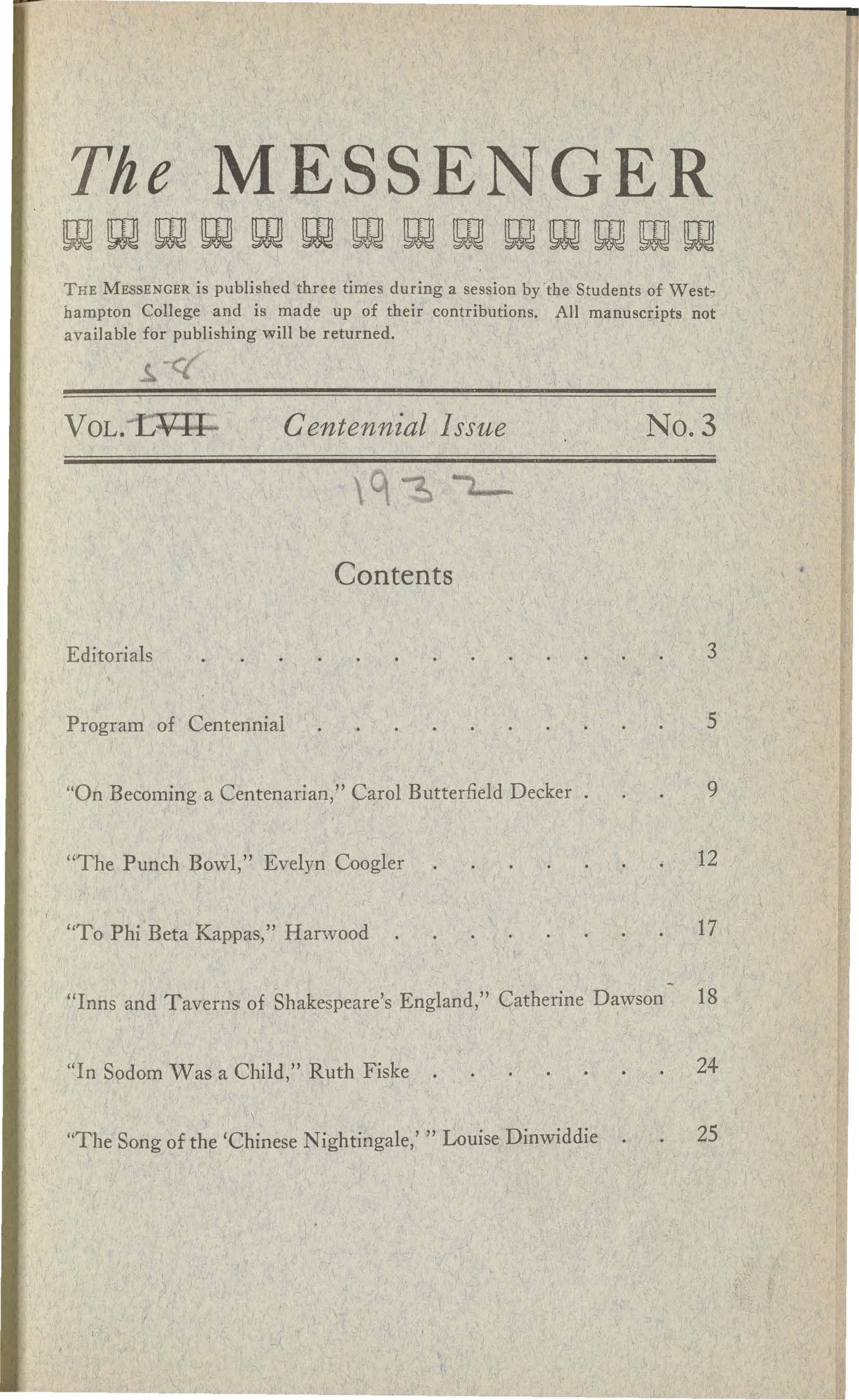

The MESSENGER

The MESSENGER ., ., .,

VALERIE LEMASURIER Editor-in-Chief

EVELYN DUNCAN Assistant Editor

FRANCES RAWLINGS Assistant Editor

MARION CLARK Business Manager

EDITORIALS

"Multitude Jn Unity"

AND when it happened that the venerable mother school was to celebrate her one hundredth birthday, Westhampton, one of her youngest daughters sought and found the perfect gift. '

Out of the magic of Spenser's Faerie Queene a Westhampton student wrought a fair pageant, turning it deftly with creative fancy. It was a fairy tale on paper. It took no end of very modern magic to make it come true, as a tribute on that birthday. Over two hundred people worked endlessly. Students, especially the Senior Class, the faculty, and a few others, intimately connected with the college, turned their minds towards its making. They integrated their personalities and talents into it.

Then one May night it came alive in a setting of natural loveliness and classic lineation. Great processions of colorful knights and ladies moved, singing as they went. Fairies and other woodland creatures danced in vari-colored lights. A knight of the Red Cross fought ingeniously contrived dragons, in order that he might win fair Una and bring her back to the court of the Fairie Queene, where she would be crowned queen of May.

It was a satisfying spectacle-at once poetry, color, movement, light, and music, which is all of these. The great English poet himself could not, one felt, have scorned it. The pageant was a manifestation of the ageless inspiration of his imagery. At the same time it was a significant example of the power of modern stage craft. . It would be hard to equal the ,effect secured by the expert designing and fabrica6on of the costumes and cleverly simple sets. There was a new height of interpretation reached in the eurythmics, the grouping of characters, and use of pantomime. Too much could not be said for [ 3 ]

the grace and feeling of music selected with the knowledge of real connoisseurs.

Indeed, it seemed that such a festival could come only once in a hundred years. It was with pride that W ~stliampton presented her gift, which appeared the perfect sum of the old Roman definition of beauty, "multitude . . " V L rn umty...

Reflection

0NE is supposed at this point to pause and look back with reflective melancholy at one's college days. If one is an editor, one should wish that one had more nearly fulfilled one's high hopes. One should, with slightly patronizing wisdom admcmish one's successor, and express the conventional optimistic prophecy that next year our campus will blossom like a fertile meadow witbi the exquisite, exotic effusions of embryo genius.

Yet some reflected spark of compassion warms this heart of tough, resilient india rubber. One regrets that once again three untried and aspiring female editors must undertake alone the task of supplying campus literature. Many, many times, dear future editors, you will sigh for a stalwart masculine partner on whom to place the blame for a poor issue. Often, you will wish for a valiant masculine pen to express those thoughts which are for you inexpressible. Again and again you will sigh for boyish poetry and puerile prose to piece out the sparse maidenly offerings. _ 1

Their grandfathers founded THE MESSENGERin days when female education was considered indelicate. Oh, decadence, decadence, this modern Richmond College is content to leave writing to girls. An enigma, a mystery, a sad fact to leave behind.

Farewell, may your searching be profitable and your labors rewarded.-E. D. [4]

Centennial Celebration of the Founding of the University of Richmond

Nlay 8, 9, and 10, 1932

Sunday, May the Eighth 4:00 P. M.

