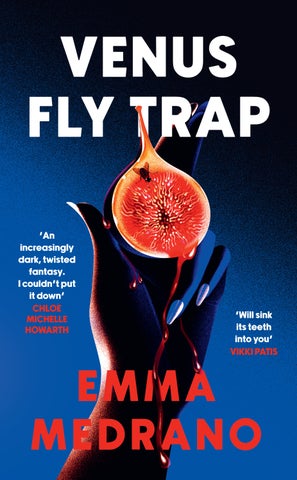

‘An increasingly dark, twisted fantasy. I couldn’t put it down’

CHLOE

MICHELLE HOWARTH

‘Will sink its teeth into you’ VIKKI PATIS

‘An increasingly dark, twisted fantasy. I couldn’t put it down’

CHLOE

MICHELLE HOWARTH

‘Will sink its teeth into you’ VIKKI PATIS

Also by Emma Medrano

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Emma Medrano, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 12/14.75pt Bembo MT

Typeset by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

hardback isbn: 978–0–241–70358–8 trade paperback isbn: 978–0–241–70359–5

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

If you see yourself in this book, it was written for you.

Love her, love her, love her! If she favours you, love her. If she wounds you, love her. If she tears your heart to pieces – and as it gets older and stronger, it will tear deeper – love her, love her, love her!

Great Expectations, Charles Dickens

Content warnings: Domestic abuse, suicide, self-harm, animal death.

The body lies where she left it.

He’s on the floor in the middle of the room. He died with his eyes wide open, staring at the ceiling. It’s not the blood that gives away the fact that he’s dead; it’s the eyes. You never notice someone blinking, but it’s so obvious when they stop. His eyes are dry and blank. They’re grey and foggy, the pupils melting into the brown to create a blurry mess. Despite that, he might be better-looking now than he was alive.

He has started to smell. It’s an odd scent, but it’s vaguely familiar; almost like the time last summer when she took a pack of beef stir-fry strips out of the fridge and forgot about them for a few hours. It’s warm. The windows are closed and the air feels hot and heavy. She pinches her nose shut. It’s not a pleasant smell.

But it is a pleasant sight.

His arms are outstretched like he’s making a snow angel in his own blood. It’s spilled out on both sides of him, the puddle bigger than when she last saw it. It isn’t spreading any more, but the poor wooden floors will never be the same.

Her mind itches with the sense that something is missing. Is there something she should do? A non-religious mark of respect, some sort of symbolic send-off to an afterlife that may or may not exist?

‘I’m sorry,’ she says.

She cringes. It’s only a half-lie anyway; she isn’t sorry

that he’s dead, but she is sorry it had to end this way. It did, though. There were no other options.

She crouches down next to him, careful not to touch the pool of blood. She takes his wrist. The skin is cold. She puts two fingers to the place where his pulse should be, even though she knows there won’t be one. She finds herself stroking his wrist, briefly wanting to take his hand, briefly wanting it all to have been a bad dream. Thank god it wasn’t.

She stands back up and takes out her phone. She takes a deep breath to prepare herself. One final time she goes over the script in her mind. There will be no room for mistakes. She gives herself a shake and dials 999. She makes herself sob, and she pretends to be confused when she gives the address. The operator on the other end does his best to console her and keep her calm. He has no idea her hands are steady and her eyes completely dry.

Cat had left another mess for me to clean up.

I stood in the doorway looking at the carnage in the kitchen. It would have been fine if I didn’t need breakfast, but I was already famished. There was no point asking Cat to clean up after herself. She was, of course, still asleep. Cat never woke up before eleven, though most often she didn’t emerge from her bedroom until noon.

There were pots on all four burners on the hob, bits of food dried to the insides. Crumbs all over the counters and a used chopping board covered in onion skin. An empty bottle of wine. Bowls and plates stacked so high in the sink you could barely get your hands underneath the tap.

I’d heard them the night before, cooking, blasting indie music I didn’t recognize until past midnight, talking and laughing. The shattering of glass followed by hysterical cackling. I saw now that the broken shards of a wine glass had been swept into a corner of the kitchen, to be disposed of by someone else.

I have never enjoyed mess. If I hadn’t been so desperate for a place to stay, so pleased at the suggestion that we become flatmates, I would have made more of an effort to ask Cat about her cleaning habits before I moved in. It was too late now.

I filled up the dishwasher and scrubbed the stubborn dry pieces of food from the pots, which had been there long enough to become one with the metal. I put on a pair of

plastic gloves to pull the food from the drain and poured bleach all over the sink, then thoroughly wiped down all the counters and the hob and the inside of the microwave. I placed the wine bottle in the glass-recycling bin and sat on my knees on the floor to sweep up every piece of glass.

