property of A PUFF I N BOOK

FEDERICO IVANIER

Translated by Claire Storey

A PUFF I N BOOK

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Puffin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published in Uruguay by Alfaguara as Martina Valiente 2004

First published in Great Britain by Puffin Books as Sword of Fire 2025 001

Text copyright © Federico Ivanier, 2025

Translation copyright © Claire Storey, 2025

The moral right of the author and translator has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 10 5/15.5pt Optima LT Pro Typeset by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978–0–241–68879–3

All correspondence to: Puffin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Joaco and Seba

Federico Ivanier is an acclaimed Uruguayan writer for young people. He has written over twenty books that have been published across Latin America. His works have been awarded the National Prize for Literature from the Uruguayan Ministry for Education and Culture, a Cuatrogatos Foundation Award, and the Premio Bartolomé Hidalgo, one of the country’s most important literary awards. As well as writing books, Federico works as a high school English language teacher.

Claire Storey translates from German, Spanish and Catalan into English, specializing in literature for young people. She has translated books from Uruguay, Argentina, Mexico, Spain, Germany and Austria. Claire regularly volunteers in schools talking about careers with languages and was named Outreach Champion 2021 by the UK Institute of Translation and Interpreting.

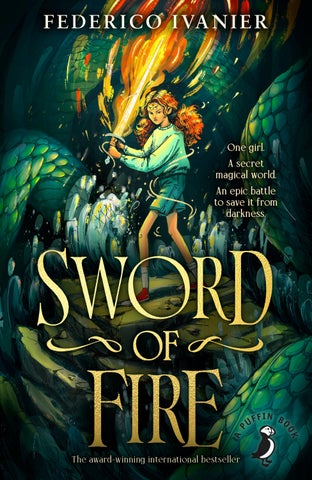

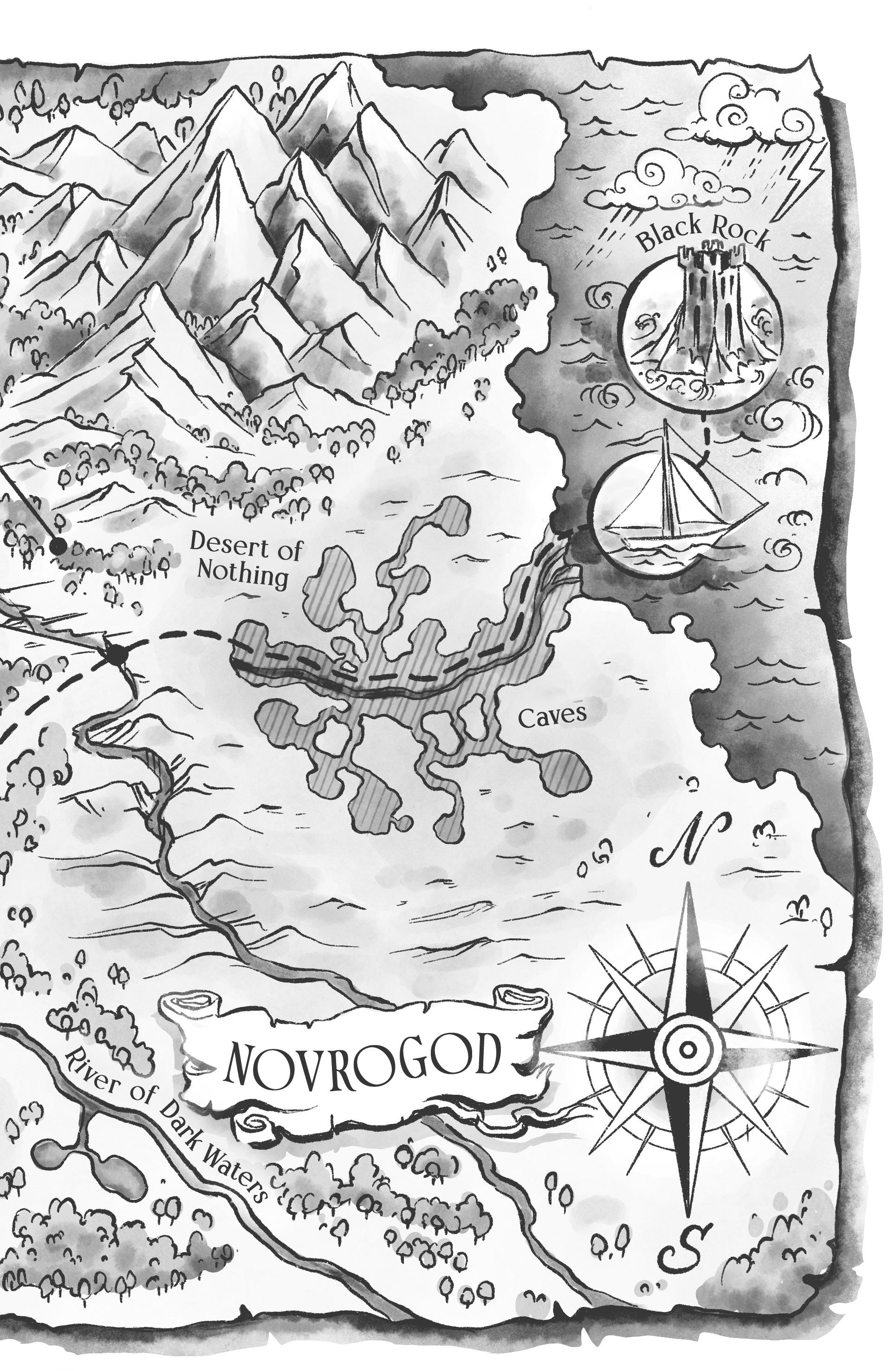

Novrogod. Wizardry. The Butterfly of Light. Martina had never heard of any of these before, let alone the Sword of Fire, a fiery blade that was said to burn even beneath water, turning everything it touched to ash. But even if she had been told about them, she would never have believed such things could be real. And yet – know it or not, like it or not, believe it or not – all that was about to change . . .

One

The Wanderer in the Darkness

The Wanderer in the Darkness descended through the air, held up by invisible strings. Although his black cloak melted into the shadows, Martina could still see him. His long-fingered hands, a pale and sickly white, shone like a ghost. Even though she couldn’t see his eyes, Martina knew he was looking at her. Her heart was pounding.

The Wanderer in the Darkness. She had given him that name the first time she had seen him. He carried a wooden staff as tall as he was, topped with a sphere, and he used it to dominate the world. Martina didn’t know where she’d got that idea from, but she was certain it was true. Just as she was convinced that he was looking for her, that he had been from the very beginning, each and every night, from dream to dream. He was waiting for her. Sooner or later she would have to face him. She thought hard, imagining she could fly, and – whoosh – her feet simply lifted off the ground until they were face-to-face.

