‘Dazzling. Sweeping. Mind-altering. World-changing. This is a once-in-a-generation contribution.’

NAOMI KLEIN

‘Dazzling. Sweeping. Mind-altering. World-changing. This is a once-in-a-generation contribution.’

NAOMI KLEIN

ALSO BY GREG GRANDIN

The End of the Myth

Kissinger’s Shadow

The Empire of Necessity

Fordlandia

Empire’s Workshop

The Last Colonial Massacre

The Blood of Guatemala

Greg Grandin

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Torva an imprint of Transworld Publishers

This edition published by arrangement with Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, division of Penguin Random House LLC 001

Copyright © Greg Grandin 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Designed by Alexis Farabaugh Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBNs:

9781911709909 hb

9781911709916 tpb

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Eleanor and Manu, and for Diane, much missed

“I can see America seated on liberty’s throne, wielding justice’s scepter, crowned with glory, revealing to the Old World the majesty of the New.”

SIMÓN BOLÍVAR, 1819

“Can we, the Republics of the New World, help the Old World to avert the catastrophe which impends? Yes, I am confident that we can. . . . We offer hope for peace and a more abundant life to the peoples of the whole world.”

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT, 1936

47.

48.

49.

50.

The traveler sat silently in Quaker meetings for hours during the day and visited brothels at night. In Philadelphia, he watched a raucous crowd welcome the arrival of George Washington, with men, women, and children as ecstatic as if “the redeemer had entered Jerusalem.” General Washington, the Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda wrote in his journal, was magnificent in his bearing and grace. He embodied virtue, and focused all the New World’s desires for independence into a single flame— a flame, Miranda said, that belonged to all America.1

Miranda, as a colonel in the Royal Spanish Army, had already fought on the side of the North American rebel colonists during the bloody siege of Pensacola. He would later go on to defend the French Revolution and lead one of Spanish America’s first independence movements. Now, in the middle of 1783, he was beginning a yearlong tour of the new United States. Miranda wanted to see how the world’s first modern republic fared. He spoke with tradesmen, farmers, and Revolutionary War veterans. In New York’s Hudson Valley, he waxed lyrical about the sweet “grasses of the field” and mistakenly assumed the Catskills were North America’s highest point. He dined in gentry estates even as he noticed much hardship amid the wealth. Many of New York’s Dutch-speaking farmers couldn’t afford shoes, while the well-off, men and women alike, adorned themselves with silks,

perfumes, pomades, and powders. The money spent on such “vanity,” he noted, would cover a year’s interest on the new country’s war debt. New York’s politicians and preachers professed abolition, Miranda noted, yet slavery still existed in the state. “The number of Negroes is large.”

In Boston, he was introduced to Phillis Wheatley, a formerly enslaved West African woman who had won her freedom and became a celebrated poet only to die penniless. Miranda cited Wheatley as proof that all humans, regardless of color or sex, were rational beings. Miranda’s family in Caracas owned slaves, as did Miranda himself. They lugged around his famous library, many bundles of papers and an ever growing number of books. While in Philadelphia, he purchased the indenture of a Scottish boy who had arrived in port on a ship carrying over three hundred shackled Africans. But Miranda would soon embrace the abolitionist cause, as part of a broader belief that all the subjugated peoples of the Americas should be liberated, including Native Americans. When the New World was finally free, Miranda suggested, it might be called Columbia , with the English-language u instead of the Spanish o (as in Colombia), a spelling he picked up from Wheatley’s ode to Washington: “Celestial choir! enthron’d in realms of light, Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.”2

The Venezuelan thought both Native Americans and women were more oppressed in the new English-speaking republic than in colonial Spanish America. In the United States, the wives of revolutionary leaders were forced into a “monastic seclusion, and such submission to their husbands as I have never seen.” Boston’s General John Sullivan, who gained fame pacifying the British-allied Iroquois, kept “his wife and numerous children completely segregated from society and without giving the latter formal education.” Miranda, his journal pages full of detailed sexual encounters, was appalled when a Shelter Island parson refused to baptize a baby conceived prior to wedlock.3

In New Haven, Yale’s president, Ezra Stiles, gave him a tour of the university. Miranda sat in on a Hebrew lesson, which he enjoyed, and was pleased that Optics and Algebra were taught “simply and naturally.” He was shocked, though, that the university offered no modern-language instruction, a bad omen for educating modern citizens, thought Miranda (who

spoke English, French, and Italian, and read Greek and Latin). Nor was he impressed by Yale’s library: “nothing special.” He read Cotton Mather’s history of New England as “curious evidence of fanaticism.” And kept himself busy in Sunday New England with a pack of playing cards and flute practice, which violated strict Sabbath restrictions. No kite flying either. Stiles, in his own journal, called Miranda a “flaming son of liberty.”4

Miranda took in the full variety of the new republic. He was welcomed everywhere he went, though he was often mistakenly introduced as a Mexican. Most men were polite but also, he thought, “unsocial,” or huraño, that is, aloof and disinterested in the wider world.

Some of the people he met did ask questions about Spain’s American empire. Others proved stubbornly ignorant. In Providence, Miranda visited the estate of Esek Hopkins, who had commanded the rebel navy during the Revolution. Miranda made mention of Mexico City and was surprised to hear Commodore Hopkins respond by saying that there was no such place. A century earlier, New England Puritans had been entranced by Mexico City, the command center of New World popery, with its wide cobbled streets, many horses, and fine carriages. Now, when Miranda tried to correct Hopkins, the Commodore refused to believe him. “Very vulgar,” Miranda wrote in his journal of the encounter. He found most of the university presidents he met to be equally provincial and pedantic.

Miranda admired the United States, its dynamism, and early steam power. He liked the psalm singing of Methodists and the organ playing of Episcopalians but was taken aback at how strictly religious most people were. He thought river baptisms absurd, that they indicated a stubborn literal-mindedness. There was too much pulpit “braying” of hatred directed at Jews, Catholics, and Muslims. Miranda singled out one parson for praise, James “Redemption” Murray, who preached that there was no such thing as damnation. “Salvation was universal,” Murray said, which Miranda found refreshing compared to Catholic and Protestant brimstone.

Miranda was catching the first notes of the Second Great Awakening, a religious revival movement that went in many directions. There was the harshness Miranda criticized, but also a passion for political reform, for making the United States a vital, healthy, democratic, and energetic nation.

He was repulsed by the return of Cotton-Matherism, but compelled by the energy, by the expectation, the scent of something new on the morning wind. And he shared with many of the leading figures in the Awakening the conviction that America, which for him meant all of America, was history’s redeemer.5

One gets a sense from Miranda’s diary that he hoped the new United States would overcome the problems he recorded: poverty, slavery, the subordination of women, a tendency toward antisociability, and an occasional flash of unflattering self-regard. The diary also makes clear that Miranda wasn’t sure that it could.

S outh America will be to North America,” declared the North American Review early in the 1800s, “what Asia and Africa are to Europe.”6

Not quite.

Europe’s liberal capitalist powers— Great Britain, France, and the Netherlands—would rule over culturally and religiously distinct peoples in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. British travelers to India made much of the impenetrability of Hinduism, with its jumble of noises, colors, deities. “There is no dignity,” said E. M. Forster after entering a temple to witness a celebration of the birth of Krishna, “no taste,” in what Indians call ritual. Only chaos. Forster was overcome by India’s mulligatawny metaphysics, the barrage of chants, ecstatic dancing, and indecipherable music. “I am very much muddled in my own mind about it,” he wrote. Forster worked the experience into his novel A Passage to India , writing that nothing the worshippers did seemed “dramatically correct” to the non-Hindu observer. It was, he thought, a jumble, a “frustration of reason and form.” 7

There was no frustration, not of reason nor form, when English and Spanish Europeans, Protestants and Catholics, engaged with one another in the New World. Miranda saw the differences separating Boston and Caracas society, but they didn’t muddle his mind. An indifferent Catholic, he didn’t like Protestant braying. But as a Christian, he understood the theology of the brayer.

The republican insurgents who broke from Great Britain defined their

system of liberties against what became known as the Black Legend, a compound of negative stereotypes that held the Catholic Spanish Empire to be especially cruel and corrupt. The Legend, though, was legible, emerging from Europe’s political rivalries and religious schisms, its scientific revolutions, renaissances, and enlightenments.

