EX LIBRIS

VINTAGE CLASSICS

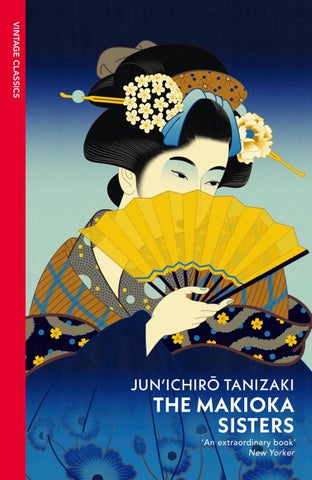

JUN’ICHIRŌ TANIZAKI

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki was one of Japan’s greatest twentieth century novelists. Born in 1886 in Tokyo, his first published work – a one-act play –appeared in 1910 in a literary magazine he helped to found. Tanizaki lived in the cosmopolitan Tokyo area until the earthquake of 1923, when he moved to the Kyoto-Osaka region and became absorbed in Japan’s past.

All his most important works were written after 1923, among them Some Prefer Nettles (1929), The Secret History of the Lord of Musashi (1935), several modern versions of The Tale of Genji (1941, 1954 and 1965), The Makioka Sisters, The Key (1956) and Diary of a Mad Old Man (1961). He was awarded an Imperial Award for Cultural Merit in 1949 and in 1965 he was elected an honorary member of the American Academy and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the first Japanese writer to receive this honour. Tanizaki died later that same year.

ALSO BY JUN’ICHIRŌ TANIZAKI

Naomi

Quicksand

Some Prefer Nettles

Arrowroot

Ashikari (The Reed Cutter)

A Portrait of Shunkin In Praise of Shadows

The Secret History of the Lord of Musashi

The Tale of Genji

Captain Shigemoto’s Mother

The Key

Diary of a Mad Old Man

JUN’ICHIRŌ TANIZAKI

THE MAKIOKA SISTERS

TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE BY Edward G. Seidensticker

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1957, 1983

The moral right of the author has been asserted

First published in Great Britain by Secker & Warbug in 1958

This paperback first published in Vintage Classics in 2025

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780749397104

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The Principal Characters

The four Makioka sisters:

Tsuruko, the mistress of the senior or ‘main’ house in Osaka, which by Japanese tradition wields authority over the collateral branches.

Sachiko, the mistress of the junior or branch house in Ashiya, a small city just outside of Osaka. For reasons of sentiment and convenience, the younger unmarried sisters prefer to live with her, somewhat against tradition.

Yukiko, thirty and still unmarried, shy and retiring, now not much sought after; so many proposals for her hand have been refused in earlier years that the family has acquired a reputation for haughti ness even though its fortunes are declining.

Taeko (familiarly called ‘Koi-san’), willful and sophisticated beyond her twenty-five years, waiting impatiently for Yukiko’s marriage so that her own secret liaison can be acknowledged before the world.

Tatsuo, Tsuruko’s husband, a cautious bank employee who has taken the Makioka name and who, upon the retirement of the father, became the active head of the family according to Japanese custom.

Teinosuke, Sachiko’s husband, an accountant with remarkable literary inclinations and far broader human instincts than Tatsuo; he too has taken the Makioka name.

Etsuko, Sachiko’s daughter, a precocious child just entering school.

O-haru, Sachiko’s maid.

Mrs Itani, owner of a beauty parlor, an inveterate gossip whose profession lends itself to the exciting game of arranging marriages.

Okubata (familiarly called ‘Kei-boy’), the man with whom Taeko tried to elope at 19, and whom she still sees secretly.

Itakura, a man of no background to whom Taeko is attracted after her betrothal to Okubata is too long delayed.

THE MAKIOKA SISTERS

Book I

‘Would you do this please, Koi-san?’

Seeing in the mirror that Taeko had come up behind her, Sachiko stopped powdering her back and held out the puff to her sister. Her eyes were still on the mirror, appraising the face as if it belonged to someone else. The long under-kimono, pulled high at the throat, stood out stiffly behind to reveal her back and shoulders.

‘And where is Yukiko?’

‘She is watching Etsuko practice,’ said Taeko. Both sisters spoke in the quiet, unhurried Osaka dialect. Taeko was the youngest in the family, and in Osaka the youngest girl is always ‘Koi-san,’ ‘small daughter.’

They could hear the piano downstairs. Yukiko had finished dressing early, and young Etsuko always wanted someone beside her when she practiced. She never objected when her mother went out, provided that Yukiko was left to keep her company. Today, with her mother and Yukiko and Taeko all dressing to go out, she was rebellious. She very grudgingly gave her permission when they promised that Yukiko at least would start back as soon as the concert was over—it began at two—and would be with Etsuko for dinner.

‘Koi-san, we have another prospect for Yukiko.’

‘Oh?’

The bright puff moved from Sachiko’s neck down over her back and shoulders. Sachiko was by no means round-shouldered, and yet the rich, swelling flesh of the neck and back somehow gave a suggestion of a stoop. The warm glow of the skin in the clear autumn sunlight made it hard to believe that she was in her thirties.

‘It came through Itani.’

‘Oh?’

‘The man works in an office, M.B. Chemical Industries, Itani says.’

‘And is he well off?’

‘He makes a hundred seventy or eighty yen a month, possibly two hundred fifty with bonuses.’

‘M.B. Chemical Industries—a French company?’

‘How clever of you. How did you know?’

‘Oh, I know that much.’

Taeko, the youngest, was in fact far better informed on such matters than her sisters. There was a suggestion occasionally that she took advantage of their ignorance to speak with a condescension more appropriate in someone older.

‘I had never heard of M.B. Chemical Industries. The head office is in Paris, Itani says. It seems to be very large.’

‘They have a big building on the Bund in Kobe. Have you never noticed it?’

‘That is the place. That is where he works.’

‘Does he know French?’

‘It seems so. He graduated from the French department of the Osaka Language Academy, and he spent some time in Paris—not a great deal, though. He makes a hundred yen a month teaching French at night.’

‘Does he have property.’

‘Very little. He still has the family house in the country— his mother is living there—and a house and lot in Kobe. And nothing more. The Kobe house is very small, and he bought it on installments. And so you see there is not much to boast of.’

‘He has no rent to pay, though. He can live as though he had more than four hundred a month.’

‘How do you think he would be for Yukiko? He has only his mother to worry about, and she never comes to Kobe. He is past forty, but he has never been married.’

‘Why not, if he is past forty?’

‘He has never found anyone refined enough for him, Itani says.’

‘Very odd. You should have him investigated.’

‘And she says he is most enthusiastic about Yukiko.’

‘You sent her picture?’

‘I left a picture with Itani, and she sent it without telling me. She says he is very pleased.’

‘Do you have a picture of him?’

The practicing went on below. It did not seem likely that Yukiko would interrupt them.

‘Look in the top drawer on the right.’ Puckering her lips as though she were about to kiss the mirror, Sachiko took up her lipstick. ‘Did you find it?’

‘Here it is. You have shown it to Yukiko?’

‘Yes.’

‘And?’

‘As usual, she said almost nothing. What do you think, Koi-san?’

‘Very plain. Or maybe just a little better than plain. A middling office worker, you can tell at a glance.’

‘But he is just that after all. Why should it surprise you?’

‘There may be one advantage. He can teach Yukiko French.’

Satisfied in a general way with her face, Sachiko began to unwrap a kimono.

‘I almost forgot.’ She looked up. ‘I feel a little short on “B”. Would you tell Yukiko, please?’

Beri-beri was in the air of this Kobe-Osaka district, and every year from summer into autumn the whole family—Sachiko and her husband and sisters and Etsuko, who had just started school— came down with it. The vitamin injection had become a family institution. They no longer went to a doctor, but instead kept a supply of concentrated vitamins on hand and ministered to each other with complete unconcern. A suggestion of sluggishness was immediately attributed to a shortage of Vitamin B, and, although they had forgotten who coined the expression, ‘short on ‘B’ never had to be explained.