‘Martina . . .!’

A flash of lighting cut through the darkness. Hands rested on her shoulders.

‘Martina . . .!’

She opened her eyes.

Her mum was watching her, dressed in a yellow shirt, her hair swept into a messy ponytail.

‘Martina, wake up!’

Martina glanced around the room, her bedroom. Her new bedroom. It felt different to her old one, but this was home now. Or at least it had been for the last couple of days. Martina squinted, dazzled by the light.

‘All right, Mum. I’m awake.’

‘You were rolling around and sleeptalking. What were you dreaming about?’

‘I don’t know. I can’t remember.’

She’d never told her mum about the Wanderer in the Darkness. Not once. She’d always had these nightmares, ever since she could first remember. She didn’t know where they came from, and she’d never mentioned them to anyone. Talking about them, even in the daylight, sent a shiver down her spine.

Her mother sighed, then said, ‘Do you want a glass of water or anything?’

‘No, nothing. I’m fine.’

‘Are you sure? You’re all clammy.’

‘Yeah, I’m fine.’

Her mum gave her a calming smile. Over the last three months, what with the divorce and the house move,

her mum’s face had become lined with small wrinkles. She tried hard to pretend these furrows didn’t exist, but Martina could still see them, perfectly so, even though they were never talked about. Just like the nightmares.

‘It’ll all be all right, you know?’ her mum said with a smile. ‘The new house, the new neighbourhood, all these changes. It’ll all be fine. You’ll see.’

‘Yes, Mum.’

‘Your new school will be great, and you’ll get to know lots of new people. And you’ll get used to seeing your dad a little less, and –’ she looked up, as if looking at the house – ‘Basically, you’ll just get used to everything.’

‘Yes, Mum.’

‘You’re much stronger than you think.’

Martina smiled, more to make her mother happy than anything else. So far she hadn’t made any new friends, and she hadn’t got used to seeing any less of her father. In her humble opinion, things were not going well.

‘Right, well, I’ll leave the light on. If you need anything, give me a shout.’

‘Mm-hmm.’

‘Relax and try to sleep.’

‘OK.’

Her mother left the room and Martina was alone again. She wasn’t sleepy any more and she didn’t feel like reading. She climbed out of bed, stood next to the window and opened it. Outside, there was a pleasant breeze, the dark sky was full of stars and the moon looked like a white cat curled up asleep in the sky. Martina took

a deep breath, inhaling the scent of the night, and leaned against the windowsill.