When on one Sunday in 1774, future presidents George Washington and John Adams wandered into Philadelphia’s new Catholic Cathedral, they appreciated the priest’s sermon on the duty of parents to care for the spiritual and temporal well-being of their children. Adams, though, in a letter posted to his wife, Abigail, said that he was dismayed at the servility of the congregants, as they fingered their beads, crossed themselves with holy water, and chanted Latin incantations. A painting of “our Savior” in his “agonies,” blood streaming from his wounds, appalled him. So did the Church’s dominion over the senses: “Everything which can lay hold of the eye, ear, and imagination”— organ music, Latin prayers, stained glass, velvet and gold cloth covering the pulpit, the lace of priests’ vestments, candles, crucifixes, and statues of the saints— combine to “bewitch the simple and ignorant.” “I wonder how,” he wrote to Abigail, “Luther ever broke the spell.”8

The freethinker Adams’s contempt for Catholic superstition mirrored the freethinker Miranda’s for Protestant fanaticism, and later, when Adams searched for some way to describe Francisco Miranda’s revolutionary enthusiasms, he reached for a satire that all literate people in the Americas, of a certain class, had read, either in its original Spanish or its many English translation editions: Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The Venezuelan, Adams said, was “as delirious as his immortal countryman, the ancient hero of La Mancha.”9

There was an intimacy to such disdain, with both disdainer and disdained living in the same ideological village, sharing the same Savior, the same republican patois, reading each other’s books. Adams might have thought Miranda, and other Spanish Americans of his generation, foolish. But they were not inscrutable. They were not the incomprehensibles Forster found in Krishna’s temple. American insurgents, whether they spoke English or Spanish, inherited a set of common assumptions related to the dominance of Christianity and the fight against monarchism. They were mostly

all republicans. Some were loosely deists, in one fashion or another, and most were Freemasons, some more anticlerical than others. And they all believed that the right to govern required the consent of the governed, even if that consent needed to be overseen by a caste of elites schooled in the virtues of civic republicanism.

The men who would topple the Spanish Empire in the Americas felt they had a kindred spirit with their English-speaking counterparts. They looked to the North American revolution for inspiration, hoping that once Spain was thrown off they might replicate its system of liberties, representative government, and equality under the law. In any case, they shared a faith in the redeeming power of the New World, that America was more an ideal than a place.

Simón Bolívar and Thomas Jefferson could at times sound as if they had fallen into a cataleptic trance as they prophesized the future. “It is impossible not to look forward to distant times,” Jefferson wrote, when the United States will “cover the whole Northern, if not the Southern continent with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms.” Bolívar imagined himself flying “across the years” to a moment when America had united the world under a system of rational laws, with the Isthmus of Panama a planetary capital, binding north and south, linking east and west. Greece and Rome had its laws and philosophies, but, really, asked Bolívar, what was “the Isthmus of Corinth compared with that of Panama?” Miranda conspired with Alexander Hamilton to liberate all South America, believing their escapades would “save the whole world, which is oscillating on the brink of an abyss.”

And yet. When Jefferson and Adams used the word America , they were referring to the United States. When Bolívar, Miranda, and other Spanish American republicans used the word America , they meant all the Americas. “Our dear Country America, from the North to the South,” Miranda wrote Hamilton. Who is an American ? And what is America ? These questions go back a long way. “I that am an American,” affirmed Cotton Mather in the early 1700s. In 1821, the radical Catholic priest Servando Teresa de Mier— born in north-

ern Mexico to a family that traced its lineage back centuries to the first dukes of Granada— also thought himself an American. Having escaped the dungeons of the Inquisition, Mier had set up a printing house in Philadelphia to publish books banned by Spain. He complained, in a letter he sent to a revolutionary compatriot, about the way English speakers used the word America. There were two problems, actually. The first was the constant equation of Spanish American with South America. Mier was tired of pointing out to his English-speaking acquaintances that North America was also Spanish America— that there were more Spanish speakers in Mexico (which at that point ran well into what is today the United States’ Southwest) than in all South America.10

The second problem was that each European empire used the word America to refer only to their colonial or former colonial possessions. Great Britain called the United States America, Spain called its colonies America, Portugal referred to Brazil as America, France and the Dutch did the same for their Caribbean islands. It is as if, Father Mier said, “there is no other America other than the one they dominate.” “A thousand errors,” he said, lamenting how America was fractured by such usage. All the New World is America.

Confusion was natural. America, for Anglo settlers before their revolution, was both the entire New World and their sliver of that world— both their narrow dominion of a thin slip of land between the Alleghenies and the sea and all the land west of those mountains. In 1777, the Articles of Confederation named the new country the United States of America, but also referred to it as just America. Europeans liked to point out that the “United States” wasn’t really a “proper name” but rather an adjective attached to a generic noun.

Washington Irving agreed. Irving wanted “an appellation” of his own to ensure that he wasn’t confused with a Mexican who by rights could also call himself an American. He wanted a name that would identify him as “of the Anglo-Saxon race which founded this Anglo-Saxon empire in the wilderness.” He suggested Appalachian or Alleghanian. The New England social activist Orestes Brownson thought such ideas rubbish. The “name of the country is America,” he wrote in 1865, “that of the people is Americans.

Speak of Americans simply and nobody understands you to mean the people of Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Chile, Paraguay, but everybody understands you to mean the people of the United States.”11

Brownson was right at least about royal Canadians, who tended not to call themselves Americans to distinguish themselves from their Englishspeaking republican neighbors. But Mexicans, Brazilians, Peruvians, Chileans, and Paraguayans all thought themselves Americans, as did the Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda. Nosotros los Americanos—We, the Americans—was how early Mexican nationalists called themselves. Somos da América e queremos ser americanos, said Brazil’s republican leaders, who wanted to overthrow their monarch: We are from America and want to be Americans.12

Proprietary claims to America became politicized over time, serving as stand-ins for struggles about more substantive issues. “We’ve lost the right to call ourselves Americans,” the Uruguayan Eduardo Galeano wrote in 1971. “Today, for the rest of the world, America means nothing but the United States. We inhabit at best a Sub-America, a second-class America of confused identity.” “We are more American,” goes a song by the Mexican norteño band Los Tigres de Norte “than the sons of the Anglo-Saxons.” Los Tigres are a favorite of migrant and borderland workers, suggesting the matter is not just a concern of literate elites.

In 1943, the diplomatic historian Samuel Flagg Bemis struggled to decide what adjective he should use to refer to the United States, reluctantly settling on American. It sounds better, Bemis wrote, than “the less euphonious adjective United States.” Latin Americans will occasionally refer to the United States as América del Norte, but generally use Estados Unidos and estadounidense, which in Spanish with all its rolling vowels is euphonious, mellifluent even.13

I’ve written this book not to fuss over names but rather to explore the New World’s long history of ideological and ethical contestation. Philosophers use the phrase immanent critique to describe a form of dissent in which challengers don’t dismiss the legitimacy of their rivals’ worldview but rather

accuse them of not living up to their own stated ideals. It’s a useful method for considering the Western Hemisphere, for Latin America gave the United States what other empires, be they formal or informal, lacked: its own magpie, an irrepressible critic. Over the course of two centuries, when Latin American politicians, activists, intellectuals, priests, poets, and balladeers— all the many men and women who came after Miranda—judged the United States, they did so from a shared first premise: America was a redeemer continent, and its historical mission was to strengthen the ideal of human equality.

One can’t fully understand the history of English-speaking North America without also understanding the history of Spanish- and Portuguesespeaking America. And by that history, I mean all of it: from the Spanish Conquest and Puritan settlement to the founding of the United States, from Indian Removal and Manifest Destiny to the taking of the West, from chattel slavery, abolition, and the Civil War to the rise of a nation of extraordinary power—from the First World War to the Second, from the Monroe Doctrine to the League of Nations and the United Nations and beyond. And the reverse is true. You can’t tell the story of the South without the North.

But America, América is more than a history of the Western Hemisphere. It’s a history of the modern world, an inquiry into how centuries of American bloodshed and diplomacy didn’t just shape the political identities of the United States and Latin America but also gave rise to global governance— the liberal international order that today, many believe, is in terminal crisis.

