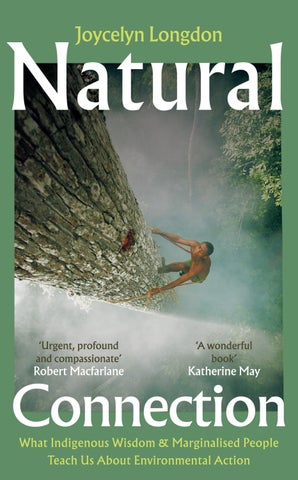

Joycelyn Longdon

‘Urgent, profound and compassionate’

Robert Macfarlane

‘A wonderful book’

Katherine May

‘Urgent, profound and compassionate’

Robert Macfarlane

‘A wonderful book’

Katherine May

Square Peg, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Square Peg in 2025

Copyright © Joycelyn Longdon 2025

Joycelyn Longdon has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.6/ 15.8pt Calluna by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 y H68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISB n 9781529902662

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Every forest branch moves differently in the breeze, but as they sway, they connect at the roots.

416 million years ago, a new kind of life began to scramble its way out of the depths of the ocean and the shallows of Earth’s wetlands. It slipped, and slimed, and grasped and gasped, dragging itself onto land. Unlike its rootless, leafless predecessors who floated on the surface, this new life broke open the hard, encrusted clay of the Earth and planted itself deep into the soil, creating new subterranean connections. It was during this time, the Devonian period, that rooted life was quietly setting the stage for a revolution that would change everything – a time in our geological history commonly known as the ‘age of the fishes’, when the ocean covered around 85 per cent of the Earth, and North America, Greenland and Europe were joined as a single land mass.1 After 30 to 40 million years of taking root on land, settling in, the ancestors of modern trees, such as conifers, palms and horsetails, came into being.2, 3

We often perceive roots as grounding, life-giving, nurturing forces. They are sacred and medicinal, essential to life on this planet. The arrival of rooted life on land poured oxygen into the skies, supporting the flourishing of new terrestrial life forms, but also contributing to the mass death of marine life.4 The late Devonian period saw pulses of mass extinction, with almost 70 per cent of all marine species wiped out.5 Various theories have sought to explain these extinctions. Some believe glaciation and the subsequent lowering of the global sea level to be the trigger – others point to meteorite impacts.6 But in two separate studies – from the universities of Cincinnati and Indiana respectively – researchers point to the establishment of tree

and plant roots.7 Their work describes how as the newly formed roots descended into the Earth, they splintered, shattered and fragmented rocks, exposing the previously compacted soil to weathering and erosion and, importantly, triggering the release of nutrients, which were deposited into the world’s waterways. The study from Indiana University found spikes of nutrients, predominantly phosphorus, in geochemical records, which catalysed the process of eutrophication, causing algal blooms – the excessive and accelerated growth of algae – that suffocated and killed off vast swathes of marine life.8 Roots, often imagined as lifebringers, brought both abundance and loss in the beginning. It was left up to evolution to nurture new roots and to bring the descendants of this rooted life back into balance in order to regenerate the now depleted phosphorus levels. As is expected, especially with research looking back in time, opinions are still divided on the true cause of the Devonian extinctions. Regardless, an important lesson emerges for our current moment, one which fills me with hope and motivation. The survival of life on this planet depends on the roots that we nurture and that take hold, the roots we allow to run rampant, and the roots we restrict or redirect. In times of destruction, we must answer the call to intentionally plant new roots of balance and regeneration.

The world as we know it is ending, and a new one prepares to be born. We are living through the transition – a transition that is tumultuous and demanding, inflicting and requiring radical change at the same time. With the knowledge that the word ‘radical’ is born from radix, the Latin word for root, we find that our survival through this radical time, as Patty Krawec from Lac Seul First Nation notes, ‘depends on what our roots sink into, wrap around, and bring to the surface’.1 The destruction we are witnessing unfolding around us can be traced to the violent, oppressive and dying roots of colonialism and late-stage capitalism: to centuries of domination over the land and those most vulnerable or marginalised. Our roots – the cultural, historical, physical and spiritual connections we have with each other and the rest of the living world – have the potential to lead us to pain and suffering, but they can also transport us to the thriving futures we envisage. We must unearth and tend to the roots that will hold us steadfast through the chaos – ideas and ways of living preserved by communities intimately connected to the land and the effects of environmental destruction: ancient, creative, caring and innovative roots that are waiting to be remembered and nurtured. Roots that remind us of our place in and relationship with the living world.

