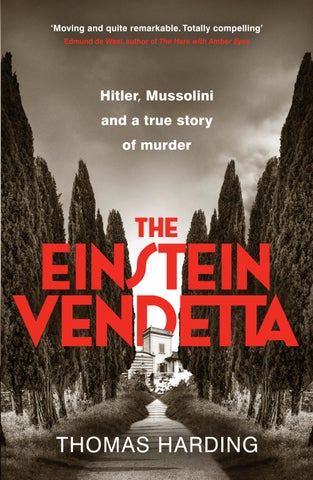

‘Moving and quite remarkable. Totally compelling’ Edmund de Waal, author of The Hare with Amber Eyes

Hitler, Mussolini and a true story of murder

‘Moving and quite remarkable. Totally compelling’ Edmund de Waal, author of The Hare with Amber Eyes

Also by Thomas Harding non-fiction

Hanns and Rudolf Kadian Journal

The House by the Lake Blood on the Page Legacy

White Debt

The Maverick picture books

The House by the Lake The House on the Canal

The House on the Farm fiction

Future History: 2050

PENGUIN MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Thomas Harding, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

For image permissions see page 343

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 13.5/16pt Garamond MT Std

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the eea is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A cip catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

hardback isbn : 978–0–241–65848–2 trade paperback isbn : 978–0–241–65849–9

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Christoph Partsch, for making it possible

Vendetta : Revenge, which can affect both the direct offender or any member of their family.

– Grande Dizionario Italiano (Italy)

Vendetta : (Italian) Blood revenge.

– Meyer’s Encyclopaedia (Germany)

Robert Einstein

‘Nina’ (Agar) Einstein

Luce Einstein

– Nina’s husband, father to Luce and Cici

– Robert’s wife, mother to Luce and Cici

– Robert and Nina’s daughter

‘Cici’ (Anna Maria) Einstein – Robert and Nina’s daughter

Seba Mazzetti

Anna Maria Boldrini

Lorenza Mazzetti

Paola Mazzetti

Maja Einstein

Albert Einstein

Orando Fuschiotti

Erenia Fuschiotti

– Nina’s sister

– Robert and Nina’s niece and god-daughter

– Robert and Nina’s niece, sister of Paola

– Robert and Nina’s niece, sister of Lorenza

– Robert’s first cousin, sister of Albert

– Robert’s first cousin, brother of Maja Il Focardo

– estate manager, or fattore

– wife of Orando

‘Pipone’ (Egisto) Galante – deputy estate manager

Giulia Galante – wife of Pipone Investigators

Milton Wexler – war crimes commissioner: New York, USA

Carlo Gentile – historian: Cologne, Germany

Judge Thomas Will – war crimes investigator: Ludwigsburg, Germany

Hubert Ströber – public prosecutor: Frankenthal, Germany

Marco De Paolis – military prosecutor: La Spezia and Rome, Italy

Barbara Schepanek – TV journalist: Munich, Germany

Brian Dalrymple – forensic expert: Toronto, Canada

Vincenzo Boldrini

1888 –1952

Ada Mazzetti 1892–1994

Lorenzo Mazzetti 1854–97

Paolo Mazzetti 1896 –1906

Sophia Conti 1865–1932

Seba Mazzetti 1888 –1953

Corrado Mazzetti 1892–1946

Olga Liberati 1891–1927

Lidia Mazzetti 1884–88

Ida Einstein 1865 –1922

Jakob Einstein 1850 –1912

ROBERT Einstein 1884–1945 NINA (Agar) Mazzetti 1885–1944

Eugenio Boldrini 1922– 90

Anna-Maria Boldrini 1926 –

Enrico Bellavite 1923–2016

Lorenza Mazzetti 1927–2020

Paola Mazzetti 1927–2022

Eva Krampen Kosloski 1956 –

LUCE Einstein 1917–44

CICI (Anna Maria) Einstein 1926 –44

Raphael Einstein 1839–42

Ignatz Einstein 1841–1911

Jette Einstein 1844–1905

Heinrich Einstein 1845–77

Abraham Rupert Einstein 1808–68

Helene Hindle Moos 1814–87

Edith Einstein 1888 –1960

Arthur Reiss 1893–1961

Elsa Einstein (2) 1876 –1936

Hermann Einstein 1847–1902

ALBERT Einstein 1879 –1955

Hans Albert Einstein 1904–73

Pauline Koch 1858 –1920

Mileva Marić (1) 1875–1948

Regine Einstein 1855–1938

Maja Einstein 1881–1951

Paul Winteler 1882–1952

Eduard Einstein 1910 – 65 Einstein 1902–?