It took me half an hour to make the kitchen presentable again, the hob clear, the counters clean, the stainless steel shining. My stomach was rumbling. I made myself a bowl of porridge and put it inside the microwave.

‘Good morning,’ said a voice in the doorway.

I turned. Henry the Eighth was standing there in only his pyjama bottoms, with a bit of stubble he hadn’t yet shaved off. It always grew so quickly. His cheekbones always looked so sharp. I hadn’t heard him enter.

‘Good morning,’ I said.

Henry did not apologize for the mess or thank me for cleaning it up. He took out two bowls from the cupboard, a jug of milk from the fridge and a carton of chocolate cereal. Two bowls. That meant Cat was awake too. We danced past each other in the kitchen, carefully avoiding any physical contact and apologizing under our breaths for standing in the way. He prepared their breakfasts and left before mine was done.

The first time I called him Henry the Eighth, it was almost an epiphany. The combination of their names together had seemed so familiar: Catherine and Henry. I registered it and said it out loud. ‘Henry the Eighth.’

It felt fitting. Henry was young, muscular and handsome now, but I could see a future version of him that had stopped watching his diet and going to the gym, that had grown complacent and had a leg that stank, and that replaced

one pretty young woman with another when he grew bored.

Cat had laughed more than I had expected. She told me it was a better nickname than I even knew, because he was also the eighth guy she’d ever been with. ‘Of course, the others weren’t called Henry, though I think one might have been.’

She twinkled her eyes and looked at me. ‘Which Catherine am I?’ she asked.

I considered carefully. ‘Catherine Howard,’ I said eventually. Because there must have been something about her, to catch the eye of a king the way she did, and I’d never met someone who had something as obviously as Cat does.

The nickname has stuck.

After the microwave beeped, I took my breakfast and went back to my room. They were both in the lounge by then. He was sitting and Cat was splayed across his lap, facing my direction. Her nipples were visible through her thin nightie, her legs smooth and hairless. Even without make-up and with her hair frizzy, she was gorgeous. They were the model of straight white coupledom.

I should have brought up the issue of the messy kitchen. She didn’t mention it. She did not say good morning. Cat smiled dreamily, distractedly, straight at me. She raised her hand for a small wave. I waved back. I did not say good morning either.

I went into my bedroom and ate breakfast at my desk.

I had a meeting with my dissertation supervisor that day. We met in his dingy little office in the philosophy building. The window was open to help with the oppressive summer heat, but the room still smelled suspiciously like he made a habit of smoking in there. His name was Robert; he was an

American in his early fifties. He had a photograph on his desk that looked to be twenty years old, of him and his wife and a toddler that must be grown up by now.

‘Welcome, Louise, welcome,’ he said. ‘Sit.’ He gestured to the chair across from his own and began to gather the books on the desk into a pile in the corner.

‘I must say,’ he said, ‘I’m quite excited to be your supervisor. You’ve always provided excellent work, and I look forward to hearing what you have to say in a less structured setting.’

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘I was happy to get you as my supervisor as well.’

He smiled awkwardly. ‘That’s good to hear.’

I wondered if he wanted to fuck me. Not that I believe every man wants to fuck me, but I know how men look at women. It’s always a consideration. They assess you like you’re cattle they’re about to purchase, even if you’re not for sale.

‘Do you know what you want to write about?’ he asked.

‘The categorical imperative,’ I said.

Robert put his hands together and placed them under his chin. I imagine not too many people are keen on writing about Kant, for good reason. Cat hated him. So did I, to be fair. But while it inspired revulsion in people like Cat, it spurred something else in me. A desire to fight him. A drive to prove him wrong.

‘Anything more specific than that?’ Robert asked.

‘I’m going to argue against it,’ I said. ‘Specifically the formula of universal law.’

‘On what grounds?’

‘I haven’t decided yet.’

‘Well, it’s quite a good start. How would you feel if we

met again in, say, two weeks’ time? Hopefully by then you’ll have a clearer direction.’

In the evening Cat knocked on my door. I’d just finished working out, and I hesitated to open it in my leggings with my face red. Working out was always a chore; I couldn’t stand to do it in a gym, which is the definition of sensory overload, with the loud music and dropping weights and the crowds of sweaty bodies. At home, however, I always risked getting detected by Cat, which felt a lot like being caught masturbating. Cat didn’t need to exercise to keep her stomach perfectly flat. It felt embarrassing to admit that I did, and my body still didn’t come close to hers. I followed online workout videos specifically for people with downstairs neighbours – no jumping involved.