Academic Procession forms at Robert Ryland Hall

4 :30 P. M.

PROCESSIONAL.

CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION

Henry M. Cannon Memorial Chapel

lNVOCATIO-Dr. David M. Ramsay. President F. W. Boatwright, LL.D., presiding.

Now LET EVERYTONGUE Ano RE THEE . . . . Bach ( 1685-1750)

AVE MARIE Arcad!:lb (1514-1575)

WITH HEART UPLIFTED . . . . . . . Schvedov (1889..........)

University of North Carolina Choir.

PRAYER-Dr. G. B. Rudd. HYMN-"O God, Our Help In Ages Past."

CENTENNIALSERMON-The Rev. Sparks W. Melton, D.D. President Virginia Baptist General Association. THE WELL-BELOVED-Violin by Earl Wohlslagel. University of North Carolina Clzoz'r,. BENEDICTION.

Monday, May the Ninth 9:00 A. M.

REGISTRATION OF ALUMNI, ALUMNAE AND DELEGATES Faculty Room, Robert Ryland Hall, Richmond College.

10 :00 A. M. ROUND TABLES

THEME-"One Hundred Years of Higher Education in America."

All papers and addresses are by Alumni of tlze University of Richmond. I. THE HUMANITIES-Main Lecture Room, Chemistry Building.

W. A. HARRIS,M.A., Ph.D., Professor of Greek, presiding.

]AY B. HUBBELL, Ph.D., Professor of English, Duke University -"American Literature a Hundred Years Ago."

W. H. FAULKNER, Ph.D., Professor of Germanic Languages, University of Virginia-"An Attempt at Evaluation of Modern Language Classics."

]. ]OSEPHINE TUCKER, M.A., Professor of English, Foxcroft School-"College Entrance Requirements."

E. M. GwATHMEY, Ph.D., Professor of English, College of William and Mary-"America's Debt to Her Novelists In the Past Century."

[ 5 J

II. MATHEMATICSAND THE NATURAL SCIENCES - Main Lecture Room, Richmond Hall

R. E. GAINES,M.A., Litt.D., Professor of Mathematics, pr.esiding.

R. E. LOVING,Ph.D., Professor of Physics, University of Richmond-"Mathematics in Scientific Progress."

F. MORRIS SAYRE,B.A., B.S , M.E., Managing Director Com Products Refining Co., New York City-"Liberal Education for Industrial Leaders."

A. W. FREEMAN,B.S., M.D., Professor of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University- "Applications of Biology to Public Health."

E. E. Rmn, M.A., Ph.D., Professor of Organic Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University-"A Century of Progress in Organic Chemistry."

III. THE SocIAL ScrnNcEs-Charles H. Ryland Memorial Library.

S. C. MITCHELL, Ph.D., LL.D., Professor of History, presiding.

E. JEFFRIES HEINRICH, M.A., Associate Professor of History, University of Virginia Extension Division-"Ten Years of Political Education of Women."

THEODOREM. WHITFIELD, Ph.D., Professor of History, Western Maryland College-"The Attempts of the United States to Enter the Courts of International Justice."

JACOB BILLIKOPF, LL.D., Director United Jewish Charities, Philadelphia-"Unemployment in America."

jAs. H. FRANKLIN, D.D., Secretary Northern Baptist Foreign Mission Board--"Some Problems ofthe Far East."

IV. THE LAW-Reading Room, Chas. H. Ryland Memorial Library.

M. RAY DouBLES, B.S., LL.B., J.D., Dean T. C. Williams School of Law, presiding.

J. VAUGHANGARY,B.A., LL.B., Attorney-at-Law, Member Virginia House of Delegates-"Educational Standards for Admission to the Bar."

ELIZABETH N. ToMPK1NS, M.A., LL.B., Attorney-at-Law"Women in the Law."

E.W. HUDGINS,B.A., LL.B., Judge Supreme Court of Virginia -"Courts of Virginia, Past and Present."

1 :00 P. M.

LUNCHEON FOR SPEAKJERS, DELEGATES AND INVITED GUESTS

Roger Millhiser Memorial Gymnasium.

B. WEST TABB, B.A., Vice-President and Treasurer, presiding. INVOCATION-The Reverend Giles B. Palmer. GREETINGS

From the City of Richmond. Col. Hill Montague.

[6]

From the Business Interests of Richmond.

W. H. Schwarzschild, President Richmond Chamber of Commerce.

From the Religious Organizations of Richmond

The Reverend William Hedley, D.D., President Interdenominational Ministerial Union of Richmond.

PRESENTATIONby John Stewart Bryan, LL.D., of Trustees' testimonial to Dr. R. E. Gaines, in recognition of his forty-two years of service as Professor of Mathematics in the University of Richmond. PRESENTATIONOF PORTRAITS.

3:00 P. M.

VIRGINIA INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETIC CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIP BASEBALL GAME

Randolph-Macon College vs. University of Richmond, University Stadium.

4 :00 P. M. ATHLETIC MEET Westhampton College.

6:00 P. M.

MEETING OF EPSILON CHAPTER PHI BETA KAPPA

Initiation of Alumni members.

Charles H. Ryland Memorial Library.

7:00 P. M.

CENTENNIAL MEETING OF UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND ALUMNI AND ALUMNAE SOCIETIES

Including Alumnae Society of the Woman's College -of Richmond and of the Richmond Female Institute.

CENTENNIAL DINNER OF ALUMNI AND .A:LUMNAE.

Presidents-Dr. Richard W. Vaughan, Miss Martha Lipscomb, Mrs. Frank D. Epps. ' Roger Millhiser Memorial Gymnasium. ~LUMNI ADDRESSES

"The Colleges of Yesterday-the University of Tomorrow."

FRANCIS P. GAINES, Ph.D., LL.D., President Washington ari.u Lee U niver.sity.

How ARDLEE McBAIN, Ph.D., LL.D., Graduate Dean Columbia University.

Miss Susrn BLAIR, M.A., Professor of Dramatic Art, Hollins College.

MRS. MARIA CHILDRESSSEARS,B.A., Washington, D. C.

PRESENTATIONTO THE UNIVERSITYBY THE RrcHMOND CHAPTER OF ALUMNI OF PORTRAITOF PRESIDENTBOATWRIGHT-Thomas Branch McAdams, M.A., LL.D.

ACCEPTANCEON BEHALF OF UNIVERSITYOF RICHMOND--Ernest M.

7 J Long, LL.B., Chairman Executive Committee Board of Trustees.

Tuesday, May the Tenth 10 :00 A. M. ACADEMIC PROCESSION

Robert Ryland Hall.

10 :15 A. M. CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION

Henry M. Cannon Memorial Chapel.

PROCESSIONAL-"God of Our Fathers."

THOMAS BRANCHMcADAMS, LL.D., Chairman Centennial Committee, presiding.

