‘Superbly

written, entertaining and compelling’ DAVID GIBBINS

‘Puts the risk and the blood back into what sometimes seems just a lifeless parade’

MICHAEL PYE, AUTHOR OF THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

‘Superbly

written, entertaining and compelling’ DAVID GIBBINS

‘Puts the risk and the blood back into what sometimes seems just a lifeless parade’

MICHAEL PYE, AUTHOR OF THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Simon Park, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The List of Illustrations on p. ix constitutes an extension of this copyright page

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 12/14.75pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve ( UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library i SB n : 978–0–241–74132–0

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

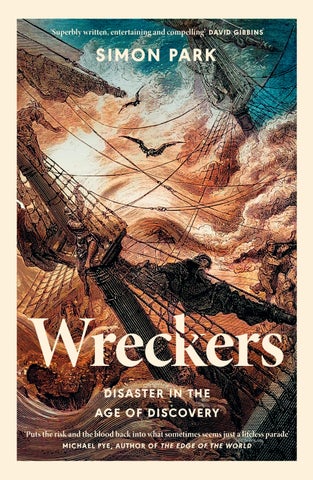

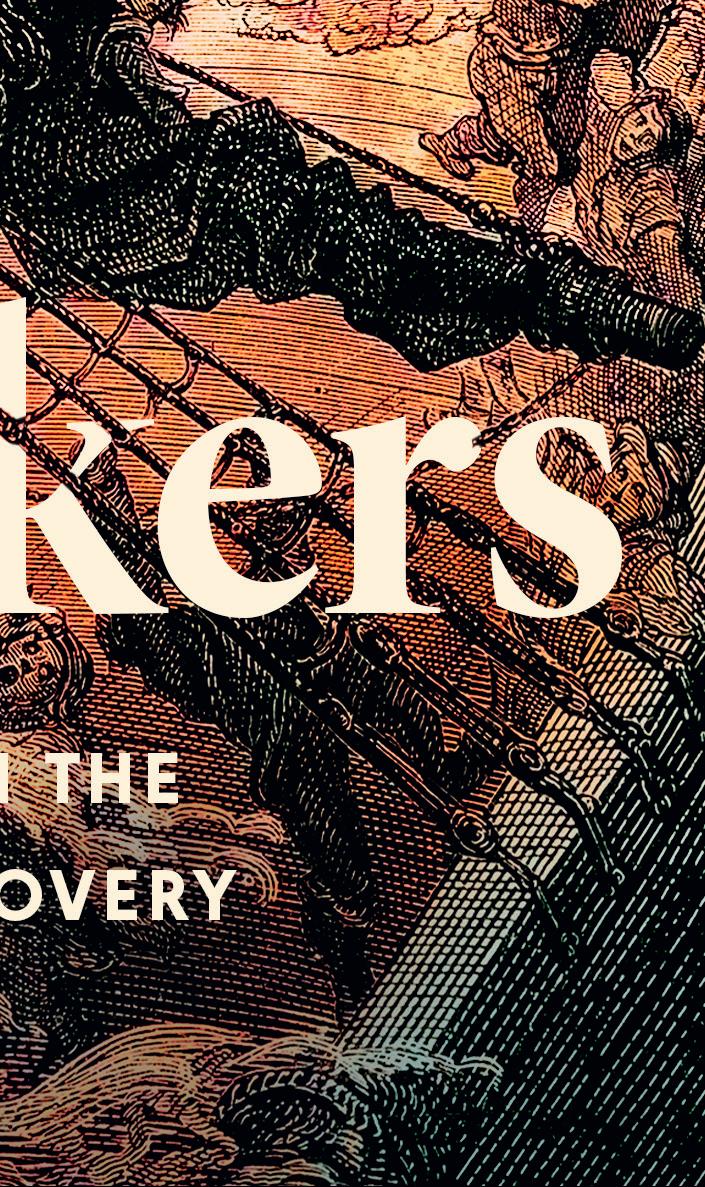

p. 5: The second fleet of Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500 and its fate (Alamy)

