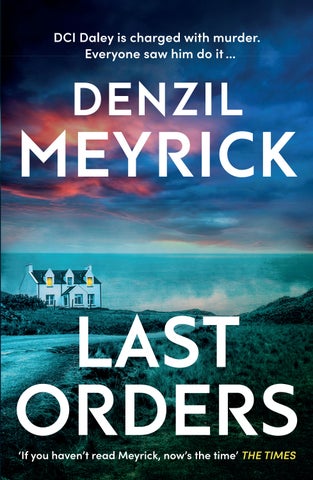

DCI Daley is charged with murder. Everyone saw him do it …

DCI Daley is charged with murder. Everyone saw him do it …

‘If you haven’t read Meyrick, now’s the time’ THE TIMES

Also by Denzil Meyrick

The DCI Daley Thrillers

Whisky from Small Glasses

The Last Witness

Dark Suits and Sad Songs

The Rat Stone Serenade

Well of the Winds

The Relentless Tide

A Breath on Dying Embers

Jeremiah’s Bell

For Any Other Truth

The Death of Remembrance

No Sweet Sorrow

Kinloch Novellas

A Large Measure of Snow

A Toast to the Old Stones

Ghosts in the Gloaming

Short-Story Collections

One Last Dram Before Midnight

Standalones

Terms of Restitution

The Estate

The Inspector Grasby Novels

Murder at Holly House

The Christmas Stocking Murders

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Denzil Meyrick Ltd 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

The lyrics on p. 103 are from ‘Let’s Go Out Tonight’ by The Blue Nile, written by Paul Buchanan.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 12.75/16pt Minion Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–0–857–50640–5

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The cemetery at Kinloch seemed chilly on the best of days. Cold winds from the sound funnelled out on to the loch, past the island that stood at its head, to tug at black ties, thinning hair, mourning dresses and widows’ weeds alike. Still, the community came to say goodbye, a last fond farewell to a man they’d known as intimately as if he were one of their own family. They gathered to mourn the loss of a soul, ready to be cast into eternity by means of a wooden box and a gaping hole in the ground.

This day was no different from so many sad occasions of its kind – or perhaps it was. The corpse in the sleek hearse, adorned with a large wreath rendered in the shape of a fish, had been a firm friend to most. A listening ear in times of trouble and a teller of tales tall enough to pass a long night at the roaring fire of any Kinloch hostelry. Some were in awe of the man, so expansive, warm in his personal dealings, only rarely a note of admonition, of dire warning.

Even the silent voices of the interred at this depository of the dead joined in the lamentation, though only those who had a particular gift could hear their ghostly whispers from beyond death’s great chasm. The very fabric of this old cemetery, they said, unlike others, was the thinnest of places, where this world all but touched the next. They huddled round the grave of one of Kinloch’s

legends, found dead in the streets of the town he had graced with his presence for so long. Young, old, man, woman and child alike, had tears brimming in their eyes, as the solemn undertaker and his men removed the coffin from the hearse, and went about the business of preparing it to be lowered down.

One woman, a niece of the deceased, cried out, as the polished wood encasement of eternity was placed above the grave on a pair of stout, wooden sleepers, its occupant now truly hovering betwixt this world and the next.

Tradition dictated that red winding cords attached at equidistant points around the casket be allotted to the selected mourners. Their numbers called out in order of seniority: the deceased’s closest relative taking the first, followed by other family members, friends and former colleagues.

The symbolism of each bearing the weight of one so close as he made his final journey, lost on nobody. One day it would be them – perhaps one of the people standing round this very tomb with the tight, red winds of wool would do the same job for them.

‘I hate this,’ said Brian Scott. ‘My faither always cried his eyes oot at funerals. I’m the same.’

‘Pull yourself together, Brian,’ said Jim Daley, standing tall, barely fitting into the suit trousers he was wearing. ‘We’re representing Police Scotland, remember. Wouldn’t do for you to lose your dignity, would it? Not as though you’ve ever done that before.’ He smiled. ‘But I know how you feel. I hate it too.’

‘Where’s Lizzie? I thought she was coming.’

Daley shrugged his broad shoulders. ‘She couldn’t face it. Always says she’ll be lowered down herself soon enough, without having to take in a rehearsal. It’s her usual mantra when she’s in bad trim. Her mother’s the same.’

‘She’s still in the doldrums, then?’

‘Yup.’ Daley’s expression was one of resigned acceptance.

The undertaker’s voice was a counterpoint to their whispered conversation, as he shouted out each cord number like a rollcall.

‘Number four, take your place, please!’ His cry echoed from the hills that huddled round the cemetery, watching over, embracing the dead of the town. A piper, standing on a rise, began the heartbreakingly beautiful lament ‘Flowers o’ the Forest’. To any Scotsman alive, and quite likely many dead, the skirl of this tune induced every soul present to shudder at the pain of loss, the exquisite sadness of final parting – thoughts of their own mortality never far away.

‘Number five, please!’ The call was slow, precise.

An expectant silence descended over the mourners.

‘Cord number five, take your place, please!’ The undertaker’s white hair was caught on a gust of wind, as his pale eyes searched those assembled. A low murmur overtook the mourners now. After all, number five wouldn’t be the first or last to take on the allotted task, only to find it all too overwhelming to bear. Every time this happened, though, the townsfolk looked on the recalcitrant individual with something approaching a mix of sympathy and loathing. Privileged as this task was, all attention belonged to the dead, not the coward unwilling to bear the weight of a solemn undertaking.