‘Lieserl’

This is a work of non-fiction. As such, I have relied on investigative reports, written testimonies, letters, official records, photographs and other archival documents. I was also granted the rare opportunity to go beyond the public record. After winning a court case in Germany, I received a copy of the prosecutor’s files, the first time a journalist has gained access to such documents. And I was privileged to speak to various eyewitnesses, including many who were in their nineties, providing me with details that only those who have experienced an event first-hand can provide.

Ever since the events in this book took place, there have been numerous attempts to get to the bottom of what happened. As new information became available, opinions changed, the history was revised and then revised again. In Italy, there are two words for memory: ricordo and memoria. The first includes the word cor which means ‘heart’, and describes a more emotional, personal and fluid memory; the second comes from the Latin word mens, which means ‘mind’, and is more objective, collective and stable. This book attempts to capture both ricordo and memoria, in an effort to reach for the complete truth.

It was such a night that one knew that human eyes would not witness it and survive.

Robert Einstein was hiding in the woods, fifteen miles southeast of Florence, away from his house, away from his family. For two weeks now, he had remained holed up, within sight of his villa but concealed. All he had with him was a blanket and a book that he had quickly grabbed from his library. Some nights, he slept on the ground beneath the cypress, oak and hazelnut trees. Other nights, he found refuge with a local farmer. Afraid his whereabouts might be revealed to the Nazis who were looking for him, he never stayed in one place for more than twenty-four hours.

Two weeks earlier, members of the Hermann Göring Division had knocked loudly on his front door and demanded to see him. Luckily, he had been working in the fields at the time and the German visitors had been sent away. Later, he sat with his wife, Nina, and their two adult daughters, Luce and Cici, and discussed what to do. Was it safer to stay together or to separate? In the end, they had agreed that it would be best to separate: the women would remain in the villa and he would find somewhere close by and lie low. After all, it was Robert who was the target, and so it must

be Robert who must hide. If the Germans came back to the villa, the women would say that he was away. It had worked once already, why not again? As for Nina, Luce and Cici, they were Christian, this would surely insulate them from any possible violence.

But ever since he had said goodbye, giving a long hug to his daughters, kissing his wife on the cheek, he had worried that they’d made the wrong decision. Had they considered all the options? Were Nina, Luce and Cici in fact safe? Being apart made him feel powerless. Powerless to respond to changing circumstances. Powerless to protect his family. More than once, he had considered returning to the villa. At least then they would be together, able to face whatever adversity came their way. But then he remembered the reasons why they had separated in the first place, and so, reluctantly, he stuck with the plan: they would remain apart until conditions changed.

For two weeks, therefore, he had waited in the shadows, paralysed with anxiety, hoping that something would shift. As an engineer, he thought of himself as a man of reason. He did not rely on faith or superstition, nor was he one to pray. He assessed a situation according to the facts, so when he came across someone in the woods – a farmer travelling to one of the local villages, a band of partisans on their way from one action to the next, a black marketeer trading cigarettes, eggs or cheese – he pressed them for the latest news. Mostly, however, he was by himself. And so he listened intently to the noises around him, the boom boom of artillery shells getting closer and closer, the reverberant rumbling of B-24 and other Allied bombers flying more frequently overhead, the rat-tat-tat of machine-gun fire growing louder and more

frequent in the hills around. From all this, he concluded that the American and British ground forces would soon arrive in Florence and, with their superior resources, drive the dreaded Germans away from the region, and at last he would be able to reunite with his family. They would be safe.

Occasionally, and best of all, Robert was sometimes able to gather information from a source even more welcome, his dear wife. So it was that, at seven in the morning of 3 August 1944, Robert Einstein was standing at the edge of the wood, listening out for her footsteps. Though this visit was prearranged, they had agreed that it should be cancelled if Nina perceived any cause for concern, so her arrival remained uncertain. The minutes ticked by in relative quiet, too late for night-time aerial bombardments and too early for close-quarters combat. Occasionally, the tense silence was punctured by the cry of an unseen bird or the scuffle of some small mammal scurrying through the undergrowth.

Then Robert heard the crunch of footsteps approaching. Though quiet – whoever was coming was making an effort to keep the noise down – in the dry summer air, the sound echoed dangerously off the rocky path below. He caught some whispered words. Recognizing his wife’s voice, he called out her name, and a few moments later he saw her face; she was carrying a small package, and her forehead was beaded with sweat. Deep into the Tuscan summer, it was already swelteringly hot, but here in the shade it was mercifully cooler. It was also out of view, which is why they had chosen this place to meet.

