TEST MATCH SPECIAL

HOW TO READ

CRICKET

Everything you need to know about the greatest game in the world

Everything you need to know about the greatest game in the world

Also available from BBC Books

Tall Tales: The Good, the Bad and the Hilarious from the Commentary Box

The Test Match Special Book of Cricket Quotes

The Test Match Special Quiz Book

The Wit and Wisdom of Test Match Special

50 Not Out: The Official History of a National Sporting Treasure

Everything you need to know about the greatest game in the world

By Ebony Rainford-Brent with Nick Constable

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

BBC Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by BBC Books in 2025 1

Copyright © Ebony Rainford-Brent 2025 Illustrations © Matthew Burne

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.5/15.5pt Dante MT Pro by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781785949500

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To the late Jenny Wostrack, whose unwavering support during the formative years of my cricket career was nothing short of inspirational. Jenny drove me across the country to trials, applied for scholarships on my behalf, taught me how to knock in my first bat and was there for me whenever I needed a guiding hand. Crucially, she made the game accessible and digestible, which is exactly what I’ve tried to do in this book. I hope I’ve channelled the energy Jenny brought into my life into helping others discover the game and grow to love it as much as I do.

I love the idea of demystifying cricket – spreading its unique joys among those who may perceive it as complex, even baffling. Its greatest attribute is that you can start playing in minutes, as anyone who has ever marked a crease in the sand for beach cricket knows. Get a ball, a lump of wood for a bat, a cardboard box for stumps and you’re good to go. Bowl the ball, hit the ball, go for a run and, as Shakespeare’s Henry V put it, ‘the game’s afoot’. The joy of cricket is that once you’ve got that basic understanding you can dive into the nuances of a sport that, uniquely in team competition, marries the headto-head struggle between two individuals (batter and bowler) with the wider tactical tussle involving 22 players.

How to Read Cricket is not a book overly concerned with the practical mechanics of the game. It’s not a coaching manual, although it mentions some of the basic skills required in batting, bowling and fielding. It’s not an assessment of cricket strategies, although we’ll consider how they change depending on which format of the game is being played. Neither is it a nerdy obsession with the Laws, although it’s important to grasp some essentials because this is where the action starts and ends. Above all, this book is a peek into cricket’s triumphs and failures, its customs and culture, controversies past and present, the brilliant and the bizarre and the extraordinary

players who make it all so much fun. The game belongs to keen amateurs on village greens every bit as much as international stars plying their trade at world-renowned venues, and I’ve tried to capture a snapshot of my own journey from knockabout street cricket to World Cup glory. The A–Z format is designed so that readers can dip in and out of key themes and talking points, and I’ve included personal anecdotes that I hope will grab both the cricket obsessive as well as the curious rookie. It’s the greatest game on Earth, and the next best thing to playing it is knowing how to read it. I hope this book will help you do exactly that.

Ebony Rainford-Brent

I never wanted to play a weird game like cricket. It was 1993, I was ten years old, growing up in Herne Hill, near Brixton in south London, in a single-parent household – my mum, Janet Rainford, three older brothers and me. There was absolutely no interest in cricket from any of us, even though Mum had a Jamaican background. Instead, we were obsessed with football. We all supported Liverpool, and I thought I was destined to be the new Robbie Fowler or John Barnes. Then one day this cricket coach turned up at my school, Jessop Primary. His name was Tony Moody and he worked for a charity called the London Community Cricket Association* set up following the 1981 Brixton Riots as a way of bringing the community – and particularly young people – together. In the early 1980s they were trying to entice more state-school kids into playing cricket and I recall my teacher taking me aside to ask if I wanted to give it a try. ‘Well, no’ was the simple answer to that. I’d seen cricket on TV. Everyone wore weird white clothes and they were forever stopping for lunch or tea or

* The LCCA is now called The Change Foundation and has expanded into other sports and the creative arts to provide opportunities for young people.

something. I just didn’t get it. But the teacher kept on at me: ‘You love football, you love sport, give it a go.’ And so I did. The moment is crystallised in my mind. We were in this caged playground at the school, and the coach was there. My teacher handed me a blue bat, they showed me an orange ball and said: ‘Just hit it.’ And I did. I walloped my first ball out of the playground into a park on the other side of the road, which happened to be quite near our house. Such a great feeling. You could hit the ball as hard as you wanted – that was apparently the whole idea. It may sound strange, but it was such a sense of freedom. I was hooked.