But Cat knew I was home. I had to let her come in. She sauntered inside with a wine glass in one hand, gliding along the floor and over to my bed, sitting down on it. Cat always drank from a wine glass, even if drinking water or orange juice. Her manicured nails tapped on the glass thoughtfully.

‘Working out?’ she said, glancing at my attire.

‘Just wanted to move for a bit,’ I lied.

Every woman has told this lie. None of us is working out because it’s fun or feels good.

‘I need some of your motivation,’ said Cat, even though she didn’t. ‘Have you decided what you’re doing for your dissertation?’

‘Cunt?’ she said, frowning, when I told her. She always called him ‘Cunt’ instead of Kant. ‘Well, you’re a better man than I, Gunga Din.’

‘I’m arguing against him, of course.’

She nodded. ‘Of course. Can I do your make-up later?’

She cocked her head to one side and observed me as if she was taking notes.

‘Why?’ I asked. ‘I’m not going anywhere. I was just about to get in the shower.’

Cat was still in her nightie, but she had put on mascara, lined her eyes, and applied a pale pink lipstick that matched the outfit.

‘We’re having a party tonight.’ She took a sip from her glass. ‘Will you come?’

Other people might let their flatmate know in advance that they were having a party. I’d long ago stopped expecting that of Cat. I was no longer surprised when she informed me of a party hours before it was due to start.

I thought about attending. I hadn’t planned to do anything tonight, and my brain requires quite a bit of time to process it when plans change. At first I panic, struggle to breathe, go over a hundred reasons the original plan was better in the span of a few seconds. Then I get angry, feel a strong desire to claw and scratch and bite to maintain my plan and not allow it to change. Still, I never enjoyed it when Cat was having her monthly party and I was lying in my room trying to stay out of it. I would have to push my desk chair under the doorknob because there was no lock.

Once I was lying on my back in bed when a drunk stranger managed to stumble into the room; he didn’t realize I was there until I spoke up. It felt like a violation, like he had just seen me naked. Of course, I wouldn’t be able to sleep either. They would be laughing and talking and playing music until the early hours. Sometimes the neighbours from downstairs came up to knock on the door and Cat would have to persuade them not to call the police, promising the music would be turned down. It might be, for a minute or

two, until someone asked why the music was so low and someone else turned it all the way up again.

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘When will people start showing up?’

After my shower, I sat on the edge of my bed while she powdered my cheeks and rubbed eyeshadow on to my eyelids. Her face was so close to mine, closer than I think it had ever been before. There was a crease on her forehead from the concentration, her teeth biting into her lip. She was not wearing foundation, and she put none on me. Cat never needed foundation. Her skin was silky smooth and evenly coloured. Mine was not quite so flawless; I could not afford the kinds of face treatments she could. I did not have the money to inject my face with my own blood or cover it with gold. Cat said nothing about my blemishes and blackheads, even as she stared straight at them.

She dabbed her own lip gloss on my lips. It tasted like I imagined she would. She patted it with a finger and I felt the sudden urge to suck her finger into my mouth. Would she tell me to stop?

I didn’t do it, of course. I had always been attracted to Cat, but I knew she wouldn’t be interested. Besides, it’s best not to make a move on someone you live with. You don’t shit where you eat.

‘You’re beautiful,’ she said softly, almost whispering.

‘You’re a good liar,’ I said.

It was true. I had heard Cat tell many lies, and her tone never changed, her face never twitched. She smiled and shook her head.

When I left my room half an hour later, the party had started. I had purposely waited until around twenty people

had arrived, so the gathering would be large enough that we wouldn’t have to socialize as one big group. No one notices you in a crowd that big. It was already nearing ten, so I sighed, because there was no chance I would get to sleep on time. I go to bed at midnight, and before that I have to wash my face and read for half an hour to make sure I don’t lie awake for ages staring at the ceiling. At least it was Friday.

I pulled down the bottom of the too-short skintight dress I was wearing. Cat had left it on my bed to borrow. In her world that meant I never had to return it. If I tried, she’d wave me away and say she hadn’t worn it in ages so I might as well keep it. The dress was maroon, which was one of the colours she’d said suits me. With my bland hair that was somewhere between blonde and brown, and what was apparently my rosy undertone, she’d declared me a ‘cool summer’ and spent hours telling me what colours that meant I should wear. While I appreciated the effort, I’m still not sure what any of it means.