The piano practice was finished. Taeko called from the head of the stairs, and one of the maids came out. ‘Could you have an injection ready for Mrs Makioka, please?’ 2

Mrs Itani (‘Itani’ everyone called her) had a beauty shop near the Oriental Hotel in Kobe, and Sachiko and her sisters were among the steady customers. Knowing that Itani was fond of arranging marriages, Sachiko had once spoken to her of Yukiko’s problem, and had left a photograph to be shown to likely prospects. Recently, when Sachiko went for a wave-set, Itani took advantage of a few spare minutes to invite her out for a cup of tea. In the lobby of the Oriental Hotel, Sachiko first heard Itani’s story.

It had been wrong not to speak to Sachiko first, Itani knew, but she had been afraid that if they frittered away their time they would miss a good opportunity. She had heard of this possible husband for Miss Yukiko, and had sent him the photograph—only that, nothing more—possibly a month and a half before. She heard nothing from the man, and had almost forgotten about him when she learned that he was apparently busy investigating Yukiko’s background. He had found out all about the Makioka family, even the main branch in Osaka.

(Sachiko was the second daughter. Her older sister, Tsuruko, kept the ‘main’ house in Osaka.)

. . . . And he went on to investigate Miss Yukiko herself. He went to her school, and to her calligraphy teacher, and to the woman who instructed her in the tea ceremony. He found out everything. He even heard about that newspaper affair, and he went around to the newspaper office to see whether it had been misreported. It seemed clear to Itani that he was well enough satisfied with the results of the investigation, but, to make quite sure, she had told him he ought to meet Miss Yukiko face to face and see for himself whether she was the sort of girl that the newspaper

article had made her seem. Itani was sure she had convinced him. He was very modest and retiring, she said, and protested that he did not belong in a class with the Makioka family, and had very little hope of finding such a splendid bride, and if, by some chance, a marriage could be arranged, he would hate to see Miss Yukiko try to live on his miserable salary. But since there might just be a chance, he hoped Itani would at least mention his name. Itani had heard that his ancestors down to his grandfather had been leading retainers to a minor daimyo (lord) on the Japan Sea, and that even now a part of the family estate remained. As far as the family was concerned, then, it would not seem to be separated by any great distance from the Makiokas. Did Sachiko not agree? The Makiokas were an old family, of course, and probably everyone in Osaka had heard of them at one time or another. But still—Sachiko would have to forgive her for saying so—they could not live on their old glory forever. They would only find that Miss Yukiko had finally missed her chance. Why not compromise, while there was time, on someone not too outrageously inappropriate? Itani admitted that the salary was not large, but then the man was only forty, and it was not at all impossible that he would come to make more. And it was not as if he were working for a Japanese company. He had time to himself, and with more teaching at night he was sure he would have no trouble making four hundred and more. He would be able to afford at least a maid, there was no doubt about that. And as for the man himself, Itani’s brother had known him since they were very young, and had given him the highest recommendation. Although it would be perfectly ideal if the Makiokas were to conduct their own investigation, there seemed no doubt that his only reason for not marrying earlier was that he had not found anyone to his taste. Since he had been to Paris and was past forty, it would be hard to guarantee that he had quite left women alone, but when Itani met him she said to herself: ‘Here’s an honest, hard-working man, not a bit the sort to play around with women.’ It was reasonable enough for such a well-behaved man to insist on an elegant, refined girl, but for some reason—maybe as a reaction from his visit to

Paris—he insisted further that he would have only a pure Japanese beauty—gentle, quiet, graceful, able to wear Japanese clothes. It did not matter how she looked in foreign clothes. He wanted a pretty face too, of course, but more than anything he wanted pretty hands and feet. To Itani, Miss Yukiko seemed the perfect answer. Such was her story.

Itani supported her husband, bedridden with palsy, and, after putting her brother through medical school, had this spring sent her daughter to Tokyo to enter Japan Women’s University. Sound and practical, she was quicker by far than most women, but her way of saying exactly what was on her mind without frills and circumlocutions was so completely unladylike that one sometimes wondered how she kept her customers. And yet there was nothing artificial about this directness—one felt only that the truth had to be told—and Itani stirred up little resentment. The torrent of words poured on as through a broken dam. Sachiko could not help thinking that the woman was really too forward, but, given the spirited Itani’s resemblance to a man used to being obeyed, it was clear that this was her way of being friendly and helpful. A still more powerful consideration, however, was the argument itself, which had no cracks. Sachiko felt as if she had been pinned to the floor. She would speak to her sister in Osaka, then, she said, and perhaps they could do a little investigating themselves. There the matter ended.

Some, it would appear, looked for deep and subtle reasons to explain the fact that Yukiko, the third of the four sisters, had passed the marriageable age and reached thirty without a husband. There was in fact no ‘deep’ reason worth the name. Or, if a reason had to be found, perhaps it was that Tsuruko in the main house and Sachiko and Yukiko herself all remembered the luxury of their father’s last years and the dignity of the Makioka name— in a word, they were thralls to the family name, to the fact that they were members of an old and once-important family. In their hopes of finding Yukiko a worthy husband, they had refused the proposals that in earlier years had showered upon them. Not one seemed quite what they wanted. Presently the world grew tired

of their rebuffs, and people no longer mentioned likely candidates. Meanwhile the family fortunes were declining. There was no doubt, then, that Itani was being kind when she urged Sachiko to ‘forget the past.’ The best days for the Makiokas had lasted perhaps into the mid-twenties. Their prosperity lived now only in the mind of the Osakan who knew the old days well. Indeed even in the mid-twenties, extravagance and bad management were having their effect on the family business. The first of a series of crises had overtaken them then. Soon afterwards Sachiko’s father died, the business was cut back, and the shop in Semba, the heart of old Osaka—a shop that boasted a history from the middle of the last century and the days of the Shogunate—had to be sold. Sachiko and Yukiko found it hard to forget how it had been while their father lived. Before the shop was torn down to make way for a more modern building, they could not pass the solid earthen front and look in through the shop windows at the dusky interior without a twinge of sorrow.

There were four daughters and no sons in the family. When the father went into retirement, Tsuruko’s husband, who had taken the Makioka name, became active head of the family. Sachiko, too, married, and her husband also took the Makioka name. When Yukiko came of age, however, she unhappily no longer had a father to make a good match for her, and she did not get along well with her brother-in-law, Tatsuo, the new head of the family. Tatsuo, the son of a banker, had worked in a bank before he became the Makioka heir—indeed even afterwards he left the management of the shop largely to his foster father and the chief clerk. Upon the father’s death, Tatsuo pushed aside the protests of his sisters-in-law and the rest of the family, who thought that something could still be salvaged, and let the old shop pass into the hands of a man who had once been a family retainer. Tatsuo himself went back to his old bank. Quite the opposite of Sachiko’s father, who had been a rather ostentatious spender, Tatsuo was austere and retired almost to the point of timidity. Such being his nature, he concluded that rather than try to manage an unfamiliar business heavily in debt,

he ought to take the safer course and let the shop go, and that he had thus fulfilled his duty to the Makioka family—had in fact chosen that course precisely because he worried so about his duties as family heir. To Yukiko, however, drawn as she was to the past, there was something very unsatisfactory about this brother-in-law, and she was sure that from his grave her father too was reproaching Tatsuo. It was in this crisis, shortly after the father’s death, that Tatsuo became most enthusiastic about finding a husband for Yukiko. The candidate in question was the heir of a wealthy family and executive of a bank in Toyohashi, not far from Nagoya. Since that bank and Tatsuo’s were correspondents, Tatsuo knew all he needed to know about the man’s character and finances. The social position of the Saigusa family of Toyohashi was unassailable, indeed a little too high for what the Makioka family had become. The man himself was admirable in every respect, and presently a meeting with Yukiko was arranged. Thereupon Yukiko objected, and was not to be moved. There was nothing she really found fault with in the man’s appearance and manner, she said, but he was so countrified. Although he was no doubt as admirable as Tatsuo said, one could see that he was quite unintelligent. He had fallen ill on graduating from middle school, it was said, and had been unable to go farther, but Yukiko could not help suspecting that dullness somehow figured in the matter. Herself graduated from a ladies’ seminary with honors in English, Yukiko knew that she would be quite unable to respect the man. And besides, no matter how sizable a fortune he was heir to, and no matter how secure a future he could offer, the thought of living in a provincial city like Toyohashi was unbearably dreary. Yukiko had Sachiko’s support— surely, said Sachiko, they could not think of sending the poor girl off to such a place. Although Tatsuo for his part admitted that Yukiko was not unintellectual, he had concluded that, for a thoroughly Japanese girl whose reserve was extreme, a quiet, secure life in a provincial city, free from needless excitement, would be ideal, and it had not occurred to him that the lady herself might object. But the shy, introverted Yukiko, unable though she was to open her mouth

before strangers, had a hard core that was difficult to reconcile with her apparent docility. Tatsuo discovered that his sister-in-law was sometimes not as submissive as she might be.