Often, as a Black woman and environmentalist living in the West, I encounter individuals whose lives have not been touched by environmental disaster or oppression but who have already admitted defeat. Unable to imagine the world outside its current extractive and destructive systems, they are resigned to apathy and inaction. When I compare this

with the ingenuity, dynamism and endurance of frontline communities – those facing the worst climate and environmental impacts, creating beautiful movements in spite of bleak, distressing and traumatic pasts and presents – it becomes clearer than ever that the future cannot be built without the experiences and solutions of marginalised and Indigenous communities, supported by a strong coalition of allies. Communities who, though often neglected from mainstream environmental narratives, through their wisdom and suffering have built a ‘natural connection’ with the living world. Not a racist or paternalistic image of a romantic, docile, idealised connection with nature. Not the imagined harmony of lives spent frolicking through meadows and communing with trees with no technology in sight. Don’t get me wrong, I love a good frolic and I try to visit the magical willow that lives in my local nature reserve as often as I can, but possessing a natural connection with the living world is not a connection based on proximity to ‘natural spaces’ or the ability to subsist completely off the land. What you will find throughout the stories in this book is that the connection Indigenous and marginalised communities have with the living world is raw, messy, emotional and complicated. It is pain and it is duty; it is honour and it is knowing. What emerges through this thicket of love and loss is a connection to the living world that is rooted in the intimate knowledge that we only have each other and the Earth itself. A natural connection is simply the recognition of environmental action as our steadfast commitment to proudly take our place as beings within, not above or outside of, the planet’s astoundingly diverse ecosystem. To plant strong roots in our communities and within the Earth: to build better futures. This connection can be found in all places, wherever our hearts and minds

are open and receptive. It exists in the city as much as in the country, for everyone, regardless of whether you work in an office or with the soil. The stories shared in these pages show us that no matter how insignificant we feel, our actions matter, and even ‘small’ movements have the power to irrevocably impact and change our worlds for the better. My hope is that they illuminate the capacity and power that each of you possesses to craft a natural connection with the world too.

This book is the result of my years-long journey exploring and celebrating the diverse roots of environmentalism, and my quest to share these stories with the world, to inspire and bring about positive and lasting change. Growing up in the Western world, holding that identity in tandem with my identity as a member of the Ghanaian diaspora and as a Black woman while working between the UK and Ghana, fundamentally influences way I view the world, our connection to it and to each other. I have witnessed and experienced the tools of oppression, exploitation and domination. I have seen the ways they wreak havoc on our ecosystems and the people who live within them. And I have, with decreasing surprise, seen how they manifest in the ways we interact with environmental action and build movements of change. But I have also had the privilege of witnessing the beauty, and learning the necessity, of dynamism – of openness, of interconnection. Extraction and oppression are not acts unique to the Western world – I have been exposed, albeit much less frequently, to corruption and lack of care in the Global South too – but they lie at the root of Western domination over people and planet. Here, and in all other instances in this book, I follow Milan and Treré’s definition of the ‘South’ where, ‘the South is . . . not merely a geographical or geopolitical marker but a plural

I on entity subsuming also the different, the underprivileged, the alternative, the resistant and the invisible’.2

What the intersecting crises we are now witnessing provide us with is an invaluable opportunity to unearth and resist these acts. Throughout this book, I hope to offer a series of alternatives. My aim is to leave you as transformed as I have been by the histories that precede us, to find a new and grounded view of your relation to the world, and the power you have to reshape it.

I have always been deeply drawn to understanding our place in the world, the impact of the past on our present and the ways in which we can affect the future. My journey started by looking to the skies, studying astrophysics for my first degree. Then, in 2020, I turned to the ground, embarking on a PhD at the University of Cambridge, exploring the role of technology in forest conservation and the resulting impacts on marginalised communities. In the same year, I founded ClimateInColour, an award-winning education platform for the climate curious that makes climate conversations more accessible, diverse and hopeful. In that first year, I researched, wrote and launched ClimateInColour’s first educational course, entitled ‘The Colonial History of Climate’, which explored the interconnectedness of climate science, environmental breakdown and European imperialism. It was a response to the lack of awareness of the colonial origins of the climate crisis, highlighting the ways in which empire and Western philosophy seeded the systems of oppression and extraction at the root of the intersecting environmental and social crises today. From the creation of botanical gardens in India as a strategy to

