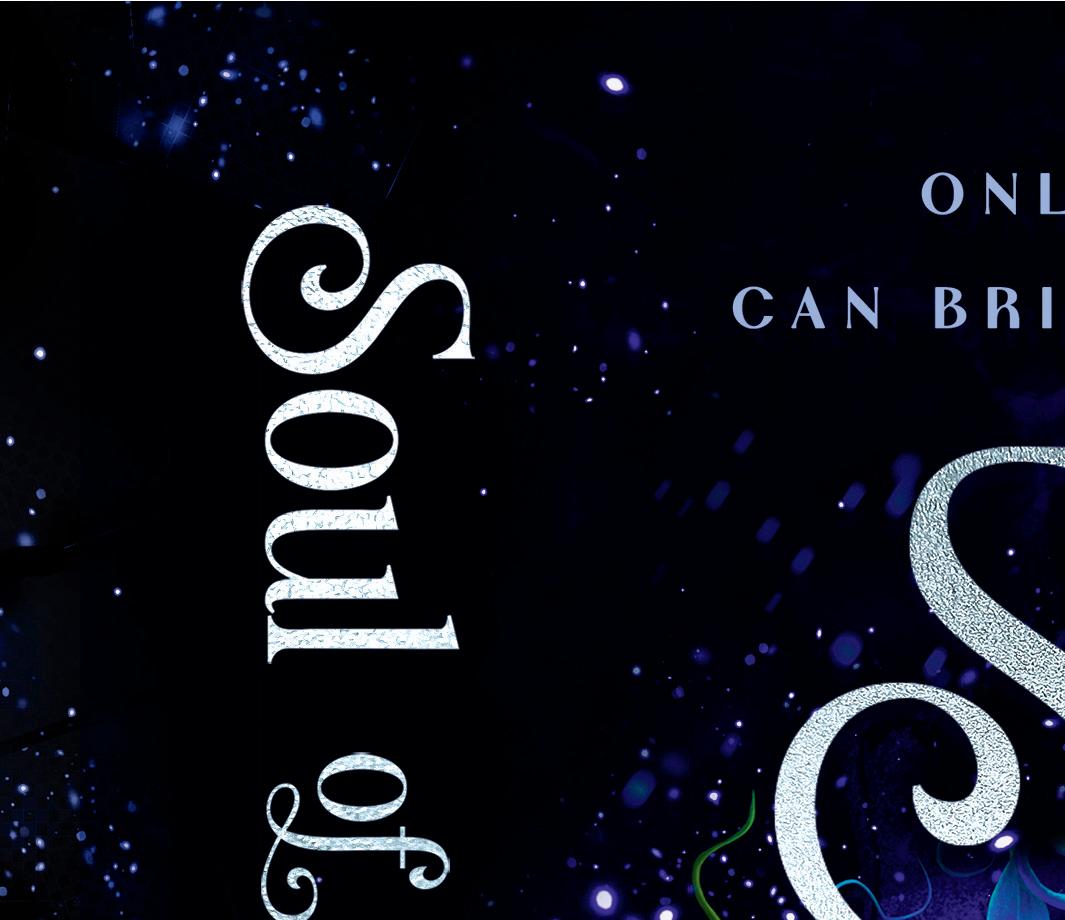

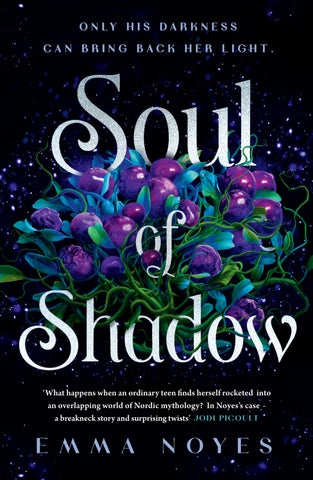

‘What happens when an ordinary teen nds herself rocketed into an overlapping world of Nordic mythology? In Noyes’s case –a breakneck story and surprising twists’ Jodi Picoult

‘What happens when an ordinary teen nds herself rocketed into an overlapping world of Nordic mythology? In Noyes’s case –a breakneck story and surprising twists’ Jodi Picoult

Also by Emma Noyes

The Sunken

The Fallen Witch

How to Hide in Plain Sight

PENGUIN MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America by Wednesday Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Publishing Group 2025

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Michael Joseph 2025 001

Copyright © Emma Noyes LLC , 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Designed by Devan Norman

Wolf case stamp image © Peratek/Shutterstock Botanical endpaper pattern © Lisla/Shutterstock Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library HARDBACK ISBN : 978–0–241–68387–3 TRADE PAPERBACK ISBN : 978–0–241–68388–0

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

When this life is over, I’ll find you in the next .

His shoes were found during the bonfire.

They were hanging from an ash tree, a pair of bright-white Adidas roped together by their bright-white laces. They were easy to spot, a patch of white among a crown of darkgreen leaves. Were it any other night, the group of freshmen might not have even noticed. But it wasn’t any other night; it was the night after Robbie Carpenter had been officially pronounced missing.

The nimblest freshman scaled the tree and plucked the shoes from their branch. As soon as he hit the ground, he and his friends started to run.