INVOCATION-The Reverend J. Emerson Hicks, D.D., Baltimore. ADDRESSOF WELCOME BY PRESIDINGOFFICER.

CENTENNIAL ADDRESS-F. W. Boatwright, LL.D., President University of Richmond.

ANTHEM-"Glorious is Thy Name."~Mozar,t

CENTENNIAL A DDRESS-] as. R. Angell, Ph.D., LL.D., President Yale University.

CONFERRINGOF HONORARYDEGREES.

DOCTOROF DIVINITY

, The Reverend Edward Hughes Pruden, B.A., Ph.D.

The Re ve rend Beverley D. Tucker, Jr., M.A., (Oxon.) D.D.

DOCTOROF LAws

Homer L. Ferguson.

Howard Lee McBain, Ph D.

Archer W. Patterson, B.A., LL.B.

, 1 :00 P. M.

UNIVERSITY LUNCHEON TO DELEGATES AND INVITED GUESTS

Roger Millhjser Memorial Gymnasium.

T. Justin Moore, presiding.

INVOCATION-The Reverend George Braxton Taylor, D.D. GREETINGSFROMCOLLEGESAND UNIVERSITIES,AND FROMTHE COMMONWEALTHOF VIRGINIA.

R. Norman Daniel, M.A., Dean of Furman University, Greenville, S. C.

President Meta Glass, Ph.D., Sweet Briar College.

Graduate Dean John Calvin Metcalf, LL.D., University of Virgmia.

4:30 P.

M. MUSIC RECITAL

MRS. EDITH HATCHER HARCUM, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Cannon Memorial Chapel.

In Honor of the Reverend William E. Hatcher, D.D., LL.D., sometime President Board of Trustees University of Richmond.

DEAN MAY L. KELLER, Ph.D., presiding.

7 :00 P. M. THE PAGEANT OF "THE FAIRY QUEEN"

Presented by the Students of Westhampton College. Luther H. Jenkins Greek Theater.

8 ]

On Becoming a Centenarian

By CAROL BUTTERFIELD DECKER

"Time ripens all things; no man is born wise."-CERVANTES.

"The time has come," the President said, "To talk of many things, Of past and present centuries, And whether time has wings."

THEgeneral consensus of opinion is that it has. Even though none of us, in 1932, can remember the founding of Richmond Seminary in 1832, and none of us will be celebrating the bicentennial in, 2032; nevertheless, when we consider the developments since 1832, it seems amazing that so much could have happened in a mere century. If the fourteen youths who enrolled in the Seminary one hundred years ago could have been granted a vision of themselves, increased a hundred to one in one hundred years, it would have gratified more than their sense of mathematical fitness. If they could have beheld our present campus, in the full glory of spring, fairly burgeoning with celebrities who came to do honor to that little nucleus of a century ago, how amazed they would have been at what has been accomplished.

It is interesting to speculate on what we should see at the bicentennial in 2032. I wonder if we should see 140,000 students. And a new central library! And all the colleges united on one campus! But most of all, I wonder if we might see a Woman's Building!

How proud the boys of 1832 would have been of the host of loyal sons and daughters who returned to rejoice with their alma mater on her one hundredth birthday. From as far back as 1869 they came, and from as far away as China. Many came bearing gifts for the mater, and all bore their congratulations for her achievements. I wish those men whose vision made our University of today possible, might have been present in the flesh, as they were in the spirit, to share the three-day feast of words [ 9 ] -

and fellowship, not to mention the real banquets we enjoyed. But as long as such names as Ryland, Harris, and Gaines remain with us, their immortality is assured.

Certainly it takes time to ripen all things, and no man is born wise, as Cervantes discovered some years ago. ' After a hundred years of ripening, during which time it is to be hoped we have learned many valuable lessons, we should have attained a certain maturity of vision. We should be able to look back over the past century with frankness and sincerity, and take stock of our experiences, admitting our mistakes, and noting our successes, that they might both stand as guide-posts for our future. Unless we can profit by the reviewing of the past, and build upon it an improved future, then this Centennial Celebration has been a vain orgy of sentiment, and not the important foundation stone for the future which it should be. It is pleasant, indeed, to glory in the past, and inspiring and important to dream of future greatness: But both of these luxuries are as sounding brass and tinkling cymbals if we forget the wedge which separates the past from the future-the now. Unless we continually strive to make the present as perfect as possible, in the future we shall have little cause to glory in our past.

Under such wise leadership as Dr. Boatwright's has proven for nearly four decades, this is not likely to be forgotten. But no one man could carry on the program of an institution which has attained its present proportions without able and conscientious co-operation. This, the President has surely enjoyed from his entire staff.

The splendid work of the treasurer, B. West Tabb, should be particularly commended. It is largely through his unfailing efforts and efficient service that we are able to make the proud statement that the University is without debt. To him is due much praise for his ingenious handling of a difficult situation during this trying period of financial depression. Dr. Harris, who, in the Greek department, is carrying on the traditions of his famous family, cannot be too highly commended for his years of service to the University. Special mention is made of these two, because in the general bestowing of laurels [ 10 J

they seemed too busy adorning others to receive their own full share.

Of course, Westhampton College could only bask in reflected glory at the celebration of a Centennial; but as one unit of the University she naturally came in for a certain amount of attention. Whatever of praise falls to Westhampton College is directly due to the tireless energy and the brilliant direction of Dean May L. Keller, who has been our guiding spirit from the beginning. Too much cannot be said of the high standards which she has insistently maintained for the college, often -in the face of great difficulties. She, like the President, has been supported by a loyal and efficient staff of co-workers. We cannot enumerate all the names of those who have contributed to make the Centennial celebration the glorious success it proved to be. Suffice it to say, with Sir Walter Raleigh, that our "history has triumphed over time, which besides it nothing but eternity hath triumphed over."

11 J

THE MESSENGER

The Punch Bowl

BY EVELYN CooGLER

. FORlong, long months had silence lain like a great sleep over the forest of Annuttalagga. Unquestioned, undisturbed, it hid in its vastness unclaimed thoughts and the mysteries of unfathomable time. Now, in the inevitable spring, its startled ponderousness trembled at the sound of children's voices. Their laughter cut the quiet like so many sunbeams in the dark. With the rush of falling waters, they tumbled down the woodland pathways awaking the creatures to the stir of spring. Timid thoughts that for long had wandered in the silence unmolested, now heard the shouts and flew away in terror, escaped, leaving that blankness of invaded places that is, by mortals, consistently unperceived. It is that blankness left by thoughts at their sudden evacuation; the stillness unstirred by the tiny currents from their wings in passing; the deadness left where their constant flutterings kept the air pulsing and alive. But today that stillness of the forest was not quite stillness because of one little idea curious even in fear. It had paused in its flight and caught now, all unawares, in the mind of the youth, Pelynn.

