The English House DAN CRUICKSHANK

A History in Eight Buildings

The English House

Also by Dan Cruickshank

Around the World in 80 Treasures

Dan Cruikshank’s Adventures in Architecture

The Secret History of Georgian London

Bridges: Heroic Designs That Changed the World

The Country House Revealed: A Secret History of the British Ancestral Home

Brick (with William Hall)

A History of Architecture in 100 Buildings

Spitalfields: The History of a Nation in a Handful of Streets

Skyscraper

Cruickshank’s London: A Portrait of a City in 13 Walks

Built in Chelsea: Two Millennia of Architecture and Townscape

Soho: A Street Guide to Soho’s History, Architecture and People

The English House

A History in Eight Buildings

Dan Cruickshank

HUTCHINSON HEINEMANN

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Hutchinson Heinemann is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Dan Cruickshank, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 11.5/15.5pt Adobe Caslon Pro Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–1–529–15245–6

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

In memory of my friend Andrew Saint November 1946 – July 2025

Contents

Preface ix

Introduction xi

1. Architects and Patrons 1 Pallant House, Chichester (1712)

2. A Home for Immigrants 33 19 Princelet Street, Spitalfields (1718)

3. A House Built by Connoisseurs 79 Maister House, Hull (1743–c.1760)

4. A Piece of Urban Theatre 121 Heywood’s House and Bank, Liverpool (1798–1800)

5. A Question of Style 155 Cragside, Northumberland (1869–95)

6. The Two- up Two- down 205 Toxteth Bye-law Houses (c.1860–c.1890)

7. The Birth of the Council Flat 247 The Boundary Estate, Shoreditch (1890–1900)

8. The First ‘Modern’ House 303 New Ways, Northampton (1925–6)

Preface

This book explores the manner in which buildings are made − the relationship between clients, surveyors, architects, building tradesmen and all involved in the architectural process. At the same time, it examines the ways in which buildings were used, and the social and aesthetic statements their creators intended them to make. The former ambition is not an easy one to realise, in part because contemporary documentation is often scanty, in part because the role of those involved in the process of design and construction varied from building to building and also evolved over time. The latter ambition also poses challenges of perception and interpretation. The task is nevertheless a rewarding one: delving beneath the veneer of style and fashion to unravel the story of how houses were conceived and built, combined with placing them fully in the context of their age, offers an opportunity for familiar buildings − or, at least, a familiar type of building − to be seen in a new way.

Many people have helped me tell this story. I cannot mention them all, but I must name a few:

Richard Harris for information about Bayleaf Farmstead, and for his drawing of its timber-frame structure; Simon Martin and, from Alan Baxter Limited, Richard Pollard, Vicky Simon and Heloise Palin for information and assistance on Pallant House; The Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust and Rachel Lichtenstein for 19 Princelet Street; David Neave and the National Trust for Maister House, Hull; Andrew Saint for Norman Shaw and Cragside, and Gareth Carr for Toxteth and the Welsh Streets.

From the publishers, Nigel Wilcockson, who commissioned this book and has overseen its production – many thanks; and Joanna Taylor, Caroline Pretty and Hannah White-Steele for their great help in refining the text and gathering the images. x Preface

Introduction

On Steep Hill in Lincoln – a street of Roman origin1 that leads up from the lower city to the spectacular eleventh- and twelfth- century cathedral – stands one of the oldest houses in England.2

The Steep Hill house is said to date from around 11703 and has long been known as the ‘Jew’s House’. Judging from what survives of the original front, it was clearly conceived not as a simple vernacular building but as a considered work of architecture. The house, while gnarled by age, remains very handsome. It is built of local limestone, cut into roughly squared blocks, with those forming the front laid smartly in horizontal courses that differ slightly from one another in depth. This gives the facade as a whole a sense of order, while also the charm that comes with gentle irregularity. Remnants of round arched windows set within larger semicircular relieving arches – all enriched with carved ornament – survive, as does a now-decayed, ornamented semicircular arch over the front door. Such motifs are typical of Romanesque or Norman architecture, familiar to us today in such grand buildings as cathedrals, churches and castles but perhaps slightly surprising to find on a house set within an informal terrace on an urban street.

The house is also remarkable in preserving on its facade a broad pier above the front door that contains a flue and that once terminated in a chimney stack. In the twelfth century it was usual for domestic buildings to have an open hearth placed towards the centre of the room they served. Here, by contrast, in the first-floor chamber that stood above a ground-floor hall or shop there would have been a fireplace set within a wall opening. Those whose houses contained open hearths would have had to endure the smoke that belched forth.

‘The Jew’s House’, numbered 15 The Strait, Steep Hill, Lincoln, built c. 1170 and one of the oldest surviving continuously inhabited buildings in Britain. Note the robust masonry construction, the high-status Romanesque details including remains of semicircular arched windows, and the first-floor chimney breast set above the front door.

Those who lived in the Jew’s House could have enjoyed the comfort of a fire’s heat without the inconvenience of its smoke. The house was not only beautifully designed and crafted but also, in its incorporation of a fireplace and chimney, embraced a technical improvement that was then still a comparative novelty.

We do not know who created this house over 850 years ago, but the popular assumption is that it was originally occupied by a member of Lincoln’s once relatively numerous and wealthy Jewish community. It is generally agreed that a Jewish presence in England was established – or at least greatly enlarged – at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066 by William I, who valued the services of Jewish bankers when it came to securing much-needed loans. If the house on Steep Hill really was built by a well-to-do Jewish citizen of Lincoln (tradition associates it with the town’s leading Jewish banker, Aaron, who died in 1186), that might explain both its authoritative appearance and the fact that it was built in a style closely associated with the newly established Norman state. It could also account for the reason why this small house was so substantially built – why, indeed, it almost resembles a small fortress. Any building associated with the Norman regime could have been a target for those long-established and disgruntled inhabitants of Lincoln whose fortunes and status had decreased in the years after the Conquest (the very fact that William I should have decided to build a castle and a cathedral side by side in the upper city suggests he was aware of the need to exert physical and spiritual control over his potentially troublesome new subjects). Any building associated with a Jewish banker who served the Norman king would have been doubly at risk, as was amply demonstrated by the events of 1190, when simmering resentment sparked by Crusader reversals in the Holy Land (including the loss of Jerusalem in 1187) turned to attacks on Lincoln’s Jewish community.4

The Jew’s House is a remarkable survival. It also neatly embodies several of the themes that this book explores: the technological innovations that have been incorporated into English domestic

architecture; the ways in which houses were used; the – often complex – relationship between the person who commissioned them or who first lived there and those who actually built them; and, finally, the messages and meanings conveyed by the styles or forms that were chosen.