Charlie Hudson watched the bonfire, feeling not even the least bit excited about junior year.

As she looked around at the party unfurling before her— the star-speckled sky; the plastic beer pong table stuck into the sand; the kids falling into little cliques in the crowd based on grade or social group; the gentle waves of Lake Michigan lapping against it all— she didn’t feel what she was supposed to feel. What the rest of her friends surely felt.

The back-to-school bonfire was a rite of passage for Silver Shores High School students. Every year, on the Saturday before classes began, they showed up at the beach with a halfdozen kegs of beer and enough vodka to drown a man in the desert. And every year, they got at least a few hours of partying in before the sheriff showed up.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

Everyone there—kids that Charlie had grown up with, now at a time in their lives where they were not quite children but not quite adults— gathered around the bonfire, excited. They chattered loudly about which classes they were taking, how they expected the football team to perform this year, who was hooking up with whom. It was all infused with a sense of wonder, as if they stood at the precipice of possibility.

This year it felt different. Off. Some of the conversations were hushed, careful. Charlie heard words like clues and investigation and kidnapping thrown in with the usual chatter. One of their own was missing, and no one knew how to handle it.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

At the far northern end of the beach stood the tall, rusty fence covered in signs that said things like do not enter and beware. At the end of the fence, where the sand met the water, chain-link gave way to a tall, thick pier made of rocks and metal. During previous back-to-school bonfires, one or two people got too drunk and tried to climb up onto the pier, but no one— not a soul— ever touched the fence. It was an unwritten rule in Silver Shores. An homage to the dozens of people who lost their lives during the accident at the Oxford Power Plant.

Still, the overall atmosphere that night was one of celebration, not mourning. Everyone seemed festive.

Everyone but Charlie.

She had nothing against junior year in particular. It wasn’t

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

that this year, of all sixteen years that she had lived to that point, would be considerably worse than any of the ones that preceded it. It was more of an ever-pervasive feeling. A thin sheet of grime that covered every inch of her otherwise normal existence.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating disappearances.”

Reality didn’t suit Charlie. She loathed its repetitive days, the constant feeling of running through mud. She often came to this beach on her own and sat down atop the dunes. Closed her eyes. Felt the saltless wind on her face, the tickle of reed grass on her calves. These were her feeble attempts to break the rhythm of her life. To feel something new, anything at all.

She knew she should be more grateful. That she had a good life, good friends, a steady family, spare cash when she needed it. But she could never shake the feeling that something was missing. Some key fragment of her soul.

It had been that way since she’d lost Sophie.

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

Sophie had been Charlie’s identical twin sister. They’d had the same dark hair, the same thick eyebrows, the same blue eyes—light on the inner ring and darker on the outer—the same smattering of freckles across their nose and cheeks. Sophie had been her shadow. Her second half.

Until, late one night the first week of freshman year, she wasn’t anymore.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect calf.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

Charlie didn’t like to look too closely at her emotions. She didn’t like to acknowledge the voice whispering at the back of her mind, the darkness bubbling just below the surface. Sometimes she thought she could feel it, as if it were a creature living within her. She imagined it as a jumbled mass of pulsing, multicolored threads, wound too tight to ever untangle.

She sighed, pulling herself out of her thoughts, and rejoined the conversation her two best friends were having. The three of

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

Noyes

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

them were seated on a lopsided piece of driftwood, their feet stuck into the cool sand, a pleasant contrast from the fire roaring a few dozen paces away.

“I’m not telling you to join the student council,” Abigail declared from her place on the tallest part of the driftwood. She sat with her arms and legs folded, a can of Busch Light in one hand. “I’m just saying that another extracurricular would look good on your resume.”

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

“And I’m telling you,” Lou said, crushing her empty can with one hand before tossing it into the black trash bag hung up on a log a few feet away, “that swim team already takes up too much of my time as it is.”

Being around her friends was good for her. It drew her out of her mind. Let her think and feel and be something that she couldn’t be on her own. Let her forget, however temporarily, the shadows that lingered.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

“But we have college to think of.” Abigail leaned forward, one dark, delicate hand resting atop her black jeans. “Showing devotion to a particular sport is good, but having a wide breadth of interests is just as important.”

Lou tapped one finger on her freckled chin. “Does being able to shotgun three beers in a row count as an interest?”

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

Charlie stifled a snort, then tuned out the conversation again. It was the same one she had heard a hundred times this summer: Abigail stressing over college admissions, and Lou doing her best to drive Abigail insane with how little she cared. She often wished she were more like them. More normal. Less locked in her own mind. But she wasn’t.

Her eyes wandered the moon-streaked sand around them. This beach was the largest and most popular strip of sandy lake-

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

front in Silver Shores. Despite being located in Michigan, Silver Shores was a beach town. A beach town that froze into a spectacle of blistering snow and purple ice in the winter, but a beach town nonetheless.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

The sand was cool between Charlie’s toes. The bonfire burned wild and hot. Laughter and bright orange sparks danced up into the sky. Lake Michigan was like the smooth surface of a diamond, broken only by the occasional ripple caused by the drunken sophomores who had decided it was a good idea to take out a canoe. Charlie shook her head as she watched them paddle sloppily across the horizon. Silver Shores didn’t need any more disappearances this week.