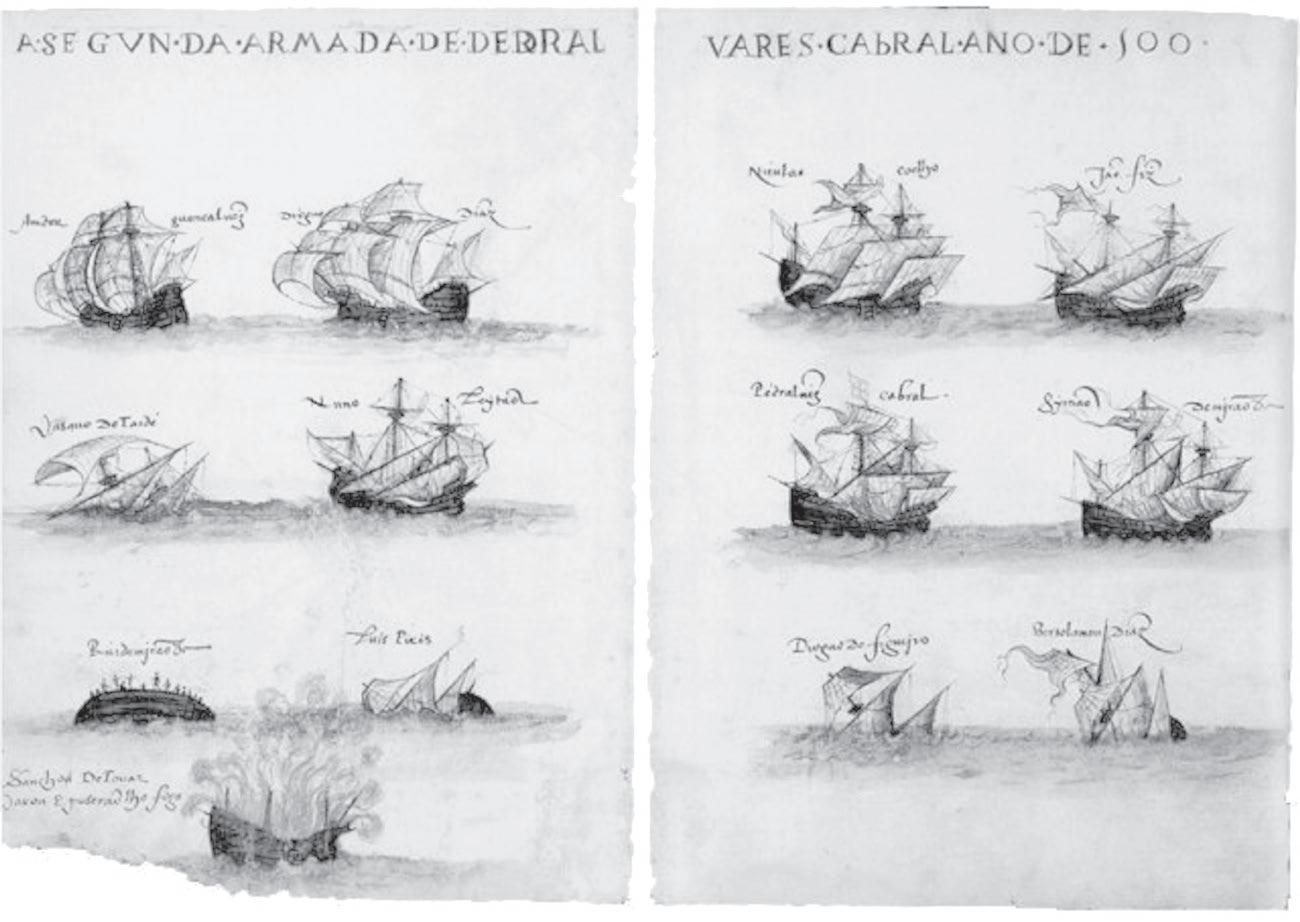

p. 6: Shipwreck of one of Fernão Soares de Albergaria’s fleet in 1552 (AKG )

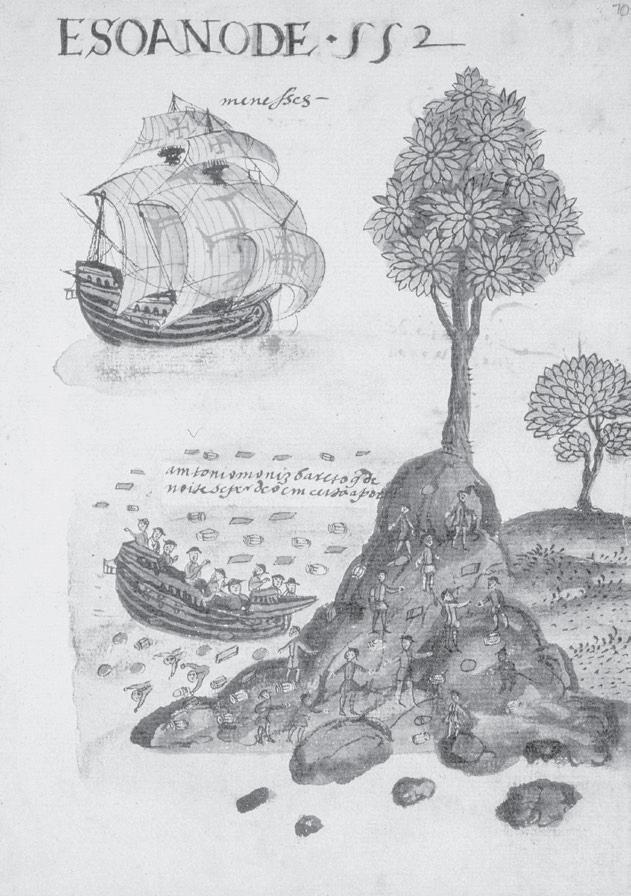

p. 6: Shipwreck of a Portuguese ship on the way to India in 1547 (AKG )

p. 12: Posthumous portrait of Vasco da Gama, c. 1565 (Alamy)

