Nature’s Memory

By the Same Author

Wild (2025)

Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammals (2022)

Animal Kingdom: A Natural History in 100 Objects (2017)

Nature’s Memory

Behind the Scenes at the World’s Natural History Museums

Jack Ashby

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Jack Ashby, 2025

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Set in 12/ 14.75 pt Dante MT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–65688–4

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

List of Illustrations

Photographic acknowledgements in italics

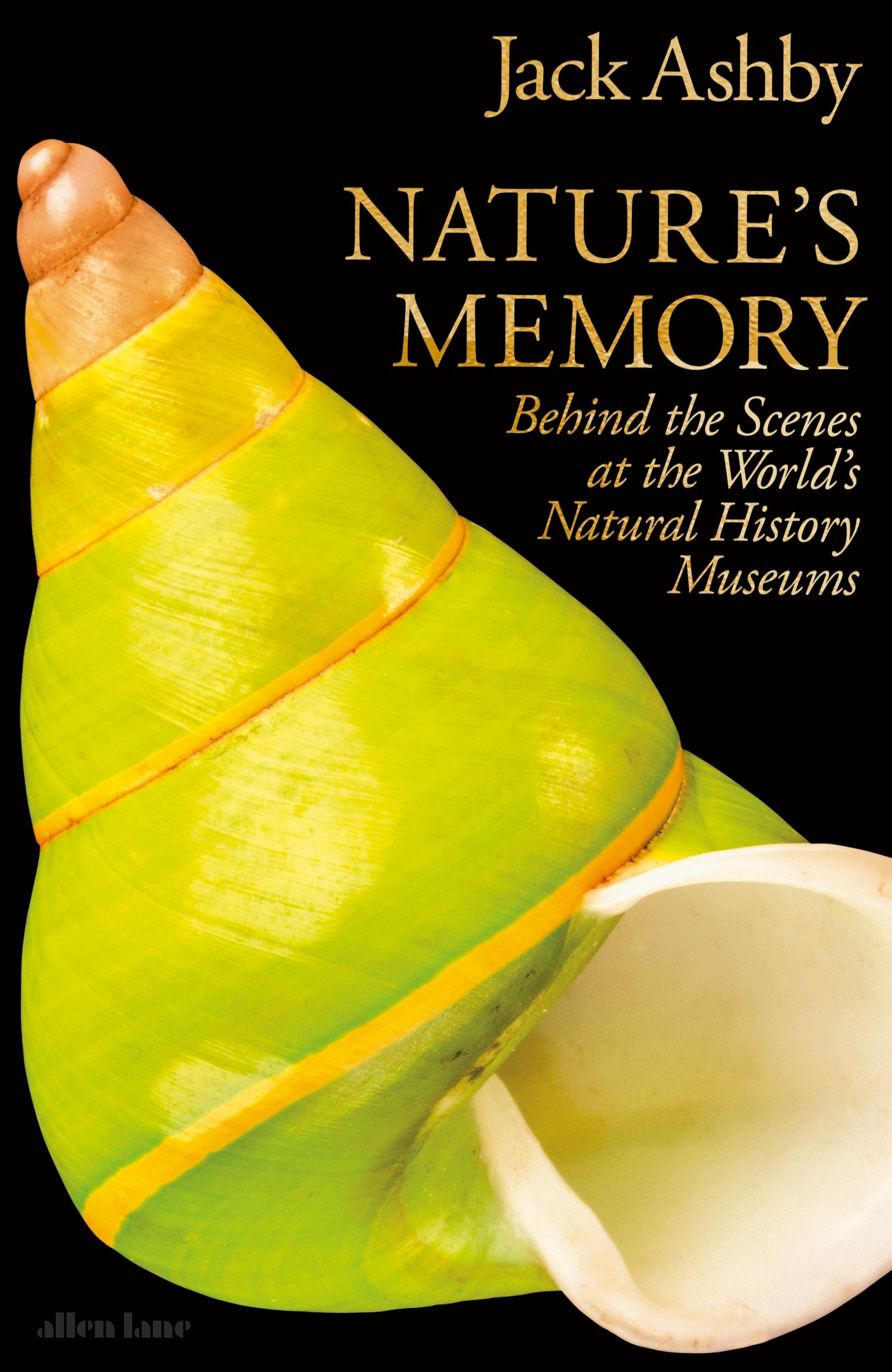

1. The original Dippy – the real Diplodocus fossil on display in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. © Carnegie Museum of Natural History

2. The real skeleton of SUE the Tyrannosaurus rex, the most complete example of the species discovered so far, on display at the Field Museum in Chicago. © Field Museum and Lucy Hewett.