It had only been two days since they had first set foot in Grandma Famke’s flat in Montevideo, but it felt like a lot longer. They had opened the door on that hot, sticky day at the end of January and Martina had peered inside. Before anything else, a smell of confinement had filled her nose. The house beyond was dark, and the dust floating in the air had been illuminated by the sunlight pouring in through the open door. She had simply stood there, her shadow cutting into the rectangle of light falling on to the pale, worn parquet flooring, a long and slightly scrawny outline, her curly hair falling to her shoulders.

Having just turned twelve, Martina Adler wasn’t much to look at, or so she thought. Narrow shoulders, a slim neck, red hair (unbrushable), her face covered with freckles (as was the rest of her) and a slender body. Her legs were slim, too, and when viewed as shadows they looked like two slender poles. Sometimes Martina worried about her weight; she was the skinniest of all her classmates. Well, her old classmates, at least: Gabriela, Magdalena, Mariana, Stefanía.

Martina and her mum had moved to the district of Buceo on the other side of Montevideo, an hour away from where her friends all still lived in Prado. Before, it had only taken her five minutes on her bike to go and see them. Now it would take her ages. And all because her parents were getting divorced. Her dad had gone off to

live with an accountant called Silvia who had a fourteenyear-old son called Matías and a thirteen-year-old daughter called Nicole. Her mum had decided she didn’t want to stay in their old house on Buschental Road any more, so there they were, in Grandma Famke’s old house in Buceo.

Mysterious Grandma Famke . . . She had died before Martina was born and had come to Uruguay from Europe, fleeing the Second World War. Martina knew why she had fled, but not exactly where Grandma Famke had come from – somewhere in Europe, that’s all she knew. At the end of the war all that had remained of her village was rubble. Everything had been destroyed.

Martina’s first impressions of her new home had been depressing. The house had been full of dust and the sofas were covered in cloths that might once have been white. The living room was large, but it had only added to her bad impression of the place. The paint had been flaking off the walls and mould had spread like a faint bruise in the corners of the room.

But the thing that had caught Martina’s attention the most that first day was the mirror. It was huge, with an ornately carved frame. That must be really valuable, she’d thought. Its polished surface had been covered in dust, like everything else, and it had been difficult to see anything in it. Martina’s own reflection appeared like a ghost wearing red shorts, a black T-shirt with a smiling sun and moon overlapping above a ‘No Te Va Gustar’ sign – one of her favourite Uruguayan rock bands – and simple sandals. For

a second, it had startled her that she didn’t completely recognize her face. Perhaps the lights in the house – or the shadows – were playing tricks on her. Or was it the mirror? Most likely, it was how fast she was changing: the child she’d once been was beginning to disappear.

‘Is this really where we’re going to live?’ she had asked.

‘Yes, Martina. Right here,’ her mother had replied.

‘But we can’t live here.’

Her mother, Ariana, was a translator of French and English for the Libyan Embassy. She had placed her own freckly arm round her daughter’s shoulders and sighed, looking about.

‘That’s what this place wants us to think, isn’t it?’

Cobwebs had hung from the ceilings and the whole place reeked of melancholy; it was difficult to think it wanted anything. But even so, the thought had made her mum smile.

‘But we won’t let it fool us!’ she’d added.

Then she had flung open the windows. Light and fresh air had filled the rooms, welcome guests that had been absent for many years.

That night Martina had handed responsibility over to some greater force, trusting that the roof wouldn’t come crashing down on them as they slept. It had seemed the place might just fall apart like a giant house of cards, but it had stayed standing. The wooden staircase leading to the upstairs had not fallen through and Martina had chosen one of the three bedrooms on the upper floor to be hers. The window offered a splendid view of the sky.

Over the next few days, carpenters, builders, plumbers and a painter had come in, and huge bags of rubble had gone out. The Wanderer in the Darkness seemed to have followed her there, invading her dreams, true, but he couldn’t stop them from doing up the house. That felt good. And he certainly couldn’t stop Martina from exploring the house. Or exploring its contents. That also felt unexpectedly pleasant, even homely. During the afternoon after the nightmare, on the third day in the house, Martina found several old toys that were beyond salvation, as well as some other bits and pieces that she was unable to make neither head nor tail of. They were in the wardrobe in Martina’s room and she hadn’t liked any of it, so she had planned to throw it all out.

‘We’re not getting rid of all these toys!’ her mother had exclaimed. ‘Some of them could still be useful.’

‘Useful for what? They’re broken,’ Martina had replied. She had known she had a point – and her mum had known that too.

‘Some of them . . . I don’t know, remind me of things . . . But you are right.’

‘Besides, they’re really ugly,’ Martina had continued, holding up a doll wearing a musty outfit. ‘This one’s definitely going.’

At the time of the conversation, Martina’s bedroom had been half painted and a ladder had leaned against a wall covered with white splodges of wall filler.

‘Mum, what’s this?’ Martina had asked.