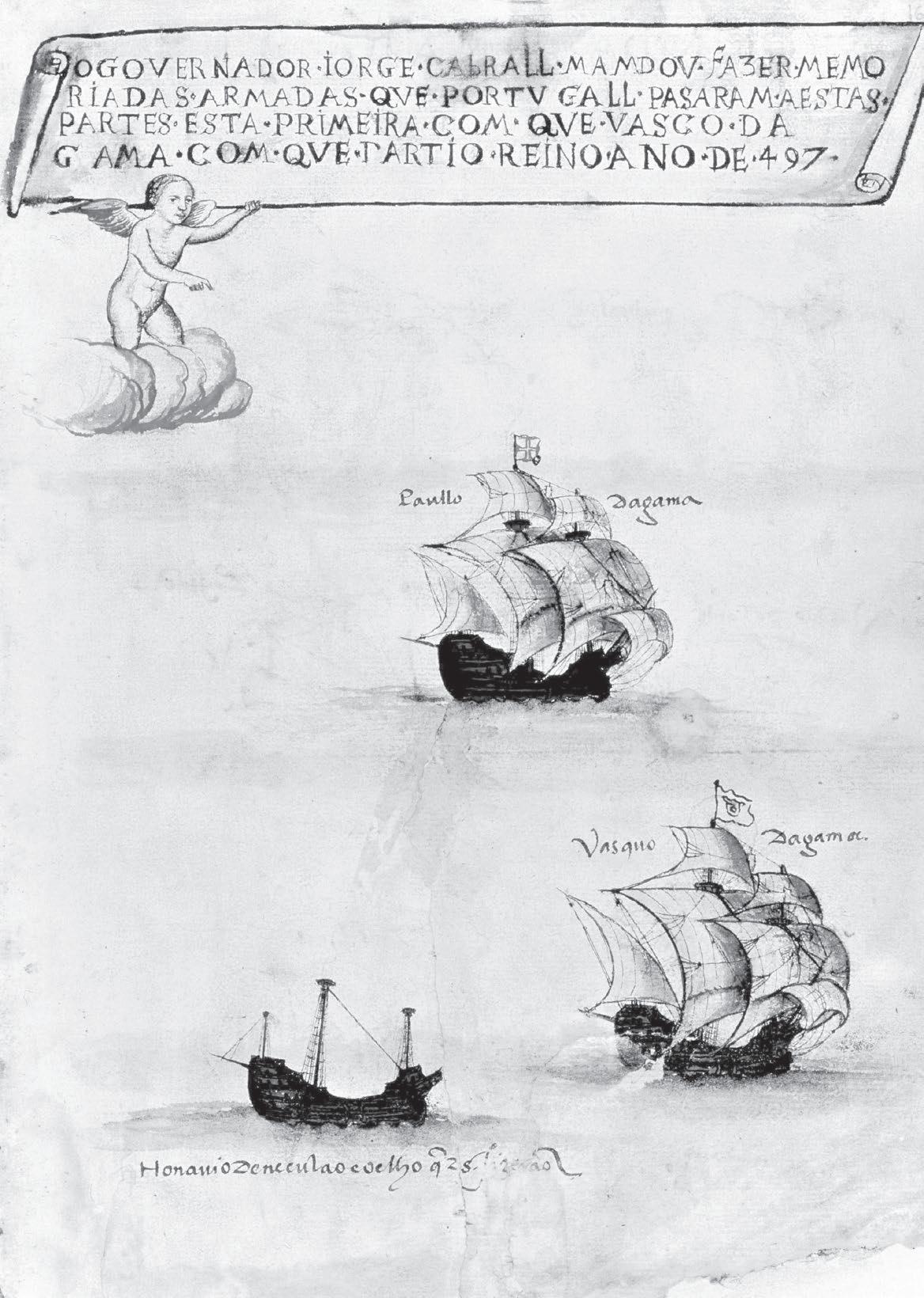

p. 15: Fleet of Vasco da Gama in 1497 (Alamy)

p. 37: Tapestry depicting Vasco da Gama’s arrival in Calicut in 1498 (Alamy)

p. 52: Bohíos in Hispaniola (BNE )

p. 55: The execution of Anacaona and the caciques of Jaragua in 1503 (Alamy)

p. 76: Posthumous portrait of Ferdinand Magellan, mid-sixteenth century (Bridgeman)

p. 79: The Strait of Melaka as depicted in the Cantino Planisphere, c. 1502 (Alamy)

p. 98: Manila galleon received by the Chamorro proas in the Ladrones Islands, c. 1590 (Lilly Library)

p. 102: Islands of Bohol, Cebu and Mactan as depicted in the only surviving Italian manuscript of Pigafetta’s account of Magellan’s voyage, c. 1523–5 (Alamy)

p. 105: Death of Magellan on Mactan, as portrayed in 1626 (Alamy)

p. 111: Kidlat Tahimik’s 2021 installation, Magellan, Marilyn, Mickey and Fr. Dámaso. 500 years of Conquistador RockStars (Alamy)

p. 117: Frieze in the church of Saint-Jacques in Dieppe, c. 1525–35 (Alamy)

p. 123: Portrait of Jean-François de la Rocque, Seiur de Roberval, 1535 (Bridgeman)

List of Illustrations

p. 127: Depiction of Jacques Cartier’s ship, c. 1697 (Wikicommons)

p. 129: Horse being transported in a ship, c. 1530 (Wikicommons)

p. 136: ‘The island where a French lady was exiled’, as portrayed in Thévet’s Cosmographie Univeselle, 1575 (John Carter Brown Library)

p. 137: An emblem about facing adversity, 1550 (Alamy)

p. 149: The City of Asunción (Paraguay), 1615 (Alamy)

p. 154: The captaincy of São Vicente in 1640 (ANTT )

p. 155: Detail of previous image (ANTT )

p. 159: A Tupinambá feather mantle, 1689 (National Museum, Denmark)

p. 164: Map of the coast of Brazil, 1542 (Bridgeman)

p. 165: Manioc roots as depicted by Albert Eckhout, 1640–50 (Wikicommons)

p. 166: The dance with the aracoía, as portrayed in 1557 (Alamy)

p. 167: Hans Staden at the Youngsters’ feast, as portrayed in 1557 (Alamy)

p. 170: Portrait of Cunhambebe, 1642 (Wikicommons)

p. 179: The Maria Bellete refuses to let Staden board, as portrayed in 1557 (Wikimedia)

p. 194: Black pepper from Cristóbal Acosta’s botanical treatise, 1578 (Wellcome)

p. 198: Shipwreck of the São João in 1552 (Wikimedia)

p. 207: Fragments of porcelain from the São João wreck (KZN Museum)

p. 215: The northwest passage depicted by Giovanni Francesco Camocio, 1567 (BNF )

p. 228: Prospecting for metal from Agricola’s treatise on metals, 1556 (Alamy)

p. 231: John White’s drawing of an Inuk, c. 1585– 93 (British Museum)

p. 232: A unicorn fish as depicted in George Best’s account of Frobisher’s voyages, 1578 (Proquest)

p. 243: Posthumous portrait of Martin Frobisher, 1620 (Alamy)

p. 18: Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India (1497–9)

p. 26: Key ports of call and trading centres on East African Coast (sixteenth century)

p. 48: Hispaniola (sixteenth century)

p. 65: Yucatán Peninsula (sixteenth century)

p. 79: Strait of Melaka (sixteenth century)

p. 86: Magellan’s Voyage (1519–21)

p. 100: Magellan’s route through the Philippines (1521)

p. 121: French Ports (sixteenth century)

p. 131: Cartier and Roberval’s voyages in 1542

p. 150: The coast of Brazil (sixteenth century)

p. 200: The coast of Southeast Africa (sixteenth century)

p. 230: Baffin Island (sixteenth century)

At the end of the fifteenth century, men in ships set off from the ports of Europe into the unknown. Tenacious, intrepid, they crossed oceans never before traversed and found lands they had never dreamed of.