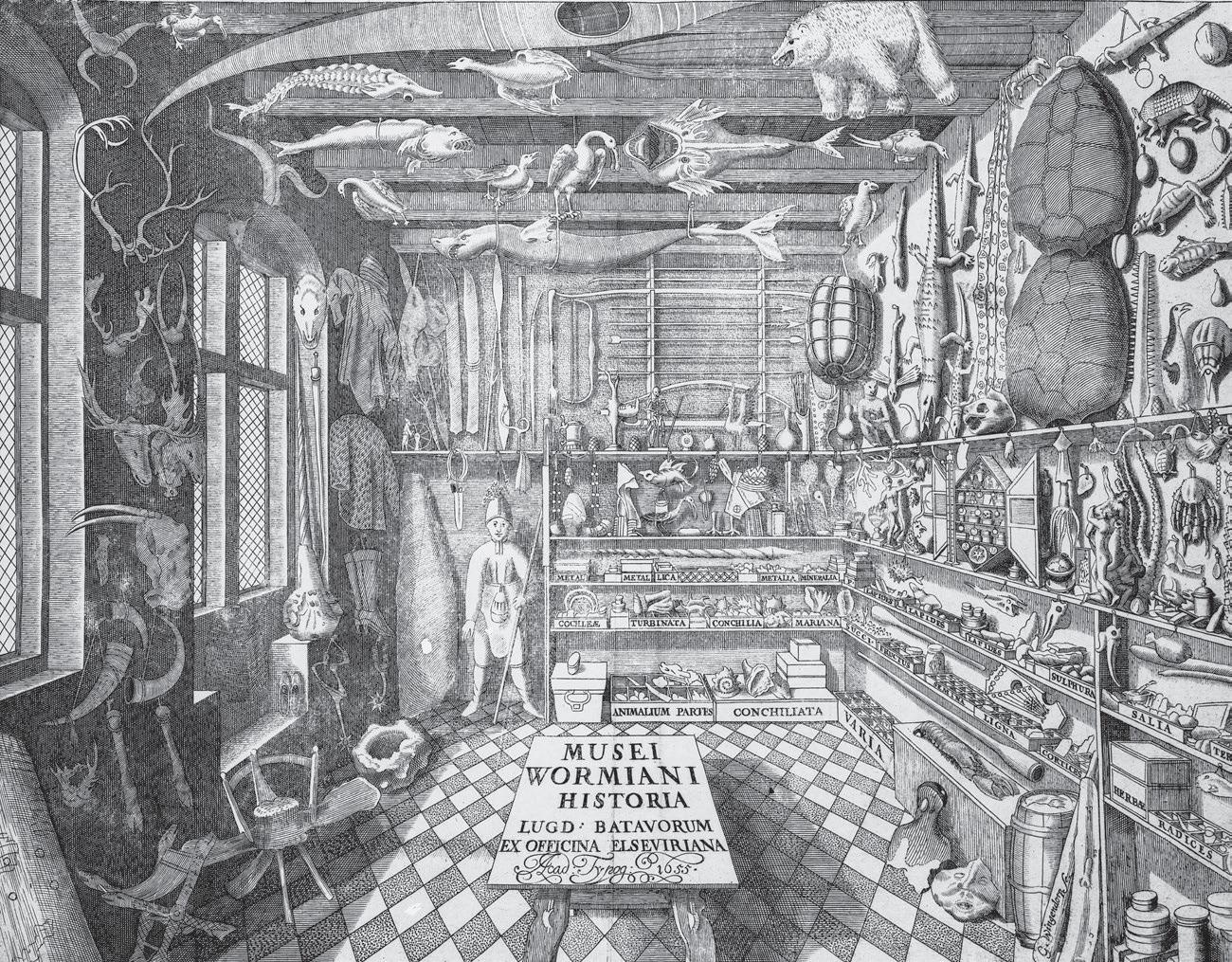

3. The Museum Wormianum, constructed by Ole Worm in Copenhagen in the 1650s. The Wellcome Collection.

4. Some of the preserved fishes at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, which Charles Darwin collected on board HMS Beagle as he travelled around the world in the 1830s. © University of Cambridge/Chris Green.

5. The Artist in His Museum by Charles Willson Peale, 1822. In Philadelphia, Peale was a pioneer in taxidermy displays –depicting birds with painted landscape backgrounds and performing behaviours. Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1878.1.2).

6. ‘Bullock’s Museum (Egyptian Hall or London Museum), Piccadilly’: the interior by Thomas Shepherd, 1810. The Wellcome Collection.

7. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hyena Jackal Vulture, 1976. Gelatin silver print, 16 1/2 x 21 3/8 in (41.9 x 54.3 cm), edition of 25; 47 x 58 3/4 in (119.4 x 149.2 cm), edition of 5. Negative 106. © Hiroshi Sugimoto

8. ‘The Man-eaters of Tsavo’ at the Field Museum in Chicago. © Getty Images.

List of Illustrations

9. George Washington’s Chinese golden pheasants, mounted by Charles Peale in the 1780s. © President and Fellows of Harvard College

10. The fin whale skeleton above the entrance to the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. © University of Cambridge/ Julieta Sarmiento Photography.

11. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ 1850s recreation of Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus at Crystal Palace, illustrated in Matthew Digby Wyatt’s 1854 Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham .

12. An 1890s depiction of female and male giant deer, showing the massive span of the males’ antlers. Extinct Monsters by H.N. Hutchinson (1896).

13. The type specimen of the Rodrigues parakeet – a female described by Alfred Newton in 1872, and illustrated for him by John Gerrard Keulemans in 1875. The Ibis: A Quarterly Journal of Ornithology, vol 5, series 3

14. ‘Big Mama’ the Citipati fossil, crouching protectively over its eggs. © American Museum of Natural History.

15. A drawer of pinned swallowtail butterflies at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. © University of Cambridge/ Chris Green.

16. Insects from an early stage in Darwin’s biological career, now in the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. © University of Cambridge/Julieta Sarmiento Photography.

