LEGENDA

Also by Janina Ramirez

The Private Lives of the Saints

Femina

LEGENDA

The Real Women Behind the Myths That Shaped Europe

Professor Janina Ramirez

WH ALLEN

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

WH Allen is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by WH Allen in 2025 1

Copyright © Janina Ramirez 2025 Maps © Helen Stirling 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by seagulls.net

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN 9780753560419

Trade paperback ISBN 9780753560426

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To Dan, Kuba, Kama and the Maleczek Clan.

Maggie Moo, you got me through!

‘Women … will speak now, and cannot be silenced; their characters and their eloquence alike foretell an era when such as they shall easier learn to live true lives.’

Margaret Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, 1850 ed.

‘Be silent no more!

Cry out with one hundred thousand tongues. I see that, because of this silence, the world is in ruins.’1

Catherine of Siena, ‘Letter to a Grand Prelate’, c.1375

1 France: Revolution and Reinvention 15

Joan of Arc (1412–31) and Charlotte Corday in 1793

2 The Iberian Peninsula: Dynasty and Discovery 69 Isabella of Castile (1451–1504) and Agustina Raimunda Maria Saragossa in 1812

3 Greece: Autonomous and Atypical 111 Anna Komene (1083–1153) and Laskarina Bouboulina in 1829

4 The Low Countries: Exceptional and Extreme 149 Marie of Oignies (1177–1213) and the Beguines, and the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur in 1831

5 Germany: Bonds and Bloodlines 193 Empress Adelaide of Bavaria (931–999) and Lola Montez in 1848

6 Italy: Piety and Papal Power 237

Catherine of Siena (1347–80) and Anna ‘Nina’ Morisi in 1858

7 Britain: Traditional and Transnational 279

Lady Godiva (died c.1066–86) and Queen Victoria in 1857

Preface

1 May 2017, Paris, France

Journalists swarm the car from all sides as two figures dressed in red are bundled out of its back doors and escorted onto the Rue des Pyramides. Microphones and cameras are thrust into the faces of the individuals, both of whom are pushing 90. Jean-Marie Le Pen and his Greek-Dutch wife Jeanne-Marie Paschos are surrounded by security guards as they bustle forward, smiling and talking to supporters. Jean-Marie has a large sprig of lily of the valley as a buttonhole – a symbol of the woman who rises up in front of them: Joan of Arc, astride a huge horse, holding her banner aloft. She described her banner herself during her trial:

I had a standard whose field was sown with lilies. There was a figure of Christ holding the world and on each side of Him was an angel. It was made of a white fabric called ‘boucassin’. Written above: Jhesus Maria, and it was fringed in silk.1

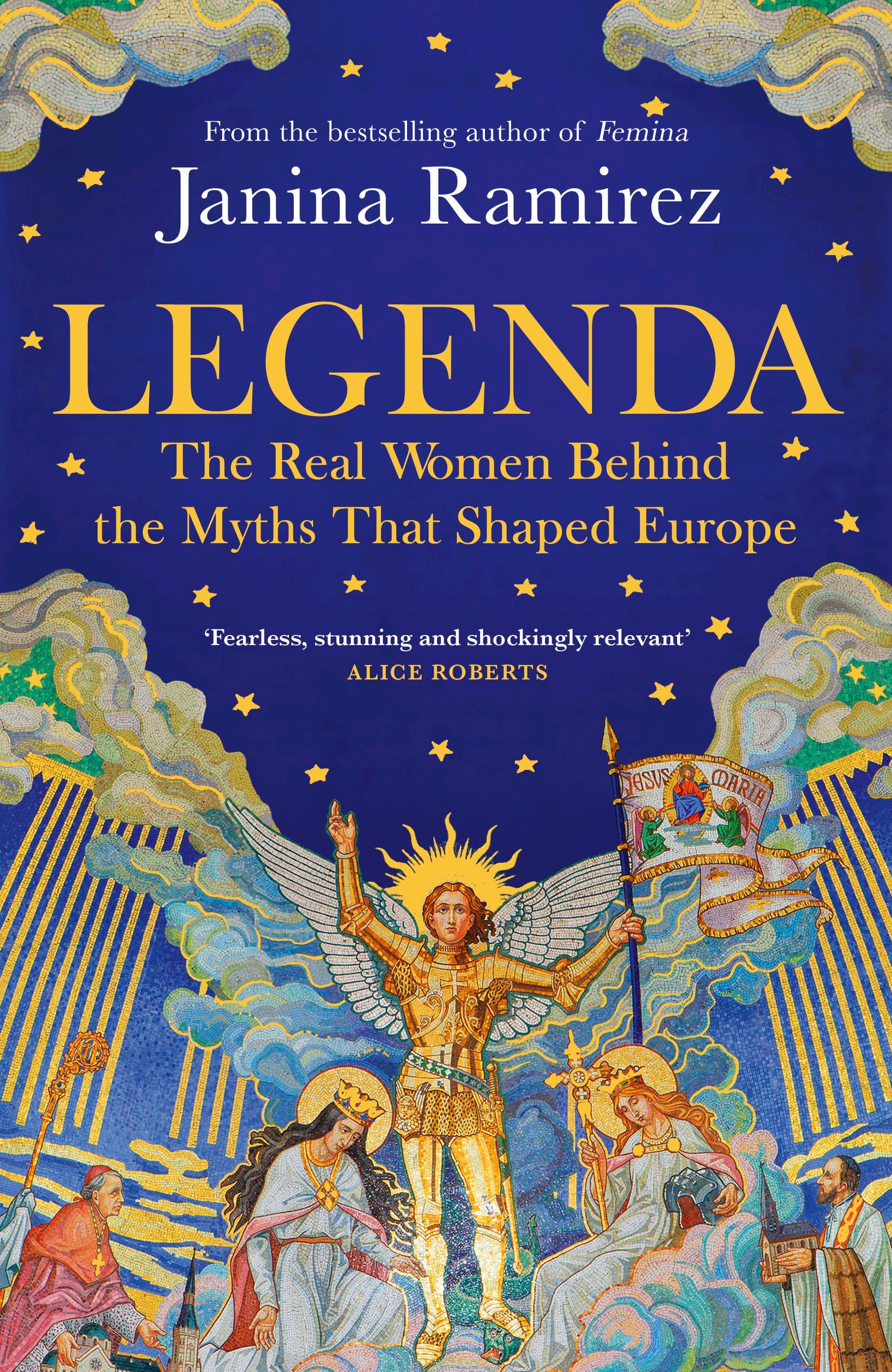

The detail of the banner is lost in the garish gilding of this nineteenth-century sculpture, commissioned after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1. The artist, Emmanuel Frémiet, who had previously sculpted Napoleon I on horseback, produced

this – the first equestrian statue of Joan – to inspire revanchism , revenge against Germany.2 It was erected on Paris’s boulevards to make a statement: Prussia may well have defeated Napoleon III, besieged the capital and claimed Alsace-Lorraine, but France will one day be whole again. Joan sits so bolt upright that she almost seems to lean backwards in the saddle, her face tilted defiantly upwards. The statue was modelled on Aimée Girod, a young woman from Domrémy, the village where the medieval heroine had grown up.

In the shadow of this modern rendering of a medieval woman, Jean-Marie Le Pen steps purposefully onto the blue-carpeted plinth surrounding the statue. Calls of ‘Jean-Marie’ ring through the small crowd as he begins his speech: ‘Since its inception the National Front has placed itself under the protection of Joan of Arc, the greatest person in history.’3 Pausing for each phrase, he continues:

Jeanne D’Arc by Emmanuel Frémiet, gilded bronze, 1874.

‘the system had put her in the broom closet, along with the Marseillaise [anthem], the tricolore flag, love of the homeland, the memory of the ancestors – in short, the history of France.’ He moves on to the subject of patriotism and nationalism:

Nationalism is love of the nation, and the nation is not about others, it is about ourselves. For some it is only a present and future, but for us it is also a past from which we come and without which we would not have existed biologically, physically, morally, spiritually.