There are minds and minds, and there are thoughts and thoughts. This particular thought had a tantalizing personality. It wriggled about until Pelynn stopped shouting and stood still, Then it settled down to business and started him to musing. It played hide-and-seek till just as he was about to see it, it slipped back and he thought other things. Trudging along through the leaves, he tried to hear it speak, but it dodged behind the sound his feet made, a sound like the swish of water past a boat prow. If he jerked along it was like the slap against the dockposts. He liked it.

[ 12 ]

Then suddenly the thought wriggled again. Yes, it prompted, they were going to the Punch Bowl. It was a queer Punch Bowl, prettier than the regular kind. It sank down very deep into the ground and wasn't glass at all, but just moss and fern and a nice green glade at the bottom. There must have been giants who drank from it ' once a long time ago when it was filled with wine. He wondered how they dipped it out.

He was glad, when they arrived there, to be alone. Down the mossy side the young folk ran, and their voices echoed faintly back from the glade. Somewhere far across on the other side the hostess was spreading the lunch. He leaned against a great tree and looked away, way down at his friends. How tiny they seemed l He wished they would come up; something might happen to them there. He called to them, but they did not hear. Then they motioned him to come down, but the thought would not let him go. It seemed that the Bowl was full of a thing he could not see; perhaps it was some secret sort of wine.

If only that thought would be still! Either be still or ... there! there! He'd caught it ... he knew what the thought said ... What was in the Punch Bowl? Who could tell him what was in the Punch Bowl? In his excitement, half incredulous, half hopeful, he looked about. If the trees were not so silent he would ask them. Perhaps it made their leaves so pretty. But he was afraid to ask. He was afraid, yet he had to know. Oh, who could tell him? The children? They were playing a dancing game and they skipped about in a circle. They looked almost like fairies, and he wished they were. It would do for fairies to dance there; they would know all about the secret and he wondered if they'd tell. Suppose he came ' . on a moonlight night-all alone-and was very qmet(he stood poised a breathless moment at the very thought) -mightn't he see them, and mightn't he learn? How the thought wriggled and skipped in ecstacy as he mad~ ~he decision. The fairies-he would come and see the fa1nes. Joyously he ran down the path to join the dancers; and madly he danced, gayer then than any of the rest.

[ 13 ]

Soft grayness hung upon the world of fields and gardens and hid familiar pictures in an unknown loveliness. Down the rose path soft, misty cobwebs floated between silver leaves and opal buds. And out across the meadows opaque dewdrops created a nebulous sweep of frosted grass. But in the forest the grey deepened into blackness with patches of silver light filtering through the trees. The silence pressed in upon the ear drums; it throbbed against the locked doors of an inner mind; and tiny fancies went voyaging in light canoes, dipping paddles down into the darkness.

Waiting there, the youth stood still and hardly dared to breathe. Never, never had he known anything so still. It wasn't like any place he knew of, except perhaps the North Pole. But it was white there, and here it was a deep, deep black. Perhaps the moon had gone; he looked up to see, but it was still there-such an exquisite moon, all glisteny and cold like ice, thin ~nd curved and liquid as if it was going to melt and run off down the sky. The stars, like tiny drops, were sprinkled all around it: he wondered if the stars dripped off the moon.

Starting now, he hurried through the darkness, his heart thumping at the noise he made. It seemed to echo back from the very depths of the forest and almost to rustle the leaves of the sleeping trees. Everything was so far away and big; he wanted to touch somethingsomething close. He found the same big tree against which he'd leaned that morning, threw his arms about its trunk and stood still waiting. How large the Punch Bowl seemed I Maybe the fairies would get lost in it; perhaps they were - lost in the forest and would not come at allperhaps-but that was foolish. Fairies never got lost, and they helped people who did-that is, good fairies. He wondered, too, if they would have gossamer wings. What was gossamer anyhow? And where did they get them? Maybe he could get some. But after all that wasn't what he wanted most. He wanted to know what was in the Punch Bowl, and how to ask it. Anything you wanted so much to know you had to be so careful in finding out. It seemed rather hard. But the fairies were good; if only [ 14]

they would answer him-this silenceOh ! He stood very still and did not breathe. Somewhere a long way off the faintest sound of music and the sweetest he had ever heard. It seemed to float out of the darkness like Ii ttle liquid ripples spreading coolness. Closer and closer it came till now it sounded like the tinkling of tiny bells follo~ing each other in a line that wound and rewound through the forest. Watching with all his eyes the spot where the music came closest at last he saw the twinkling of many tiny lights like fireflies and shadowy figures flitting through the ferns. Over the 'edge of the Punch Bowl they came, a long train moving down its side with the soft murmuring of a distant waterfall. Down, down they wound into the green glade, each tinkling his tiny bell, and all the bells blending in an exquisite treble music-tones that made him think of ice in a glass and the splashing of a fountain.

Above the Punch Bowl the trees did not meet, but left a big, round hole like a dome, so that the moon poured silver down into the glade, showing the tiny fairy figures. And they did have gossamer wings! Now he knew what gossamer was-the loveliest stuff he could imagine. It was like dewdrops in a spider web, but prettier; it was like tiny rainbows caught in lace and it glistened almost like the moon. Now it flitted and danced about their figures like little whims. As softly and swiftly as whims themselves the fairies moved, treading as if on dreams, and holding hands they began to dance.

The youth, kneeling on the soft moss at the bowl's edge, was lost to all the darkness and strangeness of the night, lost to everything but the beauty there before him, forgetting he existed but in eyes and soul. If he had thought it would have been with the transcendence of a mystic; if he had expressed, it would have been with a spark of the divine. It did not matter that he seemed too young,nor that he was too old. No mundane moment or year of moments could disturb the song of eternity, nor mar the reality seen through an eternal dream. He watched them move around in a circle, and as they danced the circle grew larger and larger. It spread and [ 15 ]

spread till in the center something new appeared. It was as though a spring bubbled up to make a tiny pool, and the pool grew slowly, spreading out its edges. It caught all the brightness of the moonbeams and all the sweetness of the tinkle bells. It reflected myriad colors from its surface, yet imbibed them into its very depths. It was clear and deep, a magic liquid!

Around it the fairies danced, just at the pool's rim, moving ever back and up as it mounted in the bowl. Now and again he saw them bow and sip, and as they drank they became even more beautiful and their laughter was sweeter than the piercing sweetness of the pipes of Pan. Closer and closer up the slope they moved until he felt the fanning of tiny wings and heard the trill of joyous voices. Up and up the liquid mounted to the very brim of the bowl-he could have touched it-he could have caught them-but dancing, as lightly as they had come, the fairies wound away into the forest. The velvet of the darkness closed in behind their tiny lights and the echo of the last silver bell made a gentle ripple on the surface of the pool. He had not dared to break the spell, he had not asked; but now he did not need to ask. They had sung a song and he had heard: the Punch Bowl was full, full of a wine which Time can never spoil- a wine with countless names, and so forever nameless; an essense with a thousand flavors, yet eternally unchanged. Blessing the night, he looked up into the heavens where Ursa Major turned about Polaris in the sky. There, there was the dipper the giants had ussd to try this wine; and in the joy of their discovery they had flung it, full, up to the clouds one night. It must have caught there in the crystal north, spilling stars and planets down the sky. They had given, and they had given greatly. He could not reach that dipper, but he would find another. The fairies had siP,ped and they were beautiful; he would sip, but he would also dip and give. He would shape a tiny poem like a dipper and fill it with sparkling liquid from the Bowl. Then all the world could sip and be the richer. Freely, freely he would give, and every night the fairies would refill it; every night they would dance and grow more beauti[ 16 J

ful; and every night the wine would mount in its bowl, richer, and clearer, and more magic.