I’d tried to tame my hair, but that’s a battle I’ve never won. It remains frizzy no matter what I do to it. It doesn’t grow past my shoulders whichever products I use or however often I get it trimmed, so I usually keep it short, to make it seem intentional.

The volume of the music was still low enough that people could chat. I strained my ears to recognize one of the poppy eighties songs my mum used to blast when I was little. Cat never used the same playlist for her parties. She curated a new one for each occasion, all linked together in some way that always felt obvious but was often undefinable.

I spotted her across the room. She was wearing a short black-and-white corset dress with bell sleeves, like a

Victorian dress that had been cut off below the hip. She looked like she’d forgotten to tell everyone else that this was a costume party. She looked breathtaking.

Oliver was nearby. I was happy to see him. He raised his hand at me and waved. He was standing by himself, drinking straight from a wine bottle, looking gorgeous in a purple shirt that perfectly complemented his brown skin.

I went over. He didn’t hug me; Cat was the only one who always insisted on hugging me. Oliver knew that I despised hugs. At most he’d give me a peck on the cheek, if he was very excited. If it wasn’t for Cat, he would’ve been my best friend. Not that I’d ever tell him that, of course.

I’m your second-best friend? he’d say. Second to what, her? Is she aware you’re supposed to be best friends?

‘Can I have some of that?’ I asked.

‘Be my guest,’ he said.

I took the bottle and drank.

‘You look beautiful,’ he said.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘Cat lent me the dress.’

‘Really? Did you check what brand it is? You might sell it for a few hundred.’

‘I like it,’ I said.

Even though it was a little too tight, which made my stomach protrude. Even though it kept riding up, so that I had to pull down the bottom every once in a while when I walked. This probably wasn’t noticeable to anyone else. The ceiling light was off, and the LED strips on the walls tinted everything purple.

‘Her entire personality is such a ridiculous display of wealth,’ he said. ‘There’s a piano in your lounge, Louise. Does she even play the piano?’

Someone I didn’t know was tipsily playing around at it

just then, pressing random keys in ways that didn’t harmonize with the music flowing from the speakers.

‘She does,’ I said.

I liked to hear it softly from out in the lounge when I lay in bed at night, on the evenings when she was home by herself, without any friends or Henry.

‘I don’t trust anyone who can afford to have a piano in their lounge,’ Oliver said.

He was from a similar background to my own. At the time he supported himself through a successful OnlyFans. Until I met him, I hadn’t been aware that gay men were into OnlyFans, but it turns out they are. In the end, men are the same, regardless of sexuality.

Cat had spotted us now, and she came bounding across the room as if we hadn’t seen each other in ages.

‘Oliver!’ she shrieked.

‘Cat!’ he yelled back.

She threw her arms around him and he lifted her up.

‘Oh my god!’ he said. ‘You look wonderful!’

He put her back down on the floor. ‘Thank you!’ She smiled at me. ‘Always a relief to receive the seal of fashion approval from the gay.’

‘It’s well deserved,’ Oliver said.

‘Well, you look absolutely dreamy yourself.’ She batted her eyelashes at him. ‘You’re sure you’re not bi?’

It was hard to look away from her when she was flirting, even when it wasn’t aimed at me, even when I knew it was a joke.

Oliver put out his hands in an apologetic gesture. ‘Alas. Though it’s lucky for your Henry, isn’t it?’

Cat put a strand of her hair behind her ear and laughed. ‘Oh, he doesn’t have to know.’

I was reminded that Henry existed. I searched for him in the crowd as Oliver and Cat chatted, and spotted him sitting on the couch speaking to a man I didn’t recognize.

‘Well, I should be going,’ Cat said. ‘I need to play hostess and whatnot.’ She gripped Oliver’s hands tightly and looked him straight in the face. ‘You have a good time, both of you. Let me know if you need anything, anything at all.’

With that, she was gone, leaving behind only a faint cloud of her perfume.

‘I don’t understand how you can live with her,’ Oliver said. ‘She’s so intense.’

‘She’s not always like this,’ I said.

‘Come, let’s dance,’ he said.

No one else was dancing yet. Parties with Cat and Henry’s friends sometimes felt like socialite events rather than what I’d always imagined student parties would be like. People were just talking; I’m sure some were discussing politics. I didn’t have much to compare this to, though. I hadn’t been to many parties in my life. I’ve never been the kind of person you invite to anything.

‘I’m not drunk enough to dance yet,’ I said.

‘So drink more.’