cultivate and profit from crops in unfamiliar climates to pushing out Indigenous knowledge, science and practices of nurturing the land, the colonial era is the prototype for today’s environmental and cultural destruction. More than 500 years after the start of this violent process (which most mark as the 1500s), there is, in the twenty-first century, a real hunger for this information.3 Hundreds of people signed up to take part in these sessions of collective learning, remembering and connection. Together, we traced the paths of climate colonialism all the way to the present day, revealing the ways in which Western worldviews perpetuate and have intensified our disconnection from the living world. Throughout the course, I told the stories that the mainstream environmental movement was too afraid or unwilling to amplify. Stories that, one by one, brush away the dirt that conceals the roots of Western environmentalism: roots that have cultivated a deeply individualistic and exclusionary movement.

Straddling the worlds of activism, academia, conservation, education and the arts, I have connected with a wide range of conscientious, deeply dedicated and creative individuals. People, at various stages of their journeys to environmental action, whose hearts have been torn apart by the collapse they are witnessing, who are in search of community, purpose, faith: in search of roots that will hold them and guide them through this time of collective grief. Many of them have shared with me their pain and fear, their experiences of distance and disconnection in environmental spaces, and it’s likely that those of you reading who have never interacted with ClimateInColour before have had similar experiences. You too are stung by the gatekeeping and the expectation, the demand, for self-sacrifice. The lack of tolerance for diversity of thought, identity

and lived experience. You twist yourself into awkward and uncomfortable shapes, in the hope that you will be accepted, crowned as sitting on the ‘right side’ of history. You watch on as the urgency of the climate and environmental crises pushes activists, scientists and campaigners further into disconnected, draining and demanding lifestyles; they are left burnt out, having exhausted their mental and physical resources and capacity for care in their fight for a better world. You have been shocked to learn how forms of Western environmentalism have grown from the same roots as environmental destruction and systems of oppression. You are saddened by the Western ideals of purity and perfectionism that underpinned the eradication of Indigenous peoples from their lands to reinstate the ‘pristine’ wilderness, and that are seen mirrored in the contemporary practice of militarised, fortress conservation that sees Indigenous and local communities pushed out of their ancestral homes. You are exhausted by the era of late-stage capitalism that saps from you every last drop of energy, and that tries to harden and isolate you. You are witnessing the uprooting of community and the living world at the hands of colonial, capitalistic and monocultural systems: systems that erode our collective resilience in the face of ongoing disaster – systems from which we must become untethered. You are craving community, compassion, freedom and purpose, the ability to hold and be held and feel safe. You may not yet have realised, or want to acknowledge, that you feel these things, but deep down, in our own unique ways, we are all craving a natural connection.

In this book, I will explore six alternative roots we can grow to create a natural connection between ourselves and the living world. These roots represent practices, teachings and considerations for environmental action inspired by the legacies and ongoing resistance of marginalised communities that transcend Western ideas of what we must do or who we must be to effect positive and impactful change. We will explore, together, how rooting in RAGE is a necessary response to systems of oppression but impedes progress without being transformed into action. We will discover how cultivating radical IMAGINATION allows us to resist the logics of colonialism and capitalism that keep us from building visions of more just futures. We will witness how environmental INNOVATION can and must place the wisdom of nature and cultures, past and present, at its core and how THEORY is a way of building collective wisdom to seed collective liberation. The final chapters lead us to new understandings of our connection with the living world and each other, seeing HEALING as a process of recognising our collective grief as an opening for transformation, and cultivating a universal ethic of CARE by making kin. These chapters, the stories held within them and the lessons they offer, show us how we might move towards a world filled with abundance and safety for all beings.

This is not a book of instructions or demands; it is not a catalogue of climate solutions, although there are many, ancient and modern, held within these pages. It is not a toolkit for environmentalists nor a prescription of the roles and actions you must take, as if environmental action were a mere case of ticking off a checklist. This is a book about acknowledging and deeply embodying your existence as a being who is but one strand woven into the

infinite tapestry of the living world. It asks how you might see environmentalism not as a hobby, career or chore, not only as an act of doing, but also as a way of being in the world. Reconnecting to why and how you exist rather than who you think you should be or what you think you should be doing. This book asks you to release yourself from the stereotypes, the guilt, the ego, the exclusion and the burnout, and move towards radical and honest selfexpression and discovery. It asks you to treat environmentalism as the big and small, visible and invisible, ways in which you live and act out your deep love and care for others and the planet.