The party on the beach— an illegal bonfire surrounded by even more illegal drugs and alcohol—was an obvious and flagrant violation of local law. Not that anyone in attendance cared.

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

The person who cared perhaps least of all was Mason Hudson, Charlie’s older brother. She could just make out Mason’s face from between all the leaping flames. He was splitting a joint with a girl Charlie thought might be one of his many ex-girlfriends.

Though they were only a year apart, Charlie wasn’t close with Mason. Not anymore. Once upon a time, they’d been thick as thieves. Mason was annoyingly mischievous, always pulling pranks on his sisters: leaving buckets of water atop their bedroom door, putting lizards in their desk drawers, replacing their shampoo with purple hair dye. Charlie spent most of her childhood yelling at her older brother, but she secretly reveled in his attention. Sophie and she both did.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

Charlie cut off that train of thought before it could go any further.

She went back to studying Mason and his ex-girlfriend

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

through the flames. What was her name? Katie? Michelle? She had a vague memory of walking in on them making out on the couch over a year ago. Was it Susanne? Or—

That was when she heard the first yell.

It was quiet, distant. Someone way back in the woods.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

“— and the admissions committee considers everything on your application,” Abigail was saying loudly to Lou, long braids swishing animatedly down her back. “In fact, seventy-five percent of schools—”

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

“Shhh.” Charlie put a hand on Abigail’s shoulder. “Do you hear that?”

“Hear what?” Abigail asked.

“I hear it.” Lou pulled a twig from the sand and tossed it toward the bonfire, missing by a few feet. “It’s the sweet, sweet sound of Abigail finally ceasing to nag me. Well done, Charles.”

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

Lou knew that Charlie’s real name was Charlotte. But that didn’t seem to matter—just as it didn’t matter that her own real name was Louise. Charlie couldn’t think of a single person who referred to Lou with her given name, except maybe the occasional substitute teacher.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

“That’s not what I meant,” Charlie said. “Listen— do you hear that yelling?”

All three girls fell silent. They quirked their ears up toward the sky.

It didn’t take long. The yells grew in volume and quantity, multiplying into what sounded like a pack of teenagers running through the forest, calling loudly into the night.

“What the—” Lou stood from the log, turning to face the trees.

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

Moments later, a group of boys burst out into the clearing. One was waving a pair of white shoes over his head.

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

“We found them!” the boy with the shoes yelled. “We found Robbie’s sneakers hanging from a tree!”

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

The partygoers erupted. Whispering or loudly arguing about what the discovery of Robbie’s shoes meant to the investigation. Many thought he was dead. Others thought he’d been kidnapped. No matter the theory, everyone was excited by the prospect of new evidence.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

On the other side of the fire, Mason leapt to his feet. He looked thrilled as he took off toward the freshmen.

“Wait.” Lou turned to Abigail and Charlie. “They found his shoes ? And nothing else?”

“Did you get a closer look at the tree?” Mason yelled from across the fire. “Search it for other clues?”

Charlie kept herself from rolling her eyes. Always eager for trouble, her older brother.

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

“No,” said the freshman. “We just grabbed the shoes and dipped.”

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

“It’s about a hundred feet in,” said one of the other freshmen. “The old ash beside that one big cluster of rocks.”

“Great.” Mason snatched the shoes out of the lead freshman’s hands.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

“Hey!” the freshman said, trying to grab for them.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

Mason held them just out of the freshman’s reach, waving them in the air. “Looks like it’s time for a little field trip, kids.”

A cheer rose from the crowd. Then the students of Silver Shores High took off, Mason in the lead, and stormed over the beach, toward the tree line. They surged into the forest as one.

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

“Excellent.” Lou rubbed her hands together. “Some excitement at last.”

Charlie stood, her chest fluttering unexpectedly at the prospect of following them into the woods. What was that feeling? Fear? She wasn’t sure. It was an unfamiliar sensation, like something long dormant was awakening within her. As a reflex, she reached around herself and touched her back pocket, checking to make sure her lucky deck of cards was still in place.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

“No way.” Abigail crossed her arms over her chest, staying firmly seated on the driftwood. “Nuh-uh. This is a disaster waiting to happen. I refuse to be arrested at sixteen.”

“You’re already drinking alcohol at an underage party,” Lou pointed out.

Abigail’s eyes widened. “Christ,” she said. “You’re right. I shouldn’t even be here. I should never have let you convince me to come. I—”

Lou reached down and yanked Abigail to her feet. She pushed her friend toward the tree line. “Shut up and run.”

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying building a fire.

The girls hurried after the rest of the party. Lou took Charlie’s and Abigail’s arms, linking them with hers and skipping forward as if they were off on a picnic, not to investigate a potential crime scene.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

“This is messed up,” Abigail whispered loudly. “We’re caravanning to see if we can find Robbie Carpenter’s body.”