‘Hang on!’ A vision from haute couture’s worst nightmares wound his way through the throng. His kilt was too long, one sock flapped at an ankle while the other was raised above the knee, his waistcoat missed two buttons, and the black necktie in place round his neck was skewwhiff. ‘I had trouble finding my kilt!’ he exclaimed, as he hurried towards the yawning grave, still smoking his pipe.

The undertaker cleared his throat.

‘Oh aye, sorry aboot this.’ Hamish lifted one leg over the other knee and tapped the tobacco out of his pipe on the heel of his shoe. ‘Right, Willie, that’s me, carry on. Man, you’re doing a fine job, so you are. I have my cord.’

Unfortunate incident almost forgotten, and cords now distributed, the minister, his eyes still fixed on Hamish, began to speak.

‘Donnie Kerr was a fine man, friend to many, enemy of none. He was a pillar of the town’s fishing community. Honest, even-handed – a man to be admired, to look up to.’

‘Was he no’ a right chancer?’ whispered Scott into Daley’s ear, only to receive a trademark glare in return.

The minister’s voice then droned a hypnotic declaration of faith, his tones sometimes soft, modulated on the breeze, at other times loud, thundering appeals to God.

And so, in the manner and custom of this place, the laying to rest of Donnie Kerr, fish buyer, friend, counsellor, father, brother, son, uncle, husband, grandfather and, foremost of all, Kinlochian to his bootstraps, continued, as the grey skies that hung above the loch broke into silent tears of rain.

Glasgow, February 1997

Theblack BMW raced through the streets of Glasgow, its driver checking the rear-view mirror obsessively. As he turned sharply on to Clyde Street, he breathed a sigh of relief. There was no sign of the police car that had pursued him from the south side of the city.

He wondered where he could dump the car and continue his escape on foot. They knew the vehicle, that was true, but they couldn’t identify its driver. He’d made sure that he left only the merest impression on records of the criminal underworld. He could make off calmly, slow his breathing, sit in a pub for a while until the fuss died down. He’d be free of it, problems over.

Even though Glasgow was following other British cities, with deployment of CCTV street cameras growing by the day, most were focused on the road or certain shops favoured by the chief constable or members of the City Council. The places he’d go would leave their trail cold. Run-down old buildings, back streets, the remnants of a rapidly changing world. In with the new, out with the old, the relentless refrain.

People milled about under a leaden sky. The shops were brightly lit, their colours and those of the traffic lights popping like ripe fruit in the gritty city gloom.

Suddenly, though, something in the rear-view mirror caught his eye. The flashing blue light of the police car winked at him from way back in the slow line of vehicles. He cursed his luck.

He put his foot down, manoeuvring quickly through traffic, narrowly avoiding an ambling pedestrian as he went. The roar of the powerful engine filled his ears, punctuated only by car horns and the shouts of protesting road users.

He flew through a red light, narrowly missing a lorry. The split second was like a blur, a moment in time that could so easily have been fatal.

‘Shit!’ he yelled, as the shock, relief and horror of it all washed over him at once.

‘This guy’s off his rocker, gaffer! I think we should back off before someone gets hurt,’ said the uniformed constable driving Alpha Mike Three.

The detective inspector rubbed his chin with one hand, while holding on for dear life with the other.

‘That’s a negative, Lambie! If we don’t keep him in line of sight, he can skip the motor and we’ll never get him. This man needs catching, do you understand?’

‘Yes, got it, sir.’ Constable Gordon Lambie gripped the steering wheel even more tightly now, as he tried to emulate the movements of the vehicle he was chasing. Mercifully, the red light before him changed to green as he sped after the BMW. Lambie cursed the fact that he was driving a Vauxhall Vectra. In a straight race there was only one winner, and it wasn’t going to be the police car.

‘Look, he’s been boxed in!’ shouted the detective.

Lambie squinted ahead, wishing he’d never sat his police driving test, as advised by an older cop on his shift.

‘Who wants to be stuck driving a motor when Glasgow’s going like a fair? No’ me, son. Just stick to Shanks’s pony. Take the advice.’

The DI pulled at the wheel, making Lambie start. They mounted the pavement with two wheels.

‘In between that green Transit and the Escort, quick!’ shouted the DI.

Constable Lambie shut his eyes as he executed the manoeuvre, waiting for the sickening scrape of metal on metal. Thankfully, it didn’t come.

As he looked on, he could see the BMW forcing its way past the little huddle of cars that blocked its path, black smoke belching from its tyres as the engine revved. They were within twenty yards of the Beamer now, but they’d have to keep up the pace.

The black car accelerated on to an open stretch of road.

‘Come on, man!’ roared the detective.

The constable didn’t know when he first realized what was going to happen. The scene played out as though in slow motion. As he pulled past the last two cars between them and their quarry, he saw an orange corporation bus emerge in front of the BMW from a side street. The driver tried to swerve to avoid the collision, but he was too late. The BMW caught the bus a glancing blow and reared up like a plane taking to the skies. The vehicle rolled in mid-air over an empty road and pavement mercifully free of people.

