UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Century is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

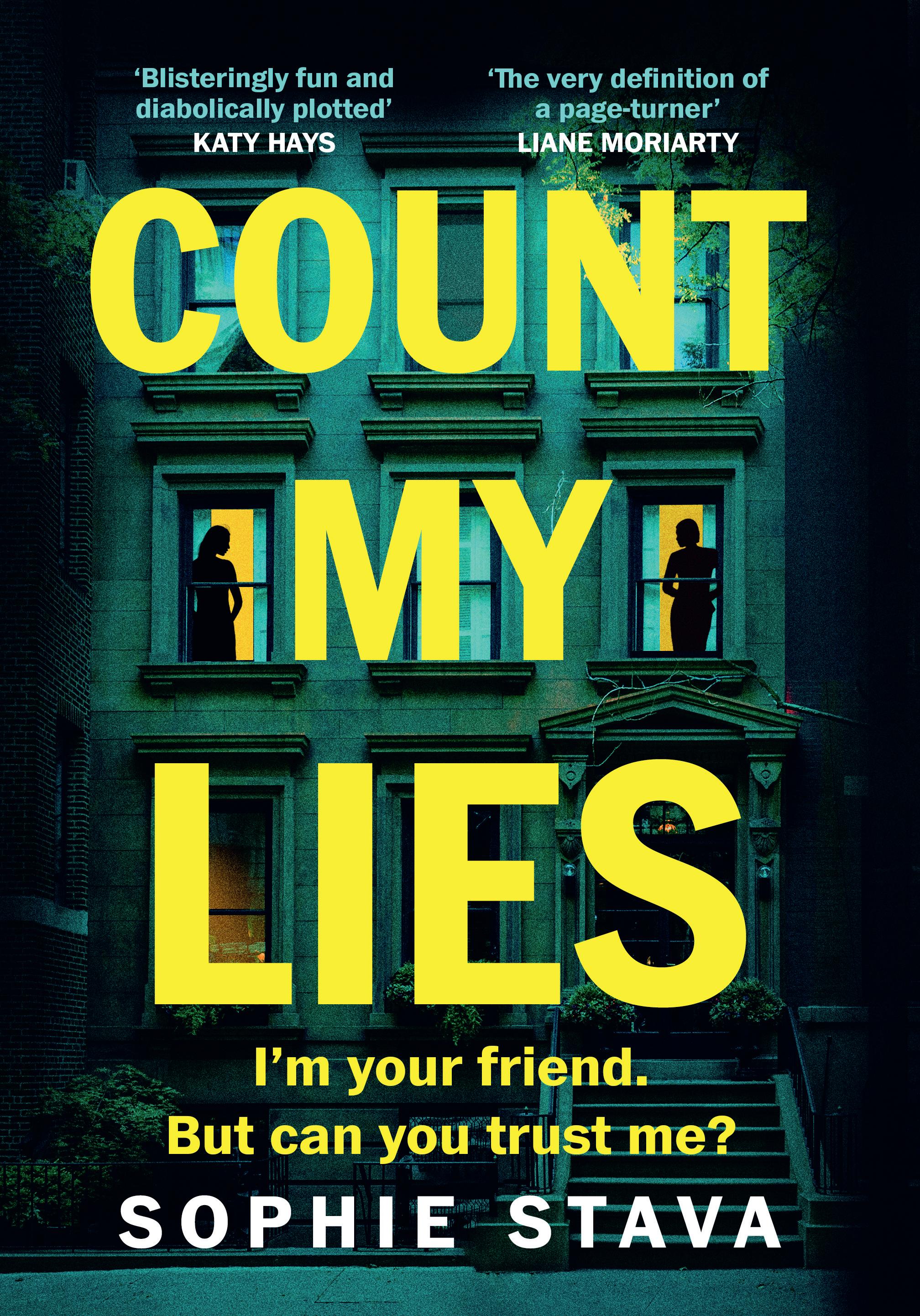

First published in the US by Scout Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC 2025

First published in the UK by Century 2025 001

Copyright © Sophie Stava, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–1–529–94360–3 (hardback)

ISBN: 978–1–529–94361–0 (trade paperback)

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

“If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember

MARK TWAIN

anything.”

“I always thought it would be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.”

TOM RIPLEY, THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY

I’m a nurse.” The words fall out of my mouth before I can stop myself from saying them, loud and clanging like a pair of tin cans tied to a back bumper. If I could reach out, catch them by the tail, and reel them back in, I would, but it’s too late. They’ve been heard; two heads turn.

I should walk away. Or laugh, say I was just kidding. But when the dad and little girl look up at me from the park bench, his eyes shining with hope, her eyes shining with tears, I feel such a rush that I don’t do either. Instead, I kneel beside the girl and smile broadly, first at her, then at him.

“You need to ice it,” I say to the man, my voice clear and steady, the slightest air of authority that I assume someone in the medical field would naturally possess.

The thing is, I’m not a nurse. I never have been. What I am is a liar.