I signed up with Tony to attend his Saturday-morning sessions at Stockwell Park School, 50 boys and me. The gender imbalance didn’t worry me at all because I had spent my entire life dealing with brothers and I had no problem holding my own. We played a version of street cricket called bowl-to-bat. It was quite competitive – you might even say aggressive – because you had to win the ball as a fielder to get a go at bowling. Then you had to bowl out whoever was batting to get the chance to bat. It was everyone for themselves and I’d be charging around, elbowing fielders out of the way, pushing them, slide-tackling them, anything to get my hands on the ball. I had so many holes in my trousers and poor Mum was forever patching them up. But it was great fun and the kids all got on well. We were a multicultural community, lots of first-generation born Brits, all from different backgrounds, and many of us have stayed friends to this day. I have life-long friendships forged through playing Saturday street cricket for three hours at a time.

Tony was a great coach. He made the game simple, relatable and fun. He got us transitioning from the soft ball we used in street cricket to a hard cricket ball by getting us to stuff

the ball into an old sock and tie it up on a long piece of string attached to a tree branch or washing line. Then you grabbed a bat and practised your shots on it for hours. It was quite a common coaching strategy in those days because it was accessible for everyone. We were taught the hallowed technique of keeping a high elbow when executing a shot, and that’s still a sound approach even though batting styles and techniques have evolved greatly with the rise of the limited-overs game.

Stockwell Park coaching was a couple of quid a session, which was a lot of money in our house, but Mum could see the excitement and joy in me, she was proud and her response was: ‘if this means a lot to you, let’s do it’. She couldn’t have known what she was letting herself in for. Soon I was playing all over London and travel costs went through the roof. We’d be up half the night studying bus timetables and then have to get up for a 5am service that would connect with another bus that would get me somewhere near a ground somewhere in Surrey in time for a 9am start. It was exhausting before a ball had even been bowled. Mum accompanied me; she wouldn’t have me travelling around on my own.

My first organised match was a Kwik Cricket* tournament at Arundel Castle in West Sussex, one of the most beautiful grounds in the world, and Tony took us there. Because every team was required to field two girls I was a hot property. The event was a culture shock for two reasons: firstly because it meant I was going to travel outside London, a big thing in itself, and secondly because I’d never seen such an incredible castle. There was this amazing slope, which we all immediately ran up and rolled down. We didn’t win the competition

* Kwik Cricket is a fast and simple version of the game designed for children.

but we did quite well and I was spotted by a former Surrey Ladies player and coach called Jenny Wostrack who was way ahead of her time in trying to make the women’s game more accessible. Her uncle was the brilliant West Indian all-rounder Frank Worrell so there was obviously something in the genes. Jenny contacted my mum, saying: ‘Your daughter has got something. We need her to come and play for Surrey.’ From that moment she was my mentor. I was about 11 years old and so lucky that she found me. Mum had three jobs – NHS receptionist, night shift at Sainsbury’s, cleaning work here and there – and so she couldn’t always get me to matches. She also had three other kids to bring up. Jenny stepped into the breach and made sure I could always play. She taught me things as basic as knocking-in a bat* – as well as filling in grant applications and generally fighting battles on my behalf. If you’re going to succeed in any sport as a kid then you need people like Jenny and my mum to make it happen. I was playing for Junior Surrey aged 12 and that was the crossover point for me, the moment I decided I wanted to play cricket at the highest level.

I’d be lying if I said it was an easy decision because I loved all sport. During my teens I was selected for England Schools basketball and athletics squads (my events were the shot put and hurdles) and I played squash and football for London Schools. In football I was a striker – what’s the point otherwise? – and lived out that dream of being a female Robbie Fowler. If there was any manner of sports club on offer at school, whether it met before class, at lunch or after class, I’d be there. Mum took the view that as long as I kept up my

* The process of knitting together fibres on the front of a bat’s surface by hitting it with a wooden mallet. This hardens and protects it ahead of first use. Many bats are now knocked in at the manufacturing stage.

Story

grades I could do whatever sport I wanted. Gradually, though, cricket became the dominant force in my life. Once I realised there was a chance of playing professionally it became my sole focus.