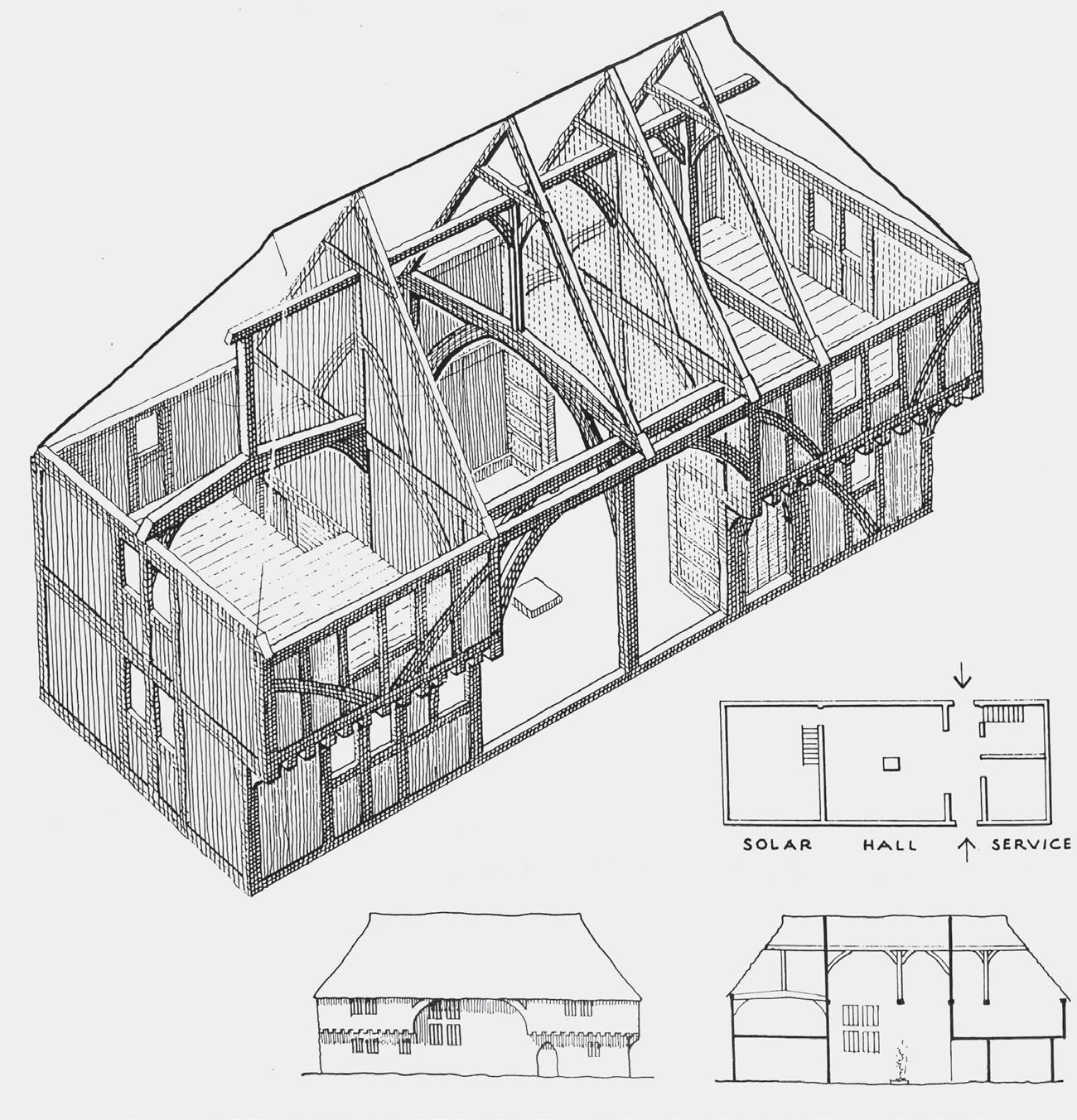

Technological innovations invariably involve introducing greater comfort and convenience into the home, but their progress has often been slow and uncertain. The Jew’s House was, as I have just mentioned, one of the first surviving domestic buildings to feature a mural flue and fireplace. Nearly 180 years later, from 1348, each of the (originally) forty-four houses of the Vicar’s Close in Wells, Somerset – two parallel rows of terrace houses facing each other across a cul- desac – was given a large, centrally placed chimney breast and towering chimney stack.5 Yet even in the fifteenth century, many houses – for example, the oak-framed so-called Wealden hall houses that were once plentiful in the prosperous Weald of Kent (although by no means confined to that region) – were built with a large, doubleheight, centrally placed hall with an open hearth. The roof timbers of the magnificent hall at Bayleaf Farmstead, though probably originally painted, must quickly have become soot- blackened by the smoke rising from the open hearth and making its way out of the building via a louvre or gablet in the roof.6

Gradually, though, fireplaces became both standard features and important focal points. As we will see, at 19 Princelet Street in Spital fields, the first known occupants, the Huguenot Ogier family, made their mark by installing a fine timber-made, Frenchstyle, mid eighteenth-century rococo fire surround (Chapter 2). Just over a century later the fireplace achieved what can be described as its grand apotheosis in the house of the Victorian industrialist William Armstrong at Cragside in Northumberland (Chapter 5). Other innovations – improved cooking facilities, for example, and sanitary arrangements – have similarly followed paths that have not always been strictly linear, not least because their adoption has invariably been bound up with questions of social status and relative affluence. At the time William Armstrong was installing kitchen ranges,

Vicar’s Close, Wells, Somerset, dating from 1348 – the oldest coherently planned and continuously occupied uniform street to survive in Europe. The tall chimney stacks proclaim the pioneering domestic comfort of these small houses.

flushing lavatories and electrical lights in his grand house, many of his poorer countrymen would have been cooking over open fires, using a shared privy and lighting their houses with gas lamps or even still using oil lamps or candles (Chapter 6).

When it comes to the overall arrangement and usage of rooms within houses, the essential forces behind change were a combination of those that drove technological innovation – the desire for greater convenience and comfort – with those that served an increasing desire for privacy and those that expressed wealth, taste and social status. Sometimes, as with the Wealden hall houses, the last consideration might trump the other two. The owners of Bayleaf Farmstead went without the convenience of a fireplace set against a wall and supplied with a flue and stack. On the other hand, their double-height hall proclaimed their elevated position within the local feudal system. The hall was a grand affair, crowned by an impressive roof truss which incorporates a handsome crown post that supports a collar plate and collar-beam and which in turn rises from a stout and lightly ornamented tie-beam, which is itself supported by massive arched braces.

This magnificent room would have been the heart of the home, a place of reception and entertainment, where meals were consumed and perhaps cooked (although there was probably a kitchen in a separate building as well), and where bedsteads for humble members of the household could be arranged at night. With its lofty dimensions and raised dais upon which the family and its honoured guests would, on festive days, dine in some state at the ‘high table’, it proclaimed its owner’s status. And while the house was, in some senses, quite old-fashioned for its time, it’s worth noting that its first-floor ‘solar’, or upper chamber, probably serving as the family’s private bedroom and sitting room, appears to have been supplied with the modern convenience of its own privy, projecting from the side elevation of the main house and emptying into a cesspit below.

Grander medieval houses tended to follow a similar plan. Adjoining the dais end of the hall would be a two-storey wing containing family rooms, including a ground-floor parlour and at first-floor level a solar that on occasion could project into the upper volume of the

hall and hover above the high table, implying a canopy. There might also be a bedchamber for the head of the house. At the opposite end of the hall, beyond a cross-passage connecting front and rear doors that in larger halls might be concealed behind a screen, was typically a corresponding wing of equal size, reached usually via two or three doors from the hall. This was the service wing, with one door leading to a buttery, in which bottles of ale, cider or mead would be stored, and the other door leading to a pantry, used for food preparation and the storage of bread and flour. If there was a third door, it might lead to a separate kitchen (usually an innovation for slightly later hall houses of the larger kind), or to a ladder-like staircase to communal lodgings on the first floor.

By the early sixteenth century, the demand for comfort, convenience and privacy had increased markedly, and houses were being reconfigured accordingly. Typically, operations within the home became more streamlined, more efficient, and also more discrete, with fewer functions taking place in shared spaces such as the great hall and the solar. By the mid sixteenth century the double-height hall of the type to be found at Bayleaf Farmstead had mostly been superseded (often via the insertion of a new first- floor level), by a downstairs hall – reduced in function to serving largely as an arrival and reception area – and a more private and comfortable great chamber above. The new arrangement was made possible by the more general adoption of chimney stacks, which, of course, funnelled smoke away and heated rooms more efficiently and safely. To reach the upper-floor rooms, practical staircases were introduced, replacing the steep ladder-like affairs that had existed before. Often these early domestic staircases were of spiral form (like the larger staircases found in great medieval houses or castles) and placed within staircase towers. These frequently adjoined garderobe towers, which incorporated privies and which, to make life a little easier, were generally located near bedchambers.7 Grander houses of the Tudor period continued to make use of the courtyard arrangement popular in medieval times, but reined it in to achieve greater comfort. The standard pattern was four ranges around a central court entered by a gate of more or less symbolic grandeur.