I had heard the little girl’s wails from across the playground, long drawn-out sobs that drew me toward her. I’ve always been nosy, leaning in to hear strangers’ conversations, taking a step closer to read over someone’s shoulder, glancing at the person next to me on the subway,

straining to see the text messages on their phone. It’s another bad habit of mine. Add it to the list, okay?

“Let me see,” the dad was saying to the little girl as I walked up, holding her bare foot in his hand. “Where’d it sting you? Here? Or here?”

I’d wanted to help; he’d seemed so flustered, so unnerved by it, that, almost without thinking, I’d opened my mouth and the lie had dropped out. Clunk, onto the sidewalk, startling them both. I meant well, really, I did. I know, the road to hell, right?

Now, I glance around at their belongings. Just a paper sack lunch beside them, contents strewn over the bench. A half-eaten sandwich. Apple slices, already browning, carrot sticks. Two drinks: a can of grapefruit-flavored sparkling water, a juice box.

I grab the can. It’s cool, not cold, but it might help. “Here,” I say, holding it toward the man. He takes it. Our fingers brush, just slightly, his surprisingly soft. “Is the stinger out?”

The dad frowns at his daughter’s foot. She’s still whimpering, but the intensity has lessened. She’s looking up at me, eyes wide. Her face is tear-streaked. Snot leaks from her nose. She’s doll-faced with bangs and long lashes, a real cutie. So is he, to put it mildly. I can still feel his fingers against mine.

“I think so,” he says. “Would you mind taking a look?”

A flick of pride. He trusts me. Of course he does. I’m a good liar— and, well, there’s the convenient fact that I’m wearing scrubs.

“Sure,” I say, smiling. Still kneeling, I reach out and lift up her little pink sole smudged with dirt. She’s four or five, her foot tiny in my too-big hands. They’ve always been large for a woman, even when I was a kid. Mitts, my aunt would always tease, holding her palm up to mine. I’m still self-conscious about them, keeping hand-

shakes brief, tucking them into my pockets, under my thighs when sitting.

I squint at the bottom of her foot. There’s a small red welt and, in its center, a black dot. The stinger. I suck in air between my two front teeth, shaking my head. “It’s still in there.”

He frowns and peers down at it. “Should I—?”

“You need to scrape it out. With a credit card or something with a flat edge. Don’t squeeze it; it could make it worse.”

I’m pleased by how competent I seem, how knowledgeable, like I actually know what I’m talking about. I do, I guess; I also happened to step on a bee in this very park, late last summer. I’d spread out a blanket and kicked off my shoes before I lay down to read. When I got up, my sneakers still in the grass, I felt a sharp jab on the bottom of my foot. I sat back down to examine the injury, cursing under my breath, and saw the crushed bee, the stinger still stuck in my skin. I squeezed carefully, forcing the stinger to the surface. It was only later, when I googled it in a blind panic, that I realized my mistake.

By the end of the day, my foot had almost doubled in size, turned bright pink, swollen as a little sausage. It took three days for the itching to stop and another four before the swelling went away entirely. I limped on it dramatically for the whole week, recounting the saga to anyone who so much as raised an eyebrow in my direction. Although, truth be told, I might have claimed it was a swarm, not a single bee. The point is, I do have some experience in this area.

The dad reaches into his back pocket, returning with his wallet. “Thanks,” he says gratefully. “If you weren’t here, I’d probably have called 911.” He smiles to show me he’s joking. His teeth are bright white, straight and even. He’s handsome in an obvious, teenageheartthrob sort of way, probably early thirties, my age.

He slides a credit card from one of the wallet’s slots. “Let me see your foot, sweetheart,” he says.

As he drags the card across her sole, I see the name on the card. Jay Lockhart. Jay Lockhart. I like the sound of it, like it would roll off my tongue if I said it out loud. Jay as in Gatsby, love-crazed millionaire, charming, hot-blooded. I look back at the man—Jay—and decide it fits him, with his boyish smile, playboy face.

“Got it!” Jay announces, triumphant, holding up an infinitesimal black speck—the stinger, presumably—between his thumb and forefinger. “See?” He shows it first to the little girl, then to me.

“Good work!” I say, smiling at him. He looks so proud, like he’s just placed in an Olympic event. Maybe not gold, but bronze, still very respectable.

When he smiles back, I feel a slight blush color my cheeks. It feels like we’re sharing the victory together, like he might reach out and hug me, his winning teammate.

“Feel better?” he asks the little girl. She nods, stops sniffling. He reaches out and wipes her wet cheeks with his thumb, smooths her silky bangs. I notice he isn’t wearing a wedding band.

“You should ice it when you get home,” I say, standing back up, “to keep the swelling at bay. And you might want to give her some Benadryl, just a half dose, maybe. It’ll help with any itchiness.”

“Seriously, thank you. Can you say ‘thank you,’ Harper?” Jay turns to the little girl. “Say, thank you, Miss . . . ?” He trails off and looks back at me, for my name.