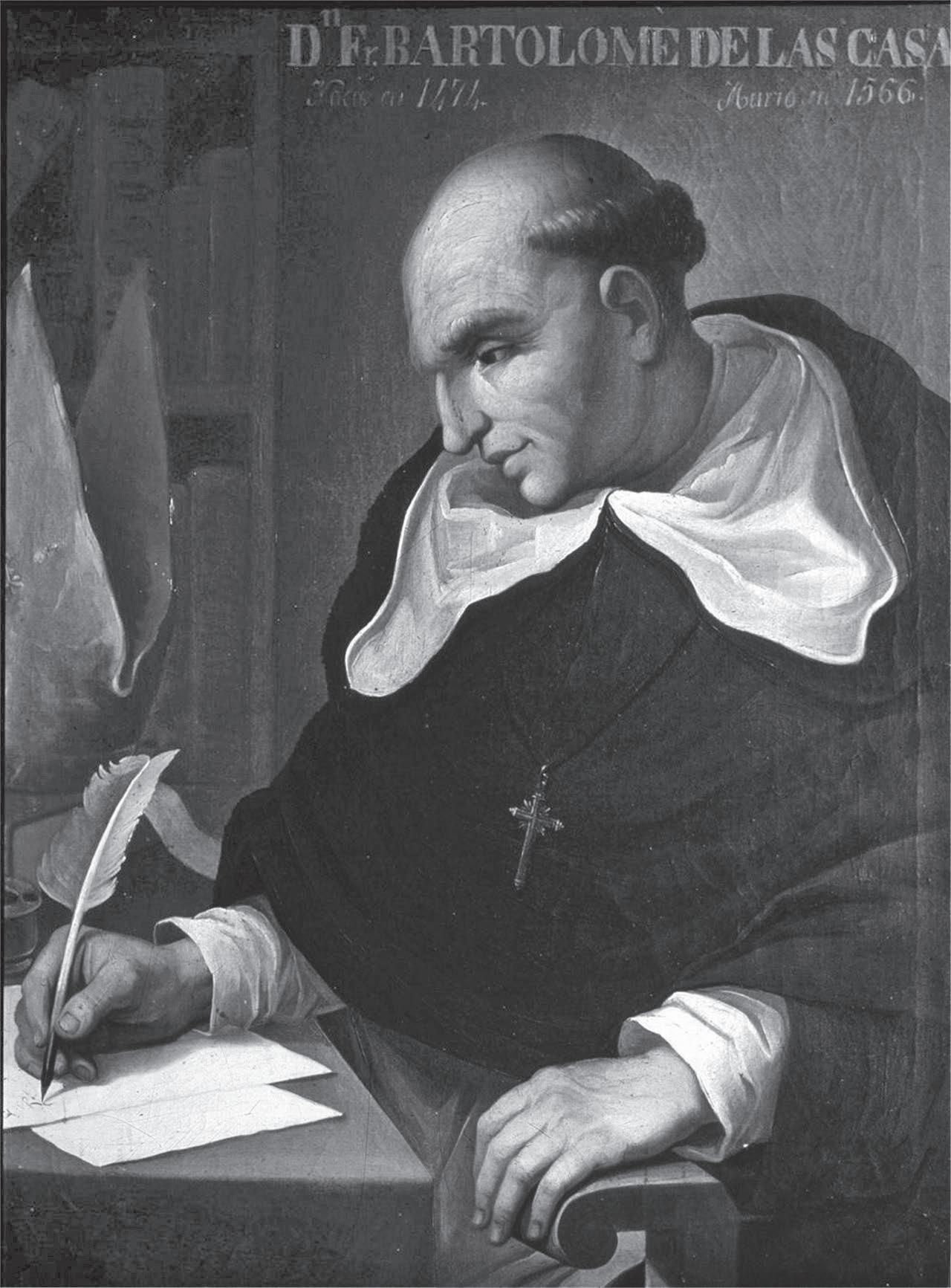

The book starts with the Conquest. The astonishing brutality that Spain, in the first decades of the 1500s, visited on the people of the New World shocked the Catholic realm— Europe’s realm— leading to a reformation within Catholicism, a dissent as consequential as Luther’s. The Catholic Church claimed to be universal, the agent of human history and bearer of humanitas, all the world’s wisdom. And what had that wisdom wrought? Carnage unprecedented. The slaughter, which inaugurated what scholars place among the greatest mortality events in human history, forced theologians to consider Catholic claims to universalism with new attention. Many of these clerics wound up defending Spanish rule, not so much dehumanizing America’s native peoples as refusing to admit they were human at all. Those

who died by the Spanish lance, or by European diseases, were of a lesser kind than those people who lived in Europe— defective, not touched by the divine, but rising from the muck and mire. Their dispossession and enslavement were allowed.14

Others dissented—first among them Father Bartolomé de las Casas— realizing that what had previously been called universal was but provincial, that Europe was just a farrago of fiefdoms whose princes and priests knew nothing about the fullness of the world, nothing of its hitherto undisclosed millions. The dissent of these theologians and jurists has rung down the centuries. Protestant England paid attention to the interminable Spanish debates, to the Catholic friars who insisted on the humanity of the New World’s people, and wondered if they might secure their settlements, in Jamestown and Plymouth, on more defensible principles. They couldn’t. They opted for evasion.15

Then came the Age of Revolutions, when the New World broke free from the Old. The United States did so first— a republic alone, as many of its leaders imagined, an “Anglo-Saxon empire in the wilderness.” Spanish American nations, in contrast, came into being collectively, an assemblage of republics, an already constituted league of nations. They had to learn to live together if they were to survive. And they largely did so, with their intellectuals, lawyers, and statesmen elaborating a unique body of international law: doctrines, precedents, and protocols geared not toward regulating but outlawing war, not adjudicating conquests but ending conquest altogether.

But how to contain the United States? The hemisphere’s first republic seemed more a force of nature than a political entity. More than one of its founders said they could see no limits to its growth, that once they drove the natives beyond the stony mountains they’d soon fill both North and South America with Saxons. What to do with a kinetic nation that believed itself to be as universal as Christianity, as embodying the marching spirit of world history?

What Spanish and Portuguese Americans did was update the criticisms aimed earlier at Spain during the Conquest and directed them at the United States. In so doing they sparked a revolution in international law.

The triumph of liberal multilateralism after the Allied victory in World

War II (especially the nullification of the right of conquest, the prohibition of aggressive war, and the recognition of the sovereign equality of all nations) is often narrated as a transatlantic story, a fortuitous evolution of ideas. Concepts in their infancy during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries grew stronger in the nineteenth, matured in the twentieth century’s cataclysmic wars, and then found their moment in a series of meetings in the last years of World War II: Moscow, Tehran, Dumbarton Oaks, Yalta— onward to the establishment of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945 and the UN’s ratification of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

Most scholars ignore, or pass quickly over, Latin America when considering the founding of the League of Nations, and then the United Nations. It’s a curious indifference, for the English-speaking statesmen involved in founding global governance, along with those who laid prior groundwork for such an effort—Woodrow Wilson, Andrew Carnegie, Nelson Rockefeller, Henry Wallace, Sumner Welles, and Winston Churchill, among others— openly and repeatedly held up the New World as what the whole world should look like. Wilson often said that Latin America was the model for what he had hoped to accomplish in Paris. FDR told Stalin that Pan-Americanism would be a good template for a postfascist Eastern Europe.16

America, América argues that the New World’s magpie rivalry, its immanent critique, played a vital role in the creation of the modern world, shaping its economics, politics, and moralities. The Protestant settlers who colonized, followed by the republicans who revolutionized, North America looked to Spanish America not as an alien other but as a competitor, a contender in an epic struggle to define a set of nominally shared but actually contested ideals: Christianity, freedom, law, sovereignty, property, equality, liberalism, democracy, and, above all, the very meaning of America.

A merica for America,” said Washington’s leaders as they tried to fashion their relationship to the hemisphere’s new nations in a way that was, as the North American Review suggested, something like London’s to India.

“America for humanity,” Latin Americans answered back.

Philosophy begins in wonder, Socrates said. It matures, Hegel added, in terror, on the “slaughter bench” of history. So it was with the arrival of the Spanish in the New World.1

Wonder there was when Christendom realized there existed another half a world, filled with rarezas, rarities, curious plants and animals but above all people, many more and many more different kinds than lived in all of Europe. Even before Copernicus, Europe was awakening to the idea that the Earth wasn’t the center of existence, and that the universe contained, Giordano Bruno would soon reckon, “innumerable suns” and “infinite earths that equally revolve around these suns.”2

Scholars intuited a link between the celestial and earthly multitudes. There was one heavenly realm, containing an incalculable number of stars. There was one earthly estate, now known to contain many more millions of people than previously imagined. The realization that the earth was not the center of divine creation was as unsettling as the knowledge that Europe wasn’t the center of the world.