"Always," he whispered, kneeling, "always there will be wine for those who thirst." And sipping, he blessed the thought that had wriggled in his head, and clasped a secret that he would ever sing.

i i

To Phi Beta Kappas

BY JAMES C. HARWOOD

The altars of the ancient gods Are prostrate now. Their fires

Are dead, and all the sacred groves Are silent! Who aspires

To flatter Phoebus, or perchance

To woo the Sacred Nine?

To hymn chaste Cynthia's moon-girt charms, Or Bacchus, crowned with vine?

Perhaps some wearer of the Golden Key

May still be suppliant and devotee.

[ 17]

Inns and Taverns of Shakespeare's England

BY CATHARINE DAWSON

INveryearly times when London was still a fishing village all the trade of the north pas 'sed through Thorney on the way south. Hence it came about that this was the site of the first London inn. The inn consisted of small huts built side by side in two rows with narrow alleys between. Heating and cooking were provided for by a fire on an open hearthstone in the center of the huts. There was likewise a shopping arcade at the entrance to the inn where travellers might purchase all necessary articles-arrow heads, cooking pans, and skins. As London grew, Southwark became a fishing center. Many river side taverns were built where sea captains, pirates, and rovers met to drink and exchange news. Probably Shakespeare gained most of his knowledge of the sea and seaman's life from the sailors in Southwark, and it is even possible that some of the old sea-rovers amended his nautical passages.

In the time of this great playwright London was a little town with battlemented walls and towers with gates. The Thames, wide and beautiful, was in sharp contrast with the narrow, dirty streets of the town so overhung by inns' and craftsmen's signs that the gallants of the day had difficulty in avoiding the mud and at the same time trying to keep their plumes from being caught in the signs. After a tiresome journey over rutty, muddy roads frequented by robbers, an inn was a welcome sight to the traveller. Upon arriving at an inn the traveller was welcomed by the host or hostess, while the ostler ran to take his horse. Another servant took the guest to his room while still another pulled off his boots and cleaned them. The traveller had the privilege of dining alone or with his host, and might even go into the kitchen to supervise the cooking of his food. Gentlemen usually dined alone and were furnished music if they so desired. It was likewise quite customary for a guest to lay aside part of his supper for the next morning. Upon his departure if he were not satisfied with his reckoning the host satis"fiedhim. However, no gentleman would think of ever looking at the bill; only such people as merchants did [ 18 ]

!hat. A great event in the l!fe of an_innkeeper was the commg_of Queen Bess. Scurrymg, pamc, and fear were evident until the good queen approved. If she did not approve she never failed to make the host aware of the fact. Indeed she was often known to criticize the ale and slap the poor innocent "boots'.' as evidences of her displeasure. Elizabeth herself set a vigorous example for the drinkino- that was so common in the taverns. Once on a visit to Hatfield the Earl o_fLeicester wr~te to Lord Burleigh telling him the pathetic story of how it had been necessary for him to send all the way to London and Kenilworth to get ale-the queen's beer was so strong that none of the men could drink it.

The inns of Elizabethan, England, were large houses, comfortable and homelike. The chambers were lavender scented and ventilated by lattice windows. Broad stairways, oak panels and the great fireplaces gave a charming atmosphere to the inn. Some of the larger towns contained as many as sixteen large inns, to say nothing of small ones. Rivalry between hostelries was great. Each owner contended with the other for goodness of entertainment, fineness of linen, strength and variety of drink, and the care of horses. Since the master of the inn was responsible for his guests' property, the traveller was safe from robbery until he started out on the road. Often inn servants were in league with highway robbers. The servants were of no little help since they saved the valuable time of the busy robbers by ascertaining the wealth of the guests upon their arrival at the inn. They used cunning means of discovering the wealth of guests so that they might arrange without any inconvenience to themselves to rob all gentlemen who were heavily laden with gold. First the ostler es!imated the contents of the bags by their weight when he ~ifted them from the horse. If he met with no success the signal was passed on to the servant in the chamber who moved the bag from place to place for the better convenience of the guest. T?e gallant, having been to his room, descended the broad stairway to the room below where he c~lle1 loudly !or a ~up of sack. Having drunk this off, he paid his :eckonmg witho~~ a glance at the item on his bill. Then with a God be wi [ 19]

you, Ned," to the drawer and a sound kiss for the hostess he took his leave for a view of the town. Dekker in his humorous fashion_set forth some rules to be observed by the "gull" upon entering a tavern for refreshment. He must choose a companion slightly less ornately dressed than himself ( the better to show off his own finery), and walk up and down the room talking loudly. He must have nothing to do with anyone whom he does not know. 1 Of course the gallants followed the most ridiculous styles of the day, one of which was stuffing the legs of their breeches with bran or sawdust to make them stand out. However, due to the fact that the inn benches were sometimes rough, the gentlemen experienced some embarrassing moments.

Not only to the gallant did the inn offer hospitality but to everyone. This reputation for hospitality was of long duration since it went back to the custom of all wayfarers being entertained at the manor houses. Manor houses always had a coat-of-arms carved in stone on their outer wall. Hence when inns were established the natural course of imitating the arms of the lord of the manor, whose reputation for hospitality was already established, was followed In Shakespeare's time ;ilthough but few people knew how to read, all were able to understand the meaning of signs. The first general sigrn for an inn was a pole with a bunch of green hung on the end. A red lattice before a building also meant that ale was sold within. Innkeepers came to have signs wrought in iron by the best craftsmen of the day. However with narrow streets overhung by mammoth canisters, tea pots and frying pans, the pedestrians were often in such grave danger that a law had to be made governing the size and kind of support of these signs. Some of the inn signs which have no meaning at first glance really had much significance. An example of this is "Ye Old Dr. Butler's Head," established about 1610. The doctor whose head was represented on the sign was physician extraordinary to King James I. The story of Dr. Butler and his methods used in curing the various ills of the people of his day is fascinating to our generation. When Butler was a