17. The Micrarium at the Grant Museum of Zoology, UCL. © UCL/Matt Clayton.

18. A herbarium sheet of Banksia dentata at the Natural History Museum in London, collected in 1770 on James Cook’s Endeavour voyage in eastern Australia. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

19. An intricate model of a Portuguese man-o’-war made in glass by the Blaschkas. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

List of Illustrations

20. Glass model of Fabiana imbricata by Rudolf Blaschka. The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants, Harvard University Herbaria/Harvard Museum of Natural History. © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

21. A double-tusked narwhal on display at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. © University of Cambridge/ Chris Green

22. A taxidermy greyhound on display as part of the Natural History Museum’s Tring Dog Collection. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

23. The endling Martha the passenger pigeon – the last member of her species – at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington.

24. The last known thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, in his cage at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart. Photographed by Ben Sheppard in May 1936. Courtesy of the Tasmanian Archives

25. Ali, Alfred Russel Wallace’s most trusted assistant on his Malay voyage, and collector of many or most of the birds sent back from the expedition, photographed in 1862.

26. Wallace’s standardwing bird-of-paradise. Illustrated by John Gould and Henry Constantine Richter in The Birds of Australia in 1869.

27. A lesser bilby illustrated by Joseph Smit in Oldfield Thomas’s Catalogue of the Monotremes and Marsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) in 1888.

28. In 1896, Walter Baldwin Spencer described the kowari as a species new to science, based on specimens collected by the Southern Arrente people, but named the species Dasyuroides byrnei , thanking Paddy Byrne for providing the specimens.

29. A springhare from the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, which was collected in a British-run concentration camp during the Boer War. © University of Cambridge (UMZC E.1441).

List

of Illustrations

30. Three of the thylacine skins that Morton Allport sent to the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, in 1869 and 1871. © University of Cambridge/Chris Green

31. John James Audubon’s illustration of a ‘swallow-tailed hawk’ (swallow-tailed kite) carrying a garter snake, in Birds of America – arguably the world’s most expensive book. Courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh

32. A specimen of the insect-mimicking orchid ‘Ophrys insectifera’ from Carl Linnaeus’s own herbarium. © The Linnean Society.

33. A disgruntled-looking mulgara about to be released on fieldwork. © Jack Ashby.

34. Part of the whale warehouse at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum Support Centre.

35. A herbarium specimen of the fern Woodsia obtusa collected in 1859 by the writer Henry David Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts, where he wrote Walden. © New England Botanical Society.

36. The only quagga ever photographed alive, at London Zoo in 1870, thirteen years before their extinction.

37. The ‘Wet Collection’ at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, stored in an enormous glass cube that visitors can view from the outside. © Carola Radke, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (MfN).

Introduction

Every specimen in every museum is utterly unique – and well over a billion specimens are held in natural history museums around the world. Yet most natural history museums themselves are very similar: they have similar goals, operate by similar rules, have similar collections and use the same kinds of specimens to tell the same kinds of stories. It is therefore possible to create a universal guide for these museums, to tell the stories of their collections and displays, to go behind the scenes and reveal some of their secrets. That’s what this book sets out to do.

My aim is to take you on a tour through a typical natural history museum. We’ll explore some of the objects you’re likely to find in any museum dedicated to sharing the marvels of life on Earth, and then try to unpick the surprising stories behind them. My hope is that next time you visit one, you’ll be able to look at the collections, and the institution itself, a little differently and understand more deeply what’s going on behind the scenes.

Arguably, we would not be able to take such a theoretical tour of a generalized art museum – their collections and stories are too variable. And yet, while natural history collections are vastly larger, cover infinitely more diverse subjects and a much greater span of time, a universal tour is possible for natural history, particularly in the West. A museum can opt to focus on local ecosystems, or represent animals and plants collected across the world, but ultimately, not only would a koala in a museum in Stockholm look incredibly similar to one in Sydney, so would the information on the label.

I doubt it would be possible to write a mission statement for all art museums. If we tried, I suspect it would be so non-specific it would miss the individual importance of these institutions. But we could certainly write one for natural history museums. They all

Introduction

want the same thing: to bring visitors closer to nature, to inspire them to care about the diversity of life with which we share the planet, and to feel connected to it, and to each other. To surprise visitors, to excite them. To show them familiar species and introduce them to unfamiliar ones, in the hope that they’ll be encouraged to want to protect them all. For what it’s worth, I think our museums are eminently successful at doing all this.

It’s curious that, despite the infinite diversity of animals and plants museums can choose from, there are some that we’re likely to find wherever we go. My old friend and colleague Mark Carnall proposed there could be a ‘Museum Bingo’ – a spotters’ guide to the specimens that consistently appear in pretty much every natural history museum – once you get your eye in it’s remarkable how similar displays are between institutions.1 Your scorecard would include a giant deer, an elephant, a giant Japanese spider crab, a dodo, a nautilus shell cut in half, a blue morpho butterfly and a taxidermy platypus, for example.

It’s not just many of the species that are universal, but also how they are represented and the kinds of stories they are used to tell. The objects are unique, and they each carry their own history, but they also have an awful lot in common, particularly when we start to think about how they have been brought together and put on display.

What interests me – and what I’ll be exploring in this book – is how natural history museums go about the business of sharing nature. I work at the University Museum of Zoology in Cambridge, as the assistant director, where, institutionally, we care for around two million animal specimens from across the planet. My job is to be responsible for the people who look after those collections, and also those who come to visit, explore, and be inspired, entertained, amused, horrified or educated by them. But in my twenty years working in museums, I have come to notice that the windows they open onto the natural world do not offer a clear view. Museums are not neutral or natural places, and the ways they present nature are not unmodified extensions of the natural world: specimens, and the stories they tell, have

Introduction

been artificially reshaped. Museums are made by people, and people are biased and political and – by and large – not very scientific. Whether or not our visitors notice it, museums reflect these biases and politics in their interpretations of nature.

