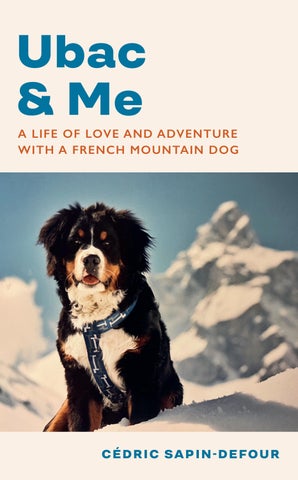

Ubac & Me

A LIFE OF LOVE AND ADVENTURE

WITH A FRENCH MOUNTAIN DOG

translated by Adriana Hunter

Harvill Secker, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by Harvill Secker in 2025

First published in French under the title Son odeur après la pluie by Éditions Stock in 2023

Copyright © Éditions Stock 2023

Translation copyright © Adriana Hunter 2025

Cédric Sapin-Defour has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 12.4/17pt Calluna by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

i SB n 9781787304833

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To the ‘Lady of the Rio Bianco’ whose leaps and falls structure my every day

A receptivity to happiness or something like that. What else could explain the unexpected?

Chance meetings destined to make our lives a better place sometimes happen on dreary days, just like that, with no fair warning. We’re improvising our way through the ordinariness of a dull pallid day, anticipating nothing beyond a tomorrow, only too aware of the world’s shortcomings and too unaware of our own enviable circumstances, and then a stroke of good luck dictates that it’s our turn, a peculiar pendulum swing connecting the impact of an event and the improbability of it actually happening.

The walkways in shopping malls are not very elegant places, and the ones in Sallanches are no exception. First, we’re clobbered over the head: a low ceiling of grey squares as if the sky doesn’t exist and we don’t even particularly miss it. Then we’re operated on, white light everywhere, stark as a cranial drill, piercing at first but eventually we don’t feel a thing. Lastly, noise, lots

of it, our era can’t deal with silence. Someone – who’s nowhere to be seen – shrieks out recipes for a better life, the same recipes for all of us; you can wander off, hide wherever you like, they’ll find you. Every ten paces, things flash. All the people here are used to it, and I’m one of them. These are places where humanity has relinquished all aspirations to grace, including one of its most steadfast guises: restraint. Places that have no real soul . . . but where mine will be intensified for ever.

The bar is called the Penalty; it could have been the Corner. On its lettuce- green windows is a goal, a tall, slightly balding dark-haired man in blue, perhaps Zidane, and footballs painted on in Tipp-Ex. You can have a hundred different drinks here, place three-way bets, play the lotto and buy tobacco products; it offers a wealth of addictions and there’s nothing to stop you indulging several simultaneously. You’re served charcoal-black coffee that the French claim is exquisite, and a chocolate- covered peanut in an individual plastic wrapper. At the bar, voices are raised, discussing suspect geopolitics; finding a single culprit to explain everything seems to make life more comfortable.

I reach for a newspaper. When trying to disguise the fact that we’re alone in a public place, we alight on the first available knick-knack and pretend to have a full life. In 2003, France still had flimsy newspapers full of local ads and named after the regional département, in this instance the 74 . In the corners of the

pages, previous readers have scribbled drawings that made sense to them alone and must have made them feel better in some way. These few scant pages discuss everything, and basically nothing. I escape into them, which gives an idea of my ambitions for the day. Some of the ads spill beyond Haute-Savoie, venturing further afield.

I read with no real aim, skipping many entries, drifting from the sublime to the ridiculous without intentionally seeking feel-good items. And then he leaps out at me. Page 6, top left-hand corner, under a small spot of water that makes the words leaky, very near a second-hand Peugeot J5, full MOT , price negotiable; and Marc, also pre-owned, looking for an adventurous YM for negotiable activities. Page 6, then; clapped-out machinery, eager men, and him – sitting there, patiently motionless, deaf to all the bustle, already placid.

A dog. One of twelve, all more or less the same, save the order in which they came into this world on 4 October 2003, this world where everything begins with a birth; first appearances are a different matter. Twelve Bernese Mountain Dogs; their poor mother, a heatwave summer, twelve: six M and six F. Twelve in one go, now that’s what you call a litter and, in builder’s terms, the maximum load. I order a second coffee. Up at the bar, a pink woman is clutching a sort of Pekinese, and I still don’t know if the thing can walk.