We had a bit more of the wine he’d brought, and then I took him into the kitchen to find something else. People rarely brought their own bottles to Cat’s parties, but she supplied plenty. She offered wine and champagne and expensive liqueurs. The bottles were all over the kitchen counters at this point. Cat’s parties always felt spontaneous and unplanned; there were no decorations, no one was invited more than a week in advance, no dress code. Somehow there were still always drinks and snacks available and there was always a new playlist to dance to.

In the fridge I found a six-pack of Henry’s beers. I always imagined he liked to drink beer to feel closer to the working class, like a proper man. I poured two of the cans into two of his beer glasses. Oliver joked that their expensive ways were rubbing off on me. They weren’t, but I knew how to blend in.

‘Stay close to me,’ Oliver said, as we were going back into the lounge. ‘Stay close to me all night.’

I squeezed his arm. ‘I promise.’

They’re not going to eat you, I wanted to say, but I wasn’t sure that was true.

I kept my promise and held on to him as we ran into another girl I knew from class, Deirdre. Her false lashes were so long they hung over her eyes and gave her a sleepy look, and she talked to Oliver about the philosophy of language and looked out across the room as he explained, as if she wasn’t listening at all. I stayed out of the conversation and determined from his tone when I was supposed to laugh.

Meanwhile Cat was drifting through the room, making people laugh and making me jealous. I wished I had just some of that charisma and a quarter of her friend circle. Well, actually, maybe a quarter would be too much.

After an hour the mood to dance finally hit us, meaning we were tipsy, so Oliver and I danced, tight together like we were a couple. Bumping into others on the dance floor without apologizing, simply exchanging glances to acknowledge each other’s presence. Other people took our lead, or they were also feeling the effects of the alcohol. The music was all from the eighties: Kate Bush and Bon Jovi and the Bee Gees. We danced and danced and danced.

I was drunk when Cat joined us, throwing her hair around and laughing, swaying along to the music with her

face aimed up at the ceiling and her eyes closed. She was definitely drunk. When she looked at me, her eyes were red. Her cheeks were flushed. ‘Lolo,’ she said, the nickname only she had ever called me. She held my hips as we danced, and she told me I was so, so sexy, whispering it into my ear like she’d lost her voice in amazement. Her mouth was so close to my ear I thought she might nibble at my earlobe.

Henry threw himself into the mix, pulling Cat to himself. She melted against him, her hands roving over him the way they’d just been touching me.

‘Isn’t she gorgeous?’ she said, slurring her words.

He made eye contact with me above her head, his gaze burning into me. He looked at me like we shared a secret. Smirking with a soft nod.

‘She is,’ he said.

I believed him more than I believed Cat. He used to tell me that all the time when I was fucking him.

Cat and I met about a month into our master’s. We had a seminar on moral philosophy together, and for the first few sessions we didn’t talk to each other. I always noticed her, though. She spoke more than anyone else. She always looked glamorous, while the rest of us showed up in sweats and messy buns. Cat was so eye-catching that every time she entered the room or I spotted her somewhere on campus I felt as if I’d glimpsed someone famous.

The first time we spoke, she asked if she could sit next to me and then did so without waiting for an answer. I instantly wondered if I had toothpaste in the corners of my mouth. She smelled just like how I’d imagined she would: fresh and clean and botanical. I’d thought she would be less perfect up close, that she’d have pores or that her hair would be frizzy, but none of that was true. That day she was wearing a top with romantic sleeves which exposed her shoulders, her hair dripping with tiny pearls.

‘I can’t sit next to the girl with the mullet again,’ she said. ‘She always asks the most stupid questions.’

I’d thought the girl with the mullet was her friend. They hugged every time they saw each other and would walk out of the seminar chatting and smiling. I had wondered why, though, because the girl with the mullet did ask the most ridiculous questions.

Cat sighed. ‘God, I sound like an absolute bitch, don’t I?’

The girl with the mullet came into the room. She saw

Cat sitting at the far end of the table, and I watched as her gaze drifted over to me, occupying the only seat next to Cat.

‘Hey, Cat,’ she said.

‘Hi!’ said Cat.

She smiled so wide I couldn’t believe it was fake. She sounded so cheery. The girl with the mullet sat down far away from us, and the smile faded from Cat’s face instantly. I couldn’t help but stare. I’d tried to do what she was doing; I’d tried to pretend to care about people I couldn’t give two fucks about; I’d tried to look like I was listening when I wasn’t, and every single time I was called out on it. Everyone knew just how cold and unusual I was.

She turned back to me. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I didn’t introduce myself. I’m Cat.’