What did this multiplication mean for the idea of Catholic holism, for the story of Genesis when God at Creation called into being first Adam, then Eve, who together produced a single linaje, or lineage, of descendants with a shared, if gory, history?

When reconciled with the Catholic premise of celestial unity, the diversity of the New World’s peoples could support the ideal of equality. Time spent in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America convinced the Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas that the ancient philosophers and theologians who had argued that there existed categories of inferior humans, people born to be “natural slaves,” were wrong. As it turned out, Las Casas wrote, the ancients didn’t “know very much” about the world. The Dominican would continue to cite the sages when it suited his purpose, but for him, now, truth was to be found not in Aristotle but in America— and the most important truth was that humans everywhere were fundamentally the same. All were made in God’s image. Their differences— skin color, hair texture, cultural practices, and religious beliefs—reflected the vast variety of the infinite divine.

And differences in appearance had nothing to do with human essence, which for Las Casas was everywhere the same. Every Indian he had met in the New World, he said, possessed both free will and the ability to reason. That alone made them human. They could remember the past, imagine the future, estimate probabilities, and could see, hear, feel, smell, and taste. They were born, matured, grew old, and became ill, and when they died their families grieved, as humans did everywhere. When happy, they laughed. When sad, they cried. They took delight in the good and despised the bad. From this, Las Casas issued a famous declaration: Todo linaje de los hombres es uno — All humanity is one.3

At the same time, the New World’s conquerors mocked the idea of humanity’s oneness, laying the foundation for race supremacy. Spanish settlers and colonists legitimated cruel killing on an unprecedented scale, forcing the New World’s inhabitants to labor in mines, fields, and waters, to extract the riches of America— gold, silver, pearls, dyes, and soon sugar and tobacco— that Europe would use to gild its empires, muster its armies, fund its wars, build its cathedrals, and pay for more voyages of conquest and enslavement. Never mind what priests like Las Casas were saying. Theologians were known to say one thing and its opposite. Indians were little better than apes put on earth to serve man. To dominate them was just. To work them to death no more a sin than to butcher a hog.

The people of the New World were “found.” Then they were lost. Not immediately and not completely, but enough so that a group of Dominican and Franciscan priests wrote their superiors in Spain in 1517 wanting to know where they went. “Where are they, oh most illustrious fathers?” What happened to the men and women who upon Columbus’s arrival two decades earlier were so many that they were like “leaves of grass?”4

Demographers today aren’t sure what the size of America’s population was before the arrival of the Spanish. Most estimates fall between fifty and one hundred million inhabitants. The Spanish couldn’t say. They knew that the Indies (the name América was in use for the New World in the early 1500s but not widely adopted until a little later) were densely populated with wildly varied peoples. They ranged from the elysian Taino, who seemed to have lived lush and well-nourished lives on the islands of the Caribbean; to the hierarchically organized, ostentatious, and scientific Aztec and Inka Empires in Mexico and Peru. Columbus thought the island of Hispaniola— Spain’s first Caribbean colony, from where Hernando Cortés would soon lead his assault on Mexico—was “paradise,” but a populated paradise, completely “cultivated like the countryside around Cordoba.” He estimated that the island was home to over a million souls. Las Casas, who was seventeen years old when he arrived in the Caribbean on April 15, 1502, thought that number too low. “An infinity of people” lived in the new lands, he later wrote. The New World was “filled with people, like a hive of bees.”

“It was,” he said, “as if God had placed all, or the majority, of the entire human race in these countries.”5

Later, European romantics would use the word sublime to describe the sensation evoked by confrontation with the grandeur and terror of nature, its existential enormity. And there’s some of this feeling in the letters and chronicles left by Spanish warriors. As the Conquest proceeded, as Cortés began his march through Mexico, they wrote of their exploits climbing high peaks equal to the Alps, navigating great river systems, and trekking through dense forests. The volcano Popocatépetl rained fire and ice, bursting, Cortés

wrote King Charles, with “so much force and noise it seemed as if the whole Sierra was crumbling to the ground.”

Yet it wasn’t nature that bedazzled the Spaniards as much as the “great city” of Tenochtitlán sitting below the volcano. “As large as Seville,” Cortés wrote, and more populated than London, with “many wide and handsome streets,” fine noble houses, engineered canals, and a complex hydroponic agricultural system. Further south, it wasn’t volcanic eruptions that shivered European souls. It was Mapuche warriors overspread across a vast Andean valley mustered to defend their land. They “shook the world around them,” one conquistador wrote, “with sudden dread.”6

There were so many people.

Then they began to die. The consensus is that the population was cut by between 85 to 95 percent within a century and a half. The Spanish Conquest, driven forward at a relentless pace by the consolidating Kingdom of Castile, inaugurated what the demographers Alexander Koch, Chris Brierley, Mark Maslin, and Simon Lewis call history’s “largest human mortality event in proportion to the global population,” a drop of upwards of fifty-six million people by 1600. “The greatest genocide in human history,” wrote Tzvetan Todorov in the 1980s.7

The first wave of death was brought by Conquistador terror.

Bartolomé de las Casas’s transformation into a critic of the Conquest didn’t happen until after the Conquest had made him rich. As a young boy growing up in Seville—he was born in 1484—Bartolomé had witnessed the glory heaped on Columbus upon his return from his first cross-Atlantic voyage and heard the stories of islands filled with gold, spices, and potential slaves. His merchant father, Pedro, and uncles Francisco and Juan were part of Columbus’s crew, and Pedro used the wealth he acquired from sailing to pay for his son’s education. Bartolomé became a “good Latinist” and began studying to become a priest. When Las Casas first landed in Hispaniola (today divided by Haiti in the west and the Dominican Republic in the east), his head was al-

ready crowned with a friar’s tonsure. He worked with his father, who had given up sailing to settle on the island as a merchant. Las Casas continued his religious studies and, in 1507, traveled to Rome for his ordination.

He was gone for two years, returning to the Caribbean in 1509, and in his later writings was circumspect about his own service to the Conquest. He accompanied at least one incursion into Hispaniola’s western lands, provisioning troops with supplies but also perhaps lending a hand to put down Indians with sword and harquebus. Christopher Columbus’s son Diego Colón, Hispaniola’s governor, granted him an encomienda , or consignment of Indian laborers, on the north coast of the island in the Cibao Valley.8

The term encomienda refers to a kind of slavery, but indios encomendados, or commended Indians, weren’t considered private property, or chattel. Rather, they were formally something like wards, members of an existing village or community, who, in exchange for labor, were to receive instruction in Christian doctrine from their overlords, their guardian encomenderos. The encomienda was important, but it was just one of many coerced labor systems. There was out-and-out enslavement, of Native Americans and Africans; there were onerous tribute demands and a labor corvée called the repartimiento. The “Conquest brought about so many forms of Indian servitude,” wrote one historian in the early 1900s, “that it is very difficult to master the nature of them all, and to follow them into all their minute details.”9

Las Casas’s conversion was slow in coming, and can be dated to 1512, when he accompanied Captain Pánfilo de Narváez on an expedition to pacify Cuba. He went as a priest, and was horrified as the campaign turned into, as one historian writes, “an odyssey of pillage and plunder, of death and destruction.” Massacre followed massacre, until Narváez’s men arrived at the last unconquered village, Caonao. There, the soldiers were greeted at dawn by thousands of kneeling Indians, who bowed their heads as Narváez’s mounted men took their place in the plaza. The tension Las Casas sets up, as he later reflected on the day’s events, between motion and stillness is stunning. The Indians kneel quietly. The horses tower over them. All is quiet except for the shuffle of hooves, as the mounts shift the weight of their riders and their heavy armor. No provocation on the part of the town’s inhabitants interrupts the tense calm. Then, suddenly, a soldier unsheathes

his sword and starts slashing at those kneeling below him. The rest of Narváez’s men join in, killing men, women, children, the sick and the old. They use lances to disembowel victims.10

Narváez himself, Las Casas writes, sat calm amid the chaos “as if he were made of marble.”*

One villager, his intestines spilling out of his stomach, fell into Las Casas arms. The dichotomy in Las Casas’s narration is now birth and death, being and nothingness: Las Casas baptized the man and performed last rites in the same breath. After the slaughter was over and the killers had moved on, Las Casas stayed behind to tend to the injured. He cleaned bandages, cauterized wounds, and tried to find some rational explanation for the carnage. He couldn’t. The Spanish assault on Cuba, he said, was “a human disaster without precedent: the land, covered in bodies.”11

Still, though, he remained silent and accepted a second encomienda for his service on Narváez’s campaign. This one, on the southern coast of Cuba, was made up of inhabitants from the village of Canarreo, which sat on the banks of the Arimao River. Las Casas lived there as a merchant priest, in a large, comfortable house built by his Indians. He said Mass in a small chapel and became wealthy. He couldn’t, though, shake off the feeling that he was living in sin, violating the commandment not to steal.