As he descends into a tirade about how our current state of globalisation is bringing about a ‘weakening of character’ and neglect of ‘religious dogma’, something surprising happens. His microphone cuts out. He continues regardless, raising his voice, only snatches of his speech discernible as the crowd grows increasingly irate. His papers begin to blow off the lectern, while aides rush around and he calls out ‘sabotage!’ Finally the microphone begins working again. The rhetoric is even more vehement: ‘To those who proclaim themselves friends and supporters of migrant foreigners, I dedicate this response of Joan during her trial. When asked by the judges: “Do you like the English?” She replied: “Yes. At home.”’

This is a misquote.4 The exact section from Joan’s trial reads:

Bishop Cauchon: ‘Does God hate the English?’

Joan of Arc: ‘I know nothing about the love or hate that God has for the English, nor what he will do with their souls; but I know for certain they will be driven from France, except those who stay and die.’5

Joan was speaking during a time of war, when she herself had led armies into battle against English troops who, during the Hundred Years War, had repeatedly crossed the Channel, ravaged the many kingdoms of France and conquered the people through force,

Legenda

acting as oppressors from across the sea. Le Pen has manipulated the historical text, and Joan herself, to serve his own ends – to support his hatred of immigrants – and he gets a chuckle from the crowd, who assume he is employing history accurately. Le Pen continues with attacks on Muslim communities in France, who he states are destroying the nation. It is a speech inciting division, hatred and separatism. As he reaches his climax calling for ‘the suppression of the right of asylum, suppression of the right of soil, suppression of family reunification’, the wind picks up and silences him.

Introduction

This is not a traditional history book. It is a journey that I have curated, stretching across the centuries and across Europe. I began writing it with a simple premise: in recovering women’s stories from history I realised how certain individuals have had their names and reputations modified, manipulated, used and abused down the centuries, often for political ends. This set me thinking about the ways in which medieval figures like King Alfred, Charlemagne and Robin Hood have fed into historico-political narratives of national identity. ‘Legendary’ figures, romantic tales of old, or folkloric associations are not in themselves divisive. But when utilised by politicians, rolled out through schools and promoted through propaganda, it is important to challenge the foundations upon which these shared stories rest. To explore this idea further I wanted to put the frame on women – medieval and modern – and examine what roles they have played in the formation of nations.

Nostalgia, longing for a return to a country’s former glory days – the ‘good old days’, when things were better – is easily weaponised, with the past presented to us through rose-tinted spectacles as a time that politicians promise we can return to. The wave of isolationism currently sweeping the globe is fuelled by the belief that, in the face of rapid transformations in technology, global communication and increased integration, the answer is to go back to something earlier, something seemingly better. Nationalism, by nature of setting one group of people against those outside that group, feeds on nostalgia and weaponises it, harnessing it to notions of separatism, racism, elitism and misogyny. Today’s politicians belt out rallying cries to ‘Make Our Nation Great Again’,

promising a return to a shared ‘Golden Age’, while influencers rile up their millions of followers with inflammatory rhetoric about supposed ‘traitors’ versus ‘true patriots’. Eric Hobsbawm, a British and Jewish historian of Polish-Austrian descent, who grew up first in Egypt and then in Germany at the start of the Second World War, has these words of caution: ‘Historians are to nationalism what poppy growers … are to heroin addicts: we supply the essential raw material for the market.’1 Paying attention to how politicians, religious leaders and ideologues use the past – how they craft their rhetoric, co-opt history and instil a fear of change – is, I feel, a present and urgent imperative. Should we not take a moment to look backwards and challenge the premises upon which our modern nations were built?

To better understand how the Europe of today emerged I have chosen seven countries or regions, starting with France, then the Iberian Peninsula, before moving to Greece, the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and finally Britain. In each case I have paired and contrasted a modern figure from the eighteenth or nineteenth century, active during a pivotal moment of revolution or nationbuilding, with a medieval woman. Together they comprise an exceptional cast: queens, warriors, empresses, saints. Rather than the fragmentary pieces of lives, archaeological finds and fleeting references that informed my previous book, Femina, I have taken a different approach here. I’m re-examining top-down narratives, well-known stories and legends that appear perennial, yet are rarely given the careful attention they deserve. What are the roots of their stories, and how can we find the individuals behind the famous names? I look for the historical women in the streets they walked, the buildings they inhabited, the objects they handled and the texts their stories are preserved in. By examining the women behind the legends, new windows open on to the social, political, religious and economic realities they were a part of, and I trace how these figures have been reinvented century after century to serve the needs and agendas of different generations.

As a historian I do not just deal with the past but also try to understand how humanity can come together peacefully to build

inclusive societies that value equality, in hope of a better future. I feel compelled to do my part in resisting the twisting of history for violent ends, something that lies at the very heart of nationalism and extremism. We are going to take this journey together. At some points the route will be quick and straightforward, the roads clear and the connections simple. At others, we will veer off into unfamiliar territories and new landscapes. But travelling is as important as reaching a destination. I have tried to carefully craft a journey across Europe, moving between eighteenth- and nineteenthcentury women acting with courage or impunity at historic moments, back to medieval individuals who have become icons underpinning a nation’s sense of its shared history. This is not simply a route from A to B, but as we travel together I hope that rediscovering these legendary women will whet your appetite to explore further, follow your own paths less trodden and find new ways of connecting with historical people, places and events.

The people of the past were us – just earlier. They shared our basic needs as well as our desire for security, love and purpose. Stepping into their worlds allows us to understand the similarities and differences that exist between all humans across time and space. Yet the periods and places these women transport us to have their own unique characteristics: from food to fashion, love to language, belief to buildings. How they presented themselves, how they spoke, their dreams, passions, interests – these elements are often beyond recovery. But these exceptional individuals only make sense alongside a cast of other people and within their specific historical contexts. To find them we must use all the evidence available to reconstruct their worlds as accurately as possible.

Rather than simply consume a version of their legendary story, which has been sieved through centuries of rewrites, it is the job of the historian to probe backwards through time, and to use everything from excavated finds, aged manuscripts, contemporary comments and early images in search of facts. The records are limited and often the further back in time you search, the more fragmentary the material. We can only get so close to the people of the past, but in searching for them we can uncover numerous

stories, most of which are far more fascinating than the fairytales and nursery rhymes passed down as legend. Reconnecting with a historic individual can spark enthusiasm and a curiosity to understand how varied, surprising and exciting this world is, and always has been. As travel broadens the mind, so I ask you to join me on this journey, unravelling history from legend in search of the remarkable women who played a part in building our modern European nations.

The Nation Is a Woman

A stroll through the capital cities and power hubs of Europe, forged in the white heat of revolution and modernisation, gives the impression that women played no part whatsoever in the founding of nations. Both Haussmann’s Paris and the corridors of the Houses of Parliament in London spill over with statues of great men. The Vatican puts these male decision-makers in clerical gowns, with power over not just earthly matters, but spiritual ones too. When women do feature they are ciphers, symbols of what a nation believes are its greatest strengths.2

Marianne is the conflation of different concepts – the ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ of the French Revolution, combined with reason and justice.3 Lady Liberty in America wears the Phrygian Cap of freed Roman slaves, to show that the people would not be oppressed and would govern themselves. Other countries’ female anthropomorphised national symbols are loosely based on those that emerged from ancient Rome: Germania bears the sword and armour of a nation that would not be conquered; Hispania wears a laurel wreath and is accompanied by a lion, representing the Kingdom of Castile; Britannia wears the Corinthian helmet and wields a trident to symbolise control of the seas.4 These female personifications were designed to represent a whole unified people in one female form – sometimes with a degree of historical context, other times simply as an instantly recognisable icon. They are all mothers, daughters, sisters, lovers; they birth the nation and

suffer for it. But they are not real. They are abstract concepts, depicted in art and sculpture as megalithic emblems. Their faces are passive and detached, eternal and anonymous. In fact, the ideals that they are used to represent – justice, liberty, nationhood – were all kept at arm’s length from most women in the modern period; men were judges, soldiers, philosophers, architects, politicians. Women were not.5 The nation is a woman; but women did not build nations. That was men’s work – apparently.

If real women did come to the fore in moments of national reinvention, they were often seen as problematic. Revolutionaries were whispered about, women writers were imprisoned or silenced, activists were punished or killed. Of course, men were still happy to use certain women in their nation-building projects. As Romantic idealists and power-hungry megalomaniacs across the globe put their heads together around maps and drew the outlines of countries, these men knew that developing a feeling of belonging to a specific country was about more than geographical boundaries. To die for their nation, soldiers needed a reason to feel united under a flag, bound to one another as opposed to those they fought against. So nationalistic writers penned epics and romances celebrating the glorious past, scholars and linguists analysed languages and archives to discover the roots of the common tongues or glorious deeds from history, and politicians and teachers spread messages of unity, enforcing the idea that the nation has been and always shall be.