Thinking I can get away from the noise, I leave the

bar for the central aisle, but all that changes is the topic. Facing me is a poster full of white sand, a freakish blue, a sun-baked young woman running with all her teeth on display. The wording goes: ‘Stop dreaming your life, live your dreams’ – people will monetise anything. I’m not sure why – oh, really? – but I dial the number at the bottom of the ad. A call, an urge, a feeling of push and pull, and pushback too. We think we have sudden impulses, but they’ve germinated quietly for so many years, they know us so well that as soon as they’re given some fresh air, they emerge, disguised as a spur-of-themoment decision or a truth imported from elsewhere.

Madame Château, that’s her name, replies with the promptness of someone who knows why the phone’s ringing. She tells me the puppies are all still available except for one but I can be sure they’ll go quickly. This annoys me slightly. I don’t want to be rushed – I’ve had enough of this constant incitement to act swiftly – not at this stage, when the whole point is to savour the moment. But actually this tiny moment is of my own making – it can fill whatever hole it likes in my life, and at its own sweet pace. I tell her that, at just a month old and barely able to walk, they’re a bit young to be going anywhere quickly, one of those clumsy offerings produced by the socially awkward who use humour to protect themselves from reality, or so they think. She responds with silent indifference

as acknowledgement – if any were needed – of my superfluous remark. But I think I understand her, she’s playing her part to perfection: the time has come for her to monetise the nights spent watching over a bitch in pup, the duty vet’s number in her head, known by heart; the day has come to capitalise on the tender feelings we humans have for dogs. People can shamelessly trade in love, it’s quite easy even, because the commodity is so priceless.

I tell her I might drop by over the weekend just to see, if that’s convenient for her. What a joker that word is, might ; I like to think it’s emphatically conditional, but it was stating the indicative with all its might. Just to see didn’t pop up out of nowhere either, it was almost like the I’ll see your . . . whacked across a poker table when someone begs fate, pretty please, to tilt in their favour.

I hang up and return to my wobbly pedestal table in grey faux marble, somewhere you’d want to see Sartre and Platini having a chat. A giddy feeling is waiting for me there, the sort perfectly cooked up by opposing forces of enthusiasm and stumbling blocks. I know what heading off towards Mâcon will mean. It won’t be just a visit. Not a question of finding more elements to consider. Not a delaying tactic. It’s provocation. Making two living beings meet and bringing their life stories together for thousands of days. You can’t lie to budding love. If my white van heads in that direction, it won’t

be to have a quick look- see unless it’s to have a look and see a reality already filled with happiness and shortcomings. And I alone will be responsible; as far as I know, neither she nor he made any sort of request.

I’ve already ‘had’ a dog. Ïko, a wonderful companion, a Labrador beige of body and darker of ear. His previous owners (that’s how some people see their connection with these sentient beings – there’s master too, but what to make of that?) had called him Ivory and then spinelessly abandoned him. He’d just been a trinket like his name, something prized, acquired by force, exhibited and then wearied of. One April morning I went to the animal shelter in Brignais and vacated a cage; a hundred others remained occupied. He was so not ivory that he didn’t suit that gentle name. Ïko was a better match.

That was the start of a luminous relationship whose end I didn’t think to imagine, a relationship in water, snow and forests, by the fireside, that flourished alongside life, an absolute joy that was well-balanced but not long- lived; one day, not that he made a fuss, his jaw became swollen with blood. I took my parents’ car, the big one, the reliable one, and drove to the veterinary college in Maisons-Alfort, the only place that could do a scan – an investigative tool that’s essential or indecent depending on the place you allocate to animals in your view of a useful world. The vet told me Ïko had only a few months left to live – dogs imitate humans even

down to being riddled with cancer. What happened next proved her horribly right; vets, and this is their failing, are rarely wrong.

On the way home, sadness gripped me by the neck and I cried for four hours straight on the A6 until my body ran dry. It’s good to cry, my grandmother used to say, tears kept inside do far more harm and rot your bones. Ïko was asleep on the rear seat and I convinced myself he hadn’t understood a thing, that dogs had no idea of their own mortality; with animals we swear by their clairvoyance or their ignorance, it’s contingent on what will protect our own feelings.