Careful not to draw attention to themselves, and standing close, they greeted each other in hushed tones. Nina shared

the latest news, that the girls were doing fine, that the peach harvest had started on the estate, that according to the previous evening’s report on BBC radio the Allied forces were only twenty miles south of Florence. How long would he have to remain in the woods? Perhaps not too long. From what Nina was saying, the British and American forces were even closer than he had hoped. After four years of war and eleven months of German occupation, it might soon all be over, maybe as early as this week. Perhaps even as soon as tomorrow. It looked like the decision to split the family, with Nina and the girls staying in the villa and Robert hiding in the woods, had paid off.

As she spoke, Robert looked at his wife. Nina was fiftynine years old, with almond-shaped eyes, thin lips and shoulder-length dark hair. She still had her northern Italian accent despite decades of living in Rome and Tuscany. Indeed, Nina had hardly changed since they had first met more than thirty years earlier and their love had only grown with age. As for Robert, though his beard and hair were flecked with white, he felt younger than his sixty years. All those seasons working in the fields alongside the contadini, or farmworkers, had given him vitality and stamina. And, having grown up in Munich, he also had an accent, though he wasn’t sure his Teutonic roots were now a hindrance or a benefit.

They continued to catch up, careful to avoid certain subjects. Nina didn’t want to know where Robert would be staying that night in case she was questioned. Nor was there a need to discuss the protocols in case of an emergency. They had been over these many times. If Nina came looking for him at a time not previously agreed, then he was to remain

hidden. On no account would he reveal himself, even if she appeared desperate.

They were coming to the end of their conversation when they heard a tremendous crashing sound coming from the direction of the villa. It sounded like something massive had been broken. Unsure what it could be, and now anxious, Nina quickly said goodbye to her husband and hurried away. Robert watched as she disappeared down the sandy track.

Nina ran the whole way, holding up her long country dress as she went. It took five minutes to reach the tall wrought-iron gates of their villa – Il Focardo.

She turned up the cypress-lined drive until, panting and drenched in sweat, she reached the main entrance and immediately saw what had caused the noise. The front doors had been smashed open. It would have taken tremendous force to break these solid timbers. She clambered over the splintered ruins and into the hallway. There she was confronted with the source of the destruction. In front of her stood seven heavily armed German soldiers.

Nina demanded to know what was going on. She spoke in fluent German, having lived for years in Bavaria with Robert. Ignoring the question, the commander asked for her name, to which she replied she was Nina Einstein. He then asked where her husband was, and Nina said she did not know. The commander persisted. They had orders to arrest him, he said, and was confident Robert was hiding nearby. It was useless to deny it. Where was he? Nina kept her silence.

The stand-off was interrupted by the arrival of the rest of the household. First came Nina’s two daughters. Luce,

the oldest, was twenty-seven and in her final year of medical school at Florence University. She was tall and slender, with dark, shoulder-length hair like her mother, and also like her mother she liked to wear practical country clothes. Cici, the youngest, was eighteen years old. She attended the Michelangelo High School in Florence, one of the best in the city, where she was achieving mostly good grades, excelling in religious studies, Italian and history, but, according to her teachers, needing to improve in mathematics and physics. She was a head shorter than Luce, with blond, curly hair and a dimpled chin; unlike her more serious sister, she tended to wear shorter, fashionable dresses that were cut just above the knees. With them was Ali, the family’s black-and-white sheepdog, who padded around the room, sniffing the black boots and starched uniforms, curious about these strangers with their unfamiliar smells. Moments later, Nina’s younger sister, Seba, walked in, followed by Anna Maria (the eighteenyear-old daughter of Nina’s other sister, Ada) and the twins, Lorenza and Paola (the seventeen-year-old daughters of Nina’s brother Corrado). The hallway was now crowded. The seven Italian women stood near the entrance. Seven German soldiers faced them.

The commander asked Nina again for the whereabouts of Robert Einstein. The German, Nina was able to observe, was in his thirties, had a scrawny face and wore round metal glasses. She did not reply. This had been the agreement. If soldiers came looking, they had decided the best thing was to keep silent.

The commander had another go, his voice now rising. Where was her husband? Where was the cousin of Albert Einstein?

Robert Einstein was born at 8.30 in the morning on 27 February 1884 at his parents’ home in Munich, Germany. According to his birth certificate, the religion of his mother Ida and that of his father Jakob was ‘Mosaic’ (Jewish). They lived with Jakob’s brother, Hermann Einstein, and his wife Pauline, along with their two children: two-year-old Maja and four-year-old Albert.