Then, in preparation for a sermon to preach on Pentecostal Sunday in 1514, Las Casas, now thirty years old, came upon this sentence from Ecclesiastes: “To take a fellow-man’s livelihood is to kill him, to deprive a worker of his wages is to shed blood.” No scales fell from his eyes, no repulsion at witnessing babies being torn apart by dogs awakened his consciousness. Rather, he simply reflected quietly on these words from Ecclesiastes and then made a decision to change his life. He abandoned his encomiendas, gave away his riches, and began a life of mendicant poverty and humanist advocacy.

* How intentional was this imagery? Was it a critique of the kind of history statues teach, which glorifies warriors while rarely making mention of their victims? In the early 1900s, Washington’s National Mall was home to a statue of Pánfilo de Narváez, which faced a monument to another Indian killer, Andrew Jackson. The statues were placed next to each other in tribute to the role Narváez and Jackson played, at different historical moments, in conquering Florida.

Shortly after Las Casas’s conversion, a smallpox epidemic swept through Hispaniola, killing, within a few months, nearly a quarter of the island’s population. Settlers mounted more expeditions to capture more slaves from other Caribbean islands and from villages along Venezuela’s coast. Africans were now being brought in to replace disappearing Taino, to pan rivers, dig mines, herd cows, and cut cane. As the population dwindled, Spanish cruelty increased.

“So many massacres, so many burnings, so many bereavements, and, finally, such an ocean of evil,” wrote Las Casas. The priest’s denunciations of violence against the New World’s darker people perfected a polemical style based not on revelation or appeals to authority but the power of personal witness. More than a century before the French philosopher René Descartes would posit the thinking, self-aware man as the essence of the modern ego, Las Casas gave us the seeing man, mindful not only of his own existence but of the agony of others: “Y yo lo vi ” — I saw all this, I saw it with my own eyes.

“All the world knows,” Las Casas said.12

All the world knew largely because Las Casas had told them. Las Casas’s famous account of the Conquest, Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias ( A Brief History of the Destruction of the Indies), written in 1542 and first published in Seville a decade later, with the word destrucción a play on instrucción. Instruction being what Catholics were supposed to be providing the inhabitants of America. The book was quickly translated into English, French, German, Dutch, and Italian and widely distributed, especially throughout Protestant Europe. John Milton’s nephew published it as Tears of the Indians in Cromwellian London, one of at least thirty-seven editions printed in England between the late 1500s and the middle of the 1600s.13

Las Casas lived during the middle of one of the most violent periods of human history: a three-centuries-long crisis that roiled Europe and the Mediterranean world. Famines, pestilence, crusades, and war. Wars that lasted a hundred years, wars between Lutherans and Catholics and between Christians and Muslims, the siege of Constantinople, Mitteleuropa’s peasant rebellions, the lowland’s revolt against Spain, England’s conquest of Ireland. Combined, these upheavals turned “the whole of Europe into a bloodbath.” Mass murder of unarmed communities was commonplace. Unbelievers,

heretics, and infidels were burned at the stake, and mutilated body parts of the enemy were catapulted into besieged cities.14

Still, Las Casas maintained that what the Spanish were doing in the New World was worse.

Las Casas filled page after page with extreme colonial gore. Torture, mutilations, massacres. Spanish conquistadores raped women at will. They broiled captives alive and then fed their corpses to dogs. They chopped off the hands of Indians and then told them to deliver the “letter” (that is, the severed body part) to compatriots hiding in the mountains as a message to surrender or face worse. In Mexico, the Spanish wrapped native priests in straw and then burned them to death. “Boar-hounds” tore children apart. Conquistadores used their swords as spits to roast babies as their mothers watched. They tossed infants into rivers, laughing as they guessed how many times they would bob up for air before drowning.

“The Spanish came like starving wolves, tigers, and lions, and for four decades have done nothing other than commit outrages, slay, afflict, torment, and destroy,” Las Casas wrote.

A New World and a new kind of mass murder carried out with a new kind of animal cruelty: of a quality “never before seen,” said Las Casas, “nor heard of, nor read of.”

Las Casas denounced but couldn’t make sense of the creation of a slave system that provided food and wealth to the Spanish but also eliminated the labor needed to produce food and wealth. “Gold unlike fruit,” wrote Las Casas with the dark sarcasm that runs through his prose, “lies underground and does not grow on trees, and therefore is not easily picked.” Indians had to dig for it. And the Spanish forced them to dig until they died, faster than the priests could bury them.15

Clearly, not all infants were killed for sport by the Spanish or fed to their dogs to give them the taste for human flesh. Yet that such horrors did take place reveals an indifference, not just to life but to the reproduction of life. In Hispaniola, the Spanish put Taino men to mine gold and women to grow food. Segregated, and worked so hard for so long, the enslaved couldn’t reproduce.

Women who did carry pregnancies to term had no milk to keep newborns alive. Women forced abortions rather than bring children into a world that had gone so horrifyingly wrong. “They will not rear children,” the early chronicler of the Conquest Pietro Martire wrote. European travelers to Hispaniola in the 1500s produced a series of drawings and engravings depicting the many techniques Indians would use to kill their children and themselves, which included hanging, clubbing to death, throwing oneself or one’s children from cliffs or into rivers, rather than accept the Conquest. The toxic juice of manioc and the poisonous smoke of herbs were other methods. The killings and suicides were often committed collectively, a last act of mournful solidarity.16

By the time the Spanish moved into Mexico and the Andes, most of the population of the greater Caribbean was gone and the islands were turned into what Las Casas called deserts, suggesting that the land was once populated but had been emptied, or deserted. There were more cows than people on Hispaniola, brought across the Atlantic from Europe and Africa, large free-range herds that destroyed corn and squash lands, contributing to widespread hunger. In Mexico and South America, cattle would likewise facilitate the elimination of Native Americans and the establishment of sprawling Spanish haciendas.17

The second wave of death was brought by microbes, which launched epidemics that lashed again and again the peoples of the Caribbean, Mexico, and the Andes— already ravaged by war, wracked by drought, and compelled to labor beyond capacity. The worst was a hemorrhagic fever with multiple, cascading symptoms, which Mexicans called cocoliztli, the Nahuatl word for pestilence. Spanish and Aztec doctors couldn’t figure out the basis of the illness, which scientists now believe was caused by a salmonella bacterium brought from Europe. The century after the arrival of the Spanish saw at least thirteen serious outbreaks, the worst being in 1520, 1545, and 1576. The shepherding of survivors into concentrated reducciones, or pueblos, accelerated the rate of contagion.

Between fifteen and thirty million people lived in Mexico in early 1519, when Hernando Cortés and his army of five hundred men arrived to begin his assault on the Aztec Empire. By 1600— eighty-one years, the length of a long life— only about two million remained.18

In 1493, with Spain barely a presence in Hispaniola much less the greater Caribbean, the pope announced a “donation” that gave King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella all the New World’s “islands and mainlands,” both those discovered and those yet to be discovered. The king of Portugal, himself presiding over an ambitious, seafaring empire, objected. A round of diplomacy between the two Iberian monarchies led, a year later, to the Treaty of Tordesillas. The treaty, with the Vatican’s approval, drew a line on a map of the world running north and south. Lisbon got what was east of the line, including much of what today is Brazil. Spain took most of the rest of the hemisphere. The split focused Spain’s expansionist energies on the Americas, and eventually the Philippines in the Pacific, while pointing Lisbon south, toward the coast of Africa, where Portugal would dominate the slave trade. The settlement was to “continue in force and remain firm, stable, valid forever and ever.”