Inspiring people to feel bound together as one entity requires a unifying cause. What better cause than to make the nation a mother – a beloved motherland? The chivalric tradition lives on as men become inspired by these women of the nation, and by the women of the past, to pursue their just cause. And so we find medieval women shackled to national histories throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a fraction of whom I am spotlighting in this book. Joan of Arc, for instance, was co-opted in the wake of the Revolution, used and abused by different factions, her identity transmogrified depending on what use France could make of her. Lady Godiva was transformed from

influential ruler and landowner to a titillating nude on horseback, propping up Victorian ideals of womanhood. Catherine of Siena’s outspokenness, eccentric behaviour and diplomatic influence were erased in favour of a saintly servant of the Vatican. Again, Hobsbawm has words of caution: ‘Getting history wrong is an essential part of being a nation … it is the profession of historians to dismantle such mythologies.’6

With medieval women as our guides, the modern histories of nations appear in all their messy complexity. Through these remarkable individuals we can find both the elements of a nation’s past that need reassessment, and those that can offer inspiration going forward.

Did Nations Exist in the Medieval Period?

When does the medieval period end and the modern begin? While historians pin dates onto periods, the characteristics that come to define separate epochs can be fluid in either direction, with innovators and traditionalists pushing and pulling in the face of change.7 There is also huge variety globally, with transformations taking place in different geographical regions, sometimes centuries apart.8 The dates most commonly defined as ‘medieval’ across Europe start with the collapse of the Roman Empire around ad 500 and end around ad 1500.9 This millennium of human history, spanning tens of thousands of miles, from the tip of Scandinavia in the Artic Circle to the toe of Italy’s boot, and innumerable innovations, has been reduced to a ‘middle age’, but it has infinitely varied manifestations across time and space. Often reduced to a ‘dark age’ between the brilliance of classical antiquity and the birth of the modern age with the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, the medieval period is commonly presented as a time of ignorance, war, plague and superstition.10 But the women in this book challenge that notion, revealing instead a time that was ever-changing and complex.

The tools utilised by nation-builders since the eighteenth century to promote feelings of unity and common identity include language,

religion, traditions, landscape, rituals, flags, costumes, names, anthems, colours, animals and symbols.11 Some of these are certainly in evidence in the medieval period, while others appear in embryonic form. Medieval people were united by factors, particularly kinship and religion. But the terms used to describe communities of individuals were vast and varied – kingdoms, fiefdoms, communes, states, principalities, leagues. The modern terms ‘country’ or ‘nation’, by which so many of us still define ourselves, would not have made sense to a medieval person.12 Theirs was a world of variety, fluidity, moving borders and changing circumstances.

An important characteristic of modern nations are their defined geographical borders, drawn from an aerial perspective on detailed maps. Medieval maps were embryonic, and those that do survive, like the Hereford Mappa Mundi made around 1300, were religious rather than practical artefacts.13 While it is possible to make out the separate continents – Europe to the left, Asia at the top and Africa to the right – and while certain rivers, islands and coastlines are shown with a degree of accuracy, this map was intended as a work

The Mappa Mundi, the largest medieval map still known to exist, drawn on a single sheet of vellum, c. 1300, housed in Hereford Cathedral.

of religious art rather than a tool for navigation. It is very large at 1.58 by 1.33 metres and was originally hung at the centre of a triptych, with images of the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary on either side.14 Designed as a discussion piece, and an object to support the local cult of Thomas de Cantilupe, Hereford’s bishop, it includes texts and images that were meant to be closely scrutinised for their symbolic meaning, rather than for delineating countries.15

The Hereford Mappa Mundi is a spiritual map, since it shows Paradise at the top, the path to salvation and Jerusalem with Christ’s crucifixion at its centre.16 Modern geographers have seen in this and other medieval maps ignorance of the physical world, and have suggested that they endorse medieval scientific misunderstandings, such as that the earth is flat. But this is to entirely misunderstand their function.17 Instead, these maps conflate time and space, with historical events layered upon geographical areas. In this respect they reflect Christian attitudes of the time, where individuals lived their present existence, while simultaneously stretching back through time and across the known world to the biblical sites and events that still provided the rhythms of their daily lives.18

These maps also reveal how closely woven together the medieval world actually was. The Church’s influence spread both to the West and to the East, and across the continents, providing a web of interconnections for travellers. A pilgrim like Margery Kempe (c. 1373–1438) could walk from King’s Lynn to the Holy Land, along a system of well-established routes, punctuated regularly by monasteries where Latin was the common language and the routines of Christian life remained similar despite travelling thousands of miles. 19 There would, of course, have been cultural differences depending on the region, with pilgrims reporting the changes in climate, landscape, dress, language and cuisine at different locations, but there was still an overriding sense of lands being linked by the Church. Christianity ‘smoothed down regional discrepancies’, creating a common thread across Europe.20

In the spiritual realm, fealty was due to religious representatives – a network of priests, bishops and archbishops, spread across diocesan and episcopal lines. In the secular world it was due to the

ruler of the land. Fealty could mean many things: military service, taxes, legal dues, economic support. But the basic mode of exchange was land and produce for labour or services.21 Debates between medievalists continue as to whether the term ‘feudal system’ is appropriate, but across medieval Europe systems were in place that bound the knightly class to their rulers, and in turn to those that worked on their land. 22 At the highest levels were networks of nobles tied to individuals who may have styled themselves as kings, queens, lords, ladies, emperors or empresses. But for the majority of medieval people, the links did not reach very high. A peasant may have seen their lord occasionally when submitting their taxes or asking for justice, but rulers of regions and realms were not of great interest to those at the lowest rung of the social and economic ladder unless there was a war looming, or they were on progress to take wealth and livestock through local towns and villages. Whether working in a field in modern-day Poland, Ireland or Spain, most people would have had very little notion of what ‘country’ they were part of.23

Coins would have distributed regal images, and sculptures or paintings of rulers may have appeared in the local church or manor, but the affairs of courts were not the primary concern outside centres of power.24 Loyalty was a local business, and communities would bind themselves together according to kin, dialect, traditions and shared memories, rather than to the concept of a country or nation.25 Sometimes, however, vast empires, like that ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor Barbarossa (1122–90), did play upon ideas of specific cultural identities to stress the extent of their control. Much like the Roman Empire brought those it conquered under the banner of Rome, so Barbarossa was intent on reflecting how his empire united different groups of people under one shared cause. But the concept of an empire is different to that of a nation, since the term assumes distinct peoples subsumed under a single ruler.26

Language was also far from straightforward in the medieval period. With Latin used by the Church in the West, and Greek employed in the East, international communication did not depend on learning different tongues for travel and correspondence. The

Legenda

vernacular languages spoken in particular communities may have been related, but there was huge regional variety. Today established versions of languages have been pinned down in dictionaries, with Samuel Johnson triggering an inter national flurry of standardisation with his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language.While there is still some variation and local accents are distinctive across a country, in the medieval period different dialects could be virtually incomprehensible from one community to the next.27 William Caxton, the man who introduced England’s first printing press in 1476, writes about this problem:

English that is spoken in one shire varyeth from another. Insomuch that in my days [it] happened that certain merchants were in a ship in [the] Thames … One of them named Sheffield, a mercer, came into a house and asked for meat, and specifically he asked after ‘egges’, and the good wife answered that she could speak no French. And the merchant was angry, for he also could speak no French, but would have had egges, and she understood him not. And then at last another said that he would have ‘eyren’; then the good wife said that she understood him well. Lo! What should a man in these days now write, ‘egges’ or ‘eyren’?28

The woman was from one side of the river Thames in Kent, while the merchant was from the other side in London. Yet the two had mutually incomprehensible words for such a simple thing as an ‘egg’. This indicates quite how disconnected people could be linguistically from one another throughout the medieval period.