As the police officers looked on, the BMW hit the barrier between road and river, somersaulted over it and landed in the Clyde with a crash and a great plume of

smoke and water. Pedestrians screamed; one old man, drenched by the displaced river that landed on his head, shook his fist in the direction of the BMW, true to his Glaswegian spirit.

Lambie pulled in to the side of the road. He and the detective exited the police car. They gazed into the Clyde just in time to see the vehicle they’d pursued for almost twenty minutes sink below the brackish water in a flurry of steam, smoke and the acrid stench of burning rubber and spilt fuel, its alarm wailing in protest, gradually dulling due to the immersion. Despite being submerged, flames leapt from the vehicle’s engine in flares, illuminating the river with the burning fuel that was resisting the dousing force of the Clyde.

Lambie looked on as the detective beside him stripped off, ready to dive in and rescue the driver. But as he tore at his shirt, there was a low rumble, followed by an earsplitting explosion. The River Clyde danced with the flames from the stricken car, as the residue of petrol ignited on its brown waters. A tower of black smoke rose in the air in a small mushroom cloud. People screamed, stopped and stared, the morbid fascination of death too compelling to ignore.

‘Fuck!’ the detective cursed.

‘You’ve nae right racing roon the place chasing folk. Look what you’ve done!’ shouted a young woman with a pram. ‘It’s a fucking disgrace, so it is! My wean shouldnae be exposed tae this shite!’

Lambie began to shiver. He could hear the distant sirens of the approaching emergency services. He bent double and spewed on to the pavement.

‘Not your fault, son,’ said DI Jim Daley, consoling the man whom he’d encouraged to chase the BMW. A tyre

blew from the submerged vehicle with a great pop, sending a large murmuration of starlings, soaring as one, from under a nearby railway bridge into the grey sky. It was almost as though they flew with the recently departed soul of the driver, now surely embarking on its final journey.

Present

DIBrian Scott was sitting uncomfortably in Jim Daley’s lounge. Despite the fabulous view of the loch and the hills and mountain beyond, he focused on the marching headstones of the cemetery across the still waters where they’d been only weeks before. He wasn’t sure whether it was this silent presence of death or the argument raging from the kitchen that made him most melancholy. Bit of both, Scott reasoned.

DCI Jim Daley and his wife had never enjoyed the easiest of relationships. The former was as solid as the rock of Gibraltar, a sometime introvert of great depths and fluctuating mood. Liz was the opposite: gregarious, glamorous, witty – often cuttingly acerbic in her assessment of others. She loved holidays, parties, being amongst friends – life –though they both loved their son James junior dearly, and in equal measure.

Scott often wondered what had drawn the pair together. Then again, he reasoned, he and his own wife had many differences in personality. She was organized, determined and resourceful. He took out the bins.

As though someone had turned down the volume, the voices from the kitchen fell silent. Scott heard the heavy tread of his old friend as he made his way up the hall towards the lounge.

‘Tea, wasn’t it, Brian?’ said Daley, his head popping round the door.

‘Ach, nae bother, big man. We better get a move on and get to the office. We’ve that doom call from the boss to suffer.’

Daley smiled at Brian Scott’s regular interpretation of a Zoom call.

‘Yes, you’re right. I don’t know where the time goes, Bri.’ He wandered to the mirror above the fireplace, knotted his tie and ran a hand over his cropped dark hair with a comb.

‘Up its own arse, if you ask me, Jimmy.’

‘Well put.’ Daley smiled weakly. ‘I better go and kiss Liz goodbye.’

Scott lowered his voice. ‘I’d be careful she doesnae bite your nose off. Man, you were going at it in there.’

‘It’s the move.’ Daley shrugged. ‘She doesn’t like it. She’s been like this for months.’

‘But she was the one who never wanted to come down here in the first place.’

‘Well, that was before, apparently. She’s made friends now. Her photography’s selling on that website. She thinks this is a really good place to bring up young James, blah, blah.’

‘Aye, I can see that. So, what are you going to do?’

‘I’m going up the road myself for a few weeks, try and find a place that’ll suit. I know you and Ella will keep an eye on them both. Once she sees a nice new house, things should get better.’

‘It’s no’ going to be easy.’

‘You don’t need to tell me, Bri. But if you could do me the favour, I’d be grateful.’

‘I don’t mean difficult for me and Ella. I mean for you and Liz.’

‘Right, I see. Yeah, it will.’

‘Won’t be easy up in Dumbarton, neither. You’re the big boss now, my man. Head o’ CID across the division.’

‘And don’t forget, you’ve got my old job to be getting on with.’

Scott sighed. ‘I won’t let you down, pal. I know you had to use all your powers o’ persuasion to get this one across the line.’

‘And then some.’

‘Alistair Shaw says you telt them you wouldn’t take the job unless I replaced you here. Is that true?’

‘Alistair Shaw should learn to keep his mouth shut. He’s no saint, as we all know.’

Scott raised his brows. ‘None o’ us perfect, big man.’

The door swung open, and Liz appeared.

‘How you doing, Lizzie?’ said Scott, and instantly wished he hadn’t.

‘I’m just fabulous, Brian. Life’s a dream. My husband, who dragged us all down here in the first place, now wants to drag us all back from whence we came. It’s great, isn’t it? No thought for young James and his friends at school. And as far as I’m concerned, forget it.’