A good place to start our tour is in the imaginary museum’s central hall. I bet you can guess what we will find there.

Dinosaur skeletons are often the iconic figureheads of natural history collections – so much so that they are an almost ubiquitous presence as an eye-catching centrepiece when you enter their museums’ main halls. Go to Berlin, Birmingham, Brussels, Chicago, Frankfurt, New York, Shanghai, Singapore and, until recently, London,2 to name just a few, and you’ll be greeted by one of these megabeasts. It makes sense: dinosaurs have acted as a gateway drug for many young people into the world of science, and for that these reptiles deserve our gratitude, and even to be put on a literal pedestal. Often a family’s visit is instigated by dinosaur-mad children, and this is one of the key reasons why dinosaurs are so prevalent in museums. Another reason why they are so commonly positioned in the grand entrance halls is that these are often the largest spaces in the building, and there is nowhere else such a huge skeleton could fit. That’s also why the animal you’re next most likely to find there is a whale.

Dinosaurs evolved to be the biggest animals ever to walk the planet. Some 100 million years ago, babies hatching from eggs the size of footballs could grow to become adults weighing about 50 tonnes, and that deserves our respect and attention. When lifesized models of 10-metre-long dinosaurs and other extinct giants were built as part of the blockbusting Crystal Palace Park in South London in 1854, newspapers had to explain that, despite their fantastical appearance, the models did in fact represent real species – they were not invented.3 The biggest dinosaurs belonged to the group known as sauropods, the four-legged herbivores like Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, which – with their extraordinarily long necks and tails, pillar-like legs and tiny heads – have no modern parallels.

Introduction

This is one reason why dinosaurs, without question, are the mustsee specimens that museum visitors make a beeline for – which is why we’re starting our tour here. But what are we actually seeing when we look at dinosaur skeletons in a museum?

The first thing to say about most dinosaurs in most museums is that they are not real: they are plaster casts, and plaster casts of composite skeletons, for that matter. Large dinosaur skeletons are hard to come by – in fact we’ve probably never found a whole one. Despite the amount of time and effort that has gone into finding and studying dinosaur fossils, we don’t know for sure how many bones the big species had, and therefore we don’t know if any are missing. This makes sense – imagine a puzzle of about 500 pieces in which there are multiple ways they could fit together. Then imagine you had ten copies of this same puzzle, but each copy was missing an unknown number of pieces, and you weren’t given an image of what the complete picture looked like, or even what shape it was. Even if you used pieces from all the sets to try to build one complete puzzle, you wouldn’t know if you were still missing any at the end. This is how composite dinosaur fossils work. We may have identified twenty different neck vertebrae, for example, and they seem to fit together, but nobody is sure whether there should have been twenty-one. To add to the complexity, we can never be 100 per cent confident that all the puzzles represent the same set anyway. Because they are incomplete, and the whole skeleton can’t be used to make an identification, it’s possible that the individual dinosaur fossils that are being used to make a composite actually belong to more than one species.

So, because these fossils are a finite resource, and it might take the discoveries from several excavation sites to provide enough bones to make a conceivably complete skeleton, museum preparators will often cast (or, more recently, scan and 3D-print) these composites and share them around the world’s museums.

Let’s take the world’s most famous museum dinosaur as an example: Dippy, the Diplodocus that has been seen by hundreds of millions – if not billions – of people in museums in London, Paris,

xiv

Introduction

Moscow, Madrid, La Plata, Berlin, Bologna, Mexico City and Vienna since 1905. All the Dippies on display in those cities are plaster copies of the same skeleton.4 I don’t want to dampen anyone’s relationship with a beloved museum specimen, but I suspect that many regular visitors to these museums consider the skeleton they encounter there to be ‘their’ special dinosaur, even though their counterparts in all the other cities with Dippies have the same sentiment.

The original, real Diplodocus fossil is in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, USA . However, that specimen is made up of at least six different individual dinosaurs, and some of the leg and feet bones that have been used to complete the skeleton aren’t actually from a Diplodocus at all. Instead, they belong to a Camarasaurus – a dinosaur that isn’t even that closely related to Diplodocus. Not only that, but in 2015 a major review of Diplodocus fossils from museums around the world suggested that Dippy’s skull had been misidentified – it actually belonged to a newly described dinosaur called Galeamopus. The study concluded that no dinosaur skulls yet discovered could be identified as belonging to a Diplodocus with certainty.5 This means that there is a question mark over what the skull of the world’s most familiar dinosaur looked like. I don’t mean to suggest that museums are setting out to deliberately deceive us, but it is true to say that not all museums are 100 per cent consistent about when they label their specimens as casts or composites, so it’s always worth a close look.

Even when we do have enough real fossil bones to make an acceptably complete skeleton, issues of engineering, architecture and mechanics still often get in the way of putting it on display. Given that fossils are made of stone, and many dinosaurs are incredibly big, a real mounted dinosaur skeleton can prove too heavy to be held up by a scaffold, or by the floor it would stand on. Nobody wants to spend years preparing a multi-million-dollar dinosaur fossil only for it to collapse onto the visitors who come to see it, or for it to plummet through the floor into the basement below.6

Museums have come up with some practical compromises to allow them to bypass these challenges without putting the

xv

The original Dippy – the real Diplodocus fossil on display in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. Most of the bones were found in 1899–1900, and casts were sent to museums around the world.

© Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Introduction

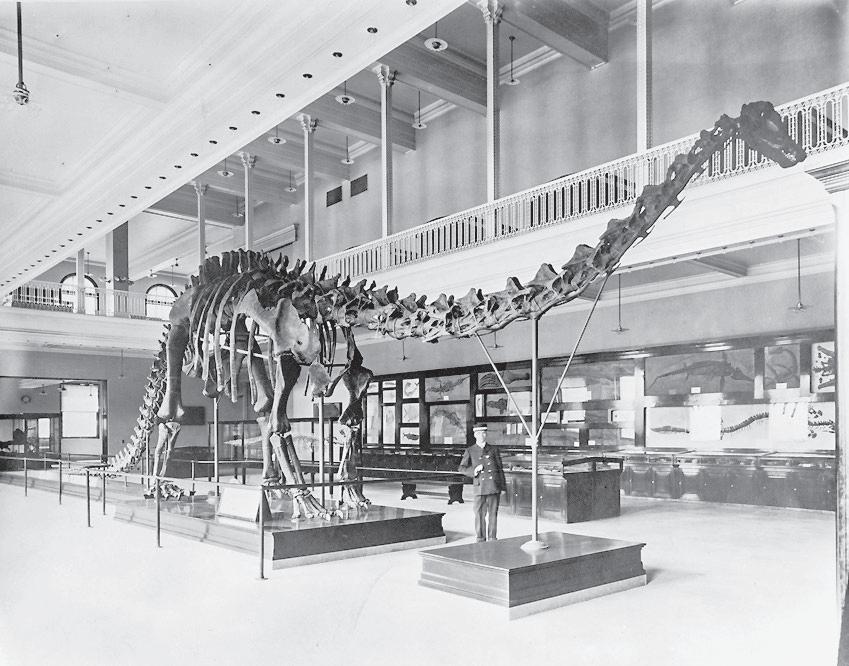

specimen, visitors or building at risk. After Dippy, the other contestant for the title of ‘world’s most famous dinosaur fossil’ is SUE the Tyrannosaurus rex. Named after Sue Hendrickson, who discovered the specimen in 1990 in South Dakota, with over 90 per cent of the skeleton present, SUE is the most complete fossil yet found of one of Earth’s biggest-ever land-living carnivores. Preparators at the Field Museum in Chicago were able to skilfully mount the real skeleton in such a dynamic, imposing way that it is as lifelike as a skeleton can be, augmented by dramatic light projections to help you understand what you are seeing and engage with it more deeply. It is one of the most effective natural history exhibits I’ve ever seen. However, the preparators determined that SUE ’s real skull was too heavy to be attached to the end of its neck. As a solution, they attached a lighter replica of SUE ’s skull onto the mounted skeleton, and displayed the real fossil skull in a case alongside. This has the added benefit of allowing easy access to the skull for the very many research scientists who want to study it.

The real skeleton of SUE the Tyrannosaurus rex, the most complete example of the species discovered so far, on display at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Introduction

My own corner of zoology is Australian mammals, and I’m as biased as the next natural historian who thinks their specialism deserves everybody’s attention. (This is one reason why Australian mammals feature more in this book than they otherwise might. So in writing a book that explores the biases on display in museum galleries, I should acknowledge that I too am biased in which examples I might select from the entirety of the natural world.) Therefore, before we continue, I should make a confession: I don’t care much for dinosaurs.

My palaeontologist colleagues might call it petty professional jealousy, but my disinterest stems from the fact that dinosaurs attract such a disproportionate amount of attention. In the press, a dinosaur discovery is more likely to receive coverage than almost any other story about the natural world, and I’d prefer that the media gave the public more opportunities to get excited about other kinds of organisms. Dinosaurs are considered so newsworthy that it’s common for articles that aren’t actually about dinosaurs to be labelled as if they are. When a massive ichthyosaur – the predatory marine reptile that lived at the same time as non-bird dinosaurs but is not at all closely related to them – was discovered at Rutland Water in central England in 2022, BBC News’s sensational headline was ‘Rutland Sea Dragon Dinosaur Dolphin Fossil Is Largest in UK ’. (For the record, they’re neither dinosaurs, dolphins nor dragons.)

As much as I may roll my eyes when yet another news story focuses on the dino-discovery of the week and distracts attention away from a more scientifically valuable story about literally any other kind of animal, I can understand why the coverage is so great. There is no other kind of animal specimen that attracts the same level of attention or investment as dinosaurs do. In 2020 another famous T. rex skeleton – known as Stan – sold at auction in New York to a mystery buyer for nearly $32 million (it was the most expensive fossil ever, until a stegosaur was bought anonymously in 2024 for an astonishing $44.6 million). After the sale the dinosaur vanished from public view, and the palaeontological community feared that this specimen – which at over 70 per cent complete had enormous

xviii

Introduction

scientific value – would be lost to the research community. However, eighteen months later it transpired that Stan was destined for a new natural history museum being built in Abu Dhabi, expected to open in 2025. It’s clear that both news outlets and museums know that dinosaurs sell. Incidentally, when SUE the T. rex was put up for auction in 1997, the Field Museum was only able to meet the $7.6 million price-tag with the help of the Disney corporation – who now have a cast on display at their Animal Kingdom resort in Florida; and McDonalds, whose logo was plastered all over resulting museum exhibits as casts toured the country.