Charlie had to agree. It was messed up. In all likelihood, Robbie’s mother was curled up on the sofa at home, sobbing, while a bunch of kids made investigating a potential piece of evidence into a party game. No doubt Robbie’s father, the local sheriff, would want to lock someone up for what was happening right now. And yet Charlie couldn’t bring herself to turn

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

around. To tell herself to stop. Her feet propelled her into the woods as surely as if attached to a motor.

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

She glanced to the side. Through the trees, she saw a few other kids running forward, bare feet getting caught in roots and sand and dirt. Their path was lit by an unusually bright moon. It filtered through the oaks and pines whose branches tangled high above, lush and deep green and swollen with summer.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

Her eyes had just begun to turn forward again when she saw it.

It was only a flash. An outline set against the moonlit trees, as brief and blurred as the blink of an eye. A deer, or large dog, or maybe even a panther, standing stock-still, partially concealed by the brush, watching them sprinting through the woods. Dark silhouette. Glimmering eyes.

Charlie twisted her body, trying to get a better look. For a brief moment, its eyes seemed to lock with hers. As if it were staring at her, too.

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

Then she tripped over a thick root.

“Je -sus!” Lou’s arm slipped out of Charlie’s elbow as Charlie flew forward, the wind knocking from her chest as she hit the forest floor.

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

“Charlie!” Abigail whirled around and ran to her friend’s side. “Are you all right?”

Charlie blinked rapidly, trying to clear her vision of the stars that danced so eagerly about its periphery. She groaned and rolled over onto her back, pressing a hand to her chest. It throbbed where it had collided with the ground. “Yeah.” She blinked several more times. “Yeah, I’m fine. Jesus, that hurt.”

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

“Good.” Lou bent over and wrapped a hand around Charlie’s forearm, hauling her up to her feet. “Because it sounds like they found the tree, and I’m not missing this unless you’re dying.”

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

“Nice of you to show some empathy,” Abigail said as she tripped along behind them.

Charlie didn’t dwell on her best friend’s typical lack of concern. Her thoughts were too consumed by what she had seen hiding in the woods. What was that thing? An oversized animal? A wildcat that had strayed too near civilization? It would be a bizarre sighting if so. Wildcats normally ran as far from humans as they could. Not only had it not run, whatever it was had stared right at Charlie, as if it were the one challenging her.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

“Over here!” Lou tugged her friends toward a clearing.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

The stars faded from Charlie’s vision, allowing her to see exactly where they were headed. She recognized it immediately: the old ash tree where she, Lou, and Sophie played when they were little girls. A place they had brought dolls and journals, built houses from sticks, dressed as pirates or zombies. It was a place of boundless imagination, back when Charlie had still dared to dream.

A deep desire rushed through her: to run full speed at the tree and leap as high as she could.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

But that would be impossible. The clearing was completely full. People clustered together around the trunk, squinting into the moonlight, which only partially illuminated the tree. It wasn’t enough light. One by one, they lit their phone flashlights and pointed them up at the tree. The combined effect was that of a single spotlight shining bright and revealing into the darkness.

For several seconds, no one spoke.

Mason was the first to break the silence.

“Holy shit.”

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

By the following morning, the whole town had seen the tree. Those at the bonfire took photos of what they found, sending them to friends or showing them to their parents once they got home. At first light, around five a.m., the local news van arrived. Video footage of the tree was pumped into every home in Silver Shores, close-ups and wide-angles that caught every leaf, every inch of bark.

The tree was no longer just a tree.

Its trunk was entirely carved up, riddled with symbols: slashes; arrows; waving lines; a circle with an X inside, almost like a compass; a crude impression of a bird. The police were brought onto news broadcasts, queried as to what they thought the symbols might mean. No one could make any sense of them.

But the biggest symbol, the one that stuck out from all the others, carved huge and deep at the very center of the trunk, was this:

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

The broadcasters spent most of the morning debating what they thought the tree might mean. Was it a ransom note? A map leading to Robbie’s location? Pure gibberish?

It was only when a local resident, a young man particularly fond of Viking-themed video games, phoned in to the news station that they figured out that the symbols— some of them, at least—were Old Norse. Some light googling at the news station revealed the meanings of a few of the symbols, but many remained a complete mystery, as if the carver had just made them up.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

The meaning of the biggest symbol, however— that of the three interlocking triangles—was clear as day. It was known as Odin’s Knot, a common inscription found throughout the history of the Vikings. It had several meanings, but there was one that was most common.

Death.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

The morning after the party, Charlie sat in the library and watched magicians catch bullets in their mouths.

Charlie had always loved magic.

She loved everything about it. The weight of the cards. The swish of the cups as she switched the ball, unseen by the audience. She loved the complexity of it, the web of lies and misdirection. The wonder in the other person’s eyes when the cards did something impossible, or the handkerchief appeared somewhere it couldn’t be. The subtle dexterity, the sleight of hand.

She loved it so much that she had once imagined making a career out of it.

The morning after they found the tree, Charlie made herself a bowl of cereal and carried it upstairs to her favorite room in the house: the library. It was a small space, the walls entirely covered in old novels, dictionaries, and encyclopedias. Charlie wasn’t much of a reader— she preferred scrolling YouTube videos on close-up magic— but she often sat in there just for the ambiance. For the plush carpet on the floor and the worn red armchair perched beside the bay windows.