Scott opened his mouth to reply, but on reflection snapped it shut again. He’d seen this movie many times before. And with a tendency to make matters worse rather than better, he followed his wife’s long-term advice and said nothing.

‘We need to go, Liz.’

‘Great! To be continued then,’ she replied. ‘I’ll look forward to it.’

Daley and Scott drove across Kinloch in silence to the office, Daley brooding as he gazed out at the loch sparkling in the morning sunshine.

Hamish was weary, very weary. A man who’d spent most of his life rising with the sun, and long before in many cases, he lay in his bed staring at the ceiling, and it was nearly nine o’clock in the morning. He stroked the half-breed wild cat curled up on his chest as he pondered a great flap of paint peeling from above.

‘These damned dreams, Hamish,’ he said to the cat he’d named after himself. ‘I just canna shake them.’

Hamish the cat mewled, almost as though it sympathized with its master’s plight.

The old man lay there until the phone at his side on the nightstand burst into life.

‘Kinloch two-two-seven-eight, Hamish speaking.’ It was a mantra he’d repeated ever since he’d had a phone installed in the late eighties. This, despite the near certainty that the call would be somebody trying to sell him double-glazing or insurance.

‘Are you still in your bed?’ The voice on the other end was haranguing in tone. ‘I can tell by how quickly you answered the phone. It takes you ages when you’re in the living room.’

‘Aye, and what about it, Ella Scott?’ replied Hamish, most definitely on the defensive, but quietly impressed by his interlocutor’s observation.

‘Well, you’ll need to get across here later. It’s Tommy Cunningham’s birthday. And you know fine he’ll want you to be there.’

‘Tommy, aye, he can take a fair swallow, right enough. No wonder you’re so keen to have a party for him at the County, though I’m no’ sure why he bothers going out to get drunk on his birthday. He’s out drunk every day of the week. He should stay in with a cup o’ tea and make the day special.’

‘Full of the joys today again, I hear,’ said Ella.

‘You’d be the same if you’d no’ had a wink o’ sleep for nights on end.’

‘You should get something from the doctor, Hamish. You cannae go on like this, a man o’ your age.’

‘Take pills? You know me. Sleep should be achieved naturally or not at all. Before you know it, I’ll be hanging about at the surgery corner with a hole in my trousers, fair begging for stronger potions to keep me square. I know where that path leads, an’ no mistake. My body’s a temple, filled with natural things, like fish.’

‘Aye, and they’re swimming in whisky.’

‘I’ll have you know whisky is a cure-all for any kind o’ malady. Is it not just three weeks ago a bit of rusty metal got stuck under my fingernail and it got poisoned? The doctor wanted me up the road to have it removed. I just bathed it in a glass of whisky – the cheap stuff, you understand. Before I knew it, the obstruction had gone, and my finger was as fresh as a wean’s backside.’

‘It’s a miracle!’ said Ella sarcastically.

‘You’d have me on they dopioids until I was pissing where I sat. That day might come, Ella, but it’s no’ here yet.’

‘Such a pleasant image.’ She sighed and continued. ‘I’ll expect you tonight. I’ve not seen you for nearly a whole

week. Aye, and there’s plenty drams lying behind the bar for you from well-wishers. So, I doubt you’ll have to put your hand in those shallow pockets of yours.’

‘I’ll think on it, Ella. It’s kind of you to check in on me.’

‘Somebody has to. I’ll have Brian come down there and drag you to the County!’

‘Man, many a time I’ve seen the polis drag folk oot o’ pubs. I didn’t think they performed the whole process in reverse. Now, there’s a thing.’

‘I’ll see you later.’ With that, Ella ended the call.

Though Hamish missed her predecessor, Annie, he’d become used to Ella Scott behind the bar at the County Hotel. She was a kind woman, despite her sharp tongue. Mind you, he reasoned, it took a sharp tongue to keep Brian Scott in order.

Hamish ushered the cat from his chest and sat up. He levered himself out of the bed and, in his tattered slippers and frayed tartan pyjamas, padded into the lounge, past the plaster bust of Winston Churchill atop the rough table made from fish boxes, and into his tiny kitchen – or galley, as he liked to think of it. He put the kettle on the gas hob to boil for his tea then sat himself at the kitchen table.

Hamish rubbed the sleep from his eyes and stared at the book before him. It was London from the Air, photographed by a gentleman called Joseph Hiscox. He’d bought it at a sale of work held in aid of the church, no more than a month ago. And since then, he’d stared at one image again and again. On pages forty-six and forty-seven, the great River Thames meandered like a huge serpent through the city. He followed its course with the tip of his stubby right index finger. The whole exercise made him shiver, and he felt the same sensation of despair he’d experienced in every dream he’d had for weeks on end.

Hamish banged his fist on the table.

‘Damn me! Stop torturing yourself, man.’

Only the insistent whistling of the boiling kettle roused him from these dark thoughts. The old fisherman knew that something was wrong – very wrong. Had it been the loch outside his window that haunted his thoughts, maybe he could have fathomed what was going on. But he had no connection to London, much less the Thames. The troubling nightmares remained a mystery.

Hamish sat back with his strong tea, resisting the temptation to lace it with a dram. Quickly reasoning that it was a bit early, even for him.

‘Aye, what’s it all about?’ he said to himself quietly.