“Caitlin,” I say. Another lie. I don’t even know where it comes from. Have I ever even met a Caitlin? Once, maybe. When I was younger, I think I did ballet with a girl named Caitlin. Or was it Carly? We were in the same class at a local community center, but that’s where

our similarities ended. She had long, waist-length hair she wore in a beautifully woven braid down the center of her back, sparkly barrettes clipped into the sides, and brand-new ballet slippers, their pink satin gleaming. I danced in old socks. She was the best, whatever her name was, the lead in the recital. I was Sugar Plum number six. The young girl with the bee sting, Harper—her name bougie, but cute, exactly what you’d expect in this neighborhood—also has a single, glossy braid, her bangs neatly combed. Maybe it’s why I thought of the name: she reminds me of her.

“Thank you, Miss Caitlin,” Harper dutifully recites.

“My pleasure, Harper,” I say. “I hope your foot feels better soon.”

She offers me a tentative smile, staring up at me with her big brown eyes. Then she looks back at her dad. “Can I finish building my castle?”

Jay nods, smiling, and she slides off the bench to a scattering of sand toys on the ground.

He looks back to me. “I’m Jay, by the way,” he says, standing up and extending his hand to me. He’s taller than I expected, well over six feet.

“Nice to meet you, Jay,” I say. When we shake, there’s a current. At least, I feel one. He didn’t have to introduce himself, but he did. That’s something.

There’s a pause, then he says, “Everyone’s a liar, right?”

My heart stops beating, lodges itself in my throat. “What?” I manage. How could he—?

Jay smiles, then gestures toward my hand, dangling by my side. I’m still holding my book, the one I was reading when I first heard Harper wailing, my fingers tucked between the pages where I left off. It’s a well-worn paperback copy of Murder on the Orient Express, the edges of the cover curled up, soft with wear. “Sorry.” He grimaces apologetically. “Did I spoil it? It looks like you’ve read it before. I just assumed—”

“Oh.” I let out a little laugh, exhaling in relief. “No, it’s probably my tenth time. You’ve read it, too?”

Jay nods. “I loved the detective, Hercule Poirot. My parents gave me a box set of the series for my twelfth birthday. I always tried to solve the case before he did. But I never could.” He shakes his head ruefully.

I laugh. “My favorite Agatha Christie is And Then There Were None. The ending was—” I make an explosion noise. “Whoa. I never saw it coming.”

“I haven’t read that one. It’s that good?”

“I could bring you my copy,” I offer. “Do you come here a lot? I’m usually here a few times a week.” I hold my breath and feel my heartbeat accelerate. I’m probably overstepping. I often do.

But here’s the truth. I know this isn’t their first time at this park. I’ve seen them here before. Twice, actually, earlier this week. I’d been hoping for another sighting today, pleased when I saw them approaching. Harper’s crying really did catch my attention, but I’d also been keeping an eye on them as I leafed through my book, glancing up every few pages or so, watching her on the monkey bars, the swing.

That first day, Tuesday, I noticed Jay before I noticed Harper. I’m pretty sure all the women at the park did. Not only because he was one of the few men here, but because he looks like he belongs on a movie set in LA, not on a playground in the heart of Brooklyn.

Like I told him, I’m here most days, ducking out of work for an afternoon breather, so I’m familiar with the regulars. I often see the same kids with the same nannies, the same groups of moms sitting next to each other, chatting on the benches as their offspring bound through the playground, shrieking. I like this park, how happy everyone seems, the sunlit patches of grass, the smell of the honeysuckle

bushes that line the perimeter. It’s busy even in the colder months, the kids bundled up, their cheeks rosy.

“That’d be great,” Jay says, responding to my offer, “but my wife is usually the one who brings Harper here. I had the week off, so I’ve been the one on park duty. It’s back to the grind on Monday.”

When he says “my wife,” my heart sinks, which makes me feel even stupider than I already do. What, did I think this was the start of a romantic comedy, that I’m Liv Tyler in Jersey Girl? I know it’s an outdated reference, but what woman doesn’t fantasize about a widowed Ben Affleck finding comfort in their arms, grief-stricken and vulnerable? A motherless little girl gazing up at them adoringly? Yes, it’s a little morbid, but I can’t be the only one. Oh god, am I?

“I’ll tell her to look for you next time she’s here,” Jay says. “Apparently, this is Harper’s new favorite park.”

I force a broad smile as if the thought of meeting his undoubtedly beautiful wife fills me with unbridled joy. “Great,” I say, hoping to sound chipper. “I’m usually here around this time. Maybe I could bring the book to her.”

Here’s how I know I’m not pretty. No married man would tell his wife about the gorgeous, single woman he befriended at the park. Not unless his IQ was below functioning, or he was hoping to be smothered in his sleep later that very night. And Jay doesn’t appear to be stupid, or to have a death wish.

