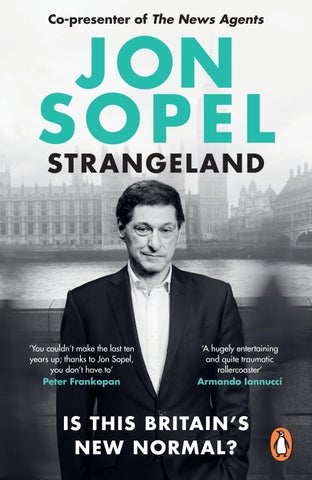

JON SOPEL STRANGELAND

‘You couldn’t make the last ten years up; thanks to Jon Sopel, you don’t have to’

‘A

hugely entertaining and quite traumatic rollercoaster’

Peter Frankopan IS THIS BRITAIN’S NEW NORMAL?

Armando Iannucci

‘You couldn’t make the last ten years up; thanks to Jon Sopel, you don’t have to’

‘A

hugely entertaining and quite traumatic rollercoaster’

Peter Frankopan IS THIS BRITAIN’S NEW NORMAL?

Armando Iannucci

Also by Jon Sopel

UnPresidented: Politics, pandemics and the race that Trumped all others

A Year at the Circus: Inside Trump’s White House

If Only They Didn’t Speak English: Notes from Trump’s America

Tony Blair – The Moderniser

Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Ebury Press is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Ebury Press in 2024

This paperback edition published in 2025 1

Copyright © Jon Sopel 2024

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529938418

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Two bundles of pure joy – annoyingly 10,000 miles away

As a visual metaphor for the Britain I came back to at the beginning of 2022 after eight years away, it was pretty perfect. Arguably the country’s most famous landmark – which has graced a zillion postcards and features in any movie where scenes are filmed in London – was swaddled in plastic, held together by a complex lattice of scaffolding, with the clock at the top of the Elizabeth Tower unable to bong. Unable to lure Dick Whittington back.

Big Ben, the Palace of Westminster’s iconic timepiece, which ensured Parliament knew when to start business and told us when debates would end and votes begin, was out of action, the tower in danger of crumbling into the River Thames below.

This was a Britain that while I had been away had charted a new political and economic course for itself with the referendum to leave the European Union. At a time of rising economic protectionism, Britain voted to leave the biggest single market in the world – an act of self-harm that bewilders policymakers around

the world, particularly in America, but which won the support of 52 per cent of British voters after a bitterly fought campaign.

Though the vote to leave the EU was six years earlier, 2022 would turn out to be the year when the political aftershocks of that decision would bring down the structures made unsteady by that June 2016 earthquake referendum – and it seemed to collapse in a pile of dusty masonry, twisted metal and broken glass. The sturdy political pillars of the UK would go through a rolling, rumbling, sometimes comedic convulsion. It would be the year of three prime ministers, four chancellors, a home secretary who lasted six days (six times longer than the education secretary who was there for just one). At the height of this absurd spectacle, another convulsion shook us to the core, when Queen Elizabeth II died, having served the nation with duty, dignity and discretion for 70 years. An audience with the new prime minister, Liz Truss, one day; gone 48 hours later.

With her death it felt that some other cherished bits of what it means to be British had seemingly gone as well. It just all started to feel a bit unrecognisable. Yes, Gary and Match of the Day were still there in the Saturday-night schedules and Antiques Roadshow was reassuringly still part of Sunday evening. The Royal Standard would in a seamless transfer of power fly again over Buckingham Palace, but down the road at the Palace of Westminster everything had stopped working –and Big Ben was its visual symbol. But this book is not about the fabric of Britain.

If it was, I might have a few things to say. It’s probably best not to get me started, but we have gone from being a nation that was the fi rst to industrialise, to pioneer the railways, electricity, the telephone and so much more, to a country whose infrastructure is falling to bits. Just look at the highspeed rail line that looks like it is never going to be completed. The billions and billions spent with compulsory purchases of homes and land; the noble desire that economic regeneration of the North West and North East would be high-speed lines running from Manchester and Leeds, meeting in Birmingham and then going into London. When the Sunak government pulled the plug on the project it looked as though it was going to go no further north than the West Midlands – and wouldn’t actually make it all the way into London. The most expensive white elephant ever.