1 Byrne, M. St. C.-Elizabethan Lif e in Town and Country. p. 265.

[ 20 J

you~g man he announced to his family his intention of beco~mng a doctor-a do_ctor of mirth. He went to Camb~idge but never to~k his degree. For many years he lived with John Crane, a Jolly and obese apothecary with whose help he concocted medici_nal ales which were ~old in many of the taverns. Some of this gentleman's cures are decidedly interesting to ~hose who feel that modern psychology has been the salvat10n of the world. One of his cures most freq~entlr used depended on gunpowder. If he suspected that his patie_nt was i~ need of a shock, he without warning shot off the pistol which he kept under a hat on the table for just such an emergency. This was excellent treatment for epilepsy. However his cure for ague was even more unique. It was when Dr. Butler was living in a house in London which was equipped with a balcony overhanging the Thames that he apparently cured the largest number of c·ases of ague. A man was posted under the balcony in a boat before the patient was ushered into the presence of the doctor. Dr. Butler engaged the person in conversation for a few minutes, then struck a bell, at which signal three stalwart men rushed in and threw the ill man into the waiting Thames. If the man in the boat was able to rescue the patient, the treatment was usually highly successful. In spite of his strange and strenuous cures, Dr. Butler became famous throughout England. "Ye Old Dr. Butler's Head" along with other more famous inns served to make English hospitality the delight and envy of all Europe. However this reputation for hospitality was sometimes a misfortane since it prevented the innkeepers from being able to discriminate between their guests. Discrimination is a word in great disfavor in our democratic country where no such thing is ever practiced 1 but of cour~e we ~us~ keep in mind the fact that the subject under discuss10n is one which pertains to unenlightened England of several centuries ago.

Discrimination was impossible not_on~y because ,of the long established reputation for hospita;hty but also, for more concrete reasons. If the host refused lodging to a cutthroat or thief he awoke some morning to find himself in a blazing house, or else he did not wake at all. There

[ 21 ]

were houses in London which were notorious for the wretches they harbored. As a rule London inns were houses frequented by thieves or were gentlemen's clubs where wit combats were held. People who shared in neither of these glories usually preferred to go on to one of the villages outside the city to spend the night. No doubt the inns offered innocent pleasures and were patronized by most of the English world, for only a few of the pious ancients wrote against them. Some lamented the part the church played in Whitsun-ales and wakes, but for the most part it was simply taken for granted that a man would sing his psalms just as reverently and as lustily for having supped heartily on good ale. There is every reason to suppose that Shakespeare sometimes frequented the taverns for in his plays he has many tavern scenes. Most famous of all perhaps are the "Boar's Head" scenes in Henry IV where Falstaff entertained the company with yarns of his bravery and skill in fighting. There is no real authority for stating that the "Boar's Head" was the inn at which Prince Hal and Falstaff met, but it is generally supposed to be. Queen Elizabeth dearly loved the old reprobate Falstaff, and insisted that Shakespeare recreate him. This he tried to do in the Merry Wives of !F indsor. It was at the "Boar's Head" that Prince Hal and his jolly companions were said to have heard with pleasure Falstaff's recounting of the story of how he was robbed by a hundred men, a large number of whom he overcame by desperate fighting. Here also one night when Falstaff fell asleep and was "snorting like a horse," his companions searched his pockets for the tavern bill which contained, among other items, two pennyworth of bread and two gallons of sack. The road near Gadshill was a source of nightmares to nervous travellers, for there Falstaff and his fellows with their accomplices, the inn servants, did a thriving business.

Other inns have become famous as the haunts of poets and writers of the day. The "Mermaid" and the "Devil and St. Dunstan" were the two inns most frequented by Jonson. This writer with his fellows, Carew, Donne, Seldon, Beaumont and Fletcher brought fame to the "Mermaid" rivalling that of the "Boar's Head." It is not known [ 22]

why Jonson transferred his patronage from the "Mermaid" to the "Devil," ~ut it was at the latter that the Apollo club met. Jonson en Joyed the knowledge that he was admired by the literary world, and with his club he was dominating. Some of the rules set forth by Jonson were that each should pay his own part of the tavern bill, there should be no disturbance about places, contests should be of books rather than of wir:ie, the company should be neither noisy nor mute, the wine should always be good, and raillery should be without malice. Though of course not mentioned in the rules, incense was said to be essential if Jonson was to be kept in a good humor. A tale is told which shows Jonson's ready supply of wit. The innkeeper was angry with Jonson for not paying his reckoning, but agreed to forgive him if he could say what would please God, the Devil, the company, and him. Jonson immediately replied:

"God is pleased when we depart from sin; The devil's pleased when we persist therein; Your company's pleased when you draw good wine And thou'd be pleased, if I would pay thee thine."

Just outside London at Enfield Chase was another famous inn, the "King and Tinker," which like the "Spotted Dog," was the site of an old royal hunting ground. The story is told that James I having become separated from his companions, stopped at this inn for refreshment. A thinker who was seated on a bench before the inn knew that the king often rode that way in the chase and expressed a desire to see him. James told the tinker to mount up behind him and they would soon see the king whom he would know as the only man who was covered. Soon they met a gr~at crowd. The tinker protested that he did not know the kmg for all were uncovered. Then said James, "It must be either you or me.m

One of the Southwark inns which is supposed to be of very early origin is the "Bear." In a poem writt~n in 1691 the heroes of the poem were described as coming to t~e "Bear which we soon understood was the first house m Southwark built after the flood.m However the date of 'Shelby, H. C.: Inns and Taverns of Old London. P· 14. ' Hughes, M. V.: A bout England. p. 113.

[ 23 J

establishment has been distressingly modernized to 1319. In merrie England it was probably the best known of all the . Southwark inns because of its enviable position at the foot of London Bridge which made it conspicuous to all entering or leaving the city.

Our knowledge of the men who kept inns seems to be limited to the fact that their favorite phrase was "Said I well?" and that the drawers were capable of nothing more than "Anon, anon, sir." No inn servant was credited with good character. Since nothing of the sort was expected of him, the servants seldom exerted themselves to the extent of being honest. In As You Like It Celia expressed this popular feeling when she said "the oath of a lover is no stronger than the word of a tapster; they are both confirmers of false reckonings." The expression "tapsters' arithmetic" also grew out of the fact that the drawers were not unwilling to charge their own prices to the young gallants.

The inns of Shakespeare's time, with their convivial gatherings and variety of pleasures, expressed the spirit of the age-a spirit of laughter and joy in living.

In Sodom Was a Child

BY RUTH FISKE

Flee thou away!

Wild fiames are leaping from a night Whose redness hides the days within. Oh flee and look not back upon These fired turrets which outblaze

The glanci'.ng hours that thou hast lived So blindly. Child of burning streets, Flee-flee until like others who

Have seen beyond these whirling flames, Thou suff'rest too.

[ 24 J

1' 1' 1'

The Song of the "Chinese Nightingale"

BY LOUISE DINWIDDIE

LoNG ago someone said poetry was the language of the soul. Dreamers read it to satisfy their aesthetic desire· beg~ars of lif~ read it to fo~get the dust of travelled day;. Its imperceptible or conscious rhythm brings new dreams new thoughts, new meanings. It is the discovered Elysiu~ of many, and its scintillating lantern of thought is a shining strange escape. In it are soft lights and colors and they make a shy sort of nightingale music.