Elizabeth of Thuringia

The life and legacy of one medieval woman exemplifies how fluid and complex national identity was during the medieval period. Most commonly known as Elizabeth of Thuringia, she was a princess and noblewoman who lived from 1207 to 1231. She was

married at 14 to Louis IV of Thuringia, who held the position of landgrave, which was a rank of nobility within the Holy Roman Empire somewhere between a duke and a count. 29 While her husband supported the emperor, Frederick II, Elizabeth ruled over their kingdom during a period of famine and flood, giving away food and even her state gowns to assist the poor. It was at this time that ‘the miracle of the roses’ was said to have occurred. Elizabeth was taking offerings to the people when she ran into her husband’s hunting party. As rumours were circulating that Elizabeth had been removing treasures from the castle to feed the poor, Louis wanted to prove her innocence in front of his guests, so asked her to open her cloak and reveal anything hidden underneath it. As she pulled back her garment, a vision of red and white roses appeared, proving her sanctity.

Louis then died when Elizabeth was just 20 years old and she was dragged into a game of thrones. Her uncle, wanting her to remarry, imprisoned her. But she had made a vow of chastity and said she would cut her own nose off to make her unattractive to suitors. When she was finally released and had her dowry returned, she used this to found a hospital where she tended to the sick. Her life was dogged with hardship, as her spiritual adviser, Konrad von Marburg, made her lead a very strict existence and beat her. Whether subjected to husband, uncle or adviser, Elizabeth still managed to perform good deeds, which meant she was declared a saint upon her death. So what is it that makes her a noteworthy example of the fluidity and complexity of the medieval period?

The kingdom she is named after – Thuringia – is now a state in central Germany, with its capital city Erfurt sitting roughly equidistant from Dresden, Frankfurt and Nuremberg. Elizabeth’s mother Gertrude was from the Duchy of Merania, which was most probably on the coast of Croatia. One of Gertrude’s sisters married the king of France, while the other married the king of Poland. Elizabeth’s father Andrew was king of Hungary and ruler of the Principality of Halych, which was in Kievan Rus. According to one tradition, Elizabeth was born in Sárospatak, now in northern Hungary, but according to another she was

Reliquary containing the skull of Elizabeth of Thuringia. The oldest part is an agate bowl made sometime between the fourth and seventh centuries. Other parts were made during the eleventh century, and the base dates from the thirteenth century.

born in Pozsony, which is now Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia. She died in Marburg, which was then part of the Holy Roman Empire, and is now in the state of Hesse in Germany. Her tomb became a centre of pilgrimage particularly through her connection with the Third Order of the Franciscans. Although it’s uncertain if she joined the Order, she was sent a personal blessing from Saint Francis just before his death in 1226, so she is venerated in Italy and across the globe.30

Elizabeth’s shrine in Marburg became one of the main German centres of pilgrimage during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and when her saintly draw waned, she continued to be celebrated as a founder of many great European aristocratic families through her daughter Sophie, who married the Duke of

Brabant. Three centuries after her death, her skull, contained in a crowned agate chalice, was stolen from her shrine by German Protestant reformer Philip I of Hesse, who was intent on erasing her saintly remains, only to be returned by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.31 The bejewelled chalice was taken as loot by the Swedish Army during the Thirty Years War (1618–48) and is now in the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm, while her other bones ended up in Vienna. Other relics travelled to Brussels, the north of France and as far as Bogotá. Elizabeth has continued to inspire veneration, with the octocentenary of her birth in 2007 celebrated worldwide. She has been fought over and adopted by Germany, Hungary, Czechia, Slovenia, Austria, Slovakia and Croatia. There are monastic sites, churches and establishments across the world where she is celebrated. But it is impossible to say for certain where she is from. Whose saint is she?

If Elizabeth was asked where she was from, what would she say? She would probably give the names of her parents and her husband, tying herself back through family links to specific dynasties or ruling houses. She might give the name of the church she was baptised in, or that of her religious adviser, or the priest whose masses she attended, rooting her within a localised spiritual community. She may describe her land and estates, or the hospital she founded, placing her within a specific site and environment. But she would not name a country or a nation. She would know that she was bound through bonds of loyalty, commitment and legacy to numerous groups and individuals around her. Her communities defined who she was, not an overarching concept of a nation.

The women in this book, like Elizabeth, did not exist in a vacuum. They were part of complicated societies, they adapted to changes around them, and reflected the modulations of their time. To declare them the embodiments of nations or timeless heroines, as nation-builders did, is to transform them from identifiable people of the past into poster girls and propaganda tools. It is time to pull back the layers and see them in all their complexity. It is time to discover the real women behind the legends.

1

France: Revolution and Reinvention

13 July 1793, Hotel de Providence, Rue des Vieux Augustins, Paris

Passing through the hotel lobby, heart in her mouth, 24-year-old Charlotte Corday places the keys on the marble counter. Over the last four days she has been preparing. The letters are sealed and tucked into her pockets. She has misdirected her father, lying that she left her home in Caen for England.1 That should keep him off her trail. But now the day has finally arrived and she is reluctant to begin this doomed journey across Paris. It is blisteringly hot as she steps outside and passes down Rue des Vieux Augustins towards the recently ransacked Tuileries Palace. She sees people outside cafes sipping on cool lemonade and glasses of beer, tricolore cockades pinned on ladies’ hats, and red, white and blue flags draped from windows.2

Looking up at the palace’s facade, the visible bullet holes stoke Charlotte’s rage. It was here on 10 August the previous year that the Revolution really began, with thousands of angry Parisians storming the royal palace and forcing the imprisonment of King Louis and Queen Marie Antoinette.3 The king was led to the guillotine months later at Place de la Revolution, just beyond the Tuileries Gardens. These events, and the September Massacres, during which some 1,500 people were executed in the space of just four days, have driven Charlotte to Paris on this day. She is a moderate revolutionary. She detests the waves of violence and death surging through France.

But she is in no hurry, wandering around the royal palace numerous times and stopping at a store along the way to change her white bonnet for a black one with green ribbons. There is another purchase she needs to complete before she arrives at 30 Rue des Cordeliers.4 Slipping into a cutler’s shop she chooses a kitchen knife with a 6-inch blade. Outside she ducks into the shadows for a moment, sliding the knife into her corset to conceal it from view. Taking a carriage from Place des Victoires she passes over the Seine, keeping the Île de la Cité and the spires of Notre Dame to her left. Her destination is in the heart of the affluent 6th Arrondissement of Paris: the home of intellectuals and the liberal elite. Winding through the streets, her stage is set.