A typical fifteenth-century Wealden hall house, based on Bayleaf Farmstead. In the centre is the full-height hall, with its crown post roof truss and central open hearth. On the left are the family quarters, including the solar, and on the right the service wing.

Hall and great chamber would typically sit within one range (usually facing the gate), with a service range including kitchen, pantry, buttery and lodgings, and a higher-status range for family and guests, perhaps including a first-floor long gallery for promenading and for the display of art and other treasures. Smaller houses from the 1530s or so until well into the seventeenth century often followed an arrangement now known as the lobby entry, though its precise form differed slightly across regions. Typically, a two- storey house was provided with a massive masonry chimney stack, located towards the centre of its plan, that served the kitchen/hall to one side of it and the parlour on the other. On the other sides of the chimney stack were placed a lobby – entered from the front door and giving entry to the kitchen and to the parlour – and a spiral staircase leading to first-floor bedrooms. The staircase could be entered from the kitchen or the parlour or indeed, with some ingenuity of planning, from both. This plan form, radical in its break with the cross-passage tradition of the hall house, not only made efficient use of space, with little required solely for movement around the house, but also offered increased convenience and privacy, primarily because the service functions of the house, and the servants, were separated from the family area of the parlour. Often a third room was added, adjoining the parlour or the kitchen. The brick-andterracotta-built Old Hall Farm at Kneesall, Nottinghamshire, probably created in the mid 1530s as a hunting lodge for Sir John Hussey, who became lord of the local manor in 1522 and served as the Chief Butler of England, offers a good early example.8

Houses of this period built in England’s ever- growing towns tended to adopt a different pattern, for the simple reason that because urban land was expensive and urban sites invariably constrained, more accommodation needed to be squeezed on to any given site. Some, it is true, continued to ape the approach of earlier houses: the ornately carved timber-framed Paycocke’s House in Coggeshall, Essex, for example, which was built in about 1500 by a wool merchant named John Paycocke and extended in about 1510 by his son Thomas, incorporates the remains of an early fifteenth-century open hall house and cross-passage form of entry.9 But the builders of other urban houses

Paycocke’s House, Coggeshall, Essex, built at the very beginning of the sixteenth century for a wealthy cloth merchant, probably incorporating part of an earlier structure, and thoroughly but sensitively repaired and restored in the early twentieth century.

resorted to adding storeys or building more rear rooms or ranges to squeeze in as much as they could. Town houses built on so-called urban ‘burgage’ plots tended to be relatively narrow but deep, with rows of accommodation – tenements, workshops or warehouses but also some serving domestic functions – strung out behind the main house on the street and typically reached via narrow alleys. In ancient towns that had strong trade, manufacturing or port traditions, the pattern might be reversed, so that the street front contained a shop, and the rear range the house’s ‘hall’ accessed by a narrow passageway. King’s Lynn, on the wide River Ouse and once a major trading port, boasts a number of houses, set parallel to the town’s river front, of roughly L-shaped plan where this disposition of uses applies.10 Generally, the first floor of the street range would contain a private chamber, placed above the shop. Access to the rear was through a passage opening from the centre of the facade.11 The combination of home with work or trading space remained a constant feature of urban houses. The owner of the magnificent Maister House in Hull (Chapter 3) would doubtless have met business clients there. At Heywood’s in Liverpool (Chapter 5), we see a wealthy eighteenth-century dynasty of traders and financers creating a building that was both house and bank.

As for the materials from which such houses would have been constructed, this depended largely on what was most readily to hand and, in the case of humbler dwellings, what was cheapest.12 Local stone was much used in the central portion of England, from south to north, in the West Country and in the south-east. The precise type of stone varied, of course, from area to area: Dorset offered Portland stone; oolitic limestone was to be found around Bath; Doulting limestone in the Mendip Hills; Barnack stone in Cambridgeshire and into Lincolnshire; sedimentary ironstone in Northampton; and around Derbyshire, Ashford ‘Black Marble’ (in fact a limestone). In Kent and along the south coast, the sedimentary Kentish ragstone, flint and chalk were all easily available and favoured. Flint – used as pebbles, or ‘knapped’ to present a sparking face – was common in East Anglia. To the north and north-east lay numerous types of sandstone

as well as slate; to the west, igneous rock, notably granite. In areas where materials and money were scarce, there was always cob, which is essentially blocks of mud, bound with straw (and sometimes with a little lime added as a hardener), which could be used to build thick walls protected from the elements by regular coats of limewash. Clay was increasingly employed in south, east and central England from the thirteenth century to revive a brick-making industry dormant since Roman times. And over much of England there were forests of oak and elm that provided excellent and durable timber, mostly used to form frames, infilled with wattle and daub (woven twigs and mud mixed with straw) or later with laths and lime plaster or with brick.

Between the late twelfth and sixteenth centuries, such materials were employed to create traditional and native Gothic forms and details; thereafter foreign Renaissance influence became increasingly paramount. As the following chapters show, architectural style was often a matter for heated debate, notably in the nineteenth century when battle was joined between those who favoured Renaissance buildings and those who championed a return to the Gothic (Chapter 5). The use of local building materials, once a matter of convenience, similarly became a bone of contention, champions of the late nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts Movement arguing, for example, that domestic design and construction should be rooted in regional vernacular building traditions and utilise local materials. In the twentieth century, Continental influences once again came to the fore in the house that Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke had built for himself in Northampton and that he named New Ways (Chapter 8).

Until the mid seventeenth century, English houses were, for the most part, one room deep – or ‘single pile’. This offered the advantage of making it easy to clear houses of smoke and allowing plenty of light to enter (particularly if the orientation of the house offered both morning and evening light). But because rooms were arranged in a linear fashion, like coaches on a train, it was often necessary to pass through one or several rooms to reach the one you wanted

to be in. Various forms of lobbies were experimented with, but the lack of privacy remained an irritation and an inherent problem. The invention of the two-room-deep ‘double-pile’ house, served by a staircase, landings and passages, however, solved the conundrum. Early examples tend to be urban ones, like the square-plan Whitehall, in Monkmoor Road, Shrewsbury, which dates from 1578 to 1582.13 Ultimately, architecturally conceived corridors (the word is first recorded in England in around 1600),14 as opposed to humble passages, would become a standard feature of house design. 15 In his additions for Hampton Court Palace in the 1690s, for example, Sir Christopher Wren designed a sequence of eight connecting rooms for the King’s Apartment (what is known as an enfilade plan), with doors aligned to offer a vista and a promenade of state from the guard room via presence chambers, dining room, throne room and state bedchamber to a small room where informal meetings could take place, termed ‘a closet’ or ‘cabinet’. But he also created, running parallel to part of this route, a gallery that also functions as a corridor offering a route of service, via anterooms, to the state dining room and bedchamber.16 One of the most stunning early double-pile houses is Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, built for the Countess of Shrewsbury from 1590. Representing a possible evolution of the traditional H-shaped plan for such grand edifices, it uses passages to ease connections between its various rooms and to ensure convenience. The house is remarkable in other ways, too. In style it is a heady mix of Gothic tradition and boisterous Renaissance novelty. It contains the double- height hall that would have been familiar to the countess’s ancestors, but this hall is set on an axis (i.e. on the main centre line through the building, not at right angles to the entrance), so creating the sense that it’s a grand point of arrival through which one passes rather than a destination in which to linger; in a way it’s more like a modern entrance hall than a medieval great hall. The best chambers are distinguished by their floor-to-ceiling heights and arranged in hierarchical manner, with the best (and tallest) ones at the top of the house, where the prospects of the surrounding estate are particularly enticing. This suggest a sense of functionalism that is, again, almost modern. One other unusual

feature is that the wide and stately staircase is set to one side of the plan. It provides a grand route through the interiors – indeed something of an architectural promenade – its elemental scale and stone construction making it seem almost like a street, and its asymmetrical design offering a strong contrast with the dedication to the newfangled Renaissance obsession for symmetry apparent in the rest of the house. And there is technological innovation, expressed best by the huge windows, demanding large amounts of glass that was an expensive luxury at the time, that allow daylight to flood into the best rooms. Perhaps most memorable is the house’s sensational and romantic silhouette, with its tall cubic prospect towers that give it a fairy-tale quality – like an Elizabethan evocation of Camelot.