But I’m not surprised. I know I’m not the sort of woman who is a threat to other women. My nose is slightly too large, jaw angular. On good days, I tell myself that I’m handsome, like one of those black-andwhite movie actresses, strong-featured. Greta Garbo, maybe, if the lights are low. And I don’t do myself any favors. I know I could spend more time on my appearance; I don’t have to look quite as schlubby as I do.

I could dress better, for one, but instead I wear what’s comfortable, clothes I’ve had for years that should have been donated—or tossed—ages ago: high-waisted jeans with holes in the knees, buttonup flannels, oversized, stretched-out sweaters. Thanks to the ebb and flow of fashion, it might actually be cool if it was intentional—or if it wasn’t paired with half-brushed buns and cheap, plastic-framed glasses, scuffed sneakers. I do have contacts (and a hairbrush), but most mornings I’m running late, scrambling out the door partially dressed, just-burnt toast crammed in my mouth; the contacts (and hair brushing) usually fall to the wayside.

It’s not that I don’t have nicer clothes—I do—I just haven’t had a good reason to wear them recently. Because instead of cardigans and slacks, I wear scrubs to work. Mauve-colored, to be specific. My boss, Lena, handed them to me on my first day with a proud smile. She picked the shade herself.

I’m not a nurse, but a nail technician at a small, boutique day spa that offers seventy-five-dollar manicures and pedicures, sugar waxing, and a three-page menu of signature facials. Nurse, nail tech, what’s the difference, really? Oh, right, everything. The chasm between fixing a broken arm and a broken acrylic is wide and deep.

Currently, along with the scrubs, I’m wearing the aforementioned plastic glasses, a pair of gold studs, and a chain-link choker I grabbed on my way out.

I touch my hand to the necklace. I found it at a little shop I passed on my way home from work a few weeks ago. I’d stopped in to kill time, not intending to buy anything, but as I walked by the checkout counter, I noticed it through the glass case, the gold glinting. The salesgirl offered to put it around my neck so I could see how it looked. It fit perfectly. The chain was delicate, tiny links woven together,

with, right at the base of my neck, one tiny iridescent pearl. I paid for it and wore it out. When Natasha, my coworker, commented on it the next day, I told her it was a family heirloom, passed down from my grandmother.

But—prepare to be shocked—even with the earrings and choker, I’m no ten. Jay’s wife probably looks more like Liv Tyler than I ever will. The Daisy to his Gatsby. Lithe, with high cheekbones. Full lips, curls spilling down her back. No frizz in sight.

“Five more minutes, Harp.” Jay stoops to touch the top of the little girl’s head. She nods absent-mindedly. She seems to have forgotten about her bee sting and is now playing happily by our feet, pouring sand from a shovel into a bucket, then tipping the bucket upside down.

I shift my weight from one foot to the other. I should go—I’m due back at work in less than ten minutes—but Jay is far more interesting than what waits for me there. And he said he only has five more minutes. If I walk quickly, I’ll be able to make it back on time. So instead of leaving, I say, “You said you had the week off?”

He nods. “Harper’s preschool is closed for spring break, so I took the week off, too, to spend some time with her.”

“What do you do?” It’s another bad habit of mine, talking too much, asking too many questions. It’s probably the same reason I lie: to fill the silence, keep people from walking away.

Look, I’m painfully aware of how pathetic that sounds. It’s just that my job is so boring. My life is so boring. Bland and dreary. I’d do almost anything for a sneak peek into someone else’s. And his seems especially interesting. Technicolor, so bright you have to squint. I’d bet everything that I’m right.

“I started my own company last year, in online game development.

Which basically means I’m a big nerd,” Jay jokes, smiling, eyes flashing. I notice he has a dimple in his right cheek.

He’s not a nerd. Far from it. He never has been. You can tell just by looking at him. Like I said, he’s tall, really tall, at least six-three or six-four, with dark hair that he keeps raking his hand through, brushing it from his eyes. His jaw is strong, clean-shaven, skin tanned and smooth.

“Sounds exciting,” I say. “Starting your own company.”

“It can be.” He shrugs. “Not as altruistic as a career in nursing, but it pays the bills.”

Right, I’m a nurse. I smile modestly as if I deserve his compliment. I wish that I did.

Jay glances at his phone. “Shit, we have to head out. I promised I’d have Harper home by three.”

“Is it that late already?” I say, feigning surprise. “Shoot, I have to run, too.” Of course, it’s back to my real job, nary a patient in sight. “It was nice to meet you.”

“You too, Caitlin.” His smile makes me feel like he means it, my stomach flip-flopping. “Like I said, I’ll tell my wife to keep an eye out for you.”

I grin back, showing my teeth. “I’d love that.” I’m a liar, remember?

I watch as he and Harper leave the park, hand in hand, their arms swinging. When they reach the gate, Jay turns, gives me one last wave. I wave back but wait until they disappear from sight before I turn and leave, too.

It occurs to me, though, on the walk back, that the reason I’d thought he might be single is that he wasn’t wearing a wedding ring. I can’t help but wonder why not.