One morning, after a thousand selfish postponements, love won the day over affection. I had to pick up the phone to make an appointment that would steal away one life and puncture another with the same needle, going to the vet together and leaving alone, robbed, with a collar and a handful of hairs as my only talismans. In a few centilitres from a syringe, the future’s wiped out with nothing in exchange. I think Ïko was happy on our earth, we had so many plans to fulfil, and yet we knew that it’s never better to wait till later.

His absence has been with me every day since, and it doesn’t feel completely right to me that life still goes on. Which is why I know. The emotional undertaking involved. I’ve already cried with a name tag in the crook of my hand. Getting a dog means accommodating an

imperishable love, you’re never separated from it, life takes care of that, any weakening of it is illusory and its end unbearable. Getting a dog means catching hold of a creature who’s only passing through, committing to a full life that’s bound to be happy, inevitably sad, and in no way sparing. There are no mysteries about the end result of this union, and we can succumb to denial or undertake only to imagine it, but in either instance, sadness lurks, bullying us in a peculiar dance, an everyday pitching and rolling, only for joy to gain the upper hand, eclipsing this inevitable fact.

Biology, the science of life, isn’t especially concerned with inter-species idylls. If your parental love is directed at your own species, the usual process of time means your young will survive you and you won’t have to ravage your own life with thoughts of the end of theirs. When you love a different category of living thing with a shorter lifespan, logic dictates that the day will come when the newborn catches up with your age, exceeds it and dies. So it’s perfectly illogical, it’s the ultimate and a far-from-pleasant paradox that a dog’s death goes against nature. The fact remains that this happiness has an expiry date, try as you might to spend each day slowing your dog’s life or speeding up your own, those are the facts, there’s no negotiating with chronobiology: dogs perish.

Lovers of the grey parrot have fully grasped this and spend less time dehydrating their corneas. Topstitching

your life with a dog’s presence means understanding that the happiness forges the sadness; it means gauging just how insoluble absence is in a sea of memories, however extensive and happy they may be; it means accepting that every minute be lived seven times more intensely than usual; it means banging your head against the seductive and vertiginous intention not to sabotage a single moment and to celebrate life with fervent intensity. For this reality and for the guts it takes to accept it, I deeply admire anyone who adopts a dog.

As I walk out of the Penalty, consumed by these thoughts, it strikes me that it’s high time I reintroduced a dash of this into my life: the courage it takes to love. I pop back in to buy one of those scratch card things; because my horoscope was lacklustre, it’s the only way I can think of to tip the day in my favour.

Outside the shopping centre it’s a beautiful day – who knew?

I call Madame Château back and she picks up just as quickly. Actually, I’ll come today, Saturday; after all, she’s as entitled to her Sunday rest as everyone else. Before starting up my van – a big dog won’t feel cramped within its sheet-metal walls – I look at the mountains. From where I’m parked, the Mont Blanc chain is resplendent, the craggy Rochers des Fiz intimidating, both of them an invitation to bold undertakings.

I let my mind wander but, afraid it will come over all practical, I gently suggest it goes and checks out the dreams department.

Then I pull myself together and employ all sorts of intellectual acrobatics to crack open the true purpose of this trip – a very unequal battle. I delve into rational thinking, which I’m usually scared of. I tell myself Saturday’s a terrible day for making important decisions which could affect the rest of your life. It’s a day full of economic and symbolic vulnerability. The week need only be slightly burdensome, and we want our rightful share of levity, our extra helping of it’s only fair, often more than is strictly necessary, to the point of extravagance.

I even venture into questions of national identity and the inglorious creeping tide of anti- immigrant sentiments. So a Bernese Mountain dog from Mâcon, now there’s a foreign imposture! I’ve been cradled in Alpine mythology since childhood, all St Bernards, Gaston Rébuffat and the unattainable edelweiss, so for me to visit the very icon of Berne’s cowherds in the modest undulations of the Saône-et-Loire region smacks of selling off your dreams and dishonouring your roots – a snow-decked Zermatt would have been a more glittering choice. And then back the pendulum swings: I convince myself it’s the exact opposite. If a little distance from Swiss German rigidity infiltrates proceedings . . . well, that won’t tarnish the eccentric

life this dog will be stepping into. The exchange rate of the Swiss franc and my predilection for confluences eventually win me over to the charms of Burgundy. How steerable life is.