But that’s far from the full story. When it comes to the first century of European transcontinental voyages by sea and the empires that were built on the back of them, we are too addicted to an action-hero version of history: triumphant beginnings with swashbuckling protagonists. Even recent books that challenge the history of empire struggle to avoid casting European captains as heroes who pushed forward the boundaries of knowledge. Yet building and maintaining an empire was not just a matter of reaching a faraway destination. It was, instead, a violent, messy, improvised process that took place over a long period of time. Disaster frequently struck early colonizers, and when it did, the foundations of empire trembled, even if the edifice did not immediately fall. Individuals, rulers and communities across the world rejected explorers, laughed at them and often set the rules of engagement in trade and territorial expansion despite European attempts to determine the world agenda with their weapons and their arrogance.

In his searing exposition of the history of European colonization and its after- effects in Latin America, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano provocatively concluded that ‘development is a voyage with more shipwrecks than navigators’.1 In the original Spanish, however, the word given as ‘shipwreck’ in the translation is náufrago, which refers more to the person wrecked than the vessel smashed apart. The slippage in the translation is slight, but important: Galeano is more interested in people than in ships. And so too is this book. Wreckers is about people who are wrecked, but also people who might be involved in the act of wrecking (and not just ships). The cast of characters in the chapters that follow occupy both these roles, wrecker and wrecked, hostage-taker and hostage to fortune. The central

premise of this book is to underline that both these facets of voyaging were at play during the age of so- called ‘discovery’ and that during the sixteenth century itself, tales of disaster, failure, resistance and comeuppance circulated widely and were as integral to comprehending empire as any bloated propaganda.

Overall, this book offers an alternative timeline of the hundred years after Columbus first crossed the Atlantic and reached the Caribbean in 1492, one that brings out the fractures and fault lines that accompanied the increasing geographical range of European ships. I have gathered stories from across languages and continents which entangle us in the allegiances and rivalries, fighting and fighting back, short tempers and blunders that were part and parcel of imperial advances. These stories show that the tide was often set against Europeans, not to lionize their efforts further by suggesting they succeeded ‘against the odds’, but to put them back into proper perspective. As we follow Europeans on their voyages, we learn that they did not just depart out of insatiable curiosity and the spirit of adventure. Europeans knew that West Africa, China and India abounded in goods and gold, so they set their course to these places, seeking a slice of their riches. They left, then, with a sense of lack and of envy usually concealed by noisy arrogance. They hoped that their risky ventures would change their countries’ fortunes. But the wreckers’ green eyes often led to sinking ships: they stacked them too high with merchandise or bankrupted investors by mistaking worthless rocks for treasure. They killed, abducted and enslaved.

Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Gonzalo Guerrero, Ferdinand Magellan, Jean-François de la Rocque, Marguerite de Roberval, Hans Staden, Manuel and Leonor de Sousa de Sepúlveda, Martin Frobisher: my cast of Spaniards, Portuguese, French, Germans, English get kidnapped, stranded, abandoned and betrayed. Most wash up on the coasts of the Americas, Asia or Africa not as triumphant conquistadores but as castaways clinging to the splintered timbers of wrecks, resisted by communities everywhere from Brazil to Southeast Africa, from India to the Philippines. The weather does weird and dangerous things in these stories, flings ships in unwanted directions, leaves them stranded, or hacks at their timbers until the

ship splits apart, turned inside out. We are used, perhaps, to thinking about shipwreck – the leitmotif of this book – as an ending: the premature, destructive culmination of a journey. But in these stories it is often just the prelude: the long and difficult part often comes next. After careering across the world’s oceans, these stories end up traipsing through jungle, over sands, up mountains, across plains.

In the first fifty years of the sixteenth century, around 12 per cent of the Portuguese ships on the route between Lisbon and India were wrecked, and this rose to 16–18 per cent between 1550 and 1650.2

Some 20 per cent of voyages travelling across the Pacific on the route between the Philippines and Mexico failed, either because of shipwreck or because the ships were forced to turn back.3 The figures are lower for the Spanish Atlantic route, but researchers in Spain have, nonetheless, catalogued some 700 different wrecks of Spanish ships off the coast of the Bahamas and the United States dating between 1492 and 1898.4 Estimates suggest around 7.5 per cent of English ships trading with the Indies during the Jacobean period were lost.5 Shipwreck was a fact of life and a persistent worry for seafarers’ families, merchants and bureaucrats alike, not just for their frequency but for the high toll of lives and financial loss involved when a ship did sink.6

Even when shipwrecks did not occur, many early attempts at colonization failed, with numerous places constantly embattled. In contrast to Spain’s rapid expansion in parts of Mexico and Peru, all seven of Spain’s attempts to colonize Florida during the sixteenth century failed.7 So, too, did Diego de Nicuesa’s attempt to colonize Panama in 1510 and Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa’s attempt to establish a colony near the Strait of Magellan in 1584.8 Further struggles in Panama and Yucatán are detailed in Part Two. All French attempts to establish colonies in the sixteenth century, in both North and South America, were eventually abandoned. Marguerite de Roberval’s story, encountered in Part Four, encompasses some of these struggles. While the later French empire developed differently, the early decades were not marked by easy imperial triumph. The Portuguese empire also faced constant challenges. For instance, it lost control of Aden in 1548, was expelled from Bahrain in 1602 and driven out of Hormuz by the Persians and English in 1622. It lost Mombasa by 1698 and was forced

to leave Muscat in 1650 after continuous attacks, including significant assaults in 1552 and 1581 by Ottoman forces. In India, the Portuguese struggled to maintain control over key locations such as Goa, Daman and Diu. Diu, in particular, faced repeated conflicts, including major sieges in 1538 and 1546 by Gujarati and Ottoman forces. In Morocco, the Portuguese established several forts from the fifteenth century onwards but were eventually driven out, including from Agadir in 1541, Ceuta in 1578 and Tangier in 1661.9 Elsewhere, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón’s colony in South Carolina in 1526 succumbed to disease and food shortages, while João Álvares Fagundes’s Newfoundland and Nova Scotia settlements in the 1520s were abandoned due to severe weather and conflicts with local peoples. Similarly, Sir Walter Raleigh’s ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke in 1587 probably vanished due to drought and local conflicts.10 Part Seven details how the English fared around Baffin Island. European expansion must be seen in tandem with these more challenging stories. Resistance, adverse weather, disease and misjudgements hindered, even if they did not halt, colonial ambitions across the globe.