As for Yukiko, it would have been well if she had made her position clear at once. Instead she persisted in giving vague answers that could be taken to mean almost anything, and when the crucial moment came it was not to Tatsuo or her older sister that she revealed her feelings, but rather to Sachiko. That was perhaps in part because she found it hard to speak to the almost too enthusiastic Tatsuo, but it was one of Yukiko’s shortcomings that she seldom said enough to make herself understood. Tatsuo had concluded that Yukiko was not hostile to the proposal, and the prospective bridegroom became even more enthusiastic after the meeting; he made it known that he must have Yukiko and no one else. The negotiations had advanced to a point, then, from which it was virtually impossible to withdraw gracefully; but once Yukiko said ‘No,’ her older sister and Tatsuo could take turns at talking themselves hoarse and still have no hope of moving her. She said ‘No’ to the end. Tatsuo had been especially pleased with the proposed match because he was sure it was one of which his dead father-in-law would have approved, and his disappointment was therefore great. What upset him most of all was the fact that one of the executives in his bank had acted as go-between. Poor Tatsuo wondered what he could possibly say to the man. If Yukiko had reasonable objections, of course, it would be another matter, but this searching out of minor faults—the fellow did not have an intelligent face, she said—and giving them as reasons for airily dismissing a proposal of a sort not likely to come again: it could only be explained by Yukiko’s willfulness. Or, if one chose to harbor such suspicions, it was not impossible to conclude that she had acted deliberately to embarrass her brother-in-law.

Tatsuo had apparently learned his lesson. When someone came with a proposal, he listened carefully. He no longer went out himself in search of a husband for Yukiko, however, and he tried whenever possible to avoid putting himself forward in marriage negotiations.

There was yet another reason for Yukiko’s difficulties: ‘the affair that got into the newspapers,’ Itani called it.

Some five or six years earlier, when she had been nineteen, Taeko, the youngest of the sisters, had eloped with a son of the Okubatas, an old Semba family who kept a jewelry store. Her motives were reasonable enough, it would seem: custom would not allow her to marry before a husband was found for Yukiko, and she had decided to take extraordinary measures. The two families, however, were not sympathetic. The lovers were promptly discovered and brought home, and so the incident passed—but for the unhappy fact that a small Osaka newspaper took it up. In the newspaper story, Yukiko, not Taeko, was made the principal, and even the age given was Yukiko’s. Tatsuo debated what to do: should he, for Yukiko’s sake, demand a retraction? But that might not be wise, since it would in effect mean confirming the story of Taeko’s misbehavior. Should he then ignore the article? He finally concluded that, whatever the effect might be on the guilty party, it would not do to have the innocent Yukiko spattered. He demanded a retraction. The newspaper published a revised version, and, as they had feared, this time the public read of Taeko. While Tatsuo knew that he should have consulted Yukiko first, he knew too that he could not expect a real answer from her. And there was a possibility that unpleasantness might arise between Yukiko and Taeko, whose interests lay on opposite sides in the matter. He took full responsibility, then, after consulting only his wife. Possibly somewhere deep in his mind lay a hope that, if he saved Yukiko’s reputation even at the cost of sacrificing Taeko’s, Yukiko might come to think well of him. The truth was that for Tatsuo, in a difficult position as adopted head of the family, this Yukiko, so gentle and docile on the surface and yet so hard underneath, was the most troublesome of his relatives, the most puzzling and the most difficult to manage. But whatever his motives, he succeeded in displeasing both Yukiko and Taeko.

It was my bad luck (thought Yukiko) that the affair got into the papers. And there is no help for it. A retraction would have done no good, down in a corner where no one would have noticed it. And retraction or no retraction, I loathe seeing our names in the papers again. It would have been much wiser to pretend that nothing had happened. Tatsuo was being kind, I suppose, but what of poor Koisan? She should not have done what she did, but after all the two of them were hardly old enough to know what they should and should not do. It seems to me that the blame must really be laid on the two families for not watching them more carefully. Tatsuo has to take part of it, and so do I. People can say what they will, but I am sure no one who knows me can have taken that story seriously. I cannot think that I was hurt by it. But what of Koi-san? What if she becomes a real delinquent now? Tatsuo thinks only of general principles, and never of the people concerned. Is he not going a little too far? And without even consulting the two of us.

And Taeko, for her part: It is only right of him to want to protect Yukiko, but he could have done it without getting my name into the papers. It is such a little paper that he could have bought it off if he had tried, but he is always afraid to spend a little money.

Taeko was mature for her age.

Tatsuo, who felt that he could no longer face the world, submitted his resignation to the bank. It was, of course, not accepted, and for him the incident was closed. The harm to Yukiko, however, was irreparable. A few people no doubt saw the revised newspaper story and knew that she had been maligned, but no matter how pure and proper she might be herself, it was now known what sort of sister she had, and, for all her self-confidence, Yukiko presently found marriage withdrawing into the distance. Whatever she may have felt in private, she continued to insist that the incident had done her little harm, and there was happily no bad feeling between the sisters. Indeed Yukiko rather tended to protect Taeko from their brother-in-law. The two of them had for some time been in the habit of paying long visits to Sachiko’s house in Ashiya, between Osaka and Kobe. By turns one of them would be at the main house

in Osaka and the other in Ashiya. After the newspaper incident, the visits to Ashiya became more frequent, and now the two of them could be found there together for weeks at a time—Sachiko’s husband Teinosuke was so much less frightening than Tatsuo in the main house. Teinosuke, an accountant who worked in Osaka and whose earnings were supplemented by the money he had received from Sachiko’s father, was quite unlike the stern, stiff Tatsuo. For a commercial-school graduate, he had remarkable literary inclinations, and he had even tried his hand at poetry. Now and then, when the visits of the two sisters-in-law seemed too protracted, he would worry about what the main house might think. ‘Suppose they were to go back for a little while,’ he would say. ‘But there is nothing at all to worry about,’ Sachiko would answer. ‘I imagine Tsuruko is glad to have them away now and then. Her house is not half big enough any more, with all those children. Let Yukiko and Koi-san do as they like. No one will complain.’ And so it became the usual thing for the younger sisters to be in Ashiya.

The years passed. While very little happened to Yukiko, Taeko’s career took a new turn, a turn that was not without import for Yukiko too. Taeko had been good at making dolls since her school days. In her spare time, she would make frivolous little dolls from scraps of cloth, and her skill had improved until presently her dolls were on sale in department stores. She made French-style dolls and pure Japanese dolls with a flash of true originality and in such variety that one could see how wide her tastes were in the movies, the theater, art, and literature. She built up a following in the course of time, and, with Sachiko’s help, she had rented a gallery for an exhibit in the middle of the Osaka entertainment district. She had early taken to making her dolls in Ashiya, since the main Osaka house was so full of children that it was quite impossible to work there. Soon she began to feel that she needed a better-appointed studio, and she rented a room a half hour or so from Sachiko’s house in Ashiya. Tatsuo and Tsuruko in Osaka were opposed to anything that made Taeko seem like a working girl. In particular they had doubts about her renting a room of her own,

but Sachiko was able to overcome their objections. Because of that one small mistake, she argued, Taeko was even farther from finding a husband than was Yukiko, and it would be well if she had something to keep her busy. And what if she was renting a room? It was a studio, and not a place to live. Fortunately a widowed friend of Sachiko’s had opened a rooming house. How would it be, suggested Sachiko, if they were to ask the woman to watch over Taeko? And since it was so near, Sachiko herself could look in on her sister from time to time. Thus Sachiko finally won Tatsuo and Tsuruko over, though it was perhaps an accomplished fact they were giving their permission to.