Mom?” I call out when I get home from work, easing the front door shut behind me and setting my keys on the little table in the entryway. “I’m home!”

“Sloanie? Is that you?” That’s my real name, Sloane. Sloanie, Sloanie, full of baloney. And yes, I live at home with my mother. I know, I know, another notch on my belt of accomplishments. I’m working on it. Really, that’s the truth. Hand to heart.

“Yeah, it’s me, Mom,” I answer loudly. I kick off my shoes, drop my purse next to them, and walk down the short hallway into the living room. She’s in her recliner with the TV on, wearing a light blue tracksuit and thick wool socks like a character from a seventies sitcom. I cross the room and bend over to drop a kiss on her cheek, glancing at the screen. Murder, She Wrote, her favorite old show. She’s likely seen this episode at least three times before.

“How was work?” she asks, lowering the volume from blasting to blaring. She squints up at me, looking far older than her age, her short, wiry hair almost all gray, the lines across her forehead, around her eyes and mouth, deep.

“Fine,” I say, shrugging. “I’m going to get dinner started. You hungry?”

She nods and points the remote back at the TV, the sound returning to an assaulting level. I’m surprised the neighbors don’t complain. Both my mother’s eyesight and hearing are declining. Years of working on her feet as a house cleaner have ruined her back, leaving her hunched and aching, her joints stiff. She’s had rheumatoid arthritis since her thirties, managed by medication, but it’s taken its toll, finally rendering her unable to move most days, let alone work.

She spends her days in a well-worn corduroy armchair in the corner of the living room, a heating pad on her backside, legs stretched out before her, peering through smudged glasses at the TV as reruns of Unsolved Mysteries and Forensic Files degrade the screen. She drinks cup after cup of oversweetened, lukewarm coffee, followed by one whiskey at five, then another cup of coffee before bed, this time, decaf. It wasn’t my plan to be living with my mother in my thirties, but at least I can keep an eye on her. By now, taking care of her is second nature, something I’ve done for as long as I can remember.

I head into the kitchen and open the fridge. There’s some leftover roast chicken from the dinner I made last night that I warm up and shred into a bowl, along with a handful of chopped-up cucumbers and carrots, some romaine lettuce. A modest attempt to counterbalance the Chinese takeout my mother frequently has delivered for lunch. I divvy the salad between my plate and my mom’s, then head back into the living room.

“Thanks, Sloanie,” my mom says, taking the plate from me. Then she mutes her show. She likes to hear about my day when we eat.

“I did Dolly’s nails today,” I say, biting into a carrot.

I’ve been working at the day spa—Rose & Honey—for almost a year

now. I wandered in one afternoon when I saw the Help Wanted sign posted in the window. I’d walked by the black-and-white awninged storefront at least a hundred times, but had never gone in. By that point, I’d been out of work for months. I couldn’t get hired anywhere, at least not doing what I was qualified for. I’d get through a few rounds of interviews, but no job offers materialized. I knew why, of course, so it didn’t come as a surprise, but that didn’t make it any easier. Doing nails sounded like a reasonable alternative, something I could be good at if I tried.

The woman at the front desk looked pleased when I asked for an application. She pumped my hand vigorously, introducing herself as Lena, the owner of the spa. She was a heavyset, Eastern European woman with impeccable makeup, kohl-rimmed eyes framed by long lash extensions, porcelain skin, pouty red lips. She’d opened the shop a few years ago, she told me in thickly accented English, and she was adding another manicurist to her team, someone reliable, someone she could count on. Why not, I thought, how hard could it be?

When Lena asked if I had a cosmetology license, I said that I did, that I’d recently passed the exam. I figured I could find a certificate to doctor, if and when she offered me a job. I was invited back for a practical interview, which, she explained, meant I’d be demonstrating my skills and giving her a manicure. I spent the next week on YouTube, pausing the videos at each step to practice on my mother, filing and refiling, painting and repainting. I memorized the steps, which were easy enough—clean, clip, file, buff, cuticle care, exfoliate, moisturize, base coat, paint, top coat—and showed up with my own set of manicure tools that I’d bought at a local beauty supply store with a twentyfive-percent-off coupon. When I was done, Lena examined her nails, smiled, and offered me the job.

“You have good hands,” she’d said, nodding appreciatively at them. I looked down. Next to Lena’s, they seemed even bigger than usual. Who’d have thought my big hands would turn out to be an asset? The pay was twenty-one dollars an hour, she continued, plus at least an extra thousand a month in gratuities, sometimes more; her clients were generous, Lena told me, alluding to the deep pockets in Cobble Hill. It was slightly less than I made in my last position, even with the tip money, but as they say, beggars can’t be choosers.

I accepted the job on the spot, handing over a forged cosmetology license that I’d Venmoed some guy online fifty bucks for. Lena glanced at it, distracted by a ringing phone, then told me I could start the following day.