Depending on where you are reading this book and with what experience, different characters may be more or less familiar to you: some are emblems of resistance or sources of (sometimes ambiguous) pride in different places around the world. But rarely do these individuals meet each other in the pages of a single book, meaning that comparisons and connections lie overlooked. Often narratives about empire limit themselves to national or linguistic boundaries, despite the fact that, as you’ll see, Europeans were constantly measuring themselves against each other and trying to occupy the same regions, and European individuals constantly kept shifting their allegiances. All their stories have had interesting afterlives. They have been translated and retold, had illustrations added or removed, been turned into theatrical spectacles or memorialized with statues (some of which have provoked protests). But the people and events in the chapters that follow have always been the subject of widespread debate. Many people of the past didn’t accept simplistic hero-worship any more easily than we do, and recovering that sense of continual contestation is crucial.

One important aspect of this book comes from my own scholarly upbringing and experience, and that is the inclusion of Portuguese materials. Documents and books written in Portuguese seldom appear more than fleetingly in historical studies of empire or of Renaissance Europe in general. Yet Portugal transported more slaves across the Atlantic than any other nation, and Portuguese is one of the most spoken languages of the southern hemisphere because of the country’s long and violent colonial history. As you’ll see, Portuguese pilots and ships end up appearing in several chapters of this book that are not ostensibly about Portugal at all. Those Portuguese materials are key to understanding the global picture of the past, and it is in Portuguese-speaking countries that some of the most compelling new ideas are emerging to redress that past.

To see what I mean by the dual dimensions of maritime history – catastrophe alongside transcontinental crossings – you only have to glance over the contents of a manuscript preserved today in the Morgan Library of New York. This set of images, produced in Goa in western India, between 1558 and 1565, catalogues the Portuguese

Shipwreck of one of Fernão Soares de Albergaria’s fleet in 1552

Shipwreck of a Portuguese ship on the way to India in 1547

armadas dispatched from Lisbon to Asia since Vasco da Gama’s first voyage to Calicut (Kozhikode) in 1497/8.

You would expect these hand- drawn pages of caravels and carracks to focus on the splendour of the fleets, the fanfare of trumpets and panoply of flags. But as you turn each page, you notice that many of the ships are in flames or are sinking into the deep, with planks, barrels and people scattered on the surface of the waves. It is a visual record of maritime might and seaborne disaster all thrown together. Take for instance, the two pages dedicated to Pedro Álvares Cabral’s fleet, which left Lisbon in 1500: winds urge the topmost ships on, blowing them across the ocean; but lower down, several ships are sinking, their prows nosediving into the water, their masts and sails wafting final signals of surrender to the sea. On the upturned hull of one vessel, figures stand shouting for help; another, shorn of its sails, is totally engulfed in flames. Other pages illustrate for us crates and barrels tossed into the sea, survivors on a shore, and there is even a cinematic shot of one ship plunging below the water’s surface as it

7 makes its descent towards the seabed. Disaster and what people of the period called ‘discovery’ were inseparable. The bare cluster of facts from this era that most of us have kept in our pockets since school don’t capture the untidiness of the past as presented to us in documents like this.

The biography of Christopher Columbus would be another case in point. He died wanting to believe that the Caribbean islands and the coast of South America that he visited were really Asia: he had hoped to reach the riches of China, India and Japan, but hadn’t. On his first voyage, the tiller of his flagship the Santa María was left in the hands of a ship’s boy; the vessel carelessly drifted into a sandbank off the island of Hispaniola (present- day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and broke up.11 A stockade was constructed out of the Santa María ’s timbers and thirty-nine men were left to defend it. When Columbus returned to the Caribbean on his second voyage in 1493, though, all those men had been killed by a cacique, or leader, called Caonaobó after the Spaniards had raided the interior for gold and women.12 His third voyage (1498–1500) ended with him being brought back to Spain in chains, after disputes with other captains who rightly questioned his abilities as a governor. During his fourth voyage in 1502, a fleet sent back to Spain by the governor of Hispaniola, Nicolás de Ovando, was ravaged, despite warnings from Columbus, by a hurricane that sank around twenty vessels.13After exploring the coast of the American mainland between present- day Belize and Panama, Columbus himself then ran into a storm while trying to return to Hispaniola. Day after day passed without seeing sun nor stars, the fear of certain death swirling relentlessly in the stormy darkness. The ships that survived were falling to pieces; those aboard so enfeebled that they were capable of little more than constant prayer.14 They ended up stranded in Jamaica for a year. Curiously, that very term ‘hurricane’ comes to us, via Spanish, from the word hurakán – ‘god of the storms’ in the language of the Taíno people of the Caribbean. The word’s etymology is a little trace of something that comes from outside Europe, and beyond its control, to rock the boat.

Much of what follows is based upon European sources, but it is crucial that we recover forgotten voices and neglected sources in

our collective attempts to decolonize the past. I do so by combining historical documents with the recent work of anthropologists and artists, inspired by a range of different indigenous perspectives, who are now creatively reshaping our understanding of the past across different art forms.15 Nevertheless, there still remains important work to be done with the European material, finding overlooked stories and sounding out their silences and contradictions in order to open up new ways of looking at this period in history. Moreover, there is a strange tension in some historical discourse whereby scholars expose the crushing violence and exploitation of empire yet still cling to a ‘great man’ view of the past, in which extraordinary individuals crossed frontiers and pushed forward the boundaries of knowledge. Our collective understanding still privileges single moments that apparently ‘changed the course of world history’, giving the events of the past cleaner edges and clearer consequences than they possessed for those who experienced them.16

We need a more realistic view of these individuals, not another tale of exceptionalism. We need to see that these so- called heroes learned from other traditions and relied on other people, whom they often compelled to do their bidding through torture and by stripping away their rights. They were halted in their ambitions by frequent resistance, and they got lost, made tactical miscalculations, and overloaded their ships, causing their own wrecks. At times, Europeans were just an unfriendly blip in the lives of peoples on other continents, arriving to dig up the earth and then shortly after leave again.