Charlie’s mother put her children into circus classes when they

Noyes

were just toddlers. They dabbled in a little bit of everything— flexing their muscles, loosening their joints, learning to fly high and be fearless. They tried trapeze and floor acrobatics, silks and hoop, close-up magic for the audience. It was the prerogative of circus athletes to have a wide range of skills. But they each had their favorite.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

For Mason, it was the trapeze. For Sophie and Charlie, it was anything they could do as the Incredible Twosome: identical twins with identically impressive skills. On stage, there was no difference between Charlie and her sister. There was no quiet one, no loud one, no adventurous and shy, no extrovert and introvert. None of the things that usually differentiated twins. Together, in the circus, they moved as one.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

And they were good. Exceptional, really. All three of them—in grade school, they were invited to join the junior traveling troupe that put on shows all around Michigan. It took up most of their free time, and the kids at school didn’t get it. They thought the Hudson kids were strange for doing circus instead of soccer or basketball or even gymnastics. In their minds, circus was clowns and monkeys and bearded women—not brave, athletic children.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

Within their grade, there was one girl who didn’t find Charlie and Sophie strange. Who loved to watch them perform, even egging them on to do stunts during recess. Her name was Louise, but she preferred to be called Lou. She quickly became the twins’ best friend.

Mason was the first to drop out of the troupe. When he turned eleven, he decided that the circus was no longer “cool.” That he would rather do a mainstream sport, like baseball or football. Though he had no experience in any of the sports, every team was excited to have him. Growing up in the circus

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

had left him remarkably strong. As it turned out, his skills best transferred to baseball, where his swing was the hardest. He joined the local league, and that was the end of his circus career.

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

Charlie and Sophie kept going. By age ten, they had already cemented their place within the troupe. They were the wonder twins, those fearless girls who would backflip in sync, dive from great heights, and bend each other into impossible shapes, all for the sake of the audience’s delight. They even developed a two-person magic routine, assisting each other in card tricks or letting one saw the other in half. They were unstoppable.

Or, at least, Charlie had thought they were.

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

She didn’t remember her twin’s death. She remembered the illness. Remembered her sister’s fever, of little concern at first but never seeming to break. Remembered her mother waking her very suddenly in the night and saying they needed to go now, her and Mason both— Get your coats and get in the car. She remembered the pale-white light of the emergency room, the doctor’s voices, frantic when they arrived but later hushed, secretive. She had been told that she was in the room when it happened. When the machine’s pulsing line went flat. But she couldn’t remember. And what’s more, she didn’t want to.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

Bacterial meningitis. Those were the words she heard that night, words that would be repeated for weeks afterward. Words that still sometimes woke her in the middle of the night, echoing in her ears as if someone had just whispered them moments before.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

When her sister died, so did Charlie’s love of the circus.

She only cried for one day after her sister’s death. One day of excruciating pain, of feeling as if her insides were being ripped out and thrown across the room, stomped on, squeezed, forced

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

Noyes

the madness of the chase and almost hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

back in— only to repeat the process all over again. One day of heaving sobs, of feeling as if she could never get enough oxygen. Her grief made the day feel endless. It dragged on and on, a never-ending cycle of burning eyes and knives in her stomach. When she woke up the next morning, she thought, No more. She couldn’t live like this. She would not crumble beneath the pain. She would become, as she dubbed it, a master of distraction. The distraction could be anything. It could be a movie night with Lou, taking herself out for a run through Silver Shores, learning to cook, reading about the Civil War in her history textbook— anything. Anything that absorbed her attention. Anything that made her forget, however briefly, the absence of her twin sister.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

She tried returning to the circus, too. But when she finally made it back into the gymnasium, nothing felt right. Her routines were all meant for two people. She was supposed to be a base or a flyer or a partner, one half of a whole. She felt weakened, incapable of hoisting herself up the trapeze or even holding a handstand. All she could do— the only thing for which she had any energy—was magic.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

It was magic that saved her. Magic that pulled her through her grief, through the heavy, gray cloud that hung over her home, the schoolyard, everywhere she went. At night, when she couldn’t sleep, she stayed up reading forums on sleight of hand or watching step-by-step videos of magicians teaching their most difficult tricks. She bought a brand-new set of cards. Practiced with them until her hands bled. For Charlie, magic was no longer about mystery and wonder. It was a tool to be perfected. A sword to be sharpened. Something that absorbed her attention, that yanked her from the misery of her own body. Her method wasn’t bulletproof. Grief still found ways to

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

wiggle to the surface, most often in the long moments when she found herself zoning out, replaying old memories on a torturous loop until she could redirect her thoughts. She cried, too, but only sporadically and never in relation to her sister’s death. She watched a documentary about migrating penguins, and she cried. She saw a squirrel run up a tree, leaving its baby behind, and she cried. She read a book where a couple defies all odds and ends up living happily ever after, and she cried. The tears always felt as if they came from nowhere, slamming into her like a truck careening into the wall of a tunnel. They hit hard and fast, overwhelming her with sadness, then leaving her wrung out, empty. Their occurrence was so erratic that it was easy for Charlie to disconnect them from her grief. To think of them as random eruptions of sadness.