Daley and Scott sat in the AV room at Kinloch police office, the huge screen in front of them flickering as Sergeant Alistair Shaw hammered away on a computer console.

‘Bugger me, Al, have you no’ got the hang o’ this yet? It’s been here for years, man,’ said Scott, regarding the lack of a connection with a jaundiced eye.

‘You’ll remember what the wifi signal is like here in Kinloch, Brian. It’s not as easy as it looks. We’ll have to go on to Starlink if I can’t get the broadband to work.’

‘As long as you beam the boss up before me,’ said Scott.

Daley checked his watch. They were due to join the assistant chief constable in two minutes. If they didn’t, it would reinforce the theory at HQ that everything in the sub-division was calamitous. He supposed it was no longer his problem. His new role as head of divisional CID would land the responsibility firmly on Scott’s shoulders.

Did he think his old friend was up to the challenge?

Yes, he did. But such were the shifting sands of regulations governing police officers’ lives, he did have a concern that Scott – firmly anchored sometime between the Dark Ages and the eighties in policing terms – might struggle to adapt. Daley decided not to worry about it.

‘There we go!’ exclaimed Shaw, as the jaggy thistle Police Scotland logo appeared on the screen. ‘Can you say something for sound levels, please? One after the other.’

‘Testing, testing, one, two, three,’ said Daley in a steady voice.

‘All cops are bastards!’ shouted Scott, repeating the chant often heard on the football terraces.

‘I beg your pardon?’ said ACC Sam Jordan, his face filling the screen. He was one of the youngest officers to make it to the ranks of assistant chief constable. He was also notoriously difficult. He raised his chin, blue eyes flashing. ‘Tell me I didn’t hear that!’

‘Naw, it’s absolutely fine, pal – sir. Me and Jimmy, we was just discussing a case,’ said a flustered Scott.

Daley marvelled at the way Brian Scott delivered this lie without hesitation, deviation or a red face.

‘DI Scott, I hope you realize it’s time to screw the bobbin, as I’m sure you say.’

‘Aye, sir, definitely. Spot on!’

Daley raised his brow in frustration. At the same time, he knew there was nothing he could do about Scott’s propensity to put his foot in it. He also knew there was nobody he’d rather have at his side in times of crisis. Things had a habit of balancing themselves out for the best in the long run. And Scott always seemed to be just on the right side of the balance sheet when the numbers were totted up.

‘I take it the handover is going well, DCI Daley?’

‘Yes, sir. That is to say, DI Scott is intimately acquainted with the environment and our procedures. This won’t be the first time he’s taken charge, of course.’

ACC Jordan flashed a youthful smile. ‘Yes, I seem to remember a memo that pointed out he had ten officers on

one shift and two on another. An odd deployment of personnel, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Intelligence, sir,’ said Scott.

‘Really? That’s a surprise. I didn’t know you had any.’ Jordan’s turn to raise a brow.

‘A tip-off about a squad o’ bikers heading this way. You can’t be too careful in the rurals, sir. Get it wrong, and you’re on your own.’ Scott sat back, looking pleased with this explanation.

‘The same as threatening to defecate in someone’s dinner?’

‘No, that was a joke, sir. Taken the wrong way by the humourless bastard concerned.’

‘The humourless bastard being a frail man in his eighties.’

‘I don’t think he was anywhere near that age.’

‘DI Scott, do you know that you are one of the main topics of conversation at the Senior Officers’ Association dinners? Oh yes, how we laugh – and cry.’ Jordan leaned into the screen, making his head even larger for those watching in Kinloch. ‘No more jokes, Brian. Got it?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Scott.

ACC Jordan sat back. ‘Now, I have some information to impart. It’s come from Special Branch in London.’

‘Sir?’ said Daley, already intrigued.

‘It would appear we’ve had a security breach. It was so well executed, we didn’t notice ourselves. Took the boffins from the Security Service to pick it up. They passed it on to the Met. It would appear as though your records have been compromised, DCI Daley.’

‘In what way, sir?’

‘Your entire service record was accessed. Every dot and comma of your career. Only your records – nobody else is involved.’

‘What for?’ Daley looked nonplussed.

‘No idea, Jim. Though it’s fair to say you have rattled a few cages in your time. Both in the underworld and in police circles. We’ve decided to install a panic button at your domicile in Kinloch, as well as wherever you intend to lay your head when you take up your new post.’

‘A panic button? So, my family are in danger? Is that what you’re saying, sir?’

‘Just a precaution. There’s absolutely no intelligence that marks you out as a target of any kind. No internet traffic, either. Dark web included. Probably some spotty teenager in his bedroom trying to prove how smart he isn’t. You know the score. At worst, some idiots testing our response. Nothing to do with you, per se.’

‘My wife and son will be on their own when I go back up the road, sir. I feel uncomfortable about it now. Panic button or no.’

‘They won’t be joining you?’

Scott looked at the floor, knowing the prospect of Liz Daley and their son making the move to Dumbarton looked reasonably unlikely.

‘It’s complicated, sir. Schools, my wife’s job, housing – that kind of thing.’

‘And yet you told us when you were interviewed that none of this would be an issue.’

Daley bit his lip. The last thing he’d expected was for Liz to be difficult about moving back to civilization, as she was wont to call it since their arrival in Kinloch. ‘It isn’t a problem, sir. Honestly, just taking a little longer than I expected to get the logistics organized.’