The outline plan of the Hall is also intriguing. It is formed by two squares of equal area separated by a pair of squares (each half the area of each of the large squares) that define the plan of the central great hall. Smaller squares, representing the Hall’s six towers, are placed on or near the centres of the three outer faces of the large squares. Such use of squares and cubes suggests a familiarity with the Renaissance planning theories of Sebastiano Serlio and Andrea Palladio, for whom such forms were all- important.17 But compositions incorporating ten squares, as is the case here, and implying ‘ten squared’, might also have been seen as a means of achieving mathematical and geometrical perfection, with square numbers – in this case 100, or 10 x 10 – representing harmony. If this ten-squared plan was a device, then it was fully in keeping with late Elizabethan thinking. This was an age fascinated by the witty or symbolic use of conceits, devices and emblems, of which the play of squares in the plan of Hardwick could be an expression.18

And this raises other – interrelated – themes that are pursued in the chapters that follow: the creative relationships that the patrons who commissioned houses had with their master masons, surveyors or architects, and with the building tradesmen they employed; the messages – touching on their status, beliefs, ambitions, loyalties and tastes – that patrons wished to convey through the architecture they commissioned; and the conundrum of establishing when the prime

Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, built from 1590 for the Countess of Shrewsbury, probably in part, at least, to her design and to the design of the masonarchitect she employed, Robert Smythson.

responsibility for the creation of a house passed from the client or occupant to the building professional responsible for its design and execution.19

To create Hardwick Hall, the Countess of Shrewsbury called on the services of Robert Smythson, a master mason and architect of prodigious talent, who had worked from 1568 at Longleat in Wiltshire and from 1580 at Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire. 20 His contribution at Hardwick Hall must have been of the greatest importance, although since no detailed plans of the Hall or correspondence between client and architect survive, it is hard to state this categorically. Such a gap in the historical record is as typical as it is perhaps extraordinary. Building a home is a personal and emotional affair that is well worth recording and discussing, yet relatively few contemporary or intimate documents – such as letters or diary entries – survive in significant number that chronicle the creation of historic houses, or at least those that are much more than a century old. What does survive, in large quantity, are building accounts that list names of tradesman, sums charged and dates on which bills were paid – the essential if somewhat arid evidence of once-tumultuous building projects. As it happens, these survive for Hardwick Hall and, if lacking in opinion or emotion, they do at least impart valuable if cryptic information about the creative process and the relationships between those involved. For example, they tell us that in March 1597, as the Hall was being completed, twenty shillings was paid to Smythson and ten shillings to his son, perhaps by way of token gifts from the countess, at the time of her house- warming, for services rendered.21 That patron and designer worked well together seems to be confirmed by the fact that, even before Hardwick Hall was completed in 1597, the countess commissioned Smythson to design and build yet another new house – Oldcotes – nearby and for the use of her son William Cavendish.22

Whatever design and practical skills Smythson may have brought to bear at Hardwick, it’s hard to believe that the countess was not herself closely involved. She was, after all, both a remarkable woman and an avid builder, whose several marriages generally had

architectural consequences. In 1547 she married Sir William Cavendish, her second husband, who in 1549 she persuaded to buy the Chatsworth estate in Derbyshire. This presented her with the first great architectural opportunity: the building of a new house at Chatsworth, on an idyllic site near a river. Cavendish died in 1557, so she married again but death once again intervened, which led in 1568 to her fourth marriage – to the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, one of the richest and most powerful men in England. This marriage proved deeply unhappy, and in 1584 the countess fled from Chatsworth – on which she had spent much of the earl’s money – to her modest family manor house at Hardwick, which she had purchased from her impoverished brother the previous year. Here she put her heart and soul into the realisation of an architectural vision: to make the family home and estate at Hardwick an acceptable alternative to the renounced Chatsworth. First she built an almost entirely new house on the site of the manor, now known as Hardwick Old Hall, making it more convenient and fashionable. And then, thanks to the death in November 1590 of her estranged husband and the wealth that now came to her, Hardwick Hall itself. Begun within a month of the Earl of Shrewsbury’s death, it constitutes a declaration of independence, of wealth, of advanced taste and of a determination, as the architectural historian Mark Girouard puts it, to create ‘the perfect house’.23

Over the next centuries, as the following chapters show, the role of the designer of houses for more prosperous members of society would evolve and change. Number 19 Princelet Street in Spitalfields was planned and constructed in 1718 by a local carpenter and speculating builder named Samuel Worrall. Maister House in Hull, by contrast, while calling on the skills of the town’s craftsmen, was in part overseen by one of the foremost arbiters of taste of the period, the 3rd Earl of Burlington, while in the following centuries Cragside in Northumberland and New Ways in Northampton were conceived by professional and widely acclaimed architects of national, indeed international, repute: Richard Norman Shaw at Cragside and Peter Behrens at New Ways.

As for the role of the patron, this varied enormously from project

to project. At Pallant House, Elizabeth Peckham demonstrated that the Countess of Shrewsbury was not a lone female voice in English architectural history, even if she sadly lacked the power and authority the countess possessed to ensure that she was able to enjoy the house on which she lavished so much attention. The wealthy male patrons of Cragside and New Ways, on the other hand, were able not only to shape the projects they funded, but to depart from the architect’s masterplan as and when they wanted. At Cragside, what had been a fruitful collaboration between patron and architect was ultimately damaged, at the very end of the project, by a niggling dispute over the detailed design of the ‘Gilnockie’ tower.

The messages such collaborations physically embody are fascinating to decode. The houses may simply reflect what was fashionable at the time, but they may also seek to present their creators as knowledgeable arbiters of what will come next. New Ways, for instance, was the brainchild of a wealthy businessman who proudly proclaimed it to be a ‘Super-Modern Home’ and ‘a fore-runner of the house of the future’. The architectural styles these houses adopt may reflect a desire on the part of their creators to be regarded as people of considered taste and refinement, as the Palladian Maister House does. They may also reflect more general contemporary preoccupations and issues of the period. The Gothic elements of Cragside form part of a wider Victorian debate about appropriate national styles for architecture in an age of empire, industrialisation and radical change and about the ethical and moral symbolism of those styles.