Quite unlike Yukiko, the lively Taeko was much given to pranks and jokes. It was true that she had had her spells of depression after that newspaper incident; but now, with a new world opening for her, she was again the gay Taeko of old. To that extent Sachiko’s theories seemed correct. But since Taeko had an allowance from the main house and was able to ask good prices for her dolls, she found herself with money to spend, and now and then she would appear with an astonishing handbag under her arm, or in shoes that showed every sign of having been imported. Sachiko and her older sister, both somewhat uneasy about this extravagance, urged her to save her money, but Taeko already knew the value of money in the bank. Sachiko was not to tell Tsuruko, she said, but look at this—and she displayed her postal-savings book. ‘If you ever need a little spending money,’ she added, ‘just let me know.’

Then one day Sachiko was startled at a bit of news she heard from an acquaintance: ‘I saw your Koi-san and the Okubata boy walking by the river.’ Shortly before, a cigarette lighter had fallen from Taeko’s pocket as she took out a handkerchief, and Sachiko had learned for the first time that her sister smoked. There was nothing to be done if a girl of twenty-four or twenty-five decided she would smoke, Sachiko said to herself, but now this development. She summoned Taeko and asked whether the report was true. It was, said Taeko. Sachiko’s questions brought out the details: Taeko had neither seen nor heard from the Okubata boy after

that newspaper incident until the exhibit, where he had bought the largest of her dolls. After that she began seeing him again. But of course it was the purest of relationships, and she saw him very seldom indeed. She was after all a grown woman, no longer a flighty girl, and she hoped her sister would trust her. Sachiko, however, reproved herself for having been too lenient. After all, she had certain obligations to the main house. Taeko worked as the mood took her, and, very much the temperamental artist, made no attempt to follow a fixed schedule. Sometimes she would do nothing for days on end, and again she would work all night and come home red-eyed in the morning—this in spite of the fact that she was not supposed to stay overnight in her studio. Liaison among the main house in Osaka, Sachiko’s house in Ashiya, and Taeko’s studio, moreover, had not been such that they knew when Taeko left one place and was due to arrive at another. Sachiko began to feel truly guilty. She had been too lax. Choosing a time when Taeko was not likely to be in, she visited the widowed friend and learned of Taeko’s habits. Taeko had become so illustrious, it seemed, that she was taking pupils. But only housewives and young girls; except for craftsmen who made boxes for the dolls, men never visited the studio. Taeko was an intense worker once she got herself under way, and it was not uncommon for her to work until three or four in the morning. Since there was no bedding in the room, she would have a smoke while she waited for daylight and the first streetcar. The hours thus matched well enough with what Sachiko had observed. Taeko had at first had a six-mat1 Japanese room, but recently she had moved into larger quarters: a Western-style room, Sachiko saw, with a little Japanese dressing room on a level slightly above it. There were all sorts of reference works and magazines around the room, and a sewing machine, bits of cloth, and unfinished dolls, and pictures pinned to the walls. It was very much the artist’s studio, and yet something in it also suggested the liveliness of a very young girl. Everything was clean and in order. There was not even a stray

1 A mat is about two yards by one.

cigarette butt in the ash tray. Sachiko found nothing in the drawers or the letter rack to arouse her suspicions.

She had been afraid she might find incriminating evidence, and had for that reason dreaded the visit. Now, however, she was immensely relieved, and thankful that she had come. She trusted Taeko more than ever.

Two or three months later, when Taeko was away at her studio, Okubata suddenly appeared at the door and announced that he wanted to see Mrs Makioka. The two families had lived near each other in the old Semba days, and since he was therefore not a complete stranger, Sachiko thought she might as well see him. He knew it was rude of him to come without warning—so he began. Rash though they had been those several years before, he and Koi-san had been moved by more than the fancy of a moment. They had promised to wait, it did not matter how many years, until they finally had the permission of their families to marry. Although it was true that his family had once considered Taeko a juvenile delinquent, they saw now that she had great artistic talents, and that the love of the two for each other was clean and healthy. He had heard from Koi-san that a husband had not yet been found for Yukiko, but that once a match was made, Koi-san would be permitted to marry him. He had come today only after talking the matter over with her. They were in no hurry; they would wait until the proper time. But they wanted at least Sachiko to know of the promise they had made to each other, and they wanted her to trust them, and presently, at the right time, to take their case to the sister and brother-in-law in the main house. They would be eternally grateful if she would somehow see that their hopes were not disappointed. Sachiko, he had heard, was the most understanding member of the family, and an ally of Koi-san’s. But he knew of course that it was not his place to come to her with such a request. Such was his story. Sachiko said she would look into the matter, and sent him on his way. Since she had already suspected that what he described might indeed be the case, his remarks did not particularly surprise her. Since the two of them had gotten into the

newspapers together, she rather felt that the best solution would be for them to marry, and she was sure that the main house too would presently come to that conclusion. The marriage might have an unfortunate psychological effect on Yukiko, however, and for that reason Sachiko wanted to put off a decision as long as possible.

As was her habit when time was heavy on her hands, she went into the living room, shuffled through a stack of music, and sat down at the piano. She was still playing when Taeko came in. Taeko had no doubt timed her return carefully, although her expression revealed nothing.

‘Koi-san.’ Sachiko looked up from the piano. ‘Okubata has just been here.’

‘Oh.’

‘I understand how you feel, but I hope you will leave everything to me.’

‘I see.’

‘It would be cruel to Yukiko if we moved too fast.’

‘I see.’

‘You understand, then, Koi-san?’

Taeko seemed uncomfortable but her face was carefully composed. She said no more. 4

Sachiko told no one, not even Yukiko, of her discovery. One day, however, Taeko and Okubata ran into Yukiko, who was getting off a bus, just as they started to cross the National Highway. Yukiko said nothing, but perhaps half a month later Sachiko heard of the incident from Taeko. Wondering what Yukiko might have made of it, Sachiko decided to tell her everything that had happened: there was no hurry, she said—indeed they could wait until something had been arranged for Yukiko herself—but the two must eventually be allowed to marry, and when the time came Yukiko too should do what she could to get the permission of the main house. Sachiko

watched carefully for a change in Yukiko’s expression, but Yukiko showed not a sign of emotion. If the only reason for not permitting the marriage immediately was that the sisters should be married in order of age, she said when Sachiko had finished, then there was really no reason at all. It would not upset her to be left behind, she added, with no trace of bitterness or defiance. She knew her day would come.

It was nonetheless out of the question to have the younger sister marry first, and since a match for Taeko was as good as arranged, it became more urgent than ever to find a husband for Yukiko. In addition to the complications we have already described, however, yet another fact operated to Yukiko’s disadvantage: she had been born in a bad year. In Tokyo the Year of the Horse is sometimes unlucky for women. In Osaka, on the other hand, it is the Year of the Ram that keeps a girl from finding a husband. Especially in the old Osaka merchant class, men fear taking a bride born in the Year of the Ram. ‘Do not let the woman of the Year of the Ram stand in your door,’ says the Osaka proverb. The superstition is a deeprooted one in Osaka, so strongly colored by the merchant and his beliefs, and Tsuruko liked to say that the Year of the Ram was really responsible for poor Yukiko’s failure to find a husband. Everything considered, then, the people in the main house, too, had finally concluded that it would be senseless to cling to their high standards. At first they said that, since it was Yukiko’s first marriage, it must also be the man’s first marriage; presently they conceded that a man who had been married once would be acceptable if he had no children, and then that there should be no more than two children, and even that he might be a year or two older than Teinosuke, Sachiko’s husband, provided he looked younger. Yukiko herself said that she would marry anyone her brothers-in-law and sisters agreed upon. She therefore had no particular objection to these revised standards, although she did say that if the man had children she hoped they would be pretty little girls. She thought she could really become fond of little stepdaughters. She added that if the man were in his forties, the climax of his career would be in sight and there would

be a little chance that his income would grow. It was quite possible that she would be left a widow, moreover, and, though she did not demand a large estate, she hoped that there would at least be enough to give her security in her old age. The main Osaka house and the Ashiya house agreed that this was most reasonable, and the standards were revised again.