We’ve got more discussion about a bypass round or a tunnel underneath Stonehenge – I remember covering stories about that when I first went to work at BBC Radio Solent, 40 years ago. Best not to rush these things. Our shiny new multi-billion-pound aircraft carriers seem to break down every time they leave port, and are unable to take part in military exercises, while the army’s latest drones apparently only work in good weather. Heathrow is still waiting for its Godot-like third runway. Hammersmith Bridge in London is closed five years after a temporary two-week shutdown for repairs – which have never happened. And whatever you do, don’t fall into the River Thames below, because the

levels of E. coli in the water are dangerously high from the privatised water companies pumping sewage into our rivers and seas. The effluent society.

We’ve become a nation where ambulances queue to offload patients at A & E, and where it’s estimated 250 people each week are needlessly dying because of the long waits to be seen by an emergency doctor. It’s become a country where schools had to close at the start of term because of the discovery that the cheap concrete used in construction years earlier was likely to bring ceilings down, but where the education secretary can’t get back from abroad to deal with the crisis because the whole of the UK’s air-traffic-control system has gone offline.

This book is, I suppose, about Britishness – the values that have guided us, the behaviour we have come to expect of our politicians, the way we do things, the way we conduct ourselves in this country – and it is written from the perspective of someone who has been out of the country for a few years and can’t quite recognise what he has come back to. When I moved to the US in 2014, the coalition government had been going for four years, a bold and progressive move after the inconclusive 2010 election. The first time we had seen a proper coalition government since the wartime administration. Britain was still in its post-2012 London Olympics glow. Labour was trying to mount a fightback under Ed Miliband. David Cameron as prime minister and Nick Clegg his Liberal Democrat deputy had found a way to successfully share power and work together. Parts of it

were technocratic, even if it was underpinned by the economics of Thatcherism where that chill word ‘austerity’ would assume ever more importance. In the US, where Barack Obama was midway through his second term, it seemed that dynastic politics was about to return with the election in 2016 looking like it was going to pit another member of the Bush family against another Clinton.

By 2022, all that had changed. The Boris Johnson government, in its determination to get Brexit done, was shaking the foundations of Westminster, riding roughshod over parliamentary rules and traditions (though he is not to be held responsible for Big Ben losing its voice). The rules his government introduced to cope with the unprecedented coronavirus pandemic were being dutifully obeyed everywhere around the country, except in Downing Street, where aides would go to Tesco to load up a wheeled suitcase with booze and then go back and party. When this all came to light, the prime minister dissembled – and the bonds of trust between the governing and the governed (never that strong at the best of times) frayed worryingly. The British sensibility to laugh at ourselves and roll our eyes became something diff erent. There was anger; we suddenly became proponents of all manner of conspiracy theories. Identity politics turned poisonous. It felt as though we had seen the worst of what American politics and society could serve up and were saying, ‘I’ll have a double portion of that, please.’

And what a poisonous concoction America had produced. The Washington I left felt somehow powerless to cope with the bitter divisions that were tearing the country to pieces – and, yes, threatening to undermine US democracy itself. Being in the capital on 6 January 2021 when insurrectionists tried – and for a few hours succeeded – to stop the peaceful transfer of power to Joe Biden was shocking beyond belief. The Trump-supporting mob at Congress was seeking to stop the certification of his victory by any means, encouraged by the man still clinging on by his fingernails to power in the White House, who was unable to accept his defeat. It felt for a while that America was about to go through its second revolution: the first in 1776 to get rid of the British monarchy; the second in 2021 to get rid of democracy.

• • •

My posting to Washington as North America editor was my second stint as a foreign correspondent. I had spent four years living in Paris around the turn of the millennium, meaning that around a third of my BBC career had been spent abroad. Probably longer if you count all the trips that were just for a few days or weeks. The four years I spent in Paris from 1999 to 2003 were truly momentous. Yes, it was an interesting time in terms of Anglo-French relations. An aloof Jacques Chirac dealing with the ever-confident and, you felt, slightly grating Tony Blair. It was interesting for what was changing in France, and maybe a harbinger of other events to come. Namely the rise of the far

right and the start of populism in Europe. In the 2002 French presidential election, something unthinkable happened. It wasn’t a second round decided between the centre right and centre left, as it had always been in the history of the Fifth Republic. The far-right Front National led by Jean-Marie Le Pen beat the socialist standard bearer, the prime minister Lionel Jospin, leading to the 2002 election coming down to a contest of right versus far right. A far right which today is even more powerful. There were big domestic stories like the crash of Concorde as it took off from Charles de Gaulle airport. France proposed a ban on the import of British lamb following the outbreak of footand-mouth disease, which itself followed hot on the heels of our other unwanted agricultural export, mad cow disease.