‘Good. The last thing we need are any domestic setbacks. I need you to help us lower the crime rate in your new job. Bloody Edinburgh is on our back – at the very highest

political levels. And if you have any lingering concerns, well, I’m sure the scheduling genius that is DI Scott will be able to spare an officer or two to look after your family before they join you in your new home. Isn’t that right, DI Scott?’

‘Aye, you’ve nailed it there, sir. Bang on, chief,’ Scott replied with rather too much gusto.

ACC Jordan looked at his desk before addressing his charges in Kinloch once more. ‘This will be in your inbox by now, gentlemen. But I thought I’d mention it too. We have a missing person, believed to be heading your way. When I say missing, I should say absconded.’

‘Who, sir?’ said Daley and Scott, almost in unison.

‘You probably won’t remember him, Jim. It’s a long time ago. Gordon Lambie, a former constable from Stewart Street.’

Daley puzzled over the name. It wasn’t ringing any bells.

‘I remember him,’ said Scott. ‘Drove you a few times – the Cherwell case, Jimmy. The motor in the Clyde.’

At Scott’s prompting, Daley recalled Lambie. He’d been at the wheel of the car when they’d been chasing Anthony Cherwell. The elusive figure who’d brought a huge quantity of high-grade heroin into the city that had killed addicts left, right and centre. It took them weeks to identify him as the man who’d died in the submerged car. He had no previous criminal history; in fact, the reverse. Cherwell had been a high-flying businessman before he discovered an easier way to make money.

‘Yes, sir. I remember Lambie now. Highly strung. Blamed himself for the accident and Cherwell’s death.’

‘Yes, left the job not long after. Drifted into alcoholism and worse. He was sectioned when he tried to kill his wife and son with a carving knife, albeit in a half-hearted

manner. Been away ever since. He managed to escape during a private psychiatric appointment out with the State Hospital. He’d been telling other inmates he was going to do it, and head to Kintyre. Your name was never mentioned, Jim. But there’s the connection to Cherwell and that car chase. I’m sure you understand.’

‘I do, sir,’ said Daley.

The rest of the meeting went as planned. When Jordan’s face eventually disappeared from the screen, Scott slumped in his seat, found his cigarettes and lit one.

‘How many times, Brian? You can’t smoke in the office!’

‘Ach, who’s to know, Jimmy? Are you going to fire me?’

‘No, I’m going to throw a bucket of water over you.’

‘Lambie, eh? There was an odd one, right enough.’

‘I felt sorry for him. He genuinely blamed himself. Couldn’t hack it, the lad. I should have done more for him.’

‘He wasn’t your responsibility, Jimmy. That’s why we have Human Resources. Not that they give two fucks.’

‘Exactly, Brian.’

‘I bumped into him in Glasgow once. Man, he was in some state. Looked like a tramp. I gave him a twenty spot.’

‘Which he no doubt used to buy booze.’

Scott shrugged. ‘What are you going to do, eh? You’re not worried about him, I hope. But they files, that’s creepy, don’t you reckon?’

‘I do. It’s just another worry, to be honest.’

‘Don’t even think about it, pal. You know fine I’ll look after Liz and the wean when you’re away. Surely you trust me to do that?’

‘I do. Without question.’ Daley thought for a moment. ‘We’re planning a break before I go. Just the two of us. You know how she loves a weekend in London.’

‘Oh aye. Spends a fortune, if I remember right.’

‘Oil on troubled waters. Would you and Ella mind looking after the wee chap?’

‘Aye, no bother. I’ll be about if she’s at work. And I know you’ve got that child minder. You know we love having the wee fulla.’

‘I do. Thanks, Brian.’

‘Don’t you go worrying about everything. Mountains and molehills. There’re some right weirdos on the internet, and as far as Lambie’s concerned, just forget him. All is rosy, big man.’

Daley smiled, but it was with a heavy heart that he left Kinloch police office comms room.

Theold hotel in the Mid Argyll village had seen better days. Paint was peeling everywhere, doors creaked open and shut, the windows were cracked and grubby, and the carpet was sticky enough for guests to believe it was trying to forcefully prolong their stay.

The hotel was isolated, off the main route through the county. Best of all, nobody cared who came and went. The dishevelled man in the grey sweatshirt, jeans and old trainers, his goods and chattels in a large plastic carrier bag, attracted no comment when he arrived brandishing a pre-paid credit card. The staff had seen many stranger sights.

He’d lain low, mostly ordering his meals via room service. His daily routine for the last five days had been to scale the small hill behind the hotel to check the distant road and surrounding landscape, though he was pretty sure nobody would find him here.

Thoughts of living out his life in this place were appealing – until, that was, he remembered the funds that had been paid into his credit card were hardly limitless.

He stared at his reflection in the broken dressingtable mirror. His dirty grey hair, unshaven wrinkly face that sagged with bags, and washed-out eyes. He could

easily have passed for a man twenty years older than his actual age.

But none of that mattered now. Gordon Lambie had lost everything – his job, family, dignity, and any sense he had of himself. In short, he was a husk of the younger man who’d once had so much ambition. The bright schoolboy who should have gone to university, until his overbearing father insisted he get a proper job and join the police or the military. He’d chosen the former; the lesser of two evils, he’d reasoned at the time.