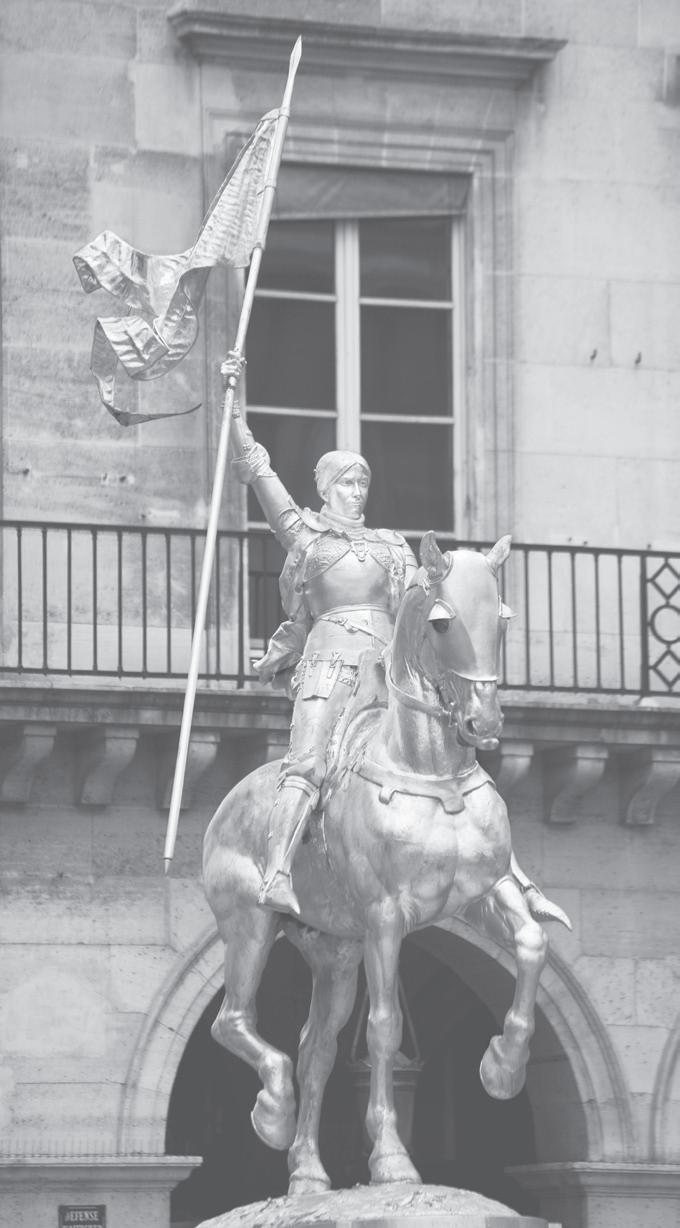

As the sun reaches its peak in the sky, Charlotte raps on the door to Jean-Paul Marat’s home.5 The writer, scientist and journalist, turned radical politician and supporter of the left-leaning La Montagne group, has dominated media attention since the Revolution began, with his periodical, L’Ami du Peuple, the most critical dissenting voice against the new leaders of France. In the entrance to Marat’s house stands his sister-in-law, Catherine Evrard, who casts suspicious eyes over the unknown woman. Visitors to the house are frequent now that Marat has stopped attending the National Convention (the assembly governing France at this point) but they are usually spies and informants. Marat greets guests from his bathtub as his skin condition has deteriorated and the only relief he can get from the pain is by lying in medicated water.6 Despite his worsening health, the controversial political player still wants a part of the action. So from his makeshift desk – a wooden board balanced across the tub – he edits his journal and greets visitors in hope of information from the tumultuous streets of revolutionary Paris.

Charlotte urges Catherine to let her in, pretending that she has information about a potential uprising by the Girondins – the largest political threat to Marat’s La Montagne.7 But Catherine bars her from entering, so Charlotte walks away, despondent. Stymied at her first attempt, she goes back to her rooms where she pens a quick letter imploring Marat to see her, before returning

again to his house in the evening. Timing her approach to coincide with a delivery of bread, she sneaks into the house, climbing the stairs towards Marat’s bathroom. His wife Simonné stops her midway up, and like her sister is instantly suspicious. But Marat hears the women talking on the stairs and Charlotte’s plea that she ‘has information’. Curious, he shouts down to his wife to let Charlotte into the bathroom.

There he lies reclining on fabrics, hair wrapped in a white turban, skin enflamed and sore. Charlotte sits alongside the tub while Simonné hovers in the doorway. Marat begins scribbling the names of Charlotte’s so-called counter-revolutionaries onto a scrap of paper. Reaching the end of the list he reveals his notorious passion for violence, declaring, ‘I will soon have them all guillotined in Paris.’8 He asks Simonné to fetch some more medicine for the water. As soon as she passes down the stairs, Charlotte stands up, draws the knife from her corset, and plunges it into Marat’s chest. One quick, targeted strike, and her blade pierces the skin, sliding under the right clavicle, severing a major artery. Marat has seconds to cry out ‘help me my love’, and then collapses backwards, his bathwater pooling with blood. The papers in front of him are witness to the gruesome manner of his death, the lower halves soaking up the tinted bathwater.

Charlotte doesn’t run or resist as Simonné and one of Marat’s colleagues storm into the room. His wife shouts ‘What have you done?’ and the angered friend throws a chair at Charlotte before pinning her to the ground. She is still passive when taken before the local commissaire de police. Charlotte claims she was driven to murder because she feared civil war was imminent, fuelled by Marat’s unrelentingly divisive articles and incitements to violence in his radical revolutionary paper.9 She was prepared to sacrifice her life for her country. She insists the idea was hers alone – something that riles the officials. They can’t believe that a woman could act independently and choose to murder. There must be a man behind this plan.

Charlotte is taken to the notorious Conciergerie prison and cross-examined three times, as inquisitors desperately attempt to find the male mastermind behind the assassination. Again and again,

blood-stained copy

L’Ami

Charlotte reiterates that she acted alone. A woman can be a violent patriot and die for her country. During one trial she claims, ‘I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand.’ French journalists write disgusted articles about her lifestyle and appearance, her advanced education being of particular concern: ‘This woman absolutely threw herself outside of her sex.’10 Found guilty, she is sentenced to execution four days after the murder. The scene of her execution is described as ‘magnificently awful’, and ‘the place thronged with multitudes’.11 Wearing the red shirt given to those deemed criminals against representatives of the people, she is soaked to the skin by a summer downpour as she climbs the scaffold to her death.

After the ‘National Razor’ slices through Charlotte’s neck, one of the carpenters who had been working on the guillotine does something shocking. Picking up her decapitated head from the blood-soaked boards, he slaps her around the cheeks. Alarmed news reports claim Charlotte’s head ‘blushed’ at this indignity.12 It

A

of

du Peuple, which Marat was marking up with notes when he was stabbed in the bath.

is a step too far for the crowd, who descend on the disgraced man, dragging him away where he will be imprisoned. There is an irony here – a woman could be executed for having committed a violent murder and behaving in a ‘masculine fashion’, but disrespecting a woman by slapping her after death was deemed unacceptable. In a further troubling act, Charlotte’s body is taken for examination by doctors, to determine whether she was a virgin.13 This intrusive defilement of her body was supposed to prove she was engaged in a sexual liaison and under the thrall of a male accomplice who still needed to be weeded out. But the doctors reluctantly declared her ‘intact’. In life and in death Charlotte had become a cypher for the complicated position of women in revolutionary France.

The new Republic was segregated – the divide between men and women was clear. Far from bringing liberty and equality to all, it was the third aspect, fraternity, brotherhood, that prevailed. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted a month after the storming of the Bastille, concerned itself with men and ‘active citizens’. The poor, the enslaved, foreigners and women – ‘passive citizens’ – were excluded from the suffrage. This despite the fact that women had arguably launched the Revolution. On 5 October 1789, up to 2,000 women had rushed inside the Hôtel de Ville, seized weapons and then led an ever-growing crowd to Versailles. Here they had taken over the Estates General assembly convened there and laid siege to the palace, eventually forcing the king to process in shame to Paris.14 As revolutionary historian Jules Michelet put it: ‘The men took the Bastille and the women took the King.’15

Following these events, in 1791 Olympe de Gouges penned her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen – a direct response to the earlier ‘Declaration’ – which exposed the failures of the Revolution in relation to women. She was convicted of treason and executed.16 Women did see some improvements in their lot, which correlated with the reduction of the Church’s authority. They were granted civil rights and a legal identity of their own. A husband was no longer allowed to lock up his wife

and children, and male–female relationships changed with the establishment of civil marriages, rather than religious ones, which could be dissolved and allowed women the opportunity to divorce. But ultimately the Revolution did little to improve women’s position within society: ‘The makers of the French Revolution were determined, not to increase the influence of women in their government and society, but to destroy it.’17

Charlotte Corday’s murder of Marat triggered a further problematic period for women in France. It wasn’t simply the case that male decision-makers were determined to keep the gender divide in place. Women turned against other women, too, especially if they were perceived, like Charlotte Corday, to have damaged perceptions of what a woman should be: namely, a devoted mother and wife dedicated to the domestic sphere. Just months after Marat’s murder, for instance, on 29 October 1793, a group of women appeared at the National Convention to denounce another group of more militant women for threatening them if they didn’t wear the red cap of liberty.18 It provoked a debate about the two sexes and their roles in politics. Jean-Baptiste-André Amar, a prominent member of La Montagne, made this famous declaration that same day:

Man is strong, robust, born with a great energy, audacity and courage … He alone appears suited for the profound and serious cogitations that require a great exertion of mind and long studies that women are not given to following … Do you want to see them coming up to the bar, to the speaker’s box, to political assemblies like men, abandoning both the discretion that is the source of all the virtues of this sex and the care of their family?19

This debate, just three months after Charlotte’s execution, led the Jacobins – the leading political group through the Reign of Terror, during which up to 40,000 people were assassinated between September 1793 and July 1794 – to declare all women’s clubs illegal, removing the last spaces where women could have their voices heard with regards to politics and social reform. By killing Marat,