The stories gathered here don’t pretend to give a complete picture of this period, rather they are episodes that add grist to the progress of empire; a bit of friction to remind us it wasn’t all smooth going. You’ll see some of that larger picture in the series of timelines in this book, which give a sense of the turbulence felt during the intervals between the stories I tell.

One thing that has become very clear to me as I have put together this book is how alive the histories I am telling still are today. The events of this period, the source materials for them, and the longenduring afterlives of both, are all being vigorously renegotiated. Indigenous artists in Brazil, for instance, have punctured the visual

record of conquest with humorous additions to images and maps produced by Europeans. Across the globe, activists and artists are fighting for indigenous land rights, political sovereignty, and the repatriation of objects taken from their forebears. I see those contemporary actions as part of the historical story. For many, the choice to leave the past in the past is politically, intellectually, morally impossible. In this sense the past still feels unfixed, and it is being reimagined not within the pages of academic books, where scholars reveal the unearthing of new manuscripts and argue over the interpretation of the written record, but rather directly through people’s lives, livelihoods and surroundings. Heritage sites, monuments and museums, in particular, have become the focus for debate and protest.

This sense of debate is not just a characteristic of the present, however. The history of protest is as long as the history of empire. What’s more, the chronicles and archives that I draw upon often disagree with each other over what really happened and how we should interpret events. I don’t dwell on every discrepancy in the sources, but I do guide you through some of the gaps in the evidence and point out what some of the differences of opinion can tell us about the significance of the events being described, and how unspoken agendas have shaped what gets written down and remembered.

None of this – the multiple perspectives; the importance of argument to the production of history; the emphasis on failure – is intended to downplay the impact of Europeans, their weapons and diseases and religion, on the peoples and places that they encountered and often eventually colonized. That would be to forget about the big picture entirely. But it is important to remember that this history was disjointed, discontinuous and disconnected; no less brutal, no less violent, but differently so, not just unrelenting, inevitable domination. During the period itself, questions were often raised about empire, its whats, hows and whys. At times, it looked like disaster might win out over European ships and arms. So it is properly historical to retrieve some of that uncertainty. If we see empires simplistically as unstoppable, even as we condemn them we surrender to precisely those narratives that empires have sought to tell of themselves. Europeans did advance brutally and rapidly across the globe; but if we forget that they met

resistance and committed errors, we paint a misguided portrait of Europeans and we rob many of their agency.17

In returning to stories of failure, then, we gain a sense that history as we know it wasn’t predestined. Designs for imperial dominion, such as they existed, were constantly redrawn in the light of opposition, catastrophe, new knowledge and persistent errors. Stories of failure open up a space for something akin to what visual studies scholar, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, calls ‘potential histories’, where ‘different options that were once eliminated are reactivated as a way of slowing the imperial movement of progress’.18 Analysing how documents are written and then assembled to make up what scholars call an archive, acknowledging the limits of that archive, listening to those remaking our sense of the past in the present: all these things call on us to reimagine history, not as a series of predetermined events, but as a space of possibilities – then, now and in the future.

‘The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind,’ wrote Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (1776).1 It’s a view of the past that has been hard to shake: Christopher Columbus went west to America and Vasco da Gama went east to India, steering world history in radically new directions and towards greater interconnectedness. In one way, ceasing to be enthralled by this heroic view of the past isn’t so much about denying that these men did what they did, but rather looking more closely at their stories to consider what they really achieved, how they achieved it, and what their legacy was beyond the simple fact that they reached a place far from their point of departure. We saw in the introduction how Columbus failed on his own terms, going to the grave claiming America was China. Now we turn to the protagonist of Smith’s other great and important event, the Portuguese nobleman Vasco da Gama, who led the first European ship to reach India by sailing round the southern tip of Africa.

Even in the twenty-first century Da Gama is still voted one of ten grandes portugueses : Great Portuguese. But he wasn’t a likely candidate to become Portugal’s national hero. He hailed from the small town of Sines in the lower Alentejo, a place removed from any of the cities – Lisbon, Porto, Faro – that a tourist today might think important. And by the time his king appointed him captain-major of a small fleet that would supposedly redirect the course of world history, he hadn’t especially distinguished himself in any field. Scholars have been digging about in the Portuguese state archives for decades in search of information that might explain why the little-known Da Gama was selected by King Manuel to lead the 1497 expedition to India. As yet, though,

no crumpled piece of vellum with the answer has been extracted from the vaults of the Torre do Tombo, Lisbon’s national archive (which, from the outside, looks more like a nuclear bunker than a research library). Da Gama leapt into history from nowhere. It must be said that captains were primarily selected for being nobles rather than navigators – and were routinely satirized for not knowing their foresail from their yardarm – but it does still seem a little odd that the only trace of nautical involvement Da Gama had prior to 1497 was skippering a small expedition in well-known waters some five years earlier. Nothing on the scale of – or the difficulty of – a voyage to India lies in his background.