Through the voices, stories and histories of those who have revolutionised the landscape of environmentalism, each chapter uncovers the richness and diversity of approaches to environmental action pioneered by marginalised communities. Many of the stories held within these pages hail not from popular mainstream media, which focus on often white and Western environmentalists. Rather, they amplify the experiences, triumphs and perspectives of the Global Majority – a phrase coined by Rosemary Campbell-Stephens MBE to describe ‘people who are Black, Asian, Brown, dual- heritage, indigenous to the global south, and or have been racialised as “ethnic minorities” in the West’.4 These are the stories of the AfroIndigenous Brazilian quilombo resisters finding roots in rage against environmental degradation of their ancestral lands; of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 9 in Nigeria, who stood up and lost their lives in the fight against environmental destruction by fossil fuel giants like Shell, and the women of Uttar Pradesh’s Chamoli district, who mobilised and catalysed a movement of non- violent protests by hugging trees. Stories of the team at Forensic

Architecture finding roots in theory to repatriate the cemeteries of enslaved people in the face of petrochemical extraction and destruction, and of Muthoni Masinde, the Kenyan computer scientist using technology and Indigenous knowledge to solve drought issues for rural farmers. We will explore the technologists finding roots in innovation , collaborating with Indigenous African communities to build climate-resilient homes from the clay of the Earth, and creatives like Fehinti Balogun finding roots in imagination , using theatre to communicate compelling climate stories. We will hear from those finding roots in healing , like transdisciplinary artist and educator brontë velez, who is leading the return to love through spiritual and traditional community reconnection; and from Indigenous leaders like Rarámuri scholar Enrique Salmón who find roots in care by fostering a radical intimacy and familiarity with the living world. These stories are complemented by a beautiful constellation of conversations I was fortunate enough to have with writers, philosophers, environmentalists and change- makers who have inspired my own work. These conversations respond to the stories held within each chapter, providing reflections to help us contextualise each root. In the section on RAGE , the Nigerian ecofeminist and climate justice activist Adenike Oladosu teaches us that anger is a natural response to systems of oppression. In IMAGINATION , acclaimed writer Robert Macfarlane teaches us that imagination untethered from Western philosophical thought leads us to a knowing – deep in our bones – that the living world is alive. Reflecting on INNOVATION , designer and expert on Indigenous nature- based technologies Julia Watson teaches us that Indigenous knowledge and narratives are

essential in building rooted technologies. In the section on THEORY , Miranda Lowe, principal curator and scientist at the Natural History Museum, London, reminds us that theory is not something created by scholars in the ivory tower, but knowledge already held, and lived through, by marginalised communities. From the transcendent philosopher and activist Báyò Akómoláfé, we learn that HEALING is reimagining wounds as portals – openings to new ways of seeing, living and being. In CARE , bestselling author Katherine May makes clear that care is political, and that we must reject the weaponisation of care as an exercising of power. In the epilogue, ROOTED HOPE, esteemed writer Rebecca Solnit teaches us that, in the midst of environmental breakdown, we can feel terrible and yet remain committed, be heartbroken yet know that the future is being made in the present. This book is an offering and, through it, I hope to rekindle your sense of awe, wonder and connection with the living world, the histories of those who came before us and the stories of those who will shape the world for the better in the future. Take these stories: inhale them, be moved, enraged, excited and energised by them, and let them help you nurture a natural connection with the world.

Think back to the first time you felt compelled to engage in environmental action, whether that looked like following an environmentalist or activist organisation on social media, joining your company or institution’s sustainability team or society, switching your bank to one that doesn’t invest in fossil fuels or seeking out local environmental initiatives. What was it that compelled you to act? What emotions were bubbling under the surface? Was it fear, frustration, hope, sadness, guilt, loneliness or helplessness? For many, at the centre of these emotions lies rage. Pure, hot, white rage. In his book Earth Emotions, the philosopher Glenn Albrecht explores the range of emotions that arise within us in response to environmental breakdown. Of the seventeen new terms he coined, terrafurie describes the shared, extreme anger felt by those who witness the devastation around them and either feel unable to change the direction of that destruction or aim that anger towards challenging the status quo and holding the leaders of the damage to account.1 In the face of environmental ruin at the hands of extractive, profit-led, consumption-driven practices, and human and non-human loss of life, there seems to be no other rational emotion to feel. The role of anger in social movements is increasingly being researched, with some studies finding ‘eco-anger’ to be ‘uniquely associated with greater engagement in both personal and collective pro- climate behaviours’.2 Reflecting on her own motivation for action, in an interview with the Guardian, youth climate activist Noga Levy-Rapoport, who led the 2019 London climate strikes, noted that the anger she and fellow young climate activists were experiencing was what took them to the streets