But that is the normal bill of fare for a foreign correspondent: political upheaval, natural and unnatural disasters, the chafing of international relations. What shook the world profoundly when I was in Paris was 9/11 and the geopolitical jolt that it gave. That day I had been in Lille covering a court case to close the Sangatte refugee centre and stop the flow of illegal immigrants across the Channel (plus ça change), which was the lead item on BBC News at One O’Clock. I was to drive to Calais where I was to be the lead item on the BBC News at Six O’Clock. As we drove north, our producer in Paris rang, telling us to pull over at the nearest service station as something was unfolding in New York. At some French service station on the A25, we watched as the second plane flew into the Twin

Towers. Ours was the only other story on the news that evening, now coming right at the end of the bulletin. We continued on to Calais and edited our piece in a hotel, our eyes transfixed by the events in lower Manhattan.

In November of that year, I found myself packing my bags and body armour to fly from Paris to Delhi, from there to Dushanbe in Tajikistan, and then – after a complex journey involving bribes to a Russian general to cross a DMZ – into northern Afghanistan to move with the US- and UK-backed Northern Alliance on a front line as they sought to dislodge the Taliban from their rule. Then in early 2003, I would find myself heading to the Iraqi border as, once again, US forces, backed by British armour, were now trying to dislodge Saddam Hussein in what would become known as the ‘war on terror’.

That summer, I moved back to the UK. But despite these seismic upheavals – the huge marches against Britain’s involvement in Iraq, the dent to Tony Blair’s seeming invincibility – the country felt much the same as when I had left. Blair was still prime minister, and he would go on to win another clear majority in the 2005 general election. Leaving Iraq to one side – and if you are one of those who believe Blair should have been put on trial at The Hague for war crimes for his involvement, I know that is a big ask – the country seemed to be humming along nicely. The most successful Labour prime minister in British history was doing what he’d promised and seemed to be delivering on his pledges. Perhaps the true impact on the political

landscape was not the Conservative opposition to him, but the growing sense among a new breed of Tory politicians that they had to emulate what ‘New Labour’ had done. The much vaunted if rather elusive ‘Third Way’ seemed to be redefining politics, just as Margaret Thatcher had in the 1980s.

Ten years later, I was a foreign correspondent again. In 2014 I moved to an America that on the surface at least I thought I knew well. I had travelled to Washington on innumerable journeys, holidayed there – I’d ridden a Harley down the West Coast, for goodness’ sake. But my sense of its geography still came largely from the music I grew up with. The Beach Boys, West Coast; Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, New York; the Detroit of Motown and the Philadelphia sound of Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes. And even if I had only been to a tiny fraction of the places of Johnny Cash’s ‘I’ve Been Everywhere’, I had a sense of this vast continent.

But when I actually turned the key on the sturdy, federalstyle townhouse I would call home for the next eight years, I realised I didn’t know America at all. It was a foreign country to me. Yes, I could make myself understood. There were no language barriers. But what I thought was merely an accent change by crossing the Atlantic – swapping a plum stuck in the mouth for a sometimes lazy drawl – I would soon discover was something much more profound. I tried to chronicle just how foreign a country it is in my first book on the US, If Only They Didn’t Speak English.

Then, at the beginning of 2022, I returned to the UK – back to the city where I had grown up, London. The great thing about immersing yourself in the affairs of another country is not just that you are learning something new, but that it gives you fresh perspective on where you grew up. You have reference points. And Britain didn’t feel like the country I left. Overwhelmingly, I was delighted to be back. Yes, I would miss the ludicrous buzz of being close to the testosterone-rich (well, maybe a bit less under Biden) power that Washington, DC, specialises in. And the job at its best – travelling on Air Force One, being part of a presidential motorcade, sitting and interviewing a serving president in the White House – takes some beating. But Washington is in essence a small, provincial city which just happens to be the epicentre of global power.