Charlotte had inadvertently pushed back women’s rights. By killing Marat, Charlotte had created a martyr.20 Before his murder, Marat’s declining health and his possible incitement of the September Massacres, which many including Charlotte held him directly responsible for, had a negative impact on his reputation. He had been imprisoned and had left the National Convention. He was persona non grata, his letters ignored and his party trying to distance themselves from him. But his murder wiped the slate clean. He was the Revolution’s sacrificial hero.21

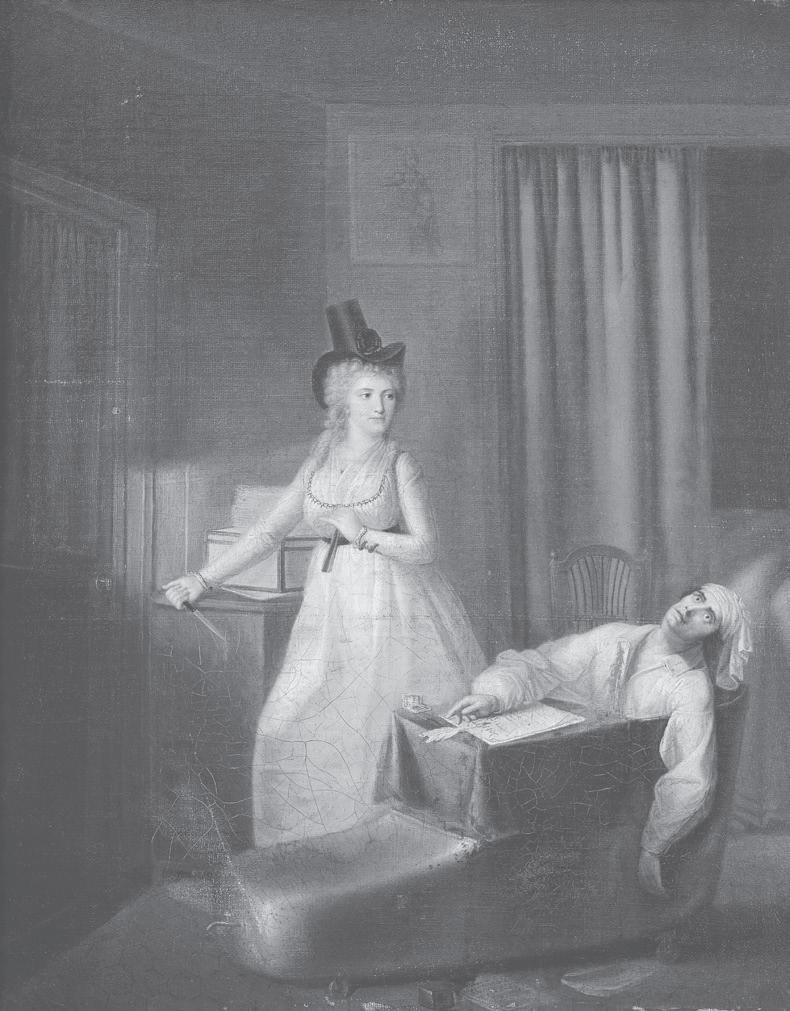

Charlotte knew the power of public perception and in her final days tried to take some control of her reputation.22 While awaiting execution she requested that a painter be brought to capture her likeness. In a surprising act of conciliation towards the imprisoned Corday, Jean-Jacques Hauer, a German artist and member of the National Guard, was summoned to her pitiful cell in the Conciergerie.23 The resulting painting is simple, but important. At a time when caricatures and cartoons spread an exaggerated image of the

Jean-Jacques Hauer, Charlotte Corday, oil on canvas, c. 1793, from a sketch made before her execution.

female murderer, Charlotte wanted one last chance to have a real rendering to counter-balance the stream of media representations. She even reputedly suggested some changes to ensure it was more life-like, ‘more real’.24

Her hair has a sheen of lightness, possibly due to having put on powder to tidy up her appearance before having her portrait taken. The symbolism of ‘blonding’ her hair was important. She represented the upper classes, who were criticised for taking precious wheat that could have been used to feed the poor, and pouring flour over increasingly extravagant piled hair pieces instead. Charlotte’s passport lists her as ‘chestnut brown’,25 but by showing her hair powdered Hauer is emphasising her aristocratic roots. However, because he seemingly sympathised with her, the light hair may also have been intended to suggest a degree of purity and innocence.26 Hair, its length, colour and styling, are very telling in terms of how women from history are represented. Charlotte requested this portrait because it was the last moment she could exert some control over her image, her narrative and her legacy.

Gossip-hungry Parisians had been greedily devouring information about Marat’s infamous murder, so Hauer used Charlotte’s portrait to create a rushed painting for the 1793 Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Charlotte is depicted as beautiful and determined in her moment of triumph alongside an unflattering boggle-eyed Marat.

Marat’s huge, dramatic state funeral was attended by the entire National Convention, and women were anxious to participate in the procession, with one group volunteering to carry the bathtub in which he died. The spectacle was co-ordinated by JacquesLouis David, France’s pre-eminent painter and member of the Committee of General Security, which acted as a police agency during the Revolution. Immediately he set about sanctifying the assassinated revolutionary. 27 David wanted to counter Hauer’s visual rendering of the event, so took Charlotte out of the picture.28 His famous painting The Death of Marat is an intensely intimate portrayal of the scene, with the tight framing and foregrounding of the limp arm drawing the viewer into the room to gaze on the

Jean-Jacques Hauer, The Death of Marat oil on canvas, 1973.

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat oil on canvas, 1793.

pale body and the shocking drops of bright red blood. The female assassin is completely erased.

As an artist of the Revolution, David openly rejected the imagery and symbolism of the Catholic Church, but here he could not avoid echoing religious representations of Christ. The position of Marat’s head mirrors Michelangelo’s Pietà, with the Virgin Mary cradling the body of her dead son on her lap. The obvious wound, open and bleeding, recalls that made in Christ’s side on the cross, but also the representations of saints like Sebastian, pierced through by arrows. As martyrs in religious paintings would be bathed in the soft light of salvation, so David has presented Marat as a martyr for French liberties, with a luminous glow radiating across the corpse. Through his artistic work and involvement with the National Convention, David toed the revolutionary line and outwardly rejected France’s Catholic past. But in building the imagery of the Republic, the echoes of France’s history and its religious heritage find a way to permeate through to the new national consciousness.

As well as trying to control her image, Charlotte also knew the power of her actions. When she first left her home in Caen for Paris she took with her a copy of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, written by the Greco-Roman philosopher in the second century ad. Among the 48 men whose lives and achievements Plutarch painstakingly lists is Brutus, one of Julius Caesar’s assassins. In Plutarch’s text, Brutus is quoted as saying only one man – Julius Caesar – had to die to save the Republic: ‘It had been firmly decided not to kill anyone else, but to summon all to the enjoyment of liberty.’29 Charlotte felt that she was acting like Brutus. She had to put her knife into one man to help build a nation. A daughter of nobility who received a brilliant education, she was a student of classical civilisation – a world where men made history.

During her trial she constantly reiterated that she acted alone and was proud to be a woman able to use righteous violence. However, her thoughts, speech and actions are all framed within a world view formed in antiquity – the emperors, soldiers and writers of Greece and Rome whom ‘enlightened’ members

of her class read about, copied and celebrated. In the classical world, men made history. In the Enlightenment period of the eighteenth century, men made history. Charlotte’s behaviour set her outside of this system. Women could not be violent patriots in ancient Rome or in modern France. But there was one medieval woman whom Charlotte was immediately compared to – Joan of Arc.30

Although separated by three centuries, Charlotte and Joan shared a religious fervour. Charlotte was educated at the Abbaye aux Dames convent in Caen, where William the Conqueror’s wife, Matilda, is buried. She became an influential member of the community, acting as secretary to the last abbess. It was in the extensive library there, named after the Norman queen, that Charlotte soaked up ideas, both medieval and Enlightenment. She never lost her passion for religion. When Charlotte’s room was searched after the murder, investigators found her Bible open and underlined on the page was the description of Judith slaying Holofernes. This famous story follows Judith, a beautiful Jewish widow who murdered one man to save her people. Seductively entering the tent of Holofernes, the Assyrian general, she beheaded him after he passed out, drunk.31 In a letter from prison, Charlotte suggests she, like Joan, won battles to bring about peace for the nation: ‘I flatter myself I have gained more than one battle, by facilitating the establishment of tranquillity.’ 32 On the scaffold of her execution, she declared to a priest: ‘The blood which I have spilt and my own, which I am about to shed, are the only sacrifices I can offer the eternal.’33