in the first place – ‘we’re marching on the streets because we are furious – we are full of rage and terror’.3 At the time of writing, the most recent study, conducted by Norwegian researchers, found that anger was the most effective emotion in motivating people to get involved with systemic change and highlighted the links between anger and collective action. 4 Another related study observed similar outcomes, finding that experiences or perceptions of injustice that ‘provoke group- based anger’ catalyse collective rather than individual action.5 Given that we need to enact radical changes both as individuals and as a society – the dismantling of systems of oppression is just as important as reducing our own personal contributions to the climate crisis – it would seem that the angry activist trope represents one of the most impactful approaches to inspire environmental action.

Often, the rage that activists feel or express is used against them, especially in the media. Used to discount or invalidate the motivations or objectives of their action. Used to brand them as ‘dangerous radicals’, as acknowledged in the impassioned speech, on the launch of the third IPCC report, of UN Secretary General António Guterres. Anger is an emotion laden with negative connotations, most commonly aggression, blame, hysteria and violence – perceptions rooted in racism and misogyny. In a passionate and sharp essay entitled ‘The Case for Climate Rage’, the award-winning journalist Amy Westervelt reflects on her own infuriating experiences of being silenced and invalidated by male colleagues as a reaction to her ‘emotional’ responses to climate breakdown. She observes how, even in storytelling workplaces, where the goal is to communicate more than just the science, where sadness, hope, humour and even alarm are encouraged,

17 climate stories can ‘never be too emotional . . . and especially not angry’. Rage and anger are seen to be in complete opposition to intellect and rationality. We shield our eyes from expressions of anger, confronted by and embarrassed on behalf of those – especially women and people of colour, and particularly Black women – who run about us, naked, their hearts all exposed. Instead of matching their bravery, letting their power light fires within our own hearts, we routinely stay quiet, too afraid to let emotion lead. Aristotle once said that passions are ‘dangerous roadblocks on the path to becoming fully human’; the anger of the ‘masculine’ – playing out through war, violence and extraction – is accepted and tolerated, whilst the anger of the ‘other’, the not- quite- human, is derided and invalidated.6 At the close of her essay, Westervelt acknowledges how the branding of rage as shameful lies counter to what we know about climate injustice and the heart-wrenching ways the least responsible have become the most impacted; she makes clear that ‘the story of climate change, both its history and its future, needs to be told by people who have already experienced injustice and disempowerment, people who are justifiably angry at the way the system works’. Having engaged in racial justice activism in my teens and early twenties, witnessing the senseless killing of members of my community in the UK and abroad, and experiencing soul-crushing racism and misogyny myself, I felt all too keenly the burning hot coal of injustice, the scorching of deep anger that sits heavy in the stomach. But as a Black woman, often existing in spaces that require a flattening of emotions – where outbursts, expressions of dissatisfaction, critique and frustration are immediately coded as aggressive, where you are expected to sit quietly in the face of oppression – I have often suppressed my feelings

of rage. This is not an act unique to me. I come from a long line and broad community of Black women for whom abandoning the self, quieting the growing storm within, is a strategy for survival, physically, mentally and socially. I speak here with the specificity of the Black experience, not to negate the experiences of silencing that most, if not all, women around the world face, but to talk about my own community and the distinct challenges they face as women withstanding sexism as well as racism. The foregrounding of the struggle of Black women is an essential part of intersectional feminism, which was pioneered by Black women thinkers such as Angela Davis, Roxane Gay, Audre Lorde, Kimberlé Crenshaw (who coined the phrase), and more recently Bernardine Evaristo. I use the intersectional lens to make space for the nuanced way different forms of oppression are layered on us depending on who we are and where we come from so that our shared experiences don’t overshadow the ones we don’t all share in the same way. But, for all of us, there’s a lot to be mad about.