There is nothing provincial about London. It is noisy, exciting, diverse, varied, beautiful, gritty. Unlike Washington, however, it is no longer the epicentre of global power – though many act as though it still is. We are a country where the nations that make up its constituent parts are asking whether it really is that great to be part of the UK. And the centre of a sprawling Commonwealth whose members are re-evaluating its worth and asking tough questions about the legacy of empire.

So, what is the Britain I have come home to? In the US I was the outsider looking in – the time-honoured job of the foreign correspondent – with all the advantages and shortcomings that brings. This is the book of an insider who’s been out but come

back in. The return of a native, if you like. Returning to the UK in some ways has been disconcerting – or maybe discombobulating would be a better word. It is, after all, my home; it is where I grew up, a country I love and am proud of. But either it’s changed, or I have. Maybe both. It just feels like a strange land.

2016 was a decisive year in so many ways – and there are two obvious dates to symbolise this extraordinary 12 months.

On 23 June, Britain voted to sever its 50-year-long marriage (which was rarely golden) with Europe in favour of ‘taking back control’. And then in November, Donald Trump became America’s 45th president.

But let’s start with a third momentous date: 2 May.

That was the day Leicester City – Leicester City, for goodness’ sake – won the English Premier League title; it was also the day when the Ohio governor, John Kasich, pulled out of the race for the Republican Party nomination – which meant that the property tycoon and US Apprentice host, Donald Trump, was, incredibly, the last man standing. A man who had never held any elective office, who had never served in the US armed forces –

some very convenient bone spurs greatly assisting his swerve of the draft – was the presumptive nominee for the GOP. The party of Lincoln, Eisenhower and Reagan was on its way to becoming the party of Trump.

I was doing a pre-recorded two-way for the Today programme that day, and Sarah Montague was the presenter in London. There was a slightly incredulous tone to her voice when she asked me, ‘But surely Donald Trump won’t become the next president?’ I replied that Leicester City were 2,000–1 outsiders at the start of the season as they competed with 19 other teams for the league title; Donald Trump would now be in a straight head-to-head race with Hillary Clinton. Of course he could win, I said. This turned out to be the year when anything could happen anywhere, and it invariably did. Over decades of reporting on politics, I had watched on numerous occasions when shiny insurgents would threaten to upend the fusty, established order with their new broom, and the alluring promise of sweeping away decades of failure. The excitement would mount – and then you would watch the British or American public go up to the edge, peer over the clifftop to the rocks and storm-tossed seas below, and sensibly take a few steps back – and politics would carry on in its conventional way.

Small, almost imperceptible political shifts were what we did, particularly on this side of the Atlantic. Who can forget the then Liberal Party leader David Steel’s puffed-up, hubristic call in Llandudno in 1981 to ‘go back to your constituencies and

prepare for government’. This had come after some long-forgotten Liberal by-election and local council wins. Labour was at war with itself and the Tories were at the height of their unpopularity with unemployment about to hit three million. The mould of British politics was being broken before our eyes; the two-party system would be confined to the non-recyclable wheelie-bin of history; Britain was about to realise its democratic potential. And then reality. Two years later Margaret Thatcher won the Conservatives a second term with – checks his notes – a majority of 144.

But in 2016, huge swathes of people walked up to the edge, clasped hands with the person next to them, closed their eyes and jumped. There had never been a year of so many Thelmas and Louises. Why? What had happened? And were the forces that drove this the same on both sides of the Atlantic?

The overlaps are obvious: many of those who had championed Brexit were big supporters of Trump, and vice versa. My abiding memory of the Republican Convention in 2016 in Cleveland, where Trump was crowned king, was walking outside the convention centre to see a circle of men and clouds of smoke rising. It’s something you just don’t see in the US. It was a knot of men, the ‘bad boys’ of Brexit, all puffing furiously on their cigarettes: Nigel Farage, Arron Banks and Andy Wigmore. And in so far as Trump supporters paid much attention to British politics, they would have probably approved of the forces driving Britain to leave the European Union.

Just after Trump won the Republican nomination that year, he flew to the UK. Not unusual in itself: a swing through the countries of key allies to show your seriousness about the major foreign policy issues and geopolitical dilemmas is what serious candidates do – Obama at the Brandenburg Gate, any number of presidential candidates paying a courtesy visit to the prime minister of the day in Downing Street – it’s perfectly normal. But Trump was less concerned about the globe than the golf ball. He came to Scotland to visit two of his golf courses. That was it.