The less well- off in society, of course, were never in a position to discuss the nature of the house they lived in with the person who designed it. They effectively had to accept what was on offer. But, as the chapters on ‘two-up two-down’ houses in Toxteth, built according to the standards imposed by local and national government byelaws, and the council flats of the Boundary Estate in Shoreditch, east London, show (Chapters 6 and 7), design principles were nevertheless on display in even the humblest of homes. The simplest, least ambitious of the houses in Toxteth display in the details of their brickwork the aspirations that those who created them entertained for those

who lived in them. For its part, the Boundary Estate is the work of a highly talented and highly committed team of architects who were determined to create a paradise of ‘sweetness and light’ in an area that had until very recently been one of London’s worst slum areas. Each of the eight chapters that follows seeks to tell the story of the creation of a particular house or kind of house, from a grand Georgian town house to a Victorian country retreat, to a councilfunded flat intended for the working poor. Each of these dwellings is also representative of an important moment or development in the history of the English house, while simultaneously offering a lens through which the wider history of the nation can be viewed and understood. Each, in other words, is individual but stands for something more than itself. Number 19 Princelet Street in Spitalfields is both an elegant early eighteenth-century terrace house and a physical record of successive waves of immigration, most dramatically so when it became a synagogue in 1870 for Jewish families escaping persecution in central and eastern Europe. Heywood’s house and bank in Liverpool is a fascinating blend of home and institutional building and a window into the trading past of one of England’s premier ports. The chapters covering the bye-law housing in Toxteth and the Boundary Estate in Shoreditch show how efforts were made in the late nineteenth century to replace desperate slums with decent homes for working people – in Toxteth through private and profit-orientated enterprise and in Shoreditch through a pioneering programme of public housing – where the ambition to provide hygienic accommodation was combined with a desire to achieve a certain beauty that would dignify and inspire those who would occupy these new homes. Each tale is individually remarkable. Each is also emblematic.

The entrance front of Pallant House, facing west onto North Pallant. Built by Henry and Elizabeth Peckham in the early eighteenth century in Chichester.

—

Architects and Patrons

Pallant House, Chichester (1712)

Many older houses are, in historical terms, fairly anonymous affairs. We may be fortunate enough to have a record of who commissioned them or had overall responsibility for their construction, or building accounts, tax or insurance documents may still survive. But beyond such information as these fragments might offer, we generally know little; and since so many of these houses were radically transformed by subsequent generations, even the surviving physical evidence they have to offer can be patchy and difficult to interpret. In the case of Pallant House in Chichester, West Sussex, however, not only does enough of the fabric of the original house remain to allow us to build up a good picture of how it was built, but thanks to a financial dispute between the husband and wife who commissioned it, we also know a lot about those involved in its genesis and about its first inhabitants.

The story of the house can be said to start in May 1711, when Henry Peckham married Elizabeth Albery (née Cutter) at the church of St Martin Outwich in the City of London. He was twenty-seven years of age, came from a well-established Chichester family with something of a turbulent financial history and appears to have been a merchant in the wine trade. She was a forty-year-old widow, the daughter of a clergyman and the sister of a Royal Navy officer. Her brother Vincent Cutter had died unmarried and childless in April 1710, and by the time of her marriage in 1711 Elizabeth was in

possession of an inherited fortune of £10,000 and the lease of his sixwindow-wide house in London’s Soho Square.1

Even before the marriage took place there were signs that all was not well. Elizabeth and her father had insisted that she should retain control over at least part of the £10,000 she would otherwise surrender to Henry on marriage, which Henry had resisted. So acrimonious did things become that at one point he ‘did actually discontinue his address’ – in other words, he stopped wooing Elizabeth.2 Eventually a compromise was reached whereby he agreed to allow his future wife £50-a-year pin money to spend how she would, and the wedding went ahead.

The building project in Henry’s home town seems to have been embarked upon soon after the marriage,3 and, if the sworn evidence in the Court of Chancery case is to be believed, appears to have been Elizabeth’s idea. A prominent site was selected,4 before which lay a crossroads then dominated by the town’s leather trade and marked by a timber- made market cross. The City Minute Books for the period record that Henry Peckham arranged for the ‘Pallant’, or space around the cross, to be ‘altered to make the new building’ – with his proposed house rising on a ‘new foundation . . . square towards the South’.5 Subsequently, in March 1714, Chichester Corporation agreed to Henry’s request to demolish the cross itself, on the condition that he set up ‘a convenient shed’ elsewhere in St Martin’s Lane to serve as a replacement market site.

Three years later, husband and wife were at legal loggerheads. According to the Court of Chancery Records of 1717, Elizabeth – the ‘complainant’ – argued that Henry – the ‘Defendant’ – had abused her financially and squandered much of her fortune on the new building project, and that he had sometimes operated in an underhand or fraudulent manner. Henry’s defence was that his wife had known what was going on, and had been fully aware of the costs that had been incurred. Indeed, he claimed that she had run the operation, supervising and instructing the tradesmen and, through some of her actions, actually increasing the cost of the building project.6

That Elizabeth was very closely involved in the planning of the

house seems unquestionable – and, for the time, perhaps unusual. Until the early twentieth century, there were (officially, at least) no female architects, and although women do appear to have been occasionally involved in the design of buildings – for example, Elizabeth, Lady Wilbraham, in the late seventeenth century – it’s difficult to know what precise role they fulfilled. Even in the more refined areas of the arts, such as painting, famed female artists or decorators remained few and far between until well into the nineteenth century. The seventeenth century boasted the Rome-born Artemisia Gentileschi, the London-born Joan Carlile and Mary Beale, and Angelica Kauffman was active in the eighteenth century, but there was a minuscule number overall.7

When it came to the building trade, a few wives and widows did run tradesmen’s offices (accounts for the construction from 1729 of the James Gibbs-designed ranges at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Smithfield, London, for example, record numerous payments to female members of the building trades.8 But in general, just as women were denied the most basic civic rights (as the transfer of Elizabeth’s fortune to her husband on marriage demonstrates), so any aspirations they might have nurtured for professional status or engagement were largely snuffed out. It’s possible to identify only a small group of generally aristocratic female patrons of architecture and the arts: the Countess of Shrewsbury – ‘Bess of Hardwick’ – in the late sixteenth century (see p. xxi), Queen Mary II in the late seventeenth century and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, in the early eighteenth century. Thanks to the survival of the records of Elizabeth Peckham’s legal dispute with her husband, we can add her name to that very short list.

The surviving court documents testify to Elizabeth’s close involvement in the building of Pallant House. They also demonstrate that the term ‘architect’ – denoting someone with a professional ability and interest in building – lacked at that time a precise meaning that would have been universally agreed. Essentially, there were two types of building practitioners who fulfilled the role of architect, or, rather,

the role of designer of buildings and overseer of their execution. One comprised educated gentlemen, like Sir Christopher Wren, for whom architecture was a civilised accomplishment, much like music, the classics, geometry, mathematics or natural philosophy. Such men were gifted dilettantes – in Wren’s case, of course, exceptionally so. In early eighteenth-century England, talented gentlemen who did not gain high or public office but displayed architectural ability appear to have been called ‘contrivers’ of buildings – now a verb with a rather unflattering sound.9 When Wren ultimately gained public architectural office, he was known by the rather grander title of ‘surveyor’.10

Aspirant ‘contrivers’ at this time started out by serving as articled pupils, essentially as apprentices. They learned their craft within an established architectural office working under the auspices of a ‘master’. A novice architect would be supervised closely, at least initially, to ensure they mastered the practical aspects of their profession: learning to draw and to set up perspective renderings of buildings, for example, and imbibing the language of architecture (notably the classical orders such as Doric, Ionic and Corinthian), structural theory and at least a little history. Increasingly, many would undertake grand tours, mostly to Italy, to acquire first-hand experience of antique exemplars of prime importance. James Gibbs, the Aberdeenborn designer of St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square, spent time in Rome in the very early eighteenth century, studying with the well-established baroque architect Carlo Fontana. Robert Adam, the son of a Scottish builder/architect, undertook a grand tour in the 1750s. John Soane, also the son of a bricklayer, followed suit in the late 1770s. In the usual course of events the young architect would become a principal assistant, a role many might retain for much of their career if their master was accommodating. The more ambitious would seek professional independence, and hope to gain the necessary distinction and expertise that would attract and please clients.