This, then, was the background. For the most part, the Itani candidate did not seem too unlike what they were after. He had no property, it was true, but then he was only forty, a year or two younger than Teinosuke, and one could not say that he had no future. They had conceded that the man might be older than Teinosuke, but it would of course be far better if he were younger. What left them virtually straining to accept the proposal, however, was the fact that this would be his first marriage. They had all but given up hope of finding an unmarried man, and it seemed most unlikely that another such prospect would appear. If they had some misgivings about the man, then, those misgivings were more than wiped out by the fact that he had never been married. And, said Sachiko, even if he was only a clerk, he was versed in French ways and acquainted with French art and literature, and that would please Yukiko. People who did not know her well took Yukiko for a thoroughly Japanese lady, but only because the surface (the dress and appearance, speech and deportment) was so Japanese. The real Yukiko was quite different. She was even then studying French, and she understood Western music far better than Japanese. Sachiko had a friend inquire whether Segoshi—that was his name—was well thought of at M.B. Chemical Industries, and could find no one who spoke ill of him. She had very nearly concluded that this was the opportunity they were waiting for. She should consult the main house. Then suddenly Itani appeared at the gate in a taxi. What of the matter they had discussed the other day? She was, as always, aggressive, and this time she had the man’s photograph. Sachiko could hardly admit that she had only begun to consider asking her sister in Osaka—that would make her seem much too unconcerned. They thought it a splendid prospect indeed, she finally answered,

but, since the main house was in process of investigating the gentleman, she hoped Itani would wait another week. That was very well, said Itani, but this was the sort of proposal that required speed. If they were in a mood to give a favorable answer, would they not do well to hurry? Every day she had a telephone call from Mr Segoshi. Had they not made up their minds yet? Wouldn’t she show them his photograph, and wouldn’t she see what was happening? That was why she had come, and she would expect an answer in a week. Itani finished her business and was off again in five minutes.

Sachiko, a typical Osakan, liked to take her time, and she thought it outrageous to dispose of what was after all a woman’s whole life in so perfunctory a fashion. But Itani had touched a sensitive spot, and, with surprising swiftness, Sachiko set off the next day to see her sister in Osaka. She told the whole story, not forgetting to mention Itani’s insistence on haste. If Sachiko was slow, however, Tsuruko was slower, especially when it came to marriage proposals. A fairly good prospect, one would judge offhand, she said, but she would first talk it over with her husband, and, if it seemed appropriate, they might have the man investigated, and perhaps send someone off to the provinces to look into his family. In brief, Tsuruko proposed taking her time. A month seemed a far more likely guess than a week, and it would be up to Sachiko to put Itani off.

Then, precisely a week after Itani’s first visit, a taxi pulled up at the gate again. Sachiko held her breath. It was indeed Itani. Just yesterday she had tried to get an answer from the Osaka house, said Sachiko in some confusion, but they still seemed to be investigating. She gathered that there was no particular objection. Might they have four or five days more? Itani did not wait for her to finish. If there was no particular objection, surely they could put off the detailed investigation. How would it be if the two were to meet? She had in mind nothing as elaborate as a miai, a formal meeting between a prospective bride and groom. Rather she meant simply to invite them all to dinner. Not even the people in the main house need be present—it would be quite enough if Sachiko and her

husband went with Yukiko. Mr Segoshi was very eager. And Itani herself was not to be put off. She felt that she really had to awaken these sisters to the facts of life. (Sachiko sensed most of this.) They were a little too fond of themselves; they continued to lounge about while people were out working for them. Hence Miss Yukiko’s difficulties.

When exactly did she have in mind, then, asked Sachiko. It was short notice, answered Itani, but both she and Mr Segoshi would be free the next day, Sunday. Unfortunately Sachiko had an engagement. What of the day after, then? Sachiko agreed vaguely, and said she would telephone a definite answer at noon the next day. That day had come.

‘Koi-san.’ Sachiko started to put on a kimono. Deciding she did not approve of it, she threw it off and took up another. The piano practice had begun again. ‘I have rather a problem.’

‘What is your problem?’

‘I have to telephone Itani before we leave.’

‘Why?’

‘To give her an answer. She came yesterday and said she wanted Yukiko to meet the man today.’

‘How like her!’

‘It would be nothing formal, she said, only dinner together. I told her I was busy today, and she asked about tomorrow. It was more than I could do to refuse.’

‘What do they think in Osaka?’

‘Tsuruko said over the telephone that if we were going, we should go by ourselves. She said that if they went along, they would have trouble refusing later. And Itani said she would be satisfied without them.’

‘And Yukiko?’

‘Yukiko is the problem.’

‘She refused?’

‘Not exactly. But how do you suppose she feels about being asked to meet the man on only one day’s notice? She must think we are not doing very well by her. I hardly know, though. She said nothing

definite, except that it might be a good idea to find out a little more about him. She would not give me a clear answer.’

‘What will you tell Itani?’

‘What shall I tell her? It will have to be a good reason, and we cannot afford to annoy her. She might help us again someday. Koisan, could you call and ask if we might wait a few days?’

‘I could, I suppose. But Yukiko is not likely to change her mind in a few days.’

‘I wonder. She is upset only at the short notice, I suspect. I doubt if she really minds so.’

The door opened and Yukiko came in. Sachiko said no more. There was a possibility that Yukiko had heard too much already.

‘You are going to wear that obi?’ asked Yukiko. Taeko was helping Sachiko tie the obi. ‘You wore that one—when was it?—we went to a piano recital.’

‘I did wear this one.’

‘And every time you took a breath it squeaked.’

‘Did it really?’

‘Not very loud, but definitely a squeak. Every time you breathed. I swore I would never let you wear that obi to another concert.’

‘Which shall I wear, then?’ Sachiko pulled obi after obi from the drawer.

‘This one.’ Taeko picked up an obi with a spiral pattern.

‘Will it go with my kimono?’

‘Exactly the right one. Put it on, put it on.’ Yukiko and Taeko had finished dressing some time before. Taeko spoke as though to a reluctant child, and stood behind her sister to help tie the second obi. Sachiko knelt at the mirror and gave a little shriek.

‘What is the matter?’

‘Listen. Carefully. Do you hear? It squeaks.’ Sachiko breathed deeply to demonstrate the squeak.

‘You are right. It squeaks.’

‘How would the one with the leaf pattern be?’

‘Would you see if you can find it, Koi-san?’ Taeko, the only one of the three in Western clothes, picked her way lightly through the collection of obis on the floor. Again she helped with the tying. Sachiko stood up and took two or three deep breaths.

‘This one seems to be all right.’ But when the last cord was in place, the obi began squeaking.

The three of them were quite helpless with laughter. Each new squeak set them off again.

‘It is because of the double obi,’ said Yukiko, pulling herself together. ‘Try a single one.’

‘No, the trouble is with the cloth.’

‘But the double ones are all of the same cloth. Folding it double only doubles the squeak.’

‘You are both wrong.’ Taeko picked up another obi. ‘This one will never squeak.’

‘But that one is double too.’

‘Do as I tell you, I have discovered the cause.’

‘But look at the time. You and your obis will have us missing everything. There never is much music at these concerts, you know.’

‘Who was it that first objected to my obi, Yukiko?’

‘I want to hear music, not your squeaking.’

‘You have me exhausted. Tying and untying, tying and untying.’

‘You are exhausted! Think of me.’ Taeko braced herself to pull the obi tight.

‘Shall I leave it here?’ O-haru, the maid, brought the medical equipment in on a tray: a sterilized hypodermic needle, a vitamin concentrate, alcohol, absorbent cotton, adhesive tape.

‘My injection, my injection! Yukiko, give me my injection. Oh, yes.’ O-haru had turned to leave. ‘Call a cab. Have it come in ten minutes.’

Yukiko was thoroughly familiar with the procedure. She opened the ampule with a file, filled the needle, and pushed Sachiko’s left

sleeve to the shoulder. After touching a bit of alcohol-soaked cotton to the arm, she jabbed with the needle.

‘Ouch!’

‘I have no time to be careful.’

A strong smell of Vitamin B filled the room. Yukiko patted the adhesive tape in place.

‘I too am finished,’ said Taeko.

‘Which cord will go with this obi?’

‘Take that one. The one you have. And hurry.’

‘But you know perfectly well how helpless I am when I try to hurry. I do everything wrong.’

‘Now then. Take a deep breath for us.’

‘You were right.’ Sachiko breathed earnestly. ‘You were quite right. Not a squeak. What was the secret?’

‘The new ones squeak. You have nothing to worry about with an old one like this. It is too tired to squeak.’