Like racism and sexism, environmental breakdown is a form of oppression inflicted primarily by the elite and those in the Global North. It’s something to be mad about. Accelerating species loss and extinction is something to be mad about. Worsening air quality, especially in the poorest areas, is something to be mad about. Increasingly severe climate disasters, hurricanes, floods, forest fires are things to be mad about. We have a lot to be mad about and as long as our bodies tremble and hearts ache, we must resist the forces that manipulate and control, pushing us further away from that madness. Yet, the response to public demonstrations of rage from environmental activist groups, like Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil, in Britain highlight how divisive rage has become. When activists transform their

anger into action, interrupting a popular theatre production and calling out the theatre’s ties to fossil fuel destruction, they are taunted and heckled. Vitriol is spewed in their faces for loving the arts so much that they cannot bear to see it covered, metaphorically, in oil. Or when their anger moves them to lie in the road – a tactic that we will later see stems from the dawn of the environmental justice movement, led by Black communities in America – they are ripped apart by the media and, in some instances, physically abused by their fellow citizens.7 Recent reports have found that 80 per cent of the British public are concerned about climate change, and chances are, most of them feel angry about it. Yet, with the help of the British media, we have been conditioned to characterise anger in response to injustice as unacceptable, and anger in response to rage about injustice as natural. There’s a tension here, one that many of us feel and that has been discussed in numerous video essays on social media. As someone who engages with direct protest as part of my personal activism, I understand the frustration of watching people you love, your neighbours, your city, seemingly unphased by destruction and exploitation. Watching people argue over the dinner table, in the comment sections on social media or on the TV about how bad things are and how we are doomed yet refuse to openly perform this rage where it feels it counts – the streets. There also exists an equal level of frustration from people who feel and have witnessed how, at times, being out on the streets is more about telling and showing the world you care – often with a sense of superiority over others – rather than truly calling for transformation. With many of us already so disenfranchised by our social systems and governments, it’s hard not to feel that public displays of rage are pointless – that they change nothing. In a world where we are more and more

disconnected from our communities and ever more polarised, we take out the rage triggered by intense feelings of lack of agency and power on each other instead of channelling it into transformation. Instead of using our anger to advocate for change, we are trapped in cycles of collective conflict; we forget that without radical action, much bigger disruptions with much more devastating outcomes will befall us, hurting those of us most vulnerable and marginalised in the UK and globally. All the while, those in power continue exploiting us all. What we fail to see, as a collective, is that our rage is a valuable resource. As Audre Lorde says, our ‘well-stocked arsenal of anger [is] potentially useful against oppressions . . . focused with precision, it can become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change’.8 In this quote, there are two important words: ‘potentially’ and ‘precision’. Earlier, I reflected on my difficulties in embracing rage in my own environmentalism. It was not rage, the feeling itself, that I was weary of, but rather the consequences of misguided, righteous, shaming, blaming rage. Rage that is disjointed from dreams of harmony and visions of connection. Rage that harms and hurts. Rage that perpetuates the capitalist and colonial behaviours of using, exhausting and devaluing others. Rage is a fire. A fire that can enlighten and warm yet burn and destroy in equal measure. Lorde reminds us of the ‘potential’ of rage to catalyse positive change, emphasising that this is not a given but something that requires care, thought and intention. We must be ‘precise’: in the ways we channel our rage, who we inflict it upon and with the visions of liberation that underlie the transformation of that rage into action.

When I trace the marks of anger that embroider my heart, I find that they lead to devastation. My anger comes from a place of loss, a place of despair. Thinking back to one

of the early rally cries of Extinction Rebellion – love and rage – it is obvious to me that so much of my anger stems from and is imbued with the deep affection I have for our planet.9 It is our love for and dismay at the destruction of the living world that must lie at the core of our rage, our terrafurie. Writer and activist adrienne maree brown in her article on ‘how the wonder of nature can inspire social justice activism’, explores the perspectives of different organisers, facilitators and artists who were leading transformation around the world.10 Whilst reading it, I was struck by the contribution from reproductive rights organiser Jasmine Burnett, who wrote about ‘devastation as a source of liberation’. These words encouraged me to reconsider the way I thought about how anger manifests in organising, protest and direct action. These words made clear to me that the rage that boils within us when we are confronted by destruction is the very thing we need to achieve collective liberation.11 So how do we go about harnessing and focusing our collective rage? How do we reject corrosive, soul-sucking, competitive manifestations of fury and cultivate energising, purpose-holding rage that is not suppressed or left festering in the stomachs of individuals but tended to and transformed by community into action? The answers to these questions lie in the forests, oil fields and towns of communities past and present, fighting and struggling for their nonhuman kin, the land and themselves. This section is about how rage has been and can be harnessed and transformed to move from a place of destruction to liberation. In the next chapter, we will travel back in time to North Carolina in the 1970s. We will meet the Warren Country community and learn, through their story, how rage – held collectively – shaped actions that would mark the dawn of the environmental justice movement.