Marat’s siblings declared their brother ‘was assassinated by a scoundrel wearing women’s clothing’.34 Dressing in male clothing was the crime levelled against Joan at her trial, so the blurring of gender boundaries also links the two. The parallels between Charlotte and Joan were drawn out extensively by artists and writers on the other side of the Channel, where Corday was viewed as a heroine. Her actions were universally admired in the English press, and particularly by the Romantic poet Robert Southey. At the exact time Corday’s trial was being reported in the London Times

Legenda

and her ‘Amazonian courage’ praised, Southey was beginning his epic poem on Joan of Arc.35 He draws a direct comparison between Joan and Charlotte:

No Maid of Arc had snatch’d from coward man

The heaven-blest sword of Liberty …

No Corde’s [sic] angel and avenging arm

Had sanctified again the murderer’s name.36

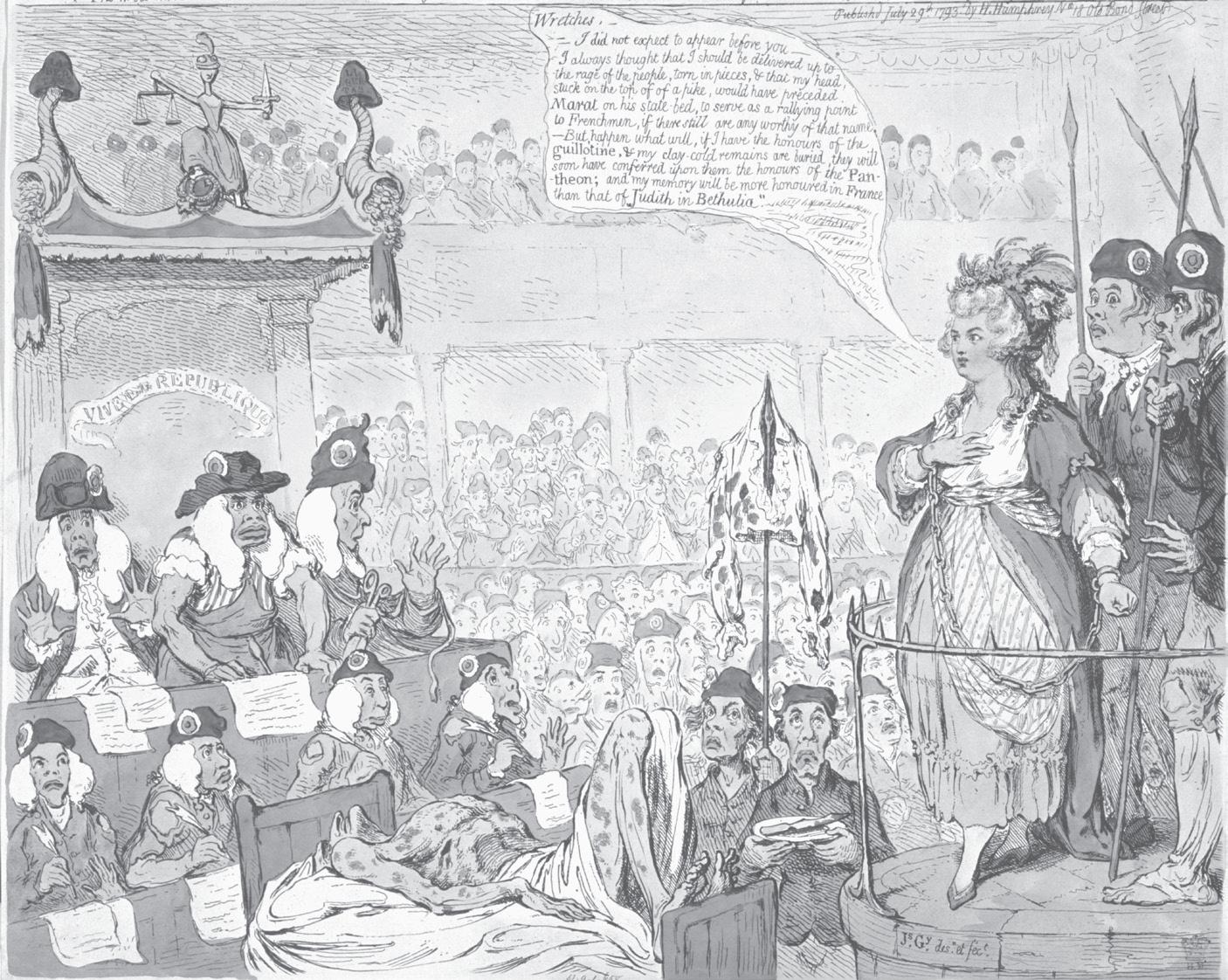

As Charlotte had anticipated, it wasn’t just her name that spread widely in the press and in print, but also her image. English cartoonists were fascinated by her, presenting the assassination of Marat as a valiant deed. The French Revolution terrified many in England, with reports of the staggering numbers of deaths during the September Massacres, and the execution of aristocrats, Church representatives and the royal family reported upon every day by the London Times.

James Gillray, The Heroic Charlotte la Cordé, 1793.

The English cartoonist James Gillray produced a version of Charlotte’s trial. It shows the members of the Revolutionary Tribunal, responsible for trying political criminals, caricatured with Gillray’s usual distain for the shabby and chaotic appearance of the Republicans. Charlotte stands above them in noble dress, her face beautiful and her hair blonde, powdered, carefully piled on her head beneath a garland of feathers. Gillray has upped the drama of the trial by anachronistically positioning Marat’s gruesome and marked body in front of Charlotte. In the inscription Gillray refers to his leprosy. Marat was more likely suffering from a fungal infection known as seborrhoeic dermatitis, but the suggestion that this ‘heroic’ woman has ‘rid the world of this monster’, afflicted with leprosy as a just ‘punishment for his crimes’, adds a grandeur to her actions.37

At just 24 years old, the young Charlotte was an effective rallying point for other satirists like Isaac Cruikshank. 38 For him, as for Southey, Charlotte was a ‘second Joan of Arc’ – a virginal youth acting with strength to free her nation. Cruickshank makes his opinion of Marat clear, both through his exaggerated features and

Isaac Cruikshank, A Second Jean d’Arc or the Assassination of Marat by Charlotte la Cordé of Caen in Normandy, 1793.

the details of notes scribbled on his wall, labelled ‘plans’ and ‘murders’. Gone is the bathtub, and instead Charlotte is shown taking Marat on in battle. Instead of Joan’s sword, she has her bloodied knife, and her beauty and femininity are exaggerated through her elaborate dress and hat. Her words ‘down, down to hell and say a female arm has made one bold attempt to free her country’, ring with the determination of Joan during her trial. She is driven by a higher belief that she is destroying a devil and saving her people.

But there is an irony in the comparison between Charlotte and Joan. In the eighteenth-century English press Charlotte is lauded, yet it was the English who were behind the arrest and execution of Joan of Arc in the fifteenth century. The 380 years separating the two women had witnessed a transformation of Joan’s legacy – from sinful scapegoat to a worthy warrior woman perceived as embodying the very best aspects of strong femininity. That Joan was a saintly woman who fought for the monarchy, and Charlotte was a Christian going against the Republic by killing Marat, may also have shone a forgiving light on these individuals in the eyes of traditionalist Englishmen and women, who were still clinging to Church and State in the eighteenth century. Today, her appeal has gone further, stretching across the political spectrum and across geographical lines.

Joan wasn’t always adored, and like Charlotte was executed surrounded by jeering detractors. Both women acted according to what they perceived as a ‘greater good’, but their motivations were different. Charlotte, a student of classical texts and political theory, wanted to save the Republic by removing a man who was undermining it with violence in the manner of Brutus. Joan, driven by spiritual ‘voices’ and religious fervour, threw her support behind the dauphin and rode into battle against English troops in the Hundred Years War, channelling the saints through her actions. Both women ended their lives despised by many, yet championed by a small circle of devotees. But they lived in very different worlds and need to be understood on their own terms. One French kingdom unites Charlotte and Joan: Normandy. Charlotte was born, lived and educated there, while Joan died there. Let’s turn our attention to its capital city – Rouen.