France, equally Catholic and equally imperially ambitious, wasn’t happy to be cut out of the spoils. When Spain demanded the return of half a ton of gold, six hundred pounds of pearls, and three jaguars delivered to Paris by an Italian privateer, King Francis I of France told his Spanish counterpart that he’d like to “see the clause in Adam’s will that excludes me from a share

in the world.”* The sun shines as much on France, Francis said, as it does on Spain.1

Others, too, wanted their part, including soon-to-be-Protestant England, the Dutch, and the bankers of Germany. No European power, apart from Spain and Portugal, accepted the legitimacy of Tordesillas’s boundary line, its nonsensical nature made obvious as navigators started circling the globe. Once it became clear that one could wind up east of the line by sailing west, it was impossible to say where Spain’s Vatican-granted sovereignty ended and Portugal’s began.

A New World and a new kind of mass murder carried out with a new kind of animal cruelty needed a new morality.2

The fast transformation of what we now call Spain from the Iberian Peninsula’s multilingual and fractious Catholic fiefdoms into an empire larger than anything Caesar could have dreamt of raised questions— questions

* France had success colonizing large parts of North America and the Caribbean but failed to make significant inroads in South America. In the 1550s, France did sponsor a colony on an island off the coast of Brazil. The enterprise was utopian, comprised of an ecumenical mix of Catholics and Calvinists. The Calvinists meant to proselytize. But little missionary work took place, for their unyielding, punitive doctrine of predestination, in which people were already either damned or chosen, made it hard to know what to do with the local Tupinambá, who anyway didn’t seem interested in learning about Christ. For their part, the French Catholics had little but disdain for the natives, whom they described as lacking in “courtesy and humanity.” Later, Claude Lévi- Strauss would write about the episode: “What a film it would make! A handful of Frenchmen, isolated on an unknown continent— an unknown planet could hardly have been stranger—where Nature and mankind were alike unfamiliar to them.” Having given up trying to preach to the Tupinambá, the Catholics and Calvinists “soon began to try to convert one another.” Where they should have been working to keep themselves alive, they spent week after week debating ritual and theology: How should one interpret the Last Supper? Should water be mixed with wine for the Consecration? What was the nature of the Eucharist? Here, the New World staged a ludicrous solipsism, with Christians too busy rehearsing schismatic arguments to notice the Native Americans dying from the diseases they carried from Europe. Instead, they taught salty phrases to local parrots. The colony eventually collapsed, overrun by the Portuguese, and the survivors returned to France with their parrots.

that couldn’t be easily answered by jurists and priests born into a world they were told was all, only to learn it was but a part. There existed no law in the medieval Catholic canon capable of processing the enormity, territorially and psychically, of the New World, much less one that could justify Spanish and Portuguese claims to its possession. Papal edicts and the Tordesillas treaty cited the old Roman doctrine of discovery, which held that merely to find heretofore unknown lands conferred sovereignty. “With each day that we drift our empire grows larger,” sighs Don Fernando de Guzmán, in Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God , as his raft floats listlessly down the Amazon.

Spanish and Portuguese soldiers found it easy to pass through any bit of the vast Americas and claim it for their monarchs. More difficult was to establish control, not to mention the impossibility of keeping other European powers out. Spain claimed as its own most of the New World’s mainland and islands and declared not just the Caribbean but the Pacific to be “closed seas,” off-limits to the merchant ships of other European nations.

The main question, the one that would obsess Spanish theologians, philosophers, jurists, and clerics like Las Casas was this: By what right did Spain wage cruel war on the New World’s inhabitants? The reasons Spain gave for driving Islam off the Iberian Peninsula provided no helpful answers. That long struggle, starting in 718 and ending in 1492, was valid on the grounds that Iberia, before the arrival of Islam, had been populated by Christian Visigoths. So, Catholic war against Al-Andalus was, legally, not a conquest but a re conquest of lost Christian territory: La Reconquista . The fact that Muslims lived in a world that knew of Christ and yet they still rejected him bolstered arguments that Spain’s fight against Islam was righteous, since waging war against infidels, in canon law, was just. Such arguments could not be made about the New World— that is, if it really was “new.”

Some scholars contested the premise that the Indies were heretofore unknown. A miner in Panama had reportedly found a coin minted with the name and profile of Caesar Augustus, which fueled the idea that the Romans had traded with the New World. If Rome had earlier “discovered” America, then the Spanish monarchs, understanding themselves heirs to

Caesar’s empire, could claim a right to rule. And if jus belli— the law of war— granted Rome the right to wage war and seize territory at will, then Spain, said defenders of the Conquest, had that right as well. Spanish bards wrote odes comparing the conquistadores to centurions. Painters depicted Spanish kings garlanded with Roman laurels and decked out in Roman armor. Cortés, Mexico’s conqueror, was compared to many rulers, among them Caesar.3

Historical analogies could only go so far in one direction before crossing paths with analogies traveling the other way, opposing the Conquest. Las Casas was especially adept at picking apart the myth that Spain was heir to Rome. He pointed out that since the Romans had brutally conquered Iberia centuries before Christ was born, a more precise analogy would equate Native Americans with the Spanish. Both were victims of imperial tyranny.

Some theologians placed the curse of Ham on the heads of New World peoples, linking the Amazon to Africa, and the New World’s peoples to Ethiopians. The Jesuits said they found Saint Thomas’s footprints on a rock in Bahia, and others believed that Saint Bartholomew, after preaching in India, had traveled to the Indies. “God sent the Holy Apostles to all parts of the world,” said the Dominican friar Diego Durán in his Historia de las Indias de Nueva España , and, anyway, if Indians were God’s children, as many insist, then God would not have “left them without a preacher of the Gospel.” The point being that the New World’s people did “know” Christ and must have, at some point, rejected him, making them infidels and legally conquerable.4

Also popular was the idea that the peoples of the New World were descendants of the lost tribes of Israelites. Or, perhaps, of Jewish exiles from Rome, evidence of which was the finely wrought golden jewelry found in the Yucatán. “We can almost positively affirm,” wrote Father Durán, that Mexicans “are Jews and Hebrews.” Almost positively. Fernando de Montesinos spent years in Peru producing five dense manuscript volumes reading New World history through the book of Revelation, arguing, among other things, that the Andes were the site of King Solomon’s fabled mines. The Spanish destruction of the Inka Empire, then, wasn’t so much a conquest as a rediscovery and reestablishment of Israel of old. Since, according to

Christian esoterica, a new Jerusalem had to be raised and Jews converted to Christ before the Apocalypse could begin, the Conquest was a necessary step in the fulfillment of prophecy, and thus legal.5

Clashing analogies and end-time theology aside, most influential theologians accepted, or soon did, the fact that the New World was new. Las Casas reported that the people of Seville poured out to see Columbus upon his return from his first voyage across the Atlantic, for news had already come that he had “discovered another world.” He was the first, Las Casas writes, to “open the gates of the Ocean Sea.” Francisco López de Gómara, among Spain’s most influential chroniclers, would write to the Holy Roman Emperor to say that the Conquest was “the greatest event since creation of the world” except for “the crucifixion of he who created the world.” History’s Trinity was complete: Creation, Christ’s Crucifixion, Conquest.6

We might speak of “two worlds,” old and new, as the Peruvian Garcilaso de la Vega, the illegitimate son of a Spanish conqueror and Inka noblewoman, would say later, but “there is only one world.” And one world required—for the unifying Catholic kingdoms of Castile and Aragon (the core of an aborning empire that claimed to represent universal Christian history)— one law. By the 1500s, Catholic theologians had mashed together Roman doctrine, the writings of ancient philosophers, the teaching of the saints, including Thomas Aquinas and Augustine, and papal and royal edicts to create a legal system that had evolved over the centuries. Yet suddenly Spain was in possession, or claimed to be, of an incalculably large land mass, home to an “infinity” of souls who had lived for untold centuries beyond the horizon of Catholic authority. Their existence revealed canon law to be provincial, its claim to universalism a sham.

Who were these people living, thriving even, outside the Catholic realm? Where did they come from? Were they sons and daughters of Adam and Eve? Did they descend from one of the eight people who came off Noah’s ark after God’s Great Flood? If so, how were they separated from the rest of

humanity? If they weren’t children of Adam and Eve, did they carry the burden of original sin?