‘Louise,’ I said.

‘Louise,’ she said. ‘I love your sweater. Where did you get it?’

My cheeks felt red and hot at the compliment. Usually only men ever complimented me, and that’s different. It’s nothing like being complimented by a woman as beautiful as Cat.

‘I can’t remember,’ I lied, because it was a charity-shop find, and Cat carried her laptop in a Karl Lagerfeld bag.

‘Well, it’s gorgeous,’ she said, opening said laptop. ‘Cool colours really suit you. By the way, though, there’s a bit of foundation on the sleeve.’

I covered the sleeve with my hand. She was right, of course. There was a patch of beige on the sleeve of my white sweater. I wondered how many other people had seen it.

Cat winked at me. ‘We girls have to look out for each other,’ she said.

After the seminar, she asked if I was going anywhere for

lunch. I suspected she was stalling, based on the fact that the girl with the mullet was lingering in the doorway.

‘I don’t know,’ I said.

I had planned to go nowhere for lunch. I didn’t eat lunch; I couldn’t afford three meals every day, and lunch was the disposable one.

‘Do you like Greek food?’ she said. ‘There’s this Greek place I recommend to absolutely everyone; no one’s ever been disappointed.’

I’d woken up that day in the cheap room I was renting in a flat I’d found on Gumtree. By lunchtime I was eating a souvlaki next to Cat. I felt like I was still asleep and dreaming, but I refused to pinch myself. She talked for ages about everything and nothing. Most notably she also asked me about myself. She asked where I was from, and I told her I’d grown up two hours away by train. I didn’t mention that this was the furthest I could have moved for uni without my mother dying of stress.

‘Do you live in halls, then?’ asked Cat. ‘Or with friends?’

I laughed at this. Living in halls was the worst thing I could possibly imagine, but I wouldn’t call my flatmate a friend. That morning he’d crossed a line, and so I found myself spilling everything to the gorgeous stranger who’d bought me souvlaki.

Mason worked in a pub. He left dishes in the sink every night, and he didn’t own a Hoover or a mop. I stopped wearing white socks because within a few hours they’d be black underneath. I could have lived with that, but it wasn’t the worst of it.

Mason once asked me if I owned a vibrator and if that was what he’d heard from my room the night before. It was, of course, but I lied. I stopped masturbating because I didn’t

want him to hear it again. The morning I met Cat, he’d sat me down and told me he thought I should pay more of the electric bill because my showers were longer than his. Apparently he’d spent a week timing them.

When I told him I wouldn’t be doing that, he said there were other arrangements we could make. There were other ways I could make up my share of the bill. He winked at me. I wouldn’t have been as offended if he’d suggested I could sleep with him in exchange for the rent money, but just the electric bill? I was worth more than that.

I recounted all this to Cat. She stared at me with wide eyes and put her hand over her mouth. At the time I thought she was exaggerating, but I would come to realize she was probably being genuine. Something like that would never have happened to her. I’m not sure she’s ever been catcalled. Despite her striking looks and the way that she dressed, despite how men stared, she exuded something that made them keep their mouths shut.

‘I have a spare room,’ she said. Like she was a deity sent here to help me.

‘Are you looking for a flatmate?’

‘Not looking, exactly. My parents wanted to use it as a guest room when they come to visit, though I’d much rather have you there. They can stay in a hotel.’

I stared at her in astonishment. I’d never imagined having a spare bedroom that you didn’t need to use or rent out. I knew people existed who did, but it caught me off guard how casually Cat spoke about it. As if everyone could choose between a spare room and a flatmate that not so secretly wants to fuck you.

‘Your parents own the flat?’ I asked in disbelief.

I had heard about these mysterious students whose

parents could afford to purchase flats for their children, flats that would then go on to be rented out to others or simply stand empty until they felt like having a holiday in another city. Then they’d remember, oh, how convenient, don’t we own a property over there? Is anyone staying in it? Like housing was Tupperware you sometimes lent out.

‘Oh, no,’ Cat said. ‘I own the place. My parents just paid for it. Hold on, I think I have some pictures I could show you.’

I didn’t need to see the pictures to know that I would say yes. Of course I would. Fate was never this kind to me. I expected her to show me a box room with just enough space for a single bed and a desk. That would be more than enough if it came with the promise of not counting every second as I showered, if it meant living with this fairy-like creature with exposed collarbones, wearing so much jewellery she even had it in her hair.

It was not a box room. The room she showed me was larger than any lounge I’d ever had growing up. It was already fitted with a king-size bed and a wardrobe, and it had large bay windows with floor-length curtains.