The two families lived together in the same building at Müllerstrasse 3, just south of the Old Town. A year after Robert’s birth, they built a two-storey house at Rengerweg 14 (later Adlzreiterstrasse), a quiet street three miles southwest of the city centre. They were the only residents, often cooking for each other and socializing as a single unit. According to one chronicler, the Einsteins were solidly upper middle class.

By the autumn of 1888, there were four small children in the house, Ida having given birth to a girl, who they called Edith. And while young Albert tended to keep himself to himself – later he would say that he had been ‘inwardly inhibited and alienated’ – he spent considerable time with his cousin Robert. The families also studied together, Jakob

in particular helped Albert with his mathematics. There was music in the house: Pauline, who was a fine pianist, taught Robert and Maja the piano, while Albert played Mozart and Beethoven sonatas on the violin. The children played together too. One of their favourite spots was under the magnificent row of tall trees which grew outside the house. In all, Robert and Albert would live in the same property for eleven years. And while Robert was four years younger than Albert, they held a deep affection for each other. They were close; some might call them brother-cousins.

Robert’s father and uncle ran an electrical engineering company called ‘J. Einstein & Co.’ which made equipment for the electrification of public spaces. Their factory stood just a few hundred feet from their home on Adlzreiterstrasse. Trained as an engineer, Jakob was responsible for the scientific aspects of the business, while Hermann focused on the commercial side, including employment, marketing and accounting. Their personalities, however, were not necessarily suited to these tasks. Hermann ‘owing to his contemplative nature may have lacked the qualities required of a businessman’, Maja later recalled, whereas Jakob was ‘constantly seeking novelty and change and unable to learn from any failure, and was an over-eager and even stubborn optimist’. But for a while, at least, the enterprise thrived. By 1890, the number of employees had risen from twenty to 200. Projects included the electrification of the Munich Oktoberfest on Theresienwiese, the provision of street lights in Schwabing (a suburb outside Munich) and the installation of lighting in numerous cafés, a maze and a shooting gallery. By any measure, the company was a success.

Robert’s parents and uncle and aunt were fairly relaxed

when it came to their Judaism. ‘A liberal spirit, undogmatic in matters of religion prevailed within the family,’ Maja wrote. ‘There was no discussion of religious matters or rules.’ That is not to say that the Einsteins rejected their Jewish heritage. On the contrary, they followed many of the religious traditions. When he was a baby, Robert was circumcised; and later, as a young child, he was instructed in the basic tenets of Judaism. Each spring, he would gather with the rest of the family around the table at home to celebrate Seder and recount the story of the Jews’ escape from slavery in Egypt. The family also belonged to the Jewish community association in Munich, which was just a fifteen-minute walk from where they lived. Robert and the others would dress up in their best clothes and attend the most important annual services, including Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah.

When Robert was six, his cousin Albert grew intensely interested in Judaism. As a result, Maja remembered, Albert became ‘so zealous in his religious feeling that he strictly adhered to all the details of religious regulations’. Providing one example, Maja said that her brother stopped eating pork. It is probable that he also stopped eating shellfish and encouraged his family to purchase their meat from a kosher butcher. Pauline or Ida would have been unwilling to prepare separate meals, so the entire family now had to follow young Albert’s diet. It wasn’t long, however, before Albert’s growing interest in science put an end to his religious exuberance. At this point, much to everyone’s relief, the family’s eating habits returned to normal.

In the spring of 1894, when Robert was ten years old, the family suffered financial calamity. Jakob and Hermann’s business was already overextended, its investments in machinery

and salaries considerably exceeding its income, and when the company lost a crucial contract to provide public lighting for Munich’s city centre, matters reached breaking point. In a dramatic move, the brothers decided to close down their company in Munich, liquidate its assets, and start again in the heavily industrialized region of Milan in northern Italy. Robert had to say goodbye to his friends, his teachers, and the city which had always been his home.

There is no record of the emotional impact on Robert of the family’s sudden change in fortunes. Nevertheless, we know from Maja that the move was difficult. She recalled that while they were waiting to be relocated to Italy, she, Robert and the other children watched the family’s land being sold to make way for new tenement buildings. In the process, the cherished trees outside their house were cut down. ‘Until it was time to move,’ Maja remembered, ‘we had to watch the destruction of our favourite memories from our home.’ The collapse of the family business also had a dramatic effect on Robert’s older cousin: Albert’s ‘discomfort spiraled toward depression’, reported his biographer Walter Isaacson, ‘perhaps even close to a nervous breakdown’.