I’m just an emotional person, she told herself, and eventually, she started to believe it.

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

She felt strongest, most focused when she was practicing magic. She dropped out of circus classes. Stopped performing magic for big audiences. Trained in the safety of her bedroom, brought her tricks to her family or to Lou only when she could not improve them any further. She no longer cared whether they reacted with awe. She cared only for the lie, for that moment of perfect deception, when everything the viewer thought to be true was turned on its head.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

The world had deceived her, had taken away the one person who should have been by her side her entire life— and she would deceive it right back.

And on that particular morning, she was watching the bullet catch over and over, taking notes on every minute detail of the act.

The bullet catch was a trick that had only ever been performed

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

by a handful of magicians, due to the high probability that they would die in the process. In the act, a gun was fired directly at the magician, who then caught the bullet in their mouth. It was first performed by a magician who called himself Chung Ling Soo— a Scottish American man falsely representing himself as Chinese. He lost his life in the process, shot to death on stage. The trick was so famously dangerous that not even Harry Houdini dared to attempt it.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

One magician who successfully performed the bullet catch— and the only woman to ever have done so— was Dorothy Dietrich. Charlie had become somewhat fixated on Dietrich in the past few years. She researched every website she could find on the female magician, watched documentaries on YouTube, checked out books from the local library. It was never enough. There were no videos of Dietrich performing the bullet catch, only photographs.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

The most detailed videos she could find were from a similar stunt performed by the magician duo Penn and Teller. In the trick, both magicians asked an audience member to choose a bullet and sign it with their initials. They then lined up the red-dot sights on the guns to point directly into each other’s mouths. At each stage, they asked the audience to confirm that the guns were loaded with the proper bullet, the safety turned off, that everything was clear and legitimate. At last, they fired, the panes of glass between them breaking to prove the bullets went through. Neither magician was hurt. When they opened their mouths, they’d caught the opposite person’s bullet in their teeth, as if they had grabbed it out of the air.

Penn and Teller never explained how they pulled off this

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

trick. Anyone who tried to figure it out could only do so through conjecture.

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

For Charlie’s part, she was obsessed with the trick. Obsessed with peeling back its layers, with finding the lie that made it all seem true. She had watched the same video of the same trick’s performance at least two hundred times.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

Just as Charlie made it to the end of her fifth rewatch of the morning, a knock sounded on the library door. She looked up to find her mom poking her head inside, a basket of laundry under one arm.

“Hi, sweetheart,” her mom said.

Charlie shut the screen of her laptop. “Hi, Mom.”

“Sounds like it was quite the party last night, huh?” Her mom quirked an eyebrow.

“You heard?”

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

“It’s all over the news. Police are saying they’ve identified the shoes as definitely belonging to Robbie. Sheriff Carpenter is frantic.”

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

“I’m sure.”

Adjusting the laundry basket on her hip, her mom tilted her head. “Listen. I know I give you a lot of trust and leeway when it comes to the car and curfew, but I think there are a few things we should discuss.” She stepped inside the library and shut the door behind her, setting the laundry basket down on the carpet. When she straightened up, she crossed her arms and leaned back against the door.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

Charlie waited. Her mother seemed to be weighing her words carefully.

At last, she said, “Silver Shores is not safe right now.”

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

“I know,” said Charlie. “We all saw that tree.”

“I don’t enforce a lot of rules around here. You and your brother are smart kids, and I trust you to take care of yourselves.”

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

That much was true. Her mom didn’t enforce a lot of rules. Charlie and Mason were allowed to go to parties and keep their own car just so long as they were honest with their mother about what they were doing. She preferred that her children be comfortable asking for a ride if they had been drinking, rather than walking home in the dark or getting behind the wheel of the car intoxicated. She gave them leeway because she believed it actually kept them safer.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

Sometimes, Charlie wondered if, had her father stuck around long enough to watch his kids grow up, he would have parented them differently. More strictly.

She would never know the answer. And frankly, she didn’t want to. She knew exactly two things about her father: his name (Walter Moray) and the fact that, shortly after she and Sophie were born, he chose drinking and gambling over sticking around to help raise his kids. Whenever she tried to ask for more information, her mom said that he wasn’t “worth the breath it would take to answer.”

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

Eventually, Charlie stopped asking.

“But,” her mom continued, “these are extraordinary times.”

“I understand. And I already know what you’re going to say: don’t stay out too late, don’t go out without a buddy, don’t take rides from strangers.”

Her mother nodded. “There’s one more thing, too.”

“What’s that?”

“I want you to stay out of the forest.”

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

Charlie knit her eyebrows. “Why would I go in there? For all I know it’s, like, a breeding ground for serial killers right now.”

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I’m serious, Charlie.” Her mom crossed the room and sat on the desk beside the armchair. “It’s more than Robbie’s disappearance. I can’t explain it, but . . . every time I drive past those woods, I get this . . . pit. In my stomach.”

“A pit?”