I glance at the map. Confrançon. A40. D1079. It’s not as far as it seems. And who knows, within my reach.

Two hundred kilometres and I reach Confrançon, one of those scraps of France that couldn’t care less about the ‘empty diagonal’, a swathe of sparsely populated land that cuts across the country, places that are charming to drive through but soul- destroying if you had to put your name on a letterbox there. Some way outside the village, Madame Château’s home is reached along a winding little road whose turns serve no purpose other than to outline pretty fields of yellowgold who- knows-what; waiting under an oak tree at one solitary corner is a Citroën Dyane.

During the journey, I thought of myself as a connoisseur of fine books or grands crus stepping through the second-hand bookseller’s or wine merchant’s door, swearing he’ll leave empty-handed, convinced that just visiting these bazaars-of-promises will be enough to fill the void, but never actually succeeding. Lying to ourselves has the advantage of being amicably forgiven, so we pretend to believe that we may back down.

I haven’t called anyone to discuss the merits of this return trip and its blatant motive, too afraid of expressions of scepticism or, worse, of polite support. I like the fact that the beginning of this story is kept quiet, its outcome will all too soon be just another known fact for most people and, even though being single presents drawbacks to happiness, never having to canvass opinion from someone right next to you, never being subjected to joys or disappointments at such close quarters, is one of the strong points of singledom. I picture myself like Tintin, my only company an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other, furiously debating the definition of a life worth living; as I remember it, optimism always won the day. The same is true of life’s highpoints which recall the geographies of childhood, nostalgia for a time when dreams were valid currency, when they were self- evident, irrevocable, deaf to the warnings of tinpot prophets, of experts in difficult tomorrows, of the people we considered old. It’s only later, polished by life, that we consider constraints first.

I’ve had to stop several times along the way. I was gulping down the kilometres without seeing them, my head in the air, stuffed full of ‘after’. Only a wrong turn could drag me back to reality. What lies ahead is a first date, but it’s all the more heart-fluttering because the other heart in this relationship isn’t prepared for it and may not want it.

With all of life’s chicanes, weighing up what we’re prepared to lose and what we can expect to improve is a sanguine, worthwhile procedure. It’s good for the heart. The world of spoiled humans – which includes me – comprises two camps: those who tirelessly honour their status as living beings, terrified of shrivelling up and developing a constitutional fervour for confronting unpredictable times; and, at the other extreme, those who are content that nothing – absolutely nothing – out of the ordinary should happen to them, accumulating identical days they’ll never get back and asking nothing of life but to be visible and not be any bother if you don’t mind.

I struggle every hour of every day not to be like the second category, so much so it’s exhausting. Does that mean I should brandish this puppy as if loudly proclaiming a constant, urgent need to live? That would mean descending into the most acute madness, an obligation to be free; and claiming that my personal whims decide the fate of other living creatures; and loving less about him than about myself. Although plenty of people see getting a pet as an aesthetic choice, like haggling over the colour of a jacket, I personally feel I’m pawning just as much of myself so I’m whipped up to the point of nausea . . . and it feels good.

The house is a large L- shaped farm, the shorter side cutely renovated and covered in Giverny tiles, the

longer one in its original state with a roof of black sheet metal, dotted with occasional red, replete with memories and jumbled aspirations. The stone has reappeared on the walls of the short side; on the longer side the wattle and daub covering is standing its ground – the children want to change their parents’ house, the grandchildren to rediscover it.

There are dogs everywhere here. You needn’t go so far as loving them, but you can’t be afraid of animals to venture on to the premises; Madame Château is protected by gatekeepers. To access the property you drive between two stone pillars topped with lions’ heads but not connected by a gate; maybe someday they will be. There’s no fence to the left or the right of the pillars either – life is lived out in the open here, but there are clearly dreams of an estate.