But the day he came to the UK was significant. It was the day after the Brexit vote, and I accompanied him on this trip. I had been interviewing the former EU Commission president, José Manuel Barroso, at a private event in New York the day before – and the betting markets were saying it was 82 per cent certain that Britain would remain inside the EU. Barroso was relaxed and in a playful mood. Brexit was not going to happen, he confidently told the audience of bankers and business executives. So when I took off from Newark, New Jersey, for the flight to Glasgow, Britain was very much a part of the EU, David Cameron was firmly installed in Downing Street and the pound was rock solid against the dollar. None of those things was true when we landed in a blustery Glasgow on 24 June, and drove to one of Trump’s golf courses. He, of course, flew in a Trumpbranded helicopter. (I sometimes wondered whether Trump had a problem remembering his name, such was the number of

buildings and machines – and even golf tees – that bore his name in five huge letters.)

Trump’s first port of call was his Turnberry golf course, which had been newly refurbished. There was a nuts news conference on the ninth hole – the famous lighthouse hole – where a piper marched him to the microphone, and he was flanked by three of his children, all looking as immaculately groomed as the greens and fairways themselves. One prankster went up to Trump to hand him a box of red golf balls with black Nazi insignias on them. ‘Get him out of here,’ Trump barked to the Scottish police officers. Rather less flashily, but noteworthy in her own way, was the comedian Janey Godley, who had caught the bus to be at the course so she could unfurl her hand-written sign, with the legend TRUMP IS A CUNT on it. She too was ushered away. Greenpeace protestors buzzed the golf course in a microlight aircraft in a more serious breach of security.

The purpose of the news conference had nothing to do with the presidential election; it was a business trip. The line between Donald Trump’s personal interests, business interests and political interests was so blurry as to be impossible to see. It was all one: brand Trump. Ostensibly, he was here in Scotland so that he could go into rhapsodic overdrive about just how wonderful his golf course was after a bit of remodelling and how luxurious the Turnberry hotel was after extensive refurbishment. He wanted more than anything for the golfing authorities to reinstate the course as one of those that would host The Open, the oldest and

most prestigious tournament in the golfing world. To this day, that hasn’t happened. But Trump is nothing if not an opportunist. And Brexit Britain was waking up to the crazy reality of what it had voted for the day before.

The Brexit vote had a galvanising effect on Trump. He had entered the presidential race a year or so earlier largely as a branding exercise. The entrepreneur-cum-TV host-cum-political wannabe could see no downside from months in the headlines. He thought he would get enough funding to see him through Iowa and New Hampshire, but would then fold to throw his weight behind Chris Christie, the then governor of New Jersey. But here we were in June 2016, just over four months out from the presidential election, and it was as if a question that had been rattling around his head had just been answered: If boring, staid, risk-averse, set-in-its-ways, phlegmatic, keepcalm-and-carry-on Britain could take such a wild leap into the economic unknown, then surely swashbuckling, daring, entrepreneurial America might be willing to do just the same with a charmer like me.

At the news conference, he was clear how important a moment this was for the UK – and him! ‘I think really people see a big parallel. A lot of people are talking about that. Not only the United States but other countries. People want to take their country back. They want to have independence in a sense.’ He claimed that he had long predicted the result, though evidence is scarce to back that up.

After a short visit to his other golfing property carved into the dunes outside Aberdeen, Trump flew back to the US, and the words playing on his tightly puckered lips were those of the man he so loathed and wanted to erase from the history books – the then president, Barack Obama. Maybe his slogan ‘yes, we can’ was going to be applicable to the Trump campaign too.

If there was a single uniting policy that linked Brexit with Trump’s election victory, it was concern about immigration – no, maybe the better word is fear: fear there was an invasion underway, fear that ‘we’ were being swamped by ‘them’, fear that our identity was being erased, fear that our jobs were being taken, fear that unworthy foreigners were going to the front of the queue for housing and were overwhelming our public services.