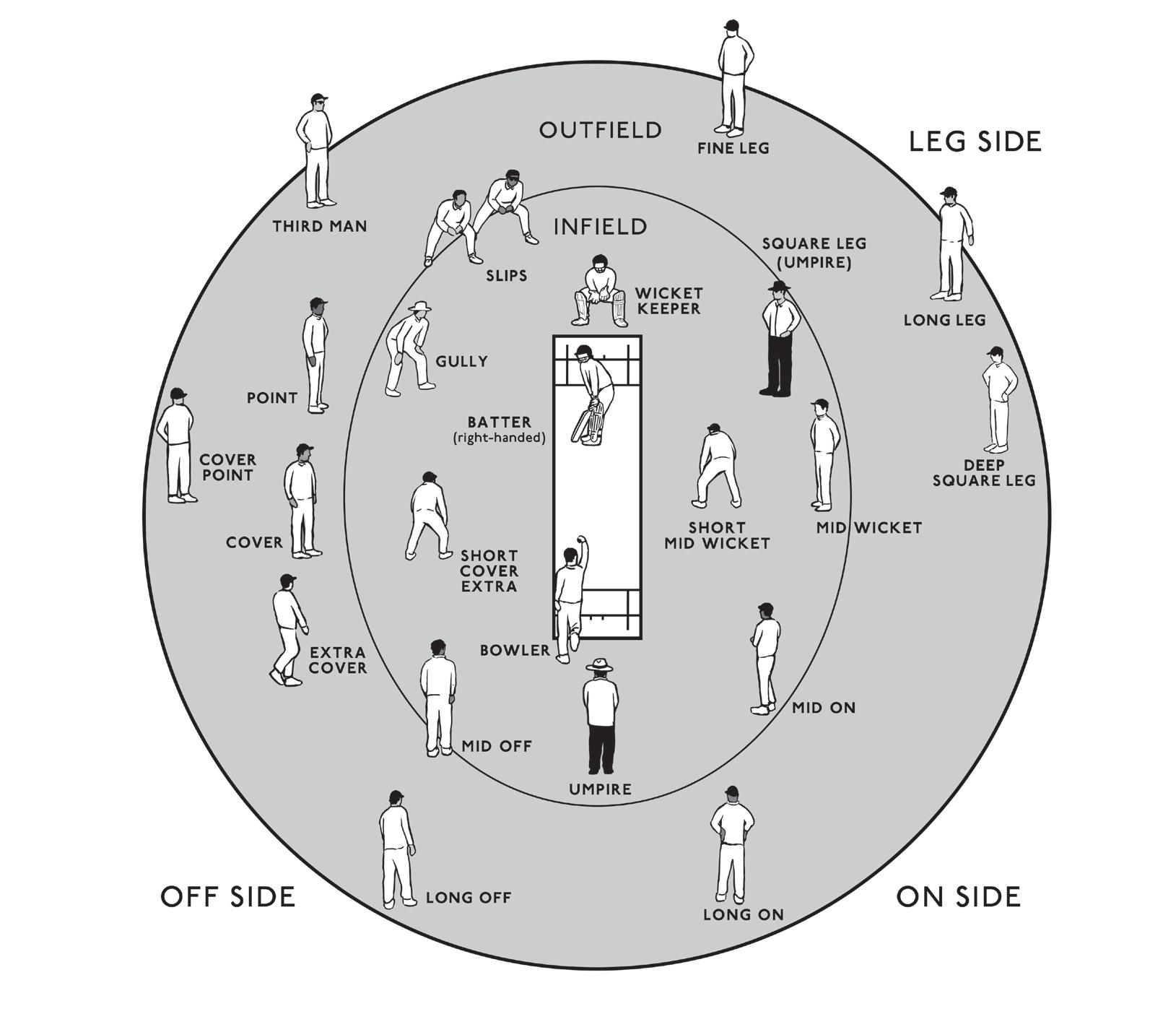

I started out playing for Surrey Women Seconds. I was quite a bit younger than most of them but it was a great way to meet the club captain and some of the big characters. Then I got my chance to step up to the first team. We were playing at New Malden and I was fielding at square leg. In my mind I was telling myself: be keen, you’ve got to look sharp, and I kept pushing closer and closer to the batter to the point that I ended up just a few yards from the stumps – more short square than square leg. The captain constantly tried to move me back, but I couldn’t stop myself creeping forward. Then the batter belted a pull shot, straight at me. By then I was so close I had little time to react and as I dived for the catch I realised in a split second that I’d overshot. In another split second I calculated my options, which were either to let the ball go through my arms for four or halt it with a head-butt. I chose option two. I collapsed in excruciating pain, a giant egg came up on my forehead, my mum was on the outfield screaming and I got carted off to A&E. I’d been so desperate to impress, to be a ninja in the field, and I’d ended up a liability. But, as I later tried to point out, I had saved a boundary, albeit in unconventional style, and I had put my body on the line for my team. It didn’t stop me being a laughing stock, though. I suffered banter about that ‘head-butt’ for weeks.

Soon after that I got a letter from the England and Wales Cricket Board, inviting me up to Trent Bridge to train with Junior England. It was addressed to Ebony-Jewel RainfordBrent and I remember saying to my mum: ‘I don’t think they mean me.’ Mum gave me one of her looks: ‘Really,

Ebony? Because there aren’t too many with that name.’ In fact, I have three more given names – Cora-Lee, Camellia and Rosamond – and you can see why they left those off the letter. The reason I am over-monikered is that I was the youngest of four children and the only girl. Mum had always wanted at least one girl and had names lined up to honour various grandmas. But each time she got pregnant she produced a boy and so the names never got used. She saved them up, added more and by the time I finally arrived there was a bafflingly long list. Mum admitted that she even contemplated a few late additions and announced these to the registrar at the last minute, just as my birth was being recorded. Dionne was one; Randell another. The registrar gently pointed out that there wasn’t enough room on the certificate and that four given names was probably enough for anyone, especially as two of them, like my surname, were double-barrelled. So Mum stuck with Ebony-Jewel Cora-Lee Camellia Rosamond. Years later this caused absolute chaos on scorecards and I even vied with Sri Lankans to get into the top-ten list of the longest names in cricket. I realised I would never make the grade on discovering that Chaminda Vaas’s full name was