‘You must be right.’

‘One only has to use one’s head.’

‘A telephone call for you, Mrs Makioka.’ O-haru came running down the hall. ‘From Mrs Itani.’

‘How awful! I forgot all about her.’

‘And the cab is coming.’

‘What shall I do? What shall I tell her?’ Sachiko fluttered about the room. Yukiko on the other hand was quite calm, as if to say that the matter was no concern of hers. ‘What shall I say, Yukiko?’

‘Whatever you like.’

‘Not just any answer will do.’

‘I leave it to you.’

‘Shall I refuse for tomorrow, then?’

Yukiko nodded.

‘You want me to, Yukiko?’

Yukiko nodded again.

Sachiko could not see the expression on her sister’s face. Yukiko’s eyes were turned to the floor.

‘I will be back soon, Etsuko.’ Yukiko looked into the parlor, where Etsuko was playing house with one of the maids. ‘You promise to watch everything for us?’

‘And you are bringing me a present, remember.’

‘I remember. The little gadget we saw the other day, the gadget to boil rice in.’

‘And you will be back before dinner?’

‘I will be back before dinner.’

‘Promise?’

‘I promise. Koi-san and your mother are having dinner with your father in Kobe, but I promise to be back. We can have dinner together. You have homework to do, remember.’

‘I have to write a composition.’

‘You are not to play too long, then. Write your composition, and I can read it when I come back.’

‘Good-bye, Yukiko. Good-bye, Koi-san.’ Etsuko called only the oldest of her mother’s sisters ‘aunt.’ She spoke to Yukiko and Taeko as though they were her own sisters.

Etsuko skipped out over the flagstones without bothering to put on her shoes. ‘You are to be back for dinner, now. You promised.’

‘How many times do you think you need to ask?’

‘I will be furious with you. Understand?’

‘What a child. I understand.’

Yukiko was in fact delighted at these signs of affection. For some reason, Etsuko never clung quite so stubbornly to her mother, but Yukiko was not allowed to go out unless she accepted Etsuko’s conditions. On the surface, and indeed to Yukiko herself, her reasons for spending so much time in Ashiya were that she did not get along well with her brother-in-law, and that Sachiko was the more sympathetic of her older sisters. Lately, however, Yukiko had begun to wonder whether a still more important reason might not be her affection for Etsuko. She had not been able to find an answer when Tsuruko once complained that though Yukiko doted on Etsuko,

she paid almost no attention to the children at the main house. The truth of the matter was that Yukiko was especially fond of little girls Etsuko’s age and Etsuko’s sort. The main house was of course full of children, but, except for the baby, they were all boys who could not hope to compete with Etsuko for Yukiko’s affections. Yukiko, who had lost her father some ten years before and her mother when she was very young, and who had no real home of her own, could with no particular regrets have gone off the next day to be married, but for the thought that she would no longer see Sachiko, of whom in all the world she was fondest and on whom she most depended. No, she could still see Sachiko. It was the child Etsuko she would not see, for Etsuko would be changing and growing away from her, forgetting the old affection. Yukiko felt a little jealous of Sachiko, who would always have the girl’s love. If she married a man who had been married before, she hoped it would be a man with a pretty little daughter. Even should the child prove to be prettier than Etsuko, however, she feared she could never quite match the love she had for the latter. The fact that she had been so long in finding a husband caused Yukiko herself less anguish than others might have supposed. She rather hoped that if she could not make a match worth being really enthusiastic about, she would be left here in Ashiya helping Sachiko rear the child. That would somehow make up for the loneliness.

It was not impossible that Sachiko had deliberately brought the two together. When Taeko began making dolls in the room assigned to her and Yukiko, Sachiko arranged to move Yukiko into Etsuko’s room, a six-mat Japanese-style room on the second floor. Etsuko slept in a low wooden baby bed, and a maid had always slept on the straw-matted floor beside her. When Yukiko took the maid’s place, she spread two kapok mattresses on a folding straw couch, so that her bed was almost as high as Etsuko’s. She gradually began relieving Sachiko of her duties: nursing Etsuko when she was ill, hearing her lessons and her piano practice, making her lunch or her afternoon tea. Yukiko was in many ways better qualified to care for the child than was Sachiko. Etsuko was plump

and rosy-cheeked, but like her mother she had little resistance to ailments. She was always running a high fever or going to bed with a swollen lymph gland or an attack of tonsillitis. At such times someone had to sit up two and three nights running to change the poultices and refill the ice bag, and it was Yukiko who best stood the strain. Yukiko appeared to be the most delicate of the sisters. Her arms were very little fuller than Etsuko’s, and the fact that she looked as though she might come down with tuberculosis at almost any time had helped frighten off prospective husbands. The truth was, however, that she was the strongest of them all. Sometimes when influenza went through the house, she alone escaped. She had never been seriously ill. Sachiko, on the other hand, would have been taken for the healthiest of the sisters, but her appearance was deceiving. She was in fact quite undependable. If she tired herself, however slightly, taking care of Etsuko, she too was presently ill, and the burden on the rest of the family was doubled. The center of her father’s attention when the Makioka family had been at its most prosperous, she even now had something of the spoiled child about her. Her defenses were weak, both mentally and physically. Sometimes, as if they were older than she, her sisters would find it necessary to reprove her for some excess. She was therefore highly unqualified both for nursing Etsuko and for seeing to her everyday needs. Sachiko and Etsuko sometimes had real quarrels. There were those who said that Sachiko did not want to lose a good governess, and that when a prospective bridegroom appeared for Yukiko she stepped in to wreck the negotiations. Although Tsuruko at the main house was not inclined to believe the rumors, she did complain that Sachiko found Yukiko too useful to send home. Sachiko’s husband Teinosuke too was a little uneasy. For Yukiko to live with them was very well, he said, but it was unfortunate that she had worked her way between them and the child. Could Sachiko not try to keep her at more of a distance? To have Etsuko come to love her aunt more than her mother would not do. But Sachiko answered that he was inventing problems. Etsuko was clever enough for her age, and, however much she might seem to favor Yukiko, she really

loved Sachiko herself best. It was not necessary that Etsuko cling to her mother as she clung to Yukiko. Etsuko knew that Yukiko would one day leave to be married, that was all. To have Yukiko in the house was a great help, of course, but that would last only until they found her a husband. Sachiko knew how fond Yukiko was of children, and had let her have Etsuko to make her forget the loneliness of the wait. Koi-san had her dolls and the income they brought (and as a matter of fact she seemed to be keeping company with a man), whereas poor Yukiko had nothing. Sachiko felt sorriest for Yukiko. Yukiko had no place to go, and Sachiko had given her Etsuko to keep her happy.

To say whether or not Yukiko had guessed all this was impossible. In any case, her devotion when Etsuko was ill was something Sachiko or even a professional nurse could never have imitated. Whenever someone had to watch the house, Yukiko tried to send Teinosuke and Sachiko and Taeko off while she stayed behind with Etsuko. She would have been expected, then, to stay behind again today, but the concert was a small private one to hear Leo Sirota, and she could not bring herself to forgo a piano recital. Teinosuke having gone hiking near Arima Springs, Taeko and Sachiko were to meet him in Kobe for dinner. Yukiko decided to refuse at least the dinner invitation. She would be back for dinner with Etsuko.

‘What could be keeping her?’

Taeko and Yukiko were at the gate. There was no sign of Sachiko.

‘It is almost two.’ Taeko stepped toward the cab. The driver held the door open.

‘They have been talking for hours.’

‘She might just try hanging up.’

‘Do you think Itani would let her? I can see her trying to back away from the telephone.’ Yukiko’s amusement suggested again

that the affair was no concern of hers. ‘Etsuko, go tell your mother to hang up.’

‘Shall we get in?’ Taeko motioned to the cab.

‘I think we should wait.’ Yukiko, always very proper, would not get into the cab ahead of an older sister. There was nothing for Taeko to do but wait with her.

‘I heard Itani’s story.’ Taeko took care that the driver did not overhear her. Etsuko had run back into the house.

‘Oh?’

‘And I saw the picture.’

‘Oh?’

‘What do you think, Yukiko?’

‘I hardly know, from just a picture.’

‘You should meet him.’

Yukiko did not answer.