As a born and bred Londoner, growing up just 5 miles away from Heathrow Airport, I can think of a few examples that show how the transformation of anger into action plays out in city landscapes. London is a city choking on a thick, heavy and persistent cloud of air pollution; a dizzyingly hazardous soup of carbon monoxide, ozone, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter, the latter two of which exist in quantities so large that they pose a public health emergency, as they cause respiratory and cardiac illnesses, skin irritation, metabolic disorders as well as neurological and reproductive issues.1, 2 This veil of pollution hangs heaviest in the skies over predominantly Black and South Asian communities. Contributing to more than 9,400 deaths a year, air pollution was responsible for the tragic loss of life of nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah from South London, the first person in the UK for whom air pollution was identified as the cause of death.3 Ella’s death, on 15 February 2013, devastated the Black community, who knew all too well that her death was a result of intersecting and compounding injustices: Ella suffered from asthma, a condition that causes 50 per cent of the hospital admissions originating in children from Black and Brown communities.4 In August 2020, as a response to this enraging reality, three Black and Brown sixth formers from London – Anjali Raman-Middleton, Nyeleti Brauer-Maxaiea and Destiny Boka-Batesa – who attended primary school with Ella, came together to form the charity Choked Up.5 They were tired of their voices being side- lined and ‘outraged that

the people most at risk of the health impacts of air pollution were people of colour and working-class communities’.6 Using artful, creative and direct guerrilla campaigns in heavily affected areas, they turned their anger and devastation into action. In April 2021, they installed fake but realistic ‘POLLUTION ZONE ’ road signs that warned that ‘Breathing Kills’. They also demanded that Sadiq Khan, London’s mayor, enshrine the right to breathe clean air in UK law through a new Clean Air Act. The campaign, still ongoing, has been a success, with its first three asks being acted upon. This has resulted in

1. a fining policy for red routes, which make up 5 per cent of London’s roads but account for 30 per cent of the city’s traffic;7

2. an expanded Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ ), which by the end of 2022, a year after the expansion, saw nitrogen dioxide levels decrease by 46 per cent and carbon monoxide levels reduce by 22 per cent; and

3. an acceleration in the rollout of zero-emission buses with the launch date moved up from 2037 to 2034.8

The work of Choked Up is essential, as it directly addresses the systems of oppression that have resulted in redlining in London and that have become commonplace across the UK , US and beyond. Redlining refers to the ongoing process of racial segregation that drives the isolation of marginalised communities into housing projects exposed to poor environmental standards in order to reserve more liveable environments for white and middle- class communities. 9 The roots of the term come from the literal red lines drawn on maps around areas that housed Black

communities by government officials. These areas would be completely shaded in red, even if only one Black person was living in the area, and would be marked as low value in terms of house prices.10 The term has evolved to describe these often covert acts of segregation where communities are marginalised by race, exposing them to lower living standards and quality of life. The legacy of redlining is a long one, but so is the tradition of environmental justice activism. The campaigning by Anjali, Nyeleti and Destiny carries forward the work of generations of activists who resisted harmful segregational policies.

One of the most famous examples of such activism was the PCB resistance in Warren County, North Carolina in the late 1970s. Over three months in the summer of 1978, concealed by the dark of night, a team of men working for the Ward Transformer Company transported an estimated 31,000 gallons of toxic transformer oil along 240 miles of North Carolina roadways.11 The transformer oil was infused with dangerous chemicals like dioxin, dibenzofurans and, most famously, large quantities of polychlorinated biphenyls ( PCB s). As planned by Ward, who had counted on the absorptive nature of the local soil, the chemicals drained into the surrounding lakes, farmland, and even the groundwater across fourteen counties in the state.12 Just a year prior, the US Environmental Protection Agency had advocated for a ban on the PCB s that were known to cause cancer, in addition to having many other harmful effects.13 While Ward Transformer Company was held to some level of account, sued by the state of North Carolina for damages, the toxic chemicals remained in the ground wreaking havoc on social and environmental health. Far from serving justice to its people, the state came up with a clean-up plan that would threaten the lives of the most