So while I’m not suggesting that museums shouldn’t display dinosaurs, I do give a little sigh when every other part of the natural world is shunted into the corner to make room for them. Don’t get me wrong: they definitely inspire awe and wonder in ways that any museum should strive for in its displays. But when London’s Natural History Museum chose to remove its copy of Dippy from the central hall, and replace it with a real skeleton of a blue whale, diving down to meet you as you walk through the entrance, I was among those cheering them on. We are profoundly lucky to be here on Earth at the same time as blue whales.7 There is so much meaning in showing this whale – the biggest species ever to grace the Earth, which after almost being annihilated by human greed, has become one of the planet’s best conservation success stories. Likewise, when I see queues mounting for the dinosaur hall of the Natural History Museum when you can quite easily stroll straight into the mammal displays, I know which exhibits I would choose: give me a platypus any day.

Life as we show it

Giant dinosaurs notwithstanding, the public face of most natural history museums is a completely different beast to the one lurking behind the scenes. So, just what are museums doing in their galleries?

xix

Introduction

The totality of life on Earth – everything that has ever lived – is boundless. There is absolutely no way that any museum could tell the whole story, just as no museum focused on human history or art could ever be comprehensive, and they only have the activities and creations of a single species to communicate. Our collections are vast, and the vast majority of them are undisplayable. People are often shocked to learn that far less than 1 per cent of a museum’s specimens are actually on display, but it really does make sense. Natural history museums rarely collect for display – most of the collections you find in the galleries don’t look like the majority of what the museum holds, because most of the specimens in store have been simply prepared for use in research, rather than in an aesthetic way that visitors have come to expect for what goes on display. And honestly, you wouldn’t want to see millions of specimens at once. It’s too much to take in, and impossible to interpret. So, natural history museums must be selective about what to show. But how are those decisions taken?

Thanks to these choices that curators have made over the centuries, natural history museums are not particularly representative of nature. This is not intended as a criticism. Through our tour, what I hope to do is encourage readers to ask what it is they are looking at when they next visit – why was that specimen chosen over any others? Is there a reason that some kinds of animals, and some parts of the world, feature heavily in museum displays, whereas others don’t? Who really collected these specimens, and how are their stories being told? How did the specimens come to be there? Are they authentic representatives of their species? Do they convey a subconscious political message? And where are all the female specimens?

At this point, I should acknowledge that, just as museums can’t be comprehensive in their displays, I would also fail if I attempted to make this book truly representative of nature as a whole. I inevitably repeat some of the biases in what museums put in the limelight – there is so much diversity and so little space – but I hope that in exploring at least some of these biases, I will be undoing some of that injustice. And while we’ll travel to each continent

Introduction

in this book, you will notice a strongly Western bias. The idea of a Western natural history museum is tightly entwined with western concepts of nature, and their histories are linked with colonial ideals in ways that can’t be fully untangled. Of course, there are major natural history museums in regions beyond the bounds of former European empires; many new ones have recently been built or reimagined, particularly in East and West Asia; and many others were originally built in colonized regions by the colonizers. However, I must be realistic that my experience is with museums across the West, and it is the history and practices of these institutions that I mainly focus on. This will allow us to see the trends that do stem from the particular histories of the West over the last few centuries of museum-building. So please forgive my shorthand – this ‘universal’ guide is only universal from a Western perspective. I recognize that this has echoes of the kinds of omissions of other perspectives that I rail against through these pages, but it is across these Western institutions that I see the shared way of presenting nature, and the same kinds of histories.

In order to think about what museum displays are ‘doing’ today, we need to consider their historical roots. People have been collecting natural history objects for a long time. Much of the world’s oldest art is made from animals, depicts animals, or both. The Venus of Hohle Fels is the oldest known depiction of a human, and the Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel is the oldest known sculpture of an animal (it has a lion’s head and a partly human body). Both figurines were made from mammoth ivory 35,000–40,000 years ago, and so you could argue that they are natural history objects as well as cultural history objects.

A more obvious origin-story for modern natural history museums (and really all museums) can be found in European Renaissance Wunderkammer (literally a ‘room of wonder’ – a definition still befitting an effective museum gallery today), which arguably had their conceptual beginnings in collections of religious relics or royal treasures. Despite these early influences, the underlying philosophy behind

Introduction

the collections was at least partly scholarly – to better understand the world. Curiosity was the driver (yet the accumulation of material wealth was also a factor). Some of these ‘cabinets of curiosities’ were literally single pieces of elaborate furniture, but many were far more extensive, occupying entire buildings. Through them, prolific collectors sought to replicate the universe in a microcosm, and show it off to their mates. While important discoveries in natural history, medicine, alchemy, cultural history and engineering were made from these collections, they were not municipal institutions but very much the preserve of the elite.

The Enlightenment placed new emphasis on material truths and rational arguments based on observable reality, which paved the way for a heightened appreciation of specimen collections. Natural history and natural history collections progressed side by side: the science and the proof. Such collections did not remain the exclusive resource of the upper echelons of society, largely because anyone can assemble them, since nature is everywhere. Natural history is a relatively egalitarian science – founded by amateurs, and arguably impossible without them. Today, natural history is unusual among scientific disciplines in how much it relies on non-professional experts and citizen scientists.

Around the start of the nineteenth century, public museums began to appear in numbers – sometimes established by local authorities, national governments, universities and scientific societies, at other times developing directly from those Wunderkammer as they were passed from an individual to an institution. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, for example, claims to be Britain’s first public museum. Elias Ashmole donated his collection to the university in various stages between 1677 and 1682, and the museum opened the following year. Ashmole himself had acquired his collection (some say nefariously) from keepers of a cabinet of curiosities – a father and son both called John Tradescant. Another of the most famous cabinets of curiosities is that of the Danish physician Ole Worm, who amassed a vast collection of some genuinely astonishing specimens that we still might expect to find in ‘Museum Bingo’,

Introduction including crocodiles, sawfish saws and narwhal tusks. Parts of his collection survive in the Natural History Museum of Denmark, in Copenhagen.