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“I know it doesn’t make sense. And I probably sound crazy to you, but . . .” She leaned forward on the desk, eyes pleading with her daughter. “Just . . . don’t go in there. Please.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

Charlie couldn’t believe her mother really thought she needed to ask her this. Why would she go back into that forest? Why willingly risk her life by entering the place where Robbie’s shoes were found?

And yet—

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on the floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

And yet there was an odd tug inside her. A sort of wire running between her chest and that tree. She hadn’t known it existed, not until now. Until she went looking for it. But all it took was one glance into the forest, and she felt it. A yearning. A call to the wild.

Ridiculous, she thought. She wasn’t an idiot. Of course she would listen to her mother.

“Yes,” she said finally. “Yes. You have my word.”

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

Her mother exhaled, as if she’d been holding her breath. “Wonderful,” she said, standing up and walking back toward the door. “Oh!” She clapped. “Last thing.” She bent over and pulled a slim object out of the laundry basket, then carried it across the library. “I brought you something.”

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

She held out a small book. Charlie accepted it, studying the cover.

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

“With Sin and Roses?” she asked, looking up at her mom. “Seriously? Is this another one of your sex books?”

“They are not sex books,” her mom said, feigning offense. “They’re romance novels. They inspire us to dream of great love and adventure.”

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

Charlie rolled her eyes, tucking the book into the folds of the armchair. “Thank you.”

But Elias hadn’t.

She patted Charlie’s head, then recrossed the room and picked up her laundry basket. “Just give it a try,” she said over her shoulder. “You never know; you might like it.”

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

“Sure,” Charlie said as her mom closed the door to the library.

She reopened her laptop and went back to rewatching Penn and Teller. Every few minutes, however, her eyes darted over to the book stuffed into the side of the armchair.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

The truth was, Charlie used to love books like that. She and Sophie used to tear through little-kid love stories about princesses and fair maidens, stacking the finished books on their bedside tables until they formed towers so tall and precarious that the girls were forced to move the books to the bookcase in the corner of their room. As they got older, their interest in books waned, until all that was left of that obsession was a dusty old bookcase filled with dusty old books.

Which, if she was being honest, was the perfect metaphor for her own love life. A dusty bookcase filled with little more than a few dusty, drunken dance-floor make-outs— and that was exactly how she liked it.

No reason to go changing things now.

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

Charlie tried to obey her mother. Really, she did.

She tried when she overheard Mason chatting excitedly about the tree to friends over the phone. When her mom had the news on nonstop. Even when she watched “expert” after “expert” (local university teachers with degrees in God only knew what) try to parse out the Norse symbols. She kept her mind off the mystery. Told herself that the tug in her chest was all in her imagination. That she should’ve never gone out there to begin with.

So, yes. She tried. But all it took was one text. One measly message from Lou that said, Let’s investigate, and she was out the door.

She took the Ford. She knew that she would catch hell from Mason— he was always on about seniority and elder brother’s rights but it was as much her car as his. Her mom had made that clear on her sixteenth birthday.

It was an old car. A dark-green Bronco, stick shift. The engine made a funny noise when you went over sixty miles per hour, but Charlie loved the car regardless. It held a special place in her heart, her ticket to freedom, even though she still didn’t know what she wanted freedom from. Or for.

Noyes

“Where’s Abigail?” Charlie asked when Lou got in and slammed the door.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burning line on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

“Not interested in joining us.” Lou fastened her seat belt and slid her shoes off. She lounged backward, putting her socked feet up onto the dashboard. “You should’ve seen the text she sent me. It was all You’re going where?! But that’s a crime scene, Lou! Do you have any idea how illegal that is?! So I said, Good. I can’t wait to add ‘arrested for obstruction of justice’ to that resume you keep talking about.’ Lou cackled, slapping her knees excitedly. Then she straightened up and shook out her long pale-auburn hair, suddenly serious. “Anyway. Can we get Starbucks?”

Charlie stared at her best friend. “You want to pick up a latte on the way to a crime scene?”

“Obviously.” Lou turned her attention to the road. “This detective needs some caffeine.”

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

The clearing was fenced in with caution tape. Police cruisers had driven off the road and into the forest, parking as close as they could get to the scene. News vans formed a perimeter at a safe distance away from the police, with reporters holding microphones and speaking into oversize cameras.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

Charlie and Lou hid behind two pine trees with a partially obscured view of the scene.

“What exactly is our plan here?” Charlie asked. “We’re not going to push our way onto a crime scene, are we? They’ll never let us through.”

“No, no.” Lou waved the hand that clutched an iced vanilla latte—which Charlie paid for, naturally. “The police are only looking at that one area right now. We’re here to find other clues. The stuff they might miss.”

Text sent, she looked around the living room. At first glance, it was as shabby and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. But as Elias lit the fire, warm brushstrokes of orange spilling out into the space, she noticed some touches that clearly spoke of home: clean pillows, half-drunk mugs of coffee, a honey-colored knit blanket draped over the back of an armchair, a stack of paperbacks on a side table. As the fire burned brighter, warming her bones and filling the room with light, she began to suspect

“Such as?”

that, with a bit of dusting and tidying, the space could feel very homey indeed.

Lou shrugged. “Anything. I say we split up and do a sweep. I’ll go east, you go west.”