Lambie reached into the pocket of his jeans, his hand trembling from the lack of the alcohol to which his body had become accustomed. He pulled out a crumpled piece of paper; a young police officer, eyes wide, stared from the newspaper clipping.

The journalist and photographer had caught him by surprise, leaving the front door of Stewart Street police office, ready to walk the beat. Since the chase a few weeks before, he hadn’t been permitted to drive police vehicles.

SHOULD

The headline was stark, brutal. He had become the poster boy for injustice; the nuance being that he was also the embodiment of an oppressive police force. A man who cared nothing about chasing down another human being until they died in a flaming, submerged horror.

But Gordon Lambie knew all he’d done wrong was to follow orders from the big, obsessive detective inspector whose face didn’t stare from the pages of the newspaper. No, his seniority enabled anonymity.

‘I fucking hate you, Daley!’ he shouted at the top of his voice. He’d used those words like a mantra for more than

twenty years. They slipped off the tongue like the lyrics to an old song or lines from a treasured poem. It was time to put things right, once and for all.

Lambie picked up the bus timetable the woman at reception had given him. He had to catch the bus to Lochgilphead on the side road near the hotel, then onwards to Kinloch.

Gordon Lambie knew exactly what he was going to do once he got there. He’d gamed it out over and over again in his mind. It would be sweet, sweet revenge. He lay back on his bed and played the same movie out in his head. It was one he’d seen a thousand times. Then, more quietly this time, ‘I fucking hate you, Daley. It’s time for you to find out how my life feels.’

Lambie had been studying the hotel and its staff since his arrival. Overall, it was a quiet place, with a few guests here and there, plus a couple of older people who appeared to be long-term residents, likely paid for by the council.

A tall, ruddy-faced man called Shearer was grandly called the head chef, though his actual duties consisted more of knocking up some old standards like fish and chips, tarting up cuts of beef, mince and tatties, cauliflower cheese for vegetarians and some off-the-cuff desserts. Quite often, he heated meals in the microwave. He was assisted by a spotty youth, who said very little and followed his mentor about silently, while constantly checking his phone.

Irene was the receptionist-cum-manager-cum-barmaid. She was a cheery soul who smiled and said all the right things. Uncomplicated, just the way Lambie liked it. These three members of staff, plus the odd chambermaid and regular customers, often sat themselves in the bar at half two every day, just after it closed for the afternoon. They’d

pass the time of day over a few drinks or a coffee before the place reopened at six and the kitchen began its business for the evening.

Sure enough, when Gordon Lambie walked into the bar, there they all were – the chef and his assistant, Irene; an old soak he’d seen often who was a resident; and a young woman he marked out as a cleaner, mainly because she was sitting beside a bucket and mop.

‘Mr Daley, come in and join us,’ said Irene cheerfully. ‘You know how we love a wee soiree in the afternoon.’

Lambie knew his alias was a risky one, but it was the first name that had come to mind when the pre-paid card was arranged for him.

‘You’re fine – but thanks for the offer. I’m a bit knackered, just been up the hill. It’s quite hot out there.’

‘You should try that bloody kitchen,’ said Shearer. ‘Totally roasting, man.’

‘I don’t envy you your job in this weather, Mr Shearer.’ Lambie leaned on the sticky Formica counter. ‘Could I have a can of Coke for my room, please? I fancy a wee lie down.’

‘Sure thing,’ said Irene, manoeuvring herself off the high stool. ‘Will I just stick it on your bill?’

‘Aye, that would be fine, thanks,’ Lambie replied.

Irene handed her guest the can of Coke. ‘Are you joining us for dinner this evening, Mr Daley?’

‘Yes, I’ll be down about seven.’

‘Fish and chips again, is it, Mr Daley?’ the chef asked.

‘I do like my fish and chips, Mr Shearer. Can’t get enough.’ He smiled awkwardly then grabbed the Coke. ‘Have a nice afternoon, folks.’ He nodded and made his way out of the bar.

‘He’s such a nice man,’ said Irene in an undertone she no doubt thought wouldn’t be heard.

‘Fucking weirdo, if you ask me,’ said Shearer. ‘I mean, who has the same meal every night, eh? Plus, all the moping about. No’ the full shilling, if you ask me.’

Lambie had lingered at the door and heard every word of this exchange. It didn’t bother him in the slightest. After this was over, everyone would know just what kind of man he was.

A long corridor ran from the hotel’s front door, past the bar entrance, the toilets, and then to the kitchen at its very end. Lambie held his breath as he looked about before he made his way down it.

The kitchen was a mess. Dirty dishes piled high in two sinks, filthy worktops, shelves, hotplates and cookers. Lambie felt a few moments of revulsion at the thought of having eaten food from this awful place. He swallowed back the retch in his throat and looked around. In a way, it was better for him that such chaos reigned in the hotel kitchen. They wouldn’t miss a thing, he reckoned.

Lambie found two knife blocks, with various sizes and shapes of the utensils nestling in little slots. The first block looked new, the hilts of the knives untarnished and clean. The older block was stained and shoved to the back as though no longer in use. When Lambie pulled the largest knife from its slot, though, he was pleased to see that the blade gleamed. It would do. He threaded the knife through his belt under his jumper and stacked up some clean pots in front of the knife block. In this mess, nobody would miss it.