The other type of building practitioner – the one involved in designing and constructing the lion’s share of England’s buildings from the medieval age well into the eighteenth century – was populated by masters of the building profession itself. These were not

‘gentlemen’, nor were they necessarily highly educated in the classics or history. They were tradesmen, often members of dynasties of builders or quarry owners with strong regional connections. Typically, they had developed a strong empirical understanding of the structural and engineering aspects of architecture and had acquired knowledge about the qualities of building materials. When it came to planning buildings, however, they generally produced designs of a distinctly vernacular, traditional or regional character. For them, soundness of construction and functional requirements tended to be more important than style or the pursuit of current architectural fashions.

The princes of these tradesmen – often highly skilled and experienced – were masons.

From the early seventeenth century, masons might not have necessarily been commissioned to act as lead designer for high-profile, aristocratic or Royal Court projects (there are, of course, numerous notable exceptions), but they were the favoured choice as ‘architect’ for merchants, City of London institutions and the universities. Increasingly from the late seventeenth century, particular masons tended to develop close relationships with individual gentlemen surveyors. The latter did much to win commissions and supply designs with stylish erudition and a dash of beguiling fashion, while the mason, with access to a trusted body of tradesmen, was in a position to guarantee sound construction and detailing, and to provide knowledge about the acquisition of good building materials at competitive costs. The reconstruction of St Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London in 1666 displays how fruitful and symbiotic this relationship could prove. In the course of its thirty-five-year gestation and construction the cathedral became almost a college for craftsmen and designers, including Nicholas Hawksmoor and Christopher Kempster. Such men, having drunk deep at the well of Wren’s architectural knowledge, and having imbibed his design ethos, disseminated his inspired version of English baroque around the nation.

A number of the craftsmen involved in the building of Pallant House were called on by Henry to give sworn depositions in his defence, and so we know their names and the contribution they

made.11 Henry Smart, ‘of the City of Chichester’, who was by trade a mason, ‘aged fforty years or thereabouts’, was evidently the man Henry and Elizabeth Peckham had approached first to design and presumably to supervise the construction of their new house. Alongside him was Richard Clayton, ‘of the City of Chichester . . . Carpenter . . aged about Two and Thirty’, together with 53-yearold John Page and 36-year-old John Chanell – also carpenters – and John Pryor, a local 30-year-old ‘joyner’.

It is typical of a provincial town in the early eighteenth century that the Peckhams should have chosen a mason as their architect rather than an informed local gentleman, and Henry Smart appears to have been a mason who was capable of designing a sound building and who, through his trade connections, could supply contacts to the other tradesmen and craftsmen required, who would be employed independently. In 1712 this is how things were done in the building world: construction organised by a ‘general contractor’ – where one eminent tradesman took responsibility for all aspects of the building project – was still several decades in the future. It would only become a practical proposition from the 1770s under the inspired leadership of architect/speculators like the Adam brothers and from 1800 by builder/architects such as James Burton and the London-based builder Thomas Cubitt, who undertook the construction of entire urban quarters.

Certainly, from what we know of Smart, he appears to have been the epitome of a skilful, traditional master mason. In the course of his career he worked for the 2nd Duke of Richmond at Goodwood Park, near Chichester, and in about 1730 forged a relationship with the well-connected pioneering Palladian architect Roger Morris, who had been hired to redesign Goodwood’s great hall. In around 1731 Morris won the commission to design the new Council House in Chichester – a remarkable Palladian project supported by the Duke of Richmond – and it seems likely that Smart was closely involved in the building that emerged. Ultimately, in 1751, at the age of about seventy-five, Henry Smart would become Mayor of Chichester, presumably as a reward for long and loyal service, and following in the

steps of two of his patrons: the 2nd Duke of Richmond, who served in 1735, and Henry Peckham. Peckham was a committed Tory who served three terms, in 1722, in 1728 and in 1732, and so was presumably the first mayor to preside in glory at the new and very fashionable Council House.

From Smart’s 1717 deposition it is clear that he had known both husband and wife ‘many years’ (Elizabeth was also originally from West Sussex) and that ‘before the building of the House’ he had been asked to ‘make a fframe or modell thereof’ that he then presented ‘to the Complainant & Defendant Peckham’. As an experienced mason he was well able to do so, but it would appear that the design was not all the Peckhams had hoped for. Perhaps Smart’s no doubt somewhat vernacular or provincial design wasn’t ambitious enough for them, or perhaps their architectural aspirations evolved as construction drew near. Whatever the reason, it would appear they wanted something more dashingly up to the minute and metropolitan than the ‘modell’ offered.

Henry and Elizabeth Peckham now departed for London, and when they returned – Smart does not say how long they were away – Henry showed the mason ‘a new Modell which was drawne at London’ which Henry asked him to ‘explain’. It seems a strange request, suggesting that Mr and Mrs Peckham were woefully ignorant and inexperienced when it came to reading architectural diagrams and anticipating the problems or costs realisation might involve. Of course, it’s also possible that the design was very sketchy, and that it required interpretation or explanation by an experienced builder such as Smart. There is, sadly, no hint about the author of the ‘Modell’ or whether it was a sketch of an exemplary London house – or even a bespoke design drawn in London by an architect who was unnamed at the time, and who remains anonymous.

Smart’s use of the word ‘Modell’ here is interesting. His deposition states that it was ‘drawne’, so it was not a three-dimensional model of a house in the modern sense. It can also be argued that the term ‘Modell’ confirms that the drawn design was modelled on a specific and exemplary London prototype that the Peckhams had seen and

admired, and, given that Smart had to ‘explain the same modell to them’, that the ‘drawne’ design was no more than an amateur sketch of an admired building that the husband and wife required Smart to flesh out and to explain how it might be best built and detailed.12 It could also be that the Peckhams had in mind a design modelled on the capital’s way of doing things. Since 1667, domestic architecture in central London had been governed by Building Acts that were framed to help ensure sound- and fireproof construction. These also looked to relate the scale of a building to the site it occupied and, in general terms, promoted brick or stone construction along with simplicity of design and uniformity, and limited the external use of timber and ornament. The use of potentially combustible external timber details had become a particular issue, as revealed by the Buildings Acts of 1707 and 1709, which aimed to replace the use of timber eaves cornices with brick or stone parapets and ordered that exposed timber sash-window boxes be set back four inches – or the depth of one brick – from the face of a building. At Pallant the boxes are not recessed the London regulation four inches, though it’s worth noting that even in the Cities of London and Westminster, where the legal rule of the Acts did apply, builders regularly set the boxes flush with the facade well into the 1730s. There is, however, a brick parapet.

Whatever the precise details of the design that Smart explained to his clients, he made it clear that in his opinion, ‘the Modell brought from London would be more expensive’ than ‘his Modell’ and suggested that it would cost ‘at least sixteen hundred pounds to build’. This, he said, did not daunt Mrs Peckham. She ‘liked best the London Modell and upon her liking it’ Mr Peckham ‘proceeded and built the said house according to the London Modell’.

If there’s a single feature of the house that helps to explain why ‘the London Modell’ should have been so much more expensive than the one initially proposed by Smart, it’s the extraordinarily accomplished main staircase. Made of oak,13 with bands of inlay, presumably in walnut, it was conceived and designed as if it were wrought from stone, each of its treads shaped like a stone slab, one resting, as it were, upon the slab below and supporting a slab above. The

Queen’s House, Greenwich, designed in 1616 by Inigo Jones with construction continued to 1635. This could be one of the ‘London Modells’ admired and emulated by Mr and Mrs Peckham when commissioning Pallant House.

end of each slab-like tread presents a rectangular face carved with varied emblems and is combined with a delicately carved serpentine bracket that appears to help support the tread above. Seen from below, the treads have a strikingly sinuous form, echoing the profile of the carved brackets. Light, elegant, structurally daring and forwardlooking in terms of style and construction, the staircase’s two flights are linked by a half-landing and finish at a wide first-floor landing with a balustrade sitting on an architrave and carved frieze, and with a centrally placed arched window to light it – a standard design of the time.14

Not only does the staircase exhibit wonderful flair and a skilfully baroque concealment of its true construction, it also embraces a wealth of exquisite detail. The balusters, three to a tread, are thin and elegant, all composed of an urn sitting on a plain plinth and supporting a tablet upon which sits a Doric column rising to a block that helps to support the handrail. The columns are of barley-twist form (a popular late seventeenth-century detail): versions of the mythic columns that were thought to have graced Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. The newels take the form of fluted Corinthian columns.