It’s a good job, mindless, easy, and most of the clients leave at least twenty percent, sometimes thirty, at the end of their service. Between that and the social security checks my mom collects, we have enough for our rent, our bills, but it’s not nearly enough to keep me from wishing for something better—something more—or from dreading the sound of my alarm clock each morning, its blaring chimes grating.

“And how is she?” my mother asks, referring to Dolly—as in Parton. An homage to the Queen of Country herself. I make up names for my regulars, the ones I see week after week, women I’ve come to know through their too-loud phone conversations or idle chitchat. Dolly Parton is really Laura Hoffman, but they share the same big blonde hair and oversized chest. Laura even has a slight Southern twang, although she grew up in Texas, not Tennessee like Dolly. She’s a Dallas transplant, having moved to New York after she met her husband while he was on an oil expedition—or whatever tycoons do when they travel for business.

“Her stepdaughter wants the Lamborghini,” I say. Laura’s

husband—very old and very wealthy—died two years ago. She’s been in litigation with his children since, fighting over every last cent the old coot had to his name. Which was quite a bit. Laura updates me on the developments when she comes in every week. She lives in a penthouse in Manhattan—on the Upper East Side, where else—but she has a son from a previous marriage in Brooklyn Heights, a few streets over from Rose & Honey, so she drops in on the days she meets him for lunch. Heads turn sharply when she walks in, a blinding contrast to our typical bougie Brooklynite clientele.

“But,” I continue, “Laura says she’d rather sell the car for parts than see that spoiled twat riding in it. Her words, not mine.”

“Where do you park a Lamborghini in Manhattan?” my mother asks. She sounds genuinely curious.

I shrug. “She said something about a private garage? Neither one of them even drives. Laura says Cassie doesn’t have a license. Instead of a car on her sixteenth birthday, she got a driver.”

My mother snorts, rolling her eyes. Her tolerance for wealthy women is lower than mine. I like Laura, though, how she opens the window to her soap-opera life, offering me a glimpse inside. She also treats me like a human being rather than an inanimate object who happens to know how to file nails, which is more than I can say about most of my clients.

“But she found out her son’s expecting his second baby, so she was in a good mood. She tipped double.” Laura usually hands me a fifty on the way out—one of my only cash tippers—but today it was a Benjamin, crisp, green, newly printed. I started to protest, but she waved me off with an exaggerated wink.

This isn’t the whole truth, though. She likely gave me the extra money because at the start of her manicure, I had mentioned that I’d

spilled coffee all over my MacBook, frying the hard drive and subsequently erasing the last fifty pages of the novel I told her I’ve been working on. Her hand, nails still wet, flew to her mouth. Oh no, Sloane! Obviously, there is no MacBook, no novel. But the lie was as much for me as it was for Laura. I wish there was a half-written manuscript on a laptop, that I spent evenings hunched over a keyboard instead of days hunched over women’s feet. Christ, anyone would. I had no idea she’d double her tip. If I had, I wouldn’t have said it. I swear.

It’s just that the truth is so uninteresting. Amending it, changing the details, adding in color, is something I started when I was a kid, a bad habit—like biting your nails or picking at scabs—that I never grew out of. In fact, I grew into it, the lies rolling off my tongue more and more naturally, almost reflexively, until it became instinctive, part of who I am. It almost doesn’t occur to me to tell the truth anymore. Why would I? When you tell the truth—at least, if the truth is boring, which it almost always is—people begin to fidget, their eyes glazing as their attention wanes. Eventually, they realize, snapping to with a sheepish Oh, I’m sorry, what were you saying?, trying to feign interest.

I hate that look. The fake, vacant way they smile at you. I always have. It makes me feel unimportant, like a crumpled piece of paper, tossed on the floor instead of in the wastebasket. I used to get it all the time when I was younger. My mom and I moved around a lot, hopping from town to town, apartment to apartment, school to school, as she changed jobs, one after the next. I was always new, always standing at the front of a classroom, palms sweaty, as the teacher instructed me to introduce myself. I’d start haltingly, staring at my shoes, saying that I was born in Florida, that I’d moved from whatever Podunk town we’d just come from, and I’d look up to see that no one was even paying attention. The girls were passing notes and whispering, the

boys kicking each other across the aisle. The teacher would shush the class, but even she was distracted, writing on the chalkboard or handing out worksheets. I stared longingly at the girls, wishing I was the one being whispered to. But my pants were too short, sneakers too scuffed, shirt too faded to catch the eye of anyone. It was a shitty feeling, the invisibility. Every time, I wished we didn’t have to move, but I understood why.

My mother was hardworking, scrupulous to a fault, but when her arthritis flared up, she was housebound, unable to work, spending the day with her hands and feet submerged in water as hot as she could stand. When I got home from school, I’d climb into bed with her and rub her joints with castor oil and Tiger Balm, turn on one of her favorite movies to distract her from the pain. Eventually, her employer would begin to complain about her absences, giving her a warning, then another, until she came home with a final paycheck.