He was about to exit the kitchen when he heard the pad of feet walking down the corridor outside. In his panic, Lambie pinned himself against the wall, knowing that, when the door was opened, he’d be hidden from sight.

The marching feet stopped, and Lambie held his breath,

a bead of sweat dripping down his nose. It seemed like hours before he heard the tell-tale squeal from the men’s toilet door as it was pushed open on its transom.

Lambie waited a few seconds and edged himself out of the kitchen door. Almost on tiptoes, he crept silently past the toilets, down the corridor and out into the lobby. He took the stairs to the second floor and his room two at a time, being careful not to trip on the threadbare carpet. He breathed a long sigh of relief as he closed the bedroom door behind himself.

Lambie removed the carving knife from his belt and examined it. He ran his index finger down the blade, smiling when his own blood appeared as a crimson line on a fingertip.

‘You’ll do the job nicely,’ he mumbled to himself as he opened the bedside drawer and hid the knife under some brochures. Silently, he played out what he intended to do in his mind and smiled.

Hamish was dozing in his old armchair, his feline namesake off on his nightly visits to the hill to chase rabbits and any other creature that moved. Eventually, he’d come back through the improvised cat-flap Hamish had cut in the back door, pad to his master’s bed and sleep, his thirst for murder sated for another evening. The old man loved the half-breed wild cat. It was one of the few things from which he took solace these days.

The old wireless was crackling out some big-band standards. They penetrated Hamish’s restless sleep and set the fisherman dancing in his dreams with old girlfriends and lost loves. But when Hamish embraced Sandy Hoynes, his former skipper, readying for a waltz, he muttered himself awake.

‘Good heavens, Sandy. I loved you dearly, but no’ enough to take you for a spin round the floor.’ Hamish mashed his dry mouth and contemplated the brewing of yet another cup of tea. Unusually for him, such was the intensity of his nightmares, he’d tried to stay off the whisky; that was just making things worse.

He stared over at the plaster bust of Winston Churchill. ‘Aye, Winnie. Just like yourself, I’ve got a dose o’ the black dog, I’m thinking. Though the whisky isn’t working for me

just as well as it did for yourself. Mind you, I’m no’ the civilized world’s last hope. I’d have been fair guttered every night if I’d to suffer your responsibilities.’

Just as Hamish was contemplating levering himself from the armchair, an insistent knock sounded at the door.

‘Och, bugger it. Who’s that at this time o’ night?’ He shuffled across the living room, switched off the wireless and went out into the small lobby. ‘Who’s there? I’ve got a poker in my hand, aye, and I’ll fair plant you a dunt on the heid if you’ve robbery in mind!’

‘It’s me, you daft old bugger,’ said the voice from behind the door.

Hamish struggled with two latches and a mortise key before he could open the door. ‘Brian. It’s good to see you. Come away in.’

Scott sat himself down on the sofa, sinking as he always did into its oft-used cushions. His eye caught sight of a large, black spider making its way slowly but determinedly along the mantelpiece. It made its way over the man of the house’s briar pipe, before disappearing into a crack in the wall.

‘Is it a cup of tea you’re after, Brian?’ said Hamish.

‘No, you’re fine, thanks. I’m here on a mission.’

‘I know fine why you’re here, Brian Scott. That wife o’ yours has sent you down to pressgang me to Tommy Cunningham’s party.’

‘Aye, that’s right. And you know what Ella’s like when she gets a bee in her bonnet; cannae wait until it’s out flying round the room wae everyone chasing aboot after it.’

‘Well, the bee will have to stay where it is, for I’m no’ the least inclined for partygoing this night.’ Hamish sat on his chair and folded his arms.

‘You’re looking a bit grey about the gills, old boy, if you don’t mind me saying,’ Scott observed.

Hamish shook his head and told Scott of his dreams.

‘What kind of dreams, Hamish?’ asked Scott. In anyone else, he’d have overlooked this problem. But he knew from bitter experience that the workings of this old man’s head were to be ignored at risk of some peril.

‘Deary me, I was dozing here in front o’ the fire, and just about to take the floor with Sandy Hoynes! My heid’s all over the place.’

Brian Scott made a face. ‘Hoynes? Is that not your old skipper – the man that taught you all you know?’

‘Aye, he did that. But the Boston Two-Step wasn’t included, I’m here to tell you.’

‘We all get bad nights from time to time. I know I’ve had a few.’

‘Aye, wae your noggin filled with a bottle and a half of whisky, I don’t doubt it.’

‘You’re a kind man, Hamish,’ said Scott with a curl of his lip.

‘It’s no’ so much the manner o’ the dreams. Though they’re unsettling enough, no question.’

‘What then?’

‘It’s the location. Every night I’m down in London, down by the Thames. Every damn night.’

Scott’s heart missed a beat, but he chose to ignore it. In any case, Hamish couldn’t possibly know that the Daleys were about to take a break in the city. ‘Is it you and auld Hoynes jigging doon Piccadilly, eh?’

‘I might have known you’d be of no help.’

‘Hamish, it’ll just be some memory of London from a way back.’ Scott looked round the room. Remembering Hamish’s aversion to television, he altered what he was going to say. ‘Maybe something you’ve heard on the wireless?’