Yes, dogs everywhere! Small ones, huge ones, the barkers, the welcoming, the sceptical, some in pens, most running free, not one of them tied up, and all making a tremendous noise. Dogs born here are lucky, the place exudes a feeling of movement, of blending and of pliable rules – it’s an immeasurable asset to be accustomed to freedom so early in life. I stop the van about halfway across the yard for fear of running over a member of the reception committee; as I turn off the ignition, I promise myself I won’t automatically idealise everything here in the moments to come. Then I reconsider: banish charm? How stupid. Several mutts are

jumping up at my door, I’d forgotten how little they care about aesthetics.

Stepping out of the van, I’ve barely put a foot to the ground before I’m assailed by a multicoloured pack, let’s see who’s first to decorate my pale trousers – a wonderfully appropriate sartorial choice – with a pawprint. They all converge on me, dogs have the gift of reminding us we’re alive. I look at them one by one, wondering who’s related to who, who’s a bit of a leader or an elder statesman, who has always been slightly reserved or shunned; I try not to neglect any of them. Some are barking, others copying them, the fact that I’m not afraid intrigues them.

Alerted by the choir, Madame Château emerges from the house, bringing a smell of cinnamon. She immediately calls an end to the effusive welcoming; and is heeded, promptly. All the dogs return to their inactivity except for one, a caramel-coloured sort of Chow Chow with deep-set eyes which has stayed at her feet, showing off a little, perhaps the only one that’s hers.

Madame Château is exactly as I imagined her from her voice, which is unusual – my predictions generally fail spectacularly. A dark-haired woman, fortyish, sprightly, the sophistications of a saleswoman halfobscuring a rural background, fists on her hips, head thrust forward. Her direct eye is characteristic of people who don’t need to make a performance of character. She shakes my hand firmly, already establishing her

importance. I was thinking of kissing her on the cheek. I’m wary of people who don’t look like what they are, you can tell soon enough, and this woman isn’t one of them. She radiates a sense of kindness devoid of naivety, gentleness without timidity, elegance stripped of all narcissism, which matters: she’s the very first human the puppies get to know and I like to believe in conclusive impressions. We exchange the usual courtesies, she about how easily I found the place and how long it took, while I’m all you’ve got a very quiet spot here and I won’t keep you long . . . but I get the feeling she’s not one for pointless words, so I try not to give her too many.

‘Let’s

go and see the littl’uns!’

I don’t know whether I should derive any satisfaction from the fact that a childish expression can raise my spirits as powerfully as two lines of Rimbaud would but that’s what happens, the heart is generous enough to welcome every sign that it is fated to happiness. I say ‘I’d be delighted’ or something equally old school.

We walk along one wing of the house. It’s now drizzling. At the far end of the neighbouring field a whole spectrum of colours appears, a favourable sign, all those beauties have agreed to meet here, but should I hold back? We all know that when we try to catch a rainbow, it moves away, becomes evasive and disappears.

We walk through various spaces, enclosures, informal areas that seem to act as territory for their

occupants. Wire fencing, but only just, less to separate than to protect, like multiple subdivisions in an improbable housing estate where no one’s frightened of the neighbours. There’s a strong smell of dog hair, I spot a poo here and there but nothing like the filth that some people let their dogs languish in. There are terriers, sort of poodles, border collies, retrievers, some that my search engine doesn’t recognise, a mosaic of dogs with distinct dimensions, shapes, coats and personalities . . . narrow questions of identity don’t seem appropriate.

The one thing they have in common is that they’re all Canis lupus familiaris, descended from the same grey wolf. Time has worked its miracles on whims of morphology and diverging character traits, conceiving small ones for exploring underground tunnels, hardy ones for pursuing game, ones with webbed feet to save the drowning, gentle ones to guide the blind, and ones with no other purpose than being part of the world, useless essentials. All ethnicities seem to cohabit blithely here. Why is it that we humans, all descended from the same ape, are so confusingly monomorphic that we perceive such a crucial and divisive distinction in the tiniest nuance of melanin? In the taxonomy stakes, we didn’t inherit the most indulgent spot. It must be so nice to live surrounded by a thousand visible singularities; we could then pursue something greater, be it in the name of humanity or following our star or another of those