The emblems carved on the rectangular panels are impressively varied. One shows a pair of dragons emerging out of plant tendrils, which may possibly be a merely ornamental touch – chinoiserie was fashionable in the early eighteenth century – but could also relate specifically to Henry Peckham’s role as a merchant (silk and porcelain had long been imported from China). There is a pair of what appear to be palm leaves, a familiar Christian symbol related to Easter and Palm Sunday; then a cornucopia, with flowers emerging out of a pair of shells seemingly implying the bounty and beauty of nature; a pair of crossed clay pipes from which issues smoke in the form of plant tendrils – presumably an emblem of the joy of tobacco and perhaps the profit of its trade; a scallop shell, which had long been a token of Roman Catholic pilgrimage to the shrine of St James of Compostela and to the Holy Land; and sprigs of oak leaves with acorns emerging out of what appears to be the stump of a tree. These could be a Stuart emblem inspired by Charles II’s refuge in 1651 in an oak

The majestically formed and beautifully detailed staircase in Pallant House.

tree after the Battle of Worcester, or they could be connected with Freemasonry, which at that time had an interest in Druids and their associated oak-tree and acorn imagery. If so, then it’s more than a matter of coincidence that acorn imagery should also appear among the little emblems that are carved or moulded on the bricks forming the centre of each lintel of the front house’s facade. If Henry Peckham was indeed a Freemason, he was in good company. According to the seventeenth-century antiquarian John Aubrey, ‘a great convention at St Paul’s church of the Fraternity of the Adopted masons’ was once held when Sir Christopher Wren was to be ‘adopted a brother’.15 And just a few decades later, in early 1750s Bath, John Wood the Elder, a very active Mason, or his son, would top the parapet of the Royal Circus not with familiar images of pineapples but with huge stone images of acorns, inspired by the Masonic embrace of Druids as ‘men of oak’.

There is one other detail, physically related to the staircase but actually part of the panelling scheme of the hall, that appears to have something to say. The half-landing of the staircase sits on a shallow arch that leads to the house’s back door, and in this arch is a keystone that is ornamented, in conventional manner, with a winged cherub’s head. This was an immensely popular motif at the time, derived from Renaissance prototypes. Usually cherubs look happy, even ecstatic, or wear blank expressions implying contemplation of their divine duties – either as guardians of sacred places or as emblems of resurrection. But this one looks positively miserable, or at least very troubled. It’s tempting to believe that it is a craftsmen’s comment on the unhappy circumstances of the house’s creation and of the acrimony and disputes that accompanied it.

Smart had explained to his clients at the outset that their ‘London Modell’ would prove expensive. As building work progressed, even his £1,600 budget first came under stress and was then rapidly exceeded. By the time the Peckhams’ dispute had reached the courts, costs had multiplied almost twofold. For this, if the builders and craftsmen

The cherub keystone within the arch below the staircase half landing between ground and first floor. Cherubs usually look playful, ecstatic or contemplative but this one appears oddly peevish – even miserable and decidedly unhappy with its lot.

involved are to be believed, Elizabeth Peckham was very much responsible. Quite simply, according to them, she kept changing her mind, and her husband allowed her to do so.

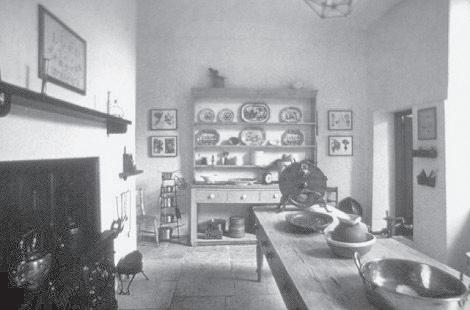

Among the most expensive of Elizabeth’s second thoughts was her decision to change the location of the kitchen. At the time that Pallant House was built, it was common practice in towns and cities – where land was expensive and generally in limited supply – to locate kitchens, along with pantries, sculleries, larders and washrooms, in the basement. But according to the carpenter John Page, Mr Peckham, having originally gone along with this standard approach, ‘had altered his mind on account of his wife’, who had objected that a basement kitchen would be ‘too cold & damp for herself & servants’. Page’s fellow carpenter, Richard Clayton, described the atmosphere in which this decision was made. Henry Peckham, he said, having given him orders ‘to take down the kitchen and offices belonging to their dwelling house’, had declared ‘in the presence of the said Elizabeth that he had built the same to please her and it should be pulled down and rebuilt to please her’. He had then stated bluntly that ‘he was going to London’ and that he ‘would not medle [sic ] with it having had trouble enough about it already’.

It was a costly decision. Visitors to the house today might be tempted to assume that the large and substantial brick-vaulted cellars beneath the house were always intended to house Mr Peckham’s stock of imported wines. In fact, the expensive brick vaulting was erected to make the basement largely fireproof and secure in the event of a cooking accident. It is not structurally necessary except, perhaps, beneath the stone-paved entrance hall. That the decision was made late on in proceedings is evident not only from the brick barrel vaults but from the large chimney breast with a deep fireplace opening necessary for cooking that is still in evidence.16

Clayton offered the court his opinion ‘that the taking down and rebuilding such kitchen and Backhouses cost Threescore pounds or thereabouts’ and that he ‘verily believeth . . . the whole Buildings of the House and Outhouses . . . did cost the sum of three thousand pounds’.17 In 1712 this was a large amount to pay for the construction

The ground-floor kitchen in Pallant House as reconstructed and presented after the house opened to the public in 1982. As a consequence of the construction of the gallery in 2006, this kitchen has been transformed into an anteroom, with a door cut into the wall (to the right of the dresser) linking the new building to Pallant House.

of a two-storey urban house, even one seven windows wide and two rooms deep. Just over forty years later Isaac Ware, in his A Complete Body to Architecture, asserted that the construction of a ‘Common’ London house – three storeys high above a basement, with a habitable garret and two rooms deep – was ‘six or seven hundred pounds’.18

Smart concurred with Richard Clayton’s assessment, asserting that ‘the Backbuildings of the said house were taken down & rebuilt by the Complainant’s order’ and that he took up ‘the pavement in the . . . Backbuildings’, acting on Mrs Peckham’s orders because Mr Peckham was ‘then at London’. He also said that Mrs Peckham ‘did consent to & approve the Building of the steps at the fforefront of the house’, which Mr Peckham ‘would not doe until she had ffirst given her Approbacon [sic ] thereof’ and that he followed Mrs Peckham’s instruction ‘to make and sett up two marble Chimneypieces out of two marble tables which were formerly Captaine Cutter’s’. Finally, Smart, supporting evidence submitted by his fellow tradesmen, said that he had heard that Mr Peckham’s later order to Smart to pave ‘the passage from the house to the Washhouse’ had been overruled by an order from Mrs Peckham, ‘being also present’, to ‘pave the Washhouse first’. So far as the final cost of the works was concerned, Smart stated that ‘he verily believeth that the Building of the said House & Outhouses cost Three Thousand Pounds’ and he told the court that, as far as he was aware, Mrs Peckham ‘did mightily approve of the Work’.19