Three kinds of people could be legitimately enslaved according to existing Catholic doctrine. One: infidels or idolators. Two: prisoners taken in a just war. Three: a whole class of people understood as “natural slaves.” This last grouping was a category derived from Aristotle, as Catholic theologians interpreted the Greek philosopher, made up of beings closer to beasts than humans, lacking reason and incapable of forming political communities. In Seville, Salamanca, and other Spanish centers of learning, theologians and philosophers debated whether any of these categories could be applied to the people of the New World. Meanwhile, back in the Caribbean, far from Spain’s debating halls, conquerors and colonists didn’t wait for Aristotelian authorization. Columbus happily admitted, in a 1493 letter to Spain, that “in these islands I have so far found no human monstrosities, as many expected, but on the contrary the whole population is very well formed.” Yet he still captured hundreds of Taino and sent them back to Spain to distribute as slave booty to his loyalists and to pay off his debts, while the men who stayed on the islands took thousands of Indians as their slaves.7

Father Juan José de la Cruz y Moya, who later ministered in Mexico, described a sharp-edged rank-and-file racism that took hold during the Conquest’s early days, a conviction that the “first Americans” were created without a touch of divinity but rather emerged from “the putrefaction of the earth.” According to Father de la Cruz, many believed that “ indios americanos weren’t true men with rational souls but rather a monstrous third species of animal, falling between man and monkey and created by God to serve humans.” Settlers spread the lie that “Indians weren’t true humans but savages,” that “there was no more sin in killing them than in killing a field animal.”* Father de la Cruz condemned such ideas as heresy. The only thing “monstrous” about the New World was “the cruelty and greed that the bastard Spanish brought to this land.”8

* Bartolomé de las Casas spent the second half of his life arguing against the idea that Indians weren’t human. But oh, he said, how he “wished to God the Spanish did treat Indians like they treat their beasts. If they did, there wouldn’t be so many corpses, so much death.”

Conquistadores encountered fierce resistance in some places. In response, supporters of the Conquest came to loathe Indians as perverse, as the Devil’s barbarous minions, “destitute of all humanity.” Satan was angry that he was losing the New World, went one popular explanation for Indian opposition to Spanish rule, so he “drew a line” across which it was difficult to teach “Catholic truths.” The earliest chronicles of the Conquest describe lands inhabited by rebellious Indians—in northern Mexico, southern Chile, or the Amazonian slopes of the Andes— as populated by monsters and giants, proof of which were the enormous bones that the Spanish said they found, including a skull big enough to bake bread in. Grotesquerie created the impression of wickedness, cutting against Christian hope that the New World was a land of innocence. Columbus was wrong. There were monsters. And monsters could naturally be enslaved.9

The New World was big, its rivers broad, jungles dense, deserts unfathomable. How could there not be giants? Red-haired, one-eyed, and humpbacked, Spanish chroniclers reported all kinds. Amerigo Vespucci saw them himself. They chased him off Curaçao for trying to kidnap two women to give as gifts to King Ferdinand. One account sounds like the inspiration for Roald Dahl’s The BFG: eight leagues from Guadalajara there lived twenty-seven “lazy and gluttonous” giants, thirty-five feet high, whose hideous voices echo for miles. They carried clubs and supped every night on “four grilled children.”10

When Bartolomé de las Casas’s father, Pedro, returned to Spain from one of Columbus’s voyages, he brought with him a young Taino slave named, in Spanish at least, Juanico, whom he presented to his son as a gift. Bartolomé kept Juanico as a companion while he studied to enter the priesthood. Queen Isabella, though, abrogated Columbus’s authority to hand out the New World’s inhabitants. “By what right,” she asked in 1495, “does the Admiral give my vassals to anyone?” The queen ordered the return of Juanico and hundreds of other enslaved Taino to Hispaniola and nixed Columbus’s plan to set Hispaniola up as a slave export port: “Until we know whether we can sell them or not.”11

“Until we know whether we can sell them or not.” In Isabella’s doubt was

a universe of political theory, encompassing all the questions related to seizing the New World, with all its new people, by force. When it came to the status of Amerindians, the taking of their land, their reduction to forced labor, and their subjugation to the Spanish Crown, the royal court decided, undecided, reconsidered, and then decided something else.

Eventually, in 1503, a learned commission answered the queen’s query, sort of: No. The people of the New World could not be sold. Indians hadn’t had a chance to reject Christ, so they weren’t infidels. And they were clearly fully human, in possession of rational minds and divine souls. They couldn’t be enslaved— unless, that its, they were captured in a “just war.”

The debate over the justness of the entirety of the uppercase Conquest would go on for decades. In the meantime, Spanish settlers took it for granted that all the lesser campaigns, the backwater massacres and dawn raids, were justified, especially if the immediate cause of any given skirmish could be blamed on indigenous incitement. Captives taken in these campaigns could be enslaved.

This was around the time Las Casas first sailed to Hispaniola. He went on a ship that was part of a large fleet carrying thousands of Spanish settlers, administrators, priests, and would-be conquerors (including Francisco Pizarro, who, along with his brothers Hernando, Juan, and Gonzalo, would go on to defeat the Inka Empire and rule the Pacific side of the northern Andes). As the armada approached the island, a messenger came aboard the lead vessel to report that Spanish troops had just pacified a large rebellious village. The news flew from ship to ship, and cheers went up among Las Casas’s fellow settlers, happy that a fresh supply of “prisoners of a just war” would be available for them to enslave.

Shortly after Las Casas’s arrival, Isabella granted permission to the Spanish governor of Hispaniola to capture and enslave the refugee survivors of a Spanish massacre of over seven hundred residents in the town of Xaragua, or Jaragua. The slaughter was deemed “just” because the town’s residents had fought back. Indians who fled in canoes to the island of El Guanabo were hunted down. Captured, some were shipped across the Atlantic and sold in Castile, while others were put into service on the island.

“One was given to me,” Las Casas later wrote.12

On December 21, 1511, the Dominican priest Antonio de Montesinos— eight years before Cortés’s drive into Mexico, six before Luther nailed his theses to the door of Wittenberg’s church — walked to the pulpit of Hispaniola’s thatched cathedral and told the island’s notable Spanish residents, among them Columbus’s son, Governor Diego Colón, that they were damned. Expect perdition, he said, for turning Hispaniola and its surrounding islands into death camps. Montesinos called his sermon “Ego Vox Clamantis in Deserto”: I am the voice crying in the desert, or, as it is usually translated, wilderness. The priest meant the phrase not as a metaphor for New World nature but rather for the wasteland of Spanish morality.

The Dominican offered hellfire, though not the kind associated with later Puritan jeremiads. In those New England sermons, many preached in the middle of a long North Atlantic winter, English settlers focused obsessively on individual sins, which helped them make sense of the hardships they faced. Diseases, droughts, storms, wars, malformed fetuses, crop failures, massacres, and financial troubles were all understood as proof of God’s displeasure. The solipsism was intense. Indigenous peoples played only bit parts in the stories Puritans told of themselves, important only to the degree they provided clues to help decipher God’s judgment. Except for a few moralists, Indians remained shadow dancers, flickering around the fringes of the Puritan imagination.

Not so for Hispaniola’s Dominicans. Indians weren’t hidden in the wings of Spanish Catholicism, offstage as plot devices to keep the story of the pilgrims’ progress moving forward. For Montesinos, Indians were the main thing, central to the great debate over the justness of dominion and possession, conquest and enslavement.

The sins Montesinos condemned weren’t spiritual failings. Today, we would call them social and structural violence. What Montesinos and Las Casas described as “slavery” was in fact a dizzying array of mechanisms that wrenched labor and tribute out of Indians.