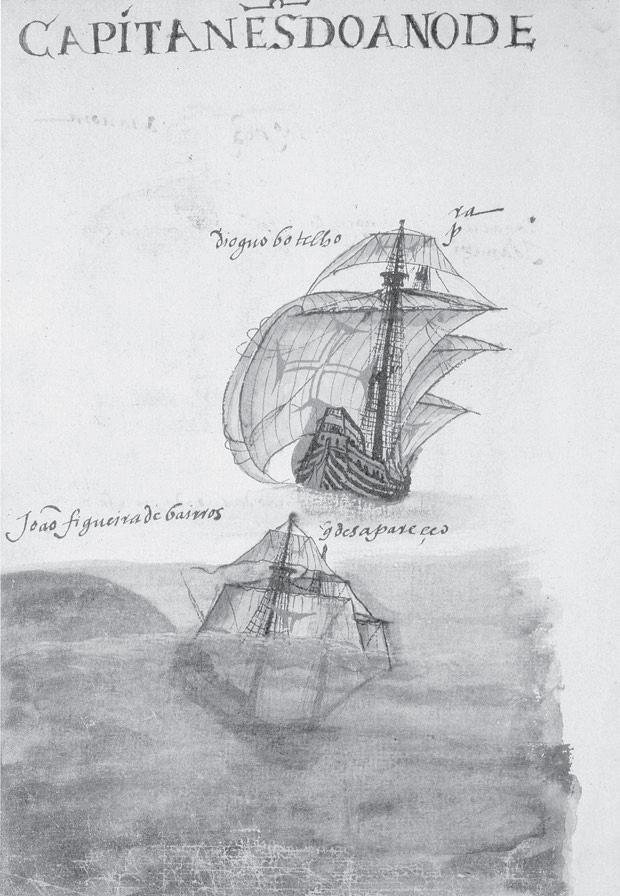

To explain away this blank space in Da Gama’s backstory, some historians have advanced the imaginative theory of Double- O-DaGama, suggesting he was a sailor-spy who had led secret reconnaissance missions down the coast of Africa prior to his breakthrough voyage, missions so top secret that they have left no archival trace. This fanciful theory tells us less about Da Gama himself than about how uncomfortable historians can find holes like this in the records and what fantasies they have concocted to plug them. A portrait of him from close to the end of his life and a quarter of a century after his first voyage to India, shows a tired-looking man in his fifties clutching a staff and gazing quizzically, perhaps even anxiously, into the distance.

Posthumous portrait of Vasco da Gama, c. 1565

There is little of the thrusting self-fashioning so common in the portraits of other governors and viceroys of the empire. He looks more wizened than triumphant. It is an interesting counterpoint to later and more grandiose portrayals that try to give the impression of a stereotypical adventurer; but, from what we know, Da Gama doesn’t appear to have been an upstart or a striver or a man of unquenchable curiosity – those types we typically recognize as history’s protagonists. He probably did not know much about the practical business of avoiding shoals and harnessing winds. As we’ll see, he was more a short-tempered opportunist. He did accomplish something unprecedented (with plenty of help); but it has been kings, dictators, poets and historians who have made him, retrospectively, into a hero.2

When Da Gama set out from the banks of the Tagus river, he sailed in the wake of almost a century of Portuguese exploration down the West African coast. His journey to India was an incremental, if crucial, advance in Portuguese voyaging. Since Portugal’s first incursion into North Africa, with the seizure of the stronghold of Ceuta in 1415, the country had been enriched by links with Africa, particularly the wealthy kingdoms in present- day Guinea and Sierra Leone, and had instigated the largest slave market in history. The aim, as the Portuguese sailed ever further south, was to round the southern tip of Africa and enter the Indian Ocean, where they could gain access to the trade in spices and other luxuries from Asia without any middlemen, and, they hoped, meet long-lost Christian kingdoms on the way. After many years of exploration, a crucial step forward was made in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope for the first time. But then followed a surprising interlude of navigational quiet lasting the nine years immediately preceding Da Gama’s voyage. It seems that King João II , despite ordering timber for the construction of two large ocean-going vessels, got cold feet about the long-standing quest to connect Portugal and India during the final years of his reign, or became embroiled in internal problems in his kingdom, or else was waiting to acquire further scientific information that would be useful for the voyage, such as the astronomical tables produced by the Jewish astronomer Abraão ben Samuel Zacuto.

The next chapter in the book of Portuguese exploration was thus left for João’s successor, King Manuel I, to write.

While overseas activities by the end of the fifteenth century had become very important for Portugal, they remained a controversial subject. The court at the time was divided over whether the mercantile ambitions of the king were a good thing or not. Many nobles grumbled that, rather than fixing its sights on Asia, the crown ought to be set instead on a crusade against Islam in North Africa, where the Portuguese had made their first imperial inroads. Fear that their own position might be undermined if the monarchy succeeded in controlling trade with the East, and thereby increasing its revenues, led to further hostility from the nobility. Traditionally, nobles liked to prove their worth on the battlefield and earn their lavish keep from owning land. Trading was for lesser sorts. Indeed, the French king François I allegedly dubbed Portugal’s Dom Manuel rather disparagingly the ‘grocer king’ (roi épicier ) for turning himself into a hawker of spices. But that might just have been envy talking, given the profits Manuel would make from trade with Asia. The selection of Da Gama was perhaps, then, a product of wrangling at court: nobles wanted one of their own involved if this enterprise was to go ahead. They didn’t want to be replaced by an emergent class of merchants and privateers.

The fleet entrusted to Da Gama consisted of two newly commissioned large ships, or naus, plus a caravel acquired by the king from a Lisbon-based pilot named Bérrio and a supply ship bought from Aires Correia, a shipowner also from the Portuguese capital.

The timber that King João II had ordered to be cut for two new ships in 1494 had been left unused in the royal storehouses. Within the first year of his reign, King Manuel sent these planks to shipbuilders in the northern city of Porto, where several Atlantic-worthy naus had been constructed over the course of the fifteenth century.3 Production started in the summer of 1496 and was completed during the first months of the following year. It was not a large fleet, which suggests some reticence on the part of the monarch over risking too much capital on this venture. The armadas sent to India in the years after Da Gama’s expedition would be several times larger.

The king’s instructions for the captain-major, given how little

the Portuguese knew of the world beyond Europe and West Africa, were somewhat vague. Da Gama was to reach India and hand the ruler there a letter from Dom Manuel written in Portuguese with an Arabic translation. The small matters of where exactly to dock in India, and how to get there, were left to Da Gama and his crew to decide. He set sail at the height of summer, in July 1497. It was not clear when, or if, he would return.

You might think that Vasco da Gama’s departure would be a moment of fanfare, with trumpets blaring and banners festooning the docks at Restelo. But when Luís de Camões – whose place in Portuguese literature can only be compared to Shakespeare’s in the anglophone canon – came to write the story of Da Gama’s voyage in his epic poem, The Lusiads, he somewhat surprisingly had the captain-major depart under a cloud.