Ultimately, Mrs Peckham changed her mind about the kitchen not once but twice. According to the deposition of the carpenter John Chanell, having ordered that it should be moved from the basement to a position against the ‘Backside’ of the house, she declared that she ‘disliked’ her new kitchen wing and issued instructions to have it ‘pulled down & rebuilt’. Her husband, Chanell said, apparently merely ordered the ‘workemen to doe’ what his wife ‘would have them do’. Today, the final kitchen that was built – largely within a rear ground- floor room of the main house with a scullery and storage in the adjoining wing – is devoid of interest beyond a few pieces of joinery (including the house’s only original set of sashes). Originally, though, it would have housed a cooking range and spits within a large

fireplace opening; a dresser for the storage and display of plates, and copper and pewter cooking and serving utensils; and food preparation surfaces, including a large, centrally placed kitchen table with a scrubbed timber top. There might also have been a stone sink and a water pump and lead cistern, although these were probably located in the scullery.20

Mrs Peckham’s other significant intervention involved the ‘private’ chambers on the first floor. The joiner John Pryor described in his deposition that one day while he was ‘wainscoting a Chamber in the dwelling house’, Mrs Peckham came into the room where he was ‘at worke and ordered a partition to be made & a door to be made in the Midle [sic ] of the partition to make the Chamber more private’. The work was, stated Pryor, ‘done accordingly’.

It is now generally agreed that the partition ordered by Mrs Peckham is the partition located on the first-floor staircase landing. This makes what was presumably originally intended to be a large lobby, at the centre of the first floor and open to the staircase landing, into an enclosed and private chamber. The partition does indeed have a central door and is a highly ornamental affair, framed by robustly detailed, fluted Corinthian pilasters and an elaborate cornice, even if, in its somewhat old-fashioned and slightly clumsy way, it suggests the work of a skilled provincial rather than that of the (presumably London-based) master craftsman who created the staircase. Nevertheless, the ornamental work here marks the chamber as probably the most important private or family room in the house,21 functioning almost certainly as a meeting place for the occupants of the pairs of rooms to its north and its south and as an anteroom for both. In this, it followed the approach employed in great country houses of the time of creating a grand sequence of interconnected rooms. Mrs Peckham could not quite manage to create the full effect in the relatively compact Pallant House, but by adding this chamber she was at least able to increase the sequence of rooms.

The number of bedchambers and apartments served by this ‘private chamber’ or anteroom is debated. The convention of the time dictated that husbands and wives in the wealthier echelons of

society had separate bedchamber apartments, often adjoining and sometimes sharing an anteroom, withdrawing chamber, closet/ cabinet or service staircase. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the pair of rooms each side of the anteroom served as apartments, including a bedchamber, one for Henry Peckham and the other for his wife, with the anteroom operating as their shared withdrawing room. The suggestion has been made that the smaller of the firstfloor front rooms was in fact a ‘study/sitting room’ (though the term ‘sitting room’ is very unlikely to date from the eighteenth century).22 That, however, doesn’t explain why this room, if not originally a bedchamber, retains a cupboard still fitted with original timber hooks on which to hang clothes, or a closet just large enough for a ‘close stool’, or lavatory, apparently connected to a cesspit in the basement below, with a door that still holds an early slide lock that can only be operated from within the closet. Clothes cupboards and close-stool closets are generally associated with bedchambers, not ‘sitting rooms’. Even in an early eighteenth-century provincial city, to emerge from a small unventilated close-stool closet directly into a room of seated guests would have been a somewhat unhappy and disconcerting experience for all involved. It should also be noted that the location of the service staircase between the front and back rooms on the north side of the house is a favoured location when the stairs are adjoining the chambers they are intended to serve – in this case a bedchamber and its related cabinet or withdrawing room. The convenience of the staircase – both for private movement within the house and for facilitating services – would have been ample compensation for the relative smallness of this pair of rooms when compared with the pair on the south side of the house’s first floor. If this room in the north-west corner of the house was not a bedchamber, the assumption has to be that Mr and Mrs Peckham defied the polite sleeping arrangements of the age and that rather than possessing their own separate apartments within their shared establishment, as all members of upper society at least aspired to do, were happy to spend the princely sum of £3,000 on a new, purpose-designed house that required them to ‘pig’ it together,23 on a nightly basis, in

the same bed in the same bedchamber. That this practice would have been known publicly would be guaranteed by gossiping servants. It is highly unlikely that the Peckhams would have invited this humiliation or risked the amusement and contempt of their local peers.

Of course, the other first-floor rear room, on the south side of the house, could have been used as a bedchamber, but this is unlikely. A rear room, overlooking outbuildings, a narrow lane and perhaps smelly stables, had a much lower status than a front room – as the relatively simpler decoration of the rear rooms in comparison to the front rooms makes clear. It would have been strange if husband or wife were obliged to occupy a bedchamber markedly lower in status than that of their spouse. If the two first-floor bedchambers did not occupy the two west-facing front rooms, then the whole convention of the floor containing two well-balanced apartments, each with bedchamber and cabinet or withdrawing room of reasonably equal status, is called into question. Given the date and status of the house, this is most unlikely.

While Henry’s bedchamber is lined with relatively simple panels (flat, not raised and fielded), Mrs Peckham’s apartment, with its bedchamber and cabinet or withdrawing-cum-dressing room, was more elegant. Such early panelling as survives – and a considerable amount does in the south- west room – is formed with raised and fielded panels set directly into frames embellished with ovolo, or quadrant, profile mouldings. In 1712 this would have been regarded as both elegant and fashionable, well suited to a lady’s bedchamber.24 The south-east room, which would have enjoyed morning sunlight, was most probably Mrs Peckham’s cabinet or dressing room, and has been much altered. We know from the Chancery documents that it was originally wainscoted to match one of the best-quality rooms on the floor below.25 In his evidence, James Burley, a 35-year-old joiner from Chichester, stated that Mr Peckham employed him ‘to wainscot a Roome called [the] drawing Roome Chamber’ on the ground floor and in his presence asked Mrs Peckham ‘how it should be done’. Her response was most revealing: ‘thereupon she went up stairs into her dressing roome’ with her husband ‘& desired that the said drawing

roome [should] be wainscoted like her dressing roome & it was done accordingly’. He also described how Mrs Peckham did not approve of the way her husband had ordered the dressing room’s door hung, so she ‘ordered the said door to be hung on the other side . . . and it was done accordingly’.

Why did Mrs Peckham want her door re-hung? The way a door is hung is significant: if the door opening is located in the corner of a room (which is generally the case in Pallant House) and if the hinges of the door are fixed to the post within the corner, then when the door is opened an immediate view is offered of the room and all in it. If the door is hung from the outer post, then the prospect is not revealed immediately to the person entering the room and those in the room see and hear the door opening and, while still screened, have a moment or two to prepare themselves for their visitor. Perhaps Mr Peckham had preferred the more ostentatious and baroque manner of entry, while his wife had deemed that a degree of initial concealment would be better for a lady’s dressing room.

The outline plan of Pallant House is roughly 3:2 (or a square and a half) in area, and it contains a number of rooms that are similarly roughly square in plan, or those permutations of a square – notably the 2:1 (double square) and 3:2 proportions – that were favoured by the Italian architect Andrea Palladio, expressed through his mid sixteenth-century north Italian villa and palazzo designs, and made available through his I quattro libri dell’architettura of 1570. There is nothing surprising in this, since Palladio had been a major influence in Britain from the early seventeenth century and his rational architecture – in particular his harmonically related system of proportions – had by 1712 long been an important part of the British classical design tradition. As for the disposition of rooms, the house takes the double-pile form that had become usual for houses designed in Britain from the mid seventeenth century onwards: two rooms deep, with corridor-like landings and halls used as circulation space. Previously, it had been necessary to pass through one room