Historically, there are important differences in American and British attitudes towards migration. The US proudly proclaims itself to be a nation of immigrants. The poem on the plinth of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, where so many people hoping to make a better life for themselves would arrive to be processed on Ellis Island, said it all: ‘Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore.’ And, staring kindly out to the ocean, Lady Liberty has been an enduring symbol for the best part of 150 years for those coming to start again in

the United States of America – a beacon of hope, independence and freedom.

One of the great experiences of travelling extensively in the US, as I was lucky enough to do, is that not only do you recognise the extraordinary geographical diversity – it is more a continent than a country – but you see the different communities from state to state. America is a melting pot. When I spent periods in New York City I don’t think I ever got a taxi driver from the same community twice. The whole world was in the city, driven by a single unifying idea that they were all Americans now in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

If you look at the names of people who come from North Dakota, every other person seems to have their roots in Norway. Like all patterns of migration, there were push and pull factors. Crop failures in the mid-nineteenth century in Norway and a series of agricultural disasters meant that thousands were in need and desperate. The push factor. The pull factor was that the US had introduced the Homestead Act in 1862, offering parcels of 160 acres of land to the adult head of a family for next to nothing in return for a commitment to farm the land for five years.

But go to other states and you’ll find different ethnic groups in different places: the Irish in New York and Massachusetts, the Germans in Pennsylvania, the Japanese in the Pacific Northwest, the Hispanic communities in the states bordering Mexico – and more recently, the Somalis in Minnesota and the Ethiopians in Washington, DC.

Around the world, people of all nationalities, from countries at different stages of economic development, had looked at the US – with its equivalent of Willy Wonka’s golden ticket, the fabled Green Card – with a sense of wonder. It was a dream. And it brought the brightest and best to the US. If you look at the list of directors of any of the Fortune 500 companies you will see the diversity of those in charge. They look very different from the boards of Mittelstand companies in Germany or, even more pronounced, the make-up of companies quoted on the Nikkei in Japan.

But in 2016, Donald Trump made clear that he didn’t much like migration – particularly immigrants from across the southern border. In the opening remarks of his presidential campaign he declared that Mexicans were thieves, drug dealers and rapists. Remarks that he would double down on. Polite society in the US gasped. Newspaper leaders tutted a disapproving rebuke. Mainstream politicians disavowed his comments. But a lot of Americans – from all walks of life – lapped it up. Trump had tapped into concerns that the southern border had become too porous. There were too many people from Mexico and the Northern Triangle of Central America (Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador) who’d crossed the Rio Grande illegally. They were not paying their taxes and should be sent packing. And thus one of Trump’s most potent slogans of the 2016 campaign was born: build the wall.

After the Islamist-inspired terror attack in San Bernardino in December 2015, which left 14 people dead, Trump would

extend his anti-immigration message to include all Muslims. He issued a statement that didn’t pull any punches: he claimed that a significant segment of the Muslim population harboured ‘great hatred towards Americans’. And he went on: ‘Without looking at the various polling data, it is obvious to anybody the hatred is beyond comprehension … where this hatred comes from and why we will have to determine. Until we are able to determine and understand this problem and the dangerous threat it poses, our country cannot be the victims of horrendous attacks by people that believe only in Jihad, and have no sense of reason or respect for human life.’ And then came the kicker – which he delightedly read out at a rally of supporters in South Carolina that evening:

‘Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.’ The original statement didn’t include the word ‘hell’. That was added with a theatrical flourish at his rally. His audience erupted in applause and delight.

There was something else that gave this even greater resonance. The San Bernardino attack played into American fears that events thousands of miles away could very easily come to US soil – like they had on 9/11. And in 2015, there was that great tide of humanity on the move, trying to escape the civil war in Syria. For the most part the mainstream US media doesn’t report much on the outside world – unless it involves American

citizens, or the pictures are captivating. The Syrian exodus fitted the latter category. That the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, admitted more than a million refugees brought admiration from many. After all, Europe’s last refugee crisis had been brought about by the country she now led following the Holocaust. Merkel was hailed for her moral and political courage by the UN refugee agency, the UNHCR.

Not so Donald Trump. He thought she’d taken total leave of her senses. And made no attempt to hide it. He called her policy ‘insane’ and a ‘disaster’. He predicted there would be riots throughout Germany.