Warnakulasuriya Patabendige Ushantha Joseph Chaminda Vaas. My room-mate at that Trent Bridge training camp was Isa Guha, who would go on to become a brilliant England international player. She remains a close friend and a great colleague in media coverage of cricket. I was 14, she was 13, and straight away we got on like a house on fire. We’d sit in our room, chatting for hours, making tea, soaking up the excitement, and then be out training with the coaches and senior players like Lucy Pearson. At that time I was an aspiring fast bowler and Lucy was as quick as anyone in the English game. Just being alongside her, seeing her professionalism,

Story

her desire to improve, was a massive inspiration. A few years later she became only the second Englishwoman in 70 years to take 11 wickets in a Test against Australia, which says it all. For Isa and myself, it was a time when our careers were moving faster than I think either of us really expected.

I was initially seen as a quick, opening seam bowler who could smash a few runs in the middle, but once I’d broken properly into the Surrey senior team I started to open both the batting and the bowling. I liked charging in, trying to take batters’ heads off, get them jumping around, targeting their toes – it was all part of the fun. There’s no doubt that I sprayed the ball around a bit. But at that time there weren’t as many women in the English game who were as quick as me and so I suppose I was forgiven. Surrey saw me as a genuine all-rounder, although that switched later on. Jenny Wostrack always told me I was a better batter than I was a bowler and she kept pushing me to work on my batting. She got me on to cricket scholarships and one-to-one coaching sessions and I’m so glad she did because when I was around 19 I suffered a nasty back injury that effectively stopped me bowling for three years.

Up until that injury, fast bowling had been my business. My debut for England came during a 2007 tour, a quad series in India. It involved the top four teams in the world – Australia, New Zealand, India and England – and I was brought along mainly to gain a bit of experience. Then our key fast bowler, Katherine Sciver-Brunt, went down injured and suddenly it was: Ebony, over to you, you’re opening the bowling. We were in Chennai playing a strong New Zealand team in the baking heat on a slowish pitch. Not ideal for my debut. But once our captain Charlotte Edwards chucked me the ball, all I cared about was charging in and bowling as fast as I could. Lottie

was among the best players in the world so simply knowing that she believed I could do the job was a massive confidence boost. There were a lot of no-balls, a few wides but I was bowling just upwards of 70 mph at that time, which was quick for the women’s game. Not as quick, though, as Australia’s Cathryn Fitzpatrick – then the fastest in the world – who seemed to get a lot more out of the pitch than anyone else. What a bowler she was.