‘Are you interested?’ Cat asked.

I knew there was no way I could afford to live with her.

‘How much do you want for it?’ I said.

‘You know, I hadn’t thought about that. Let’s check the average rent online.’

I stared at her as she typed it into the search bar, amazed that she could be so unaware of the world around her. The area name she typed in was one so expensive I never would have dreamed of living there.

‘My goodness,’ Cat said. ‘That’s quite a bit, isn’t it?’

The average for a single room in a shared flat was several hundred pounds beyond my budget.

‘Hmm.’ Cat looked at the screen and carefully applied some balm to her lips. ‘Well, I wouldn’t feel fair charging you that. It’s not as if I need the money. How about we do two hundred per month? Since we’ve been friends for two hours.’

I couldn’t believe my luck. I also couldn’t believe she already considered us friends.

Nearly nine months later, I woke up in that room the night after the party. Oliver was next to me in bed, stripped down to his boxers, with one of my pillows between us like a barrier. I was still wearing the dress Cat had lent me. The room was hot and the fabric stuck to my skin, my body slick with sweat from the thick duvet.

I thought of the place more as Cat’s than a flat we shared. The changes I’d made to my bedroom had been minor. The only signs that I lived here were the desk covered in sketchpads, the books on the bookshelf and the storage box I’d turned into a mouse cage. Perhaps I would have felt less like a house guest if I paid more rent.

I got out of bed and looked at myself in the full-length mirror. I hadn’t taken off my make-up the night before, and the products that Cat had so carefully applied to my face were now smeared across it. The mascara was creating dark circles around my eyes, the eyeshadow faded. There were marks on my white pillowcase. Oliver snored.

I checked on the mice in their cage. I couldn’t remember if I’d fed them before I collapsed. They were both awake. Pip was grooming herself on top of their nest, and Squeak was digging a hole in the bedding.

‘Hello, babies,’ I whispered.

Squeak immediately came running over towards me,

climbing up a branch and putting her nose to the mesh at the top of the cage. Squeak was sociable. She would always come towards me when I was near, and she would climb up my arm as soon as I put my hand in there. Run up and down my entire body trying to make it to the floor, and sit on my hip grooming herself. I was not fooled; there was no real affection there, I was nothing but a climbing frame to her. Pip, on the other hand, was cautious, suspicious. She didn’t take treats from my hand for the first few weeks, instead watching me. She rarely ventured up my sleeve, preferring to stay on ground level. But with her I felt loved. She groomed me sometimes, the bonding ritual mice perform on each other. Squeak never sat still long enough for me to touch her, but I could rub Pip’s face for several minutes and she’d sit there and enjoy it, her teeth grinding with contentment. She watched me now, as she always did.

I opened the cage and fed them, fending off Squeak’s attempts at escape, until she relented, grabbed a piece of food and retreated into one of the old toilet rolls I had thrown in there.

‘Guten Morgen,’ said Oliver, who was always learning a new language.

I turned around. He had got up on to his elbows and squinted sleepily at me.

‘Good morning,’ I said.

‘You look a fright.’

‘So do you,’ I replied.

He sank back on to the pillow with a hungover groan.

‘Get up,’ I said. ‘I need to go to the library.’

I walked him home on my way there, pushing my bicycle. His sunglasses covering his eyes, he went into a little

independent coffee shop near university and bought himself some coffee. We said goodbye outside his flat, and I hopped on my bike and rode down to the library to force myself to do some dissertation-related reading.

Campus was quiet this time of year, the period after exams but before the undergraduate graduations. People who have a reason to be elsewhere tend to leave university when they can. I was not one of those people. In the library I took the stairs up to the annex and went searching for a copy of the Groundwork. If you’re going to argue against Kant, it’s the only book you need to read; the arguments write themselves. Unlike the rest of the library, the annex wasn’t well organized. Books overflowed from the shelves and the signs that had once signalled where to go had long since peeled and faded. There were no windows in here, but the dim light from the ceiling lamps was just enough to help me make my way.

The old books were badly catalogued and many had no tags on the inside that would alert anyone if I grabbed one and went outside without checking it out. I ran my fingers along the spines, enjoying the changes in texture and the grooves where one book transitioned into another.

It only took me a few minutes to find a copy of the Groundwork. Pages came off in my hand when I opened it; I picked them up off the floor and matched the page numbers to the book to put them back in the right place.

The rest of the library was likely to be occupied, so I chose to stay in the annex and found myself a couch. Being around people is tiring. I’m always conscious of them, aware of every effort I have to put into standing up and walking around and the facial expressions I make. Not that I think everyone is staring at me, but they might be.