Upon arrival in Italy, Robert was enrolled in a local school. He found himself in a strange new place, without friends and where the people spoke a foreign language (he didn’t know Italian). The two families once again lived together. First in Milan, and then, soon after, in an apartment at Via Foscolo 11 in Pavia, a town twenty miles south of Milan. While the apartment was smaller than their Munich home, they had use of a cloistered courtyard that provided shade in the summertime and a small garden that boasted lemon and sweet gum trees. As for Albert, who was now fifteen

years old, his parents decided, much to his chagrin, that it was best if he stayed behind in Germany to continue his studies. When he came home to Pavia for Christmas, Albert made it clear that he would not be returning to Munich. He spent the next ten months living with Robert and the others, during which he prepared his application to the polytechnic in Zurich and wrote his first essay on theoretical physics. Their lives were just beginning to feel stable when, in 1896, the Einstein brothers’ business took another bad turn. After failing to win a contract to electrify the town of Pavia, their company again went bankrupt. This second financial collapse was perhaps even more painful than the first. Not only was the inheritance of Robert’s aunt Pauline lost in the venture but also significant donations from other relatives. ‘The family,’ Maja later wrote, ‘was left with hardly anything.’ From this point forward, the two brothers split their financial affairs. Hermann set up a business in Milan, while Jakob worked first in Lecce, a small city in southern Italy, and then in Genoa, in the country’s northwest, where he secured a job as an engineer for a large company. As for Robert, he stayed with his uncle, aunt and cousins in Milan for a year, attending the Giuseppe Parini High School, before joining his parents in Genoa. This would be the fourth time Robert had moved in three years; it was also the first time in his life that he would be living away from his cousins. Things finally settled down in Genoa. The family’s income stabilized, the stress of running a business was behind them and they had all improved their Italian language skills. Indeed, they were increasingly enjoying Italian culture, food and attitudes. Robert, in particular, fell in love with the Italian countryside, and whenever he could he spent time in nature.

It was around now, after turning thirteen in the spring of 1897, that he probably performed his bar mitzvah at a synagogue in Genoa. Sometime soon after, he decided that, though he belonged to the Jewish culture and cherished its traditions, he did not believe in the existence of God. It did not agree with his rational proclivities. Following the example of his cousin Albert, he was, he concluded, an atheist.

Over the next few years, Hermann tried one enterprise and then another, but none found great success. He died in Milan in 1902 of heart failure, aged fifty-five (Maja blamed his death on years of financial worries). Seven years later, Robert’s parents divorced and, three years after that, on 8 September 1912, Jakob also died from a heart attack, aged sixty-two, in Vienna. According to the death notice posted in the local newspaper, Robert and Edith were ‘deeply shocked to announce the passing of their dearly loved and unforgettable father’.

At the time of his father’s death, Robert was twentyeight years old and had left Genoa. Following in his father’s footsteps, he had studied to become an electrical engineer, and, after graduating, he had moved to Rome. It was there that he met Nina Mazzetti. On the surface, they had little in common. While her family went back generations in northern Italy, his roots were German. She belonged to the Protestant Waldensian Church while his family were Jewish. Yet they shared numerous interests that brought them together. They both liked to read, adored classical music and enjoyed taking walks in the countryside. They also shared aspirations. They both wanted to live on a farm where they could keep animals and grow their own food, and they both wanted to start a family. They also both knew hardship. When Nina was three,

her older sister Lidia died; when she was twelve, her father died, leaving her mother to take care of her and her four siblings; and when she was twenty-one, her younger brother Paolo died. Through these connections, and more, Nina and Robert formed a tight bond.

So it was that, on 13 October 1913, Robert and Nina were married in a civil ceremony in Rome. Not long after the wedding, Robert said he wanted to return to Munich to see if he could resurrect the family engineering business. It was almost twenty years since his father and uncle had been forced to flee the city in humiliation. And so, at the start of 1914, full of the spirit of optimism and resilience, the newlyweds moved to Germany to build a new life for themselves. Their hopes for calm domesticity were dashed, however, on 1 August, when Germany declared war on Russia. At this point, Robert could have found a way to return to Italy with his young wife. Instead, just seven days after the start of the war, the thirty-year-old Robert Einstein enlisted in the army. His father, Jakob, had served as an engineer in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, and now it was his turn to do his duty. Like the majority of assimilated German Jews, Robert considered himself to be German first. It was normal, therefore, for a Jew such as himself to enlist, just as it was for the rest of the population. Indeed, it was mandatory for all German men aged seventeen to forty-five. This did not stop accusations circulating in the media that Jews were cowards and lacked patriotism. Such attacks prompted the military to conduct a count of the number of Jews in its ranks and it was found that over 100,000 Jewish soldiers served in the German Army, roughly the same proportion as the general population. This finding, however, was never