‘Itani has been very kind, and Sachiko will be upset if you refuse to meet him.’

‘But do we really need to hurry so?’

‘She said she thought it was the hurrying that bothered you.’

Someone ran up behind them. ‘I forgot my handkerchief. My handkerchief, my handkerchief. Bring me a handkerchief, someone.’ Still fussing with the sleeves of her kimono, Sachiko flew through the gate.

‘It was quite a conversation.’

‘I suppose you think it was easy to think up excuses. I only just managed to throw her off.’

‘We can talk about it later.’

‘Get in, get in.’ Taeko pushed her way into the cab after Yukiko. It was perhaps a half mile to the station. When they had to hurry they took a cab, but sometimes, half for the exercise, they walked. People would turn to stare at the three of them, dressed to go out, as they walked toward the station. Shopkeepers were fond of talking about them, but probably few had guessed their ages. Although Sachiko had a six-year-old daughter and could hardly have hidden her age, she looked no more than twenty-six or twenty-seven. The

unmarried Yukiko would have been taken for perhaps twenty-two or three, and Taeko was sometimes mistaken for a sixteen- or seventeen-year-old. Yukiko had reached an age when it was no longer appropriate to address her as a girl, and yet no one found it strange that she should be ‘young Miss Yukiko.’ All three, moreover, looked best in clothes a little too young for them. It was not that the brightness of the clothes hid their ages; on the contrary, clothes in keeping with their ages were simply too old for them. When, the year before, Teinosuke had taken his wife and sisters-in-law and Etsuko to see the cherry blossoms by the Brocade Bridge, he had written this verse to go with the souvenir snapshot:

Three young sisters, Side by side, Here on the Brocade Bridge.

The three were not monotonously alike, however. Each had her special beauties, and they set one another off most effectively. Still they had an unmistakable something in common—what fine sisters! one immediately thought. Sachiko was the tallest, with Yukiko and Taeko shorter by equal steps, and that fact alone was enough to give a certain charm and balance to the composition as they walked down the street together. Yukiko was the most Japanese in appearance and dress, Taeko the most Western, and Sachiko stood midway between. Taeko had a round face and a firm, plump body to go with it. Yukiko, by contrast, had a long, thin face and a very slender figure. Sachiko again stood between, as if to combine their best features. Taeko usually wore Western clothes, and Yukiko wore only Japanese clothes. Sachiko wore Western clothes in the summer and Japanese clothes the rest of the year. There was something bright and lively about Sachiko and Taeko, both of whom resembled their father. Yukiko was different. Her face impressed one as somehow sad, lonely, and yet she looked best in gay clothes. The sombre kimonos so stylish in Tokyo were quite wrong for her.

One of course always dressed for a concert. Since this was a private concert, they had given more attention than usual to their clothes. There was literally no one who did not turn for another look at them as they climbed from the cab and ran through the bright autumn sunlight toward the station. Since it was a Sunday afternoon, the train was nearly empty. Yukiko noticed that the middle-school boy directly opposite her blushed and looked at the floor as they sat down.

Etsuko was tired of playing house. Sending O-hana upstairs for a notebook, she sat down in the parlor to work on her composition. The house was for the most part Japanese, the only Western-style rooms being this parlor and the dining room that opened from it. The family received guests in the parlor and spent the better part of the day there. The piano, the radio, and the phonograph were all in the parlor, and during the winter, since only the parlor was heated, it was more than ever the center of the house. This liveliest of rooms attracted Etsuko. Unless she was ill or turned out by guests, she virtually lived there. Her room upstairs, though matted in the Japanese fashion, had Western furnishings and was meant to be her study; but she preferred to study and play in the parlor, which was always a clutter of toys and books and pencils. Everyone dashed about picking things up when there was an unexpected caller.

Etsuko ran to the front door when she heard the bell, and skipped back into the parlor after Yukiko. The promised gift was under Yukiko’s arm.

‘You are not to look at my composition.’ Etsuko turned the notebook face down on the table. ‘You brought what I asked for? Let me see.’ She pulled the package from Yukiko’s arm and lined up the contents on the couch. ‘Thank you very much.’

‘This was what you wanted?’

‘Yes. Thank you very much.’

‘And did you finish your composition?’

‘Stop. You are not to look at it.’ Etsuko snatched up the notebook and ran toward the door. ‘There is a reason.’

‘And what is that?’

Etsuko laughed. ‘Because I wrote about you.’

‘You think you ought not to write about me? Let me see it.’

‘Later. You can see it later. Not now.’

She had written about the rabbit’s ear, said Etsuko, and Yukiko figured slightly in the narrative. She would be embarrassed to have Yukiko look at it now. Yukiko should go over it carefully that night after Etsuko herself was in bed. She would get up early to make a clean copy before she started for school. Sure that Sachiko and the others would go to a movie after dinner and be late coming home, Yukiko had a bath with Etsuko and at about eight-thirty took her upstairs. Etsuko, a very bad sleeper, always talked excitedly for twenty minutes or a half hour after she was in bed. Putting her to sleep was something of a chore, and Yukiko always had to lie down and listen to the chatter. Sometimes she would go off to sleep herself and not wake up until morning, and sometimes, getting up quietly and throwing a robe over her shoulders, she would go downstairs to have a cup of tea with Sachiko, or the cheese and white wine Teinosuke occasionally brought out. Tonight a stiffness in the shoulders—she often suffered from it—kept her awake. Sachiko and the rest would not be home for some time, and it seemed a good chance to look at the composition. Making very sure that Etsuko was asleep, Yukiko opened the notebook under the night lamp.

the rabbit’s ear

I have a rabbit. Someone brought him and said, ‘This is for Miss Etsuko.’

We have a dog and cat in our house, and we keep the rabbit by itself in the hall. I always pet it in the morning before I go to school. Last Thursday I went out into the hall before I went to school. One ear stood up straight but the other was floped over. ‘ What a funny

rabbit. Why not make the other ear stand up?’ I said, but the rabbit did not listen. ‘Let me stand it up for you,’ I said. I stood the ear up with my hand, but as soon as I let go it floped over again. I said to Yukiko, ‘Yukiko, look at the rabbit’s ear.’ Yukiko pushed the ear up with her foot, but when she let go it floped over again. Yukiko laughed and said, ‘What a funny ear.’

Yukiko hastily drew a line under the words ‘with her foot.’

Etsuko was good at composition, and this too seemed well enough written. Looking in the dictionary to see whether ‘floped’ might just possibly be an acceptable spelling, Yukiko corrected only that. There did not seem to be any mistakes in grammar. The problem was what to do about that foot, however. She finally decided only to strike out the three unfortunate words. It would have been simplest to say ‘with her hand,’ but Yukiko had in fact used her foot, and she did not think it right to have the child telling a lie. If the sentence became a little vague, there was nothing to be done about it. But what if the composition had been taken off to school without Yukiko’s having seen it? Etsuko had caught her in an unseemly pose.

Here is the story of that ‘with her foot’:

The house next door to, or rather behind, the Ashiya house had for the last six months been occupied by a German family named Stolz. Since only a coarse wire-net fence stood between the two back yards, Etsuko immediately came to know the Stolz children.

At first they would glare through the fence and Etsuko would glare back, like animals warily testing each other, but before long they were moving freely back and forth. The oldest was named Peter, and after him came Rosemarie and Fritz. Peter appeared to be nine or ten, and Rosemarie, exactly Etsuko’s height, was probably a year or two younger than Etsuko. Foreign children tend to be large. Etsuko and the Stolzes were soon great friends. Rosemarie in particular came over after school each evening, and Etsuko used the affectionate ‘Rumi’ by which the German girl was known in her own family.

The Stolzes had, besides a German pointer and a coal-black cat, an Angora rabbit which they kept penned in the back yard. Etsuko, who had a cat and dog of her own, was not interested in the cat and dog next door, but the rabbit fascinated her. She was fond of helping Rosemarie feed it and of picking it up by the ears, and presently she was coaxing her mother to buy a rabbit for her. Although Sachiko had no particular objection to keeping animals, it would be sad, she thought, to have an animal die for want of good care. And of course they already had Johnny, the dog and Bell, the cat, and it would be a nuisance to have to feed a rabbit too. And there was nowhere in the house to keep it, since it would have to be penned apart from Johnny and Bell. Sachiko was still deliberating the problem when the man who cleaned the chimney came around with a rabbit. The rabbit was not an Angora, indeed, but it was very white and very pretty. Etsuko, upon consultation with her mother, decided that it would best be kept in the hall, out of reach of Johnny and Bell. The creature was a puzzle to Sachiko and the rest. Unlike a cat or a dog, it was completely unresponsive. It only sat with wide, staring, pink eyes, a strange, twitching creature in a world quite apart.

