIRGINIA

LIBRARY

UNJ V ERSITY OF RICHMQNFJ - V IRG I NIA