Bowling in the heat of Chennai was one of the most punishing experiences of my early career. You’ll sometimes hear players talking about a fast bowler being ‘cooked’ – in other words, the heat has got to her or she’s bowled for too long without a rest. I would have bowled all day at Chennai if Charlotte had let me, but the truth is it wouldn’t have done me or the team any good. You know you need a break when your arm starts to fall away, your follow-through isn’t right and your rhythm – so important to a quick bowler – breaks up. You lose pace first, partly because you know that this will help retain your accuracy, at least for a while, but there comes a point when you’re so tired that everything falls apart.

We didn’t do too well in the quad tournament, although I did get my first England wicket – in the shape of Kiwi opener Suzie Bates – which felt very special. Unfortunately, the feeling didn’t last too long because my back broke down later that year, spasming and cramping, and I effectively canned bowling. I told the England coaches it wasn’t going to work for me, I had to stop and that instead I was going to be a batter. They were sympathetic but not slow to point out that I might not make it back into a team where my batting position had been No. 9. That sounded like a challenge, so it was off to Australia for the winter to make my case. I was playing alongside the likes of Karen Rolton – a superb Aussie batter and captain

My Story and my favourite player globally by miles. That winter got me scoring runs on good pitches, form I was able to take back home the following summer as an out-and-out opening batter. I was the leading run-scorer in county cricket that year, in no small part thanks to Surrey who were truly amazing in the way they supported me and helped me through a difficult time. I got back into the England squad at the start of 2009 – just in time for an ICC World Cup in Australia.

In the build-up games we were just unstoppable. Claire Taylor, Sarah Taylor, Charlotte Edwards, Katherine SciverBrunt – they were all on fire. I was an in-out-in-out squad player and my first game in the tournament was against Pakistan, opening the batting with Sarah Taylor, which for me was living the dream. Four years previously, when my back had gone, I’d written down that my goal was to play in the 2009 World Cup. Now here I was, playing as an opening bat alongside Sarah, in a team that had been battered in recent years but now feared no one. That 2009 run of winning the Women’s World Cup, a World Twenty20 and a Women’s Ashes series easily stands among the greatest years of English cricket – men’s or women’s – and I was so proud to have played a part in it. We fell off a cliff afterwards but fortunately everyone forgot about that. Three years later my playing days were over and I’d begun a new career in the media.

I feel so privileged that cricket has been my life from the moment I bashed that ball out of the school playground. It’s taken me from the rigours of street cricket in south London, through years doing the rounds of youth and amateur club games, the step up to Surrey and county cricket, the astonishing realisation that coaches thought me good enough to play for England and the pure elation of being part of a World Cupwinning team. Since ending my playing career ten years ago,

I’ve been able to see the game from a different perspective, both as Surrey’s first director of women’s cricket, managing championship-winning sides, and later as a broadcaster including regular stints with the BBC ’s brilliant TMS team. I’ve learned so much in the three decades I’ve been involved and yet barely a day goes by without discovering some new aspect of a sport that, for me, never stops giving. I hope to give you the essence of my experience in How to Read Cricket.

I know, it’s not an auspicious start for our aim of demystifying cricket. However, before we get into our A–Z topics, it’s worth briefly clarifying cricket’s main formats. While the Laws don’t change unless the Marylebone Cricket Club says so (more on which below), formats and tournament rules certainly do. Games can be played as five-day Tests, 50-, 20- or 10-over matches and, with the birth of The Hundred in England, even 16.67-over matches (that’s 100 balls per side, in case you were wondering). You’ll sometimes see Tests referred to as the ‘red ball’ game and limited-overs formats as ‘white ball’ cricket (see C for Coloured Balls). On the international stage, the latter includes T20Is (Twenty20 Internationals) and 50-over ODI s (One Day Internationals). And, whatever the format, pink balls will occasionally make an appearance in day–night encounters under floodlights. But take heart: to the casual cricket-watcher none of this really matters. The point and essence of the sport remains the same; it’s just that teams use different tactics to try and win.