The civic role of natural history museums evolved in support of their scientific and educational missions. One can feel the difference between a private collection of hunting trophies in a stately home and a public collection of taxidermy in a natural history museum. It’s hard to put a finger on how, but it’s possible to sense the purpose behind a public collection, and that changes how we view the specimens in it. Hunting trophies in a private collection, by contrast, feel like vanity, not science or learning. Walking the wood-panelled halls of Paris’s Museum of Hunting and Nature is a notably different experience to exploring the wood-panelled halls of France’s National Museum of Natural History, equidistant from the Seine, but on opposite sides of

The Museum Wormianum, constructed by Ole Worm in Copenhagen in the 1650s, is one of the most famous cabinets of curiosities.

Introduction

the river. The prominent palaeontologist Richard Fortey wrote that London’s ‘Natural History Museum is, first and foremost, a celebration of what time has done to life.’8 For me, private collections of hunting trophies seem to be far more about celebrating death.

But of course, natural history museums do also contain hunting trophies, both in the form of traditional mounted heads and full taxidermy. Such objects in private and public collections can be identical, since taxidermists and commercial field-collectors supplied similar objects to both. But there is something about the museum environment that encourages us to see these objects differently. As the role of museums in engendering a passion for conservation has grown, so the mounted trophy heads have migrated out of the galleries and into the storerooms, since it is impossible to look at them without thinking about people killing animals for fun. Go to the mammal storeroom of any large museum and you will find racks of these trophy heads, hidden away after they have been removed from display, suggesting an element of institutional shame. Alternatively, we might find signs in museums that are essentially apologizing to visitors for the fact that hunting trophies are still on public view.

Similarly, changing attitudes affect the way we see certain other specimens. In decades past, museums may have proudly boasted that one of their taxidermy tigers was ‘collected’ by King George V – presenting them as a kind of celebrity object. His Majesty shot thirty-nine of them on a visit to India in 1911, and they can now be found in natural history museums in London, Bristol and Exeter, to name a few. As public sentiments towards conservation and colonialism have shifted, these specimens take on a different character. They blur the lines between trophy and specimen.

Even excluding such examples, it would be disingenuous to suggest that natural history museums are – and have always been – just about promoting science. Like private trophy collections, museum histories reflect more than a pinch of vanity, albeit at a national scale, since – as I’ll discuss in Part Two – they are the repositories for the spoils of empire. Scientific ‘exploration’ (such an innocentsounding word) between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries

Introduction

gave imperial powers a greater understanding of which resources in their new-found colonies could be exploited. Those resources included people, as well as animals, minerals and plants – the fundamental building blocks of natural history museums. Indeed, a key function of the museums was to show off these colonial assets. The making of these collections sometimes involved activities that were explicitly and deliberately violent.

One of the most grotesque things I’ve ever seen in a museum is an enormous bust of the Belgian king Leopold II , who reigned from 1865 to 1909. Grotesque not only because of its subject but because it was made from ivory, created in part as an advertisement for the ivory trade – and therefore several elephants would have been killed to create something so vain as a statue. In 1885 Leopold II became the sole ‘owner’ and ruler of the Congo Free State – what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This was made possible thanks in large part to the work of the British explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who was employed by Leopold to establish his interests in Central Africa. One of Leopold’s subordinates had told Stanley, ‘It’s not about Belgian colonies. It is about establishing a new, as large as possible state and governing it. It should be clear that in this project there can be no question of granting the Negroes even the slightest form of political power. That would be ridiculous. The whites, who run the posts, have all the power.’9

From Belgium, Leopold oversaw a murderous enterprise in the Congo Free State to profit from the country’s natural resources through enforced labour and innumerable violent atrocities that are too horrific to list. The human suffering Leopold and his enterprise knowingly brought about ranks among the most abhorrent in recent centuries (and he invested extraordinary resources in running political propaganda campaigns to keep the atrocities hidden from European eyes).10 Key driving forces behind these brutalities were the export of rubber and ivory to Belgium for financial gain: between 1889 and 1908, 4,700 tonnes of ivory – from around 94,000 elephants – arrived at the port of Antwerp.

The bust of Leopold II was created in celebration. It sat at the

Introduction

centre of the palatial Museum of the Congo, which was built by Leopold on the outskirts of Brussels as a permanent display of the natural history, economic exports, ethnography and artwork of the colony. Living Congolese people were even put on display there in a ‘human zoo’ in the grounds outside. Leopold’s vision for the museum was explicitly for propaganda – to encourage investment in the extractive industries in the Congo, and to garner support from the Belgian population. His personal glorification through this ivory bust seems like the distillation of the callous ego and greed behind the museum – and the colonial project in general – into a single object.