We’d move when the landlord started banging on the door, shoving late notices through our mail slot. We would find a new town, twenty miles in whatever direction, another shabby apartment that didn’t run background checks, and I’d start a new school. Rinse and repeat. I got used to it, though, expected it every few months.

It was just the two of us, making our way in the world. I never met my father, didn’t even know who he was other than a brief fling in my mom’s early twenties. Her parents—my grandparents—had died a few years after I was born, and her sister was older, living hours away. We were fine on our own. We had to be.

In fifth grade, when my mother and I moved to Whispering Pines, Georgia, a tiny suburb on the outskirts of Macon, I told myself things would be different this time. On the first day, when the recess bell rang midmorning, I followed the class out to the blacktop where a

group of pigtailed girls circled around me. “Where are you from?” one of them asked. You could tell she was cool by the number of neoncolored rubber bracelets looped around her wrist, hot pink and lime green, bouncing when she walked. She had bangs, and when I got home that night, I gave myself bangs, too, standing on a chair in front of the bathroom mirror, kitchen shears in hand.

“California,” I said. I didn’t know where it came from. We hadn’t moved from California; we’d only driven an hour north, not even crossing state lines, just one county to the next. By the grace of god, the teacher hadn’t asked me to the front of the class that morning, hadn’t mentioned me at all. I was a blank canvas, a tabula rasa.

As I watched the girls’ faces light up, something inside of me swelled. I knew I’d said the right thing. The girl with the bracelets beamed at me. “Are you famous?” she asked excitedly.

I shook my head no, but when I saw her disappointment, I quickly added, “But my dad is. He’s in the movies.”

Their gasps were audible. And just like that, I was special. It was so easy.

That day, so unlike all my previous first days, everyone fought to sit next to me at lunch. I told them about the beach and the palm trees, describing in detail what it was like to wade into the breaking waves, the colors of the seashells I found on the shore. One summer, I’d won a sandcastle-building contest, I said. Of course, I’d never seen the Pacific. I’d been to Daytona a few times, which aided in my descriptions, along with scenes from my favorite Disney movie, Lilo and Stitch, and my second-favorite movie, Flipper. After lunch we played handball, and the girl with the bracelets—her name was Bianca—asked me to be on her team. I was elated.

When they asked to meet my dad, I told them he was on set, film-

ing a new movie. It could be true, I reasoned with myself. It’s why the lies never seemed so bad. I had no idea where he was or what he did. How did I know he wasn’t an actor?

I knew I should stop, but I couldn’t help it. I wanted so desperately for people to like me, and it was the only way I could think of. It was no more complicated than that: I wished I was more interesting, so I pretended to be. Sloanie, Sloanie, the big fat phony.

But the irony is that the more elaborate my lies became, the further I had to keep people away. I could never invite anyone over. They’d want to know where my puppy was, the one I said we’d adopted over the summer. His name was Pickles, I told my classmates, and he was the runt of the litter, black with white spots. They’d want to see the princess bed I’d described, the one with the sparkly canopy and unicorn sheets. They’d want to meet my dad, the movie star, and swim in our backyard pool with the waterslide. Of course they did. It was why we were friends. And it was also why we could never be friends. Not real ones, at least.

Then, another lie occurred to me, one that would solve all my problems. I came to class one Monday with a long face and whispered into Bianca’s ear that there’d been a fire at our house over the weekend. Everything had been lapped up in the flames, our home with the backyard pool burned to the ground. My canopy bed was gone. So was our dog.

I told her we had to move into an apartment across town, but that it was only temporary, until they rebuilt our house. Maybe she wanted to come over after school one day? The apartment wasn’t as nice as our house, I said, but there was a park across the street we could go to, and I’d saved some of my Barbies before I ran out. Bianca nodded, wideeyed.

By recess, everyone had heard. My teacher, Miss Newberry, pulled me aside at lunch and asked me what happened. I repeated the story I told Bianca, about how my mom had left the stove on, the fire alarm sounding in the middle of the night. She touched my arm, her eyes soft and sympathetic, and told me if there was anything I needed to let her know. And that I didn’t have to turn in any homework assignments that week. I was pleased as punch.

The next day, Miss Newberry announced to the class that the school would be hosting a fundraiser for me and my family, to help us during this difficult time. It would be a bake sale, and she would be sending a sign-up sheet home for everyone’s parents. I smiled shyly, overjoyed by the special attention. But, unsurprisingly, the fundraising never happened. One of my classmates’ moms called mine that night, asking for our new address to organize a meal train for us. I was coloring on the floor of our living room when I heard my mom say, “What fire?” into the receiver, and I knew I was toast.

That Thursday, I sat with my mother in front of the principal, my legs dangling over the chair as he droned on, lecturing me about the consequences of the lie. My mother was mortified, to say the very least.

I was embarrassed, too. Mostly because I’d gotten caught. If I had the chance to go back, I would have done it again. It was worth it for the way everyone looked at me those two days.