In this new renaissance of twentieth century verse there is a soft tapestry, an oriental tapestry that hangs on the memory wall for poems, that gives renewed pleasure at each new vision, voicing a soft syncopated rhythm that lingers as the underlying refrain:

"One thing I remember, 'Spring came on forever Spring came on forever,' Said the Chinese Nightingale." 1

In an atomsphere as still and strangely silent as the treasured life of old China, now a new awakened China because

" 'San Francisco sleeps as the dead-' Only the 'big clock speaks with a deadly sound, While the monster shadows glower and creep The walls fell back, night was aflower, While Chang, with a countenance carved of stone, Ironed, and ironed all alone' ." 2

For one brief night, he dreamed his life again; though he saw the "western street-lamps gleam, though dawn was bringing the western day.m The lights and shadows are on the hot walls of the small ironing room, but Chang seems to have accepted all of life with its ugliness as well as its beauty its defeat as well as its triumph. If life was hurt ' 1 h "d 1· " for him by someone else, he remembers on y t. e ar _mg who hurt it and drinks his opium of dreams m the silver notes of his ~ightingale. He finds again his castles built "on

1 Lindsay, Vachel. "The Chinese Nightingale," in Prize Poems of 1929. p. 44. 'Ibid., p. 38. 'Lindsay, Vachel. "The Chinese Nightingale."

[ 25]

the sea sands brown," that time had washed into a sea of temporary forgetfulness. There is something of the fantastical element that reminds the reader of the Chinese Nightingale thatj sang through pages of Hans Andersen. There is the beginning of civilization behind the wall of China, before Confucius, before time, when there was only happiness as the "lady, rosy-red, with a fan," and "lanterns full of moon-fire" from her cheeks. 4

The element of time's endlessness is reiterated; from the "proud gray joss" we discover time then was only a length of burning perfume or an idol to be worshipped. It is patterned intricately with the symbols of China, "deathless bird ""firecrackers" a lady with a "tea-rose face ""gongs ' ' " of holy China," "dragons, red firecrackers ... and dragons, Chinese Dragons," "the black lacquer gate," "the mulberry shack," and "the almond tree"; it all untangles as simply as "the unwinding silk cocoon.m

The poem holds the Alladin in Lindsay-the Alladin peering into his magic lamp and -writing what he saw:

"Bring me soft song

This tailor-shop sings not at all. Chant me a word of the twilight Of roses that mourn in the fall. The fullness of life and Peace beyond peace, beauty to the eye." 6

Whether his shop is that of a tailor, or that of a Chinese laundryman, Lindsay holds the "Open Sesame" of words. He holds the mysterious inflorescence which is personality. The microism in man's mind. He dapples in twilight shades, violet, ivory, ebony, jade, and lets life mix in the brushwood. His song sings by his repetition of cadences, his love of imaginative activity, and the sound echoes in the hearts of us who remember we are only children, longing for our fairy tales of yesteryear. This "Chinese Nightingale" is just such a whimsical piece. It is his realization of life. He shares it in every word and endeavors to strike a responsive chord in his readers, for beauty. Here is the 'Ibid. 'Ibid.

6Lindsay, Vachel. "The Chinese Nightingale." [ 26 J

Lindsay who "splashes color broadly upon the universe sparkles, sputters and fizzles with his words. He has th~ imagination and sensitivity of the bards of Greece living in an immense mo1ern world, his vitality as a poet comes from the fact that he 1sdeeply rooted in civilization. His artistic heritage came to him from long, long ago-troubadours and bards and minnesingers and minstrels, from the makers of sagas and runes. He is an American minstrel." 1 Here is the Lindsay "singing to convert the heathen, to stimulate and encourage half-hearted dreams that hide and are lost in our sordid villages and townships." 8 He is not the noisy bard of the Congo, pulsating his rhythm with the sound beat of primitive life; he is handling deftly a dresden piece of old China, a delicate finesse of civilization's evolving crudeness. It lacks the boom-boom of the Congo, yet there is perhaps a similitude in the wild religion of the race. Like Frost he is making conscious the "beautiful art of hearing. "0 He is the student of sound combined with sense. There is no superfluity, nothing irrelevant; it is poetry simply sharing life in patterns of rhythmical words. He asks the reader only to feel, understand, and see beauty. He paints the Orient of long ago, traveling over roads where only aching, bound feet trod, feet that ached as the hurt of life; over roads dusty with the hope, dreams and_con_quests of a silent race. The lyrical cadence of the mghtmgale penetrates the soul as an east wind blowing through the perfumed fragrance of cherry blossoms. There is a breathless pause, a weight grows heavier on the heart:

"Years on vears I but half remember l\!Ian i; a torch, then ashes soon, May and June, then dead December, Dead December, then again June." 10

June, and hope again-the nightingale's song. It is always the upward lilt at the end of a line_that acts as a magnetic pole to keep faith to its star, and Lmdsay could not leave "Life ... a loom, weaving illusion ... "

7Wilkinson, Marguerite.: New f/ oic_es. p. 128.

8 Untermeyer, Louis: Modern American Poetry. p. 268. "Frost, Robert. (In an Address.) 10Lindsay, Vachel. "The Chinese Nightingale."

[ 27]

For heard again is the infinite echo:

"Spring came on forever, Spring came on forever." 11

Lindsay dFops a subtle psychology of life throughout his lines, and he sings his philosophy. "He goes back to the old Greek precedent every line - half-spoken, half-sung." "The Chinese Nightingale" strikes a new note as his reputation was degenerating or being lightly classed as entertaining. Here he shows his whimsicalness, a naive innocence in his imagination. The key pitch is high and delicate; there is not the penetrating terrified whisper from "The Congo."

" 'Blood' screamed" by "skull-faced lean witch doctors.m2 It is as soothing as its name, holds an interlinear delicacy of words, somewhere beneath the flat-iron of civilization is the faint soft strains of lost songs that used to be sung in our hearts as the fairy tales of long, long ago. It is decidedly the antithesis of his "Santa Fe Trail" that sings so loudly the tune of modern life, and gives its conscious rhythm, its discord, crash, blare, hurry, shrill voices. It is only in a shy Rachel-Jane that he plays a bit of melody.

There is also a phantomness in the "remembers" that may be compared with the "Ghosts of the Buffaloes." There is the same background of a once superior power. Again the red "fire-crackers," symbolic of intensity and the twin "red-god show," "crimson fires,ma and the throbbing hoof beats symbolizing the power of the buaffloes. There is the same fantastical element. The pattern words of both poems have the same etherealness. Those of the nightingale ar silver: "silvery name," "gray bird," "Moonlit bower," "silver seas," "silver lilies," "silver fishes," "silver junks. " 14 There is a same cobweb of silver in the "whispering stream," "winds and snows," "sleep," ~'breath of stars" in ,

11 Ibid.

12 Untermeyer, Louis. Mod. Am. Poetry. p. 272.

18 lbid.