The bust is still on display a few metres from its original position at the centre of the building’s main rotunda, but the museum around it is now quite a different institution (with a different name) from the one that Leopold founded. Unlike many museums with collections founded on the exploitation of other countries’ assets, today the Royal Museum for Central Africa (or AfricaMuseum) is explicit in acknowledging its history as a colonial propaganda machine, and the displays now aim to describe the collections, including the bust, in this context. Their mission statement says that the museum ‘is a place of memory of the colonial past and strives to be a dynamic platform for exchanges and dialogues between cultures and generations’, including considering Africa in both a contemporary and historical context.11

Museums are places of storytelling. They have been found to be one of the most trusted sources of information in the public realm, which means they have an extraordinary responsibility to the public today. It’s fair to say that this trust has not always been deserved. As with any story, you have to pay attention to who is telling it, and who they are telling it for, and museums have been telling a particular kind of story with a particular kind of audience in mind for a very long time. These stories elevate the importance of some of their characters while diminishing others, and they overlook the fact that there are many aspects of the history of museum collecting that were exploitative, painful and violent. The contributions, expertise and labour – as well as more visceral sacrifices – of certain

Introduction

groups of people, particularly women and people of colour, have been omitted from many tellings of the history of science.

In case it isn’t obvious (and it definitely isn’t obvious when you explore the galleries of most natural history museums), the discoveries that have furthered our understanding of the world and our place in it have not been made exclusively thanks to rich white men. The fact that the work of everyone else is so often missing means that museums are not telling stories truthfully, and are not representing many of the people in the societies they serve. This is the theme we’ll be exploring in the second part of the book, asking how well museums represent people, by investigating where their collections came from, how they were brought together, and who was involved.

Life, behind the scenes

While we mustn’t shy away from exploring the troubled aspects of their history, the scientific potential of natural history collections isn’t as well known as it should be, arguably because museums have never been very good at shouting about it. Most people recognize the educational value of museums, but are less aware of their significance to scientific research – this is the theme of Part Three of this book.

Thanks to the extraordinary things that these museums contain, studies have repeatedly shown that the public consider natural history their favourite of all museum disciplines, ahead of art, social history and archaeology. But that’s not why natural history museums are the best museums. Few people have cottoned on to this yet, but beyond the role they play in connecting people with the environment, natural history museums are the only ones that can help save the world. The specimens of animals, plants, fungi and other organisms that natural history museums care for are the most valuable evidence we have for studying and solving the great challenges our planet faces. World-changing science is done in these

museums, helping us understand the realities and implications of the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, human diseases that originate in other animals, crop management and food production. These collections are also the repositories for the science of taxonomy: without them we wouldn’t be able to comprehend how many forms of life exist and have existed. In turn, without that knowledge, informed environmental conservation would be impossible. We could choose almost any specimen on our tour, but by way of example, let’s consider a collection of fishes we hold in the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, that Charles Darwin brought back from the Beagle expedition. Many of them had never before been seen by scientists. When they arrived in Cambridge, they became the basis of the original descriptions of new species – the so-called ‘type specimens’ that act as the physical definitions of their species. And because of the data Darwin recorded alongside the specimens, we know that in the 1830s each of them was alive in a specific location on Earth. Comparing those records with where the same species are found today enables us to track changes in population sizes, ranges and habitats through time. We could do that for each of the two million specimens in our museum. Looking at every specimen in every museum worldwide, that’s billions of specimens and billions of data points. And museums continue to collect vast numbers of specimens every year – adding not just extra examples, but also new kinds of information that scientists of the future can use, as we develop new ways of storing specimens and data that allow ever more kinds of questions to be answered. These stories do not feature in most visitors’ experiences of natural history museums – they are not typically what museum curators decide to communicate through their displays, which I think is a shame. When people learn that more than 99 per cent of a typical museum’s collection is held in storage, they tend to assume that museum storerooms are hiding the good stuff, which is oversupplied and jealously guarded. But this attitude stems from a misunderstanding about what such material is for. Yes, museums are by definition public spaces, but the public space in them is only one aspect of their

Some of the preserved fishes at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, which Charles Darwin collected on board HMS Beagle as he travelled around the world in the 1830s. These specimens helped shape his theory of evolution, and also serve as evidence today of the distributions of the species 200 years ago.

Introduction

purpose. As I mentioned, most of the material kept behind the scenes isn’t fit for display. Even that term – behind the scenes – suggests that the displays are ‘scenes’: dressed stages for looking at, not interacting with. Stored collections are the opposite of that, allowing hands-on research – by anyone, at least in theory. Museums hold material in public trust, so you should be able to make an appointment to see objects that aren’t on public display. The role of museums in sharing knowledge and inspiration is vital, but so is their role in taking care of the world’s best, most accessible record of life on Earth.

Those of us working in natural history museums have always had to care for, research and share their collections, but now we are also grappling with work on the climate crisis, biodiversity loss and colonial legacies. This brings with it a lot of responsibility, but from where I’m standing, I can see that the people working in these museums have begun to take every opportunity to learn more and share more, and to put the immeasurably important collections they look after to urgent use. It is an exciting time to work in museums, and to visit and support them as they tackle these essential challenges. We can genuinely improve the world using their collections, both in how we respond to environmental change, and how we ensure that our cultural institutions represent everybody, by telling the stories inherent in those collections honestly.

Today, while most people are less connected to nature than even a few decades ago, there is more information available about the natural world than ever before. Apart from being able to ask the internet to answer our questions, information about the natural world is everywhere, from advertisements to cartoons to documentaries – we learn it by absorption. Nonetheless, despite this abundance of information elsewhere, museums remain one of the key ways in which people can engage with the natural world. The roles that museums play in safeguarding the collections under their care, making the data they hold as accessible as possible, and sharing a passion for nature with the public, have never been more important. For all these reasons, our natural history museums are a vital part of society today, and that’s why we need to understand them better.

PART ONE

Are natural history museums unnatural?