I was too young for detention, so the principal made me write an apology letter to my classmates and Miss Newberry. My mother took away my television privileges for a month. But neither punishment taught me not to lie. It taught me to be a better liar. I didn’t make the same mistakes at my next school.

We moved again at the end of the year. In sixth grade, I told one of

my classmates that I rode horses on the weekends, after I finished reading Black Beauty. She did, too, she exclaimed happily, then invited me to her riding club the following weekend. I made up excuse after excuse about why I could never go. Trips to my fictional aunt and uncle’s house in the mountains, dance classes, sleepovers with friends from my old school. All of which meant I had to stay home, alone in the apartment, while my mother worked, instead of with the friends I’d made because of the stories I’d told. I’d stop by the library on Friday afternoons to stock up on the books I spent the weekends reading. Books that kept the loneliness at bay, whose details wove themselves into the web of lies I spun. I lied through middle school and high school, then through community college and beyond. Small lies, usually, but lies, nonetheless. I should have stopped by now—I’m an adult, for god’s sake—but I haven’t. I can’t. I just want so badly to say the right thing, be the right kind of person, that when I open my mouth, out comes what I think someone wants to hear, whether it’s true or not.

It’s not that there haven’t been any consequences—aside from visits to the principal’s office. I’ve lost friends here and there, job opportunities when my references were checked a little too thoroughly. I’m a good liar, but I’ll have slip ups, or someone else will refute my story, and I’ll be exposed.

Sometimes, there are stretches of time that I lie less. Usually after I’ve been caught. I try to change, try to be honest, but after a few weeks, I hear myself saying something that isn’t true, something I hadn’t even planned on lying about, and I slip right back into my old ways like I would into my favorite shirt. It fits, just right. Snug, comfortable, well-worn. Other times, when things are going well, like when I had the job before this one, I don’t feel the need as often. I still do it, unable to help myself, but the urge isn’t as strong.

But here’s the part that makes me an even bigger freak. Sometimes I believe my own lies. They feel real. I get swept up in the fantasy, the telling of it, the retelling, lying in bed at night adding to the story, drifting off and dreaming about it. I think it’s because I’ve always felt like there had to be more to my life than what it was. I couldn’t just be this poor kid with no dad. He had to be out there. He had to be special, which meant I had to be special, too. Doesn’t everyone want to feel special?

“So, a good day,” my mom says. Both a question and a statement. Right, the hundred-dollar tip.

“Mm-hm,” I answer. It was a good day. A very good day. I consider telling her about Jay and Harper, but I don’t. I’m not quite sure why. She’s the one person I don’t lie to, the only person who thinks I’m interesting, just as I am.

Even so, I want to keep them to myself, for now. And leaving something out isn’t the same as lying, not quite. It’s what I tell myself, anyway.

My mom hands me the remote. “You pick the movie,” she says. “I picked the last one.”

I give it back. “No, you choose. I’ll get dessert. We still have that pint of Rocky Road.”

“I’ll take two scoops.” My mom settles back into her armchair as she starts scrolling through the list of trending titles on Netflix. We watched a thriller last night, one about a woman whose husband isn’t as perfect as he seems. Few husbands are, at least in Hollywood, apparently.

In the kitchen, I load our dishes into the dishwasher and dole out what’s left of the carton into two bowls, tossing the empty container into the almost-full recycle bin. I make a mental note to take it out be-

fore the collectors come on Monday. I dim the lights on my way back to the couch, handing my mom her bowl before taking a seat. The title sequence of a movie—another thriller—begins to play, cheesy music rising, and I take a bite of my ice cream, turning the cold spoon over in my mouth.

Almost immediately, I tune out, the screen blurring, sounds fading. All I can think about is Jay and Harper. But mostly Jay. His smile. I wonder if I’ll see him again.

Before I go to bed, I take my paperback copy of And Then There Were None off my bookshelf and put it in my bag. Just in case.

I get to work late on Monday morning. I snoozed my alarm three too many times, then ran out the door as I struggled with the zipper on my hoodie. Luckily, no one cares what time I show up at the spa, as long as I’m there by my first appointment, which, today, happens to be at ten thirty.

Mondays are typically our quietest days, and this Monday is no different. The spa is practically empty. Chloe, one of our three rotating receptionists, is behind the desk. Out of the group, I like her the most. She’s a nineteen-year-old sophomore at Brooklyn College, cooler than I’ll ever be. Her jet-black hair is bleached platinum—her Korean parents almost disowned her when they saw it, she told me gleefully—cut into a sleek bob, short bangs. She wears oversized plastic tortoiseshell glasses, wide-legged jeans, and crop tops. If it’s slow, I’ll do her nails, usually a neon color, bright yellow or orange, like a highlighter.

Behind Chloe, a lone woman is getting a pedicure in one of the four spa chairs that line the left wall. Only one of the six small treatment rooms is occupied, its door shut, sign flipped to In Session. It will pick up a bit in the afternoon, but not by much. Lena takes Monday