14Lindsay, Vachel. Prize Poems. p. 30-44.

t~e '.'Buffaloes.ms There is the same dream element also; a similar sound and meaning in the lines :

''Life is a dream, the sigh of the skies."16 0 and

"Life is a dream weaving musion." 1 1

But of all his poems, "The Chinese Nightingale" alone vy-eavesthe most d_e~icatedreams upon the thoughts of its l~s~ene~s. It~ ~xqmsite phra~eology, gracious rhythms, dehci?u_s ima_grnrngs, str?ng original qualities, uniquely leave t~eir impnnt as _the picture painted of Chang, ironing the mght away. It is beauty soft and padded as old oriental tap~stries, of wild flowers, bird song, letharg~-a new genrn of lost truth. The Chinaman like his poem has labor as a part of life; so must there be travail before beauty is born; so must there be pain before happiness is most realized. Emotional restlessness is ironed away as deftly as a wrinkle in any bit of fabric. There is the slant angle of vision peculiar to the Eastern eye; there is a light flash of imagination which much of the world sees as only the blind spot of the eye, that gives his ultimate truth, a glimpse of the uni verse as their God sees it; an air bubble of fancy giving a light glitter enshrining Oriental idols. It is the ancient and everlasting theme of Eastern life, long forgotten by moderns, if ever known.

The song of a nightingale has ever been the silent song of poetic souls, silent because the words are mute until an artist who loves beauty transmutes them to his own tongue. A song with memories, always remembered from somewhere heard a song coming from the inmost recess of the heart as unc~ntrollably, as unconsciously, as the tears that jewel its poignant memories; its everlasting echoes of things past; when a soul found life cynica~ an1 ludicrous, yet silently groped in its own shadow, whil~ life we~t harshly on. A song of intangible, misty mem?ne~, r_ust!ing leaves of gossamer delicacy; a song benumbing _inits _1oy?usness. Keats felt this and wrote his lines throbbing with its loveliness:

"Ibid.

' 0 Ibid. 11 Ibid.

t 29]

''That I might clrink, and leave the world unseen And with thee fade away into the forest dim." 18

There is a refrain of ancient days:

"No hungry generations tread thee down; The voice I hear this passing night was heard In :mcient days by emperor and down :19

Shelley wrote too of the nightingale, in an ethereal tone of dreams:

''That sweet bird, whose music was a storm Of sound, shook forth the dull oblivion Out of their dreams; harmony became love In every soul but one." 20

Coleridge knows this bird a,s Nature's playmate, the bird who knows the "moon," and "evening star," and sings them to his listeners. vVordsworth, another companion of nature, finds solace and joy in its song:

"As if the God of wine Had helped" it and finds therein

A song "of love and quiet blending, Slow to begin and never ending; 0£ serious faith and inward glee." 21

Always through the years has the song of the nightingale been the song eternal, but never has one held such a breath of beauty, too lovely to perish, a song which will echo through the distant corridors of time forever, "The Chinese · Nightingale."

It holds the "teaism" of Japan. That "cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of every-day existence;" 22 (Okakura-Kakuzo-"The Cup of Humanity") that which represents so much of the Art of Life which Chang was beginning to see in the charcoal shadows in the narrow walls; while far back in a dreamland he had known the "moon wandered aimlessly among the wild charms of night ... brightening the bamboos ... the soughing of the pines heard in the kettle" ... and he

11'Keats, John. "Ode to Nightingale," in Songs of Bii·ds. p. 179.

' 0 Ibid.

"'Shelley, Percy. In Songs of Birds. p. 186.

"'Wordsworth, William. In Songs of Birds. p. 231.

22 Okukara-Kakuzo. "Cup of Humanity," in World's Best Maps. p. 108.

[ 30 ]

"dreamed of evanescence and lingered in the beautiful foolishnss of things." 23 There is something in the choice and arrangement of words that su&'g_estslotus blossoms, a magic touch of perfume. The repetition of the word "rainbow" imparts a thought, perhaps the gold of it was held in the ancient bronze or the lacquered ebony of old China that Chang remembered.

The ori_ginal pictorial bea~ty gives_a negative meaning to cymbalist as a name for Linsay. Lindsay being also an artist of the pen has outlined with the pencil too that Baconian element of strangeness in the proportion which gives the fi~al touch of beauty. In February of 1918, Lindsay was given a full chorus of twelve girls selected for their speaking voices to act "The Chinese Nightingale." The performance was a success; it realized something of Lindsay's idea of the union of arts with poetry at the centre. His fine phrases are remembered as the ''tinkling wind-bells in the garden" or like snow upon the desert's dusty face, lighting a little hour or two, then gone; or like the still small voice after the lightning and thunder. 24

The poem goes back to the origins of the art. He resembles Yeats in that he wants to restore the primitive singing of poetry. He has something of the Irish element in it. The titles of other various poems, The Tree of Laughing Bells, or Wings of the Morning, suggest his love of resounding harmonics, his range of imagination. "His finest work always combines these two ele_ments, melody an_d elevation. He is a Puritan with a passion for beauty; he is a zealous reformer with Falstaffian mirth.m s There is something of Spencer's Faerie Queene in its combination of ravishing sweetness and moral austerity, not the "man on horseback who rode later roughshod over every bloom of beauty that lifted its de!i'cate head." He is a mission~ry who has gone to China for dreams to teach dreams with oriental net-work, tinking with their

23 Okakura-Kakuzo "Cup of Humani ty ," in World's Best Map. P· 113. ~'Phelps, Wm. Ly~n. Poety in Twentieth Century. p. 223 .. Phelps, Wm. Lyon. Poetry in Twentieth Century. p. 229.

[ 31 J

"Unravelling, final tune, Like a long unwinding silk cocoon." 26

The voice of Chang here reminds one of the vagabond Lindsay whose "heart with its exultant blood seemed but the curve of a cataract over the cliff of his soul," and has his philosophy of life that "when things have their proper rhythm, life and death are interwoven like pillows plaited for a basket.m 7

In the last stanza division of the poem there is a silence, somewhere "in the red cave of the heart" there is a listening in the silence. For "silence is the element in which great things fashion themselves together, that at length they may emerge, full-formed and majestic, into the day-light of life, which they are henceforth to rule.ms It is when the lips are still that the soul awakes. So waked the soul of Chang, with "peace at last." 'He had not stood upright and ironed his soul flat from the world and lived behind the light in his eyes, with his nightingale singing somewhere to "the rhythmic sound of old dreams in a tumbled sea of dreams." He forgot the proud gray joss in the corner and tho' with a "countenance carved of stone," he remembered one thing, '' ' Spring came on forever, Spring came on forever.' Sang the Chinese Nightingale." 29

20Lindsay, Vachel. "Chinese Nightingale" in Prize Poems. p. 43. "'Lindsay, Vachel. An Handy Guide for Beggars. p. 177 .,,Maeterlinck, M. "Silence" in World's Best Map~. p. 436. '"Lindsay, Vachel. "Chinese Nightingale" in Prize Poems. p. 44.

[ 32] 0