I read, and I remembered exactly why Cat called Kant

‘Cunt’. The sentences were so long, running on and on as if he thought commas and full stops were interchangeable. The language was archaic and convoluted. He wrote with far too much certainty about the way the world works for someone who had never left Königsberg.

When I’d had as much Kant as I could handle, I took out my sketchbook and drew his face as I pondered. Drawing had been the only thing that kept me sane in school. The sound of the pencil against the paper could bring my heart rate down to a normal level when other students were too loud, the lights too bright or the lessons too unpredictable. I gave my drawing of Kant far too much lip filler.

My phone rang. It was my mum. Of course it was; I had a therapy session on the coming Monday. She would need to make sure I hadn’t forgotten. I rolled my eyes. I had not forgotten, but I hadn’t planned to go, either. Now it would be impossible to pretend it had slipped my mind. Mum has always thought I’m much more scatterbrained and forgetful than I am. Every time there has been an event I didn’t want to attend, a job she wanted me to apply for that I wasn’t interested in, homework I had no intention of doing, I would tell her I forgot. It completely slipped my mind ; I just happened to miss the deadline ; god, what an idiot I am . . . Every Christmas she purchased a new calendar for me.

I let the phone go to voicemail anyway. Usually I would force myself to pick up once a week. That was about as much as I think she would be willing to accept in terms of me ignoring her. Not even a minute later her texts rolled in.

Just wanted to make sure you don’t forget therapy on Monday! You know how important it is, Louise.

Also, I’d really like to hear your voice, could we do a short phone call when you have time? Just a quick one.

I let out a deep sigh. There was no way to avoid either her or the therapy session.

Funnily enough, Mum was the reason I started studying philosophy. When I was little, she always called me philosophical. I was an inquisitive child, and I found a way to question everything. Why did I have to say thank you if someone did something nice? Why did I have to say it in a certain tone of voice for it to sound genuine? Why did she get to tell me what to do? She would laugh at me, sometimes amused and smiling. Sometimes bashful and blushing, throwing an awkward glance at the people around us. Sometimes exasperated, with her hands on her hips and a shake of the head.

‘You’re a little philosopher, aren’t you?’ she would tell me. When I asked her what a philosopher was, she couldn’t quite tell me. She hummed and mulled it over, started her explanation and stopped and started over again. Well, you see – It’s someone who –

When I was around nine, I took it upon myself to figure it out. I asked Mum to use our laptop, an ancient thing that took ages to start and which had to be turned off after an hour at most so it wouldn’t overheat. Mum kept it in a cupboard, so rarely did we actually use the thing. I placed it on the kitchen table and started googling philosophers. I came across all the classic old names of white Western men who thought they had the whole world figured out. All the internet was able to tell me was that a philosopher was someone who studied philosophy. So what was philosophy? It sent me down a rabbit hole I was still digging my way out of.

I came home in the evening and heard the piano as soon as I opened the door. It sounded beautiful. Light and airy,

like dancing in dewy grass holding hands with the fairies. I listened from the entrance hall for a little while. As soon as I bent down to take off my shoes and the wooden floor creaked beneath me, the piano went silent.

I had never seen Cat play. It seemed an inconsistency to me; Cat, so full of confidence, the life of every party, the loudest voice in any room, unwilling ever to play piano in front of me. I would hear her playing from my bedroom at night, when she assumed I was asleep, or I would be able to listen from the entry hall like this, if I had been silent enough in closing the front door. Everything was quiet now, and I imagined us both just waiting, still, like terrified little mice, neither of us moving a wink. Only a wall separating us from each other, both of us waiting for the other.

It had been nice to hear her playing. It meant Henry wasn’t there.

I took a deep breath and went into the lounge. Cat had cleaned up from the party, mostly. There was a large bin bag in the corner of the room, and she hadn’t wiped off the liquid rings from glasses on the coffee table.

‘You don’t need to stop for me,’ I said.

Cat was still sitting on the piano stool, with her back to me, but her head turned slightly in my direction. She had a soft smile on her face.

‘You know I don’t like it when people can hear,’ she said.

‘I don’t know why you care,’ I said. ‘You’re clearly good at this.’

‘Yes, but not when someone is listening. I never am.’ She slid to the side and patted the stool beside her. ‘Come, sit.’

Cat didn’t come to you; she told you to come to her. It didn’t matter to her whether you did or not. She didn’t need you to. You simply did what Cat said.