“Do you really live here?” Charlie asked.

Charlie raised her eyebrows. “Do you really think splitting up is the most sensible idea? We are in the very forest where someone we know was kidnapped. Or murdered. Or both.”

Fire built, Elias turned around on his knees. He looked around the room as if seeing it for the first time— or perhaps seeing it through the eyes of an outsider for the first time.

“I do,” he said. “For now, at least.”

“It’s probably not the best idea,” Lou agreed. “But for the sake of time, and because you know I don’t care much for things like ‘being sensible,’ we’re going to do it anyway.”

“How have the cops not run you out? This must have been the first place they looked when they started investigating the disappearances.”

Laughing, Charlie shook her head. “Do you even know which way is east?”

“Duh.” Lou pointed through the trees at the hints of blue in the distance. “Lake Michigan is always west. I do sometimes pay attention in class, you know.”

Charlie held up her hands. “Fair enough.”

Elias picked up the first aid kit and moved to the foot of the couch, pulling over a low stool to sit on. He set the first aid kit on floor to his right and opened its lid to reveal an assortment of the usual materials: bandages, alcohol wipes, tweezers, gauze, hand sanitizer, ibuprofen. Elias reached for Charlie’s injured leg, pausing a half inch from her ankle. He looked up at her through his eyelashes, waiting for permission to touch her.

“Great. We regroup in twenty.” Lou saluted before spinning around. Over her shoulder, she said, “Try not to get murdered, or I’ll have Abigail to reckon with.”

Charlie’s heart did that funny contraction thing again. Not trusting herself to speak, she nodded.

Charlie laughed. She reached behind to touch her back pocket, making sure the card deck she’d tucked in there before leaving the house was still in place. This was one of her rituals. Some might call it a superstition. It was the same deck of cards she bought after Sophie’s death. The cards that pulled her through the worst of her grief. Once satisfied they were in place, she turned and started walking west.

Elias slipped his fingers around her ankle, gently lifting it from the floor. His fingers were warm again, not hot, though Charlie could swear the warmth they gave off somehow ended up in her stomach. He set her ankle on his knee, turning it slightly so he could inspect her calf.

He cleared his throat. “I made a deal with the ash wives when I moved in,” he said, and Charlie had to rake her mind to remember what it was they’d been talking about before he touched her.

Oh, yes— the old house and the police. Why they haven’t kicked him out yet.

It was a slow process. Charlie wasn’t sure what she was looking for, so she tried to search everything: the ground, which was covered in leaves, pine needles, and twigs that snapped beneath her shoes; the bushes, which ranged from thick and leafy to covered in juniper needles that stung when she tried to push them aside;

and the trees. The trees were her biggest point of interest. After all, it was a tree that had been vandalized with Nordic symbols, a tree upon which someone had hung Robbie’s shoes. Charlie’s gut told her that the trees would provide the answers she sought.

the madness of the chase and almost an hour sitting in the lake, she hadn’t even remembered that her leg was injured. Once she tuned into the spot that the vittra had scratched— a long, burnline on the back of her calf—it was impossible to ignore, but until that moment, she’d truly forgotten that she might need medical attention.

But Elias hadn’t.

“Wait,” she said as he started to shut the closet. He paused, and she nodded at the vätte shivering on her shoulder. “Do you have any hand towels?”

Charlie was surprised by how invested she was in this mystery. It’s not like it was great love for Robbie Carpenter that had pulled her into this; she barely knew him. He was perfectly nice, if a little shy. Had never been the first to offer to host a house party. Unsurprising, given that his father was the sheriff, but still. The longest interaction Charlie’d had with Robbie was back in second grade, when she and Sophie somehow roped him into a game of tetherball on the playground. Everything was going well—right up until Charlie accidentally launched the ball straight into Robbie’s nose. He left the playground sobbing. Sophie had been distraught. She never said so, but Charlie knew. Just like Sophie always knew when it came to Charlie. She missed that kind of knowing.

Once she and the vätte were both wrapped in soft cotton, Elias led them to the sitting room at the end of the hallway. She sat on the sofa, setting the vätte on one of the pillows. He made a nest of his hand towel and snuggled down into it until just the tip of his red hat pointed out of the fabric. As Charlie dug her cell phone out of her waterlogged backpack, Elias set the first aid kit on the floor and knelt on the dusty carpet in front of the fireplace, busying himself building a fire.

Charlie was so distracted by her thoughts she nearly didn’t see it.

The water had definitely damaged her phone. The screen was painfully slow, as if it were barely holding on. Still, she managed to type out a text to her mom, letting her know that she was fine and would be home soon.

She came to a halt in front of a birch tree. Skinny, sturdy trunk leafed with paper-thin slices of bark. It would have been so easy for her to walk right past. To miss the symbol carved just above eye level. The same one everyone had been talking about.

Odin’s Knot.

Charlie stepped closer. She reached out with one hand and ran her fingers along the deep grooves of the three interconnected triangles. This rendition was smaller than the one carved so prominently into the ash tree. Its grooves were not so harsh, so imbued with anger. This knot had been carved with a sort of tenderness, perhaps even reverence.