She had been holding up a golden metal cube. It was covered in dirt, but beneath the grime it had gleamed.

‘Where did you find it?’ her mum had asked, looking at it. It was fairly heavy and cold to the touch.

‘In there,’ Martina had said, pointing to the wardrobe.

‘To be honest, I don’t remember that at all.’

‘What’s it for?’

‘I don’t know. People used to display photos in cubes.’

‘What do you mean by in cubes?’

‘Not like this metal one – they were made of plastic. You inserted a photo in a slot on each face, so there were six photos in all, one on each side.’

‘People used cubes instead of photo albums?’

‘Many still do, as far as I know.’

‘I’ve never seen one. Ever.’

Her mum had smiled, looking thoughtfully at the cube. Her image was reflected on the surface, a somewhat distorted version of herself.

‘They’re like frames, but they hold several photos at the same time. People leave them out on sideboards or shelves.’

‘Oh,’ Martina had murmured, and picked up the cube again. She’d wiped the dirt off one of the sides and looked at herself. The face of a freckly redhead had looked back at her. The cube had seemed like a nice knick-knack, though. ‘Can I keep it?’

‘Of course,’ her mum had said as she ran her fingers through Martina’s hair. ‘I don’t see why not. Finally, something you don’t want to throw away! Do you like it?’

‘Yeah . . . I dunno, it’s strange. I have no idea what it’s for, but I like it as a trinket. I could even stick some pictures to it.’

‘You’re going to damage it if you cover it in stickers –’ ‘Muuum!’

Martina had looked at her mum and seen her laugh, her head thrown back, the way she used to. Martina had inwardly thanked the golden cube and became even more certain that it should live next to her bed.

She’d also found a bedside table that she wanted. It was an old wooden one with curved edges and grapes carved into the door. Since then, Martina had sanded it down to remove the damp and given it a couple of coats of varnish, and now it looked like new. It even smelled good. They’d also found an old metal lamp in the shape of a candle. It didn’t work, but they’d sent it off to be fixed, bought a lampshade for it and ta-daa!

Martina had chosen the colours for her bedroom and the curtains, too. Once everything had come together the room became fresh and bright, and she had begun to fill the walls with posters. She had one of the album De Bichos y Flores by rock band La Vela Puerca, and another of the film Rock of Ages. Her dad had got her that one the last time he went to Los Angeles, and even though Martina had never actually seen the film, she still liked the poster.

After five days of hard work Martina’s room had felt much more orderly, which secretly made her very happy. At night, she had no dreams of the Wanderer in the

Darkness – at least, she hadn’t for the last few days. She didn’t even think much about it. She slept facing the new bedside table on which sat the lamp and the mysterious golden cube that had put her mum in such a good mood.

Two Riddles and misunderstandings

‘What?’ asked Nicole. Her cutting tone came naturally; there was no need to pretend. At thirteen, Nicole was the queen of contempt. ‘Why does she get to have that room?’

She, in that particular conversation, was Martina, who was due to visit later on. And that room was the attic in their house. Nicole, her brother, their mum and Martina’s dad were eating dinner while seated round the wooden table in the kitchen.

‘Because nobody’s using it,’ answered Matías, as he stood up and went over to the fridge.

Matías was Nicole’s older brother, but he lacked the contempt of his sister. He spoke in a much calmer, flatter tone of voice. He carried a jug of water back to the table and sat down. He walked easily; his skin was lightly tanned from the sun and his quiet green eyes moved slowly. He was relatively tall for his age, with solid, wellset shoulders.

‘I mean, it’s not even a room,’ Matías added. ‘It’s an attic.’

‘It is a room. I use it to store all my old stuff.’

‘What stuff?’

‘Clothes, magazines, stuff. Where am I going to put it all now?’

‘How about in your bedroom?’

‘Oh really? Would you like to tell me where?’

‘Oh no! You’re gonna have to throw some stuff out. How awful.’

Nicole glared at her brother over the table.

‘Mu-um . . .’ she whined.

‘Kids, kids,’ Silvia intervened. ‘We’re just trying to find a solution. That’s all.’

‘I need that room!’ insisted Nicole.

‘Great, perfect,’ said Matías. ‘That’s all sorted then. You keep the attic and Martina can sleep with you in your bedroom.’

‘My bedroom?’

Matías sighed, worn out by the conversation. However, the decision was quickly made. For now, anyway, Martina would have the attic when she stayed with them on the weekends.

Silvia spoke to her daughter. ‘We all have to make some sacrifices. Martina is our guest, and –’

‘Well, really, if this is her dad’s house then she’s not actually a guest, is she?’ interrupted Matías. ‘Doesn’t that make it her house too?’

Matías didn’t wait for an answer and instead moved straight on to a different topic of conversation.