From Charlotte to Joan

30 May 1431, Rouen

The process has been exhausting. A year and a week ago today, Joan was captured and imprisoned. She has been moved from castle to castle, and her attempts to escape have led to personal injury and humiliation.39 Shown the instruments of torture, held in fetters day and night, even threatened with rape, Joan’s imprisonment has been unbearable.40 The dauphin has not come to her defence, and now she has suffered many months of endless interrogation, either in public courtrooms or her prison cell, under the scrutiny of over one hundred hostile assessors.41 So she has done something she knew would draw events to their dénouement. Just six days earlier she bent to the will of the court and rejected the male clothing she had worn almost exclusively since she first left her village of Domrémy three years earlier.

Dragged in front of a crowd in the cemetery of Saint-Ouen, Rouen, the city’s canon had read a rousing sermon, designed to bring Joan back into the fold. A pyre was built before her, a wooden stake erected, and she was threatened with death if she did not recant.42 While some witnesses say they saw her laughing, Joan declared before the crowd that she would denounce her spiritual ‘voices’ and would stop wearing immodest, shameful and dishonourable clothing, with her hair cut round like a man’s, but instead would wear women’s dress.43 In return, she would not be burned and would face life in prison. Her head shaved, she conceded to put on a gown, signing her recantation not with the ‘Jeanne’ she used for official documents, but with the ‘X’ she often reserved for relaying false information.44

The British representatives were furious that she had got off so lightly. They wanted her dead, humiliated, scrubbed from existence. Joan almost immediately reneged her recantation. She had been promised Mass and Communion if she kept wearing women’s clothing, but when this didn’t happen, she returned to an issue she had constantly raised during her trial. Hers was a religious trial for

public heresy, rather than a secular one, and had been brought by the Church. Therefore, she should have been kept in an ecclesiastical jail with women attendants.45 Instead, she has spent months in an English-held castle, with male soldiers as guards, her enemy literally at her gate.46 She has been consistently wronged, and her statement on returning to male clothing, which contains notes of sarcasm and resistance, reflects this:

Being amongst men, she thought that wearing men’s clothing was more lawful and appropriate than wearing women’s … If they allow her to go to Mass and release her from the chains, and if she is given an agreeable prison and a woman as a companion, she will be good.47

With regards to her male clothing, Joan’s words are strong and assertive. She wants what she is entitled to by law. But when it comes to rejecting her voices, she expresses fear, concerned that she has ‘damned her soul to save her life’ by denying her visions of saints Catherine, Margaret and Michael. In her dark prison cell, dressed in a tunic and breeches, she knows what this recantation will mean – she is a relapsed heretic, and she will burn.

It’s too late now. Joan cannot suffer imprisonment any longer. She will go out in a blaze of glory. Her spiritual guardians had said her flame would burn bright but short. An enormous crowd has gathered in the market square to watch the infamous ‘Pucelle’ –the 19-year-old virgin ‘maid’ – breathe her last. In the shadow of the Church of Saint-Sauveur, where Christian bodies lay buried beneath her feet from centuries earlier, Joan is going to join the dead. 48 But unlike them, her bones will be turned into ashes. While the Catholics interred beneath the square will be resurrected in body and soul at the Day of Judgement, she is confronted with the most terrifying end for a Christian – to be cremated, rather than buried in consecrated soil.49

Many of those who interrogated her day after day cannot face this final act of her drama and choose to stay away. But Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais and head of the court, has prepared

a last chastisement to send her to the pyre.50 She is ‘a dog returning to her vomit’ for having relapsed into heresy. He adds, ‘we cast you out, separate, and deliver you, praying the secular power to be lenient in its judgement toward you.’51 It is a farce. Cauchon has been the mouthpiece of the English throughout this whole process, and the Church wants no more leniency than her secular enemies. The lines are blurred. Church and State, religious and military, English and French, Joan is condemned by all as:

a pernicious temptress, presumptuous, credulous, rash, superstitious, a false prophetess, a blasphemer against God and his saints, scornful of God in his sacraments, a transgressor of divine law … seditious, cruel, apostate, schismatic, straying in many ways from our faith.52

These hideous insults wringing in her ears, Joan is led towards the stake. Wearing a white gown, she is bound by ropes that wrap around her body, forcing her arms to her side. Unable to move, she is grateful for a final act of kindness. Ysambart de la Pierre, a Dominican brother who had argued against torturing Joan in prison, shows his generosity once again by lifting a cross so she can see it as the flames are lit. 53 Her short but extraordinary life is drawing to a close, and her eyes fixed on Christ’s crucifixion she calls out ‘Jesu’ six times as the fast-burning flames engulf her flesh. The smoke overcame her before the fire did. When they were finally extinguished, the naked, burned body of Joan was displayed to the crowd of around 10,000 people. Through this act of degradation her executioners wanted to prove to the bystanders that she was a woman – some thought she could have been a man – and that she was finally dead (as some thought she was a witch, and so would be able to escape death with her supernatural powers). However, her humiliation wasn’t over. Some of her organs had not burned, so another pyre of wood was raised and she was burned a second time. When these flames went out, her persecutors were still concerned that devoted followers might collect small fragments from the ashes that they would treasure as relics.

Legenda

Lands recognising the Dauphin

Lands recognising Henry VI

Burgundian lands

Joan of Arc is born c. 5 Jan. 1412

Joan of Arc’s route 1429–1431

Journey to meet the Dauphin March 1429

Seige of Orléans May 1429

Ride for the Royal coronation July 1429

Military campaigns until May 1430

Capture and execution on 30 May 1431

Map showing the progress of Joan of Arc and the battles she was involved in, 1429–31.

She had to be completely eradicated. So she was burned a third time and the remains were scraped up, along with anything she had owned or touched, and cast into the Seine.

If the English prosecutors had hoped her death would signal the end of their efforts to undermine this most famous of fifteenthcentury women, the French army she led and the dauphin she supported, then they were wrong. In fact, by removing all physical remains of Joan, they achieved the opposite goal. Getty lists more than a thousand public representations of Joan. She is honoured in Orléans, where she broke the siege and turned the tide of the Hundred Years War, in Reims, where she led Charles the dauphin to his coronation, and in the cities she passed through on her military campaigns, including Troyes, Chinon, Compiègne and Paris. No figure is more ubiquitous among religious sites, market squares and street corners. Had she been granted a Christian burial, a cult may have grown up around her site of martyrdom, with Rouen laying claim to her. Ironically, by completely destroying Joan’s bodily relics, they inadvertently created a saint that belonged not to one church, town or region, but to everyone across France.

The Real Joan of Arc?

Is there anything new to be said about Joan of Arc? She is one of the best documented historical figures, with numerous books, articles, plays, films and artistic interpretations of her life down the centuries. But more often than not, Joan acts as a conduit for the time in which she is being interpreted.54 Take, for example, the 1999 film The Messenger, directed by Luc Besson and starring Milla Jovovich. The pixie-haired heroine embodies the 1990s: a woman in a man’s world, surrounded by the threat of male violence, disturbed, obsessive and potentially suffering from mental illness. She is as much an invention of the present day as a medieval woman:

We have created Joans to embody Marxist, democratic, populist, and patriotic political agendas; female heroes for feminists and gays; new-age shamans with mystical journeys and guardian angels. More recently, we discover Joan as psychotic, schizophrenic, delusional, manic-depressive, or any combination of these, apparently the legacy of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Freudian interpretations of her as the frustrated victim of overactive, pubescent hormones.55

Among all these interpretations there is one hugely important aspect of her life that tends to be overlooked by postEnlightenment writers and artists. To many today it is Joan the soldier that impresses. A teenage girl who could lead an army, she has been secularised and placed firmly in the world of men, battles, armies and warfare.56 But of much more importance to Joan was her spiritual framework. Rather than glimpse Joan backwards through the mists of time, reinterpreted through numerous lenses, we must look at her in the context of early fifteenth-century Lorraine. Joan had no notions of the feminist movements to come, of the social transformations, of modern developments in science and technology, urbanisation, industrialisation, revolution and secularisation. She was born into a world that could only look to the past for reference. And this