After he became president there was an excruciating coming together between the two in the Oval Office. In the business it’s called a ‘pool spray’. It’s when the dozen or so journalists on pool duty that day (in other words you are working and filing for all news outlets, not just the one you are employed by) are ushered into the Oval Office to film the president and whoever the world leader in town is. The idea is to show rapport and bonhomie. Typically both leaders sit in armchairs, framed by the fireplace. Trump that day just showed disgust and disdain, lips pursed, hands between his knees, unwilling to shake hands with the German chancellor.

In the UK, as these seismic events were unfolding in Syria, Britain was preparing to go to the polls – the lead-up to which had seen Nigel Farage’s anti-Europe and anti-migration party, UKIP, sweep the board in the 2014 European Parliament elections

– the first time in modern history that an election hadn’t been won by either Labour or Conservatives. Mind you, European elections have nothing like the turnout that you get in a general election; the voting system is not first-past-the-post as you get in UK general elections; these elections are historically a chance to blow a raspberry at the ruling party at Westminster. There was little chance that UKIP in a general election would win more than a handful of seats.

Though he wasn’t an MP (he had tried a number of times and failed), Nigel Farage was a massively influential figure in the events that would unfold. He is a sort of Pied Piper figure, where his blokeish, hail-fellow-well-met mien reached parts of the British electorate that conventional politicians failed to get close to. His mustard corduroys, tweed jackets and a politically incorrect Rothmans cigarette hanging from his mouth with a pint of ale in his hand made him an endearing ‘everyman’. The reality of Farage as the quintessential ‘ordinary geezer’ does not bear close scrutiny. The son of a stockbroker, he attended the elite private school Dulwich College, where his flirtation with far-right politics began. And from there he went into the City too.

The author and broadcaster Michael Crick reported for Channel 4 on the concern that Dulwich College teachers had about the teenage Farage, quoting this correspondence between staff members at the school: ‘Another colleague, who teaches the boy, described his publicly professed racist and neo-fascist views; and he cited a particular incident in which Farage was

so offensive to a boy in his set, that he had to be removed from the lesson. This master stated his view that this behaviour was precisely why the boy should not be made a prefect. Yet another colleague described how, at a Combined Cadet Force (CCF) camp organised by the college, Farage and others had marched through a quiet Sussex village very late at night shouting Hitleryouth songs.’

When Nigel Farage was shown the correspondence, he admitted to being a ‘troublemaker’ at school who ‘wound people up’: ‘Of course I said some ridiculous things, not necessarily racist things. It depends on how you define it.’ He denied knowing any Hitler-youth songs ‘in English or German’.

The fully formed Farage became a much subtler and more effective operator who, like Donald Trump, would get away with saying the kind of things eschewed by mainstream politicians. He was the master of the dog-whistle. And though in reality he was pretty much a one-man political party, his brilliance as a communicator and, yes, the resonance of his anti-European message put the fear of bejesus into the Conservative Party.

Such was the mood of panic UKIP induced at the top of the party that David Cameron, the leader of the coalition government, felt that he had to restate an earlier promise he’d made to his party that the British people would be given an in/out referendum on leaving the EU if – if – the Tories won an overall majority at the general election due in 2015. He thought it was a clever piece of political manoeuvring; canny internal party

management. There was little expectation that Cameron’s Tory Party would win an overall majority, so he was making a promise that in all likelihood he would never have to make good on. It would appease the Eurosceptic right-wing faction in his party in Parliament, a much more sizeable number of the wider membership, and it would be a nod to the electorate as a whole that he got the message over why so many had voted for UKIP in the Euro elections. Cameron had gambled and won already. He’d seen off the referendum to change the voting system in 2011 by a whopping margin. And if not quite so emphatically, the Union had held together in the Scottish independence referendum in 2014. So, rolling the dice once more – this time on our relationship with the EU – seemed no big deal. He was on a gambler’s lucky streak. What could possibly go wrong?

The task for the Eurosceptics – and indeed the Trump campaign in the US – was made somewhat easier by the chariness of many more liberal-minded politicians to talk about the issue of immigration. They were hoping it was a live rail they wouldn’t need to grasp. Policymakers knew that as a society aged and got wealthier there were many jobs that were not going to be filled by the domestic population.

How many Britons are prepared to fruit-pick in East Anglia? How many Britons are willing to work in our care homes or take the lower-paid jobs in the NHS? On our building sites, how many of the workforce were born in the UK? Free movement within the EU did bring many, many people to these shores – but