The encomienda was just one such institution, with encomenderos living like lords, forcing their Indians to dig faster for gold, plant more land for food, cut more cane, shovel more salt, dive deeper for pearls. “Hardly had the Indian pearl fishermen come out of the water with a supply of oysters,” Las Casas wrote, “when their masters forced them to dive again without allowing them time to recruit their strength and draw breath.” If they lingered too long on the surface, foremen would use the lash to force them back down. Spanish “greed was insatiable,” wrote one royal official, the work murderous. “Out of every hundred Indians who go” to work the gold fields, which often were far, far from their homes, “only seventy come back.” On their long marches, workers were forced to drink from stagnant jagüeyes, ponds filled with infested water, which led to more sickness, more death. Bodies were twisted, brains deprived of oxygen from deep dives, backs broken from their burdens.1

The Dominicans, including Montesinos, had landed in Santo Domingo, the capital port city of Hispaniola, in 1510, to establish their order and build a monastery. The first large consignment of hundreds of Africans as slaves had come that year, as epidemics, famine, and labor demands continued taking their toll on the island’s original residents. After a decade and a half of Spanish rule, what Columbus had called paradise was pandemonium, a scene that shocked the senses of the Dominicans upon their arrival and contributed

to the harshness of their condemnation. Montesinos was to deliver the verdict, but his sermon was collectively edited and approved by his fellow clerics, and their repudiation of settler rule was unanimous and total.2

Las Casas was there for the sermon, not as an ally of the Dominicans but as an accused, as an encomendero. “For a good while,” he later described the event, “Montesinos spoke in such pungent and terrible terms that it made the congregant’s flesh shudder.” Here’s his transcription of Montesinos’s sermon:

I am the voice of Christ in the desert of this island. Open your hearts and your senses, all of you, for this voice will speak new things harshly, and will be frightening. . . . This voice says that you are living in deadly sin for the atrocities you tyrannically impose on these innocent people. Tell me, what right have you to enslave them? What authority did you use to make war against them who lived at peace in their own lands, killing them cruelly with methods never before heard of? How can you oppress them and not care to feed or cure them, and work them to death to satisfy your greed? . . . Aren’t they men? Have they no rational soul? Aren’t you obliged to love them as you love yourselves? Don’t you understand? How can you live in such a lethargic dream?3

Montesinos then told the congregants that they were as certain to fall into the abyss as were the Turks. Their abuse of Amerindians was no less a sin than that of a pagan who had a chance to convert to Christ but refused. Disbelief among the congregants turned to anger, murmurs to indignation. Montesinos finished his lecture and left the pulpit with his head high and returned home to eat a lunch of cabbage soup. The Dominicans hoped the sermon would lead to settler reflection and contrition. But, as Las Casas dryly noted, the congregants didn’t spend the rest of the day quietly reading Thomas à Kempis’s De la imitación de Cristo y menosprecio del mundo. Kempis was a favorite of Catholic renunciants, a Dutch priest who wrote that property was slavery and true freedom could only be attended through a “disposal” of the self.

Rather, they marched to Governor Colón’s house to condemn the Do-

minicans and their “new and novel” doctrines. The crowd then moved on to the Dominican monastery to demand a retraction. Colón, who had joined the crowd, pleaded with the priests to consider the hardships he and his men had in conquering the island and “subjugating the pagans.” Montesinos’s sermon, he said, disrespected what they had achieved.

The friars tried to answer these concerns, yet they might as well have been speaking Taino. Their words, according to Las Casas, were morally unintelligible to the settlers. “Blessed are the ears that gladly receive the pulses of the Divine whisper,” Kempis had said. To understand, much less accept, Montesinos’s injunction would “mean that they couldn’t have their Indians, they couldn’t terrorize them.” Their “greed wouldn’t be satisfied, and all their sighs of desire would be denied.”

Montesinos, Las Casas, and other Catholic critics of settler abuse are often called “reformist,” in that they sought to ameliorate the worst abuses of colonialism. They remained loyal to the monarchy and supported Spanish rule as a providential mission to spread Catholicism. Yet even limited reform— better wages and limits on work requirements—would have ended Spanish colonialism as it existed. Christopher Columbus himself, in the earliest days of Spain’s Atlantic expansion, was clear that work, especially coerced work, was what created colonial value: “The Indians of Hispaniola were and are the greatest wealth of the island, because they are the ones who dig, and harvest, and collect the bread and other supplies, and gather the gold from the mines, and do all the work of men and beasts alike.” Without them, the conqueror of Peru, Francisco Pizarro, later wrote in reference to Indian laborers, “this kingdom is naught.”4

Colonial settlement— the planting of fields, the mining of minerals, the moving of rocks, the chiseling of stone, the building of houses—required enormous toil. The Spanish wouldn’t do the work. “There are no Spaniards here who will work for anyone,” one priest wrote the Crown. Instead, they grafted themselves onto island life— onto either Indian communities that already existed or new ones created by concentrating rebels and refugees into controllable villages— and then forced their inhabitants to do the work needed to extend the realm. They didn’t care what the system was called.

The words encomienda and esclavitud were often used interchangeably. Spanish colonists weren’t committed to a particular definition of “slavery,” or much concerned with what Church law had to say about it unless such law threatened their control over labor. Call Indians “free” if you want, say they are the queen’s vassals and even God’s children. As long as they did the work.5

“God is in heaven, the King is far away, and I rule here” was a popular settler expression. What mattered was that no third party—not Crown officials, not the Church, and especially not Montesinos and his fanatical Dominicans— stand between them and their Indians.

Eventually the crowd in front of the Dominican convent dispersed, believing they had secured a promise that Montesinos would retract his slanders in his next sermon. They misunderstood the pulse of the divine whisper. The following Sunday, Montesinos walked to the pulpit, his head again high. This time, he began his remarks with a quotation from Job: “Repetam scientiam meam á principio, et sermones meos sine mendatio esse probabo.”

“I will start from the beginning and will prove my sermon is correct.”

Many of the lawyers and theologians who surrounded the Crown during the first decades of the 1500s were war-hardened traditionalists, having come of age during the final, triumphal years of the Reconquest. They supported the Conquest and sought to validate it within the terms of existing canon law. The solution they came up with to criticisms like those preached by Montesinos was to require conquistadores to read out loud a treatise, either in Latin or Spanish, “to those not yet subject to our lord the king” before launching an attack.

In 1513, two years after Montesinos’s sermon, Juan López de Palacios Rubios, a Castilian expert on canon law, drafted what became known as el Requerimiento. The Requirement— or the Demand— crams five thousand years of Catholic world history into one very long paragraph. The document makes no mention of Christ but rather affirms that God, after making

heaven and earth, anointed Saint Peter the first pope, “lord and superior of all the men in the world.” The text then relates how one of Peter’s papal heirs “donated” the islands and mainland of the New World to the Spanish monarchy. The person reading aloud the thousand-word document, usually a scribe or a notary, finished by saying that there existed papers, such as the Treaty of Tordesillas, proving the truths just narrated. They could be, if the listeners so wished, made available for review: “You can see them if you so desire.”6

The Requirement is easy to mock as the last gasp of a dying worldview. A close look at its text, though, reveals a stealth modernist sensibility, one that, even as it insists on the singular authority of the Catholic Church, accepts the necessity of recognizing and living with pluralism.

El Requerimiento upheld the unity of creation, of “one man and one woman from whom we and you and all the men of the world were and are descendants.” The phrase we and you and all was meant to include the inhabitants of the New World as descendants of Adam and Eve. Then, after having affirmed the common origin of humanity, the manifesto went on to explain its fracturing and dispersal across the globe as resulting from the “multitude” that issued forth from Adam and Eve: “It was necessary that some men should go one way and some another, and that they should be divided into many kingdoms and provinces, for in one alone they could not be sustained.” Diversity was necessary, since the earth, though bountiful, couldn’t support a surging population in a single religious community. Palacios described a world comprised of major religious differences yet integrated by politics, placing Christians alongside, not above, Muslims, Jews, Gentiles, and “other sects.” The “requirement,” or “demand,” was not that the people of the New World convert. The document expressly says that faith is a free decision. Conquistadores wouldn’t compel anyone to become Christians. All that was required was that the audience recognize Spanish monarchs as their sovereigns.

The script’s nuance, however, mattered little. What mattered was its performance, its offering of a choice that wasn’t a choice at all. To accept Spain’s rule would bring many “benefits,” including, so the text said, freedom from servitude. To refuse, the text explained, would visit utter destruction:

With the aid of God, we will enter your land against you with force and will make war in every place and by every means we can and are able, and we will then subject you to the yoke and authority of the Church and Their Highnesses. We will take you and your wives and children and make them slaves, and as such we will sell them, and will dispose of you and them as Their Highnesses order. And we will take your property and will do to you all the harm and evil we can.

The text of the Requirement cut against the idea, popular among settlers, that Indians were a race apart, perhaps not even human. But the violence it sanctioned confirmed the notion that the New World peoples were lesser beings.