Amid teary personal farewells and royal jubilation, an old man appears at the docks of Restelo in the poem. He scowls at the crowd. He shakes his head in grim disapproval. All fall silent as he begins to speak: ‘Oh, the grandeur of rulers! Oh, the empty craving for this vanity we call Fame! Oh, the fraudulent desire we call honour which tempts us with its vulgar sheen.’ His tirade continues: ‘To what new disasters have you decided to drag this kingdom and its people? What perils and deaths are you subjecting them to in the name of some glittering ideal?’ For the old man, Glory, Fame, Honour, Strength, Valour were delusions, words used to dress up a wicked enterprise in more appealing moral attire. Call it what you will, he declaims, it doesn’t change the cruelty, greed and pride of the undertaking. You can’t simply overlook death, disaster, profit-mongering by calling men heroes. This old man, like most old men in literature, was not afraid to tell it as it was.1

In some ways, Camões’s old man of Restelo is the emblem of this book. He’s a disruptive voice from the period of exploration, someone who didn’t want to forget what could go wrong and knew that there was always an alternative angle from which to tell a story. His viewpoint, bracingly countercultural though it seems, was still a Eurocentric one: what he wanted instead of trade and exploration in Asia was not peace, it was an anti-Islamic crusade; the lives he was so concerned about were Portuguese, not those killed and exploited by them.

This is not to say that his central point lacks any broader resonance, however. He raised an issue that early modern writers often worried about, namely that the difference between vice and virtue was more a question of language than of morality. The very same action might be called glorious by one man, greediness by another. One person’s bravery was another’s foolhardiness. Valour might, from a different angle, look like cruelty. Rhetoric, in other words, could twist and contort moral evaluation. Everything was a matter of spin. Greatness, the old man tells us, is conferred by the adjectives and nouns we choose to ascribe to actions. So far, history has tended to lean towards the aggrandizement of Da Gama, but we can find another set of words in the dictionary to describe his actions and what followed. Camões knew that back in the sixteenth century and was admitting it in the voice of his old man, even in a poem that is largely a long nationalistic boast.

That Camões interrupted a key moment of his story with a naysaying harangue also tells us that there were anxieties in the Portuguese court about what a voyage to India was going to achieve and why it was undertaken. Around seventy years after Da Gama’s journey, when Camões published his epic poem, there was still a bad taste in Portugal’s mouth. Strikingly, no one responds to the old man’s vituperations in the poem. No one refutes his claims, as though the conversations at the time had also reached a point where no compromise could be found. This silence sounds now like a tacit admission that, on balance, the prospect of gold did indeed weigh heavier than lives, just as the old man suggested.

After Da Gama left the Tagus behind, the first several hundred miles of his voyage should have been smooth sailing, given he was navigating well-travelled sailing routes.

Things weren’t so easy, though, because of one of the great unspoken players in history: the weather. A pall of fog engulfed the fleet soon after it had steered out into the Atlantic and the ships, unable to see each other, became separated. They had made plans to rendezvous in

the Cape Verde islands if they lost each other so early in the voyage, but it was not the best of starts. A few days later, we are told by the writer of the only remaining ship’s log from the voyage, three vessels found each other. There was still a ship missing, though. It was Da Gama’s. Holding their nerve, they stuck to the plan. The fleet without a flagship continued south to the prearranged rendezvous point, but the fickle Atlantic winds suddenly evaporated, stalling them for several days. As the winds picked up again, Da Gama’s ship at last appeared in the distance. They fired their cannons and blew their trumpets in delight – and relief. The mission, after all, wasn’t over before it had begun.2

Reunited, the fleet dropped anchor at Santiago, the largest of the Cape Verde islands, to make repairs and take on provisions. Then, in what seems at first to be a counterintuitive move, they sailed not directly south towards their goal, but west into the Atlantic to catch the favourable winds that would sweep the ships southeast and around the tip of Africa. Da Gama had the right idea by swinging out into the mid-Atlantic – these winds were the breakthrough meteorological discovery his predecessors had made – but he failed to execute the

manoeuvre perfectly and the ships reached land some 200 kilometres north of the Cape of Good Hope. A few days later, they again pulled into shore in search of a place to anchor, finding this time a sheltered inlet, which they named St Helena Bay. Their prime geographical adversary – the cape – still lay in wait down the coast.

At the newly christened St Helena Bay, Da Gama and his crew had their first encounter with people they did not know. After reading lots of logbooks and letters – the primary formats for recording cultural first impressions in the period – one begins to get a certain sense of déjà vu. They always note the same sorts of things about the peoples and places being encountered: their clothes, weapons and other goods, and food; the flora, fauna and climate. The catalogues are in some ways banal and obvious; these were tangible things the eye could easily take in. To compare the dogs here or there to pets back in Portugal was an easier undertaking than to grasp the familial or governance structures of a society when they had limited language skills and only a short window of time for observation. And readers back home were always eager for news of anything that seemed different: loincloths, piercings, flying fish. But beyond the blatant exoticizing, what catches their attention – and what gets left out – also implicitly reveals a clear set of imperial preoccupations: potential resources to exploit, opportunities for trade and conversion, likely threats.

On the day after Da Gama’s fleet anchored in St Helena’s Bay, they took a captive. You’ll soon see that hostage-taking became Da Gama’s signature modus operandi; one of the few ways he could gain leverage in a new place. After this hostage was fed and held against his will overnight, the Portuguese dressed him in their clothes and set him back on shore. For the Portuguese, one of the key metrics of difference with other peoples was how much a person covered up their body with cloth; the less skin a person showed, the more civilized they were. The forced re- costuming of this man was thus supposed to change him, win his favour, turn him into an ally. Whether the change of attire really worked or not, the next day around fifteen locals paid the ships a visit. Da Gama showed them cinnamon, cloves, seed pearls and gold, hoping that they would lead him to more of the same. They seemed to be uninterested in or unfamiliar with such items.