This was the rabbit of which Etsuko had written. Yukiko was in the habit of waking the girl, helping with her breakfast, seeing that she had everything she needed for school, and then going back to bed herself. It had been a chilly autumn morning. Yukiko, a kimono thrown over her nightgown, had gone to the door to see Etsuko off and found the girl earnestly trying to make the rabbit’s ear stand up. ‘See what you can do with it,’ Etsuko had ordered. Yukiko, hoping to solve the problem and see Etsuko off in time for school, and yet unwilling to touch the puffy animal, had tried lifting the ear between her toes. As soon as she took her foot away, the ear ‘floped over’ again.

‘What was wrong with what I had?’ Etsuko looked at the correction the next morning.

‘Did you really have to say I used my foot?’

‘But you did.’

‘Because I did not want to touch the thing.’

‘Oh?’ Etsuko did not seem satisfied. ‘Maybe I should say so, then.’

‘And what will your teacher think of my manners?’

‘Oh?’ Etsuko still did not seem entirely satisfied. 9

‘If tomorrow is bad, how would the sixteenth be? The sixteenth is a very lucky day.’

So Itani had said when Sachiko was caught by that telephone call. Sachiko was forced to agree. Two days passed, however, before Yukiko too agreed. Yukiko set as a condition that Itani keep her promise and only introduce the two, avoiding any suggestion of a formal miai. Dinner, then, was to be at six at the Oriental Hotel in Kobe. With Itani would be her brother, Murakami Fusajirō, who worked for an Osaka iron dealer (it was because he was an old friend of the man Segoshi that Itani had first come with her proposal, and he was of course a man without whom the party would not be complete), and his wife. Segoshi would be a sad figure all by himself, and yet it was hardly an occasion to justify calling his family in from the country; but fortunately there was a middle-aged gentleman named Igarashi who was a director of the same iron company and who came from Segoshi’s home town, and Murakami invited him to come along as a sort of substitute for the relatives expected at a miai. Including Sachiko, Teinosuke and Yukiko there would be a total of eight at the dinner.

The day before, Sachiko and Yukiko went to Itani’s beauty parlor. Sachiko, who meant only to have her hair set and had sent Yukiko in first, was awaiting her turn when Itani took advantage of a free moment to confer with her.

‘May I ask a favor?’ Itani sat down and, bringing her mouth to Sachiko’s ear, lowered her voice almost to whisper. She always spoke in the brisk Tokyo manner. ‘I’m sure I don’t need to tell you, but could you try to make yourself as old as possible tomorrow?’

‘Of course . . .’

But Itani had begun again. ‘I don’t mean that you should dress just a little more modestly than usual. You have to dress very modestly—make up your mind to it. Miss Yukiko is very attractive, of course, but she’s so slender. There is something a little sad about her face, and she loses a good twenty per cent of her charm when she sits beside you. You have such a bright, modern face—and you would attract attention anyway. So could you try at least tomorrow to set Miss Yukiko off? Make yourself look say ten or fifteen years older? If not, you might be just enough to ruin everything.’

Sachiko had received similar instructions before. She had been with Yukiko at a number of miai, and had been the subject of some discussion: ‘The older sister seems so lively and modern, and the younger one a little moody,’ or, ‘The older sister completely blotted out the younger.’ There had even been occasions when she had been asked not to come at all, and only Tsuruko at the main house had attended Yukiko. Sachiko’s answer was always that people simply did not see Yukiko’s beauty. It was true that she herself had a somewhat livelier face, a face that might be called ‘modern.’ But there was nothing remarkable about a modern face. Modern faces were to be found everywhere. She knew it was odd of her to be praising her own sister so extravagantly, but the beauty, fragile and elegant, of the sheltered maiden of old, the maiden who had never known the winds of the world—might one not say that Yukiko had it? Sachiko would not want Yukiko to marry a man who could not appreciate her beauty, indeed a man who did not demand someone exactly like her. But ardently though she defended Yukiko, Sachiko could not suppress a certain feeling of superiority. Before Teinosuke, at least, she was boastful: ‘They say I overshadow poor Yukiko when I go along.’ Teinosuke himself would sometimes suggest that Sachiko stay home or, ordering her to retouch her face or put on a more modest kimono, would say: ‘No, you are still not old enough. You will only lower Yukiko’s stock again.’ It was clear to Sachiko that he was pleased at having so impressive a wife. Sachiko had stayed away from one or two of Yukiko’s miai, but for the most part she went

in Tsuruko’s place. Yukiko occasionally said that she would not go herself if Sachiko was not with her. The difficulty was, however, that no matter how sombre Sachiko tried to make herself, her wardrobe was simply too bright, and after a miai she would be told that she still had not looked old enough.

‘That is what everyone says. I understand completely. I would have tried to look old even if you had not mentioned it.’

Sachiko was the only customer in the waiting room. The curtain that marked off the next room was drawn back, and Yukiko’s figure, under the dryer, was reflected in the mirror directly before them. Itani no doubt relied on the noise of the dryer to drown out her words, but it seemed to Sachiko that Yukiko’s eyes were fixed on them as if to ask what they were talking about. She was in a panic lest their lips give them away.

On the appointed day, Yukiko, attended by her sisters, started dressing at about three. Teinosuke, who had left work early, was there to lend his support. A connoisseur of women’s dress, he was fond of watching such preparations; but more than that, he knew that the sisters were completely oblivious of time. He was present chiefly to see that they were ready by six.

Etsuko, back from school, threw her books down in the parlor and ran upstairs.

‘So Yukiko is going to meet her husband.’

Sachiko started. She saw in the mirror that the expression on Yukiko’s face had changed.

‘And where did you hear that?’ she asked with what unconcern she could muster.

‘O-haru told me this morning. Is it true, Yukiko?’

‘It is not,’ said Sachiko. ‘Yukiko and I have been invited to dinner at the Oriental Hotel by Mrs Itani.’

‘But Father is going along.’

‘And why should she not invite your father too?’

‘Etsuko, would you go downstairs, please?’ Yukiko was looking straight ahead into the mirror. ‘And tell O-haru to come up. You will not need to come back yourself.’

Etsuko was generally not quick to obey, but she sensed something out of the ordinary in Yukiko’s tone.

‘All right.’

A moment later O-haru was kneeling timidly at the door. ‘You called?’ It was clear that Etsuko had said something. Teinosuke and Taeko, sensing danger, had disappeared.

‘O-haru, what did you tell the child today?’ Sachiko could not remember having spoken to the maids about today’s meeting, but it must have been through her carelessness that they guessed the secret. She owed it to Yukiko to discover how. ‘What did you say?’

O-haru did not answer. Her eyes were on the floor, and her whole manner was a confession of misconduct.

‘When did you tell her?’

‘This morning.’

‘And just what did you have in mind?’

O-haru, who was seventeen, had come to the house at fourteen. Now that she had become almost a member of the family, they found it natural to address her more affectionately than the other maids. Someone always had to see Etsuko across the national highway on her way to and from school, and the task was usually O-haru’s. Under Sachiko’s questioning, she let it be known that she had told the whole story to Etsuko on the way to school that morning. O-haru was a wonderfully good-natured girl, and when she was scolded she wilted so dismally that it was almost amusing.

‘I was wrong to let you overhear that telephone conversation, but you did overhear it, and you should have known well enough that it was secret. You should know that there are some things you talk about and some things you do not. Do you tell a child about something that is completely undecided? When did you come to work here, O-haru? Not just yesterday, you know.’

‘And not only this time.’ Yukiko took over. ‘You have always talked too much. You are always saying things you should have left unsaid.’

Scolded by the two in turns, O-haru stared motionless at the floor. ‘Very well, you may leave.’ But O-haru still knelt before them

as if she were dead. Only when she had been told three or four times to leave did she apologize in a barely audible voice and turn to go.